Abstract

While a high osmolarity medium activates Cpx signaling and causes CpxR to repress csgD expression, and efflux protein TolC protein plays an important role in biofilm formation in Escherichia coli, whether TolC also responds to an osmolarity change to regulate biofilm formation in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) remains unknown. In this study, we constructed ΔtolC mutant and complement ExPEC strains to investigate the role of TolC in the retention of biofilm formation and curli production capability under different osmotic conditions. The ΔtolC mutant showed significantly decreased biofilm formation and lost the ability to produce curli fimbriae compared to its parent ExPEC strain PPECC42 when cultured in M9 medium or 1/2 M9 medium of increased osmolarity with NaCl or sucrose at 28°C. However, biofilm formation and curli production levels were restored to wild-type levels in the ΔtolC mutant in 1/2 M9 medium. We propose for the first time that TolC protein is able to form biofilm even under high osmotic stress. Our findings reveal an interplay between the role of TolC in ExPEC biofilm formation and the osmolarity of the surrounding environment, thus providing guidance for the development of a treatment for ExPEC biofilm formation.

1. Introduction

One function of bacteria is the formation of biofilms composed of a bacterial community on a surface, leading to a persistent infection in both animals and humans [1, 2]. The amount of antibiotics or disinfectants necessary to kill bacteria in a biofilm can be up to 1,000 times greater than that in corresponding planktonic cultures [3] and thus, it is difficult for a biofilm to be eradicated. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) strains are pathogens that cause a variety of clinical syndromes, including urinary tract, central nervous, circulatory, and respiratory system infections in humans and animals. Moreover, animals can be reservoirs for these ExPEC strains, which can then be transmitted to humans [4, 5]. For example, in our previous studies, ExPEC isolates detected in 315/3127 (10.1%) pigs among 19 provinces of China exhibited high multidrug resistance (MDR) [6, 7]. One of the main reasons for the threat of ExPEC strains to human health is biofilm formation by ExPEC strains. As such, uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC), a type of ExPEC strain that forms biofilms, causes urinary tract infection that is hard to eradicate with antibiotics [8].

Thus, it is essential to understand the factors that influence biofilm formation in order to find an effective way to prevent biofilm formation and destroy a biofilm. TolC belongs to the outer membrane efflux protein (OEP) family of E. coli and plays important roles in maintaining the structure and function of the outer membrane [9, 10]. Some previous studies demonstrated that some tolC mutants without TolC expression are tolerant of colicin E1 [11] and hypersensitive to certain dyes, drugs, and detergents [12]; have altered bacterial virulence [13]; and pump the biomolecules derived from bacterial self-metabolism [14, 15]. Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the correlation between efflux proteins, including TolC, and biofilm formation. The addition of efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) may reduce or abolish biofilm formation by E. coli and Klebsiella [16]. Mutants, such as E. coli K-12 strain, that lack functional multidrug efflux pump-related genes such as emrD, emrE, emrK acrD, acrE, or mdtE exhibit decreased biofilm formation [17]. Moreover, Salmonella typhimurium lacking functional TolC loses the ability to form biofilms [18]. Meanwhile, in E. coli, the CpxA-CpxR signaling together with the sigma (E) and sigma (32) signal pathways regulates gene expression in response to adverse conditions. A high osmolarity medium activates Cpx signaling and causes CpxR to repress csgD expression, an important event in regulating curli and cellulose production [19]. However, while it is recognized that efflux protein TolC protein plays important roles in E. coli K-12 strain and S. typhimurium biofilm formation, whether TolC also responds to changes in osmolarity to regulate biofilm formation in ExPEC stains remains unknown.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether TolC plays an essential role in biofilm formation of an ExPEC strain in response to different osmolarity conditions using a ΔtolC mutant strain under different osmotic conditions. Because curli fimbriae are the major component of the extracellular matrix involved in E. coli biofilm formation [20, 21], we investigated the effect of the ΔtolC mutation on curli production and curli biosynthesis-related gene expression under different osmolarity conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Media

A wild-type (WT) parent ExPEC strain PPECC42, which is highly pathogenic in mice and pigs and belongs to serotype O11, was isolated from the lung of a pig in Hunan Province of China in 2006. Plasmid pRE112 was used as a suicide vector for homologous recombination to construct the ΔtolC mutant. E. coli χ7213 was a host for pRE112 in the conjugal transfer [22]. E. coli DH5α and plasmid pHSG396 were purchased from Takara Bio (Japan). All strains were routinely cultivated in Luria-bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 μg mL−1ampicillin and 50 or 25 μg mL−1 chloramphenicol and in M9 medium or 1/2 M9 medium, a low-osmolarity minimal medium prepared by dilution of M9 medium with an equal amount of water (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| ExPEC strain PPECC42 | Wild-type (WT), porcine origin, CmS | Lab stock |

| PPECC42ΔtolC | Mutant with a 158-bp fragment deleted from the whole ORF of the tolC gene in PPECC42, CmS | This study |

| Cm-tolC | PPECC42ΔtolC strain containing plasmid pHSG-tolC, CmR | This study |

| χ7213 | Thi-1 thr-1 leuB6 fhuA21 lacY1 glnV44 ΔasdA4 recA1 RP4 2-Tc::Mu[λpir] KmR | [22] |

