Abstract

Despite a multitude of recent technical breakthroughs speeding high-resolution structural analysis of biological macromolecules, production of sufficient quantities of well-behaved, active protein continues to represent the rate-limiting step in many structure determination efforts. These challenges are only amplified when considered in the context of ongoing structural genomics efforts, which are now contending with multi-domain eukaryotic proteins, secreted proteins, and ever-larger macromolecular assemblies. Exciting new developments in eukaryotic expression platforms, including insect and mammalian-based systems, promise enhanced opportunities for structural approaches to some of the most important biological problems. Development and implementation of automated eukaryotic expression techniques promises to significantly improve production of materials for structural, functional, and biomedical research applications.

Introduction

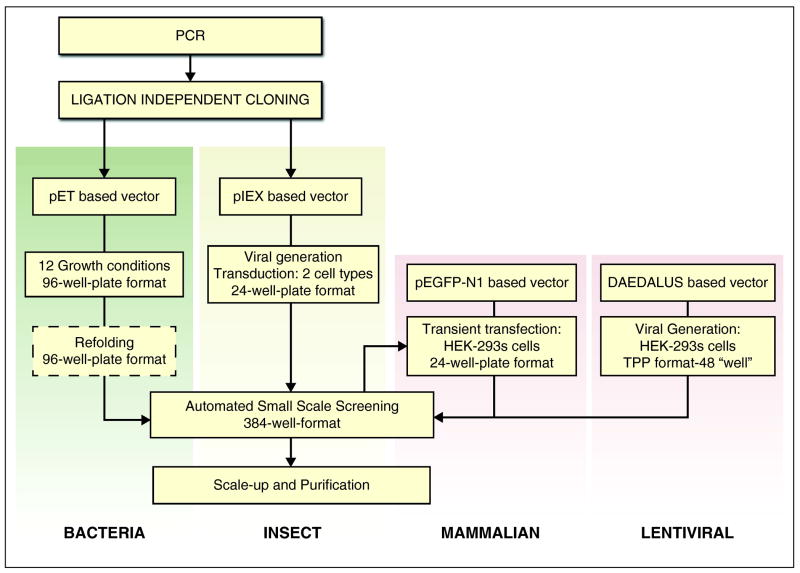

Structural genomics programs have been underway for more than a decade in North America, Europe, and Asia. Notwithstanding considerable collective successes, large-scale expression of properly folded, biologically active eukaryotic proteins remains a formidable technical challenge. Protein features that correlate with difficulties in expression and purification include, but are by no means limited to, size, the presence of disulfide bridges, the presence of low complexity regions, and the need for obligate small molecule and/or protein ligands. This mini-review recounts some of the experiences and perspectives of the New York Structural Genomics Research Consortium (NYSGRC), which began operations in 2000 under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Protein Structure Initiative (PSI; http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/FeaturedPrograms/PSI/). Figure 1 illustrates the current NYSGRC pipeline. A commentary emphasizing both on capabilities and remaining challenges follows.

Figure 1.

The NYSGRC expression/purification pipeline. Departing from traditional structural genomics pipelines focused largely on prokaryotic targets, the NYSGRC manages four independent expression pipelines to meet current challenges of Protein Structure Initiative.

Prokaryotic expression systems

After more than a decade of technology development, high-throughput production of recombinant proteins using prokaryotic hosts is well established at a number of international centers [1–6]. Structural genomics pipelines invariably begin with parallel cloning and small-scale expression validation (96-well or 384-well format) followed by larger scale expression/purification. Arrayed PCR products derived from independent primer pairs are purified either manually or via automated liquid handling using vacuum based methods or magnetic resin systems. Expression clones are generated with restriction enzyme-free cloning (Ligation-independent cloning [7], PIPE [8], Gateway [9], etc.) into an appropriate vector, and transformed cells are plated in 24-well or 48-well format [1–5,8,9]. Sequence verified clones are subjected to small-scale expression testing in engineered E. coli hosts, utilizing specialized high-density growth incubators to identify constructs amenable to prokaryotic expression [10]. Well-behaved targets are then scaled up and typically purified via immobilized metal affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography [4].

