Abstract

Aims

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common comorbidity in bradycardia patients. Advanced pacemakers feature atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing (DDDRP) and managed ventricular pacing (MVP), which minimizes unnecessary right ventricular pacing. We evaluated whether DDDRP and MVP might reduce mortality, morbidity, or progression to permanent AF when compared with standard dual-chamber pacing (Control DDDR).

Methods and results

In a randomized, parallel, single-blind, multi-centre trial we enrolled 1300 patients with bradycardia and previous atrial tachyarrhythmias, in whom a DDDRP pacemaker had recently been implanted. History of permanent AF and third-degree atrioventricular block were exclusion criteria. After a 1-month run-in period, 1166 eligible patients, aged 74 ± 9 years, 50% females, were randomized to Control DDDR, DDDRP + MVP, or MVP. Analysis was intention-to-treat.

The primary outcome, i.e. the 2-year incidence of a combined endpoint composed of death, cardiovascular hospitalizations, or permanent AF, occurred in 102/385 (26.5%) Control DDDR patients, in 76/383 (19.8%) DDDRP + MVP patients [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.74, 95% confidence interval 0.55–0.99, P = 0.04 vs. Control DDDR] and in 85/398 (21.4%) MVP patients (HR = 0.89, 95% confidence interval 0.77–1.03, P = 0.125 vs. Control DDDR). When compared with Control DDDR, DDDRP + MVP reduced the risk for AF longer than 1 day (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.52–0.85, P < 0.001), AF longer than 7 days (HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.36–0.73, P < 0.001), and permanent AF (HR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.21–0.75, P = 0.004).

Conclusion

In patients with bradycardia and atrial tachyarrhythmias, DDDRP + MVP is superior to standard dual-chamber pacing. The primary endpoint was significantly lowered through the reduction of the progression of atrial tachyarrhythmias to permanent AF.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

Keywords: Pacemaker, Bradycardia, Atrial fibrillation, Atrial antitachycardia pacing, Managed ventricular pacing

See page 2349 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu190)

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), which is recognized as a cause of mortality, morbidity, and quality of life impairment, is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice, and its incidence is increasing rapidly worldwide.1,2 In patients suffering from bradycardia, AF is a common comorbidity, being present in up to one-third of patients.3,4

The best pacing mode in patients suffering from bradycardia and AF is still debated. While physiologic pacing has proved superior to single-chamber ventricular pacing in the prevention of AF, the choice between AAI and DDD pacing in sinus node disease (SND) is still controversial.5–7 A recent trial concluded in favour of DDD pacing, as AAI was associated with a higher AF incidence, at least in patients with a long PR interval.8 Moreover, patients with SND who are treated with AAI pacing may subsequently develop atrioventricular (AV) block requiring upgrade to DDD. A new pacing modality, managed ventricular pacing (MVP), has been designed to give priority to intrinsic ventricular activation, thereby minimizing the adverse effects of right ventricular pacing, while protecting patients from intermittent or permanent AV block.9–11 Indeed, algorithms designed to minimize ventricular stimulation have been associated with persistent AF reduction.11

Advanced pacemaker technology includes extensive diagnostic capabilities and a comprehensive armamentarium of atrial pacing algorithms, for preventing atrial tachyarrhythmias, and of atrial antitachycardia pacing (aATP) therapies for terminating such arrhythmias.3,12,13 Despite many studies, the real clinical impact of these algorithms is still unclear.7

We hypothesized that the mixed results of previous studies on the therapeutic effect of atrial preventive pacing and aATP therapies might be due to the detrimental effects induced by unnecessary right ventricular stimulation and by a less than optimal choice of study design or study endpoints.14 We therefore planned the ‘MINimizE Right Ventricular pacing to prevent Atrial fibrillation and heart failure’ (MINERVA) multicentre randomized study in order to evaluate whether a complete pacing modality, which exploits atrial preventive pacing, aATP, and MVP, might reduce mortality, morbidity, or progression to permanent AF compared with standard dual-chamber pacing.

Methods

Study design and patient population

The details of the design of MINERVA have been already provided.14 In brief, MINERVA was a multicentre, randomized single-blind controlled trial involving 63 cardiology centres in 15 countries, as listed in the Supplementary material online, Appendix.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of all participating centres and was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria were standard indications for permanent dual-chamber pacing and a history of paroxysmal or persistent atrial tachyarrhythmias (at least one episode of AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia in the last 12 months documented by ECG or Holter). The main exclusion criteria were third-degree AV block or history of AV node ablation, history of permanent AF, and candidacy for defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy device implantation, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, anticipated major cardiac surgery, AF ablation, or other cardiac surgery. Other exclusion criteria, common to randomized trials are reported in detail in Supplementary material online, Appendix.

Enrolled patients underwent standard implantation of a dual-chamber Medtronic EnRhythm™ pacemaker with bipolar leads in the right atrium and ventricle. As reported in detail in Supplementary material online, Appendix, EnRhythm™ is a DDDR pacemaker with specific features for (i) giving priority to intrinsic AV conduction by means of MVP (atrial pacing with ventricular backup pacing if AV-conduction fails); (ii) detecting atrial tachyarrhythmias with high sensitivity and specificity; (iii) preventing the onset of atrial tachyarrhythmias through three atrial preventive pacing algorithms; (iv) terminating atrial tachyarrhythmias by means of aATP being delivered at the onset of arrhythmia, as well during its dynamic changes towards slower or more organized rhythms (Reactive ATP). Atrial ATP could be programmed as a Ramp, consisting of a programmable number of AOO pulses delivered at decreasing intervals, or as a Burst+, consisting of a programmable number of AOO pulses followed by two premature stimuli delivered at shorter intervals.

