Abstract

Background

Use of topical NSAIDs to treat acute musculoskeletal conditions is widely accepted in some parts of the world, but not in others. Their main attraction is their potential to provide pain relief without associated systemic adverse events.

Objectives

To review the evidence from randomised, double-blind, controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of topically applied NSAIDs in acute pain.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, and our own in-house database to December 2009. We sought unpublished studies by asking personal contacts and searching on-line clinical trial registers and manufacturers web sites.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, double-blind, active or placebo (inert carrier)-controlled trials in which treatments were administered to adult patients with acute pain resulting from strains, sprains or sports or overuse-type injuries (twisted ankle, for instance). There had to be at least 10 participants in each treatment arm, with application of treatment at least once daily.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and validity, and extracted data. Numbers of participants achieving each outcome were used to calculate relative risk and numbers needed to treat (NNT) or harm (NNH) compared to placebo or other active treatment.

Main results

Forty-seven studies were included; most compared topical NSAIDs in the form of a gel, spray, or cream with a similar placebo, with 3455 participants in the overall analysis of efficacy. For all topical NSAIDs combined, compared with placebo, the number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) for clinical success, equivalent to 50% pain relief, was 4.5 (3.9 to 5.3) for treatment periods of 6 to 14 days. Topical diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and piroxicam were of similar efficacy, but indomethacin and benzydamine were not significantly better than placebo. Local skin reactions were generally mild and transient, and did not differ from placebo. There were very few systemic adverse events or withdrawals due to adverse events. There were insufficient data to reliably compare individual topical NSAIDs with each other or the same oral NSAID.

Authors’ conclusions

Topical NSAIDs can provide good levels of pain relief, without the systemic adverse events associated with oral NSAIDs, when used to treat acute musculoskeletal conditions.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acute Disease; Administration, Topical; Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal [* administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Athletic Injuries [drug therapy]; Pain [* drug therapy]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sprains and Strains [drug therapy]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief remain one of the more controversial subjects in analgesic practice. In some parts of the world (much of Western Europe, for instance) they have been available for many years, are widely available without prescription, widely advertised, used extensively, and evidence for their use is considered adequate. In other parts of the world they are regarded as little more than placebo, with any apparent effect attributed to the process of rubbing at the site of the affected area. In some places (the United States, for instance) their use was almost unknown until recently. In England 3.8 million prescriptions for topical NSAIDs were dispensed in 2009 (PACT 2009).

There is good evidence for the efficacy of oral NSAIDs in acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain (Mason 2004a; Mason 2004b; Moore 1998a). In the US the Food and Drug Administration licensed topical nonsteroidal products in 2007, and in England the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended topical therapies as first line treatment in its guidelines for osteoarthritis in 2008 (NICE 2008). An earlier review of topical analgesics covers not only clinical trials, but also studies investigating the underlying science to explain biological plausibility (Bandolier 2005).

Description of the condition

Acute pain is usually defined as pain of less than three months’ duration. It is often associated with injury, including trauma, surgery, musculoskeletal injuries like strains, sprains and over-use injuries, or soft tissue injuries like muscle soreness or cramps.

Description of the intervention

Clinicians prescribe NSAIDs on a routine basis for a range of mild to moderate pain. NSAIDs are the most commonly prescribed analgesic medications worldwide, and their efficacy for treating acute pain has been well demonstrated (Moore 2003). They reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase), the enzyme mediating production of prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 (Fitzgerald 2001). Prostagalandins mediate a variety of physiological functions such as maintenance of the gastric mucosal barrier, regulation of renal blood flow, and regulation of endothelial tone. They also play an important role in inflammatory and nociceptive processes. However, relatively little is known about the mechanism of action of this class of compounds aside from their ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase-dependent prostanoid formation (Hawkey 1999).

NSAIDs taken orally or intravenously are transported to all parts of the body in the blood, and relatively high blood concentrations are needed to achieve effective tissue concentrations at the site of the pain and inflammation. These high concentrations throughout the body can give rise to a number of unpleasant (e.g. dyspepsia) and potentially serious (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding) adverse events.

Topical NSAIDs

Topical NSAIDs are formulated for direct application to the painful site, and to produce a local pain-relieving effect while avoiding body-wide distribution of the drug at physiologically active levels. This method of application (dosing) necessarily limits their use to more superficial painful conditions such as sprains, strains, and muscle or tendon soreness. They would not, for example, be indicated for deep visceral pain or headaches. They are also not appropriate for use on broken skin, so would not be used on open wounds (accidental or surgical).

How the intervention might work

For a topical formulation to be effective, it must first penetrate the skin. Only when the drug has entered the lower layers of the skin can it be absorbed by blood and transported to the site of action, or penetrate deeper into areas where inflammation occurs. Individual drugs have different degrees of penetration. A balance between lipid and aqueous solubility is needed to optimise penetration, and use of prodrug esters has been suggested as a way of enhancing permeability. Formulation is also crucial to good skin penetration. Experiments with artificial membranes or human epidermis suggest that creams are generally less effective than gels or sprays, but newer formulations such as microemulsions may have greater potential.

Once the drug has reached the site of action, it must be present at a sufficiently high concentration to inhibit cox enzymes and produce pain relief. It is probable that topical NSAIDs exert their action both by local reduction of symptoms arising from periarticular structures, and by systemic delivery to intracapsular structures. Tissue levels of NSAIDs applied topically certainly reach levels high enough to inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (Bandolier 2005). Plasma concentrations found after topical administration, however, are only a fraction (usually much less than 5%) of the levels found in plasma following oral administration. Topical application can potentially limit systemic adverse events by increasing local effects, and minimizing systemic concentrations of the drug. We know that upper gastrointestinal bleeding is low with chronic use of topical NSAIDs (Evans 1995), but have no certain knowledge of lower effects on heart failure, or renal failure, both of which are associated with oral NSAID use.

Why it is important to do this review

New versions of topical NSAIDs are becoming available, with more and better trials being performed. An updated review of evidence for their efficacy is needed for commissioners (purchasers of healthcare), prescribers and consumers to make informed choices about their use. Many trials of newer preparations have yet to be published, and are not available for inclusion in this review.

This is one of a series of reviews being conducted on topical analgesics, including NSAIDs in chronic pain (Derry 2008), topical rubefacients (Matthews 2009) and topical capsaicin (Derry 2009).

OBJECTIVES

To review the evidence from randomised, double-blind, controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of topically applied NSAIDs in acute pain (mainly strains and sprains, but excluding postsurgical pain where topical NSAIDs are not used). Topical NSAIDs will be compared with topical placebos, with differences between individual NSAIDs investigated primarily by indirect comparison, since few, if any, studies examine two topical preparations head to head (Mason 2004a). In addition, individual any NSAID will be compared with any oral NSAID.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled double-blind trials comparing topical NSAIDs with placebo (inert carrier) or other active treatment for acute pain, with at least ten participants per treatment arm and outcomes close to seven days (minimum three days). Studies published only as abstracts or studying experimentally induced pain were excluded.

Types of participants

Adult participants (16 years or more) with acute pain of at least moderate intensity resulting mainly from strains, sprains or sports injuries. Typically for sports injuries, the injury would have occurred within 24 or 48 hours.

Types of interventions

Included studies had at least one arm using a topical NSAID, and a comparator arm using placebo (inert carrier) or other active treatment. The topical NSAID had to be applied at least once daily. Salicylates are no longer classified as topical NSAIDs and is not included in this review.

Types of outcome measures

Information was sought on participant characteristics: age, sex, and condition treated.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was “clinical success”, defined as a 50% reduction in pain or equivalent measure, such as a “very good” or “excellent” global assessment of treatment, or “none” or “slight” pain on rest or movement, measured on a categorical scale (Moore 1998a). The following hierarchy of outcomes, in order of preference, was used to extract data for the primary outcome:

patient reported reduction in pain of at least 50%;

patient reported global assessment of treatment;

pain on movement;

pain on rest or spontaneous pain;

undefined “improvement”.

Only patient reported outcomes were used. Physician or investigator reported outcomes of efficacy were not used.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes sought were:

numbers of patients with adverse events: local and systemic;

numbers of withdrawals: all cause, lack of efficacy, and adverse events.

We anticipated that outcomes would be reported after different durations of treatment, and extracted data reported as close to seven days as possible, with a minimum of three days. Where outcomes were reported after longer durations of treatment these would also be extracted. We also anticipated that reporting of adverse events would vary between studies with regard to the terminology used, method of ascertainment, and categories reported (e.g. occurring in at least 5% of participants or where there is a statistically significant difference between treatment groups). Care was taken to identify these details where relevant.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following databases were searched:

MEDLINE (via Ovid), December 2009.

EMBASE (via Ovid), December 2009.

Cochrane CENTRAL, Issue 4, 2009.

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 1 for the search strategy for MEDLINE (via OVID),Appendix 2 for the search strategy for EMBASE, and Appendix 3 for the search strategy for CENTRAL.

Reference lists of review articles and included studies were searched. Manufacturers have previously been asked for details of unpublished studies. No new unpublished studies in acute musculoskeletal conditions were identified from manufacturers’ web sites or www.ClinTrials.gov, and discussions with pharmaceutical companies led to no new unpublished studies being made available. There was no language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts of studies identified by the searches were reviewed on-screen to eliminate those that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria. Full reports of the remaining studies were obtained to determine inclusion in the review. Cross-over trials were considered only if data from the first treatment period was reported separately. Studies in oral, ocular or buccal diseases were excluded.

Data extraction and management

Review authors were not blinded to the authors’ names and institutions, journal of publication, or study results at any stage of the review. Two review authors independently selected the studies for inclusion, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Information on participants, interventions, and outcomes from the original reports was abstracted into a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for meta-analysis was entered into RevMan 5.0 by one review author and checked by another.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Included studies were assessed for methodological quality using a five-point scale (Jadad 1996b) that considers randomisation, blinding, and study withdrawals and dropouts. Trial validity was assessed using a 16-point scale (Smith 2000). The scores for each study are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table. ‘Risk of bias’ tables were completed for randomisation, allocation concealment, and blinding.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative risk (or ‘risk ratio’, RR) were used to establish statistical difference. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) and pooled percentages were used as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted randomisation to individual patient only.

