Abstract

Background

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with multiple maternal and neonatal complications. However, interventions to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy have not been adequately evaluated.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy and associated pregnancy complications.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (20 October 2011) and MEDLINE (1966 to 20 October 2011).

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials and quasi-randomised trials of interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed for inclusion all potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. At least two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We have presented results using risk ratio (RR) for categorical data and mean difference for continuous data. We analysed data using a fixed-effect model.

Main results

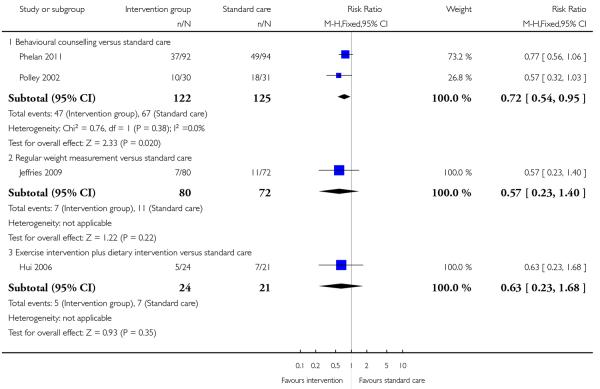

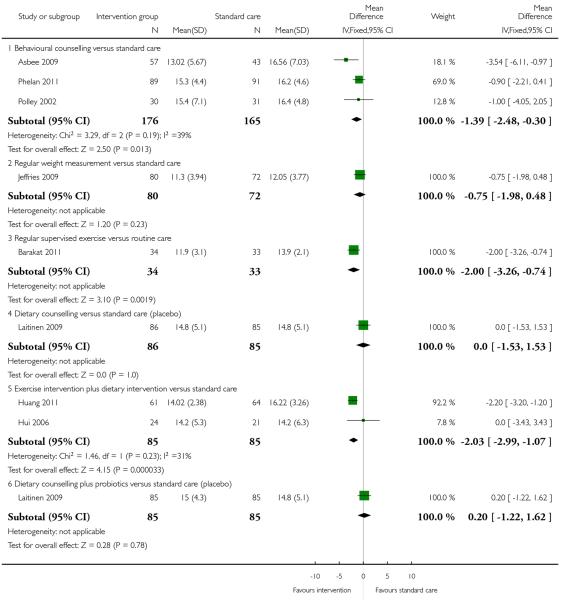

We included 28 studies involving 3976 women; 27 of these studies with 3964 women contributed data to the analyses. Interventions focused on a broad range of interventions. However, for most outcomes we could not combine data in a meta-analysis, and where we did pool data, no more than two or three studies could be combined for a particular intervention and outcome. Overall, results from this review were mainly not statistically significant, and where there did appear to be differences between intervention and control groups, results were not consistent. For women in general clinic populations one (behavioural counselling versus standard care) of three interventions examined was associated with a reduction in the rate of excessive weight gain (RR 0.72, 95% confidence interval 0.54 to 0.95); for women in high-risk groups no intervention appeared to reduce excess weight gain. There were inconsistent results for mean weight gain (reported in all but one of the included studies). We found a statistically significant effect on mean weight gain for five interventions in the general population and for two interventions in high-risk groups.

Most studies did not show statistically significant effects on maternal complications, and none reported significant effects on adverse neonatal outcomes.

Authors’ conclusions

There is not enough evidence to recommend any intervention for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy, due to the significant methodological limitations of included studies and the small observed effect sizes. More high-quality randomised controlled trials with adequate sample sizes are required to evaluate the effectiveness of potential interventions.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): * Weight Gain; Counseling; Diet; Exercise; Infant, Newborn; Overweight [complications; * prevention & control]; Pregnancy Complications [* prevention & control]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Pregnancy weight gain guidelines

In 2009, the Institute of Medicines (IOM) in the United States updated earlier guidelines on weight gain during pregnancy (Medicine 1990; Medicine 2009). The report set out specific ranges of weight gain for women with different prepregnancy weights: suggesting that underweight women (body mass index (BMI) less than 18.5 kg/m2) gain 28 to 40 lbs (12.5 kg to 18 kg); normal weight women (BMI 18.5 kg/m2 to 24.9 kg/m2) gain 25 to 35 lbs (11.5 kg to 16 kg); whereas overweight women (BMI 25 kg/m2 to 29.9 kg/m2) were advised to gain between 15 and 25 lbs (7 to 11.5 kg) and obese women (BMI at least 30 kg/m2) to gain between 11 and 20 lbs (5 to 9 kg) (Medicine 2009).

Previous guidelines from the IOM (Medicine 1990) had been widely adopted but not universally accepted. However, a review of relevant information confirmed that pregnancy weight gain within the IOM’s recommended ranges was associated with the best outcomes for both mothers and infants, and that weight gain within the IOM’s recommended ranges is not harmful for the mothers or for their infants (Abrams 2000).

No official recommendations or clinical guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy exist in the United Kingdom (UK) (Ford 2001). However, a recent report from the UK Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE 2010) suggested a more comprehensive guidance for the care of overweight and obese women, and recommended weighing women in the third trimester and again when women are admitted in labour. Guidelines in other countries have also recommended monitoring weight gain in pregnancy. The optimal gestational weight gain in Swedish women was 4 kg to 10 kg for BMI less than 20; 2 kg to 10 kg for BMI 20 to 24.9. For women with a BMI of 25 to 29.9, a weight gain of less than 9 kg was recommended, and pregnant women with a BMI of 30 or more were recommended to gain less than 6 kg in weight (Cedergren 2007). Pregnant Asian women in general had lower weight gains in comparison to pregnant women in Europe and North America (Abrams 1995; Siega-Riz 1993). Hence, maternal weight gain recommendations based on data from high-income countries may not be applicable to Asian women. A study to produce ethnicspecific maternal weight gain recommendations was performed in China. The recommended total weight gain was 13 kg to 16.7 kg, 11 kg to 16.4 kg, and 7.1 kg to 14.4 kg respectively for women of low (BMI less than 19), moderate (BMI 19 to 23.5), and high (BMI greater than 23.5) BMI measurement (Wong 2000).

Trends in pregnancy weight gain

Although the 1990 IOM guidelines have now been promoted for two decades it has been estimated that over this time only 30% to 40% of pregnant women in the United States gain gestational weight within the IOM recommended ranges (Abrams 2000; Cogswell 1999; Medicine 1990; Olson 2003). Furthermore, gestational weight gain above the guidelines is more common than gestational weight gain below (Stotland 2006). Several studies on gestational weight gain in the USA and Europe indicate that about 20% to 40% of women are gaining weight above the recommendations (Cedergren 2006; Medicine 2009; Olson 2003) and the prevalence of excessive gestational weight gain is increasing (Abrams 2000; Rhodes 2003; Schieve 1998). A retrospective cohort study undertaken to examine the trend in weight gain during pregnancy of 1,463,936 women over 16 years in North Carolina found that the proportion of women gaining excessive gestational weight (more than 18 kg) increased from 15.5% in 1988 to 19.5% in 2003; an additional 40 women per 1000 gained excessive weight by 2003 (Helms 2006). The recent IOM report summarised the situation in a number of countries; compared with two decades earlier “Women today are also heavier; a greater percentage of them are entering pregnancy overweight or obese, and many are gaining too much weight during pregnancy” (Medicine 2009).

Weight gain during pregnancy is generally inversely proportional to prepregnancy weight category. Overall, underweight women were least likely to exceed weight gain recommendations although obese women tended to gain less weight than normal and overweight women (Abrams 1989; Bianco 1998; Edwards 1996; Walling 2006). For instance, two large population-based studies, in Sweden and the United States, reported similar findings. They found that approximately 30% of average and overweight women had high gestational weight gain, whereas approximately 20% of obese women had high gestational weight gain (Cedergren 2006; Cogswell 1995).

Pregnancy weight gain and outcomes for mothers and infants

It is well known from large studies in a number of countries that excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with multiple maternal and neonatal complications. Retrospective cohort studies have examined the relationship between gestational weight gain and adverse neonatal outcomes among infants born at term. It was established that gestational weight gain above the upper limit of the IOM guideline was associated with a low five-minute Apgar score, seizure, hypoglycaemia, polycythaemia, meconium aspiration syndrome and large-for-gestational age compared with women within weight gain guidelines (Hedderson 2006; Stotland 2006). Obese women with low gestational weight gain had a decreased risk for the following outcomes: pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, instrumental delivery, and large-for-gestational age births, whereas, excessive weight gain of obese women increased the risk for caesarean delivery in all maternal BMI classes (Cedergren 2006).

Findings from a national study in the UK revealed that compared with pregnant women in general, obese pregnant women were at increased risk of having a co-morbidity diagnosed before or during pregnancy (in particular pregnancy-induced hypertension and gestational diabetes), were more at risk of having induction of labour and a caesarean birth, were more likely to have postpartum haemorrhage and their babies were at increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, of being large for gestational age and more likely to be admitted for special care (CMACE 2010).

There have been a number of studies which conclude that excessive gestational weight gain increases postpartum weight retention (Gunderson 2000; Keppel 1993; Polley 2002; Rooney 2002; Rossner 1997; Scholl 1995) and is related to a two- to three-fold increase in the risk of becoming overweight after delivery (Gunderson 2000). Moreover, mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy had children at higher risk of being overweight in early childhood (Oken 2007).

However, to be too strict in weight gain restriction might not have the expected result. It was established that in three trials involving 384 women, energy or protein restriction of pregnant women who were overweight or exhibited high weight gain significantly reduced weekly maternal weight gain and reduced mean birth-weight but had no effect on pregnancy-induced hypertension or pre-eclampsia. It concluded that protein or energy restriction of pregnant women is unlikely to be beneficial and may be harmful to the infant (Kramer 2003).

Description of the intervention

Dietary control, exercise and eating behaviour modification are the main elements for controlling weight. Pregnancy may be an optimal time to inform and challenge women to change their eating habits and physical activities, and thereby prevent excessive weight gain.

How the intervention might work

There are systematic reviews which aimed to assess the effect of dietary advice, exercise intervention and psychosocial intervention for achieving weight loss in overweight and obese adults. The results of Cochrane review on exercise for overweight or obesity support the use of exercise as a weight loss intervention, particularly when combined with dietary change (Shaw 2006). People who are overweight or obese may benefit from psychological interventions, particularly behavioural and cognitive-behavioural strategies, to enhance weight reduction. The evidence suggests that these measures are predominantly useful when combined with dietary and exercise strategies (Shaw 2005). In addition, overall, weight loss strategies using dietary, physical activity, or behavioural interventions produced significant improvement in weight among people with prediabetes (Norris 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Given the increasing prevalence and negative consequences of excessive gestational weight gain, preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy is potentially important. Intervention might help pregnant women to achieve the recommended weight gain, with the objective of ensuring the best possible outcome for their infants and themselves. Although there are Cochrane reviews evaluating the effect of dietary advices, exercise, and psychological interventions on controlling weight, there are no systematic review evaluating interventions for controlling excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

The aim of this review is to identify and systematically review all randomised controlled trials of interventions for limiting weight gain during pregnancy to provide the best available evidence for clinical decision-making and to stimulate further research about preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy and associated pregnancy complications.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We have included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs of interventions aimed at preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy, irrespective of their country of origin or language.

Types of participants

Pregnant women.

Types of interventions

Any intervention (e.g. nutrition intervention, exercise intervention, health education or counselling) for preventing excessive weight gain compared with routine care or other interventions for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Excessive weight gain as defined by trialists.

Secondary outcomes

For the mothers

Weight gain.

Low weight gain as defined by trialists.

Preterm birth.

Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia.

Need for and indication for induction of labour.

Caesarean delivery.

