Abstract

Background

Oxytocin is the commonest induction agent used worldwide. It has been used alone, in combination with amniotomy or following cervical ripening with other pharmacological or non‐pharmacological methods.

Objectives

To determine the effects of oxytocin alone for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour in comparison with other methods of induction of labour or placebo/no treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (January 2009) and bibliographies of relevant papers.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials comparing intravenous oxytocin with placebo or no treatment, or with prostaglandins (vaginal or intracervical) for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed eligibility and carried out data extraction.

Main results

Sixty‐one trials (12,819 women) are included.

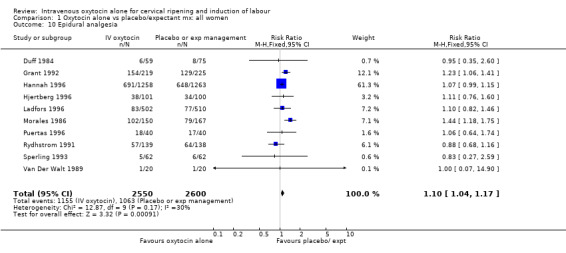

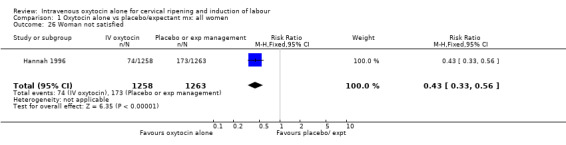

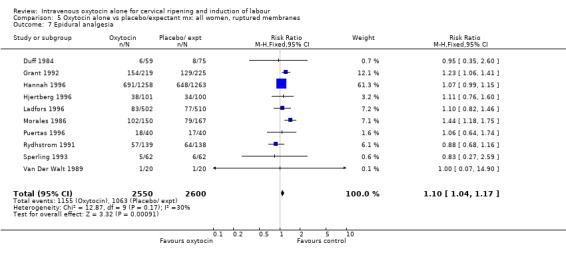

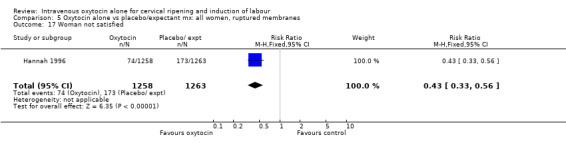

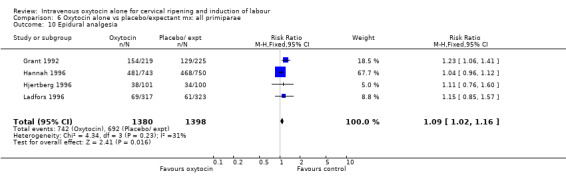

When oxytocin inductions were compared with expectant management, fewer women failed to deliver vaginally within 24 hours (8.4% versus 53.8%, risk ratio (RR) 0.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 0.25). There was a significant increase in the number of women requiring epidural analgesia (RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.17). Fewer women were dissatisfied with oxytocin induction in the one trial reporting this outcome (5.9% versus 13.7%, RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.56).

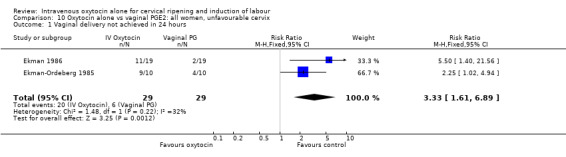

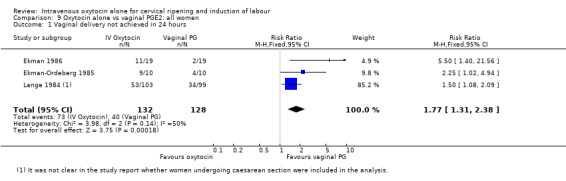

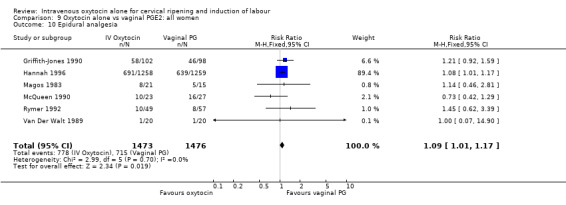

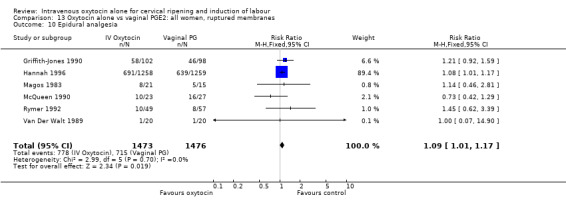

Compared with vaginal prostaglandins, oxytocin increased unsuccessful vaginal delivery within 24 hours in the two trials reporting this outcome (70% versus 21%, RR 3.33, 95% CI 1.61 to 6.89). There was a small increase in epidurals when oxytocin alone was used (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.17).

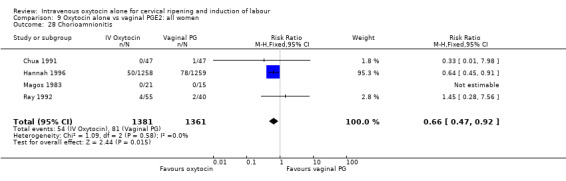

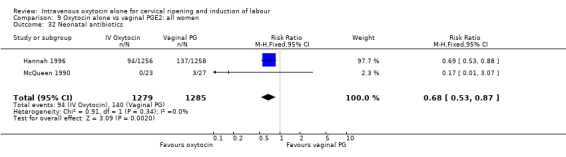

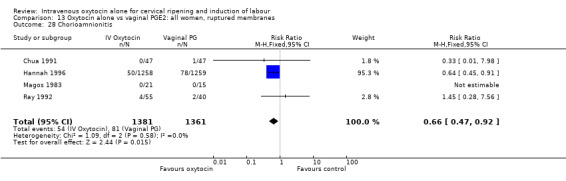

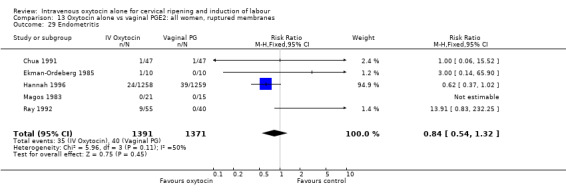

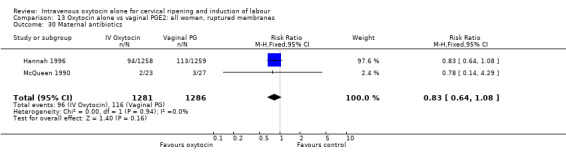

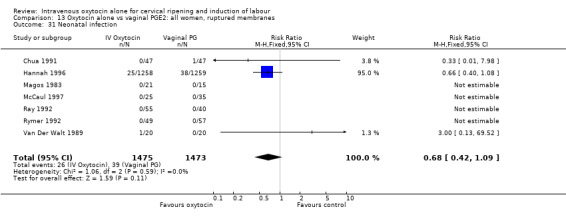

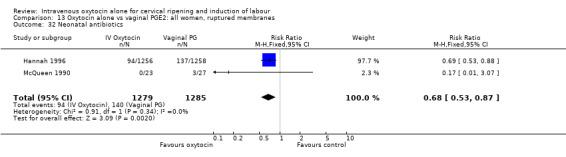

Most of the studies included women with ruptured membranes, and there was some evidence that vaginal prostaglandin increased infection in mothers (chorioamnionitis RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.92) and babies (use of antibiotics RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.87). These data should be interpreted cautiously as infection was not pre‐specified in the original review protocol.

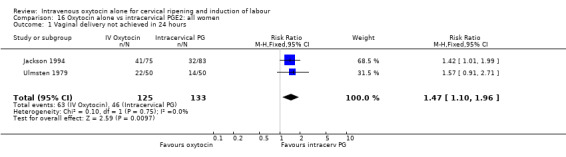

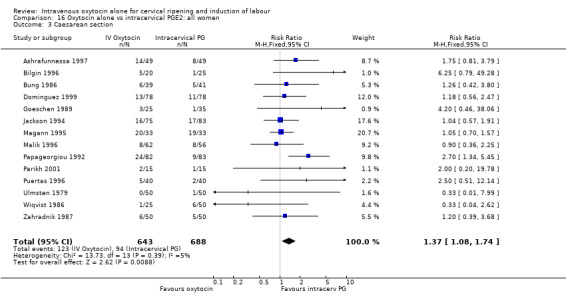

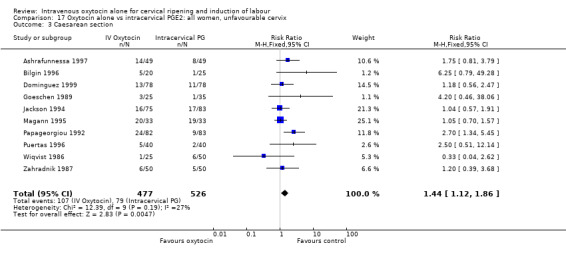

When oxytocin was compared with intracervical prostaglandins, there was an increase in unsuccessful vaginal delivery within 24 hours (50.4% versus 34.6%, RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.96) and an increase in caesarean sections (19.1% versus 13.7%, RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.74) in the oxytocin group.

Authors' conclusions

Comparison of oxytocin with either intravaginal or intracervical PGE2 reveals that the prostaglandin agents probably increase the chances of achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours. Oxytocin induction may increase the rate of interventions in labour.

A suggestion that for women with prelabour rupture of membranes induction with vaginal prostaglandin may increase risk of infection for mother and baby warrants further study.

Plain language summary

Oxytocin for induction of labour

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially, because of safety concerns either for the pregnant woman or her baby. Oxytocin is the most common drug used to induce labour and has been used either alone, with other drugs or after artificial rupture of the membranes. In this review we looked at the use of oxytocin alone for inducing labour. The review included 61 studies with more than12,000 women. Overall, oxytocin seems to be a safe method of inducing labour. Compared to waiting to see whether labour starts naturally (expectant management), giving oxytocin led to more women having their babies within 24 hours, but more women needed an epidural for pain relief. Most of the studies recruited women with ruptured membranes and the number of babies with an infection was lower with oxytocin compared with expectant management.

A comparison of oxytocin with other drugs to induce labour (vaginal or intracervical prostaglandins) showed that women were more likely to have their babies within 24 hours with prostaglandin. Fewer women had epidurals with prostaglandin. Side effects for the mother were similar in the two groups.

Background

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detail on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published generic protocol (Hofmeyr 2009).

Oxytocin is the commonest induction agent used worldwide. It has been used alone, in combination with amniotomy or following cervical ripening, with other pharmacological or non‐pharmacological methods. In developed countries, oxytocin alone is more commonly used in the presence of ruptured membranes, whether spontaneous or artificial. In developing countries where the incidence of HIV is high, delaying amniotomy in labour reduces vertical transmission rates and hence the use of oxytocin with intact membranes warrants further investigation.

This review will address the use of oxytocin alone for induction of labour. Amniotomy alone (Bricker 2000) and concomitant administration of oxytocin and amniotomy for induction of labour (Howarth 2001) have been reviewed elsewhere in The Cochrane Library. Concomitant administration is classified as when oxytocin and amniotomy are initiated within two hours of each other, irrespective of which is initiated first.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of oxytocin alone for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour in comparison with other methods of induction of labour, placebo or no treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing oxytocin alone for cervical ripening or labour induction, with placebo or no treatment, or with other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (seeData collection and analysis); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the prestated outcomes.

We have not included trials which compared different methods of administration of intravenous oxytocin (e.g. continuous or pulsatile), different preparations of oxytocin (e.g. nasal or buccal) or different dose regimens of oxytocin.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Types of interventions

Oxytocin alone compared with placebo or no treatment, or with any other method above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (which included vaginal and intracervical PGE2 or PGF2alpha).

Primary comparisons

Intravenous oxytocin versus placebo/expectant management (25 trials) Intravenous oxytocin versus vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2) (27 trials) Intravenous oxytocin versus intracervical prostaglandins (PGE2) (14 trials) Intravenous oxytocin versus vaginal PGF alpha (3 trials)

No attempt was made to compare different dose regimens of oxytocin delivery.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of Cochrane labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic).

We chose five primary outcomes as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. (1) Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours. (2) Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes. (3) Caesarean section. (4) Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood). (5) Serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes related to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction

Measures of effectiveness

(6) Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours. (7) Oxytocin augmentation.

Complications

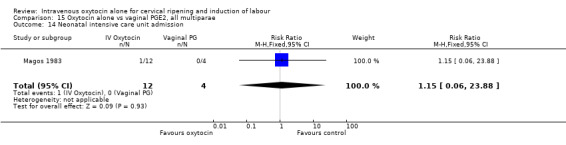

(8) Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes. (9) Uterine rupture. (10) Epidural analgesia. (11) Instrumental vaginal delivery. (12) Meconium‐stained liquor. (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes. (14) Neonatal intensive care unit admission. (15) Neonatal encephalopathy. (16) Perinatal death. (17) Disability in childhood. (18) Maternal side effects (all). (19) Nausea (maternal). (20) Vomiting (maternal). (21) Diarrhoea (maternal). (22) Other (e.g. pyrexia). (23) Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors). (24) Serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture). (25) Maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction

(26) Woman not satisfied. (27) Caregiver not satisfied.

While we sought all the above outcomes, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In reviews, the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' is defined as uterine tachysystole (greater than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes).

'Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' is defined as uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with FHR changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability). However, due to varied reporting, there is the possibility of subjective bias in interpretation of these outcomes. Also, it is not always clear from the trials if these outcomes are reported in a mutually exclusive manner.

Outcomes were included in the analysis if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias, and data were available according to original treatment allocation.

A number of non‐prespecified outcomes were collected relating to infective morbidity. These were mainly reported in the trials examining induction of labour in women with ruptured membranes. The outcomes collected were chorioamnionitis, endometritis, neonatal infection, one‐minute Apgar score less than seven and the use of maternal or neonatal antibiotics.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (January 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

The search for the previous version of this review was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of relevant papers.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

To avoid duplication of data, the authors of induction of labour reviews agreed a specific order for labour induction methods, from one to 27. Each primary review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 27) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, this review of intravenous oxytocin (4) included only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo/no treatment (1). The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2003); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin; (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2003); (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Boulvain 2001); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Neilson 2000); (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006a); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001b); (18) hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006b); (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema (Kelly 2001c); (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) nitric oxide donors (Kelly 2008); (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004); (26) hypnosis; (27) other methods for induction of labour.

The review authors have analysed the primary reviews, including this one, by the following subgroups: (1) previous caesarean section or not; (2) nulliparity or multiparity; (3) membranes intact or ruptured; (4) cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

We initially reviewed trials on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, we extracted data using a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved previous review authors in the area of induction of labour.

We extracted information regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. We completed this process without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examined the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. We then judged risk of bias as adequate, inadequate or unclear using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

We examined performance bias with regard to who was blinded in the trials, i.e. patient, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. We sought details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels.

We included individual outcome data in the analysis if they met the prespecified criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. We processed included trial data using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We analysed data extracted from the trials on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, we performed re‐analysis if possible). Where data were missing, we sought clarification from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, we planned to exclude such data from the analysis.

To examine how issues of quality influence effect size, we carried out a sensitivity analysis. In this analysis, for primary outcomes, we have set out results separately for trials where allocation concealment was adequate, poor or not described (unclear).

Once we had extracted data, we entered them into the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2008), checked for accuracy, and carried out analysis. For dichotomous data, we calculated risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We pooled results using a fixed‐effect model. If there were considerable or high levels of heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we repeated the analyses using a random‐effects model and have given both results in the text. (For those outcomes where there are high levels of heterogeneity, we would advise readers to interpret results with caution.) To assist in the interpretation of the results, we have included (unweighted) percentages to illustrate the effect of the intervention in the experimental and control groups.

Results

Description of studies

In total, we considered 133 trials; we have excluded 71 and included 61, involving 12,819 participants in total. For further details of trial characteristics please refer to the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Excluded trials

Eight trials examined intranasal or buccal oxytocin (Andreasson 1985; Bergsjo 1969; Gillot 1974; Hendricks 1964; Larsen 1983; Pentecost 1973; Sjostedt 1969; Sorensen 1985).

One trial compared synthetic to natural oxytocin (Danezis 1962).

Fifteen trials compared different regimens of oxytocin (Blakemore 1990; Crane 1993; Daniel‐Spiegel 2004; Goni 1995; Hourvitz 1996; Lazor 1993; Lowensohn 1990; Merrill 1999; Morrison 1992; Muller 1992; Parpas 1995; Ross 1998; Satin 1991; Satin 1994; Singh 1993).

Eleven trials compared pulsed with continuous delivery systems for oxytocin (Arulkumaran 1985; Ashworth 1988; Auner 1993; Cummiskey 1990; Dawood 1995; Gibb 1985; Odem 1988; Raymond 1989; Salamalekis 2000; Shennan 2006; Willcourt 1994).

Twenty trials did not focus on the selected study interventions, did not report any results, or did not have any prespecified outcomes in an extractable format (Anderson 1971; Atad 1999; Blackburn 1973; Bremme 1980; Chestnut 1994; De Leon Casasola 1993; Dietl 1987; Fuchs 2006; Gloeb 1989; Knox 1979; Leszczynska‐Gorzelak 1993; MacLennan 1988; Mokgokong 1974; Moise 1991; Mollo 1991; Morgan‐Ortiz 2002; Perales 1994; Rees 1991; Vernant 1993; Welt 1987).

Two trials only included data on induction of labour prior to term (Mercer 1993; Naef 1998).

Nine trials used complex interventions, with oxytocin and another intervention (Bredow 1990; Christensen 2001; Coleman 1997; Gonen 1997; Kashanian 2007; Kjos 1993; Mahmood 1995; Milasinovic 1997; Tan 2007).

One trial compared expectant management (with subsequent oxytocin with or without amniotomy) with intracervical prostaglandin PGE2. It was not possible to separate out the oxytocin alone data (Hannah 1992).

One trial compared oxytocin to placebo but included both women undergoing induction and augmentation (Shennan 1995). The data for the induction group were not available separately.

One used allocation on Bishops score (Bredow 1993) and in one trial some of the participants were not randomly selected (Steer 1992). In one study it was not clear that any of the women had been randomised (Srividhya 2001).

Included trials

Eight trials included more than two arms, and results appear in more than one comparison group. (Hannah 1996; Jagani 1984; McCaul 1997; Puertas 1996; Ray 1992; Roberts 1986; Van Der Walt 1989; Wiqvist 1986).

Twenty‐five trials compared oxytocin with a policy of expectant management (Akyol 1999; Alcalay 1996; Chang 1997; Damania 1992; Duff 1984; Grant 1992; Hannah 1996; Hjertberg 1996; Jagani 1984; Ladfors 1996; McCaul 1997; McQueen 1992; Morales 1986; Natale 1994; Ottervanger 1996; Puertas 1996; Ray 1992; Roberts 1986; Rydhstrom 1991; Sperling 1993; Tamsen 1990; Valentine 1977; Van Der Walt 1989; Wagner 1989; Wiqvist 1986).

