Abstract

Background

Anastomotic leak is one of the most serious complications following bariatric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), and associated with high morbidity rates and prolonged hospital stay. Timely management is of utmost importance for the clinical outcome. This study evaluated the approach to suspected leakage in a high-volume bariatric surgery unit.

Methods

All consecutive patients who underwent LRYGB performed by the same team of surgeons were registered prospectively in a clinical database from September 2005 to June 2012. Suspected leaks were identified based on either clinical suspicion and/or associated laboratory values, or by a complication severity grade of at least II using the Clavien–Dindo score.

Results

A total of 6030 patients underwent LRYGB during the study period. The leakage rate was 1·1 per cent (64 patients). Forty-five leaks (70 per cent) were treated surgically and 19 (30 per cent) conservatively. Eight (13 per cent) of 64 patients needed intensive care and the mortality rate was 3 per cent (2 of 64). Early leaks (developing in 5 days or fewer after LRYGB) were treated by suture of the defect in 20 of 22 patients and/or operative drainage in 13. Late leaks (after 5 days) were managed with operative drainage in 19 of 23 patients and insertion of a gastrostomy tube in 15. Patients who underwent surgical treatment early after the symptoms of leakage developed had a shorter hospital stay than those who had symptoms for more than 24 h before reoperation (12·5 versus 24·4 days respectively; P < 0·001).

Conclusion

Clinical suspicion of an anastomotic leak should prompt an aggressive surgical approach without undue delay. Early operative treatment was associated with shorter hospital stay. Delays in treatment, including patient delay, after symptom development were associated with adverse outcomes.

Introduction

Anastomotic leaks and pulmonary embolism are the two most feared complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), and considered the most common cause of death1,2. The reported incidence of leakage varies from 0·1 to 5·6 per cent3–7, partly depending on the definition used. The Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry8 reported a leak rate of 1·4 per cent in 19 789 women and 2·1 per cent among 6331 men. However, there is no uniform consensus on the classification or treatment of leaks, with classification according to time after operation, location or cause being proposed9,10. Treatment of leaks differs between centres, ranging from mainly conservative management11,12, to use of endoluminal stents and fibrin glue11,13–15, to early reoperation10,16,17. Such differences probably reflect both varying definitions of leakage, and differences in vigilance in diagnosing leaks. Staple-line reinforcement has been proposed to reduce the rate of leakage, but the evidence is poor18–20.

Leaks are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates21, and delay in diagnosis and treatment may have serious consequences. The aims of the present study were to investigate the causes and risk factors for leakage, and to evaluate different treatment strategies in a high-volume bariatric surgery setting.

Methods

Aleris Hospital in Oslo, Norway, and Aleris Obesity Skåne in Kristianstad, Sweden, are two surgical private practice units specializing in bariatric surgery. Both units use the same treatment protocol and a joint database, and all operations are performed in a standardized manner using the same rotating team of surgeons. All consecutive LRYGBs performed in the two hospitals between September 2005 and June 2012 were included in the study. Indications for surgery were in line with the European guidelines on surgery of severe obesity22. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) over 40 kg/m2, or 35–40 kg/m2 with obesity-related co-morbidity, were eligible for surgery. Bariatric surgery was also indicated in patients who had originally had a high BMI, exhibited substantial weight loss in a conservative treatment programme, but then started to gain weight again.

Definition of anastomotic leak and management

The following symptoms were recorded prospectively during the hospital stay: pain, nausea, tachycardia, fever, and haemoglobin level, C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration and white blood cell count, if indicated. Leaks were defined on clinical grounds. Patients who had tachycardia exceeding 120 beats per min, used more pain medication than expected and/or were not mobilized within 2 h after surgery were considered to have a leak or bleeding. In the first 24 h the indication for surgical exploration was based solely on clinical symptoms. All patients received both written and oral information about complications, including leaks, before discharge from hospital. They were instructed to call the ward or the on-call surgeon if they were feeling sick, had pain that did not respond to oral pain medication, were not fully mobilized, were unable to drink at least 1·5 litres of fluid over 24 h, or had a temperature exceeding 38°C.

All patients entered a follow-up programme, with the first visit in the outpatient clinic at 2–3 months. All complications occurring during this interval were recorded in the database.

The unit in Sweden is fully equipped with an intensive care unit (ICU). The unit in Oslo does not have an ICU, so patients requiring intensive care were referred to another hospital.

