Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of birth defects, and its etiology is not completely understood. Atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the most common defects of CHD. Previous studies have demonstrated that mutations in the transcription factor T-box 20 (TBX20) contribute to congenital ASD. Whole-exome sequencing in combination with a CHD-related gene filter was used to detect a family of three generations with ASD. A novel TBX20 mutation, c.526G>A (p.D176N), was identified and co-segregated in all affected members in this family. This mutation was predicted to be deleterious by bioinformatics programs (SIFT, Polyphen2, and MutationTaster). This mutation was also not presented in the current Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP) or National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). In conclusion, our finding expands the spectrum of TBX20 mutations and provides additional support that TBX20 plays important roles in cardiac development. Our study also provided a new and cost-effective analysis strategy for the genetic study in small CHD pedigree.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease (CHD), Atrial septal defect (ASD), Whole-exome sequencing, CHD-related gene filter, TBX20

1. Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect and the leading non-infectious cause of death in the newborn, affecting 19–75 per 1000 live births. Since CHD could cause prenatal lethality, the actual incidence may be much higher (Pierpont et al., 2007; Bruneau, 2008; Richards and Garg, 2010). Atrial septal defect (ASD; OMIM 612794) is one of the most common forms of CHD and occurs in both isolation and other complex cardiac malformations.

Genetically, CHD is a very heterogeneous disease. To date, the amount of genes related to CHD including ASD has been identified (Andersen et al., 2013): (1) transcription factors and co-factors, e.g., GATA4 (OMIM 600576), NKX2-5 (OMIM 600584), TBX5 (OMIM 601620), and TBX20 (OMIM 606061); (2) ligands-receptors, e.g., CRELD1 (OMIM 607170); (3) structure protein of sarcomere, e.g., MYH6 (OMIM 160710), MYH7 (OMIM 160760), and ACTC1 (OMIM 102540) (Posch et al., 2010b; Wessels and Willems, 2010; Ware and Jefferies, 2012; Andersen et al., 2013; Fahed et al., 2013).

T-box 20 (TBX20) is a member of the T-box family that encodes the transcription factor TBX20. TBX20 carries strong transcriptional activation and repression domains, and physically or genetically interacts with several cardiac development transcription factors, including NKX2-5, GATA4, GATA5, and TBX5 regulating various aspects of embryonic heart development. In the developing mouse embryos, tbx20 is expressed in cardiac progenitor cells, as well as in the developing myocardium and endothelial cells associated with endocardial cushions, the precursor structures for the cardiac valves and the atrioventricular septum, which implies that tbx20 is essential for proper heart development. Loss function of tbx20 in the mouse has been found in connection with various forms of congenital heart defects, including defects in septation, valvulogenesis, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmia (Stennard et al., 2003; Stennard et al., 2005; Kirk et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008; Posch et al., 2010a; Sotoodehnia et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Qiao et al., 2012).

In our study, by using whole-exome sequencing in combination with a CHD-related gene filter, all non-coding and synonymous variants, as well as variants present in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP), 1000 Genomes, HapMap, YH, and Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) databases and variants which are not in 455 CHD-related genes (Data S1) were excluded initially. According to prediction by three bioinformatics programs (SIFT, Polyphen2, and MutationTaster) and co-segregation analysis, we identified a novel mutation (c.526G>A/p.D176N) in exon3 of TBX20 in all affected members in three generations of a family with ASD. To the best of our knowledge, this mutation has not been reported in previous studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