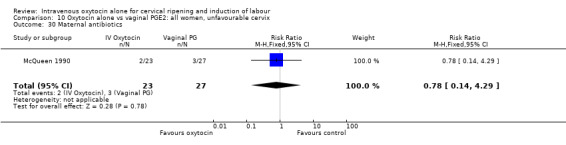

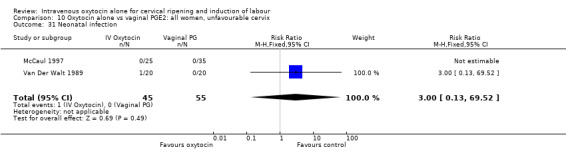

Twenty‐seven trials compared oxytocin with vaginal PGE2 (Andersen 1990; Atad 1996; Chua 1991; Egarter 1987; Ekman 1986; Ekman‐Ordeberg 1985; Griffith‐Jones 1990; Hannah 1996; Herabutya 1991; Jagani 1984; Lange 1984; Legarth 1987; Lyndrup 1989; Lyndrup 1990; Macer 1984; Magos 1983; McCaul 1997; McQueen 1990; Olmo 2001; Pollnow 1996; Ray 1992; Roberts 1986; Rymer 1992; Silva‐Cruz 1988; Valadan 2005; Van Der Walt 1989; Wilson 1978).

Fourteen trials compared oxytocin with intracervical PGE2 (Ashrafunnessa 1997; Bilgin 1996; Bung 1986; Dominguez 1999; Goeschen 1989; Jackson 1994; Magann 1995; Malik 1996; Papageorgiou 1992; Parikh 2001; Puertas 1996; Ulmsten 1979; Wiqvist 1986; Zahradnik 1987).

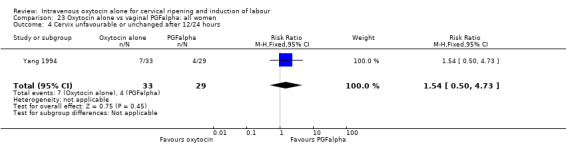

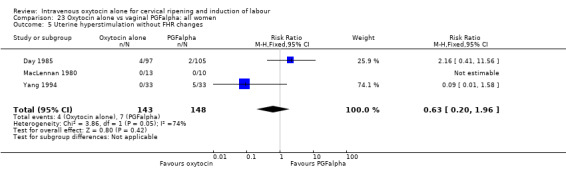

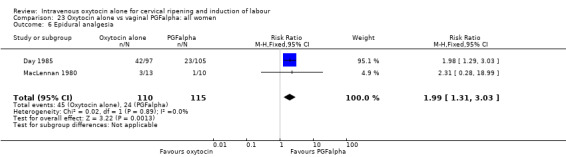

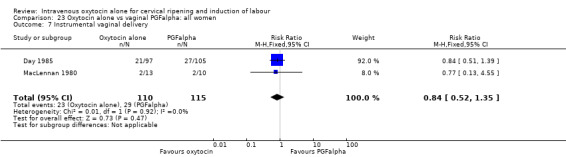

Three trials compared oxytocin with vaginal PGFalpha (Day 1985; MacLennan 1980; Yang 1994).

Thirty‐eight trials specifically examined the use of oxytocin in women with ruptured membranes. The remaining 23 either examined the role of oxytocin in women with intact membranes, where the groups included women with both intact and ruptured membranes, or were unclear regarding women's membrane status.

In trials comparing the use of oxytocin alone with vaginal or intracervical PGE2, women in the prostaglandin groups who did not achieve established labour within a specified time period may have gone on to receive oxytocin as part of the induction process.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation

Eight trials used computer‐generated lists of random numbers (Atad 1996; Hannah 1996; Ladfors 1996; Lange 1984; Magann 1995; Malik 1996; McCaul 1997; Rymer 1992).

Nine used random number tables (Alcalay 1996; Day 1985; Griffith‐Jones 1990; MacLennan 1980; McQueen 1990; McQueen 1992; Pollnow 1996; Ray 1992; Van Der Walt 1989).

Two allocated according to alternating days of the week (Duff 1984; Morales 1986).

Four trials allocated according to the last digit of the women's hospital number (Jagani 1984; Magos 1983; Papageorgiou 1992; Wagner 1989).

The remaining trials were unclear regarding the method of generation of the randomisation sequence.

Allocation concealment

Four trials used centralised randomisation (Hannah 1996; Jackson 1994; McCaul 1997; Ray 1992).

Sealed envelopes were used in 17 trials (Chang 1997; Chua 1991; Grant 1992; Griffith‐Jones 1990; Ladfors 1996; Legarth 1987; Lyndrup 1989; Lyndrup 1990; MacLennan 1980; Magann 1995; McQueen 1990; Ottervanger 1996; Pollnow 1996; Roberts 1986; Rydhstrom 1991; Rymer 1992; Sperling 1993). It was not always clear whether or not envelopes were opaque and sequentially numbered. Some authors simply referred to the "sealed envelope method".

The remaining trials were unclear about the method of concealment of allocation or used open allocation techniques. In the sensitivity analysis, for primary outcomes, we set out results from trials assessed as having adequate, unclear or inadequate allocation concealment (Table 24; Table 25; Table 26).

1. Sensitivity analysis: oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx; trials with adequate vs uncertain or inadequate allocation concealment.

| Risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals: all women | RR adequate allocation concealment | RR uncertain or inadequate allocation concealment | |

| Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hrs | 0.16 (0.10 to 0.25) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.29) | 0.17 (0.09 to 0.33) |

| Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 0.16 (0.01 to 3.34) | 0.16 (0.01 to 3.34) | No studies |

| Caesarean section | 1.14 (0.95 to 1.37) | 1.14 (0.95 to 1.37) | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.49) |

| Serious neonatal morbidity or death | 0.63 (0.26 to 1.51) | 0.38 (0.11 to 1.29) | 1.31 (0.33 to 5.22) |

| Serious maternal morbidity or death | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable |

2. Sensitivity analysis: oxytocin vs vaginal PGE2; trials with adequate vs uncertain or inadequate allocation concealment.

| Risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals: all women | RR adequate allocation concealment | RR uncertain or inadequate allocation concealment | |

| Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hrs | 2.06 (1.13 to 3.74) | No studies | 2.06 (1.13 to 3.74) |

| Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 0.35 (0.04 to 3.28) | 0.35 (0.04 to 3.28) | Not estimable |

| Caesarean section | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.30) | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.26) | 1.25 (0.98 to 1.59) |

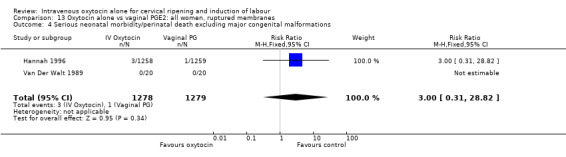

| Serious neonatal morbidity or death | 3.00 (0.31 to 28.82) | 3.00 (0.31 to 28.82) | No studies |

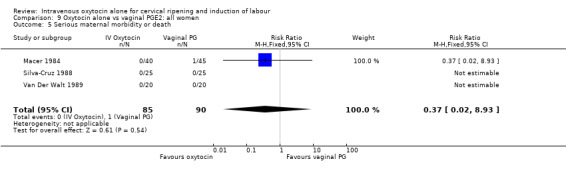

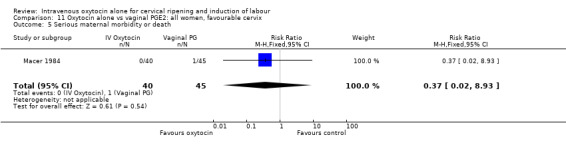

| Serious maternal morbidity or death | 0.37 (0.02 to 8.93) | 0.37 (0.02 to 8.93) | No studies |

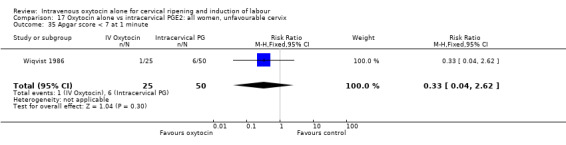

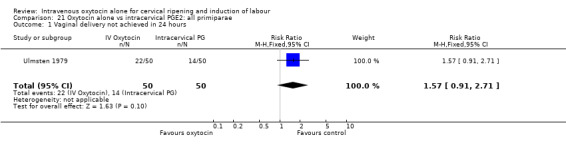

3. Sensitivity analysis: oxytocin vs intracervical PGE2; studies with adequate vs uncertain or poor allocation concealment.

| Risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals: all women | RR adequate allocation concealment | RR uncertain or inadequate allocation concealment | |

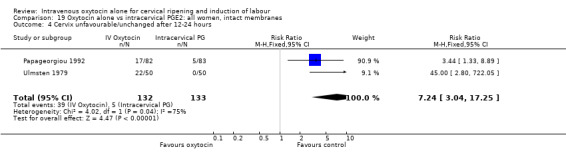

| Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hrs | 1.47 (1.10 to 1.96) | 1.42 (1.01 to 1.99) | 1.57 (0.91 to 2.71) |

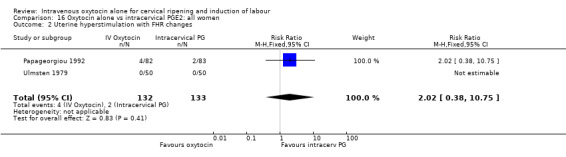

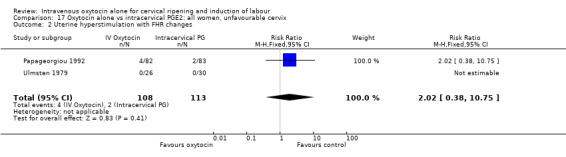

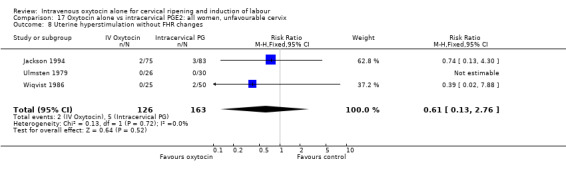

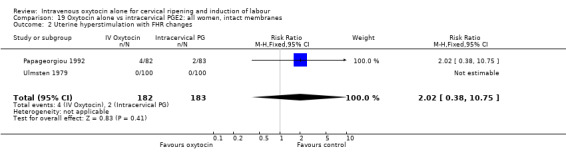

| Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 2.02 (0.38 to 10.75) | No studies | 2.02 (0.38 to 10.75) |

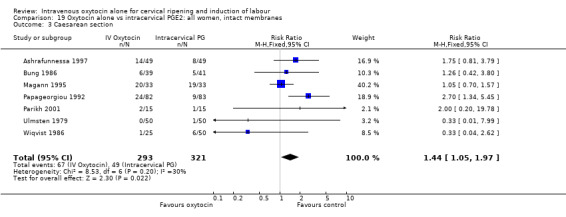

| Caesarean section | 1.37 (1.08 to 1.74) | 1.57 (1.15 to 2.14) | 1.05 (0.74 to 1.49) |

| Serious neonatal morbidity or death | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable |

| Serious maternal morbidity or death | No studies | No studies | No studies |

Blinding women, care providers and outcome assessors

Blinding women and staff in these trials was generally not attempted. Two trials did use placebo (Jackson 1994; Pollnow 1996), and in two further trials, which included more than two arms, some women received placebo preparations (Ray 1992; Wiqvist 1986). In the study by Hannah 1996 and colleagues, assessors were blind for the assessment of some outcomes. The lack of blinding in the included studies is a potential source of bias, and this should be kept in mind in the interpretation of results.

Attrition

Loss to follow up was not a serious problem in these studies where the intervention and the recording of outcomes usually took place as part of a single care episode; there was little longer‐term follow up. Where there were missing data, this has been noted in the Characteristics of included studies risk of bias tables.

Other sources of bias

Some of the studies provided little information on study methods, and this made the overall assessment of risk of bias difficult. Assessment of reporting bias is particularly difficult without access to the original study protocols, and was generally not apparent in the included studies. In one study, results for the stated primary outcome (delivery within 24 hours) were not reported (Valadan 2005). Where results were reported in an abstract rather than in a full report, sometimes only statistically significant results were reported (e.g. Bilgin 1996). Other sources of bias included unequal group sizes and imbalance in control and intervention groups in terms of group characteristics. Few studies provided full information on the numbers of women approached to take part in studies, the numbers eligible for inclusion, and the overall refusal rate. While not sources of bias as such, high exclusion and refusal rates affect the generalisability of findings and the interpretation of results. We have noted such issues in the risk of bias tables.

The size of included studies varied considerably with several trials including 30 or fewer women (Ekman 1986; Ekman‐Ordeberg 1985; MacLennan 1980; Parikh 2001); at the other end of the range, one large study alone accounted for 40% of the women included in the review (Hannah 1996).

Effects of interventions

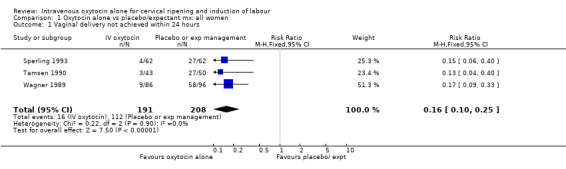

Intravenous oxytocin alone versus expectant management (25 trials; 6660 women)

Primary outcomes

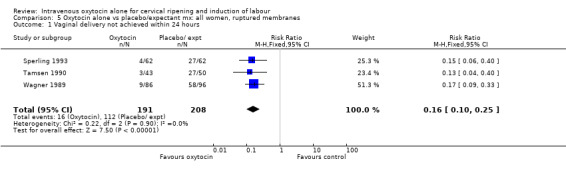

Intravenous oxytocin reduced the failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours when compared with expectant management (8.4% versus 54%, risk ratio (RR) 0.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 0.25). This outcome was reported in three trials including 399 women.

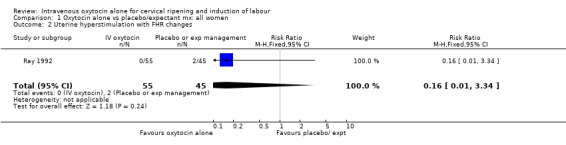

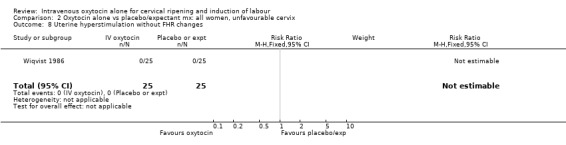

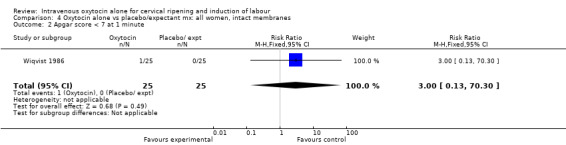

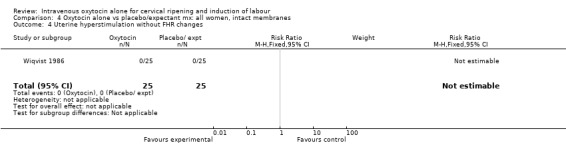

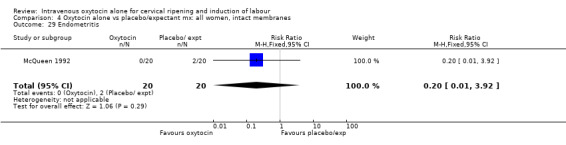

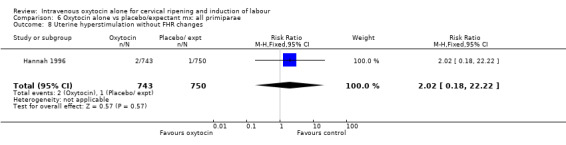

Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes was reported in only one trial with 100 women and there was no evidence of a difference between groups (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.34).

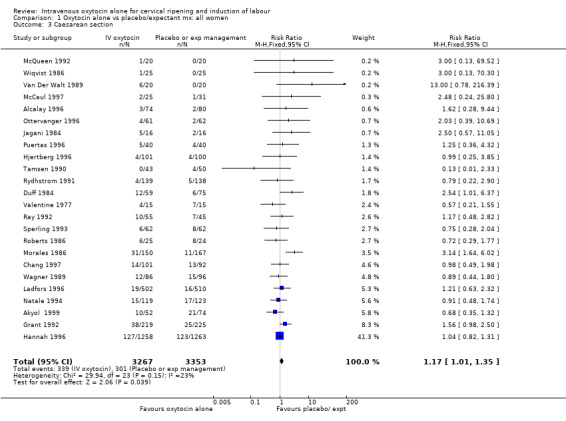

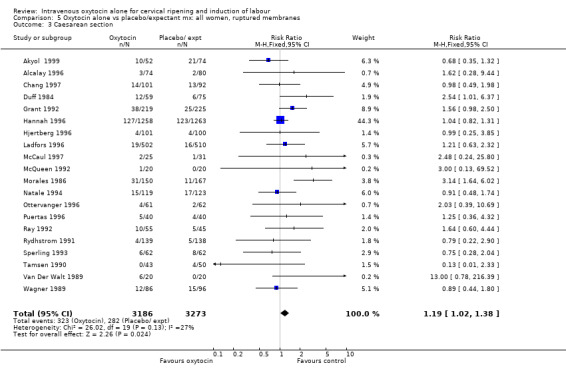

The rate of caesarean section rate was reported in most of the studies (24 trials including 6620 women) showing a small, but statistically significant increase for women in the oxytocin group (10.4% versus 9.0%, RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.35).