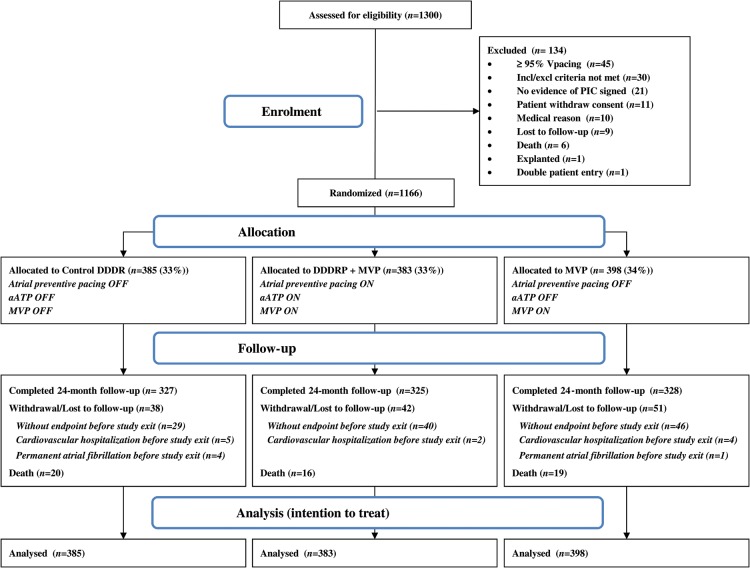

Device implantation was followed by a 1-month run-in period (Figure 1), during which all pacemakers were programmed with MVP ON, in order to minimize ventricular pacing, and with aATP and atrial preventive pacing OFF. The run-in period was used to allow patient stabilization after implant and to verify that patients did not depend on ventricular stimulation; patients with ventricular pacing ≥95% on device check in the run-in period were excluded from the study. At the end of the run-in period, randomization was performed.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. PIC, patient informed consent; MVP, managed ventricular pacing; aATP, atrial antitachycardia pacing; DDDRP, atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing.

Randomization, allocation concealment, and masking

The method used to generate the random allocation sequence was random sample inside each randomization block, stratified to balance out the presence/absence of AV-block and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40 or ≥40%. Each patient assignment was concealed in the study website and not revealed until all baseline data had been collected and the patient was deemed eligible for randomization. The requirements for patient randomization were compliance with eligibility criteria, sinus rhythm at the time of the randomization visit, and non-dependency on ventricular stimulation. Investigators accessed patient randomization through the study website and assigned the randomization to participants who remained blind as for treatment arm.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 manner to (i) standard dual-chamber pacing (Control DDDR Group), (ii) atrial preventive pacing, aATP, and MVP (DDDRP + MVP Group), and (c) DDDR with MVP (MVP Group).

Device programming

Atrial preventive pacing, aATP and MVP were OFF in the DDDR Control group while they were activated in the DDDRP + MVP group; in the MVP group, only MVP was enabled. Specific details about device programming are described in Supplementary material online, Appendix. Programming of the sensed, paced, and rate adaptive AV delays was performed by investigators with the aim of limiting ventricular stimulation as much as possible. Mode switching and AF detection were required to be enabled in all the three study arms. Investigators were required to avoid cross overs and to provide the therapy specified for each treatment arm.

Patient follow-up

Patients underwent follow-up examination in their respective therapy groups at 3 and 6 months after implantation and thereafter every 6 months until 24th month after implantation. Last enrolled patient had 24 months of follow-up, while previous patients were followed longer. At the end of the study, a vital status check was performed by calling patients or their relatives or by contacting the local Vital Records Offices.

No medications or treatments beyond specified pacemaker programming were specifically required or prohibited in this trial, unless they were investigational or in conflict with the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Study objectives

The main study objective was to compare the impact of an enhanced pacing modality (DDDRP + MVP) vs. Control DDDR pacing on the 2-year incidence of a composite clinical endpoint including all-cause death, cardiovascular hospitalization, or permanent AF. The comparisons between Control DDDR and MVP and DDDRP + MVP and MVP were pre-specified. The study was designed with a 3 arms randomization for two reasons: (i) the comparison between DDDRP + MVP and MVP allows to differentiate the impact of atrial pacing therapies from MVP, (ii) at the time of study design a pacing modality which minimizes unnecessary right ventricular pacing could not be chosen as the control group because it was not indicated by guidelines as the standard pacing mode. Even today, DDDR pacemakers without ventricular pacing minimization algorithms are still used in sinus node disease, and some reduction of RV pacing—even if less pronounced than that achievable with MVP—is obtained by programming a long AV delay or with other algorithms based on extension of the AV interval.

The occurrence of each endpoint was reported by study investigators according to pre-defined conditions and was then adjudicated by an independent Event Adjudication Committee according to the guidelines.15 The definition of permanent AF was based on clinical assessment by the centre investigator (long AF duration coupled with decision not to cardiovert the patient) and required AF to be documented during two consecutive follow-up visits, which per study design were separated by at least 3-month-long period. Cardiovascular hospitalization was defined as hospitalization, involving an overnight stay or during which death occurred, due to heart failure, ventricular or atrial tachyarrhythmias, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, transitory ischaemic attacks, syncope, acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, renal dysfunction, or other cardiovascular events.

Secondary endpoints were: the single components of the composite primary endpoint, i.e. death, cardiovascular hospitalizations or permanent AF, atrial electrical or chemical cardioversions, healthcare utilization (hospitalization or emergency room visits), symptoms, quality of life (measured by means of the EuroQol-5D questionnaire), cumulative percentage of atrial and ventricular pacing, AF burden (sum of the daily time spent in atrial tachyarrhythmias stored in the device memory divided by the follow-up duration), incidence of persistent AF (at least seven consecutive days with 22 h of device-recorded AF per day or at least 1 day with an episode of AF lasting at least 22 h—and interrupted with an electrical or chemical cardioversion), and incidence of AF with pre-specified daily durations (>5 min, >1 h, >6 h, >1 day, >2 days, >7 days and >30 days).

Sample size

The study sample size calculations have already been described.14 In brief, the study was dimensioned to compare the 2-year incidence of the composite endpoint in DDDRP + MVP vs. standard dual chamber pacing, based on the hypothesis of an incidence of 37% in the Control DDDR group and a 30% relative reduction in the DDDRP + MVP group, with a power of 80%, a confidence interval of 95%, and an assumed rate of loss to follow-up of 10%.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. The analysis set included all the patients randomized and included data through the 2-year follow-up period. To analyse the risk of the occurrence of outcome events, the Kaplan–Meier method was used and cumulative hazard curves were compared by means of the log-rank test. Cox proportional-hazard models were fitted and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed. An analysis adjusting for gender was repeated in order to assess the robustness of the univariable model. The proportional hazard assumptions were tested by using Schoenfeld residuals.

Atrial fibrillation burden and cumulative percentages of atrial pacing and ventricular pacing were compared by means of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Comparisons between baseline symptoms and symptoms at 2 years were performed by means of a logistic model, separately for each randomization group, and considering only patients with at least 24-month follow-up.

All tests were two-sided and a P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Stata 12.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

Study oversight

The steering committee designed the trial. Authors evaluated the results, and wrote or reviewed this article. Data were collected by the participating centres and were analysed under the supervision of an external statistician. All authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and the analyses and for the fidelity of adherence to the study protocol.