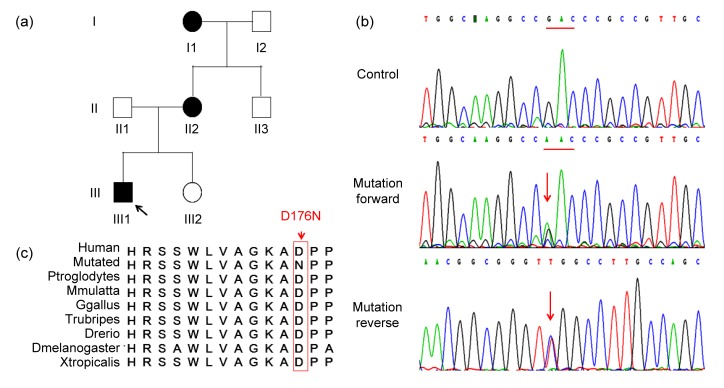

A family from Hunan Province in central-south China with seven members across three generations participated in this study. Three patients were diagnosed as having ASD (I1, II2, and III1) (Table 1; Fig. 1a). All patients were diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiograms in the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery of the Second Xiangya Hospital, China. All family members were provided informed consent for collection, storage, and use of DNA for the purpose of research. A proband (III1 in Fig. 1a) consented specifically for whole-exome sequencing. This study protocol was approved by the Review Board of the Second Xiangya Hospital of the Central South University, China.

Table 1.

Summary of the family with atrial septal defect (ASD)

| Family | Age | CHD | Echocardiography |

TBX20 |

||||

| ASD size (mm) | RA (mm) | RV (mm) | LVEF (%) | DNA | Protein | |||

| III1 (proband) | 7 months | ASD | 15 | 29 | 26 | 69 | 526G>A | D176N |

| I1 | 59 years | ASD | 2 | 35 | 34 | 60 | 526G>A | D176N |

| I2 | 61 years | No | 33 | 30 | 62 | |||

| II1 | 31 years | No | 32 | 30 | 65 | |||

| II2 | 28 years | ASD | 12 | 43 | 41 | 63 | 526G>A | D176N |

| II3 | 25 years | No | 32 | 31 | 69 | |||

| III2 | 3 years | No | 24 | 22 | 72 | |||

CHD: congenital heart disease; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

Fig. 1.

Sequencing and analysis of TBX20 mutation (p.D176N) in the family with ASD

(a) Pedigree of the family affected with ASD. Family members are identified by generations and numbers. Squares: male members; circles: female members; black symbols: affected members; white symbols: unaffected members; arrow: proband. (b) Sequencing results of the TBX20 mutation. Sequence chromatogram indicates a G to A transition of nucleotide 526. (c) Alignment of multiple TBX20 protein sequences across species. The D176 affected amino acid locates in the highly conserved amino acid region in different mammals

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. DNA extraction

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes of the participants. gDNA was prepared using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) on the QIAcube automated DNA extraction robot (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as previously described (Tan et al., 2012).

2.2.2. Targeted capture and massive parallel sequencing

Exome capture and high-throughput sequencing (HTS) were performed in the State Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics of China in collaboration with Beijing Genomic Institute (BGI Shenzhen, China) (Wang et al., 2010). gDNA (5 μg) from the proband (III1) in this family was captured with the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ library exome capture reagent (Roche Inc., Madison, USA) and sequenced (Illumina HiSeq2000, 90 base paired-end reads; Illomina Inc., USA). Briefly, gDNA was randomly fragmented by a Covaris S2 instrument (Covaris Inc., USA). Then, the 250–300 bp fragments of DNA were subjected to three enzymatic steps: end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Once the DNA libraries were indexed, they were amplified by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Extracted DNA was purified and hybridized to the NimbleGen Seqcap EZ Library. Each captured library was then loaded onto the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Illumina base calling software V1.7 was employed to analyze the raw image files with default parameters.

2.2.3. Read, mapping and variant detection

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed as previously described (Gao et al., 2013): (1) reads were aligned to the NCBI human reference genome (gh19/NCBI 37.1) with SOAPaligner method V2.21; (2) for paired-end reads with duplicated start and end sites, only one copy with the highest quality was retained and the reads with adapters were removed; (3) SOAPsnp V1.05 was used to assemble the consensus sequence and call genotypes; (4) small insertions and deletions (INDELs) detection was used with the Unified Genotyper tool from GATK V1.0.4705.

