Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 1, 2004 ‐ this original review had been split from a previous title on 'Single dose paracetamol (acetaminophen) with and without codeine for postoperative pain'. The last version of this review concluded that paracetamol is an effective analgesic for postoperative pain, but additional trials have since been published. This review sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of paracetamol using current data, and to compare the findings with other analgesics evaluated in the same way.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of single dose oral paracetamol for the treatment of acute postoperative pain.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Oxford Pain Relief Database and reference lists of articles to update an existing version of the review in July 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trials of paracetamol for acute postoperative pain in adults.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Area under the “pain relief versus time” curve was used to derive the proportion of participants with paracetamol or placebo experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, using validated equations. Number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT) was calculated, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The proportion of participants using rescue analgesia over a specified time period, and time to use, were sought as measures of duration of analgesia. Information on adverse events and withdrawals was also collected.

Main results

Fifty‐one studies, with 5762 participants, were included: 3277 participants were treated with a single oral dose of paracetamol and 2425 with placebo. About half of participants treated with paracetamol at standard doses achieved at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, compared with about 20% treated with placebo. NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours following a single dose of paracetamol were as follows: 500 mg NNT 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8); 600 to 650 mg NNT 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5); 975 to 1000 mg NNT 3.6 (3.4 to 4.0). There was no dose response. Sensitivity analysis showed no significant effect of trial size or quality on this outcome.

About half of participants needed additional analgesia over four to six hours, compared with about 70% with placebo. Five people would need to be treated with 1000 mg paracetamol, the most commonly used dose, to prevent one needing rescue medication over four to six hours, who would have needed it with placebo. Adverse event reporting was inconsistent and often incomplete. Reported adverse events were mainly mild and transient, and occurred at similar rates with 1000 mg paracetamol and placebo. No serious adverse events were reported. Withdrawals due to adverse events were uncommon and occurred in both paracetamol and placebo treatment arms.

Authors' conclusions

A single dose of paracetamol provides effective analgesia for about half of patients with acute postoperative pain, for a period of about four hours, and is associated with few, mainly mild, adverse events.

Plain language summary

Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for postoperative pain relief in adults

Pain is commonly experienced after surgical procedures, and is not always well controlled. This review assessed data from fifty‐one studies and found that paracetamol provided effective pain relief for about half of participants experiencing moderate to severe pain after an operation, including dental surgery for a period of about four hours. There were no clear differences between doses of paracetamol typically used. These single dose studies did not associate paracetamol with any serious side effects.

Background

This is an update of a review published in The Cochrane Library in Issue 1, 2004 on 'Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for postoperative pain' (Barden 2004a). The title now states that the review is limited to adults.

In the clinical development of analgesics, the first step is to demonstrate that they alleviate pain. This can only be done by testing them in people with established pain, and experience has shown that this must be clinical, rather than experimentally‐induced, pain. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, also called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is appropriate, because not all participants given analgesic will have significant pain relief, and about 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006).

The demonstration that a drug is an analgesic in an acute pain situation is important. In itself, such demonstration does not determine the utility of the tested drug in any particular situation. However, because drugs that work well in one pain condition generally work well in others, with a similar relative efficacy, acute pain trials provide useful information relevant to many other pain conditions. Knowing the relative efficacy of different analgesic drugs at various doses can be helpful. An example is the relative efficacy in the third molar extraction pain model (Barden 2004b).

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity or pain relief scales immediately before the intervention, over the following four to six hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. Patients with inadequate pain relief after 60 to 120 minutes are given rescue medication. For these patients it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over four to six hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first six hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) was first identified as the active metabolite of two older antipyretic drugs, acetanilide and phenacetin in the late nineteenth century. It became available in the UK on prescription in 1956, and over‐the‐counter in 1963 (PIC 2008). Since then it has become one of the most popular antipyretic and analgesic drugs worldwide, and is often also used in combination with other drugs.

The lack of significant anti‐inflammatory activity of paracetamol implies a mode of action distinct from that of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) yet, despite years of use and research, the mechanisms of action of paracetamol are not fully understood. NSAIDs act by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), now recognised to consist of two isoforms, COX‐1 and COX‐2, which catalyses the production of prostaglandins responsible for pain and inflammation. Paracetamol has previously been shown to have no significant effects on COX‐1 or COX‐2 (Schwab 2003), but is now being considered as a selective COX‐2 inhibitor (Hinz 2008). Significant paracetamol‐induced inhibition of prostaglandin production has been demonstrated in tissues in the brain, spleen, and lung (Botting 2000; Flower 1972). A 'COX‐3 hypothesis' wherein the efficacy of paracetamol is attributed to its specific inhibition of a third cyclooxygenase isoform enzyme, COX‐3 (Botting 2000; Chandrasekharan 2002; PIC 2008) now has little credibility, and a central mode action of paracetamol is thought to be likely (Graham 2005).

Despite a low incidence of adverse effects, paracetamol has a recognised potential for hepatotoxicity and is thought to be responsible for approximately half of all cases of liver failure in the UK (Hawton 2001), and about 40% in the USA (Norris 2008). Acute paracetamol hepatotoxicity at therapeutic doses is extremely unlikely despite reports of so‐called therapeutic misadventure (Prescott 2000). In recent years legislative changes restricting pack sizes and the maximum number of tablets permitted in over‐the‐counter sales were introduced in the UK (CSM 1997) on the basis of evidence that poisoning is lower in countries that restrict availability (Gunnell 1997; Hawton 2001). The contribution of these changes, which are inconvenient and more costly (particularly to chronic pain sufferers), to any observed reductions in incidence of liver failure or death, remains uncertain (Hawkins 2007). There have been concerns over the safety of paracetamol in patients with compromised hepatic function (those with severe alcoholism, cirrhosis or hepatitis) but these have not been substantiated (Dart 2000; PIC 2008).

Low technology interventions such as oral paracetamol administration, used appropriately, have the potential to reduce unnecessary pain. Paracetamol is the analgesic of choice for adult patients in whom salicylates or other NSAIDs are contraindicated. Such patients include asthmatics, those with salicylate allergies, and those with a history of peptic ulcer. Paracetamol is useful for children with febrile viral illnesses, in whom aspirin is contraindicated due to the risk of Reye's syndrome (swelling of the brain that may lead to coma and death).

The previous version of this Cochrane systematic review (Barden 2004a) concluded that paracetamol is effective for postoperative pain, but additional trials have since been published. This review aims to provide robust estimates of both efficacy and harm, in a format facilitating direct comparison with other analgesics.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and adverse effects of single dose paracetamol for acute postoperative pain using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, using wider criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were full publications of double blind trials of single dose oral paracetamol against placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least ten participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were included provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

Studies were excluded if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of trials concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

trials using healthy volunteers;

trials where pain relief was assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e., not patient‐reported);

trials of less than four hours' duration or which failed to present data over four to six hours post‐dose.

Types of participants

Trials of adult patients (15 years and older) with postoperative pain of moderate to severe intensity following day surgery or inpatient surgery were included. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain intensity was assumed to be of at least moderate intensity when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). Trials of patients with postpartum pain were included provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). Trials investigating pain due to uterine cramps alone were excluded.

Types of interventions

Oral paracetamol or matched placebo for relief of postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data were collected on the following outcomes:

patient characteristics;

pain model;

patient reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain will not be included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief and/or pain intensity expressed hourly over four to six hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of visual analogue scales (VAS) or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at four to six hours;

patient global evaluation (PGE) of treatment using a standard scale

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Details of the outcomes sought and scales used to measure them are in the glossary (Appendix 4).

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane CENTRAL (November 2002 for original search and July 2008 for the update).

MEDLINE via Ovid (1966 to November 2002 for the original review and July 2008 for the update).

EMBASE via Ovid (1966 to November 2002 for the original review and May 2008 for the update).

Oxford Pain Database (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy.

Reference lists of retrieved studies were also manually searched. Other databases searched for the original review were not searched for the update.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Abstracts, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched. Manufacturers were not contacted.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the updated review

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b).

The scale used is as follows:

Is the study randomised? If yes ‐ one point

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point

Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add 1 point, if no deduct one point

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point

The results are described in the 'Methodological quality of included studies' section below

Data management

Data were extracted by two review authors and recorded on a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.0.13.

Data analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one valid post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants randomised to each treatment group who took the study medication. Analyses were planned for different doses (where there were at least 200 participants). Sensitivity analyses were planned for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (two versus three or more).

Primary outcome: number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, mean TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) for active and placebo groups were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was then used to calculate relative benefit (RR) and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT). Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, the number of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global evaluation scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" would be used for the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

Secondary outcomes:

1. Use of rescue medication

Numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate numbers needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication was used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

2. Adverse events

Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study)

withdrawal due to an adverse event

3. Other withdrawals

Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted.

Relative benefit/risk estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT/NNH and 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the relative benefit did not include the number one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbe 1987). The z test (Tramer 1997) was used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different doses of active treatment, or between groups in the sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Fifty‐one studies, with 5762 participants in total, fulfilled the entry criteria. Forty‐six studies were included in the 2004 review (Bentley 1987; Berry 1975; Bhounsule 1990; Bjune 1996; Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1989; Cooper 1991; Cooper 1998; Dionne 1994; Dolci 1994; Edwards 2002; Fassolt 1983; Forbes 1982; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1984b; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Hersh 2000; Honig 1984; Jain 1986; Kiersch 1994; Laska 1983 (Study 3); Lehnert 1990; McQuay 1988; Mehlisch 1984; Mehlisch 1990; Mehlisch 1995; Moller 2000; Pinto 1984; Rubin 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Sakata 1986; Santos Pereira 1986; Schachtel 1989; Seymour 1996; Sunshine 1986; Sunshine 1989; Sunshine 1993; Winnem 1981; Winter 1979; Winter 1983; Young 1979). Five new studies (Haglund 2006; Kubitzek 2003; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Seymour 2003) were added to this update. Details of included and excluded studies are in the corresponding "Characteristics of included studies" tables.

It is worth noting that one study (Forbes 1990b), which appeared in the 2004 review, was not included in our analysis. It does not have a paracetamol only arm and it is not clear why it appeared in the 2004 review.

Two studies contained two relevant active treatment arms, (Moller 2000; Seymour 1996) and one contained three (Laska 1983 (Study 3)). One study was a review reporting two separate groups of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with separate placebo groups (Edwards 2002) hence the total number of comparisons for analysis was 56.

Paracetamol 500 mg was used in six studies with 561 participants (Cooper 1980; Dolci 1994; Laska 1983 (Study 3); Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Seymour 1996).

Paracetamol 600 or 650 mg was used in 19 studies with 1886 participants (Bhounsule 1990; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Edwards 2002; Fassolt 1983; Forbes 1982; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1984b; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Honig 1984; Jain 1986; Sunshine 1986; Sunshine 1989; Sunshine 1993; Young 1979).

