Abstract

Current policy regarding child protection services places increasing demands for providers to engage fathers whose children are involved in the child protection process. This requisite brings to the fore the ongoing challenges that fathers have historically faced in working within these systems. Despite this need, there is little empirical evidence regarding the factors and strategies that impact the engagement of fathers in interventions relevant to child protection services. This comprehensive and systemic review synthesizes the available literature regarding factors and strategies that may foster paternal involvement in the child protection system and their services. We organize the literature concerning paternal engagement in child and family services around an ecological model that examines paternal engagement from individual, family, service provider, program, community, and policy levels. We consider factors and strategies along a continuum of engagement through intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention. This review advances theory by elucidating key factors that foster father engagement. The review also highlights the gaps in the literature and provides strategies for how researchers can address these areas. Future directions in the arenas of practice and policy are discussed.

Keywords: fathers, child protection services, engagement in services, review

1. Introduction

The challenge of engaging families involved with child protective services (CPS) has been documented for years (Crampton, 2007; Levin, 1992; Scourfield, 2006). For parents involved with CPS, not completing treatments that are part of their service plan can result in the removal of their children and loss of parental rights (Dawson & Berry, 2002). Although child welfare history shows an emphasis on serving mothers (O’Donnell, Johnson, D’Aunno, & Thornton, 2005), social science research increasingly highlights the important role of fathers in children’s development (Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley, & Roggman, 2007). In particular, the role of fathers is vital in children’s permanency plans during involvement with CPS. Fathers’ active participation in, and compliance with, the case plan increases the likelihood that children’s foster care will be briefer and that they will reunify with birth families (Coakley, 2008).

One-in-three children in the U.S. live in a home where their biological father is absent and approximately half of all U.S. children will live in a single-parent home before reaching adulthood (Bumpass & Raley 1995; U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). Children living in households without fathers are twice as likely to drop out of school (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993) and children from single-family homes are more likely to be poor. Research shows that approximately 7% of children in married (dual family) households live in poverty, compared to 38% of children in single family households (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). Children raised in single family homes are also at increased risks for substance use, sexual health risks, and school failure (Barrett & Turner, 2006; Rodgers & McGuire, 2009). The challenges described may be exacerbated when these children and involved in the CPS. Attending to the unique ways that fathers can help to blunt the negative consequences of CPS involvement is important and there is a need for interventions to teach these men more appropriate parenting skills that may facilitate the resilience of their children.

The presence of an involved, non-violent father serves a protective function, at times enhancing mothers’ ability to parent (Belsky, Youngblade, & Pensky, 1989; Lee et al., 2009). Involvement by a supportive father reduces the likelihood that mothers will use harsh punitive parenting with a child (Crockenberg, 1987; Guterman et al., 2009) or develop mental health issues (Black et al., 2002) that place children at risk for maltreatment. Even when fathers do not reside with their children, fathers can positively impact their children’s intellectual (Downer, Campos, McWayne, & Gartner, 2008) and social development (Flouri, 2006; Flouri & Buchanan, 2002). This influence occurs directly, via the father–child relationship, and indirectly, via the father’s relationship with the mother and other adults in the child ‘s support network.

The direct and indirect effects of paternal involvement are important to consider because it contributes to both the risks and benefits associated with child outcomes that are being sought by CPS. Fathers who do not participate in their child’s case plan may be out of that child’s life or may be tangentially involved in their lives without CPS’ knowledge. These fathers may also go on to have other children. Promoting healthy parenting behaviors by father may prevent future problems (Marshall, English, & Stewart, 2001). A number of contextual factors can affect paternal involvement and outcomes sought by CPS, including relationship status between the mother and father of the child, history of incarceration, poverty and SES, and other neighborhood factors (Connell, Bergeron, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, 2007; Marbley & Feruguson, 2005). Despite these concerns, the relationship between fathering and child protection has been overlooked in the literature (Brown, Callahan, Strega, Walmsley, & Dominelli, 2009). Consequently, in order to advance theory and empirically-supported treatment with this population, it is essential to document the factors and strategies for engaging fathers in CPS. Thus, this article reviews the literature regarding fathers’ involvement in child and family services. The review uses an ecological framework to organize factors and strategies that have some evidence for engaging fathers, and highlight implications for practice, policy, and further research.

1.1. Immediate need

The CPS system is under federal mandate (42 U.S.C. §1320a-2a; 45 C.F.R. §1355.31) to meet empirically-supported, policy-driven strategies to engage fathers. This mandate creates an urgent need for CPS (Sylvester & Reich, 2002). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, specifically the Children’s Bureau, is charged with conducting systematic assessment and monitoring of states’ child protection programs, known as the Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSR). The outcomes sought by the CFSR, which began in 2001, include the primary goals of children’s safety along with permanency and well being for the family and child (Huber & Grimm, 2004). That is, in addition to protecting children from abuse and neglect, it is recommended that services seek to preserve family relationships and connections, and meet the needs of children and their families (Child and Family Services Reviews Factsheet, nd). To add to the challenge of providing this package of services, there is policy-driven time pressure for case resolution (P.L. 105–89).

The Adoption and Safe Families Act (P.L. 105–89) of 1997 emphasizes immediate planning for children to achieve family stability in a timely manner. ASFA requires permanency hearings for abused and neglected children within a 12-month timeline and includes mandates to file a petition to terminate parental rights once a child has been out-of-home care for 15 of the previous 22 months unless compelling reasons exist to not initiate termination. These mandates place an added burden on CPS to document reasonable efforts to coordinate community services and ensure that parents, including fathers, can access prompt and adequate services (McAlpine, Marshall, & Doran, 2001).

Despite this need for prompt services for the whole family, the historical emphasis on mothers as the target of CPS has been recognized as a programmatic pattern that is difficult to modify (O’Donnell et al., 2005). Ethnographic research has documented that most services are geared toward mothers (Scourfield, 2006). Fathers, even those without a criminal history, tend to be viewed as a threat and scrutinized more than other candidates for placement of the child (O’Donnell et al., 2005). As a result, the two goals of children’s safety and preserving family relationships may initially seem incompatible. In cases where fathers are involved in intimate partner violence (IPV) or child maltreatment, mothers may face a legal charge of failure to protect. This increases the pressure on mothers, while failing to 1) address the problems faced by the family, 2) hold fathers accountable for their actions, and 3) help fathers change their behavior (Scott & Crooks, 2006). Despite the risks involved, there is support for initiatives that focus on fatherhood as an engagement strategy to help men stop their violence (Arean & Davis, 2007). Thus, engaging fathers in services could help meet CPS goals. Providing services to fathers who have perpetrated abuse is key to preventing future abuse and to achieving more positive outcomes for children and families by expanding the resources available to children (Scott & Crooks, 2006). It is important to expand the view of men from a focus on risks to a broader picture that includes how they can be resources for their children in meeting CPS goals (Scourfield, 2006).

In light of the recognized importance and impact of paternal involvement on children’s outcomes and the observed increasing number of children being raised by single mothers (Huebner, Werner, Hartwig, White, & Shewa, 2008), federal initiatives have led states to create programs that seek to actively engage fathers (Bronte-Tinkew, Bowie, & Moore, 2007; Stapleton, 2000). The aims of fatherhood programs are to promote and provide specialized services and outreach to fathers, such as employment services, parent training, and relationship skills training (Sylvester & Reich, 2002). While fatherhood programs have proliferated across the nation and initial evaluations are positive, the data is still preliminary regarding how effective these programs are in engaging fathers to remain involved with their children (Gordon et al., 2012; Sylvester & Reich, 2002). Fatherhood organizations are working hard to document successes, some with the assistance of the National Fatherhood Initiative’s program evaluations (National Father Initiative, 2009).

