Abstract

This investigation was designed to describe characteristics of closeness in the romantic relationships of early, mid-, and late adolescents, and to determine whether adolescent reports of relationship authority and reciprocity are linked to perceptions of interdependence, interaction frequency, activity diversity, influence, and relationship duration. Age was positively associated with interdependence, daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, and reciprocity but not with influence, authority, or relationship duration; gender was unrelated to all characteristics of closeness. Authority and reciprocity were each positively associated with relationship influence. Authority moderated associations between reciprocity and several characteristics of closeness such that reciprocity was positively linked to interdependence, daily social interaction, and weekly activity diversity, but only in relationships characterized by low levels of authority. Neither reciprocity nor authority was associated with relationship duration.

During childhood, close relationships tend to be limited to family members and friends, but during adolescence a new close relationship emerges: The romantic relationship. Closeness, is an important index of relationship quality has been studied extensively among adults, especially in the context of heterosexual relationships (see Clark and Reis, 1988, for review). Participants who perceive their relationship to be high in closeness report more satisfaction than those who perceive their relationship to be low in closeness (Aron, Aron, Smollan, 1992). Close relationships are also more stable and less likely to terminate than less close relationships (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989a). It is somewhat surprising, therefore, that little is known about closeness in romantic relationships during adolescence. The present study was designed to describe adolescent romantic relationships on several dimensions of closeness and to determine whether patterns of closeness vary across the adolescent years.

Closeness may be defined in terms of interdependence. Interdependence describes the degree to which participants in a relationship are interconnected. Scholars of adult close relationships have identified four objective properties of interdependence: The frequency, diversity, strength of influence, and duration of interconnections between participants (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989b). Frequency describes the amount of social interaction between participants. Diversity describes the extent to which participants engage in different types of social interchanges. Strength of influence describes the degree to which exchanges affect the participants. Duration describes the time period over which participants have maintained interconnections. In close relationships, participants engage in frequent social interaction, share a variety of different activities together, and shape one another’s thoughts and behaviors through exchanges that are maintained over time and across space. Developmental alterations in interdependence have been noted. Considerable evidence supports the notion that, with age, adolescents spend more time with agemates and less time with family members (Larson & Richards, 1991). Yet even as peer influence increases across adolescence, parents remain the more influential relationship (Berndt, 1999). Evidence suggests that patterns of interdependence in romantic relationships differ from those in parent-child and peer relationships: Across the adolescent years, the amount of social interaction and the number of different activities increases in romantic relationships, surpassing that with friends and parents during late adolescence(Laursen & Williams, 1997). Yet regardless of age, adolescents view the influence of romantic relationships as greater than that of friendships and equal to that of parent-child relationships.

Closeness also may be defined in terms of reciprocity and authority (Youniss, 1980). Reciprocal or horizontal relationships are characterized as relatively egalitarian affiliations, marked by mutuality and equitable interchanges. Authority or vertical relationships are characterized by unilateral power, marked by a lack of mutuality and an absence of equality. Perceived relationship reciprocity and authority vary with age. Across adolescence, authority declines and reciprocity increases in parent-child and friend relationships, but regardless of age, parents retain more authority than friends and friendships contain more reciprocity than parent-adolescent relationships (Hunter, 1984; Laursen, Wilder, Noack, & Williams, in press). Less is known about romantic relationships, but findings from one study suggest little change across adolescence in perceptions of relative power; adolescents of all ages rank romantic relationships as more similar to friendships than parent-child relationships in terms of perceived authority (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992).

The development of romantic relationships represents an important developmental milestone. Over the course of the adolescent years, closeness shifts from parent-child relationships to friendships to romantic relationships (Laursen & Bukowski, 1997). Because closeness is a many faceted attribute, changes in overall closeness may mask alterations in specific characteristics of closeness. Generally speaking, adolescent reports of overall closeness tend to anticipate the later development of a particular feature of closeness. Sometime during the middle adolescent years, a majority of youth view a romantic relationships as their closest relationship, but it is not until late adolescence that romantic relationships surpass friendships and mother-child relationships in affection, intimacy, companionship, and support (Laursen & Williams, 1997; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Thus, shifts in closeness gradually transform nascent romantic relationships into adult-like relationships, following a parallel developmental shift in social exchange orientation from self-centered goals to relationship-centered goals (Roscoe et al., 1987).

