Abstract

Plasmids are self-replicating pieces of DNA that can help dissemination of non-essential genes. Given that plasmids represent a metabolic burden to the host, mechanisms ensuring plasmid transmission to daughter cells are critical for their stable maintenance in the population. Here we review these mechanisms, focusing on two active partition strategies common to low-copy plasmids: par systems type I and II. Both involve three components: an adaptor protein, a motor protein, and a centromere, which is a sequence area in the plasmid that is recognized by the adaptor protein. The centromere-bound adaptor nucleates polymerization of the motor, leading to filament formation, which can pull plasmids apart (par I) or push them towards opposite poles of the cell (par II). No such active partition mechanisms are known to occur in high copy number plasmids. In this case, vertical transmission is generally considered stochastic, due to the random distribution of plasmids in the cytoplasm. We discuss conceptual and experimental lines of evidence questioning the random distribution model and posit the existence of a mechanism for segregation in high copy number plasmids that moves plasmids to cell poles to facilitate transmission to daughter cells. This mechanism would involve chromosomally-encoded proteins and the plasmid origin of replication. Modulation of this proposed mechanism of segregation could provide new ways to enhance plasmid stability in the context of recombinant gene expression, which is limiting for large-scale protein production and for bioremediation.

Keywords: partition, segregation, cytoskeleton, motors, DNA-binding, replication

Plasmids are self-replicating, extra-chromosomal pieces of DNA that help their hosts face environmental challenges or adapt to specific niches through the expression of selected sets of genes (1-3). Plasmid-borne genes are typically dispensable, although there is a class of large plasmids known as “chromids” that frequently encode essential genes for core physiology (4). Plasmids also contribute to evolution by facilitating horizontal dissemination of the genes they bear, frequently across species (5) .

Plasmids are typically present in multiple copies, and the copy number is relatively stable. Plasmid copy number varies widely depending on the plasmid, ranging from as few as 1-2 copies per cell for F or R1 plasmids (6) to up to 200 copies per cell for ColE1 plasmid derivatives used for recombinant gene expression (7).

Plasmids represent a significant metabolic burden for their hosts (8). The metabolic burden associated with a particular plasmid is determined both by expression of plasmid-borne products and the number of copies of plasmids within a cell (8-11). High-copy number (hcn) plasmids such as cloning vectors are typically lost from populations at a high rate in the absence of selection, likely because these constructs both exert a large metabolic burden and lack plasmid maintenance factors found on natural plasmids. Plasmid loss has been identified as a key factor limiting yield of large-scale recombinant gene expression (12), leading to substantial efforts directed at understanding the mechanisms involved in regulation of plasmid copy number and plasmid loss (13-15).

Given that expression of plasmid-borne genes only confers a selective advantage in specific environments, in order to prevent loss when conditions change, plasmids need mechanisms to ensure their transmission to daughter cells. Mechanisms for vertical plasmid propagation among bacterial hosts fall into the following three categories:

Partitioning systems: Low copy number plasmids often harbor genes whose function is to physically distribute plasmids so that each daughter cell receives at least one plasmid upon cell division (16, 17). Examples include the parRMC system of R-plasmids found within gammaproteobacteria (18, 19), the sopABC system of F-plasmids (20) and the Rep/mob systems found in Gram-positive bacteria (21). The first part of the present review describes two partitioning systems that use cytoskeletal-like structures to direct plasmid distribution.

Random segregation: For plasmids that are kept at high copy number (>15 copies/cell), the theoretical probability of plasmid-less segregation is vanishingly small (22, 23), so it has been proposed that these plasmids would not require active segregation; instead, each daughter cell receives at least one plasmid as a result of random diffusion (23). Random plasmid distribution is facilitated by multimer resolution systems; these systems use site-specific DNA recombination to resolve plasmid multimers (which reduce the effective copy number) into monomers (24, 25). The second part of the present review discusses emerging evidence questioning this random distribution model and proposes that hcn plasmid transmission does involve segregation, but that in this case partition is dependent on chromosomal, rather than plasmid-intrinsic, factors.

Post-segregational killing: Some plasmids ensure their maintenance in the population through mechanisms that selectively kill plasmid-free daughter cells (26, 27). Examples include the CcdA/B system found on F plasmids (28) and the colicin system of ColE1 plasmids (27). The CcdA/B system depends on a highly-stable cytoplasmic toxin (CcdB, a topoisomerase inhibitor) and a short-lived cognate immunity protein (CcdA) (29, 30). Plasmid-free daughter cells arising upon cell division are killed by CcdB once the immunity protein CcdA degrades (28). Thus the CcdA/B system ensures vertical transmission of plasmids to daughter cells. Similarly, colicins are plasmid-borne cytotoxic peptides and immunity proteins produced by certain strains of E. coli. Colicins kill cells lacking immunity proteins by a variety of mechanisms including nuclease activity, pore-formation in the outer membrane, and inhibition of cell wall metabolism (31). Unlike CcdB, however, colicins are secreted, which means they eliminate all plasmid-free cells in a population; not only plasmid-free progeny.

In addition to mechanisms dedicated to ensuring vertical transmission, conjugative transfer can also be considered a mechanism promoting plasmid stability, as it allows some plasmids to reestablish themselves in plasmid-less cells (32).

Active plasmid partitioning

Numerous plasmids of E. coli harbor active partitioning mechanisms, aimed at ensuring proper segregation between daughter cells. Of note, plasmid partitioning systems also serve as compatibility determinants for plasmids, excluding foreign plasmids by ensuring that only plasmids arising from pre-existing copies are faithfully segregated into daughter cells (33).

To illustrate mechanisms of active plasmid segregation, we will focus on par systems as general paradigms for plasmid partitioning. Par systems, such as the Rep/mob system found in plasmids of gram-positive bacteria, the RepABC system of alpha-proteobacteria (21, 34), or the sopABC locus of the conjugative plasmid F, are well characterized and share some commonalities with other partitioning mechanisms (16, 17).

Par systems are made up of three components: (1) a cis-acting centromeric sequence element, (2) a motor protein that derives energy from hydrolysis of nucleotide triphosphates, and (3) a DNA-binding protein that serves as an adaptor between the motor and the centromere. Adaptor binding of the centromere nucleates polymerization of the motor; polymerization and filament formation are essential for segregation.

