Barbey et al. investigate the neurobiology of social problem solving and its relation to psychometric intelligence, emotional intelligence, and personality in 144 patients with focal lesions. Results reveal the neural architecture of social problem solving and provide an integrative framework for understanding the social, psychometric, and emotional foundations of human intelligence.

Keywords: social intelligence, latent variable modelling, voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping

Abstract

Accumulating neuroscience evidence indicates that human intelligence is supported by a distributed network of frontal and parietal regions that enable complex, goal-directed behaviour. However, the contributions of this network to social aspects of intellectual function remain to be well characterized. Here, we report a human lesion study (n = 144) that investigates the neural bases of social problem solving (measured by the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory) and examine the degree to which individual differences in performance are predicted by a broad spectrum of psychological variables, including psychometric intelligence (measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale), emotional intelligence (measured by the Mayer, Salovey, Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test), and personality traits (measured by the Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Personality Inventory). Scores for each variable were obtained, followed by voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping. Stepwise regression analyses revealed that working memory, processing speed, and emotional intelligence predict individual differences in everyday problem solving. A targeted analysis of specific everyday problem solving domains (involving friends, home management, consumerism, work, information management, and family) revealed psychological variables that selectively contribute to each. Lesion mapping results indicated that social problem solving, psychometric intelligence, and emotional intelligence are supported by a shared network of frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, including white matter association tracts that bind these areas into a coordinated system. The results support an integrative framework for understanding social intelligence and make specific recommendations for the application of the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory to the study of social problem solving in health and disease.

Introduction

Social problem solving refers to mental processes and strategies for making decisions and solving problems encountered in everyday social life (Cornelius and Caspi, 1987; Dimitrov et al., 1996). This ecological approach to studying problem solving considers the ways in which an individual perceives and structures the problem situation, with a focus on social, emotional, and contextual factors (Diehl et al., 1995; Marsiske and Willis, 1995; Blanchard-Fields et al., 1997; Burton et al., 2006; Thornton et al., 2007; Artistico et al., 2010; Mienaltowski, 2011). According to this approach, the ability to solve a problem is influenced by: (i) whether or not the problem reflects situations encountered in daily life; (ii) the extent to which the problem is personally meaningful or emotionally salient to the individual; (iii) how the individual incorporates social and emotional information to guide thought and drive effective behaviour; and (iv) how adaptive a specific solution is given the individuals goals and context of living.

In recent years neuropsychology has placed increasing importance on broadening the scope of standard cognitive assessments to incorporate social and emotional aspects of intellectual function (Barbey et al., 2009, 2011, 2014a; Kennedy and Adolphs, 2011; Adolphs and Anderson, 2013). In particular, emerging neuroscience evidence indicates that social problem solving may rely upon executive control functions for the regulation and control of behaviour (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Barbey et al., 2012) and recruit brain regions that are specifically oriented toward the resolution of conflict within social and emotional contexts (Sternberg, 2000; Whitfield and Wiggins, 2003; Channon, 2004; Barbey et al., 2014a). Indeed, the ability to interact and communicate effectively in everyday social settings is frequently disrupted by traumatic brain injury and this poses fundamental difficulties for successful rehabilitation (Warschausky et al., 1997; Janusz et al., 2002; Ganesalingam et al., 2007; Hanten et al., 2008, 2011; Muscara et al., 2008; Robertson and Knight, 2008).

A network of neural correlates has been linked to social and emotional processing using a range of experimental materials, such as interpersonal scenarios, cartoons, jokes, faux pas, and moral and ethical dilemmas (Adolphs, 2003a, b, 2010; Kennedy and Adolphs, 2011). Social cognitive neuroscience research indicates that the medial prefrontal cortex plays a key role in the representation of mental states, both for an individual’s own thoughts and beliefs and those of others (Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003); the right posterior superior temporal sulcus mediates the analysis of biological motion or agency, facilitating the interpretation of purposeful movements (Mar et al., 2007); the left temporal pole is involved in storing relevant social knowledge, which contributes to the contextual understanding of others’ social interactions (Simmons and Martin, 2009; Simmons et al., 2010); and the orbitofrontal-amygdala regions are involved in emotional aspects of processing (Frith and Frith, 2003; Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Sabbagh, 2004; Saxe, 2006).

Neuropsychological patients with focal brain lesions provide a valuable opportunity to study the neural mechanisms of social problem solving, supporting the investigation of lesion-deficit associations that elucidate the contribution of specific brain structures. Although the neural foundations of social problem solving remain to be directly assessed using lesion methods, the broader neuropsychological patient literature has provided significant insight into the neural bases of social and emotional aspects of intellectual function (Rowe et al., 2001; Stuss et al., 2001; Gregory et al., 2002; Abu-Akel, 2003; Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Apperly et al., 2004; Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2003, 2005; Channon et al., 2007). For example, a recent lesion mapping study of emotional intelligence (Barbey et al., 2014a) indicates that the capacity to engage in sophisticated information processing about emotions and to use this information to guide thought and behaviour is supported by a broadly distributed network of frontal, temporal, and parietal regions that have been widely implicated in social cognition (Saxe, 2006). However, the contributions of this network to everyday social problem solving remain to be well characterized. Outstanding questions about the social and emotional nature of everyday problem solving centre on advancing our knowledge of its psychological and neural foundations—investigating how selective damage to specific brain systems impacts performance on everyday problem solving and is related to a host of executive, social, and emotional processes.

Motivated by these considerations, we studied social problem solving by administering the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory (EPSI; Cornelius and Caspi, 1987) to a large sample of patients with focal brain injuries (n = 144). We investigated how social problem solving relates to a broad spectrum of psychological variables, including psychometric intelligence [Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS (Wechsler, 1997)]; emotional intelligence [Mayer, Salovey, Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2008)], and personality traits [Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory, NEO-PI (Costa and McCrae, 2000)]. Our goal was to conduct a comprehensive assessment of social problem solving that examined the contributions of executive, social and emotional information processing abilities, and personality traits. Indeed, the role of personality traits, such as extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness, in predicting an individual’s ability to manage and resolve conflict in social problem solving contexts remains to be explored.

