Abstract

Despite major improvements over the past several decades, many patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) continue to suffer from significant treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Clinical research studies (trials) have been integral to advancing the standard-of-care in HSCT. However, one of the biggest challenges with clinical trials is the low participation rate. While barriers to participation in cancer clinical trials have been previously explored, studies specific to HSCT are lacking. The current study was undertaken to examine the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of HSCT patients regarding clinical trials. Using focus groups, participants responded to open-ended questions that assessed factors influencing decision-making about HSCT clinical trials. Suggestions for improvements in the recruitment process were also solicited among participants. Seventeen adult HSCT patients and six parents of pediatric HSCT patients participated in the study. The median age was 56 years (range, 18-70) and 44 years (range, 28-54) for adult patients and parents, respectively. Participants universally indicated that too much information was provided within the informed consents and they were intimidated by the medical and legal language. Despite the large amount of information provided to them at the time of study enrollment, there was limited knowledge retention and recall of study details. Nevertheless, participants reported overall positive experiences with clinical trial participation and many would readily choose to participate again. A common concern among participants was the uncertainty of study outcome and general lack of feedback about results at the end of the study. Participants suggested that investigators provide more condensed and easier-to-understand informed consents and follow-up of study findings. These findings could be used to help guide the development of improved consent documents and enhanced participation in research studies, thereby impacting the future design of HSCT research protocols.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a high-risk medical procedure that is utilized worldwide as therapy for many malignant and non-malignant hematologic diseases.1,2 The number of autologous and allogeneic transplants performed continues to rise,3 particularly as outcomes have significantly improved over the past few decades.4 Clinical research has played an important role in advances of standard-of-care seen in HSCT patients over time,5,6 which has led to improved supportive care, better understanding of disease risks, and newer treatment approaches.4 Nonetheless, efficacy is still limited by short and long-term treatment-related complications.1 Clinical research remains crucial in guiding more effective diagnostic and treatment options.7

Clinical research has been broadly defined by the Institute of Medicine to “include all studies intended to produce knowledge valuable to understanding the prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, or cure of human disease.”8 The translation of basic science advances into human applications provides the opportunity to test hypothesis-driven questions, investigate new therapies, and evaluate outcomes in efforts to improve overall health care.9 However, one of the biggest challenges is that very few patients enter clinical research studies (trials). For example, only 3% of U.S. adults with cancer participate in clinical trials.7,10 Barriers to enrollment in patients undergoing HSCT are additionally magnified due to the small pool of patients undergoing transplants at most centers, substantial heterogeneity of diseases treated, donor and recipient characteristics, and sources of hematopoietic stem cells, as well as heterogeneity of transplant techniques.5 The consequences of poor recruitment or slower than anticipated enrollment into clinical research studies include premature closure, underpowered results, lack of generalizability, and wasted resources.11 While studies have explored barriers to participation in cancer clinical trials, identifying common themes across studies has been challenging.12 Further, studies specific to HSCT are lacking.5 Gaps in knowledge remain regarding patient-centered perspectives in HSCT clinical trials. Moreover, relatively little has been published on how to recruit patients for HSCT clinical trials.

Given the growing importance of patient engagement in clinical and translational research,13,14 we sought to identify knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of participation in clinical research studies among adult HSCT patients and parents of pediatric HSCT patients. The purpose of our study was to examine patient-centered barriers, facilitators, and motivations regarding clinical research studies in order to develop a questionnaire targeted at the HSCT population. By investigating patient-centered attitudes and perceptions, the new information gained may improve the future design of HSCT clinical research protocols and improve participation into HSCT clinical trials.

Methods

Empirical Setting

A distinguishing feature of the University of Michigan Blood and Marrow Transplantation (BMT) Program is the integration of the Adult and Pediatric BMT Units to promote clinical and translational research. The inpatient and outpatient units for the Adult and Pediatric BMT Programs are co-located in the Children's and Women's Hospital. The Adult and Pediatric BMT Programs have over 6,000 annual outpatient visits, evaluate over 400 new HSCT patients, and perform approximately 250 HSCT each year (200 adult HSCT and 50 pediatric HSCT). This includes approximately 70 allogeneic HLA-identical sibling donor and 70 unrelated donor HSCT. It is standard practice for HSCT eligible patients to consent to usual care procedures concurrently with as many clinical research studies as possible, including sample repository, ancillary, supportive care, and intervention studies, prior to admission to the BMT Unit.

Focus group recruitment

We sought participants who had recently undergone autologous or allogeneic HSCT. Adult post-HSCT patients (age ≥ 18 years) and parents of pediatric post-HSCT patients (age < 18 years) were eligible to participate in the focus groups. Patients were not required to have previously enrolled in a specific clinical trial. Inclusion criteria required ability to speak and read proficiently in English and ability to travel off-site to a facility on the University of Michigan Main Campus. Participants were recruited in the outpatient setting through Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved flyers posted in the BMT Program waiting rooms or attached to patient clipboards during clinic check-in. BMT physicians, advanced practice extenders, and staff assisted with recruitment.

