Abstract

Purpose

To better understand and overcome difficulties with recruitment of adolescents with type 2 diabetes into clinical trials at three United States institutions, we reviewed recruitment and retention strategies in clinical trials of youth with various chronic conditions. We explored whether similar strategies might be applicable to pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

We compiled data on recruitment and retention of adolescents with type 2 diabetes at three centers (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC) from January 2009 to December 2011. We also conducted a thorough literature review on recruitment and retention in adolescents with chronic health conditions.

Results

The number of recruited patients was inadequate for timely completion of ongoing trials. Our review of recruitment strategies in adolescents included monetary and material incentives, technology-based advertising, word-of-mouth referral, and continuous patient–research team contact. Cellular or Internet technology appeared promising in improving participation among youths in studies of various chronic conditions and social behaviors.

Conclusions

Adolescents with type 2 diabetes are particularly difficult to engage in clinical trials. Monetary incentives and use of technology do not represent “magic bullets,” but may presently be the most effective tools. Future studies should be conducted to explore motivation in this population. We speculate that (1) recruitment into interventional trials that address the main concerns of the affected youth (e.g., weight loss, body image, and stress management) combined with less tangible outcomes (e.g., blood glucose control) may be more successful; and (2) study participation and retention may be improved by accommodating patients’ and caregivers’ schedules, by scheduling study visits before and after working hours, and in more convenient locations than in medical facilities.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, Pediatric, Adolescents, Youth, Young adults, Recruitment, Retention, Clinical trials

Over the past 3 decades, type 2 diabetes has become increasingly prevalent in children. Yet, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments of youths (<18 years of age) are metformin and insulin. Furthermore, lifestyle changes and combination therapy of metformin with rosiglitazone have shown little improvement beyond standard therapy, as recently demonstrated by the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial, a large multicenter study evaluating the effectiveness of three different treatment arms (lifestyle, metformin alone, and metformin with rosiglitazone) for blood glucose control [1,2]. Thus, more studies are needed but are hampered by the difficulty of recruiting children with type 2 diabetes. Current recruitment methods have not been effective in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes or at risk for it [1–4]. Here, we report the collective experience of three large United States (U.S.) medical centers and discuss various recruitment strategies in clinical trials enrolling adolescents and young adults.

Reasons for slow recruitment of youths with type 2 diabetes are manifold, including the perception of invulnerability [5], few clinical symptoms except at diagnosis, and time restraints because of school, part-time jobs, and other responsibilities [4]. The recruitment of minority youths, specifically those from low-income backgrounds, is especially challenging because traditional recruitment strategies may not work for these individuals [6–8].

Further reasons for slow recruitment come to light when comparing pediatric type 2 diabetes and type 1 diabetes. Children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes have participated in clinical trials without comparable difficulties for the past 70 years [9]. However, their socioeconomic status is generally higher [10–12], parental involvement is greater, and in case of noncompliance with insulin treatment, symptoms occur rapidly.

In comparison, patients with type 2 diabetes often belong to less affluent socioeconomic strata [13]. Racial demographics differ markedly; predominantly African-American and Hispanic adolescents develop type 2 diabetes, many of whom struggle with poverty and little or no access to health care [10–12,14]. Adults from these families often have type 2 diabetes as well, and may not have the means, time, or education to obtain adequate care. In addition, patients with type 1 diabetes may more easily recognize benefits from participation in clinical trials (e.g., prevention of hypoglycemia, lowering of insulin doses), whereas adolescents with type 2 diabetes, who frequently identify obesity rather than diabetes as their most important health issue, may perceive negative effects from clinical interventions (e.g., weight gain due to insulin treatment).

Traditional recruitment strategies in adolescents typically entail advertising with colorful, eye-catching flyers and letters to potential participants, their parents, and their physicians. Although such initiatives spark some initial interest they are usually insufficient to lead to effective recruitment [3,4,15–21]. Thus, more patient-friendly approaches are needed. For example, the Oklahoma site of the TODAY trial provided transportation and home visits for follow-up appointments. Similarly, the Teen–Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study achieved sustained patient retention with in-home follow-up visits for patients unable to attend clinic appointments [22,23]. Here, we further explore potential approaches to improve recruitment and retention of youth with type 2 diabetes, by reviewing our experience at three U.S. sites and the published literature on adolescent recruitment.