With the development of the aforementioned policies and programs, there is a growing expectation that family services be more inclusive of men and fathers. It is difficult, however, for child protection agencies to meet this demand (Brown et al., 2009; Huebner et al., 2008). As with any policy-driven transition, distilling the essential components that successfully achieves the call is a necessary first step. Providing child protection agencies with an organized framework of factors and strategies for engaging fathers would begin to build a blue-print that supports their efforts to engage families so that they can benefit from interventions. It also highlights areas for development, program and research, for practitioners and academicians alike.

1.2. Theory and purpose

The dearth of information on engaging fathers calls for theoretical frameworks to help organize and develop practice and research strategies and then determine their effectiveness. With this understanding, we integrated two theoretical models that we thought could aid our consideration of the social and cultural aspects of fatherhood in our review of current research on engaging fathers when their children are CPS-involved. The theories are McCurdy and Daro’s (2001a, 2001b) theory of parental involvement in family support programs and Bronfenbrenner’s (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) ecological theory of human development. These theories were selected because they are anchored in ecological, family systems, and developmental frameworks.

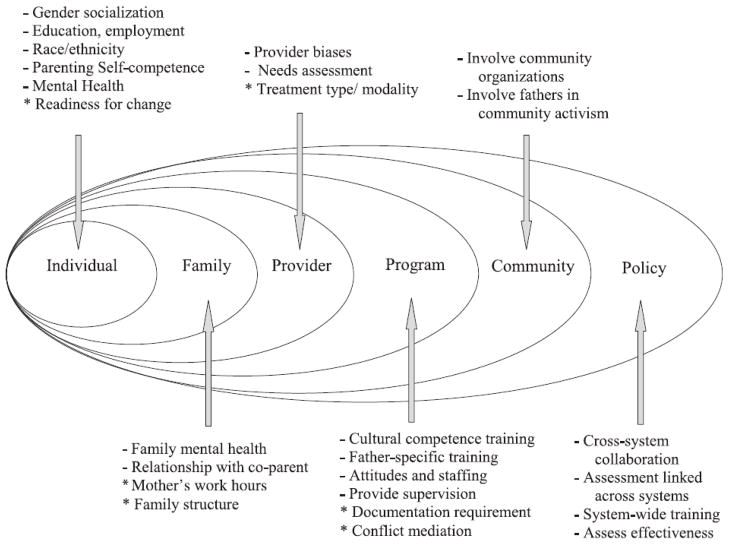

McCurdy and Daro’s (2001a, 2001b) theory of family involvement in support programs seeks to understand how intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention in these programs, specifically with data provided by mothers, are impacted by four ecological domains: (a) individual, (b) provider, (c) program, and (d) neighborhood/community (McCurdy & Daro, 2001a). While the consideration of these ecological systems is viewed as important, they were limited to data regarding mothers. We saw it important to expand and understand how the ecological systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) of family and policy impact the involvement of fathers in support programs (see Fig. 1). The inclusion of these systems recognizes that fathering occurs within a social context that is co-constructed (Gordon et al., 2012; Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000). Both theories have significant implications for child maltreatment (Belsky, 1980, 1993).

Fig. 1.

Ecological model for paternal involvement in family services. Note. Items marked with an asterisk (*) indicate relevance for retention in services.

In our review, this updated framework for understanding paternal engagement identifies factors and strategies at different levels of influence that predict the intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention. For the purpose of this review, a factor was understood as a characteristic or situation that was associated with paternal involvement, either to facilitate it, obstruct it, or somehow change the quality of the specific framework being considered. A strategy was defined as a plan, tactic, or approach that can be implemented and tested to intentionally increase paternal involvement (McCurdy & Daro, 2001b). Our review includes factors and strategies for intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention. These have been described as distinct phases of involvement in services that are relevant to engaging mothers. This review expands the framework to include fathers and also highlight a current gap in the literature. We sought answer the question of, what factors and strategies influence father involvement and the extent to which specific factors and strategies are relevant for fathers’ intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention in services.

2. Method

The selection of studies entailed a search of Medline, PsychInfo, and PubMed databases for articles published in the English language between 1999 and 2010. Search terms used to identify appropriate articles included: (‘fathers’ or ‘men’), in combination with (‘engagement’ or ‘enrollment’ or ‘involvement’ or ‘participation’), and (‘child welfare’ or ‘child protection’). The search yielded a total of 116 abstracts from the combined databases (i.e., 24 for Medline, 32 for PsychInfo, and 65 for PubMed). After removing (25) duplicates, and articles that included search terms in a peripheral context (e.g., rapid repeat birth in El-Kamary et al., 2004; immunization in García-Marcos et al., 2005; parental licensure in Lykken, 2001), a total of 80 articles remained.

The authors reviewed the resulting articles and reference sections to identify articles that met the following inclusion criteria: (a) findings are based on observed or reported involvement of fathers and (b) specific factors or strategies are provided regarding paternal engagement in parenting-related services or with their children as it relates to CPS risk. These criteria resulted in excluding any articles that did not focus on father involvement or that did not measure or identify any predictors of father involvement in services. This approach yielded a total of 39 articles. The literature search was terminated in August, 2011.

3. Review findings

Table 1 describes the studies, organized by ecological level, phase of involvement, and then by author. The table includes a description of the study type, sample characteristics, how each study operationalized paternal involvement, main findings, and the factors or strategies reported for paternal engagement in child and family services (Table 1). Based on our review of the literature, salient patterns and themes emerged. The next section will describe paternal engagement factors and strategies within each of the ecological levels. See Table 1 for a graphic overview of the factors and strategies within individual, family, service provider, program, community, and policy levels.

Table 1.

Paternal engagement factors and strategies at different levels of ecological influence.

| * | ** | Citation | Setting | Study type | Sample/data source |

Involvement measure |

Main findings | Factor | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | I, E | Baum, 2004 | Israel | Case studies | 3 divorced Fxs | Narrative of participation in children’s lives | Ability to cope with simultaneous absence of spousal role and presence of paternal role influenced divorced Fxs’ behavior toward children. | Role conflict — children remind of loss/anger regarding partner | Fx treatment re: role/identity conflicts |

| I | I, E | Doherty et al., 2006 | US, Obstetric clinics | Randomized experimental design, evaluating 8-session group curriculum for couples to increase Fx involvement and skills with infants | 165 couples/first-time parents; attrition 15%: 65 intervention couples and 67 control group couples. (2/3 college degree, mostly middle class) | Fx–child interaction quality per videotaped home observation of 5-minute free play (Parent Behavior Rating Scale — warmth, dyadic synchrony). Interaction/accessibility time chart completed by Mx and Fx. Paternal responsibility (for remembering and scheduling child-care tasks) Scale per Mx and Fx together | Compared to control Fxs, intervention (lasting from 2nd trimester to 5 mos postpartum) Fxs showed greater skills (warmth and synchrony) in interacting with their infant (effect size .42 at 6-month and .30 at 12-month assessment) and were more physically available (42 min) to their babies on work days (no difference on athome days). No group differences in responsibility for childcare tasks. | Self-selection bias: ceiling effect of already highly committed Fxs. May be easier to affect Fxs’ individual skills than their everyday time and partnership Bx (division of labor) | Changes in division of infant care may require changes in society/social norms |

| I | I, E | Dubowitz et al., 2000 | Inner-city pediatric clinics (primary care and HIV-risk) | Cohort study, longitudinal | Interviews with 117 Fxs/Fx figures (of 176 identified) and Mxs of 244 African American 5-year olds (followed from age 2) | Live with, relationship to child, employment, contribution to child support, Who Does What scale, videotaped fathering interactions, parenting sense of competence | Neglect rates did not differ by Fx presence or absence or Fx vs. Fx figure. Child neglect (per CPS +Mx/child home observation) was lower with longer duration of involvement by Fx or Fx figure, greater sense of parenting efficacy, more involvement with household tasks, and less involvement with child care (relative to mother) | Sense of competence in parenting | Target nurturing skills to build competence, theoretically increasing likelihood of involvement |