| χ7213-ΔtolC | χ7213 containing suicide vector pRE112ΔtolC | This study |

| DH5α | F−, φ80dlacZΔM15, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17(rk −, mk +), phoA, supE44, λ −, thi-1, gyrA96, relA1 | Takara Bio |

| Plasmid | ||

| pRE112 | oriT oriV Δasd CmR SacB, suicide vector | [22] |

| pRE ΔtolC | pRE112-inserted disrupted tolC gene in Kpn I and Sac I sites | This study |

| pHSG396 | ori lacZ CmR | Takara Bio |

| pHSG-tolC | CmR | This study |

2.2. Construction of ΔtolC Mutant and Its Complement Strain

The upstream and downstream regions of tolC gene were amplified by PCR from genomic DNAs of ExPEC strain PPECC42 with primers P1/P2 and P3/P4, respectively (Table 2). The purified upstream and downstream PCR products were mixed, and the overlapping PCR was performed. The primers P1/P4 were used again in order to amplify the disrupted tolC gene with a 158-bp fragment deleted in the tolC open reading frame (ORF). The plasmid pREΔtolC with the disrupted tolC gene was introduced into E. coli χ7213. The WT strain was cocultured with the χ7213-ΔtolC strain. Transformants resistant to chloramphenicol and sensitive to sucrose were selected on LB agar media containing chloramphenicol and sucrose and grown on LB agar media without NaCl or antibiotics to select a strain resistant to sucrose and sensitive to chloramphenicol. The final PPECC42 ΔtolC strain that lacked TolC expression was confirmed by PCR using the primers che-U/che-D (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers for PCR/RT-PCR.

| Primera | Sequence (5′-3′) | Application | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| tolC-P1 | GCCGGTACCATGAAGAAATTGCTCC Kpn I | Mutant | This study |

| tolC-P2 | CTATCGTCATAGGTTGCGTTTTTCGGCTTC | Mutant | This study |

| tolC-P3 | GAAGCCGAAAAACGCAACCTATGACGATAGCAATATGGGCCAG | Mutant | This study |

| tolC-P4 | TCCGAGCTCTCAGTTACGGAAAGGGT Sac I | Mutant | This study |

| tolC-clo-U | GGCGTCGACATGCAAATGAAGAAATTG Sal Ι | Complement | This study |

| tolC-clo-D | CGGGAATTCTCAGTTACGGAAAGGGTT EcoR Ι | Complement | This study |

| tolC-che-U | AACACGCTGCTGAAAGAA | Checking PCR | This study |

| tolC-che-D | ACGGTTTGTACGACGCTA | Checking PCR | This study |

| rrsG F | TATTGCACAATGGGCGCAAG | qRT-PCR | [23] |

| rrsG R | ACTTAACAAACCGCCTGCGT | qRT-PCR | [23] |

| csgB F | CATAATTGGTCAAGCTGGGACTAA | qRT-PCR | [24] |

| csgB R | GCAACAACCGCCAAAAGTTT | qRT-PCR | [24] |

| csgD F | CCCGTACCGCGACATTG | qRT-PCR | [24] |

| csgD R | ACGTTCTTGATCCTCCATGGA | qRT-PCR | [24] |

aSubscripts F and R indicate forward primers and reverse primers.

To rescue TolC expression in the ΔtolC mutant, the complete coding region of the tolC gene was amplified from the genomic DNAs of the WT strain by PCR using the primers clo-U/clo-D (Table 2) and inserted into pHSG396 to generate the plasmid pHSG396-tolC, which was then introduced into the ΔtolC strain using electrotransformation instruments (Bio-Rad, USA). The rescued Cm-tolC with the full-length tolC gene were selected on LB agar medium containing chloramphenicol and confirmed by PCR using primers che-U/che-D.

2.3. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determinations

To confirm the construction of ΔtolC mutant and its complement strain, antimicrobial MICs to the strain were determined on Mueller-Hinton medium (Hopebio Bio., Qingdao, China) by the standard broth doubling microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guidelines [25]. The MICs were defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited visible growth after incubation at 37°C for 18 h. The following antimicrobials were used: amikacin, gentamycin, erythromycin, streptomycin, ampicillin, florfenicol, norfloxacin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and sodium dodecyl sulfonate (SDS). Samples were assayed in triplicate, and each assay was performed at least three times.

2.4. Determination of Growth Kinetics

The 1 : 100 diluted overnight cultures were cultured in M9 or 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Samples were taken hourly, and the optical densities were measured at 600 nm (OD600) using a BioPhotometer (Eppendorf, Germany). The data acquired were from three independent experiments, with each sample measured in triplicate.

2.5. Crystal Violet Biofilm Assay

Biofilm formation was evaluated by a crystal violet assay according to the method described previously [26]. Overnight cultures in LB media were diluted 1 : 100 in fresh M9 or 1/2 M9 medium to an OD600 of 0.1. Diluted suspensions were placed in a flat-bottomed 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Nunc, Denmark) and incubated at 28°C and 100% humidity without shaking. After 2 or 5 days, the media were removed, and the wells were gently washed with sterile distilled water to remove any unbound cells. Biofilms in each well were stained with 200 μL of 1% crystal violet for 15 min. Crystal violet was removed, and each well was washed with sterile distilled water to remove any unbound dye. The stained biofilm was solubilized with 125 μL of 33% acetic acid, and the OD was measured at 630 nm (OD630) using a Universal Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek, USA) to quantify the total biofilm mass. All biofilm assays were performed three times with samples assayed in octuplicate. The strains were cultured in M9 or 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C because the WT strain could not form a biofilm in M9 or 1/2 M9 medium at 37°C or in LB medium at 28°C or 37°C (data not shown).

