Abstract

Background

Migraine is a common, disabling condition and a burden for the individual, health services and society. Many sufferers choose not to, or are unable to, seek professional help and rely on over-the-counter analgesics. Co-therapy with an antiemetic should help to reduce nausea and vomiting commonly associated with migraine headaches.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and tolerability of aspirin, alone or in combination with an antiemetic, compared to placebo and other active interventions in the treatment of acute migraine headaches in adults.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Oxford Pain Relief Database for studies through 10 March 2010.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, double-blind, placebo- or active-controlled studies using aspirin to treat a discrete migraine headache episode, with at least 10 participants per treatment arm.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Numbers of participants achieving each outcome were used to calculate relative risk and numbers needed to treat (NNT) or harm (NNH) compared to placebo or other active treatment.

Main results

Thirteen studies (4222 participants) compared aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg, alone or in combination with metoclopramide 10 mg, with placebo or other active comparators, mainly sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg. For all efficacy outcomes, all active treatments were superior to placebo, with NNTs of 8.1, 4.9 and 6.6 for 2-hour pain-free, 2-hour headache relief, and 24-hour headache relief with aspirin alone versus placebo, and 8.8, 3.3 and 6.2 with aspirin plus metoclopramide versus placebo. Sumatriptan 50 mg did not differ from aspirin alone for 2-hour pain-free and headache relief, while sumatriptan 100 mg was better than the combination of aspirin plus metoclopramide for 2-hour pain-free, but not headache relief; there were no data for 24-hour headache relief.

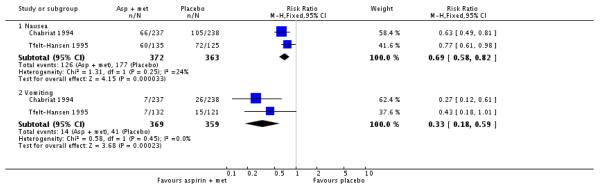

Associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia were reduced with aspirin compared with placebo, with additional metoclopramide significantly reducing nausea (P < 0.00006) and vomiting (P = 0.002) compared with aspirin alone.

Fewer participants needed rescue medication with aspirin than with placebo. Adverse events were mostly mild and transient, occurring slightly more often with aspirin than placebo.

Authors’ conclusions

Aspirin 1000 mg is an effective treatment for acute migraine headaches, similar to sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg. Addition of metoclopramide 10 mg improves relief of nausea and vomiting. Adverse events were mainly mild and transient, and were slightly more common with aspirin than placebo, but less common than with sumatriptan 100 mg.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal [*therapeutic use]; Antiemetics [*therapeutic use]; Aspirin [*therapeutic use]; Drug Therapy, Combination [methods]; Metoclopramide [therapeutic use]; Migraine Disorders [complications; *drug therapy]; Nausea [drug therapy; etiology]; Photophobia [drug therapy; etiology]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sumatriptan [therapeutic use]; Vomiting [drug therapy; etiology]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Migraine is a common, disabling headache disorder, affecting about 12% of Western populations, and with considerable social and economic impact. It is more prevalent in women than men (on the order of 18% versus 6% 1-year prevalence), and in the age range 30 to 50 years (Hazard 2009; Lipton 2007; Moens 2007). The International Headache Society (IHS) classifies two major subtypes. Migraine without aura is the most common, and usually more disabling, subtype. It is characterised by attacks lasting 4 to 72 hours that are typically of moderate to severe pain intensity, unilateral, pulsating, aggravated by normal physical activity and associated with nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia. Migraine with aura is characterised by reversible focal neurological symptoms that develop over a period of 5 to 20 minutes and last for less than 60 minutes, followed by headache with the features of migraine without aura. In some cases the headache may lack migrainous features or be absent altogether (IHS 2004).

A recent large prevalence study in the US found that over half of migraineurs had severe impairment or required bed rest during attacks. Despite this high level of disability and a strong desire for successful treatment, only a proportion of migraine sufferers seek professional advice for the treatment of attacks. The majority were not taking any preventive medication, although one-third met guideline criteria for offering or considering it. Nearly all (98%) migraineurs used acute treatments for attacks, with 49% using over-the-counter (OTC) medication only, 20% using prescription medication, and 29% using both. OTC medication included aspirin, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol (acetaminophen) and paracetamol with caffeine (Bigal 2008; Diamond 2007; Lipton 2007). Similar findings have been reported from other large studies in France and Germany (Lucas 2006; Radtke 2009).

The significant impact of migraine with regard to pain, disability, social functioning, quality of relationships, emotional well-being and general health (Edmeads 1993; Osterhaus 1994; Solomon 1997) results in a huge burden for the individual, health services and society (Clarke 1996; Ferrari 1998; Hazard 2009; Hu 1999; Solomon 1997). The annual US economic burden relating to migraine, including missed days of work and lost productivity, is US$14 billion (Hu 1999). Thus successful treatment of acute migraine attacks not only benefits patients by reducing their disability and improving health-related quality of life, but also reduces the need for healthcare resources and increases economic productivity (Jhingran 1996; Lofland 1999).

Description of the intervention

Medicines derived from willow bark, which is rich in salicylate, have been used for centuries for treating pain, fever and inflammation. In the mid-19th century, chemists first synthesised acetylsalicylic acid, and by the end of the century, Bayer had patented and were selling the drug, which they called aspirin, around the world.

Aspirin is used to treat mild to moderate pain, including migraine headache pain; inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis; and, in low doses, as an antiplatelet agent in cardiovascular disease. It is a potent gastrointestinal irritant, and may cause discomfort, ulcers and bleeding. It may aIso cause tinnitus at high dose, and it is no longer used in children and adolescents, in whom it may cause Reye’s syndrome (swelling of the brain that may lead to coma and death). Its use as an analgesic and antipyretic agent has declined, largely due to these adverse events, as newer products have become available. However, in some countries it may be the only drug readily available, and for some conditions, such as migraine, some individuals report it to be an effective and reliable treatment.

In order to establish whether aspirin is an effective analgesic at a specified dose in acute migraine attacks, it is necessary to study its effects in circumstances that permit detection of pain relief. Such studies are carried out in individuals with established pain of moderate to severe intensity, using single doses of the interventions. Participants who experience an inadequate response with either placebo or active treatment are permitted to use rescue medication, and the intervention is considered to have failed in those individuals. In clinical practice, however, individuals would not normally wait until pain is of at least moderate severity, and may take a second dose of medication if the first dose does not provide adequate relief. Once analgesic efficacy is established in studies using single doses in established pain, further studies may investigate different treatment strategies and patient preferences. These are likely to include treating the migraine attack early while pain is mild, and using a low dose initially, with a second dose if response is inadequate.

How the intervention might work

Aspirin irreversibly inhibits cyclo-oxygenase enzymes, which are needed for prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis. Prostaglandins mediate a variety of physiological functions such as maintenance of the gastric mucosal barrier, regulation of renal blood flow, and regulation of endothelial tone. They also play an important role in mediating inflammatory and nociceptive processes. Suppression of prostaglandin synthesis is believed to underlie the analgesic effects of aspirin (Vane 1971).

The efficacy of oral medications is reduced in many migraineurs because of impaired gastrointestinal motility, which is associated with nausea, and because of non-absorption of the drug due to vomiting (Volans 1974). The addition of an antiemetic may improve outcomes by alleviating the often incapacitating symptoms of nausea and vomiting, and (at least potentially) by enhancing the bioavailability of the co-administered analgesic. In particular, prokinetic antiemetics such as metoclopramide, which stimulate gastric emptying, may improve outcomes by increasing absorption of the analgesic (in this case, aspirin; Ross-Lee 1983; Volans 1975). It has been claimed that treatment with metoclopramide alone can reduce pain in severe migraine attacks (Colman 2004; Salazar-Tortolero 2008), but this claim requires further investigation because it is based on studies involving few participants, and metoclopramide has not been shown to be an analgesic in classical pain studies. The present review will seek to determine whether treatment of acute migraine attacks with aspirin plus an antiemetic is in any way superior to treatment with aspirin alone.

Why it is important to do this review

Population surveys show that aspirin is frequently used to treat migraine headaches, but we could find no systematic review of the efficacy of this intervention in adults. It is important to know where this widely available and inexpensive drug fits in the range of therapeutic options for migraine therapy. For many migraineurs, non-prescription therapies offer convenience and may be the only therapies available or affordable.

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this review is to determine the efficacy and tolerability of aspirin, alone or in combination with an antiemetic, compared to placebo and other active interventions in the treatment of acute migraine headaches in adults.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised, double-blind, placebo or active-controlled studies using aspirin to treat a discrete migraine headache episode were included. Studies had to have a minimum of 10 participants per treatment arm and report dichotomous data for at least one of the outcomes specified below. Studies reporting treatment of consecutive headache episodes were accepted if outcomes for the first, or each, episode were reported separately. Cross-over studies were accepted if there was adequate washout between treatments.

Types of participants

Studies included adults (at least 18 years of age) with migraine. The diagnosis of migraine specified by the International Headache Society (IHS 1988; IHS 2004) was used, although other definitions were considered if they conformed in general to IHS diagnostic criteria. There were no restrictions on migraine frequency, duration or type (with or without aura). Participants taking stable prophylactic therapy to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks were accepted; details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Types of interventions

Included studies used either a single dose of aspirin to treat a discrete migraine headache episode when pain was of moderate to severe intensity, or investigated different dosing strategies and/or timing of the first dose in relation to headache intensity. There were no restrictions on dose or route of administration, provided the medication was self-administered.

Included studies could use either aspirin alone, or aspirin plus an antiemetic. The antiemetic had to be taken either combined with aspirin in a single formulation, or separately not more than 30 minutes before aspirin, and had to be self-administered.

A placebo comparator is essential to demonstrate that aspirin is effective in this condition. Active-controlled trials without a placebo were considered as secondary evidence. Studies to demonstrate prophylactic efficacy in reducing the number or frequency of migraine attacks were not included.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The choice of main outcome measures for this review was made by taking into consideration scientific rigour, availability of data and patient preferences (Lipton 1999). Patients with acute migraine headaches have rated complete pain relief, no headache recurrence, rapid onset of pain relief, and no side effects as the four most important outcomes (Lipton 1999).