Par systems are auto-regulated by their own DNA-binding protein (35), which may also play a role in regulation of plasmid-encoded genes by binding and silencing the promoter regions of centromere-proximal genes (36). Disruption of the regulation of these systems leads to segregation defects, and over-expression of any individual component causes plasmids to be lost at a high rate (35, 37). Par-mediated plasmid localization and segregation is independent of the cell cycle or chromosomal replication, as demonstrated in numerous studies using cephalosporin treatment or cells blocked for chromosomal replication (38, 39).

The centromeric sequence varies between different par systems and is composed of tandem arrays of either direct or inverted repeats (40-42) that establish DNA curvature (43). This curvature is likely critical for its function, as inversion of the repeated sequences (presumably altering the local topology) leads to reduced binding affinity for the adaptor protein (43). The CEN sequences in budding yeast also display curvature (44), suggesting that this property may be universal to centromeric DNA.

Par systems are classified based upon the motor proteins they encode. Type I par systems feature Walker-A P-Loop ATPases (43), whereas type II par systems are driven by actin-like ATPases (45). For both systems, polymerization is energetically favorable when monomers of the motor protein are in the ATP-bound state (46). Filaments rapidly disassemble upon ATP hydrolysis. Type I par systems use the filament disassembly to pull plasmids to the quarter-cell position prior to cell division. The sopABC locus found on the conjugative plasmid F represents a typical type I par system. Type II par systems, by contrast, bind and then separate plasmids to the cell poles by a pushing mechanism, in a process analogous to actin filament dynamics (19). The model for type II par systems is the parRMC locus found on the R1 multidrug resistance plasmid of E. coli (47).

Type I par systems appear to have been co-opted for chromosomal segregation by numerous bacterial species, as orthologous genes to sopABC are found in Bacillus subtilis, and Caulobacter crescentus, where they are critical for proper chromosomal segregation (48, 49). Type I-like centromeric sequences have been detected in prokaryotic genomes across many phyla: indeed, up to 70% of bacterial genomes may contain these sequence elements (50). Type II par systems appear to be more restricted to plasmids. However, the ParR protein is analogous to MreB and the ParR protein shares homology with FtsA, two important proteins for chromosomal segregation indicating that these systems may be evolutionarily related (51).

Type I par systems: The F-plasmid sopABC locus

Type I par systems have three elements: two protein-coding genes (sopA and sopB for the system encoded by the F-plasmid) and the centromeric sequence (sopC for the F-plasmid) (Fig. 1a). Consistent with par systems' regulatory independence from chromosomal replication, plasmids harboring sopABC genes are faithfully segregated and stably maintained in E. coli mutant backgrounds deficient for chromosome partitioning (52).

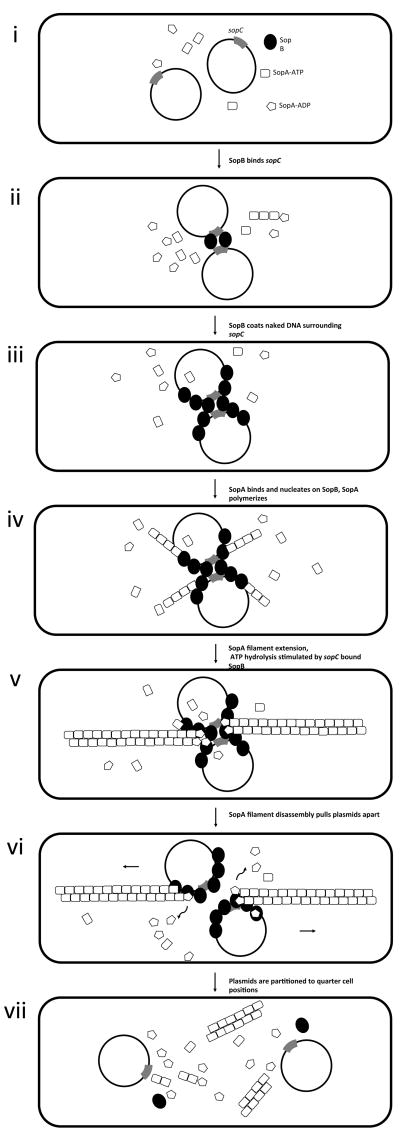

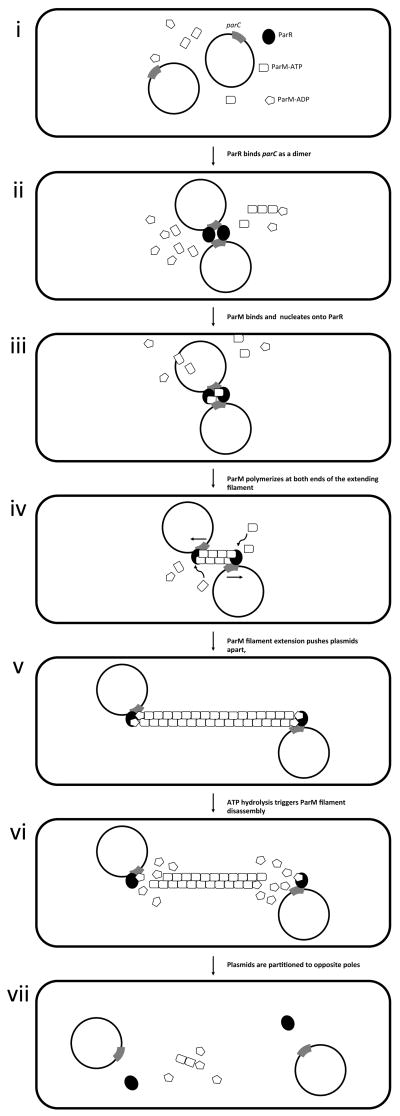

Fig. 1. Par-mediated plasmid segregation.