Based on the OD630 values of the bacterial biofilms, strains were classified according to the method described previously [26]. Briefly, the cutoff OD (ODc) was defined as three standard deviations above the mean OD of the negative control. Strains were classified as follows: OD < ODc = no biofilm production; ODc < OD < 2 × ODc = weak biofilm producer; 2 × ODc < OD < 4 × ODc = moderate biofilm producer; and OD > 4 × ODc = strong biofilm producer.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Biofilms

Strains were cultured on M9 medium or 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C for 5 days using the same procedures as described for the biofilm assay. Coverslips were immersed in the media in 24-well plates. The adhered bacteria were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and dehydrated in a series of ethanol dilutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%). The samples were then soaked in isoamyl acetate, critical point dried with CO2, and coated with gold alloy. The prepared samples were viewed and photographed using a JSM-6390 scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan).

2.7. Effects of Medium Solutes on the Role of TolC in Biofilm Formation

In order to determine if the role of TolC in biofilm formation is related to the osmolarity of the medium, a 2-fold serially diluted NaCl or sucrose solution was added to the 1/2 M9 medium to change the medium osmolarity according to the method described previously [19]. Biofilm formation in different media was assessed for both WT and ΔtolC mutant strains using the crystal violet biofilm assay.

2.8. Staining of Curli Fimbriae

Phenotypic differences in curli expression were visualized on M9 or 1/2 M9 agar plates containing 40 μg mL−1 Congo red (Amresco, USA) and 20 μg mL−1 Coomassie brilliant blue (Solarbio, China) according to the method described previously [27]. One- microliter aliquots of overnight cultures of each bacterial strain grown in LB medium were streaked onto CR agar plates and incubated at 28°C for 5 days. Strains grown on the CR agar plates were divided into four morphotypes [28, 29]: rdar (red, dry, and rough; curli and cellulose), pdar (pink, dry, and rough; cellulose only), bdar (brown, dry, and rough; curli only), and saw (smooth and white; neither curli nor cellulose). The experiments were repeated three times. Comparisons of colonies were made between the WT and mutant strains grown on the same plates.

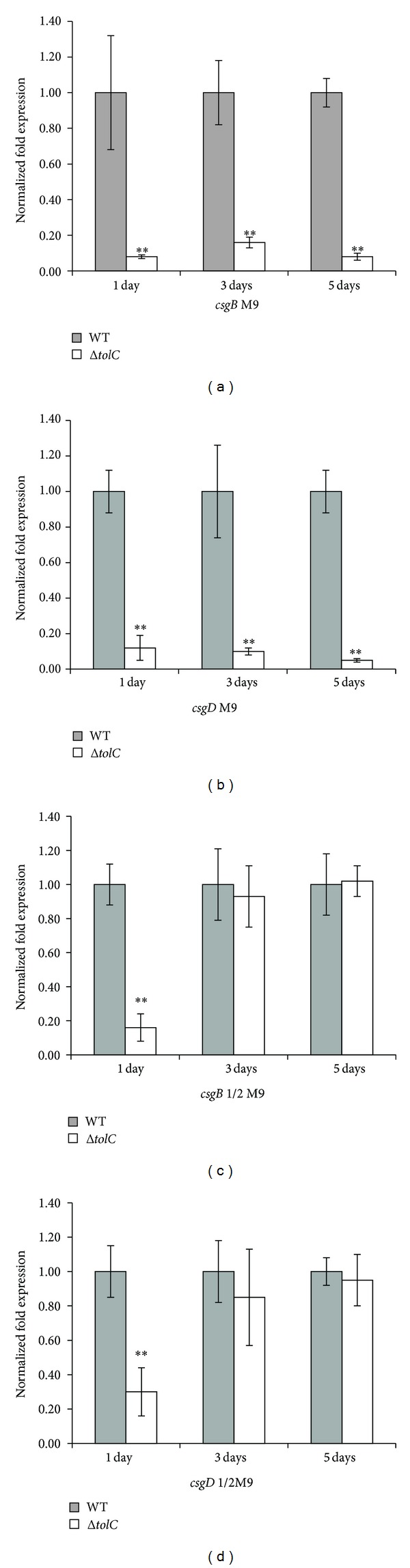

2.9. Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) of rrsG, csgD, and csgB Genes

In order to determine whether the role of TolC in curli production is at the transcriptional or assembly level, we used real-time quantitative RT-PCR to determine the expression of csgB, the gene encoding the structural component of curli [20], and csgD, a transcriptional regulator [30, 31] that forms a regulatory cascade along with sigma factors RpoS-RpoE for activation of curli gene expression and biofilm production [20]. Total RNAs of the WT and ΔtolC mutant strains grown at 28°C for 1, 3, or 5 days were extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). One microgram of RNA was digested with DNAse I (Fermentas, Canada) and reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Japan), and cDNA was directly used as the template for PCR with SYBR Select Master Mix (Life Technologies, USA) using a Bio-Rad detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) and the primers listed in Table 2. The expression level of the housekeeping gene rrsG was used to normalize the expression levels of the target genes as described previously [23]. Both the WT strain and ΔtolC mutant Ct values were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene rrsG using the delta-delta Ct (ΔΔCt) method, with ΔtolC mutant strain Ct values representing the fold change relative to that of the WT strain, which was set at 1. Comparative qRT-PCR was used to determine the average expression from four replicate wells. The assays were repeated using RNAs harvested from independent cultures of each strain in triplicate.