Methods

We compiled data on new diagnoses of type 2 diabetes, the number of outpatient visits, and recruitment and retention results from three centers (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC) from January 2009 to December 2011. The latter two centers function as primary care facilities, whereas NIH is a referral-based clinical research facility.

We also reviewed strategies for recruitment and retention used in adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions by conducting a literature search in PubMed and EMBASE from the year 2000 to present. Search terms included: type 2 diabetes, diabetes mellitus, diabetes, recruitment, retention, strategies, clinical trials, adolescence, adolescents, pediatric, and youth. To be considered studies had to (1) be published in the English language in a peer-reviewed journal after 2000; (2) include subjects 12–25 years of age; (3) address recruitment and retention strategies in clinical trials of adolescents and young adults with chronic illnesses and/or high-risk social and health behaviors; and (4) contain original data. From this original pool, we selected those potentially applicable to type 2 diabetes based on our experience. We paid particular attention to strategies that were unique and innovative, and promised to appeal to the interests of the target group.

From each article we extracted information on authors, study location and duration, intervention, demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and diagnosis), site of recruitment, and number of patients recruited and retained.

Results

Recruitment of youth with type 2 diabetes at three United States sites

Between January 2009 and December 2011, over 400 new diagnoses of type 2 diabetes in young individuals were recorded at the National Children’s Hospital in Washington, DC, and Texas Children’s Hospital (Baylor College of Medicine) in Houston, Texas; of these 400 patients, fewer than 60 were recruited into various clinical trials (Table 1). The NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, depends on patients referred or self-referred for participation in clinical research protocols. Over the 2-year observation period,11 new patients were recruited and enrolled, of whom two participated in two type 2 diabetes related trials (Short-Term Beta Cell Rest [NCT00445627] and Partners for Better Health: The Buddy Study [NCT NCT01007266]).

Table 1.

Recruitment numbers for pediatric type 2 diabetes at three clinical research centers

| Center name | New T2DM diagnoses (<25 Years of age) per year, n | Outpatient T2DM clinic visits per year, n | Title of clinical research study | Study start date | Patients needed to complete study, n | Patients recruited since start, n | Patients lost to follow-up, n | Recruitment goal met, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s National Medical Center (Washington, DC) | 42 (2009) 83 (2010) 92 (2011) |

315 (2009) 397 (2010) 306 (2011) |

Partners for Better Health in Adolescent Type 2 Diabetes: The Buddy Study | 2009 | 60 | 10 | 4 | 6.7 |

| National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland) | N/A | N/A | Effect of Short-Term Beta Cell Rest in Adolescents and Young Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 2007 | 75 | 11 | 5 | 14.7 |

| Partners for Better Health in Adolescent Type 2 Diabetes: The Buddy Study | 2009 | 60 | 2 | 0 | 3.3 | |||

| Texas Children’s HospitaleBaylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas) | 65 (2009) 74 (2010) 54 (2011) |

609 (2009) 610 (2010) 595 (2011) |

The Role of Amylin and Incretins on Postprandial Metabolisms in Adolescents With T2DM | 2005 | 20 | 13 | 1 | 65.0 |

| The Effect of Byetta and Symlin on Post-meal Meal Blood Sugar Levels in Children With T2DM | 2009 | 16 | 10 | 1 | 62.5 | |||

| Colesevelam Pediatric T2DM Study (WELKid DM) | 2010 | 200 | 7 | 1 | 3.5 | |||

| Glucose Production and Gluconeogenesis in Children With T2DM | 2011 | 28 | 7 | 1 | 25.0 |

N/A = not applicable; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Applicable recruitment strategies (incentives and advertisement)

