ABSTRACT

Focal adhesions are macromolecular complexes that connect the actin cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix. Dynamic turnover of focal adhesions is crucial for cell migration. Paxillin is a multi-adaptor protein that plays an important role in regulating focal adhesion dynamics. Here, we identify TRIM15, a member of the tripartite motif protein family, as a paxillin-interacting factor and a component of focal adhesions. TRIM15 localizes to focal contacts in a myosin-II-independent manner by an interaction between its coiled-coil domain and the LD2 motif of paxillin. Unlike other focal adhesion proteins, TRIM15 is a stable focal adhesion component with restricted mobility due to its ability to form oligomers. TRIM15-depleted cells display impaired cell migration and reduced focal adhesion disassembly rates, in addition to enlarged focal adhesions. Thus, our studies demonstrate a cellular function for TRIM15 as a regulatory component of focal adhesion turnover and cell migration.

KEY WORDS: Cell migration, Focal adhesions, Focal adhesion disassembly, Paxillin, TRIM E3 ligases, TRIM15

INTRODUCTION

TRIM15 is a member of the tripartite motif (TRIM)/RBCC protein family, which consists of ∼100 proteins (Han et al., 2011). The N-terminus of TRIM15 displays a modular structure shared by most TRIM family members and consists of a RING domain followed by a B-box type 2 zinc finger domain and a predicted coiled-coil region (McNab et al., 2011; Reymond et al., 2001). The C-terminus of TRIM15 protein contains a PRY and an SPRY/B30.2 domain. The presence of a RING domain suggests that it can function as an E3 ligase. The B-box and coiled-coil domains are believed to participate in protein–protein interactions and the formation of oligomers that are crucial for the biological activities of TRIM proteins (Borden et al., 1996; Diaz-Griffero et al., 2009; Ganser-Pornillos et al., 2011; Uchil et al., 2013). The PRY and SPRY/B30.2 domains can function as immune defense components and in pathogen sensing (Pertel et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2005; Stremlau et al., 2005; Uchil et al., 2013). Like many other TRIM proteins, TRIM15 forms cytoplasmic bodies upon ectopic expression (Stremlau et al., 2004; Uchil et al., 2008). TRIM15 has been shown to regulate inflammatory and innate immune signaling, in addition to displaying antiviral activities (Uchil et al., 2013; Uchil et al., 2008). Cellular interactors of TRIM15 that could potentially provide further understanding of its physiological function are unknown.

Here, we identify TRIM15 as a component of focal adhesions, and we show that the multi-adaptor protein paxillin is the main interacting protein that recruits TRIM15 to these adhesions. Focal adhesions are large multi-protein complexes that allow cells to adhere by connecting the intracellular cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix through transmembrane integrin adhesion receptors (Abercrombie et al., 1971; Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996; Geiger et al., 2009; Hynes and Destree, 1978). Proteomic analyses have identified hundreds of proteins that are recruited to focal adhesions (Humphries et al., 2009; Kuo et al., 2011; Schiller et al., 2011; Zaidel-Bar et al., 2007), which form when integrins bind to extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin. The resulting clusters of ligand-bound integrins then recruit the cytoskeletal protein talin and the adaptor protein paxillin to form the initial focal contacts (Laukaitis et al., 2001; Pasapera et al., 2010; Turner et al., 1990; Webb et al., 2004). Maturation of focal contacts into focal adhesions depends on the stiffness of the extracellular matrix and on myosin-II-induced cytoskeletal tension that leads to the recruitment of vinculin, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), zyxin, actin-binding proteins and actin-nucleating proteins that allow the formation of stress fibers (del Rio et al., 2009; Pasapera et al., 2010; Vogel and Sheetz, 2006; Zaidel-Bar et al., 2003).

Dynamic turnover of focal adhesions is necessary to promote cell migration, development and wound healing (Huttenlocher and Horwitz, 2011; Stehbens and Wittmann, 2012). The balance of adhesive and proliferative forces is essential for cell differentiation and in the prevention of cancer. Consequently, focal adhesion formation and disassembly are highly regulated processes (Nagano et al., 2012), which the multi-adaptor protein paxillin plays an important role in regulating (Deakin and Turner, 2008; Hagel et al., 2002). By contrast, FAK is specifically required for focal adhesion disassembly (Ilić et al., 1995; Schober et al., 2007), a process that has been proposed to involve proteolysis by calpain and metalloproteinases, Rho GTPases, ubiquitylation, macropinocytosis, endocytosis and an unknown relaxing factor provided by microtubules (Didier et al., 2003; Efimov et al., 2008; Ezratty et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2011; Hoshino et al., 2013; Iioka et al., 2007; Kaverina et al., 1999; Palecek et al., 1998; Worthylake et al., 2001). Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly appears to be regulated by FAK, type I phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase β (PIPKIβ), clathrin, clathrin adaptors and dynamin-mediated endocytosis (Chao et al., 2010; Chao and Kunz, 2009; Ezratty et al., 2009; Pasapera et al., 2010; Stehbens and Wittmann, 2012).

Here, we demonstrate that TRIM15 interacts with paxillin and is a component of focal adhesions. TRIM15 localizes to focal adhesions during the early stage of adhesion biogenesis owing to an interaction between its coiled-coil domain and the LD2 motif of paxillin but, unlike other focal adhesion components, it remains stably bound to the focal adhesions. Silencing of TRIM15 impairs cell migration and chemotaxis. In addition, TRIM15-depleted cells spread faster and, at steady-state, exhibit up to threefold increase in focal adhesion area and intensity. This suggests a defect in the disassembly of focal adhesions rather than in their assembly. Indeed, we observe a reduction in focal adhesion disassembly rates in TRIM15-depleted cells at steady state, as well as during microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly. Further analyses suggest that TRIM15-depleted cells display a deficiency in the endocytosis of activated β1 integrin, a crucial early step in focal adhesion disassembly process. Thus, our studies demonstrate a cellular function for TRIM15 as a regulatory component of focal adhesion turnover and cell migration.

RESULTS

TRIM15 interacts with paxillin and localizes to focal adhesions

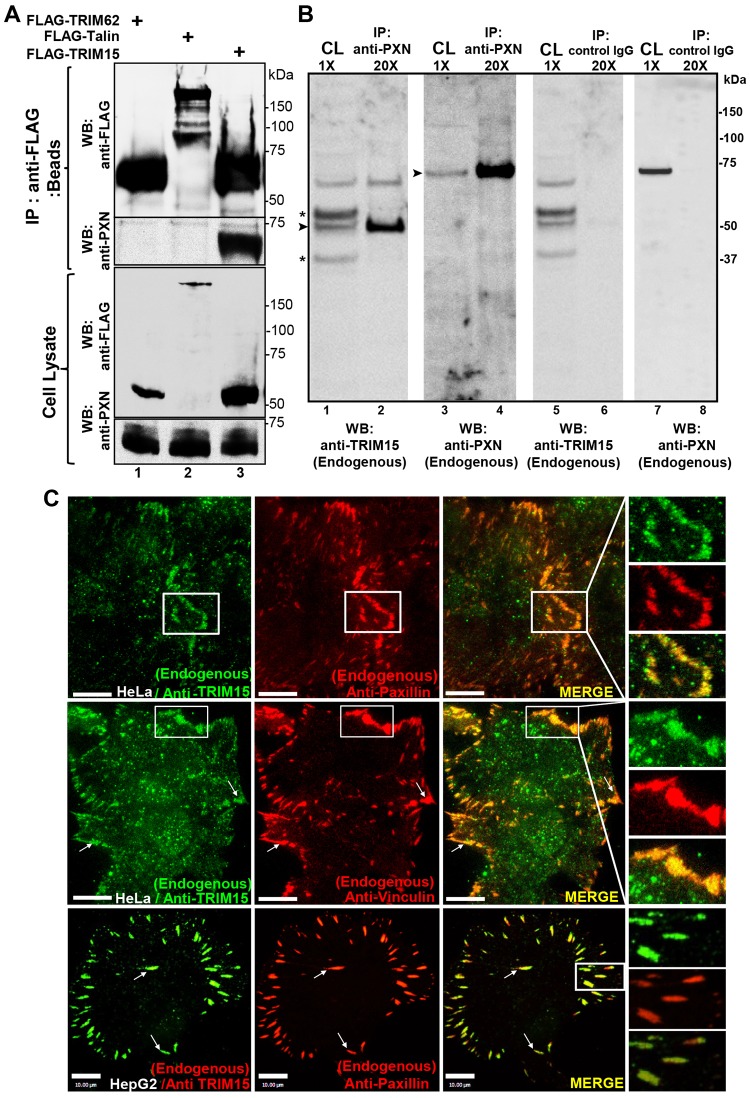

We carried out co-immunoprecipitation analyses to identify cellular factors that interact with TRIM15. Mass spectrometric analyses of immunoprecipitates from HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged TRIM15 identified four peptides that mapped to human paxillin (supplementary material Table S1). We verified the interaction between paxillin and TRIM15 by transiently expressing and immunoprecipitating FLAG-tagged TRIM15, and we observed the presence of endogenous paxillin in co-immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1A). Endogenous TRIM15 also co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous paxillin in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescent staining of HeLa and HepG2 cells revealed that the endogenous TRIM15 protein resides in focal adhesions, where it colocalizes with paxillin and the known focal adhesion component vinculin (Fig. 1C). When transiently expressed in HeLa cells, untagged or CFP-tagged TRIM15 similarly stained focal adhesions, colocalized with zyxin, paxillin and talin, and labeled the tips of actin stress fibers emanating from focal adhesions (supplementary material Fig. S1A, columns 1–4). Like many other cytoplasmic TRIM proteins, TRIM15 also formed cytoplasmic bodies when overexpressed (supplementary material Fig. S1A, arrows in the second column) (Short and Cox, 2006; Uchil et al., 2008). Human TRIM15–YFP localized to focal adhesions in all the cell types tested, which were of both mouse and human origin. In addition, mouse TRIM15 protein also localized to focal adhesions in NIH3T3 cells (supplementary material Fig. S1B). Taken together, these data establish that TRIM15 interacts with paxillin and is a component of focal adhesions.

Fig. 1.

