Abstract

Background

Proponents of early intervention have argued that outcomes might be improved if more therapeutic efforts were focused on the early stages of schizophrenia or on people with prodromal symptoms. Early intervention in schizophrenia has two elements that are distinct from standard care: early detection, and phase-specific treatment (phase-specific treatment is a psychological, social or physical treatment developed, or modified, specifically for use with people at an early stage of the illness).

Early detection and phase-specific treatment may both be offered as supplements to standard care, or may be provided through a specialised early intervention team. Early intervention is now well established as a therapeutic approach in America, Europe and Australasia.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of: (a) early detection; (b) phase-specific treatments; and (c) specialised early intervention teams in the treatment of people with prodromal symptoms or first-episode psychosis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2009), inspected reference lists of all identified trials and reviews and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) designed to prevent progression to psychosis in people showing prodromal symptoms, or to improve outcome for people with first-episode psychosis. Eligible interventions, alone and in combination, included: early detection, phase-specific treatments, and care from specialised early intervention teams. We accepted cluster-randomised trials but excluded non-randomised trials.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably selected studies, quality rated them and extracted data. For dichotomous data, we estimated relative risks (RR), with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, we calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H) and used intention-to-treat analysis (ITT).

Main results

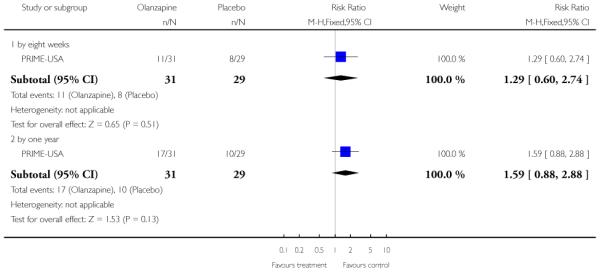

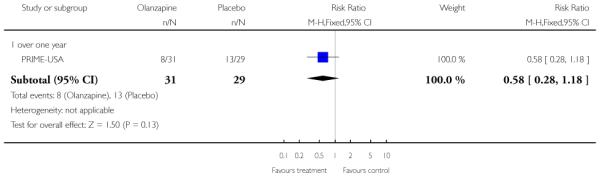

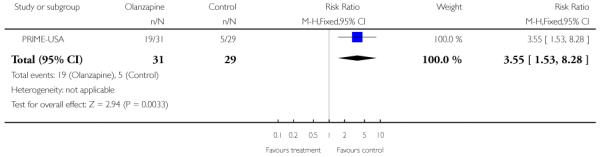

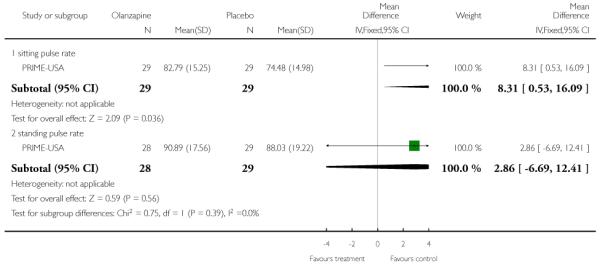

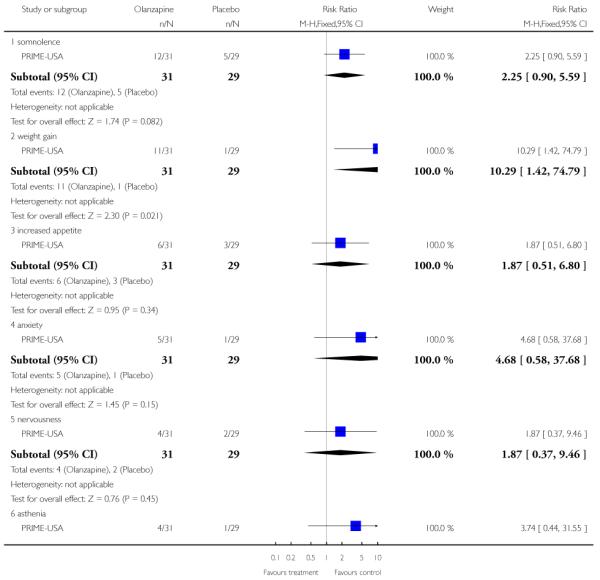

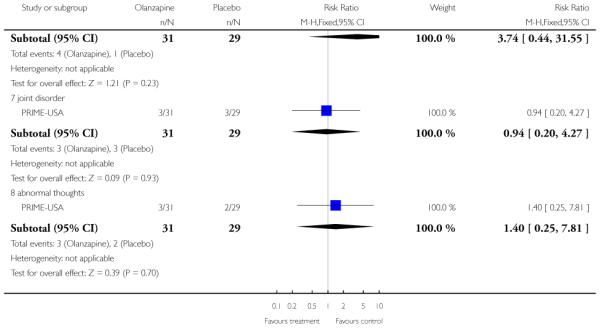

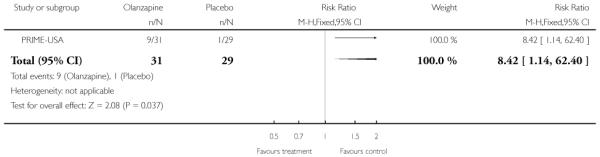

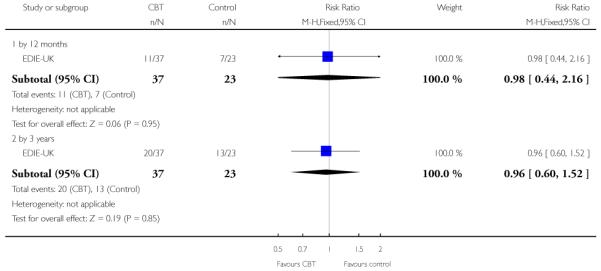

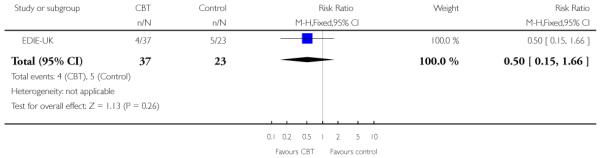

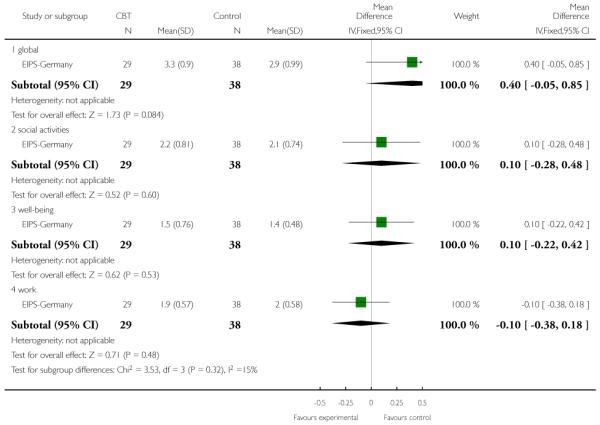

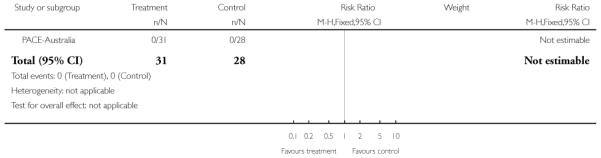

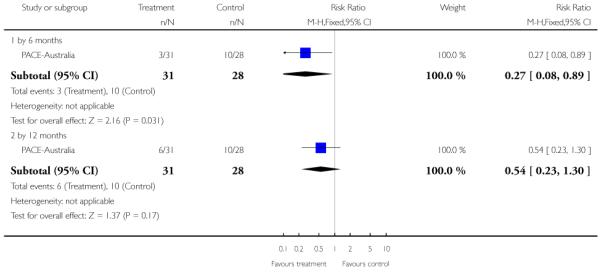

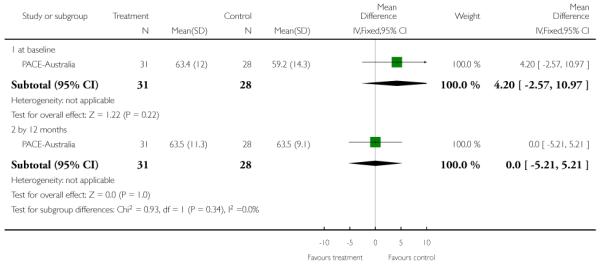

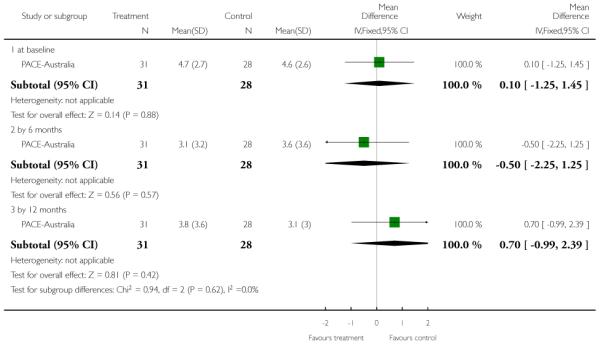

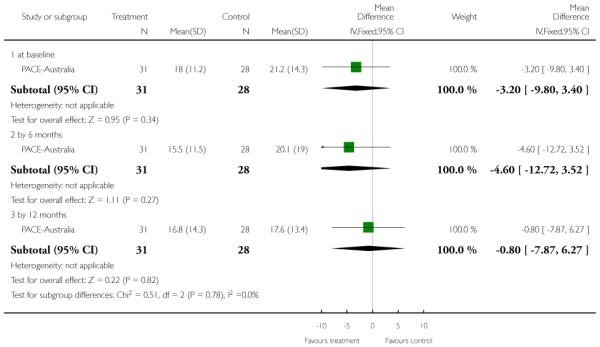

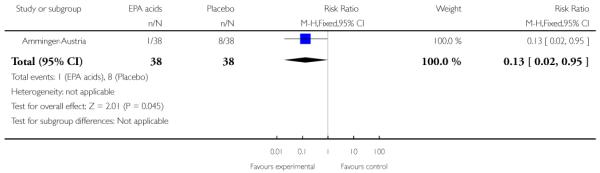

Studies were diverse, mostly small, undertaken by pioneering researchers and with many methodological limitations (18 RCTs, total n=1808). Mostly, meta-analyses were inappropriate. For the six studies addressing prevention of psychosis for people with prodromal symptoms, olanzapine seemed of little benefit (n=60, 1 RCT, RR conversion to psychosis 0.58 CI 0.3 to 1.2), and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) equally so (n=60, 1 RCT, RR conversion to psychosis 0.50 CI 0.2 to 1.7). A risperidone plus CBT plus specialised team did have benefit over specialist team alone at six months (n=59, 1 RCT, RR conversion to psychosis 0.27 CI 0.1 to 0.9, NNT 4 CI 2 to 20), but this was not seen by 12 months (n=59, 1 RCT, RR 0.54 CI 0.2 to 1.3). Omega 3 fatty acids (EPA) had advantage over placebo (n=76, 1 RCT, RR transition to psychosis 0.13 CI 0.02 to 1.0, NNT 6 CI 5 to 96). We know of no replications of this finding.