Results

A total of 1300 patients were enrolled in the study. The first implantation procedure took place in February 2006, the last in April 2010, and the last follow-up examination in April 2012. In all, 1166 patients were randomized and followed up, as shown in Figure 1.

The baseline characteristics of these 1166 patients are shown in Table 1. Patient profile did not differ among the three groups, except for gender. Complete information about baseline medications is shown in Supplementary material online, Appendix. Atrial lead position was the right atrium appendage in more than 91% of patients (more details in Supplementary material online, Appendix).

Table 1.

Demographics, medical history, and pacemaker indications

| Characteristics | Control DDDR (385 patients) | DDDRP + MVP (383 patients) | MVP (398 patients) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male gender, n (%)* | 205 (53.3) | 173 (45.2) | 210 (52.8) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 73 (9) | 74 (9) | 74 (9) |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous atrial tachyarrhythmias, n (%) of which documented atrial fibrillation | 385 (100.0) | 383 (100.0) | 398 (100.0) |

| 328 (87.0) | 310 (82.7) | 344 (88.7) | |

| Persistent atrial tachyarrhythmias only, n (%) | 41 (11.2) | 37 (10.3) | 34 (8.9) |

| Paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias only, n (%) | 283 (77.3) | 282 (78.3) | 305 (79.4) |

| Both paroxysmal and persistent atrial tachyarrhythmias, n (%) | 42 (11.5) | 41 (11.4) | 45 (11.7) |

| Atrial tachyarrhythmias episodes number (last 12 months), median (25th–75th percentile) | 2 (1–6) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) |

| Atrial cardioversions (last 12 months), n (%) | 85 (23.4) | 100 (26.9) | 100 (26.0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 256 (70.0) | 267 (73.0) | 284 (73.8) |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 58 (16.0) | 42 (11.5) | 52 (13.8) |

| Previous stroke or TIA, n (%) | 40 (10.6) | 37 (9.8) | 35 (8.9) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 71 (19.1) | 54 (14.7) | 62 (15.9) |

| Cardiovascular hospitalizations (last 12 months), n (%) | 125 (35.3) | 129 (35.6) | 133 (35.6) |

| Atrial tachyarrhythmias hospitalizations (last 12 months), n (%) | 90 (25.4) | 102 (28.1) | 99 (26.5) |

| NYHA Class > II, n (%) | 21 (5.5) | 11 (2.9) | 16 (4.0) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 56 (10) | 57 (11) | 57 (10) |

| PR interval (ms), median (25th–75th percentile) | 187 (160–205) | 186 (158–200) | 192 (160–210) |

| CHADS2, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.1) |

| CHADS2 > 2, n (%) | 67 (19.6) | 66 (19.2) | 63 (17.5) |

| Baseline medications | |||

| Anticoagulants, n (%) | 171 (44.7) | 166 (43.6) | 173 (44.0) |

| Antiplatelet, n (%) | 140 (36.6) | 153 (40.2) | 160 (40.7) |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs class I, n (%) | 55 (14.4) | 66 (17.3) | 67 (17.1) |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 129 (33.7) | 110 (28.9) | 139 (35.4) |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs class III, n (%) | 124 (32.4) | 105 (27.6) | 120 (30.5) |

| Pacemaker indications | |||

| Sinus node disease, n (%) | 318 (82.6) | 314 (82.0) | 334 (83.9) |

| I or II degree AV block, n (%) | 28 (7.3) | 31 (8.1) | 24 (6.0) |

| Transient complete AV block, n (%) | 11 (2.9) | 8 (2.1) | 11 (2.8) |

| Other, n (%) | 28 (7.3) | 30 (7.9) | 29 (7.3) |

*P < 0.05 DDDRP + MVP vs. the other two groups; MVP, minimal ventricular pacing, SD, standard deviation, NYHA, New York Heart Association, TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

The median (25th–75th percentile range) follow-up duration was 34 (24–45) months in the Control DDDR group, 34 (24–45) months in the DDDRP + MVP group, and 32 (23–44) months in the MVP group.

Primary composite endpoint

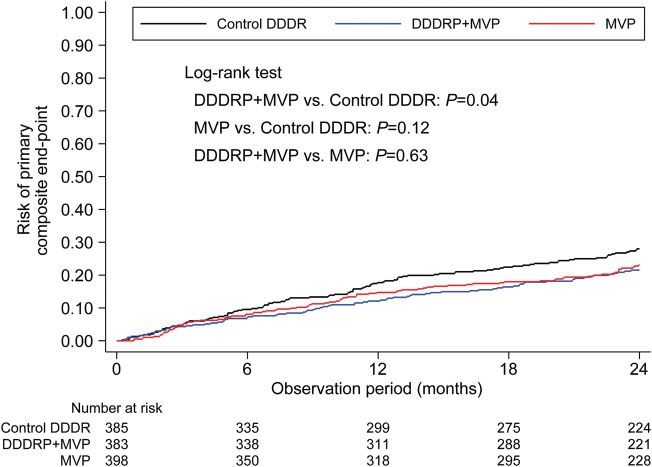

Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier curves of the risk of the primary composite endpoint.

Figure 2.

Risk of primary composite endpoint (death, cardiovascular hospitalizations, or permanent AF). MVP, managed ventricular pacing; DDDRP, atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing.

The primary endpoint, which was composed of death, cardiovascular hospitalization, or permanent AF, as shown in Table 2, occurred in 102 (26.5%) patients in the Control DDDR group, 76 (19.8%) patients in the DDDRP + MVP group (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55–0.99, P = 0.04 vs. Control DDDR), and 85 (21.4%) patients in the MVP group (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77–1.03, P = 0.13 vs. Control DDDR). The risk of primary endpoint occurrence remained virtually unchanged after adjustment for gender (adjusted HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54–0.98, P = 0.04, on comparing DDDRP + MVP with Control DDDR; adjusted HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77–1.03, P = 0.12, on comparing MVP with Control DDDR, as reported in Supplementary material online, Appendix). No significant differences in the primary endpoint were found in a post-hoc analysis comparing DDDRP + MVP with MVP [(HR 0.93 (0.68–1.26), P = 0.63; after adjustment for gender HR 0.93(0.68–1.28), P = 0.65].

Table 2.