Interested patients/parents were instructed to call a telephone number and sign-up for one of three focus groups (FG1, FG2, and FG3). After answering a short screening questionnaire over the phone, participants received an information package including a cover letter confirming their participation, a map with driving directions to the focus group location, and a consent form to which they could reply via mail or email. Participants received a telephone call reminder on the day prior to the scheduled focus group.

Participants of FG1 and FG2 received $50 as compensation for participation. To encourage participation among parents for FG3, compensation was increased to $100. Participants were reimbursed for metered parking during the time of the focus group. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School IRB (HUM00078723: “Attitudes and perceptions of participation in BMT clinical trials”).

Focus groups

Three focus groups were conducted between September and October 2013. Upon arrival to the focus group site, participants signed the consent form and filled out a brief questionnaire that collected information on socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. No patient identifiers were retained. Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes, and was audio/video-recorded with consents provided by the participants.

A trained focus group moderator with a background in public health and an assistant moderator with a background in survey methodology, neither affiliated with the BMT Program, moderated all three focus groups. Researchers from the BMT Program attended the sessions and observed the discussions behind a one-way mirror. Prior to the initiation of the study, a focus group guide had been developed by the study investigators, who included experts in HSCT and survey methodology, through a literature review on studies about motives for cancer clinical research participation and through the conduct of semi-structured qualitative interviews with BMT physicians, advanced practice extenders (e.g., nurse practitioners and physician assistants), nurse coordinators, social workers, nutritionists, pharmacists, and nurses. The moderators used the guide to cover questions on (1) free associations with the term “clinical trial.” The term “clinical trials” was used interchangeably with “clinical research studies”; (2) perceptions of information flow (i.e., process of recruitment) regarding HSCT trials; (3) the decision making process for participation in an HSCT clinical trial; (4) general reasons for and against participation in clinical trials; (5) personal experiences with clinical trials; and (6) suggestions for changes in the HSCT clinical trial process at the University of Michigan Health System (Table 1 provides details of the moderator guide questions). The last topic was added to the guide for FG2 and FG3 based on comments from participants in FG1.

Table 1. Moderator guide questions.

| Free associations with term “clinical trial” |

| When you hear the word, “clinical trial” what is the first thing that comes to your mind? |

| Perceptions of information flow regarding HSCT clinical trials |

| Now I'd like you to think back to the time when you had the bone marrow transplantationa at the University of Michigan, or your child had the bone marrow transplantation. Who presented the trial to you, who talked to you about the trial? |

| How many trials were you offered, or presented? What kind of trials were you offered? |

| When the person talked to you about the trial, whether it was the doctor or the clinical coordinator, what did they say about it? What information did they give you? |

| Did anyone have the feeling that they were given too much information, or not enough information? |

| After learning about the BMT trial, or the trials that you participated in, did you actively look for more information about it? |

| Decision making process for participation in an HSCT clinical trial |

| Do you remember your first thoughts when you heard about the BMT trial at the U of M Hospital? |

| When it came to making a decision whether to participate in the BMT trial or not, did you make the decision alone, or did someone else influence or talk with you before you made the decision? |

| Reasons for and against participation in clinical trials |

| What are reasons to participate in a clinical trial? |

| What are reasons not to participate in a clinical trial? |

| Personal experiences with clinical trials |

| Now thinking back to the BMT trial that you participated in at the U of M hospital, what were your experiences with these BMT trials? |

| Looking back and comparing your expectations before the start of the trial with what actually happened during the trial, to what extent were your expectations met. Was there anything that happened that was different than you were expecting? |

| Thinking back to the overall experience that you had with the clinical trial, as part of your BMT at the U of M hospital, if you would have to make the decision about participating in a clinical trial again, how willing would you be to participate in the same trial again? |

| Now imagine that a good friend or close relative comes to you tomorrow and tells you that he or she was offered to participate in a clinical trial as part of a BMT. What would you say to him or her? |

| Suggestion for changes in the HSCT clinical trial process at the University of Michigan Health System |

| Thinking back to the BMT trials at the UM hospital. Is there anything that you would like to change? |

To facilitate patients' and parents' understanding in the focus groups, the more colloquial terms “bone marrow transplantation” and “BMT” were used instead of “hematopoietic stem cell transplants” and “HSCT”.

Data analysis

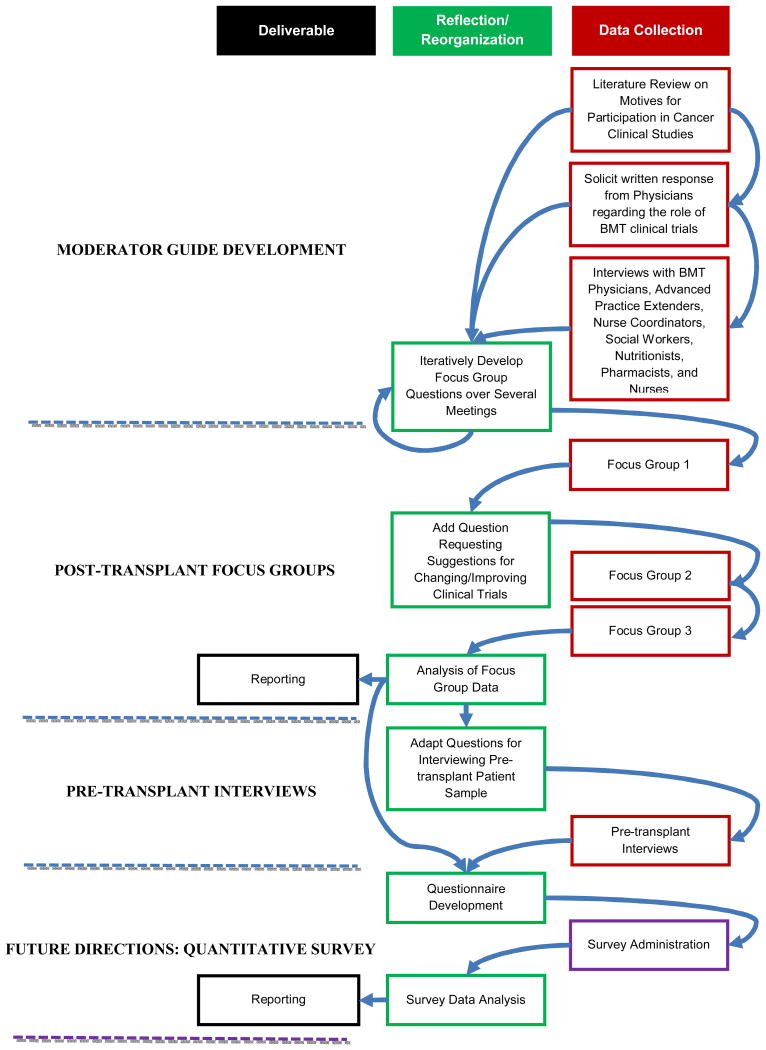

Focus group recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were systematically analyzed in multiple steps using content analysis by hand and computer-assisted qualitative data analysis to uncover common themes pertaining to patient and parent attitudes and perceptions of HSCT clinical research studies. The analysis approach included three steps, as previously described:15 1) three researchers (FK, LC, and SWC) independently read the transcripts and generated codes for the range of responses. Codes were then refined, verbally defined, and a code frame was developed using an iterative process based on discussions among the entire group; 2) the three raters coded all transcripts independently, compared codes, and resolved disagreements by consensus; and 3) one member of the research team (FK) used ATLAS.ti V7 (Berlin, Germany; http://www.atlasti.com/index.html) to apply the codes to the transcript and to create frequency tables of themes used by focus group participants. The entire study team reviewed the results and validated the interpretations and conclusions in a final peer-debriefing session (Figure for the iterative loop of qualitative data collection).

Figure. Iterative Loop of Research Methodology.

Results

Study characteristics

Twenty-five subjects expressed interest in joining a focus group, which included 19 adult HSCT patients and six parents of pediatric HSCT patients. However, two were ultimately unable to join a focus group due to conflicting BMT clinic appointments, leaving 23 individuals enrolled. Participants included 17 adult HSCT patients and 6 parents of pediatric HSCT patients (e.g., one mother or father for each pediatric patient) with a total of four mothers and two fathers. FG1 included seven adult patients and two parents of pediatric patients; FG2 included eight adult patients only; and FG3 included four parents of pediatric patients and two young adult patients (age > 18 years) who were both treated in the Pediatric BMT Unit.

The median age of adult HSCT participants was 56 years (range, 18–70), comprised predominantly of males (n=13); the median age of parent participants was 44 years (range 28–54), comprised predominantly of females (n=2; Table 2). The majority of adult HSCT patients were currently not employed. Most participants (adult HSCT patients and parents) came from Southeast Michigan, the primary catchment area served by the University of Michigan Health System. The median time from HSCT to the focus group was 18 and 19 months for adult patients and parents, respectively. Additional characteristics of the study population (adult HSCT patients and pediatric patients represented by their parents) are provided in Table S1.

Table 2. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Adult patients n=17 |

Parents of pediatric patients n=6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years: median (range) | 56 | (18-70) | 43.5 | (28-54) |

| Gender: n (%) | ||||

| Male | 13 | (76.5) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Female | 4 | (23.5) | 4 | (66.7) |

| Hometown: n (%) | ||||

| Ann Arbor and other Washtenaw county | 5 | (29.4) | 1 | (16.7) |

| Other Southeast Michigan | 10 | (58.8) | 5 | (83.3) |

| Other | 2 | (11.8) | 0 | (0) |

| Household income: n (%) | ||||

| Under $50,000 | 7 | (41.2) | 2 | (33.3) |

| $50,000-99,999 | 4 | (23.5) | 1 | (16.7) |

| $100,00+ | 5 | (29.4) | 3 | (50) |

| N/A | 1 | (5.9) | 0 | (0) |

| Employment status: n (%) | ||||

| Full time | 1 | (5.9) | 1 | (16.7) |

| Part time | 4 | (23.5) | 3 | (50) |

| Not employed | 12 | (70.6) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Healthcare coverage: n (%) | ||||

| Private | 5 | (29.4) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Employer sponsored | 7 | (41.2) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 4 | (23.5) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Other | 1 | (5.9) | 0 | (0) |

| Time since HSCT in months: median (range) | 18 | (2-53) | 19 | (4-44) |

HSCT=hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Free associations: “clinical trial”

Participants were asked to think about the term “clinical trial” and state whatever came to mind (Table 3 for representative answers to the focus group questions). Most associations coming from adult HSCT patients concerned the uncertainty of the outcome of clinical trials (Table S2). In general, positive comments about research, altruism and personal benefits gained through trial participation were mentioned frequently by adult patients. On the contrary, parents of pediatric patients most often made neutral comments about research followed by associations concerning desperation. Additionally, both adult patients and parents mentioned the uncertainty associated with clinical trial outcomes and general concerns with participation in trials, providing comments such as “guinea pig,” “lab rat,” and “we are one step above the mice.”

Table 3. Representative participant responses to focus group questions.

| Free associations with term “clinical trial” |

| “It's a trial because it's a trial. It might not help me.” (AP) |

| “New medicine, new techniques.” (AP) |

| “Doing something that might help people further down the line.” (AP) |

| “I would just say medicine.” (P) |

| “Life-saving.” (P) |

| “Raises a red flag to me.” (P) |

| Perceptions of information flow regarding HSCT clinical trials |

| “The coordinator nurse. I can remember her face but not her name. She was the coordinator before I had my transplant. Then he [doctor] talked about it.” (AP) |

| “I have to be honest, I have no idea if I was in a trial or not. I was so sick. If I was signing stuff, I couldn't tell you. I had no idea.” (AP) |

| “They talked about that it was going to help research on down to different drugs that they were going to try and that I could help people in the future, and it was going to be no extra doctor visits…It didn't affect me…Just extra vials of blood…And you had to pee.” (AP) |

| “I had blood, urine, bone marrow. And then the aspiration of part of it. And I did some trials for some therapies for Graft Versus Host Disease medicine. And I'm not sure at one point there was some other medicine that I tried too. My memory's blurry so I'm all…” (AP) |

| “I know we did the research blood. I don't remember how many.” (P) |

| “I also think that at the time when they're presenting the stuff and you're signing the papers saying “Oh research! Yes, absolutely. You can do this.” But there was so much more going on per se in our life at that time.” (P) |

| “I don't think my son was in a trial because my daughter was a 100 percent match. So I don't think that we did a trial. I think it was just a regular bone marrow transplant.” (P) |

| “They said that it would be used only for that reason and everything remains confidential---They won't be using it for any other purpose than what the trial said in the paperwork…And it was voluntary. You didn't have to participate.” (P) |

| “Too much. Papers after papers…Just sum it up.” (AP) |

| “It's a ten page packet and every page is practically the same and you get to the side effects? I'm sorry. I'm sure that this has to do more with liability than anything.….Literally every possible thing that you could consider as a liability is listed there….So, you don't really know… What could possibly be a side effect because everything, whether it's a drug or whether it's a clinical trial, they all put every possible side effect down and it's like forget it.” (AP) |

| “By being informed it also gives you something to occupy your mind when you---So much is going through your head.” (AP) |

| Decision making process for participation in an HSCT clinical trial |

| “There's basically no question about it.…Yes, it's something that they could do without even affecting your life or the outcome of the thing.” (AP) |

| “I was actually eager to help…because I just wanted to give back somehow.” (AP) |

| “I just didn't want too many other people influencing my decision…At the end of the day, I just want to make sure that I was happy with the decision that I was going to make.” (AP) |

| “My son is eight but my wife and I have involved him in the decision making process through every aspect of this journey. So he was involved in everything. His signature is on all of the stuff. Even though it was not legally binding but he signed all his paperwork too.” (P) |

| Reasons for participation in clinical trials |

| “My first one is just because of my survival, and number two is to help further others in their treatment. Then, my biggest one is “science versus myth.”” (AP) |

| “I wrote to contribute to the science and benefit others with improved protocols, to possibly benefit my own recovery, and to potentially save my own life, worst case scenario.” (AP) |

| “I'm very tied to this university. This is my school, this is my life, this is who I am so I really wanted to help the University of Michigan and I wanted to help them innovate more above other schools, which I think is very important to being a Wolverine.” (AP) |

| “Access to curative medicine not otherwise available. More eyes on labs. And more labs per blood draw… Ability to help others.” (P) |

| “To save my son, to cure his leukemia. Good information on the bone marrow transplant and successful stories.” (P) |

| Reasons against participation in clinical trials |

| “I'd be less likely to if it required extra clinic visits, and if it sounded dangerous, and if it was something that may make my condition worse.” (AP) |

| “I have the fear of failure, the loss of life, and possible waste of time, and negative repercussions.” (AP) |

| “If there was a level of distrust. If you have a level of distrust with the program or the doctor that you're with, you're less likely to… This is another thing, they may throw things at you. |

| “Just sign this, we're going to do this, bla-bla-bla,” reasons in the paperwork not clear enough, not explained fully. I would really go, “Hmm, who are they doing this for? Me or them?”” (P) |

| “Risk, faster demise, more pain. More time away from family potentially. More doctors in the room during inpatient time.” (P) |

| Personal experiences with clinical trials |

| “I don't really have anything particularly memorable. It's just stuff…I don't know…Because I don't remember. Maybe there were some extra tests, I'm not sure.” (AP) |

| “I didn't affect us at all. We saw nothing except for a few extra vials of blood taken every so often.” (P) |

| “And cupfuls and cupfuls of pills, plus IVs. The clinical trial pills got tedious. After a while I was going, “Oh, not another one.” On an empty stomach, that kind of thing.” (AP) |

| “Okay, I did this, but now what? Did it help? Was it worth it? What did it prove?” (AP) |

| Suggestion for changes in the HSCT clinical trial process at the University of Michigan Health System |

| “I don't even know if mine is over yet, the study I was in, if they're still doing it, but I would love to get, as a member of the study, when the study results are done, get notification of the outcome of the study…What's going on? I volunteered and then they shut you out.” (AP) |

| “We're a litigious society. I understand that you need me to sign this contract or…A summary. Yes, summarize it….Give me the honest scoop of it. If you list 100 different side effects because they're all possibilities and you've got to cover yourself for legalism, that's fine, but be…I need somebody to tell me which of these things am I really likely to get or what's most probable?” (AP) |

| “But there was so much going on per se in our life at that time. I don't specifically remember them saying. ‘This is what this is and here's a piece of paper telling you…’ …I think that would have been helpful.” (P) |

| “I felt like there were some times where I felt like it was when I would be with my older siblings and they would be like, “Yes, eat the worm, it's totally fine,” and try to convince me to do something that they would get amusement out of.” (AP) |

AP = adult patient; P = parent of pediatric patient

Perceptions of information flow regarding HSCT trials at University of Michigan Health System

Participants were then asked to think back to the time when they or their children were admitted for the HSCT procedure and report whether they were asked to participate in any clinical research studies and, if so, who asked them to participate. Although almost all participants remembered being asked to participate in multiple studies by either their primary BMT physician or a BMT nurse coordinator, both adult patients and parents of pediatric patients expressed recall difficulty when asked about what specific studies were offered and what information was presented. In general, studies involving patients to provide extra blood and urine samples were remembered most often. For other types of studies, most participants could cite broad categories, such as “GVHD-related” trials or studies involving “genetics,” without recalling specific details. A few participants were not sure whether they participated in any studies (even though they had) or had problems drawing a clear distinction between the clinical research studies and the HSCT procedure itself.

When asked what the person who presented the trial told them about the study, participants remembered mainly general information on research, confidentiality, and anonymity or information about the low-risk or tangential nature of the study (i.e., blood draws for correlative laboratory studies). No participants reported having received financial compensation for their participation in clinical research studies.

Many participants expressed that they were inundated with too much information and intimidated by details on side effects and the medical and legal language used in the consent process. Other participants expressed that they appreciated all the information they received to ensure that they were well-informed. Some participants reported to have actively searched for more information; however, most of the search activities pertained to the HSCT itself and not the trial.

Decision making process

Almost all participants reported that making the decision about participation in the clinical research study was easy and fast, mainly because they had the feeling that the studies were low-risk, in general, and did not require additional effort apart from the usual care of the HSCT procedure itself. A majority of patients considered participation as “little or no extra burden.” Additionally, altruism appeared to play a major role for many participants in making a fast decision.

Adult patients made the participation decision with their spouses or alone, because they did not want to be influenced by others. Parents of pediatric HSCT patients reported making the decision about participation together with their spouses and some also involved their children.

Reasons for and against participation in clinical trial

Focus group participants were asked to list up to three reasons for and three reasons against participation in a clinical study on an index card and then share their reasons with the group. The main reasons for participation cited by adult patients were altruism and personal benefits gained through participation (Table S3). Other reasons reported by adult patients involved the advancement of research, the search for answers about their disease, and also institutional pride toward the University of Michigan. Parents of pediatric patients most often reported advancement of research and altruism.

In terms of reasons for not participating in clinical research studies, both adult patients and parents of pediatric patients reported the fear of personal harm most often (Table S4). Additionally, many adult patients mentioned uncertainty about the trial outcome and extra burden, such as more visits to the hospital, as reasons for non-participation. Parents also mentioned that distrust in a program or its doctors would hold them from participating in a clinical research study.

Personal experience with clinical research studies

When asked about their personal experience with participating in a HSCT research study, participants overall were positive. Many participants stated that the studies were low-risk and did not leave much of an impact on them. Again, some participants expressed recall difficulties about specifics of the study. Only a few participants remembered side effects and extra pain stemming from the studies. A common concern among several participants, both adult patients and parents of pediatric patients, pertained to the uncertainty about the outcome of the study and the lack of feedback patients received once they enrolled and completed the study. Almost all participants said that they would participate again in a clinical research study. In addition, when asked whether they would recommend others, such as friends and family, who were in the same situation to participate in a clinical study, there was strong support for doing so. However, many participants stressed the importance of being informed about the details of the study and being provided with ample opportunity to ask questions.

Suggestions for changes in HSCT clinical trial process

Focus group participants were asked whether there was anything that they would like to change in the process of HSCT clinical research studies at the University of Michigan Health System. Again, many participants criticized the general lack of feedback once a study had started. Additionally, many participants repeated their concerns about the amount of paperwork and the scientific and legal language involved in the consent process. Some participants suggested that investigators provide more condensed and personalized information and that the information could be presented in a digital format, such as in an electronic application or a tab on the patient online portal. Finally, some adult patients felt somewhat pressured by their physicians to participate in certain clinical research studies.

Discussion

In this study, the majority of participants recognized the important role of clinical trials in improving the standards of HSCT medical care and they described their decision to participate as valuable. Participants overall reported positive attitudes towards HSCT clinical research. Here we describe four major themes identified and potential lessons learned that could be used to improve the experiences of future HSCT participants.

1. Information overload leading to limited recall

Many participants reported receiving too much information about studies for which they were participating, resulting in them not being able to recall many details. We found that participants were unable to articulate the type of trials that they (or their child) participated in and had difficulty in distinguishing the clinical research participation components from the HSCT procedure itself. Although ability to recall study details is expected to decay over time,16 our findings suggest that study participants did not fully comprehend the implications of what they consented to, which is in accordance with prior work.17,18 Additional challenges persist in HSCT due to complicated treatment plans or protocols that are not easy to explain in layman's language.19

Nonetheless, a majority of participants expressed a desire to be informed about the research studies in which they were participating and some actively searched for additional information. This highlights the difficult task of finding the right balance between providing too much and too little information to study participants, and about the potential need to tailor discussions and the informed consent process overall to the needs of each participant.20-22 A recent study demonstrated the feasibility of incorporating tailored information into the consent process about potential involvement for the National Cancer Institute/Department of Veteran Affairs co-sponsored Selenium and Vitamin E (Prostate) Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT).17 Both improved understanding and satisfaction were achieved with a modified consent document that included a brief video.

Study participants described the benefit of having a copy of their consent forms, not as a legal record, but rather as a resource with which to reference as new questions arose or as a reminder of the details of the study. The participants felt that the documents contained too much scientific and legal jargon, suggesting that improving readability of these documents is important beyond the initial consenting process.23 The National Institutes of Health and the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute have produced templates to facilitate the use of Easy-to-Read informed consent forms in cancer clinical trials.24 The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network is developing educational interventions to facilitate the use of these Easy-to-Read informed consent forms and is currently conducting a randomized, controlled trial of evaluating the effectiveness of the 2-column format.18

2. Altruism as a reason for participation

Despite the information overload and a lack of understanding about clinical research, adult patients and parents of pediatric HSCT patients were still drawn to participate in research. Often times, there are few options other than trial participation for HSCT patients.25 The finding that participants reported altruistic motives as a primary driver for their participation, including a desire to help the institution (i.e., institutional pride), is important because this provides insight into the decision making process of HSCT patients. Despite the distress and uncertainty of illness, HSCT participants viewed clinical research as important and as an opportunity to improve scientific knowledge. While both adult patients and parents of pediatric patients expressed a hope that the research would provide direct benefit, parents of children expressed greater desperation for any trial that could improve the chances of a positive outcome, consistent with prior work.26 Our findings suggest that it may be important to emphasize different, but equally important, aspects of clinical trials to improve participation rates (e.g., altruism or helping future adults and personal benefits for children). There are potential challenges to such an approach, however, and keeping the ethical implications in mind remains paramount.25

3. Trust in the BMT care team

Our study suggests that patients and their families are strongly influenced by the BMT care team's recommendations and the trust placed in them, which has been previously observed in other cancer patients considering Phase 3 randomized controlled trial entry.27 When asked who presented and reviewed information regarding the potential clinical research studies, including informed consent forms, patients and parents indicated either the BMT nurse coordinator, BMT physician, or both. While patients and parents of children often discussed treatment and research participation options with their spouses and/or children, many of the participants reported that they ultimately looked to their BMT care team (e.g., physicians and nurse coordinators) to provide expert guidance about their decision to participate in a trial and which trial(s) in which to join. Both adult patients and parents valued the time spent with their BMT care team explaining the research studies and ultimately looked to them for guidance when weighing risks and benefits. These results are supported by other recently reported studies that showed the importance of physician's recommendations as important determinants in participation.28,29 Furthermore, our observations should prompt future study on how best to inform patients about HSCT clinical trials. Undoubtedly, the role of the BMT care team remains critical as enhanced strategies are developed to improve the recruitment process.

4. Separating usual care from clinical research

It is common for clinical research protocols in HSCT to be conducted in conjunction with routine clinical HSCT care.25 A majority of participants from all three focus groups used the terms “BMT procedure” and “clinical research” interchangeably, and participants reported an inability to distinguish between research and routine care activities. For example, participants often signed multiple consent forms including ones for transfusions and bone marrow biopsies, as well as informed consent forms for standard HSCT medical care and clinical research trials. This not only overwhelmed patients, but often confused them since the clinical research trial forms required that aspects of routine HSCT care also be discussed. Thus, patients saw the same information duplicated on multiple forms making unclear which aspects were routine and which were experimental.

In our study, patients suggested a summary document listing distinctions between research and usual care, and ordering the potential complications by frequency. As investigators design protocols and forms, only risks associated with research-specific procedures should be identified. Risks related to usual care procedures should be separate from informed consent forms. However, regulatory agencies often mandate certain medical and legal language to be included by investigators. Enhancing accrual to HSCT clinical trials is therefore complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach that can support more than just providing packets of informed consent documents. We hope to better understand infrastructure barriers in our future survey questionnaire.

It is therefore not surprising that the ideals of truly informed consent are difficult to achieve in practice.30 Nevertheless, educational interventions and efforts to improve the process, targeting the HSCT population specifically, are underway.18 While the boundaries between research and clinical care are not entirely clear,31 extended discussions between investigators and research participants have been shown to improve understanding,32 and incorporating novel strategies, such as follow-up telephone calls, in-person conversations, or use of health information technology tools, are likely required.

Strengths and limitations

Our study examined the perspectives of both adult BMT patients and parents of pediatric BMT patients in the context of a high-risk procedure. We investigated their attitudes, motivations, and barriers toward participation in clinical research studies by conducting three unique focus group sessions. The sizes of the focus groups were evenly distributed and were small enough to allow for adequate deliberation of open-ended questions. The moderator's guide was developed from input provided by BMT staff and findings from previous research. These relevant topics, combined with the moderator's non-affiliation with the BMT program, likely facilitated the open communication and interaction among the group members.

We recognize a number of limitations also need to be addressed. First, the focus groups were conducted at a single institution (University of Michigan) and the number of participants was relatively small, particularly the parent group, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, there was a predominance of Caucasians and the socio-demographic factors were also relatively homogenous. The study population was skewed toward allogeneic HSCT patients (23 of the 25 participants). This was not surprising given that recruitment to the focus groups was conducted in the outpatient setting. In general, allogeneic patients at the University of Michigan are seen more commonly in outpatient BMT Clinics for routine post-HSCT follow-up, whereas autologous patients are referred back to their primary oncologists. As such, participants in the focus groups were representative of those usually cared for and managed by BMT physicians at the University of Michigan. Second, it is possible that our results were influenced by selection bias. Since post-HSCT patients were recruited as outpatients, only those who survived and whose physical health was stable were included in the study. It is possible that their relative healthy condition may have influenced their positive attitude toward clinical research.

Third, it is possible that our qualitative research process influenced the tendency for social desirability among participants favoring their responses in a manner they wanted to be perceived (e.g., discussing altruistic reasons for participation rather than personal benefits.) In line with this, our results may have been influenced by the effects of volunteer participants. For example, the overall positive attitudes and perceptions about clinical research may have been driven by patients who take a more proactive approach in their health care. Lastly, we have no knowledge about those who declined participation. For example, only one patient was documented in the electronic medical record as declining an interventional trial, but we did not explore additional information. We felt this was unnecessary since the objective of our study was to develop a questionnaire and we anticipate that we will identify these patients later. It is likely that patients who participated in the focus group discussion were more inclined to participate in research studies, in general.33 Our findings present a positive picture about clinical research studies perceived by our HSCT population. Although our study population was comprised primarily of post-HSCT patients recruited to focus groups, we also sampled pre-HSCT patients by conducting individual semi-structured qualitative interviews (five adults and two parents between November 2013 and March 2014; data not shown). Due to challenges with coordinating varying HSCT admission schedules, this was felt to be an ideal research methodology for this cohort of patients. In data not shown, the results from these pre-transplant interviews confirmed the findings of our focus groups. Pre-transplant respondents reported comparable decision making strategies, concerns, and hopes to the post-transplant focus group participants. Interestingly, pre-transplant respondents also indicated recall difficulties about the details of the research studies only hours after they were presented to them.

Based on the new knowledge generated in this study, we are developing a survey to be administered to all new, incoming HSCT patients. The design will include pre- and post-HSCT administration. This will allow us to capture those who declined participation and their reasons. It remains important to elucidate how patients and parents are engaged in the clinical research process. Moreover, surveying patients pre- and post-HSCT will also allow us to capture the more clinically ill and high risk inpatient cohort and follow their trajectory longitudinally. The new information will be integral in improving the informational needs of HSCT patients and possibly improving the process in which clinical research studies are presented, reviewed, and discussed with the patients and parents.

Conclusions

The study herein was a unique approach to measuring attitudes and opinions of HSCT patients and parents participating in clinical research studies. The themes that emerged were not necessarily unique to HSCT patients, but present possible targets to improve the clinical research process in a complex disease population. Patients valued their ability to participate as it provided a sense of purpose. Altruism or personal benefit was perceived as an important predictor of participation in clinical research studies. The focus group approach allowed us to acquire feedback directly from patients and parents. This research methodology showed the importance of maintaining contact with participants throughout the research and clinical care processes. Providing follow-up after participation in clinical research studies is highly desired by patients and parents, even simply indicating, “Thank you for participating.”

Based on the new knowledge generated in this study, we are developing a survey questionnaire to be administered to all new, incoming HSCT patients. The design will include pre- and post-HSCT administration. This will allow us to capture those who declined participation and their reasons. It remains important to elucidate how patients and parents are engaged in the clinical research process. Moreover, surveying patients pre- and post-HSCT will also allow us to capture the more clinically ill and high-risk inpatient cohort and follow their trajectory longitudinally. The new information will be integral in improving the informational needs of HSCT patients and possibly improving the process in which clinical research studies are presented, reviewed, and discussed with patients and parents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the adult patients, parents of pediatric patients, and the clinical personnel who participated in this study; the BMT Program Team for patient recruitment; the focus group moderator (Heidi Guyer); the Institute for Social Research study assistant (Michael Sadowsky), without which this study would not have been possible. This study was supported by a Scholar grant to S.W.C. from St. Baldrick's Foundation. S.W.C. is an Edith Briskin/A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute Emerging Scholar and receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI091623).

Support: This study was supported by a Scholar grant to S.W.C. from St. Baldrick's Foundation. S.W.C. is an Edith Briskin/A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute Emerging Scholar and is also supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI091623).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

References Cited

- 1.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:1617–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasquini MC, Wang Z, Horowitz MM, Gale RP. 2010 report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR): current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplants for blood and bone marrow disorders. Clin Transpl. 2010:87–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2091–101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara JL, Anasetti C, Stadtmauer E, et al. Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network State of the Science Symposium 2007. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:1268–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrara JL. Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network: Progress since the State of the Science Symposium 2007. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins FS. The Importance of Clinical Trials. [Last accessed on 4/18/2014];NIH Medline Plus. 2011 http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/magazine/issues/summer11/articles/summer11pg2-3.html.

- 8.Kelley WN. Careers in Clinical Research: Obstacles and Opportunities. Committee on Addressing Career Paths for Clinical Research, Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1994. Chairman. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, et al. CEntral challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:1278–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umutyan A, Chiechi C, Beckett LA, et al. Overcoming barriers to cancer clinical trial accrual: impact of a mass media campaign. Cancer. 2008;112:212–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.das Nair R, Orr KS, Vedhara K, Kendrick D. Exploring recruitment barriers and facilitators in early cancer detection trials: the use of pre-trial focus groups. Trials. 2014;15:98. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayter D, McDaid C, Eastwood A. A systematic review highlights threats to validity in studies of barriers to cancer trial participation. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2007;60:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee to Review the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of MedicineLeshner AI, Terry SF, Schultz AM, Liverman CT, editors. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. The CTSA Program at NIH: Opportunities for Advancing Clinical and Translational Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:1583–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Primary Care Research - a Multimethod Typology and Qualitative Road Map. Doing Qualitative Research. 1992;3:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hietanen P, Aro AR, Holli K, Absetz P. Information and communication in the context of a clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:2096–104. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raisch PC, Kennedy RL, Vanoni C, Thorland W, Owens N, Bennett CL. Improved understanding and satisfaction with a modified informed consent document: A randomized study. Patient Intelligence. 2012;4:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denzen EM, Santibanez ME, Moore H, et al. Easy-to-read informed consent forms for hematopoietic cell transplantation clinical trials. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept. of Education; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis PM. Attitudes towards and participation in randomised clinical trials in oncology: a review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:939–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1008342222205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McPherson CJ, Higginson IJ, Hearn J. Effective methods of giving information in cancer: a systematic literature review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of public health medicine. 2001;23:227–34. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolfall K, Shilling V, Hickey H, et al. Parents' agendas in paediatric clinical trial recruitment are different from researchers' and often remain unvoiced: a qualitative study. PloS one. 2013;8:e67352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:134–49. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comprehensive Working Group on Informed Consent in Cancer Clinical Trials for the National Cancer Institute Rec- ommendations for the Development of Informed Consent Documents for Cancer Clinical Trials. [Last accessed on May 2, 2014];NCI, NIH Publication 98-4355. 1998 Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/understanding/simplification-of-informed-consent-docs.

- 25.American Society of Clinical O. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: oversight of clinical research. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2377–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oberman M, Frader J. Dying children and medical research: access to clinical trials as benefit and burden. American journal of law & medicine. 2003;29:301–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins V, Farewell V, Farewell D, et al. Drivers and barriers to patient participation in RCTs. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1402–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, Houssami N. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:3554–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldige CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:830–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, Thornton J, Hewison J. Informed consent for clinical trials: in search of the “best” method. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1825–40. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayman RM, Taylor BJ, Peart NS, Galland BC, Sayers RM. Participation in research: informed consent, motivation and influence. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:51–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aaronson NK, Visser-Pol E, Leenhouts GH, et al. Telephone-based nursing intervention improves the effectiveness of the informed consent process in cancer clinical trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14:984–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buss MK, DuBenske LL, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Cleary JF. Patient/Caregiver influences for declining participation in supportive oncology trials. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.