Assessment of heterogeneity

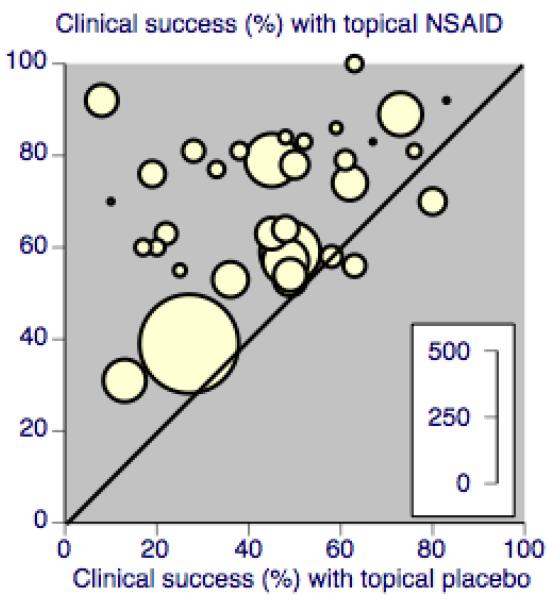

Heterogeneity was examined visually using L’Abbé plots (L’Abbe 1987).

Data synthesis

Intention-to-treat analyses were performed wherever possible, using participants randomised, receiving at least one dose of treatment, and providing data for at least one post-baseline assessment. Effect sizes were calculated and data combined for analysis only for comparisons and outcomes where there were at least two studies and 200 participants (Moore 1998b). When two active treatment arms were compared with a placebo arm, care was taken to avoid double counting of participants in the placebo arm: if both active groups contributed to an analysis, the placebo group was split between them. Relative benefit and relative risk estimates with 95% CIs were calculated using the fixed-effect model (Morris 1995). A statistically significant benefit of topical NSAID over control was assumed when the lower limit of the 95% CI of the relative benefit was greater than one. A statistically significant benefit of control over active treatment was assumed when the upper limit of the 95% CI is less than the number one. Number needed to treat (NNT) with 95% CIs was calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). Number needed to treat to harm (NNH) and relative risk (RR) were calculated for these outcomes in the same way as for NNTs and relative benefit (RB).

Statistically significant differences between NNTs for different topical NSAIDs were tested using the z test (Tramer 1997), where there was sufficient data to do so, and where the clinical trials were sufficiently similar in types of patient, outcome, and duration to make such comparisons sensible.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome for topical agent versus placebo were planned for:

high versus low quality (< 3 versus 3 or more) and validity (< 9 versus 9 or more) scores;

study size (< 40 versus 40 or more);

outcome (undefined “improvement” versus others);

differences between individual NSAIDs;

time of assessment of primary outcome.

RESULTS

Description of studies

A total of 47 studies are included in this review. Thirty-one compared a topical NSAID to placebo, 12 a topical NSAID to an active comparator (a different topical NSAID, an oral NSAID, or the same topical NSAID in a different formulation), and four had both placebo and active comparators. In total 3288 participants were treated with a topical NSAID, 2004 with placebo, and 220 with an oral NSAID. Topical NSAIDs used were benzydamine, diclofenac, etofenamate, felbinac, fentiazac, flunoxaprophen, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, lysine cloxinate, meclofenamic acid, naproxen, niflumic acid, and piroxicam. They were applied as creams, gels, sprays, foams or plasters (patches). Topical placebos were the inert carriers, without the active NSAID. Oral NSAIDs used were ibuprofen and indomethacin, given as tablets and capsules respectively.

Most studies enrolled participants who had sprains, strains and contusions, usually as a result of sports injuries, and treatment was started within a few hours or days. Other studies enrolled participants with overuse-type injuries, such as tendinitis and acute low back pain, where pain had been present for days or weeks, but less than three months.

Participants were treated for at least six days, and up to three weeks, with most studies lasting seven to 14 days. Participants were usually assessed in clinic at intervals during treatment, and sometimes also at home using daily patient diaries. We used outcomes closest to seven days because many of these injuries are self-limiting, with differences between active treatment and placebo diminished or lost after longer intervals.

Nearly all studies reported group mean changes (e.g. pain, physical function) as their primary outcomes, but dichotomous outcomes suitable for a “responder analysis” were available in most. The definition of response, however, varied both in the parameter measured (e.g. pain, pain on movement, patient global evaluation of treatment), and in the scale used to measure it (e.g. 3, 4, or 5 point scale for patient global evaluation).

Details of included studies are in the ‘Characteristics of included studies table.

Twenty-five studies were excluded after obtaining the full paper. Details are in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table.

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies were randomised and double blind. One study (Sinneger 1981) scored 2/5, 19 scored 3/5, 20 scored 4/5, and seven scored 5/5 for methodological quality using the Oxford Quality Scale. Points were lost mainly for failure to adequately report details of randomisation and blinding. Three studies (Haig 1986; Jenoure 1997; Sinneger 1981) did not report on with-drawals. Studies scoring three or more are at low risk of methodological bias. A breakdown of the scores for individual studies can be seen in the ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table.

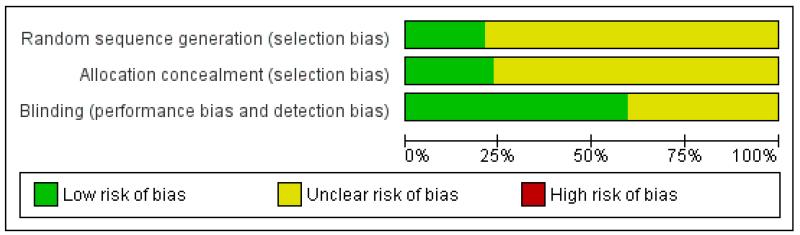

No studies were identified as being at high risk of methodological bias using the ‘Risk of bias’ table (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Validity of included studies

Five studies (Billigmann 1996; Gallacchi 1990; Gualdi 1987; Sinneger 1981; Tonutti 1994) scored ≤ 8/16 using the Oxford Pain Validity Scale, and 42 scored ≥ 9/16. Scores for individual studies can be seen in the ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table. Studies scoring at least nine are more likely to provide valid results (Smith 2000).

Only two studies (Mazieres 2005a; Mazieres 2005b) clearly reported on how missing data were handled. In these cases the last observation was carried forward.