TRIM15 interacts with paxillin and localizes to focal adhesions. (A) Western blot (WB) analyses of anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates (beads) and cell lysates using antibodies against the FLAG epitope or paxillin (PXN) from HeLa cell lysates expressing FLAG-tagged TRIM15 or control proteins TRIM62 and talin. (B) Western blot analyses of anti-paxillin (endogenous) or control IgG immunoprecipitates (IP) and cell lysates (CL) with antibodies against endogenous TRIM15 or paxillin from HepG2 cell lysates. Asterisk, non-specific background bands; arrowheads, TRIM15- or paxillin-specific band. The relative concentrations of immunoprecipitates (20×) with respect to cell lysates (1×) loaded on the gel are also indicated. (C) Individual and merged TIRFM images of the indicated cell lines showing endogenous TRIM15, paxillin and vinculin detected by immunofluorescence using respective antibodies. Arrows point to colocalized signals in individual focal adhesions. Areas outlined in white are shown at a higher magnification to the right. Scale bars: 10 µm.

Paxillin recruits TRIM15 to focal contacts in a myosin-II-independent manner

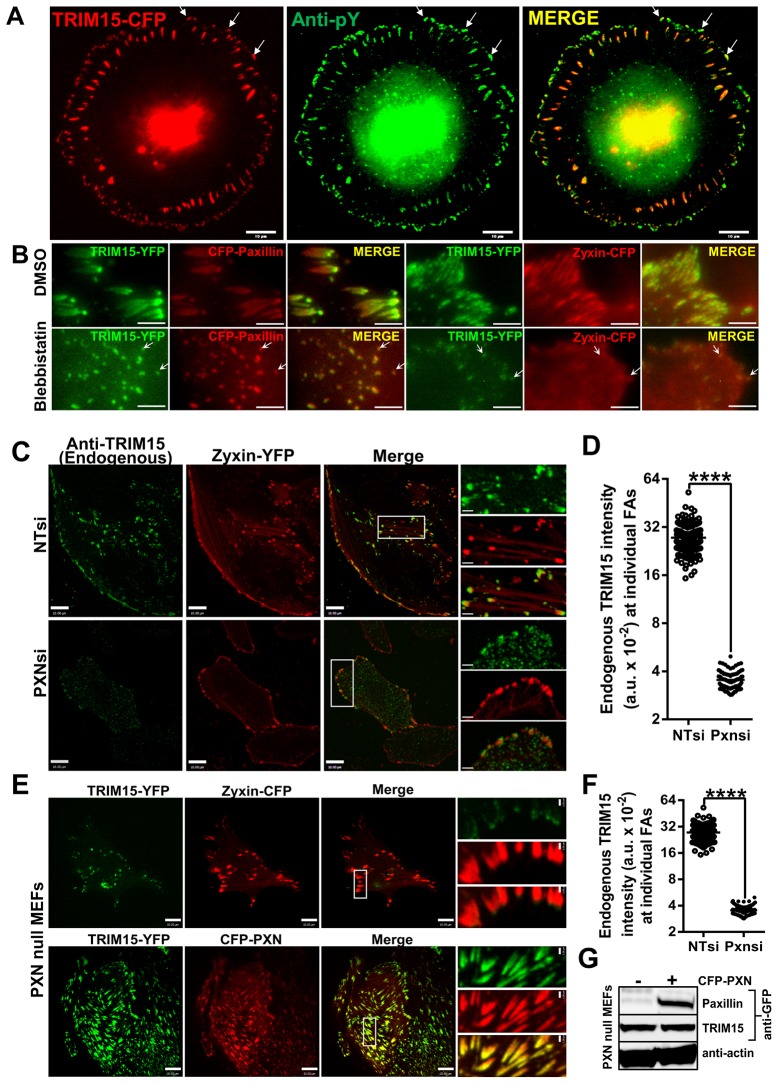

Paxillin localizes early to focal contacts prior to their maturation into focal adhesions (Pasapera et al., 2010). Given that TRIM15 interacts with paxillin, we tested whether TRIM15 similarly localizes early to focal contacts. We stained HeLa cells with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies that label both peripheral focal contacts and focal adhesions. TRIM15 indeed colocalized with phosphotyrosine-labeled peripheral focal contacts (Fig. 2A). In contrast to focal adhesions, the recruitment of proteins to early focal contacts is not dependent on myosin II activity (Pasapera et al., 2010). Treatment with blebbistatin, a myosin II inhibitor, did not interfere with the recruitment of TRIM15 to paxillin-labeled focal contacts (Fig. 2B). As described previously, blebbistatin treatment led to a loss of zyxin-positive peripheral adhesive structures (Fig. 2B). These data confirmed that TRIM15, like paxillin, localizes to focal contacts early during the biogenesis of focal adhesions in a myosin-II-independent manner.

Fig. 2.

TRIM15 recruitment to focal adhesions is myosin-II-independent and depends on paxillin. (A) HeLa cells expressing TRIM15–CFP (red) were immunostained and imaged for phosphotyrosine epitopes (anti-pY, green). Arrows, focal contacts where TRIM15–CFP and phosphotyrosine epitopes colocalize. Scale bars: 10 µm. (B) HeLa cells expressing TRIM15–YFP (green) and either paxillin–CFP or zyxin–CFP (red) were treated with DMSO (control) or 40 µM blebbistatin for 2 h. Arrows, TRIM15-containing focal contacts that are resistant to blebbistatin treatment. Scale bars: 2 µm. (C) Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells treated with control (NTsi) or paxillin-specific (PXNsi) siRNA and immunostained for endogenous TRIM15. Zyxin–YFP was used as the focal adhesion marker. Areas outlined in white are shown at a higher magnification to the right. (D) A plot comparing the intensities of endogenous TRIM15 staining in individual focal adhesions (<100) normalized to the corresponding intensities of focal adhesion marker with or without paxillin siRNA for the experiment shown in C. FAs, focal adhesions; a.u., arbitrary units. (E) Confocal microscopy images of paxillin-null MEFs coexpressing the indicated fluorescent proteins. Areas outlined in white are shown at a higher magnification to the right. Scale bars: 10 µm; insets, 2 µm (C,E). (F) A plot comparing the intensities of TRIM15–YFP at individual focal adhesions (<200) normalized to the corresponding intensities of focal adhesion marker with or without paxillin coexpression in paxillin-null MEFs for the experiment shown in E. ****P<0.0001. (G) Western blot of cell lysates probed with the indicated antibodies to demonstrate similar expression levels of TRIM15 for an experiment as shown in E.

We next tested whether paxillin was required for the focal adhesion localization of TRIM15 by either depleting paxillin expression by RNA interference (RNAi) in HeLa cells or by using paxillin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). In both cases, despite similar expression levels, TRIM15 localization to focal adhesions was severely compromised and reduced by more than sevenfold compared with control small interfering (si)RNA (NTsi)-treated HeLa cells or when paxillin was ectopically expressed in paxillin-null MEFs (Fig. 2C–G). These data indicate that paxillin, although not the only factor, is the major determinant for the focal adhesion targeting of TRIM15.

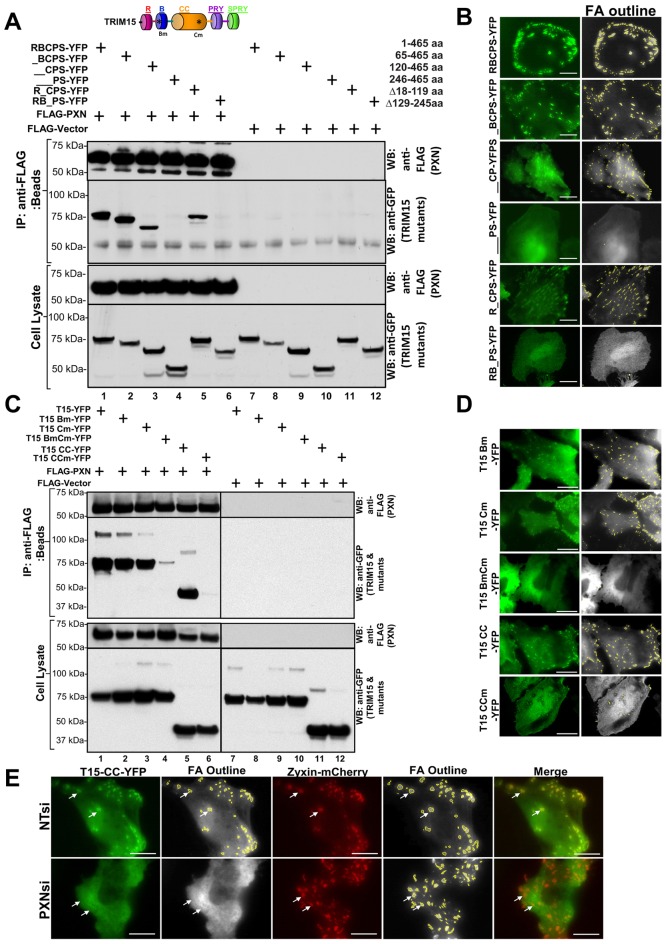

TRIM15 localizes to focal adhesions by binding to paxillin through its coiled-coil domain

We next explored the nature of the TRIM15–paxillin interaction. We expressed sequential N-terminal and individual domain deletion mutants of YFP-tagged TRIM15 in HEK293 cells and tested their ability to co-immunoprecipitate with FLAG-tagged paxillin. Deleting the TRIM15 RING domain did not affect the interaction with paxillin (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Deleting the TRIM15 B-box domain reduced but did not abrogate paxillin interaction. By contrast, removing the coiled-coil domain completely abolished the interaction with paxillin (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 6). In parallel, we performed total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) in HeLa cells to investigate whether the ability of TRIM15 variants to interact with paxillin correlated with their recruitment to focal adhesions (Fig. 3B; supplementary material Fig. S1D). TRIM15 variants lacking the B-box domain localized to focal adhesions despite being more cytoplasmic than the wild-type protein (Fig. 3B). However, TRIM15–YFP deletions that lacked the coiled-coil domain did not localize to focal adhesions. Thus, the strong correlation between the ability of TRIM15 to interact with paxillin through its coiled-coil domain and localize to focal adhesions suggests that paxillin primarily recruits TRIM15 to focal adhesions. Sequence analysis of the focal-adhesion-targeting coiled-coil domain of TRIM15 revealed the presence of a putative paxillin-binding subdomain (PBS) related to the PBS found in FAK, vinculin and actopaxin (also known as α-parvin) that is also conserved among TRIM15 proteins across different species (supplementary material Fig. S2A,B) (Nikolopoulos and Turner, 2000). Structural analyses of FAK and actopaxin have suggested a direct or indirect role for the PBS in binding to paxillin (Hayashi et al., 2002; Lorenz et al., 2008). We introduced two point mutations (V213G and L216R) to disrupt the putative PBS (Nikolopoulos and Turner, 2000). These mutations reside near the end of the predicted coiled-coil domain of TRIM15 (supplementary material Fig. S2C). These point mutations did not disrupt the ability of the mutant protein to interact with wild-type TRIM15, suggesting that the protein structure was not significantly compromised (supplementary material Fig. S2D, lanes 7 and 10). However, co-immunoprecipitation and TIRFM experiments showed that the point mutations in PBS disrupted both the interaction of the coiled-coil domain with FLAG-tagged paxillin and its localization to focal adhesions (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6; Fig. 3D; supplementary material Fig. S3A). In addition, silencing paxillin expression in HeLa cells abolished the focal adhesion localization of the coiled-coil domain (Fig. 3E). These data ascertained the role of paxillin in targeting TRIM15 to focal adhesions.