Study results (primary and secondary endpoints)

| Control DDDR (n = 385) | DDDRP + MVP (n = 383) |

MVP (n = 398) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. Control |

vs. MVP |

vs. Control |

|||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | n (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Primary composite endpoint | |||||||||

| Death or CV hospitalization or Permanent AF | 102 (26.5) | 76 (19.8) | 0.74 (0.55–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.93 (0.68–1.26) | 0.63 | 85 (21.4) | 089 (0.77–1.03) | 0.13 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||||||||

| Death | 20 (5.2) | 16 (4.2) | 0.82 (0.42–1.58) | 0.55 | 0.87 (0.45–1.70) | 0.69 | 19 (4.8) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) | 0.84 |

| CV hospitalization | 60 (15.6) | 53 (13.8) | 0.90 (0.62–1.30) | 0.57 | 1.13 (0.77–1.67) | 0.53 | 49 (12.3) | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) | 0.23 |

| Permanent AF | 33 (8.6) | 13 (3.4) | 0.39 (0.21–0.75) | 0.004 | 0.49 (0.25–0.95) | 0.03 | 27 (68) | 0.90 (0.69–1.15) | 0.39 |

MVP, managed ventricular pacing; CV, cardiovascular; AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Secondary endpoints

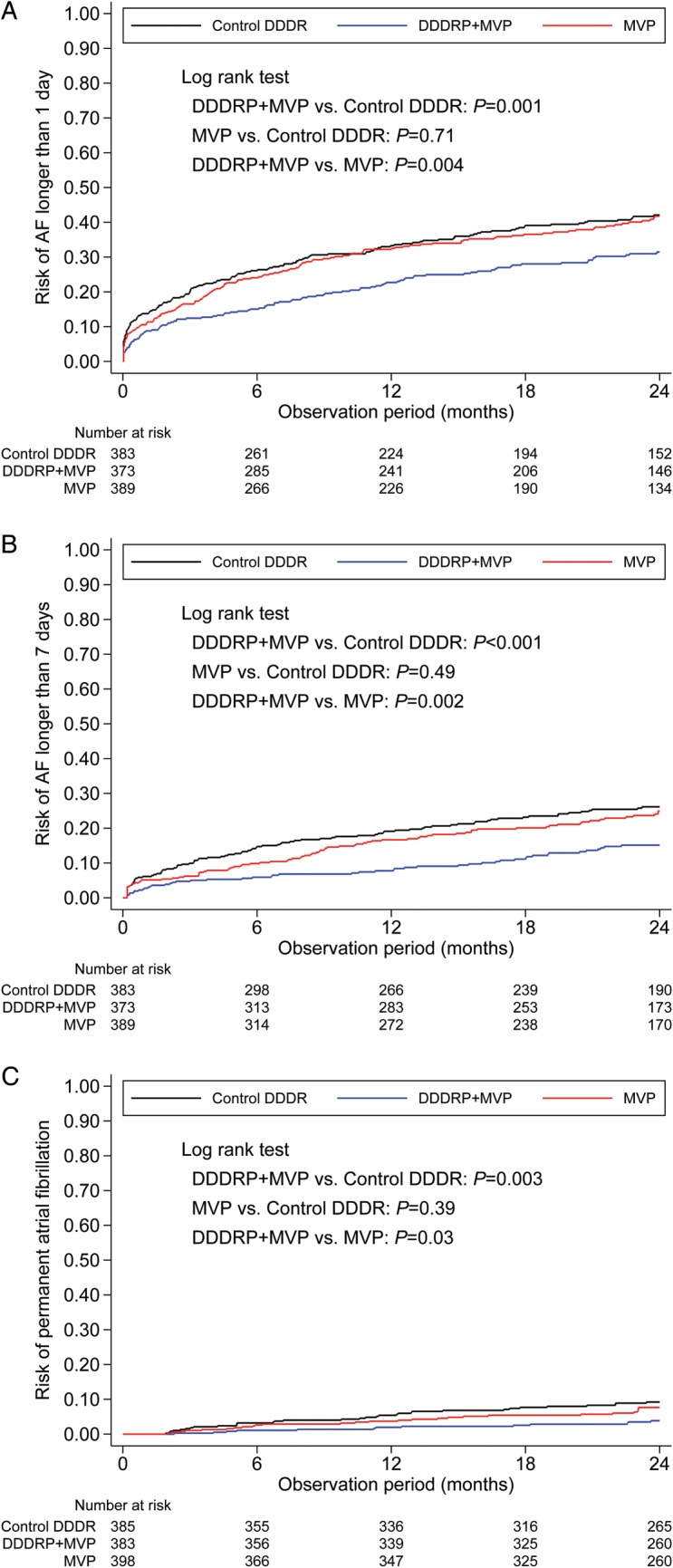

The occurrence of the secondary endpoints of death, cardiovascular hospitalizations or permanent AF is shown in Table 2, in the Kaplan–Meier risk curves of Figure 3C (permanent AF) and in the Kaplan-Meier risk curves of Supplementary material online, Appendix (death or cardiovascular hospitalizations). DDDRP + MVP was associated with a considerable lower risk of permanent AF (HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21–0.75, P = 0.004 vs. Control DDDR). At post-hoc analysis, DDDRP + MVP was associated with a lower risk of permanent AF compared with MVP (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.25–0.95, P = 0.034 vs. MVP). The risks were virtually unchanged after adjustment for gender, as reported in Supplementary material online, Appendix.

Figure 3.

Risk of AF recurrence longer than 1 day (A), AF recurrence longer than 7 days (B), and permanent AF (C). AF, atrial fibrillation; MVP, managed ventricular pacing; DDDRP, atrial preventive pacing and atrial antitachycardia pacing.

During the 2 years follow-up period, ischaemic stroke occurred in eight (0.7%) patients, four (1.0%) in the Control DDDR arm, two (0.5%) in the DDDRP + MVP arm, and two (0.5%) in the MVP arm. At the time of the ischaemic stroke, two patients were on oral anticoagulation (INR not known), while six patients were on antiplatelet therapy. Atrial fibrillation was detected by the device in the period preceding the stroke in six out of eight patients.

Electrical or pharmacological cardioversion of AF was performed less frequently in the DDDRP + MVP group [1.2 patients with cardioversions per 100 patients years (95%CI = 0.6–2.3)] compared with Control DDDR [2.1 patients with cardioversions per 100 patients years (95%CI = 1.3–3.5), P = 0.011] and with MVP [3.4 patients with cardioversions per 100 pts years (95%CI = 2.3–5.0), P < 0.001] as shown in Supplementary material online, Appendix.