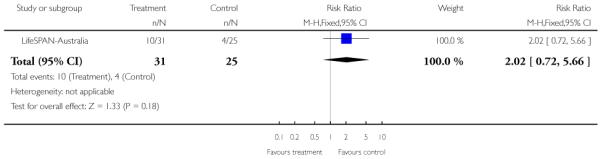

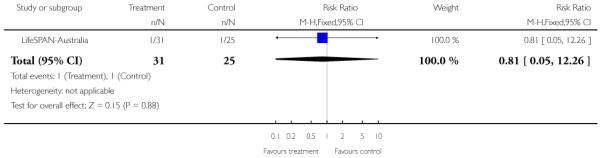

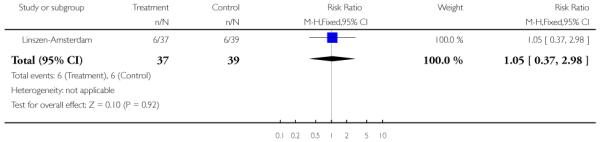

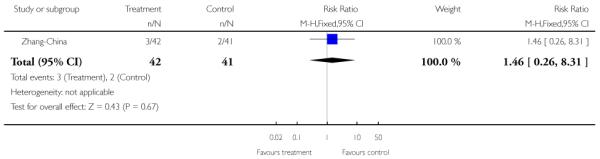

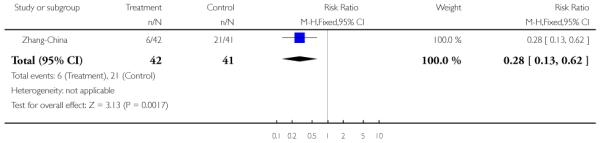

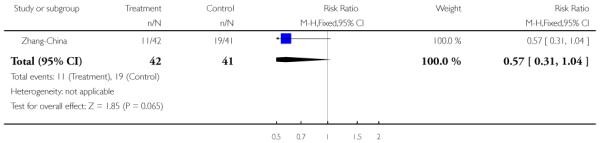

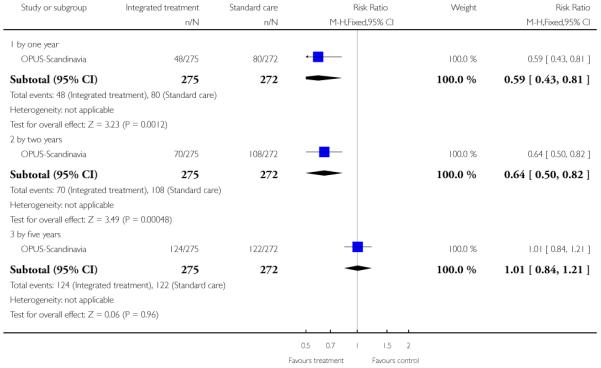

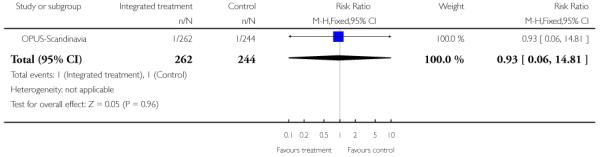

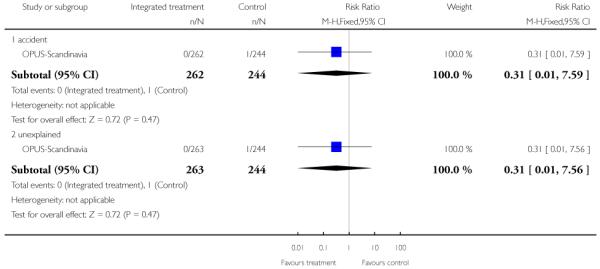

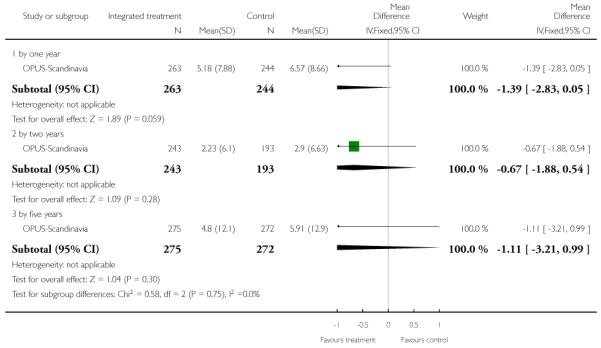

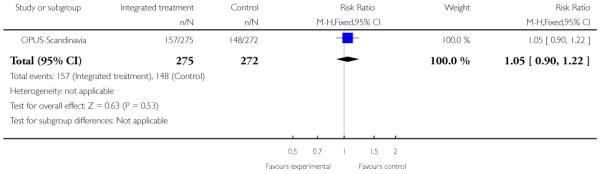

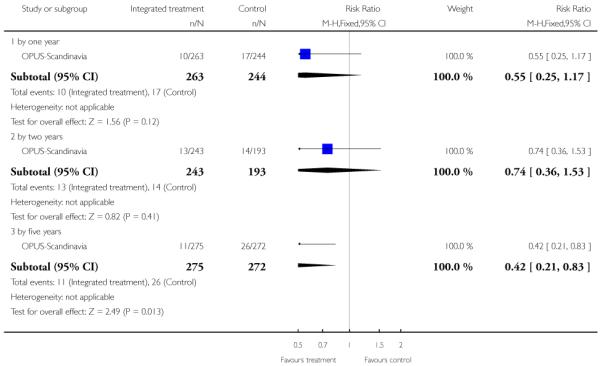

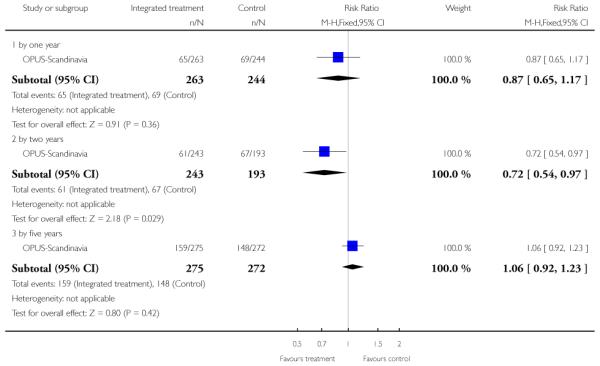

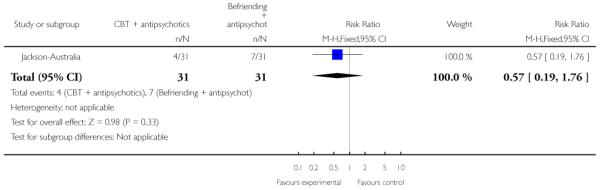

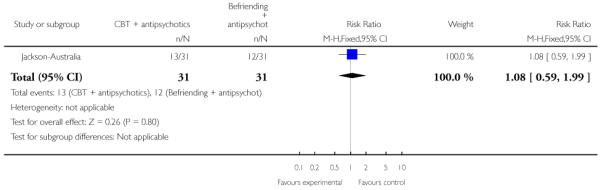

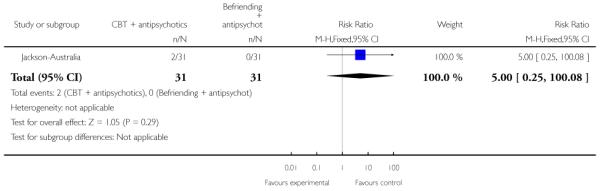

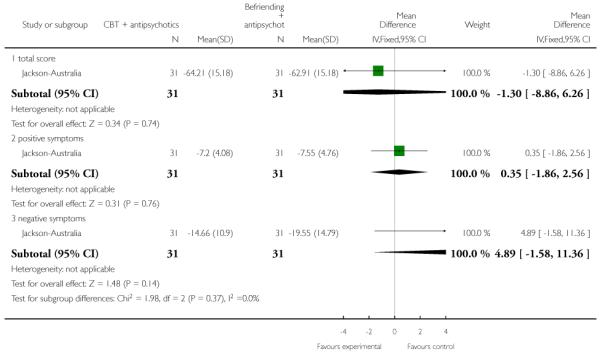

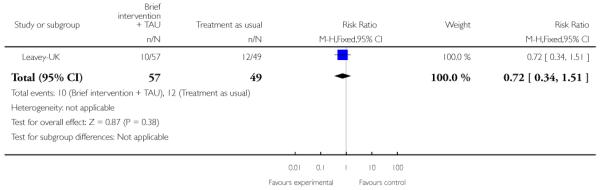

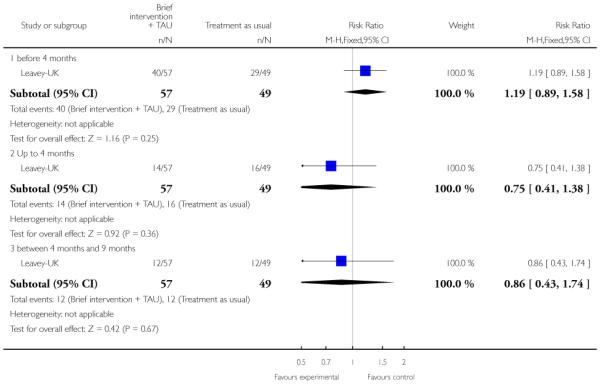

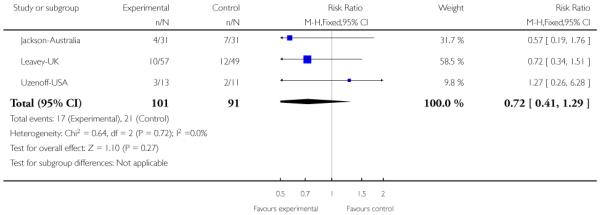

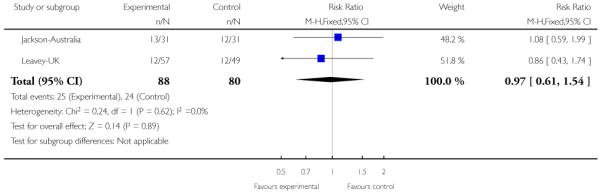

The remaining trials aimed to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis. Phase-specific CBT for suicidality seemed to have little effect, but the single study was small (n=56, 1 RCT, RR suicide 0.81 CI 0.05 to 12.26). Family therapy plus a specialised team in the Netherlands did not clearly affect relapse (n=76, RR 1.05 CI 0.4 to 3.0), but without the specialised team in China it may (n=83, 1 RCT, RR admitted to hospital 0.28 CI 0.1 to 0.6, NNT 3 CI 2 to 6). The largest and highest quality study compared specialised team with standard care. Leaving the study early was reduced (n=547, 1 RCT, RR 0.59 CI 0.4 to 0.8, NNT 9 CI 6 to 18) and compliance with treatment improved (n=507, RR stopped treatment 0.20 CI 0.1 to 0.4, NNT 9 CI 8 to 12). The mean number of days spent in hospital at one year were not significantly different (n=507, WMD, −1.39 CI −2.8 to 0.1), neither were data for ‘Not hospitalised’ by five years (n=547, RR 1.05 CI 0.90 to 1.2). There were no significant differences in numbers ‘not living independently’ by one year (n=507, RR 0.55 CI 0.3 to 1.2). At five years significantly fewer participants in the treatment group were ‘not living independently’ (n=547, RR 0.42 CI 0.21 to 0.8, NNT 19 CI 14 to 62). When phase-specific treatment (CBT) was compared with befriending no significant differences emerged in the number of participants being hospitalised over the 12 months (n=62, 1 RCT, RR 1.08 CI 0.59 to 1.99).