In view of these patient preferences, and in line with the guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine issued by the IHS (IHS 2000), the main outcomes to be considered were:

Pain-free at 2 hours, without the use of rescue medication;

Reduction in headache pain (‘headache relief’) at 1 and 2 hours (pain reduced from moderate or severe to none or mild without the use of rescue medication);

Sustained pain-free over 24 hours (pain-free within 2 hours, with no use of rescue medication or recurrence within 24 hours);

Sustained pain reduction over 24 hours (headache relief at 2 hours, sustained for 24 hours, with no use of rescue medication or a second dose of study medication).

Pain intensity or pain relief was measured by the patient (not the investigator or carer). Pain measures accepted for the primary outcomes were:

Pain intensity (PI): 4-point categorical scale, with wording equivalent to none, mild, moderate and severe; or 100 mm VAS;

Pain relief (PR): 5-point categorical scale, with wording equivalent to none, a little, some, a lot, complete; or 100 mm VAS.

Only data obtained directly from the patient will be considered.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes considered included:

Participants with any adverse event over 24 hours post-dose;

Participants with particular adverse events over 24 hours post-dose;

Withdrawals due to adverse events over 24 hours post-dose;

Relief of headache-associated symptoms;

Functional disability.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following databases were searched:

Cochrane CENTRAL, Issue 1, 2010;

MEDLINE (via OVID), 10 March 2010;

EMBASE (via OVID), 10 March 2010;

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 1 for the search strategy for MEDLINE (via OVID), Appendix 2 for the search strategy for EMBASE, and Appendix 3 for the search strategy for CENTRAL. There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of retrieved studies and review articles were searched for additional studies. Grey literature and abstracts were not searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently carried out the searches and selected studies for inclusion. Titles and abstracts of all studies identified by electronic searches were viewed on screen, and any that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria were excluded. Full copies of the remaining studies were read to identify those suitable for inclusion. Disagreements were settled by discussion with a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from included studies using a standard data extraction form. Disagreements were settled by discussion with a third review author. Data were entered into RevMan 5.0 by one author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality was assessed using the Oxford Quality Score (Jadad 1996b).

The scale is used as follows:

Is the study randomised? If yes, give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes, add one point; if no, deduct one point.

Is the study double blind? If yes, add one point.

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes, add one point; if no, deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes, add one point.

The scores for each study are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table.

A risk of bias table was also completed, using assessments of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative risk (or ‘risk ratio’, RR) was used to establish statistical difference. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) and pooled percentages were used as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

The following terms were used to describe adverse outcomes in terms of harm or prevention of harm:

When significantly fewer adverse outcomes occurred with aspirin than with control (placebo or active) we used the term the number needed to treat to prevent one event (NNTp).

When significantly more adverse outcomes occurred with aspirin compared with control (placebo or active) we used the term the number needed to harm or cause one event (NNH).

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted randomisation to individual patient only.

Dealing with missing data

The most likely source of missing data is in cross-over studies. Where this was an issue, only first-period data were used.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L’Abbe 1987).

Data synthesis

Studies using a single dose of aspirin in established pain of at least moderate intensity were analysed separately from studies in which medication was taken before pain was well established or in which a second dose of medication was permitted.

Effect sizes were calculated and data combined for analysis only for comparisons and outcomes where there were at least two studies and 200 participants (Moore 1998). In case only one study on relevant outcomes in at least 200 participants was available, prohibiting combining of data for analysis, a summary of data on relevant outcomes is provided. Relative risk of benefit or harm was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a fixed-effect model (Morris 1995). NNT, NNTp and NNH with 95% CIs were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the relative risk of benefit or harm did not include the number one.

Significant differences between NNT, NNTp or NNH for different groups in subgroup and sensitivity analyses were determined using the z test (Tramer 1997).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Issues for potential subgroup analysis were dose, monotherapy versus combination with an antiemetic, formulation and route of administration. For combined treatment with an antiemetic, we planned to compare different antiemetics if there were sufficient data.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was anticipated for study quality (Oxford Quality Score of 2 versus 3 or more), and for migraine type (with aura versus without aura). A minimum of two studies and 200 participants had to be available for any sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Included studies

Thirteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (Boureau 1994; Chabriat 1994; Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Geraud 2002; Henry 1995; Lange 2000; Le Jeunne 1998; Lipton 2005; MacGregor 2002; Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992; Titus 2001), with a total of 5261 treated migraine attacks (4222 participants) providing data; Boureau 1994; Diener 2004b; MacGregor 2002 together provided information on treatment of 1039 more migraine attacks than participants. Details of the included studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

All included studies recruited participants between 18 and 65 years of age (mean ages ranging from 37 to 44 years), meeting IHS criteria for migraine with or without aura (IHS 1988; IHS 2004). All participants had a history of migraine symptoms for at least 12 months, with between one and six attacks per month of moderate to severe intensity, prior to the study period. One study (Thomson 1992) excluded participants needing prophylactic treatment. Four studies specified that any prophylactic treatment had to have been stable for at least 2 (Boureau 1994) or 3 (Chabriat 1994; Le Jeunne 1998; Lipton 2005) months before the study period, while the remainder did not mention prophylaxis.

Three studies excluded participants who vomited either at least 20% of the time during migraine attacks (Lange 2000; Lipton 2005) or during the majority of attacks (MacGregor 2002). Another study excluded participants whose migraine headaches were never accompanied by nausea or vomiting (Chabriat 1994). One study excluded data from migraine attacks with aura (Henry 1995), whilst another study used only data from migraine attacks without aura that also featured all three symptoms of nausea, photophobia and phonophobia (Diener 2004a). Five studies excluded participants who also experienced other types of headache (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004b; Geraud 2002; Henry 1995; Titus 2001).

Five studies had only a placebo comparator (Chabriat 1994; Henry 1995; Lange 2000; Lipton 2005; MacGregor 2002), four had only an active comparator (Geraud 2002; Le Jeunne 1998; Thomson 1992; Titus 2001), and four had both placebo and active comparators (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Tfelt-Hansen 1995).

All treatments were administered orally, and when the headache was of moderate or severe intensity, except in Boureau 1994, where up to 15% of participants had “slight” headache at baseline. No studies specifically investigated early treatment of attacks while pain intensity was still mild. Aspirin 1000 mg was given either as a tablet or an effervescent solution to 940 participants in five studies (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Lange 2000; Lipton 2005). In one study, aspirin was given to 73 participants as a 900 mg mouth-dispersible dose (MacGregor 2002). In seven studies, aspirin equivalent to 900 mg was given either as the lysine salt, calcium carbasalate (a soluble complex of aspirin) or effervescent solution, in combination with metoclopramide 10 mg, to 1186 participants (Chabriat 1994; Geraud 2002; Henry 1995; Le Jeunne 1998; Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992; Titus 2001). We did not identify any studies in which aspirin was combined with an antiemetic other than metoclopramide.

Sumatriptan 50 mg was given to 361 participants in two studies (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b), and sumatriptan 100 mg to 294 participants in another two studies (Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992). Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was given to 326 participants in one study (Geraud 2002). Four studies compared aspirin treatment with non-triptan medications: one gave acetaminophen 400 mg plus codeine 25 mg to 198 participants (Boureau 1994); one gave ibuprofen 400 mg to 212 participants (Diener 2004b); one gave ergotamine 1 mg plus 100 mg caffeine to 132 participants (Le Jeunne 1998); and the other gave ergotamine 2 mg plus caffeine 200 mg to 115 participants (Titus 2001). One thousand and four hundred and twenty-four (1424) participants received placebo.

Some studies were inconsistent in the denominators reported and, for instance, reported on one or two patients fewer than the intention-to-treat population for some outcomes, but not for others, without giving a reason. As the denominators were always within a few patients of the intention-to-treat population, we used the denominators given.

Most studies used a parallel-group design, in which participants received only one type of medication, but three (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004b; MacGregor 2002) used a cross-over design, in which participants treated consecutive headaches with different study medications. Most studies also asked participants to treat only one attack with a particular study medication, but in five studies more than one attack was treated with the same medication. In Chabriat 1994, Le Jeunne 1998 and Tfelt-Hansen 1995 two attacks were treated, while in Geraud 2002 and Thomson 1992 three attacks were treated; some outcomes were reported for each attack separately, while for other outcomes attacks were combined. We have used data for the first attack only, where these data were reported separately, for efficacy outcomes to avoid problems of double counting participants and repeated measures for the same individuals; for use of rescue medication and adverse event data, we have accepted data from multiple attacks in the absence of first-attack data in order to be inclusive and provide conservative estimates. In Geraud 2002, a second dose of study medication was permitted if there was an inadequate response to the first; data for the first dose in the first attack was available for one primary outcome. In Titus 2001 one attack was treated with up to three doses of the same medication if an adequate response was not obtained; data for our primary outcomes were not available for the first dose only.

Excluded studies

Six studies were excluded after reading the full report (Chabriat 1993; Diener 2005; Limmroth 1999; Nebe 1995; Tfelt-Hansen 1980; Tfelt-Hansen 1984). Reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies were randomised and double-blind, and all reported on withdrawals and dropouts, thus minimising bias. Four scored 5 of 5 (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Geraud 2002; Titus 2001), six scored 4 of 5 (Boureau 1994; MacGregor 2002; Le Jeunne 1998; Lipton 2005; Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992) and three scored 3 of 5 (Chabriat 1993; Henry 1995; Lange 2000) on the Oxford Quality Score. Points were lost because of failure to adequately describe the methods of randomisation and blinding. Details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

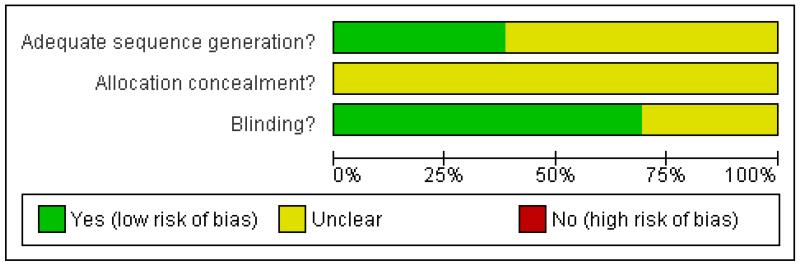

A risk of bias table was completed for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding. No study described the method of allocation concealment, but none were at high risk of bias (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Aspirin doses of 900 mg and 1000 mg were considered sufficiently similar to combine for analysis. All included studies that provided data for analysis reported outcomes using the standard 4-point categorical pain intensity scale (none, mild, moderate, severe). Details of outcomes in individual studies are provided in Appendix 4 (efficacy), Appendix 5 (migraine-associated symptoms) and Appendix 6 (adverse events and withdrawals).