Atrial fibrillation risk and burden

During follow-up, the risk of AF longer than 1 day, AF longer than 7 days, and permanent AF was significantly lower in the DDDRP + MVP group than in the Control DDDR and MVP groups as shown in Figure 3. Also the risk of an AF longer than 2 and 30 days was significantly lower in the DDDRP + MVP group than in the Control DDDR and MVP groups, while the risk of AF longer than 5 min, 1 h, and 6 h did not differ among the three study arms, as shown in Supplementary material online, Appendix.

The median AF burden was 17 min/day (25th–75th percentile 0–218 min/day) in the Control DDDR group, 9 min/day in the MVP group (25th–75th percentile 0–161 min/day, P = 0.35 vs. Control DDDR), and was significantly lower in the DDDRP + MVP group, where it was 4 min/day (25th–75th percentile 0–66 min/day, P = 0.002 vs. Control DDDR, P = 0.032 vs. MVP).

Symptoms

On comparing symptoms (angina, palpitations, dizziness, dyspnoea, fatigue, syncope, other) at the baseline and at 24 months, a general improvement was observed in all the study groups (at least one symptom in 83% of Control DDDR and DDDRP + MVP patients and in 82% of MVP patients at the baseline vs. 46% of Control DDDR and 47% of DDDR + MVP and MVP patients at 24 months; P < 0.001 in all cases). Inter-group comparison at 24 months revealed no significant differences in symptoms, except for fatigue (20% DDDRP + MVP vs. 27% Control DDDR, P = 0.049; complete data in Supplementary material online, Appendix).

Quality of life

Quality of life significantly improved during follow-up in all the groups (data in Supplementary material online, Appendix); in particular, the EuroQoL EQ-5D VAS scores showed a slight improvement at 24 months comparing DDDRP + MVP patients vs. Control DDDR (68 ± 19 vs. 64 ± 19, P = 0.027; complete data in Supplementary material online, Appendix).

Atrial and ventricular pacing percentage

The percentage of atrial pacing was significantly (P < 0.001) higher in the DDDRP + MVP group (median 93%, 25th–75th percentile 81–97%) than in Control DDDR (median 70%, 25th–75th percentile 39–90%) and MVP (median 73%, 25th–75th percentile 42–92%).

The ventricular pacing percentage was significantly lower in the DDDRP + MVP group (median 2%, 25th–75th percentile 0–11%) and in the MVP group (median 1%, 25th–75th percentile 0–9%) than in Control DDDR patients (median 53%, 25th–75th percentile 15–84%, P < 0.001). In the Control DDDR patients, mean sensed AV delay was 216 ± 62 ms, while paced AV delay was 238 ± 54 ms (the complete distributions of programmed sensed and paced AV delays are shown in Supplementary material online, Appendix).

Subgroups analysis

The effect of treatment on the primary composite endpoint and its components was investigated in five subgroups of patients, identified as a function of gender, age, presence of AV block, LVEF, and PR interval. The results are shown in Supplementary material online, Appendix. There were no significant treatment-by-subgroup interactions with regard to either the primary endpoint or any of its components.

Device-related complications and cross-overs

Pacemaker-related complications occurred in eight (2.1%) patients in the Control DDDR group, eight (2.1%) patients in the DDDRP + MVP group, and six (1.5%) patients in the MVP group. Nine of these complications were classified as serious: one (0.3%) in the Control DDDR group due to pacemaker syndrome, four (1.0%) in the DDDRP + MVP group, of whom two due to atrial lead dislodgement, one due to early battery depletion, and one due to back sternum pain possibly due to aATP, and four (1.3%) in the MVP group, of whom one due to altered sensing of RV lead, which was replaced, one due to RV lead dislodgement, one local infections with device replacement, and one due to pulmonary oedema, for which the association with the implanted device was not detailed.

Cross-overs from one study arm to another occurred in 35 (9.1%) Control DDDR patients, 13 (3.4%) DDDRP + MVP patients, and 27 (6.8%) MVP patients. Details of programming changes are reported in Supplementary material online, Appendix.

Discussion

Main study results

Our study shows that a pacing system with multiple algorithms, which combines the capabilities of atrial tachyarrhythmias prevention and termination features with minimization of right ventricular stimulation (DDDRP + MVP), is superior to conventional DDDR pacing in terms of reduction of long lasting AF and of the primary endpoint composed by death, cardiovascular hospitalizations, and permanent AF. Managed ventricular pacing alone did not significantly reduce incidence of AF or of the composite endpoint, compared with the Control DDDR group. DDDRP + MVP was superior to MVP alone in reducing long lasting and permanent AF. Our interpretation of these results is that the combined effect of MVP and aATP therapies prevented the progression of atrial tachyarrhythmias to permanent AF. In our study, permanent AF diagnosis was stated by investigators and validated by an independent event-adjudication committee according to the guidelines.1,15 The positive effect of DDDRP + MVP on arrhythmia progression is also proven by a lower use of AF cardioversions in the DDDRP + MVP group compared with Control DDDR and a lower occurrence of AF longer than 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, or 1 month, an objective finding derived from device diagnostics which has also favourable economic wimplications.16

Clinical implications

In patients with previous AF who receive dual-chamber devices, a trend towards evolution to persistent or even permanent AF is well documented and the prevention of permanent AF must be considered an important objective.17,18 Previous epidemiological studies have shown that permanent AF is associated with increased mortality and that a change in the AF pattern, i.e. evolution towards permanent AF, is an important prognostic marker for death or hospital admissions in primary care.1,19 The importance of preventing AF progression is also stressed by a recent study on oral anticoagulants, where persistent or permanent AF were found to be associated with a higher risk of stroke and a trend towards a higher all-cause mortality than paroxysmal AF.20 The ASSERT trial studying a population of pacemaker patients without prior history of AF showed an association between stroke and AF episodes as short as 6 min.4 Moreover, very recently data from the SOS study, which analysed the risk of stroke in more than 10 000 patients implanted with a dual-chamber device, indicate that AF burden is an independent predictor of ischaemic stroke and that every additional hour of device-detected AF is associated with an increased risk of cerebral ischaemic events.21 DDDRP + MVP reduces AF burden and reduces the occurrence of AF longer than 1 day, which have been associated with the increased risk of stroke in the pacemaker population.22

In our DDDRP + MVP arm, the relative and absolute risk reductions in the primary composite endpoint, in comparison with Control DDDR patients were 26 and 6%, respectively. Therefore, the number needed to treat (NNT) in order to prevent an event over 2 years is ∼17. On considering permanent AF as an endpoint, the relative and absolute risk reductions, in comparison with Control DDDR patients, were 61 and 5%, respectively. Therefore, the NNT to prevent evolution to permanent AF over 2 years is ∼20.