Postpartum complication including postpartum haemorrhage, wound infection, endometritis, need for antibiotics, perineal trauma, thromboembolic disease, maternal death.

Behaviour modification outcomes: diet, physical activity.

For the newborns

Birthweight greater than 4000 gm or greater than the 90th centile for gestational age and infant sex.

Birthweight less than 2500 gm or less than the 10th centile for gestational age and infant sex.

Complication related to macrosomia including hypoglycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia, infant birth trauma (palsy, fracture, shoulder dystocia).

Long-term health outcomes

Maternal weight retention postpartum.

Childhood weight.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co-ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (20 October 2011).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are given a code (or codes) depending on the topic. The codes are linked to review topics. The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using these codes rather than keywords. In addition, we searched MEDLINE (1966 to 20 October 2011) using the search strategy given in Appendix 1

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion and where necessary, by involving a third author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and where necessary, by involving a third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original studies to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study in six domains (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting bias, and other sources of bias) using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third author.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

We included a cluster-randomised trial in the analyses (Luoto 2011) along with individually-randomised trials. We adjusted their sample sizes and event rates using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.12 estimated by the trial authors and published in Luoto 2010.

Dealing with missing data

The missing standard deviations were imputed from 95% confidence intervals or standard errors. We have reported the results of some included studies in the additional tables when the missing data could not be imputed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where we pooled studies in meta-analysis, we assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta-analysis using the I2 statistic. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I2 was greater than 50% (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not generate funnel plots to assess possible publication bias for the primary outcome because there were not enough studies in each comparison (fewer than 10 studies).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used a fixed-effect model to pool studies to produce summary statistics when the I2 was less than 50%. On the other hand, when I2 was greater than 50%, we repeated the analysis using a random-effects model. We have indicated in the results text when we have used a random-effects model as the pooled result represents an average treatment effect and, in the presence of high heterogeneity, such results should be interpreted with caution.

However, in this version of the review, for most outcomes we could not combine data in a meta-analysis, and where we did pool data,no more than two studies could be combined for a particular intervention and outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For our primary outcome we had planned to carry out subgroup analysis by:

prepregnancy BMI: (1) underweight (2) normal weight (3) overweight (4) obese (as defined by trialists);

gestational age at first visit prenatal clinic: (1) 20 weeks or less; or (2) more than 20 weeks;

gestational age at first visit prenatal clinic: (1) 28 weeks or less; or (2) more than 28 weeks.

Gestational age at 28 weeks (early in the third trimester) is the stage at which weight gain is rapidly increasing.

After examining the interventions offered to different population subgroups, we decided that rather than carrying out subgroup analysis by prepregnancy BMI we would present results for women drawn from the general population (and including all weight categories) and high-risk groups (including women with, or at high risk of, gestational diabetes and/or who were overweight or obese at recruitment) in separate comparisons. We made this decision as the clinical management of women in high-risk groups is likely to be different, and the interventions offered to these women were designed specifically to address their high-risk status.

For other subgroup analysis, in this version of the review, we did not carry out planned subgroup analyses, due to insufficient studies contributing data for the primary outcome (a maximum of three studies provided data for our primary outcome in each comparison). We included one cluster trial but again, there were not enough studies to carry out subgroup analysis by studies using different units of randomisation. In future updates if more data become available for existing comparisons, we will carry out planned analysis for the review’s primary outcomes and, where appropriate, we will carry out the subgroup interaction tests available in RevMan 2011.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not carry out sensitivity analysis because only two included studies were combined for the primary outcome.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The search strategies described above identified 63 potential studies. Following application of eligibility criteria, we included 28 studies in this review. We excluded 12 studies. Two studies are currently awaiting assessment (we have contacted authors for more information) and the other 21 studies are ongoing.

Included studies

From 28 included studies, two studies were quasi-RCTs (Bechtel-Blackwell 2002; Moses 2006); one study was a cluster-RCT (Luoto 2011); the remaining studies were RCTs.

Participants: the 28 included studies involved 3976 participants, although one of these studies (with 12 women) did not report on any of the review’s outcomes and has not contributed data to the review (Magee 1990) (we have included information about this trial in the Characteristics of included studies tables, but it is not otherwise discussed in the remaining sections below). Therefore, our findings are based on 27 studies with 3964 participants. The number of participants in each study varied from 20 to more than 300. The age of participants ranged from 25 to 49 years, except for one study (Bechtel-Blackwell 2002) which included adolescent women aged 13 to 18 years.

Settings: two trials (Santos 2005; Vitolo 2011) were conducted in Brazil. One trial (Huang 2011) was conducted in Taiwan. All others were conducted in developed countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Spain and the United States of America; however, two of these studies (Hui 2006; Polley 2002) recruited women with low, or low-middle incomes.

Interventions: most of the interventions considered in this review focused on modifying diet and increasing exercise, however, there was considerable variation in the interventions and in the care received by control groups. Interventions included dietary counselling, dietary intervention (e.g. provision of dietary supplements or foodstuffs), exercise counselling, exercise interventions (e.g. supervised exercise sessions), nutritional monitoring, regular weight measurement, computer-assisted self-interview, and the use of an appetite suppressant drug. These interventions varied in intensity and may have involved more than one approach. Interventions were compared with standard care (which again varied considerably in different settings and was not always well-described) or with another type of intervention. Some studies included more than two arms and these studies may be included in more than one comparison.

Outcomes: only five of the 27 included studies contributing data reported excessive weight gain during pregnancy as a primary outcome. Other studies reported other outcomes, but in all studies except the trial by Callaway 2010, weight gain was reported as one of the outcomes. Some studies reported low weight gain as a outcome. Other outcomes reported included maternal complications and adverse neonatal outcomes.

Only one study (Thornton 2009) reported on postpartum complication outcomes such as postpartum haemorrhage, wound infection, endometritis, need for antibiotics, perineal trauma, thromboembolic disease, or maternal death.

We have reported results separately for pregnant women drawn from the general population (and which may include overweight and obese women) and for known high-risk groups. Of the 27 studies contributing data, 13 specifically recruited women from high-risk groups (i.e. women who were all overweight or obese at recruitment, or women at high risk of gestational diabetes due to weight or other risk factors). Ten studies recruited women from the general pregnant population and results for high- and low-risk women were not reported separately. In four studies (Jeffries 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002; Vitolo 2011), women in all weight categories were recruited, but findings were reported separately for women with low/normal versus overweight/obese prepregnancy weights; therefore, relevant findings from these four studies are reported in both comparisons.

Studies recruiting women in high-risk groups: there were differences in the prepregnancy weight of women recruited to studies; only women who were overweight or obese were recruited in studies by Callaway 2010; Guelinckx 2010; Quinlivan 2011; Rhodes 2010; Santos 2005; Thornton 2009; Wolff 2008; women who were either considered overweight or appeared to be gaining excessive weight in early pregnancy were recruited by Boileau 1968 and Silverman 1971. Women with or at high risk of gestational diabetes were included in four studies (Korpi-Hyovalti 2011; Luoto 2011; Moses 2009; Rae 2000) A mix of underweight, normal, overweight, and obese women were included in studies by Jeffries 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002; Vitolo 2011 with separate results provided for women in the overweight/obese groups.

Interventions in these studies included:

diethylpropion hydrochloride (appetite suppressant drug) versus placebo (Boileau 1968; Silverman 1971);

diet and/or exercise counselling and/or behavioural counselling or weight monitoring versus standard care or routine care (Callaway 2010; Guelinckx 2010; Korpi-Hyovalti 2011; Jeffries 2009; Luoto 2011; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002; Quinlivan 2011; Vitolo 2011; Wolff 2008);

alternative interventions compared (brochure plus counselling versus brochure alone (Guelinckx 2010); high versus low glycaemic diet (Moses 2009); energy restricted diabetic diet versus non-energy restricted diabetic diet (Rae 2000); low glycaemic load versus low fat diet (Rhodes 2010); aerobic exercise plus relaxation versus relaxation alone (Santos 2005); nutritional counselling and weight monitoring versus nutritional counselling alone (Thornton 2009)).

Studies recruiting women in all weight categories: 10 studies included women in all weight categories (Asbee 2009; Barakat 2011; Bechtel-Blackwell 2002; Clapp 2002; Clapp 2002a; Huang 2011; Hui 2006; Jackson 2011; Laitinen 2009; Moses 2006) and as we have mentioned above, four studies reported findings for under and normal weight women separately (Jeffries 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002; Vitolo 2011).

Interventions in these studies varied considerably and the comparison conditions also differed. Interventions included:

diet and/or exercise intervention and/or behavioural counselling or weight monitoring versus standard care or routine care (Asbee 2009; Huang 2011; Jackson 2011; Jeffries 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002; Vitolo 2011);

intensive exercise intervention (up to 85 sessions) versus routine care (Barakat 2011);

alternative interventions compared (low versus high glycaemic diet (Moses 2006); low glycaemic diet and exercise versus high glycaemic diet and exercise (Clapp 2002); three different exercise interventions (Clapp 2002a); group exercise and video versus diet and exercise information pack (Hui 2006); group nutrition education and computer assisted interview versus computer interview (Bechtel-Blackwell 2002); diet counselling with or without a probiotic supplement versus placebo (three arms) (Laitinen 2009).

Excluded studies

We excluded 12 studies. We excluded seven studies for the following reasons: participants included both pregnant and nonpregnant women (two studies); participants were not pregnant (postpartum or other non-pregnant participants) (four studies); or the intervention was not relevant (one study). The remaining five studies were not RCTs.

Risk of bias in included studies

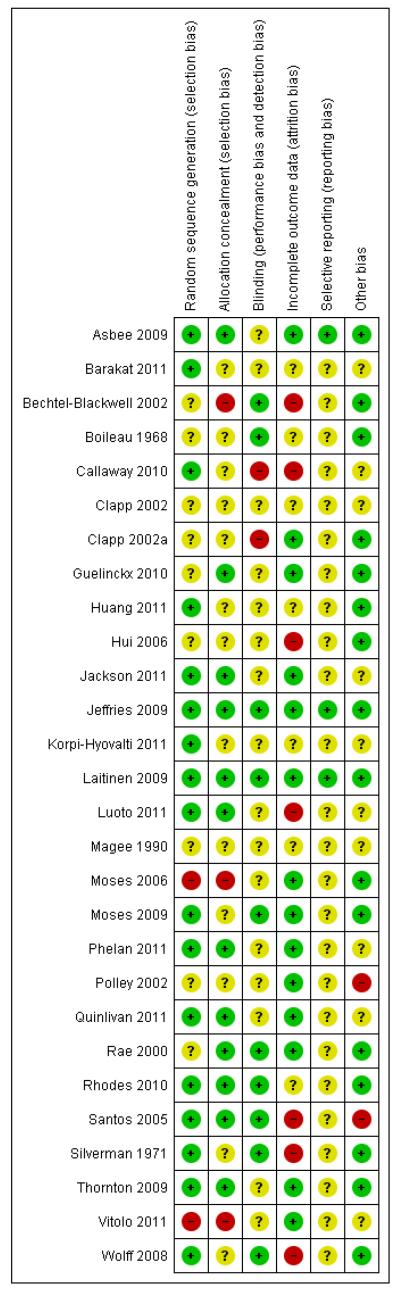

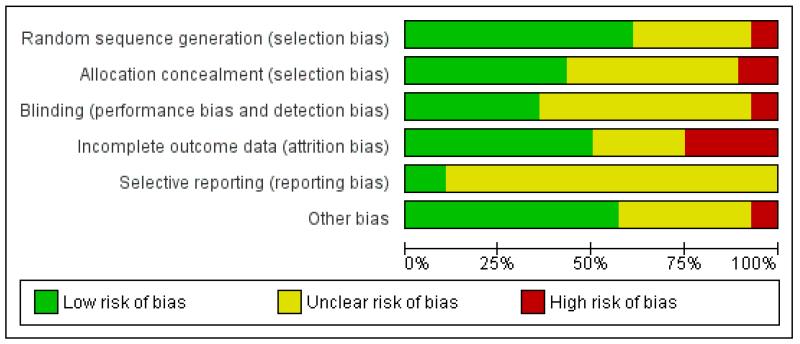

Details of the methodological quality of each study are given in Characteristics of included studies, Figure 1, and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 2. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Seventeen out of 27 included studies contributing data were assessed as being at low risk of bias for generation of the randomisation sequence and 12 used methods that we judged were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. Three studies were assessed to use methods at high risk of bias for allocation concealment. The remaining studies were unclear for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Ten out of 27 studies had taken some steps to implement blinding. Acheiving blinding of treatment allocation for diet and exercise interventions is, however, not feasible and for most studies it was difficult to ascertain whether the lack of blinding, or unsuccessful blinding, impacted on outcomes or resulted in any systematic bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen of the studies either had relatively low levels of attrition or had carried out intention-to-treat analysis. Seven studies had a high rate of loss to follow-up. In the remaining studies, loss of outcome data was unclear.

