Abstract

Introduction

Research suggests cumulative measurement of HIV exposure is associated with mortality, AIDS, and AIDS-defining malignancies. However, the relationship between cumulative HIV and non-AIDS-defining malignancies (NADMs) remains unclear. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of different HIV measures on NADM hazard among HIV-infected male veterans.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study utilizing Veterans Affairs HIV Clinical Case Registry data from 1985-2010. We analyzed the relationship between HIV exposure (recent HIV RNA, % undetectable HIV RNA, and HIV copy-years viremia) and NADM. To evaluate the effect of HIV, we calculated hazard ratios for three common virally-associated NADM (i.e., hepatocarcinoma (HCC), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA)) in multivariable Cox regression models.

Results

Among 31,576 HIV-infected male veterans, 383 HCC, 211 HL, and 373 SCCA cases were identified. In multivariable regression models, cross-sectional HIV measurement was not associated with NADM. However, compared to <20% undetectable HIV, individuals with ≥80% had decreased HL (aHR=0.62; 95%CI=0.37-1.02) and SCCA (aHR=0.64; 95%CI=0.44-0.93). Conversely, each log-10 increase in HIV copy-years was associated with elevated HL (aHR=1.22; 95%CI=1.06-1.40) and SCCA (aHR=1.36; 95%CI=1.21-1.52). Model fit was best with HIV copy-years. Cumulative HIV was not associated with HCC.

Conclusion

Cumulative HIV was associated with certain virally-associated NADM (i.e., HL, SCCA), independent of measured covariates. Findings underline the importance of early treatment initiation and durable medication adherence to reduce cumulative HIV burden. Future research should prioritize how to best apply cumulative HIV measures in screening for these cancers.

Keywords: HIV, viral load measurement, non-AIDS defining cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus

Introduction

Combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART) dynamically transformed the epidemiology of HIV in the United States. Since cART, the incidences of opportunistic infections and AIDS-defining malignancies (ADM) have declined.1 However, over the same interval, non-AIDS-defining malignancies (NADM) have increased, and now NADM collectively represent over one-half of cancers diagnosed in HIV-infected individuals. 2-5

Several NADM (e.g., hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA)) are mediated by oncogenic viruses.6-8 In vitro data suggests HIV interacts with other oncogenic viruses and may facilitate viral activity and proliferation.9,10 Thus, in the current HIV era defined by increased life expectancy and longer duration of cancer susceptibility, cumulative HIV may be a valuable measure to classify future cancer risk.

While serial collection of HIV RNA is available, cross-sectional values have been more commonly utilized.11 Recently, research has shown a stronger association between cumulative HIV and increased risk of AIDS and mortality, compared to cross-sectional HIV measurements.12 Furthermore, Zoufaly et al 13 examined 6,022 HIV-infected patients receiving cART and observed an association between cumulative HIV and ADM (i.e., non-Hodgkin lymphoma). However, while HIV-infected individuals have been shown to have an excess of ADM and NADM, the effect of cumulative HIV on NADM risk has not been adequately evaluated.14 If associated with NADM risk, cumulative HIV may be a functional instrument to identify high-risk individuals for cancer screening. The aim of our study was to evaluate the association between three different cross-sectional and cumulative HIV measures and virally-associated NADM hazard (i.e., HCC, HL, SCCA; representing the three most prevalent virally-associated NADM15) among US male veterans diagnosed with HIV infection between 1985 and 2010.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas).

Study Population

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) HIV Clinical Case Registry (CCR) is a nationwide registry containing health-related information on all known HIV-infected VA users16,17. The registry draws upon the electronic medical records of over 65,000 HIV-infected patients cared for by the VA since the registry's inception. Following the identification and registration of HIV-infected veterans, all past clinical data are electronically retrieved. The database is automatically updated electronically. On-site HIV coordinators provide maintenance and verification. The registry includes demographic, laboratory, pharmacy, outpatient and hospitalization data, and vital status.

