Abstract

Purpose

Acupuncture is a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modality that shows promise as a component of supportive breast cancer care. Lack of robust recruitment for clinical trial entry has limited the evidence-base for acupuncture as a treatment modality among breast cancer survivors. The objective of this study is to identify key decision making factors among breast cancer survivors considering entry into an acupuncture clinical trial for treatment of symptoms.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted among African-American (n=12) and Caucasian (n=13) breast cancer survivors. Verbatim transcripts were made and analyzed by two or more independent coders using NVivo software. Major recurring themes were identified and a theoretical framework developed.

Results

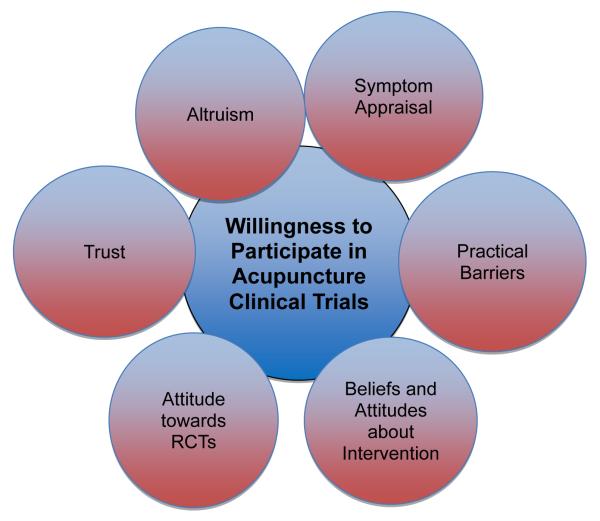

Six themes emerged reflecting key attributes of the decision to enter a clinical trial: 1) symptom appraisal, 2) practical barriers (e.g. distance, travel), 3) beliefs about the interventions (e.g. fear of needles, dislike of medications), 4) comfort with elements of clinical trial design (e.g., randomization, the nature of the control intervention, and blinding), 5) trust, and 6) altruism. African-American and Caucasian women weighed similar attributes but differed in the information sources sought regarding clinical trial entry and in concerns regarding the use of a placebo in a clinical trial.

Conclusions

We present of a theoretical framework of decision making for breast cancer survivors considering entry into a CAM clinical trial for symptom management. This framework can inform both research studies and programmatic initiatives to support a shared decision making process and robust recruitment to CAM trials among cancer survivors.

Keywords: Breast Cancer Survivors, Acupuncture, Clinical Trials, Decision Making

Introduction

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use among cancer patients is common (1-5). The 2007 National Health Interview Survey reports that 43.3% of U.S. cancer survivors used CAM in the last year, while 66.5% reported ever using CAM (1). Despite their popularity, few of the CAM modalities used in supportive cancer care have been systematically tested for clinical efficacy. Thus, there is an urgent need for rigorously designed and conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CAM interventions for cancer patients and survivors to establish the safety and efficacy of these interventions.

Acupuncture is a CAM modality that shows promise as a component of supportive cancer care (6). In a survey study, close to half of breast cancer survivors want acupuncture to be offered in a comprehensive cancer center (5). In a review of National Cancer Institute designated comprehensive cancer center websites, 60% of them mentioned acupuncture as a modality to be used for supportive cancer care (7). In order to guide evidence-based integration of acupuncture into cancer care, more rigorous RCTs for specific clinical indications (e.g. pain, hot flashes, fatigue) are needed. While effective recruitment is a critical step to the successful completion of these trials, evidence among cancer trials overall suggests that only a small percentage of cancer patients (3%) participate in clinical trials in any given year (8) and many clinical trials fail in patient accrual (9-12). Further, recruitment of minority patients in cancer clinical trials is lower than the general population (13-15), a factor that limits our knowledge base with regard to disparities in cancer outcomes (16).