2.2.4. Filtering and annotation

Five major steps were taken to prioritize all the high-quality variants among CHD-related genes (Gao et al., 2013): (1) variants within intergenic, intronic, and untranslated regions (UTRs) and synonymous mutations were excluded from later analysis; (2) variants in dbSNP132 (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), the 1000 Genomes project (1000G, http://www.1000genomes.org), and HapMap project (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/hapmap) were excluded; (3) variants in YH database (http://yh.Genomics.org.cn/) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) ESP database (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) were further excluded; (4) variants not in 455 CHD-related genes (Data S1) were excluded (Wilde and Behr, 2013; Zaidi et al., 2013); (5) SIFT (http://sift.bii.astar.edu.sg/), Polyphen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), and MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org) were used to predict the possible impact of variants.

2.2.5. Mutation validation and co-segregation analysis

Sanger sequencing was used to validate the candidate variants found in the whole-exome sequencing. Segregation analysis was performed in all family members. Primer pairs used to amplify fragments encompassing individual variants were designed by an online tool PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.; http://www.idtdna.com/Primerquest/Home/Index) and the sequences of PCR primers will be provided upon request.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics and phenotype information

A Chinese family with isolated secundum ASD was first identified after the proband (III1) was referred for evaluation of a murmur at 7 months old. The echocardiography described a dilated right atrium, dilated right ventricle, and a secundum ASD measuring 15 mm in dimension. Meanwhile, the family history revealed that there were an additional two related living individuals diagnosed as having ASD. Both the proband (III1) and II2 underwent successful surgical repairs. I1 without any treatment was diagnosed with secundum ASD by echocardiography (Fig. 1a; Table 1). No other malformations were observed in the three affected members, which indicated that this family CHD is an isolated or non-syndromic CHD with an autosomal dominant pattern.

3.2. Exome sequencing and co-segregation analysis

To detect the causative genetic alteration in this family, whole-exome sequencing in combination with a CHD-related gene filter was performed on the proband (III1). The result demonstrated a set of 19 single nucleotide variants in 16 CHD candidate genes after filtering (Table 2). Co-segregation analysis of six causative variants (OBSCN, USF1, TBX20, LDB3, MYH6, and IFT20) (Table 2), which were predicted by three programs (SIFT, MutationTaster, and Polyphen2) showed that only TBX20 gene mutation segregated in all affected family members (Figs. 1a and 1b; Table 1). Unaffected family members who were assessed did not carry the mutation. The missense mutation (c.526G>A) results in a substitution of aspartic acid by asparagine in the TBX20 protein (p.D176N). This newly identified c.526G>A mutation was not found in our 200 control cohorts (Tan et al., 2012). This mutation was also not presented in the current dbSNP and NHLBI ESP.

Table 2.

Variants identified by whole-exome sequencing in combination with CHD candidate gene filter

| Gene | Chr | Base position | RB | AB | Mutation | Amino acid alteration | Sorting intolerant from tolerant | Polyphen2 | MutationTaster |

| NOTCH2NL | chr1 | 145273345 | T | C | Missense | S>P | rs10910779 | ||

| NOTCH2 | chr1 | 120539661 | C | T | Missense | R>Q | rs146498360 | ||

| OBSCN | chr1 | 228562288 | G | A | Missense | G>R | Damaging (0.004) | PD (0.997) | DC (125) |

| USF1 | chr1 | 161011931 | T | G | Missense | Y>C | Tolerated (0.199) | PD (0.560) | DC (194) |

| ZNF638 | chr2 | 71576412 | A | G | Missense | I>V | rs12612365 | ||

| ZNF638 | chr2 | 71650308 | G | A | Missense | A>T | Damaging (0.024) | Benign (0.094) | Polymorphism (58) |

| VEGFC | chr4 | 177605086 | C | T | Missense | M>I | Tolerated (0.103) | Benign (0.000) | Polymorphism (10) |

| DST | chr6 | 56472194 | C | T | Missense | C>Y | rs185733722 | ||

| TBX20 | chr7 | 35288308 | C | T | Missense | D>N | Damaging (0.004) | PD (0.985) | DC (23) |