Selective reporting

It was difficult to assess bias associated with the outcome reporting bias as we did not have access to study protocols and we did not know whether results for all outcomes where data had been collected had been reported; we therefore assessed most of these studies as being unclear for the outcome reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We have reported in the Characteristics of included studies tables where we noted any obvious other sources of bias (such as clear differences between groups at baseline).

Effects of interventions

Our findings are based on data from 27 studies with 3964 women. Some studies had more than two arms and may have been included in more than one comparison and four studies reported data separately for high- and low-risk groups and relevant data have been included in more than one comparison. One study (Luoto 2011) was a cluster-randomised trial, and in the analyses we adjusted the sample size and event rates for this study by using an ICC from Luoto 2010. We have set out the original data from the Luoto 2011 study in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. The original data and adjusted data of continuous data of the cluster-randomised trial (Luoto 2011).

| Outcome | Intervention (Original data) | Control (Original data) | M1 | ICC2 | Design effect3 | Adjusted sample4 sizes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Cluster number | Total number | x ± SD | Cluster number | Total number | x ± SD | Intervention | Control | ||||

| Maternal | 7 | 216 | 13.8±5.8 | 7 | 179 | 14.2±5.1 | 28.21 | 0.12 | 4.27 | 50.64 | 41.96 |

| Weight gain | |||||||||||

M = average cluster size = ((total number of intervention + total number of control)/(cluster number of intervention + cluster number of control)

ICC = intraclass correlation; obtained from the reliable external source (Luoto 2010).

Design effect = 1 + (M-1)/ICC

Adjusted sample sizes = n / design effect

Table 2. The original data and adjusted data for dichotomous data of the cluster-randomised trial (Luoto 2011).

| Outcomes | Intervention (Original data) | Control (Original data) | M1 | ICC2 | Design effect3 | Intervention (Adjusted data)4 | Control(Adjusted data)4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster number | Total number | n | Cluster number | Total number | n | total number | n | total number | n | ||||

| Preeclampsia | 7 | 216 | 14 | 7 | 179 | 10 | 28.21 | 0.12 | 4.27 | 50.64 | 3.28 | 41.96 | 2.34 |

| Birth-weight > 4000 grams | 7 | 216 | 37 | 7 | 179 | 36 | 28.21 | 0.12 | 4.27 | 50.64 | 8.67 | 41.96 | 8.44 |

| Infant birth-weight > 90th centile | 7 | 216 | 26 | 7 | 179 | 34 | 28.21 | 0.12 | 4.27 | 50.64 | 6.10 | 41.96 | 7.97 |

| Infant birth-weight < the 10th centile | 7 | 216 | 10 | 7 | 179 | 5 | 28.21 | 0.12 | 4.27 | 50.64 | 2.34 | 41.96 | 1.17 |

M = average cluster size = (total number of intervention + total number of control)/(cluster number of intervention + cluster number of control)

ICC = intraclass correlation; obtained from the reliable external source (Luoto 2010).

Design effect = 1 + (M-1)/ICC

Adjusted data = n / design effect

For most outcomes only one or two studies provided outcome data. Where outcome data were available for studies examining different types of diet and exercise or weight monitoring interventions, we have presented findings in a single forest plot (with the different interventions separated into subgroups) but, due to differences in the interventions examined, we have not pooled the results for different types of interventions in the meta-analysis and report subtotals only.

1. Interventions to prevent excessive weight gain versus standard care or routine care (interventions in general population groups) (nine trials)

Primary outcome

1.1 Excessive weight gain

This outcome was reported in four trials including a total of 444 women examining three different types of interventions. Trials comparing regular weight management (Jeffries 2009) and a diet and exercise intervention (Hui 2006) showed no significant differences between groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.23 to 1.40, and, RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.68 respectively). Two studies with 247 women (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002) showed a positive treatment effect associated with behavioural counselling compared with standard care (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.95, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.1).

Secondary outcomes

For the mothers

1.2 Weight gain

Weight gain was reported in nine trials. Six different interventions were examined and overall, three different types of interventions achieved positive treatment effects.

We pooled results from three trials with 341 women (Asbee 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002) examining behavioural counselling. Women in the intervention group gained 1.39 kg less than controls (95% CI −2.48 to −0.30); there was moderate heterogeneity for this outcome (I2 = 39%). There was evidence from one trial (Barakat 2011) that an intensive intervention involving supervised exercise sessions resulted in women gaining on average 2 kg less compared with controls (95% CI −3.26 to −0.74).

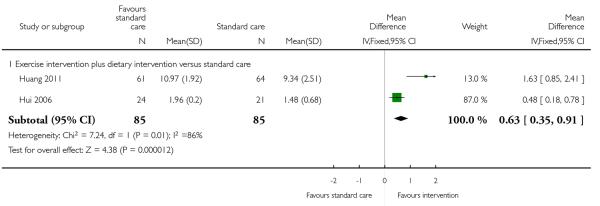

Pooled results from two studies (Huang 2011; Hui 2006) examining a diet and exercise intervention also favoured the intervention group (mean difference (MD) −2.03, 95% CI −2.99 to −1.07) although the positive effect was only associated with one of the two trials (Huang 2011).

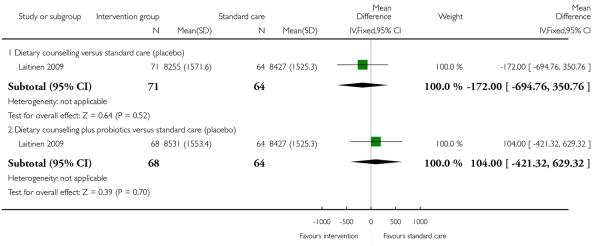

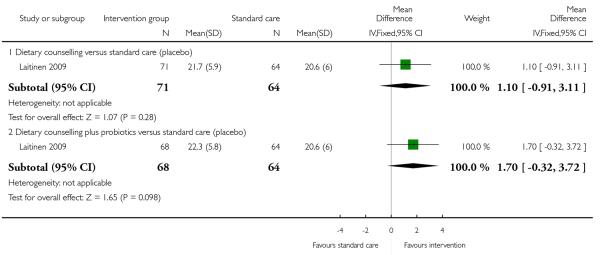

Results were not consistent however, for other interventions examined in single studies, there were no significant differences between groups: dietary counselling with the provision of probiotics (RR 0.20, 95% CI −1.22 to 1.62), dietary counselling alone (RR 0.00, 95% CI −1.53 to 1.53) and regular weight monitoring (RR −0.75, 95% CI −1.98 to 0.48) (Analysis 1.2).

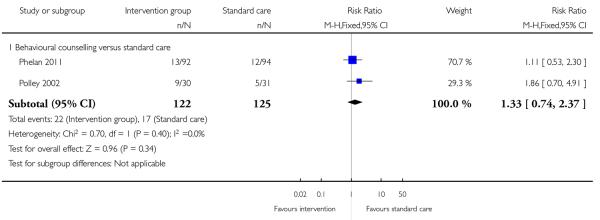

1.3 Low weight gain

This outcome was reported in two trials with 247 women examining a behavioural counselling intervention (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002); there was no significant difference between groups (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.37) (Analysis 1.3).

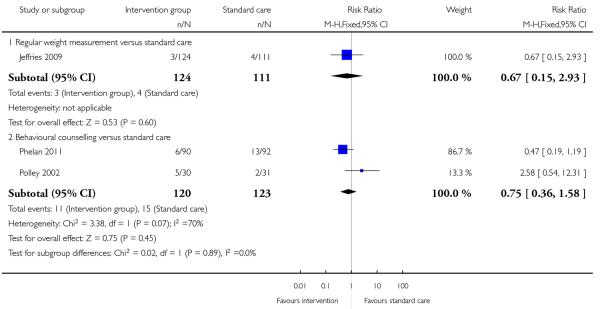

1.4 Preterm birth

Three trials examining two different interventions (regular weight management (Jeffries 2009) and behavioural counselling (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002) reported findings for preterm birth. There were no significant differences in the number of babies born prematurely for women in the intervention and control groups for either intervention (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.93, and 0.75, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.58 respectively)(Analysis 1.4). There was heterogeneity for the pooled results examining behavioural counselling with an I2 value of 70%. In view of heterogeneity, we repeated the analyses using a random-effects model; again, there was no evidence of a significant difference between groups (data not shown).

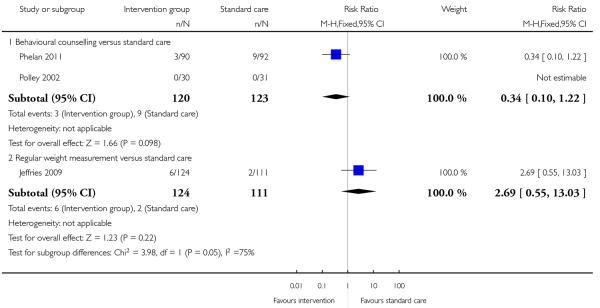

1.5 Pre-eclampsia

This outcome was measured in three trials and results from these trials did not demonstrate any significant differences between groups (Analysis 1.5) (regular weight management (Jeffries 2009) (RR 2.69, 95% CI 0.55 to 13.03) and behavioural counselling (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002) (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.22)).

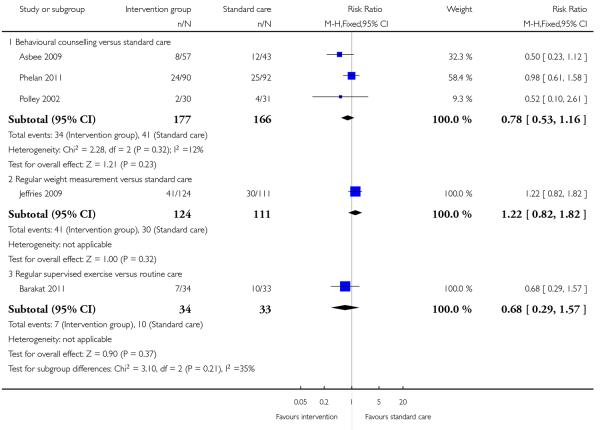

1.6 Need for and indication for induction of labour and caesarean delivery

None of the included studies with general population samples reported on the number of women requiring induction of labour. The number of women experiencing caesarean delivery was reported in five trials. There were no clear differences between groups receiving interventions involving behavioural counselling (three trials; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.16), regular weight management (one trial; RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.82) or regular supervised exercise (one trial, 0.68, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.57) compared with controls (Analysis 1.6).

