Abstract

Aggregation of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP) has been implicated in the development of type II diabetes. Because IAPP is a highly amyloidogenic peptide, it has been suggested that the formation of IAPP amyloid fibers causes disruption of the cellular membrane and is responsible for the death of β-cells during type II diabetes. Previous studies have shown that the N-terminal 1–19 region, rather than the amyloidogenic 20–29 region, is primarily responsible for the interaction of the IAPP peptide with membranes. Liposome leakage experiments presented in this study confirm that the pathological membrane disrupting activity of the full-length hIAPP is also shared by hIAPP1–19. The hIAPP1–19 fragment at a low concentration of peptide induces membrane disruption to a near identical extent as the full-length peptide. At higher peptide concentrations, the hIAPP1–19 fragment induces a greater extent of membrane disruption than the full-length peptide. Similar to the full-length peptide, hIAPP1–19 exhibits a random coil conformation in solution and adopts an α-helical conformation upon binding to lipid membranes. However, unlike the full-length peptide, the hIAPP1–19 fragment did not form amyloid fibers when incubated with POPG vesicles. These results indicate that membrane disruption can occur independently from amyloid formation in IAPP, and the sequences responsible for amyloid formation and membrane disruption are located in different regions of the peptide.

Introduction

One of the most striking hallmarks of type II diabetes is the presence of highly aggregated amyloid deposits of human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide—Protein (hIAPP) in the islets of Langerhans of pancreatic β-cells. Because of the high tissue visibility of the amyloid deposits and their prevalence in diabetic patients but not in nondiabetic individuals, it has been assumed that fibrillization of IAPP plays an important role in the pathogenic development of the disease.1 The link between the formation of amyloid fibers by IAPP and loss of β-cell mass in type II diabetes has been further supported by in vitro studies which have shown that species which do not spontaneously develop type II diabetes, such as rats, have an IAPP variant which is nonamyloidogenic.2 The putative link between IAPP fiber formation and β-cell death has inspired numerous studies on the mechanism of amyloid fiber formation and the structures of fibers formed by IAPP and its fragments.3 However, the role of IAPP aggregation in the etiology of type II diabetes has been obscured by the apparent inertness of the fibers themselves; matured fibers formed from IAPP in solution exert only a minimal cytotoxic effect on pancreatic β-cells,4,5 a finding also reflected in studies of other diseases associated with amyloidogenic peptides.6,7

Amyloid fibers are not the only aggregation state observed with IAPP. Instead of mature amyloid fibers, small oligomeric species of hIAPP and other amyloid proteins have been implicated in disturbing cellular homeostasis by disrupting the cellular membrane, through either the formation of ion channels or a nonspecific general disruption of the lipid bilayer.7,8 The process by which these toxic oligomers are formed is a matter of controversy; it is not known if the oligomers are “on-pathway” intermediates that convert into amyloid fibers9 or are “off-pathway” byproducts that arise independently of fiber formation.5,6,10 One of the inherent difficulties in answering this question is the conformational instability of the IAPP peptide and other amyloidogenic proteins; monomeric IAPP rapidly converts to a fibril form leading to a heterogeneous distribution of conformational states in the sample.

Peptide fragments of IAPP have been useful in simplifying the analysis of the complex aggregation process of IAPP by determining which residues are essential for both the cytotoxicity and the amyloidogenesis of the peptide. In particular, variances of the IAPP sequence within the 20–29 region have been used to explain the relative toxicity of different versions of the peptide because the ability of IAPP to form amyloid fibers has been shown to strongly correlate with the peptide sequence within this region of the peptide.2,10,11 However, despite the strong tendency of the IAPP20–29 fragment to form amyloid fibers, the toxicity of this fragment is significantly lower than that of the full-length peptide.4,12 The interaction of amyloid proteins with the cellular membrane is believed to be crucial for their cytotoxic activity through both the direct disruption of membrane integrity and by catalyzing the formation of toxic oligomers.13 The 20–29 fragment, while amyloidogenic, has a much lower affinity for phospholipid membranes than the full-length peptide.11

It has previously been shown through fluorescence anisotropy, infrared reflection–absorption spectroscopy, and lipid monolayer expansion experiments that the N-terminal part of IAPP is the primary membrane binding site of IAPP.11,14,15 Indeed, the 1 – 19 fragment of human IAPP (hIAPP1–19) inserts into lipid membranes with a higher efficiency than full-length IAPP.11 We report here that the N-terminal region of the peptide (residues 1 – 19) can disrupt synthetic lipid vesicles to a similar extent as the full-length IAPP peptide without forming amyloid fibers and may therefore be an important model for the study of membrane disruption by IAPP and other amyloid proteins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