Other developmental changes mark romantic relationships during the adolescent age period. Compared to early adolescents, late adolescents are more apt to view romantic relationships as communal rather than exchange relationships (Laursen & Jensen-Campbell, 1999). In communal relationships, participants strive to fulfill the needs of the partner. In exchange relationships, participants strive to balance relationship costs and benefits. As is true of friendships, romantic relationships are a special type of communal relationship that takes place on an open-field, where participants are free to discontinue the relationship at any time. Unlike friendships, romantic relationships are gradually transformed by increasingly public vows of commitment, creating conditions akin to a closed-field. Nevertheless, romantic relationships are rarely considered completely closed relationships in contemporary Western culture, especially during adolescence, when participants are encouraged to experiment with closeness without making long-term commitments. Thus, adolescence offers opportunities to develop a greater awareness of the particulars of establishing and maintaining interdependent interconnections in romantic relationships.

Adolescence is also the period in which youth first experience authority and reciprocity in the context of a romantic relationship. In contemporary Western culture, participants in romantic relationships typically strive for equality between participants, but status differences often create an imbalance in power. Although related conceptually, mutually and authority appear to be quite distinct in practice. Research on adolescent romantic relationships reveals that most adolescent relationships are best described as egalitarian (Galliher et al., 1999), but at the same time adolescents report an unequal distribution of power between participants in these relationships (Felmlee, 1994). Thus, romantic partners perceive a clear distinction between reciprocity and authority. Early romantic relationships resemble friendships in that they are predicated on mutuality, but power in these relationships is often distributed unequally. In this regard, adolescent romantic relationships have a great deal in common with adult romantic relationships.

The present study was designed to address two specific questions: (1) Are there age differences in characteristics of closeness in adolescent romantic relationships? (2) Do patterns of interdependence differ as a function of reciprocity and authority? To this end, early, mid- and late adolescents completed instruments describing their romantic relationships in terms of several characteristics of closeness: interdependence, frequency of social interactions, diversity of social activities, strength of influence, and duration of relationship, as well as reciprocity and authority. Consistent with findings from previous studies (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Laursen & Williams, 1997), associations were anticipated between age and all characteristics of closeness except influence and authority. Associations between interdependence and reciprocity were expected to be stronger than those between interdependence and authority. No previous studies have examined interactions between reciprocity and authority in predicting interdependence, but it makes sense to assume that relationships that are low in both authority and reciprocity should be viewed as having the weakest interconnections.

Method

Participants

A total of 108 early (n = 48), mid- (n = 29), and late (n = 31) adolescents participated in the study. Early adolescents ranged in age from 12 to 14 (M = 12.9 years old); mid-adolescents ranged in age from 15 to 18 (M = 17.6 years old); late-adolescents ranged in age from 19 to 20 (M = 19.4 years old). Of this total, 70 were females and 38 were males. Early and mid- adolescents were recruited from public school in suburban and rural communities. Late adolescents were drawn from psychology classes in a large public university. Only adolescents currently involved in a romantic relationship participated in the study. The mean duration of these romantic relationships was 28.37 months (SD = 30.6 months; range = 1 to 162 months). Thirteen late adolescents reported living at least part time with their romantic partner. There were no statistically significant differences between those who lived together and those who did not on any variables except weekly activity diversity, which was greater for those who cohabited.

Instruments

Adolescents completed three instruments describing relationships with current romantic partners. The Inventory of Socializing Interactions (Hunter, 1984; Youniss & Smolar, 1985) consisted of two subscales. The first subscale, reciprocity, described perceptions of mutuality in the relationship (e.g., How often does your romantic partner do the following when he or she wants you to do something? Asks if you would be willing to do it.). The second subscale, authority, described perceptions of the distribution of power in the relationship (e.g., How often does your romantic partner do the following when he or she wants you to do something? Says you’re supposed to do what he or she tells you to do.). Each subscale contained 16 items that were rated on a 4-point scale. Item scores were summed (range: 4 to 64) to produce an overall index of reciprocity (alpha = .74) and authority (alpha = .67).

The Relationship Closeness Inventory (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989b) consisted of four subscales. The first subscale, daily social interaction, represented the amount of time participants were alone together in social interaction on a typical day during the previous week. Adolescents estimated the number of minutes of social interaction during the morning, afternoon, and evening (range: 0 to 600). The second subscale, weekly activity diversity, described the number of different activities that participants engaged in alone together during the previous week. Adolescents identified activities (e.g., Ate a meal.) from a 38-item checklist. The third subscale, influence, reflected the participant’s perception of the romantic partner’s influence over the participant’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Adolescents rated 34 items on a 7-point scale (e.g., My romantic partner influences how I spend my free time.). Item scores were summed to produce an overall index of influence (alpha = .82). The fourth subscale, duration of the relationship, described the duration of the romantic affiliation. Adolescents reported the total length of the romantic relationship in months (range: 0 to 60). Six original weekly activity diversity items and four original influence items were modified for use with adolescents (see Laursen & Williams, 1997, for details). The daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, and influence subscales were standardized on a scale ranging from 1 to 10 (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989). Interdependence represents the sum of these standardized scores.

Procedure

Participants completed the Inventory of Socializing Interactions and the Relationship Closeness Inventory during one-hour sessions in a quiet classroom setting. For all subjects under the age of 18, parental permission was a prerequisite for participation in the study. Participants were instructed to report on their closest, deepest, most involved, and most intimate romantic relationship. This person was referred to as a boyfriend or girlfriend.

Results

The results are divided into two parts. The first describes Pearson’s correlation r, which determined linear associations between variables. The second describes regression analyses that examined curvilinear associations and interactions between relationship reciprocity and authority in predicting interdependence, daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, influence, and duration of the relationship. Because preliminary analyses revealed neither main effects nor interactions involving gender, this variable was excluded from subsequent analyses. Despite moderate correlations between predictor variables, there was no evidence of colinearity in regression analyses: Condition indexes were all below 5.00 and there were no variables with two variance proportions greater than .50.

In the first set of analyses, correlations revealed statistically significant associations between all characteristics of closeness, with the following exceptions : Authority was not linked to daily social interaction, and duration of the relationship was not linked to any characteristic of closeness except daily social interaction (see Table 1). Participant age was associated will all characteristics of closeness except influence, authority, and duration of the relationship.

Table 1.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for predictor and outcome variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | Mean | (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Authority | --- | 21.11 | 6.6 | ||||||

| (2) Daily Social Interaction | .13 | --- | 234.12 | 225.6 | |||||

| (3) Duration of Relationship | −.10 | .22* | --- | 2.36 | 2.5 | ||||

| (4) Influence | .40*** | .27** | .12 | --- | 128.14 | 34.6 | |||

| (5) Interdependence | .33* | .81*** | .62*** | .17 | --- | 15.11 | 4.7 | ||

| (6) Participant Age | .13 | .25** | −.08 | .17 | .30** | --- | 16.04 | 2.9 | |

| (7) Reciprocity | .50*** | .24* | .01 | .46*** | .37** | .34** | --- | 39.93 | 8.1 |

| (8) Weekly Activity Diversity | .25** | .59*** | .07 | .36*** | .84*** | .33** | .31** | 11.41 | 6.9 |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In the second set of analyses, five separate multiple regression analyses were conducted. In each, participant age and relationship reciprocity and authority were the predictor variables. Interdependence, daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, influence, and duration of relationship were separately considered as outcome variables. In each, age, reciprocity, and authority were entered into the first step of the regression. To examine whether authority moderated the association between reciprocity and the outcome variable, the cross-product of reciprocity and authority was entered into the second step of the regression. All statistically significant interactions were interpreted according to post-hoc procedures described by Aiken and West (1991). For each statistically significant interaction, the association between reciprocity and the outcome variable was examined at three levels of authority: High (one standard deviation above the mean), medium (the mean), low (one standard deviation below the mean).

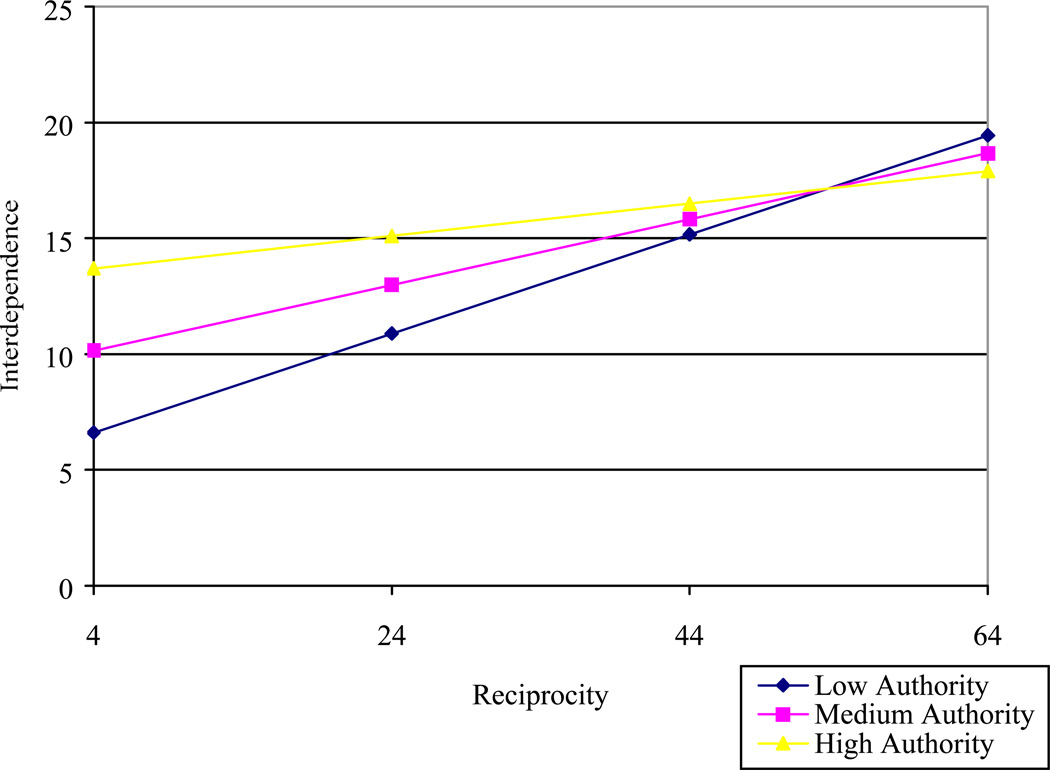

The first regression concerned interdependence (see Table 2). Results from the first step indicated that age, reciprocity, and authority were positively associated with interdependence. As age, reciprocity, and authority increased, interdependence increased. Results from the second step indicated that authority moderated the association between reciprocity and interdependence. At low levels of authority, there was an association between reciprocity and interdependence (β = .37, p < .001, see Figure 1). As reciprocity increased, interdependence increased. At medium and high levels of authority, there were no statistically significant associations between reciprocity and interdependence. There were no statistically significant interactions involving age. In sum, age was positively associated with interdependence, and reciprocity was positively linked to interdependence, but only in relationships with low levels of authority.

Table 2.

Regression analyses predicting interdependence, daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, influence, and duration of relationship from participant age and relationship reciprocity and authority

| Outcome | Step | Predictor | Beta | R2 Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interdependence | 1 | Age | .20** | .210*** |

| Reciprocity | .22** | |||

| Authority | .18* | |||

| 2 | Reciprocity × Authority | −.16 | .022* | |

| Minutes of Daily Social Interaction | 1 | Age | .20** | .092*** |

| Reciprocity | .11 | |||

| Authority | .04 | |||

| 2 | Reciprocity × Authority | −.18 | .031* | |

| Amount of Weekly Activity Diversity | 1 | Age | .26*** | .166*** |

| Reciprocity | .16 | |||

| Authority | .13 | |||

| 2 | Reciprocity × Authority | −.18 | .029* | |

| Influence | 1 | Age | .03 | .246* |

| Reciprocity | .34*** | |||

| Authority | .22** | |||

| 2 | Reciprocity × Authority | .12 | .015 | |

| Duration of Relationship | 1 | Age | −.10 | .022 |

| Reciprocity | .10 | |||

| Authority | −.13 | |||

| 2 | Reciprocity × Authority | .07 | .015 | |

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Reciprocity and interdependence at three levels of authority.