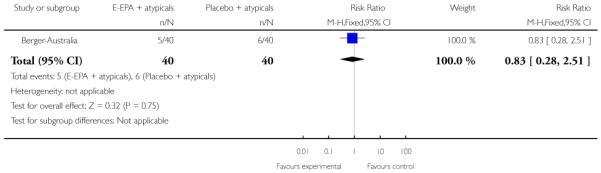

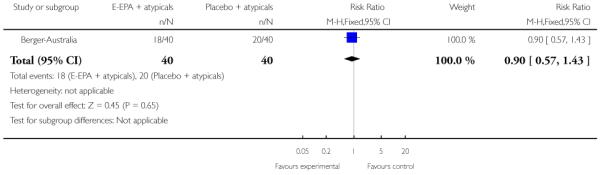

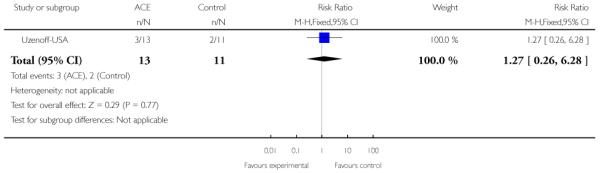

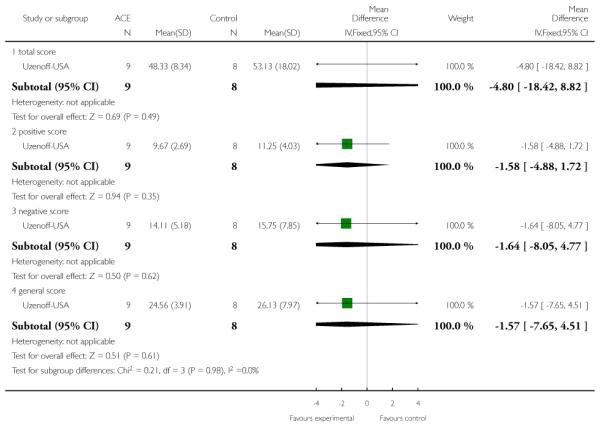

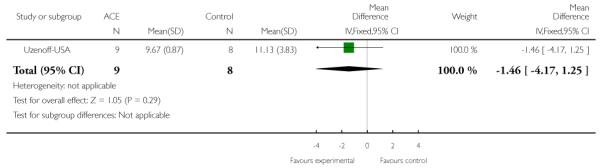

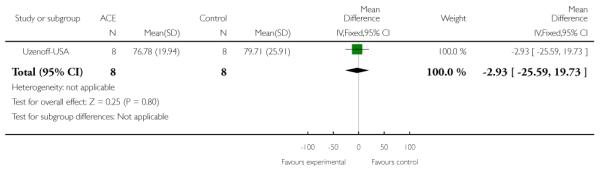

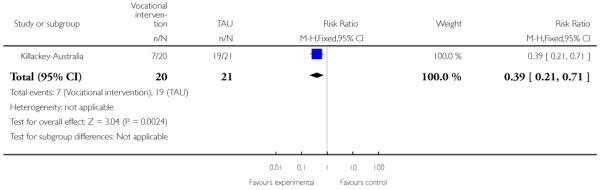

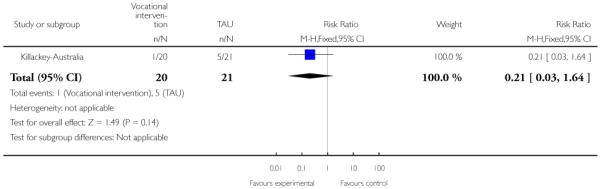

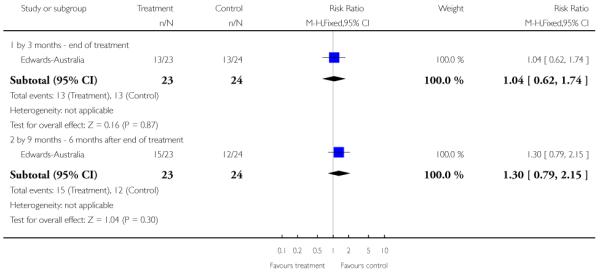

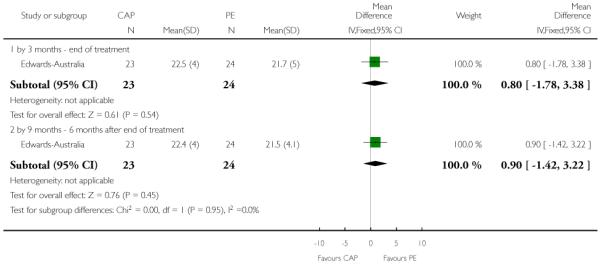

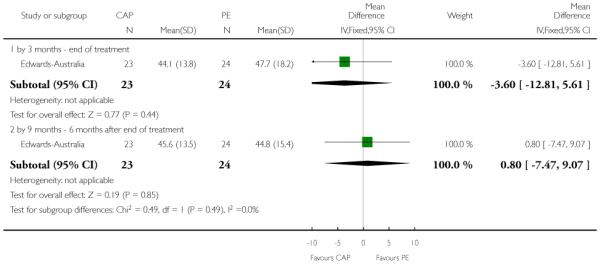

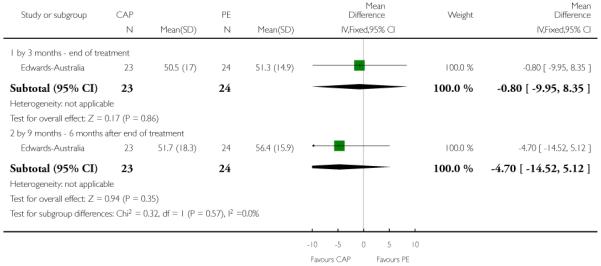

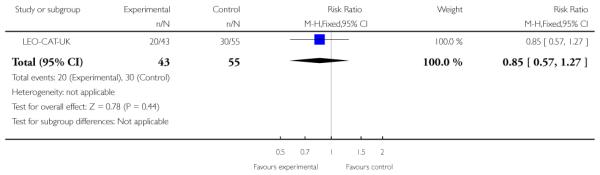

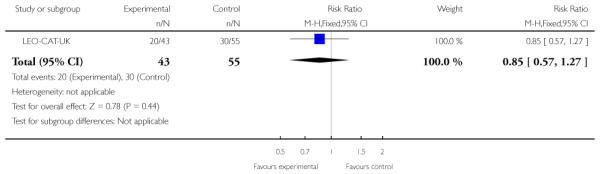

Phase-specific treatment E-EPA oils suggested no benefit (n=80, 1 RCT, RR no response 0.90 CI 0.6 to 1.4) as did phase-specific treatment brief intervention (n=106, 1 RCT, RR admission 0.86 CI 0.4 to 1.7). Phase-specific ACE found no benefit but participants given vocational intervention were more likely to be employed (n=41, 1 RCT, RR 0.39 CI 0.21 to 0.7, NNT 2 CI 2 to 4). Phase-specific cannabis and psychosis therapy did not show benefit (n=47, RR cannabis use 1.30 CI 0.8 to 2.2) and crisis assessment did not reduce hospitalisation (n=98, RR 0.85 CI 0.6 to 1.3). Weight was unaffected by early behavioural intervention.

Authors’ conclusions

There is emerging, but as yet inconclusive evidence, to suggest that people in the prodrome of psychosis can be helped by some interventions. There is some support for specialised early intervention services, but further trials would be desirable, and there is a question of whether gains are maintained. There is some support for phase-specific treatment focused on employment and family therapy, but again, this needs replicating with larger and longer trials.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Psychotic Disorders [diagnosis; therapy], *Schizophrenia [diagnosis; therapy], Cognitive Therapy, Early Diagnosis, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Suicidal Ideation, Time Factors

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

Schizophrenia and other functional psychoses cause enormous suffering for individuals and their families, and are a financial burden to the NHS and other health services. The estimated total cost of schizophrenia in England was £6.7 billion in 2004/05; the direct cost of treatment and care was £2 billion, whilst the indirect cost to society was £4.7 billion, and the cost of informal care and private expenditure was £615 million (Mangalore 2007). Despite new medications and the development of community care, about one-third of people with schizophrenia have a poor long-term outcome (Mason 1997). An overview of studies investigating outcomes has shown that people with schizophrenia have a one-year relapse rate of 15% to 35%, rising to 80% within five years (Larsen 1998). Achievement of full remission becomes less likely after each relapse, and about 10% of sufferers eventually commit suicide (Wiersma 1998).

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a chronic, relapsing mental illness and has a worldwide lifetime prevalence of about 1% irrespective of culture, social class and race. Schizophrenia is characterised by positive symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions and jumbled thinking; and negative symptoms such as apathy, poverty of speech, and withdrawal from social activities.

Description of the intervention

Early intervention in psychosis has two elements that are distinct from standard care: early detection and phase-specific treatment. Early detection may be defined as either the identification of people thought likely to develop psychosis (i.e. those who display prodromal symptoms, but have never been psychotic (Schaffner 2001)) or the identification of people who are already psychotic, but have not yet received adequate treatment (Wyatt 2001).

Phase-specific treatments are defined as treatments (psychological, social or physical) that are especially targeted at people in the prodrome or early stages of schizophrenia (Miller 1999). Phase-specific treatments may be directed at preventing progression to psychosis (in people with prodromal symptoms), or at promoting recovery (in people who have recently experienced their first episode of psychosis).

Early detection and phase-specific treatments may be provided as supplements to standard psychiatric care, or they may be provided by means of a specialised early intervention team (Garety 2000). Such teams provide care exclusively to people who have prodromal symptoms or are in early stages of schizophrenia (Edwards 2000). Prodromal patients are usually assessed by the attenuated psychotic symptom criteria, using either the criteria by Yung 2005 or the Scale of Psychotic Symptoms (SOPS, Miller 1999). A second method, is the detection of ‘basic symptoms’ developed in Germany (Schultze-Lutter 2007). When people are referred to as ‘ultra high risk’ they are using the Yung 2005 criteria. When they are referred to as early or late initial prodrome state, they are using basic symptoms.

How the intervention might work

Until recently, the orthodox approach to treating schizophrenia was to concentrate therapeutic resources on those people who developed severe and chronic disabilities (McGorry 1999). This approach has been challenged by proponents of early intervention, who have argued that greater investment of resources in the early stages of the disorder might substantially reduce the numbers of people developing chronic disabilities (Wyatt 1991). This argument has been strengthened by the observation that there may be an association between various outcome parameters and the duration of untreated psychosis (the time from the development of the first psychotic symptom to the receipt of adequate drug treatment) (Norman 2001). This has led to the proposition that untreated psychosis may be ‘toxic’ and that early intervention might prevent irreversible harm (Sheitman 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

The arguments in favour of early intervention have been so persuasive that early intervention teams are well-established in America, Europe and Australasia (Edwards 2002). In 2000, the UK government announced its intention to set up 50 early intervention teams in England to provide specialised care to all young people with a first episode of psychosis (DoH 2000). It remains unclear, however, how far these service developments are underpinned by evidence of effectiveness. There is particular concern over the ethics of early intervention with prodromal patients, when the benefits of early detection and treatment are unclear, and there is no certainty that they will go on to develop psychosis (Rosen 2000).

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the effects of early intervention in the treatment of early psychosis.

The two specific objectives were to determine the following.

1. The effects of early detection and treatment of people with ‘prodromal’ symptoms, in terms of:

1.1 prevention of progression to full-blown psychosis;

1.2 clinical and social outcomes;

1.3 process variables and costs.

2. To determine the effects of early detection and treatment of people in their first episode of psychosis, in terms of:

2.1 clinical and social outcomes;

2.2 prevention of relapse;

2.3 process variables and costs;

2.4 reduction in duration of untreated psychosis.

We defined ‘Treatment’ as including both phase-specific treatments and care from a specialised early intervention team. We are not concerned with evaluating the accuracy of methods of predicting who is likely to develop psychosis.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We accepted cluster-randomised trials and listed non-randomised trials in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In broad terms we have included two types of trial in this review.

1. Trials to prevent the development of psychosis

These studies involved treatments and/or methods of management that are given to people who are believed to be showing prodromal (pre-psychotic) symptoms and are therefore considered at high risk of developing psychosis. The primary aim of such studies was to prevent progression to psychosis, and invariably the interventions they offered were combined with some method of early detection of people at risk.

2. Trials to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis

These studies involved treatments and/or methods of management designed for people in the early stages of psychosis. The primary aim of such studies was to improve the long term outcome. Early detection might be offered in addition to the treatments, with the aim of ensuring that the treatment was offered as early as possible after the onset of psychosis.

Types of participants

1. For trials to prevent the development of psychosis, we included people who were judged by the trialists to be in a prodromal phase of psychosis, on the basis of showing prodromal symptoms (however defined).

2. For trials to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis, we included people who were in their first episode of psychosis, or were in the process of recovering from their first episode. People with psychosis were defined as those presenting with any combination of delusions, hallucinations or thought disorder, or those who had been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like disorder, bipolar disorder (manic episode i.e. with psychotic symptoms), or depression with psychotic features.