2.10. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses of the data for biofilm production and gene expression were performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical significance of differences between the mutant and WT strain was calculated using the unpaired Student's t-test. Differences between groups were considered significant at a P value of < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of the ΔtolC Mutant and Its Complement Strain

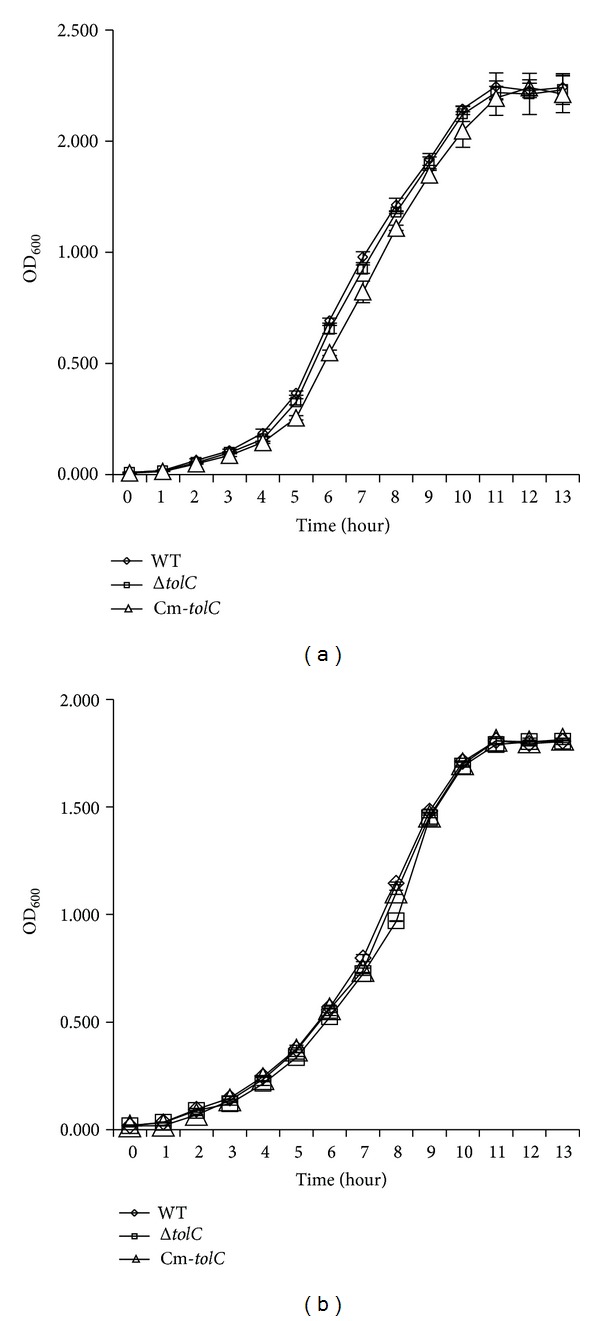

The ΔtolC mutant and its complement strain constructed from ExPEC strain PPECC42 were confirmed by PCR, and the MICs of all strains to different antibiotics and toxic chemical agents were determined. Compared with the WT strain, the tolC mutant had a 4- to 64-fold increased susceptibility to eight agents, namely, amikacin, erythromycin, florfenicol, norfloxacin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and SDS, but not to gentamycin, streptomycin, or ampicillin (Table 3). The complement strain containing plasmid pHSG-tolC restored the MDR to the levels of the WT strain. These results demonstrated the essential role of TolC in bacterial MDR as shown in some previous studies [12], indicating a correct tolC mutant was obtained. The growth kinetics of the WT and ΔtolC mutant experimental strains were detected in M9 or 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C with shaking. The results demonstrate that the ΔtolC mutant and its complement strain displayed similar growth kinetics to the WT strain, indicating that the ΔtolC mutant strain did not present a growth defect (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the experimental strains.

| MIC (μg mL−1) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AMI | GEN | ERY | STR | AMP | FLO | NOR | CHL | TET | CIP | SDS |

| WT | 16 | >512 | 128 | 512 | >512 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 256 | 256 | ≥1024 |

| ΔtolC | 4 | 512 | 4 | 512 | >512 | 4 | 64 | ≤1 | 64 | 8 | 32 |

| Cm-tolC | 16 | >512 | 128 | >512 | >512 | 64 | 512 | N.D. | 256 | 256 | ≥1024 |

AMI: amikacin; GEN: gentamycin; ERY: erythromycin; STR: streptomycin; AMP: ampicillin; FLO: florfenicol; NOR: norfloxacin; CHL: chloramphenicol; TET: tetracycline; CIP: ciprofloxacin; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfonate.

N.D.: not determined because the Cm-tolC strain has plasmid pHSG-tolC with the gene resistant to chloramphenicol.

Figure 1.

Growth kinetics of ExPEC wild-type (WT), ΔtolC, and Cm-tolC strains. WT (◊), ΔtolC strain (□), and Cm-tolC strain (△) grown in M9 media (a) or 1/2 M9 medium (b) at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Bacterial strains were grown for 13 h, and the optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) were recorded hourly. Three independent cultures were tested in triplicate, and each point on the growth curve represents an average of nine readings.