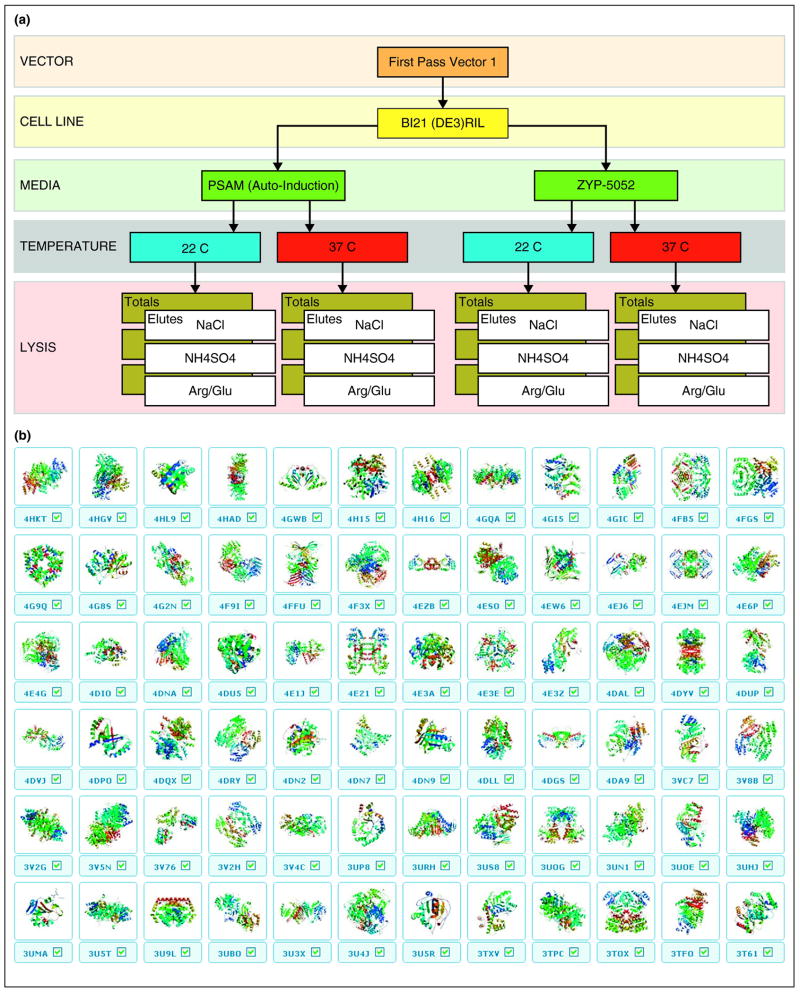

Recent advances have focused on increasing efficiency, lowering costs, and reducing target attrition via utilization of fusion tags, optimal growth conditions, refolding, etc. Enhanced expression screening has relied on automation to boost throughput, decrease process volumes (sub 1 mL scale), and ultimately reduce costs. Most notable are the use of liquid handling robotics coupled with magnetic resins (GE) or 96-channel based micro-columns (Phynexus, [11]) for automated purification, followed by microfluidic-based sample analysis (e.g. 384-well capillary electrophoresis, PerkinElmer GXII). Together, these methods permit facile screening of >1000 targets (or constructs, expression conditions, etc.) per week. Vincentelli et al. described systematic screening of culture conditions (4 choices of media, 3 temperature settings) and/or fusion-tags (5 different fusion partners) to optimize soluble protein production [12]. Evaluation of small-scale expression conditions for >1000 targets yielded a streamlined expression protocol, which increased average yields 10-fold to 100-fold versus standard protocols [12]. Pacheco et al. utilized a similar approach to arrive at a scheme that delivered soluble protein in ~80% of cases [13]. Bird et al. constructed a suite of nine expression vectors supporting fusion of the target protein at its N-terminus with various stabilizing tags (NusA, SUMO, MBP, etc.) [14]. This strategy, when combined with high-throughput small-scale expression testing, enables rapid/parallel identification of optimal construct design/expression protocol combinations for each target. The NYSGRC small-scale expression screening strategy incorporates many of such features and is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The NYSGRC prokaryotic screening pipeline. (a) To reduce attrition and address recalcitrant targets, the NYSGRC and others have leveraged automated small-scale expression efforts to screen multiple expression vectors against multiple host cell lines, growth media, temperature and lysis conditions to rapidly identify the optimal conditions for growth, expression and purification. Following ligation independent cloning into an N-terminal TEV cleavable HIS vector (pET30 based, First pass Vector 1), the NYSGRC screens for expression in a phage resistant version of BL21(DE3) harboring a plasmid encoding rare tRNAs (RIL). These cells are grown in 96-well deep block plates using two types of autoinduction media: the fully defined PSAM media and the ultra-rich ZYP-5052 media based on yeast extract. Cultures are grown at two temperatures (22°C and 37°C), and cells are lysed and purified on 96-well Ni-IDA plates with three different buffer systems [20 mM HEPES, PH 7.5, 20 mM Imadazole, 10% Glycerol, 0.1%Tween 20, supplemented with either 500 mM NaCl (NaCl), 200 mM ammonium sulfate (NH4SO4) or 500 mM NaCl plus 50 mM Arginine and 50 mM Glutamine (Arg/Glu)]. Total cellular fractions (Totals) and eluted fractions (Elutes) are analyzed using a Caliper GXII, scored and positive expressors proceed to scale up. Of note, one protein screened using this process results in 24 gel lanes. Depending on the value of the target, this process can be repeated for failures against rescue vectors (e.g. C-terminal HIS fusions, N-terminal SUMO, MBP) or other cell lines (e.g. C41/43, SoluBL21). (b) Collection of 72 structures determined from the nitrogen fixing symbiotic model organism Sinorhizobium meliloti and other nitrogen-fixing microbes. These structures and greater than 850 proteins purified by the NYSGRC prokaryotic expression platform contribute to the efforts of a consortium focusing on the systems biology of the symbiotic relationship between Sinorhizobium and alfalfa; other program participants include Allen Orville (Brookhaven National Laboratory); Michael Kahn and Svetlana Yurgel (Washington State University); Mary Lipton (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Haiping Cheng (Lehman College), and Sharon Long (Stanford University).