It is not known what factors breast cancer survivors consider in choosing to participate in RCTs of acupuncture for symptom management among either the general population or cancer survivors. Incorporating the patients’ perspective into the design of RCTs for acupuncture could inform study designs and facilitate recruitment efforts, thus increasing the probability of completing successful and definitive trials that produce reliable data. We conducted a qualitative study to identify attributes that influenced African American and Caucasian breast cancer survivors’ willingness to participate in clinical trials of acupuncture for hot flashes, a very common symptom affecting this population (17).

Methods

We conducted 25 open-ended, semi-structured interviews with breast cancer survivors. Key inclusion criteria included women with stage I-III breast cancer who had finished primary cancer treatments and were experiencing daily hot flashes. Participants were recruited from an urban academic cancer center. Purposeful sampling was used to ensure that the sample reflected a diversity of age, race, and social economic status (SES). Regulatory approval was obtained through the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board as well as the Abramson Canter Center’s Clinical Trial Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee. Informed consent was performed and obtained from each participant

The interview questions were pilot tested and revised for clarity. Interviewers were all trained in semi-structured interviewing techniques by a medical anthropologist (FB). Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription company. Socio-demographic patient characteristics were collected at baseline. Interviewees were asked about their experience with hot flashes, attitudes about acupuncture use as a treatment modality, and their perspectives regarding participation in clinical trials of acupuncture that differ in design regarding the choice of the control intervention. The current report focuses on attitudes towards participating in a clinical trial. General information regarding the purpose and procedures of a randomized clinical trial were provided in the introduction to this aspect of the interview. Interviewees were asked to indicate which of the following hypothetical study designs they would be most likely (or not) to participate and why: 1) acupuncture versus placebo acupuncture; 2) acupuncture versus medication; or 3) acupuncture versus standard care. Placebo acupuncture was described as a procedure that used needles that did not penetrate the skin and that are on different points of the body compared to standard acupuncture.

De-identified transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 8.0 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster Victoria, Australia) to manage the data. Based on close reading of the transcripts, a coding scheme and coding dictionary were developed by the research team. Team members coded 5 transcripts together and the remaining transcripts were coded by two coders. Coding agreement was evaluated and discrepancies in codes discussed weekly in team meetings. We achieved saturation on all major themes after 25 interviews. A qualitative health research expert (EM) analyzed the data for recurring themes and significant thematic links. Statements and emerging themes were compared between transcripts of African American and Caucasian women in order to identify potential thematic differences between these populations.

Results

The study participants included 13 Caucasian (52%) and 12 African American (48%) women. The median age for participants was 57 years (with a range of 38-79 years). Fifteen (60%) of the study participants had a college degree or greater, while 10 (40%) did not complete college. Eleven (44%) women reported entering menopause naturally, while medically-induced menopause (defined as menopause brought on by surgical or medical processes) was identified in 13 (52%) of the women. Fifteen of the participants (60%) had used some form of CAM in the past 12 months. Four participants (16%) had used acupuncture in the past (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants (N=25)

| Characteristic | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 13 | 52.0 |

| Black | 12 | 48.0 |

| Age (Median 57, range 38-79) | ||

| <50 | 7 | 28.0 |

| 50-60 | 8 | 32.0 |

| >60 | 10 | 40.0 |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 10 | 40.0 |

| College or greater | 15 | 60.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Currently employed | 12 | 48.0 |

| Not Employed | 13 | 52.0 |

| Time since LMP (Median 8, range 0 to 39) | ||

| ≤1 year | 3 | 12.0 |

| 2-9 years | 12 | 48.0 |

| ≥10 years | 10 | 40.0 |

| Reason for menopause | ||

| Natural Menopause | 11 | 44.0 |

| Induced Menopause* | 13 | 52.0 |

| Currently menstruating | 1 | 4.0 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| I | 11 | 44.0 |

