Abstract

Pakistan, a developing country with limited resources, is having huge burden of diabetes and its complications. The local health care providers face limitations due to the related cost while emphasizing on self monitoring of blood glucose. The lack of health care infrastructure, non-affordability of the patients and non-existence of national guidelines are the most significant obstacles. Having realized these issues we decided to initiate a project of self monitoring of blood glucose, “BRIGHT (Better Recommendations, Implementation and Guideline development for Health care providers and their Training).

After extensive literature search, the project team, approached and communicated with “Advisory Board for the Care of Diabetes (ABCD) of Pakistan” for their expert opinion and suggestions. The board members belong to the faculty of main teaching hospitals of the four provinces of Pakistan thus ensuring national representation. The endorsement of these guidelines has paved the way for their uniform implementation all over the country.

Development of these Guidelines is the first part of BRIGHT project. In the next phase, we have started training of health care providers. Five mega programs have been conducted in this regard in the major cities. So far a patient’s log book has also been designed and distributed. Like all other guidelines, this is a living document which will be revised and updated from time to time in the light of new information which becomes available.

Key Words: Self Monitoring Blood Glucose, Diabetics, Guidelines

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a well recognized health problem, the magnitude of which is increasing very rapidly. Currently, over 382 million people in the world have diabetes representing a prevalence of nearly 8.3%. Four out of five people with diabetes live in low and middle income countries. In half of people it remains unrecognized and half of the deaths in people from diabetes occur at an age under 60 years.1 The United Nations General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution (61/225) declaring diabetes “a global pandemic” affecting global health gravely and recognized it to be a debilitating, chronic and very expensive disease, especially if associated with complications.2 Many long term randomized controlled trials, in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, have proved that intensive control of hyperglycemia significantly reduces the development of micro vascular complications.3-7 Long term follow up has proved that intensive glycemic control achieved in early stages of disease persists in terms of delayed development of macro-vascular complications even when degree of glycemic control in both intensive and control arm was comparable, an effect known as legacy effect.8 Better control of blood glucose requires appropriate monitoring. This makes self-monitoring of blood glucose an essential component of diabetes management. To ensure the effectiveness of self-monitoring, substantial diabetes education and an understanding of disease by people with diabetes themselves and by the health care providers is required. Self-monitoring provides an opportunity to document hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, thereby allowing quick and optimal response to such situations without fear of over correction. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial and other studies have proved that better metabolic control in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer and delayed micro-vascular complications.9-18 It has also been established that self-monitoring of blood glucose on regular basis and its implementation in terms of dose adjustment of insulin along with carbohydrate intake and exercise is necessary to achieve optimal metabolic control.19,20 The topics of Self Blood Glucose Monitoring have been briefly covered in National Clinical Practice Guidelines for diabetes developed in 1999.21 There is now need to develop a comprehensive recommendation document for nearly 7 million diabetics in Pakistan considering our resource constraints.

Aims of self-monitoring of blood glucose include:

To accurately assess level of metabolic control by individual therapy and achievement of realistic targets.3,9

To assist in the prevention of both acute and chronic complications of diabetes.

To reduce the effect of extreme glycemic conditions on cognitive function and mood of the individual.

To assure proper data collection in various diabetes centers in order to provide an opportunity of comparison and improvement in interdisciplinary care for people with diabetes.22 These benefits can be attained by maintaining proper record either in a form of a diary or electronic record keeping. This record should include blood glucose readings, insulin dosage, record of special circumstances like illness, eating out, exercise, any episode of hypoglycemia and its severity and any episode of ketonuria or ketonemia.