1.7 - 1.10 Behaviour modification outcomes: diet, physical activity

In a three-arm trial Laitinen 2009 examined the effects of dietary counselling with or without probiotic supplements compared with controls; there was no clear evidence that either intervention was associated with differences in reported mean energy or fibre intake compared with controls (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8).

Huang 2011 in a study with 125 women and Hui 2006 in a study with 45 women both measured women’s reported physical activity scores on different scales. Both studies suggested that women receiving diet and exercise interventions had higher mean activity scores than controls, and in both studies the difference between groups reached statistical significance (MD 1.63, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.41, and MD 0.48, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.78 respectively) (Analysis 1.9).

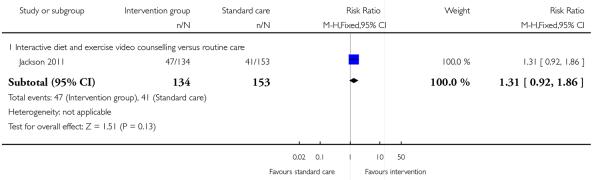

A single study with 287 women examining the effect of an interactive video counselling intervention reported on the number of women saying they exercised for 30 minutes on most days (Jackson 2011). There was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups; about a third of women in both arms of the trial reported regular exercise (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.86)(Analysis 1.10).

For the newborns

1.11 - 1.14 High and low birthweight

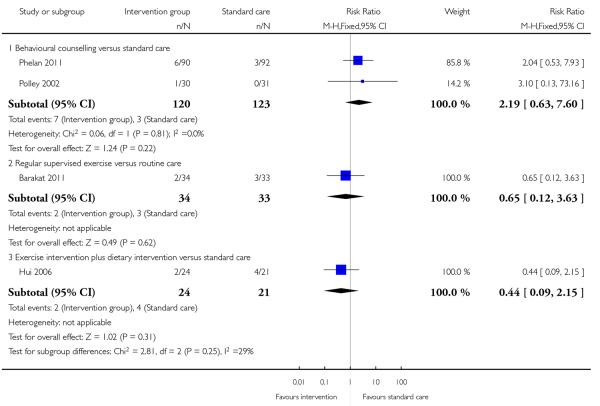

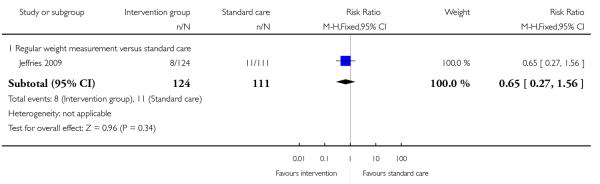

Four studies (examining three different interventions) reported the number of babies with a birthweight above 4000 gm. None of the studies showed evidence of a significant difference between intervention groups and controls (behavioural counselling, 2 studies, RR 2.19, 95% CI 0.63 to 7.60; supervised exercise, 1 study RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.12 to 3.63; exercise plus diet intervention, 1 study RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.15) (Analysis 1.11). One additional study examining regular weight monitoring reported on the number of babies with birthweight above the 90th centile. Again, there was no clear difference between groups (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.56) (Analysis 1.12).

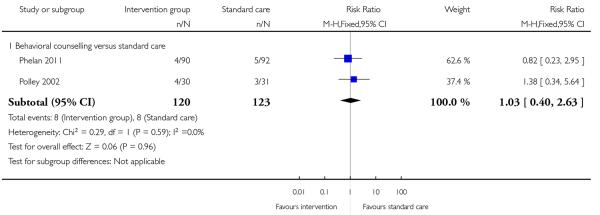

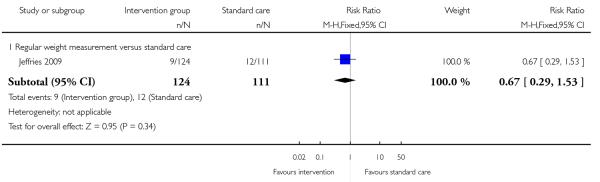

Three studies reported on the number of babies with low birth-weight. There was no strong evidence that interventions were associated with low infant birthweight (behavioural counselling, 2 studies RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.63; regular weight management, 1 study, RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.53) (Analysis 1.13; Analysis 1.14).

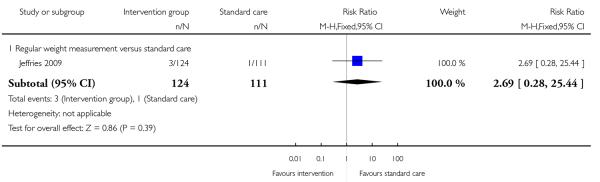

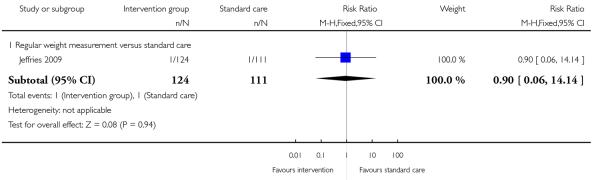

1.15 - 1.16 Complication related to macrosomia

A single study examining regular weight monitoring reported the number of babies with neonatal hypoglycaemia (Jeffries 2009); there was no clear difference between groups (RR 2.69, 95% CI 0.28 to 25.44) (Analysis 1.15). This same study reported on shoulder dystocia during the birth; again, there was no clear evidence that the intervention was associated with any difference in this birth complication (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.06 to 14.14) (Analysis 1.16).

Long-term health outcomes

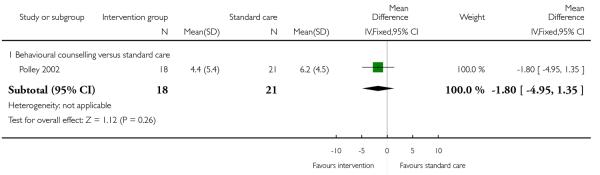

1.17 - 1.18 Maternal weight retention

A single study with a sample of 39 women (Polley 2002) reported on the mean weight retention in the postpartum period. On average, although women receiving a behavioural counselling intervention retained less weight (1.8 kg) compared with controls, there was a wide CI for this outcome and the difference between groups was not statistically significant (95% CI −4.95 to 1.35 kg) (Analysis 1.17).

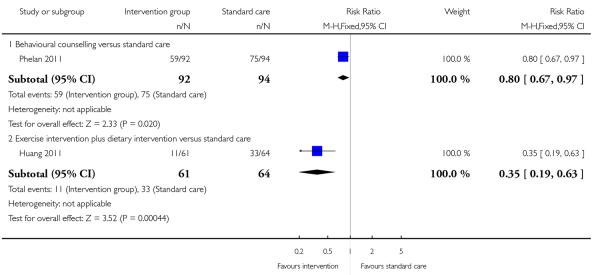

The results of two trials examining different interventions; behavioural counselling intervention (Phelan 2011 with 186 women) and exercise and dietary intervention (Huang 2011 with 125 women) reported that women in intervention groups were less likely to be above their prepregnancy or early pregnancy weight at six months postpartum (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.97, and RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.63 respectively) (Analysis 1.18).

2. Interventions to prevent excessive weight gain: alternative interventions (interventions in general population groups) (five trials)

Although six trials are included in this comparison, for many outcomes only single studies reported results and for some of our primary and secondary outcomes no studies contributed data. The study by Clapp 2002a examined different types and treatment order of exercise interventions and results for this study are reported separately for different comparison arms.

Primary outcome

Excessive weight gain

None of the studies in this comparison reported results for this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

For the mothers

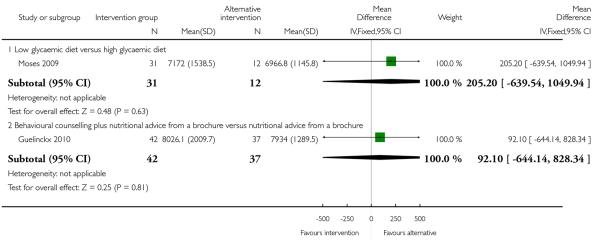

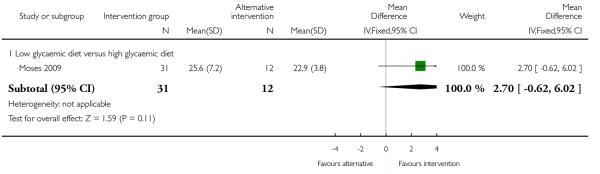

2.1 Weight gain

Weight gain was reported in four trials each comparing different types of interventions.

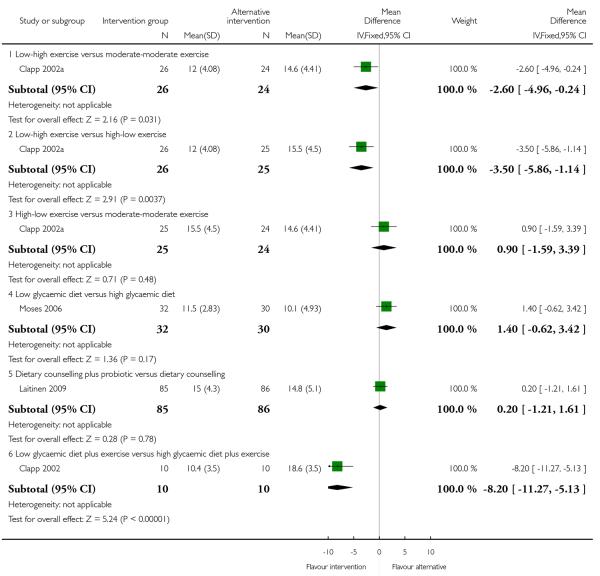

Clapp 2002a looked at whether an intervention encouraging different exercise intensities at different stages of pregnancy (before versus after 20 weeks gestation) had an impact on pregnancy weight gain. Results suggest that low intensity exercise in early pregnancy moving on to higher intensity exercise after 20 weeks was associated with a lower pregnancy weight gain than either high followed by low intensity exercise or moderate exercise throughout (MD −3.50, 95% CI −5.86 to −1.14, and MD −2.60, 95% CI −4.96 to −0.24 respectively) (Analysis 2.1).

Moses 2006 examined low versus high glycaemic diets and found no clear differences in pregnancy weight gain between groups (MD 1.40, 95% CI −0.62 to 3.42). Dietary counselling with a probiotic supplement did not seem to be associated with any differences in weight gain compared with counselling alone (MD 0.20, 95% CI −1.21 to 1.61) (Laitinen 2009) (Analysis 2.1).

Clapp 2002 in a study with 20 women examined a low glycaemic diet plus exercise versus a high glycaemic diet plus exercise and reported a considerably lower mean weight gain in the low glycaemic group (MD −8.20, 95% CI −11.27 to −5.13).

One trial (Bechtel-Blackwell 2002) comparing computer-assisted self-interview plus nutrition education with computer-assisted self-interview plus standard nutritional counselling reported the data of weight gain in each trimester but did not report standard deviation; we have set out findings in an additional table (Table 3).

Table 3. Weight gain (computer-assisted self-interview plus nutrition education).

| Study | Trimester | CASI plus nutrition education | CASI plus standard nutrition counselling | F | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean weight gain (lb.) | n | Mean weight gain (lb.) | 6.13 | 0.0000 | ||

| Bechtel-Blackwell 2002 | 1 | 17 | 3.20 | 18 | 6.27 | 6.13 | 0.0000 |

| 2 | 22 | 14.51 | 24 | 14.88 | 2.33 | 0.056 | |

| 3 | 22 | 15.14 | 24 | 12.29 | 3.44 | 0.0060 | |

2.2 Caesarean delivery

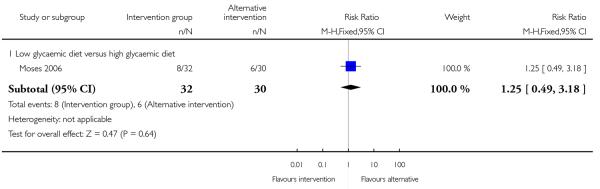

The number of women needing caesarean delivery was reported in a single trial comparing low and high glycaemic diets (Moses 2006). There was no significant difference between groups (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.49 to 3.18) (Analysis 2.2).