We applied: (i) confirmatory factor analysis to obtain latent scores of psychometric and emotional intelligence; and (ii) exploratory factor analysis to compute a general everyday problem solving index (EPSI). Standardized scores were considered for the EPSI facets and the personality traits. The scores were submitted to voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping. We investigated: (i) the degree to which individual differences in social problem solving are predicted by general intelligence (measured by the WAIS), emotional intelligence (measured by the MSCEIT), and personality traits (measured by the NEO-PI); and (ii) whether social problem solving engages cortical networks for executive, social, and emotional functions. We hypothesized that social problem solving would recruit neural systems for executive, social, and emotional functions, reflecting a reliance upon mechanisms for the regulation and control of social behaviour.

Materials and methods

Participants

The Vietnam Head Injury Study (VHIS) was set up by William F. Caveness, chief of the Laboratory of Experimental Neurology at the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke from 1965. He designed the VHIS registry, which gathered information on 1221 Vietnam veterans who sustained a traumatic brain injury between 1967 and 1970 (Caveness, 1979). The Vietnam conflict was the first that involved large-scale helicopter evacuations and early treatment by neurosurgical teams close to the battlefield, so that most patients received definitive treatment within hours of their injuries, allowing a much higher rate of survival than in previous conflicts (Rish et al., 1981; Carey et al., 1982). In addition, the low velocity penetrating fragment wounds typically sustained resulted in relatively focal defects, and so these subjects provided a particularly large and informative group for study. Participants were drawn from the Phase 3 VHIS registry, which includes American male veterans who suffered brain damage from penetrating head injuries in the Vietnam War (n = 144). This study was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board and, in accordance with stated guidelines, all subjects read and signed informed consent documents. As our participants have had an injury that may have impaired their ability to think clearly and make decisions, we ask that they travel with a primary caregiver and name them as a Durable Power of Attorney for research and medical care at NIH.

Phase 3 testing occurred between April 2003 and November 2006. Demographic and background data for the VHIS are reported in Supplementary Table 1 (Koenigs et al., 2009; Raymont et al., 2010; Barbey et al., 2011, 2012, 2013a, b, 2014b). We observed a significant correlation between years of education and performance on the EPSI (overall), WAIS-III (g), and MSCEIT (overall emotional intelligence score) (ranging from 0.3 to 0.5), consistent with the psychometric literature demonstrating a relationship between education and mental ability (Jensen, 1998). Importantly, however, the pattern of findings obtained from our study remains the same when controlling for years of education, as described below and illustrated in Supplementary Table 5.

Lesion analysis

CT data were acquired during the Phase 3 testing period. Axial CT scans without contrast were acquired at Bethesda Naval Hospital on a GE Medical Systems Light Speed Plus CT scanner in helical mode (150 slices per subject, field of view covering head only). Images were reconstructed with an in-plane voxel size of 0.4 × 0.4 mm, overlapping slice thickness of 2.5 mm, and a 1 mm slice interval. All non-brain tissue seen in the subject’s CT scan was automatically removed (skull-stripped) in order to improve the accuracy of spatial normalization to a CT template brain in MNI space. The spatial normalization was achieved by using the AIR 3.08 algorithm using a 12-parameter affine transformation. Lesion location and volume were determined from CT images using the Analysis of Brain Lesion software (ABLe) (Makale et al., 2002; Solomon et al., 2007) contained in MEDx v3.44 (Medical Numerics) with enhancements to support the Automated Anatomical Labelling atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). Within ABLe, the lesions were drawn manually in native space on each 1-mm thick slice by a neuropsychiatrist with clinical experience reading CT scans and reviewed by our team of cognitive neuroscientists, enabling a consensus decision to be reached regarding the limits of each lesion. For each subject, a lesion mask image in MNI space was saved for voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping (Bates et al., 2003). Although the original scans were acquired with the CT modality, voxel-based lesion symptom mapping results are overlaid on magnetic resonance images in MNI space for better visualization of brain structures. Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping applies a t-test to compare, for each voxel, scores from patients with a lesion at that voxel contrasted against those without a lesion at that voxel. The reported findings were thresholded using a false discovery rate (FDR) correction of q < 0.05. To ensure sufficient statistical power for detecting a lesion-deficit correlation, our analysis only included voxels for which four or more patients had a lesion. The lesion overlap map for the entire VHIS patient sample is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. It is important to emphasize that the conclusions drawn from the VHIS sample are restricted to the voxel space identified in Supplementary Fig. 1, which provides broad coverage of the cerebral hemispheres but does not include subcortical brain structures.

Psychological measures

We administered the EPSI (Cornelius and Caspi, 1987), WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997) MSCEIT (Mayer, 2004; Mayer et al., 2008), and the NEO-PI (Costa and McCrae, 2000). We applied latent variable modelling (Loehlin, 2004) to derive factor scores for psychometric and emotional intelligence, as reported by Barbey and colleagues (2014a). We also obtained factor scores for the EPSI. Personality traits were measured by the NEO-PI (including extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience), but treated separately from the psychometric intelligence measures. Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the employed measures of psychometric and emotional intelligence (for further detail concerning their standardization, reliability and validity, see Cornelius and Caspi, 1987; Wechsler, 1997; Mayer et al., 2008) along with the measured personality traits.

Barbey et al. (2014a) analysed the WAIS-III and the MSCEIT battery at the latent variable level (Loehlin, 2004). The tested measurement model defined emotional intelligence applying the MSCEIT battery, whereas verbal comprehension, perceptual organization/fluid intelligence, working memory, and processing speed defined psychometric intelligence. This model produced appropriate fit indices and all correlations among factors were statistically significant. Barbey et al. (2014a) applied the imputation function of the AMOS program (Arbuckle, 2006) to obtain latent scores for these factors.

The EPSI scores for the six facets comprised by this battery were submitted to an exploratory factor analysis to uncover the factor structure underlying everyday problem solving. A principal factor analysis was computed (Fabrigar, 1999). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was high (0.84) and the Bartlett test produced proper values (χ2 = 318.6, df = 15, P = 0.000). One single factor was obtained (eigenvalue = 3.33, % of variance = 55.5) with factor loadings ranging from 0.54 (family conflict resolution) to 0.78 (friend conflict resolution). The factor score for the EPSI battery was obtained using the regression method from the data reduction menu comprised in the SPSS package (SPSS, 2013). These scores were standardized for clarity purposes [mean = 100, standard deviation (SD) = 15]. Finally, the NEO-PI-R scores were also submitted to regression and lesion analyses.

