Abstract

Background

The diagnosis of breast cancer in combination with the anticipation of surgery evokes fear, uncertainty, and anxiety in most women.

Objective

In patients who underwent breast cancer surgery, study purposes were to examine how ratings of state anxiety changed from the time of the preoperative assessment to 6 months after surgery and to investigate whether specific demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics predicted the preoperative levels of state anxiety and/or characteristics of the trajectories of state anxiety.

Interventions/Methods

Patients (n=396) were enrolled preoperatively and completed the Spielberger State Anxiety inventory monthly for six months. Using hierarchical linear modeling, demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics were evaluated as predictors of initial levels and trajectories of state anxiety.

Results

Patients experienced moderate levels of anxiety prior to surgery. Higher levels of depressive symptoms and uncertainty about the future, as well as lower levels of life satisfaction, less sense of control, and greater difficulty coping predicted higher preoperative levels of state anxiety. Higher preoperative state anxiety, poorer physical health, decreased sense of control, and more feelings of isolation predicted higher state anxiety scores over time.

Conclusions

Moderate levels of anxiety persist in women for six months following breast cancer surgery.

Implications for Practice

Clinicians need to implement systematic assessments of anxiety to identify high risk women who warrant more targeted interventions. In addition, ongoing follow-up is needed in order to prevent adverse postoperative outcomes and to support women to return to their preoperative levels of function.

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of breast cancer in combination with the anticipation of surgery evokes fear, uncertainty, and anxiety in most women. Previous research found that the majority of women with breast cancer experience moderate to high levels of anxiety before surgery followed by a gradual reduction over the year after surgery.1–12 Unfortunately, direct comparisons across these prevalence studies are not possible due to differences in the use of generic or symptom specific measures to assess anxiety, differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as differences in the number and timing of the assessments.

In an effort to improve early detection of anxiety in women undergoing breast cancer surgery, a number of demographic and clinical characteristics were evaluated to determine their associations with this symptom. Across these studies, being younger,3,10,13,14 and having children3 increased a woman’s risk for psychological morbidity in the year after breast cancer surgery. Furthermore, in one study,10 women who were married or partnered were less likely to experience distress than women who were single, divorced, or widowed. However, in another study, this association was not significant.3 Finally, no association was found between years of education and patterns of distress in women undergoing breast cancer surgery.12,13,15

Findings regarding the relationships between clinical characteristics and psychological distress prior to and following surgery are inconsistent. In some studies, tumor size and stage of disease were not associated with psychological distress before or after surgery,13–16 whereas in others studies a positive association was found.5,12 In addition, no differences in psychological adjustment were found between women undergoing breast conserving surgery compared to mastectomy.4,6,9,10,16 In contrast, adjuvant treatment,3,16 as well as postmenopausal status,3 and physical complaints (e.g., fatigue, pain) in the period after surgery3,12,16–18 were associated with higher levels of psychological distress.

Findings from several studies suggest that various psychosocial adjustment characteristics may contribute to the severity and trajectories of psychological distress before and after breast cancer surgery. In fact, personality characteristics, such as neuroticism, are associated with higher levels of distress across various phases of the disease trajectory.9,19 Similarly, coping mechanisms,13,20 perceived social support,5 sense of control,5,17,21 and illness perceptions9 influence levels of anxiety after breast cancer surgery. Of note, a psychiatric history3,15 and increased levels of preoperative or immediate postoperative distress3,5,9,22 predicted worse psychological outcomes after surgery.

The primary limitation of the aforementioned studies on changes in distress after breast cancer surgery is that these studies used general measures of “psychological distress” that do not provide specific information on anxiety separate from other distressing symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms). In order to delineate the type of distress women face and to be able to assist patients during the recovery period, instruments specific for anxiety (e.g., Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)23) need to be used before and after surgery. In addition, newer methods of longitudinal data analysis (e.g., hierarchical linear modeling (HLM)) can be used to identify predictors of initial levels and trajectories of anxiety.24,25

Given the paucity of longitudinal studies that used a symptom specific measure of anxiety, the purposes of this study, in a sample of women who underwent breast cancer surgery, were to examine how ratings of state anxiety changed from the time of the preoperative assessment to 6 months after surgery and to investigate whether specific demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics predicted the preoperative levels of state anxiety and/or characteristics of the trajectories of state anxiety over a period of 6 months after the surgery.

METHODS

Participants and Settings

This descriptive, longitudinal study is part of a larger study that evaluated for neuropathic pain and lymphedema in women who underwent breast cancer surgery.26–28 Patients were recruited from Breast Care Centers located in a Comprehensive Cancer Center, two public hospitals, and four community practices in Northern California.

Patients were eligible to participate if they were adult women (≥18 years) who would undergo breast cancer surgery on one breast; were able to read, write, and understand English; agreed to participate; and gave written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were having breast cancer surgery on both breasts and/or had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

A total of 516 patients were approached and 410 enrolled in the study (response rate 79.5%). For the current analysis, complete data from 396 women were available. For those women who declined participation, the major reasons for refusal were: too busy, overwhelmed with their cancer diagnosis, or insufficient time available to complete the baseline assessment prior to surgery.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for the overall study was the Theory of Symptom Management (TSM),29–31 which was developed by faculty members in the Center for Symptom Management at UCSF. In this model, the symptom experience includes an individual’s perception of the symptom, evaluation of the meaning of the symptom, and response to the symptom. The symptom management strategies dimension includes both self-care strategies individuals do for themselves, as well as the treatments that clinicians prescribe. The outcomes dimension specifies that outcomes emerge from the symptom management strategies as well as from the symptom experience. The TSM places the experience of symptom management in the context of the domains of nursing science, namely person, health and illness, and environment.

