Abstract

Purpose

Concordance between parents of children with advanced cancer and health care providers has not been described. We aimed to describe parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care, including differences by cancer type.

Patients and Methods

A total of 104 pediatric patients with recurrent or refractory cancer were enrolled at three large children's hospitals. On enrollment, their parents and providers were invited to complete a survey assessing perceived prognosis and goals of care. Patients' survival status was retrospectively abstracted from medical records. Concordance was assessed via discrepancies in perceived prognosis, κ statistics, and McNemar's test. Distribution of categorical variables and survival rates across cancer type were compared with Fisher's exact and log-rank tests, respectively.

Results

Data were available from 77 dyads (74% of enrolled). Parent-provider agreement regarding prognosis and goals of care was poor (κ, 0.12 to 0.30). Parents were more likely to report cure was likely (P < .001). The frequency of perceived likelihood of cure and the goal of cure varied by cancer type for both parents and providers (P < .001 to .004). Relatively optimistic responses were more common among parents and providers of patients with hematologic malignancies, although there were no differences in survival.

Conclusion

Parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals in advanced pediatric cancer is generally poor. Perceptions of prognosis and goals of care vary by cancer type. Understanding these differences may inform parent-provider communication and decision making.

INTRODUCTION

Few studies have described parent-provider concordance among children with serious illness. Parents of children with newly diagnosed cancer tend to be more optimistic than health care providers regarding prognosis1,2 and typically report the goal of cure.3,4 At end of life, parents often seek continued cancer-directed therapy,5 even when cure is unrealistic. Pediatric oncologists report that families' unrealistic expectations are the single greatest barrier to communication.6 When present, parent-provider prognostic concordance is associated with better patient quality of life and improved advanced-care planning.1,3,7,8 In addition, alignment of understanding of prognosis and goals of care has been associated with outcomes; when parents' goals of care are realistic and aligned with their perspectives of prognosis, they are less likely to be distressed.4 Understanding parent-provider concordance may therefore provide an opportunity to improve decision making,9 quality of care,10 and patient and family outcomes.4,11

To our knowledge, concordance between parents of children with advanced cancer and their providers has not been described. Neither are there descriptions of the relationships between concordance and cancer type, despite evidence that end-of-life experiences vary by diagnosis or services provided. For example, in one retrospective study, parents of children with leukemia were aware of their child's impending death for shorter periods of time compared with children with other cancer types.12 Likewise, when pediatric patients died while receiving standard hematology or oncology services, approximately 90% of parents and providers agreed that the child had no realistic chance of cure within the last week of life. In comparison, fewer than half of parent-provider dyads arrived at that understanding when children died undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) services.13 These shorter periods of awareness have been associated with greater parental psychological distress12 and poorer quality of life and physical health.14

The goal of this analysis was to describe parent-provider concordance and alignment in the setting of progressive, recurrent, or refractory pediatric cancer. We hypothesized that parents would be more optimistic than providers but that concordance would vary by cancer type. Exploratory aims were to identify additional factors of concordance. Such understanding could inform patient-provider communication, clinical care, and, in turn, long-term psychosocial outcomes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The PediQUEST (Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology) study was a pilot, randomized trial of a supportive care intervention in children with advanced cancer. The primary goal of the study was to assess the PediQUEST system, a software program that electronically collects patient-reported outcomes and generates feedback for providers.15 Secondary objectives included the evaluation of parent-provider concordance. Parents and providers were surveyed at the time of enrollment (before random assignment). Eligible patients were age ≥ 2 years with ≥ 2-week history of progressive, recurrent, or nonresponsive cancer and had received their cancer care at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, or Seattle Children's Hospital. All enrolled parents had written command of the English language. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each institution. Consecutive families were approached and 104 children enrolled between December 2004 and June 2009.

Study Instrument

The Survey About Caring for Children With Cancer (SCCC) is a comprehensive, self-administered survey that evaluates parents' and providers' perceptions of the child's illness. It was originally developed from a literature review and focus groups of parents and medical providers to identify key domains.1,16 Whenever possible, items were taken from previously validated surveys17,18; however, many were newly created to reflect evidence-based guidelines19 and underwent pretesting to assess content, wording, response burden, and cognitive validity. Similar pretesting of the adapted SCCC was performed for the PediQUEST study.4,15,20

Participating families were mailed or handed the survey, along with a self-addressed, stamped return envelope and a $5 coffee card incentive. One parent per family completed the survey. Primary health care providers received the SCCC by e-mail at the same time, along with a similar incentive. The provider survey included additional questions regarding years of experience and discipline (physician or nurse practitioner). Parents and providers who did not respond within 2 weeks received two additional reminders. Our analysis focused on the following survey items:

Prognosis.