Effects of interventions

1. Topical NSAID versus placebo

Participants with clinical success

All topical NSAIDs versus placebo

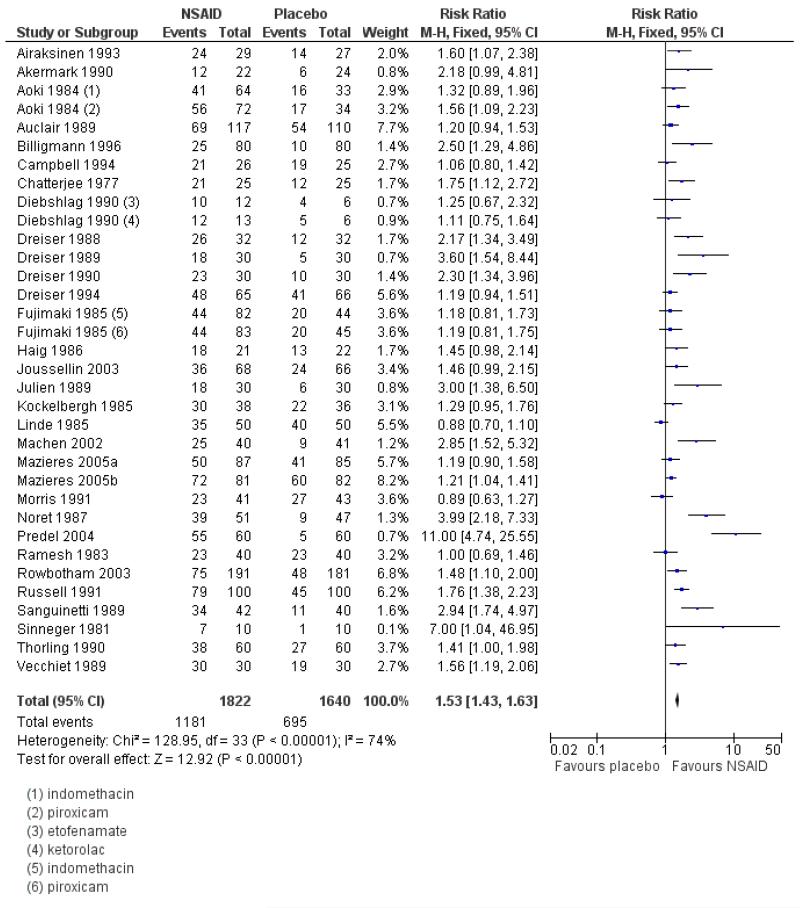

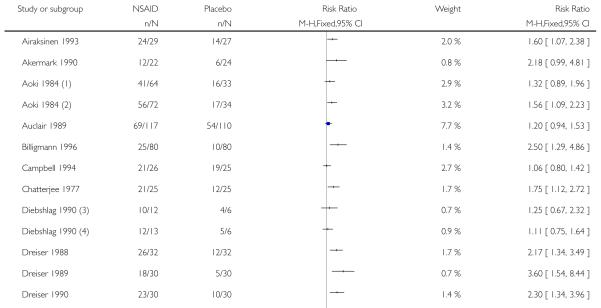

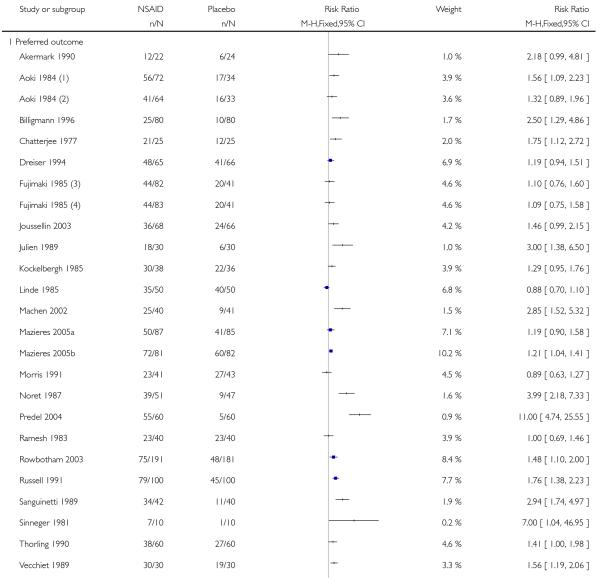

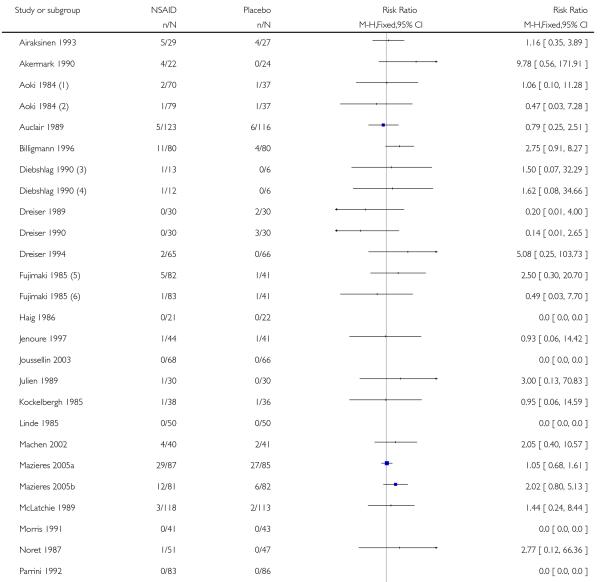

Thirty-one studies contributed to this analysis, of which three (Aoki 1984; Diebshlag 1990; Fujimaki 1985) had two active treatment arms. In total, 1822 participants were treated with a topical NSAID and 1633 with placebo (Figure 2).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 65% (1181/1822, range 31% to 100%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 43% (695/1633, range 8% to 83%);

The relative benefit (RB) of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6);

The number-needed-to treat-to-benefit (NNT) for successful treatment was 4.5 (3.9 to 5.3). For every four or five participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Excluding the three studies using benzydamine (Chatterjee 1977; Haig 1986; Linde 1985) did not affect the result: RR 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7), NNT 4.3 (3.8 to 5.1).

Figure 2. Forest plot of comparison: 1 All topical NSAIDs vs placebo, outcome: 1.1 Clinical success.

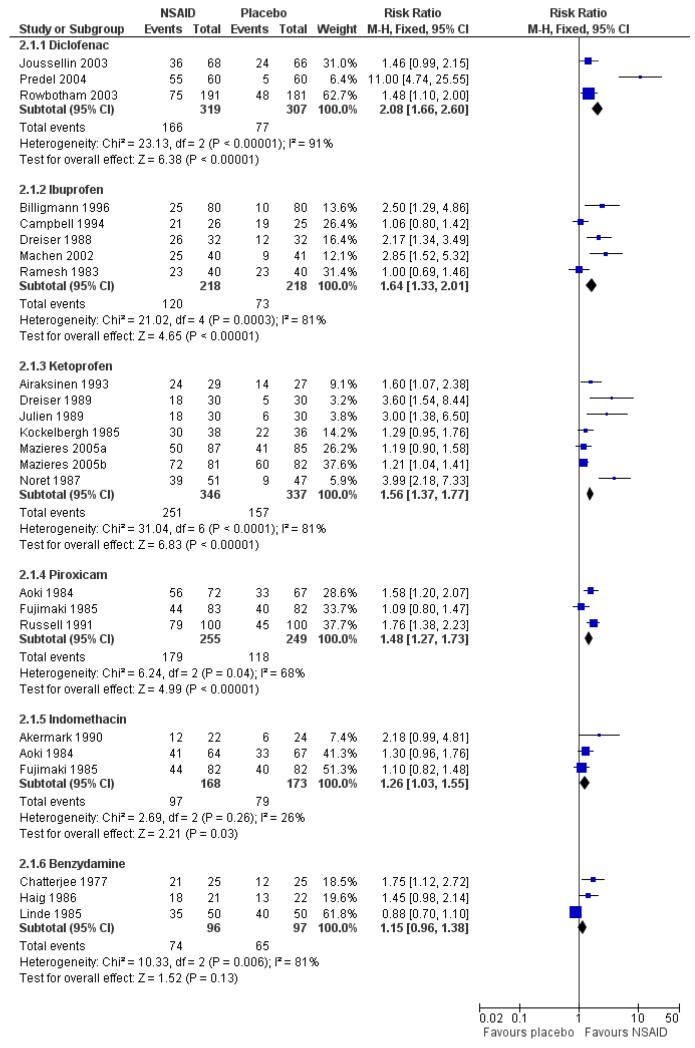

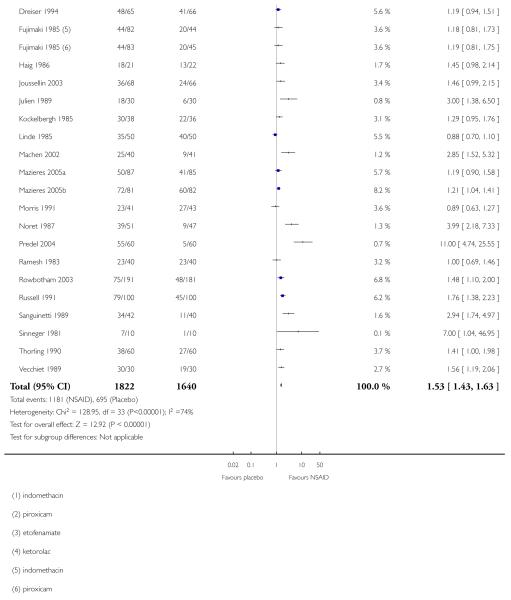

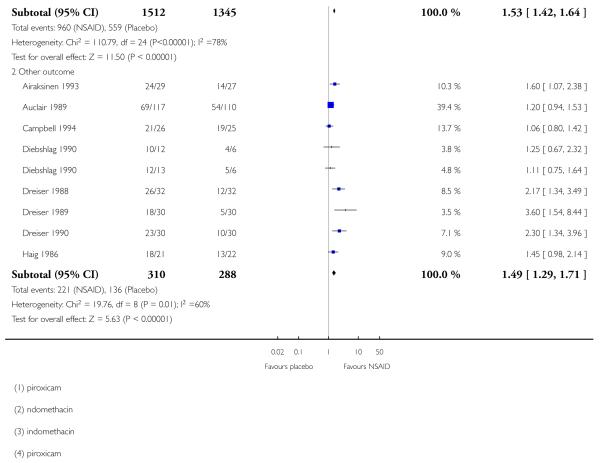

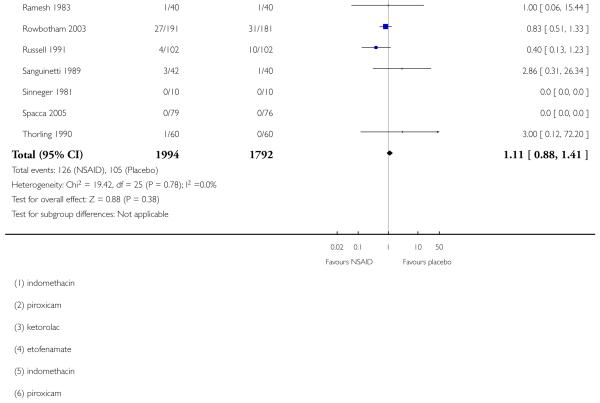

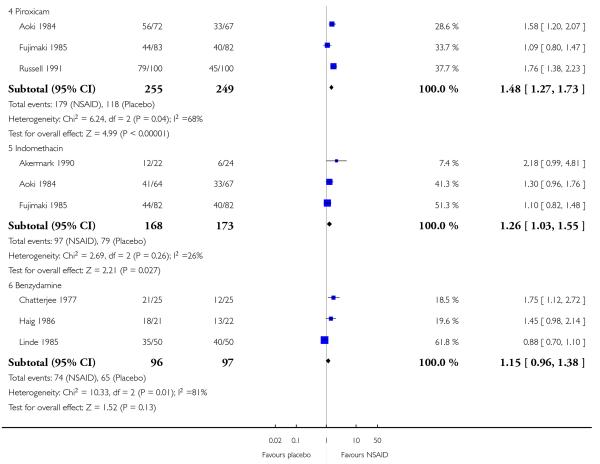

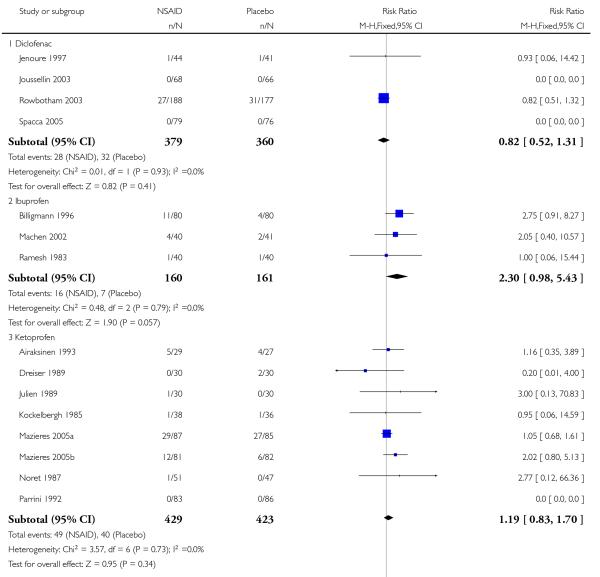

Topical diclofenac versus placebo

Three studies contributed to this analysis (Joussellin 2003; Predel 2004; Rowbotham 2003). A total of 319 participants were treated with topical diclofenac, and 307 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical diclofenac was 52% (166/319, range 39% to 92%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 25% (77/307, range 8% to 36%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6);