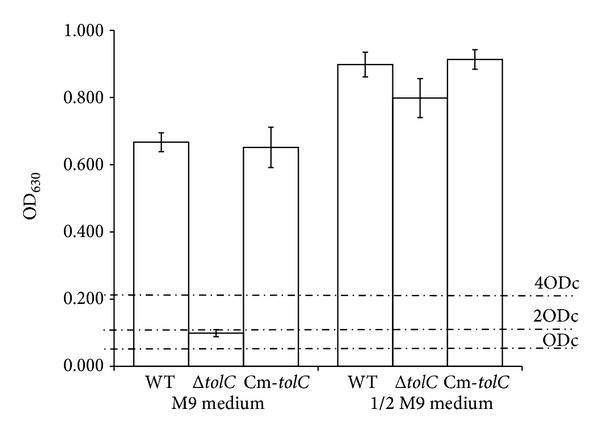

3.2. Osmolarity Affected the Capability of the ΔtolC Mutant but Not WT Strain to Form Biofilm

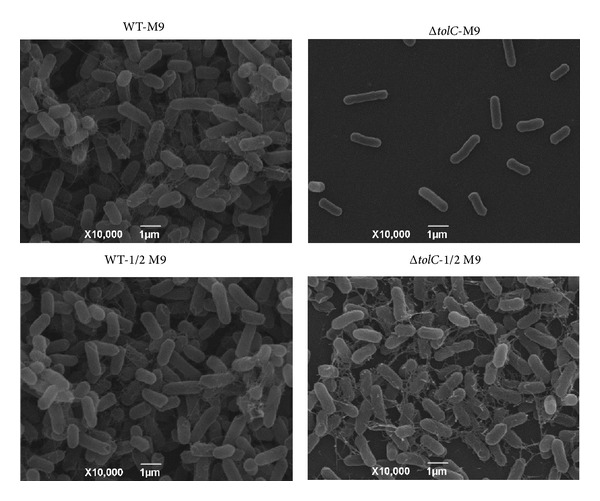

Crystal violet biofilm assay demonstrated that the WT and complement strains cultured in 1 × M9 medium for 5 days at 28°C formed a strong biofilm (OD > 4 × ODc), whereas the ΔtolC mutant strain cultured under the same conditions formed a weak biofilm (ODc < OD < 2 × ODc; Figure 2). SEM of the biofilms revealed that the WT strain bacterial cells had a large number of extracellular fimbriae and formed a dense biofilm, whereas the ΔtolC mutant strain bacterial cells did not present extracellular fimbriae and failed to form a biofilm (Figure 3). These results indicate an important role for TolC in ExPEC biofilm formation.

Figure 2.

Crystal violet biofilm assay of ExPEC strains grown in M9 or 1/2 M9 media. Biofilms were formed in 96-well plates at 28°C for 5 days and quantified by measuring the OD at 630 nm (OD630) of dissolved crystal violet. Means and standard error of the mean values of OD630 values of 24 replicate wells from three independent cultures are shown. The cutoff OD (ODc) was defined as three standard deviations above the mean OD of the negative control. Biofilm production was classified as follows: OD < ODc = no biofilm production; ODc < OD < 2 × ODc = weak biofilm production; (2 × ODc) < OD < 4 × ODc = moderate biofilm production; and 4 × ODc < OD = strong biofilm production.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the WT strain (left) and ΔtolC strain (right). All strains were incubated on glass coverslips at 28°C for 5 days in M9 medium (upper) or 1/2 M9 medium (lower) and viewed under 10,000x magnification.

As E. coli biofilm formation is regulated by osmolarity [19], the biofilm formation capabilities of the WT and ΔtolC strains cultured in a low-osmolarity 1/2 M9 medium were assessed using the crystal violet biofilm assay and SEM. Interestingly, all WT, complement, and ΔtolC mutant strains formed strong biofilms (OD > 4 × ODc; Figure 2). SEM of biofilms revealed that not only the WT strain but also the ΔtolC mutant strain bacterial cells had a large number of extracellular fimbriae and formed a dense biofilm (Figure 3), indicating that the ΔtolC mutation did not affect the ExPEC biofilm formation in a low-osmolarity medium.