Recently, two observational studies with the follow-up longer than 2 years found that rhythm control achieved by means of antiarrhythmic agents was associated with a better outcome than rate control in terms of mortality and stroke reduction.23,24 However, it is unknown whether the long-term improvement in morbidity and mortality can be confirmed, if the effect of potential confounding factors is taken into account.25 In our study, successful rhythm control was achieved by means of DDDRP + MVP, as was evidenced by the lower rate of progression to permanent AF, without causing adverse effects. The result is noteworthy, since it is known from the AFFIRM data that attempts at rhythm control through antiarrhythmic agents were not entirely beneficial, in that the positive impact of sinus rhythm maintenance is offset by the adverse effects of the antiarrhythmic agents themselves.26

Atrial pacing prevention/termination therapies

In the past, some attempts to enhance the efficacy of pacing prevention/termination therapies were based on the study of the patterns of initiation of AF, as a guide to implementing a specifically identified pacing algorithm.27 Unfortunately, the variability of AF onset patterns within the same patient did not allow that concept to be applied. In the present study, we tested the synergistic effect of multiple pacing algorithms available in DDDRP + MVP, which included three atrial preventive pacing algorithms for reducing atrial tachyarrhythmia incidence, two aATP therapies for terminating regular and organized atrial tachyarrhythmias and MVP for reducing unnecessary ventricular pacing.10,12,13,28,29

Several studies in the past tested atrial preventive or antitachycardia pacing therapies, but they found contradictory results.4,6,30–32 Two recent trials, such as the ASSERT and the SAFE studies, did not find a substantial benefit of continuous atrial overdrive pacing in preventing AF occurrence.4,30 However, it is important to note that both these studies tested only one prevention algorithm, while MINERVA trial tested three preventive algorithms together with aATP and MVP. Our interpretation of the positive results of MINERVA trial, compared with previous studies, is based on several considerations; first, previous studies might have been influenced by the detrimental effects induced by unnecessary ventricular stimulation, which in our trial was minimized by MVP algorithms. Secondly, some of previous studies may have been limited by the use of AF burden or number of AF episodes as study endpoints, both being characterized by large inter- and intra-patient variability.33 Thirdly, in our study, the impact of aATP may have been higher in comparison with previous studies because of the new generation of aATP (Reactive ATP); with this new feature, the device not only attempts atrial tachyarrhythmia termination after detection but also watches for any change in the rate or regularity and then opportunistically applies aATP therapy when the episode is most vulnerable to pace termination. Finally the use of Ramp, rather than Burst+, as the first aATP therapy may have improved the efficacy of atrial tachyarrhythmias termination in comparison with previous studies.29

Pacing modalities in bradycardia patients with atrial fibrillation

The search for the most appropriate pacing modality in patients with SND, in terms of mortality, morbidity, and AF occurrence, has been the subject of many investigations.5,6–9,11 In our study, the DDDRP + MVP pacing mode reduced the primary composite endpoint compared with the Control DDDR group and reduced long-lasting AF compared with both Control DDDR and MVP pacing modes. After MOST (MOde Selection Trial) and SAVE PACe (Search AV Extension and Managed Ventricular Pacing for Promoting Atrioventricular Conduction) also a superiority of MVP alone compared with conventional DDDR pacing could have been expected.9,11 The SAVE PACe study in particular showed that the use of one among three algorithms designed to minimize ventricular stimulation reduced the occurrence of persistent AF.11 In our study, the changes associated with MVP, in comparison with control DDDR arm, did not reach statistical significance either for the primary endpoint or for long-duration AF and for permanent AF (the latter despite an increased use of cardioversion). According to us, the superiority of DDDRP + MVP compared with standard DDDR pacing confirms the importance of ventricular pacing minimization9,11 in association with aATP, while the lack of evidence in favour of MVP alone in the studied population does not contradict rather integrates SAVE PACe findings.11 Indeed, both in the DANPACE (The Danish multicenter randomised trial on single lead atrial vs. dual chamber pacing in sick sinus syndrome) and SAVE PACe trials, subgroup analyses showed that the occurrence of AF in the group of patients with prior AF history (the population enrolled in MINERVA) did not differ between the randomized pacing modes, respectively AAI vs. DDDR and MVP vs. DDDR.8,11 The electrophysiological explanation of results from SAVE PACe, DANPACE, and MINERVA trials, according to us is related to the balance between two counteracting factors, AV synchrony and pacing-induced ventricular desynchronization. DDDR pacing guarantees AV synchrony but unnecessary pacing in the right ventricle may cause ventricular remodelling due to the consequent change in electrical activation and contraction pattern of the ventricles. Managed ventricular pacing preserves a normal ventricular contraction pattern, which is expected to reduce ventricular remodelling in comparison with a higher percentage of ventricular pacing, but at the costs of allowing a prolonged AV conduction. In SAVE PACe trial, ventricular pacing percentage was 99% in the DDDR group and 9% in the group with algorithms minimizing ventricular stimulation and this likely caused the significant difference observed in persistent AF.11 In the MINERVA trial, the Control DDDR patients had long sensed and paced AV delays and ventricular pacing percentage was 53%. Even this low value, which probably represents the unsurpassable lower limit observable in clinical practice in pacemakers without algorithms to minimize ventricular pacing, could have a role in facilitating AF, but only a non-significant trend was observed in the reduction of persistent or permanent AF in MVP arm compared with Control DDDR arm. In the DANPACE trial, all patients had preserved AV conduction at baseline and to promote intrinsic conduction in the DDDR group, the AV intervals were programmed with moderately prolonged values, with a maximum of 220 ms.8 That resulted in a ventricular pacing percentage of only 65% and this probably resulted in less ventricular desynchronization. On the other hand, the benefit of preserving AV synchrony in avoiding AF is well established from large randomized trials.5–7 In the DANPACE trial, the reason for excess of AF in the AAIR group may have been the prolonged AV conduction and AV decoupling that is often observed with atrial pacing.8,34 This is in accordance with the finding that the benefit of DDDR pacing on AF in DANPACE was restricted to the subgroup with longer PQ interval at baseline.8

The limited number of device-related complications and cross overs is reassuring in terms of the safety of both DDDRP and MVP.