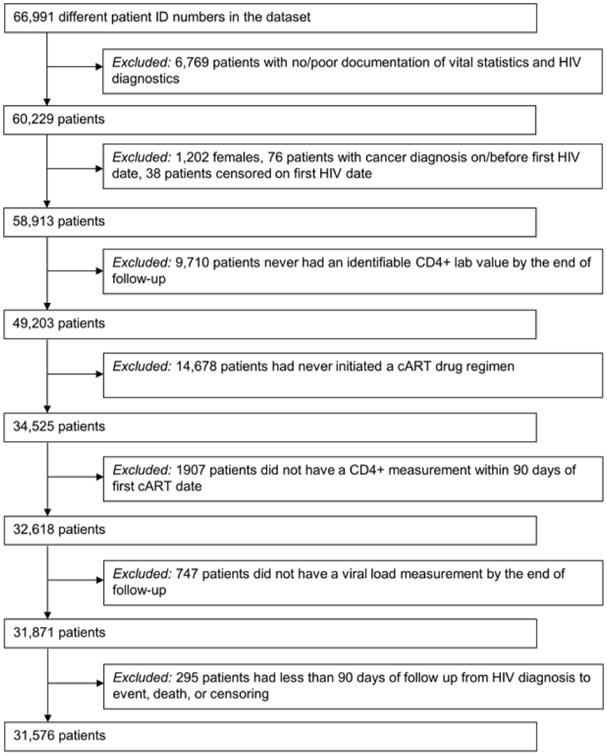

66,991 HIV-infected adult veterans were enrolled in the VA HIV CCR between 1985 and 2010. Figure 1 describes criteria used to define the final sample. The study population was restricted to HIV-infected veterans over age 18 with documented CD4 and HIV measurement. Inclusion required a confirmed HIV diagnosis date, based on 1) the presence of multiple International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code for HIV (042 or V08), or 2) a combination of ICD-9 code for HIV, positive HIV-related test (e.g., ELISA, Western Blot, quantifiable HIV RNA measurement), or prescription delivery of cART. To avoid inclusion of individuals erroneously added to the registry, individuals without adequate HIV diagnostics (i.e., only a single ICD code for HIV and no lab or pharmacy records) or vital statistics were removed (n=6,769). HIV index date was defined as the earliest ICD-9 code, positive test, or prescription delivery. Due to limited number of females in the population (<2%), only male veterans were included in our analyses. Additionally, we removed individuals whose death or censor date was the same as their HIV index. To analyze the effect of cumulative HIV on individuals treated in the modern treatment era, we conducted our analyses using only individuals ever receiving cART, defined as any combination of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors classes and 1 of either NNRTI or PI classes, integrase inhibitors, or CCR5 inhibitors and any combination of two classes. 31,576 HIV-infected veterans were included in the final sample.

Figure 1. Flow chart of selection criteria generating final cohort of HIV-infected veterans.

Virally-associated NADM

The primary outcome was diagnosis of incident virally-associated NADM (i.e., HCC, HL, SCCA), identified from inpatient and outpatient ICD-9 codes (HCC=155.0, HL=201.4-9, SCCA=154.2-3). The follow-up interval for longitudinal analyses spanned from the index visit to NADM diagnosis, death or December 31, 2010 (the final date of the current CCR iteration), whichever occurred first. To minimize inclusion of patients with prevalent NADM, individuals diagnosed with NADM prior to or within 6 months after the initial HIV diagnosis date were excluded.

Data management and calculating HIV RNA load

To account for potential differences follow-up visit frequency, each individual's follow-up duration was divided into 7-day intervals. Each interval had a unique beginning and end date. Laboratory values were updated at the beginning of each interval, with the last observation carried forward when no new measurement was available.

HIV RNA load was modeled using three different strategies. Recent viral load was captured as a time-updated (7-day intervals), noncumulative HIV measurement. Recent viral load was modeled as the log copies/mL.

Two different cumulative HIV measurements were also generated. The first was a time-updated measurement of the cumulative percentage of follow-up HIV RNA was in the undetectable range, as shown in the equation below (Eq. 1). For continuity across study years and standardization of operational procedures at different contributing VA facilities, the threshold for undetectable HIV RNA was established as <500 copies/mL.

| (Eq. 1) |

Where ti(j-1) and ti(j) represent the beginning and end date, respectively, of each follow-up interval and Uj represents whether or not HIV RNA was in the undetectable range over the referred interval.