| I | I, E | Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004 | Random digit dialing | Questionnaire and interview | Caucasian step children 10–18 y/o rating rated noncustodial Mxs (n=56) or Fxs (n=143) | Frequency of seeing, phone contact, receiving mail, overnight visit, and perceived support (from Parent–child Relationship Questionnaire) | No difference in seeing noncustodial parent, but adolescents rated NC Fxs as providing fewer phone calls, mail, overnight visits, and social support | NC Fxs have more difficulty providing social support long distance | Help Fxs plan/do more types of contact and more supportive conversations |

| I | I, E | King et al., 2004 | US | Add Health — 1st wave | 5377 adolescents (18 or younger) with non-resident Fxs whom they knew was alive | In-person, phone, letter contact; types of activities done together; talking about teen’s life; arguing (y/n); closeness (1–5 scale) | Although activity types vary by racial/ethnic group, overall level of closeness and involvement in activities is similar. Higher Fx education (more than income) related (+) to involvement, truer for White (vs. minority) | Fx education, racial/ethnic differences. | |

| I | I, E | Kirisci et al., 2001 | Pittsburgh | Scale development and predictive validation | 344 (122 with SUD+Fxs) boys 10–12 yrs old and follow-up at age 19. Groups were 75/84% White, 25/16% Black | Child report of parent’s Emotional Distance & Parental Involvement (derived from Areas of Change questionnaire) scales= Neglect Scales | Higher neglect score among boys with SUD +Fxs, relative to group with no Fx diagnosis. Neglect at age 10–12 predicted substance use at age 19 | Fx SUD related to child neglect and later child substance use | Address Fx SUD Treatment |

| I | I, E | McLanahan and Carolson, 2002 | US | Call for research | Review of selected studies (not systematic) | Cites fragile families data — 99% of Fxs expressed desire to be involved in raising child, 93% of Mx (75% of Mx not romantically involved with Fx) want Fx involved. 37% Mxs and 43% Fxs lacked HS degree. 39% Mxs on welfare in past year. 4% Mxs report IPV | Education & poverty are obstacles to involvement, despite early desire to be involved | Target Fxs early, recognize Fxs’ individual strengths/needs and family ties, address Mx and Fx needs whether coresident or not. | |

| I | I, E | Mezulis et al., 2004 | Questionnaire | Community sample; 350 Fxs | Time spent in infant care; parental control/warmth | Fxs self-reported parenting style interacted with amount of time spent caring for infant to moderate the longitudinal effect of maternal depression during child’s infancy on children’s development of internalizing behavior problems | More involvement by depressed Fx increases negative impact of maternal depression | Consider mental health of both parents so increased involvement can be constructive | |

| I | I, E | Teitler, 2001 | US (7 urban cities) | 1st wave of fragile families (random recruitment, cross-sectional) | Interviews with 2425 pregnant Mxs and 1859 Fxs (mostly unmarried, less than half coresident) | Co-resident, romantic relationship, and “All Yes” to: child had Fx’s name, Fx named on birth certificate, Fx went to hospital, contributed/offered money during pregnancy or coming year, Fx stated desire to be involved for coming year | Most Fxs, including unwed, were involved w/child at birth and intended to stay involved. Fx involvement related (+) with Mx prenatal care, (−) substance use. Low birth weight was only affected by Fx involvement for high school educated, employed Fxs. Mxs are 4 times more likely to use drugs if Fx had substance use problems. | ~Education and employment of Fx affect benefit of involvement ~Fx substance use issues impact Mx substance use (drug-exposed pregnancy) | Attend to Fx education, employment, and mental health. |

| I | I, E, R | Greif et al., 2007 | US | Focus groups | 18 fathers (2 groups) in a court-mandated parenting education program | Participation, graduation of 12-week cycle | Program reports 70% graduation rate. Common themes: unfair treatment due to gender, race; feel misunderstood regarding raising daughters; macho posturing as father and in group; conflict with child’s Mx; affected by own parenting; and lack developmental knowledge about children | Men’s socialization and experiences re: gender, race/ethnicity, coparent conflict, knowledge gap | Assess to include Fxs’ strengths; cultural sensitivity |

| I | I, E, R | Scott & Crooks, 2006 | London, Ontario in Canada; Boston | Describes Caring Dads Program | Fxs mandated to group intervention for abuse of child or child’s Mx | Completion of 17-week group intervention | By emphasizing early engagement, program reduced attrition-over 1-yr period, of 42 men who started group, 34 completed the program (19% attrition) whereas typical batterer intervention programs report 50–75% attrition | Resistance/readiness for change | Motivational interviewing, build group cohesion, educate challenge (CBT), help Fx take responsibility |

| F | I, E | Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009a | England and Wales | Nationally representative study, cross-sectional | 1515 students (11–16 years old) self-report | “Most involved grandparent” (child rating on how much they can depend on grandparent, feel loved, helped, close) | Similar level of grandparent involvement across family structures; grandparent involvement more strongly associated with decreased adjustment problems for teens from lone parent and step-(relative to 2-parent) families. 41% (n=640) rated more than one grandparent as ‘most involved’, study broke the tie by choosing same sex grandparent | Examine/treat child adjustment from ecological perspective; recognize grandparents as potential source of support. | |

| F | I, E | Jackson, 1999 | US, New York City | In-home interviews | 188 single black mothers of 3–4-yr old child(ren) on welfare currently or formerly | Mx ratings: Fx presence (y/n); 8-pt scale for contact frequency; relationship quality = 6-pt scale satisfaction with love, time, and money Fx gives child; positive/negative emotion in Mx–Fx relationship; and satisfaction with Mx–Fx relationship | Nonresident Fx involvement related (−) Mx depression for unemployed Mxs only. Child Bx problems related (−) with Fx presence, frequency of contact, and Mx satisfaction with amount of time Fx spent with children for employed Mxs only. Mx–Fx relationship related (+) with Fx involvement | Mx–Fx relationship, child behavior, Mx employment | Policies to promote paternal participation, apart from economic support |

| F | I, E | Padilla & Reichman, 2001 | US (16 urban cities) | Secondary data analysis | Unwed Mxs in fragile families data (N=2174). 1206 non-Hispanic Black, 185 Mexican American, 148 other Hispanic, 139 White | (1) Cohabiting, romantic/not cohabiting, or other (friends or no contact); (2) suggested abortion; (3) received $ from Fx | ~Low birth weight (LBW) related (−) to Fx providing $/purchases for baby or cohabiting. LBW 1.5× more likely for romantic/not cohabiting Mxs than for cohabiting Mxs. Mxs who are “friends” or have “no contact” with Fx have lower risk of LBW compared to cohabiting Mxs | The romantic/not cohabitating structure appears to be the most stressful for maternal child health (evidenced by low birth weight) | (To the extent that the family system is stressed, may impact fx’s intent and engagement) |

| F | I, E | Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001 | US (16 sites) | Longitudinal | 1602 children (3–6.5 y.o.) whose mothers (16–22 y.o.) participated in New Chance (welfare-to-work program for teen mothers) | Father co-residence and Mx’s perceived support (sum of yes/no for Fx provided emotional support, information support, financial assistance, goods/services) | Compared to White and Latina Mx, Black Mxs were most likely to live with Grand Mx, least likely to live with Fx, and received highest Fx support. Fx coresidence and support did not have main effect on child cognitive and Bx outcomes. Interaction: among Latinas, Fx coresidence and Grand Mx support were most helpful when experienced singly, not in combination | Family structure and cultural values | Larger family ecology and cultural values (e.g., elder respect) should be taken into account |