Complications

The Clavien–Dindo classification23 was used to grade complications. All patients with grade II–V complications were included. Patients were classified as having a clinically relevant leak if there was a suspicion of intra-abdominal infection (clinical symptoms with raised levels of CRP and/or leucocytes) leading to treatment with antibiotics and/or abscess shown on computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound examination. Grade IIIA–V leaks were more apparent clinically. Leaks that occurred within 5 days of surgery were classified as early leaks, and those that appeared after 5 days as late leaks.

Operative procedure

The surgical procedure has been described in detail previously24,25. In brief, a small gastric pouch (15 ml) was created with the bowel in an antecolic and antegastric position. The gastroenteric (GE) anastomosis and the enteroenteric (EE) anastomosis were stapled linearly and the staple holes handsewn. Initially the bowel was approximated to the gastric pouch as an omega loop, subsequently divided by stapling between the two anastomoses. The last step was to test the integrity of the GE anastomosis by inflation with methylene blue-dyed saline via a nasogastric tube. No operation was concluded without having passed this test, which also confirmed that the lumen was patent and capable of accepting at least a 34-Fr (approximately 8 mm) gastric tube. In the early part of the study, from September 2005 to June 2010, LRYGBs were performed without closing the mesenteric defects. Between July 2010 and June 2012, the mesenteric defects were stapled as described previously26.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected prospectively in a proprietary database. All continuous data are presented as median (range) unless otherwise stated, with statistical analysis by means of the Mann–Whitney U test. The χ2 test was used for comparison of categorical data. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. SPSS® version 21 for Mac OS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for statistical calculations.

Results

LRYGB was performed successfully in all 6030 patients (4698 women, 77·9 per cent). The patients had a median age of 42 (17–73) years and median BMI of 42·9 (28·7–81·0) kg/m2. The procedure was primary in 5874 patients (97·4 per cent) and revisional in 156 (2·6 per cent). A total of 2472 LRYGBs were done without closing the mesenteric defects during the early part of the study, and 3558 with stapling of mesenteric defects in the later part.

Sixty-four patients were considered to have significant leaks according to the Clavien–Dindo classification, 45 women and 19 men, giving a leak rate of 1·1 per cent. Demographics of patients with and without leaks are shown in Table 1. Leaks were not related to age, sex, weight or BMI. Median hospital stay for patients who developed a leak was 13·3 (2–110) days, compared with 1·7 (1–13) days for those without leaks.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Leakage (n = 64) | No leakage (n = 5966) | P‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43 (22–65) | 42 (17–73) | 0.599 |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 45 : 19 | 4653 : 1313 | 0.141§ |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)† | 42·6 (35–59) | 42·9 (28·7–81·0) | 0.909 |

| Weight (kg)† | 125 (93–196) | 123 (75–263) | 0.348 |

| Revisional procedure* | 2 (3) | 154 (2·6) | 0.785§ |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 13·3 (2–110) | 1·7 (1–13) | <0.001 |

Values given are median (range) unless indicated otherwise;

values in parentheses are percentages.

At primary operation.

Mann–Whitney U test, except

χ2 test.

Follow-up rates in the outpatient clinic were 94·8 per cent at 2–3 months and 87·1 per cent at 1 year; altogether only 28 (0·5 per cent) of the 6030 patients were completely lost to follow-up during the first year after surgery.

Management approach to suspected leaks

Some 106 patients (1·8 per cent) had reoperation within 30 days. Forty-five patients (0·7 per cent) were reoperated for leaks, 25 (0·4 per cent) owing to bleeding and 21 (0·3 per cent) for bowel obstruction. There were 15 negative laparoscopies (0·2 per cent). Thus, 15 (14·2 per cent) of 106 reoperations failed to demonstrate any suspected complication. The integrity of the GE anastomosis was tested in all reoperations in the same way as during the primary procedure.

Forty-five patients (70 per cent) had surgery and 19 (30 per cent) received conservative treatment for a confirmed anastomotic leak. Those treated conservatively had milder symptoms, which developed later (10·0 versus 6·5 days after surgery; P = 0·031) than those treated surgically. The most prominent symptoms were tachycardia and abdominal pain. All patients treated conservatively had Clavien–Dindo grade II or IIIA complications, whereas patients who had surgery were graded IIIB or above.