Based upon evidence from research in cART medication adherence and the association between adherence and virologic failure, the % time undetectable HIV RNA was modeled as a categorical variable <20%, 20-39%, 40-59%, 60-79%, and ≥80%.18,19

The final method of measurement, HIV copy-years viremia, has been previously developed and utilized to predict all-cause mortality among HIV-infected individuals.11 The measurement represents an area-under-the-curve estimate, analogous to pack-years smoking. A complete description can be found elsewhere.12

Briefly, each HIV RNA measurement was attributed to its respective 7-day interval. Subsequently, using the equation (Eq. 2) shown below, we calculated cumulative HIV exposure, where ti(j-1) and ti(j) represent the beginning and end date, respectively, of each follow-up interval and VLj represents the HIV RNA load over the referred interval. HIV copy-years is expressed in number of HIV copies multiplied by years (per mL of plasma). For example, 100,000 copy-years can represent having 10,000 HIV copies every day for 10 years or 100,000 HIV copies every day for 1 year.

| (Eq. 2) |

Similar to previous studies, HIV copy-years was modeled as log copy-years/mL.11,12

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to determine the distributions of sociodemographic and clinical variables in the study population. Characteristics were described in the overall cohort and separately in individuals diagnosed with HL, SCCA, and HCC. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were utilized to evaluate the correlation among the raw and transformed HIV measures. Additionally, we calculated incidence rates of HL, SCCA, and HCC.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed to determine the individual effects of each of three different HIV measurements on the time to incident HL, SCCA, and HCC. Separate crude and multivariable regression models were fit for each different HIV measure and NADM, respectively. To adjust for potential confounding, covariates were selected for multivariable regression models based on clinical relevance. These variables were age at HIV diagnosis, race/ethnicity, illicit drug use (defined by ICD-9 code), Deyo modification of the Charlson comorbidity index (excluding points allotted for HIV diagnosis), and the HIV diagnosis era (e.g., pre-cART 1985-1995, early-cART 1996-2001, late-cART 2002-2010). Initial immune function was estimated using nadir CD4 count before cART initiation. For individuals who received cART concurrent with the earliest HIV diagnosis, the first CD4 count was captured as the nadir. Time-updated CD4 has been shown to be associated with cancer risk and was included to describe fluctuating immune status throughout the follow-up period. Additional variables representing diagnoses of well-documented risk factors were included in models evaluating HCC (i.e., hepatitis C virus, cirrhosis) and SCCA (i.e., condyloma). Akaike information criterion assessed model fit.20 Analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.1.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participant characteristics for 31,576 HIV-infected veterans who met inclusion criteria (Figure 1) and for strata defined by NADM diagnosis are provided in Table 1. Mean age at HIV diagnosis was 45 years (SD=10). Over one-half were racial/ethnic minorities. 35% had used illicit drugs. HIV diagnoses were captured from 1985-2010. Most HIV diagnoses occurred in the late cART era, but a greater proportion of individuals with NADM were diagnosed with HIV before 1996 (43-48%; p<0.01).

Table 1. Characteristics of HIV-infected male veterans who received any cART, stratified by NADM.

| Overall N=31,576 | HL n=211 | SCCA n=373 | HCC n=383 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HIV diagnosis [mean (SD)] | 45 (10) | 44(10) | 42 (10) | 47 (8) |

| HIV RNA Load [mean (SD)] | 40687 (185182) | 48719 (123786) | 37426 (148064) | 23386 (94935) |

| % undetectable HIV RNA [mean (SD)] | 49 (34) | 31 (32) | 33 (31) | 44 (31) |

| HIV copy-years viremia [mean (SD)] | 212743 (467984) | 145359 (297232) | 328641 (654596) | 145893 (336380) |

|

| ||||

| N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 12043 (38) | 83 (39) | 225 (60) | 131 (34) |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 15610 (49) | 103 (49) | 124 (33) | 193 (51) |

| Hispanic | 2396 (8) | 23 (11) | 15 (4) | 50 (13) |

| Other | 1527 (5) | 2 (1) | 9 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Year of first HIV diagnosis | ||||

| Pre-cART 1985-1995 | 9200 (29) | 92 (44) | 178 (48) | 163 (43) |

| Early cART 1996-2001 | 9672 (31) | 76 (36) | 128 (34) | 132 (34) |

| Late cART 2002-2010 | 12704 (40) | 43 (20) | 67 (18) | 88 (23) |

| Use of illicit drugs | ||||

| No | 20680 (65) | 148 (70) | 287 (77) | 204 (53) |

| Yes | 10896 (35) | 63 (30) | 86 (23) | 179 (47) |

| DEYO without AIDS co-morbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 16600 (53) | 127 (66.9) | 215 (58) | 196 (51) |