We excluded trials where the majority of participants were suffering from a learning disability or an organic psychosis. We did not exclude anyone for reasons such as age or type of psychosis (for example, affective psychosis). Where studies included both first and second episode participants, we excluded trials if more than 10% of the participants included in the study had experienced a second episode,

Types of interventions

In trials of early intervention there are many possible combinations of intervention and control condition. This depends on: the type of participant (prodromal or first episode); whether the trial involved early detection (which could involve the whole sample or just the treatment group); the type of intervention (phase-specific or specialised team); the nature of any phase-specific treatment (cognitive therapy, family therapy etc); and the type of control (no treatment, standard psychiatric care, care from a specialised team but not phase specific intervention, etc.). In this section the most likely combinations of intervention and control conditions are listed for trials to prevent the development of psychosis and trials to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis.

1. Trials to prevent the development of psychosis in prodromal patients

These trials require prodromal patients, and since such patients do not normally present to psychiatric services, the trials therefore require some form of early detection to be applied to the whole sample. The intervention may consist of: phase-specific treatment (medication, psychological treatment or other) or care from a specialised team (which might offer phase-specific treatments). The control condition may consist of no treatment, or standard psychiatric care, or care from a specialised team (in which case the intervention will consist of care from a specialised team plus a phase specific intervention). The various types of intervention and control condition are described in more detail below.

1.1 Phase-specific treatment

In the context of preventing psychosis, phase-specific treatments are discrete interventions including medication regimes, which have been specifically developed for use in patients experiencing prodromal symptoms. A phase-specific treatment could be offered by an individual therapist or provided in the context of receiving care from a specialised team (see 1.2 below). More than one phase-specific treatment might be offered at the same time (for example, medication regime and cognitive therapy).

1.2 Care from a specialised team

In the context of preventing psychosis, this is defined as a multi-disciplinary psychiatric team, specialising in the treatment of patients with prodromal symptoms. Such a team would normally provide comprehensive psychiatric care to its patients and would be an alternative, rather than an addition, to standard psychiatric care. In the context of a trial it is likely that any specialised team would also offer phase-specific interventions.

1.3 Control conditions

In the context of preventing psychosis, the common control conditions are: no treatment; non-specific supportive therapy or care from a specialised team (which did not offer phase-specific treatments to prevent onset of psychosis).

2. Trials to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis

The intervention may consist of: early detection; phase-specific treatments (medication, psychological intervention or other) or care from a specialised team (which might offer phase-specific treatments). The control condition may consist of standard psychiatric care or care from a specialised team (in which case the intervention will consist of care from a specialised team plus a phase-specific intervention). A ‘no treatment’ control group is not an ethically acceptable option in first-episode psychosis trials. The various types of intervention and control condition are described in more detail below.

2.1 Early detection

In trials to improve outcome in first-episode psychosis it is possible to use early detection as an intervention applied to the treatment group alone; this is in contrast to the situation in trials designed to prevent psychosis (see 1. above) where early detection must be applied to both treatment and control groups. The theoretical basis for using early detection as an intervention is that shortening the duration of untreated psychosis in itself improves outcome. In trials where early detection is the intervention being tested, the unit of randomisation must be a cluster (for example, general practices or catchment areas), since it is not possible to individually randomise patients who have not yet been diagnosed.

2.2 Phase-specific treatment

In the context of improving outcome in the first episode, phase-specific treatments are discrete treatments and include medication regimes which have been specifically developed for use in the early stages of psychosis. A phase-specific treatment can be offered by an individual therapist or provided in the context of receiving care from a specialised team (see 2.3 below). More than one phase-specific treatment might be offered at the same time (for example, medication regime and cognitive therapy).

2.3 Care from a specialised team

In the context of improving outcome in first episode, this is defined as a multi-disciplinary psychiatric team, specialising in the treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis. Such a team would normally provide comprehensive psychiatric care to its patients and is an alternative, rather than an addition, to standard psychiatric care. In the context of a trial, it is likely that any specialised team would also offer phase-specific interventions.

2.4 Control conditions

In the context of improving outcome in first episode, the common control conditions are standard care, or care from a specialised team (which does not offer the phase-specific treatment being provided in the treatment arm of the trial). Standard care would be the normal service for people with severe psychiatric illness in the region where the trial took place, and would normally consist of out-patient follow up, medication, and support form a community mental health team, but would not involve any phase-specific treatment or specialised team.

3. Excluded interventions

We considered treatment with low doses of neuroleptic medication (atypical or standard) a phase-specific treatment if given to prevent progression to psychosis, or in the context of a medication protocol designed specifically for treating patients in their first episode of psychosis. However, simple comparisons of atypical neuroleptic medication versus standard neuroleptics in first-episode patients were beyond the scope of this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

For trials to prevent the development of psychosis (i.e. prodromal participants) the primary outcomes were as follows.

1. General

1.1 Converting to psychosis during follow-up period

For trials to improve the outcome of first-episode psychosis the outcomes were as follows.

1. General

1.1 Relapse - as defined by each study or re-admission during follow-up

Secondary outcomes

For trials to prevent the development of psychosis (i.e. prodromal participants) the secondary outcomes were as follows.

1. General

1.1 Overall functioning

1.2 Duration of hospital stay

1.3 Loss to follow up

1.4 Satisfaction with treatment - participant/carer

1.5 Remaining in contact

2. Mental state

2.1 General symptoms

2.2 Specific symptoms

2.2.1 Positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking)

2.2.2 Negative symptoms (avolition, poor self-care, blunted affect)

2.2.3 Mood - depression

3. Behaviour

3.1 General behaviour

3.2 Specific behaviours (for example, aggressive or violent behaviour)

3.2.1 Social functioning

3.2.2 Employment status during trial (employed/unemployed)

3.2.3 Occurrence of violent incidents (to self, others or property)

4. Adverse effects

4.1 General

4.2 Specific

4.2.1 Death (suicide and non-suicide)

4.2.2 Movement disorders (extrapyramidal side effects, specifically tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome)

4.2.3 Sedation

4.2.4 Dry mouth

4.2.5 Weight gain

5. Economic

5.1 Cost of care

6. Quality of life

6.1 No substantial improvement in quality of life

For trials to improve the outcome of first-episode psychosis the secondary outcomes were:

1. General

1.1 Overall functioning

1.2 Hospital readmission

1.3 Duration of hospital stay

1.4 Loss to follow-up

1.5 Satisfaction with treatment - participant/carer

1.6 Remaining in contact with services

2. Mental state

2.1 General symptoms

2.2 Specific symptoms

2.2.1 Positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking)

2.2.2 Negative symptoms (avolition, poor self-care, blunted affect)

2.2.3 Mood - depression

3. Behaviour

3.1 General behaviour

3.2 Specific behaviours (for example, aggressive or violent behaviour)

3.2.1 Social functioning

3.2.2 Employment status during trial (employed/unemployed)

3.2.3 Occurrence of violent incidents (to self, others or property)

4. Adverse effects

4.1 General

4.2 Specific

4.2.1 Death (suicide and non-suicide)

4.2.2 Movement disorders (extrapyramidal side-effects, specifically tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome)

4.2.3 Sedation

4.2.4 Dry mouth

4.2.5 Weight gain

5. Economic

5.1 Cost of care

Search methods for identification of studies

We applied no language restrictions within the limitations of the search.

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2009)

The register was searched using the phrase:

[early* in title, abstract or keywords of REFERENCE] or [Early* in intervention or prodromal* or early*’ in Health Care Condition of STUDY]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Previous searches for earlier versions of this review

Please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference lists

We inspected reference lists of all identified trials and reviews for additional trials.

2. Personal contact

We contacted experts in the field within the European First Episode Network (2003) to identify unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We (MM and AL) searched The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s register. Working independently we examined the papers identified from the search strategy. We discarded obviously irrelevant publications and retained only those in which some form of early intervention had been compared against a control treatment, and obtained copies of papers relating to relevant trials. Once we had obtained these papers, we decided whether the trials were eligible. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. For the 2006 update we (MM and JR) independently inspected citations. Where disagreement occurred, we sought to resolve this by discussion, or where doubt remained, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once we had obtained the full articles, we independently decided whether they met the review criteria. We resolved any disagreements that occurred by discussion, and when this was not possible we added trials to the list of those awaiting assessment until we acquired further information. For the 2009 update we (MM and JR) inspected all study citations identified by the searches, and obtained full reports of the studies of agreed relevance.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

We (MM, AL) independently extracted and entered trial data into Review Manager (RevMan) twice, cross-checking for consistency (RevMan 2008). An initial analysis included all trials meeting inclusion criteria, whilst a second sensitivity analysis excluded all but the highest quality trials (Category A and B). For the 2006 and 2010 update, we (MM and JR) independently extracted and entered data into RevMan, cross-checking again for consistency. Where disputes arose, we attempted to resolve these by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was needed to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter the data, and added this outcome of the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted the data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the ‘line of no effect’ indicates a ‘favourable’ outcome for early intervention. Where this was not possible, (for example, scales that calculate higher scores=improvement) we inserted a minus sign into the data tables to reverse the graphical display in RevMan analyses so that the direction of effect was clear.

2.3 Scale-derived data

Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore we only included continuous data from rating scales were if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer-reviewed journal.

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on outcomes in trials relevant to mental health issues are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non-parametric data we applied the following standards to continuous final value endpoint data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale started from zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, should be less than the mean (otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution - Altman 1996); in cases with data that are greater than the mean we entered them into the ‘Other data’ table as skewed data. Where the skewed data are derived from a trial with ≧ 200 participants, the skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and were entered into syntheses.

If a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS, which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skewness is present if 2SD>(S-Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. We reported non-normally distributed data (skewed) in the ‘other data types’ tables. For change data (mean change from baseline on a rating scale) it is impossible to tell whether data are non-normally distributed (skewed) or not, unless individual patient data are available. After consulting the ALLSTAT electronic statistics mailing list, we entered change data in RevMan analyses and reported the finding in the text to summarise available information. In doing this, we assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analysis could cope with the unknown degree of skew.

2.5 Final endpoint value versus change data

Where both final endpoint data and change data were available for the same outcome category, only final endpoint data were presented. We acknowledge that by doing this much of the published change data may be excluded, but argue that endpoint data is more clinically relevant and that if change data were to be presented along with endpoint data, it would be given undeserved equal prominence. Where studies reported only change data we contacted authors for endpoint figures.

2.6 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables (such as days in hospital) that could be reported in different metrics (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (for example, mean days per month).

2.7 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This could be done by identifying cut-off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into ‘clinically improved’ or ‘not clinically improved’. It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale-derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut-off presented by the original authors.

2.8 Summary of findings table

For the 2011 version of the review we had available to us the possibility of producing Summary of Findings tables. These should be considered before being biased by the results of analyses, but for us this is impossible. We have chosen to present two - but this choice is post hoc. We chose to present data from PACE-Australia and OPUS-Scandinavia as these are benchmark trials in this area and outcomes from these trials that we think to be clinically important.