A 4-point Likert scale assessed parent and provider views of the patient's likelihood of cure (very unlikely, unlikely, likely, or very likely, coded 0 to 3). Respondents were instructed to select only one response.

Goals of care.

A 5-point Likert scale queried respondents' primary goal of current medical treatment.1 Options included cure, keep hoping, make sure everything has been done, extend life without hope of cure, and lessen suffering. Respondents were instructed to select only one goal.

Alignment of prognosis and goals of care.

We previously defined alignment4 as either believing cure to be likely or very likely and having the goal of cure, or believing cure to be unlikely or very unlikely and having any goal other than cure. Respondents not falling into either category were defined as not aligned.

Concordance

We assessed concordance in three ways. First, we measured discrepancies between parent and provider perceptions of prognosis by subtracting provider from parent answers. This score ranged from −3 to 3; 0 indicated perfect agreement, and positive values corresponded to parents being more optimistic than providers. For example, when the parent stated that cure was very likely (3 points), and the provider stated that cure was very unlikely (0 points), the discrepancy score was 3 (ie, 3 − 0 = 3).

Second, we defined agreement as being present if both parents and providers selected the same Likert scale item response regarding cure likelihood or goal of care, or if both fell into the same category of alignment (aligned regarding goal of cure, aligned regarding goal other than cure, and not aligned). And third, parents and providers were defined as concordant based on dichotomized variables (ie, if they both reported cure as being likely or very likely or as being unlikely or very unlikely, or if they both reported goal of cure versus anything else).

Other Covariates

Patient characteristics were abstracted from medical records. Cancer types were categorized broadly as hematologic malignancies, CNS tumors, and non-CNS solid tumors. Patient survival status at 6 months and 3 years after enrollment was abstracted from the medical record after study completion. We explored known factors associated with parent-physician concordance (eg, provider age and parent education2) and additional factors that we hypothesized may be related to concordance, including child (eg, age, cancer type, time since diagnosis, and time since progressive disease), parent (sex, age, race or ethnicity, income, marital status, religion, and religiousness), and provider variables (sex, discipline, year of graduation, years of experience, and number of other patients enrolled onto study).

Statistical Methods

We restricted analyses to dyads who completed their surveys within 120 days of each other. Analyses were performed using STATA (version 12; STATA, College Station, TX) and SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize parent, provider, and child variables. The sign test for paired data was used to evaluate parent-provider discrepancy scores. Agreement of parent and provider responses, based on Likert scales, was measured with the κ coefficient. McNemar's test was used to assess concordance of parents and providers when responses were dichotomized. Fisher's exact test was used to compare distributions of parent or provider responses across cancer types. Logistic regression with robust SEs explored relationships between patient, parent, and provider characteristics and concordance. Survival by cancer type was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. The robustness of our findings was assessed in two ways. First, we restricted analyses to the 63 dyads whose surveys were completed within 30 days of each other. Conclusions remained the same. Second, when possible, analyses were repeated, adjusting for providers who cared for multiple enrolled patients. Findings were again similar to those of unadjusted analyses; unadjusted results are shown.

RESULTS

Seventy-nine parent-provider dyads completed the SCCC (74% of enrolled patients). Of these, 77 completed the survey within 120 days of each other, representing 77 families and 54 individual health care providers. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics of parents or providers who completed the SCCC compared with those who did not. Briefly, parents were predominantly mothers in their mid 40s with at least some college-level education (Table 1). The average age of their children was 12.6 years, and approximately half were girls. The most common cancer diagnosis was non-CNS solid tumor. On average, parent SCCCs were completed 26 months after initial diagnosis (standard deviation [SD], 20 months) and 10 months after first disease progression (SD, 12 months). Health care providers were predominantly female physicians in their late 30s. Most (n = 37; 69%) cared for a single patient in the study; however, several cared for two, three, or five separate patients (n = 11, 5, and one providers, respectively). In seven cases, the provider completed the survey first; in all others, the parent was first. Median time between parent and provider survey completion was 10 days (interquartile range, 4 to 23 days).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Time of Enrollment