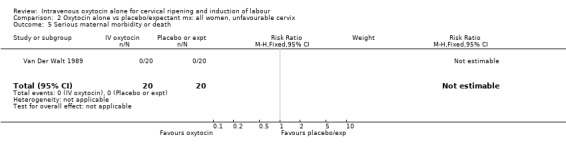

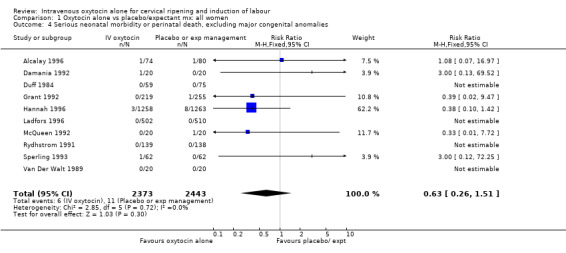

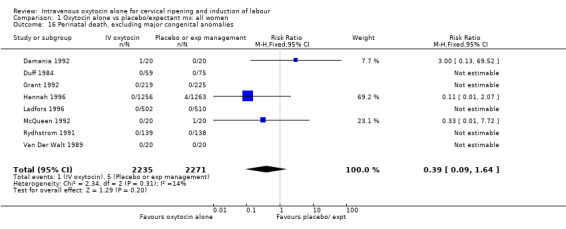

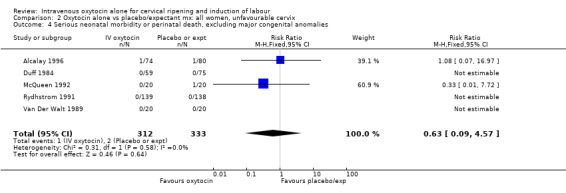

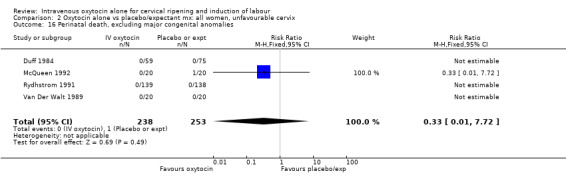

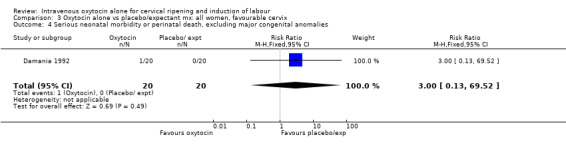

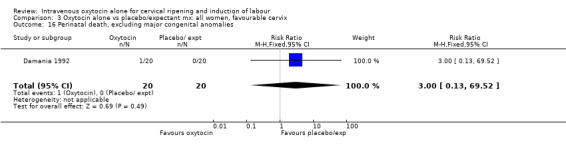

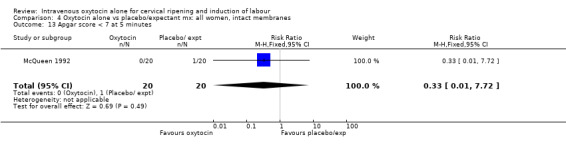

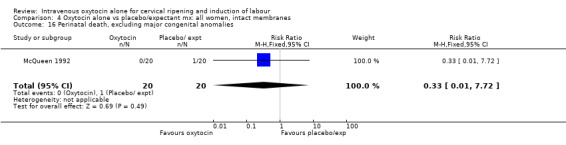

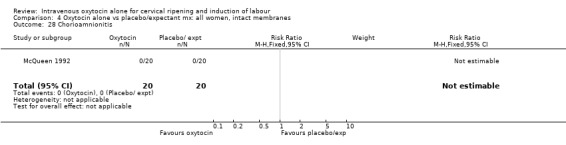

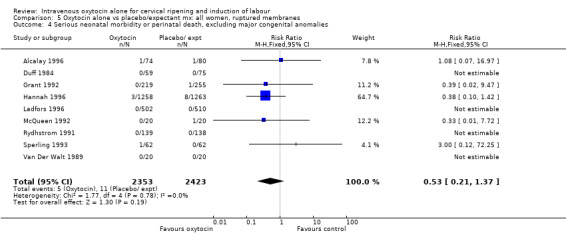

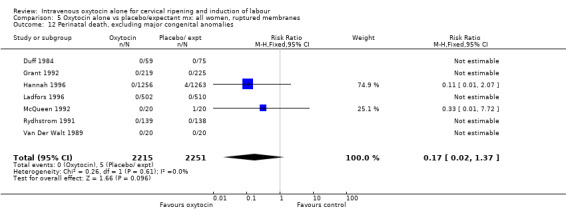

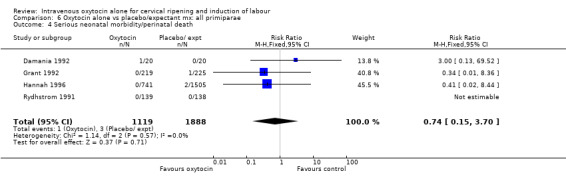

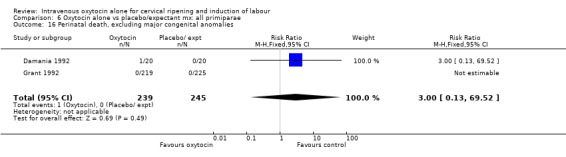

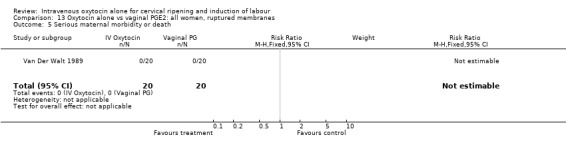

There were insufficient data to derive any meaningful conclusions regarding neonatal and maternal mortality or serious morbidity. There were 17 cases of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death in the 4816 included patients (10 studies) (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.51). Only one small trial specifically reported on maternal mortality (Van Der Walt 1989) and no cases were reported in the 40 participants.

Secondary outcomes

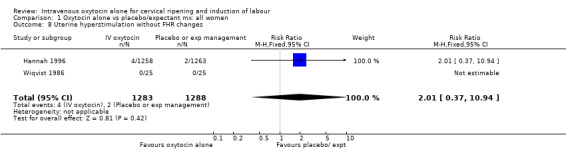

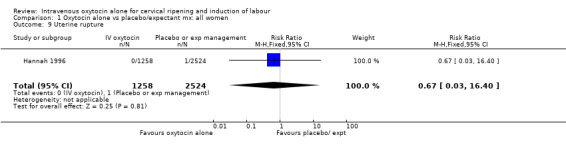

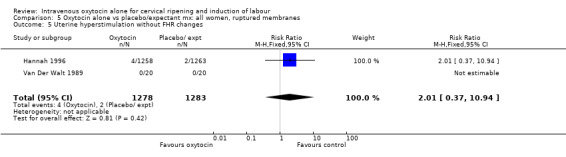

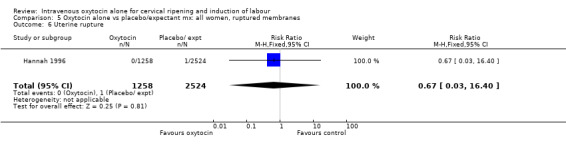

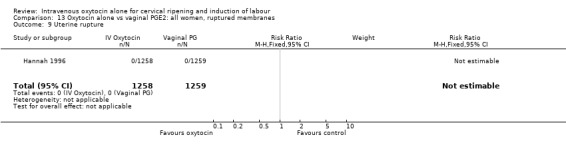

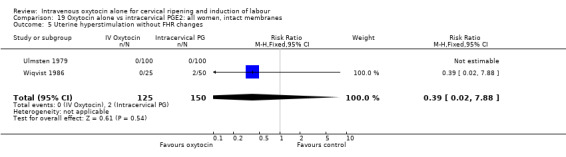

Uterine hyperstimulation was not increased when oxytocin was compared with expectant management or no treatment. Two studies (2571 women) examined the incidence of uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes, and there was no evidence of a difference between groups (RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.37 to 10.94).There was one case of uterine rupture in the control group in the one trial reporting this outcome (Hannah 1996).

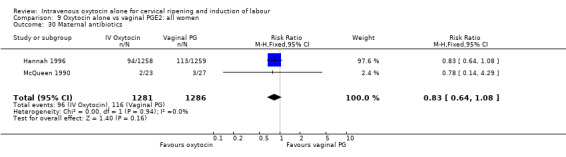

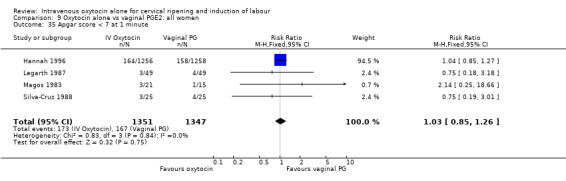

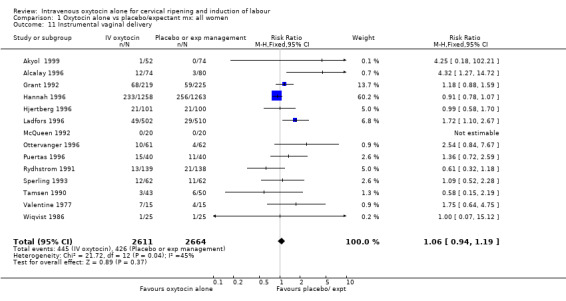

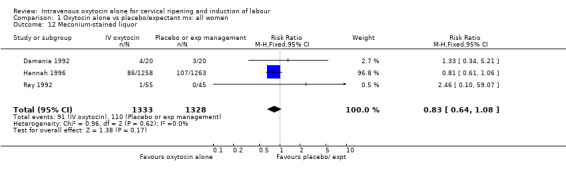

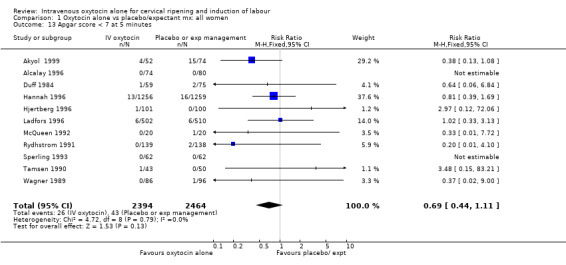

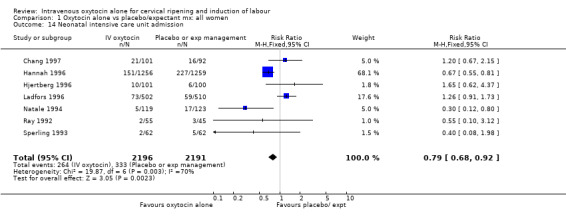

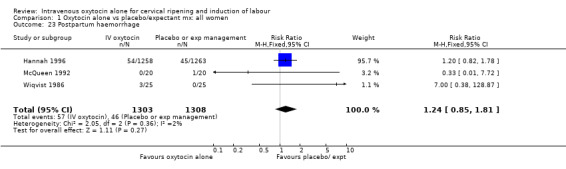

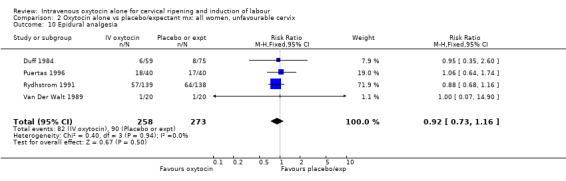

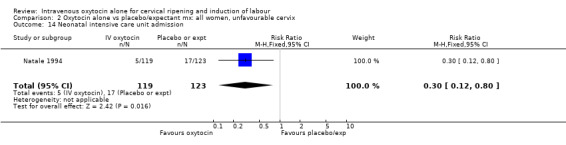

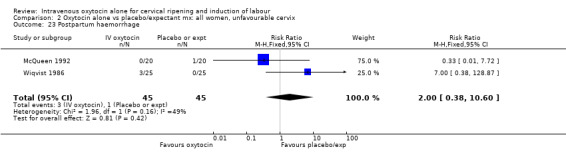

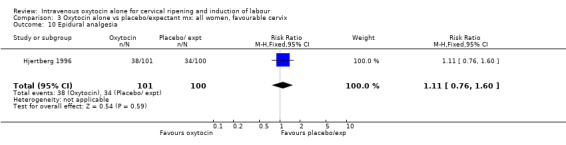

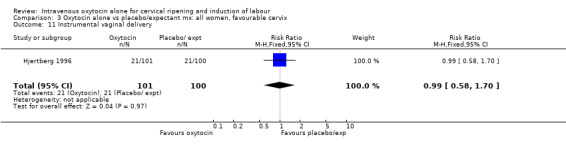

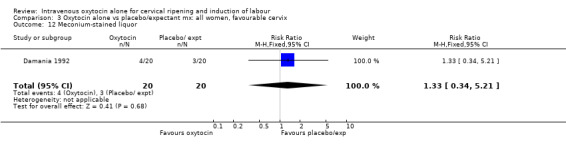

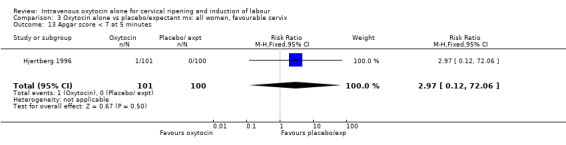

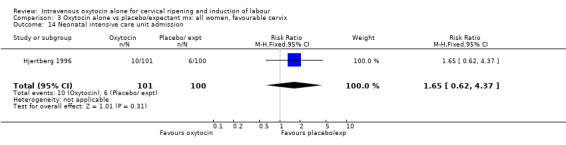

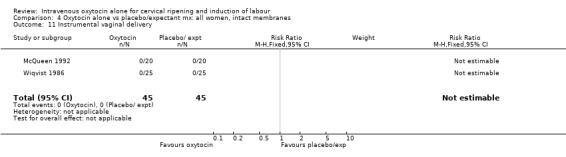

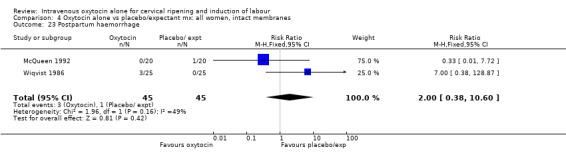

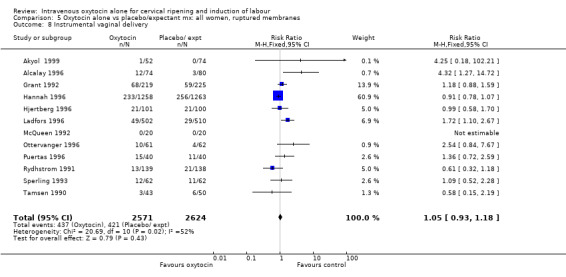

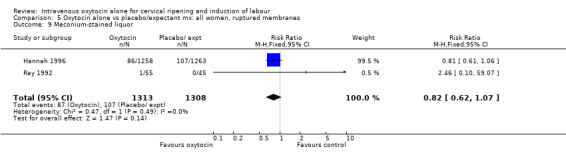

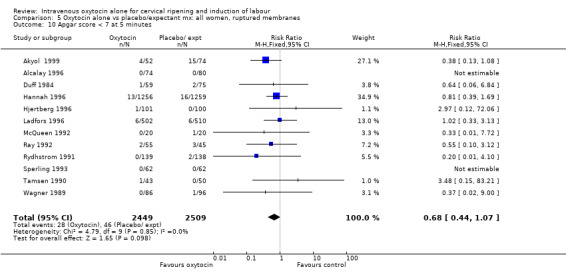

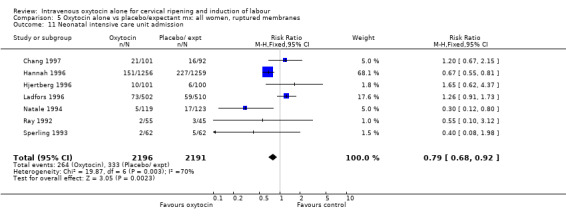

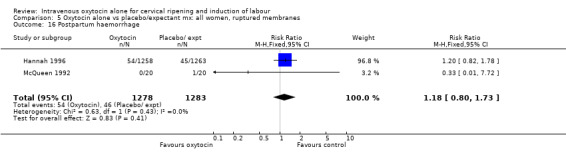

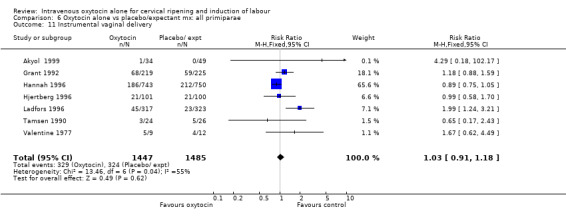

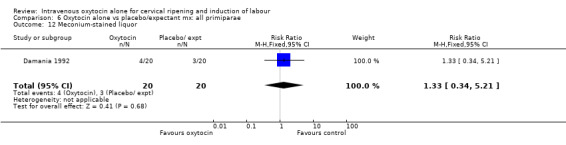

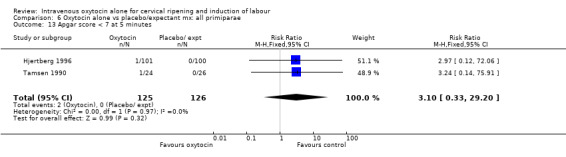

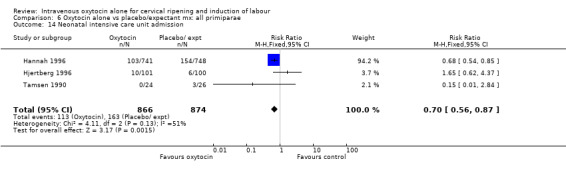

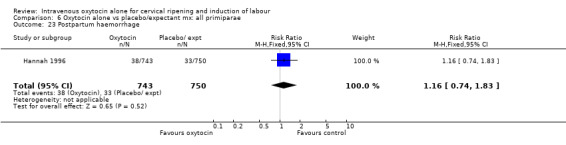

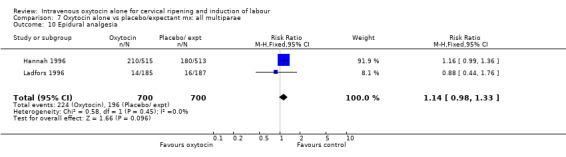

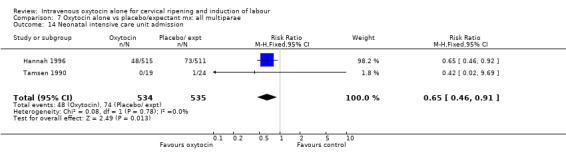

The use of epidural analgesia was increased when oxytocin alone was compared with expectant management or no treatment (45.3% versus 40.9%, RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.17) (measured in 10 trials including 5150 women). The rates of instrumental delivery (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.19), meconium‐stained liquor (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.08); Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.11) and postpartum haemorrhage (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.81) were similar between the two groups. Neonatal intensive care unit admissions were reduced in the oxytocin group (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.92); however there were high levels of heterogeneity for this outcome (I2 = 70%), and when the analysis was repeated using a random‐effects model the difference between groups was not significant (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.27).

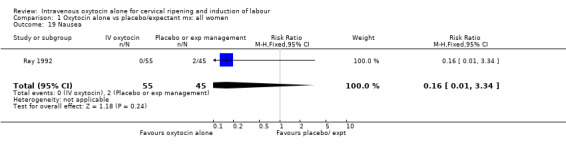

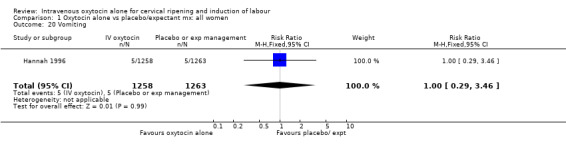

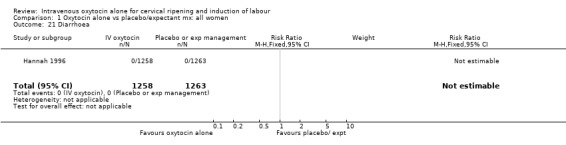

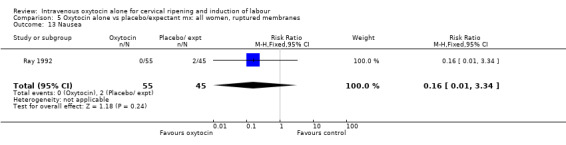

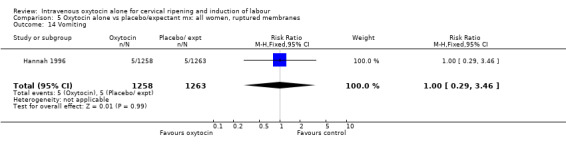

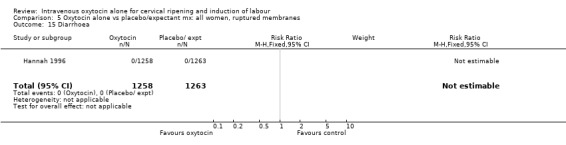

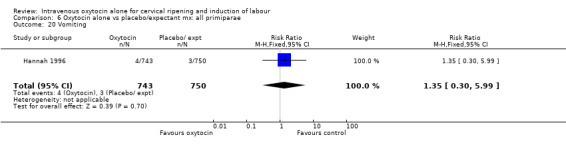

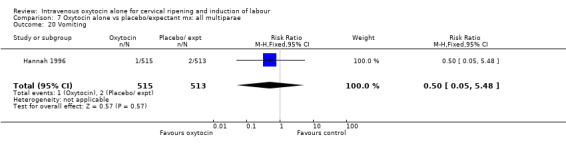

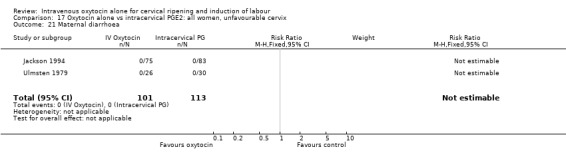

Only single trials measured nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea showing no differences between groups for these symptoms.

Hannah 1996 reported that women were less likely to be dissatisfied with induction compared with expectant management (5.9% versus 13.7%, RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.56).

