Abstract

A visual world experiment examined the time course for pragmatic inferences derived from visual context and contrastive intonation contours. We used the construction It looks like an X pronounced with either (a) a H* pitch accent on the final noun and a low boundary tone, or (b) a contrastive L+H* pitch accent and a rising boundary tone, a contour that can support contrastive inference (e.g., It LOOKSL+H* like a zebra L-H%...(but it is not)). When the visual display contained a single related set of contrasting pictures (e.g. a zebra vs. a zebra-like animal), effects of LOOKSL+H* emerged prior to the processing of phonemic information from the target noun. The results indicate that the prosodic processing is incremental and guided by contextually-supported expectations. Additional analyses ruled out explanations based on context-independent heuristics that might substitute for online computation of contrast.

Keywords: Prosody, contrastive accent, pragmatic inference, visual world eye-tracking

1. Introduction

The message a speaker intends to convey (speaker meaning) frequently includes information not made explicit in the utterance (Grice, 1975). Pragmatic inference is therefore crucial for the successful and efficient use of resources in conversation (Levinson, 2000): Listening to a speaker who made explicit everything she intended to convey would be like watching a movie in which each event unfolds in real time.

A widely held assumption in psycholinguistics is that pragmatic inference is slower and more resource-intensive than “core” aspects of sentence processing (e.g., Clifton & Ferreira, 1989). A primary example is online processing of scalar implicatures based on the English quantifier some. Some can trigger the pragmatic interpretation “some but not all”, as well as the semantic interpretation “some and possibly all”. Several studies find that comprehension of pragmatic some is significantly delayed compared to its semantic counterpart (Bott & Noveck, 2004; Huang & Snedeker, 2009, 2011). This assumption helps motivate Levinson's (2000) influential proposal that common inferences might be pre-compiled as automatically generated defaults, enabling listeners to bypass slow and resource-intensive pragmatic inference.

However, other recent studies suggest that listeners can in fact rapidly use contextually-supported expectations to facilitate pragmatic inference. For example, pragmatic some is computed without apparent delay when (a) it is well-supported by context and (b) accessible, more natural lexical alternatives are unavailable (Grodner et al., 2010, Degen & Tanenhaus, in press). These studies are part of a broader theoretical shift toward viewing efficient language comprehension as arising from expectations based on linguistic and non-linguistic context (e.g., Altmann & Kamide, 1999; Chambers, Tanenhaus et al., 2002; Chambers, Tanenhaus & Magnuson, 2004; Levy, 2008; MacDonald et al., 1994; Spivey, Tanenhaus, et al., 1998; Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton, et al., 1995; Tanenhaus, Magnuson et al., 2000).

Strong support for rapid contextual inferences comes also from online integration of prenominal modifiers in visual search tasks. For example, a prenominal adjective, such as tall in Touch the tall glass, facilitates reference resolution when a contrasting item (e.g., a short glass) is present (Sedivy, Tanenhaus et al., 1999). In addition, studies on the fall-rise pitch accent (L+H*1), which invites a contrastive interpretation, find evidence for online generation of pragmatic expectations based on visually represented contrasts (Watson et al., 2008; Weber et al., 2006). For instance, Ito and Speer (2008) find that the L+H* in Hang the red ball. Now, hang the GREENL+H*... triggers anticipatory eye-movements to an object of the same type as the preceding referent contrasted in color (e.g., a green ball).

An important limitation of previous work is that it has primarily focused on quantifiers and prenominal adjectives highlighting color and size contrast. These words might lexically encode the scale that supports a contrastive interpretation. Moreover, in studies manipulating contrastive prosody, a member of the relevant contrast set was explicitly mentioned in prior discourse. Such linguistic mention has been shown to have a privileged role in defining focus alternatives (Kim et al., under review; Wolter et al., 2011). Additionally, the dimensions of contrast were often highlighted by visual presence of minimal pairs (e.g., a red vs. green ball). These limitations make it difficult to generalize previous findings to cases in which listeners must construct a contextually-relevant contrast set online to derive pragmatic interpretations.

