Abstract

Aggression among combat veterans is of great concern. Although some studies have found an association between combat exposure and aggressive behavior following deployment, others conclude that aggression is more strongly associated with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and that alcohol misuse may influence this association. Many of these studies have assessed aggression as a single construct, whereas the current study explored both nonphysical aggression only and physical aggression in a sample of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans (N = 337; 91% male). We found that alcohol problems interacted with PTSD symptom severity to predict nonphysical aggression only. At low levels of PTSD symptoms, veterans with alcohol problems were more likely to perpetrate nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression, than veterans without an alcohol problem. There was no difference in the likelihood of nonphysical aggression only between those with and without alcohol problems at high levels of PTSD symptoms. The likelihood of nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression, was also greater among younger veterans. Greater combat exposure and PTSD symptom severity were associated with an increased likelihood of perpetrating physical aggression, as compared with no aggression. Ethnic minority status and younger age were also associated with physical aggression, as compared with no aggression. Findings suggest that a more detailed assessment of veterans’ aggressive behavior, as well as their alcohol problems and PTSD symptoms, by researchers and clinicians is needed in order to determine how best to intervene.

Keywords: Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans, aggression, PTSD, combat exposure, alcohol problems

Aggression perpetrated by veterans is a salient concern often highlighted in the media, the judicial system, and clinical settings (Elbogen, Fuller, et al., 2010; Sontag & Alvarez, 2008; Taft, Weatherill, et al., 2009) with rates as high as 41% in the past year (Taft, Monson, Hebenstreit, King, & King, 2009). In addition to creating tremendous risk of physical, psychological, and occupational harm for civilian victims (Coker et al., 2002; National Center for Injury Prevention & Control, 2003; Teten, Schumacher, et al., 2010), veterans who perpetrate aggressive behavior are themselves at increased risk for many negative outcomes including violent victimization, sexual risk-taking behavior, depression, and substance abuse (Coker et al., 2002; Raj et al., 2006; Teten, Schumacher, et al., 2010).

Within the general population, aggression is more likely among younger adults (Moffit, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996), individuals with a history of childhood physical abuse (Chermack, Stoltenberg, Fuller, & Blow, 2000; Taft, Schumm, Marshall, Panuzio, & Holtzworth–Munroe, 2008; Widom, 1989), members of ethnic minority groups (Benson, Fox, DeMaris, & Van Wyk, 2000; Caetano, Schafer, Clark, Cunradi, & Raspberry, 2000; Field & Caetano, 2004; Schafer, Caetano, & Clark, 1998; Straus & Smith, 1990), and those with lower income (Cunradi, Caetano, & Schafer, 2002). Early research specific to veterans suggested that combat exposure was predictive of subsequent aggression even after accounting for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; e.g., Barrett et al., 1996). More recently, studies have found that combat exposure may be a proxy risk factor and that PTSD better accounted for veterans’ perpetration of aggression (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Jakupcak et al., 2007; McFall, Fontana, Raskind, & Rosenheck, 1999; Sayers, Farrow, Ross, & Oslin, 2009; Taft, Vogt, Marshall, Panuzio, & Niles, 2007). Indeed, 70–75% of veterans diagnosed with PTSD report physical aggression in the previous year, as compared with 17–29% of veterans without PTSD (Beckham, Feldman, Kirby, Hertzberg, & Moore, 1997; Teten, Miller, et al., 2010). McFall and colleagues (1999) concluded that veterans with PTSD seeking inpatient treatment endorsed greater PTSD severity and were more violent than a community sample of veterans with comparable rates of combat exposure and veterans undergoing inpatient treatment with neither PTSD nor exposure to combat. These results indicate that PTSD symptom severity is a much stronger predictor of aggressive behavior as compared with the impact of combat exposure alone. This may be true because individuals with PTSD often report problems with anger/irritability and endorse difficulties tolerating and regulating negative emotions (Aldao, Nolen–Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010; Flack, Litz, Hseih, Kaloupek, & Keane, 2000; Jakupcak & Tull, 2005; Litz et al., 1997; Price, Monson, Callahan, & Rodriquez, 2006), which have been associated with subsequent aggression (Cohn, Jakupcak, Seibert, Hildebrandt, & Zeichner, 2010; Novaco & Chemtob, 2002; Tull, Jakupcak, Paulson, & Gratz, 2007). Moreover, other symptoms of PTSD such as emotional numbing and avoidance have been linked to the occurrence of aggression among veterans (Taft et al., 2007).