| LRRC6 | chr8 | 133634908 | G | T | Missense | P>H | rs76147813 | ||

| LDB3 | chr10 | 88469751 | C | T | Missense | A>V | Tolerated (0.291) | PD (0.745) | DC (64) |

| PTPN11 | chr12 | 112892433 | T | G | Nonsense | Y>* | rs76982592 | ||

| PTPN11 | chr12 | 112892407 | T | G | Missense | S>A | rs79068130 | ||

| MYH6 | chr14 | 23855762 | A | T | Missense | I>N | Damaging (0.000) | Benign (0.248) | DC (194) |

| MYH6 | chr14 | 23871682 | C | T | Missense | G>S | rs148962966 | ||

| IFT20 | chr17 | 26658963 | T | G | Missense | N>H | Damaging (0.015) | DC (68) | |

| DSC2 | chr18 | 28651796 | G | T | Missense | R>S | Tolerated (0.382) | Benign (0.095) | Polymorphism (110) |

| DOT1L | chr19 | 2211146 | T | C | Missense | V>A | Damaging (0.014) | Benign (0.001) | Polymorphism (64) |

| EP300 | chr22 | 41527628 | A | G | Missense | S>G | rs146242251 |

Chr: chromosome; RB: reference sequence base; AB: alternative base identified; PD: probably damaging; DC: disease causing. Variants were share by two family members (III1 and II1) after filtering. Each row represents a single variant. The five rows beginning with OBSCN, USF1, LDB3, MYH6 (first), and IFT20 represent the five variants that were validated independently and screened for in affected family members. Only TBX20 was segregated with disease in this family

3.3. Variant analysis

The aspartic acid residue at position 176 in TBX20 protein is highly evolutionarily conserved in diverse species including chimp, monkey, chicken, pufferfish, zebrafish, melanogaster, and frog (Fig. 1c). Three programs for analyzing protein functions, Polyphen2, SIFT, and MutationTaster, predicted that the p.D176N variants are probably damaging (0.985), damaging (0.004), and disease causing (23), respectively.

4. Discussion

Due to the complexity of CHD attributed by both genetic and nongenetic effectors, the etiology of CHD is still not completely understood. To date, approximately 500 genes have been revealed to be related to cardiac development defects in mice when mutated, and 55 human genes have been identified associated with CHDs (Andersen et al., 2013; Fahed et al., 2013; Wilde and Behr, 2013; Zaidi et al., 2013). Complex or rare Mendelian disorders in small CHDs pedigree make the discovery of novel genes difficult or impossible using the traditional approach (Rabbani et al., 2012).