The NNT for successful treatment was 3.7 (2.9 to 5.1). For every four participants treated with topical diclofenac, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Topical ibuprofen versus placebo

Five studies contributed to this analysis (Billigmann 1996; Campbell 1994; Dreiser 1988; Machen 2002; Ramesh 1983). A total of 218 participants were treated with topical ibuprofen, and 218 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical ibuprofen was 55% (120/218, range 31% to 81%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 33% (73/218, range 13% to 76%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0);

The NNT for successful treatment was 4.6 (3.3 to 8.0). For every five participants treated with topical ibuprofen, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Topical ketoprofen versus placebo

Seven studies contributed to this analysis (Airaksinen 1993; Dreiser 1989; Julien 1989; Kockelbergh 1985; Mazieres 2005a; Mazieres 2005b; Noret 1987). A total of 346 participants were treated with topical ketoprofen, and 337 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical ketoprofen was 73% (251/346, range 57% to 89%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 47% (157/337, range 17% to 73%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8);

The NNT for successful treatment was 3.9 (3.0 to 5.3). For every four participants treated with topical ketoprofen, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Topical piroxicam versus placebo

Three studies contributed to this analysis (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985; Russell 1991). A total of 255 participants were treated with topical piroxicam, and 249 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical piroxicam was 68% (179/255, range 53% to 79%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 47% (118/249, range 45% to 49%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7);

The NNT for successful treatment was 4.4 (3.2 to 6.9). For every four participants treated with topical piroxicam, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Topical indomethacin vs placebo

Two studies contributed to this analysis (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985). A total of 146 participants were treated with topical indomethacin and 149 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical indomethacin was 58% (97/158, range 54% to 64%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 46% (79/173, range 25% to 49%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.3 (1.03 to 1.6).

The NNT for successful treatment was 8.3 (4.4 to 65). For every eight participants treated with topical indomethacin, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Topical benzydamine versus placebo

Three studies contributed to this analysis (Chatterjee 1977; Haig 1986; Linde 1985). A total of 96 participants were treated with topical indomethacin and 97 with placebo (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical benzydamine was 77% (74/96, range 70% to 86%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 67% (65/97, range 48% to 80%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.2 (0.96 to 1.4). There was no statistically significant difference between treatments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 2 Individual NSAID vs placebo, outcome: 2.1 Clinical success.

Summary of results A: Participants with clinical success.

| Comparison | Studies | Participants | NSAID (%) | Placebo (%) | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All NSAIDs | 31 | 3455 | 65 | 43 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 4.5 (3.9 to 5.3) |

| Diclofenac | 3 | 626 | 52 | 25 | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6) | 3.7 (2.9 to 5.1) |

| Ibuprofen | 5 | 436 | 55 | 33 | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | 4.6 (3.3 to 8.0) |

| Ketoprofen | 7 | 683 | 73 | 47 | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 3.9 (3.0 to 5.3) |

| Piroxicam | 3 | 504 | 70 | 47 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 4.4 (3.2 to 6.9) |

| Indomethacin | 3 | 341 | 58 | 46 | 1.3 (1.03 to 1.6) | 8.3 (4.4 to 65) |

| Benzydamine | 3 | 193 | 77 | 67 | 1.2 (0.96 to 1.4) | not calculated |

Sensitivity analyses of primary outcome

Methodological quality and validity

Only one study (Sinneger 1981) scored ≤ 3 for methodological quality and ≤ 8 for study validity, so this analysis could not be carried out.

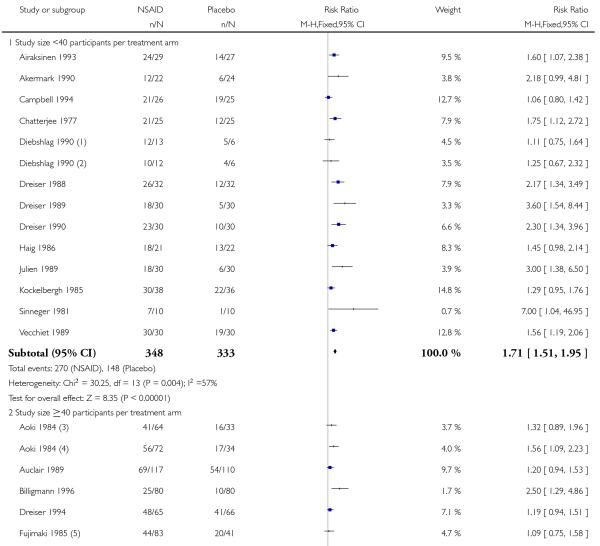

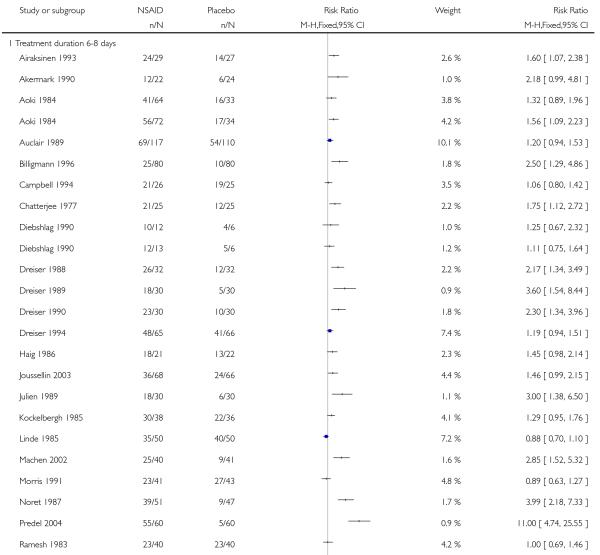

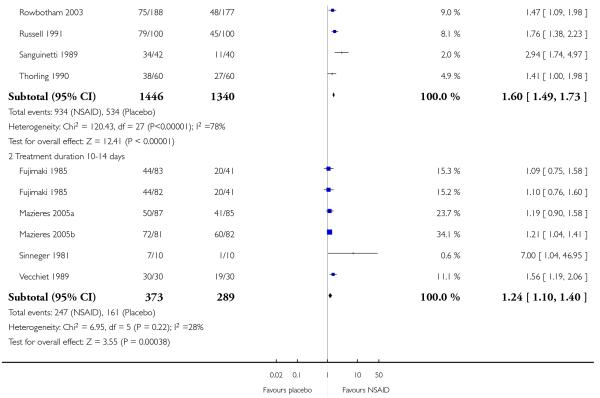

Study size

Fewer than 40 participants per treatment arm

Thirteen studies contributed to this analysis (Airaksinen 1993; Akermark 1990; Campbell 1994; Chatterjee 1977; Diebshlag 1990; Dreiser 1988; Dreiser 1989; Dreiser 1990; Haig 1986; Julien 1989; Kockelbergh 1985; Sinneger 1981; Vecchiet 1989), of which one (Diebshlag 1990) had two treatment arms. In total, 348 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 333 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 78% (270/348, range 55% to 100%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 44% (148/333, range 10% to 83%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0);

The NNT for successful treatment was 3.0 (2.5 to 3.8). For every three participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

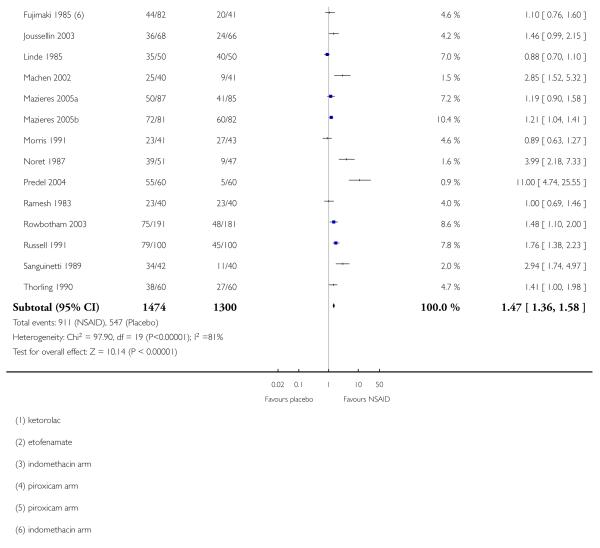

Forty or more participants per treatment arm

Eighteen studies contributed to this analysis (Aoki 1984; Auclair 1989; Billigmann 1996; Dreiser 1994; Joussellin 2003; Fujimaki 1985; Linde 1985; Machen 2002; Mazieres 2005a; Mazieres 2005b; Morris 1991; Noret 1987; Predel 2004; Ramesh 1983; Rowbotham 2003; Russell 1991; Sanguinetti 1989; Thorling 1990), of which two (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985) had two treatment arms. In total 1474 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 1300 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 62% (911/1474, range 31% to 92%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 42% (547/1300, range 8% to 80%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6);

The NNT for successful treatment was 5.1 (4.3 to 6.2). For every five participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Further analysis confirmed that studies with fewer than 40 participants per treatment arm gave a better estimate of efficacy (lower NNT) than those with 40 or more participants (z = 3.3653, P = < 0.00097).

Outcomes

Preferred outcomes (protocol-defined in methods)

Twenty-three studies contributed to this analysis, of which two (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985) had two treatment arms. In total, 1512 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 1345 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 63% (960/1512, range 31% to 100%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 42% (559/1345, range 8% to 80%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6);

The NNT for successful treatment was 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5). For every five participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Undefined improvement

Eight studies contributed to this analysis (Airaksinen 1993; Auclair 1989; Campbell 1994; Diebshlag 1990; Dreiser 1988; Dreiser 1989; Dreiser 1990; Haig 1986), of which one (Diebshlag 1990) had two treatment arms. In total, 310 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 288 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 71% (221/310, range 59% to 92%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 47% (136/288, range 17% to 83%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7);

The NNT for successful treatment was 4.2 (3.2 to 6.1). For every four participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

There was no significant difference between studies using protocoldefined preferred outcomes and undefined outcomes of success.