POPG was obtained from Avanti (Alabaster, AL); DMSO, thioflavin T, carboxyfluorescein, and HFIP were from Sigma-Aldrich; Full-length hIAPP with an amidated C-terminus (>95% purity) was purchased from Anaspec (San Jose, CA). The hIAPP1–19 and hIAPP20–29 peptides were synthesized using standard FMOC (9-fluornylmethoxycarbonyl) methods. A PAL-PEG resin was used to provide an amidated C-terminus. Standard FMOC reaction cycles were used. The first residue attached to the resin, every β-branched residue, and every residue immediately following a β-branched residue were double coupled. Peptides were cleaved from the residue using standard trifluoroacetic acid protocols and purified using a reversed-phase C18 column with an acetonitrile/water gradient and trifluoroacetic acid as an ion-pairing agent. The hIAPP20–29 peptide was synthesized as described above but with both an amidated C-terminus and an acetylated N-terminus. After synthesis, the crude hIAPP1–19 peptide was subjected to air oxidation to form the disulfide bond. The identity of the hIAPP1–19 and hIAPP20–29 sequences and formation of the disulfide bond for hIAPP1–19 was verified by electrospray mass spectroscopy. Peptide purity was measured as greater than 95% by analytical HPLC.

Vesicle Preparation

POPG vesicles for the circular dichroism (CD) and dye leakage experiments were prepared by first dissolving the POPG lipid in chloroform at a concentration of 20 mg/mL. The solvent was removed from the lipid sample by first evaporating the chloroform under a stream of nitrogen gas to deposit a thin lipid film on the walls of a glass test tube and then drying the sample under a vacuum overnight to completely remove any residual solvent. The dry lipid film was then rehydrated in the appropriate buffer to make multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) at a concentration of 40 mg/mL. The MLVs were then subjected to 10 freeze–thaw cycles to equilibrate the vesicles with the buffer. Large unilamellar vesicles were made from MLVs in the previous step by extruding the sample 21 times through a 100 nm polycarbonate filter. For the dye leakage experiments, carboxyfluorescein containing POPG vesicles were prepared by rehydrating the dried lipid film in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 40 mM carboxyfluorescein. Nonencapsulated carboxyfluorescein was removed from vesicles through size exclusion chromatography using a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Phospholipid concentrations were quantified by the method of Stewart. Vesicle solutions were used immediately; a fresh vesicle solution was used for each experiment.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Lyophilized hIAPP and hIAPP1–19 were dissolved in HFIP for 1 h to obtain a 4 mg/mL stock solution. Aliquots of the peptide stock solution were lyophilized again and then resolubilized in either 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3 or 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 150 mM NaF, pH 7.3. After resolubilization, the peptide solutions were briefly vortexed and sonicated (approximately 15 s) and transferred to a 0.1 cm cuvette. After the initial spectrum of hIAPP in solution was taken, POPG vesicles from a 40 mg/mL stock solution were added to the cuvette to achieve a 400 µM final concentration. Spectra were measured at 1 nm intervals from 190–260 nm at a scanning speed of 50 nm/min and a bandwidth of 5 nm. Each spectrum reported is the average of four scans after subtraction of the baseline spectrum (buffer and vesicles without peptide). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (approximately 23 °C). The secondary structure was estimated qualitatively using the CONTINLL algorithm within the CDPRO program, using the SMP56 basis set (43 soluble proteins and 13 membrane proteins).16 We consider these results to be qualitative as the analysis of the secondary structure of short peptides by optical techniques (like CD) must be treated with caution as they were parametrized for large proteins and some uncertainty exists in their application to peptides of a much shorter length. In particular, peptides (such as IAPP) existing in a variety of conformational states and having a strong tendency to stick to surfaces can be especially difficult to study by CD. For these reasons, we did not attempt to determine the exact secondary structure of the peptide but instead listed an approximate number to indicate the gross structural changes that accompany membrane binding and amyloid fiber formation. Three independent techniques—electron microscopy, thioflavin T binding, and circular dichroism spectroscopy—were used to verify the presence of amyloid formation. The time constants for the conformational change of the full-length peptide determined by thioflavin T fluorescence and CD spectroscopy are in close agreement with each other and with previous values in the literature.14

Dye Leakage

Stock solution of the hIAPP and hIAPP1–19 peptides in HFIP were prepared as above-described for the CD experiments. After lyophilization of the HFIP stock solution, 10 mg/mL peptide stock solutions were prepared from pure DMSO. For each data point, the baseline fluorescence of the empty and dye-encapsulated POPG vesicles was measured for 15 s. Peptide from the DMSO stock solution was then added, and the fluorescence was recorded at 100 s after the addition of the peptide. Finally, the increase in fluorescence induced by total disruption of the lipid vesicles was measured by the addition of Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 0.2%. The dye leakage is reported according to the following equation:

| (1) |

All dye leakage experiments were conducted at room temperature (approximately 23 °C) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. Each experiment was repeated three times from separate stock solutions of the peptide.

Thioflavin T Fluorescence

Peptide/lipid unilamellar vesicles (27.5 µM peptide, 440 µM lipid) were prepared as described above for the CD experiments. A concentrated Thioflavin T stock solution (250µM) was added to the sample (final Thioflavin T concentration 25 µM), and the emission at 486 nm was measured as a function of time using excitation at 450 nm. The t1/2 value was calculated as the time point in which the change in intensity was equal to one-half of the maximum change in intensity.