Progression to psychosis

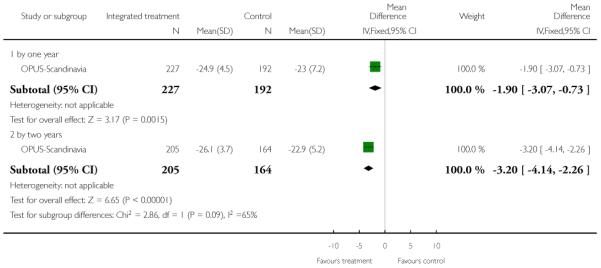

Compliance with treatment - treatment stopped in spite of need

Leaving the study early

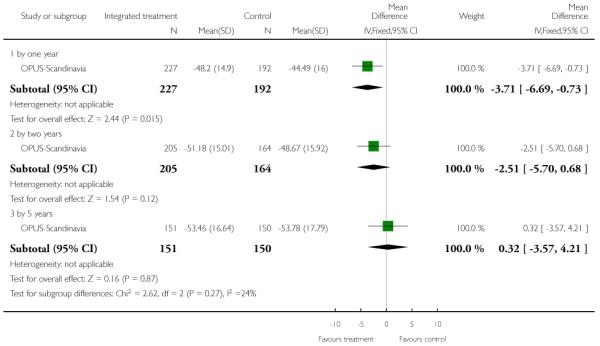

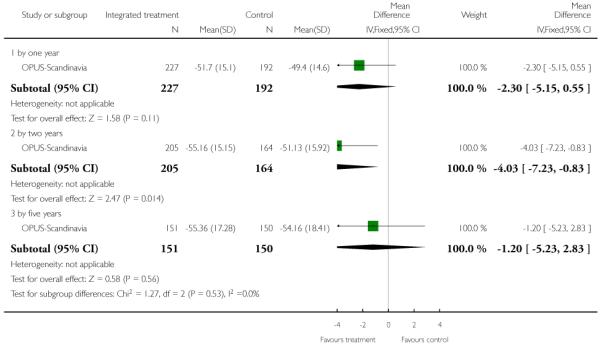

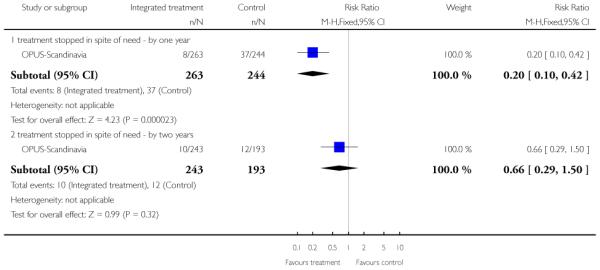

Service use: 1. Average mean number of days per month in hospital

Service use: 2. Not hospitalised

Social outcomes: 1. Not living independently

Social outcomes: 2. Not working or in education

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, we assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We would not have included studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias or where allocation was clearly not concealed.

The categories are defined below.

- YES - low risk of bias

- NO - high risk of bias

- UNCLEAR - uncertain risk of bias

If disputes arose as to which category we should allocate a trial, again, we achieved resolution by discussion, after working with a third reviewer.

Earlier versions of this review used a different, less well-developed, means of categorising risk of bias (see Appendix 2).

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated an estimate of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% (fixed-effect) confidence intervals (CI). RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) using Visual Rx.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference SMD). However, had scales of very considerable similarity been used, we would have presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we would have calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ cluster randomisation (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data pose problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra-class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a unit-of-analysis error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes Type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra-class correlation co-efficients (ICCs) of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non-cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a design effect. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (M) and the ICC (Design effect=1+ (M −1)*ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported we assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, we synthesised these with other studies using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross-over design

A major concern of cross-over trials is the carry-over effect. It occurs if an effect (for example, pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state, despite a wash-out phase. For the same reason cross-over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data of the first phase of cross-over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

We presented studies involving more than two treatment arms, if relevant, in comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss to follow-up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). We are forced to make a judgment where this is for the trials likely to be included in this review. Should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for by eight weeks, we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses.

2. Intention to treat analysis

2.1 Binary data

We excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow-up (this did not include the outcome of ‘leaving the study early’). In studies with less than 50% dropout rate, people leaving early were considered to have had the negative outcome, For example, those lost to follow-up for the outcome of relapse were treated in the analysis as having relapsed. Suicide was treated as relapse.

2.2 Continuous data

2.2.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome is between 0% and 50% and completer-only data were reported, we have reproduced these.

2.2.2 Standard deviations

We first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data but an exact standard error and confidence interval were available for group means, and either P value or T value were available for differences in mean, we noted these, and in future versions will calculate them according to the rules described in the Handbook (Higgins 2008): When only the standard error (SE) is reported, standard deviations (SDs) can be calculated by the formula SD=SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Handbook (Higgins 2008) present detailed formula for estimating SDs from P values, T or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formula do not apply, we, in the future will calculate SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Some of these imputation strategies can introduce error. The alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We will examine the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

2.2.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results. Therefore, where LOCF data have been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we reproduced these data and indicated that they are the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying situations or people which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we would have fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. Should such methodological outliers arise we would have fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). We interpreted I2 estimate greater than or equal to 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 - Higgins 2008). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Handbook (Higgins 2006). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small-study effects (Egger 1997). We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible we employed a fixed-effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed-effect or random-effects models. The random-effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us; however, random-effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies - those trials that are most vulnerable to bias. For this reason we favour using the fixed-effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We did not anticipate subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we have reported this. First we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data had been correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed studies outside of the company of the rest to see if homogeneity was restored. Should this occur with no more than 10% of the data being excluded, we have presented data. If not, we have not pooled data and have discussed relevant issues.

Should unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity be obvious we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

For the 2011 version of this review we did not anticipate undertaking any additional sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

For substantive descriptions of studies, please see Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

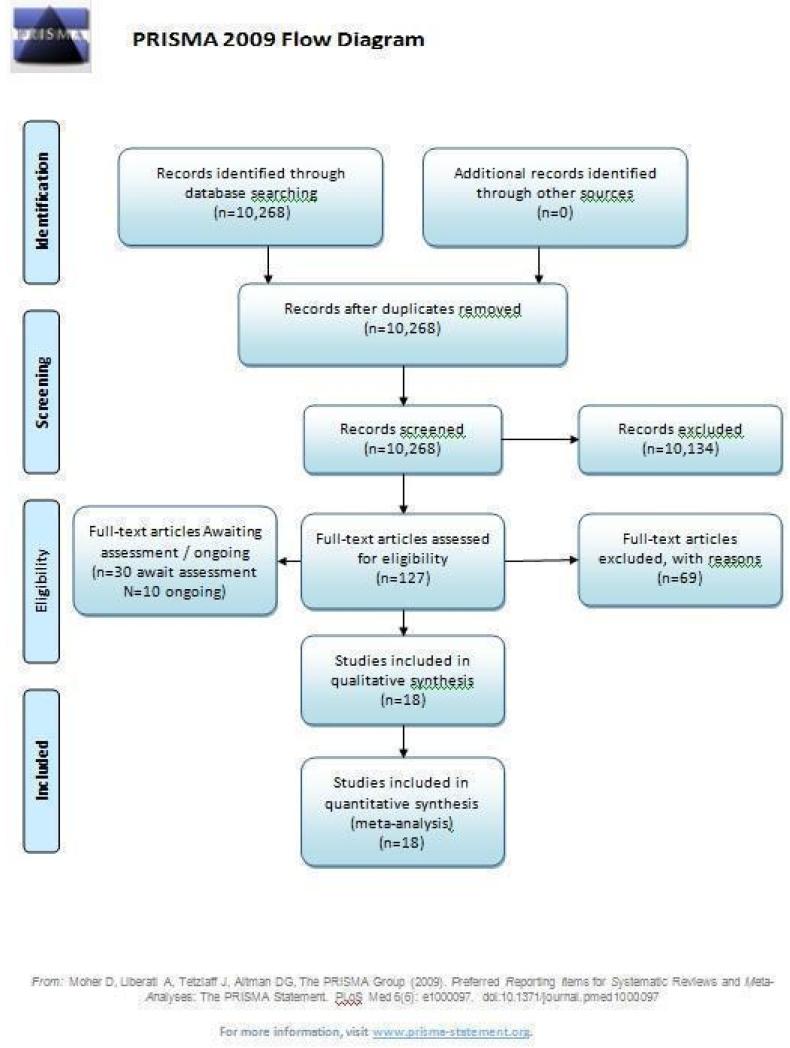

The original search strategy identified 9279 abstracts, of which 184 referred to potentially eligible studies and 155 reviews of early intervention (Figure 1). From these we identified 100 relevant studies, of which 43 did not meet inclusion criteria. We were able to include three studies and the remainder are awaiting classification. For substantive descriptions of studies, please see the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram

For the 2006 update search we identified 159 new citations and were able to include four additional studies.

During the 2009 update search we identified 830 references (from 420 studies) and were able to include 11 additional studies (Alvarez-Spain; Amminger-Austria; Berger-Australia; Edwards-Australia; EIPS-Germany; Jackson-Australia; Killackey-Australia; Leavey-UK; LEO-CAT-UK; LIPS-Germany; Uzenoff-USA).

Included studies

We included 18 studies with 1808 participants.

1. Methods

For description of methods - please see Risk of bias in included studies.

2. Participants and setting

2.1 Participants with prodromal symptoms - and setting

Six trials (Amminger-Austria, EIPS-Germany, EDIE-UK, LIPS-Germany, PACE-Australia, PRIME-USA) were concerned with preventing the onset of psychosis.

EIPS-Germany undertook the research in community settings in Cologne, Bonn, Dusseldorf, and Munich. The participants had a mean age of 26 years and were judged at risk of psychosis because they met the criteria for the Early Initial Prodrome State according to the presence of Basic Symptoms. The LIPS-Germany study was undertaken in the same settings as EIPS-Germany, but included late prodrome participants who were at risk of psychosis according to the Basic Symptom criteria for Late Initial Prodrome State (where conversion to psychosis is considered more imminent than in the Early Initial Prodrome State). Participants had a mean age of 25 years. EDIE-UK recruited participants from primary care teams (general practitioners, practice nurses and psychological therapists), student counselling services, accident and emergency departments, specialist services (community drug and alcohol teams, child and adolescent psychiatry and adult psychiatry services) and voluntary sector agencies. Participants had a mean age of 21 years and were judged to have an ‘ultra high risk’ of developing a first episode of psychosis (Yung’s Criteria Yung 2005).PACE-Australia recruited participants referred to the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation clinic, which is part of the EPPIC programme. Participants were from 14 to 30 years of age, and met Yung criteria for an ‘ultra high risk’ mental state (see included studies table for details). PRIME-USA recruited people from referrals and by participants responding to study advertisements. Participants were aged from 12 to 36 years with a diagnosis of being at risk of developing psychosis according to SOPS criteria (similar to Yung’s criteria for the ‘ultra high risk’ mental state). Participants were recruited at four sites (three in the USA and one in Canada). Amminger-Austria recruited outpatients at the Vienna General Hospital who were at risk of developing first-episode psychosis according to Yung’s criteria for the ‘ultra high risk’ mental state. Participants were eligible if they were aged from 13-24 years; the mean age of the participants was 16.4 years.

2.2 Participants with first-episode psychosis and setting

Twelve trials were concerned with improving outcome in first-episode psychosis (Alvarez-Spain; Berger-Australia; Edwards-Australia; Jackson-Australia; Killackey-Australia; Leavey-UK; LEO-CAT-UK; LifeSPAN-Australia; Linszen-Amsterdam; OPUS-Scandinavia; Uzenoff-USA; Zhang-China).

Alvarez-Spain included drug naïve participants with a DSM-IV diagnosis of psychosis, and a mean age of 26 years; the trial was set in the community. Edwards-Australia included participants with first-episode psychosis diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder using DSM-IV criteria. The study was undertaken at the EPPIC centre in Melbourne, Australia. Berger-Australia recruited participants in Melbourne, Australia (EPPIC Centre); participants had an average age of 20 years, and a mean antipsychotic treatment exposure prior to study of 17.5 days. Jackson-Australia included people with a mean onset of psychosis at 22 years; the settings used were at the participant’s home, a neutral location or the EPPIC centre. Leavey-UK included first-episode psychosis patients who had been diagnosed within the last six months and were recruited from psychiatric services in North London. LEO-CAT-UK included participants with first-episode psychosis (Yung’s criteria) with a mean age of 23 years. The study was undertaken in community settings within the borough of Lambeth, London, UK. LifeSPAN-Australia recruited participants from the Western region of Melbourne, Australia and is part of the EPPIC programme, which includes an early detection and crisis assessment team. Participants were aged 15 to 29 years, and were acutely suicidal. Linszen-Amsterdam recruited participants aged from 15 to 26 who were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia and living in close contact with parents or relatives. All participants were recruited from an adolescent clinic and had to agree to an initial three months’ inpatient programme before randomisation. Subsequent treatment took place on an outpatient basis. OPUS-Scandinavia recruited first-episode psychosis (ICD 10) patients from inpatient and outpatient departments in Denmark; participants were aged 18 to 45. Zhang-China recruited only men who had just been discharged from Suhoz Psychiatric Hospital in China, following their first admission for schizophrenia. The intervention and standard care were provided on an outpatient basis. Killackey-Australia enrolled participants from the EPPIC programme with first-episodepsychosis; participants had a mean age of 21 years. Uzenoff-USA recruited participants with first episode schizophrenia in the USA.