2.3 - 2.4 Behaviour modification outcomes: diet, physical activity

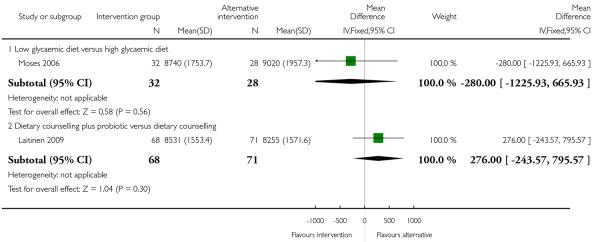

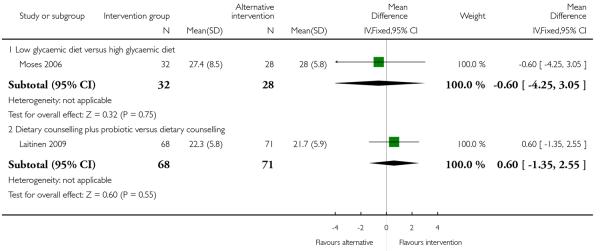

In a three-arm trial Laitinen 2009 examined the effects of dietary counselling with or without probiotic supplements compared with controls; when the two intervention arms were compared there was no clear evidence that one intervention was superior to the other in terms of differences in reported mean energy or fibre intake compared with controls (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). Reported energy and fibre intake were also compared in the trial by Moses 2006 looking at high and low glycaemic diets; there was no clear evidence of differences between interventions for these outcomes (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). None of the studies reported results for activity rates for women receiving different types of interventions. None of the included studies with general population samples reported findings for other maternal outcomes in this comparison.

For the newborns

2.5 - 2.6 High and low birthweight

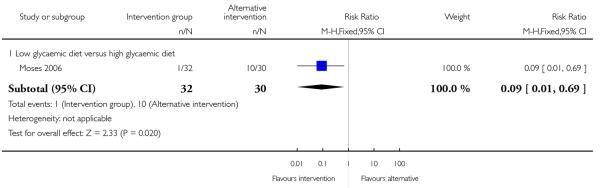

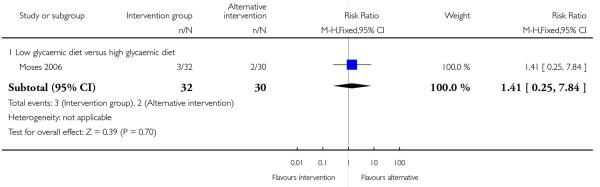

None of the studies in this comparison reported on the number of babies with birthweight greater than 4000 gm. Moses 2006 comparing low and high glycaemic diets with 62 women found a lower number of babies with birthweight above the 90th centile for gestational age in the low glycaemic diet group (RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.69) (Analysis 2.5). This same study also reported babies with birthweight below the 10th centile and there were no apparent differences between groups (RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.25 to 7.84) (Analysis 2.6).

No studies in this comparison reported findings for other outcomes for newborns.

Long-term health outcomes

Maternal weight retention

Maternal weight retention in the postnatal period was not reported in these studies.

3. Interventions to prevent excessive weight gain versus standard care or routine care (interventions in high-risk groups) (10 trials)

Primary outcome

3.1 Excessive weight gain

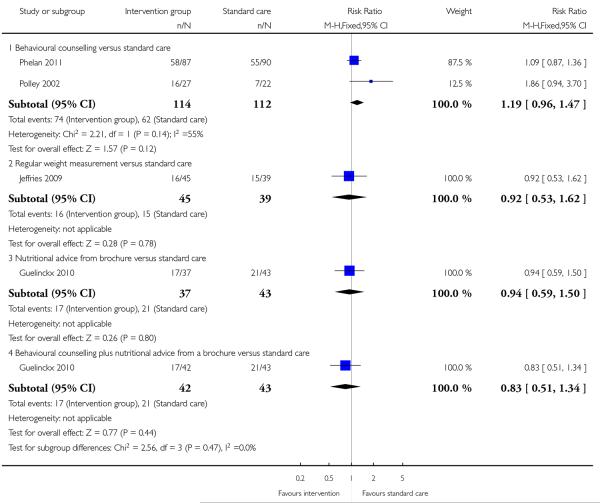

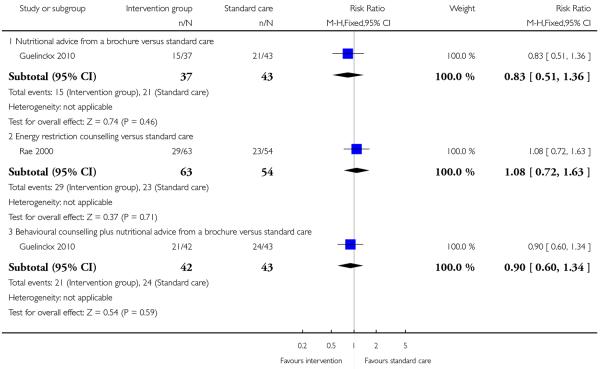

This outcome was reported in four trials (Guelinckx 2010; Jeffries 2009; Phelan 2011; Polley 2002). The trial by Guelinckx 2010 had three arms. For women in high-risk groups, none of these interventions was associated with any difference in the number of women gaining excessive weight compared with controls receiving standard care (behavioural counselling, RR 1.19 95% CI 0.96 to 1.47 (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002); regular weight measurement, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.62 (Jeffries 2009); or nutritional advice from a brochure with or without behavioural counselling, (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.34, and RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.50 respectively (Guelinckx 2010)) (Analysis 3.1).

Secondary outcomes

For the mothers

3.2 Weight gain

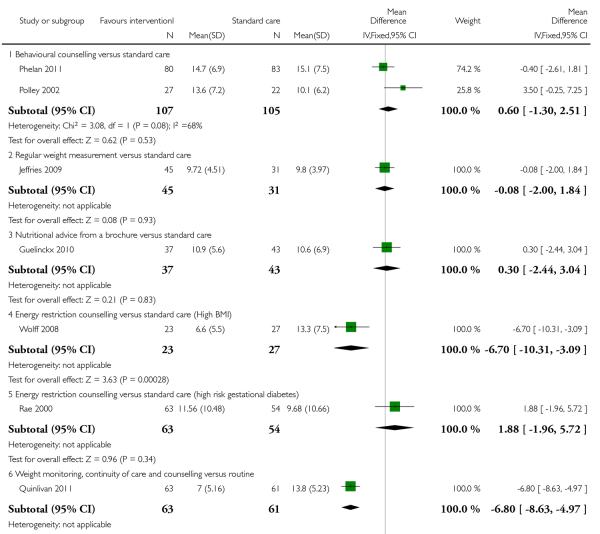

Weight gain was reported in nine trials (one with two intervention arms Guelinckx 2010). Seven different interventions were examined and overall, only one intervention type (involving regular weight monitoring, counselling and continuity of caregivers) was associated with a statistically significant lower mean weight gain in the intervention group: Quinlivan 2011 in a study involving 124 women reported women in the intervention arm gaining on average 6.8 kg less than controls (95% CI −8.63 to −4.87).

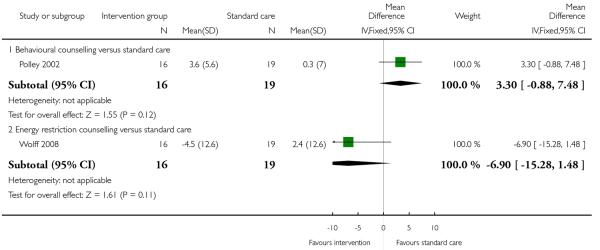

Two studies (Rae 2000; Wolff 2008) examined energy restriction counselling. (Rae 2000 recruited women at high risk of gestational diabetes and Wolff 2008 women who were overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy). In the study recruiting women with a high BMI (Wolff 2008), weight gain was 6.7 kg less in the intervention group (95% CI −10.31 to −3.09); this difference between groups was statistically significant. In the study by Rae 2000 examining a similar intervention, there was no strong evidence of any difference between groups (MD 1.88, 95% CI −1.96 to 5.72).

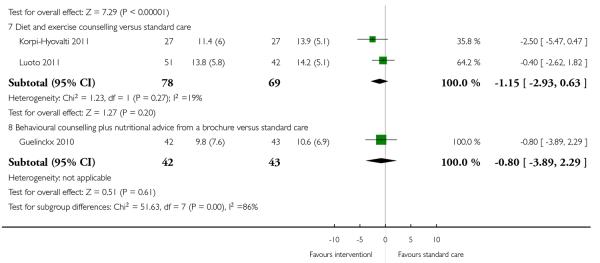

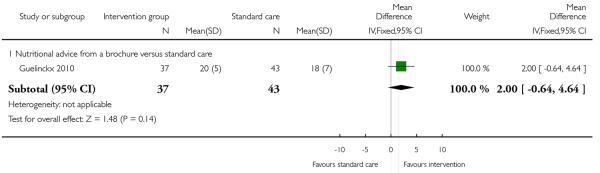

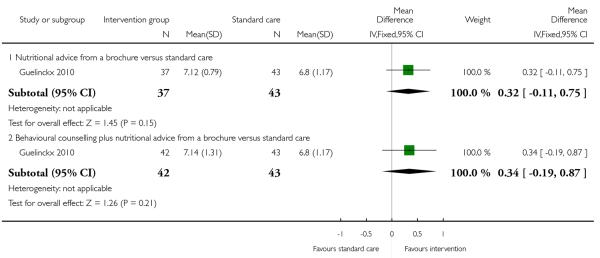

For other types of interventions there were no significant differences between groups in mean weight gain for women in high-risk groups (behavioural counselling (two studies, MD 0.60, 95% CI −1.30 to 2.51), regular weight measurement (one study, MD −0.08, 95% CI −2.00 to 1.84), diet and exercise counselling (two studies, MD −1.15, 95% CI −2.93 to 0.63) and a nutrition brochure with or without counselling, MD −0.80, 95% CI −3.89 to 2.29 and MD 0.30, 95% CI −2.44 to 3.04 respectively) (Analysis 3.2).

3.3 Low weight gain

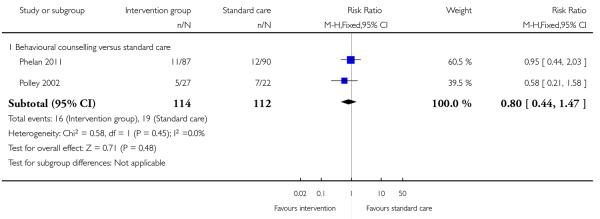

This outcome was reported in two trials with 226 high-risk women examining a behavioural counselling intervention; there was no significant difference between groups (MD 0.80, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.47) (Analysis 3.3).

3.4 Preterm birth

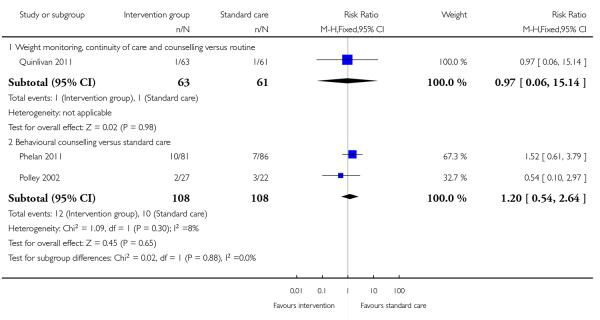

Three trials examining two different interventions (regular weight monitoring and continuity of care (Quinlivan 2011) and behavioural counselling (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002)) reported findings for preterm birth. There were no significant differences in the number of preterm births in the intervention and control groups for either intervention (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.14, and RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.64 respectively) (Analysis 3.4).