| 1 | 9222 (29) | 43 (22.6) | 113 (30) | 122 (32) |

| 2 and above | 5754 (18) | 20 (10.5) | 45 (12) | 65 (17) |

| Nadir CD4 count prior to cART | ||||

| CD4 < 200 | 14300 (45) | 106 (50) | 247 (66) | 179 (47) |

| CD4 200-350 | 8701 (28) | 56 (27) | 77 (21) | 116 (30) |

| CD4 > 350 | 8575 (27) | 49 (23) | 49 (13) | 88 (23) |

|

| ||||

| CD4 count at time of event/censor | ||||

|

| ||||

| CD4 < 200 | 8179 (26) | 60 (30) | 118 (32) | 116 (30) |

| CD4 200-350 | 5895 (19) | 62 (31) | 101 (27) | 100 (26) |

| CD4 > 350 | 17493 (55) | 80 (39) | 153 (41) | 167 (44) |

HL=Hodgkin lymphoma; SCCA=Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus; HCC=Hepatocellular carcinoma; cART=combination antiretroviral therapy

Overall, 45% of individuals, but 66% of SCCA cases (p<0.01), had a CD4 nadir before cART initiation <200 cells/μL, Over the study interval, mean recent CD4 was 427 cells/μL (SD=284). At the end of follow-up (e.g., censoring/death, NADM diagnosis), 55% of the cohort had CD4 >350. The mean number of HIV measurements collected annually per individual was 3.2 (SD=3.1), and on average, each individual contributed 9 years (SD=5) of follow-up. At the time of NADM or censoring, the mean recent HIV RNA was 40,687 copies/mL (SD=185,182), highest among HL cases (mean=48,719; SD=123,896). At the final study observation, the mean % time undetectable HIV RNA was 49% (SD=34%). Overall, 27% had % time undetectable HIV <20%, but 52% of HL cases and 43% of SCCA cases experienced this low level of viral load control (p<0.01). The mean HIV copy-years was 212,743 (SD=467,984), overall, and was highest among SCCA (mean=328,641; SD=654,596).

Table 2 describes rank correlations between the different HIV measurements utilized in the current analyses. All correlations were in the projected directions (e.g., recent HIV and HIV copy-years were directly correlated with one another and inversely correlated with % time undetectable HIV). While correlations between different measures varied in strength, all correlations were statistically significant (p<0.01).

Table 2. Spearman rank correlations between measures of HIV viremia.

| Recent HIV RNA Load | % undetectable HIV RNA | HIV copy-years viremia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Recent HIV RNA Load (Log10, copies/mL) | 1.00 | ||

| 2. % undetectable HIV RNA (<20, 20-39, 40-59, 60-79, ≥80%) | −0.51 | 1.00 | |

| 3. HIV copy-years viremia (Log10, copy-years/mL) | 0.35 | −0.53 | 1.00 |

Note: p-values for all correlations were statistically significant (p<0.01)

Association between HIV RNA load measures and NADM incidence

During the study interval, 383 HCC (Incidence rate (IR) =133/100,000 person-years; 95%CI=124-142/100,000), 211 HL (IR=70/100,000 person-years; 95%CI=59-79/100,000), and 373 SCCA (IR=129/100,000 person-years; 95%CI=119-138/100,000) were diagnosed. The unadjusted associations of the three HIV RNA measures with HCC, SCCA, and HL incidence are provided in Table 3. HIV copy-years was a significant predictor of NADM hazard. Per log-10 copy-years/mL increase in cumulative HIV, there was a significant increase in HL (HR=1.26; 95%CI=1.11-1.42), SCCA (HR=1.48; 95%CI=1.33-1.66), and HCC (HR=1.15; 95%CI=1.05-1.26).