Treatment duration

Treatment for 6 to 8 days

Twenty-six studies contributed to this analysis, of which two (Aoki 1984; Diebshlag 1990) had two treatment arms. In total, 1446 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 1340 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 65% (934/1446, range 31% to 92%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 40% (534/1340, range 8% to 83%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7);

The NNT for successful treatment was 4.0 (3.5 to 4.7). For every four participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Treatment for 9 to 14 days

Five studies contributed to this analysis (Fujimaki 1985; Mazieres 2005a; Mazieres 2005b; Sinneger 1981; Vecchiet 1989), of which one (Fujimaki 1985) had two treatment arms. In total, 373 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 289 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with a topical NSAID was 66% (247/373, range 53% to 100%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with placebo was 56% (161/289, range 10% to 73%);

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4);

The NNT for successful treatment was 9.5 (5.6 to 33). For every nine or ten participants treated with a topical NSAID, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with placebo.

Further analysis confirmed that studies reporting outcomes at 6 to 8 days gave a better estimate of efficacy (lower NNT) than those reporting at 9 to 14 days (z = 3.3631, P = < 0.00097).

Summary of results B: sensitivity analyses.

| Comparison | Subgroup | Studies | Participants | NSAID (%) | Placebo (%) | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study size | < 40 per arm | 13 | 681 | 78 | 44 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | 3.0 (2.5 to 3.8) |

| ≥ 40 per arm | 18 | 2774 | 62 | 42 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 5.0 (4.3 to 6.2) | |

| Outcomes | Preferred | 23 | 2857 | 63 | 42 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 4.5 (3.9 to 5.5) |

| Undefined | 8 | 598 | 71 | 47 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 4.2 (3.2 to 6.1) | |

| Treatment duration | 6 to 8 days | 26 | 2786 | 65 | 40 | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.7) |

| 10 to 14 days | 5 | 662 | 66 | 56 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 9.5 (5.6 to 33) |

Local adverse events

Local adverse events were irritation of the area to which the topical NSAID was applied, including redness/erythema and itch/pruritus. Where reported these were usually described as mild and transient.

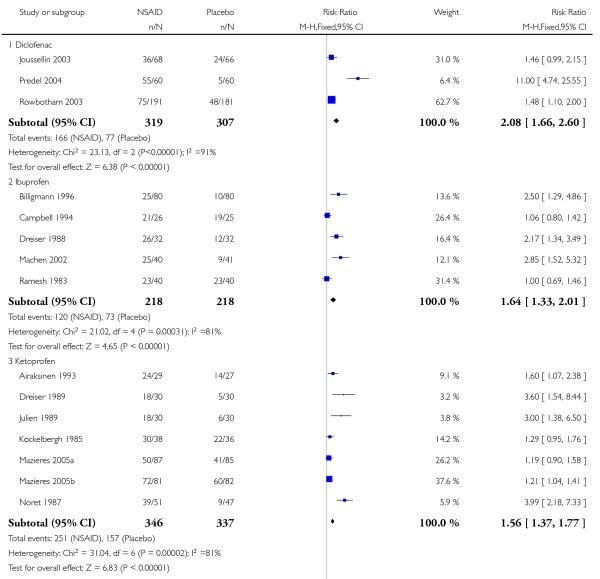

All topical NSAIDs versus placebo

Thirty studies contributed to this analysis, of which three (Aoki 1984; Diebshlag 1990; Fujimaki 1985) had two treatment arms. In total, 1994 participants were treated with topical NSAIDs and 1792 with placebo (Analysis 1.5).

The proportion of participants experiencing a local adverse event with a topical NSAID was 6.3% (126/1994, range 0% to 33%);

The proportion of participants experiencing a local adverse event with placebo was 5.9% (105/1792, range 0% to 32%);

The RR of topical NSAID compared to placebo was 1.1 (0.88 to 1.4);

There was no significant difference between treatment groups so the NNH was not calculated.

Individual topical NSAIDs versus placebo

Results for local adverse events with individual topical NSAIDs, where there were adequate data for analysis, are in Summary of results C and Analysis 2.2.

Summary of results C: Participants with local adverse events

| Comparison | Studies | Participants | NSAID (%) | Placebo (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All NSAIDs | 30 | 3786 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 1.1 (0.88 to 1.4) | not calculated |

| Diclofenac | 4 | 746 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.3) | not calculated |

| Felbinac | 3 | 397 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.9 (0.49 to 7.5) | not calculated |

| Ibuprofen | 3 | 321 | 10 | 4.3 | 2.3 (0.98 to 5.4) | not calculated |

| Ketoprofen | 8 | 852 | 11 | 9.5 | 1.2 (0.83 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| Piroxicam | 3 | 522 | 2.3 | 5.4 | 0.42 (0.16 to 1.1) | not calculated |

| Indomethacin | 3 | 354 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 2.9 (0.92 to 8.8) | not calculated |

Systemic adverse events

Twenty-five studies contributed data on systemic adverse events, of which three (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985; Diebshlag 1990) had two treatment arms. In total, 1641 participants received a topical NSAID and 1454 placebo (Analysis 1.6).

Eighteen studies reported no systemic adverse events in any arm of the study

The proportion of participants experiencing a systemic adverse event with a topical NSAID was 3.2% (52/1641)

The proportion of participants experiencing a systemic adverse event with placebo was 3.4% (50/1454)

There was no significant difference between the rates of systemic adverse events in participants using a topical NSAID and those using placebo.

A further six studies (Billigmann 1996; Julien 1989; Kockelbergh 1985; Noret 1987; Ramesh 1983; Vecchiet 1989) did not report the occurrence or otherwise of systemic adverse events, while two studies (Akermark 1990; Auclair 1989) did not report numbers of participants with systemic adverse events.

Serious adverse events

No studies reported any serious adverse events.

Withdrawals

Thirty-two studies reported data relating to adverse event withdrawals, of which three (Aoki 1984, Fujimaki 1985, Diebshlag 1990) had two treatment arms. In total 2072 patients received a topical NSAID and 1871 placebo.

Twenty studies reported no adverse event withdrawals in any arm of the study.

The proportion of participants withdrawing from the study due to an adverse event after treatment with a topical NSAID was 1.2% (24/2072).

The proportion of participants withdrawing from the study due to an adverse event after treatment with placebo was 1.0% (18/1871).

There was no significant difference between the rates of withdrawal due to adverse events in participants treated with topical NSAID and those treated with placebo.

Eight studies (Dreiser 1989; Dreiser 1994; Machen 2002; Mazieres 2005a; Mazieres 2005b; Noret 1987; Russell 1991; Thorling 1990) reported withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (Table 2). There were insufficient events for analysis.

Some studies reported exclusions from analysis (efficacy and/or safety) following randomisation, mainly due to protocol violations or loss to follow up (Table 2). There is no reason to believe these exclusions would introduce systematic bias, and the numbers involved were not likely to influence results.

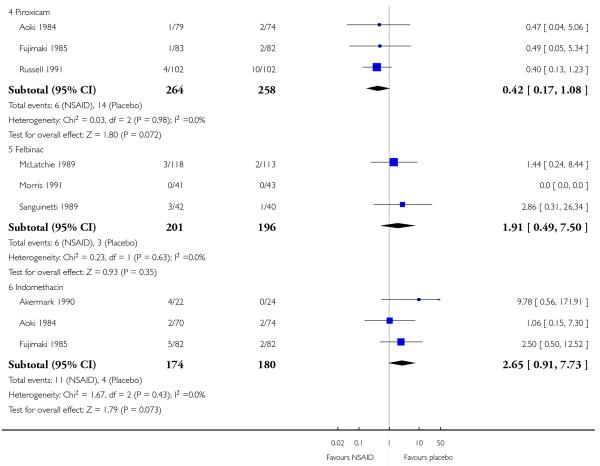

2. Topical NSAID versus active comparator

Participants with clinical success

Topical NSAID versus oral NSAID

Akermark 1990 compared indomethacin spray with indomethacin capsules, with response rates of 55% (12/22) and 23% (5/22) respectively.

Hosie 1993 compared felbinac foam with ibuprofen tablets, with response rates of 64% (81/127) and 72% (96/133) respectively.

Whitefield 2002 compared ibuprofen gel with ibuprofen tablets, with response rates of 60% (30/50) and 54% (36/50) respectively.

There were insufficient data for meta-analysis for any one of these comparisons, and felbinac is not known to be better than placebo (see Analysis 3.1).

Topical NSAID versus different formulation of the same topical NSAID

Fioravanti 1999 compared DHEP (diclofenac) gel formulated with and without lecithin, with response rates of 70% (35/50) in both treatment arms.

Mahler 2003 compared DHEP (diclofenac) gel formulated with and without lecithin, with response rates of 89% (82/92) and 70% (62/88) respectively.

Gallacchi 1990 compared topical diclofenac formulated as Flector® gel and Emugel®, with response rates of 76% (19/25) in both treatment arms

Governali 1995 compared topical ketoprofen cream with gel, with response rates of 93% (14/15) and 27% (4/15) respectively.

There were insufficient data for analysis (see Analysis 3.1).