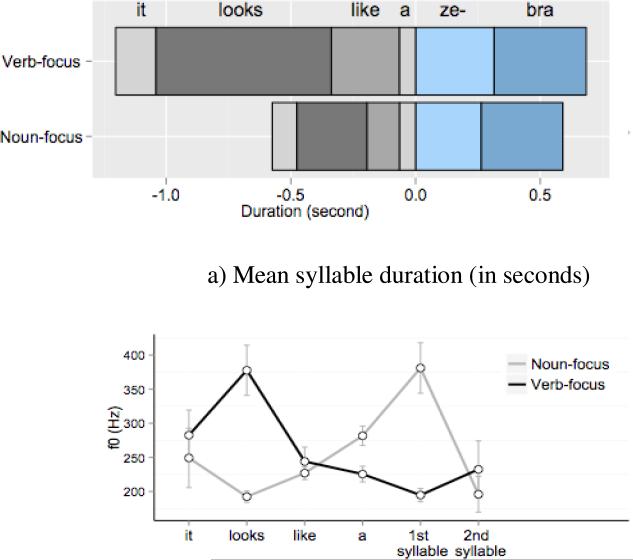

To address this, we conducted a visual world experiment (Cooper, 1974; Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton et al. 1995), using the construction It looks like an X, which can support opposing pragmatic interpretations depending on its prosodic realization. A canonical declarative prosodic contour, with nuclear pitch accent on the final noun (Figure 1-a, henceforth Noun-focus prosody), supports an affirmative interpretation without invoking contrast (e.g. “It looks like a zebra and I think it is one”; Hansen & Markman, 2005). A prosodic contour with a contrastive L+H* accent on “looks” and ending with a rising L-H% boundary tone (Figure 1-b, henceforth Verb-focus prosody) can instead trigger a negative or contradictory interpretation (e.g. “It LOOKS like a zebra but it's actually not one”; Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990; Ward & Hirschberg, 1985, Kurumada et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Waveforms (top) and pitch contours (bottom) for the utterance It looks like a zebra. The affirmative interpretation “It is a zebra” is typically conveyed by the pattern on the left (a), while the negative interpretation “It is not a zebra” is conveyed by the pattern on the right (b).

On each trial, listeners heard either Verb-focus or Noun-focus prosody in the presence of one or two pairs of visually similar animals and objects, such as a zebra and an okapi (cf. Hanna, Tanenhaus, & Trueswell, 2003). This setup allows us to ask three questions. First, can listeners construct a contrast pair based on prosodic information? Unlike prenominal modifiers, the accented verb looks does not semantically encode contrast; it is compatible with both affirmative and negative meanings depending on prosodic information. Moreover, the L+H* in the Verb-focus contour does not evoke contrast with respect to any single property of the objects (e.g., color or size). Rather, it evokes a contrast between “It LOOKS like an X” and “It IS an X”, and therefore implicates “It is not an X”. This allows us to investigate how listeners construct a linguistic scale that supports a complex contrastive interpretation.

Second, is prosodic information integrated incrementally? The Verb-focus contour contains two prosodic cues: the L+H* on looks and the rising boundary tone. If prosodic interpretation is incremental, L+H* should influence interpretation as the utterance unfolds, based on probabilistic knowledge about pitch accent patterns and boundary tones2. This incremental hypothesis can be contrasted with an account in which speaker meaning is computed only after the utterance-final boundary tone is encountered (Dennison, 2010; Dennison & Schaefer, 2010, discussed in more detail later).

Third, does the interpretation of LOOKSL+H* involve a contextually-supported inference? Levinson (2000) posited two context-independent heuristics relating linguistic form to typical pragmatic interpretation: What is simply described is stereotypically exemplified (Heuristic 2); and Marked message indicates marked situation (Heuristic 3). The marked pitch accent, LOOKS L+H*, might therefore simply lead to a general heuristic expectation for an atypical referent. Alternatively, listeners may make use of contextual information to guide their prosodic interpretation. If so, the presence of a uniquely identifiable contrast set (e.g., a zebra vs. a zebra-like animal) would facilitate the interpretation of LOOKSL+H* by supporting the contrastive inference (“It looks like an X but it is not one”).

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Twenty-four University of Rochester undergraduates who were native speakers of American English and had normal (or corrected-to-normal) vision and normal hearing were paid $10.