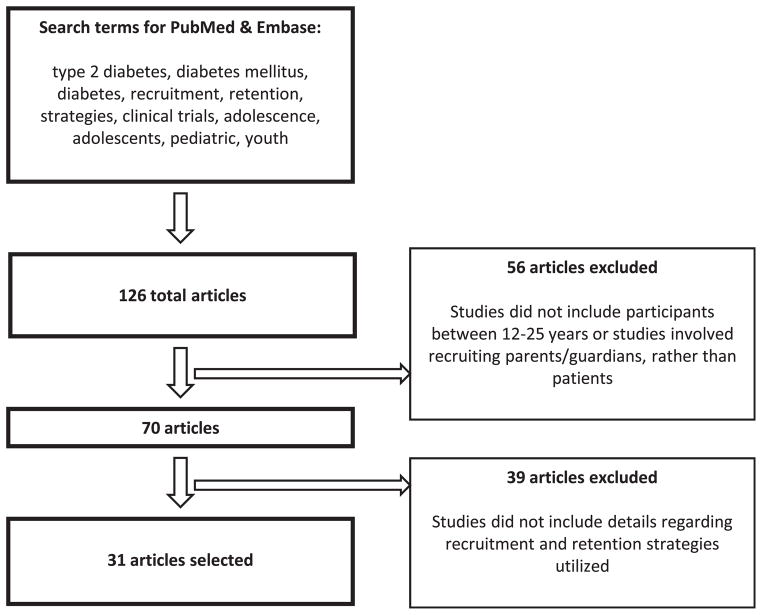

We identified a total of 126 articles, 70 of which applied to adolescents or young adults within the age range of 12–25 years. A total of 31 articles fulfilled all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Table 2 lists details about the clinical trials and the applied recruitment strategies. Monetary incentives were the most common means of engaging adolescents, particularly in research involving chronic conditions such as hypertension, for which patients and families may not be actively seeking medical care [3,4,15–21,24–32]. In studies with school-based recruitment sites, monetary awards were one of the strongest motivating factors [3,27]. In addition, parents enrolling their children in health behavior studies recalled that a free physical health screening at school, followed by a thorough explanation of their child’s health status, was another key incentive [3]. With the continuous change in social communication among youth, researchers have adapted their recruitment approaches to attract the attention of an extremely technology-savvy adolescent population [33,34]. Many pediatric research groups have implemented technology-based incentives—primarily prepaid mobile phones—to attract study participants [19,25,28]. A British group explored the use of a text messaging system in the management of patients with type 1 diabetes between clinic visits. Participants received a pay-as-you-go mobile phone for the duration of the study and a £10 (approximately $15 in 2002 U.S. dollars) phone card, all of which could be put toward personal use, whereas messages to the research team were free of charge [25]. Participation improved, likely because communicating with text messaging required minimal time commitment (<1 minute to send a text message to the diabetes management system) and offered them free mobile phone use [19]. In another example, researchers investigating youth alcohol consumption found that combining texting technology with colloquial or slang-based language (“Y R U drinking/going 2 drink 2 night?”) appealed to their participants and encouraged more precise answers because language formalities were no longer a concern [28].

Figure 1.

Disposition plot of review articles found and selected.

Table 2.

Successful and applicable recruitment and retention strategies

| Strategy | Cohort | Condition | Intervention | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment strategy | ||||

| Incentives (gift certificates, cash or checks, prepaid cellular phones, and calling cards) | Adolescents and young adults ages 8–26 years | Chronic disorders (e.g., HIV, sickle cell disease) and social behavior studies | Behavioral interventions to promote smoking cessation and improve management of HIV, sickle cell, and type 1 diabetes care; health prevention programs to reduce risk factors for alcohol abuse, habitual smoking, type 2 diabetes, and HIV infection | [3,4,15,18,24,26–29] |

| Advertising (online one-click advertisement banners; coupon-based peer recruitment; text message advertisements) | Youth ages 15–30 years | Individuals at risk for HIV infection, active injection drug users, and young people at risk for chlamydia infection | Testing the efficacy of an online HIV-prevention intervention called “Keep It Real,” preventing HIV and hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users, and investigating the impact of a multimedia chlamydia campaign to promote safe sexual behaviors in Australian youth | [14,17,20] |

| Retention strategies | ||||

| Incentives (railway passes, movie gift certificates, school credit, or free food) | Adolescents and young adults ages 8–30 years | Chronic disorders (e.g., HIV, sickle cell disease) and social behavior studies | Behavioral interventions to promote smoking cessation and improve management of HIV, sickle cell, and type 1 diabetes care, health prevention programs to reduce risk factors for alcohol abuse, type 2 diabetes, and HIV infection | [3,4,14,15,17,19,20,24,26–31] |

| Trust/confidentiality (required patient confidentiality for nondisclosure of HIV–positive status, secret smoking behaviors, and covert injection drug use) | Adolescents and young adults ages 12–30 years | Individuals with positive HIV infection, smoking behaviors, and active injection drug use | Behavioral interventions to improve HIV management, promote smoking cessation, and reduce injection and sexual risk behaviors of active injection drug users | [17,20,23,31,36] |