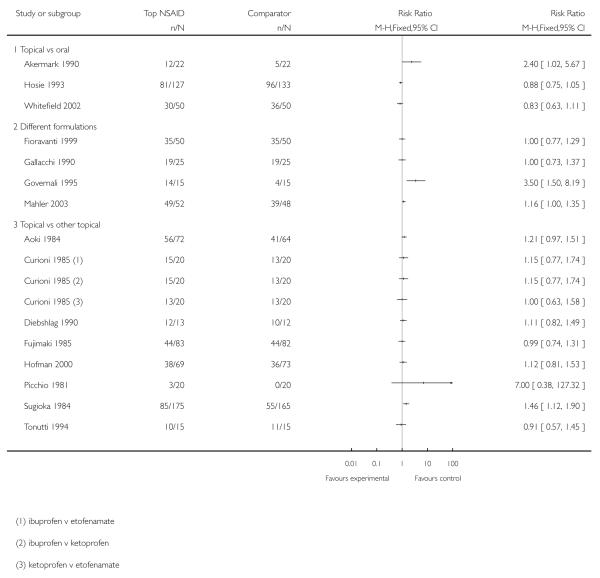

Topical NSAID versus different topical NSAID

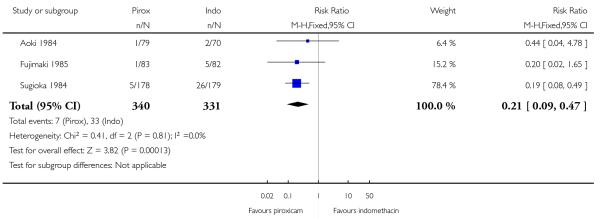

Eight studies compared one topical NSAID against at least one other: piroxicam versus indomethacin (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985; Sugioka 1984), ibuprofen versus ketoprofen (Curioni 1985; Picchio 1981), ketoprofen versus etofenamate (Curioni 1985; Tonutti 1994), ibuprofen versus etofenamate (Curioni 1985), ketorolac versus etofenemate (Diebshlag 1990), and diclofenac versus lysine cloxinate (Hofman 2000) (see Analysis 3.1). There were sufficient data for analysis only of the comparison of piroxicam with indomethacin (see Analysis 3.2).

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical piroxicam was 56% (185/330, range 49% to 78%);

The proportion of participants experiencing successful treatment with topical indomethacin was 45% (140/311, range 33% to 64%);

The RB of piroxicam compared with indomethacin was 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4);

The NNT for successful treatment was 9.1 (5.3 to 30). For every nine participants treated with topical piroxicam, one would experience successful treatment who would not have done so with topical indomethacin.

Local adverse events

Topical NSAID versus oral NSAID

Two studies (Akermark 1990; Hosie 1993) comparing a topical NSAID with an oral NSAID provided data on local adverse events. There were a total of five events with topical NSAID and three with oral NSAID, too few for analysis (Table 2).

Topical NSAID versus different topical NSAID

All nine studies comparing one topical NSAID with at least one other reported on local adverse events, with a total of 48 events in 1005 participants (4.8%) (Table 2). There were sufficient data to compare only piroxicam with indomethacin (Aoki 1984; Fujimaki 1985; Sugioka 1984; Analysis 3.3).

The proportion of participants experiencing local adverse events with topical piroxicam was 2.1% (7/340, range 1.2% to 2.8%);

The proportion of participants experiencing local adverse events with topical indomethacin was 10% (33/331, range 2.9% to 15%);

The RB of piroxicam compared with indomethacin was 0.21 (0.09 to 0.47);

The NNT to prevent a local adverse event was 13 (8.7 to 23). For every thirteen participants treated with topical piroxicam, one would not experience a local adverse event who would have experienced one with topical indomethacin.

Systemic adverse events

Akermark 1990 reported numbers of events, rather than numbers of participants with events, while Tonutti 1994 and Whitefield 2002 reported no adverse events attributable to the study medication, and Fioravanti 1999; Gallacchi 1990; Gualdi 1987 and Sugioka 1984 did not mention systemic adverse events. In the remaining studies a total of 16 events were reported in topical NSAID treatment arms (797 participants, 2%) and 11 with ibuprofen tablets (134 participants, 8%) (Table 2).

Serious adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in any treatment arm.

Withdrawals

The only withdrawals reported due to adverse events were in studies with placebo treatment arms (Akermark 1990; Fujimaki 1985), and have been reviewed.

Two studies (Hofman 2000; Tonutti 1994) reported withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (Table 2). There were insufficient data for analysis.

Some studies reported exclusions from analysis (efficacy and/or safety) following randomisation, mainly due to protocol violations or loss to follow up (Table 2). There is no reason to believe these exclusions would introduce systematic bias, and the numbers involved were not likely to influence results.

Details of efficacy outcomes in individual studies are in Table 1, and of adverse events and withdrawals in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This review included 47 studies comparing a topical NSAID with placebo and/or another topical NSAID or an oral NSAID. In total 3288 participants were treated with a topical NSAID, 2004 with placebo, and 220 with an oral NSAID. Conditions treated were sprains, strains and contusions, mainly resulting from sports injuries, and overuse injuries such as tendinitis.

For all topical NSAIDs combined, compared with placebo, the NNT for the primary outcome of clinical success was 4.5 (3.9 to 5.3), indicating that this is an effective route of administration for NSAIDs for these conditions. There was no significant difference between the individual NSAIDs diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen and piroxicam for the outcome of clinical success, with NNTs ranging from 3.7 to 4.6. Indomethacin only just reached statistical significance compared to placebo, and is probably not clinically useful, with an NNT of 8, and with a relatively small number of participants. Benzydamine was not significantly different from placebo, based on fewer than 200 participants.

Definition of clinical success did not significantly affect the NNT, but both size of treatment arms and time of assessment did. Studies with treatment arms of fewer than 40 participants gave a significantly lower (better) NNT than those with 40 or more participants. This effect has been shown previously for topical NSAID trials (Moore 1998a; Mason 2004a), but may be a more general effect (Counsell 1994). Approximately 25% of participants were in studies with treatment arms of fewer than 40 participants. Studies with assessments at 6 to 8 days gave a statistically lower (better) NNT than those with assessments at 9 to 14 days. This may reflect the fact that many of the injuries treated in these studies (acute sprains and strains) tend to resolve spontaneously after a week or two, even without treatment. Differences between NSAID and placebo are expected to diminish at assessment times longer than one week, with resultant reduction in effect size and increase in NNT.

Treatment with a topical NSAID was not associated with an increase in local adverse events (skin reactions) compared with placebo (inert carrier), or withdrawals due to adverse events. Systemic adverse events were uncommon and did not differ between topical NSAID and placebo; there were no serious adverse events. There were insufficient data directly comparing a topical NSAID with the same oral NSAID to draw conclusions about efficacy. Based on very limited data for oral NSAIDs, there were fewer systemic adverse events with topical than oral treatment. There were sufficient data only for topical piroxicam compared with topical indomethacin to compare one topical agent with another. These limited data suggested that piroxicam is more effective than indomethacin (NNT = 9 for clinical success), and is less likely to cause local adverse events. It is worth noting here that topical indomethacin was not significantly better than placebo in two of the three studies in this analysis.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The conditions treated in these studies are representative of those likely to be suitable for acute treatment with topical NSAIDs. The mean age of participants in individual studies ranged from 25 years to 57 years, and the nature of recruitment in many studies meant that participants were actively engaged in sporting activities. Nevertheless, older individuals in their 60s to 80s were also included in some studies, and the low levels of predominantly mild adverse events means that this route of administration of NSAIDs is suitable for all age groups able to manage the application process.

There were too few studies comparing one topical NSAID against another, or against the same oral NSAID, to allow meaningful direct comparisons between individual drugs or routes of administration.

Quality of the evidence

While all included studies are both randomised and double-blind, and none were considered at high risk of methodological bias, the majority were carried out between 1980 and 2000, when methodological rigor and detailed reporting were not given such high priority. Studies frequently did not report details of the randomisation, treatment allocation and blinding processes. Additionally, our primary outcome of clinical success was not always well-defined, and was measured using different scales. Despite this, however, sensitivity analysis did not demonstrate an effect of definition on outcome.

The studies were conducted in different conditions, with some-what different outcome definitions and duration, and with different topical NSAIDs and formulations. Moreover, the small size of many of the studies is likely to result in considerable chance variation (Counsell 1994; Moore 1998b). Despite these sources of potential clinical heterogeneity, most studies showed benefit of topical NSAID over placebo (Figure 4).

Figure 4. L’Abbé plot of clinical success in all trials of topical NSAID versus topical placebo. The size of the symbol is proportional to the size of the study (inset scale).

The design of studies to be able to demonstrate analgesic sensitivity is important in self-limiting conditions such as strains and sprains. Too long a duration and the condition results in spontaneous resolution of painful symptoms, while too short a duration may be inadequate to show any effect. The decision by trialists to concentrate on outcomes closest to seven days of treatment appears to be prudent, and has been adopted in this and previous reviews. There are potential differences in response to treatment between strains and sprains and overuse-type injuries like tendinitis, and future reviews may examine this. At the present time there are too few existing trials to adequately explore any differences.

Baseline pain may be a cause for concern. Four studies did not report baseline pain levels (Billigmann 1996; Curioni 1985; Haig 1986; Sinneger 1981), and a further 11 reported either mean levels of less than moderate pain or a significant proportion of individuals with less than moderate pain (Akermark 1990; Aoki 1984; Auclair 1989; Diebshlag 1990; Fujimaki 1985; Jenoure 1997; Linde 1985; Picchio 1981; Ramesh 1983; Sugioka 1984; Whitefield 2002), using recognised scales. Insufficient pain at baseline compromises the ability of a study to demonstrate any improvement.

Potential biases in the review process

One potential bias is that clinical trials for topical NSAIDs may not have been published. One previous review (Moore 1998a) did find previously unpublished trials, but a subsequent attempt that included extensive contacts with pharmaceutical companies revealed no additional data (Mason 2004a). There has been greater interest in topical NSAIDs in recent years, mainly because lower systemic drug levels reduce the risk of troublesome and severe adverse events, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract, renal and cardiovascular systems. However, most of the attention has been in chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis, with few trials in acute painful conditions. Some unpublished trials undoubtedly exist that we have not identified, but unpublished trials showing no difference between topical NSAID and topical placebo and involving 3500 participants would have to exist in order for the NNT to be as high as 9, at which point the effectiveness of topical NSAIDs would become clinically irrelevant (Moore 2006). This amount of unpublished negative data seems unlikely.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A review published in 2004 (Mason 2004a) included most of the studies in this review and reported an NNT of 3.8 (3.4 to 4.4) for clinical success equivalent to half pain relief at 7 days, a similar, but slightly better result. That review found no difference between topical NSAID and placebo for local adverse events, as did this review. In turn, the Mason review was in broad agreement with the original systematic review on topical NSAIDs (Moore 1998a). Studies included in this and the Mason review differ a little. We have included three studies using benzydamine (Chatterjee 1977; Haig 1986; Linde 1985), while the 2004 review did not, nine studies that were not identified or not published in 2004, and one further study (Gallacchi 1990) that was excluded in 2004 because we felt that the conditions treated were compatible with acute therapy. We excluded two studies (Baracchi 1982; Galer 2000) that were in the 2004 review because they provided no primary outcome data, and the adverse event data was not clearly reported in categories that we required.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Topical NSAIDs can provide good levels of pain relief in acute conditions such as sprains, strains and overuse injuries, probably similar to that provided by oral NSAIDs. There appears to be little difference in analgesic efficacy between topical diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen and piroxicam, but indomethacin is less effective, and benzydamine is no better than placebo. Topical NSAIDs are not associated with an increased incidence of local skin reactions compared with placebo, and do not cause systemic (mainly gastrointestinal) problems commonly seen with oral NSAIDs, making them particularly useful for individuals unable to tolerate oral administration, or for whom it is contraindicated.