Everyday Problem Solving Inventory

The EPSI is comprised of 48 hypothetical problem situations that represent six content domains (i) friend conflict resolution; (ii) home management; (iii) consumerism; (iv) work conflict resolution; (v) information management; and (vi) family conflict resolution (Cornelius and Caspi, 1987). For each problem situation, four possible responses were provided to participants. These responses were designed to represent four coping styles: (i) problem focused action; (ii) cognitive problem analysis; (iii) passive-dependent behaviour; and (iv) avoidant thinking and denial. Participants were instructed to imagine that they were in the described situations and were asked to rate the effectiveness of each solution in each of the four response modes provided for each situation. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘extremely ineffective/poor solution’ and 5 = ‘extremely effective solution’). Participants rated each possible response, producing four ratings for each problem situation. In this study, the EPSl was scored according to the procedure outlined by Cornelius and Caspi (1987): participant responses were correlated with judges’ ratings of the effectiveness of each problem solution (Cornelius and Caspi; 1987). Participants’ scores represented the degree to which their response patterns approximated optimal response patterns that were identified by judges. Separate scores were obtained for each problem domain as well as for the total measure. The psychometric properties of the EPSI have been well characterized by prior research (Marsiske and Willis, 1995), which supports the validity and reliability of this instrument as a measure of social problem solving (i.e. mental operations for the management and resolution of conflict within each social problem solving domain).

Relationships among scores

Social problem solving was assessed by the EPSI, and verbal comprehension was assessed by the vocabulary, similarities, information and comprehension subtests from the WAIS-III. Perceptual organization/fluid intelligence was measured by block design, matrix reasoning, picture completion, picture arrangement, and object assembly subtests from the WAIS-III. Working memory comprised measures of arithmetic, digit span, and letter-number sequencing from the WAIS-III, and processing speed was assessed by digit symbol coding and symbol search subtests from the WAIS-III. Emotional intelligence was measured by the full MSCEIT battery, including the faces, pictures, sensations, facilitation, blends, changes, emotional, and social subtests. Supplementary Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for each of the administered tests. Supplementary Table 4 presents the correlation matrix for the scores submitted to lesion analysis. The scores of interest were: EPSI factor score, EPSI facets, WAIS-III factor scores (verbal comprehension, perceptual organization/fluid intelligence, working memory, processing speed), MSCEIT/Emotional Intelligence general factor score, and NEO-PI-R traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness). It is noteworthy that a positive manifold is clear, as evidenced by substantial correlations among scores derived from the cognitive measures (ranging from 0.48 to 0.54). Note also that the observed pattern of correlations were remarkably similar when education was controlled for (Supplementary Table 5).

Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping

The obtained scores were correlated to regional grey and white matter determined by voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping (Bates et al., 2003). This method compares, for every voxel, scores from patients with a lesion at that voxel contrasted against those without a lesion at that voxel (applying a false discovery rate correction of q < 0.05). Unlike functional neuroimaging studies, which rely on the metabolic demands of grey matter and provide a correlational association between brain regions and cognitive processes, voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping can identify regions playing a causal role over the constructs of interest by mapping where damage can interfere with performance (Gläscher et al., 2010; Woolgar et al., 2010; Barbey et al., 2012, 2014a, c).

Results

Stepwise regression analyses

Scores for psychometric intelligence (verbal comprehension, perceptual organization/fluid intelligence, working memory, and processing speed) and emotional intelligence (MSCEIT general factor score) along with the five personality traits were submitted to a forward stepwise regression analysis where EPSI scores were the dependent measures. The SPSS program was used for this latter analysis and it provides the variables predicting the dependent measure once their own correlations are taken into account (SPSS, 2013). The analyses were computed for the total EPSI scores as well as for the six everyday problem solving domains (friend conflict resolution, home management, consumerism, work conflict resolution, information management, and family conflict resolution). Results indicated that the EPSI total score was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.36, P < 0.001) by working memory (Beta = 0.24, t = 2.47, P = 0.015), processing speed (Beta = 0.21, t = 2.40, P = 0.018), and emotional intelligence (Beta = 0.27, t = 3.1, P = 0.002). In addition, each everyday problem solving domain relied upon specific social and intellectual functions. In particular, (i) friend conflict resolution was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.27, P < 0.001) by working memory (Beta = 0.31, t = 3.3, P = 0.001), processing speed (Beta = 0.21, t = 2.3, P = 0.02) and openness (Beta = 0.19, t = 2.6, P = 0.01); (ii) home management was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.17, P < 0.001) by verbal comprehension (Beta = 0.18, t = 2.1, P = 0.04) and processing speed (Beta = 0.32, t = 3.7, P = 0.00); (iii) consumerism was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.16, P < 0.001) by perceptual organization/fluid intelligence (Beta = 0.24, t = 2.6, P = 0.01) and emotional intelligence (Beta = 0.22, t = 2.4, P = 0.02); (iv) work conflict resolution was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.24, P < 0.001) by verbal comprehension (Beta = 0.27, t = 2.5, P = 0.01) and working memory (Beta = 0.27, t = 2.4, P = 0.01); (v) information management was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.23, P < 0.001) by working memory (Beta = 0.20, t = 1.8, P = 0.06), processing speed (Beta = 0.20, t = 2.0, P = 0.04), and emotional intelligence (Beta = 0.19, t = 2.0, P = 0.04); and (vi) family conflict resolution was predicted (adjusted R2 = 0.18, P < 0.001) by emotional intelligence (Beta = 0.42, t = 5.5, P = 0.00) and extraversion (Beta = 0.17, t = 2.2, P = 0.03). Because, as noted above, education correlated with the EPS scale, the WAIS factors, and the MSCEIT, we ran regression analyses including the education variable as a further predictor. The results revealed that education was never relevant for predicting the EPSI scores. The same predictors were observed for the EPSI factor score, friends, home, consumerism, and family. For work, the predictors were working memory and emotional intelligence (verbal comprehension is no longer a predictor), and for information management the predictors were working memory and processing speed (emotional intelligence was no longer a predictor). Taken together, these findings indicate that everyday problem solving is associated with key competencies for psychometric intelligence (working memory and processing speed) and emotional intelligence, and suggest that specific everyday problem solving domains rely upon facets of psychometric intelligence (i.e. home management and work conflict resolution), emotional intelligence (i.e. family conflict resolution), or competencies for both (i.e. friend conflict resolution, information management, and consumerism). In addition, the results indicate that personality traits (openness and extraversion) reliably predict friend and family conflict resolution.