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Parents (n = 77) | ||

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 43.7 | |

| SD | 7.8 | |

| Female sex | 66 | 86 |

| Education | ||

| At least some high school | 26 | 34 |

| At least some college | 41 | 53 |

| Graduate or professional school | 10 | 13 |

| Income* | ||

| < $24,999 | 10 | 14 |

| $25,000 to $74,999 | 25 | 36 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 15 | 21 |

| ≥ $100,000 | 20 | 29 |

| Children (n = 77) | ||

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 12.6 | |

| SD | 5.7 | |

| Female sex | 41 | 53 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Hematologic malignancy | 24 | 31 |

| CNS tumors | 7 | 9 |

| Non-CNS solid tumors | 46 | 60 |

| Months since diagnosis | ||

| Mean | 26.4 | |

| SD | 20.4 | |

| Months since most recent progression | ||

| Mean | 9.9 | |

| SD | 12.0 | |

| Days between parent and provider surveys | ||

| Median | 10 | |

| IQR | 4-23 | |

| Health care providers (n = 54) | ||

| Age, years† | ||

| Mean | 37.9 | |

| SD | 6.7 | |

| Years of experience† | ||

| Mean | 9.6 | |

| SD | 6.9 | |

| Female sex | 36 | 77 |

| Discipline | ||

| Physician | 47 | 87 |

| Nurse practitioner | 7 | 13 |

| No. of patients enrolled onto study | ||

| 1 | 37 | 69 |

| 2 | 11 | 20 |

| 3 to 5 | 6 | 11 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

n = 70.

n = 52.

Overall Parent-Provider Concordance

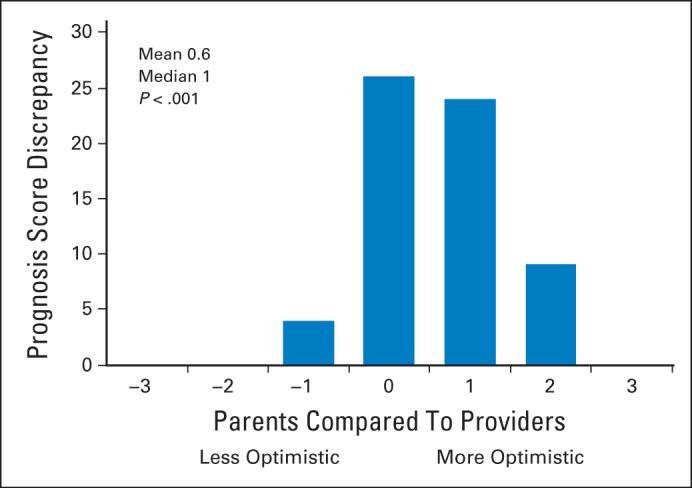

Complete data were available from 63 (82%) and 72 (94%) dyads with respect to current cure likelihood and goals of care, respectively. We have previously explored explanations for the degree of missing data, including the possibility that parents explicitly refrain from reporting poor prognoses.21 Discrepancies in cure likelihood scores were common; parents more commonly reported higher scores than providers (P < .001; Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Discrepancy in prognosis scores between parents and medical providers. Perception of cure likelihood at time of survey completion (n = 63; 11 parents and three providers missing). Any score > 0 indicates parent more optimistic; absolute number is indicative of degree of discrepancy. P value based on sign test.

Overall agreement between parents and providers was poor for cure likelihood (κ = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.11 to 0.35) and goals of care (κ = 0.12; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.44; Table 2). Forty-nine percent of responding parents compared with 22% of providers reported that cure was likely or very likely (McNemar's test P < .001). Similarly, a majority of parents (64%) endorsed a goal of cure, compared with 38% of providers (P < .001). The most commonly reported goal among providers was to extend life without hope of cure. Finally, although similar numbers of parents and providers reported goals aligned with their views of prognosis, parents were commonly aligned with a goal of cure (ie, they believed cure was likely, and they reported goal of cure), whereas providers more commonly reported that cure was unlikely and therefore had a goal other than cure (P = .031).

Table 2.