Implications for research

Larger studies, of good methodological quality and using well-defined diagnostic criteria and outcome measures are needed to compare individual topical NSAIDs with one another, and with the same oral NSAID, in order to establish relative efficacy. Studies comparing different formulations of topical NSAIDs would help to establish which ones provide the best efficacy and/or convenience of application.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Topical non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) for acute pain in adults

Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are applied to the skin in the form of a gel, cream, or spray in the region where pain is experienced (a sprained ankle, for instance). They are typically used for strains or sprains, rather than headache or abdominal pain. The attraction of topical application of NSAIDS is that blood concentrations are typically less than 1/20th of those found with oral NSAIDs, minimising the risk of serious harm.

Topical NSAIDs have to penetrate the skin, enter tissues or joints, and be present in a high enough concentration to have an effect on the inflammatory processes causing pain. The evidence from a large number of studies is that topical NSAIDs work well, though evidence for good effect is available only for topical diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and piroxicam. About 6 or 7 out of 10 patients will have successful pain control over seven days with topical NSAID, compared with 4 out of 10 with placebo; the high response with placebo is because conditions like sprained ankles tend to get better on their own eventually. For every four or five participants treated with one of these topical NSAIDs, one would experience good pain relief (equivalent to at least 50% reduction) after about one week, who would not have done if treated with placebo.

Local adverse events at the site of application are no worse with topical NSAID than with topical placebo; they are mild and transient, and occur in about 6% of participants. Systemic adverse events (nausea, stomach upset, for example) and adverse event withdrawals were uncommon, occurring no more frequently with topical NSAID than topical placebo. No serious adverse events were reported in these studies.

Acknowledgments

Support for this review was from Pain Research Funds, the NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme. None had any input into the review at any stage.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Relief Trust, UK.

General institutional support

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy (via OVID)

exp Anti-inflammatory Agents, non-steroidal/

bufexamac OR bufexine OR calmaderm OR ekzemase OR diclofenac OR solaraze OR pennsaid OR voltarol OR emugel OR voltarene OR voltarol OR optha OR voltaren OR etofenamate OR afrolate OR algesalona OR bayro OR deiron OR etofen OR flexium OR flogoprofen OR rheuma-gel OR rheumon OR traumalix OR traumon OR zenavan OR felbinac OR dolinac OR flexfree OR napageln OR target OR traxam OR fentiazac OR domureuma OR fentiazaco OR norvedan OR riscalon OR fepradinol OR dalgen OR flexidol OR cocresol OR rangozona OR reuflodol OR pinazone OR zepelin OR flufenamic OR dignodolin OR rheuma OR lindofluid OR sastridex OR lunoxaprofen OR priaxim OR flubiprofen OR fenomel OR ocufen OR ocuflur OR “Trans Act LAT” OR tulip OR ibuprofen OR cuprofen OR “deep relief” OR fenbid OR ibu-cream OR ibugel OR ibuleve OR ibumousse OR ibuspray OR “nurofen gel” OR proflex OR motrin OR advil OR radian OR ralgex OR ibutop OR indomethacin OR indocin OR indospray OR isonixin OR nixyn OR ketoprofen OR tiloket OR oruvail OR powergel OR solpaflex OR ketorolac OR acular OR trometamol OR meclofenamic OR naproxen OR naprosyn OR niflumic OR actol OR flunir OR niflactol topico OR niflugel OR nifluril OR oxyphenbutazone OR californit OR diflamil OR otone OR tanderil OR piketoprofen OR calmatel OR triparsean OR piroxicam OR feldene OR pranoprofen OR oftalar OR pranox OR suxibuzone OR danilon OR flamilon OR ufenamate OR fenazol OR flector OR benzydamine.mp

1 OR 2

exp Administration, Topical/

topical* OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crème OR lotion OR mouse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster.mp

4 OR 5

exp Athletic Injuries/

strain OR sprain* OR contusion OR distortion OR compression OR “sports injur*” OR “soft tissue injur*” OR tend?nitis OR “muscle pain” OR periarthritis OR epicondylitis OR tenosynovitis. mp

7 OR 8

pain* OR analgesi*.mp

randomized controlled trial.pt

controlled clinical trial.pt

randomized.ab

placebo.ab

drug therapy.fs

randomly.ab

trial.ab

groups.ab

OR/11-18

3 AND 6 AND 9 AND 10 AND 19

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy (via OVID)

exp Anti-inflammatory Agents, non-steroidal/

bufexamac OR bufexine OR calmaderm OR ekzemase OR dicoflenac OR solaraze OR pennsaid OR voltarol OR emugel OR voltarene OR voltarol OR optha OR voltaren OR etofenamate OR afrolate OR algesalona OR bayro OR deiron OR etofen OR flexium OR flogoprofen OR rheuma-gel OR rheumon OR traumalix OR traumon OR zenavan OR felbinac OR dolinac OR flexfree OR napageln OR target OR traxam OR fentiazac OR domureuma OR fentiazaco OR norvedan OR riscalon OR fepradinol OR dalgen OR flexidol OR cocresol OR rangozona OR reuflodol OR pinazone OR zepelin OR flufenamic OR dignodolin OR rheuma OR lindofluid OR sastridex OR lunoxaprofen OR priaxim OR flubiprofen OR fenomel OR ocufen OR ocuflur OR “Trans Act LAT” OR tulip OR ibuprofen OR cuprofen OR “deep relief” OR fenbid OR ibu-cream OR ibugel OR ibuleve OR ibumousse OR ibuspray OR “nurofen gel” OR proflex OR motrin OR advil OR radian OR ralgex OR ibutop OR indomethacin OR indocin OR indospray OR isonixin OR nixyn OR ketoprofen OR tiloket OR oruvail OR powergel OR solpaflex OR ketorolac OR acular OR trometamol OR meclofenamic OR naproxen OR naprosyn OR niflumic OR actol OR flunir OR niflactol topico OR niflugel OR nifluril OR oxyphenbutazone OR californit OR diflamil OR otone OR tanderil OR piketoprofen OR calmatel OR triparsean OR piroxicam OR feldene OR pranoprofen OR oftalar OR pranox OR suxibuzone OR danilon OR flamilon OR ufenamate OR fenazol OR flector OR benzydamine.mp

1 OR 2

exp Administration, Topical/

topical* OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crème OR lotion OR mouse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster.mp

4 OR 5

exp Athletic Injuries/

strain OR sprain* OR contusion OR distortion OR compression OR “sports injur*” OR “soft tissue injur*” OR tend?nitis OR “muscle pain” OR periarthritis OR epicondylitis OR tenosynovitis. mp

7 OR 8

pain* OR analgesi*.mp

clinical trials.sh

controlled clinical trials.sh

randomized controlled trial.sh

double-blind procedure.sh

(clin* adj25 trial*).ab

((doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj25 (blind* or mask*)).ab

placebo*.ab

random*.ab

OR/11-18

3 AND 6 AND 9 AND 10 AND 19

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

MeSH Descriptor Anti-inflammatory Agents, non-steroidal [explode all trees]

bufexamac OR bufexine OR calmaderm OR ekzemase OR dicoflenac OR solaraze OR pennsaid OR voltarol OR emugel OR voltarene OR voltarol OR optha OR voltaren OR etofenamate OR afrolate OR algesalona OR bayro OR deiron OR etofen OR flexium OR flogoprofen OR rheuma-gel OR rheumon OR traumalix OR traumon OR zenavan OR felbinac OR dolinac OR flexfree OR napageln OR target OR traxam OR fentiazac OR domureuma OR fentiazaco OR norvedan OR riscalon OR fepradinol OR dalgen OR flexidol OR cocresol OR rangozona OR reuflodol OR pinazone OR zepelin OR flufenamic OR dignodolin OR rheuma OR lindofluid OR sastridex OR lunoxaprofen OR priaxim OR flubiprofen OR fenomel OR ocufen OR ocuflur OR “Trans Act LAT” OR tulip OR ibuprofen OR cuprofen OR “deep relief” OR fenbid OR ibu-cream OR ibugel OR ibuleve OR ibumousse OR ibuspray OR “nurofen gel” OR proflex OR motrin OR advil OR radian OR ralgex OR ibutop OR indomethacin OR indocin OR indospray OR isonixin OR nixyn OR ketoprofen OR tiloket OR oruvail OR powergel OR solpaflex OR ketorolac OR acular OR trometamol OR meclofenamic OR naproxen OR naprosyn OR niflumic OR actol OR flunir OR niflactol topico OR niflugel OR nifluril OR oxyphenbutazone OR californit OR diflamil OR otone OR tanderil OR piketoprofen OR calmatel OR triparsean OR piroxicam OR feldene OR pranoprofen OR oftalar OR pranox OR suxibuzone OR danilon OR flamilon OR ufenamate OR fenazol OR flector OR benzydamine:ti,ab,kw

1 OR 2

MeSH Descriptor Administration, Topical [explode all trees]

topical* OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crème OR lotion OR mouse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster:ti,ab,kw

4 OR 5

MeSH Descriptor Athletic Injuries [explode all trees]

strain OR sprain* OR contusion OR distortion OR compression OR “sports injur*” OR “soft tissue injur*” OR tend?nitis OR “muscle pain” OR periarthritis OR epicondylitis OR tenosynovitis:ti,ab,kw

7 OR 8

pain* OR analgesi*:ti,ab,kw

Randomized controlled trial:pt

MESH descriptor Double-blind Method

random*:ti,ab,kw.