Paracetamol 975 or 1000 mg was used in 28 studies with 3232 participants (Bentley 1987; Berry 1975; Bjune 1996; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1989; Cooper 1998; Edwards 2002; Haglund 2006; Hersh 2000; Kubitzek 2003; Kiersch 1994; Laska 1983 (Study 3); Lehnert 1990; McQuay 1988; Mehlisch 1984; Mehlisch 1990; Mehlisch 1995; Moller 2000; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Rubin 1984; Sakata 1986; Santos Pereira 1986; Schachtel 1989; Seymour 1996; Seymour 2003; Winnem 1981; Winter 1983).

One study used a dose of 325 mg (Winter 1979) and one used a dose of 1500 mg (Laska 1983 (Study 3).

Thirty‐two studies enrolled participants with dental pain following extraction of at least one impacted third molar (Bentley 1987; Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1989; Cooper 1991; Cooper 1998; Dionne 1994; Dolci 1994; Edwards 2002; Forbes 1982; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Haglund 2006; Hersh 2000; Kiersch 1994; Kubitzek 2003; Lehnert 1990; Mehlisch 1984; Mehlisch 1990; Mehlisch 1995; Moller 2000; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Seymour 1996; Seymour 2003; Sunshine 1986; Winter 1979; Winter 1983).

Twenty‐three studies involved participants with pain following 'other surgical' procedures (Berry 1975; Bhounsule 1990; Bjune 1996; Edwards 2002; Fassolt 1983; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984b; Honig 1984; Jain 1986; Laska 1983 (Study 3); McQuay 1988; Pinto 1984; Rubin 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Sakata 1986; Santos Pereira 1986Schachtel 1989; Sunshine 1989; Sunshine 1993; Winnem 1981; Young 1979). These were episiotomy (8/23), caesarian section (2/23) and minor gynaecological/orthopaedic/general surgical procedures (13/23).

Study duration was four hours in 15 studies, five hours in one study, six hours in 27 studies, eight hours in two studies, and 12 hours in five studies. Information about duration was unavailable for one study (Edwards 2002), although this study allowed extraction of appropriate data for the four to six hour study period.

One study (Forbes 1990a) included a multiple dose phase, but reported results for the first dose separately for at least some relevant outcomes. All other studies used only single doses.

Risk of bias in included studies

Each of the 51 studies were scored for methodological quality.

Eleven studies were given a quality score of five (Cooper 1989; Edwards 2002; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Haglund 2006; Lehnert 1990; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Sunshine 1986).

Twenty‐five studies were given a score of four (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1998; Dolci 1994; Forbes 1984b; Hersh 2000; Jain 1986; Kiersch 1994; Kubitzek 2003; Laska 1983 (Study 3); McQuay 1988; Mehlisch 1984; Mehlisch 1990; Moller 2000; Rubin 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Schachtel 1989; Seymour 1996; Seymour 2003; Sunshine 1989; Sunshine 1993; Winnem 1981; Winter 1983; Young 1979).

Twelve studies were given a score of three (Bentley 1987; Berry 1975; Bhounsule 1990; Bjune 1996; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1982; Honig 1984; Mehlisch 1995; Pinto 1984; Santos Pereira 1986).

Three studies were given a score of two (Fassolt 1983; Sakata 1986; Winter 1979).

Full details can be found in the 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Effects of interventions

Details of study efficacy outcomes (analgesia and use of rescue medication) are in Table 1, and details of adverse events and withdrawals are in Table 2. Summary tables are provided within the text.

1. Summary of Outcomes: analgesia and use of rescue medication.

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGE: very good or excellent | Time to use (hr) | % using |

| Bentley 1987 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=41 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 1000/60 mg, n=41 (3) Codeine 60 mg, n=21 (4) Placebo, n=17 |

TOTPAR 5: (1) 8.7 (4) 4.9 |

(1) 19/41 (4) 4/17 |

No data | Median: (1) 3.3 (4) 1.4 |

at 4 hrs: (1) 68 (4) 81 |

| Berry 1975 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=76 (2) Propoxyphene, 65 mg, n=73 (3) Placebo, n=76 |

non standard scales | (1) 63/76 (3) 18/76 |

Global rating > good: (1) 63/76 (3) 18/76 |

No data | at 4 hrs: (1) 2 (3) 17 |

| Bhounsule 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=20 (3) Aspirin 600 mg, n=20 (4) Analgin 500 mg, n=20 (5) Placebo, n=20 |

SPID 6: (1) 5.4 (5) 4.4 |

(1) 7/20 (5) 6/20 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Bjune 1996 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=50 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 800/60 mg, n=50 (3) Placebo, n=25 |

TOTPAR 6: severe pain (1) 6.4 (3) 0 moderate pain (1) 8.0 (3) 1.5 |

(1) 12/43 (3) 0/21 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Cooper 1980 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=37 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg, n=42 (3) Paracetamol+oxycodone 500/5 mg, n=45 (4) Paracetamol+oxycodone 1000/5 mg, n=40 (5) Paracetamol+oxycodone 1000/10 mg, n=45 (6) Placebo, n=38 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 5.1 (6) 4.8 |

(1) 11/37 (6) 11/38 |

No data | Mean: (1) 2.8 (6) 2.5 |

No data |

| Cooper 1981 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=37 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=42 (3) Paracetamol+d‐propoxyphene 650/100 mg, n=42 (4) Ibuprofen 200 mg, n=42 (5) Placebo, n=37 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.2 (3) 3.4 |

(1) 21/37 (5) 6/37 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 3.5 (5) 2.9 |

at 4 hrs: (1) 5 (5) 54 |

| Cooper 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=38 (2) Paracetamol+codeine+caffeine 1000/16/30 mg, n=39 (3) Placebo, n=22 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.6 (3) 4.3 |

(1) 20/38 (3) 3/22 |

No data | Mean: (1) 4.7 (3) 3.5 |

No data |

| Cooper 1988 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=36 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600+60 mg, n=31 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.0 (3) 6.3 |

(1) 12/36 (3) 9/40 |

(1) 12/36 (3) 8/40 |

No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 78 (3) 82 |

| Cooper 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=59 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=61 (3) Placebo, n=64 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.2 (3) 4.7 |

(1) 27/59 (3) 9/64 |

(1) 16/59 (3) 4/64 |

Median: (1) 3.7 (3) 2.3 Mean: (1) 4.1 (3) 3.3 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 63 (3) 78 |

| Cooper 1991 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=37 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=39 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n=23 (4) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=42 (5) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=41 (6) Placebo, n=44 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.8 (6) 5.7 |

(1) 10/37 (6) 9/44 |

(1) 3/37 (6) 2/44 |

Mean: (1) 3.2 (6) 3.1 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 95 (6) 84 |

| Cooper 1998 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg n=50 (2) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n=51 (3) Ketoprofen 1000 mg, n=50 (4) Placebo, n=26 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.2 (4) 4.5 |

(1) 17/50 (4) 3/26 |

No data | median: (1) 3.3 (4) 1.7 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 60 (4) 78 |

| Dionne 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=27 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=24 (3) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=25 (4) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=22 (5) Placebo, n=25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 18.4 (5) 14.9 |

(1) 24/27 (5) 18/25 |

No usable data | no data | no data |

| Dolci 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=72 (2) Piroxicam 20 mg, n=76 (3) Piroxicam cyclodextrin =20 mg, n=74 (4) Placebo, n=76 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 10.5 (6) 5.4 |

(1) 54/72 (4) 25/76 |

No usable data | no data | at 4 hrs: (1) 15/72 (4) 46/76 |

| Edwards 2002 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=340 (2) Placebo, n=339 5 dental studies included in meta‐analysis |

TOTPAR 6: values not given |

(1) 108/340 (2) 14/339 |

(1) 110/340 (2) 34/337 |

No data | 1) 9 2) 36 |

| Edwards 2002 | (1) Paracetamol 975 mg, n=100 (2) Placebo, n=100 2 gynae or ortho studies in meta‐analysis |

TOTPAR 6: values not given |

(1) 45/100 (2) 25/100 |

(1) 37/100 (2) 22/100 |

No data | 1) 3 2) 1 |

| Fassolt 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=29 (2) Suprofen 200 mg, n=32 (3) Suprofen 400 mg, n=28 (4) Paracetamol+suprofen 650/100 mg, n=29 (5) Placebo, n=28 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 15.1 (5) 7.5 |

(1) 21/29 (5) 8/28 |

(1) 21/29 (5) 5/27 |

No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 4/29 (5) 19/28 |

| Forbes 1982 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=34 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=31 (3) Diflusinal 500 mg, n=32 (4) Diflusinal 1000 mg, n=32 (5) Placebo, n=30 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.9 (5) 3.8 |

(1) 15/34 (5) 6/30 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 3.5 (5) 2.4 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 70 (5) 82 |

| Forbes 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=26 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=26 (3) Diflusinal 500 mg, n=26 (4) Diflusinal 1000 mg, n=28 (5) Placebo, n=26 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.2 (5) 5.4 |

(1) 13/26 (5) 5/26 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 4.0 (5) 1.9 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 73 (5) 86 |

| Forbes 1984a | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=39 (2) Phenyltoloxamine 60 mg, n=33 (3) Patacetamol+phenyltoxolamine 650/60 mg, n=40 (4) Placebo, n=36 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.7 (4) 2.1 |

(1) 10/39 (4) 0/36 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 4.3 (4) 2.7 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 74 (4) 97 |

| Forbes 1984b | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=31 (2) Nalbuphine 30 mg, n=32 (3) Paracetamol+nalbuphine 650/30 mg, n=33 (4) Placebo, n=33 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.5 (4) 4.5 |

(1) 11/31 (4) 4/33 |

No usable data | No data | No data |

| Forbes 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=22 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=17 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=26 (4) Placebo, n=23 |

(1) 4.6 (4) 2.0 |

(1) 1/22 (4) 0/23 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 2.8 (4) 1.7 |

at 4 hrs: (1) 82 (4) 91 |

| Forbes 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=36 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=38 (3) Ketorolac 10 mg, n=31 (4) Ketorolac 20 mg, n=35 (5) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=32 (6) Placebo, n=34 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 5.8 (6) 1.9 |

(1) 7/3 (6) 0/34 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 3.0 (6) 1.8 Mean: (1) 3.9 (6) 2.9 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 81 (6) 97 |

| Haglund 2006 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Rofecoxib+paracetamol 50/1000 mg, n=34 (3) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n=36 (4) Placebo n=17 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.5 (4) 0.25 |

(1) 10/20 (4) 0/17 |

No usable data | Median: (1) >8 (4) 1.5 |

At 8 hrs: (1) 40.0 (4) 71 At 6 hrs: (1) 24 (4) 70 |

| Hersch 2000 | (1) Paracetamol capsule 1000 mg, n=63 (2) Ibuprofen liquigel 200 mg, n=61 (3) Ibuprofen liquigel, 400 mg n=59 (4) Placebo, n=27 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.99 (4) 5.25 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 52% (4) 14% |

Median: (1) 6 (4) 1.63 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 50 (4) 75 |

|

| Honig 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 28 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=28 (3) Codeine 60 mg, n=28 (4) Placebo, n = 25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) value not given (4) 8.9 |