In this specific analysis, the symptom experience dimension of the theory was evaluated in that patients’ perceptions of anxiety were assessed prior to and for six months after breast cancer surgery. As was done in previous HLM analyses of other symptoms,25,32–36 the experience of anxiety was evaluated within the context of the person (i.e., demographic characteristics) and health and illness (i.e., clinical characteristics, other symptoms associated with cancer treatment, psychosocial adjustment characteristics) domains of nursing science.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, gender, marital status, education, ethnicity, employment status, and financial status. Patient’s functional status was assessed using the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale, which ranges from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal, I have no complaints or symptoms). The KPS has well established validity and reliability.37

The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) is a short and easily understood instrument that was developed to measure comorbidity in clinical and health service research settings.38 The questionnaire consists of 13 common medical conditions that were simplified into language that could be understood without any prior medical knowledge. Patients were asked to indicate if they had the condition using a “yes/no” format. If they indicated that they had a condition, they were asked if they received treatment for it (proxy for disease severity) and did it limit their activities (indication of functional limitations). Patients were given the option to add two additional conditions not listed on the instrument. For each condition, a patient can receive a maximum of 3 points. Because the SCQ contains 13 defined medical conditions and 2 optional conditions, the maximum score totals 45 points if the open-ended items are used and 39 points if only the closed-ended items are used. The SCQ has well-established validity and reliability and has been used in studies of patients with a variety of chronic conditions.39–41

The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI-T, STAI-S) consist of 20 items each that are rated from 1 to 4. Scores for each scale are summed and can range from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates greater anxiety. The STAI-T measures an individual’s predisposition to anxiety determined by his/her personality and estimates how a person generally feels. The STAI-S measures an individual’s transitory emotional response to a stressful situation. It evaluates the emotional responses of worry, nervousness, tension, and feelings of apprehension related to how a person feels “right now” in a stressful situation. Cutoff scores of ≥31.8 and ≥32.2 indicate high levels of trait and state anxiety, respectively.23 The STAI-S and STAI-T inventories have well-established criterion and construct validity and internal consistency reliability coefficients.42,43 In this study, Cronbach’s alphas for the STAI-T and STAIS were .88 and .95, respectively.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) consists of 20 items selected to represent the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores of ≥16 indicating the need for individuals to seek clinical evaluation for major depression. The CES-D has well-established validity and reliability.44–46 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D was 0.90.

The Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS) consists of 18 items designed to assess physical fatigue and energy.47 Each item was rated on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (NRS). Total fatigue and energy scores were calculated as the mean of the 13 fatigue items and the 5 energy items. Higher scores indicate greater fatigue severity and higher levels of energy. Respondents were asked to rate each item based on how they felt “right now”. The LFS has been used with healthy individuals47,48 and in patients with cancer and HIV disease.49–52 A cutoff score of ≥4.4 indicates high levels of fatigue.24 A cutoff score of ≤4.8 indicates low levels of energy.24 The LFS has well established validity and reliability. In this study, Cronbach’s alphas for fatigue and energy scales were .96 and .93, respectively.

The Attentional Function Index (AFI) is a commonly used self-report measure of attentional function.53 It consists of 16-items that were rated on a 0 to 10 NRS. A higher mean score indicates greater capacity to direct attention.53,54 Scores are grouped into categories of attentional function (i.e., <5.0 low function, 5.0 to 7.5 moderate function, >7.5 high function).55 The AFI has well established reliability and validity.54,56 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the AFI was .95.

The General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) consists of 21 items designed to assess the quality of sleep in the past week. Each item was rated on a 0 (never) to 7 (everyday) NRS. The GSDS total score is the sum of 21 items that can range from 0 (no disturbance) to 147 (extreme sleep disturbance). A GSDS total score of ≥43 indicates a significant level of sleep disturbance.57 The GSDS has well-established validity and reliability in shift workers, pregnant women, and patients with cancer and HIV disease.58,59 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the GSDS total score was .86.

The occurrence of breast pain prior to surgery was determined by asking the question “Are you experiencing pain in your affected breast?” If women responded yes, they rated the severity of their average and worst pain using a 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) NRS. Women were asked how many days per week and how many hours per day they experienced significant pain (i.e., pain that interfered with function).

The Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version (QOL-PV) is a 41-item instrument that measures four dimensions of QOL in cancer patients (i.e., physical well-being, psychological well-being, spiritual well-being, social well-being), as well as a total QOL score. Each item was rated on a 0 to 10 NRS with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The QOL-PV has well established validity and reliability.60–62 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the QOL-PV total score was .86. For the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being subscales, the coefficients were 0.70, 0.79, 0.75, and 0.61, respectively.

Individual items from the QOL-PV were used to assess a number of psychosocial adjustment characteristics (i.e., life satisfaction, uncertainty, importance of spiritual activities, feelings of isolation, sense of control, difficulty coping). One item asked patients to rate their overall level of life satisfaction. One question asked patients to rate the amount of uncertainty they felt about the future. Another item asked about the importance of spiritual activities. One had them rate their feelings of isolation. Another question asked patients to rate the level of control they felt over their lives. Finally, one item asked patients to rate their difficulty coping as a result of the cancer and its treatment. Each item was rated using a 0 to 10 NRS with higher scores indicating a more positive appraisal of a particular characteristic. The specific items were chosen based on the review of the literature of psychosocial adjustment and anxiety in women with breast cancer.3,5,7–9,13,19,22

Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. During the patient’s preoperative visit, a clinical staff member explained the study to the patient and determined her willingness to participate. For those women who were willing to participate, the staff member introduced the patient to the research nurse. The research nurse met with the women, determined eligibility and obtained written informed consent prior to surgery. After obtaining consent, patients completed the enrollment questionnaires and average of four days prior to surgery and again at one, two, three, four, five, and six months after surgery. The research nurse met with the patients at the Clinical Research Center or in the patients’ homes.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated on the sample characteristics, baseline symptom severity scores, and psychosocial adjustment items using SPSS version 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY). With the exception of the STAI-S (which was assessed prior to surgery and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 months after surgery), all of the demographic, clinical, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics that were evaluated as predictors in the HLM analysis were assessed prior to surgery.