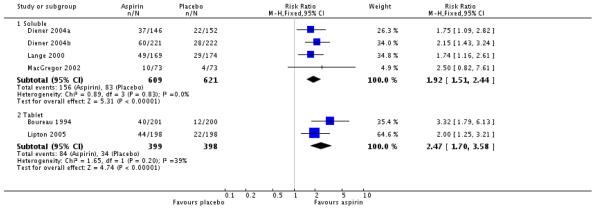

Pain-free at 2 hours

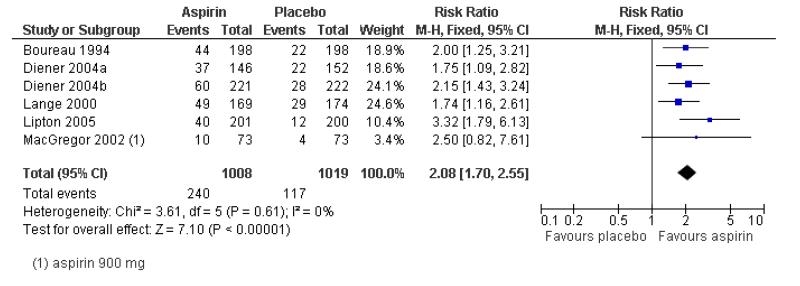

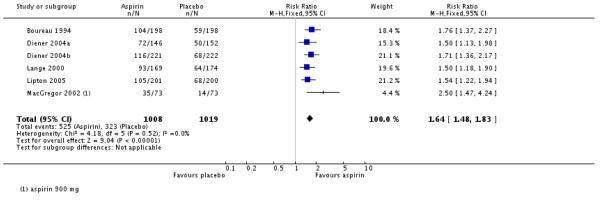

Aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg versus placebo

Six studies (2027 participants) provided data on the proportion of patients pain-free at 2 hours. Three used a 1000 mg effervescent formulation of aspirin (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Lange 2000), two used a 1000 mg oral tablet formulation (Boureau 1994; Lipton 2005) and one used a 900 mg mouth-dispersible dose (MacGregor 2002).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with aspirin 1000 mg was 24% (240/1008; range 14% to 29%).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with placebo was 11% (117/1019; range 5% to 17%).

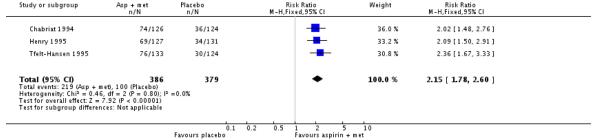

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6; Figure 2) giving an NNT for pain-free at 2 hours of 8.1 (6.4 to 11; Summary of results A).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Pain free at 2 hours.

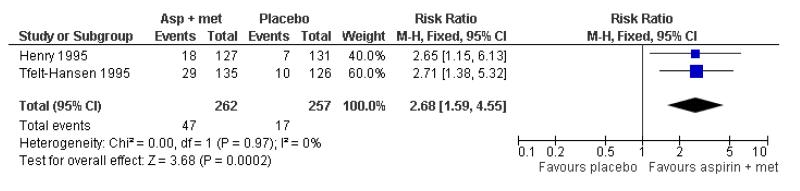

Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo

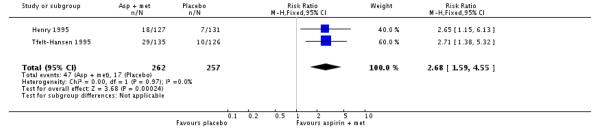

Two studies (519 participants) reported efficacy data for pain-free at 2 hours with 900 mg oral tablet formulation in combination with oral metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo (Henry 1995; Tfelt-Hansen 1995).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg was 18% (47/262; range 14% to 21%).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with placebo was 7% (17/257; range 5% to 8%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.7 (1.6 to 4.6; Figure 3), giving an NNT for pain-free at 2 hours of 8.8 (5.9 to 17; Summary of results A).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.2 Pain free at 2 hours.

Subgroup analysis comparing studies using aspirin alone and studies using aspirin plus metoclopramide gave z = 0.3051, P = 0.76. There was no significant difference between treatments for this outcome.

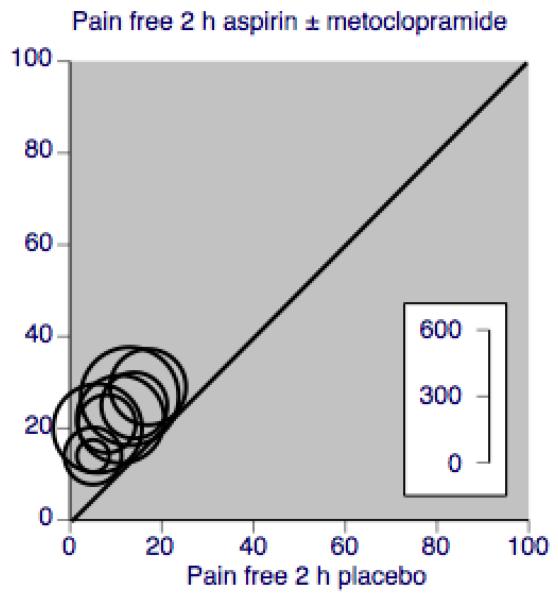

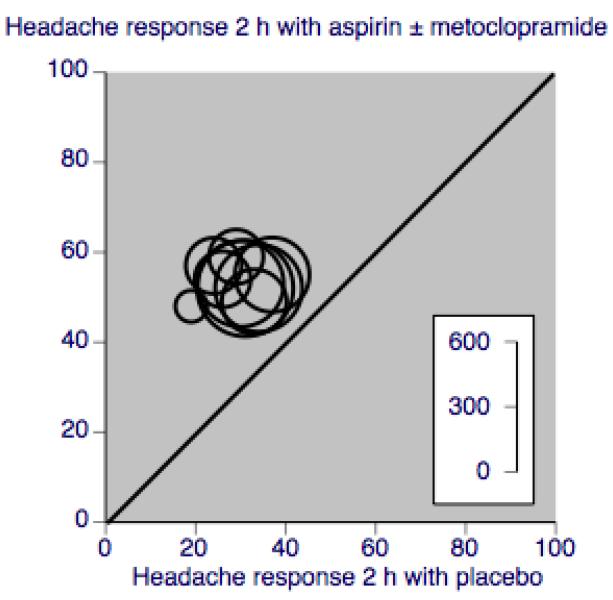

A L’Abbé plot for this outcome shows a high degree of clinical homogeneity in these studies of aspirin ± metoclopramide versus placebo (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

L’Abbé plot showing pain-free at 2 h response in individual studies. Each circle represents one study, with size on the inset scale.

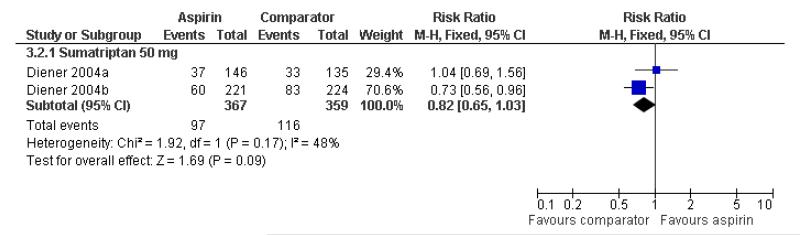

Aspirin 1000 mg versus active comparator

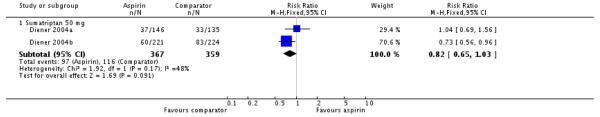

Two studies (726 participants) compared effervescent aspirin 1000 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with aspirin 1000 mg was 26% (97/367).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with sumatriptan 50 mg was 32% (116/359).

The relative benefit of aspirin compared with sumatriptan was 0.82 (0.65 to 1.03; Figure 5). There was no significant difference between treatments (Summary of results A).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg versus active comparator, outcome: 3.2 Pain free at 2 hours.

One study (Boureau 1994) compared 1000 mg aspirin (tablet) with paracetamol 400 mg plus codeine 25 mg, while another (Diener 2004b) compared it with ibuprofen 400 mg. In both cases, there were insufficient data for analysis (Appendix 4).

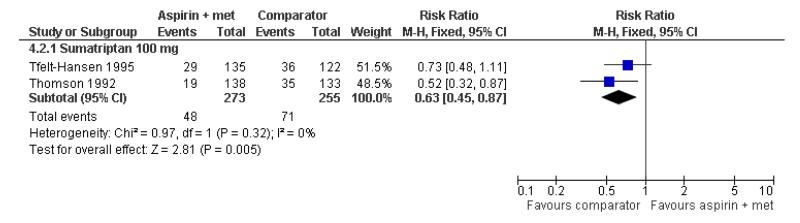

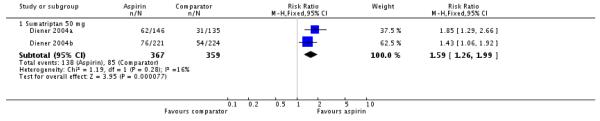

Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus active comparator

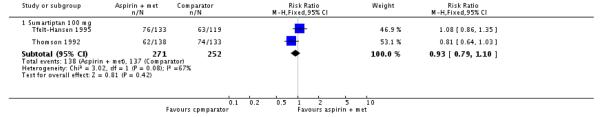

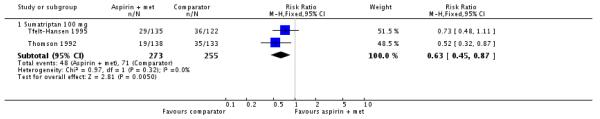

Two studies (528 participants) compared aspirin 900 mg (tablet or lysine equivalent) plus metoclopramide 10 mg with sumatriptan 100 mg (Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg was 18% (48/273).