2.2 Stimuli

Sixteen imageable high-frequency bi-syllabic nouns with initial stress were embedded in the sentence frame It looks like an X. A native speaker of American English recorded two tokens of each item with Noun-focus and Verb-focus prosodic patterns. Figures 2a) and 2b) summarize duration and mean F0 values for each pattern. The speaker also recorded 44 filler items in which descriptions of target objects were embedded in one of four carrier phrases: It looks like an X (eight sentences)3; Can you find X?; See, it has X; Show me the one with X (12 sentences each). The filler items in constructions other than It looks like an X unambiguously referred to a single displayed picture. This was done to reinforce the assumption that the adult speaker is generally cooperative and not intentionally vague in her instructions. We avoided explicit naming (e.g., It's a butterfly). Such statements bias listeners to interpret It looks like an X as “It's not an X” because that speaker would otherwise have simply said It's an X (Kurumada et al., 2012).

Figure 2.

Mean syllable duration (a) and F0 (b) in the Verb-focus and Noun-focus conditions.

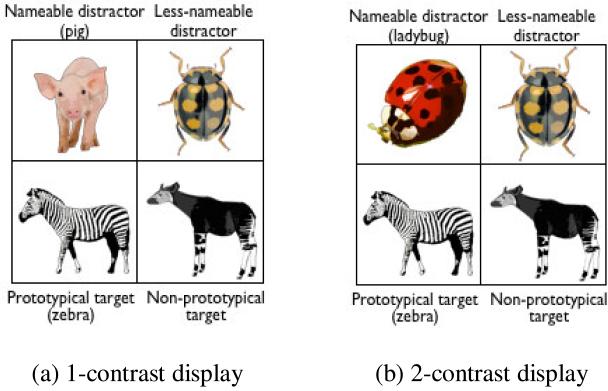

We formed contrast pairs for each target noun by selecting visually similar but comparatively infrequent items (e.g. pairing zebra with okapi). Based on Kurumada et al. (2012), we expected Noun-focus prosody to bias responses toward the more prototypical member of each pair (e.g., zebra), and Verb-focus prosody to bias responses toward the less prototypical member (e.g., okapi)4. All the visual and audio stimuli are listed in Supplementary Materials.

We constructed 60 four-picture visual displays (16 critical trials and 44 filler trials). Half of critical trials were associated with 1-contrast visual displays (one target pair and two unrelated singleton pictures, one nameable and one less-nameable; Figure 3a) and half had 2-contrast displays (one target pair and one distractor pair; Figure 3b). Likewise, 12 fillers had 1-contrast displays, 12 had 2-contrast displays, and 20 had displays consisting of a target pair and two nameable singletons5. Picture names in each display began with different segments. Eight lists were constructed by crossing item presentation order (forward vs. backward), location of prototypical and non-prototypical items in the display, and prosodic contour (Noun-focus vs. Verb-focus). Each list began with three examples to familiarize participants with the task.

Figure 3.

Sample visual displays for the 1-contrast trials (a) and the 2-contrast trials (b).

If contrastive accent is interpreted incrementally with respect to visual context, we should observe both an overall increase in fixations to the contrast set shortly after processing LOOKSL+H* and earlier gaze shifts to the non-prototypical target with 1-contrast displays, compared to 2-contrast displays. With a single contrast pair, pragmatic inference based on L+H* is sufficient to identify the target. However, context-independent heuristics would not predict an effect of display type. The atypical prosodic contour (Verb-focus prosody) should shift gaze to the atypical visual representations (i.e., non-prototypical target and less-nameable distractor) with similar time-course, irrespective of contrast-set membership.

2.3 Procedure

Participants were presented with a cover story involving a mother and child looking at a picture book. The mother commented on objects and animals to help the child identify them. Each trial began with presentation of the display. After one second of preview, participants heard a spoken sentence over Sennheiser HD570 headphones and clicked on the referent that best matched the sentence. Eye movements were monitored using a head-mounted SR Research EyeLink II system sampling at 250 Hz, with drift correction procedures performed every fifth trial.

3. Results

Our primary analyses focused on three dependent measures: picture choice, proportion of fixations to alternatives within the display, and mouse-clicking response times. Variables were assessed with multilevel generalized linear regression models utilizing the lmer function within the lme4 package in R (R, 2010; Bates, Maechler & Bolker, 2011).