Lesion mapping of social problem solving

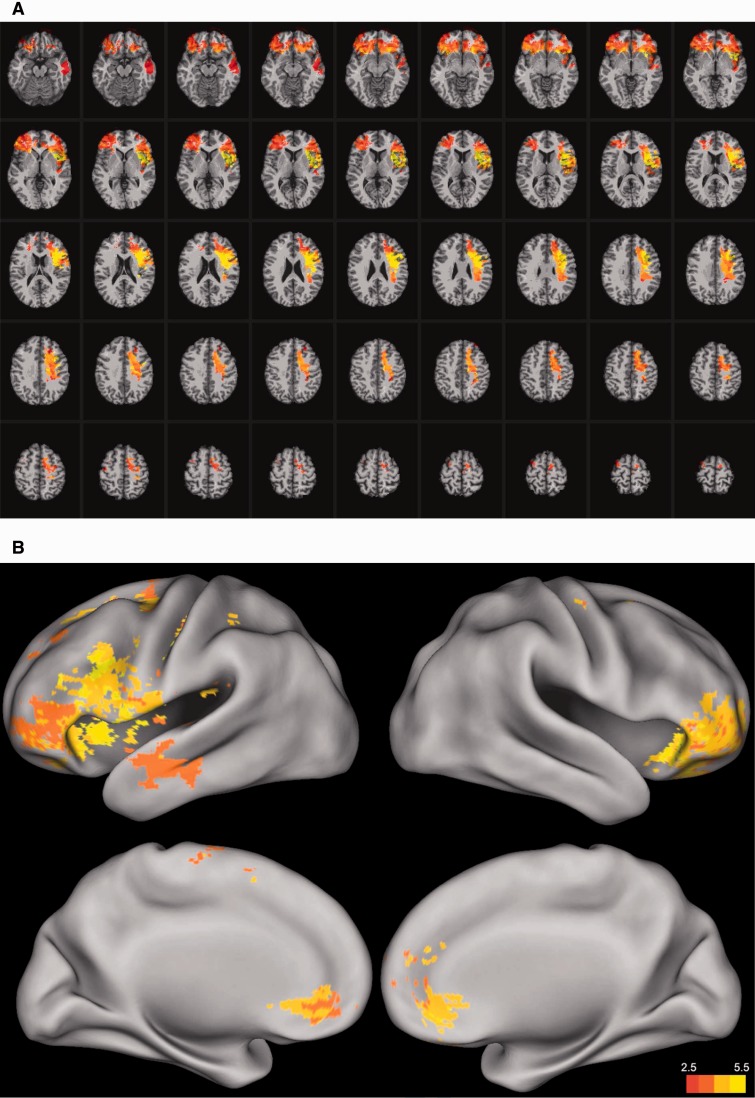

We applied voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping to elucidate the neural mechanisms of social problem solving, identifying a broadly distributed network of brain regions primarily within the left hemisphere (Fig. 1A and B, Supplementary Table 6). Significant effects encompassed locations for: (i) language processing (e.g. Broca’s area and left superior temporal gyrus); (ii) spatial processing (e.g. left inferior and superior parietal cortex); (iii) motor processing (e.g. left somatosensory and primary motor cortex); (iv) working memory (e.g. left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, left inferior and superior parietal cortex, and left superior temporal gyrus); (v) social and emotional information processing (e.g. orbitofrontal cortex, left temporal pole), in addition to expected locations of major white matter fibre tracts; including (vi) the anterior and dorsal bundle of the superior longitudinal/arcuate fasciculus connecting temporal, parietal, and inferior frontal regions; (vii) the superior fronto-occipital fasciculus connecting dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the frontal pole with the superior parietal lobule; and (viii) the uncinate fasciculus, which connects anterior temporal cortex and amygdala with orbitofrontal and frontopolar regions. Taken together, these results suggest that social problem solving reflects the ability to effectively integrate executive, social, and emotional processes via a circumscribed set of cortical connections primarily within the left hemisphere.

Figure 1.

Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping of everyday problem solving (factor score) (n = 144). The statistical map is thresholded at 5% false discovery rate. (A) In each axial slice, the right hemisphere is on the reader's left. (B) In each inflated map of the cortical surface, the right hemisphere is on the reader's right.

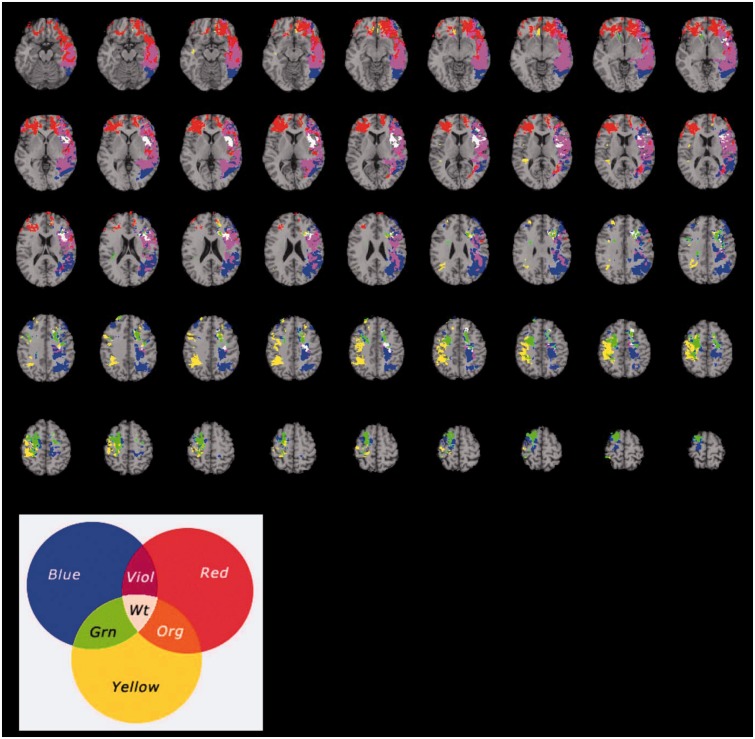

We further investigated whether the observed neural system shared anatomical substrates with reliable predictors of social problem solving; namely, working memory, processing speed, and emotional intelligence (Fig. 2). A lesion overlap map illustrating the common brain regions identified by each of the voxel-based lesion–symptom analyses of working memory, processing speed, and emotional intelligence indicates that these competencies shared regions primarily within the left insula (Fig. 2; regions highlighted in white). The left insula functions as an integral hub for mediating dynamic interactions between large-scale brain networks involved in externally oriented attention (e.g. executive control) and internally oriented or self-regulated cognition (e.g. social and emotional information processing) (Menon and Uddin, 2010; Jezzini et al., 2012; Simmons et al., 2013). For example, Bushara and colleagues (2001) investigated temporal asynchrony in a ventriloquist task and found insula activation to be important, suggesting that this type of ‘social synchrony’ arises early in life and is supported by the insula. In summary, the findings provide additional precision for characterizing the psychological and neural foundations of social problem solving, indicating that the left insula represents a key element of the underlying information processing architecture.