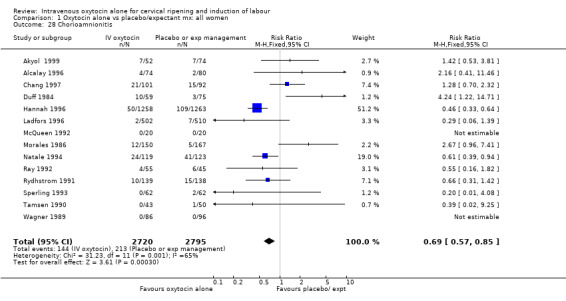

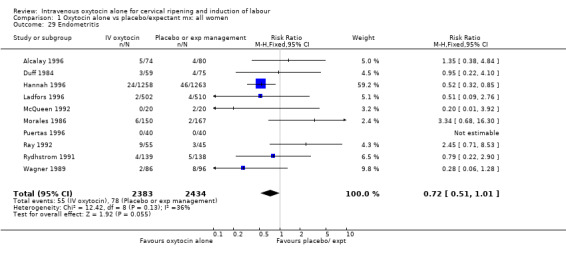

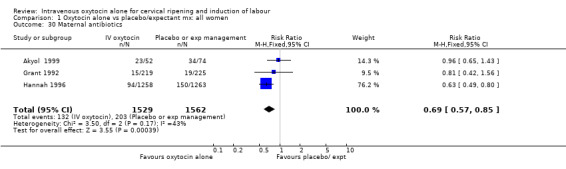

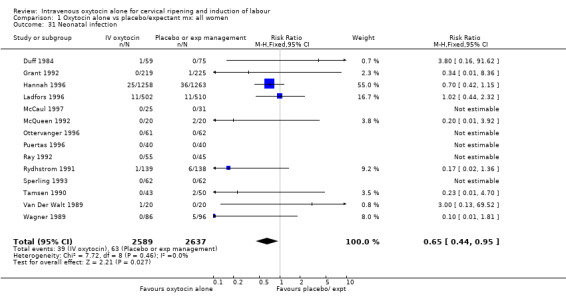

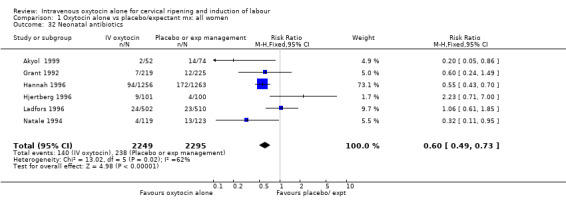

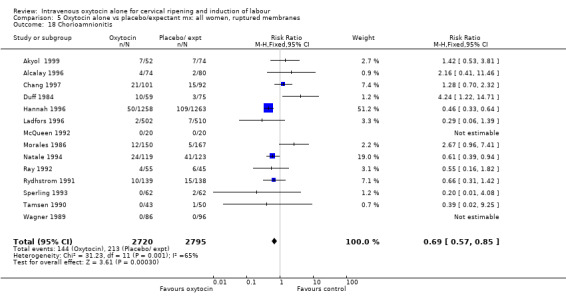

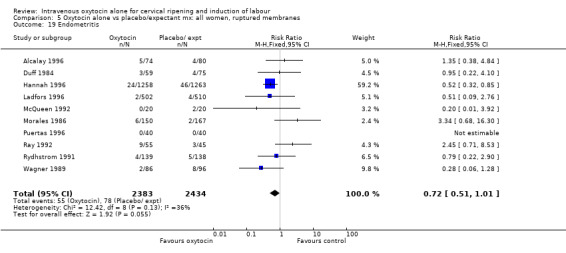

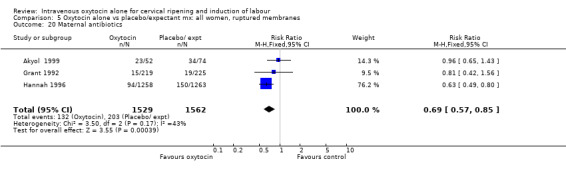

Non‐prespecified outcomes

Rates of chorioamnionitis were reduced in the oxytocin group (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.85) but between‐study heterogeneity for this outcome was high (I2 = 65%). When we repeated the analysis using a random‐effects model the difference between groups was no longer significant (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.39). Rates of endometritis appeared to be similar in the two groups (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.01). Women in the oxytocin group were less likely to receive antibiotics (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.85).

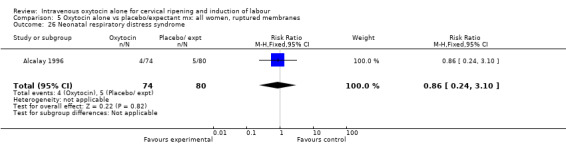

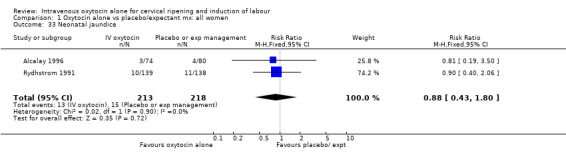

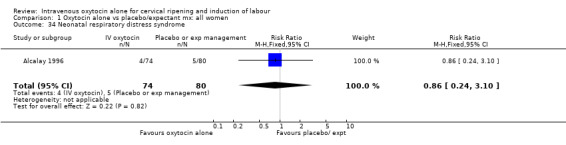

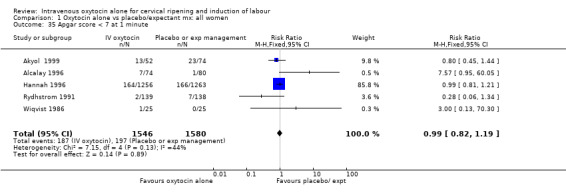

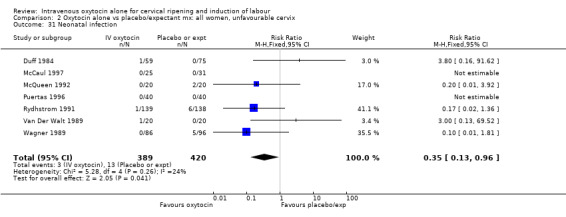

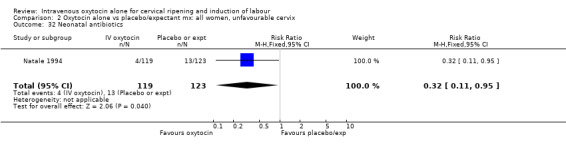

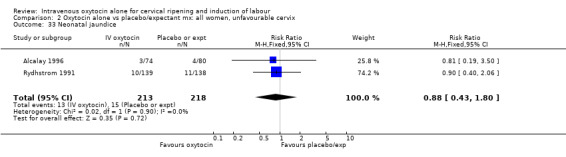

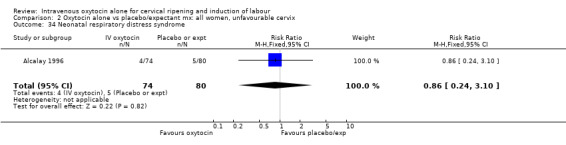

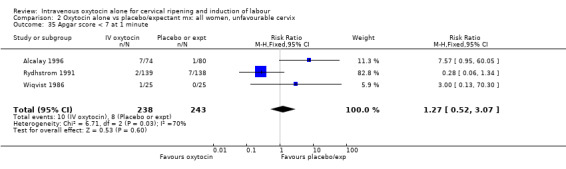

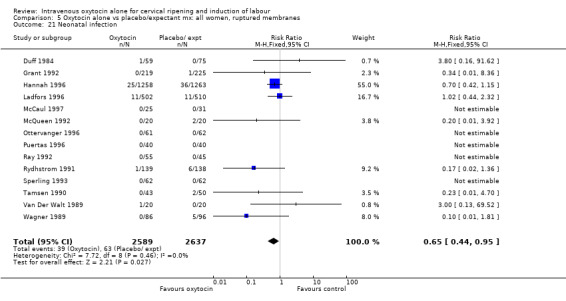

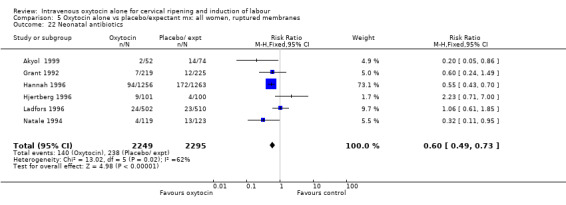

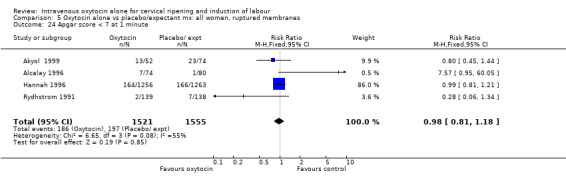

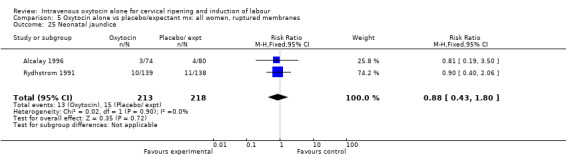

Neonatal infection (measured in 14 trials including 5226 women) was lower with oxytocin induction compared with a policy of expectant management (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.73). In view of high levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 62%) we repeated the analysis using a random effects model; the difference between groups remained statistically significant (1.5% versus 2.4%, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.95). The use of neonatal antibiotics was slightly less in the oxytocin group, but evidence did not reach statistical significance (6.2% versus 10.4%, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.07). There was no evidence of a difference between groups for rates of neonatal jaundice, respiratory distress syndrome or Apgar score less than seven at one minute.

Subgroup analysis

Where data were available, we compared overall results with those for women with either favourable or unfavourable cervix, when membranes were intact or ruptured; for nulliparous and multiparous women; and for women who had had a previous caesarean section or not (Analysis 2.1 to Analysis 8.3). More detailed analysis was carried out looking at women with different characteristics within these major subgroups, e.g. primiparous women with intact membranes. These analyses are available from the contact author.

2.1. Analysis.

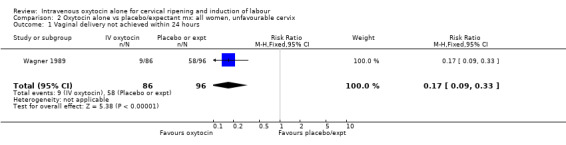

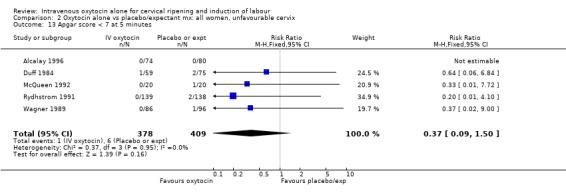

Comparison 2 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

8.3. Analysis.

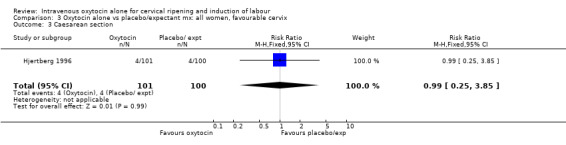

Comparison 8 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx : all women, previous CS, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

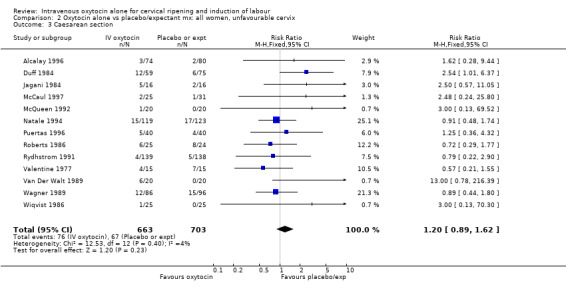

(1) Cervix favourable or unfavourable

For primary outcomes, findings were almost identical for all women as compared with those women recruited to studies where an unfavourable cervix was an inclusion criterion (Analysis 2.1 to Analysis 2.5). For example, for all women (24 studies with 6620 women) the RR for caesarean section was 1.17 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.35) where the cervix was unfavourable (13 studies, 1366 women) the RR was 1.20 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.62).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

Only two studies contributed data to the analyses for women where the cervix was favourable. Overlap between the confidence intervals of findings for this group compared with the findings relating to all women or unfavourable cervix demonstrated that there did not appear to be important differences between groups (Analysis 3.3 to Analysis 3.32).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

3.32. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 32 Neonatal antibiotics.

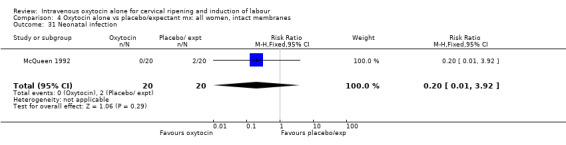

(2) Ruptured or intact membranes

Most of the studies comparing the use of oxytocin with expectant management specifically recruited women with ruptured membranes (i.e. 20 of the 25 studies reported outcomes for women with ruptured membranes). Thus, for all primary outcomes, and for most other outcomes, the results for women with ruptured membranes were the same as, or very similar to, findings for all women (Analysis 5.1 to Analysis 5.26). For women with intact membranes, there were no significant findings, which was not surprising, given that for most outcomes only one or two (relatively small) studies contributed data (Analysis 4.1 to Analysis 4.31).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, ruptured membranes, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

5.26. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, ruptured membranes, Outcome 26 Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.

4.1. Analysis.

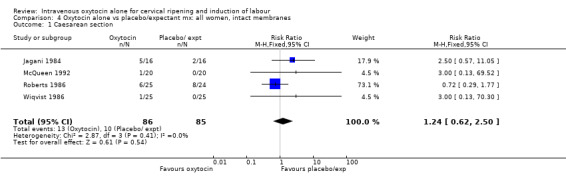

Comparison 4 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, intact membranes, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

4.31. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, intact membranes, Outcome 31 Neonatal infection.

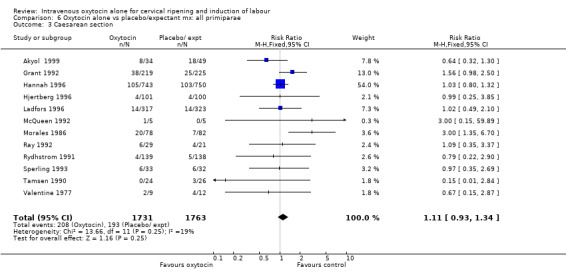

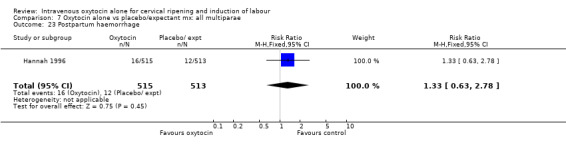

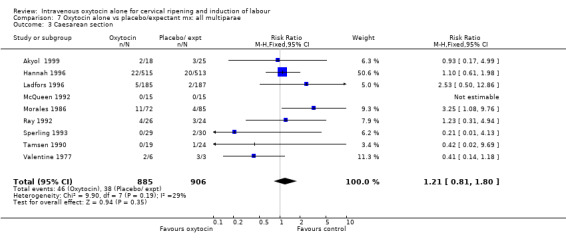

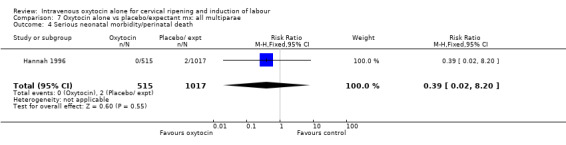

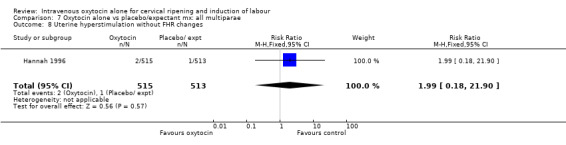

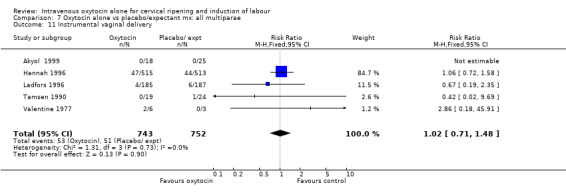

(3) Nulliparity or multiparity

There was no evidence of any differences in the treatment effect for nulliparous compared with multiparous women. For most outcomes results were similar, with considerable overlap between confidence intervals (seeAnalysis 6.3 to Analysis 7.23).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

7.23. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all multiparae, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

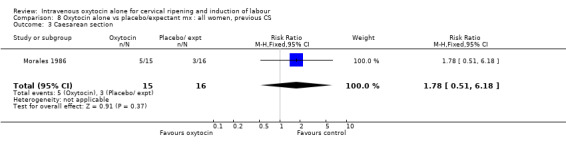

(4) Previous caesarean section

Only one small study (Morales 1986) provided data on women that had had a previous caesarean section. This study provided information on women having another caesarean section in the index pregnancy. Results were not significant.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis whereby studies were grouped according to study quality (using allocation concealment as the measure of quality). Results are set out in Additional tables: Table 24. The sensitivity analyses did not affect the general pattern of findings; findings were the same, or similar for all women and in trials with adequate or uncertain, or inadequate allocation concealment.