| F | I, E | Stein et al., 2000 | Pittsburgh | Correlation, cross-sectional | 54 depressed, 21 hi-risk (1 or more depressed relative), and 23 low-risk 7–16 year olds and their Mx/Fx (N=48/41, 20/17, 20/20, respectively) | Child’s report on Parental Bonding Instrument (Care and Protect), parents report of familial functioning on Family Assessment Device | Fxs of MDD children (relative to low-risk) scored lower on FAD scales of Behavioral Control and General Functioning. Maternal depression related (−) to Fxs’ FAD (open emotional expression) and children’s perceived Fx caring. MDD children perceived Fx as significantly less caring (i.e., affectionless control bonding style) | Mx MDD, child MDD | Prompt management of Mx’s depression to improve parent–child relations; family treatment |

| F | I, E | Whiteside & Becker, 2000 | Include clinic, day-care, court-record reviews | Meta-analysis of post-divorce child outcomes | 17 samples from 12 articles with measure of Fx contact with child or of Mx–Fx interaction in families of children 6 or younger who divorced when child was 5 or younger | Mx report for 1. Pre-separation Fx involvement and child outcomes. Fx report for 2. Post-separation and 3. Current involvement (types and amounts of shared activities) and 4. Measure of relationship quality (e.g., enjoyment, affection) | Of the four, only Fx–child relationship quality predicted child outcomes (+ cognitive, − Bx problems). Measures of Mx–child and Fx–child relationships correlated. Coparenting hostility related to is – Mx warmth and – Fx–child relationship quality. Mx–Fx cooperation related (+) to Fx visits, Fx–child relationship, and child social skills | High conflict between parents interferes with Mx–child and Fx–child relationship | Interventions need to help parents handle conflict, and also actively promote that parents support each others’ parenting |

| F | I, E, R | NICHD, 2004a | US (10 cities) | NICHD study of early child care, prospective, longitudinal | Phone interviews with Mxs of 933 children (1st grade) (not nationally represent. sample) | Before- or after-school care by Fx or Mx’s partner (95% were biological Fxs) | Consistent Fx care in before and after-school hours was more likely in Hispanic families, in 2-parent homes, when Mxs were employed for more hours, children had more early child-care hours, and if Fxs had provided more early child care | Culture, family structure, Mx employment, prior experience in child care | |

| S | I, E | Bellamy, 2009 | US all states | National Survey of Child & Adolescent Well-being | 3978 families with child whose primary caregiver included a legal or biological relative (secondary analysis) | Primary caregiver report of marital status, cohabitation, any secondary caregiver’s relationship with child, child’s contact with noncustodial parent *(73% did and 88% for any male relative) | Most caregivers report male involvement. After controlling for family violence and demographic variables, no male involvement indicator was related to maltreatment rereport, caseworker’s perception of child risk was higher in households with nonparental adult males | Assess, include, and engage adult male family members in diverse family systems | |

| S | I, E | Olds et al., 2004 | Denver, Memphis | 2-yr follow-up program evaluation, home visits | 255 Mxs in condition 1 (screening and referral), 245 with paraprofessional visitor, 235 with nurse | Living with bio Fx | Paraprofessional visited Mxs, compared to controls, were less likely to be married and to livewith bio Fx of child. Nursevisited Mxs had longer time between births and reported less IPV | Paraprofessional visitors urged Mxs to end abusive relationships. | |

| S | I, E, R | Duggan et al., 2000 | Hawaii, Healthy Start (home visits) | Cross-sectional+ longitudinal | N=6553, 373 longitudinal | Home visits (‘risk’ assessed by Fx and Mx Family Stress Checklist) | Families were more likely to receive 12 or more visits in yr 1 if Fx had very high risk assessment score | Willingness to accept services increased with risk (may represent family-perceived need) | Help family identify their needs, offer services that target those needs |

| S | I, E, R | Lam et al., 2009 | US | Pilot study compares, BCT, PSBCT and IBT at pre-, post-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up. | 30 Fxs entering outpatient alcohol treatment, their female partners, and custodial child (8–12 y.o.) | Open CPS case. Also: Mx- and Fx-report on Parental Monitoring (knowledge of child activities), Parenting Scale (laxness and overreactivity) | Behavioral Couples Therapy with and without parent skills showed effects over individual-based treatment on substance use, dyadic adjustment, and IPV. Compared to BCT, PSBCT had larger effect on parenting (PM and PS) and CPS involvement through followup | Couples modality | Integrated treatment to address parent relationship and target parenting skills. |

| Pr | I, E | O’Donnell, 1999 | Illinois; inner city | Record review and interviews | 51 caseworker (44 female) interviews in 2 kinship foster care agencies, about 74 African American fathers whose children (n=241) were in kinship foster care | Caseworker report of Fx participation in services, including family assessments and developing case plans | 9% Fxs participated in initial case assessment; when asked what info they would have wanted, caseworkers mentioned Fx info in 4% of those cases. 5% Fx were receiving services. Caseworkers reported no contact with 62% Fxs in 49% of cases, caseworkers stated not knowing whether Fxs had any strengths regarding child care. 93% of cases, workers reported no discussion about fathers in supervision ~Mx involvement, unlike Fx’s, did not vary by type of placement (maternal vs. paternal kin) | Gender bias, decreased attention to fathers — little to no mention of fathers by workers or relatives per worker report to possible reasons for avoidance | —Attend to gender bias —cultural competence training to sensitize |

| Pr | I, E | O’Donnell, 2001 | Illinois | Record review | Case records and worker questionnaire responses (N=132 Fxs/cases) | Fx participated in case-planning, discussed obtaining custody. Contact w Fx, contact other agencies re: Fx, discuss Fx w Mx | Fxs of 2+ children from 1-Fx families were most involved (59%); Fxs of 1 child from multiple-Fx family were least involved (19%). Mean # of contacts: 9.12 w Mx vs. 1.3 w Fx. ~Workers’ contact topics were mostly for permanency planning for child (27), few for Fx needs (18), none re: extended family resources or Fx health. For 116 Fxs, attempts to contact were zero | Family composition; case load doesn’t account for multi-Fx families, making those Fxs harder to serve | “Beyond the scope of this study” |

| Pr | I, E | O’Donnell et al., 2005 | Chicago | Focus groups | 34 direct service staff in 5 groups | How involved are Fxs in child welfare planning and services; are there policies/practices that discourage Fx involvement? | Fxs are peripheral; 10–20% are on workers’ caseloads. Workers treat Mxs and Fxs the same, question value of Fx specific services —place onus on Fx to seek to be involved. Few explicitly assess Fx needs. | Worker training & philosophy | Programmatic shift in profession to support workers; assessment; research |

| Pr | I, E | Duggan et al., 2004 | Oahu, Hawaii | Randomized trial; program evaluation (Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program) | 643 at-risk families — record reviews and Mx report to staff surveys, and 3 annual interviews by home visitors (53 female, 1 male) | Participation in home visits, contact with child (daily or bdaily), frequency of parent behaviors (e.g., feeding, playing, or teaching), and responsibility for child development (e.g., diet, learning, safety) per Mx report | High attrition — half of families were active at 1 year, 1/4 active at 3 years. Among couples that lived together at baseline, Fx participation was lower for Fxs with jobs, and heavy alcohol use. Program showed no impact on Fxs’ accessibility and engagement. Home visitors rated themselves more competent to work with Mxs than Fxs, esp. substance use and IPV | Worker perceived competence, training (current had 1/2 day on work with men, 1/2 day on IPV) | Training in work with men/fathers |

| Pr | I, E | Scourfield, 2006 | UK | Position paper | Selected studies | “Engaging fathers in child protective services” | History of children’s services based on women working with women. Local policies to prioritize CSA or IPV as targets for treatment, rather than increasing attention to abusive men, practice is to put pressure on women to get men out of the house. Training programs do not prioritize skills/knowledge for engaging men | Gender inequality, polarized practice philosophies (risk or resource) | Train workers in masculinity theory, insist on Fx attendance, work outside office hours, see men as risk and resource, strength-based family intervention (e.g., family group conferences) |