The proportion of participants pain-free at 2 hours with sumatriptan 100 mg was 28% (71/255).

The relative benefit of aspirin plus metoclopramide compared with sumatriptan was 0.63 (0.45 to 0.87; Figure 6), giving an NNTp of 9.8 (5.8 to 32; Summary of results A). In other words, for every 10 participants treated with sumatriptan 100 mg, one would be pain-free within 2 hours who would not have been if treated with aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus active comparator, outcome: 4.2 Pain free at 2 hours.

One study (Le Jeunne 1998) compared aspirin 900 mg (as calcium carbasalate) plus metoclopramide 10 mg with ergotamine 1 mg plus caffeine 100 mg (266 participants). There were insufficient data for analysis (Appendix 4).

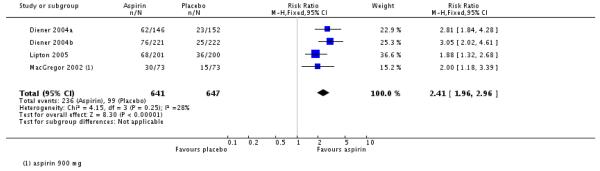

Headache relief at 1 hour

Aspirin 900 or 1000 mg versus placebo

Four studies (1288 participants) comparing aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg with placebo provided data. Two used an effervescent formulation (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b), one a mouth dispersible formulation (MacGregor 2002) and one a tablet (Lipton 2005).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 1 hour with aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg was 37% (236/641; range 34% to 42%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 1 hour with placebo was 15% (99/647; range 11% to 21%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.4 (2.0 to 3.0; Analysis 1.3), giving an NNT of 4.7 (3.8 to 5.9; Summary of results A).

Aspirin 1000 mg versus active comparator

Two studies (726 participants) comparing aspirin 1000 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg provided data (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b). Both used effervescent aspirin and oral sumatriptan.

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 1 hour with aspirin 1000 mg was 38% (138/367; range 34% to 42%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 1 hour with sumatriptan 50 mg was 24% (85/359; range 23% to 24%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with sumatriptan 50 mg was 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0; Analysis 3.3), giving an NNT of 7.2 (4.9 to 14; Summary of results A).

One study (Diener 2004b) compared aspirin 1000 mg with ibuprofen 400 mg (432 participants). There were insufficient data for analysis.

Aspirin plus metoclopramide versus placebo or versus active comparator

No studies using aspirin plus metoclopramide reported on headache relief at 1 hour.

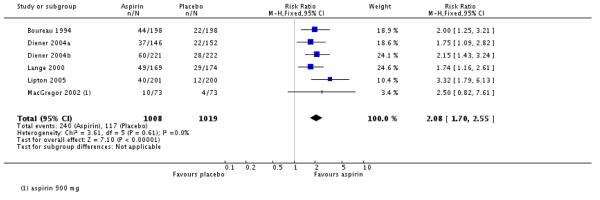

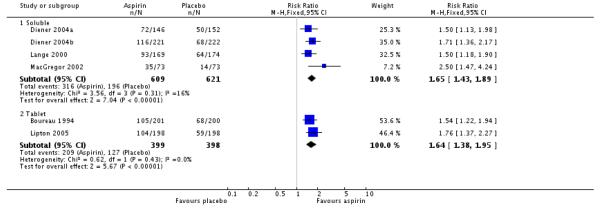

Headache relief at 2 hours

Aspirin 900 or 1000 mg versus placebo

Six studies (2027 participants) in which patients were treated with aspirin alone provided data for headache relief at 2 hours, defined as a pain reduction from moderate or severe intensity to mild or none. Three studies used an effervescent formulation (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Lange 2000), whilst the other three studies used a mouth-dispersible (MacGregor 2002) or oral tablet formulation (Boureau 1994; Lipton 2005).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg was 52% (525/1008; range 48% to 55%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with placebo was 32% (323/1019; range 19% to 37%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8; Analysis 1.1), giving an NNT of 4.9 (4.1 to 6.2; Summary of results A).

Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo

Three studies (765 participants) provided data for headache relief at 2 hours with aspirin and metoclopramide combination treatment. Two studies used a lysine equivalent formulation of aspirin (Chabriat 1994; Tfelt-Hansen 1995), whilst the other study used an effervescent formulation (Henry 1995).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg was 57% (219/386; range 54% to 59%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with placebo was 26% (100/379; range 24% to 29%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.2 (1.8 to 2.6; Analysis 2.1), giving an NNT of 3.3 (2.7 to 4.2; Summary of results A).

Subgroup analysis comparing studies using aspirin alone and studies using aspirin plus metoclopramide gave z = 2.48, P = 0.0131, showing that aspirin plus metoclopramide was significantly more effective than aspirin alone at achieving headache relief at 2 hours. A L’Abbé plot for this outcome shows a high degree of clinical homogeneity in these studies of aspirin ± metoclopramide versus placebo (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

L’Abbé plot showing headache response at 2 h in individual studies. Each circle represents one study, with size on the inset scale.

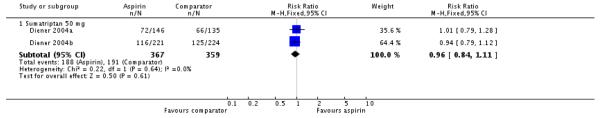

Aspirin 1000 mg versus active comparator

Two studies (726 participants) compared effervescent aspirin 1000 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with aspirin 1000 mg was 51% (188/367).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with sumatriptan 50 mg was 53% (191/359).

The relative benefit of aspirin compared with sumatriptan was 0.96 (0.84 to 1.1; Analysis 3.1). There was no significant difference between treatments (Summary of results A).

One study (Boureau 1994) compared 1000 mg aspirin (tablet) with paracetamol 400 mg plus codeine 25 mg, and another (Diener 2004b) compared it with ibuprofen 400 mg. In both cases, there were insufficient data for analysis (Appendix 4).

Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus active comparator

Two studies (523 participants) compared aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg with sumatriptan 100 mg (Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992). One used the lysine equivalent and the other a standard oral tablet.

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg was 51% (138/271).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with sumatriptan 100 mg was 54% (137/252).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 0.93 (0.79 to 1.1; Analysis 4.1). There was no significant difference between treatments (Summary of results A).

One study each compared aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg with zolmitriptan 25 mg (Geraud 2002) and ergotamine 1 mg plus caffeine 100 mg (Le Jeunne 1998). There were insufficient data for analysis for either comparator (Appendix 4). Titus 2001 compared aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg with ergotamine 2 mg + caffeine 200 mg, but reported no usable data.

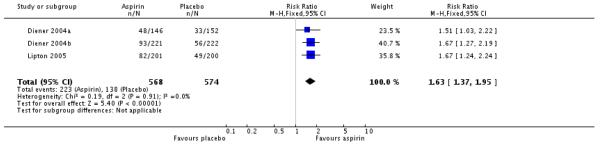

Participants with 24-hour sustained headache relief

This was defined as the proportion of treated patients that experienced headache relief at 2 hours (pain reduction from moderate or severe to mild or none) and sustained this relief throughout the remaining 24-hour assessment period, without use of additional medication.

Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo

Three studies (1142 participants) provided data for this outcome. Two used an effervescent formulation (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b) and one a tablet (Lipton 2005).

The proportion of participants with 24-hour sustained relief with aspirin 1000 mg was 39% (223/568; range 33% to 42%).

The proportion of participants with 24-hour sustained relief with placebo was 24% (138/574; range 22% to 25%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.4 to 2.0; Analysis 1.4), giving an NNT for 24-hour sustained relief of 6.6 (4.9 to 10; Summary of results A).

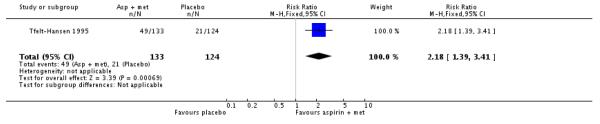

Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo

One study (257 participants) reported this outcome (Tfelt-Hansen 1995). Because there were more than 200 participants, for information and comparison the results are given in Summary of results A, plus a calculation of NNT where there was a significant benefit over placebo. Subgroup analysis comparing studies using aspirin alone and studies using aspirin plus metoclopramide gave z = 0.7789, P = 0.43. There was no significant difference between treatments for this outcome.

Participants with 24-hour sustained pain-free

None of the studies provided data on the proportion of participants who were pain-free at 2 hours and remained pain-free for 24 hours. Hence no analysis of this outcome was possible.

Summary of results A.

Pain-free and headache relief

| Studies | Attacks treated | Treatment (%) | Placebo or comparator (%) | NNT/NNTp (95% CI) | P for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain-free at 2 hours | ||||||

| Aspirin 900 or 1000 mg versus placebo | 6 | 2027 | 24 | 11 | 8.1 (6.4 to 11) | z = 0.3051 P = 0.76 |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 2 | 519 | 18 | 7 | 8.8 (5.9 to 17) | |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 726 | 26 | 32 | Not calculated | |

| Aspirin 900mg + metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 528 | 18 | 28 | 9.8 (5.8 to 32) | |

| Headache relief at 1 hour | ||||||

| Aspirin 900 or 1000 mg versus placebo | 4 | 1288 | 37 | 15 | 4.7 (3.8 to 5.9) | |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 726 | 38 | 24 | 7.2 (4.9 to 14) | |

| Headache relief at 2 hours | ||||||

| Aspirin 900 or 1000 mg versus placebo | 6 | 2027 | 52 | 32 | 4.9 (4.1 to 6.2) | z = 2.4847 P = 0.013 |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 3 | 765 | 57 | 26 | 3.3 (2.7 to 4.2) | |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 522 | 51 | 53 | Not calculated | |

| Aspirin 900mg + metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 523 | 51 | 54 | Not calculated | |

| Sustained headache relief at 24 hours | ||||||

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 3 | 1142 | 39 | 24 | 6.6 (4.9 to 10) | z = 0.7789 P = 0.43 |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 1 | 257 | 37 | 17 | 6.2 (4.8 to 8.9) |

Subgroup analyses

Dose, route of administration and choice of antiemetic drug

No subgroup analysis was possible for dose, route of administration or choice of antiemetic drug, since all studies used aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg, all medication was administered orally, and the only antiemetic used was metoclopramide 10 mg.