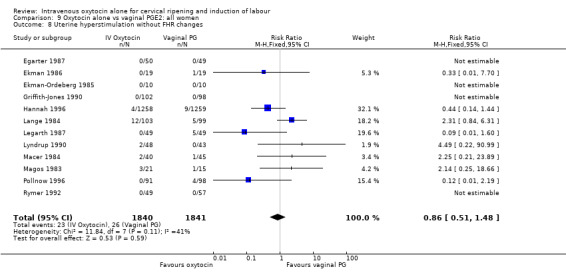

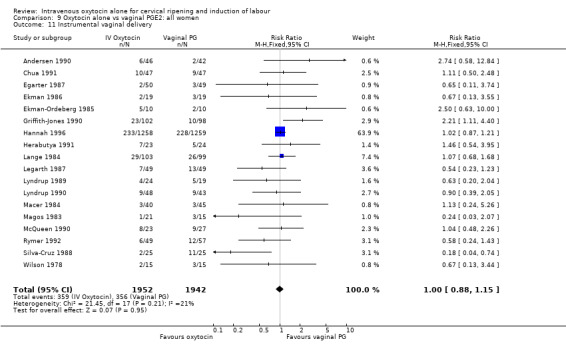

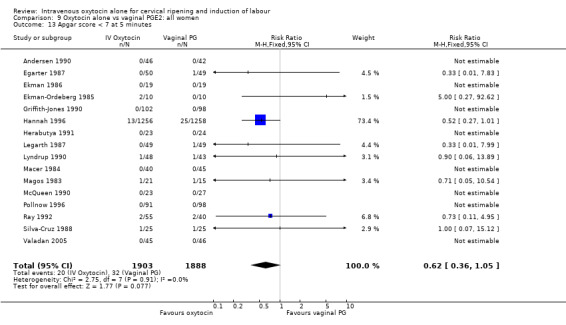

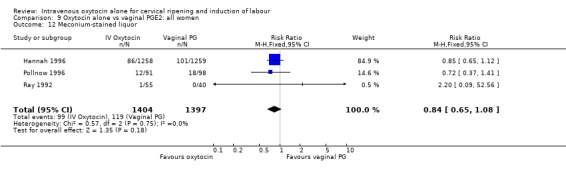

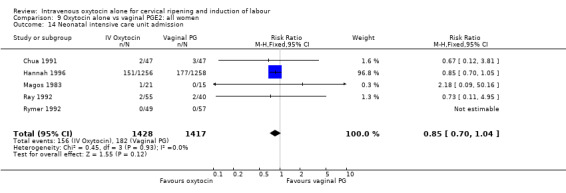

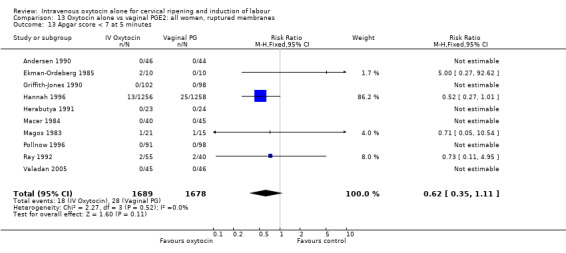

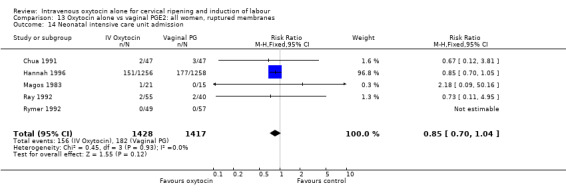

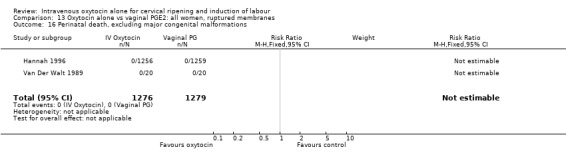

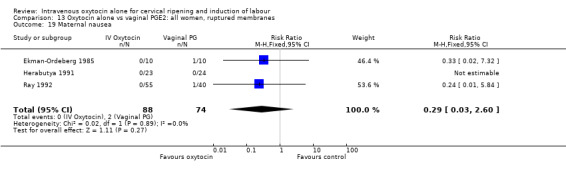

Intravenous oxytocin alone versus vaginal prostaglandins (27 trials; 4564 women)

Primary outcomes

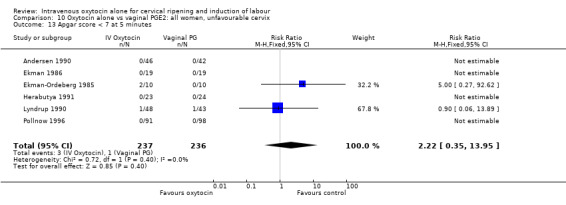

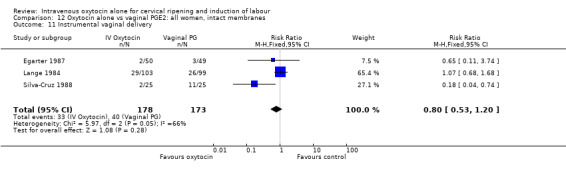

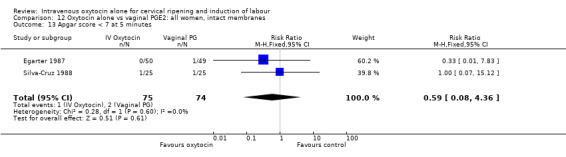

When compared with vaginal PGE2, oxytocin was associated with more failures to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours (70% versus 21%, RR 3.33, 95% CI 1.61 to 6.89). Two trials including 58 women reported this outcome.

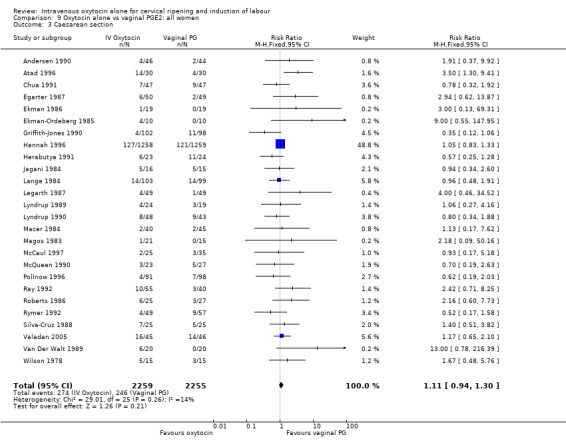

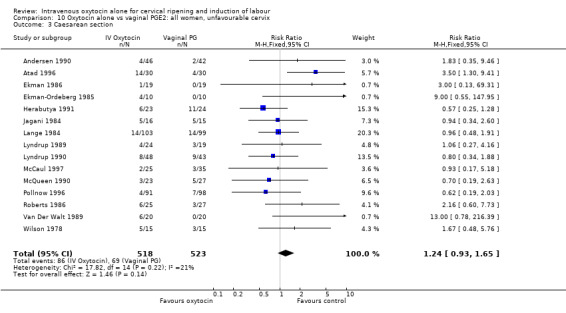

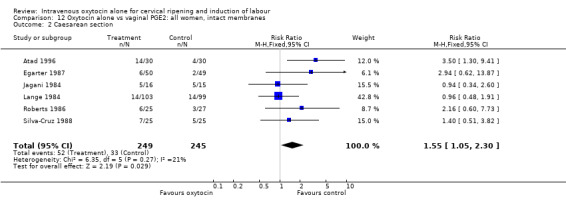

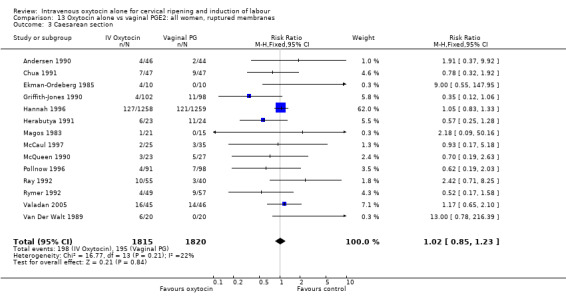

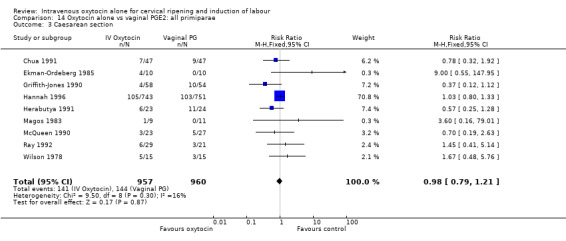

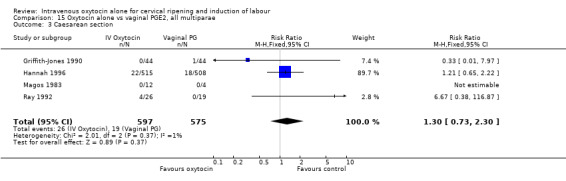

There was no significant difference in caesarean section rates for women receiving oxytocin compared with vaginal PGE2 (12.1% versus 10.9%, RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.30). Twenty‐six trials including 4514 women measured this outcome.

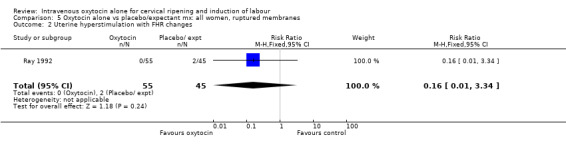

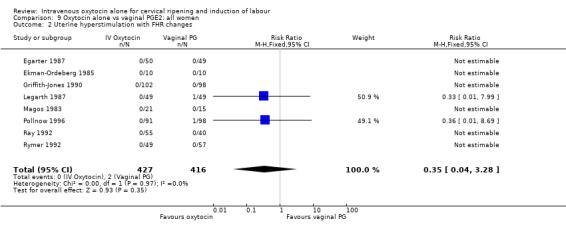

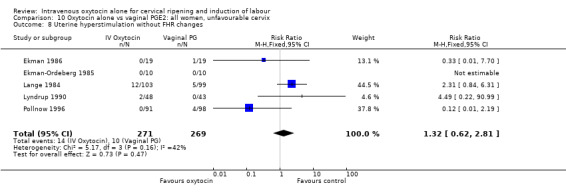

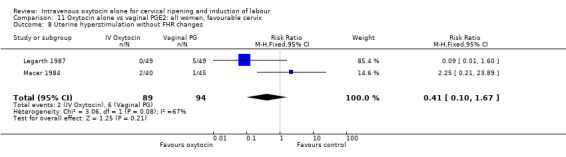

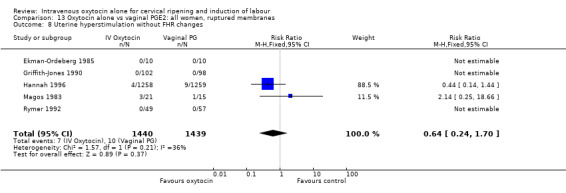

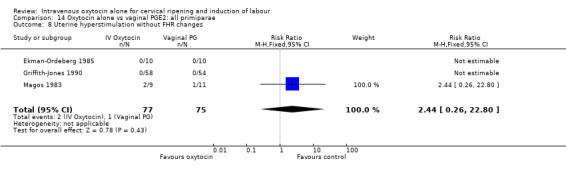

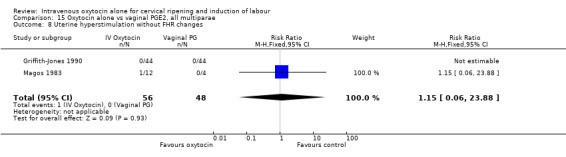

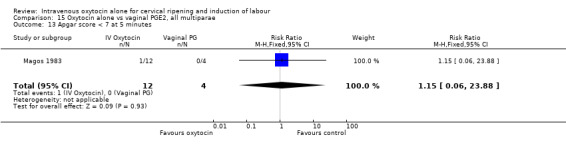

The incidence of uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes was very low, with only two women of the 843 included in trials experiencing this outcome (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.28).

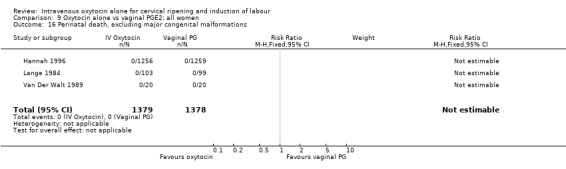

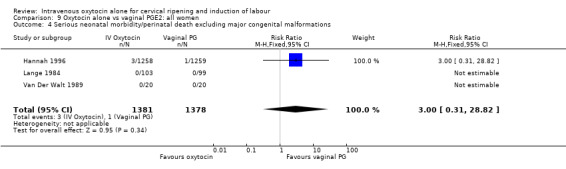

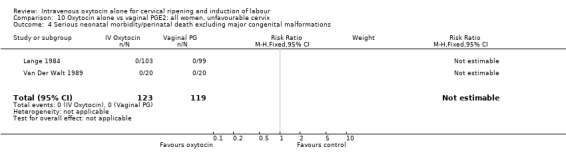

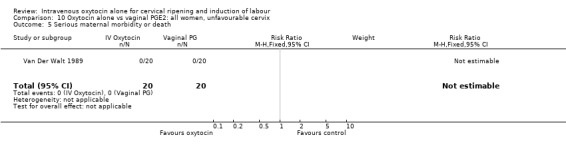

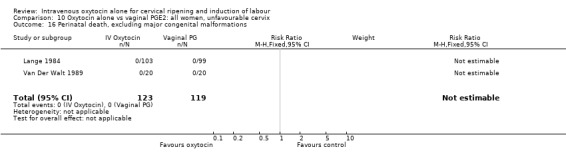

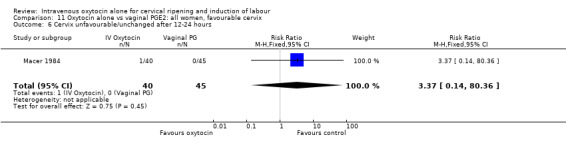

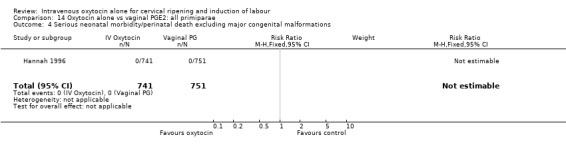

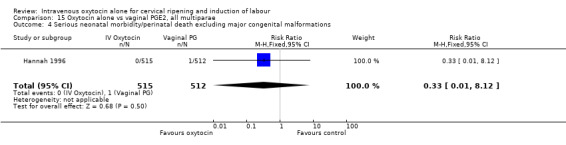

There were insufficient data to derive any meaningful conclusions regarding neonatal and maternal mortality or morbidity, with only four cases of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death reported in the 2759 included patients (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.31 to 28.82) and one case of maternal mortality or serious morbidity (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.02 to 8.93).

Secondary outcomes

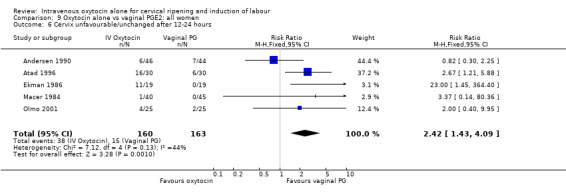

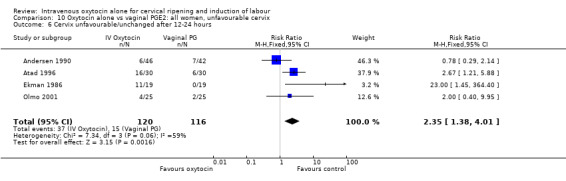

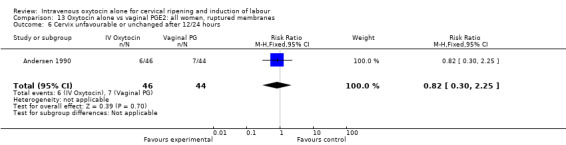

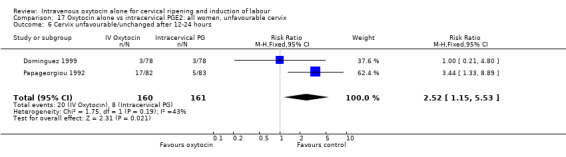

Compared with vaginal PGE2, oxytocin was more likely to result in unfavourable or unchanged cervix at 12 to 24 hours (23.8% versus 9.2%, RR 2.42, 95% CI 1.43 to 4.09).

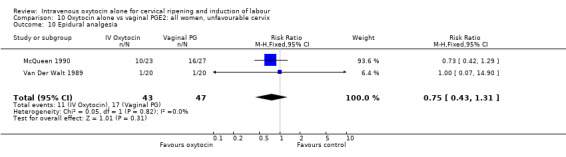

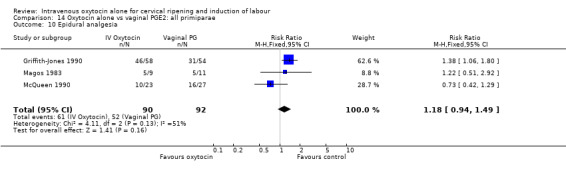

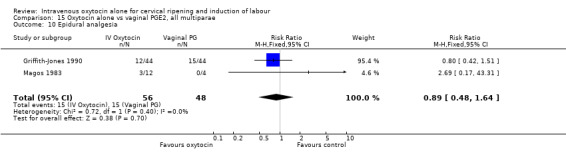

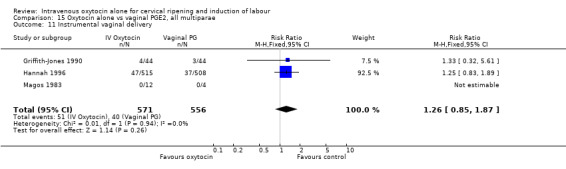

The use of epidural analgesia was measured in six trials (2949 women) and was increased in the oxytocin group compared with vaginal PGE2 (52.8% versus 48.4%, RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.17).

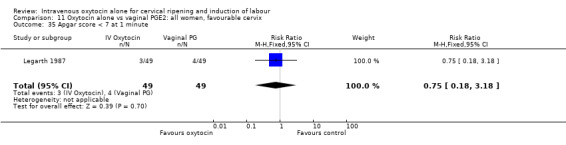

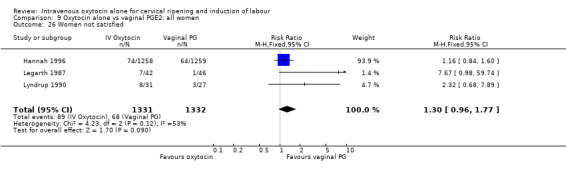

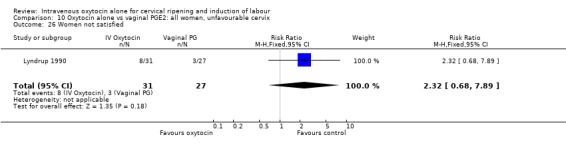

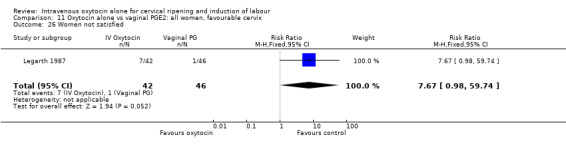

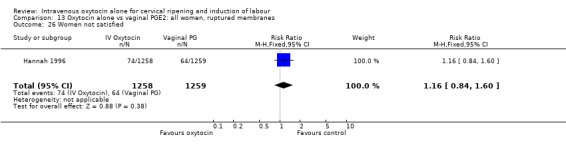

Maternal satisfaction was examined in three trials including 2663 women. While oxytocin was perceived less favourably, there was no significant difference between groups when dissatisfaction with the induction process was measured by post‐delivery questionnaires (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.77). (In the studies by Legarth 1987 and Lyndrup 1989, women were asked whether the induction process was to be recommended, was acceptable or was unsatisfactory; in the analysis the numbers describing the process as unsatisfactory are set out. In the study by Hannah 1996, the numbers are recorded for women who said there was nothing they liked about the process of induction.)