Type-I (a) or type-II (b) par mechanisms of segregation. Par systems have three functional elements: (1) a cis-acting centromeric sequence element, (2) an ATPase motor protein, and (3) a DNA-binding protein. The DNA-binding protein serves as an adaptor between the motor and the centromere; this protein nucleates polymerization of the motor. Polymerization is energetically favorable when monomers of the motor protein are in the ATP-bound state. Filaments rapidly disassemble upon ATP hydrolysis. (a) Type I par systems. Centromere: sopC (gray rectangle); adapter: SopB (black circle); motor protein: SopA (ATP-bound, rectangle; ADP-bound, pentagon). (i) Single F plasmids initially diffuse freely within accessible areas of the cytoplasm. (ii) SopB binds sopC from two F plasmids, bringing them together. (iii) SopB extends outward onto naked plasmid DNA. (iv) SopA nucleates onto SopB in areas where SopB is not complexed with centromeric DNA. (v) SopA polymerizes and filaments extend outward in both directions until they encounter SopB monomers in complex with sopC, (56). (vi) SopB monomers bound to sopC stimulate the ATPase of SopA, leading to a wave of ATP hydrolysis that destabilizes the filaments (57). Disassembling SopA filaments exert tension on SopB, pulling the plasmids apart in opposite directions (53). (vii) Filament disassembly drives plasmids to opposite poles of the cell. (b) Type II par systems. Centromere: parC (gray rectangle); adapter: ParR (black circle); motor protein: ParM (ATP-bound, rectangle; ADP-bound, pentagon). (i) Single R1 plasmids initially diffuse freely within a confined area. (ii) When two plasmids encounter each other in the cell, they become tethered and move as a single unit, through binding of ParR to parC. (iii) This association between ParR and parC stabilizes the ends of ParM filaments. (iv) ParM monomers are added to the ends of ParR-bound filaments. (v) The bi-directional elongation of ParM filaments drives plasmids to opposite poles of the cell during segregation. (vi) ATP hydrolysis triggers ParM filament disassembly. (vii) Pairs of plasmids end up in opposite ends of the cell. Thus, whereas in type I systems, the plasmids are “pulled” by filament disassembly (process akin to kinetochore motion during eukaryotic mitosis), in type II par systems, plasmid pairs are “pushed” by filament polymerization in a process akin to actin filament dynamics.

The motor protein, SopA, is a Walker-A type P-loop ATPase with a non-specific DNA-binding domain (20). In the absence of DNA or SopB, the kinetics of ATP hydrolysis by SopA are extremely slow (20). SopA forms filamentous structures in vitro and in vivo only in the presence of ATP (53). Both filament assembly and disassembly are required for proper segregation by type I par systems, as plasmids encoding mutant alleles of SopA that are deficient in ATP-binding (54) and also mutants that cannot hydrolyze ATP (54) are lost at a high rate.

The interaction between SopA and SopB is necessary for proper segregation (55). The ATP-ase activity of SopA is cooperative and stimulated both by naked DNA and by interaction with SopB in complex with sopC DNA (56). Paradoxically, even though SopB-sopC complexes stimulate SopA ATPase activity, SopA filament formation in the presence of DNA requires SopB both in vitro and in living cells (53). This may be because SopB shields naked DNA, preventing it from activating the ATPase of SopA (57). Thus, SopB serves both to promote and to destabilize filament formation by SopA and this dynamic process drives plasmid partition.

Type I par systems segregate plasmids by a pulling mechanism, using de-polymerization of the motor protein filament to separate plasmids between daughter cells (19). This process of segregation is reminiscent of kinetochore motion during eukaryotic mitosis. Initially, SopB pairs two plasmids together at mid-cell by binding sopC as a dimer (Fig 1a, panel ii). SopB multimerizes, coating naked plasmid DNA surrounding sopC in a process referred to as “spreading” (58, 59) (Fig 1a, panel iii). SopB in complex with non-centromeric DNA promotes polymerization of SopA (57). SopA filaments extend radially outward from the plasmids in both directions (Fig 1a, panel iv), until they encounter SopB monomers in complex with sopC (56), which stimulates the ATPase of SopA, leading to a wave of ATP hydrolysis that destabilizes the filaments (57) (Fig 1a, panel v). Disassembling SopA filaments exert tension on SopB, pulling the plasmids apart to the quarter-cell positions (53) (Fig 1a, panel vi). The opposing forces exerted by individual radial filaments may serve to center the plasmids with respect to each other and the short axis of the cell, akin to the localization the mitotic spindle due to the force exerted by microtubule de-polymerization in higher eukaryotes (60).

The dynamics of partitioning by sopABC have been observed in vivo using microscopy. Plasmids harboring a sopABC cassette initially localize at mid-cell. Upon replication, the resulting plasmids migrate symmetrically to the quarter-cell positions (61). In the absence of SopB, SopA filaments oscillate between cell poles in vivo, displaying dynamics analogous to the localization of the septation-determinant MinD (62); it is thought that this oscillation contributes to the pulling force that drives plasmid motion (63).

SopA filaments may be tethered at one end to some yet uncharacterized cellular structure. Initially it was thought that the nucleoid could serve as an anchor to ensure segregation by sopABC, however faithful segregation of F plasmids into anucleate cells argues against this possibility (52). It is possible that the cell membrane or a cytoskeletal protein is responsible for this tethering (64). Other studies have proposed that the mechanism of segregation by SopA does not depend on filament formation or polymerization, but rather on a gradient of SopA-ATP monomers distributed throughout the cytosol (65). In this model, SopA monomers close to the nucleoid are in the ADP-bound state, and SopA monomers distal from the nucleoid are ATP-bound leading to a gradient. SopB has a much higher affinity for the ATP- than the ADP-bound state of SopA, and SopB stimulates the ATPase activity of SopA (57). SopB may sequentially bind SopA monomers, dissociate upon ATP hydrolysis, and subsequently bind the next monomer, pulling plasmids apart by a diffusion-ratchet rather than by a depolymerizing filament (65). In vitro studies have demonstrated SopA-mediated pulling of SopB on a DNA via this diffusion-ratchet, indicating that filaments and a tether may not be required for pulling cargo (66). However, it is unclear whether these conditions are applicable to cellular physiology. Additionally, microscopic studies indicate that SopA does indeed form filamentous structures in living cells (62, 63). The mechanics of segregation, including whether a host-cell derived anchor is required, the regulation of the organization of SopA filaments, and how SopB stimulates the ATPase activity of SopA in type I par systems remain ongoing topics of study.