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), based on full maximum likelihood estimation, was done using the software developed by Raudenbush and colleagues.63,64 This analysis is discussed in detail in our previous publications. 25,32–36 In brief, the HLM analysis was done to evaluate for changes over time in ratings of state anxiety. During stage 1, intra-individual variability in state anxiety over time was examined. Three level 1 models were compared to determine whether the patients’ anxiety did not change over time (i.e., no time effect), changed at a constant rate (i.e., linear time effect), or changed at a rate that accelerated or decelerated over time (i.e., quadratic effect). At this point, the level 2 model was constrained to be unconditional (i.e., no predictors), and likelihood ratio tests were used to determine the best model.

The second stage of the HLM analysis examined inter-individual differences in the trajectories of state anxiety by modeling the individual change parameters (i.e., intercept, linear slope, quadratic slope) as a function of proposed predictors at level 2. Table 1 presents a list of the proposed predictors that was developed based on a review of the literature of anxiety in patients who underwent breast cancer surgery.1,3,5,7–9,12–14,16,18,19,22 To improve estimation efficiency and construct a model that is parsimonious, an exploratory level 2 analyses was completed in which each potential predictor was assessed to determine whether it would result in a better model if it alone were added as a level 2 predictor. Predictors with a t value of less than 2, which indicates a lack of significant effect, were dropped from subsequent model testing. All potential significant predictors from the exploratory analyses were entered into the model to predict each individual change parameter. Only predictors that maintained a statistically significant contribution in conjunction with other variables were retained in the final model. A p-value of <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 1.

Potential Predictors of the Intercept (I), Linear Coefficient (LC) and Quadratic Coefficient for Anxiety Using Preoperative Characteristics

| Characteristic | I | LC | QC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age | ■ | ||

| Lives alone | |||

| Education | |||

| Marital status | |||

| Ethnicity | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Employment status | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Body mass index | |||

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | ■ | ||

| Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | ■ | ■ | |

| Stage of disease | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| Type of surgery | |||

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | ■ | ■ | |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | |||

| Breast reconstruction at the time of surgery | |||

| Menopausal status | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy in first six months | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy in the first six months | ■ | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Trait anxiety score | ■ | ||

| State anxiety score | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale score | ■ | ■ | |

| Attentional Function Index score | ■ | ||

| Lee Fatigue Scale - Fatigue score | ■ | ||

| Lee Fatigue Scale - Energy score | ■ | ||

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale score | ■ | ||

| Presence of breast pain prior to surgery | |||

| Worst pain score | |||

| Average pain score | ■ | ||

| Number of days per week in pain | |||

| Number of hours per day in pain | |||

| Severity of hot flashes | |||

| Severity of changes in appetite | |||

| Psychosocial adjustment characteristics | |||

| Level of life satisfaction | ■ | ||

| Amount of uncertainty about the future | ■ | ■ | |

| Importance of spiritual activities | ■ | ■ | |

| Feelings of isolation | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Evaluation of overall physical health | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Control of things in your life | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Difficulty coping as a result of disease/treatment | ■ | ■ | ■ |

■ = From the exploratory analysis, had a t value of ≥2 and were included in subsequent model testing.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 396 patients are summarized in Table 2. On average, patients were 55 years of age, well educated, had a KPS score of 93, and an SCQ score of 4. Most of the women self-identified as White (64.6%), were post-menopausal (62.3%), and married or partnered (41.5%). Forty-eight percent of the patients were employed.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients (N = 396)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | 54.9 (11.6) |

|

| |

| Education (years) | 15.7 (2.7) |

|

| |

| Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | 4.3 (2.8) |

|

| |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 93.2 (10.3) |

|

| |

| Rate your overall physical health (0 = extremely poor to 10 = excellent)* | 7.1 (2.3) |

|

| |

| % | |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-white | 35.4 |

|

| |

| Married/partnered | 41.5 |

|

| |

| Lives alone | 24.1 |

|

| |

| Employed | 47.5 |

|

| |

| Postmenopausal | 62.3 |

|

| |

| Stage of disease | |

| Stage 0 | 18.3 |

| Stage I | 38.0 |

| Stage IIA, IIB | 35.4 |

| Stage IIA,IIIB,IIIC,IV | 8.3 |

|

| |

| Type of surgery | |

| Breast conversation | 79.9 |

| Mastectomy | 20.1 |

|

| |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | 82.4 |

|

| |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 37.4 |

|

| |

| Underwent reconstruction at time of surgery | 21.6 |

|

| |

| Received neoadjuvant therapy | 19.8 |

|

| |

| Received radiation therapy during the 6 months following surgery | 56.3 |

|

| |

| Received chemotherapy during the 6 months following surgery | 33.4 |

|

| |

| Experienced recurrence during the 6 months following surgery | 0.0 |

|

| |

| Mean symptom severity score at enrollment | Mean (SD) |

|

| |

| Trait anxiety score | 35.3 (8.8) |

|

| |

| State anxiety score | 41.8 (13.5) |

|

| |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression score | 13.7 (9.8) |

|

| |

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale score | 48.3 (21.6) |

|

| |

| Lee Fatigue Scale score | 3.1 (2.3) |

|

| |

| Lee Energy Scale score | 4.9 (2.5) |

|

| |

| Attentional Function Index score | 6.6 (1.9) |

|

| |

| Psychosocial Adjustment Characteristics from the QOL-PVa | |

|

| |

| How difficult is it for you to cope as a result of your disease and treatment? (0 = extremely difficult to 10 = not at all difficulty) | 6.7 (2.7) |

|

| |

| Do you feel like you are in control of things in your life? (0 = not at all to 10 = completely in control) | 6.1 (2.7) |

|

| |

| How satisfying is your life? (0 = not at all satisfied to 10 = completely satisfied) | 7.3 (2.6) |

|

| |

| How much isolation is caused by your illness or treatment? (0 = a great deal to 10 = none) | 8.0 (2.7) |

|

| |

| How important to you are other spiritual activities such as meditation? (0 = not at all important to 10 = very important) | 5.3 (3.8) |

|

| |

| How much uncertainty do you feel about the future? (0 = extreme uncertainty to 10 = not at all uncertain) | 5.0 (3.2) |

Items are listed as they are worded on the Quality of Life Scale – Patient Version (QOL-PV)

Abbreviation: SD = Standard deviation

Individual and Mean Change in State Anxiety

The first stage of HLM analysis examined how state anxiety changed from the time before surgery to 6 months after surgery. Two models were estimated in which the individual function of time was linear and quadratic. The goodness-of-fit tests of the deviance between the linear and the quadratic models indicated that a quadratic model had the best fit.