| Continuous contact and communication (acquisition of multiple addresses and at least two telephone numbers; address cards updated every 2 months and addresses verified by phone with parents/guardians; constant tracking of patients’ whereabouts via acquiring alternative contact numbers from friends, relatives, and neighbors; mandatory verification of valid e-mail addresses; and constant communication with frequent appointment reminders) | Youth <25 years | Youth diagnosed with type 1 or 2 diabetes; mobile adolescent mothers that were largely Hispanic and only Spanish speaking; individuals at risk for alcohol abuse, habitual smoking, type 2 diabetes, and HIV infection | Epidemiological study to estimate the prevalence and incidence of diabetes in children and youth; longitudinal study characterizing the effect of young mothers’ interactions with their babies on the child’s emotional and behavioral development; behavioral intervention to improve management of type 1 diabetes care; health prevention programs to reduce risk factors for alcohol abuse, habitual smoking, type 2 diabetes, and HIV infection | [3,4,14,25,26,28–30,36,37] |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

A few clinical groups turned to online advertising on social networking sites. These ads have used flashy recruitment banners on websites heavily trafficked by adolescents and young adults. For one group, targeted advertising on Yahoo! resulted in increased website traffic and successful recruitment numbers [15]. With the current popularity of Facebook (in 2011, it was the most popular website on the World Wide Web), some researchers have used this means of social networking: for example, in a clinical trial designed to increase moderate to vigorous physical activity in middle school girls [35].

A group working with young adult injection drug users enlisted their enrollees to participate in peer-to-peer advertising. The group established a coupon-based strategy that allotted three recruitment coupons (each labeled with a unique serial number for tracking purposes) to participants who had successfully completed the baseline interviews, so that they could pass the coupons on to other young injection drug users. If any of the three new recruits appeared for screening visits and met eligibility criteria, the original injection drug user would be compensated for his or her effort [18].

In another example, the Western Australia Department of Health’s 2005 chlamydia campaign used text message advertising to communicate sexual health information to teens. In post-campaign surveys, participants acknowledged that the messages prompted them to think about chlamydia and show the text to their friends, while sparking discussions about sexually transmitted infections. Despite the slight annoyance, they admitted that text message advertising was a useful marketing tool because “Everyone has a mobile telephone [and] everyone reads their [texts].” This group also found that radio and television advertisements were successful in establishing awareness of the seriousness and prevalence of chlamydia among their teenaged, media-friendly target audience [21].

In a similar report, the Chlamydia Incidence and Re-Infection Rates Study recruited sexually active female adolescents by having research assistants actively recruit all age-eligible youths who walked into the clinic sites. The research assistants were trained and supervised, so as to provide minimal disturbance to clinic staff and patients, as well as to differentiate themselves from clinic staff. Once screened by the research assistants, the adolescent girls participated in the study by completing and mailing monthly sexual behavior questionnaires and vaginal swabs at baseline and 6- and 12-month intervals. With the completion of the questionnaires and vaginal swabs, incentives were provided in the form of retail store gift vouchers and free small gifts (such as tampons and cosmetics). With each successive completion of vaginal swabs and questionnaires, the value of the financial incentive increased. Researchers cited face-to-face recruitment as a significant reason for their success with recruitment, as opposed to more conventional methods such as telephone calls, mailed or posted flyers, or e-mails [36].

Applicable retention strategies (incentives and positive patient-research staff relationship)

Similar to recruitment, retention of youths in clinical studies tends to be more successful when a monetary or material incentive is involved. Several groups found excellent retention (74%–100%) in follow-up visits by offering compensation to patients who continued participation [3,4,15,16,18–21,25,27,28,30–32]. Examples of incentives included railway passes, movie gift certificates, school credit, and retail store gift vouchers to encourage participants to return for clinic visits or to partake in post-study focus groups [3,4,15,16,18,24,25,27–30,32,36]. Moreover, monetary and material incentives required the fewest staff resources and were the easiest to acquire or distribute compared with other retention strategies [3,4,16,19,25,28].

Working with minors, researchers found that success in clinical research required a mix of trust, confidentiality, and continuous contact with young patients and their guardians [18,21,24,26,30,32,37,38]. Earning confidence often included earning the trust of the communities from which patients were recruited. This was especially important for groups requiring particular attention to patient confidentiality—both in chronic disorder studies such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and social behavior studies including smoking cessation and injection drug use [18,21,24,32].