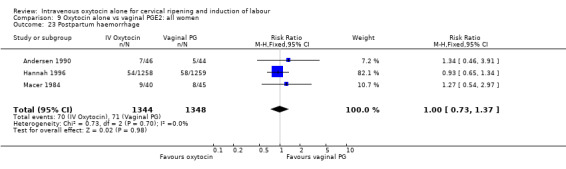

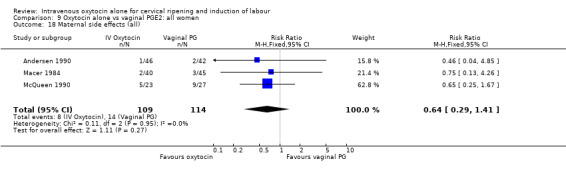

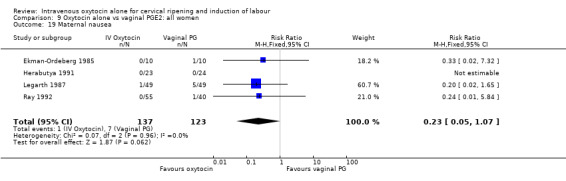

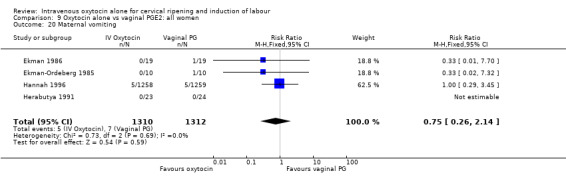

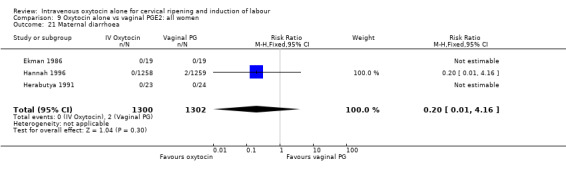

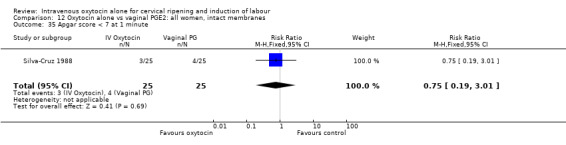

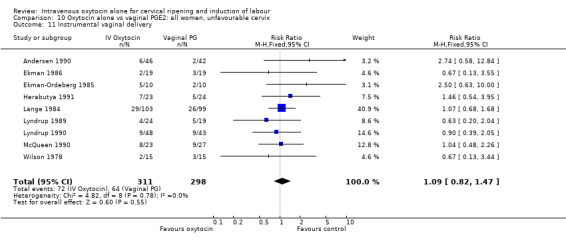

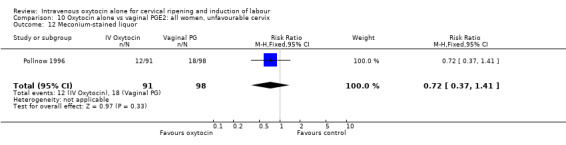

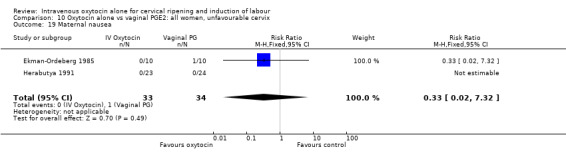

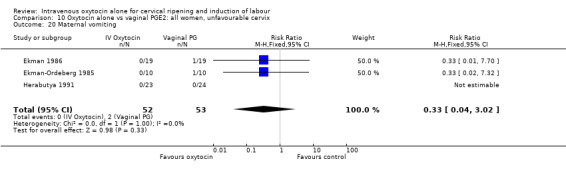

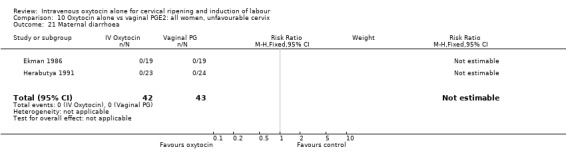

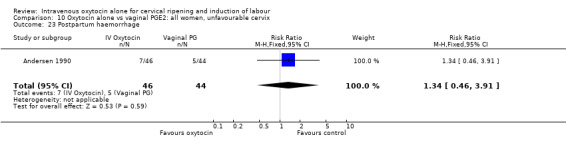

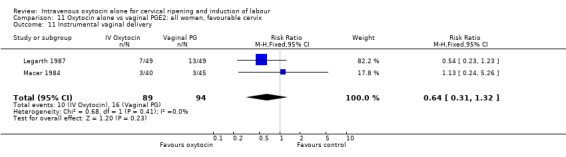

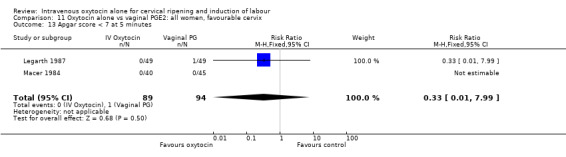

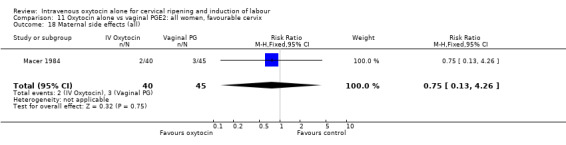

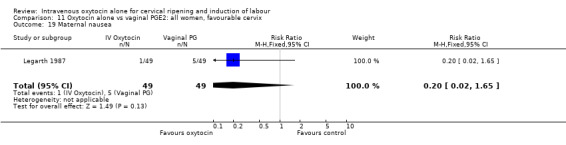

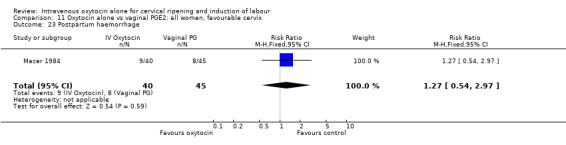

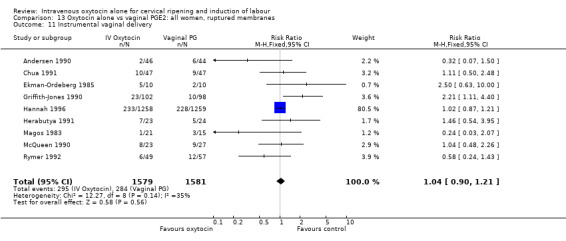

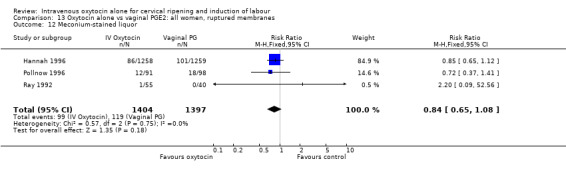

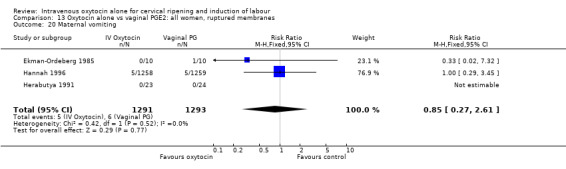

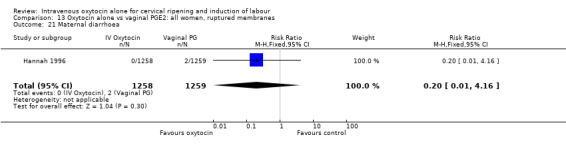

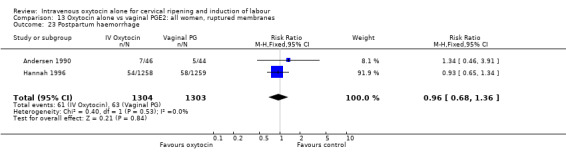

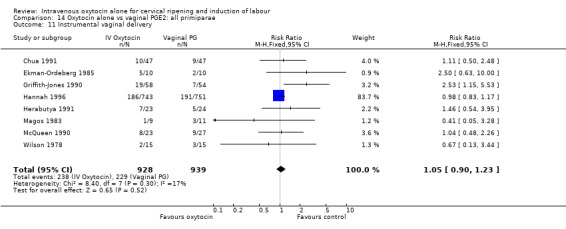

There was no significant evidence of differences between groups for uterine hyperstimulation (Analysis 9.8), rates of instrumental delivery (Analysis 9.11), low Apgar score at five minutes (Analysis 9.13), meconium staining (Analysis 9.12), neonatal intensive care admission (Analysis 9.14), perinatal death (Analysis 9.16), or postpartum haemorrhage (Analysis 9.23). There were similar rates of maternal side effects in the two groups (Analysis 9.18; Analysis 9.19; Analysis 9.20; Analysis 9.21).

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

9.11. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

9.13. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

9.12. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

9.14. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

9.16. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death, excluding major congenital malformations.

9.23. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

9.18. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 18 Maternal side effects (all).

9.19. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 19 Maternal nausea.

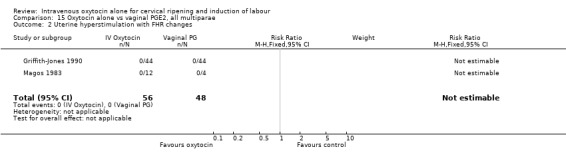

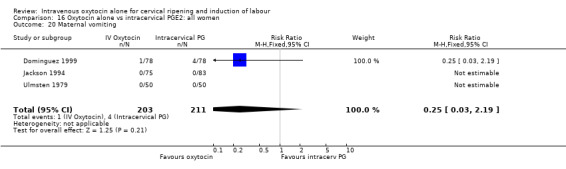

9.20. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 20 Maternal vomiting.

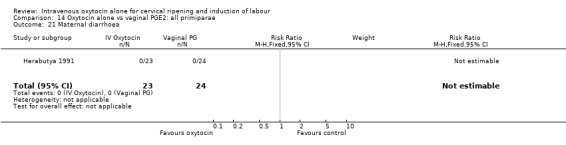

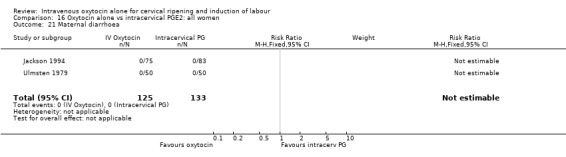

9.21. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 21 Maternal diarrhoea.

Non‐prespecified outcomes

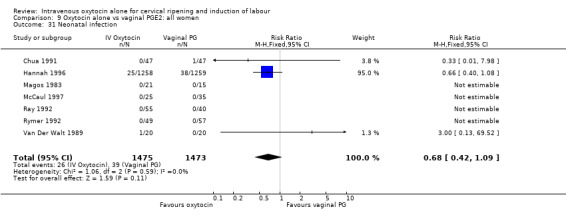

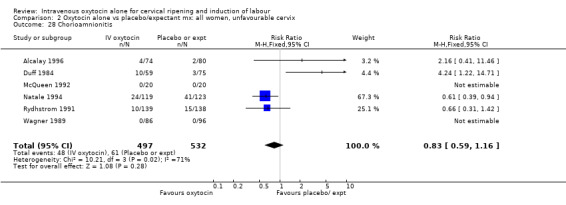

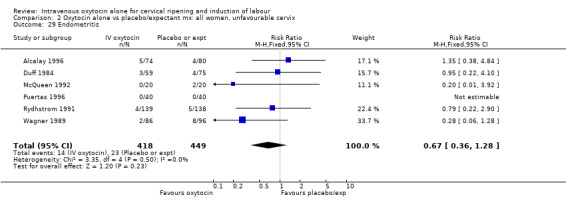

Rates of chorioamnionitis were reported in four trials (2742 women) and were lower when oxytocin was compared with vaginal PGE2 (3.9% versus 6.0%, RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.92). The use of neonatal antibiotics (measured in two studies, 2564 babies) was also lower in the oxytocin group (7.3% versus 10.9%, RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.87). There was no significant evidence that the rates of endometritis (Analysis 9.29), neonatal infection (Analysis 9.31), use of maternal antibiotics (Analysis 9.30), neonatal jaundice (Analysis 9.35), and Apgar scores at one minute less than seven (Analysis 9.33) were different in the two groups.

9.29. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 29 Endometritis.

9.31. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 31 Neonatal infection.

9.30. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 30 Maternal antibiotics.

9.35. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

9.33. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, Outcome 33 Neonatal jaundice.

Subgroup analyses

(1) Cervix favourable or unfavourable

Most studies compared intravenous oxytocin with vaginal PGE2 in women with unfavourable cervix. Not surprisingly, these results were very similar for overall results (Analysis 10.1 to Analysis 10.32).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

10.32. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 32 Neonatal antibiotics.

Only two studies contributed data to the subgroup where the cervix was favourable. Overlap between the confidence intervals of findings for this group compared with the findings relating to all women, or for studies recruiting women where the cervix was unfavourable, suggested that there were no important differences between groups (Analysis 11.1 to Analysis 11.35).

11.35. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

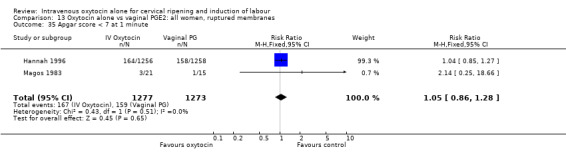

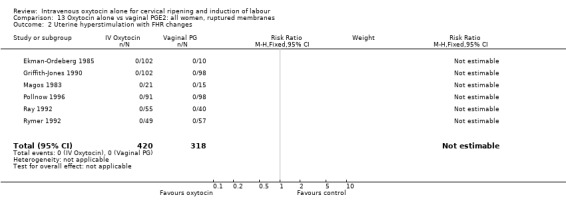

(2) Ruptured or intact membranes

Many of the studies comparing the use of oxytocin with vaginal prostaglandin specifically recruited women with ruptured membranes, and much of the data for both the overall and subgroup analysis were drawn from a large multi‐centre study (Hannah 1996). Again, subgroup analyses for women with ruptured membranes are consistent with overall results (Analysis 13.1 to Analysis 13.35 ). The results for women with intact membranes (six studies contributed data) were also consistent with overall results although these studies reported findings for only a limited number of outcomes (Analysis 12.1 to Analysis 12.35).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, ruptured membranes, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

13.35. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, ruptured membranes, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

12.1. Analysis.

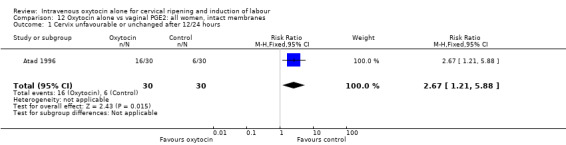

Comparison 12 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, intact membranes, Outcome 1 Cervix unfavourable or unchanged after 12/24 hours.

12.35. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, intact membranes, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

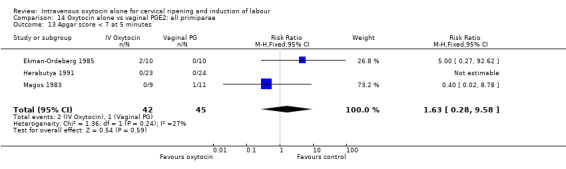

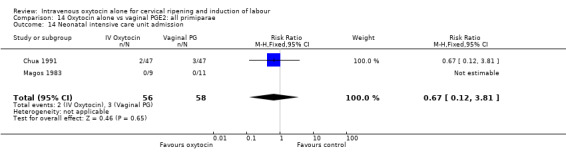

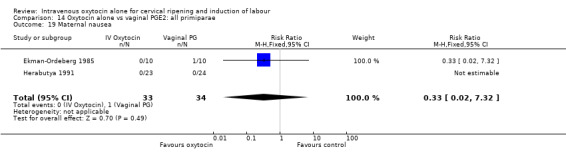

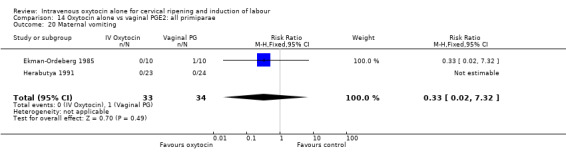

(3) Nulliparity or multiparity

There was no evidence of any differences in the treatment effect for nulliparous compared with multiparous women. (seeAnalysis 14.1 to Analysis 15.23).

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all primiparae, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

(4) Previous caesarean section

No studies provided information on women that had had a previous caesarean section.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis according to study quality (using allocation concealment as the measure of quality). Results are set out in Additional tables: Table 25. For primary outcomes, findings were similar, irrespective of the quality of allocation concealment.