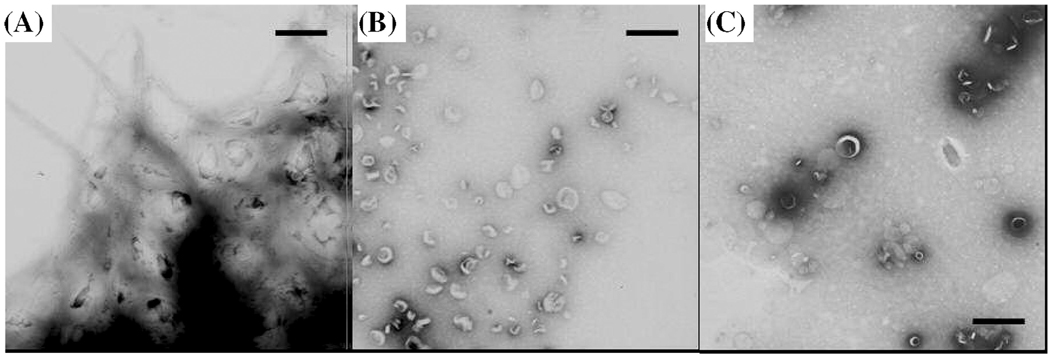

Electron Microscopy

Aliquots (10 µL) collected from the CD experimental sample were incubated on Formvar-coated copper grids (Ernest F. Fullam, Inc., Latham, NY) for 2 min, washed twice with 10 µL of deionized water, and then negatively stained for 90 s with 2% uranyl acetate. The incubation times were 7 days for the full-length hIAPP sample and 15 days for the hIAPP1 – 19 sample and the vesicle sample without peptide. Samples were imaged with a Philips CM10 Transmission Electron Microscope.