(1) 11/28 (4) 6/30 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 8/28 (4) 4/25 |

No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 16/28 (4) 114/30 |

| Jain 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=30 (2) Nalbuphine 30 mg, n=34 (3) Paracetamol+nalbuphine 650/30 mg, n=32 (4) Placebo, n=32 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.4 (4) 7.9 |

(1) 13/29 (4) 10/30 |

No data | No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 10/30 (4) 11/32 |

| Kiersch 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=92 (2) Naproxen Na 440 mg, n=89 (3) Placebo, n=45 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.2 (3) 3.1 |

(1) 21/92 (3) 3/45 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 3.1 (3) 2.0 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 69 (3) 85 |

| Kubitzek 2003 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=78 (2) Diclofenac K 25 mg, n=83 (3) Placebo, n=84 |

TOTPAR 6: values not given |

At 6 hrs: (1) 45/78 (3) 7/84 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 17/78 (3) 1/84 |

Median: (1) 4.2 (3) 1.5 |

at 6h: (1) 76 (3) 89 |

| Laska 1983 (Study 3) | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=81 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=81 (3) Paracetamol 1500 mg, n=81 (4) Placebo, n=57 |

%max SPID: (1) 43 (2) 46.4 (3) 49.8 (4) 29.9 |

(1) 46/81 (2) 49/81 (3) 53/81 (4) 22/57 |

No data | not estimable | at 4 hrs: None |

| Lenhert 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=49 (2) Aspirin 1000 mg, n=45 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

SPID 6: (1) 5.8 (3) 1.5 |

(1) 24/49 (3) 5/40 |

No usable data | No data | No data |

| McQuay 1988 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=30 (2) Bromfenac 5 mg, n=30 (3) Bromfenac 10 mg, n=30 (4) Bromfenac 25 mg, n=30 (5) Placebo, n=30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.9 (5) 4.1 |

(1) 10/30 (5) 3/30 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 3.7 (5) 3.0 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 63 (5) 87 |

| Mehlisch 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=58 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n=49 (3) Placebo, n=55 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.0 (3) 1.8 |

(1) 16/58 (3) 0/55 |

No usable data | No data | at 6hrs: (1) 45/58 (3) 52/55 |

| Mehlisch 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=306 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=306 (3) Placebo, n=85 |

(1) 4.1 (3) 1.2 |

(1) 131/306 (3) 9/85 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Mehlisch 1995 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=101 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=98 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

(1) 8.4 (3) 2.6 |

(1) 35/101 (3) 1/40 |

(1) 31/101 (3) 1/40 |

Median: (1) 4.2 (3) 1.4 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 60 (3) 88 |

| Moller 2000 | (1) Paracetamol tablet 1000 mg, n=60 (2) Placebo tablet, n=60 (3) Paracetamol effervescent 1000 mg, n = 60 (4) Placebo effervescent, n=62 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 4.4 (2) 0.8 (3) 3.7 (4) 0.8 |

(1) 15/60 (2) 0/60 (3) 12/60 (4) 0/62 |

No usable data | Median: (1) 2.7 (2) 1.0 (3) 2.1 (4) 1.0 |

(1) 73 (2) 93 (3) 85 (4) 100 |

| Moller 2005 | (1) Paracetamol tablet 1000 mg, n=50 (2) Propacetamol 2000 mg iv bolus, n=50 (3) Propacetamol 2000 mg 15 min infusion, n=50 (4) Placebo, n=25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.4 (4) 5.0 |

(1) 22/50 (4) 4/25 |

No data | Median: (1) 4.6 (4) 1.1 |

No data |

| Olson 2001 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=66 (2) Ibuprofen liquigel 400 mg, n=67 (3) Ketoprofen 25 mg, n=67 (4) Placebo, n=39 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 13.3 (4) 4.3 |

(1) 41/66 (4) 5/39 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 57% (4) 11% |

Median: (1) >6 (4) 1.3 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 25/66 (4) 31/39 |

| Pinto 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n = 29 (2) Dipyrone 500 mg, n=29 (3) Placebo, n = 29 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 11.4 (3) 5.6 |

(1) 24/29 (3) 10/29 |

No usable data | No data | at 4 hrs: (1) 0 (3) 28 |

| Rubin 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=123 (2) Paracetamol+aspirin 648/648 mg, n=123 (3) Aspirin+caffeine 800/6.5 mg, n=121 (4) Placebo, n=109 |

%max SPID: (1) 53.3 (4) 36.6 |

(1) 86/123 (4) 52/109 |

no data | no data | at 4 hrs: (1) 1/123 (4) 15/109 |

| Rubinstein 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=30 (2) Dypyrone 500 mg, n=30 (3) Placebo, n=30 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 10.1 (3) 4.7 |

(1) 22/30 (3) 8/30 |

No usable data | No data | at 4 hrs: (1) 7 (3) 20 |

| Sakata 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=30 (2) Dipyrone 1000 mg, n=30 (3) Placebo, n=27 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.4 (3) 2.8 |

(1) 17/30 (3) 3/27 |

No usable data | No data | No data |

| Santos Pereira 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=28 (2) Dipyrone 1000 mg, n=28 (3) Placebo, n=29 |

SPID 4: (1) 6.4 (3) 2.1 |

(1) 22/28 (3) 7/29 |

No usable data | No data | (1) 0 (3) 38 |

| Schachtel 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=37 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=36 (3) Placebo, n=38 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.9 (3) 5.5 |

(1) 20/37 (3) 13/38 |

No usable data | No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 35 (3) 58 |

| Seymour 1996 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg n=41 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg n=41 (3) Ketoprofen 12.5 mg n=42 (4) ketoprofen 25 mg n=41 (5) Placebo, n=41 |

VAS SPID 6: (1) 135.4 (2) 150.0 (5) 75 |

(1) 19/41 (2) 21/41 (5) 10/41 |

at 6 hr: (1) 15/41 (2) 23/41 (5) 8/41 |

Median: (1) 2.8 (2) 4.1 (5) 1.8 |

(1) 32/40 (2) 33/40 (5) 38/39 |

| Seymour 2003 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=62 (2) Aspirin (soluble) 900 mg, n=59 (3) Placebo, n=32 |

SPID 4 (VAS): (1) 40.7 (3) 22.6 |

(1) 13/62 (3) 3/32 |

at 4 hrs: (1) 53% (3) 10% |

Median: (1) 1.6 (3) 1.1 |

At 4 hrs: (1) 74% (3) 91% |

| Sunshine 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=30 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=31 (3) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=31 (4) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=29 (5) Zomepirac 100 mg, n=31 (6) Placebo, n=30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.1 (6) 8.3 |

(1) 15/30 (6) 10/30 |

No usable data | No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 47 (6) 43 |

| Sunshine 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=75 (2) Paracetamol+phenyltoloxamine 650/60 mg, n=75 (3) Placebo, n=50 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.3 (3) 2.2 |

(1) 22/75 (3) 0/50 |

No usable data | No data | at 6 hrs: (1) 3 (3) 16 |

| Sunshine 1993 | (1) Paracetamol 650mg, n=48 (2) Paracetamol+oxycodone 650/10 mg, n=48 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n=48 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n=48 (5) Placebo, n=48 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.4 (5) 9.7 |

(1) 22/48 (5) 20/48 |

No usable data | Of pts with onset: Median: (1) 7 .0 (5) 6.0 No usable data |

at 8 hrs: (1) 88 (5) 73 |

| Winnem 1981 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Tiaramide 100 mg, n=20 (3) Tiaramide 200 mg, n=19 (4) Placebo, n=20 |

SPID 6: (1) 4.3 (4) 1.7 |

(1) 9/20 (4) 3/20 |

No data | No usable data | at 6 hrs: (1) 24 (4) 45 |

| Winter 1979 | (1) Paracetamol 325 mg, n=49 (2) Orphenadrine 25 mg, n=50 (3) Paracetamol+orphenadrine 325/25 mg, n=50 (4) Placebo, n=51 |

SPID 6: (1) 9.5 (4) 5.9 |

(1) 34/49 (4) 22/51 |

No data | Mean: (1) 3.1 (4) 2.9 |

at 6 hrs: (1) 67 (4) 75 |

| Winter 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=41 (2) Paracetamol+caffeine 1000/130 mg, n=40 (3) Caffeine 130 mg, n=42 (4) Placebo, n=41 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 7.4 (4) 4.0 |

(1) 20/41 (4) 9/41 |

No data | No data | at 4 hrs: (1) 2 (4) 2 |

| Young 1979 | Study 1: (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=30 (2 Paracetamol+butorphanol 650/4 mg, n=30 (3) Butorphanol 4 mg, n=30 (4) Placebo, n=29 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 7.3 (4) 7.2 |

(1) 15/30 (4) 14/29 |

No usable data | No data | No data |

2. Summary of Outcomes: adverse events and withdrawals.

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Bentley 1987 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=41 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 1000/60 mg, n=41 (3) Codeine 60 mg, n=21 (4) Placebo, n=17 |

(1) 21/42 (4) 9/19 |

None reported | None reported | 7 excluded form efficacy analysis due to invalid data, 1 did not return forms |

| Berry 1975 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=76 (2) Propoxyphene 65 mg, n=73 (3) Placebo, n=76 |

None related to medication | None reported | None reported | None reported |

| Bhounsule 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=20 (3) Aspirin 600 mg, n=20 (4) Analgin 500 mg, n=20 (5) Placebo, n=20 |

None related to medication | None reported | None reported | None |

| Bjune 1996 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=50 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 800/60 mg, n=50 (3) Placebo, n=25 |

(1) 10/50 (3) 1/25 |

None | None | 7 paracetamol, 4 placebo pts excluded due to invalid data |

| Cooper 1980 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=37 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg, n=42 (3) Paracetamol+oxycodone 500/5 mg, n= 5 (4) Paracetamol+oxycodone 1000/5 mg, n=40 (5) Paracetamol+oxycodone 1000/10 mg, n=45 (6) Placebo, n=38 |

(1) 3/37 (6) 6/38 |

None reported | None reported | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Cooper 1981 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=37 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=42 (3) Paracetamol+d‐propoxyphene 650/100 mg, n=42 (4) Ibuprofen 200 mg, n=42 (5) Placebo, n=37 |

(1) 12/37 (5) 4/37 |

None | None | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Cooper 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=38 (2) Paracetamol+codeine+caffeine 1000/16/30 mg, n=39 (3) Placebo, n=22 |

No data | None | None | 6 paracetamol, 1 placebo excluded due to invalid data |

| Cooper 1988 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=36 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600+60 mg, n=31 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

No data | No data | None | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Cooper 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=59 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=61 (3) Placebo, n=64 |

(1) 11/63 (3) 7/64 |

None | None | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Cooper 1991a | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=37 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=39 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n=23 (4) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=42 (5) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=41 (6) Placebo, n=44 |

(1) 6/37 (6) 7/44 |

None reported | None reported | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Cooper 1998 | (1) Paracetamol 1000mg n=50 (2) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n=51 (3) Ketoprofen 1000 mg, n=50 (4) Placebo n=26 |