Alcohol problems are endorsed by as many as 36% of returning veterans previously deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan and may also help explain the relationship between PTSD and aggression among veterans (Burnett–Zeigler et al., 2011; Taft et al., 2007). Not only may alcohol be used in an effort to cope with symptoms of PTSD (Dixon, Leen–Feldner, Ham, Feldner, & Lewis, 2009; Simpson, 2003), but alcohol intoxication also impairs higher order cognitive processes important in regulating behavior and may result in behavioral disinhibition (Clements & Schumacher, 2010; Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Giancola, 2000). Veterans with PTSD who also have alcohol problems, therefore, may consume alcohol in an effort to cope with their distress and be more likely to engage in behaviors they would otherwise inhibit, such as aggression.

One methodological and theoretical limitation of previous research examining aggression among veterans is that it has often failed to examine possible differences between different types of aggression. The few studies that have examined aggression as a multidimensional construct have differentiated aggression toward self and others (Begić & Jokić-Begić, 2001), clinical and nonclinical levels of severity (Foran, Slep, & Heyman, 2011), and verbal or psychological and physical aggression (Byrne & Riggs, 1996; O’Donnell, Cook, Thompson, Riley, & Neria, 2006; Savarese, Suvak, King, & King, 2001; Taft, Weatherill, et al., 2009). It is important to better understand the correlates of different types of aggression as nonphysical aggressive acts of intimidation (e.g., destroying property) have different interpersonal, legal, and health-risk implications than engaging in physical acts of aggression (e.g., getting in to a fight; Cornelius, Shorey, & Kunde, 2009; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). A more nuanced understanding of factors likely to be associated with nonphysical and physical aggression may help guide clinicians’ assessment of acute risk and treatment planning. Other literatures that focus on aggression in different contexts, such as intimate partner violence, have consistently found that different factors predict different types of aggression, and it is now standard methodological practice to differentiate types of aggression perpetration in community samples (Basile & Hall, 2011; Delsol, Margolin, & John, 2003; Hamberger, Lohr, Bonge, & Tolin, 1996; Sullivan, McPartland, Armeli, Jaquier, & Tennen, 2012). We know of only one published study with veterans that differentiated aggressive behavior by type of aggression; Taft, Weatherill, et al. (2009) found that among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans, different subscales of their PTSD measure were significantly associated with psychological versus physical partner aggression. However, the authors did not examine the effects of alcohol problems on different types of aggression in this sample.

In order to address this critical gap in the literature, the current study sought to examine whether combat exposure, symptoms of PTSD, and alcohol problems predicted veterans’ nonphysical aggression only and physical aggression when compared with no aggression. After accounting for other known predictors of aggression, including demographic factors and childhood physical abuse, it was hypothesized that: (1) greater PTSD symptom severity would be associated with a greater likelihood of aggression above and beyond exposure to combat; (2) reporting a problem with alcohol would be associated with an increased likelihood of aggression; and (3) alcohol problems would moderate the association between PTSD symptom severity and aggression such that veterans with greater PTSD symptom severity who also had problems with alcohol would be more likely to report aggression. Given the limited prior research specific to PTSD and different types of aggression (i.e., nonphysical only and physical) among veterans, we explored whether there were different predictors of these two types of aggression included in the present study.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 337; 91% male) were Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans who were predominantly White (69%), had an average age of 31.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 8.5) years, and largely served in the U.S. Army (75%) while deployed. Nearly half were married (46%), and the majority graduated high school (98%), completed at least 4 years of college or technical school (54%), and were employed full-time (52%). Fourteen percent reported an annual combined household income less than $15,000, 27% reported between $15,000 and $24,999, 18% between $25,000 and $34,999, 16% between $35,000 and $49,999, and 25% $50,000 and above.

Procedures

Participants completed an assessment during their intake to a Veterans Affairs (VA) postdeployment health clinic between 2004 and 2007. Veterans who presented to this clinic were assessed and provided brief medical, social work, and/or mental health interventions to stabilize symptoms, and were referred to other clinics to address long-term treatment needs as necessary. As part of the initial assessment, participants completed paper-and-pencil questionnaires regarding their military deployment, combat exposure, and physical and mental health problems. The Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee of the VA Medical System at which the sample was drawn approved the use of de-identified patient data for research purposes.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to provide their gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, annual combined household income, education, and military history. Age and income were treated as continuous variables and gender and ethnicity were dichotomous (gender: 0 = female; 1 = male; ethnicity: 0 = ethnic minority and 1 = Caucasian).

Childhood physical abuse

Participants were presented a single item and asked to indicate whether or not they were physically abused as a child (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Combat exposure

Combat exposure was assessed using 10 items from the Combat Exposure Scale (Laufer, Gallops, & Frey–Wouters, 1984) and 17 items from the Desert Storm trauma Questionnaire (Southwick et al., 1993). Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they experienced a wide range of combat-related events, including taking care of someone who was wounded or whose life was not saved, or personal injury or wounds sustained during combat. The positively endorsed items were summed together to create a composite combat exposure score with good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .89).