3. Study size

OPUS-Scandinavia was the largest study, and had a sample size (n=547) which was arrived at using a pre-study power calculation. The other trials were small and, in ascending order of size, were:Uzenoff-USA (24), Killackey-Australia (41), Edwards-Australia (47), LifeSPAN-Australia (56), PACE-Australia (59), EDIE-UK (60), PRIME-USA (60), Alvarez-Spain (61), Jackson-Australia (62), Linszen-Amsterdam (76), Berger-Australia (80), Amminger-Austria (81), Zhang-China (83), Leavey-UK (106), LEO-CATUK (113), LIPS-Germany (124) and EIPS-Germany (128).

4. Intervention

4.1 Trials to prevent the onset of psychosis

Six trials (Amminger-Austria; EIPS-Germany; LIPS-Germany; EDIE-UK; PACE-Australia; PRIME-USA) were concerned with preventing the onset of psychosis.

Amminger-Austria compared omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) with placebo over three months in adolescents at risk of first-episode psychosis according to the criteria of Yung 2005.

EIPS-Germany employed a complex intervention consisting of 12 months of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) delivered in group and individual therapy sessions, supplemented by cognitive remediation therapy. The participants were at risk of developing first episode of psychosis and met the early initial prodromal state criteria. The control group were given supportive therapy sessions which only provided minimal support involving psychoeducation and counselling.

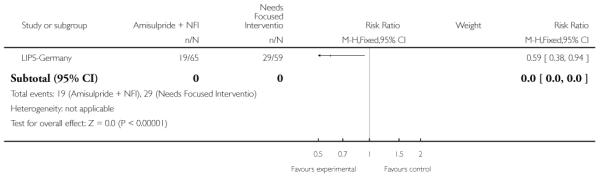

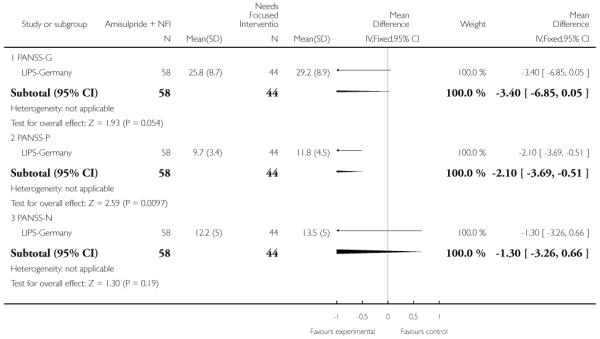

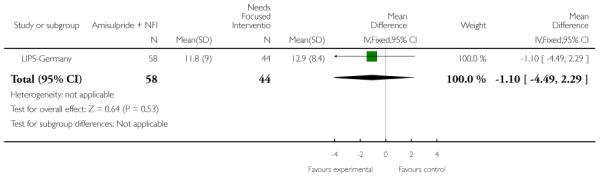

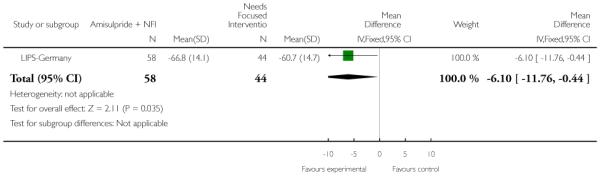

LIPS-Germany employed a needs focused intervention combined with amisulpride (mean dose 118 mg/day) in participants judged at risk of psychosis because of the presence of prodromal symptoms. The control group also received the needs focused intervention but without amisulpride. The needs focused intervention included psychoeducation, crisis intervention, family counselling and assistance with education or work related difficulties according to the patient’s need.

The Early Detection and Intervention Evaluation trial (EDIEUK) used cognitive therapy, limited to a maximum of 26 sessions over six months, following the principles developed by Beck 1976. The therapy was problem-orientated and time limited and was carried out by experienced cognitive therapists. Both control and treatment group received regular monitoring. Whilst participants (treatment and control) were not given medication, both treatment and control received elements of case management in order to resolve crises regarding social issues and mental health risk.

In PACE-Australia the intervention involved prescription of low dose risperidone (1-2 mg/day) combined with modified CBT, which aimed to enhance understanding and control of symptoms. Both the intervention and control groups also received case management from a PACE therapist. This involved supportive psychotherapy, assistance with accommodation and education/employment, and family support. Participants in the control and intervention groups received standard treatment if they developed psychosis, but control patients were not otherwise prescribed neuroleptics. Both groups could be prescribed antidepressants and benzodiazepines.

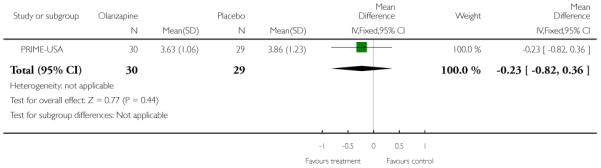

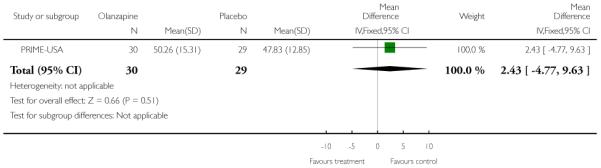

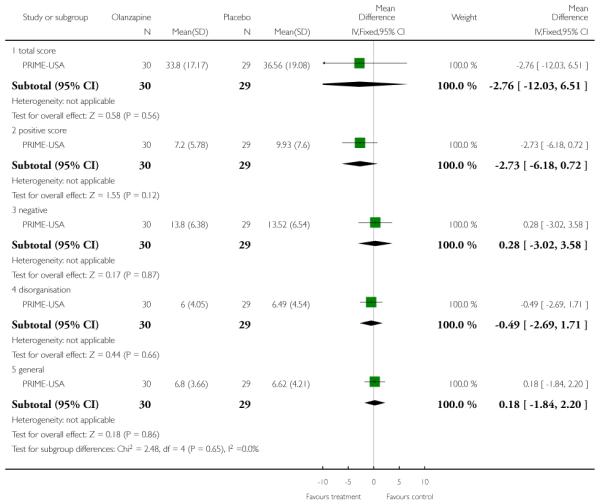

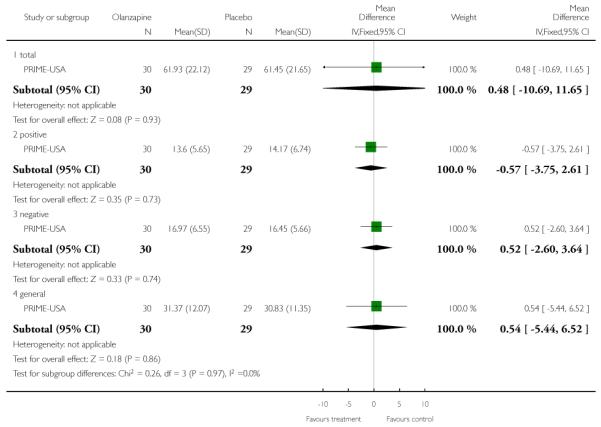

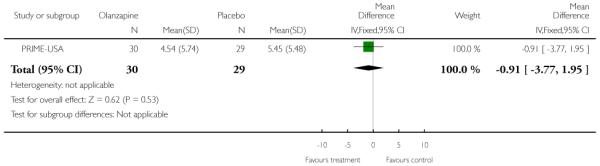

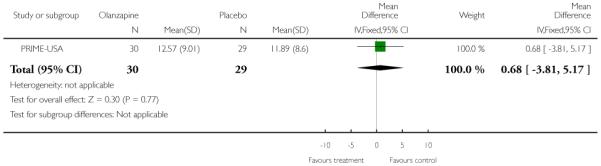

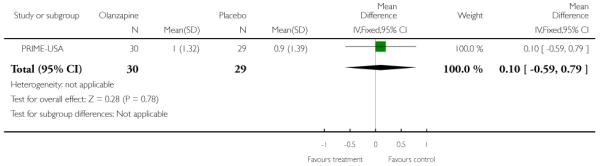

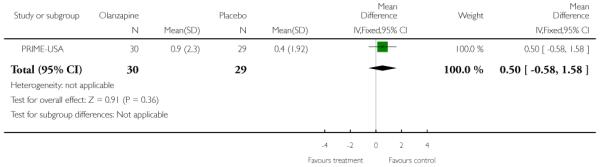

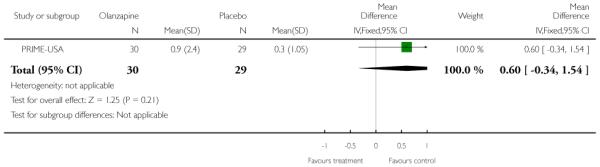

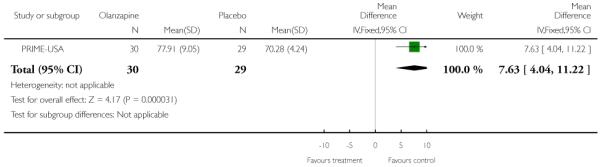

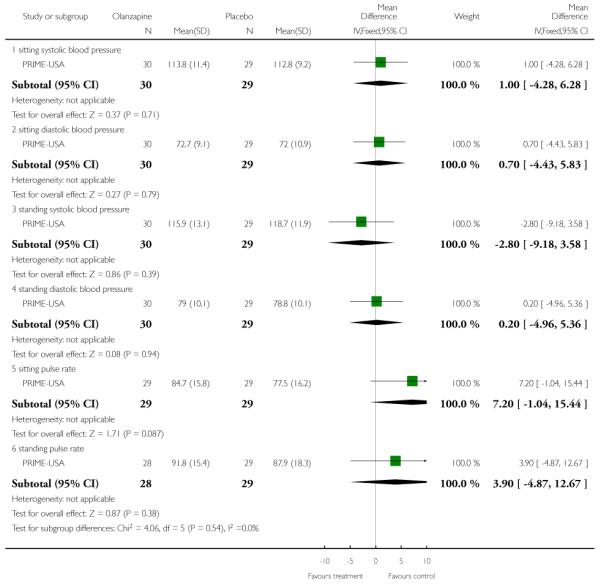

The Prevention through Risk Identification Management and Education study (PRIME-USA) randomised participants to olanzapine 5-15 mg/day (mean 8 mg/day) or placebo for one year, and then followed up for a further year without medication. Individual and family psychosocial interventions with supportive and psychoeducational components were available to all patients during the first year. The nature of the psychoeducational components varied across sites despite efforts to apply them in a uniform way. The psychosocial intervention available at the New Haven centre was modelled on the Problem Solving Training approach (D’Zurilla 1971; D’Zurilla 1986).

4.2 Trials to improve the outcome of first-episode psychosis

Twelve trials were concerned with improving outcome in first-episode psychosis (Alvarez-Spain; Berger-Australia; Edwards-Australia; Jackson-Australia; Killackey-Australia; Leavey-UK; LEO-CAT-UK; LifeSPAN-Australia; Linszen-Amsterdam; OPUS-Scandinavia; Uzenoff-USA; Zhang-China).

In Alvarez-Spain, drug naive first-episode participants were randomised to three different antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, haloperidol) and then randomised to either Early Behavoural Intervention or the control group (routine clinical care).

In Berger-Australia, the first-episode psychosis participants were given ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid oil (E-EPA) at a dose of 500 mg twice Daily, with a flexible dose of atypical antipsychotics. The control group received placebo capsules with a flexible dose of atypical antipsychotics.