(1) 25/50 (4) 4/26 |

None | None | None |

| Dionne 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=27 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=24 (3) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=25 (4) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=22 (5) Placebo, n=25 |

(1) 7/27 (5) 9/24 |

None reported | None reported | 11 excluded from analysis: enrolled twice, early rescue medication, asleep during observations, lost to follow up |

| Dolci 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=72 (2) Piroxicam 20 mg, n=76 (3) Piroxicam cyclodextrin =20 mg, n=74 (4) Placebo, n=76 |

(1) 7/80 (4) 6/82 |

None reported | (1) 2/80 (4) 1/82 |

Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Edwards 2002 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=340 (2) Placebo, n=339 5 dental studies included in meta‐analysis |

(1) 54/340 (2) 58/337 |

None reported | (1) 1/340 (2)2/337 |

No data |

| Edwards 2002 | (1) Paracetamol 975 mg, n=100 (2) Placebo, n=100 2 gynae or ortho studies in meta‐analysis |

No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Fassolt 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=29 (2) Suprofen 200 mg, n=32 (3) Suprofen 400 mg, n=28 (4) Paracetamol+suprofen 650/100 mg, n=29 |

No data | None reported | No data | No data |

| Forbes 1982 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=34 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=31 (3) Diflusinal 500 mg, n=32 (4) Diflusinal 1000 mg, n=32 (5) Placebo, n=30 |

No usable data | None | None | None reported |

| Forbes 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=26 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=26 (3) Diflusinal 500 mg, n=26 (4) Diflusinal 1000 mg, n=28 (5) Placebo, n=26 |

(1) 11/26 (5) 4/26 |

None reported | None | None |

| Forbes 1984a | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=39 (2) Phenyltoloxamine 60 mg, n=33 (3) Patacetamol+phenyltoxolamine 650/60 mg, n=40 (4) Placebo, n=36 |

(1) 1/423 (4) 2/40 |

None | None | Exclusions due to invalid data, numbers not given per group |

| Forbes 1984b | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=31 (2) Nalbuphine 30 mg, n=32 (3) Paracetamol+nalbuphine 650/30 mg, n=33 (4) Placebo, n=33 |

(1) 9/33 (4) 8/33 |

None | None | Three pts excl from efficacy analysis due to invalid data |

| Forbes 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=22 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=17 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=26 (4) Placebo, n=23 |

(1) 3/26 (4) 4/26 |

None | None | 10 pts excl from efficacy analysis due to invalid data |

| Forbes 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n=36 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=38 (3) Ketorolac 10 mg, n=31 (4) Ketorolac 20 mg, n=35 (5) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=32 (6) Placebo, n=34 |

(1) 5/41 (6) 0/38 |

None | None | 37 pts excl from efficacy analysis due to invalid data |

| Haglund 2006 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Rofecoxib/paracetamol 50/1000mg, n=34 (3) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n=36 (4) Placebo, n=17 |

No usable data | None | None reported | 5 ‐ inadequately filled in questionnaires. Not included in final analysis |

| Hersch 2000 | (1) Paracetamol capsule 1000 mg, n=63 (2) Ibuprofen liquigel 200 mg, n=61 (3) Ibuprofen liquigel 400 mg n=59 (4) Placebo, n=27 |

(1) 12/63 (4) 7/27 |

None | None | None |

| Honig 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 28 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 600/60 mg, n=28 (3) Codeine 60 mg, n=28 (4) Placebo, n=25 |

No data | none | None reported | None reported |

| Jain 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=30 (2) Nalbuphine 30 mg, n=34 (3) Paracetamol+nalbuphine 650/30 mg, n=32 (4) Placebo, n=32 |

(1) 9/30 (4) 6/32 |

None reported | None reported | 6 pts excl from efficacy analysis due to invalid data |

| Kiersch 1994 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=92 (2) Naproxen Na 440 mg, n=89 (3) Placebo, n=45 |

(1) 31/94 (3) 13/45 |

None | (1) 2/94 (vomiting within 10 mins) (3) 0/45 |

None |

| Kubitzek 2003 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=78 (2) Diclofenac K 25 mg, n= 83 (3) Placebo, n=84 |

48 hrs: (1) 4/78 (3) 2/84 |

None | None | 1 in placebo group due to dosing protocol violation |

| Laska 1983 (Study 3) | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=81 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=81 (3) Paracetamol 1500 mg, n=81 (4) Placebo, n=57 |

No data | No data | None reported | Various protocol violations ‐ groups not given |

| Lenhert 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=49 (2) Aspirin 1000 mg, n=45 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

(1) 5/49 (2) 4/40 |

None reported | None reported | 11 did not take the medication, 3 were lost to follow up and 3 for various protocol violations. |

| McQuay 1988 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=30 (2) Bromfenac 5 mg, n=30 (3) Bromfenac 10 mg, n=30 (4) Bromfenac 25 mg, n=30 (5) Placebo, n=30 |

(1) 6/30 (2) 6/30 |

None | None reported | 8 excluded from analysis due to invalid data |

| Mehlisch 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=58 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n=49 (3) Placebo, n=55 |

No usable data | No data | None | 162 analysed. Exclusions: 9 failed to comply with protocol & 3 were lost to follow up. |

| Mehlisch 1990 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=306 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=306 (3) Placebo, n=85 |

(1) 32/307 (3) 12/85 |

None reported | None reported | 2 Paracetamol lost to follow up, 1 Paracetamol entered in trial twice (invalid data) |

| Mehlisch 1995 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=101 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=98 (3) Placebo, n=40 |

(1) 17/101 (3) 4/40 |

None | None | None |

| Moller 2000 | (1) Paracetamol tablet 1000 mg, n=60 (2) Placebo tablet, n=60 (3) Paraceamol effervescent 1000 mg, n=60 (4) Placebo effervescent, n=62 |

(1) 24/60 (2) 21/60 (3) 24/60 (4) 35/60 |

None | None reported | None |

| Moller 2005 | (1) Paracetamol tablet 1000 mg, n=50 (2) Propacetamol 2000 mg iv bolus, n=50 (3) Propacetamol 2000 mg 15 min infusion, n=50 (4) Placebo, n=25 |

At 7 days: (1) 21/50 (4) 12/25 |

1 in propacetamol iv bolus group | None | None |

| Olson 2001 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=66 (2) Ibuprofen liquigel 400 mg, n=67 (3) Ketoprofen 25 mg, n=67 (4) Placebo, n=39 |

At 6 hrs: (1) 10/66 (4) 2/39 |

None | None | None |

| Pinto 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=29 (2) Dipyrone 500 mg, n=29 (3) Placebo, n=29 |

(1) 0/29 (3) 0/29 |

None reported | No data | No data |

| Rubin 1984 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=123 (2) Paracetamol+aspirin 648/648 mg, n=123 (3) Aspirin+caffeine 800/6.5 mg, n=121 (4) Placebo, n=109 |

(1) 6/123 (4) 6/109 |

None | None | None |

| Rubinstein 1986 | 1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=30 2) Dypyrone 500 mg, n=30 3) Placebo, n=30 |

(1) 1/30 (3) 0/30 |

None reported | None | None |

| Sakata 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=30 (2) Dipyrone 1000 mg, n=30 (3) Placebo, n=27 |

No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Santos Pereira 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=28 (2) Dipyrone 1000 mg, n=28 (3) Placebo, n = 29 |

No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Schachtel 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=37 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n=36 (3) Placebo, n=38 |

None | None | None | None |

| Seymour 1996 | (1) Paracetamol 500 mg, n=41 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=41 (3) Ketoprofen 12.5 mg, n= 42 (4) ketoprofen 25 mg, n=41 (5) Placebo, n=41 |

No patients reported any AE | None | None | 2 placebo, 1 from each paracetamol group excl from efficacy analysis due to early rescue medication |

| Seymour 2003 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=62 (2) Aspirin (soluble) 900 mg, n=59 (3) Placebo, n=32 |

At 4 hrs: (1) 39/62 (3) 28/32 |

None reported | None reported | None |

| Sunshine 1986 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=30 (2) Paracetamol+codeine 650/60 mg, n=31 (3) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n=31 (4) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n=29 (5) Zomepirac 100 mg, n=31 (6) Placebo, n=30 |

(1) 1/30 (6) 1/30 |

None | None | None |

| Sunshine 1989 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=75 (2) Paracetamol+phenyltoloxamine 650/60 mg, n=75 (3) Placebo, n=50 |

(1) 0/75 (3) 0/50 |

None | None | None |

| Sunshine 1993 | (1) Paracetamol 650 mg, n=48 (2) Paracetamol+oxycodone 650/10 mg, n=48 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n=48 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n=48 (5) Placebo, n=48 |

No details for single dose phase | No cases of possible clinical concern | None reported | None |

| Winnem 1981 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=20 (2) Tiaramide 100 mg, n=20 (3) Tiaramide 200 mg, n=19 (4) Placebo, n=20 |

None | None | None | 1 excl from analysis for vomiting medication within 30 mins. |

| Winter 1979 | (1) Paracetamol 325 mg, n=49 (2) Orphenadrine 25 mg, n=50 (3) Paracetamol+orphenadrine 325/25 mg, n=50 (4) Placebo, n=51 |

(1) 0/49 (4) 1/51 |

None | None | None reported |

| Winter 1983 | (1) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n=41 (2) Paracetamol+caffeine 1000/130 mg, n=40 (3) Caffeine 130 mg, n=42 (4) Placebo, n=41 |

(1) 0/41 (4) 1/41 |

None | None | None reported |

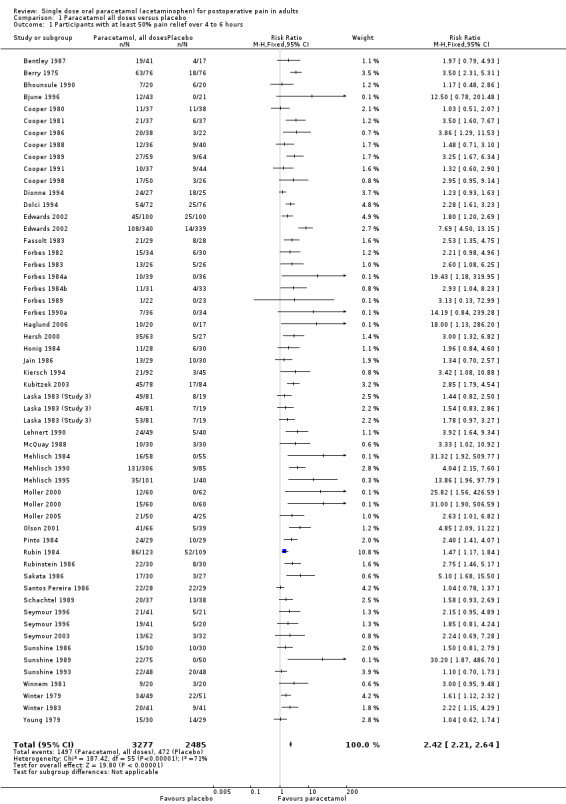

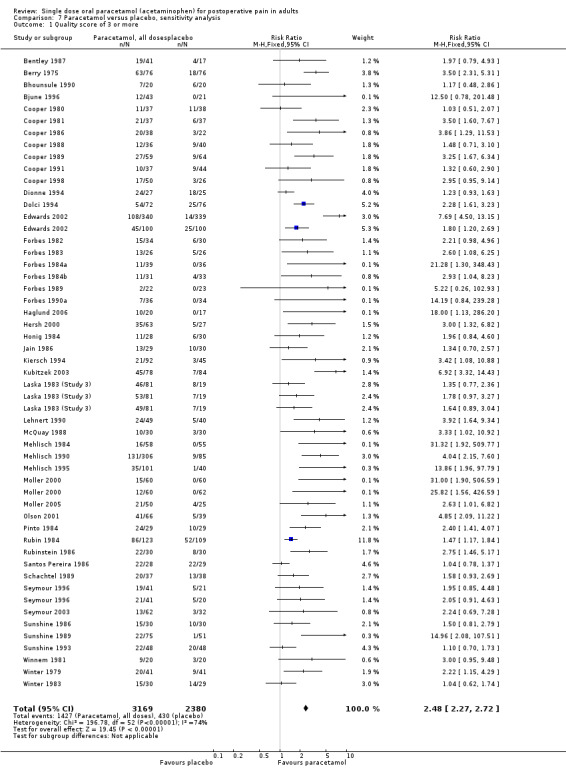

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Paracetamol (all doses) versus placebo