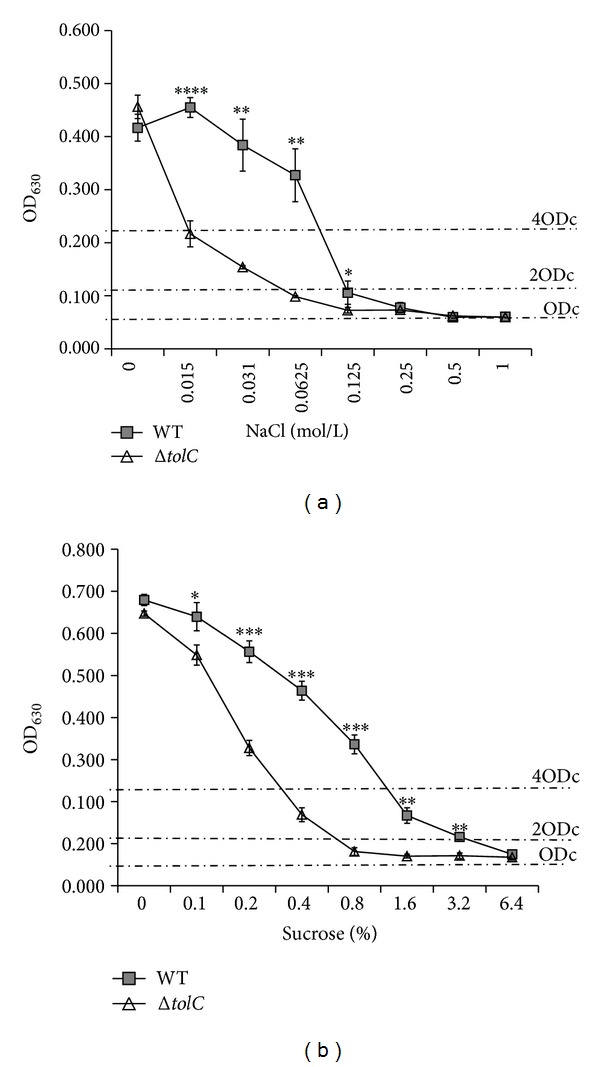

To further investigate whether the different biofilm formation capabilities of the ΔtolC mutant strain in the different media resulted from different osmolarities, we studied the biofilm formation capabilities of the WT and ΔtolC mutant strains grown in 1/2 M9 medium with different NaCl or sucrose concentrations. We found that biofilm formation of both strains reduced with an increase in the concentration of NaCl from 0.015 mol/L to 1 mol/L and sucrose from 0.1% to 6.4% (Figure 4). Although no significant difference in biofilm formation was observed between the WT strain and ΔtolC mutant cultivated in 1/2 M9 medium alone, the biofilm formation ability of the ΔtolC mutant was significantly reduced (P < 0.01) compared to that of the WT strain when the NaCl concentration was between 0.015 mol/L and 0.0625 mol/L or when the concentration of sucrose was between 0.2% and 3.2% in 1/2 M9 medium. The WT strain maintained a strong biofilm formation ability (OD > 4 × ODc) at NaCl concentrations up to 0.0625 mol/L or sucrose concentrations up to 0.8%, whereas the ΔtolC mutant merely exhibited a weak or absent biofilm formation ability (OD < 2 × ODc) at NaCl concentrations above 0.015 mol/L or sucrose concentrations above 0.4% (Figure 4). These results suggest that TolC plays an important role in tolerating different surrounding osmolarities for biofilm formation.

Figure 4.

Effect of medium osmolarity on biofilm formation by the WT and ΔtolC strains as determined by crystal violet biofilm assay. Both strains were cultivated in 1/2 M9 medium supplemented with different concentrations of NaCl (a) or sucrose (b) at 28°C for 5 days. Biofilm formation was quantified, and the results are shown as means ± standard error of the mean. Significant differences between the WT and ΔtolC strains were determined using one-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

3.3. ΔtolC Mutation Reduced Curli Production in M9 Medium, but Not in 1/2 M9 Medium

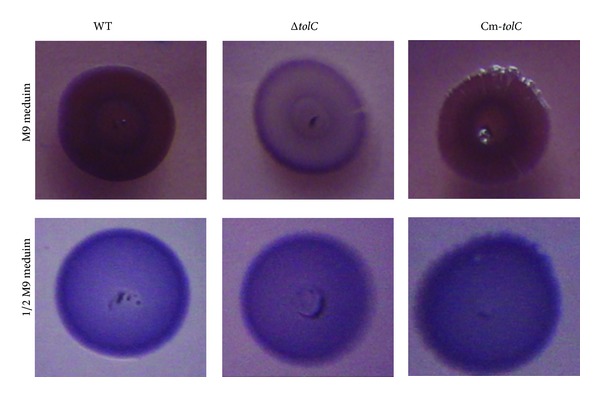

Curli is the major component of the extracellular matrix involved in E. coli biofilm formation [20, 21], and thus we next determined whether the influence of TolC on biofilm formation correlates with curli production using the Congo red assay and real-time qRT-PCR. The Congo red assay on M9-CR agar plates showed that the WT and complement strains developed a bdar morphotype and the ΔtolC mutant developed a pdar morphotype, suggesting that the ΔtolC mutation reduced curli production. However, all of the strains developed bdar morphotypes on 1/2 M9-CR agar plates, suggesting that the ΔtolC mutation had no obvious effect on the curli production in 1/2 M9 medium (Figure 5). Real-time qRT-PCR showed that, compared to the WT strain, the ΔtolC mutant strain cultured in M9 media for 1, 3, or 5 days had significantly decreased mRNA levels of csgB and csgD (P < 0.01). Although csgB and csgD expression were lower in the ΔtolC mutant strain than in the WT strain cultured in 1/2 M9 media for 1 day, no significant differences in csgB and csgD expression were observed between the two strains following culturing in 1/2 M9 medium for 3 or 5 days (Figure 6). These results indicate that the effect of osmolarity on csgB and csgD expression was temporarily restricted and that the function of TolC in curli production might be responding to different osmolarities.

Figure 5.

Effect of TolC on the production of curli fimbriae as determined by Congo red binding. All strains were cultivated on M9 agar plates (a) or 1/2 M9 agar plates (b) supplemented with Congo red at 28°C for 5 days. Visible Congo red binding was observed by the naked eye.

Figure 6.