Figure 2.

Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping of the reliable predictors of everyday problem solving (factor score): working memory (blue); processing speed (yellow); and emotional intelligence (red) (n = 144). Each statistical map is thresholded at 5% false discovery rate. In each axial slice, the right hemisphere is on the reader's left. Viol = violet; Org = orange; Grn = green; Wt = white.

We additionally investigated the neural bases of personality traits that were predictive of social problem solving, including openness to experience and extraversion. However, these personality traits did not reveal reliable patterns of brain damage in our sample.

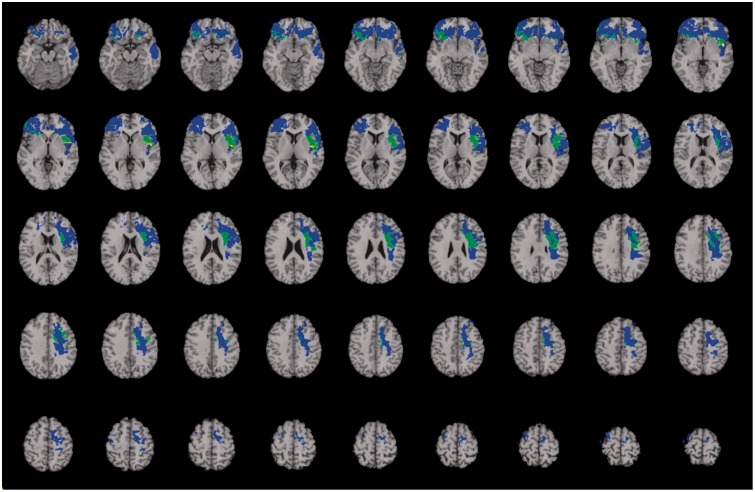

Lesion mapping of residual social problem solving scores

We analysed the social problem solving residual scores removing variance shared with its significant predictors. Impairment in the social problem solving residual score was associated with selective damage to frontal and parietal brain structures that have been widely implicated in executive (Miller and Cohen, 2001) and social function (Barbey et al., 2014a; Ochsner and Lieberman, 2001; Ochsner, 2004). These regions comprised bilateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 10), left insula, in addition to major white matter fibre tracts, including the superior longitudinal/arcuate fasciculus and the superior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Fig. 3). The observed findings indicate that everyday social problem solving emerges from the coordination of executive, social, and emotional processes.

Figure 3.

Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping of the reliable predictors of everyday problem solving for the original and residual factors (n = 144). Lesion overlap map illustrating common and distinctive brain regions for everyday problem solving (blue) and everyday problem solving residual (yellow). Overlap between these conditions is illustrated in green. The statistical map is thresholded at 5% false discovery rate. In each axial slice, the right hemisphere is on the reader's left.

Discussion

We investigated the neural bases of social problem solving in a large sample of patients with focal brain injuries (n = 144) and systematically examined its relationship with a broad spectrum of psychological variables, including psychometric intelligence (verbal comprehension, perceptual organization/fluid intelligence, working memory, and processing speed), emotional intelligence (MSCEIT general factor score), and personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience). The analysis of psychometric, social, and emotional factors was motivated by the hypothesis that social problem solving would engage neural systems for the regulation and control of social and affective behavior. The computed regression analyses revealed that working memory, processing speed, and emotional intelligence reliably predict the general score on the EPSI inventory. This finding indicates that executive and social functions predict individual differences in everyday problem solving. We also analysed the six scales included in the EPSI, namely, friend conflict resolution, home management, consumerism, work conflict resolution, information management, and family conflict resolution, using the same regression approach. The results indicate that specific everyday problem solving domains rely upon facets of psychometric intelligence (i.e. home management and work conflict resolution), emotional intelligence (i.e. family conflict resolution), or competencies for both (i.e. friend conflict resolution, information management, and consumerism). The observed findings indicate that the relationships between these measures, and their neurobiological underpinnings, have complex interdependencies.

In addition, our analysis of personality traits and social problem solving indicates that openness to experience and extraversion reliably predict conflict resolution involving friends and family. Individuals high in openness to experience are motivated to seek new social experiences and to engage in self-examination (DeYoung et al., 2014), which together may serve to promote effective problem solving with friends and family. Furthermore, extraversion is a personality trait that is characterized by high energy, enthusiasm, and assertiveness (Quilty et al., 2014), and is known to promote social engagement, which may facilitate social problem solving among friends and family.

Lesion mapping of social problem solving

Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping for social problem solving and its reliable predictors revealed that both engage a shared network of frontal, temporal, and parietal regions. To develop a rigorous and quantitative approach for studying social problem solving, we related scores derived from the EPSI inventory with several psychometric and socio-emotional measures. We observed a significant effect on social problem solving with lesions in a distributed network of frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, including white matter association tracts, binding these areas into a coordinated system (Fig. 1A and B, Supplementary Table 6).

The neural substrates of social problem solving were relatively circumscribed, concentrated in the core of white matter, and comprising a narrow subset of regions associated with performance on WAIS-III factors (Fig. 1A and B). The largest overlap between the WAIS-III and social problem solving was found for working memory and emotional intelligence (Table 1). These factors assess operations for adaptive behaviour and social problem solving, and are associated with a distributed fronto-parietal network (Barbey et al., 2012, 2014a). This pattern of findings suggests that social problem solving engages key competencies for psychometric intelligence (e.g., working memory and processing speed) and that the communication between areas associated with these competencies is of critical importance.

Table 1.