(seeTable 1, Summary of results A)

Fifty‐one studies provided data. There were 3277 participants who were treated with between 325 and 1500 mg of paracetamol and 2425 were treated with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with paracetamol (325 to 1500 mg) was 46% (1507/3277).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 20% (485/2425).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.4 (2.2 to 2.6).

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 3.9 (3.6 to 5.3). For every four participants treated with any dose of paracetamol, one would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

Data was analysed by dose of paracetamol, and for each dose the data for dental and other surgical studies was analysed separately for the purposes of sensitivity analysis.

Paracetamol 500 mg versus placebo

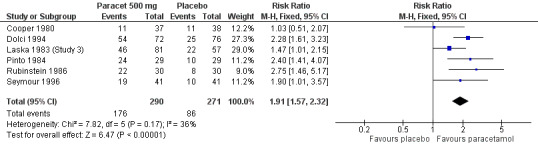

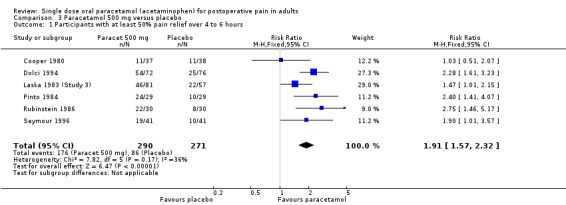

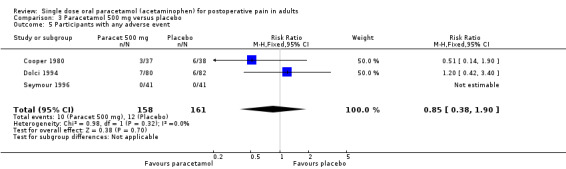

(seeTable 1; Figure 1, Summary of results A)

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Paracetamol 500 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Six studies provided data (Cooper 1980; Dolci 1994; Laska 1983 (Study 3); Pinto 1984; Rubinstein 1986; Seymour 1996). There were 290 participants who were treated with 500 mg paracetamol and 271 with placebo.

The proportion of patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with 500 mg paracetamol was 61% (176/290).

The proportion of patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 32% (86/271).

The relative benefit of paracetamol 500 mg compared with placebo was 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3).

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8). For every four participants treated with 500 mg paracetamol, one would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

For dental trials only, the relative benefit of paracetamol versus placebo was 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) and the NNT was 3.8 (2.7 to 6.4). For the other surgical trials only, the relative benefit was 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) and the NNT was 3.2 (2.3 to 5.1).

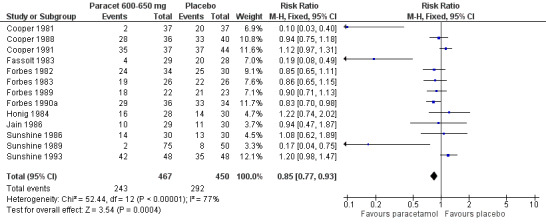

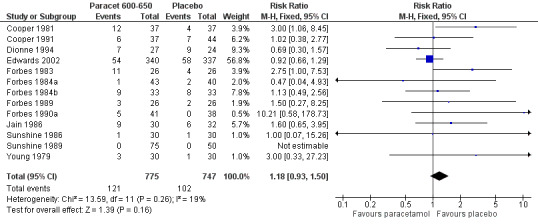

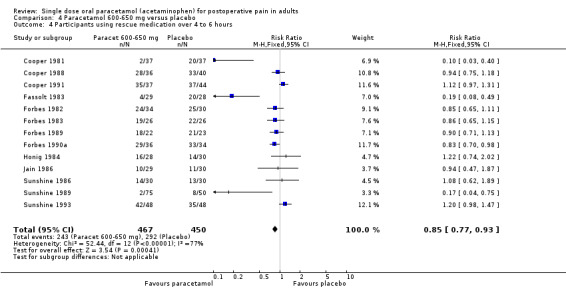

Paracetamol 600 to 650 mg versus placebo

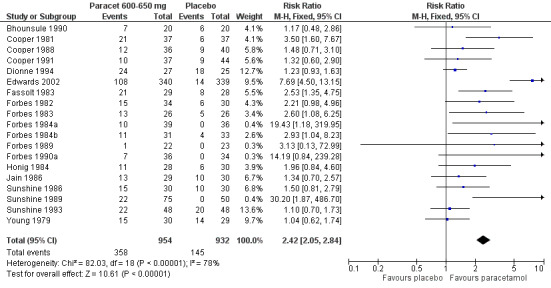

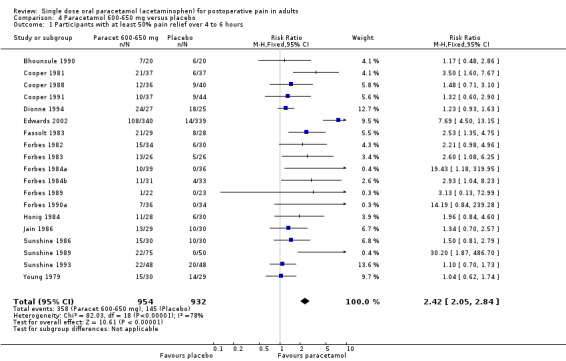

(seeTable 1; Figure 2, Summary of results A)

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Paracetamol 600‐650 mg versus placebo, outcome: 4.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Nineteen studies provided data (Bhounsule 1990; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Edwards 2002; Fassolt 1983; Forbes 1982; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1984b; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Honig 1984; Jain 1986; Sunshine 1986; Sunshine 1989; Sunshine 1993; Young 1979). There were 954 participants who were treated with 600 to 650 mg paracetamol and 932 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with 600 to 650 mg paracetamol was 38% (358/954).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 16% (145/932).

The relative benefit of paracetamol 600 to 650 mg compared with placebo was 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8).

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours was 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5). For every five participants treated with 600 to 650 mg paracetamol, one would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

For dental trials only, the relative benefit of paracetamol 600 to 650 mg versus placebo was 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) and the NNT was 4.2 (3.6 to 5.2). For the other surgical trials only, the relative benefit was 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) and the NNT was 5.6 (4.0 to 9.5).

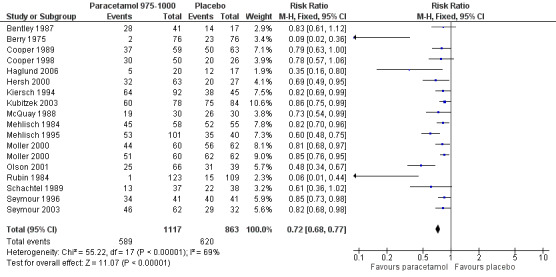

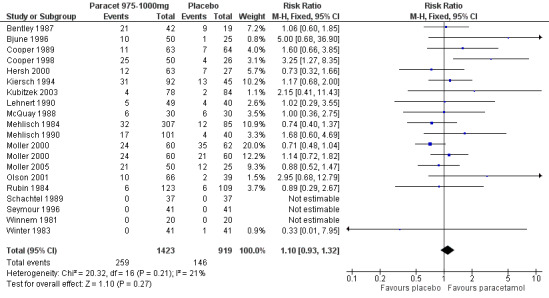

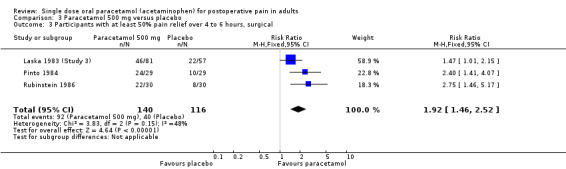

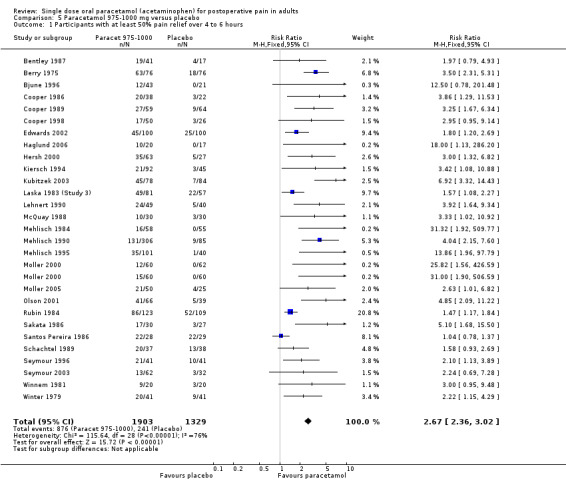

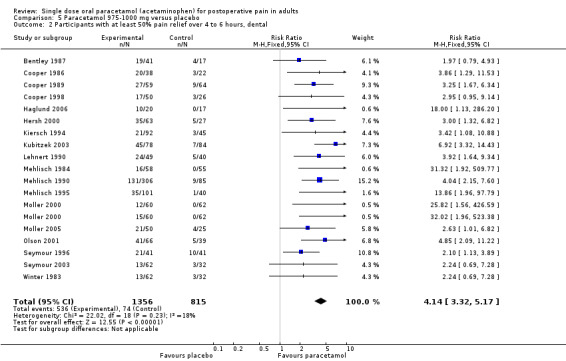

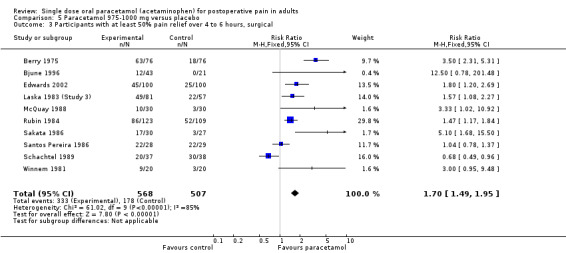

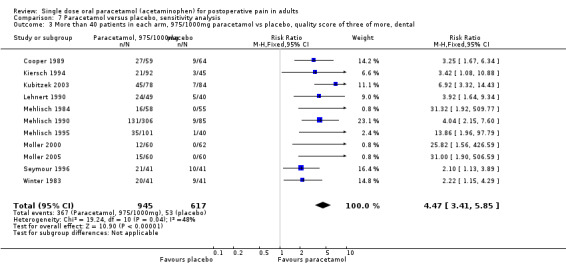

Paracetamol 975 to 1000 mg versus placebo

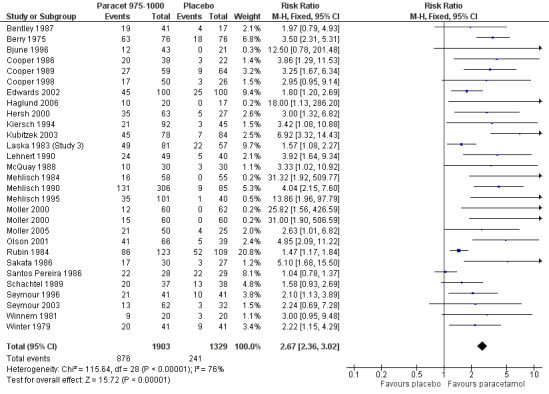

(seeTable 1; Figure 3, Summary of results A)