| Pr | I, E, R | Coakley, 2008 | Record review | 88 African American and biracial children among 30 welfare case records | Participation with case plan (yes/no — does not imply compliance); involved in visiting child (yes/no) | 28% fathers were involved in case planning; 61% were involved with children. Children were reunited with birth families more often and had shorter stays in foster care when their fathers were involved (in case plan or with child). Fxs are initially involved in case plan but involvement wanes | Records don’t specify reason (e.g., treatment time frame longer than 12 months, lacks resources for housing vs not interested) | Differentiate between unable and unwilling to explore acceptable ways of staying involved | |

| Pr | I, E | Cowan et al., 2010 | US | Review of intervention strategies | Selected studies and programs | Father involvement strategies | While not recommending elimination of father-only focused interventions, the authors appeal to the importance of strategies focused on the couple relationship regardless of cohabitation or living apart | Role of the interparental relationship | Engage fathers in couples-related intervention due to importance of this relationship |

| Pr | I, E, R | Emery et al., 2001 | Central Virginia | 12-yr follow-up, controlled comparison of child custody | 71 (70% White, 21% Black) low SES families randomly assigned to mediate (35) or litigate (36) child custody disputes | Mx (69%) and Fx (22%) report on other parent: Nonresident Parent–child Involvement Scale (discipline, school functions, talking with child about problems) (2% joint custody, 4% neither) | Nonresidential parents who mediated, rather than litigated, were rated by resident parent as more involved in child life, with more contact, and greater influence in coparenting 12 yrs after custody dispute. Fxs who mediated reported less coparenting conflict at 18-month follow-up, and lower coparenting conflict predicted better child adjustment | Custody dispute resolution method | Promote/provide mediation in interparental conflict resolution |

| C | I, E | Sloand & Gebrian, 2006 | Haiti | Description of program | Father’s clubs in Jeremie, Haiti; participants, program directors | Participating in Fx’s groups | Anecdotal evidence finds that Fx involvement in public maternal child health program is acceptable; Fxs are knowledgeable and involved in health-maintaining activities (e.g., oral rehydration therapy) | Participants organize other activities (e.g., village health fairs); benefit for Fxs is tetanus vaccination | Support of active community-based organizations, personal local interaction |

| Po | I, E | Gagnon & Bryanton, 2009 | Systematic review of program evaluations | 15 RCTs of structured postnatal education to parents 2-months postbirth | 1 of 14 was about Fx involvement/skill with infant (Doherty et al., 2006) | Only 4 of the 15 studies reported assessing whether additional knowledge was acquired as a result of an educational intervention | For research, need for large trials with common outcome measures for comparison | ||

| Po | I, E | Holland et al., 2005 | Wales | Qualitative evaluation | 17 family group conferences (25 children, 31 adult family members, 13 social workers, and 3 FGC coordinators) | “Level of participation” in FGC per semi-structured interviews within 1 month of FGC | 15 FGCs included Fx/Fx figure. Fxs were described as quiet, including 3 usually domineering Fxs described as being restrained by FGC style and presence of child. In 7 FGCs, at least one family member stated wishing that the worker had not left the room — mainly to prevent arguments | Empowerment in decision making, expectation that all family members attend | Family group Conferencing |

| Po | I, E | Huebner et al., 2008 | US; Kentucky | Survey | 1203 social services workers and 339 fathers (of 2431 mailed; 14% return rate) in active Child Welfare case (88% White, 50% married, 46% employed) | General involvement in services, unspecified | Fathers requested more father-centered services. Workers reported trouble navigating parental conflicts and asked for more training in engaging fathers | Barriers identified: Mx reluctant to identify Fx, worker concern about domestic violence | Improving information systems, services guided with father input, staff development on Fx-specific practices |

| Po | I, E | Reeves et al., 2009 | UK | Review and a case study | Health and social services for young men from the time they are sexually active | Involvement with social services and voluntary services | Engaging Fxs before childbirth is a crucial window of opportunity; accurate Fx data should be gathered; coordinated approach to contraception; predominance of women in health/social services may affect engagement with men | Timing, cross-system collaboration, preponderance of female-based services | Engage Fx early, interprofessional communication, employ male workers |

Note.

The first column indicates level of ecological model for which the study is relevant: I = individual; F = family; S = service provider; Pr = program; C = community Po = policy.

The second column indicates the stage of engagement for which the findings are relevant: I = intent to enroll; E = enroll; R = retention; Fx = father; Mx = mother.

3.1. Individual level

There are factors at the individual level that influence the extent to which men will be involved fathers. The reviewed literature suggests that factors including education, gender socialization, racial/ethnic differences, parenting competence, and role conflict impact paternal involvement (Doherty, Erickson, & LaRossa, 2006; Dubowitz, Black, Kerr, Starr, & Harrington, 2000; Greif, Finney, Greene-Joyner, Minor, & Stitt, 2007; Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004).

3.1.1. Intent to enroll and enrollment factors

In a community survey using random-digit dialing, Gunnoe and Hetherington (2004) asked youth (10–18 years old) living in stepparent families to rate involvement of their noncustodial, nonresident parent. This included the frequency of different types of contact, and the perceived social support provided by the noncustodial parent. While youth reported similar frequency of face-to-face visits from noncustodial mothers and fathers, they reported receiving less social support from their noncustodial fathers, which may suggest that fathers have more difficulty demonstrating social support in long-distance scenarios (Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004).

In addition to individual differences in ability to demonstrate social support, fathers’ own sense of competence in parenting can influence their involvement (Doherty et al., 2006; Dubowitz et al., 2000). One evaluation of a group curriculum intervention aiming to increase paternal involvement during pregnancy revealed that the fathers who were already motivated to engage with their child were more likely to enroll and continue in the intervention (Doherty et al., 2006). Fathers who feel more competent in their parenting skills were also shown to remain involved with their children (Dubowitz et al., 2000).

Diminished romantic involvement with the child’s mother has been noted also as an individual factor associated with reduced father involvement (Baum, 2004). Based on a series of case studies, Baum proposed that a possible factor influencing fathers’ involvement is their ability to cope with the conflict in role or identity that they experience when the romantic partnership dissolves. Fathers are seen as less able to be involved in parenting when they have not coped with their loss or anger regarding their relationship with their partners (Baum, 2004).

Father education and employment can present obstacles to paternal involvement (King, Harris, & Heard, 2004; McLanahan & Carlson, 2002; Teitler, 2001). King et al. (2004) found in a nationally representative dataset (AddHealth) that overall level of activity-involvement and closeness was equivalent across racial/ethnic groups. One factor that was positively associated with father involvement was a fathers’ educational level. Interestingly, the positive influence of education on involvement was more pronounced for white fathers.

Mental health issues, including substance use and mood disorders, have been strongly linked to paternal involvement (Kirisci, Dunn, Mezzich, & Tarter, 2001; Mezulis, Hyde, & Clark, 2004). Kirisci et al. (2001) found that fathers with a substance use disorder during their lifetime were rated by their 10- to 12-year old children as less involved and more emotionally distant. Further, these children were at a higher risk of developing substance use disorders by age 19 (Kirisci et al., 2001). Similarly, Mezulis et al. (2004) found that greater involvement by depressed fathers increased negative outcomes for children whose mothers had depression. That is, the negative impact of maternal depression on children’s development of internalizing behavior problems (e.g., depression and anxiety) was greater when depressed fathers were more involved, suggesting that paternal depression can alter negatively the influence of father’s involvement on their children’s well-being.

3.1.2. Strategies for intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention

Individual strategies to engage fathers would include attending to the aforementioned factors. In addition, there have been strategies suggested to better engage fathers in parenting services (Greif et al., 2007; Scott & Crooks, 2006). Greif et al. (2007) propose that services seeking to engage fathers should focus on these men’s strengths and areas of competence. Based on focus groups with fathers involved in a court-mandated parenting education program, a 30% drop-out rate was attributed to fathers perceiving unfair treatment due to gender and race; feeling misunderstood and being seen as dangerous, especially for raising daughters; masculinity norms; and conflict with children’s mothers (Greif et al., 2007).