3.1 Picture choices

Participants selected the correct target on 96% of the (unambiguous) filler trials. Participants selected the prototypical target picture on 65.6% of critical trials with Noun-focus prosody, but only 25.5% of trials with Verb-focus prosody. Thus, participants developed contrastive inferences based on Verb-focus prosody.

3.2 Eye-movements

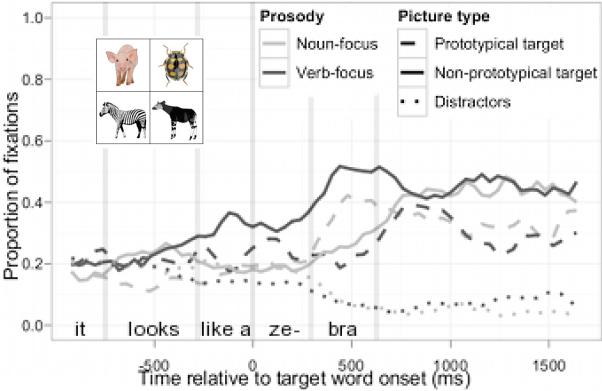

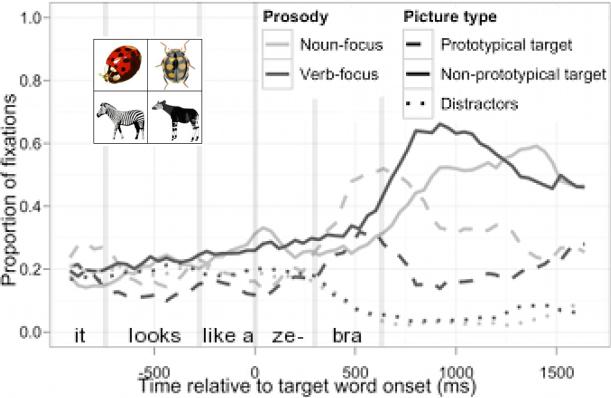

Figures 4 and 5 plot proportions of fixations to prototypical vs. non-prototypical pictures in 1-contrast and 2-contrast displays, respectively. With 1-contrast displays, Verb-focus prosody elicited more fixations to the non-prototypical target prior to the onset of the final noun. This indicates that the prosodic information, together with the lexical information, was processed incrementally. With 2-contrast displays, fixations to non-prototypical targets in response to the Verb-focus prosody and prototypical targets in response to Noun-focus prosody began to increase about 200 ms after noun-onset.

Figure 4.

Proportions of fixation to pictures in response to Noun-focus (gray lines) and Verb-focus prosody (black lines) in 1-contrast displays. The x-axis indicates duration with respect to the onset of the final noun.

Figure 5.

Proportions of fixation to pictures in response to Noun-focus (gray lines) and Verb-focus prosody (black lines) in 2-contrast displays. The x-axis indicates duration with respect to the onset of the final noun.

Because 200 ms is a conservative estimate of the earliest linguistically-mediated saccades in a four-picture display (Salverda, Kleinschmidt & Tanenhaus, 2014), we focused on the region beginning 200 ms after the offset of looks and ending 200 ms after the onset of the target word. Within this window, the effect of the contrastive accent can plausibly be observed with minimal influence from the segmental information of the final noun.

If the prosodic contours are interpreted with respect to visually-represented contrasts, the contrastive accent on looks should trigger more fixations to contrast-set members in 1-contrast trials. Linear mixed-effects regression was used to examine the effects of prosody condition (Noun-focus vs. Verb-focus), display type (1- vs. 2-contrast), and trial number on logit-transformed log-odds ratios of fixations to either member of the target contrast set (e.g., the zebra and okapi) vs. all pictures6. The main effect of prosody and the interaction between prosody condition and display type were significant (Table 1): participants made anticipatory eye-movements to the contrast set upon hearing the contrastive accent on looks when the visual context allowed them to uniquely identify one.

Table 1.

Summary of final linear regression model of mean logit-transformed log-odds ratios of fixations to target pictures vs. all pictures, in the region between 200 ms following the offset of looks and 200 ms following the onset of the target word. The final model included random intercepts and slopes for prosody and display type by participants and prosody, display type, and trial number by items.