Brute force advances in large-scale fermentation and automated purification have also improved throughput and reduced costs (Figure 3). Notably, the LEX48 high-throughput bioreactor system (Harbinger Biotechnology) is an airlift fermenter that sparges air into the bottom of a stationary flask to achieve culture aeration/agitation. This system supports parallel production-scale growth of bacterial cultures (e.g. 48 one-liter or 24 two-liter glass bottles) with a modest laboratory footprint [15]. At the NYSGRC, a LEX48 systems support reproducible large-scale E. coli fermentation (total media volumes of up to 300 L/week) with routine yields of 20–40 mg of protein/2 L culture, and maximum protein yields exceeding 100 mg/2 L fermentation vessel. Alternatively, the GNF fermenter (GNF Systems) permits 96 parallel ~60 mL fermentations; each of which receives air/oxygen mixtures to achieve high cell densities (~30 OD units) and protein yields of up to 80 mg/ culture tube [16]. Following fermentation, the ÄKTA Xpress system from GE Lifesciences has emerged as the instrument of choice for automated, multistep protein purification of both single and multiplexed samples (up to 4 proteins/unit every 14 hours). The AKTA system routinely delivers high protein purity and homogeneity (>95%) without manual intervention (fully unattended purification runs are usually performed overnight). Modular design allows 12 such units to be controlled in parallel by a single personal computer, allowing purification of 48 samples every work day [4,10].

Figure 3.

NYSGRC Infrastructure: (a) LEX 48 airlift fermenter for parallel growth of E. coli cultures; (b) Caliper GXII 384-well capillary electrophoresis robot for rapid analysis of protein expression and small-scale purification; (c) Beckman FxP liquid handling robot for DNA and protein manipulation in multiwell plate format; (d) AKTA Xpress multistep purification instrument for automated protein purification; (e) custom built EPSON Scara-based Sonication robot for high-throughput cell lysis in multiwell plates or 50 mL tubes; (f) Perkin-Elmer Janus Cell::Explorer tissue culture robotics platform (from the point of view of the Guava FACS analyzer), showing the six axis robotic arm, the plate carousel, incubator space, and a Janus liquid Handler system (not labeled) all located within the BSL-2 bio-containment hood.

This integrated, cost effective prokaryotic expression platform has been responsible for considerable productivity at the NYSGRC. Over 11,000 protein-encoding constructs have been successfully cloned and small-scale expression tested, resulting in ~4000 expression validated constructs, >1700 purified protein targets, and 151 X-ray crystallographic structures in the past 24 months. Even more remarkable, this platform has been broadly successful, yielding structures from mechanistically diverse enzyme superfamilies [17], prokaryotic model systems such as the nitrogen-fixing organism Sinorhizobium meliloti (Figure 2), plus an extensive array of eukaryotic targets, encompassing constituents of large multicomponent assemblies involved in cell adhesive processes, nuclear pore function, and mammalian immunity (http://www.sbkb.org/kb/psi_centers.html). Importantly, these approaches are supporting large-scale efforts outside of the traditional structural genomics community. For example, the NYSGRC infrastructure also supports the Enzyme Function Initiative [18•], a large NIH-funded consortium focused on development and application of strategies for genome-scale annotation of enzyme function (http://enzymefunction.org/).

Eukaryotic expression systems

Despite myriad successes realized with prokaryotic expression systems, these approaches are not appropriate for all targets. Many eukaryotic proteins require post-translational modifications and/or chaperones to facilitate correct folding, which can only be provided by a eukaryotic expression system. Insect cells are well-established vehicles for recombinant protein expression; in particular, the baculovirus expression vector (BEV) systems are amenable to high-throughput protein expression, and many aspects of the BEV system can be automated. BEV systems rely on infection of lepidopteran cells, typically derived from either Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9/ Sf21) or Trichoplusia ni (High Five™), with recombinant baculovirus derived from Autographa californica multinuclear polyhedrovirus (AcMNPV). Although the utility of the BEV system was demonstrated nearly three decades ago [19], it remains an evolving technology, and recent developments in all many aspects of the system have greatly increased its utility.

The BEV system became significantly more accessible following groundbreaking work that reduced the necessity for plaque selection of recombinant virus [20]. Furthermore, deletion of several non-essential genes from the baculoviral genome yielded an expression system that gives far higher protein production levels by reducing both proteolysis and competition for cellular resources [21•]. Continued development efforts are aimed at increasing both the stability of the recombinant virus and target protein expression levels, and co-expression of multiple targets comprising obligate macromolecular complexes (Berger, in this issue).

During viral passage, the integrity of the expression cassette is often compromised. Viral genome stability can be increased using a bicistronic cassette bearing both the target protein-encoding DNA sequence and a selectable marker, which is used for positive selection of recombinant virus [22]. Moreover, incorporation of enhancer sequences within the promoter has yielded both increased viral stability [23] and increased target protein expression [24]. Finally, new cell lines, including Super SF9 (Oxford Expression Technologies) and BTI-Tnao38 [25] have been developed to further improve expression levels.

In a high-throughput setting, the relatively long time required for viral production and associated costs have militated against BEV system utilization. The absence of diagnostic small-scale expression screening entails dedication of considerable resources to generation of viruses that ultimately fail to deliver required expression levels. It was recently demonstrated, however, that expression constructs, at the transfer vector stage, can be screened via transient transfection in insect cells without amplification [26,27]. Thus, only those targets likely to result in actionable protein yields are allowed to proceed to large-scale viral production, thereby enhancing pipeline efficiency and reducing costs.