Results and Discussions

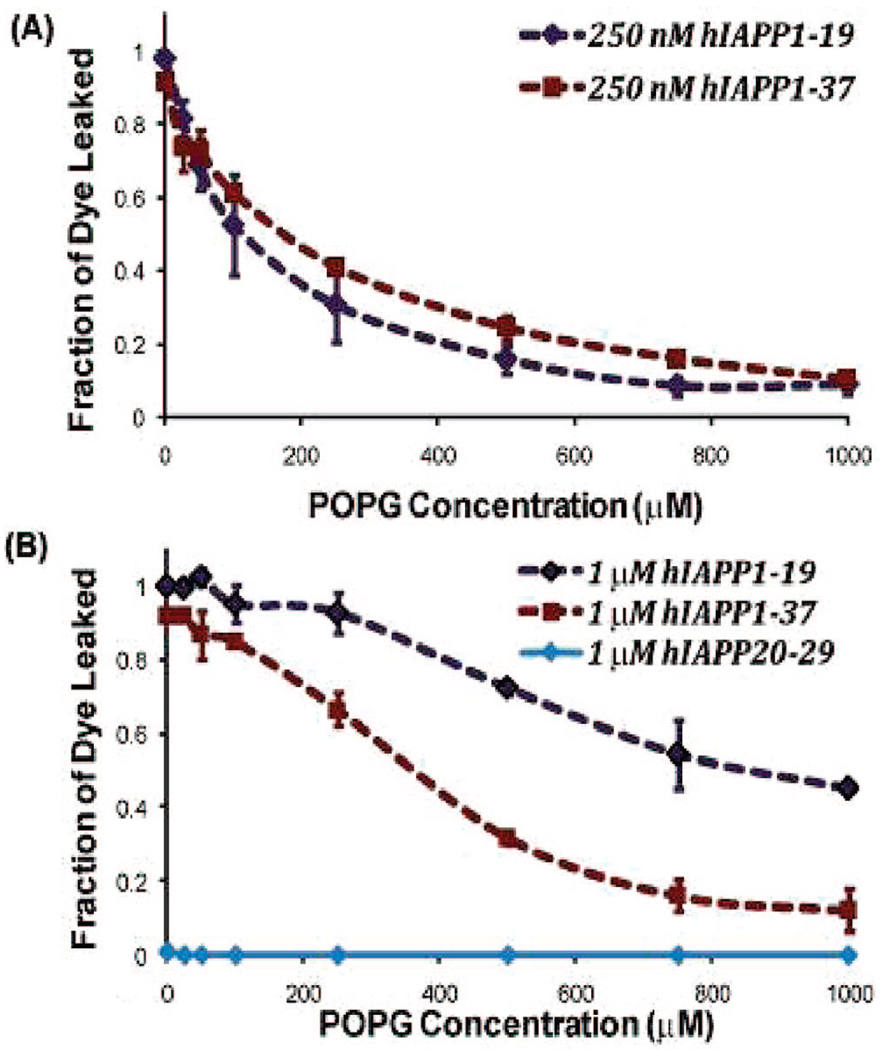

To test the extent of membrane disruption induced by the full-length hIAPP and the hIAPP1–19 peptide, the leakage of the carboxyfluorescein dye from large unilamellar POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) vesicles was measured (Figure 1). At low peptide concentrations (250 nM), hIAPP1–19 induced membrane disruption to a near identical extent as in the case of the full-length IAPP peptide. At higher peptide concentrations (1 mM), hIAPP1–19 is more effective in inducing membrane disruption than the full-length IAPP peptide, most likely due to the full-length peptide’s tendency to form inert fibrillar aggregates above a critical concentration necessary for fiber formation. The amyloidogenic 20–29 fragment did not induce any detectable membrane disruption (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dye leakage from POPG vesicles induced by the full-length hIAPP and the hIAPP1–19 fragment. Carboxyfluorescein containing POPG liposomes (1.5 mM) were added to 250 nM (A) or 1 mM (B) solutions of either full-length hIAPP or the hIAPP1–19 fragment along with the listed concentrations of dye-free POPG liposomes. The fraction of dye leaked was recorded at 100 s. Each experiment was repeated three times; error bars indicate 1 standard deviation from the average. All experiments were performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.5.

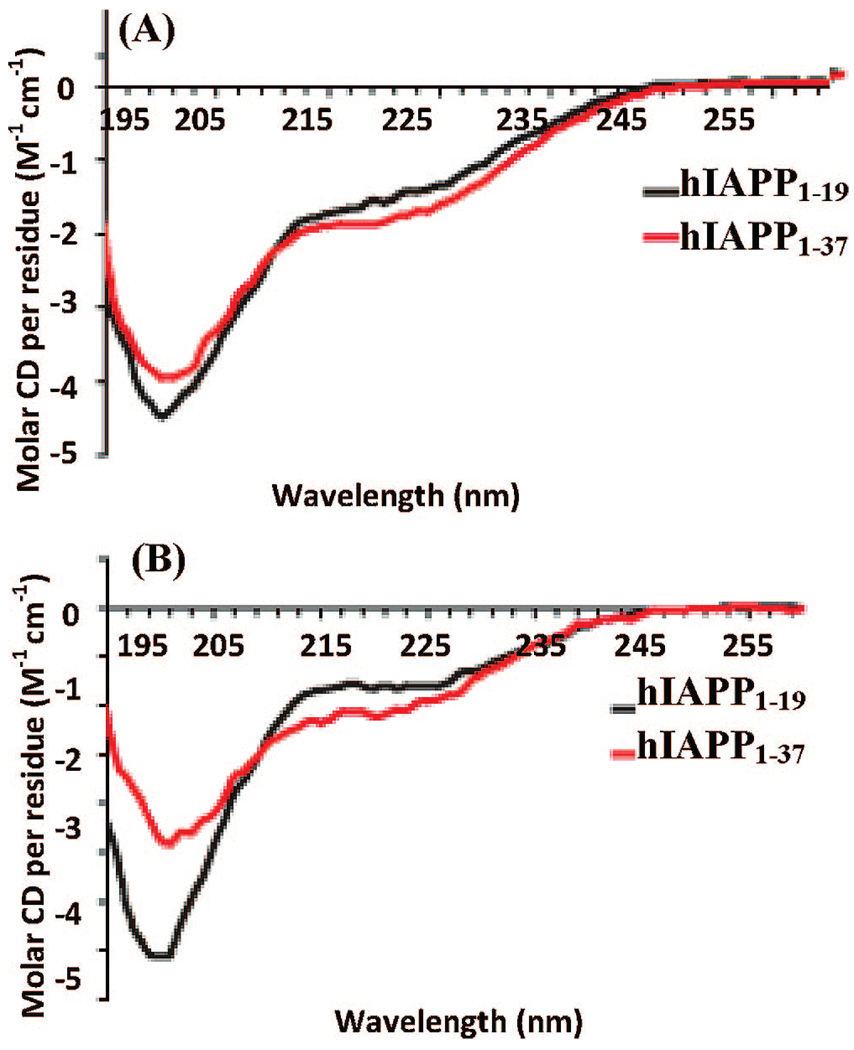

To investigate the relationship between amyloid fiber formation and membrane disruption by hIAPP and its 1 – 19 fragment, conformational changes of the peptides associated with membrane binding and fiber formation were measured by CD in both low (10 mM phosphate buffer) and high (10 mM phosphate buffer and 150 mM NaF) ionic strength solutions. The overall secondary structures of both peptides are initially similar both in solution and in the presence of POPG liposomes. The hIAPP1–19 fragment appears to be completely unstructured in solution (Figure 2). The full-length hIAPP also primarily showed a random coil conformation (Figure 2A); however, at a high ionic strength it also contains a small degree of β-sheet structure (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

CD spectra of hIAPP1–19 (black solid line) and the full-length hIAPP (red line) peptides in (A) a low ionic strength (25 µM, sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.3) solution and (B) a high ionic strength (25 µM, sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.3 with 150 mM NaF) solution. The lower intensity of the signal from the full-length peptide may be indicative of a lower solubility at a higher ionic strength.