| II | 12 | 48.0 |

| III | 2 | 8.0 |

| Current General Health Status | ||

| Fair | 4 | 16.0 |

| Good | 10 | 40.0 |

| Very Good | 9 | 36.0 |

| Excellent | 2 | 8.0 |

| Current Number of Hot Flashes Daily | ||

| ≤4 | 15 | 60.0 |

| 5 or greater | 10 | 40.0 |

| Prior acupuncture use | ||

| Yes | 4 | 16.0 |

| No | 21 | 84.0 |

| Prior CAM use | ||

| Yes | 15 | 60.0 |

| No | 10 | 40.0 |

included chemotherapy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy

Six major themes emerged from analysis of the data, each found to influence decision-making and some are conceptually linked (Figure): 1) symptom appraisal; 2) practical barriers; 3) beliefs about interventions; 4) attitude towards and understanding of RCTs; 5) trust, and 6) altruism. Below we summarize these themes as they emerged in the data. Illustrative quotations are provided in the text and table (Table 2). Based upon the identified themes, attributes identified as key factors in decision making were identified (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Salient themes related to willingness to participate in an acupuncture trial

Table 2.

Sample of Illustrative Quotations

| Symptom Appraisal |

| If my hot flashes got worse, I would go for the acupuncture. [#010] [C] |

| Well, a chance to suppress some pain and hot flashes would make me wanna do it. [#025] [AA] |

| I’m not interested. That’s the only thing. [I: Because the hot flashes are not bad?] Right. [#024] [AA] |

| I am just anxious to find something to stop these hot flashes [on her willingness to participate] [#022] [AA] |

| Practical Barriers |

| The only issue I have is the convenience because I have a busy schedule. So I guess the only thing that would prevent me from participating is if there were, you know, scheduled times that I wouldn’t be able to make. [#010] [C] |

| Of course, convenience, scheduling and cost would be an issue. [#021] [AA] |

| Scheduling is a major issue in my life. [#009] [C] |

| The distance and the traffic and whatnot. It is hard. My schedule is very tight. It might be hard for me [to participate]. [#014] [C] |

| Well, like I said it all depend on where I would have to go and when and how frequently, you know, to participate. [#006] [C] |

| Location, location, location, and time. [#017] [AA] |

| Beliefs and Attitudes Toward Acupuncture-Positive |

| No…, no wouldn’t be anything against [acupuncture] because I’ve tried it and I think it works.[#015] [AA] |

| But I don’t know how it would work, but it’s been working for the Chinese, I guess it would work for me, I don’t know. [#019] [AA] |

| Because, I think for me, acupuncture is more of a natural homeopathic tired and true medication, or should I say it is a tired and true formula that obviously has been working as opposed to something synthetic that I would actually have to put in my body. [#021] [AA] |

| I am very open minded and curious about alternative therapies. [#013] [C] |

| I feel that, acupuncture,…you’re not putting yet another substance in your body. [#006] [C] |

| I’d rather be in the acupuncture group. Again, it’s less invasive. [#003] [C] |

| Beliefs and Attitudes Toward Acupuncture-Negative |

| [on preferring medication] I guess its fear. [I: Fear of acupuncture?] Right. [I: Okay, so is it fear of the actual like needles?] Needles, yes. [#012] [AA] |

| I’m not that hip on getting stuck with needles, you know. [#011] [AA] |

| The lack of evidence, that’s what’s making me say “no.” There’s no evidence that it’s going to do anything for me.… Why do I wanna feel, being totally honest, that it’s more of a charlatan type of treatment? You don’t hear doctors talking about it.… I mean, why aren’t the doctors recommending it? [#005] [C] |

| Beliefs and Attitudes Toward Medications |

| I don’t want anymore more pills.… Because I’m taking enough medicine now…I take six pills…seven, eight, nine, ten pills a day…you know, that’s just too many pills. [#015] [AA] |

| And everything they give you to take is pills nowadays, honey, it helps one thing and messes up something else. [#008] [AA] |