Agreement Between Parent and Health Care Providers

| Parent Response | Provider Response |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Unlikely | Unlikely | Likely | Very Likely | Total | |

| Likelihood of Cure (n = 63 dyads)* | |||||

| Very unlikely | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Unlikely | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Likely | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 19 |

| Very likely | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 12 |

| Total | 26 | 23 | 7 | 7 | 63 |

| κ coefficient | 0.22 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.11 to 0.35 | ||||

| P | < .001 | ||||

| Parent Response | Provider Response |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lessen Suffering | Extend Life Without Cure | Do Everything | Keep Hoping | Cure | Total | |

| Goals of Care (n = 72 dyads)* | ||||||

| Lessen suffering | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Extend life without cure | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Do everything | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Keep hoping | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Cure | 5 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 46 |

| Total | 9 | 33 | 0 | 3 | 27 | 72 |

| κ coefficient | 0.12 | |||||

| 95% CI | 0.05 to 0.21 | |||||

| P | .03 | |||||

| Parent | Provider |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses Not Aligned | Responses Aligned, Goal Not Cure | Responses Aligned, Goal Cure | Total | |

| Alignment Between Cure Likelihood and Goals of Care (n = 60)† | ||||

| Responses not aligned | 2 | 10 | 1 | 13 |

| Responses aligned, goal not cure | 3 | 18 | 0 | 21 |

| Responses aligned, goal cure | 8 | 6 | 12 | 26 |

| Total | 13 | 34 | 13 | 60 |

Each cell represents No. of parents or providers selecting given survey response.

Each cell represents No. of parents or providers in given category of alignment based on reported likelihood of cure and goals of care.