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | –0.34 | 0.28 | –1.20 | n.s. |

| prosody=Verb-focus | 0.84 | 0.37 | 2.30 | <0.05 |

| display-type=2-contrast | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.75 | n.s. |

| trial-number | –0.15 | 0.15 | –1.00 | n.s. |

| prosody:display-type | –1.14 | 0.52 | –2.20 | <0.05 |

| display-type:trial-number | 0.72 | 0.23 | 3.18 | <0.005 |

The second set of models examined effects of prosody condition, display type, and trial number on logit-transformed log-odds ratios of fixations to non-prototypical targets vs. fixations to both target pictures. The results are summarized in Table 2. Prosody condition was significant, suggesting that the contrastive accent biased participants to fixate non-prototypical targets. Trial number and its interactions did not contribute significantly to model fit, making it unlikely that participants developed an association between prosody conditions and picture-types as a task-specific strategy.

Table 2.

Summary of final linear regression model of mean log-odds ratios of fixations to non-prototypical target pictures vs. fixations to both target pictures, in the region between 200 ms following the offset of looks and 200 ms following the onset of the target word. The final model included random intercepts and slopes for prosody and display type by participants and prosody, display type, and trial number by items.

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | –0.92 | 0.15 | –6.02 | <0.0001 |

| prosody=Verb-focus | 0.26 | 0.12 | 2.12 | <0.05 |

| display-type=2-contrast | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.26 | n.s. |

| prosody:display-type | –0.21 | 0.12 | –1.76 | <0.1 |

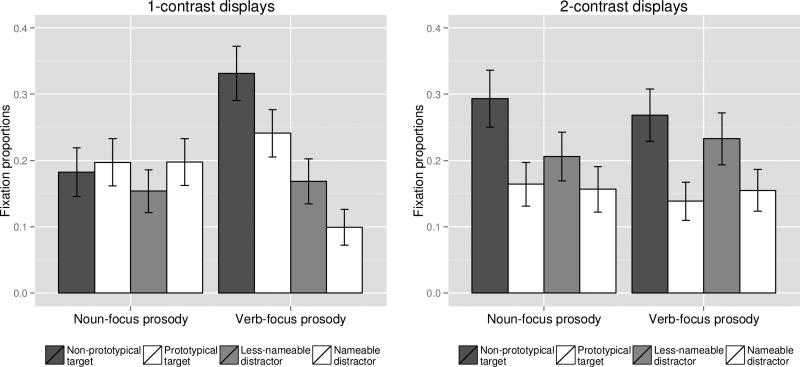

Subsequent models analyzed the display types separately. In 1-contrast trials, there was a significant bias toward the non-prototypical target with Verb-focus prosody (β=.95, t=3.07, p<.005). However, prosody condition was not a significant predictor in 2-contrast trials, in which participants were overall more likely to look at the non-prototypical target7. Figure 6 plots mean fixation proportions to all the target and distractor pictures averaged across the same window of analysis. If participants were simply associating atypical prosody with atypical visual representations (e.g., Levinson's heuristics), Verb-focus prosody should trigger more looks to the non-prototypical target and the less-nameable distractor than to the prototypical target and nameable distractor for both display types. On the contrary, in 1-contrast trials, participants fixated the target contrast set more than the less-nameable distractor, suggesting that the interpretation was derived with respect to contrast-set membership rather than to pure visual typicality.

Figure 6.

Proportions of fixations to target and distractor pictures averaged across the region between 200 ms following the offset of looks and 200 ms following the onset of the target word

3.3 Mouse-clicking response times

Response times (RTs) were calculated by subtracting the time at which the utterance ended from the time at which participants selected a picture. Effects of prosody on log-transformed RTs were dependent on whether the prototypical or non-prototypical target picture was selected (β=.509, t=2.94, p<.005). On trials with Noun-focus prosody, response times were significantly faster when a prototypical target picture was selected (mean RT=1762 ms) than when a non-prototypical target was chosen (mean RT=2364 ms, β=.272, t=3.20, p<.005). On trials with Verb-focus prosody, there was a numerical trend in the opposite direction (mean RT=2540 ms for prototypical vs. 2089 ms for non-prototypical target responses; β=.201, t=1.10, p>.10). Overall, however, Verb-focus prosody elicited slower responses (mean RT=2204 ms) than Noun-focus prosody (mean RT=1969 ms, β=.242, t=2.09, p<.05). Thus, unlike the on-line eye-tracking data, the final-choice RT data would have been consistent with delayed pragmatic inference.