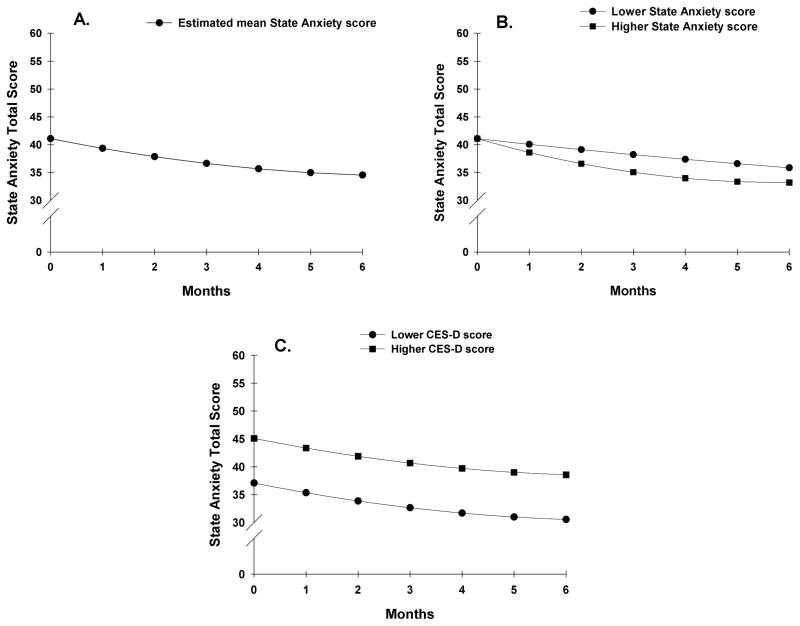

Table 3 presents the estimates of the unconditional, quadratic change model. Because the model had no covariates, the intercept represents the estimated level of state anxiety (i.e., 41.093 on a 20 to 80 scale) at the preoperative assessment. The estimated linear rate of change in state anxiety, for each additional month, was −1.86 (p<.000) and the estimated quadratic rate of change per month was 0.128 (p=.014). The weighted combination of the linear and quadratic terms defines each curve. Figure 1A displays the trajectory for anxiety from the preoperative assessment to 6 months after surgery. Anxiety decreased over the course of 6 months, with a larger decline during the first 3 months. It should be noted that the mean anxiety scores for the various groups depicted in all the figures are estimated or predicted means based on the HLM analysis.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Model of Anxiety

| Variable | Coefficient (SE)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | Final Model | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 41.093 (.634)d | 40.534 (.506)d |

| Timea (linear rate of change) | −1.861 (.352)d | −1.865 (.309)d |

| Time2 (quadratic rate of change) | .128 (.052)b | .129 (.047)c |

| Time invariant covariates | ||

| Intercept: | ||

| Receipt of chemotherapy | 1.639 (.737)b | |

| Depressive symptoms | .415 (.050)d | |

| Sense of control | −.831 (.227)d | |

| Life satisfaction | −.763 (.229)c | |

| Difficulty coping | −.746 (.212)d | |

| Level of uncertainty | −.426 (.130)c | |

| Linear: | ||

| Overall physical health × time | −.349 (.127)c | |

| Preoperative state anxiety × time | −.062 (.027)b | |

| Sense of control × time | .408 (.150)c | |

| Importance of spiritual activities × time | .190 (.071)c | |

| Difficulty coping × time | .362 (.153)b | |

| Sense of isolation × time | −.303 (.106)c | |

| Quadratic: | ||

| Overall physical health × time2 | .044 (.021)b | |

| Preoperative state anxiety × time2 | .008 (.004) | |

| Sense of control × time2 | −.065 (.023)c | |

| Importance of spiritual activities × time2 | −.030 (.012)c | |

| Difficulty coping × time2 | −.030 (.024) | |

| Sense of isolation × time2 | .046 (.017)c | |

| Variance components | ||

| In intercept | 111.756d | 30.677d |

| In linear rate | 18.876d | 8.081d |

| In quadratic fit | .281d | .106b |

| Goodness-of-fit deviance (parameters estimated) | 18373.726 (10) | 17981.296 (28) |

| Model comparison (x24) | 392.43 (18)d | |

Abbreviations: SE = Standard error

Time2 refers to the quadratic rate of change

p <.05;

p <.01;

p <.001

Time was coded zero at the time of the preoperative visit

Figure 1.

Trajectory of state anxiety as measured with the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory over the six months of the study (1A). Influence of preoperative state anxiety (1B) and depressive symptoms (1C) scores on inter-individual differences in state anxiety.

Inter-individual Differences in the Trajectories of Anxiety

The second stage of the HLM analysis evaluated how the pattern of change over time in state anxiety varied based on specific demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics (see Table 1 for specific variables evaluated). As shown in the final model in Table 3, the characteristics that predicted inter-individual differences in preoperative levels of state anxiety were total CES-D score; four psychosocial adjustment characteristics (i.e., sense of control of things in life, satisfaction with life, difficulty coping as a result of the disease and treatment, and amount of uncertainty); and receipt of CTX during the six months following surgery. The characteristics that predicted inter-individual differences in the slope parameters for state anxiety were self-report of overall physical health, state anxiety, sense of isolation, and importance of spiritual activities. The characteristics that predicted inter-individual differences in both the intercept and slope parameters were sense of control and difficulty coping.