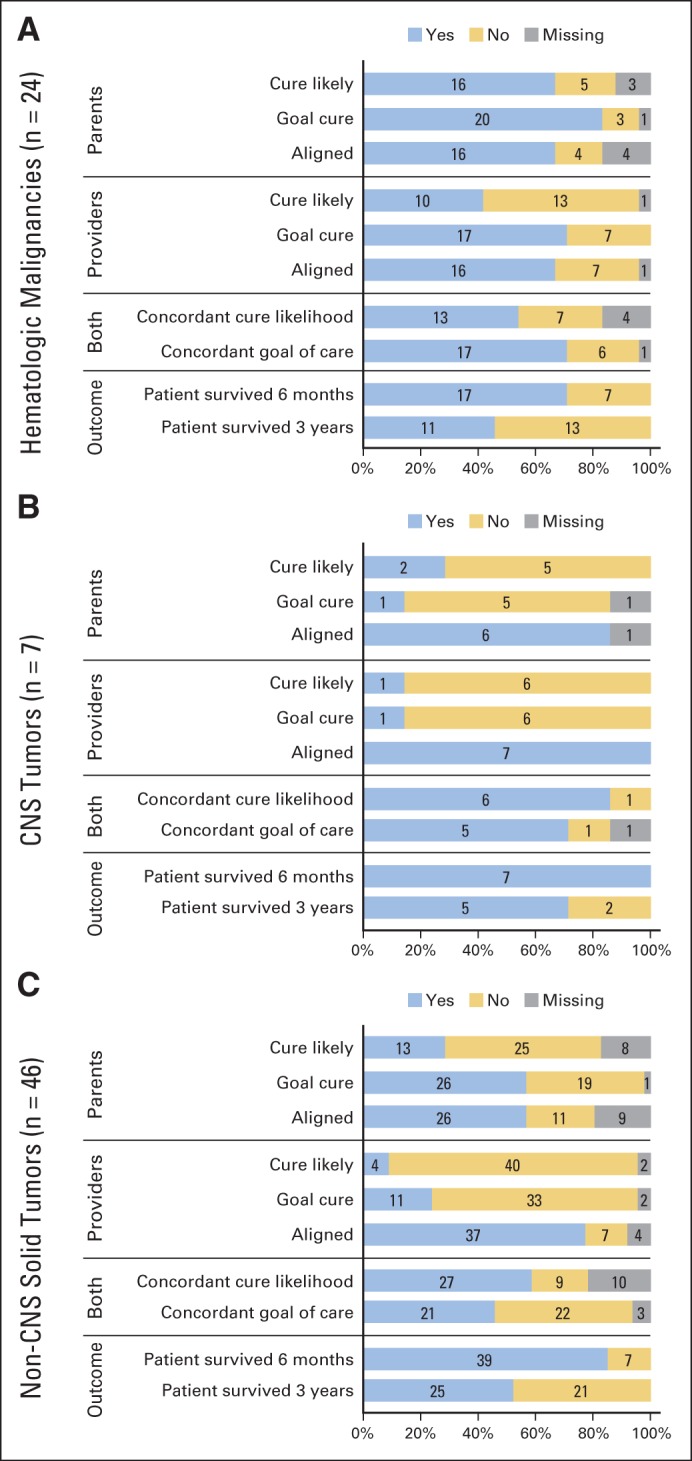

Analyses by Cancer Type

Parent and provider responses varied by cancer type (Figs 2A to 2C). In general, those caring for children with hematologic malignancies reported cure was likely and had a corresponding goal of cure (Fig 2A). Seventy-six percent of parents in this group reported cure was likely, compared with 29% and 34% of parents of children with CNS and non-CNS solid tumors, respectively (Fisher's exact test P = .004). Among providers, 43% reported cure was likely for patients with hematologic malignancies; however, even fewer (14% and 9%, respectively) of those caring for patients with the other cancer types reported the same (P = .004). Eighty-seven percent of parents endorsed a goal of cure compared with 17% and 58% of parents of children with CNS and non-CNS solid tumors, respectively (P = .002). Likewise, 71% of providers of patients with hematologic malignancies reported a goal of cure compared with 14% and 25% of other providers, respectively (P < .002).

Fig 2.

Parent and provider responses by cancer type. (A) Hematologic malignancies; (B) CNS tumors; (C) non-CNS solid tumors.

All of the providers for patients with CNS tumors reported goals that were aligned with prognosis (Fig 2B), compared with 70% to 84% in other groups (P = .16). For parents, alignment by cancer type ranged between 70% and 86% (P = .63). Parents and providers of patients with non-CNS solid tumors were less coincident; for example, only half of dyads agreed on goals (Fig 2C). There were no associations between cancer type and parent-provider concordance of cure likelihood (P = .65) or goals of care (P = .08; Figs 2A to 2C).

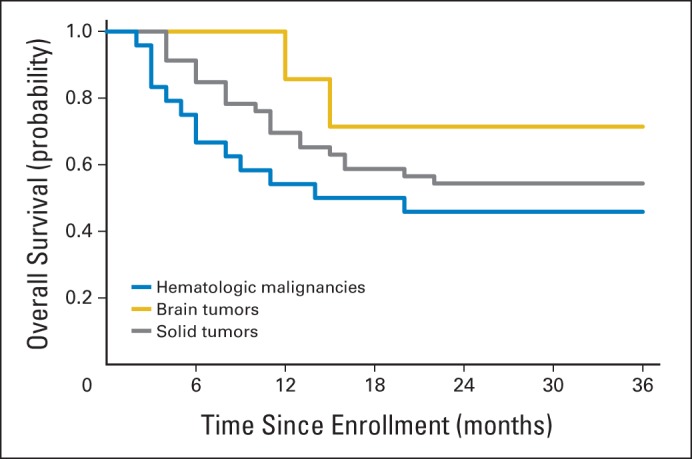

Seven children (29%) with hematologic malignancies died within 6 months of enrollment, and 13 (54%) died within 3 years. In comparison, no patients with CNS-tumors died within 6 months of enrollment, and only two (29%) died within 3 years. Seven (15%) and 21 (46%) of those with non-CNS solid tumors died in the same timeframes, respectively. There were no significant differences in survival outcomes among cancer types (6 months, P = .13; 3 years, P = .32; Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Survival outcomes by cancer type.

Exploratory Analyses of Concordance With Respect to Other Covariates

Parent-provider concordance regarding cure likelihood increased with age of providers (P = .020) and decreased if parents had received only high school–level education (P = .004). Trends suggested that prognostic concordance also increased with providers' years of experience (P = .063). No other parent, child, or provider characteristics were related to concordance.

DISCUSSION

In one of the first prospective studies to our knowledge among parents and providers of children with advanced cancer, we found that parent-provider agreement regarding prognosis and goals of therapy was generally poor. Overall, parents tended to be more optimistic than providers; they more commonly reported that cure was likely and that their goal was to cure their child's cancer. This was particularly true for parents and providers of children with hematologic malignancies. Those caring for children with CNS tumors tended to report that cure was unlikely and that their goal was no longer to cure. Parents and providers of children with advanced non-CNS solid tumors had less coincident responses and agreed on goals of care in only half of cases. Despite these differences, survival outcomes for the three groups of patients were the same.