3.5 Pre-eclampsia

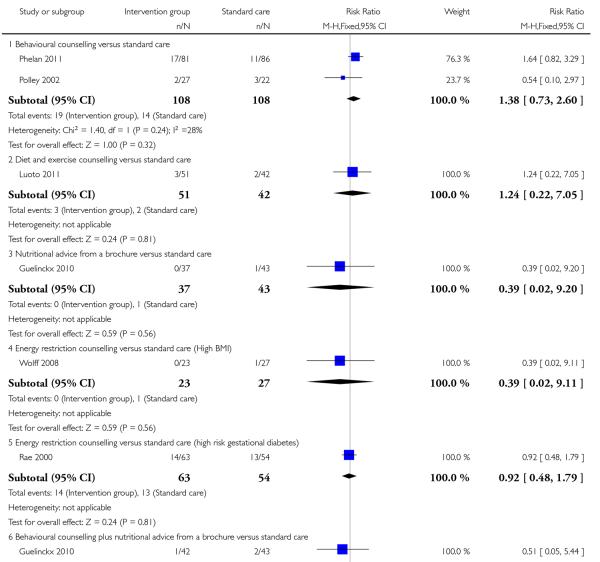

This outcome was measured in six trials examining five different interventions. None of these interventions was associated with significant differences between groups for pre-eclampsia (behavioural counselling, RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.60 (Phelan 2011; Polley 2002); diet and exercise counselling, RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.22 to 7.05 (Luoto 2011 cluster-randomised trial); brochure with or without diet counselling, RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.44 and RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.02 to 9.20 respectively (Guelinckx 2010); and energy restriction counselling for women with a high BMI RR 0.39 95% CI 0.02 to 9.11, or women at high risk of gestation diabetes RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.79 (Rae 2000; Wolff 2008) (Analysis 3.5).

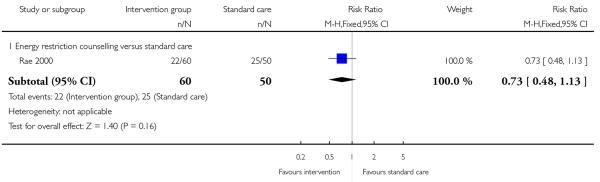

3.6 - 3.7 Need for and indication for induction of labour and caesarean delivery

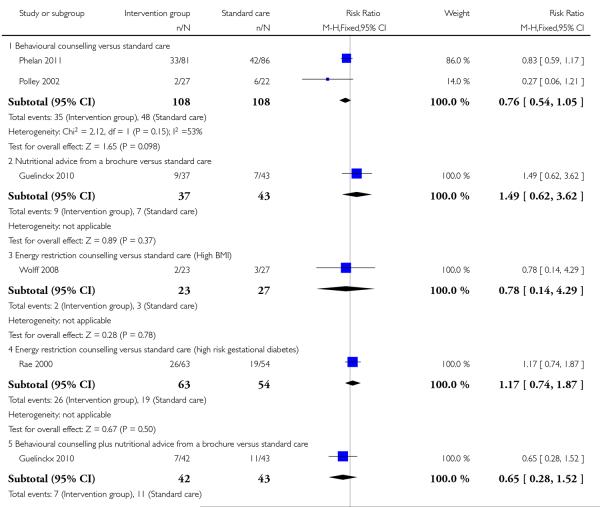

Two included studies with high-risk samples reported on the number of women requiring induction of labour (Guelinckx 2010; Rae 2000); there was no clear evidence of differences between controls and groups receiving energy restriction counselling (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.63) or a nutrition brochure with or without counselling (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.34, and RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.36 respectively) (Analysis 3.6). The number of women experiencing caesarean delivery was reported in five trials. There were no clear differences between groups receiving interventions involving behaviour counselling (two trials, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.05); a nutrition brochure with or without counselling (one trial, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.52, and RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.62 respectively); or energy restriction counselling (two trials,(high BMI, RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.14 to 4.29; high risk of gestational diabetes RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.87) compared with controls (Analysis 3.7).

3.8 - 3.11 Behaviour modification outcomes: diet, physical activity

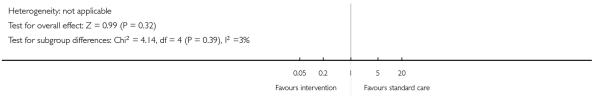

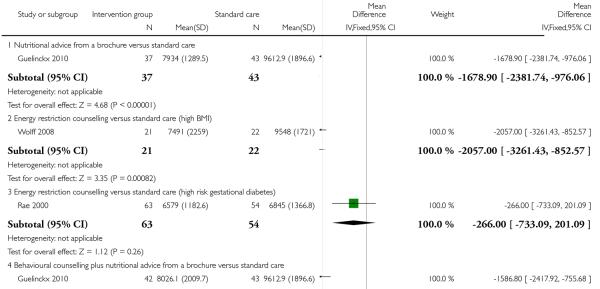

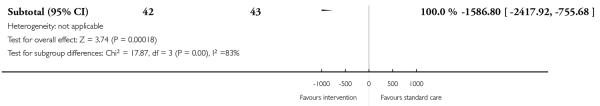

Three trials examined mean reported energy intake. Guelinckx 2010 reported lower energy intake for women receiving a nutrition brochure with or without counselling compared with controls (MD −1586.80(kj), 95% CI −2417.92 to −755.68 and MD −1678.90 (kj), 95% CI −2381.74 to −976.06 respectively). The results from two studies (Rae 2000; Wolff 2008) examining energy restriction counselling in high-risk groups showed that energy intake (kj) was significantly reduced in the intervention group in a study recruiting women with high BMI (MD −2057.00, 95% CI −3261.43 to − 852.57) whereas in a study recruiting women at high risk of gestational diabetes there was a relatively small, and statistically non significant reduction in intake (MD −266.00 kg, 95% CI −733.09 to 201.09) (Analysis 3.8).

Guelinckx 2010 also reported results for fibre intake. There was no apparent difference between groups (Analysis 3.9). Physical activity scores were also examined in this study and women receiving nutrition brochures with or without counselling had similar mean scores compared with controls (Analysis 3.10).

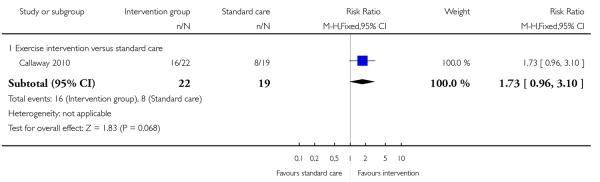

Finally, a study examining an exercise intervention found no significant evidence of a difference between groups in the number of women engaging in physical activity equivalent to > 900 kcal energy expenditure per week (RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.96 to 3.10) (Callaway 2010, Analysis 3.11).

For the newborns

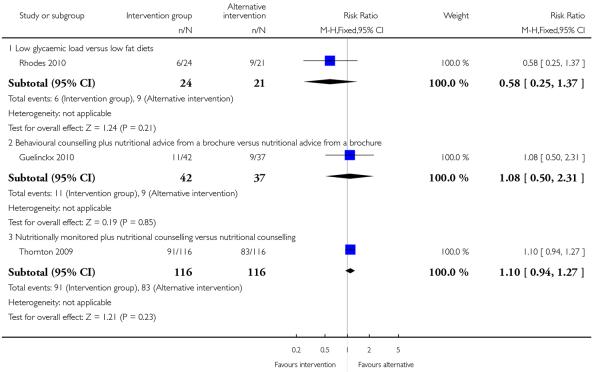

3.12 - 3.15 High and low birthweight

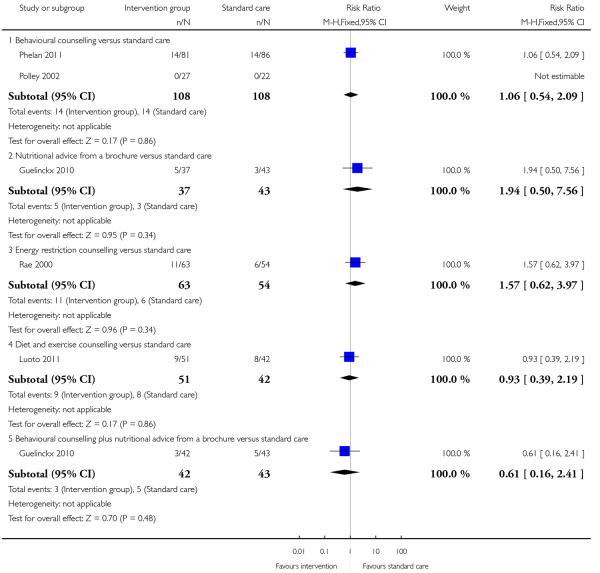

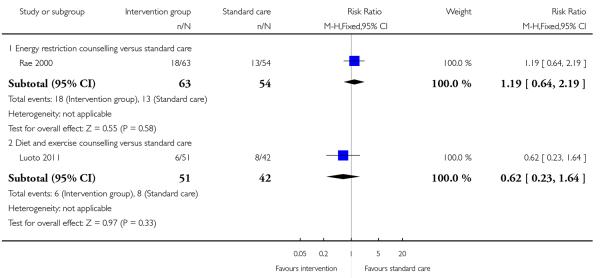

Six studies (examining five different interventions) reported the number of babies with a birthweight above 4000 gm. None of the interventions showed evidence of a significant difference between groups (Analysis 3.12) (behavioural counselling RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.09; nutrition brochure RR 1.94, 95% CI 0.50 to 7.56; nutrition brochure plus counselling RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.41; energy restriction counselling RR 1.57, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.97; diet and exercise counselling RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.39 to 2.19). Two additional studies examining energy restriction counselling (Rae 2000) and a cluster-randomised trial (Luoto 2011) looking at a diet and exercise counselling reported on the number of babies with birthweight above the 90th centile. Again, there was no clear difference between intervention and control groups (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.64 to 2.19 and RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.64 respectively) (Analysis 3.13).

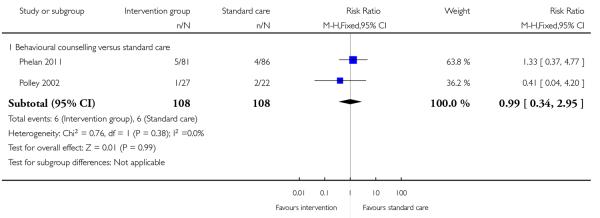

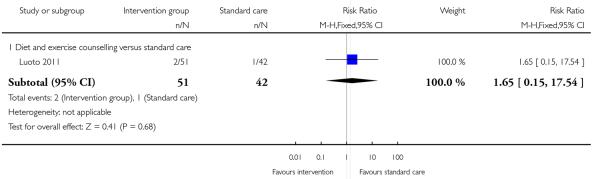

Three studies reported on the number of babies with low birthweight. There was no strong evidence that interventions were associated with low infant birthweight (behavioural counselling (two studies) RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.95; diet and exercise counselling RR 1.65, 95% CI 0.15 to 17.54) (Analysis 3.14; Analysis 3.15).

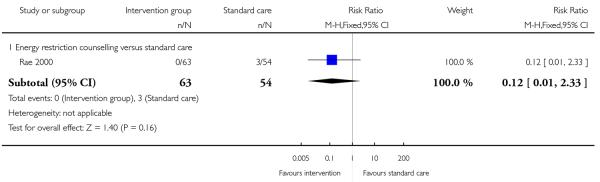

3.16 - 3.17 Complication related to macrosomia

A single study examining weight restriction counselling reported the number of babies with neonatal hypoglycaemia and with shoulder dystocia at the birth (Rae 2000); there was no clear difference between groups for either outcome (Analysis 3.16; Analysis 3.17).