Effect of TolC on expression of genes related to curli biosynthesis. The csgB and csgD expression levels were detected by real-time qRT-PCR. The WT strain (dark columns) and ΔtolC mutant strain (light columns) were grown in M9 or 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C for 1, 3, or 5 days. Ct values were calculated relative to those of the housekeeping rrsG gene using the ΔΔCt method, with the ΔtolC mutant strain values representing the fold change relative to those of the WT strain, which were considered 1. Bars with different hatching patterns represent the average relative expression levels using RNAs from three independent bacterial cultures. Values are shown in means ± standard error of the mean. Statistically significant fold changes between the WT and ΔtolC mutant strains were determined using one-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

To elucidate whether TolC plays an essential role in tolerating different osmotic conditions in order to maintain the biofilm formation capability of ExPEC strains, we investigated the biofilm formation, curli production, and csgB and csgD expression of a ΔtolC mutant and its complement strains constructed in this study under different osmotic conditions. We found that the ΔtolC mutant strain grown on M9 medium lost the ability to form a biofilm and exhibited reduced curli production and diminished csgB and csgD expression.

We found that the ΔtolC mutant strain did not form a biofilm and showed reduced curli production in 1 × M9 medium but had a restored biofilm formation ability and comparable curli production in 1/2 M9 medium. The correlation of osmolarity with biofilm formation and curli production was further elucidated by increasing the medium osmolarity in the 1/2 M9 medium with NaCl or sucrose. Our findings indicate that TolC plays an important role in tolerating high osmolarity to maintain the biofilm formation capability in ExPEC strains. Biofilm formation by E. coli depends on media type, culture conditions, source, and phylogeny [32, 33]. Therefore, the WT strain formed a biofilm in M9 and 1/2 M9 medium at 28°C but not at 37°C or in LB medium at 28°C or 37°C, and the ΔtolC mutant strain only formed a biofilm in 1/2 M9 medium. These phenomena were in agreement with the notion that different environmental conditions, including growth medium and conditions, influence biofilm formation [34], and in particular, osmolarity correlates with curli production [19]. Hence, the ΔtolC mutant formed a biofilm in 1/2 M9 medium (a low-osmolarity medium) but not in M9 medium. These results suggest that TolC is important for ExPEC biofilm formation. In fact, we found that efflux pump inhibitors (carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP)) inhibited WT ExPEC strain biofilm formation in M9 medium (data not shown).

We found that the absence of TolC significantly reduced curli production. This finding agrees with those of some previous studies in E. coli and S. typhimurium [16–18]. In fact, curli fimbriae are the major components of the extracellular matrix involved in E. coli biofilm formation [20] and play important roles in the initial bacteria-surface interactions and subsequent bacteria-bacteria interactions and biofilm formation [20, 21, 35].

We found that the gene expression levels of csgB and csgD in the ΔtolC mutant strain were significantly lower than those in the WT strain within the first 24 hours of culture (P < 0.01), but restored in 1/2 M9 medium at 3 and 5 days. This csgD repression, resulting in low curli production in response to a high osmolarity by NaCl and sucrose, was mediated by CpxR protein and global regulatory protein H-NS [19]. Perhaps the ΔtolC mutation may alter the Cpx and/or H-NS pathway to affect the outer membrane integrity by regulating the expression of outer membrane proteins, such as OmpF and OmpC [9, 36]. The ΔtolC mutation may also cause accumulation of toxic metabolites inside the cell, which activates the BaeSR and CpxR stress response pathways [37, 38]. Therefore, these outcomes in turn influence the response to high osmolarity stress in the ΔtolC mutant strain. We speculate that, under a low osmolarity environment, the effect of the ΔtolC mutation might not be obvious, but, under a high-osmolarity environment, the ability of the ΔtolC mutant to respond to stress from the surrounding environment was compromised.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we found for the first time that TolC influences ExPEC biofilm formation and curli production by responding to a high-to-medium osmolarity change. Our findings provide insight into why ExPEC stains maintain their biofilm formation capability even under high osmotic stress and thus will contribute to the development of a treatment strategy targeting ExPEC biofilm formation. However, further study of how TolC copes with high osmotic stress to maintain the biofilm formation and curli production capabilities of ExPEC stains is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Guo Aizhen (College of Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China) for the generous donation of the plasmid pRE112 and Dr. Wenzhou Hong at Medical College of Wisconsin for advice on the paper. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31030065) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China (no. 2011QC048).