Respondents completed the survey on enrollment, based on their knowledge at the time. Some of our results are therefore not surprising. For example, 5-year overall survival for pediatric patients with recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia ranges from 10% to 80%, depending on the timing and location of relapse.22 Intensive therapies like HSCT may improve survival to > 40% among patients with the poorest prognoses.23 Accordingly, both parents and providers may endeavor to cure the child's hematologic malignancy, regardless of the probability of cure. By comparison, pediatric patients with recurrent medulloblastoma have extremely low survival rates, and there are no proven regimens for salvage therapy.24 Their parents and providers may recognize this fact and endorse more palliative goals of care.

Whether it matters if we are ultimately right or wrong in our predictions is unclear; however, the relative optimism of parents and providers of patients with hematologic malignancies is worrisome. Patients who continue to receive cure-directed therapy at the end of life have greater suffering,16 and bereaved parents report wishing they had integrated palliative goals before they actually did.3 The lack of agreement among parents and providers of children with non-CNS solid tumors is also concerning. Providers understand the range of possible outcomes better than parents, and those in our sample commonly reported cure was unlikely, and the goal of care was not to cure. Parent responses, however, were variable. Although there are often no clear curative options akin to HSCT for patients with recurrent non-CNS solid tumors, several approaches may prolong survival in or cure select patients. These unpredictable outcomes may lead to greater provider uncertainty and inhibit explicit descriptions of prognosis and goals. Nevertheless, parents who know their child's anticipated trajectory are better able to cope,7 and most report wanting more concrete prognostic information than they typically receive, even when the prognosis is poor.8

At the time of diagnosis, prognostic concordance has been associated with provider confidence, parent decision making (ie, how well illness-related decision making aligns with preferred style), and parent education.2 We found associations between concordance and provider age and trends for providers' years of experience. Because most providers report learning to communicate with patients and families through trial and error,6 this finding may reflect skills and knowledge that developed over time.

Our findings affirmed that parent education is associated with concordance regarding prognosis2; however, others have shown that parents' demographic characteristics are unrelated to their understanding of prognosis.25 Indeed, although parents' report of prognosis may imply a true lack of insight, it may also reflect a preference not to endorse the possibility of their child's death.21

Alternatively, medical providers of all ages may be less likely to discuss poor prognoses for fear of taking away hope or contributing to distress.26 Honest discussion does neither.26 Rather, even one statement of poor prognosis may promote concordance.27 Hoping for the best but expecting the worst may allow for improved quality of life,28 and conversations about perceived problems, hopes, and expectations may support patient and family decision making.28,29

Our study has five principle limitations that warrant discussion. First, we created broad categories of cancer type (hematologic malignancies and CNS and non-CNS solid tumors), because the clinical experiences of patients within these categories tend to be similar. Our sample included only seven patients with CNS tumors, making it difficult to generalize our findings. The non-CNS solid tumor group included patients with various diagnoses; our categorization may have limited our ability to identify trends by specific diagnosis. Second, we did not evaluate the role of HSCT among families of children with hematologic malignancies, an experience that may explain some of our findings. Indeed, pediatric patients who die while undergoing HSCT services rarely have advanced-care plans, possibly because their parents and providers remain focused on cure.13 In addition, the poor survival of patients in this group may be partly explained by unanticipated transplantation-related mortality. Third, we conducted this study among parents at three large children's hospitals, where primary teams are often defined by diagnosis. The experiences of participants in our study may be different from those at smaller centers. Likewise, although we found no relationship between concordance and provider discipline (nurse practitioner v physician), the role different providers play at other institutions may vary. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of this analysis prevented us from determining where on the trajectory of experience parents and providers become more concordant. Finally, the population of parents and providers in our study had little sex, ethnic, or racial diversity, so we could not assess the probable cultural aspects of concordance.