Long-term health outcomes

3.18 - 3.19 Maternal weight retention

Two studies reported on mean maternal weight retention. A study with a sample of 39 women (Polley 2002) looking at behavioural counselling and a study by Wolff 2008 examining energy restriction counselling reported on the mean weight retention in the postpartum period. Neither study demonstrated significant differences in mean weight retention between intervention and control groups (Analysis 3.18).

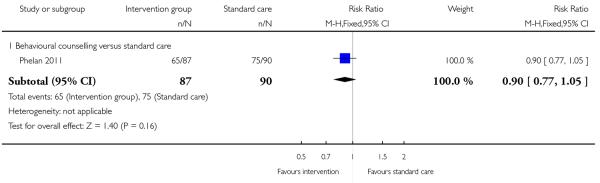

A single study with results for 177 high-risk women examining behavioural counselling interventions (Phelan 2011) found no differences between intervention and control women in terms of the number of women above their prepregnancy or early pregnancy weight at six months postpartum (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.05) (Analysis 3.19).

4. Interventions to prevent excessive weight gain: alternative interventions (interventions in high risk-groups) (five trials)

Primary outcome

4.1 Excessive weight gain

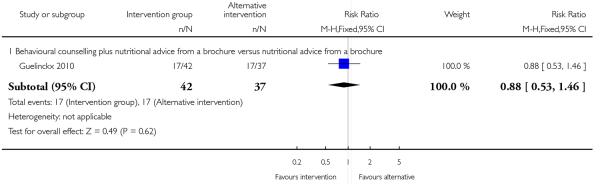

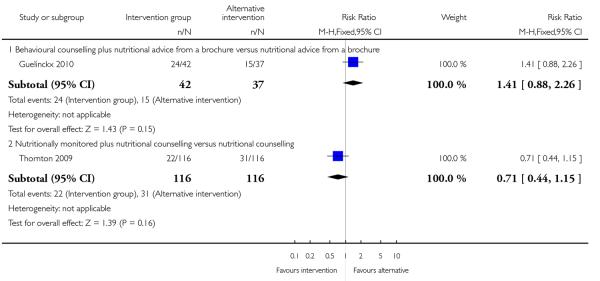

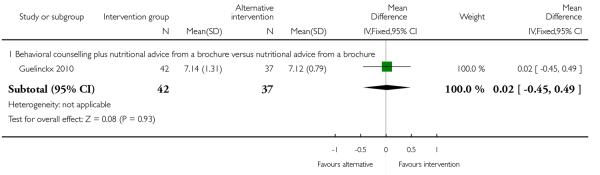

This outcome was reported in one trial (Guelinckx 2010) examining nutritional advice from a brochure with or without counselling, There was no significant difference between the two interventions for the number of women gaining excessive weight (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.46) (Analysis 4.1).

Secondary outcomes

For the mothers

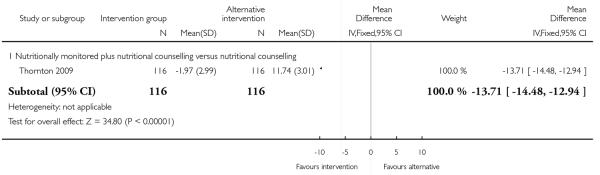

4.2 Weight gain

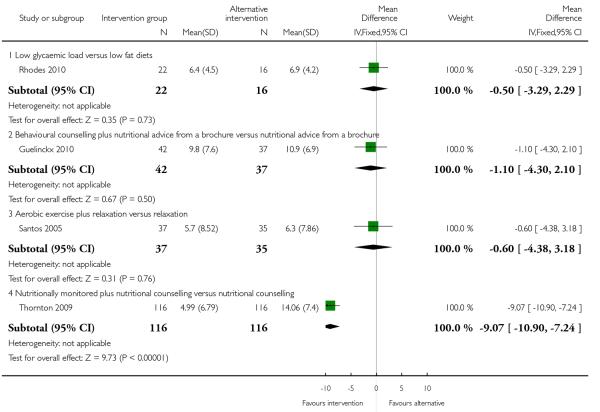

Weight gain was reported in four trials examining alternative interventions in high-risk groups. Only one trial with 232 women (Thornton 2009) examining nutritional counselling with or without nutritional monitoring found a significant difference between groups; the group that had the additional monitoring intervention had a lower mean weight gain (MD −9.07, 95% CI −10.90 to −7.24). For other types of interventions, it was not clear which type of intervention was associated with lower weight gain (low glycaemic load versus low fat diets (MD −0.50, 95% CI −3.29 to 2.29, Rhodes 2010), behavioural counselling with or without a nutritional brochure (MD −1.10, 95% CI −4.30 to 2.10, Guelinckx 2010), aerobic exercise with or without relaxation (RR −0.60, 95% CI −4.38 to 3.18 Santos 2005) (Analysis 4.2).

Low weight gain

No trials in this comparison reported on this outcome.

4.3 Preterm birth

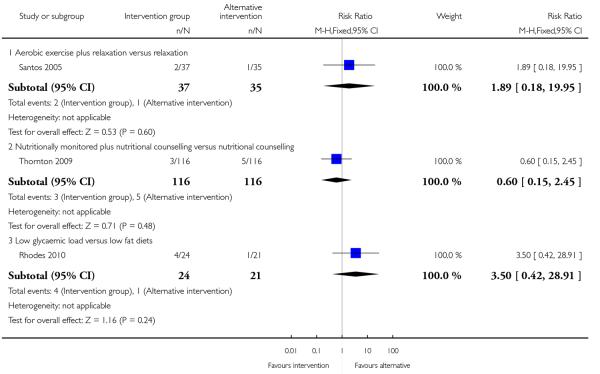

Three trials examining different interventions reported on this outcome. It was not clear that any intervention was superior to alternatives in the number of preterm births (aerobic exercise with or without relaxation RR 1.89, 95% CI 0.18 to 19.95; nutrition counselling with or without monitoring RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.45; low GI versus low fat diet RR 3.50, 95% CI 0.42 to 28.91) (Analysis 4.3).

4.4 Pre-eclampsia

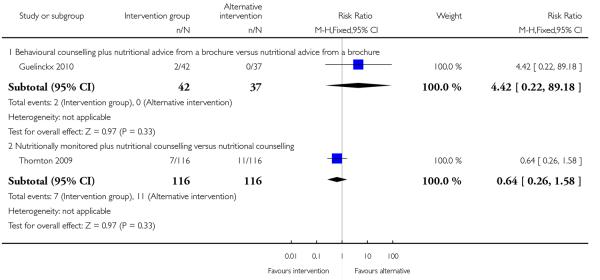

This outcome was measured in two trials examining different interventions. Neither trial showed evidence of a difference between two interventions (nutrition counselling with or without monitoring RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.58; nutrition brochure with or without counselling RR 4.42, 95% CI 0.22 to 89.18) (Analysis 4.4).

4.5 - 4.6 Need for and indication for induction of labour and caesarean delivery

Two included studies with high-risk samples reported on the number of women requiring induction of labour (Guelinckx 2010; Thornton 2009); there was no clear evidence of differences between groups (Analysis 4.5). The number of women experiencing caesarean delivery was reported in three trials (Guelinckx 2010; Rhodes 2010; Thornton 2009). There were no clear differences between groups receiving different types of interventions (low GI versus low fat diet RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.37; nutrition brochure with or without counselling RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.50 to 2.31; nutrition counselling with or without monitoring RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.27) (Analysis 4.6).

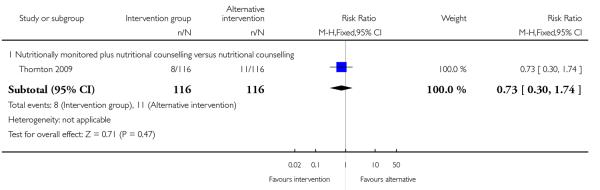

4.7 Postpartum complication

Thornton 2009 reported on postpartum complication including haemorrhage and infection postpartum and found no evidence of differences between groups (Analysis 4.7).

4.8 - 4.10 Behaviour modification outcomes: diet, physical activity

There were no clear differences between alternative interventions for reported energy or fibre intake or physical activity scores for women in high-risk groups (Analysis 4.8; Analysis 4.9; Analysis 4.10).

For the newborns

4.11 - 4.13 High and low birthweight

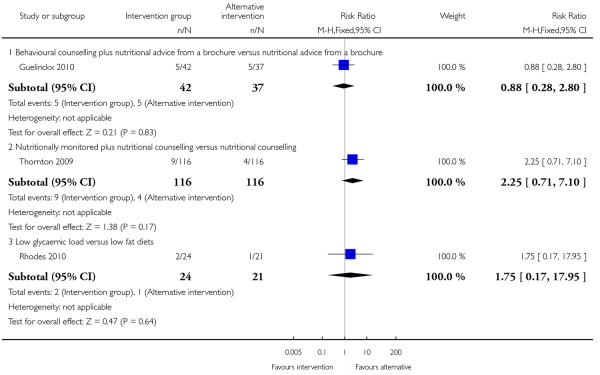

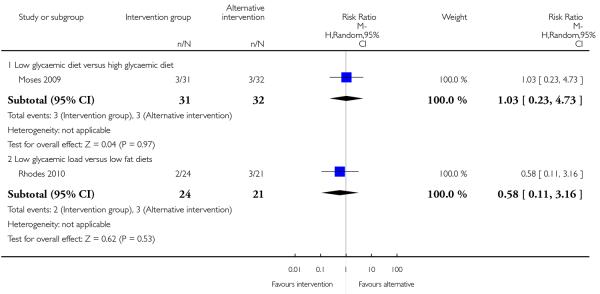

Three studies looked at infant birthweight above 4000 gm; there was no evidence significant differences between any of the two interventions compared (nutrition brochure with or without counselling RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.80; nutritional counselling with or without monitoring RR 2.25, 95% CI 0.71 to 7.10; low GI versus low fat diet RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.17 to 17.95) (Analysis 4.11). Two additional studies reported on the number of babies with birthweight above the 90th centile. Again, there was no clear difference between alternative intervention groups: low versus high glycaemic diet RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.23 to 4.73; low glycaemic load diet versus low fat diet RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.16) (Analysis 4.12).

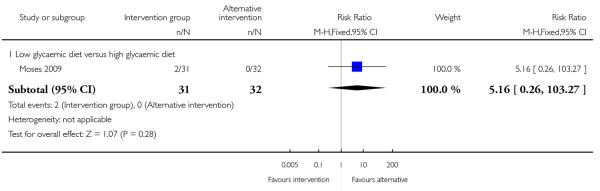

One study comparing high versus low glycaemic diet reported on the number of babies with birthweight below the 10th centile. There was no strong evidence that any particular intervention was associated with lower infant birthweight (RR 5.16, 95% CI 0.26 to 103.27) (Analysis 4.13).

Complication related to macrosomia

No trials in this comparison reported on this outcome.

Long-term health outcomes

4.14 Maternal weight retention

A single trial with 232 women reported on mean maternal weight retention in high-risk groups (Thornton 2009). This study suggested that the addition of nutritional monitoring to a counselling intervention led to considerably less weight retention (MD −13.71, 95% CI −14.48 to −12.94) (Analysis 4.14).

Appetite suppressant drugs versus placebo (two trials)

Two trials examined the effects of diethylpropion hydrochloride (appetite suppressant drug) versus placebo (Boileau 1968; Silverman 1971); the results from these trials were not reported in a way that allowed us to include them in the analysis. The results are set out in additional tables (Table 4). Both of these studies are now more than 40 years old and we are not aware that these drugs are now used in obstetric practice.