Limitations

The study was single-blind; therefore, the investigators were aware of the patients' assignment to the different arms. To limit the possibility to bias the ascertainment of study endpoints both permanent AF diagnoses and cardiovascular hospitalization decisions, performed by study investigators according to pre-defined conditions, were validated by an independent event-adjudication committee on the basis of patients data and hospital admissions letters and according to the guidelines. The lower use of atrial cardioversions in the DDDRP + MVP arm was reassuring about the fact that investigators did not use cardioversions to influence the primary endpoint and that the endpoint permanent AF endpoint was unlikely to be biased.

Despite randomization, the DDDRP + MVP group contained fewer males. However, on multivariable analysis (see Supplementary material online, Appendix) DDDRP + MVP remained a significant predictor of the primary composite endpoint and of permanent AF, independently from gender.

Despite investigators programmed AV pacing delays with the aim of limiting ventricular stimulation as much as possible, median ventricular pacing percentage in the Control DDDR group was 53%.

The study was designed and dimensioned to evaluate DDDRP + MVP compared with standard dual chamber pacing. The comparisons between Control DDDR and MVP and DDDRP + MVP and MVP were pre-specified. We did not perform estimations of the study power or of the sample size to perform a three-group comparison.

Conclusions

In summary in pacemaker patients with a history of atrial tachyarrhythmias, DDDRP + MVP proved superior to standard dual-chamber pacing. The 2-year incidence of the primary endpoint, composed of death, cardiovascular hospitalizations, or permanent AF, was significantly lowered through the reduction of the progression of atrial tachyarrhythmias to long-lasting and permanent AF over 2 years of follow- up.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

The MINERVA trial was sponsored by Medtronic organizations of the participating countries. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Medtronic Inc.

Conflict of interest: G.B. received modest speaker fees from Boston Scientific and Medtronic. J.S. received modest consultation fees from Medtronic and Boston Scientific and modest speaker fees for Biotronik and Sorin. L.M. received modest research grants and/or consultant/advisory board grants from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Sanofi Sorin and St. Jude Medical. L.P. received modest research grants and/or consultant/advisory board grants from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical. H.P. received modest research grants and speakers bureau grants from Medtronic. M.S. received modest research grants and/or speaker fees from Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical. R.T. received modest research grants and/or consultant/advisory board grants from Medtronic. A.G. and L.M. are employees of the Medtronic Clinical Research Institute, an entity within Medtronic Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nicoletta Grovale, M.S., Federica Gavazza, M.S., Silvia Parlanti, M.S., Marco Vimercati, M.S., and Walter Bernardini, M.S., all Medtronic Inc employees, for study management activities and for data management technical support.