Table 3. Crude hazard ratio for non-AIDS-defining cancers by different HIV exposure metrics.

| HL | SCCA | HCC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Recent HIV RNA Load | |||||||||

| Log10, copies/mL | 1.06 | 1.01-1.11 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.98-1.06 | 0.26 | 0.95 | 0.91-0.99 | 0.01 |

| % undetectable HIV RNA | |||||||||

| <20% | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 20-39% | 0.95 | 0.60-1.51 | 0.83 | 1.08 | 0.82-1.43 | 0.58 | 1.39 | 1.02-1.89 | 0.04 |

| 40-59% | 0.72 | 0.43-1.19 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.61-1.15 | 0.27 | 2.01 | 1.50-2.68 | <0.01 |

| 60-79% | 0.68 | 0.42-1.09 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 0.47-0.99 | 0.04 | 1.55 | 1.11-2.16 | <0.01 |

| ≥80% | 0.63 | 0.44-0.89 | <0.01 | 0.74 | 0.53-1.02 | 0.07 | 1.56 | 1.14-2.12 | <0.01 |

| HIV copy-years viremia | |||||||||

| Log10, copies × years/mL | 1.26 | 1.11-1.42 | 0.0003 | 1.48 | 1.33-1.66 | <0.0001 | 1.15 | 1.05-1.26 | 0.01 |

HL=Hodgkin lymphoma; SCCA=Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus; HCC=Hepatocellular carcinoma.

The results from separate Cox regression models for each HIV RNA measure, adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, illicit drug use, era of HIV diagnosis, comorbidity, and pre-treatment nadir and recent CD4, are described in Table 4 (additional covariates included in SCCA (i.e., condyloma) and HCC (i.e., cirrhosis, hepatitis C) models). In the adjusted models, the relationship between NADM hazard and recent HIV RNA was not statistically significant. However, the association between the two cumulative HIV RNA measures and HL and SCCA hazard was robust to multivariate adjustment. Compared to individuals with <20% time undetectable HIV RNA, individuals with ≥80% time undetectable had a decreased hazard for HL (adjusted HR=0.62; 95%CI=0.37-1.02) and SCCA (aHR=0.64; 95%CI=0.44-0.93). The relationship between HIV copy-years and HL and SCCA was also significant. HL (aHR=1.22; 95%CI=1.06-1.40) and SCCA (aHR=1.36; 95%CI=1.21-1.52) hazard increased per log-10 increase in HIV copy-years. The results from analyses of HCC did not support a relationship between HIV RNA exposure and HCC risk. A comprehensive table of results from each of the adjusted models, complete with all covariates, has been provided as an online supplement (see Appendix 1).

Table 4. Adjusted hazard ratio for non-AIDS-defining cancers by different HIV exposure metrics.

| HL | SCCAa | HCCb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Recent HIV RNA Load | |||||||||

| Log10, copies/mL | 1.00 | 0.94-1.05 | 0.88 | 1.01 | 0.97-1.05 | 0.60 | 0.96 | 0.92-1.00 | 0.06 |

| % undetectable HIV RNA | |||||||||

| <20% | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 20-39% | 0.85 | 0.56-1.29 | 0.44 | 1.05 | 0.79-1.40 | 0.73 | 1.27 | 0.93-1.74 | 0.13 |

| 40-59% | 0.67 | 0.41-1.10 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.58-1.13 | 0.21 | 1.81 | 1.94-2.44 | <0.01 |

| 60-79% | 0.84 | 0.51-1.37 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.42-0.93 | 0.02 | 1.28 | 0.90-1.82 | 0.18 |

| ≥80% | 0.62 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.44-0.93 | 0.02 | 1.39 | 0.98-1.99 | 0.07 |

| HIV copy-years viremia | |||||||||

| Log10, copies × years/mL | 1.22 | 1.06-1.40 | 0.005 | 1.36 | 1.21-1.52 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 0.93-1.13 | 0.67 |

HL=Hodgkin lymphoma; SCCA=Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus; HCC=Hepatocellular carcinoma. All adjusted regression models included the following additional variables: age at HIV diagnosis, race/ethnicity, use of illicit drugs, era of HIV diagnosis (pre-cART, early cART, late cART), Deyo modification of the Charlson comorbidity index, nadir CD4 count (prior to cART initiation), and recent CD4 count.

Regression model for SCCA also included condyloma.

Regression model for HCC also included hepatitis C and cirrhosis.

Comparison of model fit between different HIV RNA metrics

Model fit was evaluated using Akaike information criterion. The difference between models incorporating each distinct HIV exposure variable was small. However, in each scenario, the HIV copy-years model was slightly superior, suggesting improved prognostic significance (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to compare the relationship between cross-sectional and cumulative HIV metrics and the time to incidence of individual virally-associated NADM. Principally, results indicated elevated cumulative HIV exposure was associated with HL and SCCA incidence among our sample. The relationship with HCC was less stable. Additionally, compared to non-cumulative recent HIV RNA level, cumulative HIV copy-years provided better-fitting models to predict time to NADM incidence. Our findings suggest not all NADM are the same, but provide initial evidence to support a potential role for cumulative HIV in monitoring the development of certain virally-associated NADM.