In Edwards-Australia, the intervention group received a behavioural modification intervention, Cannabis and Psychosis Therapy (CAP). This consisted of weekly sessions of CBT provided by trained clinicians over three months. The aim of the CAP intervention was to reduce cannabis intake and to improve clinical and psychosocial functioning. CAP involved an assessment of engagement, followed by education about cannabis and psychosis and developing motivation to change. The focus of therapy was determined by the phase of commitment to change and could include further educational sessions, motivational interviewing, goal setting, and discussion about relapse prevention. An active control group was used which consisted of psychoeducation, which explained psychosis, medication and other treatments, and relapse prevention, but did not discuss cannabis.

In Jackson-Australia, the intervention group received CBT with 20 sessions provided for 45 minutes, plus antipsychotics. The control group were given a befriending service in addition to antipsychotics.

In Killackey-Australia, the intervention group received individual placement and support, which is an intervention designed to help people with mental illness to find and keep competitive employment. The support provided in the programme continued after employment was obtained, and was adapted to the needs of the individual. The control group received treatment as usual.

In Leavey-UK, the intervention group received a brief intervention and treatment as usual. The brief intervention was provided over seven sessions, lasting about one hour, and included: information gathering from the relative, plus sessions on: psychotic illness, symptoms and early warning signs, treatment, help seeking; coping strategies, problem solving and communication with the patient. The control group were given treatment as usual.

LEO-CAT-UK was a cluster-randomised trial in which primary care (GP) practices were randomly allocated to receive training in early detection of psychosis and direct access to LEO-CAT (a specialised treatment team for first-episode psychosis). The control group of General Practice clinics did not receive training in early detection and continued to refer new cases of psychosis to local mental health services who could then refer on to the LEO-CAT programme.

In LifeSPAN-Australia, the intervention group received standard clinical care plus LifeSPAN therapy which draws on the experience at EPPIC with Cognitive Orientated Therapy for Early Psychosis (COPE) and suicide manuals such as Choosing to Live and Cognitive Therapy of Suicide Behaviour. Four phases are used for the intervention: (a) initial engagement, (b) suicide risk assessment/formulation, (c) cognitive modules and (d) final closure/handover.

In Linszen-Amsterdam the intervention was behavioural family therapy for one year. Eighteen family therapy sessions were held over a 12-month period. Each family was treated by two co-therapists, from a team of two psychologists and one social worker, all of whom had at least one year of experience in providing family interventions for schizophrenia. The intervention was based on the behavioural family management approach of Falloon 1984 and involved psychoeducation, communication training and development of problem solving skills. Both intervention and control groups also received care from a specialised first-episode team involving individual-oriented therapy consisting of maintenance medication and disease and stress management.

In OPUS-Scandinavia, participants received integrated treatment or standard care. Integrated treatment consisted of high fidelity assertive community treatment supplemented by behavioral family therapy and social skills training. Standard care consisted of care at a community mental health centre. All participants were offered antipsychotic drugs according to guidelines from the Danish Psychiatric Society, which recommends a low-dose atypical antipsy chotic strategy for first episodes of psychotic illness. Each participant was usually in contact with a physician, community mental health nurse and in some cases a social worker. In a small proportion of cases, standard care also included psychosocial interventions such as training in social skills or Daily living activities, or supportive contacts with the family. Antipsychotics were given to both groups based on the psychiatrists’ clinical assessment.

The Uzenoff-USA study provided participants with Adherence Coping Education (ACE) which consists of 14 sessions lasting between 30 and 45 minutes over six months. It is a manual-based psychotherapy grouped into four phases: (1) establishing therapeutic alliance; (2) promoting treatment adherence; (3) developing a plan for maintenance treatment and (4) rehabilitation. The control group received supportive therapy which involved (1) establishing the therapeutic relationship, and (2) providing emotional support plus discussion of non-illness issues or topics.

Zhang-China also used family therapy, but in the form of group and individual family sessions which were delivered on an outpatient basis over the 18-month follow-up period. Both intervention and control groups also received care from the outpatients department, (consisting of medication and review) but no regular appointments or community follow-ups were provided.

5. Trial duration

The six trials concerned with preventing the onset of psychosis reported data from between two months and two years:EIPS-Germany at 12 months; EDIE-UK at 12 months and 36 months; PACE-Australia at six and 12 months (the first six months being the period during which the intervention was received);PRIME-USA at two months, 12 months (first 12 months study intervention given) and 24 months (last 12 months without intervention); LIPS-Germany at three months (although the study is planned to last 24 months), and Amminger-Austria at three months.

The 12 trials concerned with improving outcome of first-episode psychosis also reported data at various time points (range three months to five years): Alvarez-Spain reported data at 13 weeks; Berger-Australia reported data at three months; Jackson-Australia followed participants for 12 months; Leavey-UK reported data at nine months. Four trials (Edwards-Australia; Killackey-Australia; LifeSPAN-Australia; Uzenoff-USA) reported data at six months. Linszen-Amsterdam reported at 12 months following an initial three-month inpatient admission and also reported a five-year follow-up, but data were provided for the whole sample only, not by group allocation. OPUS-Scandinavia reported data at 12 and 24 months, whereas Zhang-China reported at 18 months.

6. Outcomes

6.1 Non-scale data

We were able to report dichotomous data on suicide, death, leaving the study early, conversion to psychosis, adverse effects, hospital admission, days in hospital, compliance with medication, antipsychotic drug use, living independently and employment.

6.2 Scale derived data

Only details of the outcome scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusions of data are given under ‘Outcomes’ in Characteristics of included studies.

6.2.1 Global state scales

a. Global Assessment of Functioning - GAF (APA 1994)

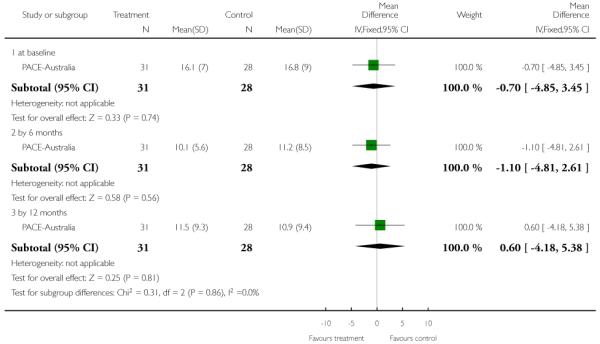

This is an observer rated scale for measuring overall severity of functional impairment. GAF consists of nine behavioural descriptors. Patients are rated between 0 (most severe) and 90 (least severe) for each descriptor. PRIME-USA, PACE-Australia, OPUS-Scandinavia and LIPS-Germany reported data from this scale.

b. Clinical Global Impression - CGI (Guy 1970)

The CGI is a three-item scale commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. The items are: severity of illness; global improvement and efficacy index. A seven-point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale.

c. Knowledge About Psychosis Questionnaire - KAPQ (Birchwood 1992)

This questionnaire tests the patients understanding about psychosis and treatments. Data from this scale were reported by Edwards-Australia.

6.2.2 Mental state scales

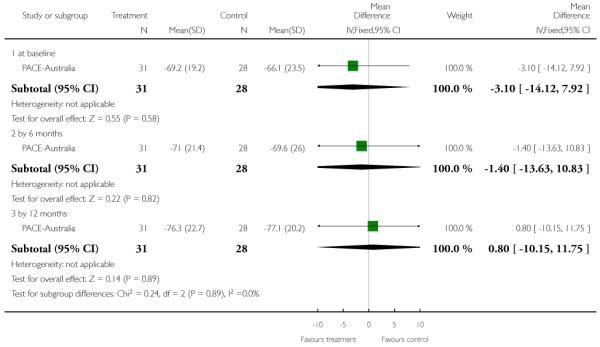

a. Brief Psychopathological Rating Scale - BPRS (Overall 1962)

The BPRS is an 18-item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18-item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0-126. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale varying from ‘not present’ to ‘extremely severe’, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Data from this scale were reported by Edwards-Australia. In PACE-Australia the scale was used primarily to report severity of psychotic symptoms.

b. Positive and Negative Symptom Scale - PANSS (Kay 1987)

The Positive and Negative Symptom Scale was developed from the BPRS and the Psychopathology Rating Scale. It is used as a method for evaluating positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. The scale has 30 items, and each item can be defined on a seven-point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). This scale can be divided into three sub-scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS-P) and negative symptoms (PANSS-N). A low score indicates low levels of symptoms. EDIE-UK used this scale to determine transition to psychosis. PRIME-USA and LIPS-Germany reported data from the PANSS.

c. Scale of Psychotic Symptoms - SOPS (Miller 1999)

The SOPS scale was modelled on the PANSS scale and is designed to measure the presence/absence of prodromal states. It consists of five positive symptom items, six negative symptom items, four disorganisation symptoms items, and four general symptom items. Each has a severity rating from 0 (never, absent) to six (severe/extreme - and psychotic for the positive items). The severity of the prodromal state is based on the sum of the rating from the SOPS items and ranges between 0 and 114. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale.

d. Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety - HRSA (Hamilton 1959)

The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) is a rating scale developed to quantify the severity of anxiety symptoms, often used in psychotropic drug evaluation. It consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms. Each item is rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe). The 14 items consist of: anxious mood; tension; fears; insomnia; intellectual; depressed mood; somatic complaints (muscular); somatic complaints (sensory); cardiovascular symptoms; respiratory symptoms; gastrointestinal symptoms; genitourinary symptoms; autonomic symptoms and behaviour at Interview. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. PACE-Australia reported data from this scale.

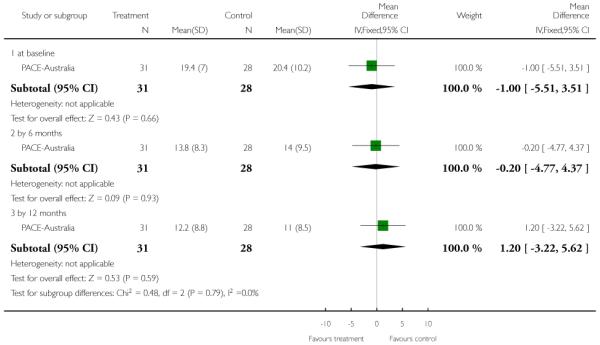

e. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression - HRSD (Hamilton 1960)

This is an interviewer rated scale for measuring depression. It is used for quantifying the results of an interview and depends on the skill of the interviewer in eliciting the necessary information. It contains 17 variables measured on either a five point or a three-point rating scale. The variables include: depressed mood; suicide; employment and loss of interest; retardation; agitation; gastrointestinal symptoms; general somatic symptoms; hypochondriasis; loss of insight and loss of weight. Higher scores indicate more severe depression. PACE-Australia reported data from this scale.

f. Calgary Depression Rating Scale - CDRS (Addington 1990)

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia is a nine-item scale ( 0=absent; 1=mild; 2=moderate; 3=severe.) that was specifically developed for assessment of depression in patients with schizophrenia. It has been evaluated in both relapsed and remitted patients, and is provided as a semi-structured interview. High scores indicated worse outcome. Uzenoff-USA reported data from this scale.

g. Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale - MADRS (Montgomery 1979)

This is a 65-item comprehensive psychopathology scale used to identify the 17 most commonly occurring symptoms in primary depressive illness. Ratings are based on 10 items, with higher scores indicating more symptoms. This scale was used by LIPS-Germany.

h. Beck Depression Inventory - BDI-SF (Beck 1961)

This is a 21-item self-rating scale for depression. Each item comprises four statements (rated 0-4) describing increasing severity of the abnormality concerned. The person completing the scale is required to read each group of statements and identify the one that best describes the way they have felt over the preceding week. A total of 12/13 is an indicative score for presence of significant depression. The short form of this scale was used by Edwards-Australia.

i. Presence of Psychosis Scale - POPS (Olsen 2006)

The Presence of Psychosis Scale (POPS), is part of the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes scale (SIPS). It marks onset of psychosis by the presence of positive symptoms at the psychotic level of intensity and of sufficient frequency and duration. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale.

j. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms - SANS (Andreasen 1983)

This is also an interviewer rated scale for measuring the severity of negative symptoms of schizophrenia such as alogia, affective blunting, avolition-apathy, anhedonia-asociality and attention impairment. Items are rated on a six-point scale with higher scores indicating more symptoms. Edwards-Australia and PACE-Australia reported data from this scale.