References

- 1.Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1979–2030. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boriani G, Diemberger I. Globalization of the epidemiologic, clinical, and financial burden of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2012;142:1368–1370. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel CW, Grönefeld G, Ehrlich JR, Li YG, Hohnloser SH. Long-term risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation as documented by an implantable monitoring device: implications for optimal patient care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH ASSERT Investigators. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:120–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen HR, Nielsen JC, Thomsen PE, Thuesen L, Mortensen PT, Vesterlund T, Pedersen AK. Long-term follow-up of patients from a randomised trial of atrial versus ventricular pacing for sick-sinus syndrome. Lancet. 1997;350:1210–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healey JS, Toff WD, Lamas GA, Andersen HR, Thorpe KE, Ellenbogen KA, Lee KL, Skene AM, Schron EB, Skehan JD, Goldman L, Roberts RS, Camm AJ, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ. Cardiovascular outcomes with atrial-based pacing compared with ventricular pacing: meta-analysis of randomized trials, using individual patient data. Circulation. 2006;114:11–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.610303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P, Boriani G, Breithardt OA, Cleland J, Deharo JC, Delgado V, Elliott PM, Gorenek B, Israel CW, Leclercq C, Linde C, Mont L, Padeletti L, Sutton R, Vardas PE. Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, editors; Kirchhof P, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Badano LP, Aliyev F, Bänsch D, Baumgartner H, Bsata W, Buser P, Charron P, Daubert JC, Dobreanu D, Faerestrand S, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Le Heuzey JY, Mavrakis H, McDonagh T, Merino JL, Nawar MM, Nielsen JC, Pieske B, Poposka L, Ruschitzka F, Tendera M, Van Gelder IC, Wilson CM, editors. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Document Reviewers. 2013 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: The Task Force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281–2329. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen JC, Thomsen PE, Højberg S, Møller M, Vesterlund T, Dalsgaard D, Mortensen LS, Nielsen T, Asklund M, Friis EV, Christensen PD, Simonsen EH, Eriksen UH, Jensen GV, Svendsen JH, Toff WD, Healey JS, Andersen HR DANPACE Investigators. A comparison of single-lead atrial pacing with dual-chamber pacing in sick sinus syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:686–696. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Ellenbogen KA, Greenspon AJ, Freedman RA, Lee KL, Lamas GA MOde Selection Trial Investigators. Adverse effect of ventricular pacing on heart failure and atrial fibrillation among patients with normal baseline QRS duration in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107:2932–2937. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072769.17295.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillis AM, Pürerfellner H, Israel CW, Sunthorn H, Kacet S, Anelli-Monti M, Tang F, Young M, Boriani G Medtronic Enrhythm Clinical Study Investigators. Reducing unnecessary right ventricular pacing with the managed ventricular pacing mode in patients with sinus node disease and AV block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:697–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweeney MO, Bank AJ, Nsah E, Koullick M, Zeng QC, Hettrick D, Sheldon T, Lamas GA Search AV Extension and Managed Ventricular Pacing for Promoting Atrioventricular Conduction (SAVE PACe) Trial. Minimizing ventricular pacing to reduce atrial fibrillation in sinus-node disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1000–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boriani G, Padeletti L, Santini M, Gulizia M, Capucci A, Botto G, Ricci R, Molon G, Accogli M, Vicentini A, Biffi M, Vimercati M, Grammatico A. Predictors of atrial antitachycardia pacing efficacy in patients affected by brady-tachy form of sick sinus syndrome and implanted with a DDDRP device. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:714–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.40716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel CW, Ehrlich JR, Grönefeld G, Klesius A, Lawo T, Lemke B, Hohnloser SH. Prevalence, characteristics and clinical implications of regular atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from a study using a new implantable device. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:355–363. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funck RC, Boriani G, Manolis AS, Püererfellner H, Mont L, Tukkie R, Pisapia A, Israel CW, Grovale N, Grammatico A, Padeletti L MINERVA Study Group. The MINERVA study design and rationale: a controlled randomized trial to assess the clinical benefit of minimizing ventricular pacing in pacemaker patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Am Heart J. 2008;156:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boriani G, Maniadakis N, Auricchio A, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Fattore G, Leyva F, Mantovani L, Siebert M, Willich SN, Vardas P, Kirchhof P. Health technology assessment in interventional electrophysiology and device therapy: a position paper of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1869–1874. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saksena S, Hettrick DA, Koehler JL, Grammatico A, Padeletti L. Progression of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation to persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with bradyarrhythmias. Am Heart J. 2007;154:884–892. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampe B, Hammerstingl C, Schwab JO, Mellert F, Stoffel-Wagner B, Grigull A, Fimmers R, Maisch B, Nickenig G, Lewalter T, Yang A. Adverse effects of permanent atrial fibrillation on heart failure in patients with preserved left ventricular function and chronic right apical pacing for complete heart block. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101:829–836. doi: 10.1007/s00392-012-0468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidal-Perez R, Otero-Raviña F, Lado-López M, Turrado-Turrado V, Rodríguez Moldes E, Gómez-Vázquez JL, de Frutos-de Marcos C, de Blas-Abad P, Besada-Gesto R, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR BARBANZA Investigators. The change in the atrial fibrillation type as a prognosis marker in a community study: long-term data from AFBAR (Atrial Fibrillation in the BARbanza) study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2146–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Khatib SM, Thomas L, Wallentin L, Lopes RD, Gersh B, Garcia D, Ezekowitz J, Alings M, Yang H, Alexander JH, Flaker G, Hanna M, Granger CB. Outcomes of apixaban vs. warfarin by type and duration of atrial fibrillation: results from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2464–2471. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boriani G, Glotzer TV, Santini M, West TM, De Melis M, Sepsi M, Gasparini M, Lewalter T, Camm JA, Singer DE. Device detected atrial fibrillation and risk for stroke: an analysis of more than 10,000 patients from the SOS AF project (Stroke Prevention Strategies based on Atrial Fibrillation information from implanted devices) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:508–516. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capucci A, Santini M, Padeletti L, Gulizia M, Botto G, Boriani G, Ricci R, Favale S, Zolezzi F, Di Belardino N, Molon G, Drago F, Villani GQ, Mazzini E, Vimercati M, Grammatico A. Monitored atrial fibrillation duration predicts arterial embolic events in patients suffering from bradycardia and atrial fibrillation implanted with antitachycardia pacemakers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1913–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ionescu-Ittu R, Abrahamowicz M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Wynant W, Richard H, Pilote L. Comparative effectiveness of rhythm control vs rate control drug treatment effect on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsadok MA, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Rahme E, Humphries KH, Tu JV, Behlouli H, Pilote L. Rhythm versus rate control therapy and subsequent stroke or transient ischemic attack in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;126:2680–2687. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leong DP, Eikelboom JW, Healey JS, Connolly SJ. Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased mortality: causation or association? Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1027–1030. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Geller N, Greene HL, Josephson RA, Kellen JC, Klein RC, Krahn AD, Mickel M, Mitchell LB, Nelson JD, Rosenberg Y, Schron E, Shemanski L, Waldo AL, Wyse DG AFFIRM Investigators. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation. 2004;109:1509–1513. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121736.16643.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann E, Sulke N, Edvardsson N, Ruiter J, Lewalter T, Capucci A, Schuchert A, Janko S, Camm J Atrial Fibrillation Therapy Trial Investigators. New insights into the initiation of atrial fibrillation: a detailed intraindividual and interindividual analysis of the spontaneous onset of atrial fibrillation using new diagnostic pacemaker features. Circulation. 2006;113:1933–1941. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillis AM, Koehler J, Morck M, Mehra R, Hettrick DA. High atrial antitachycardia pacing therapy efficacy is associated with a reduction in atrial tachyarrhythmia burden in a subset of patients with sinus node dysfunction and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulizia MM, Piraino L, Scherillo M, Puntrello C, Vasco C, Scianaro MC, Mascia F, Pensabene O, Giglia S, Chiarandà G, Vaccaro I, Mangiameli S, Corrao D, Santi E, Grammatico A PITAGORA ICD Study Investigators. A randomized study to compare ramp versus burst antitachycardia pacing therapies to treat fast ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the PITAGORA ICD trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:146–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.804211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau CP, Tachapong N, Wang CC, Wang JF, Abe H, Kong CW, Liew R, Shin DG, Padeletti L, Kim YH, Omar R, Jirarojanakorn K, Kim YN, Chen MC, Sriratanasathavorn C, Munawar M, Kam R, Chen JY, Cho YK, Li YG, Wu SL, Bailleul C, Tse HF Septal Pacing for Atrial Fibrillation Suppression Evaluation Study Group. Atrial Fibrillation in Sick Sinus Syndrome. Septal Pacing for Atrial Fibrillation Suppression Evaluation (SAFE) Study. Circulation. 2013;128:687–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padeletti L, Pürerfellner H, Adler SW, Waller TJ, Harvey M, Horvitz L, Holbrook R, Kempen K, Mugglin A, Hettrick DA Worldwide ASPECT Investigators. Combined efficacy of atrial septal lead placement and atrial pacing algorithms for prevention of paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1189–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee MA, Weachter R, Pollak S, Kremers MS, Naik AM, Silverman R, Tuzi J, Wang W, Johnson LJ, Euler DE ATTEST Investigators. The effect of atrial pacing therapies on atrial tachyarrhythmia burden and frequency: results of a randomized trial in patients with bradycardia and atrial tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1926–1932. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Botto GL, Santini M, Padeletti L, Boriani G, Luzzi G, Zolezzi F, Orazi S, Proclemer A, Chiarandà G, Favale S, Solimene F, Luzi M, Vimercati M, DeSanto T, Grammatico A. Temporal variability of atrial fibrillation in pacemaker recipients for bradycardia: implications for crossover designed trials, study sample size, and identification of responder patients by means of arrhythmia burden. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:250–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweeney MO, Ellenbogen KA, Tang AS, Johnson J, Belk P, Sheldon T. Severe atrioventricular decoupling, uncoupling, and ventriculoatrial coupling during enhanced atrial pacing: incidence, mechanisms, and implications for minimizing right ventricular pacing in ICD patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1175–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.