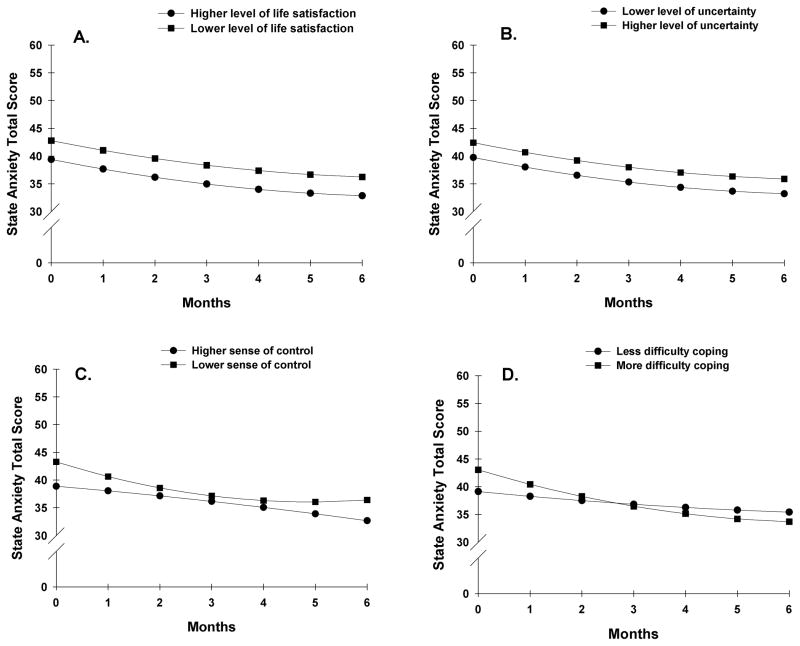

To illustrate the effects of the above predictors on patients’ initial levels and trajectories of state anxiety, Figures 1B and 1C display the adjusted change curves for state anxiety that were estimated based on differences in preoperative state anxiety (i.e., lower/higher state anxiety calculated based on one standard deviation [SD] below and above the mean STAI-T score) and CES-D score prior to surgery (i.e., lower/higher CES-D score calculated based on one SD above and below the mean CES-D score), respectively. Figures 2A and 2B display the adjusted change curves for state anxiety that were estimated based on differences in life satisfaction (i.e., higher/lower levels of life satisfaction calculated based on 1 SD above and below the mean level of life satisfaction) and levels of uncertainty (i.e., lower/higher levels of uncertainty calculated based on one SD above and below the mean level of uncertainty), respectively.

Figure 2.

Influence of preoperative ratings of life satisfaction (2A), uncertainty (2B), sense of control (2C), and difficulty coping (2D) on inter-individual differences in state anxiety.

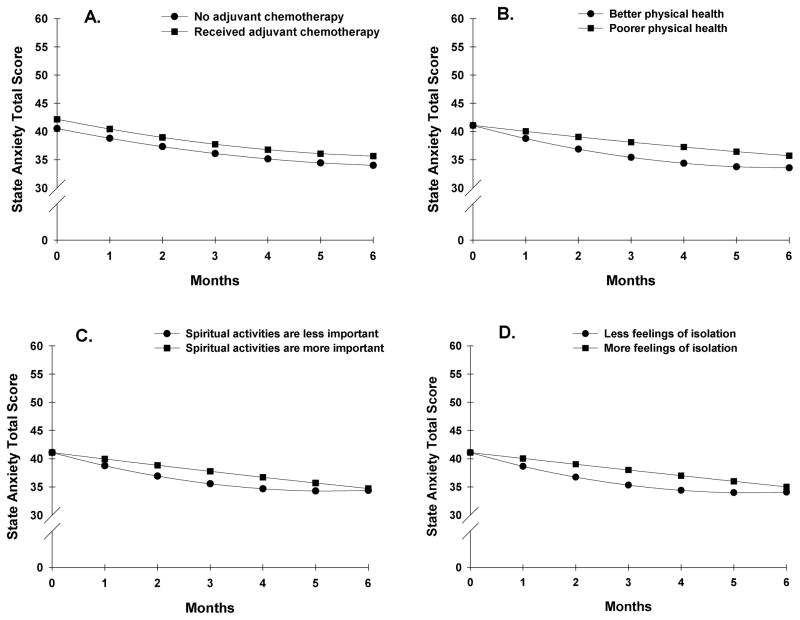

Figures 2C and 2D display the adjusted change curves for state anxiety that were estimated based on differences in sense of control and difficulty coping, respectively. Figures 3A through 3D display the adjusted change curves for state anxiety based on the following predictors: receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (3A), physical health (3B), importance of spiritual activities (3C), and feelings of isolation (3D).

Figure 3.

Influence of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (3A) and preoperative ratings of physical health (3B), importance of spiritual activities (3C), and feelings of isolation (3D) on inter-individual differences in state anxiety.

Discussion

This study is the first to use HLM to examine individual trajectories of state anxiety prior to and for 6 months following breast cancer surgery and to investigate whether demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics predicted preoperative levels and the trajectories of state anxiety over the period of 6 months. Consistent with previous reports,1–12 initial analyses found that on average, women who underwent surgery for breast cancer experienced declining levels of state anxiety during the 6 months following the surgery.

Prior to surgery, the average level of state anxiety was 41.1 (on a 20 to 80 scale), which is comparable to two studies that assessed state anxiety in women undergoing a variety of surgical procedures for breast cancer.10,65 As depicted in Figure 1A, and consistent with one report,10 gradual improvements in state anxiety occurred over the 6 months following surgery with an average STAI-S score of 34.6 at 6 months. Taken together, these findings suggest that women with breast cancer experience moderate levels of anxiety for several months following surgery.