Spatial overlap between lesion mapping results for EPSI and Working Memory, Processing Speed, and Emotional Intelligence (IQ)

| Thresholded (Dice coefficient) | ||

|---|---|---|

| EPSI with | Emotional IQ | 0.49 |

| Working memory | 0.48 | |

| Processing speed | 0.22 |

Overlap statistics were computed using the Dice coefficient (FDR q = 0.05). The Dice coefficient has been used in functional MRI analyses to measure the degree of similarity between superthreshold cluster maps (Rombouts et al., 1997; Bennett and Miller, 2010). Specifically, thresholded maps were binarized (i.e. where the value ‘1’ indicates a super-threshold voxel) and masked to include only those voxels inside the standardized brain volume. Similarity between maps was calculated with the following formula: , where Vi is the masked, thresholded binary map corresponding to group-map i. This formula is equivalent to calculating the number of overlapping (or shared) superthreshold voxels, divided by the average total superthreshold voxels of the images. The Dice coefficient is easy to interpret because the maximum value of 1 indicates perfect similarity whereas the minimum value of 0 indicates no similarity.

Lesion mapping of social problem solving residual scores

We further investigated the neural basis of social problem solving while removing the variance shared with its significant predictors. This analysis revealed selective damage to frontal and parietal brain structures that have been widely implicated in executive (Barbey et al., 2014c) and social function (Ochsner and Lieberman, 2001; Ochsner, 2004). These regions comprised bilateral orbitofrontal cortex (Brodmann area 10), left insula, in addition to major white matter fiber tracts, including the superior longitudinal/arcuate fasciculus and the superior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Fig. 3).

A distributed neural system for social intelligence

The observed findings contribute to neuropsychological patient evidence indicating that damage to a distributed network of frontal and parietal regions is associated with impaired performance on tests of higher cognitive function (Jung and Haier, 2007; Chiang et al., 2009; Colom et al., 2009; Gläscher et al., 2010). Gläscher et al. (2010) applied voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping to elucidate the neural substrates of psychometric g, reporting a left lateralized fronto-parietal network that converges with the pattern of findings observed here. The present study contributes to this research program by elucidating the relationship between key competencies of psychometric intelligence and everyday social problem solving—providing evidence that these domains recruit a highly overlapping and broadly distributed network of frontal and parietal regions (Fig. 1A and B, and Fig. 3).

The available evidence indicates that the fronto-parietal network supports the integration and control of cognitive, social, and emotional representations (Gläscher et al., 2010; Barbey et al., 2012). Mechanisms for integration and control are critical for the optimal recruitment of internal resources to exhibit goal-directed behaviour—supporting executive functions that provide the basis for everyday social problem solving. We propose that mechanisms for integration and control are carried out by a central system that has extensive access to sensory and motor representations (cf. Miller and Cohen, 2001) and that the fronto-parietal network supports these functions. Elements of this network are connected with each other, as well as with other association cortices and subcortical areas, a property that allows widespread access to perceptual and motor representations at multiple levels. With this connectivity pattern and specialization in a wide variety of higher cognitive processes—including general intelligence (Barbey et al., 2012), fluid intelligence (Barbey et al., 2014c), cognitive flexibility (Barbey et al., 2013a), working memory (Barbey et al., 2011, 2013b), and emotional intelligence (Barbey et al., 2014a)—the fronto-parietal network can function as a source of integration and top–down control in the brain. This framework therefore complements existing neuroscience models by highlighting the importance of white-matter association tracts (e.g. the arcuate fasciculus) for the integration of cognitive, social, and emotional representations (Barbey et al., 2014a), while also emphasizing the central role of top–down mechanisms within frontal and parietal cortices for the executive control of behaviour (Miller and Cohen, 2001). According to this framework, the fronto-parietal network is a core system that supports the integration and control of distributed patterns of neural activity throughout the brain, providing an integrative architecture for key competencies of psychometric, social, and emotional intelligence. Although we have observed preferential recruitment of this system in the left hemisphere, evidence also exists for the engagement of this network in the right hemisphere (Barbey et al., 2014c), motivating further research on the principles that guide left versus right hemisphere systems for everyday problem solving.

Clinical implications

From a clinical perspective, understanding impairments in everyday social problem solving may facilitate the design of appropriate assessment tools and rehabilitation strategies for patients with brain injuries, with potential improvement in patients’ social abilities and daily living (Warschausky et al., 1997; Janusz et al., 2002; Ganesalingam et al., 2007; Hanten et al., 2008, 2011; Muscara et al., 2008; Robertson and Knight, 2008). The reported findings provide neuropsychological patient evidence linking impairments in everyday problem solving to particular profiles of brain damage. Indeed, the reported results support inferences about executive and social impairments that accompany damage to specific cortical networks and can be productively applied in a clinical setting: (i) to help explain why an individual is experiencing difficulties in these areas (i.e. due to damage to the underlying neural mechanisms); and (ii) to help predict the executive, social, and emotional processes that are likely to be impaired in the patient and to apply this knowledge to guide the selection of targeted clinical therapies.

The reported findings contribute to classic neuropsychological patient evidence on the consequences of prefrontal cortex damage for human problem solving. It has long been argued that patients with prefrontal cortex lesions have impairments in decision making and problem solving in real-world contexts, particularly problems involving planning and prediction (Penfield, 1935; Rylander and Frey, 1939; Harlow, 1999). However, a growing number of investigators have questioned the ability to capture and characterize these deficits adequately using standard neuropsychological measures and have called for tests that reflect real-world task requirements more accurately (Shallice and Burgess, 1991; Bechara et al., 1994). Indeed, the present study contributes to this effort, providing neuropsychological evidence from a large sample of patients with focal brain lesions to help characterize the neural architecture of social problem solving in everyday, ecologically valid decision contexts.