Continuous contact between patients, parents or caregivers, and research staff was the principal tool for the successful retention in follow-up of patients enrolled in youth studies. Studies with more mobile populations, such as a group of poor, highly itinerant adolescent mothers, needed constant tracking to maintain their study participation. Researchers counteracted patient loss by actively acquiring alternative contact numbers from friends, relatives, and neighbors to trace the whereabouts of the wandering adolescent mothers [29]. Constant communication and frequent appointment reminders from the research staff before each visit improved follow-up attendance, particularly in social behavior studies of risk reduction for alcoholism, diabetes, and HIV infection [3,15,27,30,31]. The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study group acquired multiple addresses and contact numbers from participants to ensure that study introductory letters and follow-up calls to parents were received [4]. Two groups in particular used stringent requirements for updating contact information to ensure continued contact. In an alcohol prevention program, the project staff updated addresses every 2 months, and all parents or guardians were contacted by phone to verify addresses. Students’ teachers took part in reminding students, and letters were mailed to parents or guardians 1 week before upcoming data collection events [31]. In an online HIV prevention intervention, research staff required eligible youth to provide detailed contact information, including their name, address, and two telephone numbers, and to create a study identification and password, which required the verification of a valid e-mail address [15].

Because establishing a sense of trust with patients and guardians is crucial for successful clinical trials involving adolescents and young adults, future studies should consider recruiting the entire family. Adolescents with type 2 diabetes are likely to have parents and other relatives with type 2 diabetes, who may have already established a relationship with a medical provider. This suggestion is analogous to current recruitment strategies in childhood obesity trials, which focus more on the parents, rather than exclusively on the child [39]. However, in youths with type 2 diabetes, a family-centered approach may be more difficult because most live with only one parent, or none [13]. The cost of transportation and providers’ work schedules also need to be considered. Thus, facilitating participation in clinical trials by seeing patients in the evening after school or work and on weekends appears promising but has not been thoroughly tested. A transition care program in Australia improved diabetes control, increased clinic attendance, and reduced emergency hospital admission rates for diabetic ketoacidosis among young adults with type 1 diabetes by providing access to appointment coordinators, diabetes educators, and after-hours phone support [40].

Strategies with limited applicability to adolescents with type 2 diabetes

School-based recruitment efforts are typically effective for youth studies other than those regarding type 2 diabetes. Although middle and high school students are commonly affected by obesity and may frequently exhibit high-risk behaviors, even in a population with a particularly high prevalence of type 2 diabetes, such the Navajo, few cases were ascertained in school-based screening programs and thus, even fewer cases are expected to be enrolled in schools with mixed racial and ethnic populations [41]. We found that contacting 64 school nurses and sending out flyers to 128 middle and high schools resulted in no referrals.

However, for clinical trials studying adolescents before the onset of overt type 2 diabetes, schools may provide an opportunity in which word of mouth and peer-to-peer recruitment help establish trust between investigators and potential participants [3,16,20,30]. To spark interest and generate awareness, contests, giveaways, and in-class presentations during school have been used [42,43]. In the HEALTHY study (middle-school based primary prevention trial of type 2 diabetes), clinicians actively participated in the community in what they termed “pre-recruitment” activities, including school orientations and community meetings. They increased enrollment by engaging families and earning their trust, while ensuring that both parents or caregivers and students thoroughly understood the study purpose and easily recognized the members of the research staff [3,17]. In addition, they found that having a continuous rolling recruitment period allowed enrolled students to share their initial experiences and thus encourage peers still considering participation [3,16].

In a recent campaign to study HIV prevention among young black men, the Colorado School of Public Health formed a partnership with MEE Productions, a communications research and marketing firm with strong ties to community-based organizations (CBOs) across the country. An important goal was to explain why the research topic was of particular importance to the community. By aligning itself with the CBOs, the research team found increased access to African-American youth and established trust with participants, who associated the study with the CBOs, and thus were more likely to enroll and to continue participation [43].

Discussion

Successful recruitment and retention in clinical trials in youth with type 2 diabetes is challenging. One reason, although by far not the most important, is the relatively low incidence: In the U.S., approximately 1.8 million adults are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes annually, contrasted by only several thousand new pediatric patients [42]. The relatively small number of new cases limits the pool of candidates eligible for participation in clinical trials [9–11,13,43,44]. However, many clinical studies are conducted in young patients with conditions rarer than type 2 diabetes. Thus, type 2 diabetes in youth represents a specific constellation of taxing factors, such as being a relatively silent but serious medical condition, occurring more frequently in less socioeconomically privileged youths with co-morbid conditions such as obesity, and occurring in youths with suboptimal role models in their families.