Type II par systems: The R1-plasmid parRMC locus

The type II par system encoded by the E. coli multi-drug antibiotic resistance plasmid R1 was discovered in 1986 (47). This represents the archetypal member of this family of partitioning systems.

The type II par system of R1 possesses two protein-coding genes: parR, which encodes the adaptor protein (67), and parM, which encodes the actin-like ATPase (68) (Fig. 1b). The centromeric element, parC, is a 160 base pair sequence found upstream of the open reading frames for ParRM. This region consists of two tandem arrays of five direct-repeats, flanking the promoter for the parRM genes (41). ParR preferentially binds parC sequences in supercoiled DNA, and its binding induces significant bending of the DNA (69). All three components are necessary for symmetrical distribution of plasmids between daughter cells (38)

The actin-like motor protein, ParM, forms polar, left-handed double-stranded filaments in vivo (70) and in vitro (71). ParM cooperatively forms filaments in the ATP-bound state. Oligomerization promotes the ATPase activity of ParM. ParM monomers are added to the ends of filaments in the ATP-bound state, and lost from the ends upon hydrolysis. Although the organization of ParM monomers within a filament is unidirectional, assembly and disassembly occurs at equal rates from either end (72). In the absence of ParR, ParM forms transient, short filaments (73). ParM filaments are stabilized by the presence of an ATP-bound ParM monomer at either end, however the rapid kinetics of the ATPase activity leads to frequent catastrophic disassembly (74). Association with ParR in complex with parC stabilizes the ends of ParM filaments (72). ParM monomers are added to the ends of ParR-bound filaments, leading to bi-directional elongation (72). The bi-directional elongation of ParM filaments drives plasmids to opposite poles of the cell during segregation. Thus, unlike type I par systems, type II par systems use polymerization of the motor protein to push plasmids apart.

The dynamics of type II par segregation has been observed in vivo using R1 plasmids carrying tandem lac operator arrays in combination with fluorescent fusions to the LacI repressor protein (73). Single R1 plasmids initially diffuse freely within accessible areas of the cytoplasm (Fig. 1b panel i). When two plasmids encounter each other in the cell, they become tethered and move as a single unit (Fig. 1b panel ii). Filament formation by ParM leads to rapid separation along the long axis of the cell over the course of 10-30 seconds (Fig. 1b panels iii, iv, v). ATP hydrolysis triggers ParM filament disassembly (Fig. 1b panel vi). After separation, plasmids again diffuse freely until they encounter each other and pair again (Fig. 1b panels vii, i, and ii). This pairing and separation occurs repeatedly, both pre- and post- cell division. The temporal dynamics of repeated pairing and separation of plasmids is recapitulated in vitro (75). Because the time scale of plasmid separation by ParM filaments is much shorter than that of cell division, repeated pushing of plasmids to opposite cell poles maximizes the likelihood that each daughter cell will inherit a copy of the plasmid.

The random distribution hypothesis of plasmid segregation for high-copy number plasmids

Hcn plasmids typically lack genes encoding canonical active partition systems. These plasmids are associated with an elevated metabolic burden both because of elevated gene expression and because of the cost associated with replicating to a high copy number. Therefore (in the absence of positive selection for plasmid-borne genes, or of negative selection against plasmid loss) plasmid-free daughters that stochastically arise following cell division would be expected to have a significant fitness advantage, threatening plasmid maintenance in the population (8).

Hcn plasmids, however, show considerable stability in the absence of positive selection (8), which has been attributed to infrequent generation of plasmid-free cells. This interpretation, known as the random distribution model, assumes free diffusion of plasmids throughout the cytoplasm before cell division and random segregation during cell division.

If plasmids segregate randomly between cells, the probability of a plasmid-free daughter cell arising (ρo) upon each round of cell division is given by ρo=2(1-n), where n=plasmid copy number (25). Based on this equation, the theoretical frequency loss of a plasmid is given by Lth= (1/2)n (22). Because hcn plasmids have a large n, the estimated ρo for these plasmids is low. For example, if a hypothetical plasmid is carried at greater than 15 copies per cell, the predicted loss frequency per round of cell division is less than 0.003%. Thus, in the absence of selection, fewer than 0.3% of cells would be predicted to have lost this plasmid after 100 generations in culture, suggesting that hcn plasmids can be retained long-term absent selection or active partitioning.

Evidence against random distribution model

The calculations above assume a normal distribution of plasmid copy number in the population. For a given average copy number the estimated fraction of plasmid-free cells per generation varies substantially depending on the standard deviation. This explains the paradoxical finding that mutations increasing plasmid copy number through deregulation of control of plasmid copy number often lead to increased plasmid instability (76). A second assumption is absence of negative selection against plasmid-carrying cells. As explained above, this is an unrealistic scenario given the metabolic burden represented by gene expression and plasmid replication, and the result is that rare, plasmid-less cells are expected to have a substantial fitness advantage that would eventually lead to plasmid loss in the population. In addition to these two conceptual considerations, more recently two experimental lines of evidence further question the random distribution model:

Non-random distribution of plasmids within the cell: One key assumption behind the random distribution model for hcn plasmid segregation is that plasmid molecules diffuse freely throughout the cell. However, microscopic studies using fluorescently labeled plasmids show that ColE1 plasmids are excluded from the nucleoid region (77-79), localizing preferentially at cell poles (79). In vivo microscopy studies showed that during replication, fluorescent foci corresponding to the studied plasmid (a pUC19-derivative) appeared to split and subsequently localize to the quarter-cell positions prior to septation and division (78). This was confirmed in a second study, which showed that a ColE1 plasmid localized both at the pole and mid-cell, with the mid-cell position of the mother cell becoming the cell pole in one of the daughters (80). Overall, these observations evidence that plasmid diffusion within living cells is strongly constrained.

Effective reduction in plasmid copy number though clustering: in addition to limiting the cellular volume available for diffusion, the specific subcellular localization of plasmids also reduces the effective number of units available for segregation (81). Indeed, the studies mentioned above found hcn plasmids co-localizing as clusters (78, 80). According to the prediction of the random distribution model, where the probability of plasmid-free daughters arising is ρo=2(1n), clustering and multimerization has a strong effect on ρo for high-copy plasmids. For ColE1, which is maintained at roughly 15 copies per cell, dimerization increases the probability of plasmid loss each division by 256 fold. Plasmid clustering within cells was recognized earlier as a challenge to the random distribution model, and an attempt was made to reconcile the two (81). Deletion of site-specific recombination systems that resolve hcn plasmid multimers and catenanes (17) lead to decreased stability (82), demonstrating the impact on plasmid stability of decreasing the number of plasmid units available for segregation at cell division.

Alternative hypothesis

The repeated observation that hcn plasmids localize to the cell poles (78, 80) and that they accumulate and replicate at cell poles or the mid-cell position (78-80) is consistent with a process of regulated distribution aimed at ensuring vertical transmission of these plasmids during cell division.

The preferential localization to cell poles has alternatively been attributed to displacement of the plasmid by the nucleoid (79), which also appears to be the default pathway for plasmids with active partition systems (83-86). Indeed, the rearrangements in subcellular localization for hcn plasmids described above parallel the observed reorganization of the nucleoid prior to cell division and septation (79).

Despite the growing evidence pointing to a role of nucleoid exclusion in hcn plasmid segregation, the observation of discrete, multifocal clusters (78, 80) is more consistent with an actively regulated process. Here we posit the existence of a segregation mechanism for hcn plasmids, although we can only speculate on the nature of this mechanism. This mechanism would depend on proteins encoded in the chromosome. Two key differences with the nucleoid exclusion model are that hcn plasmid segregation could be subject to regulation and also that it would involve recognition of plasmid sequence by the segregation machinery. Modifications in plasmid ori sequence introduced in recombinant gene expression vectors or alterations in the host cell induced by recombinant gene expression could contribute to plasmid instability by directly interfering with segregation, generating more plasmid-free cells per generation than expected based on average plasmid copy number.

Following replication, the chromosomal origin of replication migrates bi-directionally towards either pole (87, 88) and then migrates to the replication factory at mid-cell (89). These chromosomal origin of replication migrations are reminiscent of relocations associated with plasmid segregation and could represent direct or indirect physical interactions between chromosomal and plasmid replication. However, it is hard to envision how the two processes would be coordinated in time, as the kinetics of the two processes are very different, with plasmid replication being much faster (10-20 s compared to 30-40 min for chromosomal replication). The observation that plasmid replication initiation occurs randomly in vivo (90, 91) and the absence of co-localization between chromosomal and plasmid replication in time-lapse microscopy experiments (79) further argue against a link between chromosomal replication and plasmid partition.

Known plasmid-partitioning systems rely on a sequence motif to anchor the motor protein responsible for partition to the plasmid. Such a motif may also be present, in cryptic form, in hcn plasmids. Given that most recombinant expression vectors contain only the minimal sequence for plasmid replication initiation, yet still show evidence for segregation (notably clustering) this motif would likely be found within this minimal sequence. Additional signals for partitioning existing in the native plasmids may have been deleted in vectors designed for recombinant gene expression, much like the loss of cer, which affects the ability of these plasmids to resolve concatemers (82).

In sum, although it is formally possible that segregation of high-copy plasmids is entirely driven by a combination of random diffusion and nucleoid exclusion, clustering and dynamics of plasmid loss associated with recombinant gene expression point to the existence of a regulated process of segregation for hcn plasmids. While these plasmids do not bear canonical active partitioning systems, segregation could depend on chromosomally-encoded proteins. Unlike the type-I and type-II partitioning systems described above, segregation in hcn plasmids could be tied to some other process associated with cell division. Alternatively, hcn plasmid could have coopted chromosomal partition mechanisms to ensure proper spatial regulation and segregation, just as DNA-containing organelles have (51), although no recognizable centromeric motifs have been reported in hcn plasmid origins of replication .

The possibility that hcn plasmid segregation is a regulated process should therefore be investigated further. Specifically, looking for cellular factors that physically interact with hcn plasmids could offer clues to the mechanisms contributing to hcn plasmid stability. Also, the plasmid origin of replication should be revisited not only as the site orchestrating initiation of plasmid replication but also as a possible site for recruitment of factors involved in controlling plasmid distribution in the cell. However, the multifunctional nature of the plasmid origin of replication and the role of secondary structures (which include three stem loops mediating stable complex formation between antisense and primer RNA, three stems mediating action at a distance of the antisense RNA, and two hairpins toward the 3′ end of ori sequence associated with R-loop formation and recruitment of RNAseH, (reviewed in (92)) would complicate these studies .

Understanding plasmid segregation in hcn plasmids as a regulated process could open the door to new approaches for enhancing the stability of vectors used for recombinant gene expression. Plasmid loss has been recognized as a limiting factor for large-scale recombinant gene expression and for bioremediation because the use of antibiotics to ensure plasmid retention is not practical in these settings (13, 14). Available approaches for increasing plasmid stability depend on a particular strain or culture condition (plasmid addiction systems) (93, 94), or on inducing growth arrest through massive metabolic burden (95, 96), or through induction of a quiescent state (97). Approaches aimed at increasing plasmid stability based on modifying the plasmid origin of replication are particularly appealing because they would be largely autonomous, i.e. would be largely independent on a particular strains or culture conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by The National Institute of Health K08 award [CA116429-04] to M.C