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Paracetamol 975‐1000 mg versus placebo, outcome: 5.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Twenty‐eight studies (29 comparisons) provided data (Bentley 1987; Berry 1975; Bjune 1996; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1989; Cooper 1998; Edwards 2002; Haglund 2006; Hersh 2000; Kiersch 1994; Kubitzek 2003; Laska 1983 (Study 3); Lehnert 1990; McQuay 1988; Mehlisch 1984; Mehlisch 1990; Mehlisch 1995; Moller 2000; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Rubin 1984; Sakata 1986; Santos Pereira 1986; Schachtel 1989; Seymour 1996; Seymour 2003; Winnem 1981; Winter 1983). There were 1903 participants who were treated with 975 to 1000 mg paracetamol and 1329 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with 975 to 1000 mg paracetamol was 46% (876/1903).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 18% (241/1329).

The relative benefit of paracetamol 975 to 1000 mg compared with placebo was 2.7 (2.4 to 3.0).

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1). For every four participants treated with 975 to 1000 mg paracetamol, one would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

For dental trials only, the relative benefit of paracetamol 975 to 1000 mg versus placebo was 4.1 (3.3 to 5.2) and the NNT was 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6). For the other surgical trials only, the relative benefit was 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) and the number needed to treat was 3.7. (3.1 to 4.7).

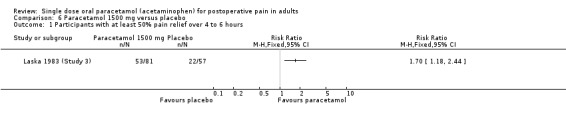

Paracetamol 325 mg and 1500 mg each had only one study.

No dose response was demonstrated for the outcome of at least 50% pain relief. Approximately four people would need to be treated with paracetamol for one to experience at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours who would not have done so with placebo.

| Summary of results A ‐ participants with at least 50% pain relief | ||||||

| Group | No of studies | Number of participants | 50% PR paracetamol | 50% PR placebo | RB (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| All (325 to 1500 mg) | 51 | 5762 | 46 | 20 | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.6) | 4.1 (3.7 to 4.5 ) |

| 500 mg All | 6 | 561 | 61 | 32 | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) | 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8) |

| 500 mg Dental | 3 | 305 | 56 | 30 | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 3.8 (2.7 to 6.4) |

| 500 mg Other surgical | 3 | 256 | 66 | 34 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) | 3.2 (2.3 to 5.1) |

| 600‐650 mg All | 19 | 1886 | 38 | 16 | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) | 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5) |

| 600‐650 mg Dental | 10 | 1276 | 35 | 12 | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) | 4.2 (3.6 to 5.2) |

| 600‐650 mg Other surgical | 9 | 610 | 43 | 25 | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | 5.6 (4.0 to 9.5) |

| 975‐1000 mg All | 28 | 3232 | 46 | 18 | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.0) | 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) |

| 975‐1000 mg Dental | 19 | 2157 | 41 | 10 | 4.1 (3.3 to 5.2) | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6) |

| 975‐1000 mg Other surgical | 10 | 1075 | 59 | 32 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | 3.7 (3.1 to 4.7) |

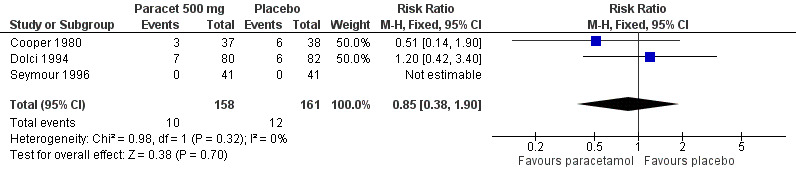

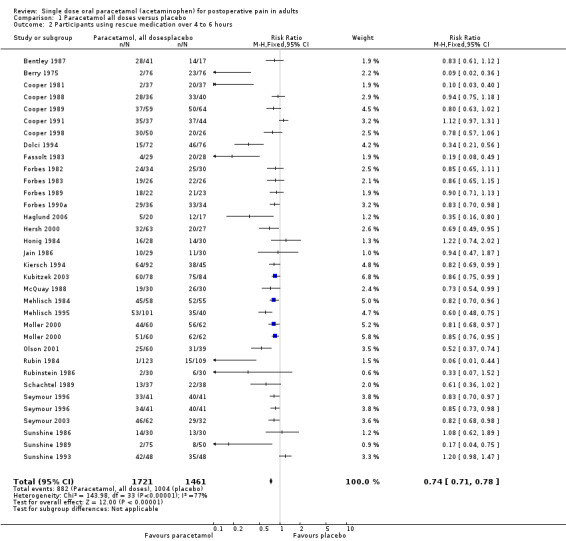

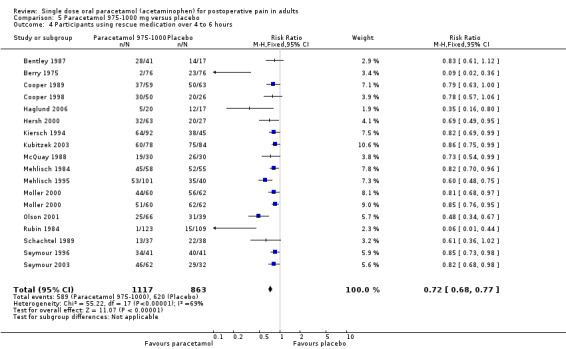

Use of rescue medication

Number of participants using rescue medication in four to six hours

(seeTable 1)

Thirty‐two of the 51 studies reported the numbers of participants using rescue medication.

For all doses of paracetamol, the weighted mean proportion of patients using rescue medication over four to six hours was 51% for patients treated with paracetamol versus 69% for those given placebo. This gives a number needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) remedication of 5.6 (4.7 to 7.0). Six participants need to be treated with paracetamol to prevent one using rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours.

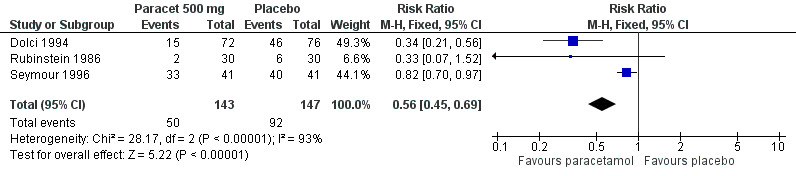

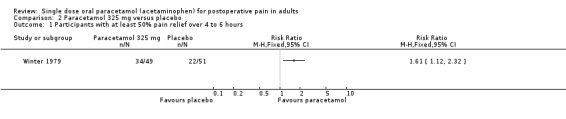

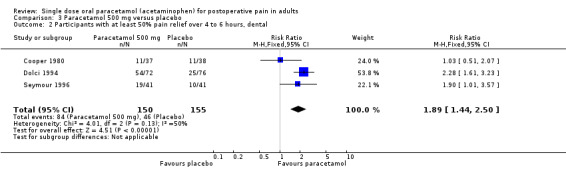

For 500 mg paracetamol, three studies reported data on use of rescue medication. The weighted mean proportion for paracetamol was 35% and for placebo 63%, giving an NNTp of 3.6 (2.6 to 6.0) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Paracetamol 500 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.4 Participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours.

For 600 to 650 mg paracetamol, 12 studies reported data on use of rescue medication. The weighted mean proportion for paracetamol was 52% and for placebo 65%, giving an NNTp of 7.8 (5.2 to 15) (Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Paracetamol 600‐650 mg versus placebo, outcome: 4.4 Participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours.

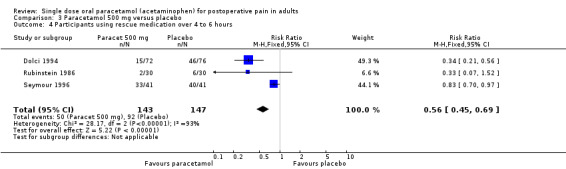

For 975 to 1000 mg paracetamol, 18 studies reported data on use of rescue medication. The weighted mean proportion for paracetamol was 53% and for placebo 72%, giving an NNTp of 5.2 (4.3 to 6.7) (Figure 6).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Paracetamol 975‐1000 mg versus placebo, outcome: 5.4 Participants using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours.

There was no clear dose response for this outcome, with 95% CIs for NNTp overlapping. Five people would need to be treated with 1000 mg paracetamol, the most commonly used dose, to prevent one needing rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours, who would have needed it with placebo.

| Summary of results B ‐ number using rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

| Dose | Studies | Participants | Paracetamol (%) | Placebo (%) | NNTp |

| All | 32 | 3079 | 51 | 68 | 5.6 (4.7 to 7.0) |

| 500 mg | 3 | 290 | 35 | 63 | 3.6 (3.0 to 6.0) |

| 600‐650 mg | 13 | 917 | 52 | 65 | 7.8 (5.2 to 15) |

| 1000 mg | 18 | 1919 | 53 | 72 | 5.2 (4.3 to 6.7) |

Time to use of rescue medication

(see Table 1, Summary of results C)

Data for the time to use of rescue medication was not available for all studies that reported the number of participants using it. A total of 17 studies reported the median, five studies the mean, and three studies both median and mean time to use of rescue medication. Median time to rescue medication varied between 2.1 and more than six hours for active treatment and 1.0 to 3.0 hours for placebo. The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 3.8 hours for paracetamol (all doses) versus 1.6 hours for placebo. Mean time to rescue medication varied between 2.8 and 4.7 hours for active treatment and 2.5 and 3.5 hours for placebo. The weighted mean of the mean times to use of rescue medication was 3.8 hours for paracetamol (all doses) versus 2.9 hours for placebo. There were insufficient data to analyse use of rescue medication by dose of paracetamol.