| ‘Cause I hate taking pills, I really do; I’m sick of pills. [#011] [AA] |

| I try to stay away from medicine. I take enough on a daily basis.… One thing that puts the caution to me about participating would be the side effects of any kind of medication; that is it. [#018] [AA] |

| So, I would definitely use acupuncture over any kind of medication which would reduce my side effects, okay? I don’t like too many pills, okay? If this is something that can treat the symptoms, I would go with this. [#001] [C] |

| I’m concerned about side effects, about interaction with other medications, and… I prefer to not use drugs, if possible. [#010] [C] |

| I don’t want to medicate any more than I have to. [#014] [C] |

| Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials |

| I would rather have the real stuff. I wouldn’t want to take the fake stuff, so no. [on placebo] [#019] [AA] |

| [I: You are just not comfortable with the chance of placebo?] Yeah, with that. I would just want the real [acupuncture] for my own personal benefit. [#025] [AA] |

| I believe very strongly in experimental design. Yeah. [on being willing to participate] [#020] [C] |

| I don’t want to be the one that doesn’t get anything… I that would worry me, if I wasn’t feeling better and it was because I wasn’t really receiving any treatment. [#014] [C] |

| Trust |

| I would have to have a connection with the person who was doing it [acupuncture]. I am a touchy, feely, type person. If I felt they were just going through the motions and they really didn’t care to connect with me as a person, I would not want to come back. [#017] [AA] |

| Probably because you are affiliated with [institution] I figure, you know, it is legitimate. [#013] [C] |

| Altruism |

| I think that anything that will help the next group of women is encouraging, so I would participate as long as it was going to help somebody down the road. [#018] [AA] |

| But I say “yes” if it helps people. [#008] [AA] |

| I think the opportunity to see if it works and certainly to help other breast cancer patients. [#013] [ C] |

| I pretty much will participate in any study they ask me to participate in to help somebody else or even myself. So that’s pretty much been my goal since I was diagnosed with cancer. [#004] [C] |

These quotations are in addition to those presented within the text of the manuscript. Abbreviations: AA, African American; C, Caucasian

Table 3.

Attributes Salient to the Willingness to Participate Decision

| ATTRIBUTES OF RCT |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Challenges (Travel and Time) |

Travel and time constraints |

|

Time and financial resources |

| Severity of Symptoms | Symptoms not severe |

|

Symptoms severe |

| Knowledge/Attitudes towards acupuncture |

Unfamiliar and/or fearful of needles |

|

Aware of acupuncture as a positive experience |

| Attitudes towards Pharmacy/Polypharmacy |

Not averse to additional medication |

|

Strong desire to avoid medications/polypharmacy |

| Knowledge/Attitudes towards RCT’s |

Poor understanding clinical trial design |

|

Understands concepts of randomization/blinding |

| Trust in Research Team/Provider |

Distrust of scientific research |

|

Trust in research team and scientific process |

| Altruism/Altruistic motivation |

Wants to help others but not through participation in clinical trials |

|

Motivated to help others through participation in clinical research |

Each attribute can be weighed on a spectrum that reflects the degree to which personal preferences make that attribute a factor that weighs the decision either against or towards willingness to participate in a clinical trial. The data from this study suggests that the first two attributes are especially salient in this decision making process.

Symptom Appraisal

Most of the women in this study expressed a willingness to participate in a trial if they were experiencing symptoms that significantly diminished their quality of life. The mere presence of symptoms (in this case, hot flashes) was not sufficient motivation for participation, given the time and effort required. Women weighed the pros and cons of participation, with the severity of symptoms balanced against the time and effort of participating in a study. When the anticipated decrease in symptom severity was great perceived to outweigh the perceived costs, women would express a willingness to participate as suggested in the quotation below.

I feel that if the hot flashes did get unbearable that I would automatically want to try the acupuncture and the medication. [#012] [AA]

Practical barriers

Perceived time, scheduling, travel, parking, and other logistical challenges were major barriers to willingness to participate in clinical trials; the women in this study were cautious about over-committing and introducing additional stress into their lives. The active stage of life of many breast cancer survivors is illustrated in the following statement.