Research has shown cumulative HIV measures are associated with mortality 11 and ADM diagnosis.13,21 Mugavero et al examined the association between cumulative HIV and all-cause mortality.11 The authors reported higher cumulative HIV copy-years increased the risk of death. Additionally, another study evaluated the effect of cumulative HIV, as the duration in years of HIV exposure >500 copies/mL, on any ADM or NADM diagnosis, respectively.21 The authors observed longer HIV exposure was associated with increased ADM incidence but not NADM. However, there were few NADM events and the study was not powered to investigate virally-associated or individual NADM diagnoses separately. In another recent study of cART and non-cART users, we observed higher % time undetectable HIV RNA was associated with decreased SCCA risk.22 However, this study did not assess different HIV measures or other NADM.

In the current study, HL and SCCA risk increased with higher cumulative HIV copy-years and decreased with better % time undetectable HIV. The underlying mechanisms explaining the association between HIV and NADM remain unclear. However, HIV may directly affect oncogenesis via tissue, cellular, or genetic mechanisms.23-25 Additionally, persistent replication, as noted by cumulative HIV, is associated with immunodeficiency and dampened clearance of latent viral coinfections (e.g., EBV, HPV, HHV8), potentially predisposing individuals to malignancies caused by other oncogenic viruses.26

HIV-related HL is known to be associated with Epstein-Barr virus coinfection.27 Previous research has suggested EBV levels may remain high under conditions of insufficient HIV control.28 Therefore, cumulative HIV may indicate underlying EBV burden. Friis et al 29 suggested that even after cART initiation, it may take 1-2 years or longer to achieve effective EBV control. Additionally, HIV antigens are known to drive B-cell stimulation. In turn, chronic stimulation leads to uncontrolled B-cell division, possibly boosting the opportunity for malignant clone development and expansion.30

HIV-related SCCA is also associated with persistent oncogenic viral infection, namely human papillomavirus (HPV).31,32 HIV-infected individuals are more likely than non-infected individuals to have anal HPV infection, including infection with multiple and high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes, even in the absence of anal intercourse.33-35 HIV-infected individuals also experience longer durations of persistent HPV infection.33 HPV proliferation involves a coordinated and complex interaction between HPV oncoproteins and Rb, p53 and other targets.36 Similar to EBV, persistent HPV infection has been observed to be associated with HIV proliferation and cellular immune deficit.37 Additional evidence suggests HIV and HPV genes reciprocally interact, either directly or via cytokine-mediated mechanisms, resulting in increasing amounts of HPV and enhancing the potential for malignant progression.10

HIV impacted HCC development differently than other virally-associated NADM studied. HIV has been shown to accelerate cirrhosis development.38 However, in the current study, there was not a significant relationship between HIV and HCC, independent of cirrhosis. It is possible that the interface between HIV and HCV at the cellular level may be less direct than what occurs between HIV and EBV or HPV. Additionally, there may be effects of cART on HCV and HBV burden not captured here.

Our results highlight the effects of cumulative HIV on HL and SCCA incidence, independent of measured covariates, and support previous hypotheses that HL and SCCA may be different than other NADM.39 Additionally, our results coincide with previous population-based findings12,40 and support previous molecular observations regarding the relationships between HIV and the proliferation of other oncogenic viruses.10,28 The two cumulative measurements evaluated in the current study provide information about the overall impact of intermittently-controlled or continuous HIV replication using opposing methodologies. Specifically, one approach captures HIV directly while the other illustrates the absence of viremia. The relationships between each measure and cancer incidence were representative of this pattern. However, HIV copy-years provided improved model fit. One difference and potential advantage of HIV copy-years is the measure's ability to more exactly quantify the duration of exposure over time. For future studies, this level of precision may be the best measure of cumulative HIV to incorporate into risk stratification for ADM, HL and SCCA.