Alcohol problems

Alcohol problems were assessed with a subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). Participants who reported any alcohol consumption were asked to indicate whether they experienced any of the five symptoms of alcohol abuse (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM–IV]; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) more than once in the past 6 months. The items assessed both problematic behavior (e.g., drove a car after having several drinks or after drinking too much) and negative outcomes associated with alcohol consumption (e.g., missing work, school, or other activities because you were drinking or hung over). Consistent with the DSM–IV criteria for alcohol abuse, a dichotomous variable was created with an endorsement of 1 or more items indicative of alcohol problems.

PTSD symptom severity

Symptoms of PTSD were assessed using the 17-item PTSD Checklist Military Version (PCL-M; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). Participants reported the extent to which they were bothered by the PTSD symptoms defined by the DSM–IV (APA, 1994) in the past month using 5-point scales (1 = Not at all; 5 = Extremely). The PCL-M demonstrated excellent internal consistency among this sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .96). Items were summed to reflect total PTSD symptom severity.

Aggression

Aggressive behavior over the past 4 months was assessed using four items adapted from the National Vietnam Adjustment Study (see McFall et al., 1999). Nonphysical aggression was operationalized as positive responses to destroying property or threatening someone with physical violence without a weapon. Participants who reported getting into a physical fight were considered to have engaged in physical aggression, though they may have also reported nonphysical aggression. A fourth item about threatening someone with a weapon was not included in either category due to the ambiguity associated with the term “weapon” (e.g., a stick vs. a firearm) and the unknown motivation for the threat (e.g., damage someone’s car vs. injure physically), therefore the nature of this act as either nonphysical or physical aggression is unclear.

Results

Eighteen percent of the sample (n = 60) reported perpetrating nonphysical aggression only and 14% (n = 48) reported physical aggression in the 4 months prior to presenting to the VA. For individuals who were categorized as having engaged in nonphysical aggression only, 29 indicated they destroyed property (mean [M] = 1.86, standard deviation [SD] = 1.72, Mode = 1) and 41 threatened someone with physical violence (M = 2.05, SD = 3.74, Mode = 0). Of those reporting physical aggression, the average number of physical fights was 1.98 (SD = 1.79) and 83% (n = 40) endorsed nonphysical aggression in addition to physical aggression. Twenty-five percent of the sample (n = 84) endorsed at least one problem related to alcohol use suggestive of alcohol abuse and 13% (n = 44) reported a history of childhood physical abuse. As shown in Table 1, a greater percentage of participants who reported nonphysical or physical aggression also endorsed at least one alcohol problem compared to those with no aggression. Additionally, aggressive participants were younger and endorsed more combat exposure and greater PTSD symptom severity than those with no aggression.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information by the Type of Aggressive Behavior

| No aggression (n = 221) |

Nonphysical aggression only (n = 60) |

Physical aggression (n = 48) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 156 (74.3) | 43 (71.7) | 29 (60.4) |

| Childhood physical abuse | 25 (11.3) | 12 (20.0) | 6 (12.5) |

| Alcohol problems | 40 (20.3)a | 23 (38.3)b | 19 (39.6)b |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 32.36 (8.96)a | 29.69 (6.81)b | 27.76 (7.75)b |

| Combat exposure | 8.96 (5.53)a | 11.98 (4.57)b | 12.85 (5.09)b |

| PTSD symptoms | 38.01 (17.71)a | 54.67 (16.04)b | 53.74 (18.68)b |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SD = standard deviation.

Means with different subscripts are significantly different (p < .05).

Multinomial logistic regressions were conducted for the primary analysis examining the correlates of both nonphysical aggression only and physical aggression with no aggression as the reference category. First, we ran a model that included only the main effects of combat exposure, alcohol problems, PTSD symptom severity, demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, ethnicity, age, and annual household income), and childhood physical abuse status as independent variables. Then we ran a model including the same independent variables as well as an interaction term between alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 was evaluated for both models to determine whether or not the addition of the interaction term improved model fit above and beyond the main effects only model. If the value increased, the interaction term was thought to provide important information to the overall model and therefore was retained. Although there was a strong correlation between combat exposure and PTSD symptom severity (r = .519, p = .001), multicollinearity was examined and determined to not be a problem in the current model.