I have three small children. My oldest is five. … Three and 18 months. So anytime that I need to leave the house … I need to rely on grandparents. [#007] [C]

Women who have demanding work schedules, are caring for young children or other family members, or who live a considerable distance from the treatment site often expressed that they would not be willing to participate in any kind of clinical trial if these barriers were not addressed in some way.

Beliefs and Attitudes about Interventions

Attitudes of and awareness about the type of intervention being tested played a large role willingness to participate in a clinical trial. Women with some knowledge of acupuncture were generally more open to participating in a clinical trial. Awareness and familiarity with acupuncture was associated with a positive attitude toward this intervention and a greater degree of openness towards enrollment in a clinical trial as illustrated by the statement below.

I believe in it [acupuncture]. I mean, I think that things like this work. I mean, look at hot yoga. It’s a perfect example, and I think if I could couple that hot yoga with acupuncture I might really be able to glide though the menopausal part of my life. [#002] [C]

Several women reported having heard positive stories about acupuncture from friends and family, particularly with regard to the use of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic pain. Conversely women who were acupuncture naïve and/or expressed a fear of needles generally conveyed reluctance to participate in a clinical trial of acupuncture. Women’s cancer treatment experience was found to influence their willingness to participate in several ways. Some women expressed a pronounced aversion to needles having endured many hypodermic needle sticks during the course of their cancer treatment.

Yeah, I’m done. I’m done. No more needles. … I just don’t wanna get poked. [#007] [C]

Women with polypharmacy concerns or negative attitudes toward pharmacological interventions conveyed a general willingness to participate in an acupuncture trial, but reluctant to participate in a trial with a medication arm. Some were eager to avoid medications on the grounds that they were already taking too many pharmaceuticals.

I am on so much medication now that if I had a way of doing something that wouldn’t be an additional pill bottle that I would have to worry about, contraindications … I would probably do acupuncture if it was available. [#017] [AA]

These women were very open to the concept of exploring acupuncture as a non-pharmacological intervention for their symptoms.

Because I think as a cancer person, who has had cancer and has been treated with very invasive means, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, you don’t want another foreign object in your body. [#020] [C]

Attitude toward Randomized Clinical Trials

A desire to retain control of treatment decisions was stated as a reason for not participated in a randomized clinical trial (RCT). Women were asked to respond to three possible study designs: acupuncture versus placebo acupuncture, acupuncture versus medication, and acupuncture versus standard care. Although the value of a comparison group in a study design was generally acknowledged, statements indicated a lack of understanding regarding the importance and process of random assignment to treatment groups. In some cases, respondents believed that they could choose between treatment arms with this belief persisting after explanation of the randomization process. Some respondents perceived randomizing to real versus placebo acupuncture as a “trick” and were concerned that women blinded to the treatment assignment would not know whether to expect a benefit from the intervention.

That’s tricking. [I: You think it is tricking the patient?] Yeah, because if you give me acupuncture, you should give me acupuncture, if you are not you are not. That is kind of tricky, a little bit. … That would be kind of deceiving a little bit. [#018] [AA]

Some conveyed a preference for two active treatment groups (rather than a placebo acupuncture group as a control) because all participants could then expect relief of symptoms. In general, women that did not understand the purpose or procedure of randomization were less willing to participate.

Trust

The presence of trust mitigated reservations about the nature of RCTs. Trust in the provider and/or research team facilitated willingness to participate in any clinical trial, regardless of the study design. In some cases, women expressed a profound and comprehensive trust in the provider and research team.

If it was recommended by [name of institution] or in a trial or something, I would be more likely to trust that and then it would be okay. [#017] [AA]

These women were willing to participate in any clinical trial the provider recommended with few questions and expressed trust that the provider would ensure their safety regardless of the study design.