Post translational modifications supported by insect or mammalian cells can have a dramatic impact on production of material of sufficient quality for both structure/function studies and therapeutic uses [28,29••]. Of particular significance for structural studies is heterogeneity, resulting from incomplete modification at consensus glycosylation sites (e.g. variable glycosylation of recombinant IFN-γ [30]). Native glycan modification can also prove critical for expression of secreted proteins intended for functional characterization and/or use as biologics drugs [31,32]. Given current limitations, mammalian expression remains the method of choice for production of glycosoylated mammalian proteins [33]. Not surprisingly, extensive efforts are now being focused on introducing the mammalian glycosylation machinery into various heterologous expression systems [34], including E. coli [35•], yeast [36], insect cells [37], and plants [38,39]. In addition to affording the desired glycosylation, mammalian expression systems are also frequently used to address challenging targets that fail in insect cell systems. Typically, cell lines for mammalian cell production are derived from either CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) or HEK293 (human embryonic kidney, transformed with sheared adenovirus DNA) cell lines.

Conceptually, the simplest route for protein production in mammalian cells is transient transfection, which can be performed rapidly, is readily automated, and easily scalable [40]. An important elaboration on this basic approach uses HEK293-EBNA cell lines that express the Epstein Barr virus nuclear antigen, allowing for episomal replication of expression plasmids containing an Epstein–Barr origin of replication. This advance allows for plasmid amplification that results in higher levels of transient protein production by simply increasing target gene copy number [41].

In the context of a high-throughput structure discovery program, associated costs of commercial (cationic lipid) transfection reagents and large quantities of plasmid DNA required for large-scale transfection often prove prohibitive. Use of polyethyleminine (PEI) as a transfection reagent has significantly reduced transfection costs, while simultaneously simplifying the process [42]. The requirement for large amounts of plasmid DNA can be obviated with filler, non-plasmid DNA (e.g. herring sperm DNA) that maintains DNA concentration and transfection efficiency [43]. In a high-throughput setting, substantial costs associated with large quantities of media represent another practical limitation.

Generation of stable cell mammalian lines for recombinant protein production represents a tried and true approach. However, the time required for achieving stable generation has often precluded its use in high-throughput settings. Recent adoption of lentiviral vectors that reduce the time required to develop stable cell lines for protein expression promises to reduce this barrier [44,45•,46•]. The Daedalus system [45•], which has been implemented at the NYSGRC, uses an optimized lentiviral transfer plasmid that allows for high-level, long-term production of multi-milligram levels of proteins in only 2–3 weeks. The Daedalus system is being adapted to make it more suitable for use in a high-throughput platform. Significant improvements have been realized with viral production using the TubeSpin reactor system [47] in serum free media, which increases viral titer and eliminates the need for concentration before transduction, a major bottleneck in lentiviral-driven expression. Additional optimization efforts are focused on continued engineering of the lentiviral vector itself to increase the size of the payload and generation of robust inducible systems for membrane proteins and other cytotoxic expression targets [46•,48]. Important alternative considerations include establishment of platforms for high-efficiency generation of stable cell lines, such as recombination-mediated cassette exchange [49,50], rapid genomic amplification strategies [51,52], and cell lines with enhanced protein production characteristics (i.e. greater cell density and genomic stability) [53]. Full implementation of these improvements in a high-throughput environment has not yet been realized.

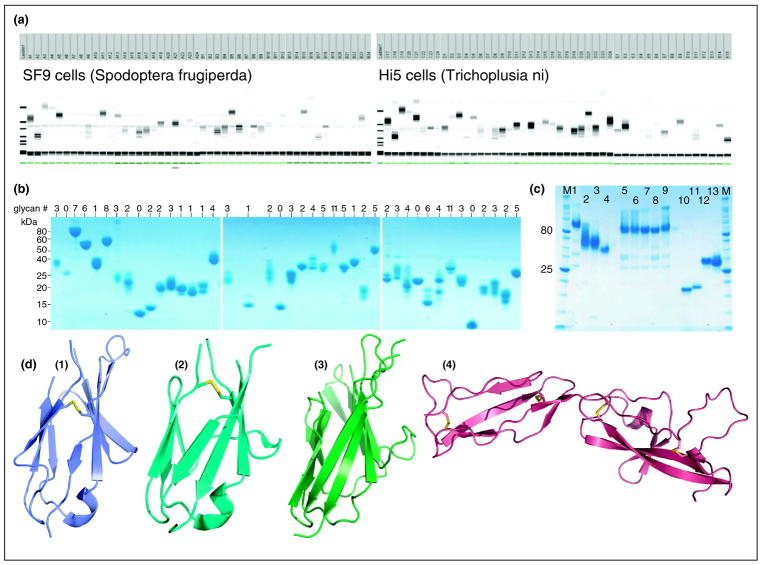

Both BEV-driven and lentiviral-driven expression platforms are central to the NYSGRC automated eukaryotic expression pipeline. Both platforms depend critically on a wide range of instrumentation and automation, including a customized Perkin Elmer Cell:Explorer system, arrayed around a 6-axis robotic arm housed in a BSL-2 enclosure (Figure 3). The system includes two incubators, allowing parallel insect and mammalian cell culture, 96-channel liquid handling capabilities, and two essential quality control instruments (multimode plate reader and a flow cytometer). Over the past year, >1700 baculovirus expression clones have been generated using the NYSGRC pipeline, encompassing more than 700 distinct protein targets (Figure 4). Notable successes include large-scale expression of high molecular-weight cell adhesion proteins (e.g. human Talin 1, vinculin, catenins and paxillin) and various members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (http://sbkb.org/tt/).