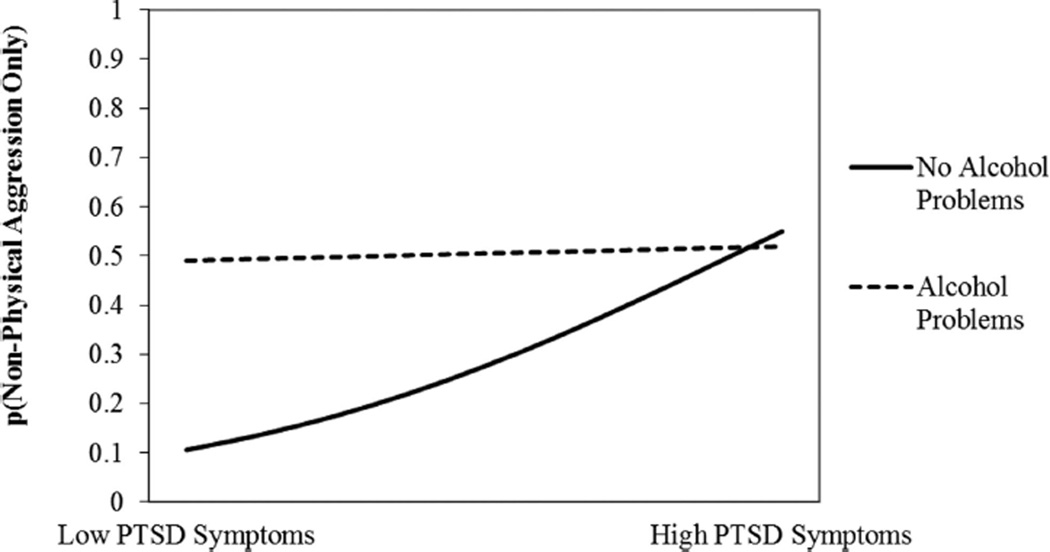

For nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression (Table 2, Model 1a), there were significant main effects of age (b = −0.05, odds ratio [OR] = 0.95) and PTSD symptom severity (b = 0.04, OR = 1.04) such that younger individuals and those with a greater level of PTSD symptomatology were more likely to perpetrate nonphysical compared to no aggression. There were no significant main effects of gender, ethnicity, income, childhood physical abuse, combat exposure, and alcohol problems on non-physical aggression only relative to no aggression. As shown in Table 2, Model 2a, there was a significant interaction between alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity (b = −0.06, OR = 0.94). The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 value increased from Model 1a to Model 2a, which suggests that Model 2a was a better fit for the data and accounted for 33% of the variance. The interaction between alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity was probed by conducting logistic regressions comparing those with and without alcohol problems predicting nonphysical aggression only at both high and low levels of PTSD symptomatology. As shown in Figure 1, veterans with alcohol problems were more likely to perpetrate nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression, at low levels of PTSD than were veterans without alcohol problems (b = 2.3, p < .001). There was no difference in the likelihood of nonphysical aggression only between those with and without alcohol problems at high levels of PTSD symptoms (b = 0.14, p = .72).

Table 2.

Predictors of Both Nonphysical Aggression Only and Physical Aggression as Compared With No Aggression

| Predictors | Nonphysical aggression only | Physical aggression | Nagelkerke pseudo R2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | p-value | OR [95% CI] | b | p-value | OR [95% CI] | ||

| Model 1a | Model 1b | .30 | |||||

| Male gender | 0.30 | .63 | 1.35 [0.40, 4.61] | 0.76 | .36 | 2.13 [0.42, 10.94] | |

| Caucasian | −0.06 | .89 | 0.95 [0.43, 2.10] | −0.90 | .04 | 0.41 [0.17, 0.96] | |

| Age | −0.05 | .04 | 0.95 [0.91, 1.00] | −0.08 | .02 | 0.92 [0.87, 0.99] | |

| Income | 0.07 | .61 | 1.07 [0.82, 1.40] | −0.31 | .06 | 0.74 [0.53, 1.02] | |

| CPA | 0.16 | .73 | 1.17 [0.47, 2.92] | −0.60 | .37 | 0.55 [0.15, 2.04] | |

| Combat exposure | 0.02 | .57 | 1.02 [0.95, 1.10] | 0.09 | .04 | 1.09 [1.00, 1.19] | |

| Alcohol problems | 0.54 | .15 | 1.72 [0.82, 4.61] | 0.59 | .17 | 1.80 [0.78, 4.16] | |

| PTSD symptoms | 0.04 | .00 | 1.04 [1.02, 1.07] | 0.03 | .01 | 1.04 [1.01, 1.06] | |

| Model 2a | Model 2b | .33 | |||||

| Alcohol × PTSD | −0.06 | .01 | 0.94 [0.91, 0.98] | 0.01 | .63 | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; CPA = childhood physical abuse; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Coefficients presented for Model 1 are from the main effects only model. Model 2 includes all variables from Model 1 in addition to the interaction term. The only significant change in main effects from Model 1 to Model 2 was a significant main effect of alcohol problems for nonphysical aggression only compared to no aggression (b = 1.01, p = .01, OR = 2.73 [95% CI, 1.27, 5.88]), which was superseded by the significant interaction between alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of nonphysical aggression only as compared with no aggression as a function of alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity.