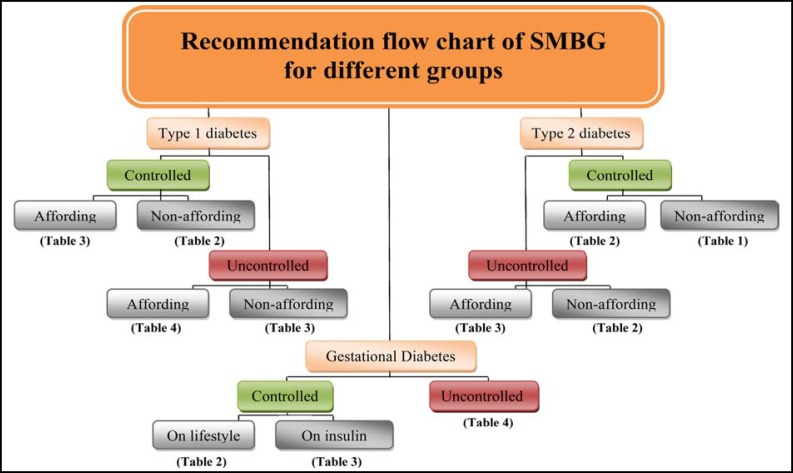

Better Recommendations, implementation and Guideline development for Health care providers and their Training (BRIGHT) [ Flow chart].

Flow chart

Following recommendations are proposed to guide people with diabetes and their healthcare providers in the use of Self Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG).23

SMBG recommendations would ensure that people with diabetes (and/or their care-givers) and their healthcare providers have the knowledge, skills and willingness to incorporate SMBG monitoring and therapy adjustment into their diabetes care plan, in order to attain agreed treatment goals.

SMBG should be considered at the time of diagnosis to enhance the understanding of diabetes as part of individual’s education and to facilitate timely treatment initiation and titration optimization.

SMBG should also be considered as part of ongoing diabetes self-management education to assist people with diabetes to better understand their disease and provide means to actively and effectively participate in its control and treatment, modifying behavioral and pharmacological interventions as needed, in consultation with their healthcare providers.

SMBG protocols (intensity and frequency of SMBG) should be individualized to address each individual’s specific educational, behavioral or clinical requirements in order to identify, prevent and manage acute hyper- and hypoglycemia. The requirements of the care provider for collection of data on glycemic patterns and for monitoring the impact of therapeutic decision making should also be addressed.

The purpose(s) of performing SMBG and using SMBG data should be agreed between the person with diabetes and the healthcare provider. These agreed-upon goals and actual review of SMBG data should be documented.

SMBG requires an easy procedure for patients to regularly monitor the performance and accuracy of their glucose meter.

Ketone test should be performed when needed, in type 1 individuals.

In accordance with the sick day rule, the frequency of SMBG should be increased in special situations like fever, vomiting and persistent polyuria with uncontrolled blood glucose, especially if abdominal pain or rapid breathing is present (Table I-IV).

Table-I.

BRIGHT recommended SMBG for lowest intensity

| Twice weekly Days and timings are variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Breakfast

|

|

Lunch

|

|

Dinner

|

Bed Time | |||||

| Pre | Post | P re | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Monday | ♦ | |||||||||

| Tuesday | ||||||||||

| Wednesday | ||||||||||

| Thursday | ||||||||||

| Friday | ♦ | |||||||||

| Saturday | ||||||||||

| Sunday | ||||||||||

Controlled non affording type 2 diabetes

Women with controlled gestational diabetes on lifestyle modification

Geriatric patients (aged > 70 years) controlled with or without co-morbid conditions.

Is to decided according to the time of gestation

Table-IV.

BRIGHT recommended SMBG for high intensity

|

4-6 times daily (28-42 points per week) Days and timings are variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Bed Time | |||||||

| Pre | Post | P re | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Monday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Tuesday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||

| Wednesday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||

| Thursday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||

| Friday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||

| Saturday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||

| Sunday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||

Newly diagnosed or uncontrolled affording patients with type 1 diabetes

Patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes or gestational diabetes with inter-current illness or hospitalization

Women with uncontrolled gestational diabetes on insulin

Setting Goals:

In management of diabetes, optimal glycemic control is essential. Epidemiological studies clearly correlate uncontrolled diabetes with increased risk of micro and macro vascular complications regardless of management chosen.24-26 The risk of complications is related to both fasting plasma glucose and post prandial glucose levels with some evidence favoring postprandial glucose more strongly correlates with cardiovascular complications.27-32 In well resourced societies setting up targets for glycemic control is considerably easy. We have to consider our sub optimal resources both in terms of provision and expense of management. In these situations we can expect some degree of compromise either by health care provider or by individual himself, thus making target setting a difficult task. However pre set targets are fundamental to promote health care especially where prevention is main concern. There is hardly any randomized controlled trial designed to set glycemic targets. These targets are set by almost all leading organizations including ADA (American Diabetes Association)33,34, IDF (International Diabetes Federation)35, NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) type diabetes36, Canadian Guidelines37, and AACE (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists)38 by expert consensus and based on epidemiological evidence for vascular complications associated with uncontrolled diabetes (Table-V).