4. General discussion

Contrastive accenting on looks elicited early eye-movements to non-prototypical targets, suggesting that listeners used prosody incrementally to develop pragmatic expectations. The results are inconsistent with a heuristic-based account in which marked prosody directs listeners' attention to visually atypical referents irrespective of contrast-set membership, which incorrectly predicts a null effect of display types. The current study also provides novel evidence that predictive pragmatic processing based on contrastive prosody is not restricted to cases where referents are contrasted along a single perceptual dimension or a member from a contrastive set is overtly mentioned in the prior discourse. Together with recent studies showing rapid generation of context-bound implicatures (e.g., Breheny et al., 2013), the current results suggest that in constrained contexts complex pragmatic expectations can develop rapidly and incrementally.

One remaining question is how one can reconcile the apparently rapid and effortless generation of pragmatic expectations observed in the current study (see also Grodner et al., 2010; Degen & Tanenhaus, in press), with the general view that inference is slow and costly. The current results point us to two possibilities. One is that pragmatic inference consists of heterogeneous processes. The eye-movement data showed faster consideration of the non-prototypical target with Verb-focus prosody, whereas mouse-click RTs were slower. This suggests that prosodic and contextual information is integrated incrementally to generate pragmatic expectations online while pragmatic interpretations might be verified more carefully (Grodner et al., 2010).

A second possibility focuses on the role of recent experiences. As noted earlier, and in contrast to our results, Dennison (2010) and Dennison & Schafer (2010) did not observe immediate inferences with Verb-focus prosody. Their participants clicked on objects distributed among the bedrooms of two characters, as they heard instructions such as Lisa had/HADL+H* the X... If listeners made an immediate contrastive inference at HAD (i.e., Lisa HAD the bell but she no longer has it), participants should have shifted their gaze away from Lisa's bedroom. However, Dennison & Schafer did not observe such immediate effects of contrastive accent. We suspect that this is at least partly due to their within-subject prosody manipulation. They manipulated combinations of nuclear pitch accent and boundary tones, rendering some instances of L+H* incongruent with the contrastive interpretation. As the experiment progressed, participants might have adapted to the unreliability of the L+H*, down-weighting it as a predictive cue for contrastive inference. In our experiment, on the other hand, L+H* is consistently followed by an LH%.

Underlying this reasoning is an emerging view in psycholinguistics that listeners rapidly adapt to statistical properties in the input (e.g., Clayards et al., 2008; Farmer, Brown, & Tanenhaus, 2013; Fine & Jaeger, 2013; Fine et al., 2013; Jaeger & Snider, 2013; Kamide, 2012). Listeners integrate recent experience to flexibly adjust their expectations for future input, which allows them to navigate the variability and uncertainty ubiquitous in natural language (see Dell & Chang, 2013; Kleinschmidt & Jaeger, submitted). Adaptation has so far been demonstrated in on-line phonetic and syntactic processing, and has been used to argue that language processing is consistent with rational inference. We have reported preliminary evidence for adaptation effects in prosodic interpretations (Kurumada, Brown & Tanenhaus, 2012), and are currently investigating how reliability of prosodic input affects the online pragmatic processing of prosodic contours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Eve V. Clark, Christine Gunlogson and T. Florian Jaeger for valuable discussions, and to Dana Subik for support with participant testing. This research was supported by NICHD grants HD27206 and HD073890.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

We follow the ToBI convention and use H* and L+H* to distinguish two accent patterns (Beckman & Ayes, 1997; Beckman et al., 2005; Silverman et al., 1992). L and H represent a low tone and a high tone respectively and an asterisk * indicates the tone is aligned with a pitch accent. In contrast to H*, L+H* is usually characterized with a wider pitch range, a steeper rise in F0, and a slight declination of pitch contour before the rise.

Based on Boston University Radio Corpus of American English, Dainora (2001) showed that pitch accent strongly predicted boundary tone. For example, while 39% of H* pitch accents were followed by a high boundary tone, the probability increased to 59% for L+H* accents.

These filler stimuli were also recorded with the two prosodic contours (i.e., Noun-focus and Verb-focus prosody, 4 instances each) and included to mask the display characteristics of the target trials. They were always associated with a display with a contrast pair and two nameable singletons, which were not included in the analysis.