Figure 4.

High-throughput Eukaryotic Expression at the NYSGRC. (a) Automated small-scale expression testing of secreted targets (members of the immunoglobulin or Ig superfamily) in BEV-infected SF9 and Hi5 insect cells. (b) Example large-scale expression and purification of ~40 secreted proteins or ectodomains from the Ig Superfamily, generated using BEV and purified from supernatants of large scale (>2 L) insect cultures. Heterogeneity is due in part to variability of post-translational modifications, and, potentially proteolysis in the culture supernatant. The number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites (predicted using N-glycosite [65]) is indicated for each target. (c) Proteins recently purified from the NYSGRC mammalian stable cell line expression platform (Lentiviral-driven): (C1) human IgG1 fusion (Fc fusion) proteins of B7-1; (C2) murine Programmed cell Death Ligand 1, PDL-1; (C3) murine Programmed cell Death receptor 1, PD-1; (C4) murine B7-1; (C5-9) Fc fusions of wild type (C5) and mutant (C6-9) versions of PDL-1; (C10) erythroid membrane-associated protein, ERMAP; (C11) murine CD300 antigen like family member H, Cd300lh; (C12) Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor beta 1, PILRB; (C13) human voltage gated sodium channel type II beta. (d) Representative X-ray structures recently determined from proteins produced by the NYSGRC BEV platform: (1) Ig-C2 domain of human Fc-receptor like A, FCRLA (PDB ID 4HWN); (2) Ig-C2 type 1 domain from mouse Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2, FGFR2 (PDB ID 4HWU); (3) Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 15, CEACAM 15; and (4) beta 2 glycoprotein 1, B2GPI.

Other structural genomics centers are implementing high throughput eukaryotic expression pipelines. Courtesy of the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (GNF), the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG) has access to the highly automated Protein Expression and Purification Platform (PEPP), a fully automate robotic solution to high-throughput small-scale expression evaluation in eukaryotic cells [54]. The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) has established a somewhat less automated platform that enables throughputs of up to 250 L of baculovirus-infected insect cells/ month, supporting work on a host of challenging human targets, including tyrosine and serine/threonine kinases and integral membrane proteins (http://www.thesgc.org). These large-scale efforts are complemented by a broad array of technology development programs supported by both the NIH and international research funding agencies (e.g. see http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-13-032.html).

Future needs

A number of powerful protein expression technologies have been established and others continue to be developed. Of particular importance will be realization of methodologies that afford enhanced speed, increased efficiency, and superior economies for generating stably expressing mammalian cell lines. At present, several exciting approaches await implementation in high-throughput environments, including inducible viral and non-viral systems [46•,48], and approaches for facile recombination [49,50] into the host genome, and gene amplification for enhanced expression [51,52]. Such advances will further enhance the production of challenging proteins and macromolecular complexes, including integral membrane proteins and secreted proteins that may offer considerable therapeutic value. Sustained focus on post-translational modifications will be critical for many aspects of structural and mechanistic biology. Continued improvements in our ability to generate secreted proteins with native, homogeneous glycosylation patterns will remain an active area of research. New heterologous expression systems and improvements in expression/purification processes will be required to deliver proteins with the requisite biochemical, biophysical, and biological properties. Highlighted elsewhere in this issue (Berger, in this issue) are exciting new technologies that support expression and production of multicomponent assemblies for structural and functional analysis; these will become increasingly important for structural biology in general.

As technologies supporting structural genomics programs have matured, focus has shifted quite appropriately from an initial emphasis on well-behaved, single-domain, globular bacterial proteins of unknown structure/function to significantly more difficult problems in structural biology that address some of the grand biomedical research challenges. This paradigm shift demands that we go beyond the proven single target (albeit multiplexed, high-throughput, and relatively inexpensive) expression/purification platforms developed over the past decade. Moving forward, structural genomics pipelines will require tailoring to meet the demands of ever more challenging research programs.

It is imperative that we develop cost effective small-scale eukaryotic screening protocols, like those established for prokaryotic systems, to identify appropriate expression strategies before committing to costly and lengthy large-scale production efforts. Such considerations are particularly relevant for combinatorial co-expression of partners in stable heteromeric protein complexes. New multiplexing tools will be required if we are to prevail in mechanistic and structural studies of complicated biological machines, such as the large assemblies involved in cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix adhesive processes [55,56] or nuclear pore components that support nucleocytoplasmic transport [57]. Individual constituents of these assemblies frequently undergo posttranslational modification, consist of multiple globular domains interspersed with low complexity regions, and, require obligate (often unknown) binding partners for structural stability and function. Cell-surface receptor:ligand complexes controlling mammalian immunity [58] pose similar technical challenges. They are exquisitely sensitive to post-translational processing and almost invariably require one or more binding partners to stabilize native structure and support function.