Table-V.

Glycaemic targets

| Sub category | Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) | Random blood sugar (mg/dl) | Bed time blood sugar (mg/dl) | HbA1c (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational diabetes | 65 – 90 | 70-120 | 110 | < 6.0 | |

| Patients with type 2 diabetes | Recent/without complications | 80 – 120 | 80 – 160 | 100 – 140 | 6.5 – 7.0 |

| With CCF * , CKD ” , CLD ≈ , Autonomic neuropathy | 100 – 140 | 120 – 180 | 120 – 180 | 7.0 – 7.5 | |

| Patients with type 1 diabetes | < 6 years | 100 – 150 | 100 – 250 | 100 – 200 | 8.0 – 8.5 |

| 6 – 12 years | 80 - 150 | 100 – 200 | 100 – 150 | 7.0 – 8.0 | |

| 13 – 14 years | 80 – 140 | 100 – 180 | 100 – 120 | 6.5 – 7.0 | |

| > 14 years | 80 – 100 | 100 – 140 | 100 – 120 | < 6.5 |

Congestive cardiac failure,

Chronic kidney disease,

Chronic liver disease

Table-II.

BRIGHT recommended SMBG for moderate intensity

|

1 – 2 Times Daily depending on control of blood glucose (7-14 points per week)

Days and timings are variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Bed Time | |||||||

| Pre | Post | P re | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Monday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Tuesday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Wednesday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Thursday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Friday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Saturday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Sunday | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

Newly diagnosed or uncontrolled non affording patients with type 2 diabetes

Controlled, affording patients with type 2 diabetes

Controlled, non affording patients with type1 diabetes

Women with uncontrolled gestational diabetes on lifestyle modification

Geriatric patients (aged > 70 years) uncontrolled with or without co-morbid conditions.

Is to decided according to the time of gestation

Table-III.

BRIGHT recommended SMBG for high intensity

|

4 times daily (28 points per week) Days and timings are variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Bed Time | |||||||

| Pre | Post | P re | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Monday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Tuesday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Wednesday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Thursday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Friday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Saturday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Sunday | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

Newly diagnosed or uncontrolled affording patients with type 2 diabetes

Newly diagnosed or uncontrolled non affording patients with type 1 diabetes

Controlled affording patients with type 1 diabetes

Women with controlled gestational diabetes on insulin

Pre-operation care (duration of 1 week)

Is to decided according to the time of gestation

For special situations like Ramadan, Pilgrimage etc., we should set targets for our diabetic patients in accordance to their prior control, their expected excessive exercise, presence of complications, age of patient and weather conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the support of Assoc. Prof. Jehangir Khan, Ayub Medical College – Abbottabad, Prof. Qazi Masroor, Bahawal Victoria Hospital Quaid-e-Azam Medical College – Bahawalpur, Prof. Jamal Zafar, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences – Islamabad, Prof. Bilal Bin Younis, SIDER (Sakeena Institute of Diabetes & Endocrine Research) – Lahore, Asst. Prof.

Abdul Waheed Iqbal, Tehseel Head Quarter Hospital Dadyal Benazeer Bhutto Medical College District – Mirpur Azad Kashmir, Prof. Salma Tanweer, Nishter Hospital & Medical College – Multan, Asst. Prof. Sobia Sabir, Lady Reading Hospital – Peshawar, Assoc. Prof. Irshad Khoso, Bolan Medical Complex Hospital – Quetta, Prof. Abrar Shaikh, Ghulam Muhammad Mehar Medical College – Sukkur, Dr. Musarrat Riaz, President and Dr. Muhammad Zafar Iqbal Abbasi, Project Coordinator of National Association of Diabetes Educators of Pakistan (NADAP), Ms. Asia Qutub Uzma, Project Coordinator – Abbott Diabetes Care for their active participation in developing the Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose Guidelines.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas. 6th edition 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations GA. Resolution 61/225 Diabetes Day. 2006. Ref Type: Bill/Resolution.