Fig. 3.

TRIM15 localizes to focal adhesions by binding to paxillin through its coiled-coil domain. The schematic in A shows the domain structure of TRIM15 as a guide. Asterisks, point mutations (see below); R, RING domain; B, B-box domain; CC, coiled-coil domain. (A,C) Lysates from HEK293 cells coexpressing either FLAG-tagged paxillin (PXN, lanes 1–6) or empty FLAG vector (lanes 7–12) with YFP-tagged wild-type (RBCPS) TRIM15 or versions of TRIM15 containing deletions were immunoprecipitated using antibodies against the FLAG epitope. The amino acid coordinates of TRIM15 deletions are indicated. The immunoprecipitates (IP, anti-FLAG beads) and cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting (WB) using antibodies against FLAG or GFP. TRIM15 Bm carries two point mutations in the B-box (C83A, H86A). TRIM15 Cm (full-length protein) or CCm (coiled-coil domain alone) carry two point mutations in the coiled-coil domain (V213G, L1216R), which contains the putative paxillin-binding subdomain. (B,D) TIRFM images of HeLa cells expressing YFP fusions of wild-type (RBCPS) TRIM15 or the indicated mutant TRIM15 versions displayed along with grayscale processed images showing focal adhesion (FA) outlines. See also supplementary material Fig. S1D; Fig. S3A. (E) TIRFM images of HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting control (NTsi) or paxillin-specific (PXNsi) siRNA and coexpressing the YFP-tagged coiled-coil domain of TRIM15 (green) along with zyxin–mCherry (red). Arrows, presence or absence of TRIM15-CC–YFP signal at focal adhesions. Scale bars: 10 µm.

Interestingly, mutating the putative PBS in full-length TRIM15 diminished but did not abolish paxillin interaction and focal adhesion localization (Fig. 3C, lane 3; Fig. 3B). Because the B-box also contributed to the interaction with paxillin (Fig. 3A, lane 3), we introduced two point mutations (C83A and H86A) to disrupt the zinc finger and, consequently, the capacity of TRIM15 to form oligomers (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2009). Point mutations or the deletion of the B-box reduced but did not eliminate paxillin interaction and focal adhesion localization (Fig. 3C, lane 2; Fig. 3D; supplementary material Fig. S3A). However, a combination of the PBS and B-box mutations resulted in the severe loss of paxillin interaction and focal adhesion localization (Fig. 3C, lane 4; supplementary material Fig. S3A). The B-box domain alone was entirely cytoplasmic, suggesting that it does not contain an independent focal-adhesion-targeting sequence (supplementary material Fig. S3A, last column). Rather, given the general role of the B-box in the formation of higher-order TRIM oligomers (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2009), it was more likely that B-box-mediated oligomerization increased the avidity of the coiled-coil domain of TRIM15 for paxillin. Indeed, gel filtration showed that Escherichia coli-expressed and purified TRIM15 protein eluted near the void volume of the column, suggesting a higher-order oligomer-like structure. By contrast, the majority of TRIM15 lacking the B-box eluted as a major peak with a molecular mass of ∼114 kDa (determined using multi-angle laser light scattering analysis), which is close to the predicted dimer of 96.6 kDa. These data indicated that the B-box is required to form higher-order TRIM15 oligomers (supplementary material Fig. S2E). Thus, TRIM15 localizes to focal adhesions primarily because of an interaction between its coiled-coil domain and paxillin, and B-box-mediated formation of higher-order oligomers likely helps to increase the avidity of this interaction.

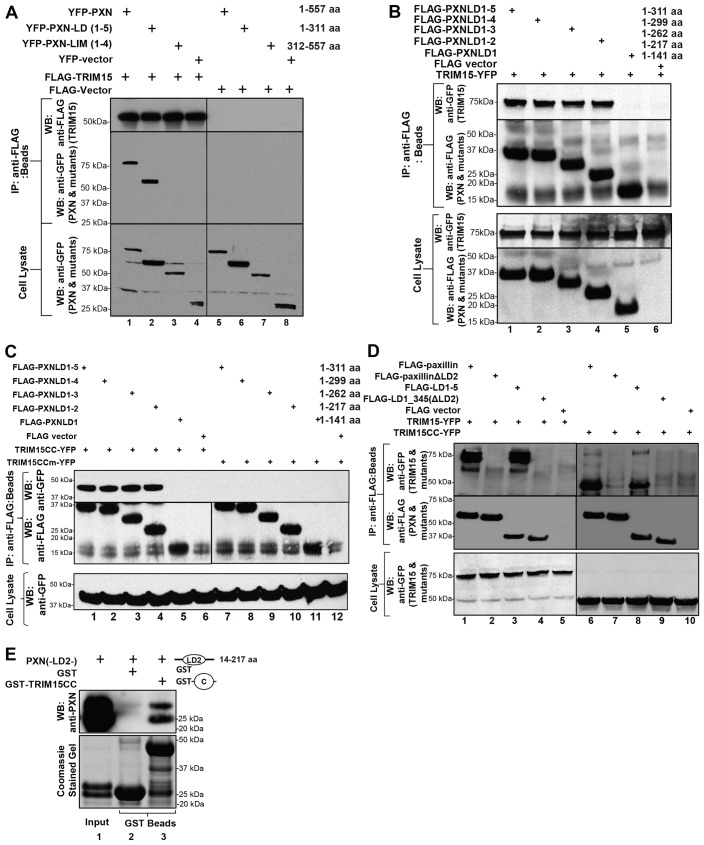

TRIM15 interacts with the LD2 motif in paxillin

Paxillin is a multidomain protein with five N-terminal Leu-Asp (LD) motifs and four C-terminal zinc-finger-containing LIM domains (Deakin and Turner, 2008). We generated various deletions of paxillin fused to YFP to map the TRIM15-interacting domain. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that the LD motifs and not the LIM domains of paxillin bind to FLAG-tagged TRIM15 (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3). Successive truncations of the LD motifs in paxillin indicated that the LD2 motif is crucial for the interaction with full-length TRIM15 (Fig. 4B, lane 5). We obtained similar results with only the coiled-coil domain of TRIM15, and the interaction was dependent on the putative PBS (Fig. 4C). Deleting the LD2 motif from paxillin (paxillin ΔLD2) or from the N-terminal LD1–5 fragment completely abrogated the interaction with TRIM15 or the coiled-coil domain by itself (Fig. 4D, lanes 2, 4 and lanes 7, 9). Furthermore, the interaction between the LD2 motif of paxillin and the coiled-coil domain of TRIM15 was direct, as both domains purified from E. coli co-precipitated with one another (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that TRIM15 localizes to focal adhesions by a direct interaction between its coiled-coil domain and the LD2 motif of paxillin.

Fig. 4.

TRIM15 interacts with the LD2 motif of paxillin. (A) TRIM15 interacts with the N-terminal LD-containing fragment of paxillin. Lysates from HEK293 cells coexpressing YFP-tagged wild-type or mutant paxillin (PXN) or empty vector together with either FLAG–TRIM15 (lanes 1–4) or empty FLAG vector control (lanes 5–8) were immunoprecipitated using antibodies against the FLAG epitope. The immunoprecipitates (IP, beads) and cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting (WB) using antibodies against GFP or FLAG as indicated. (B–D) Paxillin LD2 is required for an interaction with TRIM15. HEK293 cell lysates coexpressing the indicated wild-type or mutant FLAG-tagged paxillin variants or empty vector control together with full-length TRIM15–YFP, the coiled-coil domain (TRIM15CC–YFP) or the mutated coiled-coil domain (V213G, L1216R; TRIM15CCm–YFP) were immunoprecipitated and processed as described in A. The amino acid coordinates for paxillin deletions are also indicated. (E) Paxillin LD2 motif binds directly to TRIM15 coiled-coil domain in vitro. Paxillin LD2 [PXN(-LD2-)] protein (input) was incubated with glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of the TRIM15 coiled-coil domain (GST–TRIM15CC). GST was used as the specificity control. The co-precipitated LD2 protein was detected by western blotting using polyclonal anti-paxillin antibodies that can also recognize the LD2 region of paxillin (upper panel). A Coomassie-Blue-stained gel with the input LD2 and GST fusion proteins is shown below as a reference.

TRIM15-depleted cells are impaired in cell migration

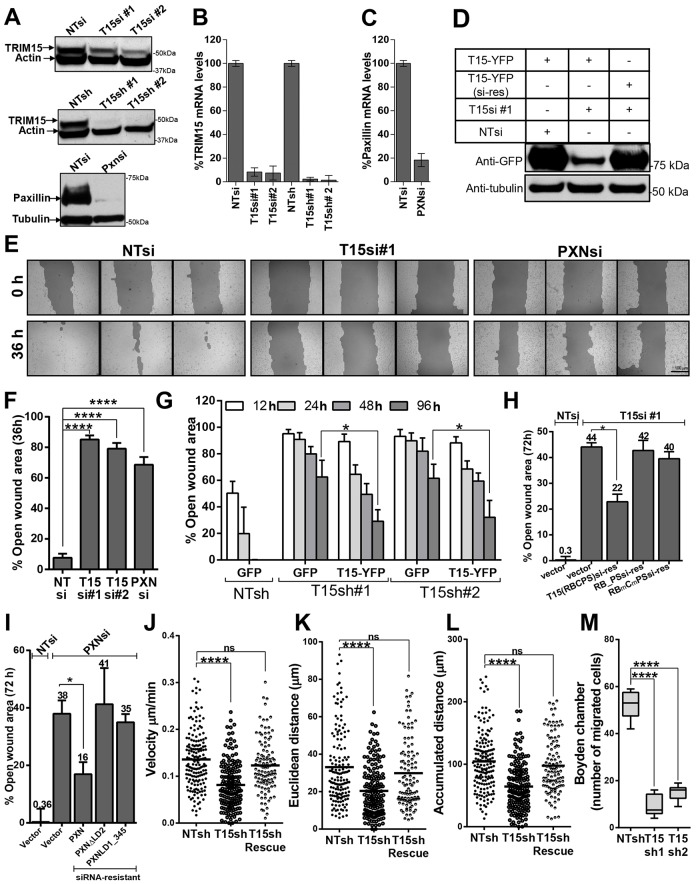

Paxillin is required for cell migration and spreading (Hagel et al., 2002). To test whether TRIM15 also plays a role in cell migration, we used RNAi to silence TRIM15 expression in HeLa cells and evaluated their capacity to heal wounded areas. We employed two siRNAs that target different coding regions and two small hairpin (sh)RNAs targeting the 3′UTRs in the TRIM15 mRNA. We used siRNA targeting paxillin as a positive control. The knockdown efficiencies for all siRNAs were >80% at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5A–C). To address potential off-target effects of siRNA, we made an siRNA-resistant version of TRIM15–YFP and confirmed it to be siRNA resistant by western blotting (Fig. 5D). We used a wild-type TRIM15–YFP construct to rescue protein expression in stable knockdown experiments, as the shRNAs targeted the 3′UTR of TRIM15 mRNA. Cells treated with non-targeting control siRNA covered the wounded area completely in 36 h. By contrast, wound closure by TRIM15- or paxillin-depleted cells was significantly compromised, leaving 70–80% of wound area open after 36 h (Fig. 5E,F). HeLa cells expressing two shRNAs targeting the TRIM15 3′UTR region also showed a similar defect in wound healing (Fig. 5G). The migration defect observed for both siRNA and shRNAs targeting TRIM15 could be partially rescued by expressing an siRNA-resistant or wild-type TRIM15, respectively, but not by expressing GFP or empty vector (Fig. 5G,H). The fact that rescue was only partial is likely because the transfection efficiency in our assays was ∼40–50%. Under these conditions, the rescue of paxillin-knockdown cells by siRNA-resistant paxillin also reached a similar efficiency (Fig. 5I). Importantly, siRNA-resistant versions of TRIM15 lacking the coiled-coil domain or with mutations in the B-box and PBS that cannot interact with paxillin failed to rescue the migration of TRIM15-depleted cells (Fig. 5H). Similarly, paxillin lacking the LD2 domain, which is required to recruit TRIM15 to focal adhesions, also failed to rescue the migration of paxillin-depleted cells.

Fig. 5.

TRIM15-depleted cells are impaired in cell migration and chemotaxis. (A) Western blot analyses to determine the levels of the indicated proteins using specific antibodies in lysates from cells that were treated with the indicated siRNAs [against TRIM15 (T15si) or paxillin (Pxnsi)] or that expressed shRNAs [against TRIM15 (T15sh)], compared with those of cells treated with non-targeting controls (NTsi or NTsh). (B,C) Efficiency of TRIM15 and paxillin knockdown in HeLa cells for the experiments shown in A. The mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR at 72 h post-siRNA treatment or shRNA expression. The data represent the mean±s.d. (two experiments performed in triplicate). (D) Western blot analysis using antibodies against GFP of cell lysates from HeLa cells treated with the indicated siRNAs and expressing either TRIM15–YFP or its siRNA-resistant version (T15–YFP si-res). (E) Phase images (triplicates) of a wounded HeLa cell monolayer treated with control siRNA (NTsi), TRIM15-specific siRNA (T15si#1) or paxillin-specific siRNA (PXNsi) taken at 0 and 36 h after scraping the confluent monolayer. Scale bar: 100 µm. (F) The percent open wound area was determined using Tscratch software for an experiment similar to that shown in E. (G) The percent open wound area at indicated time-points determined as in F during the course of a wound healing assay carried out in HeLa cells stably expressing the indicated shRNAs and transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated proteins. (H) A 72-h wound healing experiment similar to that shown in E, where TRIM15-siRNA-treated HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing empty vector as control or 100 ng of plasmids expressing the indicated siRNA-resistant versions of TRIM15 to rescue the migration defect. NTsi-treated cells were used as an additional control. (I) A plot of the percent open wound area at 72 h determined during the course of a wound healing assay performed in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting or paxillin-specific siRNA and transfected with 100 ng of plasmids expressing the indicated siRNA-resistant versions of paxillin for rescue. Data in F–I represent the mean±s.d. (three experiments performed in triplicate). (J–L) The indicated cell migration parameters were estimated from two-dimensional migration trajectories of >80 individual HeLa cells expressing non-targeting shRNA or TRIM15-specific shRNA with or without TRIM15–RFP for rescue after re-plating on fibronectin-coated coverslips. See supplementary material Movie 2. (M) The number of migrated cells in Boyden chambers was determined for HeLa cells stably expressing non-targeting shRNA or shRNA targeting two sequences in TRIM15 (T15sh1 and T15sh2). Data represent the mean±s.d. (two experiments performed in triplicate). *P<0.05; ****P<0.0001; ns, not significant.

We next extended our observations to HT1080 cells, which exhibit a migratory phenotype due to their mesenchymal origin. Time-lapse imaging of wound healing by HT1080 cells also revealed a pronounced defect in cell migration upon silencing of TRIM15 (supplementary material Fig. S3B; Movie 1). Analyses of motility profiles revealed a significant decrease in estimates of migration parameters such as velocity, accumulated as well as Euclidean distance and directionality (defined as the ratio of Euclidean to accumulated distance) in TRIM15-depleted cells compared with that of the control cells (supplementary material Fig. S3C–F). The majority of control-siRNA-treated cells had directness values close to one, indicating migration patterns that approached a straight line. By contrast, TRIM15-depleted cells displayed a wide range of values (supplementary material Fig. S3F). The impaired directionality of TRIM15-depleted HT1080 cells could be due to the formation of multiple lateral lamellipodia in various directions as compared with control cells that exhibited a single dominant leading edge (supplementary material Fig. S3B, last row). The expression of siRNA-resistant TRIM15 in TRIM15-depleted HT1080 cells partially rescued the defect in migration speed and distance (supplementary material Fig. S3C–F). The ∼60% transfection efficiency in our experiments likely permitted only a partial rescue. However, formation of uniform lamellipodia with dominant leading edges was substantially restored, resulting in near-complete rescue of directional persistence (supplementary material Fig. S3B–F; Movie 1).

Cell proliferation or alterations in cell–cell contacts can significantly influence wound healing assays. Therefore, we also monitored the migration of isolated HeLa cells re-plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips (supplementary material Movie 2). Analyses of migration trajectories showed that individual TRIM15-depleted cells displayed a deficiency in migration speed and distance estimates compared with that of control cells (Fig. 5J–L). Importantly, the expression of siRNA-resistant TRIM15 substantially rescued the defect in the estimated migration parameters (Fig. 5J–L). However, we did not observe any difference in directional persistence of HeLa cells as seen for HT1080 cells between control and TRIM15-depleted cells. This could be due to the different origin of HeLa and HT1080 cells (epithelial versus mesenchymal, respectively) and oncogene(s) expressed in these transformed cells. Finally, TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells were also impaired in serum-induced chemotactic motility in Boyden chamber migration assays (Fig. 5M). Thus, our data collectively point to a role for TRIM15 in cell migration and chemotaxis.

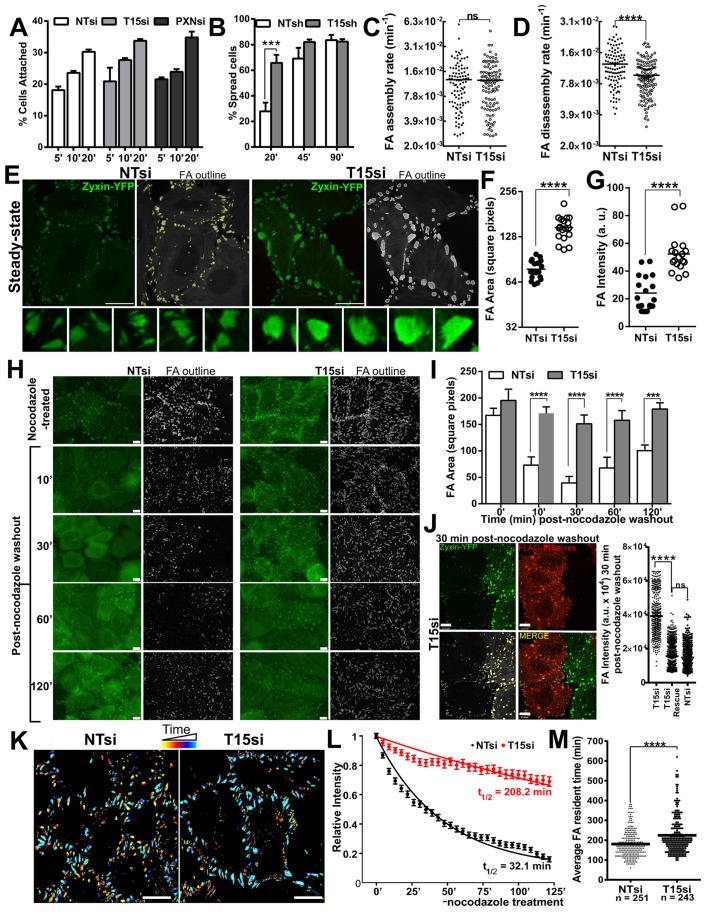

Focal adhesion disassembly is impaired in TRIM15-depleted cells

Cell migration depends on the controlled assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions. A defect in either interferes with cell migration (Broussard et al., 2008; Huttenlocher and Horwitz, 2011). We tested a possible role for TRIM15 in the focal adhesion assembly process by measuring the ability of TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells to attach and spread on fibronectin. TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells were not impaired in integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin (Fig. 6A). In addition, they were able to spread faster than the control cells at early times post-plating, suggesting that focal adhesion assembly was not impaired in TRIM15-depleted cells (Fig. 6B). Live-cell imaging of HeLa cells stably expressing the focal adhesion marker zyxin–YFP revealed that although the assembly rates of focal adhesions were similar, there was a significant reduction in disassembly rates between TRIM15-depleted and control cells (Fig. 6C,D; supplementary material Movie 3). Furthermore, we observed a significant enhancement in both focal adhesion area and intensity in TRIM15-depleted cells compared with that of the control cells (Fig. 6E–G). These data point to a role for TRIM15 in regulating focal adhesion dynamics during the disassembly step.

Fig. 6.

TRIM15 regulates cell spreading and focal adhesion disassembly. (A) HeLa cells treated with control (NTsi), TRIM15-specific (T15si) and paxillin-specific (PXNsi) siRNAs for 72 h were plated onto fibronectin-coated plates for the indicated times (min). The number of cells attached at each time-point was normalized to the total number of cells attached after 3 h. Data represent the mean±s.d. (three experiments performed in triplicate). (B) The spreading efficiency (on fibronectin-coated plates) of HeLa cells stably expressing shRNA#1 targeting TRIM15 (T15sh) or non-targeting (NTsh) at 20, 45 and 90 min after plating. Data represent the mean±s.d. (experiments performed three times on separate days in triplicate). (C,D) A plot of >100 focal adhesion (FA) assembly and disassembly rates computed from 2–3 h of time-lapse microscopy of HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP to label focal adhesions and treated with non-targeting or TRIM15-specific siRNA for 48–72 h. See supplementary material Movie 3. (E) Raw and grayscale processed images with outlines of individual focal adhesions of HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP treated with non-targeting siRNA or TRIM15-specific siRNA for 48–72 h at steady state. (F,G) Mean (horizontal black lines) of average focal adhesion area and intensity computed per image from 17–22 images taken randomly encompassing >50 cells for an experiment as shown in E. a.u., arbitrary units. (H) HeLa cells stably expressing the focal adhesion marker zyxin–YFP (green) transfected with either non-targeting siRNA or TRIM15-specific siRNA were serum starved and treated with 10 µM nocodazole for 4 h. At the indicated time (min) after nocodazole washout, cells were fixed and visualized. Fixed and grayscale processed images with focal adhesion outlines are shown. (I) A plot of average focal adhesion area (mean±s.d.) determined from analyses of 6–8 images taken randomly per time-point per sample for three experiments as shown in H. (J) Split, merged and grayscale processed images of an experiment as shown in H for HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP, treated with TRIM15-specific siRNA and transfected with plasmid expressing siRNA-resistant FLAG–TRIM15 (red) for rescue. The plot shows individual focal adhesion intensities computed from 80–100 cells from the indicated conditions. Scale bars: 10 µm. (K) Time-lapse color-coded images (yellow, early time-points; light blue, late time-points) of control and TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells during the focal adhesion disassembly assay shown in supplementary material Movie 4. Scale bars: 10 µm. (L) A plot of the average relative intensities of zyxin–YFP-labeled focal adhesions as a function of time tracked post-nocodazole washout during the focal adhesion disassembly assay, shown for control and TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells. A total of 201 and 175 focal adhesions were tracked for non-targeting-siRNA-treated and TRIM15-siRNA-treated cells, respectively. The indicated average half-lives of focal adhesions (t1/2) for each condition were calculated based on best-fit values using the exponential function y = exp(−k*t). The rate constant, k, for focal adhesions in non-targeting-siRNA-treated and TRIM15-siRNA-treated cells was 2.2×10−2 and 3.3×10−3 per min, respectively, see supplementary material Movie 4. (M) A plot of >200 focal adhesion resident times computed from 12–14 h of time-lapse microscopy of HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP and treated with non-targeting siRNA or TRIM15-specific siRNA for 48–72 h. ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; ns, not significant.

Under steady-state conditions, focal adhesions are constantly remodeled, making it difficult to exclusively study disassembly events. Therefore, we took advantage of a microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly assay, which allows one to monitor focal adhesion disassembly in a near-synchronous manner (Chao et al., 2010; Ezratty et al., 2005; Kaverina et al., 1999). We treated serum-starved HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP with nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules. The consequent inhibition of microtubule-induced turnover promoted the accumulation of focal adhesions. Washout of nocodazole led to a rapid and near-synchronous disassembly of focal adhesions in the majority of the control-siRNA-treated cells as previously described (Fig. 6H,I) (Ezratty et al., 2005). Disassembly reached its peak at 30 min post-nocodazole removal. By contrast, focal adhesion disassembly in TRIM15-depleted cells was significantly impaired, and focal adhesion area changed minimally following nocodazole washout (Fig. 6H,I). Importantly, as shown by the reduction in focal adhesion intensity at 30 min post-nocodazole washout in TRIM15-siRNA-treated cells, we were able to rescue the impaired focal adhesion disassembly by expressing siRNA-resistant FLAG–TRIM15 (Fig. 6J). We next monitored the nocodazole-induced focal adhesion disassembly by time-lapse imaging and determined the focal adhesion disassembly rates for TRIM15-depleted and control cells (Fig. 6K; supplementary material Movie 4). Our analysis revealed a ∼6.5-fold reduction in focal adhesion disassembly rate in TRIM15-depleted cells compared with that of the control cells (Fig. 6L). In addition, we also monitored focal adhesions through their entire life cycle from formation to dispersion, to gain insight into focal adhesion resident times by long-term live-cell imaging experiments at steady state. Focal adhesion resident times were significantly increased in TRIM15-depleted cells compared with those of the control cells (225 versus 180 min), supporting a role for TRIM15 in regulating focal adhesion dynamics (Fig. 6M).

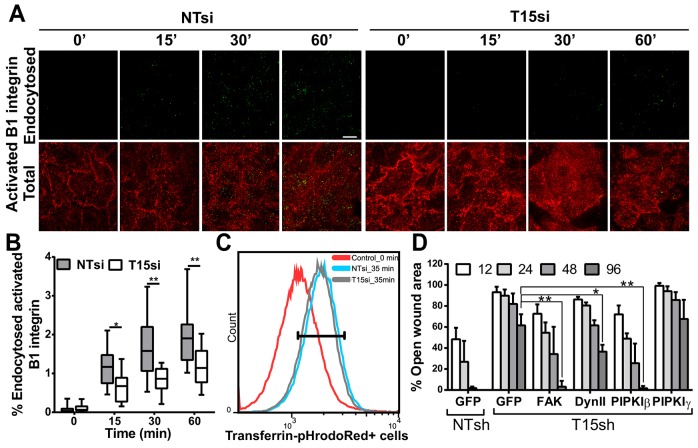

TRIM15-depleted cells show delayed endocytosis of activated β1 integrin

We next sought to determine the step that TRIM15 is likely to regulate in the focal adhesion disassembly process. FAK-dependent recruitment of dynamin 2 initiates focal adhesion disassembly by internalizing integrins from focal adhesion (Chao and Kunz, 2009; Ezratty et al., 2005). We therefore monitored the internalization of the activated form of β1 integrin in TRIM15-depleted and control HeLa cells using an antibody feeding assay with an antibody specific to activated β1 integrin (clone 12G10). Quantification of endocytosed integrin revealed that internalization in TRIM15-depleted cells occurred with a delayed kinetics compared with that of control cells (Fig. 7A,B). As a control, we monitored transferrin endocytosis, which was similar in both control and TRIM15-depleted cells (Fig. 7C). Endocytosis of integrins from focal adhesion requires FAK, dynamin 2 and PIPKIβ (Chao et al., 2010; Chao and Kunz, 2009; Ezratty et al., 2009). Indeed, ectopic expression of all three factors partially rescued the migration defect seen in TRIM15-depleted cells (Fig. 7D). By contrast, PIPKIγ661 (one of the major splice variants of PIPKIγ), which is required for focal adhesion formation, failed to rescue the defect (Ling et al., 2002). Collectively, these data suggest a role for TRIM15 in regulating focal adhesion disassembly by promoting integrin endocytosis.

Fig. 7.

Endocytosis of activated β1 integrin is delayed in TRIM15-depleted cells. (A) Subtracted images showing endocytosed β1 integrin (green) from an antibody feeding assay performed using Dylight-488-conjugated antibodies against activated β1 integrin (12G10) in HeLa cells treated with non-targeting or TRIM15-specific siRNA (NTsi or T15si, respectively) for the indicated times (min) are presented in the upper panel. Non-internalized antibodies corresponding to surface β1 integrin were detected using Alexa-Fluor-568-conjugated secondary antibodies (red). The merged images shown in the lower panel correspond to total β1 integrin. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) The box and whisker plot shows the normalized percentage of endocytosed integrin as a function of time for an experiment as shown in A from analyses of 17–18 images taken per time point per sample. The box shows the median, 25th and 75th percentiles. The whiskers show maximum and minimum values. (C) A FACS histogram plot of control or TRIM15-depleted HeLa cells showing the uptake of transferrin conjugated to the pH-sensitive dye pHrodoRed at the end of 35 min. HeLa cells treated similarly but maintained at 4°C (0 min) were used as the negative control. 84.9% of control cells and 84% of TRIM15-siRNA-treated cells were positive for transferrin in the gated area. (D) The percentage open wound area at the indicated time-points (h) was determined using images analyzed by Tscratch software during the course of the wound healing assay that was performed using HeLa cells stably expressing either non-targeting or TRIM15-specific shRNA (NTsh or T15sh, respectively) and transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated proteins. Data show the mean±s.d.; *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

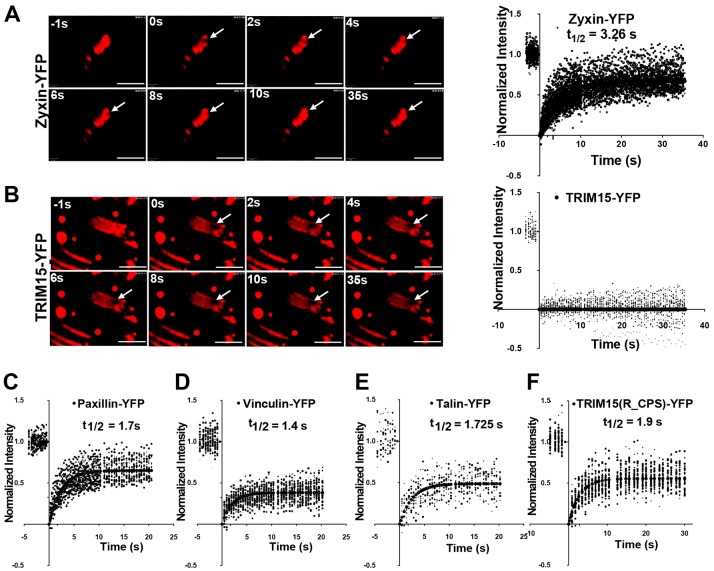

TRIM15 is a stable focal adhesion component

Our data showed that TRIM15 localizes early during focal adhesion biogenesis but functions during the focal adhesion disassembly process. It was therefore of interest to study the dynamic behavior of TRIM15 within focal adhesions to gain insight into its mode of action. We carried out fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analyses of transiently expressed YFP-tagged TRIM15 or control focal adhesion proteins in HeLa cells. Surprisingly, in contrast to the rapid recovery rates observed for zyxin, paxillin, talin and vinculin, TRIM15 completely failed to recover from photobleaching, a phenotype not previously reported for any other focal adhesion protein (Fig. 8A–E). Interestingly, the B-Box-deleted TRIM15 mutant that cannot form oligomers recovered as quickly as other focal adhesion proteins after photobleaching (Fig. 8F). Thus, B-box-mediated oligomerization must contribute to TRIM15 function as a stable focal-adhesion-resident protein that likely turns over when the entire focal adhesion disassembles.

Fig. 8.

TRIM15 is a stable focal adhesion protein and its turnover depends on its ability to form oligomers. (A–F) The indicated YFP fusion proteins of zyxin, TRIM15, paxillin, vinculin, talin and TRIM15 carrying a B-box deletion (R_CPS) were expressed in HeLa cells and were subjected to FRAP analyses during which a micropoint laser bleached a small area within a single focal adhesion (arrows in A,B) and the recovery of fluorescence was recorded over time (in seconds). Selected images from FRAP time-lapse videos are shown for YFP-tagged zyxin (A) and TRIM15 (B). The plots in A–F show fluorescence recovery experiments performed on numerous focal adhesions for the indicated proteins in seconds following photobleaching (t = 0). A total of 47, 21, 24, 34, 11 and 49 focal adhesions were analyzed for YFP-tagged zyxin, TRIM15, paxillin, vinculin, talin and R_CPS, respectively. The indicated half times for recovery (t1/2) were determined based on best-fit curves. Note that TRIM15 does not recover after photobleaching and therefore t1/2 values could not be computed. Scale bars: 2 µm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe a new focal adhesion protein, TRIM15, that localizes to focal adhesions primarily due to an interaction with the focal adhesion adaptor protein paxillin. Depletion or absence of paxillin expression substantially reduced but did not eliminate the localization of TRIM15 to focal adhesions indicating a role, albeit a minor one, for another focal adhesion component(s) in the localization of TRIM15. Likely candidates include members of the paxillin superfamily [such as Hic-5 (also known as TGFB1I1) and leupaxin] that share a subset of paxillin-binding proteins. However, these proteins were not detected in mass spectrometric analyses of TRIM15 immunoprecipitates. Hic-5, which is expressed at similar levels in wild-type and paxillin-null MEFs (Wade et al., 2002), could not substitute for paxillin in promoting robust focal adhesion localization of TRIM15. Thus, the TRIM15 interaction appears to be predominantly paxillin specific and weak towards other members of paxillin family.

Paxillin is known to be regulated by ubiquitylation (Didier et al., 2003; Iioka et al., 2007), and TRIM15 contains a RING domain that is associated with E3 ligase activity. However, we did not observe any changes in the ubiquitylation profile of paxillin in the presence of TRIM15 (supplementary material Fig. S4A). In addition, the RING-domain-deleted mutant of TRIM15 was able to rescue the defect in the migration of TRIM15-depleted cells, suggesting that the E3 ligase activity might not be required for TRIM15 function at focal adhesions (supplementary material Fig. S4B). Alternatively, TRIM15 could regulate the binding of paxillin-interacting proteins. TRIM15 binds to the LD2 motif of paxillin, which also recruits several other key regulators of focal adhesions, such as FAK and vinculin. Presumably, FAK and vinculin can still interact as they both bind to additional motifs in paxillin. Nevertheless, TRIM15 could function to regulate the recruitment of FAK or its activity, as overexpression of FAK was able to partially rescue the migration defect seen in TRIM15-depleted cells.

TRIM15 localized to focal contacts early during focal adhesion biogenesis. However, depletion of TRIM15 had no effect on focal adhesion assembly rates at steady state. The faster spreading observed in TRIM15-depleted cells is thus likely to be a consequence of the observed decrease in disassembly rates. Cell migration and spreading is a result of a balance between assembly and disassembly kinetics. Supplementary material Movie 3 documents how focal adhesions often initiated disassembly shortly after formation in control cells, whereas in TRIM15-depleted cells where disassembly rates were reduced, focal adhesions continued to grow, increasing to larger sizes with a resulting increase in focal adhesion lifetimes.

FRAP analyses revealed that focal-adhesion-resident TRIM15 did not recover its fluorescence after photobleaching, a feature dependent on the B-box that mediates oligomerization. These data are intriguing as all other focal adhesion components – including paxillin, which recruits TRIM15 to focal adhesions – displayed fast recovery kinetics. However, the recovery of total paxillin fluorescence ranged between 60 and 80% of the pre-bleach intensity. This indicated that 20–40% of paxillin at focal adhesions was immobile. We speculate that TRIM15 could be associated specifically with the immobile pool of paxillin. Alternatively, the activities of oligomerization and dimerization domains, the B-box and coiled-coil regions, might result in the formation of a stable oligomeric lattice-like structure. In a lattice, individual TRIM15 molecules would be immobile due to stable interactions with their neighbors and thus would not recover from photobleaching. In support of this hypothesis, we observed that TRIM15 disassembles from focal adhesions predominantly as oligomeric bodies, in contrast to zyxin, which dispersed readily into the actin stress fibers and cytoplasm during focal adhesion disassembly (supplementary material Movie 5). Thus, these data add to the emerging ability of TRIM proteins to form higher-order oligomers due to interactions through their B-box, a feature crucial for their ability to form signaling platforms as well as to their function (Borden et al., 1996; Diaz-Griffero et al., 2009; Ganser-Pornillos et al., 2011; Pertel et al., 2011; Uchil et al., 2013).

We hypothesize that TRIM15 is incorporated early into assembling focal adhesions to form a platform that orchestrates the recruitment of disassembly factors to promote focal adhesion disassembly. It is important to note that focal adhesion disassembly does occur in TRIM15-depleted cells, although at a slower rate. As a result, overexpression of PIPKIβ, FAK and dynamin 2, factors that control integrin endocytosis and focal adhesion disassembly, partially rescued the migration defect in TRIM15-knockdown cells. Thus, our study has identified a novel focal adhesion protein, TRIM15, which localizes to focal adhesions due to its interaction with paxillin and regulates focal adhesion turnover – likely by promoting focal adhesion disassembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs

Human and mouse TRIM15 were as described previously (NM_033229; NM_001024134) (Uchil et al., 2008). GFP-, FLAG- and GST-tagged human TRIM15 were generated in pEYFP/CFP-N1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), pCMV3Tag1A (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and pGEX6p-1 (GE biosciences). The YFP-fusion deletion mutants _BCPS, _CPS, _PS, RBC_, R_CPS and RB_CPS lacked the amino acids 1–64, 1–119, 1–245, 346–465 81–119 and 129–245, respectively. CC–YFP or FLAG–CC corresponded to amino acids 120–292. We generated FLAG-, YFP- and GST-tagged paxillin and its deletions in pCMV3Tag1A, EYFP C2 and pGEX6p-1. The amino acids that were deleted in the paxillin deletion mutants were as follows: LD1, 1–141; LD1–2, 1–217; LD1–3, 1–262; LD1–4, 1–299; LD1–5, 1–311 and LIM, 312–557. The LD2 motif (LD2) contained amino acids 14–217. Point mutations in the TRIM15 B-box zinc finger (C83A, H86A), paxillin-binding subdomain (V213G, L216R) and five silent mutations (TRIM15 amino acids 7–11) in the siRNA-binding region were created using QuikChange (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Zyxin–YFP was also cloned into retrovirus expression vector pLPCX (Clontech; puromycin resistance) for the generation of the stable expression HeLa cell line. We replaced the YFP in the TRIM15-EYFP-N1 and EYFP-paxillin-C1 constructs with mEOS3.2 to generate the fusion proteins for super-resolution imaging. Supplementary material Table S2 lists additional constructs and their sources.

Cell culture, transfection, reagents and antibodies

HEK293, HeLa, HepG2, MDCK, U2OS, HT1080 (ATCC) and paxillin-null cells were maintained in DMEM and 10% FBS (GeminiBiotech) under 5% CO2. Paxillin-null MEFs, a gift from Christopher Turner (SUNY, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY), were originally generated by Sheila Thomas (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA). HEK293 cells, HeLa cells and paxillin-null MEFs were transfected with FuGENE6, FuGENE HD (Promega) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively. We treated HeLa cells with blebbistatin (Toronto Research Chemicals) for 2 h at a concentration of 40 µM. The antibodies used were as follows: polyclonal anti-TRIM15 (13623-1-AP; Proteintech Group); anti-GFP (A-11122; Life Technologies); anti-actin (A2066), anti-tubulin (clone TUB 2.1), anti-FLAG M2 beads (A2220), anti-Myc (C3956) and anti-vinculin (clone hVIN-1) (all from Sigma); anti-paxillin (610568 for western blotting; 612405 for immunoprecipitation, from BD Transduction Laboratories); anti-phosphotyrosine (clone 4G10; Millipore); and anti-6×His (clone HIS.H8; Thermo Fisher).

Gene silencing

Supplementary material Table S3 lists the sequences and sources of siRNAs and GIPZ microRNA-adapted shRNAs (shRNAmirs) used to silence human TRIM15 and paxillin, and of the non-targeting (NT) luciferase control. siRNAs were introduced into HeLa or HT1080 cells using 1 µl of Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) for 80 nmol siRNA. We tested knockdown efficiencies of individual siRNAs and shRNAmirs by monitoring protein levels and RNA levels by real-time PCR. HeLa cells stably expressing shRNAs were generated using lentivirus infection followed by puromycin selection.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HEK293 or HeLa cells expressing tagged TRIM15 derivatives and the indicated focal adhesion components were lysed with co-immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1% CHAPSO, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor mix) on ice for 20 min. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min and the supernatant was incubated overnight with anti-FLAG-M2 antibodies bound to Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen). Immunocomplexes were washed with immunoprecipitation lysis buffer and resuspended in 1× LDS sample buffer. We analyzed the samples using SDS-PAGE (10% gels) followed by western blotting using antibodies against GFP, FLAG or paxillin. For co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous paxillin, HepG2 cells were used and processed as above using antibodies against paxillin (BD Transduction Laboratories), and western blots were probed with antibodies against TRIM15 (Proteintech) and paxillin (Cell Signaling).