OR/11-13

3 AND 6 AND 9 AND 10 AND 14

Limit 15 to Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel applied to the painful area twice daily for 7 days Assessment at baseline, 3, 7 days |

|

| Participants | Minor soft tissue injuries (<7 days) N= 56 M 45, F 11 Age not reported Mean baseline pain at rest 25 to 26 mm |

|

| Interventions | Ketoprofen gel, 2 × 5 g (125 mg) daily, n = 29 Placebo gel, n = 27 Rescue medication paracetamol 500 mg No other treatment allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 5 point scale but reported as “improved” or “same or worse” (responder = “improved”) Improvement in pain with movement: 100 mm VAS, reported as group Mean Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 9/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Methods | RCT, DB (double dummy), parallel groups Spray applied to affected area, and capsules taken three times daily for 2 weeks Assessment at baseline, 3 or 4, 7, and 14 days |

|

| Participants | Superficial overuse sports injuries (symptom onset 7.4 weeks) N = 70 M 44, F 18 (completers) Mean age 30 years Baseline pain on palpation mostly slight to moderate |

|

| Interventions | Elmetacin spray (indomethacin 1%), 3-5 × 0.5-1.5 ml daily + placebo capsules, n = 23 Indomethacin capsules, 3 × 25 mg daily + placebo spray, n = 23 Placebo spray and capsules, n = 24 Rescue medication: paracetamol |

|

| Outcomes | No pain on palpation (= responder) Patient Improvement: 100 mm VAS (mean data) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 Oxford Validity Score: 13/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “random number code” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “identical in appearance” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel applied to affected area three or four times daily, with no occlusion for 7 days Assessment at baseline, 3, 7 days |

|

| Participants | Acute orthopaedic trauma (contusion, distortion, fracture, <7 days) N = 252 (203 analysed for efficacy) M 98, F 105 Age range 8 to 86 years, 13% <20 years Baseline pain mild in 35% Exclusions: 23 protocol violations, 26 reasons “not related” to drug. Equally distributed between groups |

|

| Interventions | Piroxicam gel 0.5%, 3-4 × 1 g daily, n = 84 Indomethacin gel 1%, 3-4 × 1 g daily, n = 84 Placebo gel, n = 84 No other medication or initiation of physical therapy allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 5 point scale (responder = “better” and “much better”) Adverse events Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score: 14/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “key code sealed until end of study” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | gels in “identical tubes” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel massaged into skin over affected heel three times daily after cleaning with soap and water for up to 21 days Assessment at baseline, 7, 21 days |

|

| Participants | Acute achilles heel tendinitis (not associated with continuous pain at rest or >1 month history) N = 243 (227 analysed for efficacy) M/F not reported Mean age 29 years Baseline pain: ~10% had <26 mm on palpation of tendon, ~30% had mild or no pain on dorsifexion of foot Exclusions: failure to meet inclusion criteria, major protocol violations, failure to take study medication for full duration |

|

| Interventions | Niflumic acid gel 2.5%, 3× 5 g daily, n = 117 Placebo gel, n = 110 No other analgesics and antiinflammatories, physiotherapy or supportive measures allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 5 point scale (responder = “good” or “very good”) Pain improved or disappeared on dorsiflexion Adverse events Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 12/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel applied three times daily with rubbing Assessed at baseline, 3, 5, 7 days |

|

| Participants | Distortion of ankle joint N = 160 M and F Age 18+ years Baseline pain not reported |

|

| Interventions | Ibuprofen microgel 5%, 3×10 cm (= 200 mg) daily, n = 80 Placebo gel, n = 80 |

|

| Outcomes | Pain with movement: VAS (responder = decreased by 20%) Complete remission Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 8/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Cream applied four times daily for 7 days (up to 14 days optional) Self-assessed using daily diary for 7 days, and up to 14 days |

|

| Participants | Acute ankle sprain (<24 hours, no fracture) N = 100 (51 analysed) M 33, F 18 Mean age 29 years Baseline pain at rest >35 mm, on walking 80 mm Exclusions: did not return diaries, protocol exclusions (25 ibuprofen, 24 placebo) |

|

| Interventions | Ibuprofen cream 5% (Proflex), 4 × 4” daily, n = 26 Placebo cream, n = 25 Advised to use rest and regular icing for 48 hours, then walking and exercise Rescue medication: paracetamol |

|

| Outcomes | Improvement in walking ability: 4 point scale (responder = “improvement”) Pain on walking: 100 mm VAS (mean data) Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score: 14/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation carried out by sponsor. Tubes dispensed by hospital pharmacy who held the codes |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “identical cream” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Cream applied to site of injury three times daily for 6 days Assessment at baseline, 2, 6 days |

|

| Participants | Soft tissue injuries (recent) N= 51 M/F not reported Age not reported Baseline pain on passive movement moderate or severe in all but 3 participants |

|

| Interventions | Benzydamine HCl cream 3%, 3× daily, n = 25 Placebo cream, n = 25 (5 active, 6 placebo participants also received ultrasound) No other topical agent allowed |

|

| Outcomes | Pain on passive movement: 4 point scale (responder = “absent” or “slight”) Tenderness with pressure: 4 point scale (responder = “absent” or “slight”) Adverse events Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score:14/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “predetermined randomised schedule” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed copy of schedule held by investigator and duplicate copy kept by clinical trial coordinator. Looked at only in event of adverse reaction (not necessary) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “indistinguishable …. in appearance and consistency” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel rubbed into affected area until absorbed, twice daily for 10 days Assessed at baseline, and daily to 10 days |

|

| Participants | Acute soft tissue injuries N = 60 M 33, F 27 Median Age 33 years Baseline pain not given |

|

| Interventions | Ibuproxam gel 10%, n = 20 Ketoprofen gel, n = 20 Etofenamate gel, n = 20 |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 4 point scale (“good” or “excellent”) Resolution of symptoms Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score: 9/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Medication supplied in identical tubes |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel applied three times daily, without occlusion, for 14 days Assessment at baseline, 2, 3, 4, 8, 15 days |

|

| Participants | Ankle sprain (<24 hrs) N = 37 M 24, F 13 Mean age 28 years Baseline pain slight to moderate |

|

| Interventions | Ketorolac gel 2%, 3 × 3 g daily, n = 13 Etofenamate gel 5%, 3 × 3 g daily, n = 12 Placebo gel, n = 12 Rescue medication: paracetamol No other analgesic or antiinflammatory medication, ice packs, or physiotherapy allowed |

|

| Outcomes | Reduction in pain intensity: 100 mm VAS and 4 point scale (responder = “improved”) Adverse events Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score: 12/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Medication assignment … supplied in a sealed envelope”. Opened only if serious patient event necessitation treatment disclosure occurred (not necessary) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “identical appearance” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Cream applied three times daily Assessment at baseline and 7 days |

|

| Participants | Acute tendinitis (< 1 month) N = 64 M 35, F 25 Mean age 36 years Baseline spontaneous pain ≥60 mm |

|

| Interventions | Ibuprofen cream 5%, 3 × 4cm daily, n = 32 (3 × 10 cm for large joints) Placebo cream, n = 32 No other topical, systemic or physical treatment allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: scale not reported (responder = “improvement” or “complete relief”) Improvement in pain: VAS (mean data) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 10/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel applied twice daily to affected area with light massage, then covered with standard compress Assessed at baseline, 3, 7 days |

|

| Participants | Uncomplicated, recent ankle sprain N = 60 M 36, F 24 Mean age 33 years Mean baseline pain 54 mm |

|

| Interventions | Ketoprofen gel 2.5%, 2 × 5cm daily, n = 30 Placebo gel, n = 30 No concomitant therapy other than simple oral analgesia allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 3 point scale (responder = “better”) Improvement in pain: VAS (mean data) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 Oxford Validity Score: 14/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “drawing lots” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Treatments “identical in every way except that placebo did not contain active principle” |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Gel lightly massaged into skin over affected area three times daily, then covered with standard compress Assessed at baseline, 3, 7, days |

|

| Participants | Uncomplicated, ankle sprain (<4 days) N = 60 (59 analysed) M 29, F 29 (not stated for 1 participant) Mean age 33 years Baseline pain ≥moderately severe Exclusions: 1 participant had only moderate pain at baseline |

|

| Interventions | Niflumic acid gel 2.5%, 3 × 5 g daily, n = 30 Placebo gel, n = 30 Concomitant treatment with systemic NSAIDs, local therapies, or physiotherapy were not allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 4 point scale (responder = “cured” or “improved”) Improvement in pain: VAS (mean data) Adverse events Withdrawals and exclusions |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 11/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Methods | RCT, DB, parallel groups Patch applied twice daily Assessed at baseline, 3, 7, days |

|

| Participants | Traumatic ankle sprain (<2 days) N = 131 M 84, F 47 Mean age 34 years Baseline pain ≥50 mm |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen patch, 2 × 40 mg daily, n = 65 Placebo patch, n = 66 Rescue medication: paracetamol. Ice or light restraint allowed Exclusions: 1 from flurbiprofen group for protocol violation |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 4 point scale (responder = “good” or “very good”) Improvement in pain: VAS (mean data) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 Oxford Validity Score: 16/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Placebo patch was “non-medicated (but otherwise identical)” |

| Methods | RCT, D, parallel groups Gel lightly massaged into skin three times daily, and kept dry for 6 to 8 hours Assessed at baseline, 3, 10, days |

|

| Participants | Peri and extra-articular inflammatory diseases N = 100 M 32, F 68 Mean age49 years Baseline spontaneous pain ≥40 mm |

|

| Interventions | DHEP lecithin gel, 3 × 5 g (= 65 mg) daily, n = 50 DHEP gel, 3 × 5 g (= 65 mg) daily, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | PGE: 4 point scale (responder = “good” or “excellent”) Pain on movement:Mean Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 Oxford Validity Score: 13/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |