Abstract

The combination of a high-affinity antibody to a hapten, and hapten-conjugated compounds, can provide an alternative to the direct chemical cross-linking of the antibody and compounds. An optimal hapten for in vitro use is one that is absent in biological systems. For in vivo applications, additional characteristics such as pharmacological safety and physiological inertness would be beneficial. Additionally, methods for cross-linking the hapten to various chemical compounds should be available. Cotinine, a major metabolite of nicotine, is considered advantageous in these aspects. A high-affinity anti-cotinine recombinant antibody has recently become available, and can be converted into various formats, including a bispecific antibody. The bispecific anti-cotinine antibody was successfully applied to immunoblot, enzyme immunoassay, immunoaffinity purification, and pre-targeted in vivo radioimmunoimaging. The anti-cotinine IgG molecule could be complexed with aptamers to form a novel affinity unit, and extended the in vivo half-life of aptamers, opening up the possibility of applying the same strategy to therapeutic peptides and chemical compounds. [BMB Reports 2014; 47(3): 130-134]

Keywords: Affinity unit, Antibody, Cotinine, Hapten

LINKING ANTIBODIES TO CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS

Antibodies have been conjugated to chemical compounds for various purposes. Antibodies conjugated to enzymes are widely used in enzyme immunoassays or immunoblot analysis. Fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies have applications in flow cytometric analysis, fluorescence immunoassays, and fluorescence microscopy. For immunoaffinity purification, antibody-conjugated gels or magnetic beads are commonly used. Antibodies have also been conjugated to radioisotopes for use in radioimmunoassays, radioimmunoimaging, and radioimmunotherapy. For clinical use, technetium (99mTc)-labeled anti-CEA antibody (arcitumomab) is available for the detection of CEA-expressing tumors (CEA-scan) (1). Radiolabeled anti-CD20 antibodies are used for the treatment of CD-20-expressing lymphoma and leukemia (2,3). Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have recently become available for the treatment of cancers. Two ADCs, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1, Kadcyla) (4,5) and brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) (6), have been approved for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive metastatic and recurrent breast cancer and lymphoma, respectively.

The hurdle in antibody conjugation lies in the non-selective nature of the conjugation site. Frequently, residues that are critical for antigen binding are involved in cross-linking; therefore, the antibody shows reduced affinity after cross-linking. Furthermore, in the case of ADC, the heterogeneous distribution of the drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) makes both process development and pharmacokinetic profiling enormously difficult. Several measures have been developed to overcome this hurdle. Replacing residues with cysteine, and using this as a reactive handle, provided a homogenous and functional ADC (7,8). An artificial amino acid p-acetylphenylalanine (pAcPhe) was incorporated in a site-directed manner into recombinant antibodies using an engineered orthogonal amber suppressor tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pair, and was selectively coupled to an alkoxyamine derivate (9,10). Selenocysteine, the 21st natural amino acid, has a nucleophilic selenol group with a low pKa (5.2); this was incorporated into a monoclonal antibody and selective conjugation was successfully achieved using this amino acid as a chemical handle (11). Chemoenzymatic approaches are under active development. Formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE), which recognizes a CXPCR sequence and converts a cysteine to formylglycine, has been explored to produce antibodies with aldehyde tags and generate bio-orthogonal reactive groups for selective conjugation (12). Chemically programmable antibodies were introduced to attach the chemical moiety specifically to the antigen-binding site (13). When combined with peptides or chemicals with affinity to a specific target molecule, this entity can serve as a unique affinity unit primarily extending the in vivo half-life of peptides or chemicals.

Due to the rapid development of antibody engineering technology, it is now possible to generate an antibody with a koff constant in the range of 1 × 10-5 to 1 × 10-6 s-1. With these values for the koff constant, the half-life of the antibody-antigen complex varies from 19 h to more than a week (Table 1) (14). Considering that the half-life of the thioester bond linking the antibody and the drug in T-DM1 is around 3.5 days (15), an anti-hapten antibody with this optimal koff constant and a hapten conjugate can facilitate the linkage of the antibody to the chemical compounds for a sufficiently long period (16).

Table 1.

Koff and calculated half-life (t1/2)

| koff (s-1) | t1/2 (hrs) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1 × 10E-3 | 0.193 |

| 1 × 10E-4 | 1.925 |

| 1 × 10E-5 | 19.25 |

| 1 × 10E-6 | 192.5 |

COTININE AS AN IDEAL HAPTEN TO LINK THE ANTIBODY AND CHEMICAL MOIETY

The combination of a high-affinity antibody to a hapten, and hapten-conjugated compounds, can provide an alternative to the direct chemical cross-linking of the antibody and the compounds. An optimal hapten for in vitro use should be absent from biological systems. Additional characteristics such as pharmacological safety and physiological inertness would be beneficial for in vivo use. Additionally, versatile cross-linking to various chemical compounds is favored. Classically, histamine-succinyl-glycine (HSG), diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA), and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) have been used as haptens in vivo (17-19).

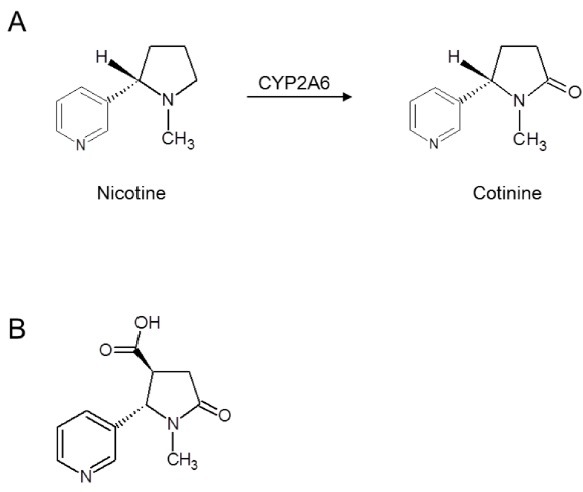

Recently, we introduced cotinine as an ideal hapten. It is a small chemical with a molecular weight of 176.22, and is a major metabolite of nicotine (Fig. 1A). Commonly used as a biomarker for smoking exposure, cotinine is absent in human or animal tissues (20). Cotinine is highly non-toxic, with an LD50 of 4 ± 0.1 g/kg in mice (21). No deleterious side effects were induced in humans treated with daily doses of cotinine up to 1,800 mg for 4 consecutive days. Recently, mild beneficial psychopharmacological effects of cotinine have been reported and the potential therapeutic use of cotinine in Alzheimer’s disease or post-traumatic stress disorder is under discussion (22). Carboxycotinine (trans-4-cotininecarboxylic acid, Fig. 1B) is commercially available at a reasonable cost; this carboxyl group can be conveniently employed for chemical crosslinking. While some immunogenicity is reported for DTPA and DOTA (23-26), no immune response to cotinine has been reported.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of cotinine. (A) Nicotine is converted to cotinine by cytochrome p450 2A6 (CYP2A6) in human. (B) Structure of carboxycotinine (trans-4-cotininecarboxylic acid).

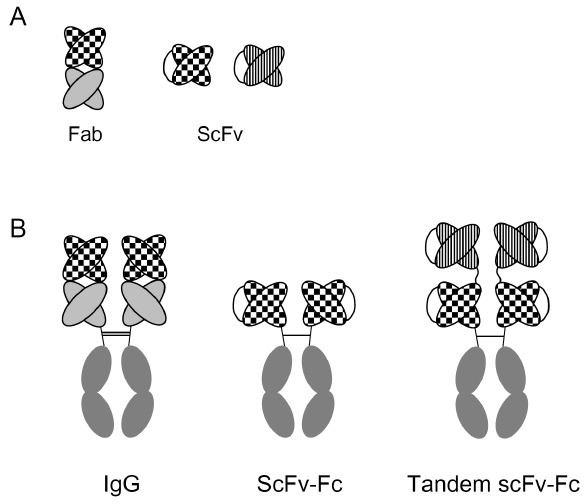

A high-affinity anti-cotinine antibody was originally generated by our group to develop a super-sensitive enzyme immunoassay for the detection of second-hand smoking exposure (27). The antibody has kon, koff, and KD values of 2.6 × 106 M-1ㆍs-1, 1.3 × 10-5 s-1 and 4.9 × 10-12 M, respectively (28). This antibody binds specifically to cotinine and does not cross-react with chemicals with similar structures, such as nicotinine, anabasine, caffeine, or cholesterol. Using this antibody, an enzyme immunoassay was developed which can determine cotinine concentrations in the range of 1 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml, comparable to the serum concentrations seen in passive smokers. Furthermore, cotinine levels measured in human volunteers using this antibody exactly corresponded with smoking behavior and showed better correlation than those obtained using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS) in a split assay. This antibody was confirmed to retain its reactivity even when expressed in various formats other than as a conventional IgG molecule (Fig. 2) (29,30).

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of various antibody formats employed in biological assays and immunotherapy. (A) Antigen-binding units. (B) Antigen-binding units combined with Fc.

IN VITRO USE OF COTININE/ANTI-COTININE ANTIBODY COMPLEX

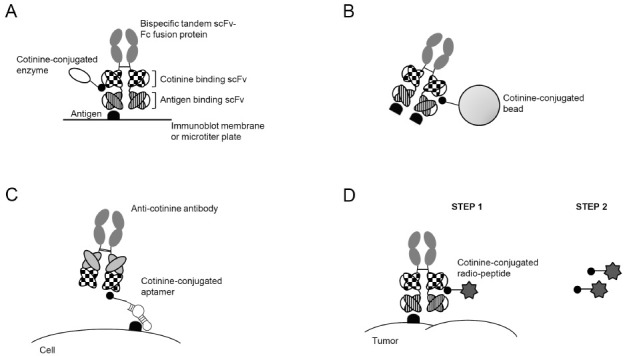

The cotinine/anti-cotinine antibody complex provides an effective platform for immunodetection (Fig. 3A) and immunopurification (Fig. 3B) (30). Immunoblot analysis using serum, anti-human complement C5- and cotinine-bispecific tandem scFv-Fc antibody, and cotinine-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) showed a clear signal without the significant background observed in a parallel experiment using a classical secondary antibody, which reacts with the Fc region of immunoglobulins. Cotinine-conjugated magnetic beads complexed with the bispecific antibody specifically immunoprecipitated complement C5 from serum, whereas conventional immunoprecipitation using protein A beads resulted in the co-precipitation of human immunoglobulin. The bispecific antibody and cotinine-conjugated HRP were successfully employed in an enzyme immunoassay. All these optimal results are possible because cotinine is absent in the biological system and does not react significantly to any biological molecules, which is advantageous over the commonly used biotin-streptavidin system.

Fig. 3. Applications of anti-cotinine antibody. Bispecific antibody was used for immunodetection (A) and immunoprecipitation (B). Anti-cotinine antibody detected a cotinine-conjugated aptamer, which bound a cell-surface antigen (C). The complex of bispecific antibody and cotinine-conjugated radiopeptide was localized to a tumor (D). Parts of this figure have been copied and modified with permission (30).

COTININE-CONJUGATED APTAMER AND THE ANTI-COTININE ANTIBODY COMPLEX AS A NOVEL AFFINITY UNIT

Over the last decade, aptamers specific to various target molecules have been developed. For use in biological experiments, aptamers have been conjugated to chemical compounds such as enzymes, biotin, or digoxin. For in vivo use, aptamers have to be cross-linked to polyethyleneglycol in order to extend their short half-lives (31). It was also reported that a vascular endothelial growth factor-neutralizing aptamer conjugated to a chemically programmable antibody retained both its reactivity and functionality (32). This observation raised the possibility that complexing with an antibody could extend the in vivo half-life of the aptamer. Recently, a cotinine-conjugated aptamer/anti-cotinine antibody complex has been successfully applied to various biological assays such as flow cytometry, immunoblot, immunoprecipitation, and enzyme immunoassay, using AS1411 and pegaptanib as examples (33) (Fig. 3C). Our group is actively testing whether the anti-cotinine antibody could extend the in vivo half-life of aptamers and potentiate their efficacy.

COTININE-CONJUGATED PEPTIDE/ANTI-COTININE ANTIBODY COMPLEX FOR PRE-TARGETED RADIOIMMUNOIMAGING

Pre-targeted radioimmunotherapy (PRIT) technology was developed to reduce the non-specific irradiation of normal tissues and organs originating from the non-specific accumulation of a radiolabeled antibody (34). For PRIT, a bispecific antibody reactive to both the target molecule and a hapten is first injected into the individual. Subsequently, after the antibody has been cleared out of the normal tissue and optimal accumulation in tumor tissue has been achieved, the radiolabeled hapten is injected. The unbound radiolabeled hapten is rapidly cleared from the systemic circulation. HSG, DTPA, and DOTA have been used as haptens for PRIT (35-37). Recently, the cotinine/anti-cotinine antibody complex was applied to pre-targeted radioimmunoimaging (Fig. 3D) (29). In this study, a complex of cotinine dipeptide labeled with 131I, and anti-HER2- and cotinine-bispecific tandem scFv-Fc antibody, was successfully directed to HER2-positive breast cancer in a mouse xenograft model, as seen in single photon emission computed tomography images. The radiosignal was specifically enhanced at the tumor site when 131I-labeled cotinine dipeptide was re-injected with a time-delay. Our group is testing various forms of bispecific antibodies to determine the most efficient one for the specific delivery of radiolabeled hapten. Furthermore, the optimal peptide sequence for labeling is under active investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (2011-0030119). This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2009-0093820).

References

- 1.Ghesani M., Belgraier A., Hasni S. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) scan in the diagnosis of recurrent colorectal carcinoma in a patient with increasing CEA levels and inconclusive computed tomographic findings. Clin. Nucl. Med. (2003);28:608–609. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200307000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capizzi R. L. Targeted radio-immunotherapy with Bexxar produces durable remissions in patients with late stage low grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. (2004);115:255–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain N., Wierda W., Ferrajoli A., Wong F., Lerner S., Keating M., O S. A phase 2 study of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. (2009);115:4533–4539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krop I. E., Beeram M., Modi S., Jones S. F., Holden S. N., Yu W., Girish S., Tibbitts J., Yi J. H., Sliwkowski M. X., Jacobson F., Lutzker S. G., Burris H. A. Phase I study of trastuzumab-DM1, an HER2 antibody-drug conjugate, given every 3 weeks to patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. (2010);28:2698–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis Phillips G. D., Li G., Dugger D. L., Crocker L. M., Parsons K. L., Mai E., Blattler W. A., Lambert J. M., Chari R. V., Lutz R. J., Wong W. L., Jacobson F. S., Koeppen H., Schwall R. H., Kenkare-Mitra S. R., Spencer S. D., Sliwkowski M. X. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. (2008);68:9280–9290. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng C., Pan B., O O. A. Brentuximab vedotin. Clin. Cancer Res. (2013);19:22–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakankar A. A., Feeney M. B., Rivera J., Chen Y., Kim M., Sharma V. K., Wang Y. J. Physicochemical stability of the antibody-drug conjugate Trastuzumab-DM1: changes due to modification and conjugation processes. Bioconjug. Chem. (2010);21:1588–1595. doi: 10.1021/bc900434c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junutula J. R., Raab H., Clark S., Bhakta S., Leipold D. D., Weir S., Chen Y., Simpson M., Tsai S. P., Dennis M. S., Lu Y., Meng Y. G., Ng C., Yang J., Lee C. C., Duenas E., Gorrell J., Katta V., Kim A., McDorman K., Flagella K., Venook R., Ross S., Spencer S. D., Lee Wong W., Lowman H. B., Vandlen R., Sliwkowski M. X., Scheller R. H., Polakis P., Mallet W. Site-specific conjugation of a cytotoxic drug to an antibody improves the therapeutic index. Nat. Biotechnol. (2008);26:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Axup J. Y., Bajjuri K. M., Ritland M., Hutchins B. M., Kim C. H., Kazane S. A., Halder R., Forsyth J. S., Santidrian A. F., Stafin K., Lu Y. C., Tran H., Seller A. J., Biroce S. L., Szydlik A., Pinkstaff J. K., Tian F., Sinha S. C., Felding-Habermann B., Smider V. V., Schultz P. G. Synthesis of site-specific antibody-drug conjugates using unnatural amino acids. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. (2012);109:16101–16106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211023109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirksen A., Hackeng T. M., Dawson P. E. Nucleophilic catalysis of oxime ligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. (2006);45:7581–7584. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X., Yang J., Rader C. Antibody conjugation via one and two C-terminal selenocysteines. Methods. (2013);65:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabuka D., Rush J. S., deHart G. W., Wu P., Bertozzi C. R. Site-specific chemical protein conjugation using genetically encoded aldehyde tags. Nat. Protoc. (2012);7:1052–1067. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popkov M., Gonzalez B., Sinha S. C., Barbas C. F. Instant immunity through chemically programmable vaccination and covalent self-assembly. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. (2009);106:4378–4383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900147106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakubowski H. Understanding biochemical dissociation constants: A temporal perspective. J. Chem. Educ. (2002);79:968–971. doi: 10.1021/ed079p968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krop I. E., Beeram M., Modi S., Jones S. F., Holden S. N., Yu W., Girish S., Tibbitts J., Yi J. H., Sliwkowski M. X., Jacobson F., Lutzker S. G., Burris H. A. Phase I Study of Trastuzumab-DM1, an HER2 Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Given Every 3 Weeks to Patients With HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. (2010);28:2698–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontermann R. E. Dual targeting strategies with bispecific antibodies. mAbs. (2012);4:182–197. doi: 10.4161/mabs.4.2.19000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi E. A., Goldenberg D. M., Cardillo T. M., McBride W. J., Sharkey R. M., Chang C. H. Stably tethered multifunctional structures of defined composition made by the dock and lock method for use in cancer targeting. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. (2006);103:6841–6846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600982103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldenberg D. M., Rossi E. A., Sharkey R. M., McBride W. J., Chang C. H. Multifunctional antibodies by the dock-and-lock method for improved cancer Imaging and therapy by pretargeting. J. Nucl. Med. (2008);49:158–163. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang C. H., Rossi E. A., Goldenberg D. M. The dock and lock method: A novel platform technology for building multivalent, multifunctional structures of defined composition with retained bioactivity. Clin. Cancer Res. (2007);13:5586s–5591s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim I., Huestis M. A. A validated method for the determination of nicotine, cotinine, trans-3'-hydroxycotinine, and norcotinine in human plasma using solid- phase extraction and liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. (2006);41:815–821. doi: 10.1002/jms.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riah O., Dousset J. C., Courriere P., Stigliani J. L., Baziard-Mouysset G., Belahsen Y. Evidence that nicotine acetylcholine receptors are not the main targets of cotinine toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. (1999);109:21–29. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4274(99)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran V. E. Cotinine : Beyond the expected, more than a biomarker of tobacco consumption. Front. Pharmacol. (2012);3:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe N., Goodwin D. A., Meares C. F., Mctigue M., Chaovapong W., Ransone C. M., Renn O. Immunogenicity in Rabbits and Mice of an Antibody-Chelate Conjugate - Comparison of (S) and (R) Macrocyclic Enantiomers and an Acyclic Chelating Agent. Cancer Res. (1994);54:1049–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosmas C., Maraveyas A., Gooden C. S., Snook D., Epenetos A. A. Anti-Chelate antibodies after intraperitoneal yttrium-90-labeled monoclonal-antibody immunoconjugates for ovarian-cancer therapy. J. Nucl. Med. (1995);36:746–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosmas C., Snook D., Gooden C. S., Courtenayluck N. S., Mccall M. J., Meares C. F., Epenetos A. A. Development of humoral immune-responses against a macrocyclic chelating agent (Dota) in cancer-patients receiving radioimmunoconjugates for imaging and therapy. Cancer Res. (1992);52:904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baxter A. B., Melnikoff S., Stites D. P., Brasch R. C. Immunogenicity of gadolinium-based contrast agents for magnetic-resonance-imaging - induction and characterization of antibodies in animals. Invest. Radiol. (1991);26:1035–1040. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S., Lee D. H., Park J. G., Lee Y. T., Chung J. A sensitive enzyme immunoassay for measuring cotinine in passive smokers. Clin. Chim. Acta. (2010);411:1238–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S. Development of anti-cotinine antibody and its application to EIA and carrier for cotinine-conjugated molecule. Seoul National University; (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon S., Kim Y.-H., Kang S. H., Kim S.-K., Lee H. K., Kim H., Chung J., Kim I.-H. Bispecific Her2 × cotinine antibody in combination with cotinine-(histidine) 2-iodine for the pre-targeting of Her2-positive breast cancer xenografts. J. Cancer Res. Clin. (2013);140:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H., Park S., Lee H. K., Chung J. Application of bispecific antibody against antigen and hapten for immunodetection and immunopurification. Exp. Mol. Med. (2013);45:e43. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apte R. S. Pegaptanib sodium for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Expert. Opin. Pharmaco. (2008);9:499–508. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuellner U., Gavrilyuk J. I., Barbas C. F. Expanding the Concept of Chemically Programmable Antibodies to RNA Aptamers: Chemically Programmed Biotherapeutics. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. (2010);49:5934–5937. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S., Hwang D., Chung J. Cotinine-conjugated aptamer/anti-cotinine antibody complexes as a novel affinity unit for use in biological assays. Exp. Mol. Med. (2012);44:554–561. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.9.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharkey R. M., Chang C. H., Rossi E. A., McBride W. J., Goldenberg D. M. Pretargeting: taking an alternate route for localizing radionuclides. Tumor Biol. (2012);33:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharkey R. M., Rossi E. A., McBride W. J., Chang C. H., Goldenberg D. M. Recombinant bispecific monoclonal antibodies prepared by the dock-and-lock strategy for pretargeted radioimmunotherapy. Semin. Nucl. Med. (2010);40:190–203. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharkey R. M., Karacay H., Chang C. H., McBride W. J., Horak I. D., Goldenberg D. M. Improved therapy of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma xenografts using radionuclides pretargeted with a new anti-CD20 bispecific antibody. Leukemia. (2005);19:1064–1069. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karacay H., Brard P. Y., Sharkey R. M., Chang C. H., Rossi E. A., McBride W., Ragland D. R., Horak I. D., Goldenberg D. M. Therapeutic advantage of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy using a recombinant bispecific antibody in a human colon cancer xenograft. Clin. Cancer Res. (2005);11:7879–7885. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]