A different pattern emerged for physical aggression, as compared with no aggression. Ethnic minority status (b = −0.90, OR = 0.41), younger age (b = −0.08, OR = 0.92), higher combat exposure (b = 0.09, OR = 1.09), and a greater level of PTSD symptom severity (b = 0.03, OR = 1.04) were associated with an increased likelihood of perpetrating physical compared to no aggression.1 Gender, income, childhood physical abuse, and alcohol problems did not significantly predict physical aggression in Model 1b. The addition of the interaction between alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity in Model 2b was also not significant suggesting that alcohol problems did not moderate the association between PTSD symptom severity and physical aggression, as compared with no aggression.

Discussion

The present study investigated the factors associated with non-physical aggression only and physical aggression each relative to no aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. In general, rates of aggression and alcohol problems observed in the present study were lower than previous reports; however, this is likely due to the shorter assessment timeframe of 4 months used in this investigation. We expected that PTSD symptom severity and alcohol problems would be associated with aggressive behavior above and beyond the influence of combat exposure. We also hypothesized that there would be a significant interaction between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol problems such that those with alcohol problems and more severe PTSD would be more likely to report both types of aggression. Overall, we found partial support for our study hypotheses.

Focusing first on the findings regarding nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression, we found that PTSD severity interacted with alcohol problems. At low levels of PTSD symptoms, nonphysical aggression only was more likely among veterans with alcohol problems than those without alcohol problems. At high levels of PTSD symptoms, however, there was no difference in the likelihood of nonphysical aggression only among veterans with and without alcohol problems. Younger veterans were more likely to report engaging in nonphysical aggression as opposed to no aggression.

These findings highlight the apparent role of alcohol problems in the perpetration of nonphysical aggression, especially at lower levels of PTSD symptoms. The application of Alcohol Myopia Theory (Steele & Josephs, 1990; Taylor & Leonard, 1983) to future research may facilitate a better understanding of the relationship between alcohol problems and nonphysical aggression only. Alcohol Myopia Theory suggests that alcohol intoxication limits the amount of information an individual can process at one time. Thus, attention is focused on the most salient cues in their environment, which could include signals of threat or aggression that increase the likelihood of aggressive acts such as verbal threats or property destruction. Although we did not directly assess alcohol consumption at the time of aggression perpetration, it is likely that the presence of an alcohol problem is indicative of increased consumption, thereby placing the veteran at risk for the disinhibiting effects of alcohol associated with engaging in aggressive behaviors. Additionally, veterans without an alcohol problem who had greater PTSD severity were as likely as those with an alcohol problem to report engaging in nonphysical aggression only, as compared with no aggression. Their aggression may have resulted from difficulties tolerating and regulating the strong negative emotions often associated with PTSD, especially the emotional numbing and hyperarousal symptom clusters (Aldao, Nolen–Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010; Flack et al., 2000; Litz et al., 1997). A model suggesting that aggression is likely only when the impelling forces are stronger than the inhibiting forces for such behavior was developed by Finkel (2007) and has been applied to veterans’ aggressive behavior (Taft et al., 2012). In addition to the effects of alcohol myopia, combat experiences and resulting symptoms of PTSD may lead to a heightened sense of threat perception (Chemtob, Novaco, Hamada, Gross, & Smith, 1997) and may help explain how both PTSD and problematic alcohol use could be associated with aggressive behavior in this population.

Turning now to findings regarding physical aggression, we found that being a member of an ethnic minority group, being younger, more severe combat exposure, and greater PTSD symptom severity were associated with engaging in physical aggression, as compared with no aggression. Although many individuals who reported physical aggression also engaged in nonphysical aggression, our results indicate that alcohol problems were not associated with likelihood of engaging in physical aggression, as compared with no aggression. The lack of association between alcohol problems and physical aggression was surprising given that many other studies have found that alcohol increases the likelihood of getting in to physical fights (Graham, Osgood, Wells, & Stockwell, 2006; Taft, Kaloupek, et al., 2007). Additionally, if alcohol myopia is important for the occurrence of nonphysical aggression as discussed above, it likely would also play a role in physical aggression. Although it may be possible that PTSD symptom severity was more predictive of physical aggression than were alcohol problems in our sample of veterans, the lack of significant association between alcohol problems and physical aggression may also be due to limitations in our assessment of these constructs. Specifically, physical aggression was limited to a single item that provided only a general assessment of a range of possible behaviors. We also did not include an assessment of the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, which may be more predictive of physical aggression than problems with alcohol per se. Additionally, both of these measures covered only a relatively brief time frame. The current study also did not include an assessment of illicit drug use, which has been demonstrated to be a predictor of aggressive behavior (Goldstein, 1985); thus, it is possible that drug use other than alcohol would be associated with physical aggression. Future studies should include a more thorough examination of physical aggression as well as alcohol and other drug use (including quantity and frequency) over a longer period of time to better explain their association among veterans.