Half of the participants required rescue medication by 3.8 hours if treated with paracetamol, compared to 1.6 hours if treated with placebo.

| Summary of results C ‐ weighted mean of time to use of rescue medication | ||

| Weighted mean | Paracetamol (hr) | Placebo (hr) |

| Median time to rescue medication | 3.8 | 1.6 |

| Mean time to rescue medication | 3.8 | 2.9 |

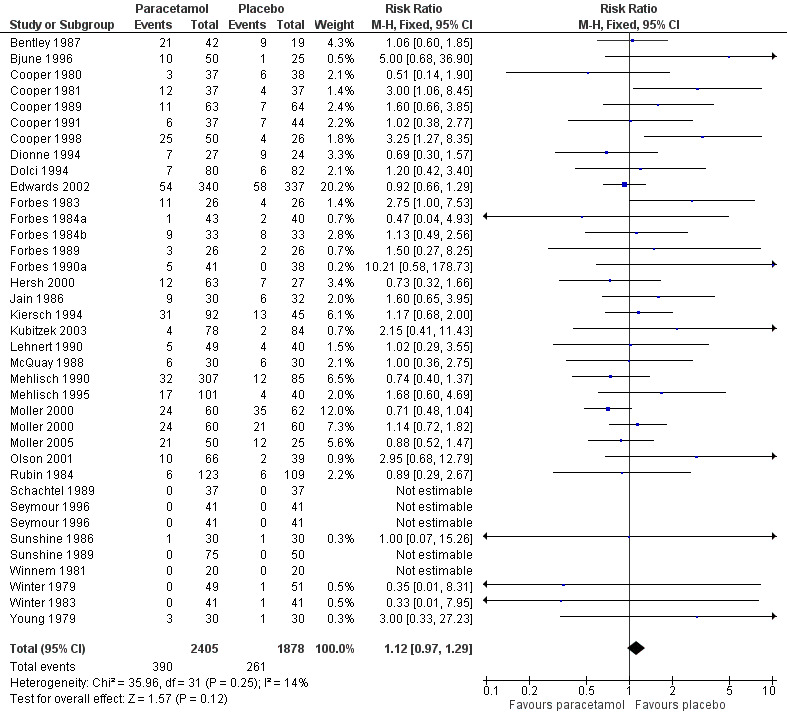

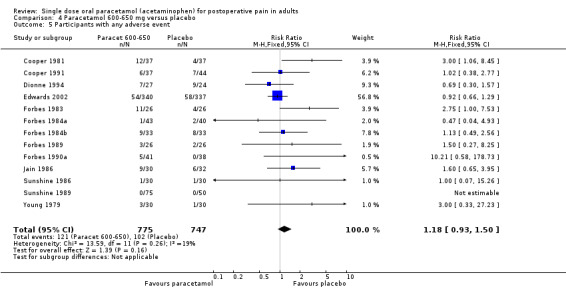

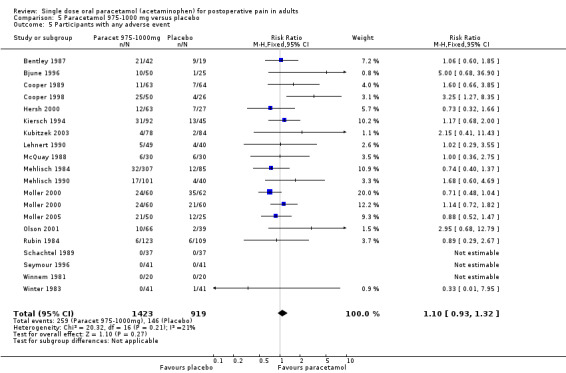

Adverse events

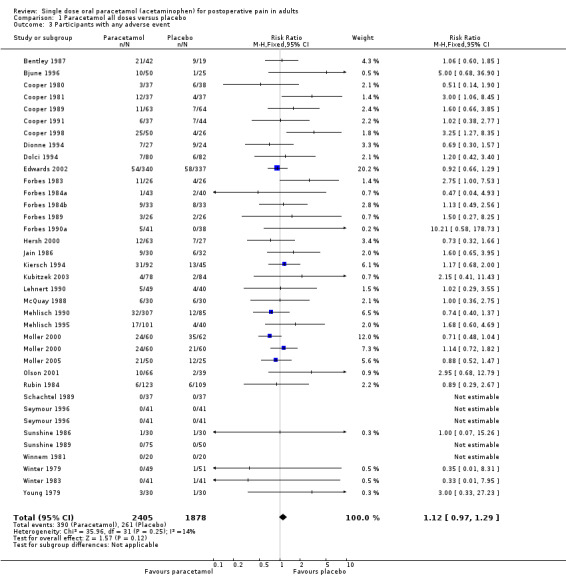

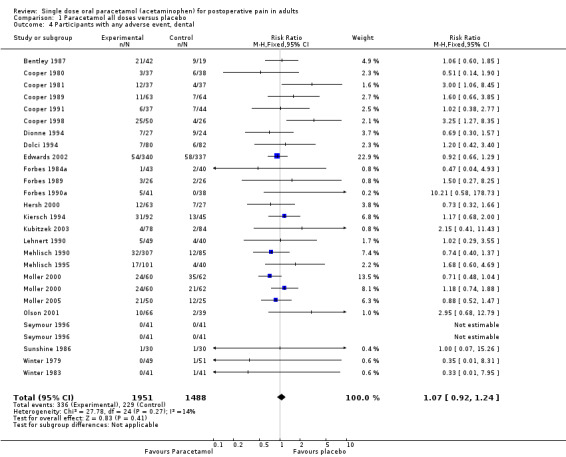

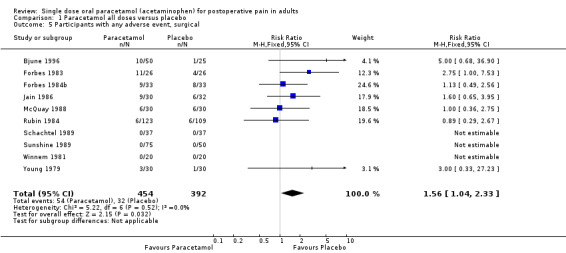

(seeTable 2; Figure 7; Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10, Summary of results D)

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Paracetamol all doses versus placebo, outcome: 1.3 Participants with any adverse event.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Paracetamol 500 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.5 Participants with any adverse event.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Paracetamol 600‐650 mg versus placebo, outcome: 4.5 Participants with any adverse event.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Paracetamol 975‐1000 mg versus placebo, outcome: 5.5 Participants with any adverse event.

Thirty‐five studies reported numbers of patients with any adverse event (Bentley 1987; Bjune 1996; Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Cooper 1989; Cooper 1991; Cooper 1998; Dionne 1994; Dolci 1994; Edwards 2002; Forbes 1983; Forbes 1984a; Forbes 1984b; Forbes 1989; Forbes 1990a; Hersh 2000; Jain 1986; Kiersch 1994; Kubitzek 2003; Lehnert 1990; McQuay 1988; Mehlisch 1990; Mehlisch 1995; Moller 2000; Moller 2005; Olson 2001; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Seymour 1996; Sunshine 1986; Sunshine 1989; Winnem 1981; Winter 1979; Winter 1983; Young 1979).

The time over which adverse event data were collected varied from four hours to seven days. It was unclear in some studies whether the adverse event reports covered the duration of the trial, or whether they included any adverse events occurring between the end of the trial and a follow‐up visit some days later. Few studies reported whether adverse event data continued to be collected after rescue medication had been taken. Reported adverse events were mainly mild and transient, and occurred at similar rates of around 16% in both paracetamol and placebo groups. There was no dose response.

One study reported a serious adverse event (Moller 2005). However, this was in a patient in a treatment arm not relevant to the review (intravenous propacetamol).

| Summary of results D ‐ participants with one or more adverse events | |||||

| Dose | Studies | Participants | Paracetamol (%) | Placebo (%) | NNH (95%CI) any AE |

| All (325 to 1500 mg) | 35 | 4283 | 16 | 14 | not calculated |

| 500 mg | 3 | 319 | 7 | 6 | not calculated |

| 600‐650 mg | 13 | 1522 | 16 | 14 | not calculated |

| 975‐1000 mg | 19 | 2342 | 18 | 16 | not calculated |

Withdrawals

(seeTable 2)

Patients who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, and are reported under 'use of rescue medication' above.

Data on other withdrawals were generally poorly reported, probably because these were single dose studies where withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy are uncommon. Some studies reported participants who had invalid data due to inadequate baseline pain, who violated a protocol, or took rescue medication within the first hour, as withdrawals or exclusions. Whether these should be included in the intention‐to‐treat population is arguable. Attrition due to invalid data is unlikely to affect results.

A total of six patients were reported as withdrawing due to adverse events: one each with nausea and vomiting after paracetamol 500 mg and one with fever, nausea and diarrhoea after placebo (Dolci 1994), two with vomiting after paracetamol 1000 mg (Kiersch 1994), and one for an unspecified reason after paracetamol 650 mg (Edwards 2002).

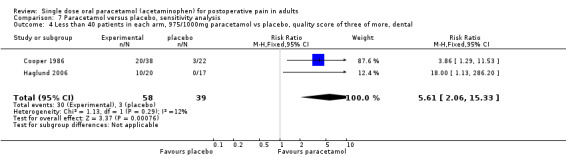

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were carried out to investigate the effect of various study characteristics on the primary efficacy outcome.

Pain model

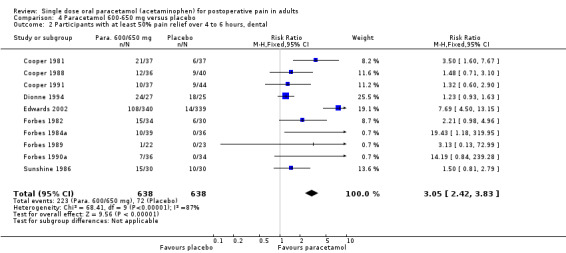

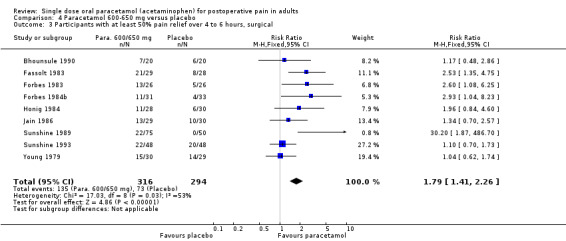

Efficacy of pain relief in dental versus other surgical pain models was analysed as part of the main efficacy analysis. There were sufficient data to perform this analysis for each dose. The results are shown with the summary of results A table in the text.

Three studies with 305 participants used 500 mg in dental pain. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 3.8 (2.7 to 6.4). Three studies with 256 participants used 500 mg paracetamol in other surgical pain, with an NNT of 3.2 (2.3 to 5.1).