Despite the overall decline in state anxiety, a large amount of inter-individual variability was found in preoperative levels of, as well as in changes in anxiety over time. As shown in Figure 1B, higher levels of state anxiety prior to surgery predicted a steeper decline in state anxiety following surgery than lower levels of preoperative state anxiety. However, trait anxiety was not a predictor of either initial levels of state anxiety or changes in state anxiety over the six months following breast cancer surgery. It is interesting to note that in several studies, neuroticism, which is associated with higher levels of state anxiety, was a predictor of poorer psychological adjustment in patients with breast cancer.7,9,19,66–68 It is possible that other psychosocial adjustment characteristics evaluated in this study (e.g., difficulty coping, sense of isolation) outweighed the effects of trait anxiety. Future studies need to evaluate how strongly neuroticism correlates with both preoperative levels of trait and state anxiety and whether this personality characteristic influences changes in anxiety.

While the mean preoperative CES-D score of the patients in this study was below the clinically meaningful cutoff, higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with higher levels of state anxiety before surgery that persisted over 6 months (Figure 1C). This finding is consistent with previous reports that found that higher preoperative levels of psychological distress were associated with poorer psychological outcomes after breast cancer surgery.3,5,16,21,69 Nevertheless, the use of valid questionnaires in this study, to assess both anxiety (i.e., STAI-S) and depressive symptoms (CES-D), in a large sample of patients with breast cancer, provides additional support for this association. The finding that preoperative levels of depressive symptoms and state anxiety independently predicted preoperative levels of or the postoperative trajectories of state anxiety, respectively, suggests that anxiety and depressive symptoms are distinct conditions that warrant independent assessments.70

Consistent with a previous report of patients who underwent general surgical procedures,71 lower levels of life satisfaction were associated with higher preoperative levels of state anxiety (Figure 2A). Kopp and colleagues noted that a high degree of life satisfaction was associated with a more optimistic view of the world.71 In addition, in studies of breast cancer survivors,7,72 optimistic personality was associated with higher levels of psychosocial well-being. Future studies need to examine the relationships among anxiety and personality characteristics (e.g., optimism) and life satisfaction in women undergoing breast cancer surgery.

Consistent with a previous report that found a positive association with uncertainty, assessed immediately after a mastectomy and anxiety after hospital discharge,73 higher levels of uncertainty about the future was associated with higher levels of preoperative anxiety (Figure 2B). Similarly, in a study of breast cancer survivors,74 uncertainty predicted worse psychosocial functioning. The observed relationship between uncertainty and preoperative levels of state anxiety adds support to Mishel’s theory of uncertainty of illness which postulates that higher levels of uncertainty are associated with poorer psychosocial adjustment and that interventions aimed at reducing uncertainty would have positive effects on this adjustment.75

Two psychosocial adjustment characteristics (i.e., sense of control (Figure 2C), difficulty coping (Figure 2D)) were found to be predictors of both the intercept and slope for state anxiety. As expected, a lower sense of control prior to surgery was associated with higher preoperative levels and a steeper decline in state anxiety. This finding is consistent with a previous study21 that found that the strongest predictor of a decline in psychological distress following breast cancer surgery was the rate of change in perceived control over a period of 12 months. These observations are in agreement with reported negative associations between psychological distress and perceived control in patients with a variety of cancer diagnoses.76

Similarly, higher ratings of difficulty coping as a result of the cancer diagnosis and its treatment were associated with higher levels of state anxiety prior to surgery and a slightly steeper decline in state anxiety over time. While the effect of this characteristic was relatively small, the findings are consistent with a study that evaluated the contribution of coping strategies to women’s levels of anxiety following a diagnosis of breast cancer.13 Lower levels of preoperative anxiety/depression, as well as the use of problem focused coping strategies were associated with lower levels of anxiety/depression at 3 months. However, because anxiety and depression were analyzed together one cannot determine which symptom made the larger contribution to women’s patterns of adjustment. Additional support for the inter-relationship between anxiety and difficulty coping comes from a study by Henselmans and colleagues17 who found that lower levels of mastery were associated with higher levels of psychological distress and that the effect of mastery on psychological distress was mediated by threat appraisals and coping self efficacy. Taken together, these findings suggest that an evaluation of women’s coping styles, as well as education on strategies to enhance coping skills might result in decreases in anxiety prior to and following breast cancer surgery.

Two psychosocial adjustment characteristics (i.e., importance of spiritual activities (Figure 3C), feelings of isolation (Figure 3D)) predicted only the slope parameters of the anxiety trajectory. In this study, women for whom spiritual activities were more important demonstrated a steady decline in state anxiety over 6 months after surgery. In contrast, for women for whom spiritual activities were less important, anxiety levels declined slightly more rapidly for about three months and then plateaued over the remaining three months (Figure 3C). Results from a longitudinal study on the role of spirituality in response to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer77 suggest that women who were less involved in spiritual/religious activities prior to the diagnosis of breast cancer and who attempted to mobilize these resources under the stress of diagnosis may experience a negative process of spiritual struggle and doubt that, in turn, has implications for their long-term adjustment. This observation may explain the predicted pattern of changes in anxiety in women in our study for whom spiritual activities were less important.

In this study, lower ratings of feelings of isolation predicted a slightly greater decline in anxiety symptoms over time compared to women who felt more isolated. This finding is congruent with results of a study that evaluated predictors of psychosocial adjustment in the year after a diagnosis of breast cancer.22 The presence of social support was the only variable that predicted successful adjustment to a diagnosis of breast cancer. Similarly, in a qualitative investigation of the needs of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer, psychosocial support was identified as one of these women’s greatest needs.78 These findings suggest that patients need to be instructed to mobilize their support systems and/or to participate in a breast cancer support group. In addition, nurses could support patients who live alone or do not have an extended social network through scheduled follow-up phone calls and/or home visits. Increased psychosocial support might reduce psychological distress in these women.