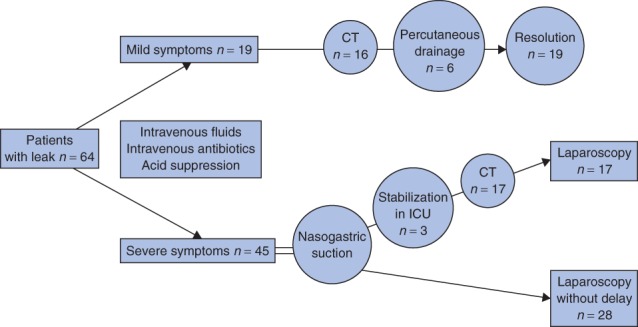

Treatment pathways are shown in Fig. 1. CT demonstrated abscess in 16 of the 19 patients treated conservatively; the diagnosis was made in the other three patients on the basis of abdominal discomfort and a raised CRP level. Six of the 19 patients had percutaneous drainage and 13 were managed by antibiotics alone.

Fig. 1.

Treatment pathways. CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit

Of patients treated surgically, a leak was demonstrated by preoperative CT in 17 patients, whereas the decision to operate was based on clinical symptoms and/or laboratory results in 28 patients (Fig. 1). All active leaks demonstrated on CT (contrast leakage) were managed surgically. Median duration of treatment with antibiotics was 15 (7–40) days in both the conservative and operative intervention groups.

Table 2 summarizes details of leaks treated surgically. Fifty-three (83 per cent) of 64 leaks were diagnosed after discharge from hospital. Those diagnosed after discharge from hospital (mean hospital stay 1·7 days) but before a total of 5 days after operation were classified as early leaks. Approximately half of the leaks were classified as early (22 of 45); the remaining 23 were late leaks, occurring 6–20 days after surgery.

Table 2.

Characteristics of leaks treated surgically

| Early leaks (≤ 5 days) (n = 22) | Late leaks (> 5 days) (n = 23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Interval from primary surgery to reoperation (days)* | 2·8 (0·5–5·0) | 12·0 (6–20) |

| Location of leak | ||

| GE anastomosis | 12 | 15 |

| EE anastomosis | 2 | 3 |

| Both GE and EE anastomoses | 0 | 4 |

| Small intestine | 8 | 1 |

| Cause of leak | ||

| Obstruction | 6 | 10 |

| Necrosis | 8 | 13 |

| Perioperative | 8 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| Suture | 20 | 13 |

| Drainage | 13 | 19 |

| Gastrostomy tube | 5 | 15 |

| Stent | 1 | 2 |

| Duration of antibiotic treatment (days)* | 15 (7–40) | 16 (7–30) |

| No. requiring ICU treatment | 4 | 4 |

| Median length of ICU stay (days) | 12·5 | 23·1 |

| Total length of hospital stay (days)*† | 6·7 (2–21) | 13·4 (4–33) |

| Death | 0 | 2 |

Values are median (range).

Excluding patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). GE, gastroenteric; EE, enteroenteric.

The location of leaks was identified in the 45 patients treated surgically. Leaks were present in both anastomoses (GE and EE ) in four patients. Thirty-one of 49 leaks were located at the GE anastomosis or along the staple line at the gastric pouch, nine at the EE anastomosis, and nine were overlooked inadvertent enterotomies in the small intestine related to operative trauma or injury.

Distal obstruction was considered potentially to have played a role in leakage in 16 of 45 patients; eight had obstruction at the level of the EE anastomosis, five had trocar-port (Richter's) hernias and in three the obstruction was due to intestinal adhesions after earlier surgery. Leaks classified as ‘perioperative’ in eight patients included traumatic perforations of the small intestine and leaks at the suture row (hand-sutured staple hole), which were apparent within 2 days. The cause of the leak was not identified in 22 patients. The leak rate was not affected by closure of the mesenteric defects: it was 1·1 per cent (27 of 2472) in patients without closure compared with 1·0 per cent (37 of 3558) among those in whom the defects were closed (P = 0·848).

Treatment of early leaks

A peritoneal washout was performed in all 22 patients treated by early operation (5 days or fewer after LRYGB). The primary treatment for early leaks was suturing of the defect. This was achieved in 20 of 22 patients. Operative drainage was used in 13 of 22 patients. Five patients with early leaks secondary to obstruction were also treated with a gastrostomy tube (Bard® Tri-Funnel Replacement Gastrostomy Tube, 20-Fr push tube; Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) into the bypassed stomach. One patient with leakage at the distal oesophagus was treated with an endoluminal stent.