Recruitment of minorities poses distinctive difficulties. Previous research abuse, especially in the African-American community, and lack of trust—for example, in the Hispanic community regarding reporting of immigration status—need to be recognized as hurdles to be overcome by gaining their trust. Ethical questions arise in the context of low-income family backgrounds irrespective of ethnicity, owing to both lack of health insurance and access to primary care resources. Thus, participation in a clinical trial might represent the only way of receiving medical care. Questions also arise at the end of clinical trials when the relationship between researcher and participant inevitably terminates, and potentially poses a dilemma if the study participant has come to view the researcher as a primary care provider. A recent publication presented recruitment and retention results according to race in The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study, a multi-center project designed to identify environmental factors that contribute to type 1 diabetes. In general, Hispanic and African-American participants were more than twice as likely to be excluded at screening as their non-Hispanic white counterparts because of incorrect contact information. Socioeconomic patterns discussed in this study suggested that higher mobility, less education, and younger age of the mothers was associated with higher rates of exclusion. Other reasons cited for the prominent differences in enrollment were the time demands of the protocol, unstable living conditions, and communication barriers resulting from language differences and comprehension [44].

As mentioned above, monetary compensation represents one of the incentives most commonly used in clinical research to facilitate recruitment and retention. However, there is a wide range in standards of research compensation that can vary for the same procedure by several orders of magnitude [45]. Inherent ethical, regulatory, and economic issues become even more relevant in the case of vulnerable subjects such as children, especially when belonging to lower socioeconomic strata. In pediatric studies, monetary compensation may be given to parents who take it on behalf of the minor subject or to the minors themselves [45]. Whoever the material recipient is, few provisions are provided by institutional review boards to ensure that the money will be used in the best interests of the child.

It is generally accepted that the amount paid to a research participant should be adequate to provide a fair incentive for participation as well as to offer reimbursement for time and inconvenience. Calculating the amount of reimbursement for an adult might be simple; in the case of a minor, this exercise becomes more difficult because of the lack of a reference system represented by earnings.

It is also generally accepted that the total amount offered should not be so high as to represent an undue enticement. A thought-provoking question is whether there should be an upper limit to the amount of monetary compensation in the first place, or whether the final compensation, the “final price,” should not be limited a priori, but should simply be determined by the intercept between demand and supply, as is typically the case in a free market society. But how much is too much? We raise the question of whether an upper limit of compensation should be based on the average participant, reflecting an ideal, weighted average of each potential participant, or whether it should be determined based on the specific income and living expenses of the prospective participants and their families. This exercise in normalizing the amount of compensation based on location and socioeconomic status of the participant has not been previously implemented, to the best of our knowledge. In theory, a randomized controlled study could be designed in which participants belonging to communities similar in income and epidemiological profile are randomized to receiving a normal reimbursement versus an amount several fold higher for the same research protocol. The null hypothesis would be that recruitment and retention are not different between the two groups of communities.

The issues discussed above are not exclusively relevant and applicable to pediatric research in the field of type 2 diabetes; they are general issues inherent to the nature of clinical research.