A suprising finding from this study is that in the final analysis, only two clinical and no demographic characteristic prediced baseline levels and trajectories of state anxiety. Consistent with previous reports,3, 6 women who received adjuvant chemotherapy reported higher levels of state anxiety throughout the study (Figure 3A). Patients’ ratings of their overall health during the preoperative visit (Figure 3B), predicted changes in the trajectory of state anxiety over the six months of the study. In this study, better ratings of overall physical health were associated with a slightly steeper decline in state anxiety scores over the 6 months following surgery. The small contribution of self-reported physical health to the trajectory of anxiety after surgery might be explained by the overall good health status of the patients in this study (i.e., high mean KPS score (i.e., 93.2 (10.3)), and the relatively low SCQ score (i.e., 4.3 (2.8)). The prospect of improving health status (e.g., with physical exercise) as a way to prevent anxiety after breast surgery presents an exciting area for future investigation.

While this longitudinal study evaluated changes in anxiety in a large sample of women using a valid and reliable measure for anxiety, a number of limitations need to be acknowledged. The generalizability of the study findings is limited primarily to Caucasian, middle-aged, and highly educated women who were diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Given that many of the women who declined to participate stated that they were too overwhelmed with the experience of cancer, the current study may have underestimated preoperative levels of state anxiety. Because the monthly assessments in the follow-up period were not scheduled at specific points in the patients’ treatment trajectory, times of higher psychological distress may have been missed.7,19,79 Finally, individual items of the QOL-PV scale were used as indicators of psychosocial adjustment. Despite the fact that these single items are valid measures of subjective states,80,81 multidimensional measures of the various psychosocial adjustment characteristics should be used in future studies.