Treatment of late leaks

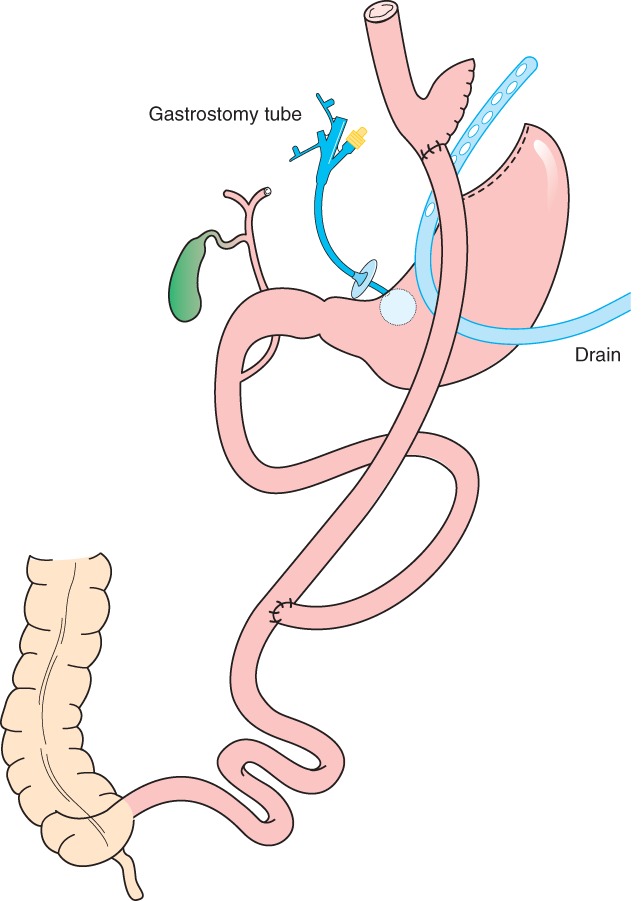

Late leaks (more than 5 days after LRYGB) in 23 patients were most often treated by operative drainage (19) and placement of a gastrostomy tube (15) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Thirteen patients underwent direct suture and/or omentoplasty. Two patients were treated in another hospital with endoscopic placement of an intraluminal stent for leakage at the level of the gastrojejunostomy.

Fig. 2.

Recommended treatment for late leaks (occurring more than 5 days after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) and for early leaks (5 days or fewer) secondary to obstruction: peritoneal irrigation, and insertion of a drain and a gastrostomy tube in the distal part of the bypassed stomach

Management in intensive care

Eight (13 per cent) of 64 patients with leaks were admitted to the ICU. Four of these patients had early leaks and remained in the ICU for a median of 12·5 days. Four patients with late leaks were admitted to the ICU, three of whom were transferred directly to the unit for preoperative stabilization owing to septicaemia.

Two patients died (2 of 64, 3 per cent), both with late leaks. One of these patients was admitted after experiencing clinical symptoms of leakage at home for 2–3 days. This patient developed septicaemia and died from multiple organ failure 7 days after admission to the ICU. The other patient was admitted with symptoms of leakage 1 week after operation and underwent surgery immediately, but aspirated during intubation and died from respiratory failure a few hours after admission to the ICU. The other two patients with late leakage were treated in the ICU for multiple organ failure for 21 and 60 days.

Excluding the eight patients admitted to the ICU, those with early leaks had a hospital stay of 6·7 (2–21) days compared with 13·4 (4–33) days in patients with late leaks (P = 0·029). None of the patients who received conservative management (Fig. 1) had severe symptoms requiring ICU admission.

Patient delay

Information on duration of symptoms before hospital treatment was used as an indicator of patient delay and was available for 40 of the 45 patients whose leaks were treated surgically. Delay for more than 24 h predicted worse outcome (Table 3). Patients who were reoperated in 24 h or less had a hospital stay of 12·5 (2–90) days, compared with 24·4 (3–110) days for those who had experienced symptoms for more than 24 h before reoperation (P < 0·001). Six of 16 patients who were admitted late to the hospital needed ICU treatment, two of whom died after 1 and 7 days in the unit.

Table 3.