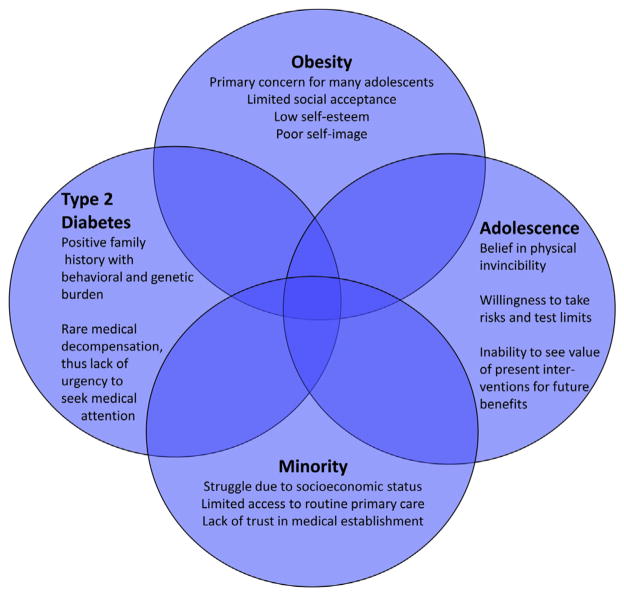

Most clinicians and physician-investigators will agree that adolescents with type 2 diabetes frequently have problems with routine patient care and compliance with diet and medications, and are reluctant to participate in clinical trials. Many of these youths are characterized by the overlap of four uniquely challenging factors: adolescence, minority, type 2 diabetes, and obesity (Figure 2). Most clinical trials in type 2 diabetes in youth focus on beta cell function and blood glucose control, but these outcomes are often not perceived as highly relevant by these patients, who frequently identify obesity as the primary problem. In fact, participation in a clinical trial might even lead to weight gain, for example, due to insulin administration. In addition, obesity is not seen primarily as a health concern by these youngsters, but as an obstacle to fitting a certain body image ideal, thus affecting social acceptance and self-esteem. Therefore, they may not identify health care providers as helpful resources to combat these issues.

Figure 2.

Four subgroups of pediatric type 2 diabetes.

Core components of successful recruitment into clinical trials involving adolescents are established trust between researchers and the participants and their families, monetary incentives, and creative advertising. More time and effort need to be spent investing adolescent participants in the existent benefits of participation in the study, such as material incentives, increased health rewards, and societal benefits, while simultaneously making participation inexpensive (e.g., with reimbursement of transportation costs) and convenient (e.g., with evening or weekend clinic visits or home visits) for the entire family.