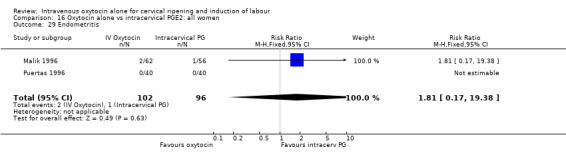

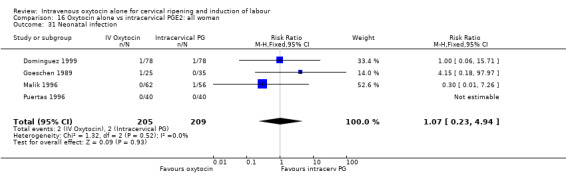

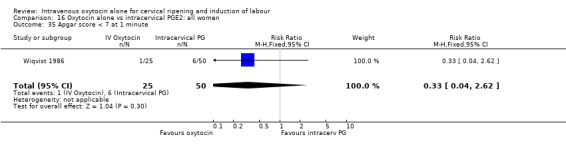

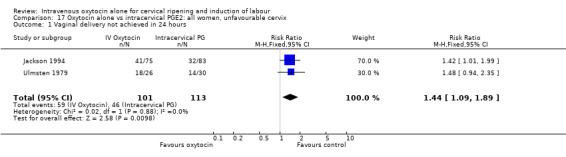

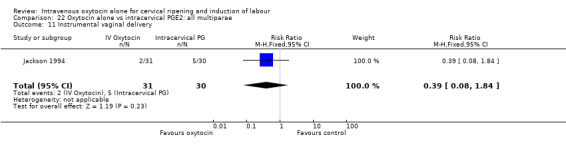

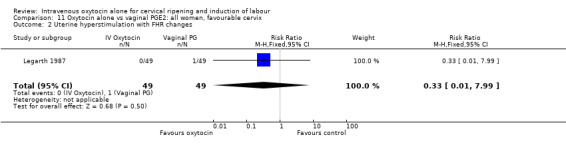

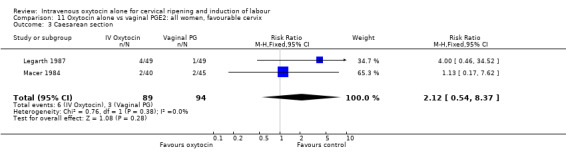

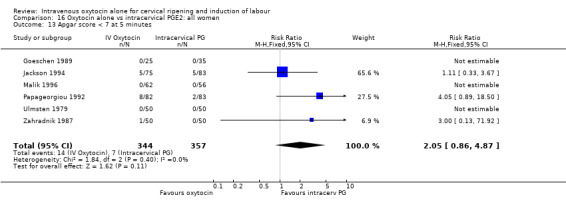

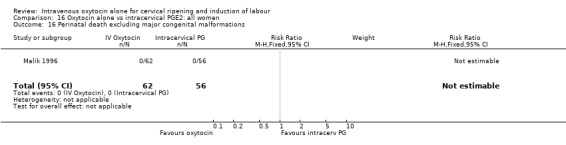

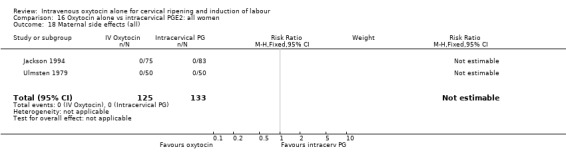

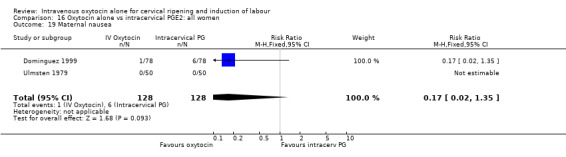

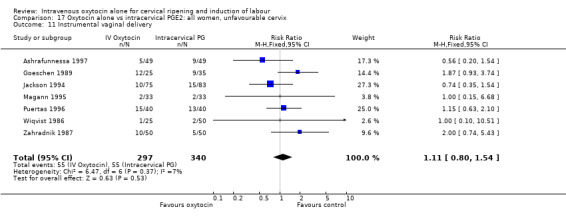

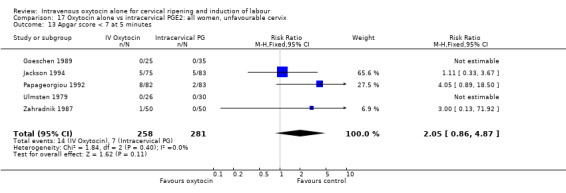

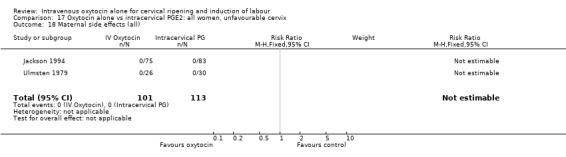

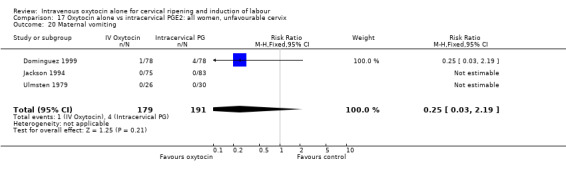

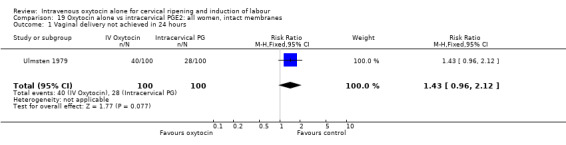

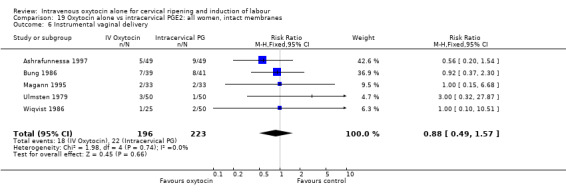

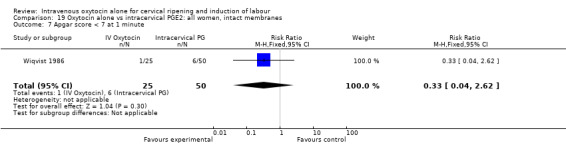

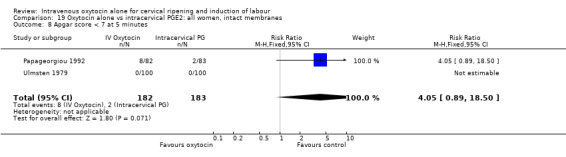

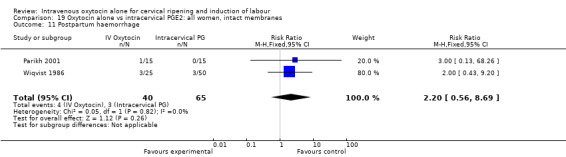

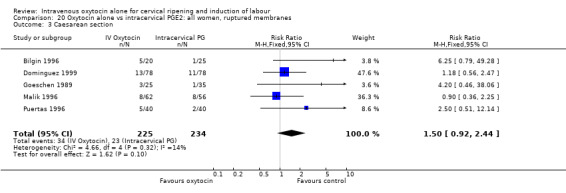

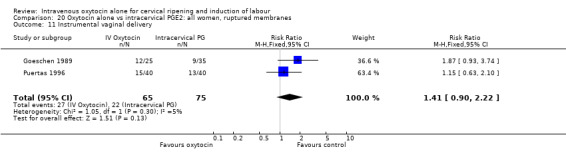

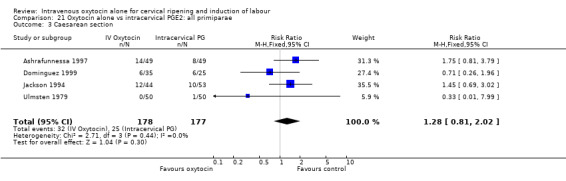

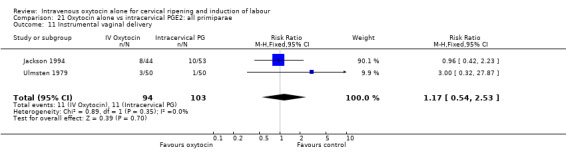

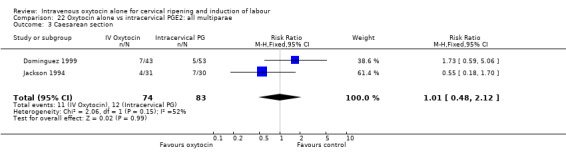

Intravenous oxytocin alone versus intracervical prostaglandins (14 trials; 1331 women)

Primary outcomes

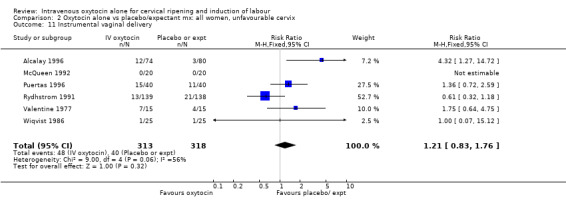

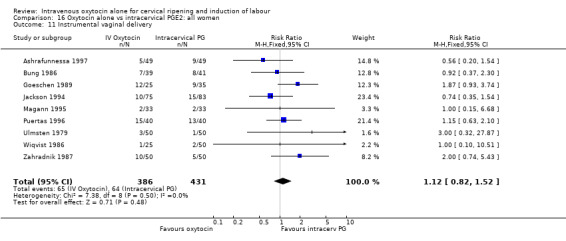

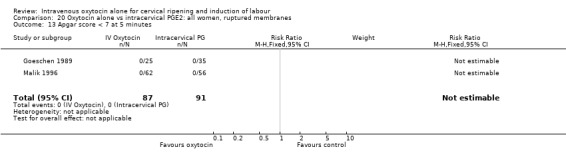

Oxytocin was associated with increased unsuccessful vaginal deliveries within 24 hours when compared with intracervical PGE2 (50.4% versus 34.6%, RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.96); however, only two studies with a total of 258 women reported this outcome. All 14 included studies (including 1331 women) contributed data to the analysis of caesarean section rates. Results favoured intracervical PGE2 with an increased rate of caesarean section in the oxytocin group (19.1% versus 13.7%, RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.74).

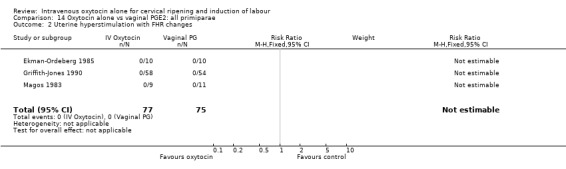

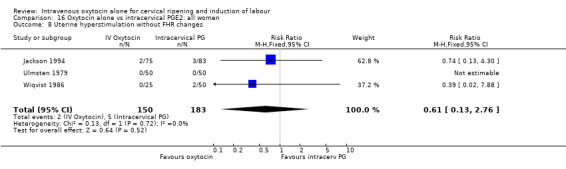

There was no significant difference in uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes in the two trials reporting this outcome (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.38 to 10.75).

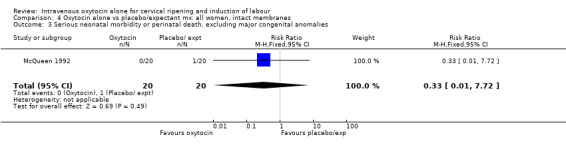

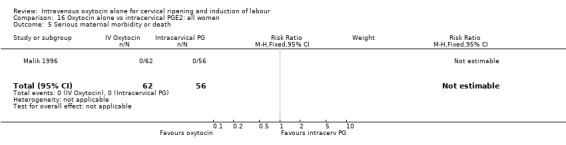

There were insufficient data to derive any meaningful conclusions regarding neonatal and maternal mortality/morbidity. One trial specifically reported on maternal mortality with no cases reported in the 118 participants.

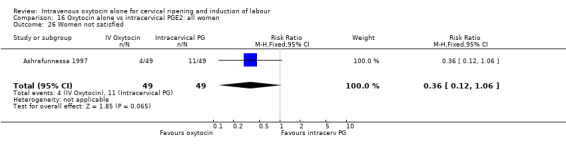

Secondary outcomes

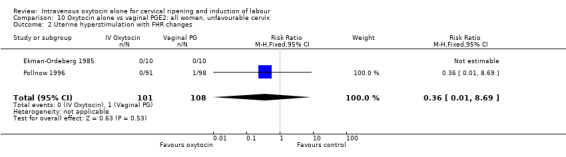

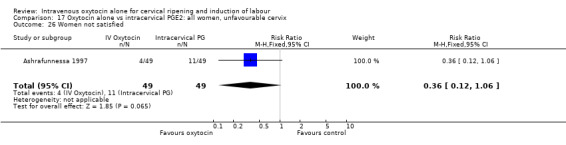

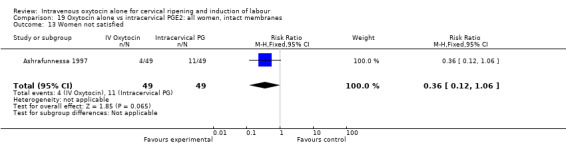

Only one study (including 98 women) reported maternal satisfaction (Ashrafunnessa 1997). Women in the oxytocin groups were less dissatisfied, but the evidence of a difference between groups was not statistically significant (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.06).

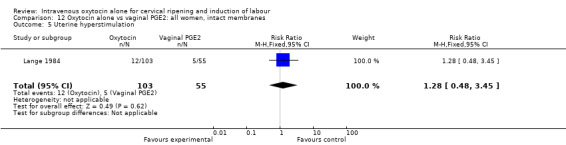

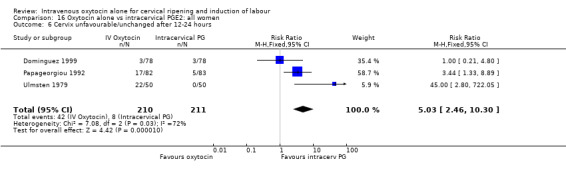

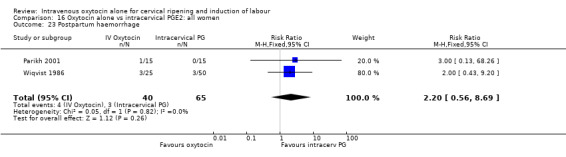

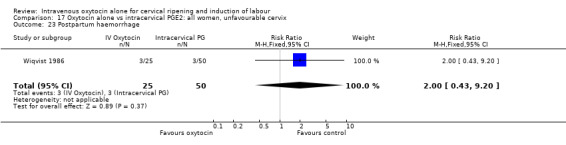

There were no significant differences between groups for other prespecified secondary outcomes including uterine hyperstimulation, instrumental delivery rates, postpartum haemorrhage, maternal side effects or neonatal outcomes. Women in the oxytocin group were more likely to have an unfavourable cervix after 12‐24 hours compared with those receiving PGE2 (RR 5.03, 95% CI 2.46 to 10.30); however, the level of heterogeneity was high for this outcome (I2 = 72%). When we repeated the analysis using a random‐effects model, the difference between groups was not significant (RR 3.94, 95% CI 0.67 to 23.15).

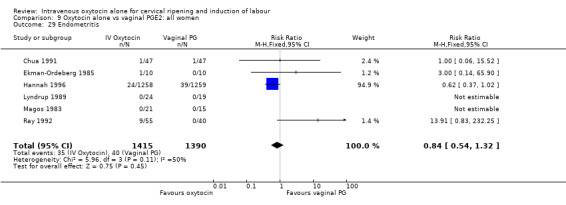

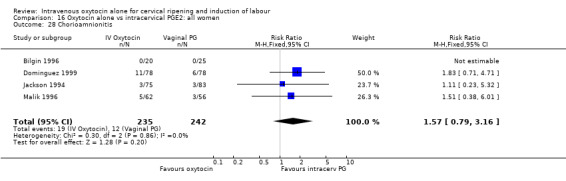

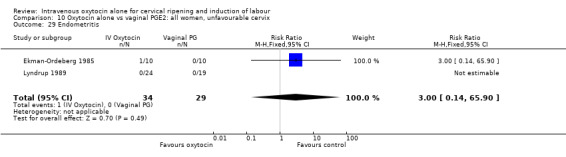

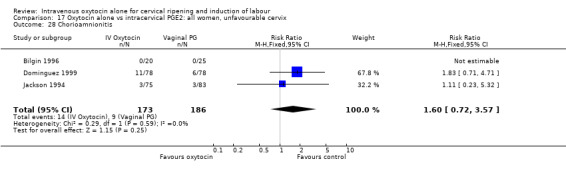

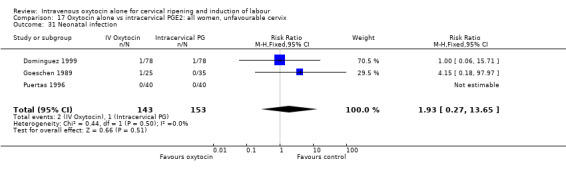

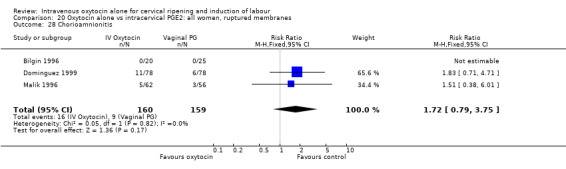

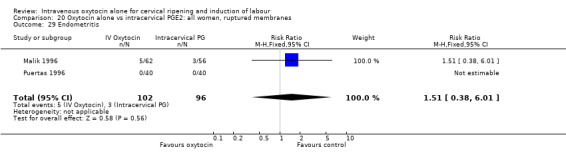

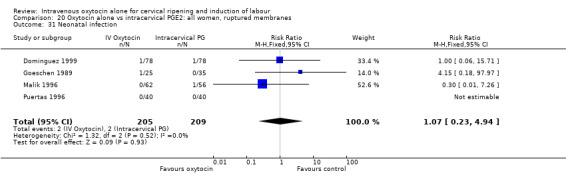

Non‐prespecified outcomes

There were no significant differences in the rates of chorioamnionitis, endometritis, neonatal infection or Apgar scores less than seven at one minute between the two groups (Analysis 16.28; Analysis 16.29; Analysis 16.31; Analysis 16.35).

16.28. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, Outcome 28 Chorioamnionitis.

16.29. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, Outcome 29 Endometritis.

16.31. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, Outcome 31 Neonatal infection.

16.35. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

Subgroup analysis

(1) Cervix favourable or unfavourable

Most of the studies included women with low Bishop scores. For both primary outcomes and most other outcomes findings for those women where the cervix was unfavourable were the same as, or similar to, those for all women (Analysis 17.1 to Analysis 17.35).

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

17.35. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

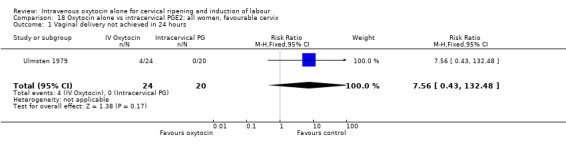

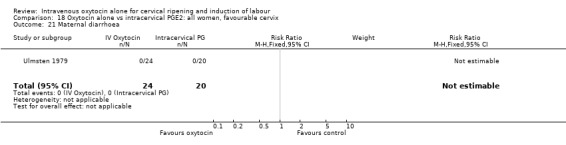

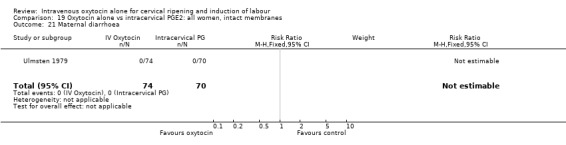

Only one small study contributed data to the analyses for women where the cervix was favourable (Ulmsten 1979) and for most outcomes findings were not estimable (Analysis 18.1 to Analysis 18.21).

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

18.21. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 21 Maternal diarrhoea.

(2) Ruptured or intact membranes

Similar numbers of studies comparing the use of oxytocin with intracervical prostaglandin recruited women with ruptured and intact membranes. The results for both subgroups are entirely consistent with each other, and with overall results.

(3) Nulliparity or multiparity

There was no evidence of any differences in the treatment effect for nulliparous compared with multiparous women, although there were limited data available for these analyses (Analysis 21.1 to Analysis 22.11).

21.1. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all primiparae, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

22.11. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Oxytocin alone vs intracervical PGE2: all multiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

(4) Previous caesarean section

No studies provided information on women that had had a previous caesarean section.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis according to study quality (using allocation concealment as the measure of quality). Results are set out in Additional tables: Table 26. For primary outcomes, findings were the same, or similar irrespective of the quality of allocation concealment.

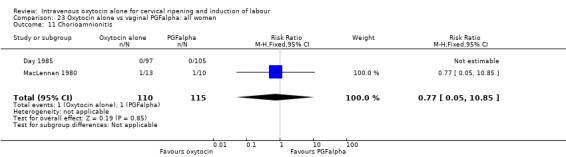

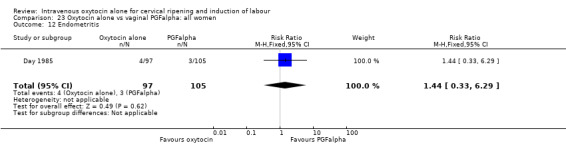

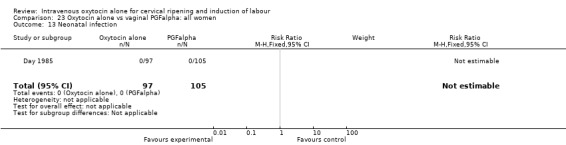

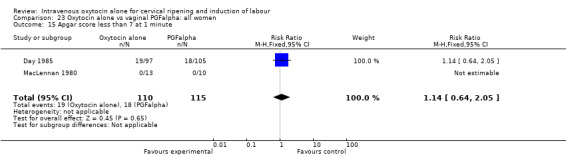

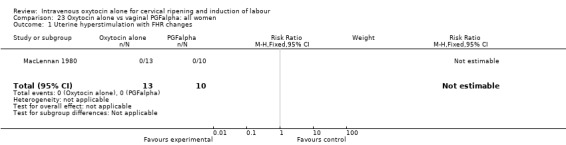

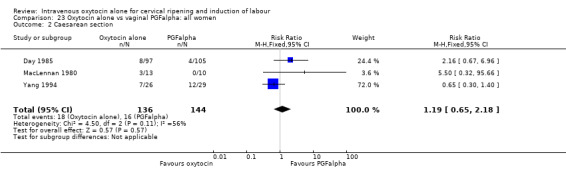

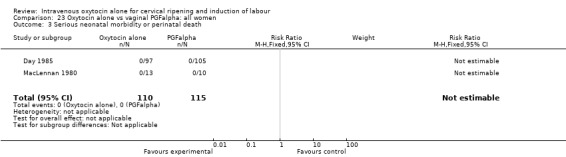

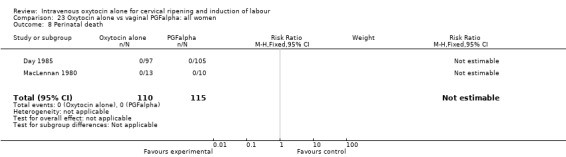

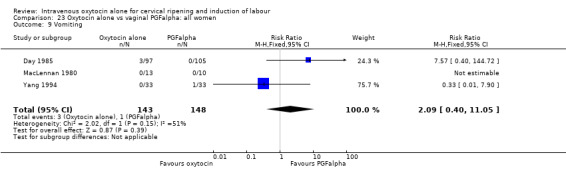

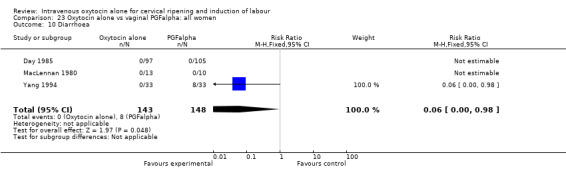

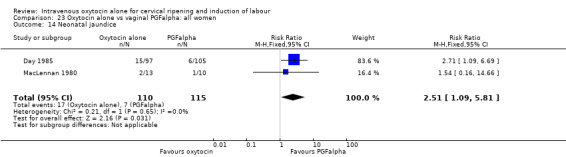

Intravenous oxytocin alone versus vaginal PGF alpha (3 studies; 291 women)

Only three studies contributed data to comparisons in this section (Day 1985; MacLennan 1980; Yang 1994) and for several outcomes only one or two studies provided data.