Formulation: soluble versus tablet

For both pain-free (Analysis 1.5) and headache relief at 2 hours (Analysis 1.6) with aspirin alone versus placebo, there was no difference between soluble formulations (effervescent and mouth soluble) and tablets. There were insufficient data to investigate effect of formulation for other outcomes.

Monotherapy versus combination with an antiemetic

Results for aspirin alone compared with aspirin plus antiemetic (metoclopramide) are dealt with in the main analysis above.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis according to methodological quality was not possible because all studies scored ≥ 3 of 5 on the Oxford Qulaity Score.

Use of rescue medication

All studies asked participants whose symptoms were not adequately controlled to wait for 2 hours before taking any additional medication in order to give the test medication enough time to have an effect. Use of rescue or ‘escape’ medication (usually a different analgesic) after that time and up to 24 hours after dosing was reported in all studies and is a measure of treatment failure (lack of efficacy). In the study allowing multiple dosing for a single attack (Titus 2001), use of a second dose of study medication was interpreted as use of rescue medication for this analysis.

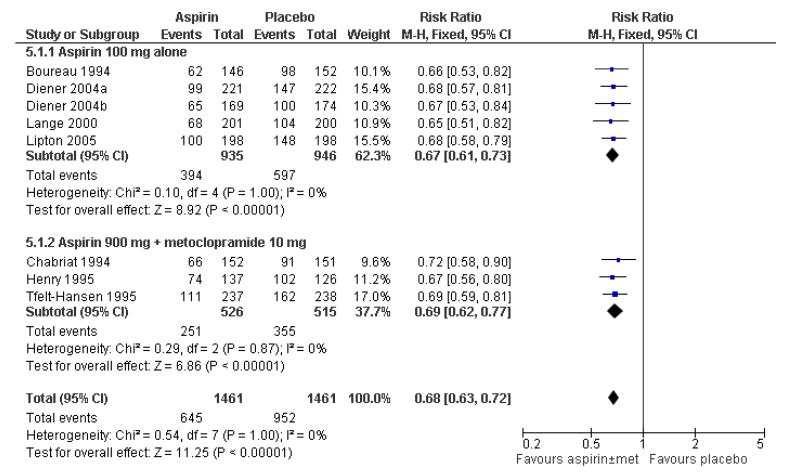

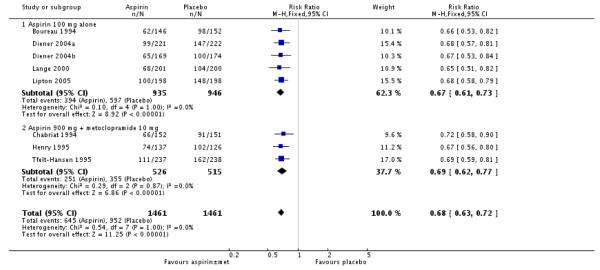

Aspirin with or without metoclopramide versus placebo

Eight studies (2922 participants) provided data for use of rescue medication with aspirin (with or without metoclopramide) versus placebo. The proportion of participants using rescue medication was 44% (645/1461; range 34% to 54%) with aspirin 1000 mg alone or aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg, and 65% (952/1461; range 52% to 81%) with placebo, giving an NNTp of 4.8 (4.1 to 5.7). In other words, for every five participants treated with aspirin, one would not require rescue medication who would have done with placebo. Separate analyses of aspirin alone and aspirin plus metoclopramide gave the same result (Figure 8; Summary of results B).

Figure 8.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Aspirin ± metoclopramide versus placebo, outcome: 5.1 Use of rescue medication.

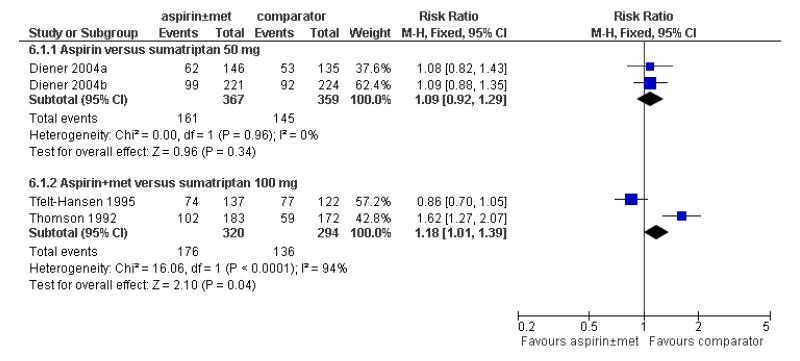

Aspirin with or without metoclopramide versus sumatriptan

Four studies (1340 participants) provided data for use of rescue medication in aspirin-treated participants versus sumatriptan-treated participants (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992). The proportion using rescue medication following aspirin alone or aspirin plus metoclopramide was 49% (337/687; range 42% to 56%), and following sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg was 43% (281/653; range 34% to 63%), giving an NNTp of 17 (8.8 to 140) in favour of sumatriptan. In other words, for every 17 participants treated with sumatriptan, one would not require rescue medication who would have done with aspirin. Only one study individually reported a statistically significant benefit for sumatriptan over aspirin in preventing the need for rescue medication (Thomson 1992). Analysing data for aspirin alone and aspirin plus metoclopramide did not affect the results (Figure 9; Summary of results B).

Figure 9.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Aspirin ± metoclopramide versus active comparator, outcome: 6.1 Use of rescue medication.

Aspirin with or without metoclopramide versus other active comparators

One study each reported on use of rescue medication for aspirin 1000 mg versus ibuprofen 400 mg (Diener 2004a, 432 participants), aspirin 1000 mg versus paracetamol 400 mg plus codeine 25 mg (Boureau 1994, 396 participants), aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus ergotamine 1 mg plus caffeine 100 mg (Le Jeunne 1998, 265 participants) and aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus ergotamine 2 mg plus caffeine 200 mg (Titus 2001, 227 participants). There were insufficient data for analysis.

Summary of results B.

Use of rescue medication

| Placebo comparators | Studies | Attacks treated | Treatment (%) | Comparator (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNTp (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (m± metoclopramide) versus placebo | 8 | 2922 | 44 | 65 | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.73) 4 | 8 (4.1 to 5.7) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 5 | 1881 | 42 | 63 | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73) | 4.8 (3.9 to 6.0) |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 3 | 1041 | 48 | 69 | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.77) | 4.7 (3.7 to 6.5) |

| Active comparators | Studies | Attacks treated | Treatment (%) | Comparator (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Aspirin (± metoclopramide) versus sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg | 4 | 1340 | 49 | 43 | 1.1 (1.01 to 1.3) | 17 (8.8 to 140) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 726 | 44 | 40 | 1.1 (0.92 to 1.3) | Not calculated |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 614 | 55 | 46 | 1.2 (1.01 to 1.4) | 11 (6.0 to 120) |

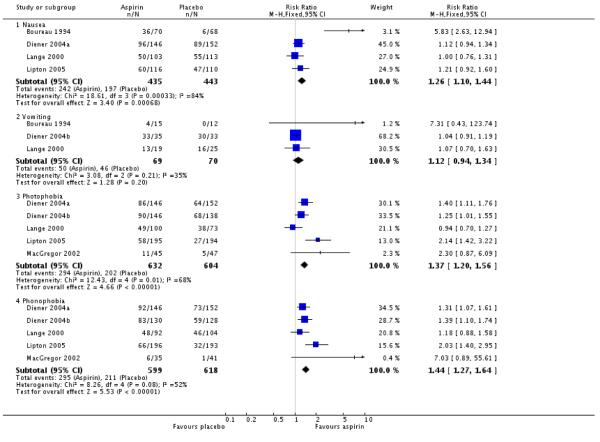

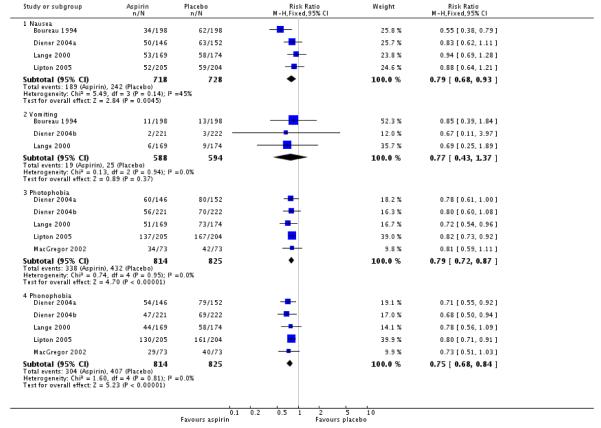

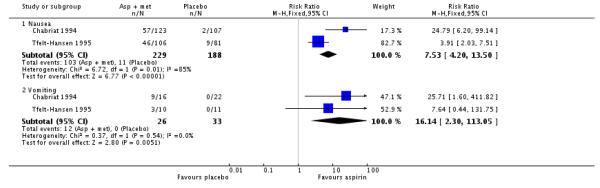

Relief of migraine-associated symptoms

In general, relief of migraine-associated symptoms (defined as a symptom reduction from moderate or severe to mild or none) was inconsistently reported. Of the eight studies that reported dichotomous data for symptom relief and comparing aspirin with placebo (Boureau 1994; Chabriat 1994; Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Lange 2000; Lipton 2005; MacGregor 2002; Tfelt-Hansen 1995), only one study provided data for all four symptoms of interest (Lange 2000). The 900 mg aspirin dose used in one study (MacGregor 2002) was assumed to have the same efficacy as 1000 mg aspirin. Although two studies with an aspirin plus metoclopramide treatment arm provided data for relief of nausea and vomiting (Chabriat 1994; Tfelt-Hansen 1995), there were no data available for the effects of this combination treatment on relief of photophobia and phonophobia (Summary of results C).