Outcomes in relation to time from onset of symptoms to start of treatment

| Delay ≤ 24 h (n = 24) | Delay > 24 h (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|

| Delay (h)* | 14·3 (5–24) | 43·3 (26–72) |

| No. requiring ICU treatment | 2 | 6 |

| Length of hospital stay (days)* | 12·5 (2–90) | 24·4 (3–110) |

| Patients admitted to ICU | (32, 90) | (1†, 7†, 23, 32, 40, 110) |

| Patients not admitted to ICU | 8·4 (2–33) | 14·0 (3–30) |

Values are median (range).

Patient died.

Discussion

Patients with apparent symptoms of leakage after LRYGB should undergo immediate operative intervention without further diagnostic evaluation. Preoperative resuscitation and management in the ICU should be reserved for physiologically compromised patients. CT is indicated before conservative treatment is considered in patients with milder symptoms of late leakage. Patient delay in reporting signs and symptoms, and delay in surgical treatment were both associated with adverse outcomes.

The benefit of bariatric surgery can be lost if complication rates are too high and patients are not managed appropriately. Notably, postoperative mortality strongly correlates with leakage1,4,7,26–28. The Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial29 stated that the survival benefit following bariatric surgery would have disappeared if perioperative mortality rates had been high. This level would be reached with a mortality rate of 3–4 per cent (L. Sjöström, personal communication). However, the observed mortality rate in the SOS study was 0·3 per cent29.

Most leaks occurring within 5 days were related to technical aspects of the operation. As the aetiology of leaks developing after more than 5 days has been reported to be more complex30, a 5-day cut-off for early versus late leaks was deemed appropriate. Further classification can include patient and doctor delay, severity and type of treatment. Some patients managed conservatively in the present series may possibly have been overdiagnosed, or could have been classified as having ‘microleakage’, infected haematoma or left lower-lobe pneumonia. Comparison between surgical and conservative treatments should be interpreted with caution as patients with more severe clinical symptoms were all treated surgically.

The leakage rate of 1·1 per cent in this series is comparable with that reported by other high-volume centres4,9,12,16. Most small studies reported leak rates varying from 0 to 10 per cent. In larger studies4,7,9,27,31 (more than 500 patients) the incidence of leaks varied from 0·1 to 4·3 per cent. A recent Scandinavian study8 had a leak rate higher than that reported here for a mixed group of high- and low-volume centres. However, when leak rates in different studies are compared it is important to note the definition of leakage, how severity was scored and whether registration was prospective or not.

Other studies4,9,32–34 have identified several risk factors for leakage, both technique- and patient-related. In the present series, comparison of patients with and without leakage revealed no significant differences in BMI, sex and age. At least half of the early leaks were probably due to technical insufficiency, in concordance with other studies35. Distal obstruction might have contributed to leakage in 16 patients. Insertion of a nasogastric tube before the start of operation is considered to be of utmost importance in preventing serious aspiration during intubation.

Two-thirds of the leaks occurred at the GE anastomosis where there is no bile or pancreatic enzymes. As long as there is no distal obstruction, percutaneous drainage of the abdominal cavity is the most important part of the treatment. In the authors' opinion, an aggressive attitude towards early reoperation reduces morbidity and hospital stay, as small leaks and bleeding can be resolved without a substantial increase in hospital stay. Few patients undergo unnecessary operation with this treatment strategy; here, only 14·2 per cent (15 of 106) had a negative early laparoscopy. Hospital stay in several studies11–13,34 reporting a more conservative treatment approach to leakage also seems to be longer than that after aggressive surgical treatment in the present series.

Acknowledgments

All authors are consultant surgeons employed by Aleris, but none is a stock or entity holder.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Goldfeder LB, Ren CJ, Gill JR. Fatal complications of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1050–1056. doi: 10.1381/096089206778026325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston EH. Complications of bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:853–868. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.04.007. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasquilla C, English WJ, Esposito P, Gianos J. Total stapled, total intra-abdominal (TSTI) laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: one leak in 1000 cases. Obes Surg. 2004;14:613–617. doi: 10.1381/096089204323093372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez AZ, Jr, DeMaria EJ, Tichansky DS, Kellum JM, Wolfe LG, Meador J, et al. Experience with over 3000 open and laparoscopic bariatric procedures: multivariate analysis of factors related to leak and resultant mortality. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8926-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fullum TM, Aluka KJ, Turner PL. Decreasing anastomotic and staple line leaks after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1403–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T. Complications of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 1040 patients – what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2000;10:509–513. doi: 10.1381/096089200321593706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y – 500 patients: technique and results, with 3–60 month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2000;10:233–239. doi: 10.1381/096089200321643511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry. Årsrapport SOReg 2011. http://www.ucr.uu.se/soreg/index.php/dokument/doc_download/36-arsrapport-soreg-2011 [accessed 1 September 2012]