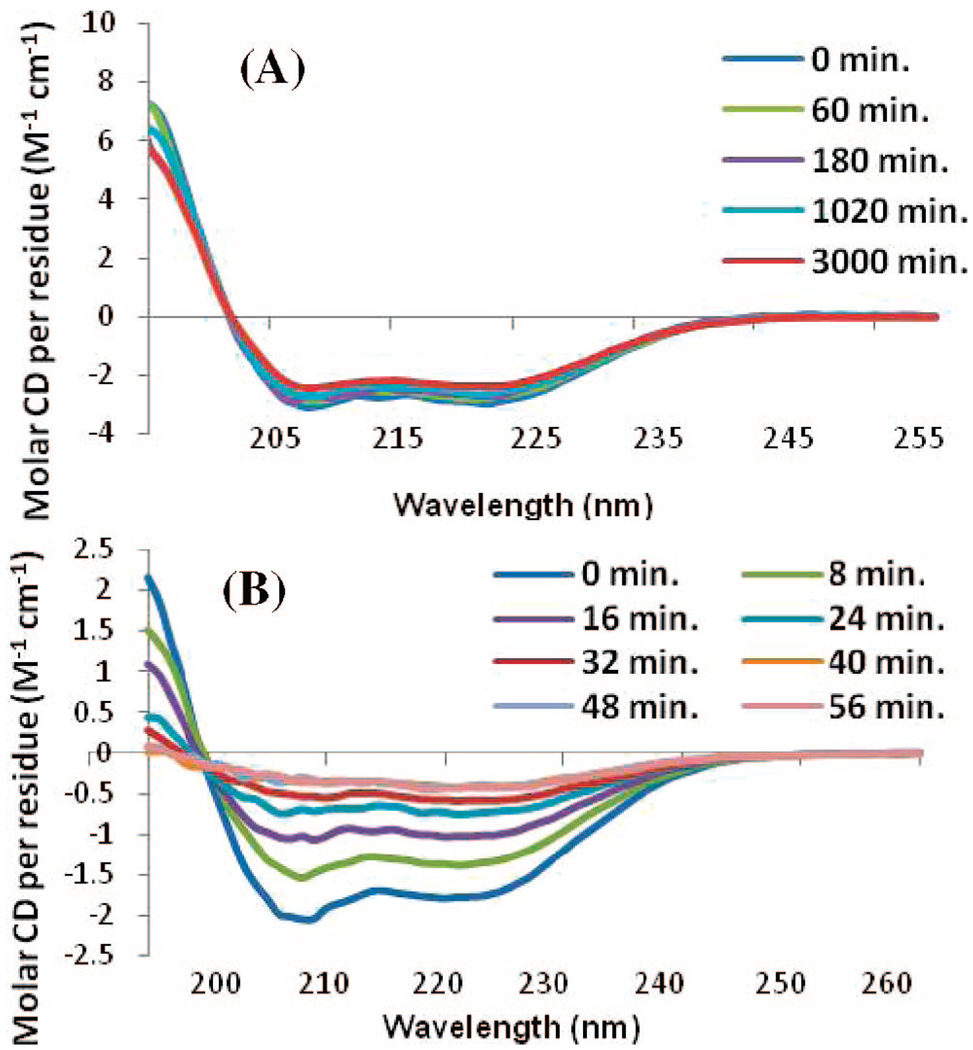

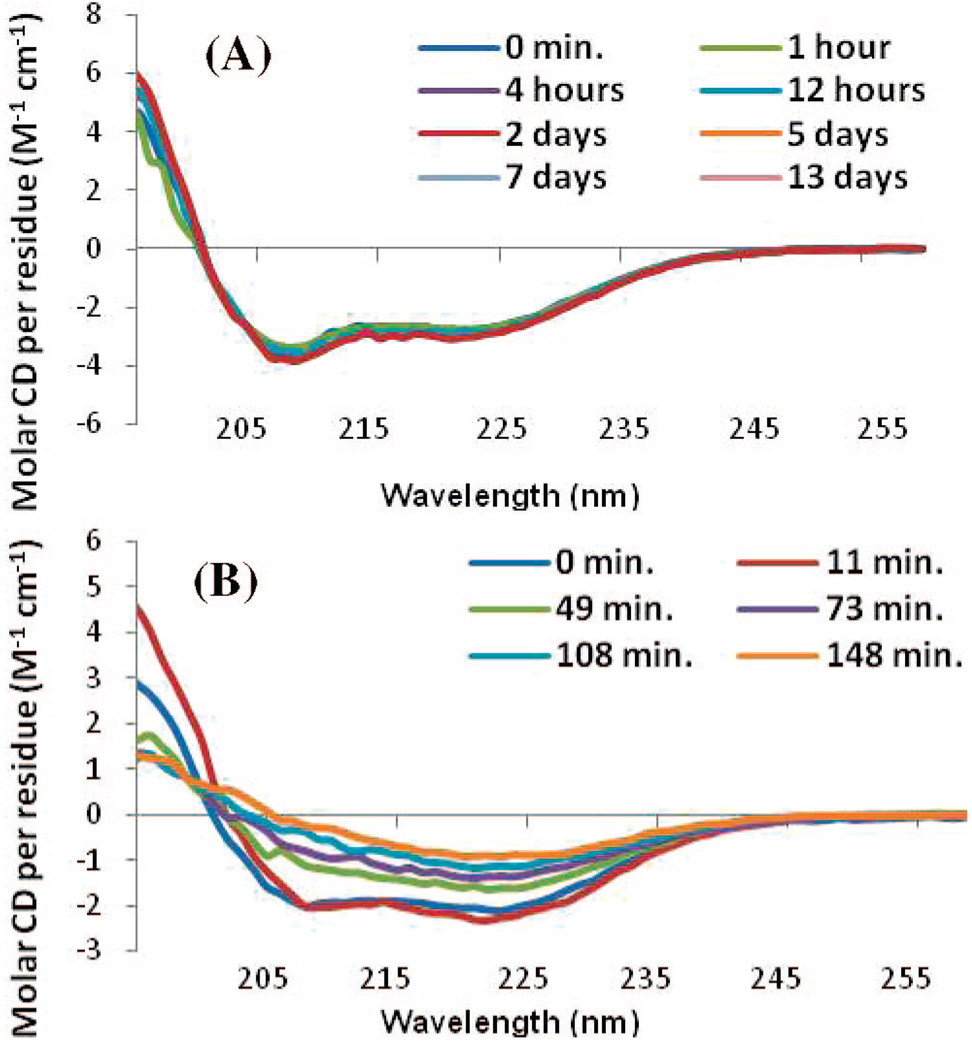

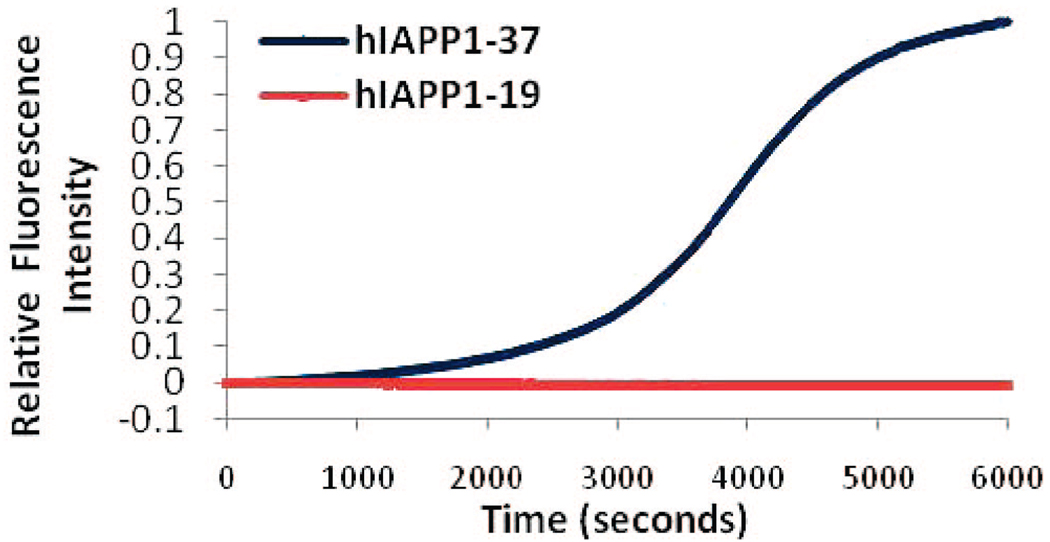

Upon the addition of POPG liposomes, both the full-length and hIAPP1–19 peptides adopt a primarily α-helical structure.19 The hIAPP1–19 peptide remained stable in this conformation for at least 17 h (Figure 3A). After this time, aggregation of the lipid vesicles was visible to the naked eye and the CD signal diminished in intensity without altering shape. The full-length peptide has previously been shown to facilitate the aggregation of liposomes at a low ionic strength.20 Importantly, the CD signal showed no evidence of β-sheet structure indicative of amyloid fiber formation. On the other hand, the full-length IAPP peptide showed a conformational change from a predominantly α-helical structure to a β-sheet structure indicative of amyloid fiber formation within 40 min after the addition of POPG liposomes (Figure 3B). At a higher ionic strength closer to the physiological range (150 mM NaF), hIAPP1–19 remained stable in an α-helical conformation for at least 13 days without the CD signal diminishing in intensity or aggregation of the lipid vesicles (Figure 4A). The full-length peptide, by contrast, showed conversion of the initial α-helical structure to a β-sheet conformation indicative of amyloid fiber formation (Figure 4B). A Thioflavin T fluorescence assay in the presence of POPG liposomes revealed a t1/2 for amyloid fiber formation for the full-length peptide of 64 min, similar to previous reports in the literature (Figure 5).21 The hIAPP1–19 peptide did not induce any increase in the fluorescence of THT over the duration of the experiment indicating a lack of amyloid fiber formation for this peptide. Thioflavin T itself has been shown not to inhibit amyloid fiber formation by IAPP.6b

Figure 3.