Altruism

The presence of altruism was associated with openness to randomization as a participant in a RCT (to receiving placebo, medication, or acupuncture as necessitated by the study design without a choice regarding to which group they would be assigned). Expressions of altruism were closely associated with attitudes toward RCTs.

I would definitely want to participate [in a trial] because I think I would want to give back to all the women who have gone through trials before and have helped me to be able to have a doctor who can make decisions now based on findings. [#017] [AA]

An understanding of the importance of blinding and randomization coupled with the belief that the scientific study of clinical care makes a significant contribution to society were meaningful motivators for participating in a clinical trial.

Attributes of Decision Making for Participation in Acupuncture RCT’s

Informed by the emergent themes discussed above, 6 attributes of RCT’s were identified as salient to decisions regarding willingness to participate (Table 3). The importance of each attribute and the degree to which it weighs for or against participation is anticipated to vary across decision makers. For example, logistic challenges such as travel and time might weigh against participation for women with resource constraints but towards participation for a woman who lives close to the treatment facility and/or has adequate financial resources. Consideration of these attributes can support the decision making process for women considering entry into an acupuncture clinical trial.

Comparison between African American and Caucasian Participants

While the six major themes applied to both African American and Caucasian participants, the two groups differed in how they weighed some of these factors. Compared to Caucasian participants, African American participants heavily weighed the opinions of family members and friends when considering entry in an RCT. Caucasian participants were more likely to cite key information sources as the physician, other health professionals, the Internet, or past research participants. While some Caucasians did consult with family members, they stressed the importance of consulting health professionals because of clinicians’ expertise in clinical trials. African American participants consulted their physicians as well, but did not emphasize trust in physicians over family members solely due to the physicians’ additional medical expertise.

African American and Caucasian groups also differed in their perception of the placebo effect. While both groups expressed altruism as a motivating reason to participate in clinical trials, several African American participants mentioned their dislike for placebos. The primary concern was regarding effectiveness. Some African American participants were wary that their condition might worsen after they finished the study if they were a part of the placebo group. To these participants, it was acknowledged that the placebo may work during the study, but concern remained that the placebo arm would leave them without lasting benefits when the study ended. This barrier towards participation was not mentioned by the Caucasian participants.

Discussion

Acupuncture holds promise as a component of integrative oncology, but rigorous RCTs for specific clinical outcomes (e.g. pain, hot flashes) need to be tested in cancer populations to establish both safety and efficacy, and ultimately guide clinical care. In this study, we identified 6 patient level factors that are weighed by breast cancer survivors when considering participation in an acupuncture RCT. The insights and framework generated by this study can support shared decision making and inform interventions to increase robust recruitment to CAM clinical trials among breast cancer survivors.

A key attribute of decisions regarding clinical trial entry for these participants was the severity of symptoms experienced. In previous work we have reported that the severity of hot flashes among breast cancer survivors is a key factor when considering acupuncture as a treatment modality (18). We now report that symptom severity is also an important factor in willingness to participate in a clinical trial. Only if hot flashes were severe enough to have an impact on daily lives did women consider entry into a clinical trial. Self-interest has been previously identified as an important factor motivating cancer patients in participating in clinical trials (19). Women weighed the severity of hot flashes against concerns about logistical considerations of participation. Practical issues such as time and transportation carried considerable weight in the decision making process. Women who felt that their schedules were already too full or who had significant concerns about commuting to and from a treatment site expressed unwillingness to participate in a trial. Other studies have found that female cancer survivors cite being “too busy” as a major reason for declining to participate in trials (20). Addressing the practical barriers to participation (e.g., offering free parking, setting up satellite sites to reduce the commute, and minimizing scheduling requirements) is important as part of a strategy to encourage participation in clinical trials.