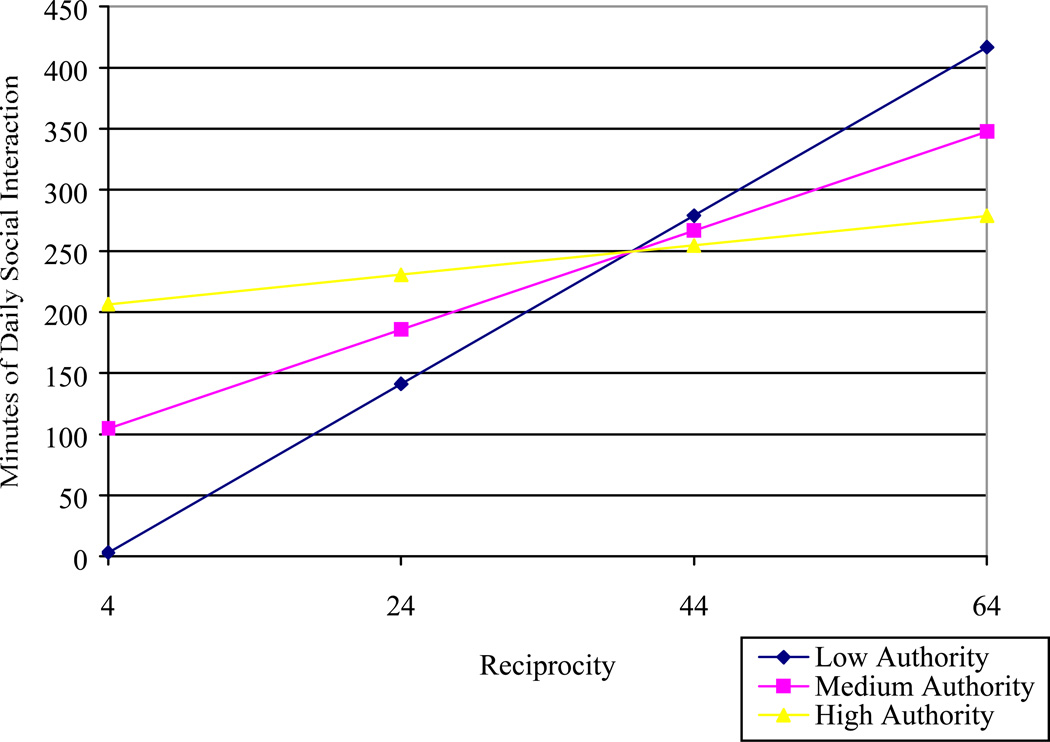

The second regression concerned daily social interaction (see Table 2). Results from the first step revealed that age was positively associated with daily social interaction. As age increased, so did daily social interaction. Results from the second step indicated that authority moderated the association between reciprocity and daily social interaction. At low levels of authority, there was an association between reciprocity and daily social interaction (β = .33, p < .005. see Figure 2). As reciprocity increased, daily social interaction increased. At medium and high levels of authority, there were no statistically significant associations between reciprocity and daily social interaction. There were no statistically significant interactions involving age. In sum, age was positively associated with daily social interaction, and reciprocity was positively linked to daily social interaction, but only in relationships with low levels of authority.

Figure 2.

Reciprocity and daily social interaction at three levels of authority.