Directions for Future Research

Taken together, these findings suggest that most of the women who undergo breast cancer surgery experience moderate levels of anxiety for 6 months following the surgical procedure. Additional research is warranted to determine for how long these moderate levels of anxiety persist and the impact of subsequent treatments on these patients’ level of anxiety. It is interesting to note that the majority of the predictors of anxiety were psychosocial adjustment characteristics and not demographic or clinical characteristics. These findings warrant replication in future studies. If they are replicated, they have clinical implications for patient assessments. In addition, future studies could test the efficacy of psychoeducational interventions, designed to enhance social support and coping strategies.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Increased levels of anxiety, during the diagnosis of and surgery for breast cancer, are part of an anticipated reaction to acute stress. Based on our findings, women with higher levels of depressive symptoms, feelings of uncertainty, difficulties coping as a result of disease or treatment, a lower sense of control, and decreased satisfaction with life (i.e., intercept predictors) are at risk for higher levels of anxiety before surgery. Clinicians could implement systematic assessments of anxiety, as well as the characteristics identified in this study to identify high risk women who warrant more targeted interventions. In addition, ongoing follow-up is needed in order to prevent adverse postoperative outcomes and to support women to return to their preoperative levels of function. Future studies could evaluate the efficacy of interventions aimed at modifiable risk factors.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA107091 and CA118658). Dr. Christine Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor. This project is supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Barez M, Blasco T, Fernandez-Castro J, Viladrich C. Perceived control and psychological distress in women with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. J Behav Med. 2009;32(2):187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330(7493):702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean C. Psychiatric morbidity following mastectomy: preoperative predictors and types of illness. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(3):385–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallowfield LJ, Hall A, Maguire GP, et al. Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. BMJ. 1990;301(6752):575–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6752.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher J, Parle M, Cairns D. Appraisal and psychological distress six months after diagnosis of breast cancer. Experimental evidence for interpretive but not attention biases towards somatic information in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7(Part 3):365–376. doi: 10.1348/135910702760213733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg JA, Scott RN, Davidson PM, et al. Psychological morbidity in the first year after breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18(4):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, et al. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):160–168. doi: 10.1037/a0017806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Psychological distress after initial treatment for breast cancer: a comparison of partial and total mastectomy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(8):765–771. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millar K, Purushotham AD, McLatchie E, et al. A 1-year prospective study of individual variation in distress, and illness perceptions, after treatment for breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(4):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker PA, Youssef A, Walker S, et al. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(11):3078–3089. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez AJ, Richards MA, Jarrett SR, et al. Can mood disorder in women with breast cancer be identified preoperatively? Br J Cancer. 1995;72(6):1509–1512. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vahdaninia M, Omidvari S, Montazeri A. What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow-up study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(3):355–361. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, et al. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18(4):315–326. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartl K, Engel J, Herschbach P, et al. Personality traits and psychosocial stress: quality of life over 2 years following breast cancer diagnosis and psychological impact factors. Psychooncology. 2010;19(2):160–169. doi: 10.1002/pon.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Psychological distress after initial treatment of breast cancer. Assessment of potential risk factors. Cancer. 1992;70(1):120–125. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<120::aid-cncr2820700120>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Ikin J, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 1998;169(4):192–196. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henselmans I, Fleer J, de Vries J, et al. The adaptive effect of personal control when facing breast cancer: cognitive and behavioural mediators. Psychol Health. 2010;25(9):1023–1040. doi: 10.1080/08870440902935921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughson AV, Cooper AF, McArdle CS, et al. Psychological impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in the first two years after mastectomy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293(6557):1268–1271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6557.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinnen C, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R, et al. Course of distress in breast cancer patients, their partners, and matched control couples. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(2):141–148. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, et al. Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2608–2613. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barez M, Blasco T, Fernandez-Castro J, Viladrich C. A structural model of the relationships between perceived control and adaptation to illness in women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(1):21–43. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nosarti C, Roberts JV, Crayford T, et al. Early psychological adjustment in breast cancer patients: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(6):1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhruva A, Dodd M, Paul SM, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in patients with breast cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(3):201–212. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c75f2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merriman JD, Jansen C, Koetters T, et al. Predictors of the trajectories of self-reported attentional fatigue in women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(4):423–432. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.423-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miaskowski C, Cooper B, Paul SM, et al. Identification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent breast pain following breast cancer surgery. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Onselen C, Paul SM, Lee K, et al. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in women before and after surgery for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(2):244–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCann B, Miaskowski C, Koetters T, et al. Associations between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and breast pain in women prior to breast cancer surgery. J Pain. 2012;13(5):425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(5):668–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson P, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Dodd MJ, et al. A model for symptom management. Image. 1994;26(4):272–276. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humphreys J, Lee KA, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. Theory of Symptom Management. In: Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Middle Range Theory for Nursing. 2. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2008. pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langford DJ, Paul SM, Tripathy D, et al. Trajectories of pain and analgesics in oncology outpatients with metastatic bone pain during participation in a psychoeducational intervention study to improve pain management. J Pain. 2011;12(6):652–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langford DJ, Tripathy D, Paul SM, et al. Trajectories of pain and analgesics in oncology outpatients with metastatic bone pain. J Pain. 12(4):495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindviksmoen G, Hofso K, Paul SM, et al. Predictors of initial levels and trajectories of depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31826fc9cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, et al. Predictors of the trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance in men with prostate cancer during and following radiation therapy. Sleep. 2011;34(2):171–179. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Onselen C, Paul SM, Lee K, et al. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in women before and after surgery for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(2):244–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karnofsky D. Performance scale. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner F, Bachmann LM, Weber U, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome 1--the Swiss cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustun BT, Stucki G. Identification of candidate categories of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) for a Generic ICF Core Set based on regression modelling. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Kennedy AG. Limitations of diabetes pharmacotherapy: results from the Vermont Diabetes Information System study. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait version: structure and content re-examined. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(7–8):777–788. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2001;72(3):263–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1010305200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, et al. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19(5):481–494. doi: 10.1080/016128498248917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The measurement structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;64(3):507–521. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991;36(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gay CL, Lee KA, Lee SY. Sleep patterns and fatigue in new mothers and fathers. Biol Res Nurs. 2004;5(4):311–318. doi: 10.1177/1099800403262142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee KA, Portillo CJ, Miramontes H. The fatigue experience for women with human immunodeficiency virus. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(2):193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miaskowski C, Lee KA. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in oncology outpatients receiving radiation therapy for bone metastasis: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(5):320–332. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in men with prostate cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Paul SM, et al. Subgroups of patients with cancer with different symptom experiences and quality-of-life outcomes: a cluster analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(5):E79–89. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.E79-E89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cimprich B, Visovatti M, Ronis DL. The Attentional Function Index--a self-report cognitive measure. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):194–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cimprich B. Attentional fatigue following breast cancer surgery. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(3):199–207. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cimprich B, So H, Ronis DL, et al. Pre-treatment factors related to cognitive functioning in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14(1):70–78. doi: 10.1002/pon.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jansen CE, Dodd MJ, Miaskowski CA, et al. Preliminary results of a longitudinal study of changes in cognitive function in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Psychooncology. 2008;17(12):1189–1195. doi: 10.1002/pon.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fletcher BS, Paul SM, Dodd MJ, et al. Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):599–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee KA. Self-reported sleep disturbances in employed women. Sleep. 1992;15(6):493–498. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee KA, DeJoseph JF. Sleep disturbances, vitality, and fatigue among a select group of employed childbearing women. Birth. 1992;19(4):208–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1992.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63(11 Suppl):2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Padilla GV, Grant MM. Quality of life as a cancer nursing outcome variable. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985;8(1):45–60. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, et al. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1983;6(3):117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raudenbush SW. Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:501–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alves ML, Pimentel AJ, Guaratini AA, et al. Preoperative anxiety in surgeries of the breast: a comparative study between patients with suspected breast cancer and that undergoing cosmetic surgery. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2007;57(2):147–156. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942007000200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hughes J. Emotional reactions to the diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 1982;26(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(82)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morris J, Royle GT. Choice of surgery for early breast cancer: pre- and postoperative levels of clinical anxiety and depression in patients and their husbands. Br J Surg. 1987;74(11):1017–1019. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800741120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris T, Greer HS, White P. Psychological and social adjustment to mastectomy: a two-year follow-up study. Cancer. 1977;40(5):2381–2387. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2381::aid-cncr2820400555>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dean C, Surtees PG. Do psychological factors predict survival in breast cancer? J Psychosom Res. 1989;33(5):561–569. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Middeldorp CM, Cath DC, Van Dyck R, et al. The co-morbidity of anxiety and depression in the perspective of genetic epidemiology. A review of twin and family studies. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):611–624. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400412x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kopp M, Bonatti H, Haller C, et al. Life satisfaction and active coping style are important predictors of recovery from surgery. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(4):371–377. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carver CS, Smith RG, Antoni MH, et al. Optimistic personality and psychosocial well-being during treatment predict psychosocial well-being among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2005;24(5):508–516. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong CA, Bramwell L. Uncertainty and anxiety after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1992;15(5):363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sammarco A. Quality of life of breast cancer survivors: a comparative study of age cohorts. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(5):347–356. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e23b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mishel MH. The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1981;30(5):258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ranchor AV, Sanderman R, Steptoe A, et al. Pre-morbid predictors of psychological adjustment to cancer. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(2):101–113. doi: 10.1023/a:1015053623843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gall TL, Kristjansson E, Charbonneau C, et al. A longitudinal study on the role of spirituality in response to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2009;32(2):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landmark BT, Bohler A, Loberg K, et al. Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and their perceptions of needs in a health-care context. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7B):192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heim E, Valach L, Schaffner L. Coping and psychosocial adaptation: longitudinal effects over time and stages in breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(4):408–418. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP, Tran K, et al. Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(2):191–201. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-0887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med. 1996;24(3):218–224. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]