Attitudes toward and knowledge about treatment modalities were significant factors influencing willingness to participate in specific trial designs. Women who wanted to avoid additional medications due to concerns about polypharmacy and medication side-effects expressed an openness to acupuncture. Those who had heard positive stories about acupuncture, or who had experienced it themselves, were more willing to participate in a study of acupuncture to treat hot flashes. Similarly, Schneider et al (21) found that those with prior experiences with CAM modalities were more likely to express willingness to participate in CAM trials. We report that women who were acupuncture naïve and/or had a fear of needles displayed an unwillingness to consider participating in an acupuncture trial. Some respondents expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of acupuncture. Several participants believed that skin puncture was contraindicated after their cancer treatment. These negative attitudes and beliefs towards acupuncture diminished the likelihood of these women’s desire to participate. Our findings suggest that efforts to recruit women to acupuncture clinical trials should include an intervention to increase participants’ familiarity with the procedure. For example, audio-visual materials and patient testimonials that describe the experience of undergoing acupuncture treatments may increase familiarity with acupuncture and openness to trial entry.

Scientific literacy with respect to understanding components of study design was associated with greater expressed willingness to participate in a clinical trial. For some women, a negative attitude toward randomization and/or blinding was significant barriers to entry in a clinical trial. Several women discussed their aversion to receiving placebo because they would be “getting nothing” in return for their time and effort. Similarly, Ellis (19), Madsen et al (22) report that uneasiness with randomization along with the possibility of receiving placebo is significant barriers to participation in RCTs. Concerns about recurrence of symptoms following the end of the intervention (especially among placebo arms) and lack of consideration of patient preference in treatment assignment, are factors to consider in future designs of acupuncture RCT’s. Poor understanding of principles of equipoise and the reasons for random assignment of treatment in clinical trials has also been reported in the lay public (23). Interventions to increase scientific literacy with regarding to clinical study design may decrease barriers to robust recruitment for RCT’s.

Our findings suggest that altruism facilitates willingness to participate in RCT’s. Trust in the provider and research team also influenced willingness to participate; when present trust was found to mitigate concerns about randomization, blinding, the use of a placebo, and the nature of the intervention. These findings are consistent with previous work regarding conventional medical therapy where a lack of trust and/or confidence in physicians and the medical community is found to be a barrier to study recruitment (19, 22).

The factors we found to influence decision making among African Americans regarding clinical trial entry were generally consistent with previous studies. In particular, the importance of consulting with close family members was consistent with the recognized role of familial support during cancer treatment (24, 25). Among African American patients who declined participation in one study, 83% of their family and friends had expressed similar reservations towards clinical trials (26). We are the first to report reluctance towards taking placebos because of a temporary effect. While past studies have examined African American’s mistrust and misunderstandings towards the clinical trial process particularly in the context of the Tuskegee case (27-29), they have not reported a negative attitude toward placebo due to its potential temporary effectiveness.

Our study has several limitations. The sample was drawn from an urban tertiary medical center limiting the demographic characteristics of the study participants. We asked questions regarding hypothetical participation in acupuncture trials rather than actual participation so the decision making attributes identified may not fully capture the complexity of a clinical decision related to trial participation. Finally, we explored the decision to enter an acupuncture clinical trial for the treatment of hot flashes among breast cancer survivors. Our findings may differ from other important CAM modalities such as yoga or the use of herbs as the nature of the interventions differ. However, these modalities share some attributes as well such as providing an alternative approach to traditional medicine.

In conclusion, we report the development of a theoretical framework of decision making for breast cancer survivors considering entry into a CAM clinical trial. The framework identifies key attributes that women consider and balance in this decision making process. Cancer survivors are a unique population. Theoretically based, tailored efforts to support informed decision making and robust clinical trial recruitment are needed in order to build the evidence base for CAM as a symptom treatment modality option for cancer survivors.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded in part from American Cancer Society CCCDA-08-107 award. Mao is a recipient of the National Institute of Health / National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grants R21 AT004695 and K23004112. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no financial relationship with the organization that sponsored this research. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