We normed the current set of visual and audio stimuli using an online survey platform. 70 participants were asked to select the picture described by the speaker. Noun-focus items elicited more responses to the prototypical target (72%) than Verb-focus items (30%).

Filler items with a contrast pair and two nameable singletons were included to mask the fact that the target trials always contained an equal number of visually typical and atypical pictures. This was done to discourage a task-specific strategy of encoding the pictures in terms of their visual typicality prior to hearing the recorded utterance.

Fixation ratios were transformed using the empirical logit function (Cox, 1972) with the number of observations set to the number of 50-ms time intervals within the analysis window. To minimize the risk of over-fitting the data, fixed effects were removed stepwise and each smaller model was compared to the more complex model using the likelihood ratio test (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008). Maximal random effects were used; in the event of convergence failure, random slopes were removed stepwise starting with the highest-order interaction terms with the least variance (Barr, Levy, Scheepers, & Tily, 2013).

We do not have an explanation as to why Noun-focus prosody in the 2-contrast condition triggered more looks to the non-prototypical target. Because this trend was not present in the 1-contrast condition, it is unlikely that listeners were simply fixating atypical-looking objects in the display.

References

- Altmann G, Kamide Y. Incremental interpretation at verbs: restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition. 1999;73(3):247–264. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen R, Davidson D, Bates D. Mixed effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, Tily HJ. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language. 2013;68:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Beckman ME, Ayers GE. Manuscript and accompanying speech materials. Ohio State University; 1993. 1997. Guidelines for ToBI labelling, version 3.0. [ http://www.ling.ohio-state.edu/research/phonetics/E_ToBI/] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman ME, Hirschberg J, Shattuck-Hufnagel S. The original ToBI system and the evolution of the ToBI framework. In: Jun S-A, editor. Prosodic typology: The phonology of intonation and phrasing. Oxford Unievrsity Press; 2005. pp. 9–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bott L, Noveck I. Some utterances are underinformative: The onset and time course of scalar inferences. Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;51:437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Breheny R, Ferguson HJ, Katsos N. Taking the epistemic step: Toward a model of on-line access to conversational implicatures. Cognition. 2013;126:423–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CG, Tanenhaus MK, Eberhard KM, Filip H, Carlson GN. Circumscribing referential domains during real-time language comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;47(1):30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CG, Tanenhaus MK, Magnuson JS. Actions and affordances in syntactic ambiguity resolution. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30:687–696. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayards M, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, Jacobs RA. Perception of speech reflects optimal use of probabilistic speech cues. Cognition. 2008;108(3):804–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton C, Ferreira F. Ambiguity in context. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1989;4(SI):77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RM. Control of eye fixation by meaning of spoken language: New methodology for real-time investigation of speech perception, memory, and language processing. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:84–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. The analysis of binary data. Methuen; London: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Dainora A. An empirically based probabilistic model of intonation in. University of Chicago Ph.D. dissertation; American English. Chicago: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Degen J, Tanenhaus MK. Scalar implicatures processing: A constraint-based approach. Cognitive Science. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12171. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell G, Chang F. The P-chain: Relating sentence production and its disorders to comprehension and acquisition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2013;369:20120394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison HY. Processing implied meaning through contrastive prosody. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Hawaii; Manoa: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison HY, Schafer A. Online construction of implicature through contrastive prosody. Proceedings of Speech prosody 2010 conference. 2010 Retrieved from Speech prosody 2010 conference website: http://speechprosody2010.illinois.edu/papers/100338.pdf.