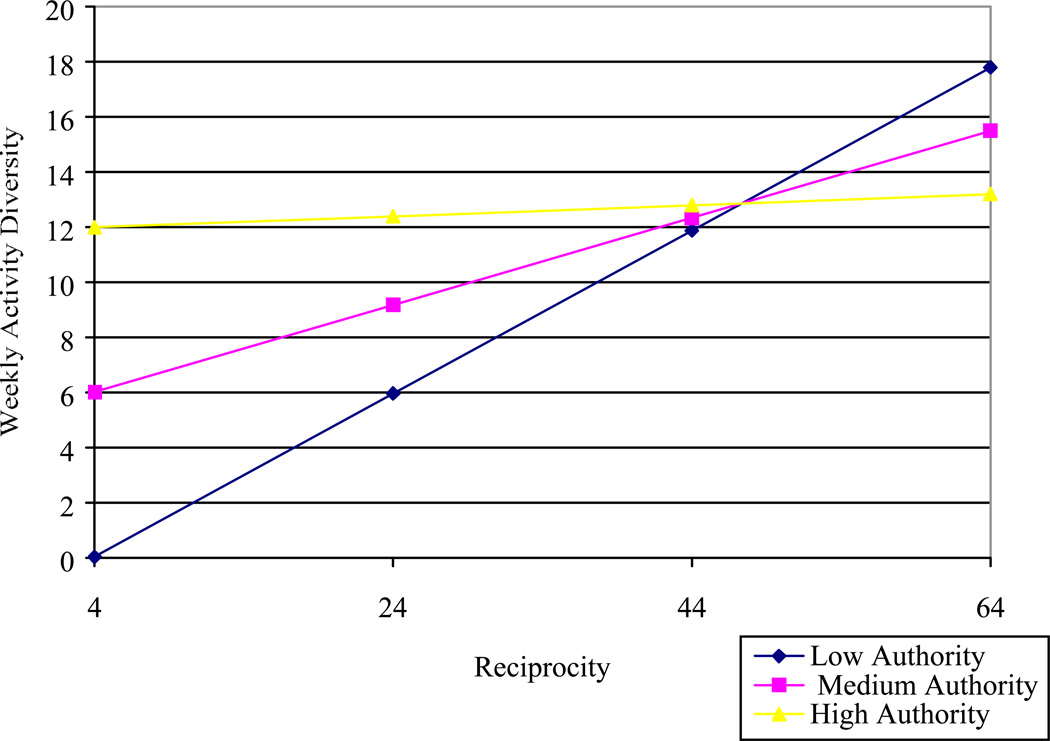

The third regression concerned weekly activity diversity (see Table 2). Results from the first step indicated that age was positively associated with weekly activity diversity. As age increased, so did weekly activity diversity. Results from the second step revealed that authority moderated the association between reciprocity and weekly activity diversity. At low levels of authority, there was an association between reciprocity and weekly activity diversity (β = .34, p < .004, see Figure 3). As reciprocity increased, weekly activity diversity increased. At medium and high levels of authority, there were no statistically significant associations between reciprocity and weekly activity diversity. There were no statistically significant interactions involving age. In sum, age was positively associated with weekly activity diversity, and reciprocity was positively linked to weekly activity diversity, but only in relationships with low levels of authority.

Figure 3.

Reciprocity and weekly activity diversity at three levels of authority.

The fourth regression concerned influence (see Table 2). Results from the first step indicated that reciprocity and authority were positively associated with influence. As reciprocity increased so did influence, and as authority increased so did influence. Results from the second step revealed that authority did not moderate the association between reciprocity and influence.

The fifth regression concerned duration of relationship (see Table 2). There were no statistically significant associations with duration of relationship on either step one or step two.

Discussion

Two questions concerning closeness in adolescent romantic relationships guided this investigation. The first addressed developmental differences in closeness within romantic relationships. Do characteristics of closeness in adolescent romantic relationships differ as a function of age? As expected, older adolescents reported more interdependence, daily social interaction, activity diversity, and reciprocity than younger adolescents. These developmental shifts replicate previous studies of age-related change in romantic relationship closeness (Laursen & Williams, 1997) and they provide a clear picture of the transformation of romantic relationships from affiliations that resemble adolescent friendships to affiliations that resemble adult heterosexual relationships. In contrast, relationship influence and authority did not vary as a function of age. From the outset, adolescents regard romantic relationships as one of their most significant and influential relationships, one predicated on sharing power. Because these fundamental relationship precepts do not vary with participant age, these may be considered preconditions to the establishment of a romantic relationship during adolescence.