Conclusion

It is important to emphasize in closing that although the reported findings are obtained from a remarkable sample of well-characterized human lesion patients, conclusions drawn from this population are restricted to adult males and assess brain–behaviour relationships only within the cerebral cortex (and not involving subcortical brain structures) (Burgaleta et al., 2014). We note that the neuroscience literature on human intelligence includes indications that the neural substrates of g may vary by gender (Haier et al., 2005), an issue that we are unable to address in the current study. In addition, although we have made an effort to incorporate as many potentially relevant factors as possible in our analyses, the abilities measured by tests of everyday problem solving, psychometric intelligence, emotional intelligence, and personality do not provide a comprehensive assessment of all human psychological traits. There are other aspects, in addition to those measured here, which may contribute to social problem solving, notably those related to understanding the complex interplay between executive, social, and emotional processes in dynamic social settings. Indeed, the EPSI is a verbal laboratory-based problem solving task that requires more of the left hemisphere’s representations and processes particularly given that it is a forced-choice recognition task. Although task performance may represent the kind of deliberative processes that are required in real-life and in real-time, real-life interactions have many more cues and varying contextual circumstances making a one-to-one correspondence unlikely. Finally, additional research is needed to explore how mechanisms for social problem solving are related to a broader range of ecological contexts for social and emotional processing. Understanding the psychological and neural architecture of social problem solving will ultimately require a comprehensive assessment that examines a broader scope of issues. The reported findings contribute to this emerging research program by developing a cognitive neuroscience framework for studying everyday problem solving, demonstrating that social and emotional aspects of intellectual function emerge from an integrated network of brain regions that enable adaptive reasoning and problem solving in everyday social life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to S. Bonifant, B. Cheon, C. Ngo, A. Greathouse, V. Raymont, K. Reding, and G. Tasick for their invaluable help with the testing of participants and organization of this study. We would also like to acknowledge V. Raymont for contributing to the lesion tracing of patients in the VHIS.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EPSI

Everyday Problem Solving Inventory

- MSCEIT

Mayer, Salovey, Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test

- NEO-PI

Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory

- VHIS

Vietnam Head Injury Study

- WAIS

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke intramural research program and a project grant from the United States Army Medical Research and Material Command administered by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (Vietnam Head Injury Study Phase III: a 30-year post-injury follow-up study, grant number DAMD17-01-1-0675). R. Colom was supported by grant PSI2010-20364 from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación [Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain] and CEMU-2012-004 [Universidad Autonoma de Madrid].

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- Abu-Akel A. A neurobiological mapping of theory of mind. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003a;4:165–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Investigating the cognitive neuroscience of social behavior. Neuropsychologia. 2003b;41:119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Conceptual challenges and directions for social neuroscience. Neuron. 2010;65:752–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Anderson D. Social and emotional neuroscience. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:291–3. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apperly IA, Samson D, Chiavarino C, Humphreys GW. Frontal and temporo-parietal lobe contributions to theory of mind: neuropsychological evidence from a false-belief task with reduced language and executive demands. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1773–84. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (version 7.0) [Computer Program]. SPSS, Chicago; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Artistico D, Orom H, Cervone D, Krauss S, Houston E. Everyday challenges in context: the influence of contextual factors on everyday problem solving among young, middle-aged, and older adults. Exp Aging Res. 2010;36:230–47. doi: 10.1080/03610731003613938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Grafman J. Architecture of cognitive flexibility revealed by lesion mapping. Neuroimage. 2013a;82:547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Grafman J. Distributed neural system for emotional intelligence revealed by lesion mapping. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014a;9:265–72. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Grafman J. Neural mechanisms of discourse comprehension: a human lesion study. Brain. 2014b;137(Pt 1):277–87. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Paul EJ, Grafman J. Architecture of fluid intelligence and working memory revealed by lesion mapping. Brain Struct Funct. 2014c;219:485–94. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0512-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Solomon J, Krueger F, Forbes C, Grafman J. An integrative architecture for general intelligence and executive function revealed by lesion mapping. Brain. 2012;135:1154–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Grafman J. The prefrontal cortex and goal-directed social behavior. In: Decety J, Cacioppo J, editors. The oxford handbook of social neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 349–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J. Orbitofrontal contributions to human working memory. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:789–95. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J. Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex. 2013b;49:1195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Krueger F, Grafman J. An evolutionarily adaptive neural architecture for social reasoning. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:603–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Wilson SM, Saygin AP, Dick F, Sereno MI, Knight RT, et al. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:448–50. doi: 10.1038/nn1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Anderson SW. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition. 1994;50:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CM, Miller MB. How reliable are the results from functional magnetic resonance imaging? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:133–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F, Chen Y, Norris L. Everyday problem solving across the adult life span: influence of domain specificity and cognitive appraisal. Psychol Aging. 1997;12:684–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgaleta M, Macdonald PA, Martínez K, Román FJ, Álvarez-Linera J, González AR, et al. Subcortical regional morphology correlates with fluid and spatial intelligence. Human Brain Mapp. 2014;35:1957–68. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CL, Strauss E, Hultsch DF, Hunter MA. Cognitive functioning and everyday problem solving in older adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:432–52. doi: 10.1080/13854040590967063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushara KO, Grafman J, Hallett M. Neural correlates of auditory-visual stimulus onset asynchrony detection. J Neurosci. 2001;21:300–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00300.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey ME, Sacco W, Merkler J. An analysis of fatal and non-fatal head wounds incurred during combat in Vietnam by U.S. forces. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1982;508:351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caveness WF. Incidence of craniocerebral trauma in the United States in 1976 with trend from 1970 to 1975. Adv Neurol. 1979;22:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon S. Frontal lobe dysfunction and everyday problem-solving: social and non-social contributions. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2004;115:235–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon S, Rule A, Maudgil D, Martinos M, Pellijeff A, Frankl J, et al. Interpretation of mentalistic actions and sarcastic remarks: effects of frontal and posterior lesions on mentalising. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1725–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang MC, Barysheva M, Shattuck DW, Lee AD, Madsen SK, Avedissian C, et al. Genetics of brain fiber architecture and intellectual performance. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2212–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom R, Haier RJ, Head K, Alvarez-Linera J, Quiroga MA, Shih PC, et al. Gray matter correlates of fluid, crystallized, and spatial intelligence: testing the P-FIT model. Intelligence. 2009;37:124–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius SW, Caspi A. Everyday problem solving in adulthood and old age. Psychol Aging. 1987;2:144–53. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Overview: innovations in assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. Assessment. 2000;7:325–7. doi: 10.1177/107319110000700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, Peterson JB, Gray JR. Openness to experience, intellect, and cognitive ability. J Pers Assess. 2014;96:46–52. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.806327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Willis SL, Schaie KW. Everyday problem solving in older adults: observational assessment and cognitive correlates. Psychol Aging. 1995;10:478–91. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov M, Grafman J, Hollnagel C. The effects of frontal lobe damage on everyday problem solving. Cortex. 1996;32:357–66. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(96)80057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar L, Wegener D, MacCallum R, Strahan E. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:272–99. [Google Scholar]