Microscopy

Imaging of fixed samples for immunofluorescence and phase contrast microscopy was carried out using an inverted Nikon Eclipse TE-2000 microscope system or with a Volocity spinning disk confocal microscope (Nikon TE 2000-E) using a 60×/1.4 Plan Apo VC oil or 10×/0.25 NA objectives. The confocal microscope was equipped with appropriate lasers and a mercury lamp as the light source. We carried out laser and wide-field TIRF microscopy using a Nikon TE-2000 microscope equipped with TIRF setup, 100×/1.49 NA Apo TIRF oil objective, an evanescent field depth of ∼150 nm and appropriate lasers or X-cite series 120-W mercury lamp as the illumination system. We carried out time-lapse imaging using the Volocity spinning disc confocal system equipped with an environmental chamber (LiveCell; Pathology Devices), objective heater, Nikon T-Perfect Focus and automated XYZ stage for continuous sequential imaging at multiple points. We captured all images with Orca ER or EM-CCD digital camera from Hamamatsu.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were transfected with the indicated constructs, fixed after 24 h with paraformaldehyde and immunostained as indicated with the antibodies listed above. All images were analyzed and quantified using Volocity 6.3 (PerkinElmer) or CellProfiler 2.0 (Lamprecht et al., 2007). CellProfiler was used for processing the images to detect and outline individual focal adhesions.

In vitro binding assays

pGEX6P-1 carrying the paxillin LD2 motif (amino acids 14–217) and the TRIM15 coiled-coil domain were transformed into the BL21codon plus (DE3) RIL strain of E. coli (Stratagene) for protein expression. Proteins were purified using MagneGST purification system (Promega). The GST-tag of GST–LD2 protein was removed using the GST-PreScission Protease system (GE Biosciences). A total of 25 µg of LD2 protein was incubated at 4°C with 25 µg of MagneGSTbead-bound coiled-coil domain in in vitro binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 50% glycerol, protease inhibitor mix cocktail (Roche)]. MagneGST beads were isolated using a magnet, washed twice with binding buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and three times with 450 mM NaCl. Co-precipitated proteins were resuspended in 1× LDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gels) followed by Coomassie Blue staining and western blotting using antibodies against paxillin.

Cell migration assays

HeLa cells were transfected with 80 nM of siRNA targeting TRIM15, paxillin or luciferase (as a non-targeting control) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For rescue experiments, the cells were transfected 24 h later with plasmids expressing YFP, siRNA-resistant TRIM15–YFP, paxillin mutants or the indicated factors using Fugene HD (Roche). The transfection efficiencies ranged between 40 and 50%, as judged by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses of transfected cells performed in parallel 24 h post-transfection. After an additional 24 h, we wounded the cell monolayers by scratching with a P1000 pipet tip. The monolayer was washed and then maintained in DMEM containing 3% serum. We imaged the wounded area immediately after wounding and at 12-h intervals thereafter. The images were analyzed to determine the percentage of open wound area (which was set as 100% at t = 0) using Tscratch (Gebäck et al., 2009). For time-lapse imaging experiments, HT1080 cells grown on coverslips were transfected with siRNAs as above. After 48 h, half of the confluent monolayer was scraped using a blade, washed, placed in an imaging chamber (Harvard Apparatus) and imaged for 12–14 h. For single-cell migration assays, siRNA-treated HeLa cells with or without the expression of an siRNA-resistant version of TRIM15–RFP were trypsinized and re-plated at low confluency on fibronectin-treated coverslips. The cells were allowed to recover for 12 h before imaging them as above for 12–14 h. Time-lapse videos were processed using Volocity 6.3 (PerkinElmer). We tracked single cells using the Manual Tracking plug-in in ImageJ. We processed the tracking data with Chemotaxis and Migration Tool (Ibidi, Germany) to calculate various cell migration parameters.

Boyden chamber assays

8-µm pore membrane Transwell inserts (Costar) were coated on the lower surface with 10 µg/ml fibronectin. Chemotaxis was evaluated by including 10% FBS in the lower well. Serum-starved HeLa cells stably expressing either non-targeting shRNA or shRNA against TRIM15 were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells in the upper chamber and allowed to migrate for 3 h. We removed the non-migrated cells from the upper chamber using a cotton swab, fixed the transwells and stained them with a 5% solution of Crystal Violet in ethanol. We counted the stained migrated cells at the bottom of the membrane by imaging.

Cell spreading and attachment assays

A total of 1×104 HeLa cells stably expressing shRNA targeting TRIM15 or non-targeting control shRNA were added to a 96-well plate coated with 10 µg/ml fibronectin, and the cells were allowed to spread for 20, 45 and 90 min. Cells were fixed and visualized, and the total number of spread and non-spread cells was quantified (Humphries, 2001). For attachment assays, cells were allowed to attach for the indicated times, were washed and attached cell numbers were quantified using CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent kit (Promega). The total number of cells attached at 3 h was set to 100%.

Analyses of focal adhesion dynamics

HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP were seeded on fibronectin-coated glass-bottomed dishes. After attachment, cells were transfected with siRNA targeting TRIM15 or with non-targeting control siRNA. Live-cell imaging was carried out at 72 h post-siRNA treatment as described above for 2–3 h or 12–14 h to determine focal adhesion assembly and disassembly rates and resident times, respectively, under steady-state conditions. Focal adhesion lifetime was calculated as the total time an adhesion takes from its half-peak intensity to reach the peak intensity and return to its half-peak intensity from its peak intensity (Slack-Davis et al., 2007). The images were processed for estimation of various parameters using Focal Adhesion Analysis Server (FAAS) (Berginski et al., 2011).

Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly assays were performed as described previously (Ezratty et al., 2005). HeLa cells stably expressing zyxin–YFP were transfected with siRNA targeting TRIM15 or with non-targeting control siRNA. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were maintained in serum-free medium containing 0.2% BSA (SFM-BSA) and transfected with construct expressing siRNA-resistant FLAG–TRIM15 for rescue experiments. After 24 h, cells were treated either with DMSO or 10 µM nocodazole for 4 h. Monolayers were washed and incubated in SFM-BSA for the indicated times and fixed for imaging. Focal adhesions were detected and outlined, and their area and intensities were analyzed using CellProfiler 2.0. For time-lapse imaging experiments, we processed the cells as described above and imaged for 30–45 min in the presence of nocodazole and 2 h after washout. Fluorescence intensities of ≤100 individual focal adhesions (5–6 time-lapse videos) were determined at each time-point using a custom-designed MATLAB script. For normalization, the maximum intensity achieved by a focal adhesion tracked through time was set to 1. The normalized relative intensities at each time-point were averaged across all focal adhesions. The averaged relative intensity was plotted and fitted to an exponential function, which allowed the determination of the focal adhesion disassembly rates as described previously (Webb et al., 2004).

β1 integrin internalization assay

HeLa cells were transfected with TRIM15-specific siRNA or non-targeting siRNA and starved overnight after 48 h in serum-free DMEM. Dylight-488-conjugated (green channel) antibody against the activated form of human β1 integrin (Novus Biologicals; clone 12G10) was added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound antibodies were removed by washing, and samples were chased for the indicated times at 37°C and fixed. The non-internalized antibodies on the surface were detected using Alexa-Fluor-568-conjugated secondary antibodies (red channel). Z-stack images through the entire volume of cells were acquired using spinning-disk confocal microscope and flattened to obtain extended-focus images. The red channel images (outside only) were subtracted from the corresponding green (total) channel to obtain images for internalized integrin. The percentage of endocytosed integrin was determined by estimating the fluorescence intensity of the subtracted image after normalizing with the corresponding intensity in the green channel (total) set to 100 using Cell Profiler 2.0. In total, 17 or 18 images for each time-point and condition were analyzed and plotted. As a control, we monitored transferrin endocytosis by treating serum-starved cells with 25 µg/ml of pHrodoRed-conjugated transferrin (Life Technologies), which fluoresces only when transferrin is internalized into acidic endocytic compartments. We monitored transferrin uptake by FACS analyses at the end of 35 min or by time-lapse microscopy.

FRAP analyses

HeLa cells expressing YFP fusions of the indicated focal adhesion proteins were seeded on fibronectin-coated MatTek dishes and imaged using a 60× Nikon objective (NA 1.4) as above. Photobleaching was performed using the Micropoint ablation laser system (Andor Technology) equipped with a nitrogen-pumped dye laser delivering a wavelength of 405 nm. The laser spot size was set to a diameter of ∼200 nm. After acquiring pre-bleach images, a small area within a single focal adhesion was bleached, and fluorescence recovery images were acquired at maximum speed using Volocity FRAP acquisition software of the spinning-disc confocal microscope (PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis

We used the Student's t-test, available in GraphPad Prism v6 to determine the statistical significance of the data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Taplin Mass Spectrometric facility at Harvard Medical School for sample analyses; Pekka Lappalainen (University of Helsinki, Finland), Richard Anderson (University of Wisconsin-Madison, WI), Pietro de Camilli and Brett Lindenbach (Yale University, New Haven, CT) and Chris Turner (SUNY, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY) for reagents and cells; Joseph Luna and Clinton Bradfield for support; and Priti Kumar, Thomas Biederer and Xaver Sewald (Yale University, New Haven, CT) for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Felix Rivera-Molina and Derek Toomre (Yale University, New Haven, CT) for help with TIRFM.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

P.D.U. and W.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. D.A.C., J.B. and Y.X. provided expert advice. P.D.U. carried out of the experiments with assistance from contributing authors. T.P., T.R., S.D., A.H. W.H., H.Y., F.H. and R.F. helped in generating constructs for imaging, image acquisition and analyses, immunoprecipitation experiments or protein purification. J.M. wrote the Matlab script used to analyze images to calculate focal adhesion disassembly rates.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R21AI087467 and ROI CA098727 to W.M. and GM-068600 to D.A.C.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.143537/-/DC1