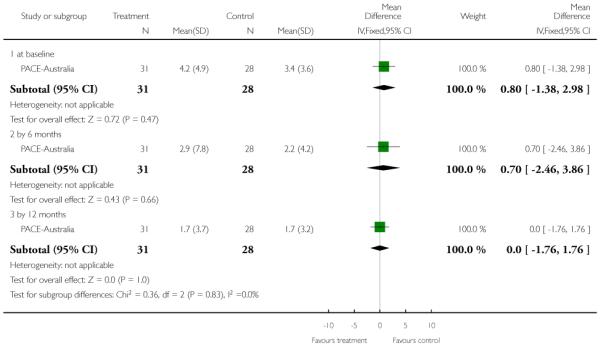

k. Young Mania Scale - YMS (Young 1978)

Again an interviewer rated scale, but this time for measuring the severity of symptoms of mania. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. PRIME-USA and PACE-Australia reported data from this scale.

6.2.3 Social functioning

a. Social Functioning Scale II - SAS II (Weissman 1976)

The SAS II is an interviewer-administered scale adapted from the self-report Social Adjustment Scale for use with people with schizophrenia. It contains 52 questions that are administered in a semi-structured interview by a trained rater. The SAS II assesses current functioning with scores ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse functioning. EIPS-Germany reported data from this scale.

b. Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale - SOFAS (APA 1994)

The SOFAS is a new instrument similar to the Global Assessment of Functioning is format, and attempts to assess the social and or occupational functioning independent of the overall severity of the illness. Higher scores indicate worse social functioning. Edwards-Australia and Jackson-Australia reported data from this scale.

6.2.4 Adverse effects

a. Simpson Angus Scale - SAS (Simpson 1970)

The SAS is a 10-item scale used to evaluate the presence and severity of drug-induced parkinsonian symptoms. The 10 items focus on rigidity rather than bradykinesia and do not assess subjective rigidity or slowness. The scale comprises a 10-item rating scale, each item rated on a five-point scale with zero meaning the complete absence of condition and four meaning the presence of condition in extreme. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale,

b. Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale - BAS (Barnes 1989)

The Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale is a four-item scale to assess the presence and severity of drug-induced movement disorder akathisia. It is a widely used comprehensive rating scale for akathisia. Items include restless movements that characterise akathisia, the subjective awareness of restlessness and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from zero (normal) to three (severe). In addition, there is an item for rating the global severity that starts from zero (absent) to five (severe). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale.

c. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale - AIMS (Guy 1976)

The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale has been used to assess abnormal involuntary movements associated with antipsychotic drugs, such as tardive dyskinesia and chronic akathisia, as well as ‘spontaneous’ motor disturbance related to the illness itself. Tardive dyskinesia is a long-term, drug-induced movement disorder. However, using this scale in short-term trials may also be helpful to assess some rapidly occurring abnormal movement disorders such as tremor. Scoring consists of rating movement severity in the anatomical areas (facial/oral, extremities, and trunk) on a five-point scale (0-4). A low score indicates low levels of dyskinetic movements. PRIME-USA reported data from this scale.

6.2.5 Quality of life

a. Quality of Life Scale - QLS (Heinrichs 1984)

This is a semi-structured interview administered and rated by trained clinicians. It contains 21 items rated on a seven-point scale based on the interviewer’s judgement of patient functioning. Higher scores indicate better quality of life. PACE-Australia and Uzenoff-USA reported data from this scale.

6.2.6 Satisfaction with care

a. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire - CSQ-8 (De-Wilde 2005)

The CSQ-8 is an eight-item self-report of global measure of patient satisfaction with services. The CSQ is substantially correlated with treatment dropout, number of therapy sessions attended, and with change in client-reported symptoms. The CSQ-8 consists of eight items rated on a four-point Likert scale. The items are concerned with quality of services received, how well services met the client’s needs and general satisfaction. The total score ranges from eight to 32. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction of the responders OPUS-Scandinavia reported data from this scale.

6.2.7 Substance use

a. Cannabis and Substance Use Assessment Schedule - CASUAS (Wing 1990)

This scale measures the percentage of days using cannabis in the past four weeks and includes an index of severity of cannabis use. The scale is modified from the Schedule for Clinical Assessment on Neuropsychiatry and includes similar information to the Addiction Severity Index. Data from this scale were used by Edwards-Australia.

6.3 Redundant data

Some studies reported data only as P values or statements of significant or non-significant differences, and other continuous data could not be extracted because the number of participants was missing or standard deviations were not reported.

Excluded studies

There are currently 68 excluded studies. We have summarised reasons for exclusion in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reasons for excluding studies

1. Awaiting classification

Thirty studies are awaiting assessment; 13 are brief reports where additional data are required; seven Chinese studies require further clarification; five studies are unclear regarding whether the status of participants is first episode or not; five studies are being sought. Ultimately, we will exclude studies where data are unobtainable.

2. Ongoing studies

We are awaiting data from 10 studies (see descriptions in Characteristics of ongoing studies table). This is an active area for research.

Risk of bias in included studies

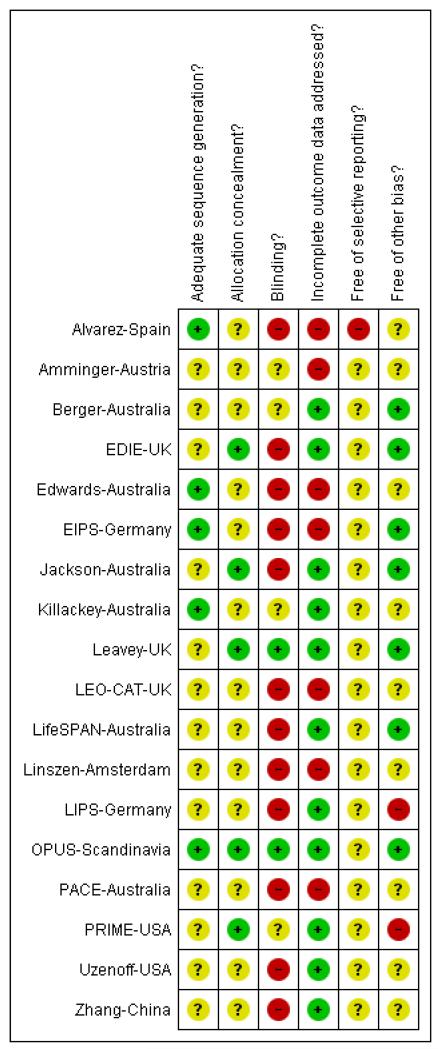

Judgement of risks are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

All 18 included studies were stated to be randomised. Only five described how randomisation had been performed, using computer-generated random numbers (Alvarez-Spain; Edwards-Australia; EIPS-Germany; Killackey-Australia; OPUS-Scandinavia). Attempts to conceal allocation were described in five studies which were judged to be adequately concealed. In the remaining studies allocation concealment was either not described or only briefly commented on and we were unable to determine in these instances if concealment is adequate.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and clinicians proved difficult in most studies. PRIME-USA blinded participants, investigators and dispensers to group assignment. Other studies used independent raters, some of whom were blind to allocation. PACE-Australia and OPUS-Scandinavia used raters who were independent of the study group, but were not blind to treatment allocation. In EDIE-UK, single blinding was attempted for the rater, but blinding was not maintained due to participants divulging information, or using language that suggested they were receiving cognitive therapy. Edwards-Australia and Leavey-UK also used a single blind design. Zhang-China used independent raters blind to allocation, whereas the LifeSPAN-Australia study was described as only single blind. In Linszen-Amsterdam the status of the raters was unclear. EIPS-Germany did not state whether blinding had been attempted. Berger-Australia and Amminger-Austria used a double-blind design, whilst LIPS-Germany was an open-label study. In the LEO-CAT-UK study, the unit of randomisation were the GP practices and clinicians were not blinded to the intervention. Both Alvarez-Spain and Jackson-Australia used a single blinding. In Killackey-Australia blinding was not reported. Uzenoff-USA used blind raters. Overall, due to the nature of the intervention, blinding proved difficult in these studies and most studies are at risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Follow-up rates where reported were quite high (see Table 2). Overall, study attrition did not suggest a risk of bias.

Table 2.

Percentage followed up

| Study | Duration of follow up (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | |

| Amminger-Austria | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Berger-Australia | 86% | |||

| EDIE-UK | 60% | |||

| Edwards-Australia | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| EIPS-Germany | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Jackson-Australia | 82% | |||

| Killackey-Australia | 75% | |||

| Leavey-UK | 79% (9 months) | |||

| LEO-CAT-UK | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| LifeSPAN-Australia | 75% | |||

| Linszen-Amsterdam* | unclear | |||

| LIPS-Germany | 61% | |||

| OPUS-Scandinavia | 77% | 67% | ||

| PACE-Australia | 100% | |||

| PRIME-USA | 84% | 72% | ||

| Uzenoff-USA | 79% | |||

| Zhang-China | 94% | |||

Loss to follow-up did not appear to be substantial

Outcomes were recorded, reported and analysed in many different ways. Even in this limited, relatively recent, research community, there is no indication of a consistency of approach and incomplete and selective reporting could easily be operating. PACE-Australia provided all outcomes on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. EDIE-UK used an ITT analysis but two people originally randomised to the treatment group were subsequently omitted from the analysis because they were found to be psychotic at the time of randomisation. (Because these exclusions are not compatible with an ITT analysis of relapse we counted such data as relapses and included these in the final analysis.)PRIME-USA also used an ITT analysis and reported scale data as change scores rather than endpoint scores. LifeSPAN-Australia only provided dichotomous data for leaving the study early and suicide. Linszen-Amsterdam only provided data on relapse at 12 months on an ITT basis. Berger-Australia only reported usable data on the number of participants not responding to treatment. Jackson-Australia did not report data on relapse or severity of illness, only data on hospitalisation, suicide and social functioning were usable. Killackey-Australia only reported usable data for employment and attrition. Leavey-UK used an ITT analysis. In the EIPS-Germany study 15 participants were not accounted for after randomisation. OPUS-Scandinavia used an ITT analysis. Zhang-China reported data on number of people readmitted and compliant on an ITT basis, but data on mental state and overall functioning were reported only for people who were not admitted to hospital. (This rendered data unusable.) Uzenoff-USA included only 24 participants and used a modified ITT analysis on 19 of this group. This small sample may have resulted in treatment effects being undetected. In Amminger-Austria, five participants were not accounted for after randomisation and is a potential source of bias to the outcome data. In LEO-CAT-UK much of the data were unusable due to the reporting of outcomes without the denominator; additionally, we divided binary data by a design effect to adjust for the excessive weight given to this cluster randomised trial. Edwards-Australia used the last observation carried forward method and all 47 participants were utilised in the reporting of outcome data.

Selective reporting

Outcome data from the SAPS scale were not reported by Alvarez-Spain. We did not identify overt under reporting of outcomes in the other included studies, although we did not have access to study protocols to check whether other data were recorded and not reported in the final papers.

Other potential sources of bias

Six of the 18 studies were undertaken at the pioneering EPPIC Centre in Melbourne, Australia (Berger-Australia; Edwards-Australia; Jackson-Australia; Killackey-Australia; LifeSPAN-Australia; PACE-Australia). This could lead to issues with applicability (see Overall completeness and applicability of evidence). However, as with the Australian studies, many of the trials were undertaken by leading figures in the world of early intervention who could have a vested interest in the findings - just as industry has in the outcomes for the drugs they manufacture. Early intervention studies are now less novel than a decade ago. The initial flourish of research has settled into a more steady stream and it will be interesting to see how findings average across time.

Effects of interventions