- Frith U, Frith CD. Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:459–73. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesalingam K, Yeates KO, Sanson A, Anderson V. Social problem-solving skills following childhood traumatic brain injury and its association with self-regulation and social and behavioural functioning. J Neuropsychol. 2007;1:149–70. doi: 10.1348/174866407x185300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläscher J, Rudrauf D, Colom R, Paul LK, Tranel D, Damasio H, et al. Distributed neural system for general intelligence revealed by lesion mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910397107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory C, Lough S, Stone V, Erzinclioglu S, Martin L, Baron-Cohen S, et al. Theory of mind in patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: theoretical and practical implications. Brain. 2002;125:752–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haier RJ, Jung RE, Yeo RA, Head K, Alkire MT. The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: sex matters. Neuroimage. 2005;25:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanten G, Cook L, Orsten K, Chapman SB, Li X, Wilde EA, et al. Effects of traumatic brain injury on a virtual reality social problem solving task and relations to cortical thickness in adolescence. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:486–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanten G, Wilde EA, Menefee DS, Li X, Lane S, Vasquez C, et al. Correlates of social problem solving during the first year after traumatic brain injury in children. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:357–70. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow JM. Passage of an iron rod through the head. 1848. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11:281–3. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janusz JA, Kirkwood MW, Yeates KO, Taylor HG. Social problem-solving skills in children with traumatic brain injury: long-term outcomes and prediction of social competence. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8:179–94. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.3.179.13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AR. The g factor: the science of mental ability. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jezzini A, Caruana F, Stoianov I, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G. Functional organization of the insula and inner perisylvian regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:10077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200143109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung RE, Haier RJ. The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of intelligence: converging neuroimaging evidence. Behav Brain Sci. 2007;30:135–54. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X07001185. discussion 154–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R. Social neuroscience: stress and the city. Nature. 2011;474:452–3. doi: 10.1038/474452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Barbey AK, Postle BR, Grafman J. Superior parietal cortex is critical for the manipulation of information in working memory. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14980–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3706-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models: an introduction to factor, path, and structural analysis. 3rd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Makale M, Solomon J, Patronas NJ, Danek A, Butman JA, Grafman J. Quantification of brain lesions using interactive automated software. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2002;34:6–18. doi: 10.3758/bf03195419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar RA, Kelley WM, Heatherton TF, Macrae CN. Detecting agency from the biological motion of veridical vs animated agents. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:199–205. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiske M, Willis SL. Dimensionality of everyday problem solving in older adults. Psychol Aging. 1995;10:269–83. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Emotional intelligence: theory, findings, and implications. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Emotional intelligence: new ability or eclectic traits? Am Psychol. 2008;63:503–17. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:655–67. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mienaltowski A. Everyday problem solving across the adult life span: solution diversity and efficacy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1235:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscara F, Catroppa C, Anderson V. Social problem-solving skills as a mediator between executive function and long-term social outcome following paediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychol. 2008;2:445–61. doi: 10.1348/174866407x250820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN. Current directions in social cognitive neuroscience. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:254–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Lieberman MD. The emergence of social cognitive neuroscience. Am Psychol. 2001;56:717–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Evans J. The frontal lobe in man: a clinical study of maximum removals. Brain. 1935;58:115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Quilty LC, DeYoung CG, Oakman JM, Bagby RM. Extraversion and behavioral activation: integrating the components of approach. J Pers Assess. 2014;96:87–94. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.834440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymont V, Salazar AM, Lipsky R, Goldman D, Tasick G, Grafman J. Correlates of posttraumatic epilepsy 35 years following combat brain injury. Neurology. 2010;75:224–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e6d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rish BL, Caveness WF, Dillon JD, Kistler JP, Mohr JP, Weiss GH. Analysis of brain abscess after penetrating craniocerebral injuries in Vietnam. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:535–41. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RH, Knight RG. Evaluation of social problem solving after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18:236–50. doi: 10.1080/09602010701734438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Hoogenraad FG, Sprenger M, Valk J, Scheltens P. Test-retest analysis with functional MR of the activated area in the human visual cortex. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1317–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AD, Bullock PR, Polkey CE, Morris RG. “Theory of mind” impairments and their relationship to executive functioning following frontal lobe excisions. Brain. 2001;124:600–16. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander G, Frey FH. Personality changes after operations on the frontal lobes; a clinical study of 32 cases. In: Munksgaard E, Milford H, editors. London; Copenhagen: Oxford University Press; 1939.

- Sabbagh MA. Understanding orbitofrontal contributions to theory-of-mind reasoning: implications for autism. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2003.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R. Uniquely human social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:235–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Kanwisher N. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1835–42. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T, Burgess PW. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 2):727–41. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Aharon-Peretz J. The neuroanatomical basis of understanding sarcasm and its relationship to social cognition. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:288–300. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Aharon-Peretz J. Characterization of empathy deficits following prefrontal brain damage: the role of the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:324–37. doi: 10.1162/089892903321593063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WK, Avery JA, Barcalow JC, Bodurka J, Drevets WC, Bellgowan P. Keeping the body in mind: Insula functional organization and functional connectivity integrate interoceptive, exteroceptive, and emotional awareness. Human Brain Mapp. 2013;34:2944–58. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WK, Martin A. The anterior temporal lobes and the functional architecture of semantic memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:645–9. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WK, Reddish M, Bellgowan PS, Martin A. The selectivity and functional connectivity of the anterior temporal lobes. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:813–25. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Raymont V, Braun A, Butman JA, Grafman J. User-friendly software for the analysis of brain lesions (ABLe) Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;86:245–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. Handbook of intelligence. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT, Gallup GG, Jr, Alexander MP. The frontal lobes are necessary for ‘theory of mind’. Brain. 2001;124:279–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton WL, Deria S, Gelb S, Shapiro RJ, Hill A. Neuropsychological mediators of the links among age, chronic illness, and everyday problem solving. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:470–81. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warschausky S, Cohen EH, Parker JG, Levendosky AA, Okun A. Social problem-solving skills of children with traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Rehabil. 1997;1:77–81. doi: 10.3109/17518429709025850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence test administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychology Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield KE, Wiggins S. The influence of social support and health on everyday problem solving in adult African Americans. Exp Aging Res. 2003;29:1–13. doi: 10.1080/03610730303703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolgar A, Parr A, Cusack R, Thompson R, Nimmo-Smith I, Torralva T, et al. Fluid intelligence loss linked to restricted regions of damage within frontal and parietal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14899–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007928107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.