- Farmer T, Brown M, Tanenhaus M. Prediction, explanation, and the role of generative models in language processing. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2013;36:211–212. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X12002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine AB, Jaeger TF. Evidence for implicit learning in syntactic comprehension. Cognitive Science. 2013;37(3):578–591. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine AB, Jaeger TF, Farmer T, Qian T. Rapid expectation adaptation during syntactic comprehension. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077661. [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077661] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice HP. Logic and conversation. Syntax and Semantics. 1975;3:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Grodner DJ, Klein NM, Carbary KM, Tanenhaus MK. Some, and possibly all, scalar inferences are not delayed: Evidence for immediate pragmatic enrichment. Cognition. 2010;116:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Tanenhaus MK, Trueswell JC. The effects of common ground and perspective on domains of referential interpretation. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49(1):43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MB, Markman EM. Appearance questions can be misleading: A discourse-based account of the appearance-reality problem. Cognitive Psychology. 2005;50(3):233–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Snedeker J. Online interpretation of scalar quantifiers: insight into the semantics-pragmatics interface. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;58:376–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Snedeker J. Logic and conversation revisited: Evidence for a division between semantic and pragmatic content in real-time language comprehension. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2011;26(8):1161–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Speer SR. Anticipatory effects of intonation: Eye movements during instructed visual search. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:541–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger TF, Snider N. Alignment as a consequence of expectation adaptation: Syntactic priming is affected by the prime's prediction error given both prior and recent experience. Cognition. 2013;127(1):57–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamide Y. Learning individual talkers’ structural preferences. Cognition. 2012;124(1):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Gunlogson C, Tanenhaus MK, Runner J. Kleinschmidt D, Jaeger TF, editors. Context-driven expectations about focus alternatives. Robust Speech Perception: Recognizing the familiar, generalizing to the similar, and adapting to the novel. (under review) (submitted) [Google Scholar]

- Kurumada C, Brown M, Tanenhaus MK. Prosody and pragmatic inference: It looks like speech adaptation. In: Miyake N, Peebles D, Cooper RP, editors. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Cognitive Science Society; Austin, TX: 2012. pp. 647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson SC. Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT Press; Cambridge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levy R. Expectation-based syntactic comprehension . Cognition. 2008;106(3):1126–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M, Perlmutter NJ, Seidenberg MS. Lexical nature of syntactic ambiguity resolution. Psychological Review. 1994;101(4):676–703. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Spivey-Knowlton MJ, Tanenhaus MK. Modeling thematic fit (and other constraints) within an integration competition framework. Journal of Memory and Language. 1998;38:283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert J, Hirschberg J. The meaning of intonational contours in the interpretation of discourse. In: Cohen P, Morgan J, Pollack M, editors. Intentions and plans in communication and discourse. MIT Press; 1990. pp. 271–311. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salverda AP, Kleinschmidt D, Tanenhaus MK. Immediate effects of anticipatory coarticulation. Journal of Memory and Language. 2014;71:145–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivey MJ, Tanenhaus MK. Syntactic ambiguity resolution in discourse: Modeling the effects of referential context and lexical frequency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1998;24:1521–1543. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.24.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedivy JC, Tanenhaus MK, Chambers CG, Carlson GN. Achieving incremental semantic interpretation through contextual representation. Cognition. 1999;71:109–147. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Beckman M, Pitrelli J, Ostendorf M, Wightman C, Price P, Pierrehumbert J, Hirschberg J. TOBI: a Standard for Labeling English Prosody. Proceedings of the 1992 International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (PLACE) 1992:867–870. [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Magnuson JS, Dahan D, Chambers CG. Eye movements and lexical access in spoken language comprehension: Evaluating a linking hypothesis between fixations and linguistic processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29:557–580. doi: 10.1023/a:1026464108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Spivey-Knowlton M, Eberhard K, Sedivy J. Integration of visual and linguistic information in spoken language comprehension. Science. 1995;268:1632–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.7777863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Trueswell J. Sentence comprehension. In: Miller J, Eimas P, editors. Handbook of perception and cognition, 2nd edition. vol. 11: Speech, language, and communication. Academic Press; 1995. pp. 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Tanenhaus MK, Gunlogson C. Interpreting pitch accents in on line comprehension: H* vs L+H*. Cognitive Science. 2008;32:1232–1244. doi: 10.1080/03640210802138755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward G, Hirschberg J. Implicating uncertainty: The pragmatics of fall-rise intonation. Language. 1985;61:747–776. [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Braun B, Crocker MW. Finding referents in time: Eye-tracking evidence for the role of contrastive accents. Language and Speech. 2006;49:367–392. doi: 10.1177/00238309060490030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter L, Gorman KS, Tanenhaus MK. Scalar reference, contrast and discourse: Separating effects of linguistic discourse from availability of the referent. Journal of Memory and Language. 2011;65(3):299–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.