Conflict of Interests

All the authors claimed no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clutterbuck AL, Woods EJ, Knottenbelt DC, Clegg PD, Cochrane CA, Percival SL. Biofilms and their relevance to veterinary medicine. Veterinary Microbiology. 2007;121(1-2):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito A, Taniuchi A, May T, Kawata K, Okabe S. Increased antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli in mature biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(12):4093–4100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02949-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bélanger L, Garenaux A, Harel J, Boulianne M, Nadeau E, Dozois CM. Escherichia coli from animal reservoirs as a potential source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli . FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2011;62(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mora A, Viso S, Lopez C, et al. Poultry as reservoir for extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli O45:K1:H7-B2-ST95 in humans. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013;167(3-4):506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang X, Tan C, Zhang X, et al. Antimicrobial resistances of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from swine in China. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2011;50(5):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan C, Tang X, Zhang X, et al. Serotypes and virulence genes of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from diseased pigs in China. Veterinary Journal. 2012;192(3):483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitra A, Palaniyandi S, Herren CD, Zhu X, Mukhopadhyay S. Pleiotropic roles of uvry on biofilm formation, motility and virulence in uropathogenic escherichia coli CFT073. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055492.e55492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morona R, Reeves P. The tolC locus of Escherichia coli affects the expression of three major outer membrane proteins. Journal of Bacteriology. 1982;150(3):1016–1023. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1016-1023.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morona R, Manning PA, Reeves P. Identification and characterization of the TolC protein, an outer membrane protein from Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 1983;153(2):693–699. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.693-699.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang J, Zhong X, Tai PC. Interactions of dedicated export membrane proteins of the colicin V secretion system: CvaA, a member of the membrane fusion protein family, interacts with CvaV and TolC. Journal of Bacteriology. 1997;179(20):6264–6270. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6264-6270.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulavik MC, Houseweart C, Cramer C, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001;45(4):1126–1136. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1126-1136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckley AM, Webber MA, Cooles S, et al. The AcrAB-TolC efflux system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plays a role in pathogenesis. Cellular Microbiology. 2006;8(5):847–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatsumi R, Wachi M. TolC-dependent exclusion of porphyrins in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(18):6228–6233. doi: 10.1128/JB.00595-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hantke K, Winkler K, Schultz JE. Escherichia coli exports cyclic AMP via TolC. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(5):1086–1089. doi: 10.1128/JB.01399-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Kvist M, Hancock V, Klemm P. Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(23):7376–7382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01310-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumura K, Furukawa S, Ogihara H, Morinaga Y. Roles of multidrug efflux pumps on the biofilm formation of Escherichia coli K-12. Biocontrol Science. 2011;16(2):69–72. doi: 10.4265/bio.16.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baugh S, Ekanayaka AS, Piddock LJV, Webber MA. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67(10):2409–2417. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks228.dks228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jubelin G, Vianney A, Beloin C, et al. CpxR/OmpR interplay regulates curli gene expression in response to osmolarity in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187(6):2038–2049. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2038-2049.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart MM, Chapman MR. Curli biogenesis and function. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2006;60:131–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beloin C, Roux A, Ghigo J-M. Escherichia coli biofilms. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2008;322:249–289. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Z, Xue Y, Wu B, et al. Subcutaneous vaccination with attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis C500 expressing recombinant filamentous hemagglutinin and pertactin antigens protects mice against fatal infections with both S. enterica serovar Choleraesuis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76(5):2157–2163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01495-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Kim Y, Cho MH, Wood TK. Transcriptomic analysis for genetic mechanisms of the factors related to biofilm formation in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Current Microbiology. 2011;62(4):1321–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9862-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garavaglia M, Rossi E, Landini P. The pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic pathway modulates production of biofilm determinants in Escherichia coli . PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031252.e31252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically. 7th edition. approved standard M7-A7 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stepanović S, Vuković D, Dakić I, Savić B, Švabić-Vlahović M. A modified microtiter-plate test for quantification of staphylococcal biofilm formation. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2000;40(2):175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd SJ, Ritchie JM, Rojas-Lopez M, et al. A double, long polar fimbria mutant of Escherichia coli O157:H7 expresses curli and exhibits reduced in vivo colonization. Infection and Immunity. 2012;80(3):914–920. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05945-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zogaj X, Bokranz W, Nimtz M, Römling U. Production of cellulose and curli fimbriae by members of the family Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71(7):4151–4158. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4151-4158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bokranz W, Wang X, Tschäpe H, Römling U. Expression of cellulose and curli fimbriae by Escherichia coli isolated from the gastrointestinal tract. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2005;54(12):1171–1182. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerstel U, Römling U. The csgD promoter, a control unit for biofilm formation in Salmonella typhimurium. Research in Microbiology. 2003;154(10):659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chirwa NT, Herrington MB. CsgD, a regulator of curli and cellulose synthesis, also regulates serine hydroxymethyltransferase synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology. 2003;149(2):525–535. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skyberg JA, Siek KE, Doetkott C, Nolan LK. Biofilm formation by avian Escherichia coli in relation to media, source and phylogeny. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2007;102(2):548–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naves P, Del Prado G, Huelves L, et al. Measurement of biofilm formation by clinical isolates of Escherichia coli is method-dependent. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2008;105(2):585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reisner A, Krogfelt KA, Klein BM, Zechner EL, Molin S. In vitro biofilm formation of commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli strains: impact of environmental and genetic factors. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(10):3572–3581. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3572-3581.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikuchi T, Mizunoe Y, Takade A, Naito S, Yoshida S. Curli fibers are required for development of biofilm architecture in Escherichia coli K-12 and enhance bacterial adherence to human uroepithelial cells. Microbiology and Immunology. 2005;49(9):875–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misra R, Reeves PR. Role of micF in the tolC-mediated regulation of OmpF, a major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli K-12. Journal of Bacteriology. 1987;169(10):4722–4730. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4722-4730.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zgurskaya HI, Krishnamoorthy G, Ntreh A, Lu S. Mechanism and function of the outer membrane channel TolC in multidrug resistance and physiology of Enterobacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2:189–884. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leblanc SKD, Oates CW, Raivio TL. Characterization of the induction and cellular role of the BaeSR two-component envelope stress response of Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(13):3367–3375. doi: 10.1128/JB.01534-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]