Primary outcomes

None of the included studies provided information on the number of women failing to deliver vaginally within 24 hours. One study (including 23 women) reported that no women in either group had uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes. All three studies included information on the mode of delivery with no apparent differences between groups for the numbers of women having caesarean section (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.18). There were no cases of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal deaths in the two studies that reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

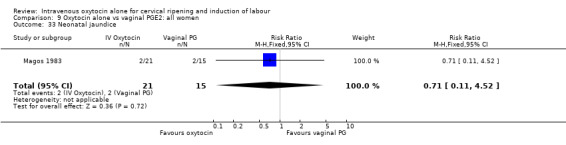

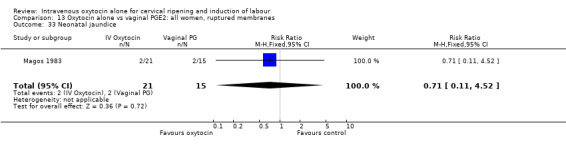

There was no evidence of differences between groups for most secondary outcomes. Women in the oxytocin group were more likely to have epidural analgesia in the two studies that reported this outcome (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.03). There was also more neonatal jaundice recorded for babies in the oxytocin group (RR 2.51, 95% CI 1.09 to 5.81).

Non‐prespecified outcomes

There was no evidence of differences in the rates of chorioamnionitis, endometritis, neonatal infection or Apgar scores less than seven at one minute between the two groups (Analysis 23.11; Analysis 23.12; Analysis 23.13; Analysis 23.15).

23.11. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGFalpha: all women, Outcome 11 Chorioamnionitis.

23.12. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGFalpha: all women, Outcome 12 Endometritis.

23.13. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGFalpha: all women, Outcome 13 Neonatal infection.

23.15. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGFalpha: all women, Outcome 15 Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Intravenous oxytocin is an effective method for labour induction. Compared with a policy of expectant management, intravenous oxytocin reduces the number of women who remain undelivered 24 hours after randomisation, but active management with oxytocin will result in more caesarean sections and epidurals. Oxytocin induction appears quite safe with very few reports of serious adverse effects.

Most trials comparing intravenous oxytocin with expectant management recruited women with ruptured membranes. Active management with oxytocin was associated with less neonatal infection. The benefits for mother were less clear. There was very little information on maternal satisfaction, although one large study suggested that women were more satisfied with oxytocin induction compared with expectant management.

Intravenous oxytocin was compared with two different type of prostaglandins (PGE2 and PGF), administered either vaginally or intracervically, in various clinical scenarios. The results suggest that prostaglandins are more effective in achieving delivery within 24 hours. Compared with women receiving vaginal PGE2, women receiving intravenous (IV) oxytocin may be at increased risk of requiring epidural analgesia. Importantly, there were fewer caesarean sections when prostaglandin was used. The reduction did not reach statistical significance when results were pooled from 26 trials of vaginal PGE2, but it did in 14 trials where intracervical PGE2 was used (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.74).

Although both prostaglandins and oxytocin appeared safe with very few serious adverse events reported, vaginal PGE2 was associated with higher infection rates in both mothers and babies. Although statistical significance was reached only for chorioamnionitis and for the use of antibiotics for neonates, all other reported outcomes relating to infection (endometritis, maternal antibiotics, neonatal infection and admission to special care) consistently favoured the oxytocin group. The increased risk of infection did not occur in studies examining intracervical PGE2, but these studies were more likely to recruit women with intact membranes.

It is worth mentioning that outcomes relating to infection were not pre‐specified in the original review protocol and therefore have to be interpreted with some caution. We have now added the infection‐related outcomes to our generic protocol (Hofmeyr 2009) and will endeavour to present these data for all new studies included in future updates.

Interpreting the results from the review

There was considerable variability between studies in the treatment protocols for women in the oxytocin groups. There were differences in when treatment started, the dose of oxytocin administered and the duration of treatment. While several trials described treatment beginning immediately after premature rupture of membrane (PROM), in some trials oxytocin was delayed for between six and 24 hours. In the trials published since 1995, the initial dose of oxytocin ranged from one to 15 mU per minute, with the dosage increasing incrementally between every 15 minutes and an hour, and with the maximum dose ranging between 24 and 60 mU per minute. Some of the trials did not specify the dose; Pollnow 1996 for example, refers to a "standard" oxytocin infusion. This variability complicates the interpretation of results from the review.

Where IV oxytocin was compared with vaginal PGE2, again, there was variation in when treatment commenced and in treatment regimes. The most common dose of vaginal PGE2 was 3 mg, but this ranged from 1 to 4 mg. Women received between one and three doses, at four to six‐hourly intervals. The total amount of prostaglandin women received ranged between 1 and 9 mg within 24 hours.

The dose of intracervical PGE2 was less varied. Most women received 0.5 mg of PGE2, but the frequency of doses and the time between each dose varied.

Evidence on increased infection rates in mothers and babies where labour was induced with vaginal prostaglandin may not apply to women whose membranes are intact. Results were drawn from trials recruiting women with ruptured membranes: in the 27 studies examining the use of vaginal prostaglandin, women had intact membranes in only six, and these trials did not report on outcomes relating to infection. For all comparisons, in those studies where women had intact membranes, authors generally stated that artifical rupture of membranes occurred when labour was established. With intact membranes, the risk of infection from the induction process may be reduced.

The studies included in the review were published between 1977 and 2001. However, of the 61 included studies only three have been published since 2000; the use of IV oxytocin alone appears to be of decreasing interest to researchers.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The main outcome in the review concerned the effectiveness of the induction agent; that is, whether or not vaginal delivery was achieved within a day. Of the 61 trials included in the review, only seven reported this outcome. Women's views on the induction process were, also, very rarely reported. Few trials provided information on serious maternal morbidity, apart from infection. Although serious adverse events for mothers are rare, it may not be safe for us to assume that if an event was not reported it did not happen. The same applies for outcomes for babies; while admission to special care was frequently noted, other adverse events were not. Admission to special care is a not a good surrogate measure of neonatal morbidity as it encompasses a short admission for minor problems through to very serious illness with lifetime consequences.

We were interested to see if membrane status, parity and cervical status have any bearing on the direction and size of the effects. However, these results have to be interpreted cautiously (Rothwell 2005). For many outcomes, a small number of studies contributed data, and in view of the large number of analyses being carried out, it is likely that statistical significance may occur through chance alone. Our plan was, therefore, only to draw attention to differences between subgroups, and between subgroups and the findings for the overall sample, where there was a clear difference in findings for particular subgroups, and where differences were consistent and plausible. We found no such differences.

Maternal satisfaction and preferences, and the costs of different treatments were rarely reported. If differences in clinical outcomes for different treatment protocols are small, then maternal preferences and costs to families and service providers are important in deciding the best options.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was generally poor. More than half of the included studies gave little information on methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment. Blinding of participants, clinical staff and outcome assessors was rare. It is difficult to interpret results from studies where information on methods is not provided, or there is a high risk of bias.

Potential biases in the review process

The possibility of introducing bias was present at every stage of the reviewing process. We attempted to minimise bias in a number of ways; two review authors carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. Each worked independently. Nevertheless, the process of assessing risk of bias, for example, is not an exact science and includes many personal judgements.

While we attempted to be as inclusive as possible in the search strategy, the literature identified was predominantly written in English and published in North American and European journals. We are also aware that publication bias is a possibility, as the review includes several small studies reporting a number of statistically significant results. Although we did attempt to assess reporting bias, constraints of time meant that this assessment relied on information available in the published trial report and thus, reporting bias was not usually apparent.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The review partly endorses the recommendations of current UK guidelines on induction of labour produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). These guidelines do not recommend the use of IV oxytocin for the induction of labour; rather, vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2) is advocated as the preferred induction agent (NICE 2008). Although our review supports this general recommendation, we would like to introduce a note of caution: there was some evidence that vaginal PGE2 may increase the risk of maternal and neonatal infection compared with induction of labour with oxytocin, particularly in the presence of ruptured membranes.

Earlier guidelines from the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) also recommended PGE2 for women with intact membranes, but suggested that oxytocin was as effective as prostaglandin for women with ruptured membranes (RCOG 2001). The RCOG also recommended that vaginal rather than intracervical preparations are preferred as they are less invasive. This distinction between women at lower and higher risk of infection (intact versus ruptured membranes) may be a useful one in deciding the best means of inducing labour. Unfortunately, in this review we were unable to make any direct comparisons between women with ruptured versus intact membranes.

NICE also recommend the use of PGE2 for women who have had a previous caesarean and require induction of labour, despite earlier guidelines from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology which suggest that prostaglandins increase the risk of uterine rupture in such women (ACOG 2002). There was insufficient evidence from this review on the best means of induction for women who have had a previous caesarean section.

Clinical guidelines from the developed world may not be relevant to developing countries where prostaglandins may not be affordable. Despite guidelines advocating the use of PGE2, there remains a place for oxytocin in some clinical contexts.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

A comparison of oxytocin alone with either intravaginal or intracervical PGE2 suggests that the prostaglandin agents are more likely to result in delivery within 24 hours than oxytocin alone, and are less likely to result in caesarean sections and epidurals. This needs to be set against possible increased risk of infection for both mother and neonates when women with ruptured membranes are induced.

Implications for research.

One of the main difficulties with this review has been the varied and often poor reporting of important clinical outcomes. Future trials should endeavour to report outcomes more consistently and should aim to report these outcomes in important clinical subgroups, e.g. according to parity, membrane status and cervical status. Future trials should also report rates of infection in mothers and babies; these are important outcomes which have been under‐reported in the trials included in the review.

In developing countries, prostaglandin E2 is often not available because of lack of refrigeration and high costs, and intravenous oxytocin remains the main method for labour induction. The delaying of amniotomy during labour seems to be associated with a reduction in vertical transmission of HIV and it is imperative to find the safest induction protocol in these circumstances. There is insufficient information at present to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of oxytocin alone with intact membranes for induction of labour. The same applies for induction of labour in women with previous caesarean section. Future trials should examine these issues.

Further work is also needed to examine how the varying policies of administration of oxytocin affect outcome. The studies should look at how different intervals of commencing oxytocin or increasing the dose of oxytocin affect efficacy, and also how the different initial and maximum doses affect the performance of oxytocin as an induction agent.

Feedback

Sawan, 25 July 2008

Summary

The following comments relate to the previously published version of this review ‐ see Kelly 2001a.

Summary

In the In the comparison ‘Oxytocin alone vs vaginal PGE2: all women, ruptured membranes, unfavourable cervix’, the first outcome of ‘vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours’ (comparison number 27.01) includes three studies. I believe two of these studies were inappropriately included in this analysis (Lange 1984; Mahmood 1995a), however, and have concerns regarding the quality of third (Ekman‐Ordeberg 1985):

Lange 1984

This study did not compare oxytocin with prostaglandin as participants in both arms received oxytocin when indicated. The objective of the study was to compare “the outcome of induction and labor in patients who received prostaglandin pessaries immediately before oxytocin with the outcome in patients who received oxytocin alone”. Women in the first group, which was misleadingly called the ‘prostaglandin group’, received prostaglandin immediately before oxytocin, a practice not currently recommended in the UK.

Women in the ‘prostaglandin group’ had artificial rupture of membranes performed when it was “feasible and safe”; it is not clear from the published report whether participants in the oxytocin group also had their membranes ruptured. This trial only recruited women with intact membranes. In this review it is included in the analyses for ruptured membranes (comparison 27) and for intact membranes (comparison 25).

Data are reported for the number of deliveries within 24 hours, without specifying the mode of delivery such as Caesarean section, instrumental vaginal delivery or spontaneous vaginal delivery. These data are used in the review for the outcome vaginal delivery in 5 different analyses (20.01, 21.01, 22.01, 25.01 and 27.01).

Mahmood 1995

Again, this study did not compare oxytocin with prostaglandin. The authors of the study stated its objective was: “to compare conservative management of pre‐labor spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM) with the use of prostaglandin (PG)”. Oxytocin was used for women in both groups, but only for augmentation of labour, or if they were not in labour within 24 hours. The numbers of women reported as not delivered in this study were those not delivered before the use of oxytocin in both groups.

Therefore, this study should not be included in the review. In fact; this trial is used in over 50 different analyses in the review, including 27.01.

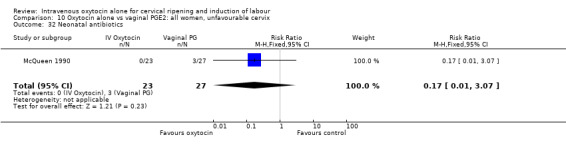

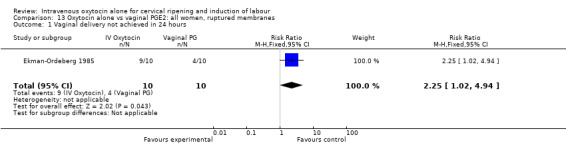

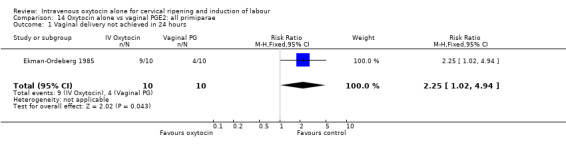

Ekman‐Ordeberg 1985

I have two concerns regarding this small trial with 10 women in each arm.

First, the trial report states in the materials and methods section that “labor induction was not performed until a ‘mean’ of ten hours had passed after rupture of the membranes”. This statement is misleading, as the mean would be calculated sometime later from the collecting data rather than being aimed for at recruitment.

Second, when comparing the number of vaginal deliveries within the first 24 hours the authors reported a p value < 0.01 using Fisher exact test. This is based on one delivery out of 10 in the oxytocin group and 6 deliveries out of 10 in the prostaglandin group. Using the same data I calculate the p value (using Fisher’s exact test, 2‐tailed) as 0.057, which is not statistically significant.

Therefore I have doubts about the scientific value of this study, particularly in the absence of a clear description of the method of randomisation.

Also, in the review the risk ratio of not achieving vaginal delivery within 24 hours in this study is calculated as 2.25, 95% CI 1.02 4.94. Using the same data I calculated the risk ratio of achieving vaginal delivery within 24 hours as 0.17, 95% CI 0.02 ‐ 1.14, which is no longer statistically significant. This is a known statistical phenomenon when using risk ratio for small samples.

Conclusion

Overall I believe that the results obtained from the analyses using these three trials are inaccurate and require re‐evaluation.

Please note that I looked in detail only into one comparison, and subsequently into other analyses which included data from these three studies. Therefore, I can not comment on the rest of this review. However, incidentally I found that another comparison which compares oxytocin with vaginal prostaglandin in all primiparae with ruptured membranes and unfavourable cervix, includes two studies (Jackson 1994 and Ulmsten 1979) that used intracervical, not vaginal, prostaglandin.

(Summary of feedback from Saladin Sawan, June 2008)

Reply

Thanks to Dr Sawan for the helpful feedback.

1. Lange 1984 : As the feedback states, the abstract for this paper suggests that women in the prostaglandin group received PGE2 immediately before oxytocin. However, the abstract is misleading; women did not receive immediate oxytocin in both groups, and in view of the delay in administering oxytocin in the prostaglandin group, this study has been retained in the analysis. (The detailed methods section of the paper states that women in the prostaglandin group received 3mg PGE2 and were encouraged to be mobile; if there was no uterine activity or cervical change further pessaries were inserted after three and then 6 hours after the initial pessary; oxytocin was commenced after a further hour (7 hours after the initial pessary) if labour had not started.)

Women included in the trial had intact membranes at recruitment. We agree that the paper was not clear about whether and when ARM took place. We have removed the study from the analysis relating to women with ruptured membranes. We agree that figures for women delivering within 24 hours may have included women undergoing caesarean section; we have therefore removed data from this study from outcomes on failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours.

2. Mahmood 1995: We re‐assessed the eligibility and now agree with Dr Sawan that this study should not be included in the review, we have moved this study to the excluded studies table and have removed all data relating to this study from the comparisons.

3. Ekman‐Ordeberg 1985: We have retained this study in the analysis as it meets the inclusion criteria of the review. We agree that the lack of detail on study methods causes problems in the interpretation of results. We have added sensitivity analyses to this update showing results for studies with adequate, poor or unclear allocation concealment.

4. We have corrected the mistakes in comparisons including Jackson 1994 and Ulmsten 1979.

5. In view of the errors identified, all data tables were re‐checked as part of the updating process.

Contributors

Z Alfirevic, AJ Kelly and T Dowswell contributed to the response to feedback.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 June 2009 | New search has been performed | Five new trials have been added (Dominguez 1999; Olmo 2001; Parikh 2001; Valadan 2005; Yang 1994). Additional data from new reports of Bilgin 1996 and Puertas 1996 have also been added. Twenty new reports have been excluded. One previously included study (Mahmood 1995) has been excluded in response to feedback. One report is awaiting classification (Perez 1992). The background and methods sections have been revised and the analyses have been modified. We have added sensitivity analyses and new sections describing the results of subgroup analyses. |

| 4 June 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | A new review team prepared the update. Oxytocin appears safe but may increase interventions in labour. PGE2 may increase the chance of vaginal birth within 24 hours. The use of PGE2 in women with ruptured membranes warrants further research. |

| 2 February 2009 | Feedback has been incorporated | We have responded to all of the feedback received. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 June 2008 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback from Saladin Sawan added. |

| 17 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Andrew MacDonald for help with translation of Dominguez 1999 and Maria Tenorio for help with translation of Morgan‐Ortiz 2002.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by four peers (an editor and three referees who are external to the editorial team) and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 3 | 399 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.10, 0.25] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.01, 3.34] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 24 | 6620 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [1.01, 1.35] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death, excluding major congenital anomalies | 10 | 4816 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.26, 1.51] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 2 | 2571 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [0.37, 10.94] |

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 3782 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.03, 16.40] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 10 | 5150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [1.04, 1.17] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 14 | 5275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.94, 1.19] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 3 | 2661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.64, 1.08] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 11 | 4858 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.44, 1.11] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 7 | 4387 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.68, 0.92] |

| 16 Perinatal death, excluding major congenital anomalies | 8 | 4506 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.09, 1.64] |

| 19 Nausea | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.01, 3.34] |

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 2521 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.29, 3.46] |

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 2521 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | 2611 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.85, 1.81] |

| 26 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 2521 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.33, 0.56] |

| 28 Chorioamnionitis | 14 | 5515 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.57, 0.85] |

| 29 Endometritis | 10 | 4817 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.51, 1.01] |

| 30 Maternal antibiotics | 3 | 3091 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.57, 0.85] |

| 31 Neonatal infection | 14 | 5226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.44, 0.95] |

| 32 Neonatal antibiotics | 6 | 4544 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.49, 0.73] |

| 33 Neonatal jaundice | 2 | 431 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.43, 1.80] |

| 34 Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.24, 3.10] |

| 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 5 | 3126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.82, 1.19] |

1.1. Analysis.

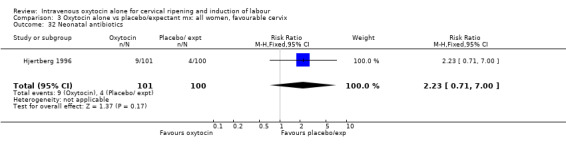

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death, excluding major congenital anomalies.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death, excluding major congenital anomalies.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 19 Nausea.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 26 Woman not satisfied.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 28 Chorioamnionitis.

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 29 Endometritis.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 30 Maternal antibiotics.

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 31 Neonatal infection.

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 32 Neonatal antibiotics.

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 33 Neonatal jaundice.

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 34 Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, Outcome 35 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

Comparison 2. Oxytocin alone vs placebo/expectant mx: all women, unfavourable cervix.