References

- 1.Mao JJ, Palmer C, Healy K, Desair K, Amsterdam J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0153-7. DOI 10.1007/s11764-010-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris KT, Johnson N, Homer L, Walts D. A comparison of complementary therapy use between breast cancer patients and patients with other primary tumor sites. Am J Surg. 2000 May;179(5):407–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: Comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7(4) doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt G, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use, spending, and quality of life in early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2010;59(1):58–66. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews AK, Sellerggren SA, Huo D, List M, Fleming G. Complementary and alternative medicine use among breast cancer survivors. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(5):555–62. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.03-9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capodice JL. Acupuncture in the oncology setting: clinical trial update. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2010 Dec;11(3-4):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brauer JA, Sehamy A, Metz JM, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative medicine and supportive care at leading cancer centers: A systematic analysis of website. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(2):183–186. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lara PN, Jr., Paterniti DA, Chiechi C, et al. Evaluation of factors affecting awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9282–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hondras MA, Long CR, Haan AG, Spencer LB, Meeker WC. Recruitment and enrollment for the simultaneous conduct of 2 randomized controlled trials for patients with subacute and chronic low back pain at a CAM research center. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Oct;14(8):983–92. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastore LM, Dalal P. Recruitment strategies for an acupuncture randomized clinical trial of reproductive age women. Complement Ther Med. 2009 Aug;17(4):229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins V, Farewell D, Batt L, Maughan T, Branston L, Langridge C, Parlour L, Farewell V, Fallowfield L. The attitudes of 1066 patients with cancer towards participation in randomized clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2010 Dec 7;103(12):1801–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson JM, Torgerson DJ. Increasing recruitment to randomized trials: a review randomized controlled trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting under representative populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmotzer GL. Barriers and facilitators to participation of minorities in clinical trials. Ethnicity & Disease. 2012;22(2):226–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paskett ED, Katz ML, DeGraffinereid CR, Tatum CM. Participation in cancer trials: recruitment of underserved populations. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2003;1(10):607–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruner DW, Jones M, Buchanan D, Russo J. Reducing cancer disparities for minorities: a multidisciplinary research agenda to improve patient access to health systems, clinical trials, and effective cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2209–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su HI, Sammel MD, Springer E, Freeman EW, Demichele A, Mao JJ. Weight gain is associated with increased risk of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0802-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao JJ, Leed R, Bowman MA, et al. Acupuncture for hot flashes: Decision making by breast cancer survivors. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:323–332. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis PM. Attitudes towards and participation in randomized clinical trials in oncology: A review of the literature. Annals of Oncology. 2000;11:939–945. doi: 10.1023/a:1008342222205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osann K, Wenzel L, Dogan A, Hsieh S, Chase DM, Sappington S, Monk BJ, Nelson E. Recruitment and retention results for a population-based cervical cancer biobehavioral clinical trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):558–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider J, Vuckovic N, DeBar L. Willingness to participate in complementary and alternative medicine clinical trials among patients with craniofacial disorders. J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Jun;9(3):389–401. doi: 10.1089/107555303765551615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madsen SM, Holm S, Riis P. Attitudes toward clinical research among cancer trial participants and non-participants: an interview study using a Grounded Theory approach. J Med Ethics. 2007 Apr;33(4):234–40. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson EJ, Kerr CE, Stevens AJ, Lilford RJ, Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Beck SR, Rowley MG. Lay public’s understanding of equipoise and randomisation in randomized controlled trials. Health Technol Assess. 2005 Mar;9(8):1–192. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta9080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotay CC, Wilson ME. Social support and cancer screening in African American, Hispanic, and Native American Women. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(1):31–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.1998006031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson PD, Gord SV, Davis L, Condon EH. African American women coping with breast cancer: a qualitative analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(4):641–7. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.641-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorelick PB, Harris Y, Burnett B, Bonecutter FJ. The recruitment triangle: Reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998;90:141–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African American towards participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]