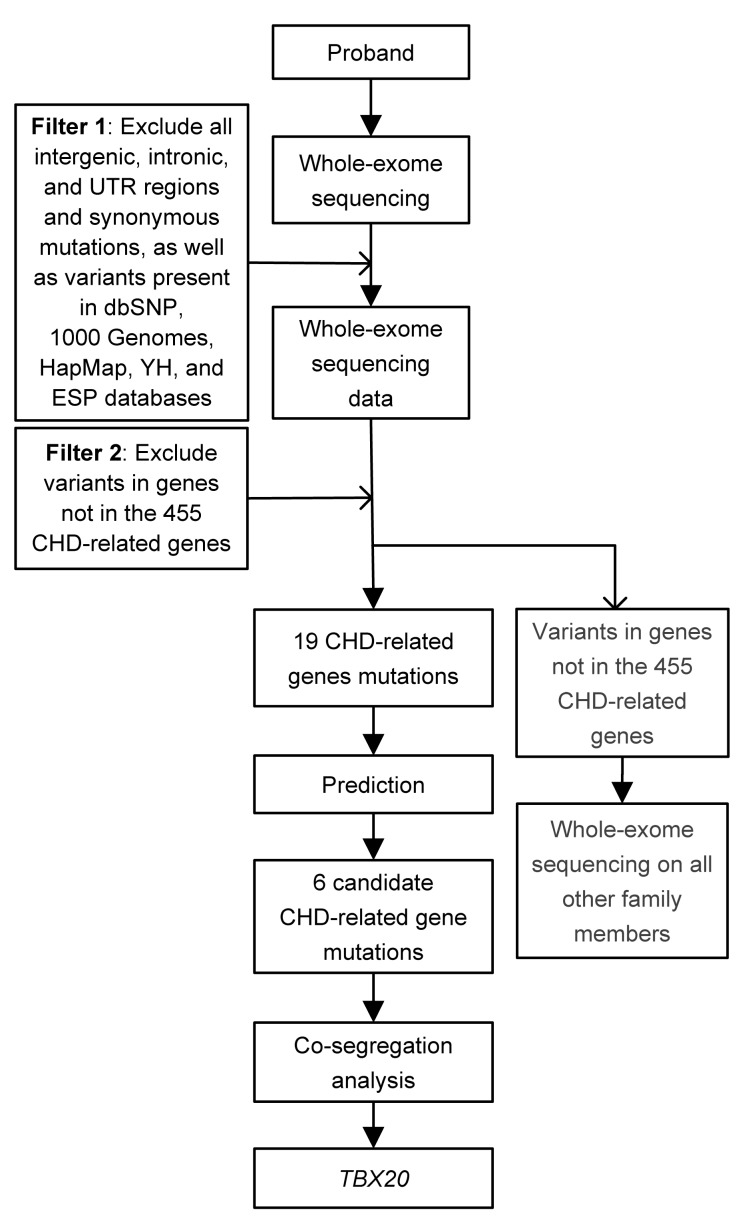

However, next-generation sequencing technologies such as the whole-exome sequencing approach are improving as rapid, high-throughput, and cost-effective approaches to fulfill medical sciences and research demands (Ng et al., 2009; Metzker, 2010; Ku et al., 2011). In our study, the pedigree is really small and it is difficult to discover a new causative gene. Therefore, we initially hypothesized that the causative gene is in the list of related genes for CHD (Data S1) after analysis of whole-exome sequencing data. According to prediction by three bioinformatics programs (SIFT, Polyphen 2, and MutationTaster), six candidate causative genes were highly suspicious (OBSCN, USF1, TBX20, LDB3, MYH6, and IFT20; Table 2). Co-segregation analysis demonstrated that only TBX20 gene mutation (c.526G>A/p.D176N) was segregated in all affected family members. If the variant is not in the 455 CHD-related genes, much more work needs to be done, such as whole-exome sequencing on all other family members. If so, it is inevitable that the cost and workload will increase. Therefore, our research provided a new and cost-effective strategy for genetic study in small CHD pedigree (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis strategy for a novel causative mutation in small CHD pedigree

TBX20 plays a critical role in embryonic development and organogenesis, including cell type specification, tissue patterning, and morphogenesis (Smith, 1999; Packham and Brook, 2003; Showell et al., 2004). Inherited TBX20 mutations (I152M, Q195*) in patients with ASD were first identified using the first generation sequencing technology (Kirk et al., 2007). The author reported missense (I152M) and nonsense (Q195*) mutations in two families with isolated ASD or/and other cardiac structure anomaly. Subsequently, other studies identified other TBX20 mutations via the first generation sequencing technology. Liu et al. (2008) found a number of variants among Chinese patients with ASD with or without other congenital heart defects, including tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC). Qian et al. (2009) reported that two different variants of TBX20 were found in four children with ASD with or without other CHD. Posch et al. (2010a) identified a TBX20 missense variant in a patient with ASD with additional TOF and cardiac valve defect (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of identified ASD-related TBX20 gene mutations

| Reference | Nucleotide change | AA change | Cardiac defect |

| Kirk et al. (2007) | 456C>G | I152M | ASD,VSD, PFO |

| 583C>T | Q195* | ASD, CoA, MVP, MR, DCM | |

| Liu et al. (2008) | 187G>A | A63T | ASD |

| 361A>T | I121F | TAPVC, ASD | |

| Qian et al. (2009) | 597C>G | H186D | ASD, MR, TOF, cleft mitral valve |

| 601T>C | L197P | ASD, TOF | |

| Posch et al. (2010) | 374C>G | I121M | ASD, TOF, cardiac valve defect |

AA: amino acid; ASD: atrial septal defect; CoA: coarctation of aorta; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; MR: mitral regurgitation; MVP: mitral valve prolapse; PFO: patent oval foramen; TAPVC: total anomalous pulmonary venous connection; TOF: tetralogy of Fallot; VSD: ventricular septal defect