CD spectra of (A) hIAPP1–19 and (B) full length IAPP in a low ionic strength solution (25 µM, sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.3) measured as a function of time after the addition of 400 µM POPG large unilamellar vesicles.

Figure 4.

CD spectra of (A) hIAPP1–19 and (B) full-length hIAPP in a high ionic strength solution (25 µM, sodium phosphate buffer and 150 mM NaF at pH 7.3) measured as a function of time after the addition of 400 µM POPG large unilamellar vesicles.

Figure 5.

Binding of the amyloid-specific dye Thioflavin T to hIAPP1–19 and full-length hIAPP measured by fluorescence. Thioflavin T (25 µM) was incubated with 25 µM of either the full-length hIAPP peptide or the 1–19 fragment and 400 µM of POPG large unilamellar vesicles.

To confirm the absence of amyloid fiber formation for hIAPP1–19, negative stain electron microscopy was performed on aliquots from the final time points of the CD experiment. In electron micrographs of the sample of full-length hIAPP containing POPG vesicles, amyloid fibers can be seen branching out from the POPG vesicles (Figure 5A). Remarkably, amyloid fibers were not detected with hIAPP1–19, confirming the absence of amyloid formation for hIAPP1–19 (Figure 5B).

It should be noted that several related sequences within the N-terminal region of the IAPP peptide have been shown to be weakly amyloidogenic.21,22 Aged solutions of the 1 – 18 sequence at a very high peptide concentration (2.14 mM) form both isolated amyloid fibers and an amorphous precipitate.21 However, FTIR spectroscopy showed that the amyloid fibers detected in the EM studies to compose only a minor fraction of the sample and the self-association of the amyloid fibers formed from hIAPP1–19 to be much less than the self-association of amyloid fibers formed from the full-length peptide. The 8–20 amino acid sequence of IAPP has also been shown to be weakly amyloidogenic.22 Nevertheless, there are important differences between the hIAPP8–20 and hIAPP1–19 fragments. The disulfide bridge between residues 2 and 7 conformationally restricts this region of the IAPP peptide from adopting a β-sheet conformation and may influence the amyloidogenicity of the entire peptide.23 In addition, both of these studies were done in solution, without the presence of lipid vesicles. Lipid vesicles may be expected to alter the energetics of amyloidogenesis by burying hydrophobic residues that are exposed in solution within the interior of the membrane.

Our results indicate that amyloid fiber formation is not necessary for the membrane disrupting activity of the hIAPP peptide. It is well-established that amyloid fibers themselves are not especially toxic,4,5 but it is a subject of active debate whether the process of amyloid formation is necessary for the generation of toxic intermediates and the membrane disrupting activity of amyloid peptides. Our results suggest that the membrane disrupting activity of hIAPP can be achieved irrespective of amyloid formation and occurs primarily as a result of other factors not necessarily related to amyloidogenesis.24 One of the strongest pieces of evidence for a dominant role of amyloid formation in the cytotoxicity of IAPP is the lack of a cytotoxic response by the nonamyloidogenic rat variant of IAPP. Knight et al. have recently shown, however, that the nonamyloidogenic rat variant of IAPP shows some membrane disrupting activity.18 The detection of a small degree of β-cell apoptosis in diabetic rats also supports the conclusion that rat IAPP can be toxic, albeit to a lesser degree than the human IAPP.25 The binding of IAPP to the membrane is cooperative and dependent on the formation of small oligomers on the surface of the membrane. In addition to being unable to form amyloid fibers, rat IAPP is less effective at forming the small oligomers necessary for membrane binding than human IAPP.18 The difference in toxicity between the rat and human versions of IAPP therefore may largely be due to a difference in the formation of these small oligomers rather than the inability of rat IAPP to form amyloid fibers.

It is likely that several processes that lead to cell death are simultaneously operational in the in vivo setting, some of which are dependent on the formation of amyloid fibers and others which are not. The instability of the proposed toxic intermediates, a particularly acute problem for the IAPP peptide due to its extremely fast rate of aggregation, considerably complicates analysis. The hIAPP1–19 fragment, which does not form amyloid fibers but disrupts membranes to a similar extant as that for the full-length peptide, will be a useful tool to disentangle this complex process.

Previous studies of the secondary structure of hIAPP have shown that residues 1–7 and 19–37 are likely to be disordered after the peptide initially binds to the membrane.15 Packing density arguments suggest that the N-terminal segment of the hIAPP peptide (residues 1–18) adopts a transmembrane orientation, while the C-terminal region is believed to lie outside the membrane in a disordered state.13,15,18 The formation of secondary structure in the C-terminal region is expected to drive the process of amyloidogenesis in the full-length hIAPP peptide.18,26 The hIAPP1–19 peptide shows a similar amount of helical content to that of the full-length peptide (Figure 2A). However, the N-terminal segment (residues 1–7) is conformationally constrained from adopting a secondary structure by the presence of a disulfide bond between residues 2 and 7.23 Without the formation of an additional secondary structure as a driving force, the amyloidogenic propensity of hIAPP1–19 is expected to be far less than that of the full-length peptide. Nevertheless, the amphipathic helical structure of the full-length peptide implicated in membrane-disrupting properties is retained in hIAPP1–19.18

Because of the stability of the hIAPP1–19 fragment in membranes, we expect that it will be useful as a model system to study the membrane disrupting effects of hIAPP and other amyloid peptides, using high-resolution techniques such as solid-state NMR spectroscopy, without the complications introduced by time-dependent aggregation.