References

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK, Jr, Bradley J, Guidos RJ, Jones RN, et al. 10 × ′20 Progress--development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(12):1685–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit152. Epub 2013/04/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heuer H, Smalla K. Plasmids foster diversification and adaptation of bacterial populations in soil. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2012;36(6):1083–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00337.x. Epub 2012/03/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leplae R, Lima-Mendez G, Toussaint A. A first global analysis of plasmid encoded proteins in the ACLAME database. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2006;30(6):980–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00044.x. Epub 2006/10/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison PW, Lower RP, Kim NK, Young JP. Introducing the bacterial ‘chromid’: not a chromosome, not a plasmid. Trends in microbiology. 2010;18(4):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.010. Epub 2010/01/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas CM, Nielsen KM. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2005;3(9):711–21. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1234. Epub 2005/09/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordstrom K. Plasmid R1--replication and its control. Plasmid. 2006;55(1):1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.07.002. Epub 2005/10/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19(3):259–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. Epub 1982/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva F, Queiroz JA, Domingues FC. Evaluating metabolic stress and plasmid stability in plasmid DNA production by Escherichia coli. Biotechnology advances. 2012;30(3):691–708. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.12.005. Epub 2012/01/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz Ricci JC, Hernandez ME. Plasmid effects on Escherichia coli metabolism. Critical reviews in biotechnology. 2000;20(2):79–108. doi: 10.1080/07388550008984167. Epub 2000/07/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friehs K. Plasmid copy number and plasmid stability. Advances in biochemical engineering/biotechnology. 2004;86:47–82. doi: 10.1007/b12440. Epub 2004/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popov M, Petrov S, Nacheva G, Ivanov I, Reichl U. Effects of a recombinant gene expression on ColE1-like plasmid segregation in Escherichia coli. BMC biotechnology. 2011;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-18. Epub 2011/03/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabherr R, Nilsson E, Striedner G, Bayer K. Stabilizing plasmid copy number to improve recombinant protein production. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2002;77(2):142–7. doi: 10.1002/bit.10104. Epub 2001/12/26. pii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corchero JL, Villaverde A. Plasmid maintenance in Escherichia coli recombinant cultures is dramatically, steadily, and specifically influenced by features of the encoded proteins. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 1998;58(6):625–32. Epub 1999/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabherr R, Bayer K. Impact of targeted vector design on Co/E1 plasmid replication. Trends in biotechnology. 2002;20(6):257–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01950-9. Epub 2002/05/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summers DK, Beton CW, Withers HL. Multicopy plasmid instability: the dimer catastrophe hypothesis. Molecular microbiology. 1993;8(6):1031–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01648.x. Epub 1993/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salje J. Plasmid segregation: how to survive as an extra piece of DNA. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;45(4):296–317. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.494657. Epub 2010/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas CM. Paradigms of plasmid organization. Molecular microbiology. 2000;37(3):485–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02006.x. Epub 2000/08/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebersbach G, Gerdes K. Bacterial mitosis: partitioning protein ParA oscillates in spiral-shaped structures and positions plasmids at mid-cell. Molecular microbiology. 2004;52(2):385–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04002.x. Epub 2004/04/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerdes K, Howard M, Szardenings F. Pushing and pulling in prokaryotic DNA segregation. Cell. 2010;141(6):927–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.033. Epub 2010/06/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe E, Wachi M, Yamasaki M, Nagai K. ATPase activity of SopA, a protein essential for active partitioning of F plasmid. Molecular & general genetics : MGG. 1992;234(3):346–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00538693. Epub 1992/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dmowski M, Jagura-Burdzy G. Active stable maintenance functions in low copy-number plasmids of Gram-positive bacteria I. Partition systems. Polish journal of microbiology / Polskie Towarzystwo Mikrobiologow = The Polish Society of Microbiologists. 2013;62(1):3–16. Epub 2013/07/09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordstrom K, Austin SJ. Mechanisms that contribute to the stable segregation of plasmids. Annual review of genetics. 1989;23:37–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.000345. Epub 1989/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summers DK. The kinetics of plasmid loss. Trends in biotechnology. 1991;9(8):273–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(91)90089-z. Epub 1991/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin S, Ziese M, Sternberg N. A novel role for site-specific recombination in maintenance of bacterial replicons. Cell. 1981;25(3):729–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90180-x. Epub 1981/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summers D. Timing, self-control and a sense of direction are the secrets of multicopy plasmid stability. Molecular microbiology. 1998;29(5):1137–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01012.x. Epub 1998/10/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes CS, Sauer RT. Toxin-antitoxin pairs in bacteria: killers or stress regulators? Cell. 2003;112(1):2–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01282-5. Epub 2003/01/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stieber D, Gabant P, Szpirer C. The art of selective killing: plasmid toxin/antitoxin systems and their technological applications. BioTechniques. 2008;45(3):344–6. doi: 10.2144/000112955. Epub 2008/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiraga S, Jaffe A, Ogura T, Mori H, Takahashi H. F plasmid ccd mechanism in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 1986;166(1):100–4. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.100-104.1986. Epub 1986/04/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard P, Kezdy KE, Van Melderen L, Steyaert J, Wyns L, Pato ML, et al. The F plasmid CcdB protein induces efficient ATP-dependent DNA cleavage by gyrase. Journal of molecular biology. 1993;234(3):534–41. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1609. Epub 1993/12/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Melderen L, Bernard P, Couturier M. Lon-dependent proteolysis of CcdA is the key control for activation of CcdB in plasmid-free segregant bacteria. Molecular microbiology. 1994;11(6):1151–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00391.x. Epub 1994/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cascales E, Buchanan SK, Duche D, Kleanthous C, Lloubes R, Postle K, et al. Colicin biology. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR. 2007;71(1):158–229. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-06. Epub 2007/03/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sia EA, Roberts RC, Easter C, Helinski DR, Figurski DH. Different relative importances of the par operons and the effect of conjugal transfer on the maintenance of intact promiscuous plasmid RK2. Journal of bacteriology. 1995;177(10):2789–97. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2789-2797.1995. Epub 1995/05/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouet JY, Nordstrom K, Lane D. Plasmid partition and incompatibility--the focus shifts. Molecular microbiology. 2007;65(6):1405–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05882.x. Epub 2007/08/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinto UM, Pappas KM, Winans SC. The ABCs of plasmid replication and segregation. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(11):755–65. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2882. Epub 2012/10/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen RB, Dam M, Gerdes K. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The parA operon is autoregulated by ParR and its transcription is highly stimulated by a downstream activating element. Journal of molecular biology. 1994;236(5):1299–309. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90059-0. Epub 1994/03/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodionov O, Lobocka M, Yarmolinsky M. Silencing of genes flanking the P1 plasmid centromere. Science. 1999;283(5401):546–9. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.546. Epub 1999/01/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kusukawa N, Mori H, Kondo A, Hiraga S. Partitioning of the F plasmid: overproduction of an essential protein for partition inhibits plasmid maintenance. Molecular & general genetics : MGG. 1987;208(3):365–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00328125. Epub 1987/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen RB, Gerdes K. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: ParM partitioning protein of plasmid R1 co-localizes with its replicon during the cell cycle. The EMBO journal. 1999;18(14):4076–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4076. Epub 1999/07/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadoya R, Chattoraj DK. Insensitivity of chromosome I and the cell cycle to blockage of replication and segregation of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II. mBio. 2012;3(3) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00067-12. Epub 2012/05/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biek DP, Strings J. Partition functions of mini-F affect plasmid DNA topology in Escherichia coli. Journal of molecular biology. 1995;246(3):388–400. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0094. Epub 1995/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dam M, Gerdes K. Partitioning of plasmid R1. Ten direct repeats flanking the parA promoter constitute a centromere-like partition site parC, that expresses incompatibility. Journal of molecular biology. 1994;236(5):1289–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90058-2. Epub 1994/03/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes F, Davis MA, Austin SJ. Fine-structure analysis of the P7 plasmid partition site. Journal of bacteriology. 1993;175(11):3443–51. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3443-3451.1993. Epub 1993/06/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoischen C, Bolshoy A, Gerdes K, Diekmann S. Centromere parC of plasmid R1 is curved. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32(19):5907–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh920. Epub 2004/11/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bechert T, Heck S, Fleig U, Diekmann S, Hegemann JH. All 16 centromere DNAs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae show DNA curvature. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27(6):1444–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1444. Epub 1999/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozyamak E, Kollman JM, Komeili A. Bacterial actins and their diversity. Biochemistry. 2013;52(40):6928–39. doi: 10.1021/bi4010792. Epub 2013/09/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ah-Seng Y, Rech J, Lane D, Bouet JY. Defining the role of ATP hydrolysis in mitotic segregation of bacterial plasmids. PLoS genetics. 2013;9(12):e1003956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003956. Epub 2013/12/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerdes K, Molin S. Partitioning of plasmid R1. Structural and functional analysis of the parA locus. Journal of molecular biology. 1986;190(3):269–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90001-x. Epub 1986/08/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin DC, Levin PA, Grossman AD. Bipolar localization of a chromosome partition protein in Bacillus subtilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(9):4721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4721. Epub 1997/04/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohl DA, Gober JW. Cell cycle-dependent polar localization of chromosome partitioning proteins in Caulobacter crescentus. Cell. 1997;88(5):675–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81910-8. Epub 1997/03/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livny J, Yamaichi Y, Waldor MK. Distribution of centromere-like parS sites in bacteria: insights from comparative genomics. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189(23):8693–703. doi: 10.1128/JB.01239-07. Epub 2007/10/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salje J, Gayathri P, Lowe J. The ParMRC system: molecular mechanisms of plasmid segregation by actin-like filaments. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2010;8(10):683–92. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2425. Epub 2010/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ezaki B, Ogura T, Niki H, Hiraga S. Partitioning of a mini-F plasmid into anucleate cells of the mukB null mutant. Journal of bacteriology. 1991;173(20):6643–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6643-6646.1991. Epub 1991/10/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lim GE, Derman AI, Pogliano J. Bacterial DNA segregation by dynamic SopA polymers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(49):17658–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507222102. Epub 2005/11/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Libante V, Thion L, Lane D. Role of the ATP-binding site of SopA protein in partition of the F plasmid. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;314(3):387–99. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5158. Epub 2002/02/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barilla D, Rosenberg MF, Nobbmann U, Hayes F. Bacterial DNA segregation dynamics mediated by the polymerizing protein ParF. The EMBO journal. 2005;24(7):1453–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600619. Epub 2005/03/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ah-Seng Y, Lopez F, Pasta F, Lane D, Bouet JY. Dual role of DNA in regulating ATP hydrolysis by the SopA partition protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284(44):30067–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044800. Epub 2009/09/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bouet JY, Ah-Seng Y, Benmeradi N, Lane D. Polymerization of SopA partition ATPase: regulation by DNA binding and SopB. Molecular microbiology. 2007;63(2):468–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05537.x. Epub 2006/12/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pillet F, Sanchez A, Lane D, Anton Leberre V, Bouet JY. Centromere binding specificity in assembly of the F plasmid partition complex. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(17):7477–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr457. Epub 2011/06/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodionov O, Yarmolinsky M. Plasmid partitioning and the spreading of P1 partition protein ParB. Molecular microbiology. 2004;52(4):1215–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04055.x. Epub 2004/05/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grill SW, Hyman AA. Spindle positioning by cortical pulling forces. Developmental cell. 2005;8(4):461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.014. Epub 2005/04/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niki H, Hiraga S. Subcellular distribution of actively partitioning F plasmid during the cell division cycle in E. coli. Cell. 1997;90(5):951–7. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80359-1. Epub 1997/09/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gitai Z. Diversification and specialization of the bacterial cytoskeleton. Current opinion in cell biology. 2007;19(1):5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.12.010. Epub 2006/12/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatano T, Yamaichi Y, Niki H. Oscillating focus of SopA associated with filamentous structure guides partitioning of F plasmid. Molecular microbiology. 2007;64(5):1198–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05728.x. Epub 2007/06/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Firshein W, Kim P. Plasmid replication and partition in Escherichia coli: is the cell membrane the key? Molecular microbiology. 1997;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2061569.x. Epub 1997/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vecchiarelli AG, Han YW, Tan X, Mizuuchi M, Ghirlando R, Biertumpfel C, et al. ATP control of dynamic P1 ParA-DNA interactions: a key role for the nucleoid in plasmid partition. Molecular microbiology. 2010;78(1):78–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07314.x. Epub 2010/07/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vecchiarelli AG, Hwang LC, Mizuuchi K. Cell-free study of F plasmid partition provides evidence for cargo transport by a diffusion-ratchet mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(15):E1390–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302745110. Epub 2013/03/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jensen RB, Lurz R, Gerdes K. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: replicon pairing by parC of plasmid R1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(15):8550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8550. Epub 1998/07/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jensen RB, Gerdes K. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The ParM protein exhibits ATPase activity and interacts with the centromere-like ParR-parC complex. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;269(4):505–13. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1061. Epub 1997/06/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoischen C, Bussiek M, Langowski J, Diekmann S. Escherichia coli low-copy-number plasmid R1 centromere parC forms a U-shaped complex with its binding protein ParR. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36(2):607–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm672. Epub 2007/12/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gayathri P, Fujii T, Moller-Jensen J, van den Ent F, Namba K, Lowe J. A bipolar spindle of antiparallel ParM filaments drives bacterial plasmid segregation. Science. 2012;338(6112):1334–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1229091. Epub 2012/11/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gayathri P, Fujii T, Namba K, Lowe J. Structure of the ParM filament at 8.5A resolution. Journal of structural biology. 2013;184(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.02.010. Epub 2013/03/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moller-Jensen J, Borch J, Dam M, Jensen RB, Roepstorff P, Gerdes K. Bacterial mitosis: ParM of plasmid R1 moves plasmid DNA by an actin-like insertional polymerization mechanism. Molecular cell. 2003;12(6):1477–87. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00451-9. Epub 2003/12/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell CS, Mullins RD. In vivo visualization of type II plasmid segregation: bacterial actin filaments pushing plasmids. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;179(5):1059–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708206. Epub 2007/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Popp D, Xu W, Narita A, Brzoska AJ, Skurray RA, Firth N, et al. Structure and filament dynamics of the pSK41 actin-like ParM protein: implications for plasmid DNA segregation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(13):10130–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071613. Epub 2010/01/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garner EC, Campbell CS, Weibel DB, Mullins RD. Reconstitution of DNA segregation driven by assembly of a prokaryotic actin homolog. Science. 2007;315(5816):1270–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1138527. Epub 2007/03/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tomizawa J, Som T. Control of ColE1 plasmid replication: enhancement of binding of RNA I to the primer transcript by the Rom protein. Cell. 1984;38(3):871–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90282-4. Epub 1984/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lau BT, Malkus P, Paulsson J. New quantitative methods for measuring plasmid loss rates reveal unexpected stability. Plasmid. 2013;70(3):353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.07.007. Epub 2013/09/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pogliano J, Ho TQ, Zhong Z, Helinski DR. Multicopy plasmids are clustered and localized in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(8):4486–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075798. Epub 2001/03/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reyes-Lamothe R, Tran T, Meas D, Lee L, Li AM, Sherratt DJ, et al. High-copy bacterial plasmids diffuse in the nucleoid-free space, replicate stochastically and are randomly partitioned at cell division. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(2):1042–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt918. Epub 2013/10/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yao S, Helinski DR, Toukdarian A. Localization of the naturally occurring plasmid ColE1 at the cell pole. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189(5):1946–53. doi: 10.1128/JB.01451-06. Epub 2006/12/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nordstrom K, Gerdes K. Clustering versus random segregation of plasmids lacking a partitioning function: a plasmid paradox? Plasmid. 2003;50(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0147-619x(03)00056-8. Epub 2003/08/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Summers DK, Sherratt DJ. Multimerization of high copy number plasmids causes instability: CoIE1 encodes a determinant essential for plasmid monomerization and stability. Cell. 1984;36(4):1097–103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90060-6. Epub 1984/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bignell CR, Haines AS, Khare D, Thomas CM. Effect of growth rate and incC mutation on symmetric plasmid distribution by the IncP-1 partitioning apparatus. Molecular microbiology. 1999;34(2):205–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01565.x. Epub 1999/11/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Erdmann N, Petroff T, Funnell BE. Intracellular localization of P1 ParB protein depends on ParA and parS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(26):14905–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14905. Epub 1999/12/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Niki H, Hiraga S. Subcellular localization of plasmids containing the oriC region of the Escherichia coli chromosome, with or without the sopABC partitioning system. Molecular microbiology. 1999;34(3):498–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01611.x. Epub 1999/11/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weitao T, Dasgupta S, Nordstrom K. Role of the mukB gene in chromosome and plasmid partition in Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology. 2000;38(2):392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02138.x. Epub 2000/11/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Possoz C, Junier I, Espeli O. Bacterial chromosome segregation. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:1020–34. doi: 10.2741/3971. Epub 2011/12/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sawitzke J, Austin S. An analysis of the factory model for chromosome replication and segregation in bacteria. Molecular microbiology. 2001;40(4):786–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02350.x. Epub 2001/06/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reyes-Lamothe R, Nicolas E, Sherratt DJ. Chromosome replication and segregation in bacteria. Annual review of genetics. 2012;46:121–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155421. Epub 2012/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bazaral M, Helinski DR. Replication of a bacterial plasmid and an episome in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1970;9(2):399–406. doi: 10.1021/bi00804a029. Epub 1970/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rownd R. Replication of a bacterial episome under relaxed control. Journal of molecular biology. 1969;44(3):387–402. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90368-4. Epub 1969/09/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Camps M. Modulation of ColE1-like plasmid replication for recombinant gene expression. Recent patents on DNA & gene sequences. 2010;4(1):58–73. doi: 10.2174/187221510790410822. Epub 2010/03/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kroll J, Klinter S, Schneider C, Voss I, Steinbuchel A. Plasmid addiction systems: perspectives and applications in biotechnology. Microbial biotechnology. 2010;3(6):634–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00170.x. Epub 2011/01/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goh S, Good L. Plasmid selection in Escherichia coli using an endogenous essential gene marker. BMC biotechnology. 2008;8:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-61. Epub 2008/08/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sorensen HP, Mortensen KK. Advanced genetic strategies for recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of biotechnology. 2005;115(2):113–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.08.004. Epub 2004/12/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Togna AP, Shuler ML, Wilson DB. Effects of plasmid copy number and runaway plasmid replication on overproduction and excretion of beta-lactamase from Escherichia coli. Biotechnology progress. 1993;9(1):31–9. doi: 10.1021/bp00019a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mukherjee KJ, Rowe DC, Watkins NA, Summers DK. Studies of single-chain antibody expression in quiescent Escherichia coli. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2004;70(5):3005–12. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3005-3012.2004. Epub 2004/05/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]