Once the components of a large, stable multi-component complex are defined, emerging expression systems are proving effective for structural studies using cryo electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography [59,60]. A major bottleneck in structural biology remains high-confidence identification of transient interactions that often lie at the heart of complicated regulatory systems both within and outside cells. Going forward, we will be confronted with the classical ‘chicken and egg’ conundrum. If we cannot express a target protein without its partner(s) and we do not know which of the many putative partners to include in the mix, how can we make rapid progress? To take structural biology to the next level, we are committed to adapting the approaches we used to optimize multiple parameters for simpler systems (e.g. optimal choice of fusion partner, growth media, fermentation temperature, etc.) to the problem of sorting through manifold combinations of co-expression partners. At a minimum, definition of more labile macromolecular complexes for structural characterization will require extensive collaboration with quantitative and systems biologists [61], if we are to exploit fully results of large-scale interaction studies coming from yeast-two-hybrid, gene/protein complementation, mass spectrometry approaches, and ligand binding studies [62–64]. It will not be easy, but it must be done if we wish to avoid becoming prisoners of our (successful) reductionist past.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants U01GM094665, U54GM094662, U54GM093342, and P30CA013330.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Elsliger MA, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Wooley J, Wüthrich K, Wilson IA. The JCSG high-throughput structural biology pipeline. Acta Crystallogr Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:1137–1142. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110038212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, Babnigg G, Jedrzejczak R, Eschenfeldt WH, Li H, Maltseva N, Hatzos-Skintges C, Gu M, Makowska-Grzyska M, Wu R, et al. High-throughput protein purification and quality assessment for crystallization. Methods. 2011;55:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Love J, Mancia F, Shapiro L, Punta M, Rost B, Girvin M, Wang D-N, Zhou M, Hunt JF, Szyperski T, et al. The New York Consortium on Membrane Protein Structure (NYCOMPS): a high-throughput platform for structural genomics of integral membrane proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2010;11:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauder MJ, Rutter ME, Bain K, Rooney I, Gheyi T, Atwell S, Thompson DA, Emtage S, Burley SK. High throughput protein production and crystallization at NYSGXRC. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:561–575. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao R, Anderson S, Aramini J, Belote R, Buchwald WA, Ciccosanti C, Conover K, Everett JK, Hamilton K, Huang YJ, et al. The high-throughput protein sample production platform of the Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gräslund S, Nordlund P, Weigelt J, Hallberg BM, Bray J, Gileadi O, Knapp S, Oppermann U, Arrowsmith C, Hui R, et al. Protein production and purification. Nat Methods. 2008;5:135–146. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslanidis C, de Jong PJ. Ligation-independent cloning of PCR products (LIC-PCR) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6069–6074. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klock HE, Lesley SA. The Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito D, Garvey LA, Chakiath CS. Gateway cloning for protein expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:31–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhikhabhai R, Sjöberg A, Hedkvist L, Galin M, Liljedahl P, Frigård T, Pettersson N, Nilsson M, Sigrell-Simon JA, Markeland-Johansson C. Production of milligram quantities of affinity tagged-proteins using automated multistep chromatographic purification. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1080:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prater BD, Anumula KR, Hutchins JT. Automated sample preparation facilitated by PhyNexus MEA purification system for oligosaccharide mapping of glycoproteins. Anal Biochem. 2007;369:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincentelli R, Cimino A, Geerlof A, Kubo A, Satou Y, Cambillau C. High-throughput protein expression screening and purification in Escherichia coli. Methods. 2011;55:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pacheco B, Crombet L, Loppnau P, Cossar D. A screening strategy for heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli with the highest return of investment. Protein Expr Purif. 2012;81:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bird LE. High throughput construction and small scale expression screening of multi-tag vectors in Escherichia coli. Methods. 2011;55:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gräslund S, Sagemark J, Berglund H, Dahlgren L-G, Flores A, Hammarström M, Johansson I, Kotenyova T, Nilsson M, Nordlund P, et al. The use of systematic N- and C-terminal deletions to promote production and structural studies of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2008;58:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page R, Moy K, Sims EC, Velasquez J, McManus B, Grittini C, Clayton TL, Stevens RC. Scalable high-throughput micro-expression device for recombinant proteins. Biotechniques. 2004;37:364–370. doi: 10.2144/04373BM05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukk T, Sakai A, Kalyanaraman C, Brown SD, Imker HJ, Song L, Fedorov AA, Fedorov EV, Toro R, Hillerich B, et al. Homology models guide discovery of diverse enzyme specificities among dipeptide epimerases in the enolase superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4122–4127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Gerlt JA, Allen KN, Almo SC, Armstrong RN, Babbitt PC, Cronan JE, Dunaway-Mariano D, Imker HJ, Jacobson MP, Minor W, et al. The Enzyme Function Initiative. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9950–9962. doi: 10.1021/bi201312u. An outstanding example of the exploitation of structural genomics infrastructure and philosophy for large-scale functional annotation efforts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith GE, Summers MD, Fraser MJ. Production of human beta interferon in insect cells infected with a baculovirus expression vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:2156–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitchman RB, Possee RD, King LA. High-throughput baculovirus expression in insect cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;824:609–627. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-433-9_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Hitchman RB, Possee RD, Crombie AT, Chambers A, Ho K, Siaterli E, Lissina O, Sternard H, Novy R, Loomis K, et al. Genetic modification of a baculovirus vector for increased expression in insect cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2010;26:57–68. doi: 10.1007/s10565-009-9133-y. This paper shows recent evolution of the well-established BEV system, commercialized under the name flashBAC ULTRA from Oxford Expression Technologies and available for high-throughput pipelines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pijlman GP, Roode EC, Fan X, Roberts LO, Belsham GJ, Vlak JM, van Oers MM. Stabilized baculovirus vector expressing a heterologous gene and GP64 from a single bicistronic transcript. J Biotechnol. 2006;123:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari P, Saini S, Upmanyu S, Benjamin B, Tandon R, Saini KS, Sahdev S. Enhanced expression of recombinant proteins utilizing a modified baculovirus expression vector. Mol Biotechnol. 2010;46:80–89. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manohar SL, Kanamasa S, Nishina T, Kato T, Park EY. Enhanced gene expression in insect cells and silkworm larva by modified polyhedrin promoter using repeated Burst sequence and very late transcriptional factor-1. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:909–916. doi: 10.1002/bit.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto Y, Zhang S, Zhang S, Chen Y-R, Blissard GW. Correction: BTI-Tnao38; a new cell line derived from Trichoplusia ni, is permissive for AcMNPV infection and produces high levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2012;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loomis KH, Yaeger KW, Batenjany MM, Mehler MM, Grabski AC, Wong SC, Novy RE. InsectDirect System: rapid, high-level protein expression and purification from insect cells. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2005;6:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10969-005-5241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen X, Michel PO, Xie Q, Hacker DL, Wurm FM. Transient transfection of insect Sf-9 cells in TubeSpin® bioreactor 50 tubes. BMC Proc. 2011;5(Suppl 8):37. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S8-P37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbin K, Stieglmaier J, Saul D, Stieglmaier K, Stockmeyer B, Pfeiffer M, Lang P, Fey GH. Influence of variable N-glycosylation on the cytolytic potential of chimeric CD19 antibodies. J Immunother. 2006;29:122–133. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175684.28615.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Chang VT, Crispin M, Aricescu AR, Harvey DJ, Nettleship JE, Fennelly JA, Yu C, Boles KS, Evans EJ, Stuart DI, et al. Glycoprotein structural genomics: solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 2007;15:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011. A key publication addressing the challenges associated with glycosylated secreted mammalian proteins. This work demonstrates that in a mammalian expression system, combining the actions of a mannosidase inhibitor and Endoglycosidase H results in a uniformly deglycosylated protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedman RB, Jenkins N, James DC, Goldman MH, Hoare M, Oliver RWA, Green BN. Posttranslational processing of recombinant human interferon-γ in animal expression systems. Protein Sci. 1996;5:331–340. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossler P, Khattak SF, Li ZJ. Optimal and consistent protein glycosylation in mammalian cell culture. Glycobiology. 2009;19:936–949. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bork K, Horstkorte R, Weidemann W. Increasing the sialylation of therapeutic glycoproteins: the potential of the sialic acid biosynthetic pathway. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:3499–3508. doi: 10.1002/jps.21684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenkins N, Parekh RB, James DC. Getting the glycosylation right: implications for the biotechnology industry. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:975–981. doi: 10.1038/nbt0896-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loos A, Steinkellner H. IgG-Fc glycoengineering in non-mammalian expression hosts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;526:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Valderrama-Rincon JD, Fisher AC, Merritt JH, Fan Y-Y, Reading CA, Chhiba K, Heiss C, Azadi P, Aebi M, DeLisa MP. An engineered eukaryotic protein glycosylation pathway in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:434–436. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.921. This publication describes the design of a synthetic pathway to produce proteins in E. coli bearing eukaryotic N-linked glycosylation patterns, suggesting the potential for future adaptation of prokaryotic hosts for expression of mammalian glycoproteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang N, Liu L, Dumitru CD, Cummings NRH, Cukan M, Jiang Y, Li Y, Li F, Mitchell T, Mallem MR, et al. Glycoengineered Pichia produced anti-HER2 is comparable to trastuzumab in preclinical study. M Abs. 2011;3:289–298. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.3.15532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmberger D, Wilson IBH, Berger I, Grabherr R, Rendic D. SweetBac: a new approach for the production of mammalianised glycoproteins in insect cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Schähs M, Stiegler G, Quendler H, Mach L, Glössl J, Weterings K, Pabst M, Steinkellner H. Generation of glyco-engineered Nicotiana benthamiana for the production of monoclonal antibodies with a homogeneous human-like N-glycan structure. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:392–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castilho A, Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Grass J, Jez J, Gattinger P, Kunert R, Quendler H, Pabst M, Leonard R, et al. In planta protein sialylation through overexpression of the respective mammalian pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15923–15930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldi L, Hacker DL, Meerschman C, Wurm FM. Large-scale transfection of mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;801:13–26. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-352-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durocher Y, Perret S, Kamen A. High-level and high-throughput recombinant protein production by transient transfection of suspension-growing human 293-EBNA1 cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:E9. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raymond C, Tom R, Perret S, Moussouami P, L’abbé D, St-Laurent G, Durocher Y. A simplified polyethylenimine-mediated transfection process for large-scale and high-throughput applications. Methods. 2011;55:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiseljak D, Rajendra Y, Manoli SS, Baldi L, Hacker DL, Wurm FM. The use of filler DNA for improved transfection and reduced DNA needs in transient gene expression with CHO and HEK cells. BMC Proc. 2011;5(Suppl 8):33. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S8-P33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberbek A, Matasci M, Hacker DL, Wurm FM. Generation of stable, high-producing CHO cell lines by lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer in serum-free suspension culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:600–610. doi: 10.1002/bit.22968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45•.Bandaranayake AD, Correnti C, Ryu BY, Brault M, Strong RK, Rawlings DJ. Daedalus: a robust, turnkey platform for rapid production of decigram quantities of active recombinant proteins in human cell lines using novel lentiviral vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr706. This paper describes an advanced lentiviral-mediated expression platform that is readily amenable to high-throughput environments. The vector is optimized to reduce gene silencing, allowing long-term expression of target protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46•.Gaillet B, Gilbert R, Broussau S, Pilotte A, Malenfant F, Mullick A, Garnier A, Massie B. High-level recombinant protein production in CHO cells using lentiviral vectors and the cumate gene-switch. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:203–215. doi: 10.1002/bit.22698. In this work, a lentiviral-driven expression system is described that utilizes an inducible promoter, resulting in high levels of recombinant protein expression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Jesus MJ, Girard P, Bourgeois M, Baumgartner G, Jacko B, Amstutz H, Wurm FM. TubeSpin satellites: a fast track approach for process development with animal cells using shaking technology. Biochem Eng J. 2004;17:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weber W, Fussenegger M. Inducible product gene expression technology tailored to bioprocess engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiao J, Oumard A, Wegloehner W, Bode J. Novel tag-and-exchange (RMCE) strategies generate master cell clones with predictable and stable transgene expression properties. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:579–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou H, Liu Z-G, Sun Z-W, Huang Y, Yu W-Y. Generation of stable cell lines by site-specific integration of transgenes into engineered Chinese hamster ovary strains using an FLP-FRT system. J Biotechnol. 2010;147:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kingston RE, Kaufman RJ, Bebbington CR, Rolfe MR. Amplification using CHO cell expression vectors. Curr Protocols Mol Biol. 2002:16.23.1–16.23.13. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1623s60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnes LM, Bentley CM, Dickson AJ. Advances in animal cell recombinant protein production: GS-NS0 expression system. Cytotechnology. 2000;32:109–123. doi: 10.1023/A:1008170710003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim WH, Kim MS, Kim YG, Lee GM. Development of apoptosis-resistant CHO cell line expressing PyLT for the enhancement of transient antibody production. Process Biochem. 2012;47:2557–2561. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalez R, Jennings LL, Knuth M, Orth AP, Klock HE, Ou W, Feuerhelm J, Hull MV, Koesema E, Wang Y, et al. Screening the mammalian extracellular proteome for regulators of embryonic human stem cell pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3552–3557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914019107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shapiro L, Weis WI. Structure and biochemistry of cadherins and catenins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a003053. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye F, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. Molecular mechanism of inside-out integrin regulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez-Martinez J, Rout MP. A jumbo problem: mapping the structure and functions of the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chattopadhyay K, Lazar-Molnar E, Yan Q, Rubinstein R, Zhan C, Vigdorovich V, Ramagopal UA, Bonanno J, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. Sequence, structure, function, immunity: structural genomics of costimulation. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:356–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trowitzsch S, Bieniossek C, Nie Y, Garzoni F, Berger I. New baculovirus expression tools for recombinant protein complex production. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bieniossek C, Papai G, Schaffitzel C, Garzoni F, Chaillet M, Scheer E, Papadopoulos P, Tora L, Schultz P, Berger I. The architecture of human general transcription factor TFIID core complex. Nature. 2013;493:699–702. doi: 10.1038/nature11791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fraser JS, Gross JD, Krogan NJ. From systems to structure: bridging networks and mechanism. Mol Cell. 2013;49:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neveu G, Cassonnet P, Vidalain P-O, Rolloy C, Mendoza J, Jones L, Tangy F, Muller M, Demeret C, Tafforeau L, et al. Comparative analysis of virus–host interactomes with a mammalian high-throughput protein complementation assay based on Gaussia princeps luciferase. Methods. 2012;58:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jäger S, Cimermancic P, Gulbahce N, Johnson JR, McGovern KE, Clarke SC, Shales M, Mercenne G, Pache L, Li K, et al. Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature. 2012;481:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li X, Gianoulis TA, Yip KY, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Extensive in vivo metabolite–protein interactions revealed by large-scale systematic analyses. Cell. 2010;143:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang M, Gaschen B, Blay W, Foley B, Haigwood N, Kuiken C, Korber B. Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology. 2004;14:1229–1246. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]