These findings have implications for clinical practice. We recommend early, open, and honest conversations about prognosis, hopes, and expectations. These might explore concurrent goals of cure or life prolongation and quality of life, as well as “what-if” scenarios of cure likelihood or unlikelihood. Indeed, although most parents report receiving high-quality information regarding their child's diagnosis and treatment plan, fewer endorse the same regarding the efficacy of that treatment and its likelihood of cure.30 When held, however, these conversations allow parents and providers time to prepare for both positive and negative eventualities, in turn optimizing their emotional well-being and quality of life.3,9,10,12,31 This may be particularly important for parents of children undergoing HCST.13 Additional resources and communication tools may be warranted in certain families with limited education or health literacy. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that effective communication skills can be taught successfully; targeted training for staff may be warranted.32

In this prospective study of parents and providers of children with advanced cancer, we found that concordance of prognosis and goals of care is poor and that perceptions vary by cancer type. Additional prospective studies may provide better understanding of the factors and ramifications of concordance and parent and provider perspectives. For now, early and open communication may help.

Acknowledgment

We thank the families for their willingness to participate in the study and Sara H. Aldridge, Lindsay Teittinen, Janis Rice, Karen Carroll, and Karina Bloom for their work on enrollment and data collection.

Glossary Terms

- patient-reported outcomes:

questionnaires used in a clinical setting to systemically collect information directly from the patient.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant No. 1K07 CA096746-01 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; a Charles H. Hood Foundation Child Health Research Award; an American Cancer Society Pilot and Exploratory Project Award in palliative care of cancer patients and their families; and a St Baldrick's Foundation Fellow Award (A.R.R.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Abby R. Rosenberg, Liliana Orellana, Tammy I. Kang, Chris Feudtner, Veronica Dussel, Joanne Wolfe

Financial support: Joanne Wolfe

Administrative support: Joanne Wolfe

Collection and assembly of data: Tammy I. Kang, J. Russell Geyer, Chris Feudtner, Veronica Dussel, Joanne Wolfe

Data analysis and interpretation: Abby R. Rosenberg, Liliana Orellana, Veronica Dussel, Joanne Wolfe

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: Parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Joffe S, Hilden JM, et al. Parents' views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4759–4764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Kang T, et al. Psychological distress in parents of children with advanced cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:537–543. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluebond-Langner M, Belasco JB, Goldman A, et al. Understanding parents' approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2414–2419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.7759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilden JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, et al. Attitudes and practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: Results of the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:205–212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, et al. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5636–5642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, et al. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: Parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill DL, Miller VA, Hexem KR, et al. Problems and hopes perceived by mothers, fathers and physicians of children receiving palliative care. Health Expect. doi: 10.1111/hex.12078. [epub ahead of print on May 20, 2013] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala KL, et al. Promoting resilience among parents and caregivers of children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:645–652. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdimarsdóttir U, Kreicbergs U, Hauksdóttir A, et al. Parents' intellectual and emotional awareness of their child's impending death to cancer: A population-based long-term follow-up study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:706–714. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullrich CK, Dussel V, Hilden JM, et al. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: Parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood. 2010;115:3879–3885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalmsell L, Onelöv E, Steineck G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with cancer and the risk of long-term psychological morbidity in the bereaved parents. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: Results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1119–1126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough D, Clarridge BC, et al. Attitudes and practices of U.S. oncologists regarding euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:527–532. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-7-200010030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Daniels ER, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: Attitudes and experiences of oncology patients, oncologists, and the public. Lancet. 1996;347:1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streiner DL, Norman GR. New York, NY: Oxford Medical Publications; 1995. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use (ed 2) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. What's missing in missing data? Omissions in survey responses among parents of children with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0663. [epub ahead of print on May 27, 2014] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng SC, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Children's Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2008;22:2142–2150. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eapen M, Raetz E, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes after HLA-matched sibling transplantation or chemotherapy in children with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a second remission: A collaborative study of the Children's Oncology Group and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Blood. 2006;107:4961–4967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajjar A, Packer RJ, Foreman NK, et al. Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: Central nervous system tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1022–1026. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller KS, Vannatta K, Vasey M, et al. Health literacy variables related to parents' understanding of their child's cancer prognosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:914–918. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2715–2717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson TM, Alexander SC, Hays M, et al. Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: Predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldman E, Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: Ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 1):S24–S30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3608E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye E, Mack JW. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child's cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1896–1901. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, et al. Anxiety and depression in parents 4-9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: A population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1431–1441. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]