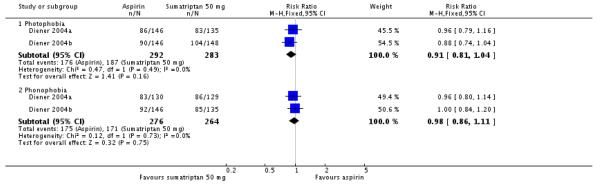

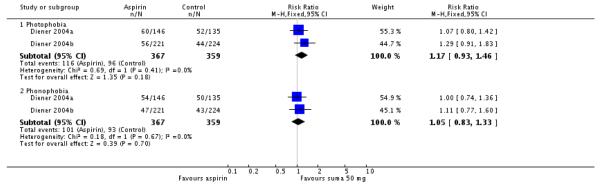

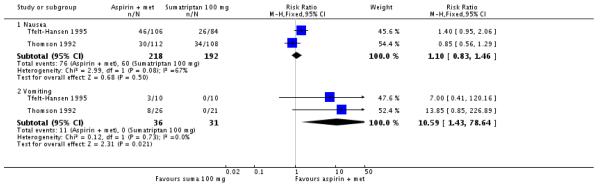

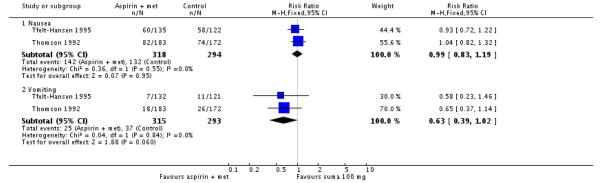

Two studies (Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992) provided data on relief of nausea and of vomiting for aspirin plus metoclopramide versus sumatriptan 100 mg, and two (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b) provided data on relief of photophobia and of phonophobia versus sumatriptan 50 mg.

Effects of treatment on relieving associated symptoms are presented in Summary of results C. Aspirin alone significantly relieved all symptoms except vomiting compared with placebo (Analysis 1.7), while aspirin plus metoclopramide significantly relieved both nausea and vomiting compared to placebo (Analysis 2.4). Subgroup analysis showed a statistically significant difference in favour of aspirin plus metoclopramide over aspirin alone for relief of nausea at 2 hours (z = 5.595, P < 0.00006), for relief of vomiting at 2 hours (z = 3.131, P = 0.002) and for reducing the presence of vomiting after 2 hours (z = 2.968, P = 0.003). Aspirin plus metoclopramide relieved more vomiting, but not nausea, compared to sumatriptan 100 mg (Analysis 4.3), while aspirin alone was not significantly different from sumatriptan 50 mg for relief of photophobia or phonophobia (Analysis 3.4).

Summary of results C.

Relief of associated symptoms 2 hours after taking study medication

| Intervention | Studies | Attacks with symptom present | Treatment (%) | Placebo (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | ||||||

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 4 | 878 | 56 | 44 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | 9.0 (5.6 to 22) |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 2 | 417 | 45 | 6 | 7.5 (4.2 to 14) | 2.6 (2.1 to 3.1) |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 410 | 35 | 31 | 1.1 (0.83 to 1.5) | Not calculated |

| Vomiting | ||||||

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 3 | 139 | 73 | 66 | 1.1 (0.94 to 1.3) | Not calculated |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 2 | 59 | 46 | 0 | 17 (2.3 to 120) | 2.1 (1.5 to 3.7) [12 events] |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 67 | 33 | 0 | 11 (1.4 to 78) | 3.3 (2.1 to 7.4) [11 events] |

| Photophobia | ||||||

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 5 | 1236 | 47 | 33 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 7.7 (5.4 to 13) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 575 | 60 | 66 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.03) | Not calculated |

| Phonophobia | ||||||

| Aspirin 1000 mg | 5 | 1217 | 49 | 34 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.7) | 6.6 (4.9 to 10) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 540 | 63 | 65 | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.1) | Not calculated |

Data from these studies were also analysed according to the persistence of associated symptoms 2 hours after treatment, and NNTps calculated. Aspirin alone significantly reduced the number of participants with nausea, photophobia or phonophobia, but not vomiting, compared with placebo (NNTps of 8 to 14), while aspirin plus metoclopramide significantly reduced the number of participants with nausea and with vomiting (NNTps of 7 to 13). There were no differences between aspirin alone and sumatriptan 50 mg for persistence of photophobia or phonophobia, or for aspirin plus metoclopramide and sumatriptan 100 mg for nausea or vomiting (Appendix 5).

Five studies compared aspirin to other active migraine treatments for relief of migraine-associated symptoms (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004b; Geraud 2002; Le Jeunne 1998; Titus 2001), but there were insufficient data for analysis.

Functional disability

Only one study with 73 participants reported data on functional disability (MacGregor 2002). More individuals with moderate or severe disability reported improvement following treatment with aspirin (22/53) than with placebo (3/61).

Repeat dosing for a single attack

Studies frequently reported use of rescue medication (usually as a different medicine from that under test). Two reported use of a second (repeat) dose of the medicine under test for treating the same attack. This is a potentially useful strategy for nonprescription medicines.

A second dose of study medication after 2 hours was used by just over half of each treatment group in Geraud 2002, either because pain was not relieved or because it returned. Headache relief at 2 hours following the second dose occurred in a similar proportion to that following the first dose, with no difference between aspirin plus metoclopramide and zolmitriptan. In the other study permitting a second or third dose of study medication to treat a single attack, just under half of each treatment group (aspirin plus metoclopramide and ergotamine plus caffeine) used a second dose, but no data were reported for our primary efficacy outcomes (Titus 2001).

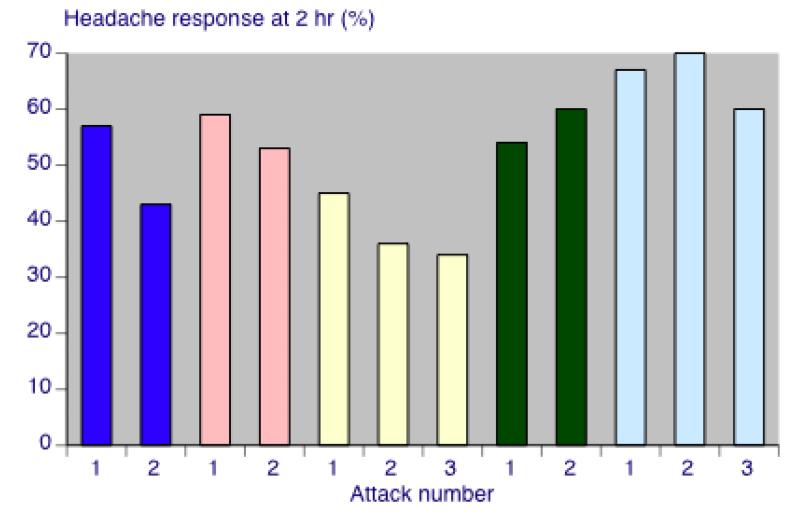

Multiple attacks

Response to therapy after a single migraine attack is useful knowledge, but migraineurs will suffer many attacks, and knowledge is needed about consistency of response. Few studies gave useful information on response in multiple attacks. However, five studies provided data for headache relief at 2 hours separately for two (Chabriat 1994; Le Jeunne 1998; Tfelt-Hansen 1995) or three (Geraud 2002; Thomson 1992) consecutive attacks treated with the same medication. Response rates either increased compared with the first attack by up to 9%, or decreased by up to 11%. There was no consistent pattern of change either within a treatment group (Figure 10) or between treatments (aspirin plus metoclopramide and control). All changes are within those that might be expected by the play of chance.

Figure 10.

Response rates for aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg in consecutive attacks, reported in five studies (from left:Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Chabriat 1994; Thomson 1992; Le Jeunne 1998; Geraud 2002)

Adverse events

For studies that treated more than one attack with a single medication, results for adverse events were usually presented for all treated attacks. These data have been included in the adverse event analyses in order to be more inclusive and conservative (Appendix 6).

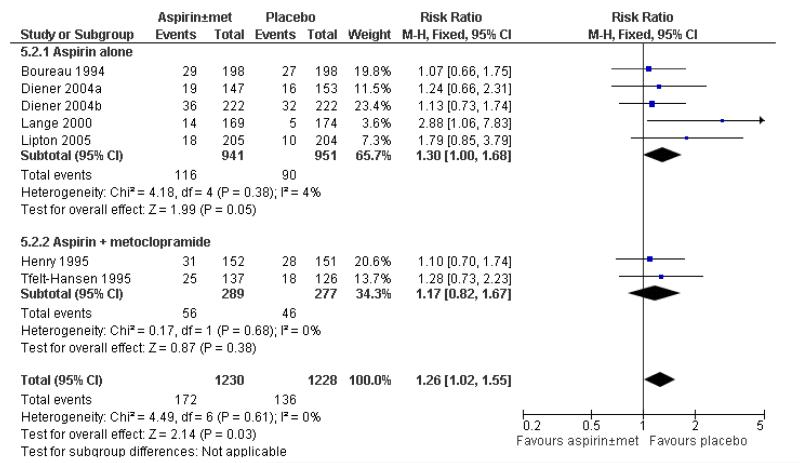

Any adverse event

All studies reported on the number of participants experiencing any adverse events after treatment; one, however, did not report data for each treatment group separately (MacGregor 2002). Most studies appeared to collect data using spontaneous reports in diary cards. Studies did not specify whether adverse event data continued to be collected after any rescue medication was taken; it seems likely that they were. Treatments were generally described as well tolerated, with most adverse events being of mild or moderate severity and self-limiting.

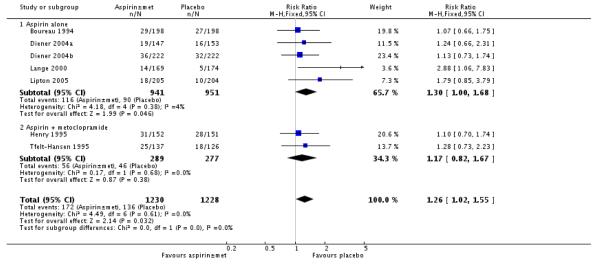

In total, five studies with 1892 participants provided data on the number of participants experiencing adverse events for aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b; Lange 2000; Lipton 2005), and two studies with 566 participants for aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide versus placebo (Henry 1995; Tfelt-Hansen 1995). Overall, adverse events occurred in 14% (172/1230) of aspirin (± metoclopramide)-treated participants, and in 11% (136/1228) of placebo-treated participants, giving a relative risk of 1.3 (1.02 to 1.6; Figure 11), and an NNH of 34 (18 to 340) (Summary of results D).