The second question to be addressed concerned the extent to which reciprocity and authority, separately and jointly, predict interdependence. Do patterns of interdependence differ as a function of reciprocity and authority? As predicted, relationships with high levels of reciprocity were more influential and interdependent than those low in reciprocity. Similar positive associations with influence and interdependence emerged for authority. The findings for interdependence, however, were qualified by a two-way interaction between authority and reciprocity: Interdependence increased as a positive function of reciprocity only in relationships with low levels of authority. And although there were no main effects for authority and reciprocity in the prediction of social interaction and activity diversity, there was a two-way interaction: The amount of social interaction and the number of social activities increased as reciprocity increased, but only in relationships marked by low authority. In a recent study of early and mid-adolescents from Germany and the USA, friendship interdependence was linked to reciprocity and authority, such that close relationships reported more reciprocity and authority than less close relationships (Laursen et al., in press). Findings from the present inquiry underscore the importance of considering authority and reciprocity simultaneously in voluntary relationships. Despite being moderately intercorrelated, authority and reciprocity exert differing influences on interdependence. The present study reveals that at the highest levels of authority, there is virtually no change in interdependence (in particular, in daily social interaction and weekly activity diversity) as a function of reciprocity. High authority appears to suppress or override the influence of reciprocity. Under conditions of low authority, however, reciprocity has a dramatic impact on interdependence. When authority is low, greater levels of reciprocity tend to produce greater levels of daily social interaction and weekly activity diversity. Put another way, high authority relationships are closer than low authority relationships when reciprocity is low, but differences in closeness as a function of authority either disappear or are reversed when reciprocity is high.

Our comments are tempered by the recognition that these findings require replication with a larger, more diverse sample of adolescents. That said, we suggest that, at least among this group of youth, the meaning of reciprocity differs depending upon perceptions of how power is allocated to the self relative to the partner. Because the present study only assessed the extent to which exchange outcomes were viewed as balanced, it was impossible to determine whether the self or the partner was the recipient of favorable treatment if there was an imbalance of power or reciprocity. It makes sense to assume, however, that if reciprocity is low, the powerless are more apt to see themselves in a less favorable position than the powerful. Therefore it is not particularly surprising that romantic partners rarely spend time together when one participant views the power they hold and the benefits they receive as inferior to that of the partner. These are, after all, voluntary relationships, in which participants come and go as they please. But apparently feelings of powerlessness are overlooked when reciprocity is high and exchange outcomes are equitable. It also makes sense to assume that the more power one has in a relationship, the more exchange outcomes are likely to be perceived as equitable or advantageous. Under these circumstances, reciprocity has little bearing on closeness because the interconnections are, by definition, favorable.

One obvious explanation for these findings failed to receive empirical support: There were no main effects or interactions as a function of gender. Recent reviews of marital relationships conclude that marriages are best considered unequal partnerships (Steil, 2000), where men enjoy greater power than women. This appears not to be the case during adolescence, at least not among those who participated in our study. Two possibilities come to mind. First, cohort differences may be such that gender inequalities are disappearing as contemporary youth abandon the power differential that marked the romantic relationships of their elders. Such a change would be consistent with evidence that interconnections in romantic relationships are evolving rapidly in multiple arenas and across diverse contexts (Coates, 1999). Second, as commitment increases and the affiliation becomes less voluntary, romantic relationships may grow less egalitarian (Laursen, 1999). In other words, power may be shared during courtship but not during marriage, either because of changes in the relationship or because of changes in the issues over which power must be shared. (It is interesting to note that length of the relationship was unrelated to changes in relationship power or reciprocity, which would seem to rule out alterations during the courtship period.) In any event, it is clear that these findings may not be attributed to perceptions of greater power on the part of males or perceptions of greater reciprocity on the part of females.

There is accumulating evidence points that a host of factors contribute to individual differences in adolescent romantic affiliations. Participants bring differing backgrounds and experiences to the relationship which, in turn, manifest themselves in different types of romantic relationships. Some have argued that current relationships differ as a function of past relationship experience (Laursen & Bukowski, 1997). For instance, early attachment relationships with parents are thought to influence a generalized set of expectations about close relationships which have long-term consequences for feelings of attachment and security in later romantic relationships (Furman & Simon, 1999). Indirect influence mechanisms have been posited such that early attachment security shapes the capacity to form intimate relationships with peers (Collins & Sroufe, 1999). The absence of this capacity may have detrimental consequences on friendships, which are the foundation for later romantic relationships. These and other individual differences may promote different relationship styles such that some romantic affiliations are more apt to be predicated on intimacy and sharing than others (Shulman, Levy-Shiff, Kedem, & Alon, 1997). Findings from the present study suggests that power and reciprocity are more central to some relationships than to others, and that these variables interact so as to produce strikingly different patterns of interdependence.