Figure 6.

(A) Electron micrograph images of POPG vesicles incubated with full-length hIAPP for 7 days prior to measurement. Amyloid fibers of hIAPP can be seen branching out from the POPG vesicles. (B) Electron micrograph images of POPG vesicles incubated with hIAPP1–19 for 15 days prior to the measurement. Amyloid fibers were not detected; the circular structures are indicative of POPG vesicles. (C) Electron micrograph images of POPG vesicles incubated without a peptide for 15 days prior to measurement. The scale bars represent 500 nm.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for the assistance of Xuan Wang in the electron microscopy studies. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (to A.R.), the NIH (R01AI054515 to A.R. and R21DK074714 to A.G.), and the American Diabetes Association (7-06-RA-48 to A.G.).

References

- 1.Hoppener JW, Nieuwenhuis MG, Vroom TM, Lips CJ. New Eng. J. Med. 2000;144:1995–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westermark P, Engstrom U, Johnson KH, Westermark GT, Betsholtz C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:5036–5040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Luca S, Yau W-M, Leapman R, Tycko R. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13505–13522. doi: 10.1021/bi701427q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tycko R. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;4:500–506. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Makin OS, Serpell LC. FEBS J. 2005;272:5950–5961. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mascioni A, Porcelli F, Ilangovan U, Ramamoorthy A, Venglia G. Biopolymers. 2003;69:29–41. doi: 10.1002/bip.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konarkowska B, Aitken JF, Kistler J, Zhang SP, Cooper GJS. FEBS J. 2006;273:3614–3624. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier JJ, Kayed R, Lin CY, Gurlo T, Haataja L, Jayasinghe S, Langen R, Glabe CG, Butler PC. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;291:E1317–E1324. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00082.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Necula M, Breydo L, Milton S, Kayed R, van der Veer WE, Tone P, Glabe CG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8850–8860. doi: 10.1021/bi700411k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Necula M, Kayed R, Milton S, Glabe CG. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10311–10324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira ST, Vieira MNW, De Felice FG. IUMB Life. 2007;59:332–345. doi: 10.1080/15216540701283882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Janson J, Ashley RH, Harrison D, McIntyre S, Butler PC. Diabetes. 1999;48:491–498. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R, Milton SC, Parker I, Glabe CG. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:17294–17300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Anguiano M, Nowak RJ, Lansbury PT., Jr Biochemistry. 2002;41:11338–11343. doi: 10.1021/bi020314u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mirzabekov TA, Lin MC, Kagan BL. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1988–1992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparr E, Engel MF, Sakharov DV, Sprong M, Jacobs J, de Kruijff B, Hoppener JW, Killian JA. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brender JR, Dürr UHN, Heyl D, Budarapu MB, Ramamoorthy A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2026–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Goldsbury C, Goldie K, Pellaud J, Seelig J, Frey P, Muller SA, Kistler J, Cooper GJS, Aebi U. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:352–362. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ruschak AM, Miranker AD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:12341–12346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenidis K, Waldner M, Bernhagen J, Fischle W, Bergmann M, Weber M, Merkle ML, Voelter W, Brunner H, Kapurniotu A. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:1055–1071. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1168:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel MFM, Yigittop H, Elgersma RC, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ, de Kruijff B, Hoppener JWM, Killian JA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;356:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight JD, Miranker AD. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes DHJ, Meister A, Gohlke A, Hauser A, Blume A, Winter R. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3132–3141. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Protein Sci. 2004;13:100–112. doi: 10.1110/ps.03258404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight JD, Hebda JA, Miranker AD. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9496–9508. doi: 10.1021/bi060579z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12113–12119. doi: 10.1021/bi050840w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurganov B, Doh M, Arispe N. Peptides. 2004;25:217–232. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapurniotu A. Bioplymers. 2001;60:438–459. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<438::AID-BIP10182>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaikaran ETAS, Higham CE, Serpell LC, Zurdo J, Gross M, Clark A, Fraser PE. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:515–525. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Kajava AV, Aebi U, Steven AC. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Koo BW, Miranker AD. Protein Sci. 2005;14:231–239. doi: 10.1110/ps.041051205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshiike Y, Kayed R, Milton SC, Takashima A, Glabe CG. Neuromol. Med. 2007;9:270–275. doi: 10.1007/s12017-007-0003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:2498–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wimley WC, Hristova K, Ladokhin AS, Silvestro L, Axelsen PH, White SH. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:1091–1110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]