In this study, the whole-exome sequencing in combination with a CHD-related gene filter was performed to investigate a family with ASD. A novel mutation c.526G>A in TBX20 causing a missense change (p.D176N) that affected a highly conserved residue in an evolutionarily conserved protein was identified. The p.D176N was not found in the public databases and our 200 control cohorts. Meanwhile, Polyphen2, SIFT, and MutationTaster predicted that p.D176N will be deleterious in its effect. Co-segregated analysis showed that p.D176N segregates with disease in this family. These findings demonstrated that this variant should not be excluded from further study.

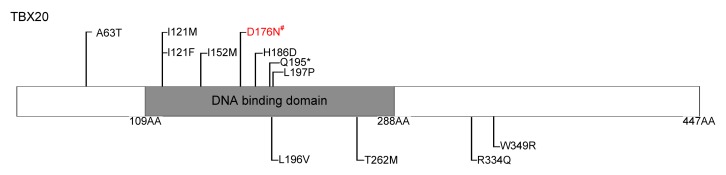

This identified missense change (p.D176N) is in the T-box DNA binding domain of TBX20 (109–288 AA). TBX20 associated directly with other cardiac transcription factors, namely, the homeodomain factor NKX2-5 and zinc finger factor GATA4 and GATA5 (Stennard et al., 2003). Modification of amino acid from aspartic acid to asparagine may not prevent binding to its target DNA site, but there are other possibilities, such as an influenced rate of scanning of DNA or co-factors for interaction, or abnormal structure stability when bound to co-factors (Posch et al., 2010a). Previous studies have demonstrated that identified ASD-related TBX20 mutations are all in the T-box DNA binding domain (109–288 AA) except p.A63T (Fig. 3; Table 3) (Kirk et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2009; Posch et al., 2010a). Therefore, although in vitro assays were not performed in our study, we still believed that the mutation (p.D176N) in this study plays a critical role in CHDs. In our further analysis, the functional test will be performed.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of TBX20 protein structure with exonic germline mutations related to non-syndromic CHD indicated

All mutations related to ASD are represented on the top. Mutations found in patients with CHD other than ASD are shown below the structural domain. # indicate the novel mutation in our study

In summary, we reported a novel TBX20 mutation (p.D176N) in a three-generation family with three ASD patients. The present identification of a novel mutation not only further supports the important role of cardiac transcription factor TBX20 in congenital ASD, but also expands the spectrum of TBX20 mutations and will contribute to the genetic diagnosis and counseling of families with CHD. Meanwhile, our study provided a new and cost-effective analysis strategy for the genetic study in small CHD pedigree.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and their families for participating in this study. We are grateful to Mrs. Jian WANG for her assistance in collecting blood samples from the Center of Clinical Gene Diagnosis and Therapy, the State Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics, the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China.

List of electronic supplementary materials

Four hundred and fifty-five candidate genes for congenital heart disease (CHD)

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81370204, 81300072, and 81101475)

Electronic supplementary materials: The online version of this article (http://dx.doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1400062) contains supplementary materials, which are available to authorized users

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Ji-jia LIU, Liang-liang FAN, Jin-lan CHEN, Zhi-ping TAN, and Yi-feng YANG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients for which identifying information is included in this article.