Table 4. Weight change during therapy (use of an appetite suppressant).

| Study | Diethylpropion hydrochloride | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Duration of therapy (weeks) | Average weight change (lb.) | n | Duration of therapy (weeks) | Average weight change (lb.) | |

| Silverman 1971 | 28 | 10.9 | 6.97 | 9 | 10.9 | 8.78 |

| Boileau 1968 | 52 | 13.0 | 1.2 | 53 | 12.9 | 7.0 |

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Overall, results from this review were mainly not statistically significant, and where there did appear to be differences between intervention and control groups, results were not consistent. For many outcomes only one or two studies reported results. For many outcomes studies did not have sufficient statistical power to detect differences between groups.

For those trials recruiting pregnant women from general clinic populations (which may have included some overweight and obese women and women with other risk factors), findings were inconsistent. Only four trials (examining three different types of interventions) reported on the number of women gaining excessive weight during pregnancy; only one of the three intervention types (behavioural counselling) was associated with a positive treatment effect. Mean weight gain in pregnancy was reported for six different types of interventions; three (behavioural counselling, an intensive exercise intervention and a combined diet and exercise intervention) seemed to have positive effects. Two types of interventions (a single study of each intervention) were associated with women being less likely to retain weight in the postpartum period. For other outcomes (often reported in single studies), there was no clear evidence of differences between groups (low maternal weight gain, preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, high and low infant birthweight and birth and infant complications). There was some evidence from single studies that interventions may have a positive effect on reported behaviour (e.g. activity scores); although without blinding such results are difficult to interpret.

Where two or more alternative interventions were compared in women recruited from general clinic populations results were from single studies. The finding indicated that a low glycaemic diet with exercise was more effective in reducing pregnancy weight gain than a high glycaemic diet with exercise. A study examining different patterns of exercise during pregnancy reported that low intensity exercise in early pregnancy followed by high intensity exercise later in pregnancy was associated with lower weight gain than other patterns of exercise. For the newborn outcomes, a single study reported that a low glycaemic diet was associated with a lower number of babies with birthweight above the 90th centile for gestational age than a high glycaemic diet. However, overall there was very little evidence about the relative effects of alternative types of interventions on most of the review outcomes; outcomes were either not reported or differences between groups were not statistically significant.

For studies recruiting women or reporting results for women in high-risk groups (recruiting only women that were overweight or obese or with other risk factors), results were also inconsistent and for most outcomes interventions were not associated with statistically significant positive effects. Four trials reported on excessive weight gain but no intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the number of women gaining excessive weight. One of seven different interventions was associated with a reduction in mean weight gain (this intervention involved weight monitoring, continuity of care and counselling), for the remaining six interventions there were no significant differences between groups. For reported behaviour change there was some evidence that women in intervention groups reported lower energy intake. For other outcomes there was no strong evidence of differences between control and intervention groups. Where alternative interventions were compared, only one trial reported on excessive weight gain with no positive effect. A significant effect on lower mean weight gain was found only in one (addition of nutrition monitoring to a counselling intervention) of four alternative comparisons; this intervention was also associated with women being less likely to retain weight in the postpartum period.There was no clear evidence that one type of intervention was better than another for other outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Almost all of the included studies were carried out in developed countries and it is not clear that the results are applicable in other contexts. The transfer of an intervention from one setting to another may reduce its effectiveness. There was considerable variation in the nature of interventions as well as in outcomes reported among studies. Therefore, although we have included data from 27 studies in the review, there were limited data for most types of interventions and outcomes were measured in different ways, so only few of the results could be combined, especially for the main outcome of interest. The overall completeness of evidence in this review is therefore too limited to allow us to reach any strong conclusions or to generalise.

Quality of the evidence

We included 28 studies with 27 studies involving 3964 women contributing data to the analyses. Seventeen out of 27 included studies contributing data were assessed as being at low risk of bias for generation of the randomisation sequence and twelve used methods that we judged were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment (see Figure 1). Achieving blinding for most interventions would be difficult, and lack of blinding may have had an impact on some outcomes (e.g. self-report of activity levels and other behavioural outcomes).

Potential biases in the review process

We took a number of steps to minimise bias in the review process. We strictly followed the process recommended by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Review Group. We were able to obtain all relevant studies identified from search results. We independently reviewed all potentially relevant studies and resolved disagreement by discussion.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two recent systematic reviews (Ronnberg 2010; Skouteris 2010), which identified the effects of interventions to reduce excessive weight gain during pregnancy, concluded similar results to our review: that none of the trials showed any significant difference in proportion of excessive weight gain, and that there was inconsistency in the results to reduce gestational weight gain between the treatment and control groups. However, these two reviews included only studies comparing interventions with standard maternity care, and included not only RCTs, but also non-RCTs.

We identified two other systematic reviews of RCTs. The review by Kuhlmann 2008 assessed weight-management interventions for pregnant or postpartum women. Only one study conducted among pregnant women was included in this review. The other RCT review, by Dodd 2008 (updated by Dodd 2010b), identified the risks and benefits of dietary and lifestyle interventions to limit weight gain during pregnancy in overweight and obese women. The reviews reported similar results to our review: that there were no statistically significant differences identified between the intervention and standard care groups for maternal or infant health outcomes.

One Cochrane review showed that energy or protein restriction advice for overweight pregnant women significantly reduced weekly maternal weight gain (Kramer 2003), but our review found that there was no significant difference in mean weight gain between energy restriction counselling and standard care.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The results of the review were inconsistent. Some interventions for general population groups had promising results but none of the interventions were effective in preventing excessive weight gain in high-risk groups. Similarly, for the mean weight gain outcome, some diet and or exercise interventions appeared to be effective compared with routine care although only one of seven different interventions achieved positive effect in high-risk groups. Interventions did not seem to have any positive (or negative) effect on other maternal and infant outcomes. However, most results were from only one or two studies and there is not enough evidence to recommend any particular intervention for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy. In addition, methodological limitations among the included studies and the observed effect sizes were generally small, therefore, caution is needed in applying these results.

Implications for research

There is a need to conduct high quality RCTs with adequate sample sizes to evaluate the effectiveness of potential interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy. In addition, not only should total weight gain be measured, but also the proportion of women who have weight gain above and below the recommendations. In addition, it would be interesting to examine women’s compliance in programmes to restrict weight gain. Furthermore, the effectiveness of interventions for women with non-Western lifestyles should also be assessed.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy

A large proportion of women gain more weight than is recommended during pregnancy. Excessive weight gain increases the risk of complications for both the mother and her infant. These include miscarriage, development of diabetes mellitus or pregnancy-induced hypertension, a high birthweight infant and the likelihood of caesarean section. We reviewed 28 randomised controlled studies that involving more than 3000 women, mostly from developed countries, to assess the effectiveness of interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy (27 of the studies with 3964 women contributed data to the analyses). Results on preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy were limited to studies that included this as an outcome. There were five interventions in the general population and two interventions in high-risk groups which seemed to reduce average weight gain during pregnancy. Few studies looked at excessive weight gain during pregnancy and only one of the interventions they used resulted in significantly reduced rates of excessive weight gain. It is not appropriate for us to recommend any one intervention for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy because most of the studies identified were of poor quality and the effects of the interventions were generally small. There is an urgent need for more well-designed studies with adequate sample sizes to be able to recommend effective interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the staff of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group for assistance with searching references and providing technical guidance.

As part of the prepublication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team) and the Group’s Statistical Adviser.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

Thai Cochrane Network, Thailand.

Thailand Research Fund (Senior Research Scholar), Thailand.

NIHR NHS, UK.

TD is supported by the NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme grant scheme award for NHS-prioritised centrally managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS 10/4001/02

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, set in resident obstetric clinic in Charlotte, North Carolina, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: prenatal care established at 6-16 weeks of gestation, age 18-49 years, all prenatal care received at the Resident Obstetrics Clinic, English-speaking, Spanish-speaking, or both, and singleton pregnancy Exclusion criteria: BMI higher than 40, pre-existing diabetes, untreated thyroid disease, or hypertension requiring medication or other medical conditions that might affect body weight, delivery at institution other than Carolinas Medical Center Main, pregnancy ending in premature delivery (less than 37 weeks), and limited prenatal care (fewer than 4 visits) |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 57) received consistent program of dietary and lifestyle counselling. At the initial visit, participants met with a registered dietician to receive a standardised counselling session, including information on pregnancy-specific dietary and lifestyle choices. The counselling consisted of recommendations for a patient-focused caloric value divided in a 40% CHO, 30% protein, and 30% fat fashion. Patients were instructed to engage in moderate-intensity exercise at least 3 times per week and preferably 5 times per week. They also received information on the appropriate weight gain during pregnancy using the IOM guidelines. Each participant met with the dietician only at the time of enrolment. At each routine obstetrical appointment, the healthcare provider informed the participant whether her weight gain was at the appropriate level. If her weight gain was not within the IOM guidelines, the participant’s diet and exercise regimen were reviewed and she was advised on increasing or decreasing her intake and increasing or decreasing exercise Control group (n = 43) received routine prenatal care, including an initial physical examination and history, routine laboratory tests, and routine visits per American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards. The only counselling on diet and exercise during pregnancy was that included in a standard prenatal booklet. The healthcare provider did not counsel the participant regarding any changes in diet or lifestyle |

|

| Outcomes | Weight gain, caesarean delivery, pre-eclampsia, shoulder dystocia Total weight gain was defined as weight just before delivery minus prepregnancy weight |

|

| Notes | Age (intervention, control): 26.7 ± 6.0, 26.4 ± 5.0. Enrollment gestational age (intervention, control): 13.7 ± 3.6, 13.6 ±.2 weeks Prepregnancy BMI: 25.5 ± 6.0, 25.6 ± 5.1 kg/m2. BMI category, n (intervention, control)

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was performed using computer-generated random allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Study allocation was concealed in numbered and sealed opaque envelopes |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | No loss to follow-up reported. Trial authors stated that they had carried out an intention-to-treat analysis: data were analysed for participants according to their randomly-allocated group; all participants were included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The outcomes reported as in the published protocol. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Demographic data were similar. Age, prepregnancy weight, height and BMI were not different at baseline No other obvious bias. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, set in Hospital de Fuen-labrada, Madrid, Spain | |

| Participants | 80 women randomised. Inclusion criteria: healthy pregnant women (age, 23-38 years), had uncomplicated, singleton pregnancies Exclusion criteria: any type of absolute obstetric contraindication to aerobic exercise during pregnancy, which included other contraindications that the authors considered to have a relevant influence on maternal perception of health: significant heart disease, restrictive lung disease, incompetent cervix/cerclage, multiple gestation, risk of premature labour, pre-eclampsia/pregnancy-induced hypertension, thrombophlebitis, recent pulmonary embolism (last 5 years), acquired infectious disease, retarded intrauterine development, serious blood disease, and/or absence of prenatal care |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: (40 randomised) moderate physical activity, included a total of 35- to 45-minute weekly sessions 3 days each week from the start of the pregnancy (weeks 6-9) to the end of the 3rd trimester (weeks 38-39), an average of 85 training sessions, exercise intensity was light-to-moderate. Exercise was supervised by a fitness specialist and was in groups of 10-12 women Control group: (40 randomised) routine care. |

|

| Outcomes | Weight gain, caesarean, birthweight < 4000 gm, birthweight > 4000 gm | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomly assigned by use of a random number table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not mentioned. It would be difficult to blind women and staff to this type of intervention. It is not clear how lack of blinding would impact on the outcomes measured |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | 80 women were randomised and 67 were analysed; 34 in the exercise group, 33 in the control group. Reason of discontinued were similar in both groups |