- 3.Diabetes Control, Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes Control Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1995;44:968–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, Miyata T, Isami S, Motoyoshi S, et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic micro vascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6-year study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995;28:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(95)01064-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA, et al. 10 - Year Follow-up of Intensive Glucose Control in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Research Group. J Pediatr. 1994;125:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohsin F, Craig ME, Cusumano J, Chan AK, Hing S, Lee JW, et al. Discordant trends in micro vascular complications in adolescents with type 1 diabetes from 1990 to 2002. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):1974–1980. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinson DR. The Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes: changing exercise behaviours for better health. Diabetes Care. 2005:1974–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orchard TJ, Forrest KY, Kuller LH, Becker DJ. Lipid and blood pressure treatment goals for type 1 diabetes: 10-year incidence data from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1053–1059. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danne T, Weber B, Hartmann R, Enders I, Burger W, Hovener G. Long-term glycemic control has a nonlinear association to the frequency of background retinopathy in adolescents with diabetes. Follow-up of the Berlin Retinopathy Study. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1390–1396. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.12.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, Peveler RC, Neil HA. Poor prognosis of young adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1052–1057. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications. N Engl J Med. 2000;10:381–389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Writing Team for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type1 diabetes mellitus on development and progression of diabetic nephropathy: the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. JAMA. 2003;290:2159–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salardi S, Porta M, Maltoni G, Rubbi F, Rovere S, Cerutti F, et al. Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology. Infant and toddler type 1 diabetes: complications after 20 years' duration. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:829–833. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson B, Ho J, Brackett J, Finkelstein D, Laffel L. Parental involvement in diabetes management tasks: relationships to blood glucose monitoring adherence and metabolic control in young adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 1997;130:257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svoren BM, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Moreland EC, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Temporal trends in the treatment of pediatric type 1 diabetes and impact on acute outcomes. J Pediatr . 2007;150:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Clinical Practice Guidelines. Pakistan: Diabetic Association of Pakistan. A. Samad Shera; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.De-Beaufort CE, Swift PG, Skinner CT, Aanstoot HJ, Aman J, Cameron F, et al. Continuing stability of center differences in pediatric diabetes care: do advances in diabetes treatment improve outcome? The Hvidoere Study Group on Childhood Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2245–2250. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Guidelines for Self-monitoring of blood glucose in non-insulin treated type 2 Diabetes. [(Last accessed on May 28, 2014) ]. http://www.idf.org/publications/guideline-self-monitoring-blood-glucose-non-insulin-treated-type-2-diabetes.

- 24.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1995;44:968–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321 doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Service FJ, O’Brien PC. The relation of glycaemia to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the Diabetic Control and Complications Trial. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1215–1220. doi: 10.1007/s001250100635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, Yusuf S. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events. A meta-regression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:233–240. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitan EB, Song Y, Ford ES, Liu S. Is nondiabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2147–2155. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DECODE Study Group, European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Is the current definition for diabetes relevant to mortality risk from all causes and cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular diseases? . Diabetes Care. 2003;26:688–696. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorkin JD, Muller DC, Fleg JL, Andres R. The relation of fasting and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose to mortality: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging with a critical review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2626–2632. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavalot F, Pagliarino A, Valle M, Di Martino L, Bonomo K, Massucco P, et al. Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2237–2243. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes by American Diabetes Association 2005. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S4–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tests of glycemia in diabetes by American Diabetes Association 2004. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S91–S93. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Diabetes Federation. Guideline for Management of Postmeal Glucose. 2007. [Last accessed on May 28, 2014]. http://www.in.gov/7C3A840E-C90D-49EB-A44B-23723F826CCD/FinalDownload/DownloadId-3C1CBB6A182447B2D1F157AEFF8A5D80/7C3A840E-C90D-49EB-A44B-23723F826CCD/isdh/files/Guideline_PMG_final.pdf.

- 36.McIntosh A, Hutchinson A, Home PD, Brown F, Bruce A, Damerell A, et al. Clinical guidelines and evidence review for Type 2 diabetes: Blood glucose management . Sheffield: ScHARR: University of Sheffield; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee Canadian Diabetes Association 2003 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention. Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2003;27(Suppl 2):S18–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodbard HW, Blonde L, Braithwaite SS, Brett EM, Cobin RH, Handelsman Y, et al. AACE Diabetes Mellitus Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the management of diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:1–68. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.S1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]