Figure 11.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Aspirin ± metoclopramide versus placebo, outcome: 5.2 Any adverse event within 24 hours.

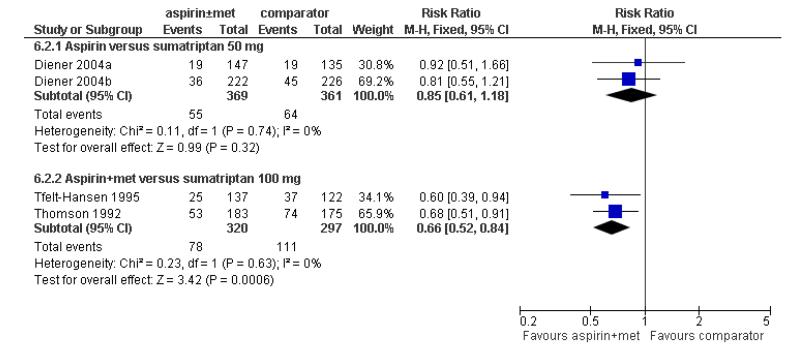

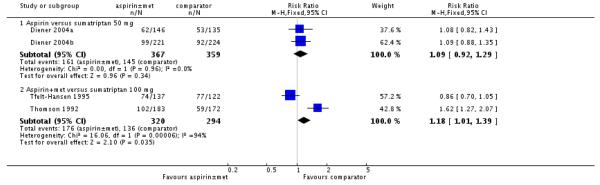

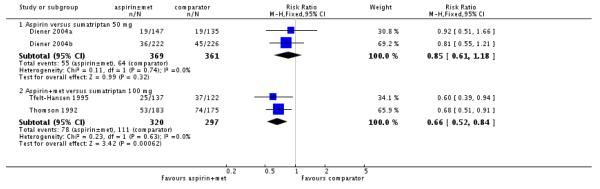

Two studies (730 participants) provided data for aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg (Diener 2004a; Diener 2004b); 15% (55/369) of aspirin-treated participants and 18% (64/361) of sumatriptan-treated participants experienced adverse events. There was no significant difference between the treatments. Two studies (617 participants) reported data for aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg compared with sumatriptan 100 mg (Tfelt-Hansen 1995; Thomson 1992); 24% (78/320) of aspirin-treated participants, and 37% (111/297) in sumatriptan-treated participants experienced adverse events, giving a relative risk of 0.66 (0.52 to 0.84; Figure 12), and an NNTp of 8.4 (5.3 to 21) (Summary of results D).

Figure 12.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Aspirin ± metoclopramide versus active comparator, outcome: 6.2 Any adverse event within 24 hours.

One study presented adverse events data for aspirin 1000 mg versus ibuprofen 400 mg (Diener 2004b), and another reported for aspirin 1000 mg versus acetaminophen 400 mg with codeine 25 mg (Boureau 1994). Two studies reported adverse event data for aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg compared with ergotamine 1 mg plus caffeine 100 mg (Le Jeunne 1998), or ergotamine 2 mg plus caffeine 200 mg (Titus 2001). There were insufficient data for analysis of this outcome for these active comparators (Appendix 6).

Overall, single doses of aspirin, with or without metoclopramide, did not cause significantly more or fewer adverse events in these studies than did placebo or comparator treatments, with the exception of sumatriptan 100 mg, where for every eight individuals treated with sumatriptan, one would experience adverse events who would not have done with aspirin plus metoclopramide.

Summary of results D.

Number of participants with adverse events within 24 hours of taking study medication

| More or no more adverse events with treatment than comparator | Studies | Participants | Aspirin (%) | Comparator (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin ± metoclopramide versus placebo | 7 | 2458 | 14 | 11 | 1.3 (1.02 to 1.6) | 34 (18 to 340) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus placebo | 5 | 1892 | 12 | 9 | 1.3 (1.00 to 1.7) | Not calculated |

| Aspirin 900 mg with metoclopramide 10 mg versus placebo | 2 | 566 | 19 | 17 | 1.2 (0.82 to 1.7) | Not calculated |

| Fewer adverse events with treatment than comparator | Studies | Participants | Aspirin (%) | Comparator (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNTp (95% CI) |

| Aspirin 1000 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 730 | 15 | 18 | 0.85 (0.61 to 1.2) | Not calculated |

| Aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg | 2 | 642 | 24 | 36 | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.84) | 8.4 (5.3 to 21) |

Specific adverse events

Detailed adverse event reporting was inconsistent. Some studies did not report any details of individual adverse events; others reported all adverse events for each treatment group; while others reported those occurring in, say, ≥ 2% of participants, or reported events for a specific body system. The body systems most frequently affected were the digestive system and nervous system. Individual studies were underpowered to detect differences between treatment groups, and inconsistent reporting prevented pooling of data (Appendix 6).

Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events were uncommon and were reported in only five studies. In one study a case of phlebitis following use of aspirin plus metoclopramide was considered to be drug-related, whilst another four events with aspirin plus metoclopramide and six with zolmitriptan were considered unrelated (Geraud 2002). In another study renal colic was reported in one participant after treating a migraine attack with aspirin, with no suspected causal relationship, but a perforated duodenal ulcer following use of ibuprofen was thought to be drug-related (Diener 2004b). In Lipton 2005, one participant had a perforated appendix following placebo treatment, and no causal relationship to the study medication was suspected. Acute atrial fibrillation requiring hospital admission was reported in one participant, and prolonged palpitations in another, after treatment with sumatriptan 100 mg (Tfelt-Hansen 1995). MacGregor 2002 reported two serious adverse events, considered unrelated to study medication: headache following treatment with aspirin and endometriosis following placebo. It is possible that these events were “severe” rather than “serious” (Appendix 6). Three studies that provided data for adverse events did not explicitly state whether any serious adverse events had occurred (Boureau 1994; Diener 2004a; Henry 1995).

Withdrawals

Withdrawals due to adverse events were reported in six studies (Appendix 6). Geraud 2002 reported five withdrawals following aspirin plus metoclopramide (diarrhoea, palpitations plus asthenia, anxiety plus dry mouth, phlebitis) and three following zolmitriptan (dizziness, somnolence, vasodilation). MacGregor 2002 reported four withdrawals following aspirin (nausea, tinnitus, coughing, taste perversion) and none with placebo. Le Jeunne 1998 reported one withdrawal due to pulmonary embolism following aspirin plus metoclopramide, and one due to back pain following placebo. Tfelt-Hansen 1995 reported one withdrawal following aspirin plus metoclopramide, four following sumatriptan, and one following placebo, with no details given. Thomson 1992 reported no withdrawals following aspirin, and five following sumatriptan (headache, faintness and vomiting; scalp tingling, heaviness in the chest, globus and prolonged aura; stomach pain; dyspnoea and heaviness; worsened headache and nausea). Titus 2001 reported one participant treated with aspirin plus metoclopramide who withdrew because of sinusitis.

Withdrawals for other reasons and exclusions for protocol violations or missing data were generally well reported, although it was not always clear whether they occurred before or after taking rescue medication. The numbers of withdrawals were not likely to affect estimates of efficacy or harm. No statistical analysis of withdrawals was carried out.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This review included 13 randomised, double-blind, controlled studies, with 4222 participants treating 5261 migraine headaches of moderate to severe intensity with either aspirin alone or aspirin plus metoclopramide. Nine of the studies were placebo-controlled; eight included an active comparator (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan, ibuprofen, paracetamol plus codeine, and ergotamine plus caffeine).

For the IHS preferred outcome of pain-free at 2 hours, both aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg alone and aspirin 900 mg plus metoclopramide 10 mg were better than placebo, with NNTs of 8 to 9, and no significant difference between active treatments. Only around one in four or one in five individuals treated with aspirin achieved this outcome. Sumatriptan 100 mg was significantly better than aspirin plus metoclopramide for this outcome (NNT = 10), but sumatriptan 50 mg was not different from aspirin alone. For headache relief at 2 hours, aspirin plus metoclopramide was significantly better than aspirin alone, with NNTs versus placebo of 3.3 and 4.9, respectively (P = 0.013). Around half of individuals treated achieved this outcome. There were no differences between aspirin alone and sumatriptan 50 mg, or aspirin plus metoclopramide and sumatriptan 100 mg. For headache relief at 1 hour, aspirin alone versus placebo gave a similar NNT to that at 2 hours (4.7). For sustained headache relief at 24 hours, aspirin alone was better than placebo (NNT = 6.6), as was the combination of aspirin plus metoclopramide (NNT = 6.2).

Fewer participants treated with either aspirin alone or aspirin plus metoclopramide than with placebo needed rescue medication (NNTp = 4.8). There was no difference for aspirin alone versus sumatriptan 50 mg for this outcome, but for aspirin plus metoclopramide versus sumatriptan 100 mg, the difference just reached statistical significance in favour of sumatriptan 100 mg (NNH = 11).

Both aspirin alone and aspirin plus metoclopramide were better than placebo for alleviation of migraine-associated symptoms, although there were too few vomiting events for reliable analysis, and no data for photophobia and phonophobia following aspirin plus metoclopramide. The combination therapy was significantly better than aspirin alone for relief of nausea (P < 0.00006), as might be expected for an antiemetic.

Overall, slightly more participants experienced adverse events with either aspirin alone or aspirin plus metoclopramide than with placebo, but the difference barely reached statistical significance. There were slightly more participants experiencing adverse events with sumatriptan than with aspirin, but the difference was statistically significant only for sumatriptan 100 mg versus aspirin plus metoclopramide (NNH = 8.4). Most adverse events were described as mild or moderate, and transient; digestive and nervous systems were most commonly affected. There were few serious adverse events, and most were not thought to be causally related to study medication, although one event of phlebitis was attributed to aspirin.