This investigation is not without limitations. Because romantic relationships vary widely across settings and groups (Coates, 1999), the patterns of closeness identified herein may not generalize beyond these Anglo American youth. Furthermore, the data were all the product of reports from a single member of the dyad. As is true of other close relationships, romantic partners have widely divergent views of their interconnections (Berscheid et al., 1989b), so it is not clear that these subjective patterns of closeness are either shared or accurate. Objective assessments of relationship closeness that supplement participant reports will help to determine the amount of variance contributed by reporter bias. Finally, we operationalized closeness in the present study in terms of a small number of specific variables. Relationships and their representations may be described along many different dimensions, and doing so would undoubtedly produce a more complex and nuanced view of adolescent romantic relationships.

In closing, the present study represents a modest effort to fill the void in our understanding of closeness in romantic relationships. Overall, age was positively associated with interdependence, daily social interaction, weekly activity diversity, and reciprocity, but not influence, authority or relationship duration. With increasing autonomy, adolescents expand interconnections in romantic relationships such that they eventually become commensurate with their perceived importance. Regardless of age, authority and reciprocity directly predicted relationship influence, and authority moderated associations between reciprocity and interdependence, daily social interaction, and weekly activity diversity. These findings suggest at least three distinct relationship types: A moderate closeness relationship in which authority prevails and reciprocity is unimportant, a high closeness relationship in which authority is low and reciprocity is high, and a low closeness relationship in which there is little authority and little reciprocity.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants from the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R29 HD33006) and the Johann Jacobs Foundation.

Contributor Information

Ryan E. Adams, Florida Atlantic University

Brett Laursen, Florida Atlantic University.

David Wilder, University of the Pacific.

References

- Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psycology. 1992;63:596–612. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Snyder M, Omoto AM. Issues in studying close relationships: Conceptualizing and measuring closeness. In: Hendrick C, editor. Review of personality and social psychology: Vol. 10. Close relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1989a. pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Snyder M, Omoto AM. The Relationship Closeness Inventory: Assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989b;57:792–807. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Vol. 30. Relationships as developmental contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. Friends’ influence on children’s adjustment to school; pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58:1101–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Reis HT. Interpersonal processes in close relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 1988;39:609–672. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.003141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates DL. The cultured and culturing aspects of romantic experience in adolescence. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 330–363. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee DH. Who’s on top? Power in romantic relationships. Sex Roles. 1994;31:275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA. Cognitive representations of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Rostosky SS, Welsh DP, Kawaguchi MC. Power and psychological well-being in late adolescent romantic relationships. Sex Roles. 1999;40:689–716. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter FT. Socializing procedures in parent-child and friendship relations during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1092–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Berscheid E, Christensen A, Harvey JH, Huston TL, Levinger G, McClintock E, Peplau LA, Peterson DR. Close Relationships. New York: Freeman; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development. 1991;62:284–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B. Closeness and conflict in adolescent peer relationships: Interdependence with friends and romantic partners. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 186–210. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Bukowski WM. A developmental guide to the organization of close relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:747–770. doi: 10.1080/016502597384659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Jensen-Campbell LA. The nature and function of social exchange in adolescent romantic relationships. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 50–74. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Wilder D, Noack P, Williams V. Adolescent perceptions of reciprocity, authority and closeness in relationships with mothers, fathers and friends. International Journal of Behavioral Development. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Williams V. Perceptions of interdependence and closeness in family and peer relationships among adolescents with and without romantic partners. In: Shulman S, Collins WA, editors. New Directions for Child Development: No. 78. Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1997. pp. 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Levy-Shiff R, Kedem P, Alon E. Intimate relationships among adolescent romantic partners and same-sex friends: Individual and systemic perspectives. In: Shulman S, Collins WA, editors. Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives. New Directions for Child Development (No. 78) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil JM. Contemporary marriage: Still an unequal partnership. In: Hendrick C, Hendrick SS, editors. Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J. Parents and peers in social development: A Sullivan-Piaget perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J, Smollar J. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]