In addition to attending to strengths, another program for fathers who have maltreated their children or partners provides suggestions for treatment based on the Caring Dads program (Scott & Crooks, 2006). The Caring Dads program for fathers (e.g., biological, step, or common-law) mandated to treatment for domestic violence describe the first goal of the group intervention as developing sufficient trust for engagement. Specifically, by using motivational interviewing strategies, the Caring Dads program successfully reduced attrition from the previous 50–75% range to a 19% dropout rate. Using motivational interviewing is thought to target the individual factor of readiness for change.

3.2. Family level

Although mental health can be seen as an individual-level factor for paternal involvement, the mental health of mothers and other dynamics that influence the family can also influence fathers’ involvement with their children (Stein et al., 2000). These family level factors include inter-parental conflict (Jackson, 1999; Padilla & Reichman, 2001; Whiteside & Becker, 2000) and family structure (Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009b; Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001).

3.2.1. Intent to enroll and enrollment factors

In a cross-sectional study of parent–child bonding among depressed children and those at high-risk (i.e., have family history of depression) or low-risk for depression, depressed children perceived their fathers as less caring and depressed mothers viewed fathers as less emotionally expressive (Stein et al., 2000). This suggests that the mental health of others in the family is associated with lower perceived father involvement. In addition to mental health functioning of family members, high conflict between parents tends to interfere with fathers’ involvement with their children (Jackson, 1999; Whiteside & Becker, 2000). In a meta-analysis of post-divorce child outcomes, hostility in the co-parenting relationship predicted reduced father–child relationship quality (Whiteside & Becker, 2000). Based on interviews with single black mothers, their positive emotion and satisfaction with the mother–father relationship were associated with increased involvement of nonresident fathers (Jackson, 1999).

Given the different configurations that exist for mother–father relationships, one study of unwed mothers compared three kinds of interparental relationships: 1) cohabitating, 2) romantic but not cohabitating, and 3) strictly friends or no contact (Padilla & Reichman, 2001). The romantic but non-cohabitating structure appeared to be the most stressful for maternal child health, as evidenced by 1.5 times greater likelihood that the mother would have a low birth weight baby (Padilla & Reichman, 2001). This suggests that couples in a romantic relationship who are not cohabitating may experience particularly high stress, which is important to consider in attempts to increase father involvement — how to address the interparental relationship.

Family factors of structure and culture have been suggested to impact father involvement (Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009b; Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). In a study of teen mothers in a welfare-to-work program, family culture and structure were associated with paternal involvement differently (Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). Compared to White and Latina mothers, Black mothers were most likely to live with the grandmothers and least likely to live with fathers. Latina mothers perceived most support when grandmother support or father support were experienced singly, but not at the same time (Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). A nationally representative study using the report of children aged 11 to 16 found that grandparents were involved at similar levels regardless of family structure, but benefitted child adjustment more for teens in single parent and step-parent families (Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009b).

3.2.2. Retention factors

According to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, 2004b), in a national prospective study of school care of children from age 1-month through 54-months, consistent care by fathers (either before or after school) was associated with the families’ culture, structure, and fathers’ child care experience early in the child’s life. Specifically, children were more likely to be cared for by fathers in Hispanic families (compared to African American and European American families), in two-parent homes, in families where mothers worked more hours, and when fathers had provided more early childcare (NICHD, 2004b).

3.3. Service provider level

Individuals’ experiences with services, both objective and subjective, can predict whether they will engage and continue in services. Caseworkers’ preconceived notions (Bellamy, 2009), as well as their actual messages (Olds et al., 2004) may impact fathers’ involvement with their children. In addition, it has been suggested that the professional training level of social workers (Olds et al., 2004), the level of perceived or assessed need for services (Duggan et al., 2000), and treatment modality (Lam, Fals-Stewart, & Kelley, 2009) may impact the level of fathers’ involvement.

3.3.1. Intent to enroll and enrollment factors

A national survey of families involved in the Child Welfare system found that most caregivers report a male involved in the child’s life (Bellamy, 2009). While case workers had perceived and documented a higher risk for children in households with a non-biological adult male, whether the father is biological or not, was not related to likelihood of maltreatment re-report (Bellamy, 2009). An evaluation of Olds et al. (2004) home visiting program found that fathers were less likely to be living with their children in those families visited by paraprofessionals, relative to those visited by nurses. This raises questions about the work of paraprofessionals and nurses with regard to father involvement.

3.3.2. Strategies for intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention

A large evaluation of Healthy Start home visiting program in Hawaii found that families were more likely to receive twelve or more visits in cases where the father received a very high risk assessment score (Duggan et al., 2000). These findings suggest that helping families, fathers in particular, identify their needs and offering services to target those needs may help retain those families in services.

In addition to the assessment phase, service providers may be able to retain fathers in treatment based on the treatment modality and objectives. A pilot study comparing Behavioral Couples Therapy with and without Parenting Skills component to Individual Behavioral Therapy found that Behavioral Couples Therapy with Parenting Skills was most effective in treating fathers’ substance use, dyadic adjustment, and IPV while improving parenting skills and reducing CPS involvement throughout a 12-month follow-up (Lam et al., 2009).

3.4. Program level

At the program level, research suggests that engaging fathers successfully requires ongoing assessment, flexibility, evaluation, and adjustment (Coakley, 2008). There are factors such as gender bias, cultural competence, and practice philosophies that affect workers’ ability to engage fathers in services (O’Donnell, 1999; O’Donnell et al., 2005; Scourfield, 2006). A shift in these factors requires that programs provide adequate training, clear expectations, and regular supervision; for this reason, the aforementioned factors are placed in the program level of the ecological model.

3.4.1. Intent to enroll and enrollment factors

Based on record review and interviews with caseworkers of foster care agencies, workers evidenced decreased attention to fathers relative to mothers, lacked knowledge of cultural/contextual obstacles to paternal involvement, and in 93% of cases, and reported no discussion about fathers in supervision (O’Donnell, 1999). A later record review found that for 116 of 132 fathers, CPS workers documented zero attempts to make contact. It was noted that case loads do not take into account that a father of a child in a family with multiple fathers is less likely to be involved than fathers in single-father families making those fathers harder to serve and adding to the work load (O’Donnell, 2001). A subsequent qualitative study found that social workers did not see a need for father-specific services and placed the responsibility on fathers for seeking to be involved (O’Donnell et al., 2005). A home visiting program evaluation found that workers rated themselves as less competent to work with fathers than mothers (Duggan et al., 2004).

3.4.2. Strategies for intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention

Scourfield (2006) notes that services are historically focused on mothers and that training programs do not provide workers with the knowledge and skills to engage men. For retention in particular, documentation requirements may help differentiate between fathers unwilling to be involved and those unable to be involved due to unmet needs. A review of caseworker files revealed that while fathers were involved initially in case planning, their involvement waned and there was no documentation of the reasons why (Coakley, 2008). A study of parental involvement after child custody disputes suggests that using mediation rather than litigation to resolve custody disputes results in lower co-parenting conflict, higher maternal ratings of fathers’ involvement, and better child adjustment twelve years following the dispute (Emery, Laumann-Billings, Waldron, Sbarra, & Dillon, 2001). Additionally, a review by Cowan, Cowan, and Knox (2010) suggests that while not abandoning father-only interventions, programs should apply primary focus on the couple-relationship regardless of parent’s current cohabitation status to increase enrollment and retention in services.