- 9.Lee S, Carmody B, Wolfe L, Demaria E, Kellum JM, Sugerman H, et al. Effect of location and speed of diagnosis on anastomotic leak outcomes in 3828 gastric bypass cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:708–713. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurcisin BM, DeMaria EJ. Management of leak in the bariatric gastric bypass patient: reoperate, drain and feed distally. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1564–1566. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spyropoulos C, Argentou MI, Petsas T, Thomopoulos K, Kehagias I, Kalfarentzos F. Management of gastrointestinal leaks after surgery for clinically severe obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.04.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Csendes A, Burgos AM, Braghetto I. Classification and management of leaks after gastric bypass for patients with morbid obesity: a prospective study of 60 patients. Obes Surg. 2012;22:855–862. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards CA, Bui TP, Astudillo JA, de la Torre RA, Miedema BW, Ramaswamy A, et al. Management of anastomotic leaks after Roux-en-Y bypass using self-expanding polyester stents. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thaler K. Treatment of leaks and other bariatric complications with endoluminal stents. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1567–1569. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0859-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brolin RE, Lin JM. Treatment of gastric leaks after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a paradigm shift. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez R, Sarr MG, Smith CD, Baghai M, Kendrick M, Szomstein S, et al. Diagnosis and contemporary management of anastomotic leaks after gastric bypass for obesity. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical Issues Committee ASMBS. ASMBS guideline on the prevention and detection of gastrointestinal leak after gastric bypass including the role of imaging and surgical exploration. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callery CD, Filiciotto S, Neil KL. Collagen matrix staple line reinforcement in gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shikora SA. The use of staple-line reinforcement during laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1313–1320. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shikora SA, Kim JJ, Tarnoff ME. Comparison of permanent and nonpermanent staple line buttressing materials for linear gastric staple lines during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2007;142:621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried M, Hainer V, Basdevant A, Buchwald H, Deitel M, Finer N, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on surgery of severe obesity. Obes Facts. 2008;1:52–59. doi: 10.1159/000113937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsen HJ, Bergland A, Raeder J, Gislason HG. High-volume bariatric surgery in a single center: safety, quality, cost-efficacy and teaching aspects in 2000 consecutive cases. Obes Surg. 2012;22:158–166. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leifsson BG, Gislason HG. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with 2-metre long biliopancreatic limb for morbid obesity: technique and experience with the first 150 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:35–42. doi: 10.1381/0960892052993396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghajani E, Jacobsen HJ, Nergaard BJ, Hedenbro JL, Leifson BG, Gislason H. Internal hernia after gastric bypass: a new and simplified technique for laparoscopic primary closure of the mesenteric defects. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:641–645. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1790-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeMaria EJ, Murr M, Byrne TK, Blackstone R, Grant JP, Budak A, et al. Validation of the obesity surgery mortality risk score in a multicenter study proves it stratifies mortality risk in patients undergoing gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2007;246:578–582. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318157206e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith MD, Patterson E, Wahed AS, Belle SH, Berk PD, Courcoulas AP, et al. Thirty-day mortality after bariatric surgery: independently adjudicated causes of death in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1687–1692. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0497-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Swedish Obese Subjects Study Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubay DA, Franz MG. Acute wound healing: the biology of acute wound failure. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:463–481. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higa KD, Ho T, Boone KB. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: technique and 3-year follow-up. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:377–382. doi: 10.1089/10926420152761905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballesta C, Berindoague R, Cabrera M, Palau M, Gonzales M. Management of anastomotic leaks after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2008;18:623–630. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livingston EH, Ko CY. Assessing the relative contribution of individual risk factors on surgical outcome for gastric bypass surgery: a baseline probability analysis. J Surg Res. 2002;105:48–52. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas H, Agrawal S. Systematic review of obesity surgery mortality risk score –preoperative risk stratification in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1135–1140. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brady R, Vroegop T, Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1290–1298. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]