Ten studies with 1276 participants used 600 to 650 mg in dental pain. The NNT was 4.2 (3.6 to 5.2). Nine studies with 610 participants used 600 to 650 mg paracetamol in other surgical pain, with an NNT of 5.6 (4.0 to 9.5).

Nineteen studies with 2157 participants used 975 to 1000 mg in dental pain. The NNT was 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6). Ten studies with 1075 participants used 975 to 1000 mg paracetamol in other surgical pain, with an NNT of 3.7 (3.1 to 4.7).

There were differences between pain models in RR, but not in NNT. Response rates for active treatment were similar in both models, but placebo response rates were lower in dental than other surgery.

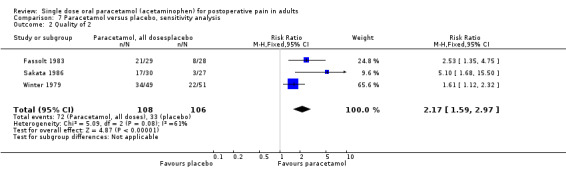

Study quality

A quality score of three out of five was considered adequate, given that for inclusion in the review each study had to score at least one point for being randomised and one for being blinded. There were insufficient numbers of participants in studies scoring less than three points to permit analysis by dose within each quality group.

Three studies with 214 participants had a quality score of less than three. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 2.8 (2.1 to 4.4). Fourty‐eight studies with 5332 participants had quality scores of three or more, giving an NNT of 3.7 (3.4 to 4.1). Trials with lower quality scores, which are more likely to be subject to bias, produced a slightly greater, but not significantly different, treatment effect, though based on relatively small numbers (Summary of results E).

Study size

A threshold of 40 or more participants in both the treatment and placebo arms was used to assess the effect of study size on the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours. Twenty‐one studies had fewer than 40 participants in both treatment arms giving an NNT of 4.3 (3.5 to 5.5), whilst 30 studies (32 comparisons) had 40 or more participants in each treatment arm giving an NNT of 3.7 (3.4 to 4.2). Restricting the analysis to studies using 1000 mg paracetamol gave an NNT of 3.3 (2.5 to 5.1) for studies with fewer than 40 participants per treatment arm, and 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) for studies with 40 or more participants per treatment arm (Summary of results E).

No significant effect of size on the primary outcome was demonstrated using 40 participants per treatment arm as the threshold.

| Summary of results E ‐ sensitivity analyses | |||||

| Study characteristic | Studies | Participants | Paracetamol % | Placebo % | NNT (95%CI) 50% PR |

| Quality of 2 | 3 | 214 | 67 | 31 | 2.8 (2.1 to 4.4) |

| Quality 3 or more | 53 | 5332 | 45 | 18 | 3.7 (3.4 to 4.1) |

| <40pts/arm (all doses) | 21 | 1236 | 45 | 22 | 4.3 (3.5 to 5.5) |

| ≥40pts/arm (all doses) | 30 | 4468 | 45 | 18 | 3.7 (3.2 to 4.2) |

| <40pts/arm, 1000 mg | 5 | 272 | 48 | 17 | 3.3 (2.5 to 5.1) |

| ≥40pts/arm, 1000 mg | 21 | 2826 | 45 | 17 | 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) |

Discussion

Since the previous review a number of new larger studies of good methodological quality have been published, all using 1000 mg of paracetamol, which is generally regarded as the most useful dose clinically. This updated review included 561 participants treated with a single dose of paracetamol 500 mg and 1886 participants treated with 600 to 650 mg, both unchanged form the previous review. For the 975 to 1000 mg dose, 3252 participants were treated, 495 more than the earlier review (Barden 2004a) giving a more robust (Moore 1998a), but almost identical result.

The primary measure of efficacy was the proportion of patients achieving at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours. This is now generally regarded as a useful level of pain relief in acute pain, and also in chronic pain conditions such as arthritis (Moore 2008a) and neuropathic pain (Straube 2008). It has the advantage that it also highlights that not all of those given an analgesic have useful pain relief, and that interventions do not work in everyone. Participants not having a useful level of pain relief are important because therapeutic failure is to be avoided. Figures and tables therefore provide percentages of patients with outcomes, as well as statistical comparisons.

There was no significant difference in the relative benefit or NNT for at least 50% pain relief by dose. Values for NNT were 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8) for 500 mg, 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5) for 600 to 650 mg , and 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) for 975 to 1000 mg. About half of participants treated with paracetamol at standard doses achieved at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, compared with about 20% treated with placebo. The differences between dental and other postsurgical pain have been noted before (Barden 2004c). Consistently lower placebo responses in the dental pain model do not effect the NNT as a measurement of efficacy. Dose response may be more sensitively determined using trials that directly compare two doses, as has been done for paracetamol 1000 mg compared with 500 mg (McQuay 2007).

Because the same methods of analyses have been used, it is possible to compare the NNT for a single dose of oral paracetamol with that of a single dose of other NSAIDs (Bandolier 2008).

Analgesics with comparable efficacy to paracetamol include ibuprofen 100 mg (NNT 3.7 (2.9 to 4.9)), celecoxib 200 mg (NNT 3.5 (2.9 to 4.4)), naproxen 200 to 220 mg (NNT 3.4 (2.4 to 5.8), and aspirin 600 to 650 mg (NNT 4.4 (4.0 to 4.9);

Analgesics with lower efficacy include codeine 60 mg (NNT 17 (11 to 48)) and tramadol 50 mg (NNT 8.3 (6.0 to 13));

Analgesics with superior efficacy include ibuprofen 200 mg (NNT 2.7 (2.5 to 2.9)), naproxen 500 mg (NNT 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3)), diclofenac 50 mg (NNT 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1)), celecoxib 400 mg (NNT 2.1 (1.8 to 2.5), and etoricoxib 180 to 240 mg (NNT 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7)).

We have effective analgesics, but clinical practice finds it difficult to use effective analgesics effectively. More immediately relevant outcomes are needed than relative benefit and even numbers needed to treat. One is the time before participants with adequate pain relief require additional analgesic because the pain has returned. This can be measured in terms of the mean or median time to remedication, or the percentage of participants needing more analgesic over a particular time. This update includes both these outcomes. Previous versions of this review have not reported data on participants using rescue medication, and not all studies (32/51) provided this information.

The median time to use of rescue medication varied greatly between trials, particularly for the active treatment arms, but was generally longer for paracetamol than placebo. The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication (all doses of paracetamol) at 3.8 hours is equal to or shorter than most non‐selective NSAIDs (diclofenac 50 mg 3.8 hours, ibuprofen 400 mg 5.3 hours, naproxen 9.8 hours) and much shorter than etoricoxib 120 mg and rofecoxib 50 mg (20 hours or more). There was insufficient data to analyse this by separate paracetamol dose, as not all studies reporting number of patients remedicating also reported this outcome. However, the short time to remedication is unlikely to be a result of the over‐representation of low dose studies providing median time to use of rescue medication data (those using 500 mg paracetamol, which is not commonly used), as only 3 of the 17 studies in this analysis used 500 mg paracetamol, and almost 90% of the data was from studies of 600 mg or more.

About half of participants needed additional analgesia over four to six hours, compared with about 70% with placebo. Significantly fewer participants required rescue medication with paracetamol than with placebo across all doses. There was no dose response. The numbers needed to treat to prevent one patient needing rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours were: 3.6 (3.0 to 6.0) for paracetamol 500 mg, 7.8 (5.2 to 15) for 600 to 650 mg, and 5.2 (4.3 to 6.7) for 975 to 1000 mg .

Longer duration of action is desirable in an analgesic, particularly in a postoperative setting where the patient may experience postoperative nausea, or be dependent on a third party to respond to a request for rescue medication. Duration of pain relief and requirement of rescue medication information have only recently been recognised as important outcomes (Moore 2005), and a fuller evaluation of the importance of these outcomes will depend on more data being collected from other, ongoing, systematic reviews.

Assessment of adverse events is limited in single dose studies as the size and duration of the trials permits only the simplest analysis, as has been emphasised previously (Edwards 1999). Combining results was potentially hampered by the different periods over which the data was collected. There was also and uncertainty about whether adverse event data continued to be collected after rescue medication had been taken. This could disproportionately inflate adverse events in the placebo groups, which tended to use more rescue medication. Most adverse events were reported as mild to moderate in intensity, and were most likely to be related to the anaesthetic or surgical procedure (e.g. nausea, vomiting and somnolence). Although the original review compares individual adverse events, we deemed there to be insufficient data in for this analysis to be valid.

We did calculate the NNH for any adverse event, and found no significant difference between paracetamol and placebo for numbers of participants experiencing any adverse event in the hours immediately following a single dose of the study medication. No serious adverse events were reported. Withdrawals due to adverse events occurred in both paracetamol and placebo treatment arms, but were uncommon, and too few for any statistical analysis. It is important to recognise that adverse event analysis after single dose oral administration will not reflect possible adverse events occurring with use of drugs for longer periods of time. In addition, the relatively small numbers of participants, even when all the trials were combined, and short duration of studies is insufficient to detect rare but serious adverse events, which typically occur with longer use, and at rates of much less than 1 in 1000 (Moore 2008b).

The sensitivity analysis did not demonstrate an effect of trial size or quality on relative benefit or NNT. It is noteworthy that there were only three trials (214 participants) of low quality so this analysis lacked sensitivity. The evidence base is overwhelmingly of good quality, and efficacy results are unlikely to be affected by these characteristics.

The main limitation is that these were single‐dose studies, and they could be criticised because pain relief, even in the acute setting, usually requires multiple dosing. That is true, but, in very general terms, pain is pain, and these single diose studies have been used for over 60 years to establish that a drug is actually an analgesic. The relative effectiveness of drugs and other interventions in this setting translates well to other settings like migraine, or musculoskeletal pain.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Paracetamol is effective for about half of patients with moderate to severe postoperative pain following various types of surgery, and has a low incidence of associated adverse effects.

Implications for research.

We now have a considerable body of evidence for the efficacy of paracetamol at doses between 600 and 1000 mg. It is unlikely that further studies will alter the estimates for the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours. More recent trials were generally of good quality, and efficacy data, where collected, was well reported. More consistent data on use of rescue medication, would provide better estimates of duration of analgesia, which in turn may help to decide which analgesics are most effective in the clinical setting. The quality of adverse event reporting remains problematical.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 9 October 2017 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2004 Review first published: Issue 1, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 April 2012 | Review declared as stable | The authors have checked the data on this topic and though there may be new studies, they are very unlikely to change the review's current conclusions. Therefore this review has been made 'stable' for at least five years. |

| 31 July 2008 | New search has been performed | New studies identified and included in analysis. All studies checked for additional data on use of rescue medication. |

| 31 July 2008 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Efficacy estimates only moderately changed |

| 30 November 2003 | New search has been performed | New studies found and included or excluded: 9/25/03 |

| 25 October 1999 | Amended | This review is an update of 'Single dose paracetamol (acetaminophen) with and without codeine for postoperative pain' published in 1998. The review was split into two reviews: paracetamol alone, and paracetamol plus codeine. The ID followed the first published review, paracetamol alone. |

Notes