Demographic characteristics such as ethnic minority status and younger age were associated with physical aggression in the current study and have been found to be significant predictors of aggression more generally (e.g., Benson et al., 2003; Caetano et al., 2000; Cunradi et al., 2002; Moffit et al., 1996). Veterans who perpetrated physical aggression may also have been more likely to be aggressive prior to their military service, and combat exposure served to further desensitize them to aggression. Although we did not assess aggression that may have occurred prior to the military, Fontana and Rosenheck (2005) concluded that postmilitary violence was primarily the result of premilitary experiences, including behaviors consistent with conduct disorder (e.g., substance use, destroying property, starting fist fights). This is an important issue for future research as it is not known how combat exposure and mental health problems occurring as a result of combat exposure could influence the trajectory of aggression that began prior to service in the military.

Several limitations of the present research should be noted. First, the participants included in this investigation were seeking medical and/or mental health treatment from a single VA medical center, so these findings may not generalize to veterans in other geographical regions and those who do not seek VA treatment following their deployment. Our assessment was designed to briefly evaluate recent clinical functioning that might be immediately concerning and therefore did not include a thorough examination of many of the constructs of interest. Of particular importance to the current investigation is that the assessment of aggression was limited to three items and therefore does not represent a complete range of aggressive behavior. Our assessment was similar to those used in other research on aggression among veterans (e.g., McFall et al., 1999), however, we excluded one item (i.e., threatening with a weapon) because it was not clear whether this might be considered physical aggression contingent upon the type of “weapon” that was threatened to be used (e.g., a stick vs. a firearm) and the motivation for its use (e.g., damage someone’s car vs. injure physically). Another item regarding difficulty controlling aggressive behavior in the past 30 days was also excluded because it did not fit our categorization of nonphysical and physical aggression. Therefore, interpretations should be made in light of the revised brief assessment used herein. Although we focused on nonphysical and physical aggression, future research should more thoroughly assess a broader range of aggressive behaviors and explore the effects of PTSD and alcohol use on other possible dimensions including verbal (or psychological) and physical aggression as well as the severity of aggressive acts. The 4-month time frame provided important information regarding a veteran’s acute risk, although it is likely why the rates of occurrence of each behavior were low. Longer assessment time frames should be used in future research. Similarly, for the items involving interpersonal aggression, the intended victim was not known, nor was the level of preparation (i.e., impulsive or premeditated) or the motivation for the aggressive act. Determining these aspects of aggressive behavior is important, as the interventions for such behavior may be quite different if, for example, it is a premeditated act toward a romantic partner intended to exert power and control or an impulsive fight with a stranger at a bar in self-defense.

Additional limitations include the fact that our assessment of childhood physical abuse was limited to a single item that was behaviorally oriented and thus for participants to positively endorse this item they had to label their childhood experiences as abuse. We believe this may have reduced the number of participants who reported childhood physical abuse, as compared with those who actually experienced abuse. For those who did endorse abuse, however, this served to control for early exposure to trauma prior to their participation in the military. Additionally, we did not collect information about the quantity and frequency of alcohol use or drug use or proximity to aggressive behaviors, which may have informed the pattern of results we observed. All data were collected via self-report as opposed to structured diagnostic interviews or collateral reports. It is possible that these data are biased based on retrospective recall and positive impression management on the part of participants, the latter being an issue because the information was collected in the context of a clinical intake and was therefore not anonymously reported. Lastly, symptoms of PTSD, problematic alcohol use, and aggression were assessed and aggregated across approximately the same time frame and the study design was cross-sectional. Therefore, we cannot determine with certainty that any of the variables under investigation led to aggressive behavior. Future studies that employ a more sequenced analysis of the occurrence of symptoms of PTSD, problematic alcohol use, and aggressive behavior such as daily monitoring studies are needed to disentangle the temporal associations.

Limitations notwithstanding, the results of the present investigation expand upon our earlier understanding of the correlates of aggression in veterans (e.g., Barrett et al., 1996; McFall et al., 1999) and suggest that a more nuanced assessment of their aggressive behaviors is necessary in addition to a thorough assessment of alcohol problems and PTSD symptom severity. Among veterans who perpetrate aggression, it is important that researchers and clinicians assess the type of aggressive behavior and the context in which it occurs, in order to determine the best course of treatment. For example, clinicians working with veterans who have perpetrated nonphysical aggression only might consider treatments targeting situational or proximal factors associated with aggression, including interventions that target excessive alcohol use as they may help reduce the impact of alcohol-related myopia and/or disinhibition that can lead to nonphysical aggression. For both nonphysical and physical aggression, clinicians might employ techniques to enhance emotion regulation skills and reduce distress associated with symptoms of PTSD especially in the absence of an alcohol problem. The current results could help to inform an evidence-based approach for assessing violence risk among all veterans (e.g., Elbogen, Wagner, et al., 2010) and underscore that a one-size-fits-all approach to assessing and treating aggression does not appropriately capture the complexity of such behavior, especially in light of the myriad problems veterans often face. Increased sensitivity to the differential influences of alcohol problems and PTSD symptoms on types of aggression is likely to improve our understanding of these behaviors as well as the intervention efforts necessary to decrease aggression among veterans.

Footnotes

In an effort to further explore the relationships between ethnic minority status and combat exposure on physical aggression, we conducted post-hoc analyses examining whether ethnic minority status moderated the effect of combat exposure on physical as compared with no aggression. The interaction between ethnicity and combat exposure was added to the multinomial logistic regression and was not significant (p = .32).

Contributor Information

Cynthia A. Stappenbeck, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division, Seattle, Washington

Julianne C. Hellmuth, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division, Seattle, Washington

Tracy Simpson, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division, Seattle, Washington, and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington.

Matthew Jakupcak, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division, Seattle, Washington, and University of Washington.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen–Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DH, Resnick HS, Foy DW, Dansky BS, Flander WD, Stroup NE. Combat exposure and adult psychosocial adjustment among U.S. Army Veterans serving in Vietnam 1965–1971. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:575–581. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Hall JE. Intimate partner violence perpetration by court-ordered men: Distinctions and intersections among physical violence, sexual violence, psychological abuse, and stalking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:230–253. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Feldman ME, Kirby AC, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD. Interpersonal violence and its correlates in Vietnam veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;53:859–869. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199712)53:8<859::aid-jclp11>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begić D, Jokić-Begić N. Aggressive behavior in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine. 2001;166:671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson ML, Fox GL, DeMaris A, Van Wyk J. Neighborhood disadvantage, individual economic distress, and violence against women in intimate relationships. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2003;19:207–235. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett–Zeigler I, Ilgen M, Valenstein M, Zivin K, Gorman L, Blow A, Chermack S. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among returning Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne CA, Riggs DS. The cycle of trauma: Relationship aggression in male Vietnam veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:213–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Clark C, Cunradi C, Raspberry K. Intimate partner violence, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Novaco RW, Hamada RS, Gross DM, Smith G. Anger regulation deficits in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:17–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1024852228908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Stoltenberg SF, Fuller BE, Blow FC. Gender differences in the development of substance related problems: The impact of family history of alcoholism, family history of violence, and childhood conduct problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:845–852. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Schumacher JA. Perceptual biases in social cognition as potential moderators of the relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15:357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Jakupcak M, Seibert LA, Hildebrandt TB, Zeichner A. The role of emotion dysregulation in the association between men’s restrictive emotionality and use of physical aggression. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2010;11:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius TL, Shorey RC, Kunde A. Legal consequences of dating violence: A critical review and directions for improved behavioral contingencies. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Delsol C, Margolin G, John RS. A typology of martially violent men and correlates of violence in a community sample. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:635–651. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen–Feldner EW, Ham LS, Feldner MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Fuller S, Johnson SC, Brooks S, Kineer P, Calhoun PS. Improving risk assessment of violence among military veterans: An evidence based approach for clinical decision making. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Fuller SR, Calhoun PS, Kinneer PM, Beckham JC. Correlates of anger and hostility in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1051–1058. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R. Ethnic differences in intimate partner violence in the U.S. general population: The role of alcohol use and socioeconomic status. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5:303–317. doi: 10.1177/1524838004269488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11:193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Litz BT, Hseih FY, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM. Predictors of emotional numbing, revisited: A replication and extension. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:611–618. doi: 10.1023/A:1007806132319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Rosenheck R. The role of war-zone trauma and PTSD in the etiology of antisocial behavior. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:203–209. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154835.92962.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Slep AM, Heyman RE. Prevalences of intimate partner violence in a representative U.S. Air Force sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:391–397. doi: 10.1037/a0022962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning: A conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:576–597. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PJ. The drugs/violence nexus: A tripartite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985;15:493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Osgood DW, Wells S, Stockwell T. To what extent is intoxication associated with aggression in bars? A multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:382–390. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Lohr JM, Bonge D, Tolin DF. A large sample empirical typology of male spouse abusers and its relationship to dimensions of abuse. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken MS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Conybeare D, Phelps L, Hunt S, Holmes HA, Felker B, McFall ME. Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:945–954. doi: 10.1002/jts.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT. Effects of trauma exposure on anger, aggression, and violence in a non-clinical sample of men. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:589–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer RS, Gallops MS, Frey–Wouters E. War stress and trauma: The Vietnam experience. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1984;25:65–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Schlenger WE, Weathers FW, Caddell JM, Fairbank JA, LaVange LM. Predictors of emotional numbing in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:607–618. doi: 10.1023/a:1024845819585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall M, Fontana A, Raskind M, Rosenheck R. Analysis of violence behavior in Vietnam combat veteran psychiatric inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:501–517. doi: 10.1023/A:1024771121189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva PA, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescence-onset antisocial conduct in males: National history from age 3 to 18. Developmental and Psychopathology. 1996;8:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Novaco RW, Chemtob CM. Anger and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:123–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1014855924072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell C, Cook JM, Thompson R, Riley K, Neria Y. Verbal and physical aggression in World War II former prisoners of war: Role of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:859–866. doi: 10.1002/jts.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Monson CM, Callahan K, Rodriquez BF. The role of emotional functioning in military-related PTSD and its treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1873–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarese VW, Suvak MK, King LA, King DW. Relationships among alcohol use, hyperarousal, and marital abuse and violence in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:713–732. doi: 10.1023/A:1013038021175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Farrow VA, Ross J, Oslin DW. Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:163–170. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1702–1704. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL. Childhood sexual abuse, PTSD, and the functional roles of alcohol use among women drinkers. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38:249–270. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag D, Alvarez L. Across America, deadly echoes of foreign battles. The New York Times. 2008 Jan 13; Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/us/13vets.html. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Morgan A, Nagy LM, Bremmer D, Nicolaou AL, Johnson DR, Charney DS. Trauma related symptoms in veterans of Operation Desert Storm: A preliminary report. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1524–1528. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Patient Health Questionnaire study group. Validity and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Smith C. Violence in Hispanic families in the United States: Incidence rates and structural interpretations. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8, 145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, McPartland TS, Armeli S, Jaquier V, Tennen H. Is it the exception or the rule? Daily co-occurrence of physical, sexual, and psychological partner violence in a 90-day study of substance-using community women. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0027106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Kachadourian LK, Suvak MK, Pinto LA, Miller MM, Knight JA, Marx BP. Examining impelling and disinhibiting factors for intimate partner violence in veterans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:285–289. doi: 10.1037/a0027424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Kaloupek DG, Schumm JA, Marshall AD, Panuzio J, King DW, Keane TM. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, physiological reactivity, alcohol problems, and aggression among military veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:498–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Monson CM, Hebenstreit CL, King DW, King LA. Examining the correlates of aggression among male and female Vietnam veterans. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:639–652. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm JA, Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Holtzworth– Munroe A. Family-of-origin maltreatment, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, social information processing deficits, and relationship abuse perpetration. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:637–646. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Vogt DS, Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Niles BI. Aggression among combat veterans: Relationships with combat exposure and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, dysphoria, and anxiety. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:135–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Weatherill RP, Woodward HE, Pinto LA, Watkins LE, Miller MW, Dekel R. Intimate partner and general aggression perpetration among combat veterans presenting to a posttraumatic stress disorder clinic. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:461–468. doi: 10.1037/a0016657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein JE, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and empirical reviews, issues in research. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1983. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Teten AL, Miller LA, Standford MS, Petersen NJ, Bailey SD, Collins RL, Kent TA. Characterizing aggression and its association to anger and hostility among male veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine. 2010;175:405–410. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teten AL, Schumacher JA, Taft CT, Stanley MA, Kent TA, Bailey SD, White DL. Intimate partner aggression perpetrated and sustained by male Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1612–1630. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women study. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Jakupcak M, Paulson A, Gratz KL. The role of emotional inexpressivity and experiential avoidance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and aggressive behavior among men exposed to interpersonal violence. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping: An International Journal. 2007;20:337–351. doi: 10.1080/10615800701379249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility; Paper presented at the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, Texas. 1993. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]