There were very limited data for aspirin with or without metoclopramide compared with other active comparators; there was no evidence for substantial differences between these interventions and aspirin for main efficacy outcomes in these studies. We did not include in this review studies where aspirin was used in combination with another analgesic.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Included participants all had a diagnosis of migraine according to IHS criteria, with attacks occurring at a frequency of one to six per month and of moderate to severe intensity. Studies did not specifically recruit participants who normally usually used OTC medications, although Lipton 2005 excluded those previously unresponsive to them. Participants requiring prophylaxis were either excluded or were able to continue with stable prophylaxis. The population studied is therefore not likely to be greatly biased towards milder or OTC-responsive individuals, or likely to exclude those with particularly difficult-to-treat headaches. Overall, there may be over-selection of individuals with more severe or difficult headaches than the general population since participants were recruited through headache clinics. Those with very frequent migraine attacks would be excluded, and this could include those whose headaches were regularly initially relieved, but then returned.

Most of the studies reported on most of the outcomes we considered important (Lipton 1999; IHS 2000), although some presented data in ways that prevented pooling (for example, no first attack data, but rather the sum, mean or range for ≥ 2 attacks). In general, the amount of missing data was small and unlikely to affect the results.

The amount of information for active comparators was small, so that even for sumatriptan conclusions about relative efficacy and harm must be cautious.

Individual studies are underpowered to determine differences between treatments for adverse events, and even pooling studies may not provide adequate numbers of events to demonstrate differences or allow confidence in the size of the effect. Single-dose studies are certainly unlikely to reveal rare, but potentially serious, adverse events. In these studies the number of participants experiencing any adverse event was probably a little higher with aspirin than with placebo, although these results may be confounded by recording of adverse events after taking rescue medication (which may disproportionately increase rates in the placebo group), and probably a little higher with larger doses of sumatriptan than with aspirin.

In the studies reviewed, participants with any contraindication to a study medication were excluded, so that the populations studied may differ from the general public who choose to self-medicate with OTC aspirin. In addition, some studies used buffered formulations of aspirin that may cause less irritation in the stomach than standard OTC aspirin.

We found no studies specifically investigating the early use of aspirin, alone or in combination with an antiemetic, while headache intensity was still mild. In clinical practice most migraine sufferers do not wait until the headache becomes moderate or severe, and there is some evidence from studies with triptans that treating early, or when pain intensity is still mild, is better (Gendolla 2008).

Quality of the evidence

Included studies were of good methodological quality and validity. None adequately described the method of allocation concealment, but this may reflect the limitation of space in published articles rather than any flaw in methodology. Migraine was diagnosed using standard, validated criteria, and outcomes measured were generally those recommended by the IHS as being of clinical relevance, although not all studies reported all the outcomes we sought.

Single-dose studies of a medication, or studies examining a single dose taken a few times, do not capture all adverse events that may occur with longer term use. While short-term use of aspirin probably does not pose a large problem (Steiner 2009), the potential for gastrointestinal harm with long-term use is well documented (Derry 2000).

Potential biases in the review process

The only area for concern is the small numbers of actual events used to calculate some results, particularly the small number of vomiting episodes in estimations of efficacy concerning relief of associated symptoms.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review is in broad agreement with earlier reviews comparing aspirin with placebo for acute migraine headaches (Diener 2006; Lampl 2007; Oldman 2002), but includes more studies. Other reviews comparing aspirin with triptans also agree that aspirin has similar efficacy to oral sumatriptan (Mett 2008; Tfelt-Hansen 2008). Our findings are also consistent with recently published guidelines from the European Federation of Neurological Societies on drug treatment of acute migraine headaches (Evers 2009).

A recent review of adverse events associated with single doses of aspirin in trials in migraine or tension-type headache or postoperative dental pain suggests that any small increases in gastrointestinal adverse events compared with placebo are not great enough to drive choice of drug therapy (Steiner 2009). We also found a small increase in mostly mild and transient adverse events with aspirin, suggesting good tolerability among the participants recruited into these studies.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Aspirin 900 mg or 1000 mg is an effective treatment for acute migraine headaches, with participants in these studies experiencing reduction in both pain and associated symptoms, such as nausea and photophobia. The addition of 10 mg metoclopramide may provide additional pain relief and greater reduction in associated symptoms, particularly nausea. There was a small increase in the number of adverse events compared to placebo, but most events were mild and transient. Oral sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg provided similar efficacy (although sumatriptan 100 mg was superior to the aspirin/metoclopramide combination for pain-free at 2 hours), but with slightly increased adverse events for sumatriptan 100 mg. Aspirin plus metoclopramide would seem to be a good first-line therapy for acute migraine attacks in this population, though long-term use brings higher risk of harm. Those who did not experience adequate relief could try an alternative therapy.

Implications for research

Further studies are needed to establish the efficacy of aspirin compared to other triptans and NSAIDs. Ideally these studies would be head-to-head comparisons and would include a placebo comparator for internal validity.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Aspirin with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults

A single oral dose of 1000 mg of aspirin is effective in relieving migraine headache pain and associated symptoms (nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia). Pain will be reduced from moderate or severe to no pain by 2 hours in approximately 1 in 4 people (24%) taking aspirin, compared with about 1 in 10 (11%) taking placebo. Pain will be reduced from moderate or severe to no worse than mild pain by 2 hours in roughly 1 in 2 people (52%) taking aspirin compared with approximately 1 in 3 (32%) taking placebo. Of those who experience effective headache relief at 2 hours, more have that relief sustained over 24 hours with aspirin than with placebo. Addition of 10 mg of the antiemetic metoclopramide substantially increases relief of nausea and vomiting compared with aspirin alone, but makes little difference to pain.

Oral sumatriptan 100 mg is better than aspirin plus metoclopramide for pain-free response at 2 hours, but otherwise there are no major differences between aspirin with or without metoclopramide and sumatriptan 50 mg or 100 mg. Adverse events with short-term use are mostly mild and transient, occurring slightly more often with aspirin than placebo, and more often with sumatriptan 100 mg than with aspirin.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, double-dummy, three-period, cross-over. Single oral dose of each treatment for each of three migraine attacks Assessments at 0 and 2 hours. If pain not controlled, participants asked to wait 2 hours before taking rescue medication |

|

| Participants | Aged 18-65 years, meeting IHS criteria for migraine without aura. At least 12-month history of migraine, with age of onset before 50 years and two to six attacks permonth. Prophylaxis permitted if stable for ≥ 2 months Excluded participants with other types of headache. Included participants with ‘slight’ migraine at baseline, but reported primary outcomes for those with ≥ moderate pain separately N = 247 (198 treated three attacks and analysed for efficacy) M = 57, F = 190 Mean age = 40 years 36.8% of randomised participants were taking prophylactic therapy |

|

| Interventions | Aspirin 1000 mg, n = 198 Acetaminophen 400 mg plus codeine 25 mg, n = 198 Placebo, n = 198 |

|

| Outcomes | Headache relief at 2 hours Pain-free at 2 hours PI: 100 mm VAS Mean PID at 2 hours (from baseline) Relief of nausea and vomiting Use of rescue medication Patient preference for medication Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Double-dummy design |

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group. Single oral dose per attack. Participants treated two migraine attacks Medication taken when migraine headache pain of moderate or severe intensity Assessments at 0 and 2 hours. If pain not controlled, participants asked to wait 2 hours before taking rescue medication |

|

| Participants | Aged 18-65 years, meeting IHS criteria for migraine with or without aura. At least 12-month history of migraine, with two to six attacks per month for three months prior to inclusion in study. Prophylaxis permitted if stable for ≥3 months Excluded participants whose migraine headache was never accompanied by nausea or vomiting N = 266 (250 analysed for efficacy, 16 did not take medication) M = 46, F = 220 Mean age 37 years |

|

| Interventions | Lysine acetylsalicylate 1650 mg (equivalent to 900 mg aspirin) plus metoclopramide 10 mg, n = 126 Placebo, n = 124 |

|

| Outcomes | Headache relief at 2 hours Pain-free at 2 hours PI: 4-point scale Presence of nausea and vomiting Headache recurrence at 24 hours PGE: 4-point scale Use of rescue medications |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not described |

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, three-arm, parallel-group, double-dummy. Single oral dose Medication taken when migraine headache pain of moderate or severe intensity Assessments at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 and 24 hours. If pain not controlled, participants asked to wait 2 hours before taking rescue medication |

|

| Participants | Aged 18-65 years, meeting IHS criteria for migraine with and without aura. At least 12-month history of migraine, with one to six attacks per month N = 433 M = 66, F = 367 Mean age 42 years |

|

| Interventions | Effervescent acetylsalicylic acid 1000 mg, n = 146 Sumatriptan 50 mg, n = 135 Placebo, n = 152 |

|

| Outcomes | Headache relief at 1 and 2 hours Pain-free at 2 hours 24-hour sustained relief Adverse events Remission of associated symptoms: nausea, photophobia, phonophobia Overall impression of study medication Need for rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Computer-generated randomisation list” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “Matching effervescent or tablet placebo” |

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-fold cross-over, double-dummy. Single oral dose per attack. Each participant treated three migraine attacks with different treatments Medication taken when migraine headache pain of moderate or severe intensity Assessments at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 and 24 hours. If pain not controlled, participants encouraged to wait 2 hours before taking rescue medication Participants instructed to leave a minimum of 48 hours between consecutive study treatments to ensure that new attack and not migraine recurrence was being treated |

|

| Participants | Aged 18-65 years, meeting IHS criteria for migraine with and without aura. At least 12-month history of migraine, with one to six attacks per month N = 312 M = 59, F = 253 Mean age 38 years |

|

| Interventions | Effervescent acetylsalicylic acid 1000 mg, n = 222 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 212 Sumatriptan 50 mg, n = 226 Placebo, n = 222 |

|

| Outcomes | Pain intensity at 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2 hours Nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia at same time points Global assessment of medication on 4-point categorical scale Use of ‘escape medication’ Time when headache disappeared Recurrence within 24 hours Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Treatment was assigned by a predetermined randomisation code” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Double dummy design |

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, double-dummy. Single oral dose Each participant treated three migraine attacks. Medication taken when migraine headache pain of moderate or severe intensity, provided it was within 6 hours of headache onset, and participants had been free from any previous migraine attack for at least 24 hours Assessments at 0 and 2 hours. If pain not controlled, participants encouraged to wait 2 hours before taking rescue medication Patients returned to study centre after treating first attack, and were then given medication and diary cards for treating two further attacks |

|