References

- Abercrombie M., Heaysman J. E., Pegrum S. M. (1971). The locomotion of fibroblasts in culture. IV. Electron microscopy of the leading lamella. Exp. Cell Res. 67, 359–367 10.1016/0014-4827(71)90420-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berginski M. E., Vitriol E. A., Hahn K. M., Gomez S. M. (2011). High-resolution quantification of focal adhesion spatiotemporal dynamics in living cells. PLoS ONE 6, e22025 10.1371/journal.pone.0022025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden K. L., Lally J. M., Martin S. R., O'Reilly N. J., Solomon E., Freemont P. S. (1996). In vivo and in vitro characterization of the B1 and B2 zinc-binding domains from the acute promyelocytic leukemia protooncoprotein PML. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 1601–1606 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard J. A., Webb D. J., Kaverina I. (2008). Asymmetric focal adhesion disassembly in motile cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 85–90 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K., Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. (1996). Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 463–519 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao W. T., Kunz J. (2009). Focal adhesion disassembly requires clathrin-dependent endocytosis of integrins. FEBS Lett. 583, 1337–1343 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao W. T., Ashcroft F., Daquinag A. C., Vadakkan T., Wei Z., Zhang P., Dickinson M. E., Kunz J. (2010). Type I phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase beta regulates focal adhesion disassembly by promoting beta1 integrin endocytosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 4463–4479 10.1128/MCB.01207-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin N. O., Turner C. E. (2008). Paxillin comes of age. J. Cell Sci. 121, 2435–2444 10.1242/jcs.018044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio A., Perez-Jimenez R., Liu R., Roca-Cusachs P., Fernandez J. M., Sheetz M. P. (2009). Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science 323, 638–641 10.1126/science.1162912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F., Qin X. R., Hayashi F., Kigawa T., Finzi A., Sarnak Z., Lienlaf M., Yokoyama S., Sodroski J. (2009). A B-box 2 surface patch important for TRIM5alpha self-association, capsid binding avidity, and retrovirus restriction. J. Virol. 83, 10737–10751 10.1128/JVI.01307-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier C., Broday L., Bhoumik A., Israeli S., Takahashi S., Nakayama K., Thomas S. M., Turner C. E., Henderson S., Sabe H. et al. (2003). RNF5, a RING finger protein that regulates cell motility by targeting paxillin ubiquitination and altered localization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5331–5345 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5331-5345.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A., Schiefermeier N., Grigoriev I., Ohi R., Brown M. C., Turner C. E., Small J. V., Kaverina I. (2008). Paxillin-dependent stimulation of microtubule catastrophes at focal adhesion sites. J. Cell Sci. 121, 196–204 10.1242/jcs.012666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty E. J., Partridge M. A., Gundersen G. G. (2005). Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 581–590 10.1038/ncb1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty E. J., Bertaux C., Marcantonio E. E., Gundersen G. G. (2009). Clathrin mediates integrin endocytosis for focal adhesion disassembly in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 187, 733–747 10.1083/jcb.200904054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganser-Pornillos B. K., Chandrasekaran V., Pornillos O., Sodroski J. G., Sundquist W. I., Yeager M. (2011). Hexagonal assembly of a restricting TRIM5alpha protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 534–539 10.1073/pnas.1013426108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebäck T., Schulz M. M., Koumoutsakos P., Detmar M. (2009). TScratch: a novel and simple software tool for automated analysis of monolayer wound healing assays. Biotechniques 46, 265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Spatz J. P., Bershadsky A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33 10.1038/nrm2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z., Noss E. H., Hsu V. W., Brenner M. B. (2011). Integrins traffic rapidly via circular dorsal ruffles and macropinocytosis during stimulated cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 193, 61–70 10.1083/jcb.201007003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagel M., George E. L., Kim A., Tamimi R., Opitz S. L., Turner C. E., Imamoto A., Thomas S. M. (2002). The adaptor protein paxillin is essential for normal development in the mouse and is a critical transducer of fibronectin signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 901–915 10.1128/MCB.22.3.901-915.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K., Lou D. I., Sawyer S. L. (2011). Identification of a genomic reservoir for new TRIM genes in primate genomes. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002388 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi I., Vuori K., Liddington R. C. (2002). The focal adhesion targeting (FAT) region of focal adhesion kinase is a four-helix bundle that binds paxillin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 101–106 10.1038/nsb755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino D., Nagano M., Saitoh A., Koshikawa N., Suzuki T., Seiki M. (2013). The phosphoinositide-binding protein ZF21 regulates ECM degradation by invadopodia. PLoS ONE 8, e50825 10.1371/journal.pone.0050825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries M. J. (2001). Cell adhesion assays. Mol. Biotechnol. 18, 57–61 10.1385/MB:18:1:57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries J. D., Byron A., Bass M. D., Craig S. E., Pinney J. W., Knight D., Humphries M. J. (2009). Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci. Signal. 2, ra51 10.1126/scisignal.2000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher A., Horwitz A. R. (2011). Integrins in cell migration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005074 10.1101/cshperspect.a005074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O., Destree A. T. (1978). Relationships between fibronectin (LETS protein) and actin. Cell 15, 875–886 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iioka H., Iemura S., Natsume T., Kinoshita N. (2007). Wnt signalling regulates paxillin ubiquitination essential for mesodermal cell motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 813–821 10.1038/ncb1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilić D., Furuta Y., Kanazawa S., Takeda N., Sobue K., Nakatsuji N., Nomura S., Fujimoto J., Okada M., Yamamoto T. (1995). Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature 377, 539–544 10.1038/377539a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina I., Krylyshkina O., Small J. V. (1999). Microtubule targeting of substrate contacts promotes their relaxation and dissociation. J. Cell Biol. 146, 1033–1044 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J. C., Han X., Hsiao C. T., Yates J. R., 3rd, Waterman C. M. (2011). Analysis of the myosin-II-responsive focal adhesion proteome reveals a role for β-Pix in negative regulation of focal adhesion maturation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 383–393 10.1038/ncb2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht M. R., Sabatini D. M., Carpenter A. E. (2007). CellProfiler: free, versatile software for automated biological image analysis. Biotechniques 42, 71–75 10.2144/000112257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitis C. M., Webb D. J., Donais K., Horwitz A. F. (2001). Differential dynamics of alpha 5 integrin, paxillin, and alpha-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1427–1440 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K., Doughman R. L., Firestone A. J., Bunce M. W., Anderson R. A. (2002). Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature 420, 89–93 10.1038/nature01082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz S., Vakonakis I., Lowe E. D., Campbell I. D., Noble M. E., Hoellerer M. K. (2008). Structural analysis of the interactions between paxillin LD motifs and alpha-parvin. Structure 16, 1521–1531 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab F. W., Rajsbaum R., Stoye J. P., O'Garra A. (2011). Tripartite-motif proteins and innate immune regulation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 46–56 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano M., Hoshino D., Koshikawa N., Akizawa T., Seiki M. (2012). Turnover of focal adhesions and cancer cell migration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 310616 10.1155/2012/310616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos S. N., Turner C. E. (2000). Actopaxin, a new focal adhesion protein that binds paxillin LD motifs and actin and regulates cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1435–1448 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek S. P., Huttenlocher A., Horwitz A. F., Lauffenburger D. A. (1998). Physical and biochemical regulation of integrin release during rear detachment of migrating cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 929–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasapera A. M., Schneider I. C., Rericha E., Schlaepfer D. D., Waterman C. M. (2010). Myosin II activity regulates vinculin recruitment to focal adhesions through FAK-mediated paxillin phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 188, 877–890 10.1083/jcb.200906012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertel T., Hausmann S., Morger D., Züger S., Guerra J., Lascano J., Reinhard C., Santoni F. A., Uchil P. D., Chatel L. et al. (2011). TRIM5 is an innate immune sensor for the retrovirus capsid lattice. Nature 472, 361–365 10.1038/nature09976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond A., Meroni G., Fantozzi A., Merla G., Cairo S., Luzi L., Riganelli D., Zanaria E., Messali S., Cainarca S. et al. (2001). The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 20, 2140–2151 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes D. A., de Bono B., Trowsdale J. (2005). Relationship between SPRY and B30.2 protein domains. Evolution of a component of immune defence? Immunology 116, 411–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller H. B., Friedel C. C., Boulegue C., Fassler R. (2011). Quantitative proteomics of the integrin adhesome show a myosin II-dependent recruitment of LIM domain proteins. EMBO Rep. 12, 259–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober M., Raghavan S., Nikolova M., Polak L., Pasolli H. A., Beggs H. E., Reichardt L. F., Fuchs E. (2007). Focal adhesion kinase modulates tension signaling to control actin and focal adhesion dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 176, 667–680 10.1083/jcb.200608010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short K. M., Cox T. C. (2006). Subclassification of the RBCC/TRIM superfamily reveals a novel motif necessary for microtubule binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8970–8980 10.1074/jbc.M512755200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack-Davis J. K., Martin K. H., Tilghman R. W., Iwanicki M., Ung E. J., Autry C., Luzzio M. J., Cooper B., Kath J. C., Roberts W. G. et al. (2007). Cellular characterization of a novel focal adhesion kinase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14845–14852 10.1074/jbc.M606695200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens S., Wittmann T. (2012). Targeting and transport: how microtubules control focal adhesion dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 198, 481–489 10.1083/jcb.201206050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M., Owens C. M., Perron M. J., Kiessling M., Autissier P., Sodroski J. (2004). The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427, 848–853 10.1038/nature02343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M., Perron M., Welikala S., Sodroski J. (2005). Species-specific variation in the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5alpha determines the potency of human immunodeficiency virus restriction. J. Virol. 79, 3139–3145 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3139-3145.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. E., Glenney J. R., Jr, Burridge K. (1990). Paxillin: a new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1059–1068 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchil P. D., Quinlan B. D., Chan W. T., Luna J. M., Mothes W. (2008). TRIM E3 ligases interfere with early and late stages of the retroviral life cycle. PLoS Pathog. 4, e16 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchil P. D., Hinz A., Siegel S., Coenen-Stass A., Pertel T., Luban J., Mothes W. (2013). TRIM protein-mediated regulation of inflammatory and innate immune signaling and its association with antiretroviral activity. J. Virol. 87, 257–272 10.1128/JVI.01804-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel V., Sheetz M. (2006). Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 265–275 10.1038/nrm1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade R., Bohl J., Vande Pol S. (2002). Paxillin null embryonic stem cells are impaired in cell spreading and tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase. Oncogene 21, 96–107 10.1038/sj.onc.1205013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb D. J., Donais K., Whitmore L. A., Thomas S. M., Turner C. E., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. F. (2004). FAK-Src signalling through paxillin, ERK and MLCK regulates adhesion disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 154–161 10.1038/ncb1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthylake R. A., Lemoine S., Watson J. M., Burridge K. (2001). RhoA is required for monocyte tail retraction during transendothelial migration. J. Cell Biol. 154, 147–160 10.1083/jcb.200103048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R., Ballestrem C., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2003). Early molecular events in the assembly of matrix adhesions at the leading edge of migrating cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4605–4613 10.1242/jcs.00792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R., Itzkovitz S., Ma'ayan A., Iyengar R., Geiger B. (2007). Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 858–867 10.1038/ncb0807-858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.