Major challenges for researchers studying type 2 diabetes in youth are highlighted by the fact that only six of the 16 interventional trials initiated in this population have been successfully completed to date, and only five prospective, interventional studies have published results [46]. Although the fate of the incomplete studies is not clear, many may have been suspended because of slow recruitment. By comparing results of many large studies in adults (e.g., United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study [UKPDS]) with the only existing large study in adolescents, the TODAY trial, we learned that interventions that work for adults with type 2 diabetes may not be effective in youths with regard to either medical treatment (e.g., metformin) or lifestyle changes. Thus, informative clinical research is urgently needed and steps need to be taken to make this research possible. This may be achieved by learning more about motivation in adolescents with type 2 diabetes, by prospectively collecting data on patient recruitment and retention in future studies, and by providing them and their families and caregivers with tangible benefits and practical help when participating in clinical trials.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Compliance with medications and doctor’s appointments is suboptimal in youth with type 2 diabetes. Additional challenges specific to clinical research add to the generally observed difficult recruitment into clinical trials. Better understanding of effective recruitment strategies of adolescents with other chronic conditions may guide our efforts, but changes to conven-tionalapproachesinclinical research appear necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Allison Sylvetsky, Ph.D., and Alexandra Gardner, B.S., for critical review of the manuscript.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Allen DB. TODAY—a stark glimpse of tomorrow. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2315–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1204710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeitler P, Hirst K, Pyle L, et al. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2247–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drews KL, Harrell JS, Thompson D, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies and methods in the HEALTHY study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(Suppl 4):S21–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liese AD, Liu L, Davis C, et al. Participation in pediatric epidemiologic research: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:829–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lapsley DK, Hill PL. Subjective invulnerability, optimism bias and adjustment in emerging adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:847–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortune T, Wright E, Juzang I, et al. Recruitment, enrollment and retention of young black men for HIV prevention research: Experiences from The 411 for Safe Text project. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:563–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson RL, Boyd JD, Smith TE. Stabilization of the diabetic child. Am J Dis Child. 1940;59:332–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell RA, Mayer-Davis EJ, Beyer JW, et al. Diabetes in non-Hispanic white youth: Prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S102–11. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer-Davis EJ, Beyer J, Bell RA, et al. Diabetes in African American youth: Prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S112–22. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, Reynolds K, et al. Diabetes in Hispanic American youth: Prevalence, incidence, demographics, and clinical characteristics: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S123–32. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: The TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:159–67. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu LL, Yi JP, Beyer J, et al. Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in Asian and Pacific Islander U.S. youth: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S133–40. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bull SS, Vallejos D, Levine D, et al. Improving recruitment and retention for an online randomized controlled trial: Experience from the Youthnet study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:887–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120701771697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diviak KR, Wahl SK, O’Keefe JJ, et al. Recruitment and retention of adolescents in a smoking trajectory study: Who participates and lessons learned. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:175–82. doi: 10.1080/10826080500391704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman FR, Hirst K, Linder B, et al. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes in a sixth-grade multiracial cohort: The HEALTHY study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:953–5. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garfein RS, Swartzendruber A, Ouellet LJ, et al. Methods to recruit and retain a cohort of young-adult injection drug users for the Third Collaborative Injection Drug Users Study/Drug Users Intervention Trial (CIDUS III/ DUIT) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(Suppl 1):S4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rami B, Popow C, Horn W, et al. Telemedical support to improve glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:701–5. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riesch SK, Tosi CB, Thurston CA. Accessing young adolescents and their families for research. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999;31:323–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkins A, Mak DB. Sending out an SMS: An impact and outcome evaluation of the Western Australian Department of Health’s 2005 chlamydia campaign. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18:113–20. doi: 10.1071/he07113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins TM, Xanthakos SA, Zeller MH, et al. Distance to clinic and follow-up visit compliance in adolescent gastric bypass cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:611–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeller MH, Guilfoyle SM, Reiter-Purtill J, et al. Adolescent bariatric surgery: Caregiver and family functioning across the first postoperative year. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Backinger CL, Michaels CN, Jefferson AM, et al. Factors associated with recruitment and retention of youth into smoking cessation intervention studies—a review of the literature. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:359–68. doi: 10.1093/her/cym053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin VL, Greene A, Waller A, et al. Patients’ engagement with “Sweet Talk”—a text messaging support system for young people with diabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howe CJ, Jawad AF, Tuttle AK, et al. Education and telephone case management for children with type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones FC, Broome ME. Focus groups with African American adolescents: Enhancing recruitment and retention in intervention studies. J Pediatr Nurs. 2001;16:88–96. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.23151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuntsche E, Robert B. Short message service (SMS) technology in alcohol research—a feasibility study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:423–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seed M, Juarez M, Alnatour R. Improving recruitment and retention rates in preventive longitudinal research with adolescent mothers. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;22:150–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villarruel AM, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, et al. Recruitment and retention of Latino adolescents to a research study: Lessons learned from a randomized clinical trial. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2006;11:244–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pappas DM, Werch CE, Carlson JM. Recruitment and retention in an alcohol prevention program at two inner-city middle schools. J Sch Health. 1998;68:231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanford PD, Monte DA, Briggs FM, et al. Recruitment and retention of adolescent participants in HIV research: Findings from the REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:192–203. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinbeck K, Baur L, Cowell C, et al. Clinical research in adolescents: Challenges and opportunities using obesity as a model. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:2–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cafazzo JA, Casselman M, Hamming N, et al. Design of an mHealth app for the self-management of adolescent type 1 diabetes: A pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e70. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones L, Saksvig BI, Grieser M, et al. Recruiting adolescent girls into a follow-up study: Benefits of using a social networking website. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:268–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker J, Fairley CK, Urban E, et al. Maximising retention in a longitudinal study of genital Chlamydia trachomatis among young women in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kealey KA, Ludman EJ, Mann SL, et al. Overcoming barriers to recruitment and retention in adolescent smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:257–70. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson ML, Cohen N, Richardson C, et al. A randomized trial of regular standardized telephone contact by a diabetes nurse educator in adolescents with poor diabetes control. Pediatr Diabetes. 2005;6:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boutelle K, Cotton M U.S. National Institutes of Health. Parents as the Agent of Change for Childhood Obesity (PAAC) 2013 Available at: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01197443?term=parental+obesity&rank=1.

- 40.Holmes-Walker DJ, Llewellyn AC, Farrell K. A transitioncareprogramme which improves diabetes control and reduces hospital admission rates in young adults with Type 1 diabetes aged 15–25 years. Diabet Med. 2007;24:764–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim C, McHugh C, Kwok Y, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Navajo adolescents. West J Med. 1999;170:210–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia C, Pintor JK, Lindgren S. Feasibility and acceptability of a school-based coping intervention for Latina adolescents. J Sch Nurs. 2010;26:42–52. doi: 10.1177/1059840509351021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joseph CL, Saltzgaber J, Havstad SL, et al. Comparison of early-, late-, and non-participants in a school-based asthma management program for urban high school students. Trials. 2011;12:141. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baxter J, Vehik K, Johnson SB, et al. Differences in recruitment and early retention among ethnic minority participants in a large pediatric cohort: The TEDDY Study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:633–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimberly MB, Hoehn KS, Feudtner C, et al. Variation in standards of research compensation and child assent practices: A comparison of 69 institutional review board-approved informed permission and assent forms for 3 multicenter pediatric clinical trials. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1706–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gemmill JA, Brown RJ, Nandagopal R, et al. Clinical trials in youth with type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]