3.5. Community level

The reviewed literature suggests that community level factors are seldom examined with regard to fathers’ involvement in child-related services. There is some evidence that community factors can be used successfully to engage fathers, however. In terms of phase of engagement, the community-level data concerns one study that provides information about fathers’ intent to enroll and enrollment, rather than retention. Fathers’ clubs in Haiti, a program to engage fathers in promoting maternal child health, describes successful strategies that include involving community-based organizations, providing a direct benefit to fathers (e.g., tetanus vaccines), and having fathers organize activities for the community (Sloand & Gebrian, 2006).

3.6. Policy level

At the policy level, researchers have provided some suggestions for strategies that may increase paternal involvement or at least aid in our assessment of the involvement level of fathers. Policy-level strategies to promote fathers’ intent to enroll and enrollment in services include improving information systems across various social services (Huebner et al., 2008) and cross-system collaboration (Reeves et al., 2009). Further, providing staff development for work with fathers and engaging the whole family in treatment planning (Holland, Scourfield, O’Neill, & Pithouse, 2005) are specific strategies that are suggested to impact provision of services and, consequently, father involvement.

3.6.1. Strategies for intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention

Because fathers whose children are involved with CPS may also have ties to family welfare, child support, treatment facilities, and other programs, Huebner et al. (2008) suggest the development of an assessment system that is common or linked across these social services systems. Requiring staff-development in father-specific practices (Huebner et al., 2008), and changing the decision-making structure so that all family members are expected to be involved (Holland et al., 2005) are additional shifts that can be implemented at the policy level. A systematic review of post-natal parent education calls for large trials with common outcome measures so that effectiveness of interventions can be assessed (Gagnon and Bryanton, 2009), which is relevant to fathers attached to these children.

4. Discussion

Fatherhood plays an essential role in a child’s development. Engaging fathers in services can directly impact the way fathers contribute to this development. There are a number of contextual factors that affect men across multiple systems which may influence their involvement with services. One area where the challenge of fatherhood is most present is in their involvement with CPS. In the CPS context, there has been an on-going struggle with finding the best ways to engage fathers. This paper seeks to help CPS and those interested in serving fathers turn the corner by summarizing the available research and making recommendations for research to engage fathers whose children are involved in CPS services.

This comprehensive review advances the literature by identifying factors (i.e., person or situational characteristics) and strategies (i.e., tactics of service provision) that impact paternal intent to enroll, enrollment, and retention in CPS related services across ecological levels (i.e., individual, family, service provider, program, community, and policy strategies). The attention to individual and contextual factors can influence fathers’ engagement in services and enhance CPS efforts to meet the needs of families (McCurdy & Daro, 2001a).

This review contributes to the literature by applying an ecological framework that can be used and tested, adding to the practice, policy, and research discussions occurring. It is important to note that all of the ecological levels described thus far are nested within each other (Belsky, 1993). This means that a provider can only use strategies successfully and address factors if they are supported by the program, realistic for each family, and matched to each father’s individual issues and community challenges. Given this, changes at any level should include some consideration of the resources and needs at the ecological levels above and below it (Child and Family Services Reviews Factsheet, nd).

The value of promoting healthy father involvement rests on the observation that father-related variables (e.g., employment status, age, educational attainment, relationship with the mother and the child, and potential use of psychoactive substances) impact the risk for child neglect and abuse (Guterman & Lee, 2005; Guterman et al., 2009). There are also CPS policy-driven expectations for involving fathers that demand attention to all the factors at play (Sylvester & Reich, 2002). This makes it important to understand what can be done to engage fathers with services that reduce risk and promote children’s well-being. Major points will be summarized under the global headings of Cultural and Environmental Factors, Potential Barriers to Services, Intervention Strategies, and System Implementation. Under each heading we have sought to identify areas of concern and potential for additional research from the reviewed literature.

4.1. Cultural and environmental factors

A primary area of focus suggested by the literature in regards to engaging and maintaining fathers, involves the role of cultural factors and environmental context. These factors not only play important roles at each step of the ecological model but also interact in such a way that each level may influence the other. These relationships can be highlighted through considering the cultural factors such as race and education. At the individual level, studies of father involvement reveal consistently that income and education are positively associated with father involvement (Erkut, Szalacha, & Coll, 2005; Holmes & Huston, 2010; Johnson, 2001). King et al. (2004) documented that the positive influence of education is stronger for white fathers relative to fathers of color. This raises questions about the social differences in how fathering is conceptualized and enacted within racial, ethnic, and cultural contexts. It also suggests that education might add to the conceptual understanding of fathering. The ways in which race and education impact father’s involvement has direct implications at the service provider and program levels. For example, as education appears to impact father involvement at the individual level, adding an educational component into the design of engagement and service strategies by providers and within program development may increase levels of involvement. Gordon et al. (2012) indicated that while academic education may be important for father involvement, strategies are needed to increase all men’s understanding of their unique contribution to children’s development. Social support for the father role is also impacted by the cultural and environmental contexts of the men. Using this information to help connect at the service provider level and integrating this into services at the program level helps to facilitate a more expansive program development model. At the policy level, this calls attention to the need for greater public awareness of the unique role of fathers and their contribution to children’s development. Cultural differences, such as race and education, are usually understood as individual characteristics that men bring into their role as fathers. The impact of these factors extends beyond their additive affects to possible interaction effects (King et al., 2004). That is to say, a simple relationship and direct relationship between factors such as race an education should not be assumed. It is important to conceptualize how the interplay of these factors may be influential while also realizing they can be unique to the individual.

Another aspect of culture and environment that is important across ecological levels is the social context. The social context, including culture and family, helps to define what is expected of fathers and can serve to reinforce, or not, their involvement with children and with family related services (Coltrane, 2007; Marsiglio et al., 2000). Also, the relationship between paternal involvement and families’ household structure may vary or be influenced, in turn, by factors of ethnicity and culture (NICHD, 2004b; Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). That is to say, ethnicity and culture can often play a role in how the family and relationships within the family are organized, which in turn may influence paternal involvement. While these factors may appear to be germane only to the individual and family levels, their effects certainly extend beyond. In this instance, these observations suggest that specific training components need to be provided at the service provider and program levels regarding cultural competence.

The community setting can also reverberate across the levels of the ecological model. Whether defined by physical characteristics, economic demarcations, or by residents’ perceptions of their neighborhood, the community influences children’s development and parents’ caregiving capacity (Daro & Dodge, 2009). For example, child maltreatment is considered a stress-related phenomenon and parents who live in more stressful communities are at higher risk for involvement with CPS (Barth & Blythe, 1983). The communities in which families are situated create a context that can facilitate or hinder the ability of any parent to engage in formal services (Daro et al., 2007). Families in neighborhoods with low levels of social organization may not have access to, or awareness of, formal resources. When they are aware of these services, the social context may erect barriers, real or perceived, that negatively influence their involvement. There is some support from the literature that connecting a group intervention (program level) for fathers to the greater community (community level) can achieve their engagement and result in behavior change (individual level) that influences the health and well being of their children and families (family level; (Sloand & Gebrian, 2006).

4.2. Potential barriers to services

When discussing ways and means of increasing father’s engagement and adherence to services, it is also important to address potential barriers to these desired outcomes. One area that can present potential barriers across all levels of the ecological model involves fathers’ mental health. Men’s mental health functioning can inhibit their ability to be engaged actively with their children. Some research also suggests that the mother’s mental health issues may exacerbate their experience (Mezulis et al., 2004). Among child welfare cases, substance abuse is associated with higher rates of child re-victimization (Brook & McDonald, 2009; Ondersma, 2007), greater likelihood of out of-home placement (DHHS, 1997), longer stays in care (Connell et al., 2007; Vanderploeg et al., 2007), and higher rates of termination of parental rights and child adoption (Connell et al., 2007). In addition, substance use disorders (SUD) are related to fathers’ decreased involvement and to their own children developing SUDs (Kirisci et al., 2001). These observations raise questions about the role of paternal substance use in perpetuating a cycle of under-involved fathering across generations. Thus, identifying and addressing the mental health and substance use challenges of men may help meet the goal of engaging fathers in services and improve fathers’ ability to be safe and healthy resources for their children.