References

- 1.Andersen TA, Troelsen KD, Larsen LA. Of mice and men: molecular genetics of congenital heart disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;71(8):1327–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1430-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451(7181):943–948. doi: 10.1038/nature06801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahed AC, Gelb BD, Seidman JG, et al. Genetics of congenital heart disease: the glass half empty. Circ Res. 2013;112(4):707–720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao X, Su Y, Guan LP, et al. Novel compound heterozygous TMC1 mutations associated with autosomal recessive hearing loss in a Chinese family. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk EP, Sunde M, Costa MW, et al. Mutations in cardiac T-box factor gene TBX20 are associated with diverse cardiac pathologies, including defects of septation and valvulogenesis and cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):280–291. doi: 10.1086/519530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ku CS, Naidoo N, Pawitan Y. Revisiting mendelian disorders through exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2011;129(4):351–370. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C, Shen A, Li X, et al. T-box transcription factor TBX20 mutations in Chinese patients with congenital heart disease. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51(6):580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD, et al. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461(7261):272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Packham EA, Brook JD. T-box genes in human disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(S1):R37–R44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierpont ME, Basson CT, Benson DW, et al. Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115(23):3015–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posch MG, Gramlich M, Sunde M, et al. A gain-of-function TBX20 mutation causes congenital atrial septal defects, patent foramen ovale and cardiac valve defects. J Med Genet. 2010;47(4):230–235. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posch MG, Perrot A, Berger F, et al. Molecular genetics of congenital atrial septal defects. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99(3):137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian L, Mohapatra B, Akasaka T, et al. Transcription factor neuromancer/TBX20 is required for cardiac function in Drosophila with implications for human heart disease. PNAS. 2009;105(50):19833–19838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808705105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiao YL, Wanyan HX, Xing QN, et al. Genetic analysis of the TBX20 gene promoter region in patients with ventricular septal defects. Gene. 2012;500(1):28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabbani B, Mahdieh N, Hosomichi K, et al. Next-generation sequencing: impact of exome sequencing in characterizing mendelian disorders. J Hum Genet. 2012;57(10):621–632. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards AA, Garg V. Genetics of congenital heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6(2):91–97. doi: 10.2174/157340310791162703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen T, Aneas I, Sakabe N, et al. TBX20 regulates a genetic program essential to adult mouse cardiomyocyte function. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(12):4640–4654. doi: 10.1172/JCI59472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Showell C, Binder O, Conlon FL. T-box genes in early embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229(1):201–218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith J. T-box genes—what they do and how they do it. Trends Genet. 1999;15(4):154–158. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sotoodehnia N, Isaacs A, de Bakker PI, et al. Common variants in 22 loci are associated with QRS duration and cardiac ventricular conduction. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1068–1076. doi: 10.1038/ng.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stennard FA, Costa MW, Elliott DA, et al. Cardiac T-box factor TBX20 directly interacts with Nkx2-5, GATA4, and GATA5 in regulation of gene expression in the developing heart. Dev Biol. 2003;262(2):206–224. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stennard FA, Costa MW, Lai D, et al. Murine T-box transcription factor TBX20 acts as a repressor during heart development, and is essential for adult heart integrity, function and adaptation. Development. 2005;132(10):2451–2462. doi: 10.1242/dev.01799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan ZP, Huang C, Xu ZB, et al. Novel ZFPM2/FOG2 variants in patients with double outlet right ventricle. Clin Genet. 2012;82(5):466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JL, Yang X, Xia K, et al. TGM6 identified as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using exome sequencing. Brain. 2010;133(12):3510–3518. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware SM, Jefferies JL. New genetic insights into congenital heart disease. J Clin Exp Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.4172/2155-9880.S8-003. S8:003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wessels MW, Willems PJ. Genetic factors in non-syndromic congenital heart malformations. Clin Genet. 2010;78(2):103–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilde AAM, Behr ER. Genetic testing for inherited cardiac disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(10):571–583. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidi S, Choi M, Wakimoto H, et al. De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature. 2013;498(7453):220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang WJ, Chen HY, Wang Y, et al. Tbx20 transcription factor is a downstream mediator for bone morphogenetic protein-10 in regulating cardiac ventricular wall development and function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(42):36820–36829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Four hundred and fifty-five candidate genes for congenital heart disease (CHD)