The findings from the current study should be viewed within the context of the study design. The retrospective cohort study design employed may be subject to unmeasured confounders (e.g., smoking). However, lifestyle factors such as smoking have not been shown to effect changes in HIV load.41 Additionally, all individuals included in the current sample had received cART, but the type and duration of treatment regimens received were not measured. Data for the present study was extracted from a national, system-wide VA registry of HIV-infected veterans. A principal strength was this resource provides one of the largest data repositories of HIV-infected individuals. However, certain limitations are inherent in such large registry databases. Most relevant to our analyses were potential variations in follow-up visit frequency. We attempted to reduce the potential for information bias by segmenting the follow-up period into one-week intervals, establishing equivalent visit frequencies per individual. However, some individuals may have experienced longer intervals without updated HIV measurements. In our data, the average number of HIV measurements collected annually was over 3 and was not different between NADM cases and non-cases. Finally, this study was conducted exclusively on male veterans, which may have implications on the generalizability of its findings.

In the current sample of HIV-infected male veterans, uncontrolled HIV replication, as indicated by cumulative HIV copy-years and % time undetectable HIV RNA, was associated with HL and SCCA development, independent of measured covariates. Cumulative HIV copy-years demonstrated the most robust association with the cancers studied and may provide the most sensitive metric to better describe the impact of HIV viremia and underlying viral coinfection. Thus, copy-years may be the most appropriate measure of HIV viral load control for future epidemiologic research assessing HIV-associated outcomes. Additional research is needed to define implementation strategies for cumulative HIV measurements as a screening tool for virally-associated cancers associated with chronic HIV infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This work was supported in part by resources and the use of facilities at the Houston Health Services Research and Development Center of Innovation (HFP90-020), Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Baylor College of Medicine Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center (P30CA125123-04S1). This research was also supported by the Baylor-UTHouston Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (AI036211). EYC (R01CA163103) also received support from the NCI. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of this report.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Clifford GM, Polesel J, Rickenbach M, et al. Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: associations with immunodeficiency, smoking, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Mar 16;97(6):425–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herida M, Mary-Krause M, Kaphan R, et al. Incidence of non-AIDS-defining cancers before and during the highly active antiretroviral therapy era in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 15;21(18):3447–3453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006 Aug 1;20(12):1645–1654. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238411.75324.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS, et al. Incidence of types of cancer among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population in the United States, 1992-2003. Ann Intern Med. 2008 May 20;148(10):728–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Grabar S, et al. Marked increase in the incidence of invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected patients despite treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2008 Jun 19;22(10):1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283023f78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Souza G, Wiley DJ, Li X, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of anal cancer in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Aug 1;48(4):491–499. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817aebfe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smukler AJ, Ratner L. Hepatitis viruses and hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002 Sep;14(5):538–542. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200209000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka PY, Pessoa VP, Jr, Pracchia LF, Buccheri V, Chamone DA, Calore EE. Hodgkin lymphoma among patients infected with HIV in post-HAART era. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007 Mar;7(5):364–368. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2007.n.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1 Suppl):S6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolei A, Curreli S, Marongiu P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro activates naturally integrated human papillomavirus type 18 and induces synthesis of the L1 capsid protein. J Gen Virol. 1999 Nov;80(Pt 11):2937–2944. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-11-2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, Cole SR, et al. Viremia copy-years predicts mortality among treatment-naive HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. Nov;53(9):927–935. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole SR, Napravnik S, Mugavero MJ, Lau B, Eron JJ, Jr, Saag MS. Copy-years viremia as a measure of cumulative human immunodeficiency virus viral burden. Am J Epidemiol. Jan 15;171(2):198–205. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoufaly A, Stellbrink HJ, Heiden MA, et al. Cumulative HIV viremia during highly active antiretroviral therapy is a strong predictor of AIDS-related lymphoma. J Infect Dis. 2009 Jul 1;200(1):79–87. doi: 10.1086/599313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabresi A, Ferraresi A, Festa A, et al. Incidence of AIDS-defining cancers and virus-related and non-virus-related non-AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-infected patients compared with the general population in a large health district of Northern Italy, 1999-2009. HIV medicine. 2013 Sep;14(8):481–490. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007 Jul 7;370(9581):59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Backus L, Mole L, Chang S, Deyton L. The Immunology Case Registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Dec;54(Suppl 1):S12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Backus LI, Gavrilov S, Loomis TP, et al. Clinical Case Registries: simultaneous local and national disease registries for population quality management. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009 Nov-Dec;16(6):775–783. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisson GP, Gross R, Bellamy S, et al. Pharmacy refill adherence compared with CD4 count changes for monitoring HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Med. 2008 May 20;5(5):e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bangsberg DR, Kroetz DL, Deeks SG. Adherence-resistance relationships to combination HIV antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007 May;4(2):65–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruyand M, Thiebaut R, Lawson-Ayayi S, et al. Role of uncontrolled HIV RNA level and immunodeficiency in the occurrence of malignancy in HIV-infected patients during the combination antiretroviral therapy era: Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida (ANRS) CO3 Aquitaine Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Oct 1;49(7):1109–1116. doi: 10.1086/605594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiao EY, Hartman CM, El-Serag HB, Giordano TP. The impact of HIV viral control on the incidence of HIV-associated anal cancer. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2013 Aug 15;63(5):631–638. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182968fa7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amini S, Khalili K, Sawaya BE. Effect of HIV-1 Vpr on cell cycle regulators. DNA Cell Biol. 2004 Apr;23(4):249–260. doi: 10.1089/104454904773819833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo HG, Pati S, Sadowska M, Charurat M, Reitz M. Tumorigenesis by human herpesvirus 8 vGPCR is accelerated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. J Virol. 2004 Sep;78(17):9336–9342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9336-9342.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrod R, Nacsa J, Van Lint C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Tat/co-activator acetyltransferase interactions inhibit p53Lys-320 acetylation and p53-responsive transcription. J Biol Chem. 2003 Apr 4;278(14):12310–12318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engels EA. Non-AIDS-defining malignancies in HIV-infected persons: etiologic puzzles, epidemiologic perils, prevention opportunities. AIDS. 2009 May 15;23(8):875–885. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328329216a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Gulley ML, et al. Population-based patterns of human immunodeficiency virus-related Hodgkin lymphoma in the Greater San Francisco Bay Area, 1988-1998. Cancer. 2003 Jul 15;98(2):300–309. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Righetti E, Ballon G, Ometto L, et al. Dynamics of Epstein-Barr virus in HIV-1-infected subjects on highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002 Jan 4;16(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friis AM, Gyllensten K, Aleman A, Ernberg I, Akerlund B. The Effect of Antiretroviral Combination Treatment on Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Genome Load in HIV-Infected Patients. Viruses. Apr;2(4):867–879. doi: 10.3390/v2040867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolcetti R, Boiocchi M, Gloghini A, Carbone A. Pathogenetic and histogenetic features of HIV-associated Hodgkin's disease. Eur J Cancer. 2001 Jul;37(10):1276–1287. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palefsky JM. Cutaneous and genital HPV-associated lesions in HIV-infected patients. Clin Dermatol. 1997 May-Jun;15(3):439–447. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(96)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin-Hong PV, Palefsky JM. Natural history and clinical management of anal human papillomavirus disease in men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Nov 1;35(9):1127–1134. doi: 10.1086/344057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, Kuypers JM, et al. Effect of HIV infection on the natural history of anal human papillomavirus infection. AIDS. 1998 Jul 9;12(10):1177–1184. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199810000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piketty C, Darragh TM, Da Costa M, et al. High prevalence of anal human papillomavirus infection and anal cancer precursors among HIV-infected persons in the absence of anal intercourse. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Mar 18;138(6):453–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-6-200303180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott M, Nakagawa M, Moscicki AB. Cell-mediated immune response to human papillomavirus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001 Mar;8(2):209–220. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.2.209-220.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. Aug;10(8):550–560. doi: 10.1038/nrc2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arany I, Tyring SK. Systemic immunosuppression by HIV infection influences HPV transcription and thus local immune responses in condyloma acuminatum. Int J STD AIDS. 1998 May;9(5):268–271. doi: 10.1258/0956462981922197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Audsley J, du Cros P, Goodman Z, et al. HIV replication is associated with increased severity of liver biopsy changes in HIV-HBV and HIV-HCV co-infection. J Med Virol. Jul;84(7):993–1001. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stebbing J, Duru O, Bower M. Non-AIDS-defining cancers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;22(1):7–10. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283213080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guiguet M, Boue F, Cadranel J, Lang JM, Rosenthal E, Costagliola D. Effect of immunodeficiency, HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy on the risk of individual malignancies (FHDH-ANRS CO4): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Dec;10(12):1152–1159. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabali C, Cheng DM, Brooks DR, Bridden C, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Samet JH. Recent cigarette smoking and HIV disease progression: no evidence of an association. AIDS Care. Aug;23(8):947–956. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.