In addition, gender socialization, parenting competence, and role conflict can all impact fathers’ involvement (Doherty et al., 2006; Dubowitz et al., 2000; Greif et al., 2007; Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004). Fathers that don’t internalize the role of fatherhood or those that lack adequate parenting skills are examples of cases in which it may be more difficult to engage fathers in services. Some other factors supported in the reviewed literature include family processes such as inter-parental conflict (Jackson, 1999; Whiteside & Becker, 2000) and family structure (Jackson, 1999; Padilla & Reichman, 2001; Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). These factors impact the role that fathers play with their children as well as how involved they are in parent-related services.

Understanding the specific needs of fathers can also decrease barriers to engagement and adherence to services. Fathers’ relative difficulty showing support in non-custodial scenarios (Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004), the influence of perceived self-competence (Dubowitz et al., 2000), and the difficulty of maintaining the father role despite dissolution of the mother–father relationship (Baum, 2004) all are unique needs of fathers. Fathers’ difficulty meeting children’s needs may be related to their conceptualization of their role as men and how these interact with societal expectations for the role of fathers (Masciadrelli, Pleck, & Stueve, 2006). This demonstrates the difficulty of integrating fathers into CPS. The current review reveals the importance of examining service providers’ preconceived notions about fathers (Bellamy, 2009) and what workers might communicate, directly and indirectly, to fathers and families (Olds et al., 2004).

4.3. Intervention strategies

The literature on engaging fathers sets forth a number of intervention strategies that can play important roles within and between components of the ecological model. These strategies range from skills-building at the individual level to determining the types of assessments to be carried out at the service provider level. One such area of intervention involves helping fathers identify areas of strength and teaching skills that may help fathers maintain an involved role independently of their relationship to the child’s mother. These skills can also be self-reinforcing in that implementing them successfully may improve father–child relationships and fathers’ perceived self-competence (Gordon et al., 2012).

In addition, strategies and interventions that may support fathers’ involvement with CPS as their children are in the system include attending to mental health needs, strengthening capacity to parent, providing auxiliary support, improving fathers’ functioning on multiple levels, and identifying nurturing strengths (Greif et al., 2007). Interventions targeting these areas may help increase fathers’ self-competence in their role. The social role of men may make it difficult to effectively nurture children from afar (Greif et al., 2007) so helping them to develop ways to be emotionally available to their children while maintaining a sense of manhood would be key within this system. From a strength-based perspective, seeing a father’s behavior in the context of adherence to traditional masculine norms may help providers respond to them more effectively (Roggman, Boyce, Cook, & Cook, 2002). This may be especially true for fathers who feel disenfranchised from society and may hold lower levels of trust in the system and those who represent it (e.g., fathers from minority backgrounds).

The literature suggests that to increase fathers’ involvement with their children and parenting related services, family-based interventions should focus on co-parenting rather than cohabitation (Padilla & Reichman, 2001). Co-parenting interventions would need to emphasize facilitating clear communication between all family members regarding the expected and desired level of involvement. This may require negotiation, given that each family member may operationalize child-rearing roles differently. While the mother may often be seen as the gatekeeper, the whole family and in some contexts extended family, has a role to play in facilitating paternal involvement. This highlights the need for family-based assessment and services, which increases the workload placed on service providers.

It is important to consider what fosters for men an alliance with the service provider, given that experiencing connection with a service provider is linked to increased efficacy and involvement in services (Cusack, Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, 2006). For example, individual level factors indicate that a strength-based conceptualization may be more likely to engage men. This suggests that such an approach may help foster an alliance and should be extended by service providers to increase father involvement in services. In addition, the assessment is often the first extended time spent with fathers and is an important step in building an alliance. The assessment appears to be an important hook for engaging fathers in parenting-related services by helping fathers understand how services may benefit them and their children (Duggan et al., 2000).

The apparent discrepancy between highlighting strengths and identifying needs is really a balancing act that is being suggested by the literature. It brings to the fore the need for service providers, and the programs and policies under which they work, to consider the nuances involved in engaging fathers. Having fathers recognize their need for services or behavioral change, a strategy supported at the service provider level is adequate to the extent that it does not go against individual level needs and masculine social norms of self-competence and independence that impact fathers’ engagement. This delicate balance can be reinforced through program level factors that influence service providers’ daily strategies.

4.4. System implementation

Finally, it is important to understand how the steps involved in implementing a system can impact paternal intent to enroll as well as retention in CPS related services across ecological levels. The structure of a program and the extent to which it supports providers influence the way services are delivered. It can also enhance the extent to which participants are engaged in services (McCurdy & Daro, 2001a). Programs could help engage fathers by providing specialized training in work with fathers, clear expectations about the types and frequency for workers’ attempts to contact fathers, and regular supervision to support the challenging task of both engaging and retaining fathers. The need for specialized training is supported by work that is happening outside of the United States (Berlyn, Wise, & Soriano, 2008). The Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (SFCS) in Australia documented program components such as the provision of staff training, staff positions that focus on fathers, flexible hours, non-hierarchical service-delivery, a strength-based perspective, and male-friendly services as being associated with increased father involvement (Berlyn et al., 2008).

The most cited recommendation for engaging fathers include centralizing the information (Huebner et al., 2008) and improving communication among the various systems in which a father may be involved (Reeves et al., 2009). Given that fathers whose children are involved with CPS are likely to have ties to family welfare, child support, treatment facilities, and other programs. This strategy, although it requires careful inspection due to risks for infringing individual rights such as HIPPA regulations and additional laws regarding protection of individual privacy, is worth exploring. Having a standardized set of information that is collected for families that include father involvement information would help assess the impact of interventions by allowing data to be collected and analyzed in a more uniform manner. Importantly, the measures of father involvement would need to varied, as different types of involvement (e.g., co-residence, shared activities, frequency of contact, providing financial and social support) may be impacted differentially by the policies enacted.

5. Future directions

As the study of father engagement continues, researchers would do well to attend to a number of areas that are under-examined in the literature. Qualitative studies provide rich descriptions of the obstacles that both fathers and providers face as they try to work through the CPS process to achieve positive outcomes for children. Quantitative studies provide external validity to findings so that programs can invest in programs and services that are evidence-based. More research is needed that combines qualitative and quantitative or mixed methods approaches.

While the strategies reviewed herein are a good starting point, it is important to note that engagement strategies require adjusting for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) families, income, and education differences. On average, only 9% of Latino fathers and 14% of African American fathers have graduated from college, compared with 25% of Caucasian men (U.S. Census, 2005). This disparity directly influences their employment opportunities and may increase the risk for emotional and physical health problems of these fathers (Behnke & Allen, 2007; Parke et al., 2005). The restricted access to resources has been associated also with reduced family functioning in terms of heightened family conflict and negative parent–child interactions (Simons & Johnson, 1996). To engage fathers, professionals need to understand the contextual factors affecting men and the multiple levels impacting their engagement in service.

Additional areas of future research include examining father’s perceptions and experiences across the ecological systems examined in this review with CPS and its services in an effort to reduce barriers to these services. In regards to strategic interventions, future studies would do well to consider how the social context affects enrollment and retention in services. Implementation of data collection methods and communication across systems would allow for a more rigorous analysis of factors that engage and maintain fathers in services. Communication across systems would also assist programs in having access to more information about fathers as well as potentially streamlining an often overburdened system. It is important that future research continue to address potential biases at the service provider and program levels that may impact men’s involvement, engagement, and retention rates. In addition to impacting father’s involvement, this line of research must also consider how implementing these strategies may add or detract to collateral risk for mothers. The final, and potentially most salient, concern for future research is how these activities impact the children involved. The consideration of their risk for abuse and neglect, as well as factors such as permanency placement and long-term involvement with CPS, should continue to be the impetus for improving services and increasing father’s involvement.

Acknowledgments