Abstract

Objectives

Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin homologue (OAAH) proteins belong to a recently discovered lectin family. The founding member OAA and a designed hybrid OAAH (OPA) recognize similar but unique carbohydrate structures of Man-9, compared with other antiviral carbohydrate-binding agents (CBAs). These two newly described CBAs were evaluated for their inactivating properties on HIV replication and transmission and for their potential as microbicides.

Methods

Various cellular assays were used to determine antiviral activity against wild-type and certain CBA-resistant HIV-1 strains: (i) free HIV virion infection in human T lymphoma cell lines and PBMCs; (ii) syncytium formation assay using persistently HIV-infected T cells and non-infected CD4+ T cells; (iii) DC-SIGN-mediated viral capture; and (iv) transmission to uninfected CD4+ T cells. OAA and OPA were also evaluated for their mitogenic properties and potential synergistic effects using other CBAs.

Results

OAA and OPA inhibit HIV replication, syncytium formation between HIV-1-infected and uninfected T cells, DC-SIGN-mediated HIV-1 capture and transmission to CD4+ target T cells, thereby rendering a variety of HIV-1 and HIV-2 clinical isolates non-infectious, independent of their coreceptor use. Both CBAs competitively inhibit the binding of the Manα(1-2)Man-specific 2G12 monoclonal antibody (mAb) as shown by flow cytometry and surface plasmon resonance analysis. The HIV-1 NL4.32G12res, NL4.3MVNres and IIIBGRFTres strains were equally inhibited as the wild-type HIV-1 strains by these CBAs. Combination studies indicate that OAA and OPA act synergistically with Hippeastrum hybrid agglutinin, 2G12 mAb and griffithsin (GRFT), with the exception of OPA/GRFT.

Conclusions

OAA and OPA are unique CBAs with broad-spectrum anti-HIV activity; however, further optimization will be necessary for microbicidal application.

Keywords: OAA, OAAH (OPA), glycosylation, broad spectrum, anti-HIV activity, PBMCs, microbicide

Introduction

HIV still continues to spread at an alarming rate, especially among women in developing countries, despite successful HIV prevention and treatment strategies in developed countries (highly active antiretroviral combination therapy, condom use, reduction in the number of sexual partners, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections). A vaccine against HIV offers the most beneficial avenue for reducing viral transmission and novel infections. However, effective approaches to elicit protective immune responses still remain elusive. Microbicides or pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) agents, topically delivered drugs that can be applied vaginally or rectally, constitute an alternative to condoms as the most feasible procedure for primary prevention of HIV. Until now, only one antiviral compound has been reported to be active as a microbicide: in the CAPRISA 004 trial, a 1% tenofovir gel reduced women's risk of HIV infection by 39%.1

The HIV entry point and processes that permit the virus to stably interact with the cellular membrane constitute an attractive focus for microbicide development. HIV enters CD4+ target cells using the major envelope glycoprotein gp120 that engages CD4 as the primary receptor and CCR5 or CXCR4 as coreceptors. This initial interaction is followed by insertion of the gp41 fusion peptide into the cellular membrane, resulting in membrane fusion.2 Glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 are heavily glycosylated trimeric assemblies that are present on virion surfaces.3–5 Carbohydrate-binding agents (CBAs) that interact with the glycans on the viral envelope proteins of HIV are able to block the viral entry process, with cyanobacterial lectins considered the most potent CBAs against HIV-1.6 The lectins cyanovirin-N (CV-N), microvirin (MVN), Microcystis viridis lectin, scytovirin and especially griffithsin (GRFT) exhibit broad anti-HIV activity and are under consideration as potential microbicidal candidates for prevention of sexual HIV transmission.7–17 All these lectins possess unique properties, such as distinct oligosaccharide specificities and varying number of carbohydrate recognition sites. These differences contribute to variations in their antiviral activity profile. Overall, the cyanobacterial lectins are potent antiviral compounds, some exhibiting anti-HIV activity at nanomolar concentrations.18

Here, we further focus on the antiviral activity of the novel algal lectin Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin (OAA). Its unique structure and carbohydrate-binding properties have been investigated in detail; however, its antiviral activity profile has not been thoroughly evaluated. OAA is a 13.9 kDa protein that was first isolated from O. agardhii strain NIES-204.19,20 Compared with all other antiviral lectins, the carbohydrate recognition of Man-9 by OAA is unique:21 while most of the known HIV-inactivating lectins recognize the reducing- or non-reducing-end mannoses of Man-8/9, OAA has no measurable affinity for monosaccharides and requires at least a pentasaccharide for binding.20

Recently, genes coding for OAA-homologous proteins (OAAHs) have been discovered in a number of other prokaryotic microorganisms22 and the hybrid OAAH protein (OPA) was created by combining the OAA gene together with the gene of the Pseudomonas fluorescens agglutinin (PFA) via a two nucleotide linker, generating a 267 residue protein chimera. Initial studies of its anti-HIV activity revealed that OPA was slightly more potent than OAA.23

Here, we report an extensive evaluation of OAA and OPA in broad antiviral tests and the CBAs were assessed in multiple HIV replication and viral transmission assays. In addition, their potential use as microbicidal agents was further explored in two-drug combination assays and HIV-1 target cell activation experiments.

Materials and methods

Test compounds and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

Expression and purification of the algal lectin OAA (13.93 kDa) and the hybrid OAAH protein OPA (27.96 kDa) have been described previously.23,24 MVN (14.3 kDa) from the microcystin-producing strain Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806 was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously and was a kind gift from Prof. E. Dittmann (University of Potsdam, Germany).25 CV-N (11 kDa) was a kind gift from Dr C. A. Bewley (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The 2G12 mAb was purchased from Polymun Scientific (Vienna, Austria). GRFT (25.4 kDa) was a kind gift from Prof. K. E. Palmer (University of Louisville, KY, USA). Hippeastrum hybrid agglutinin (HHA; 50 kDa) was ordered from Gentaur molecular products (Kampenhout, Belgium). Rabbit-antihuman (RaH) IgG-FITC was purchased from DakoCytomation (Glostrup, Denmark).

Cells, cell cultures and viruses

The MT-4 T cell line was a kind gift from Dr L. Montagnier (then at the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France) and Raji/DC-SIGN+ B cells were kindly provided by Dr L. Burleigh (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France). Human CD4+ T lymphocytic C8166, HUT-78 and SupT1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). These cell lines were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BioWhittaker Europe, Verviers, Belgium) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Gent, Belgium) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified CO2-controlled atmosphere. Buffy coat preparations from healthy donors were obtained from the Blood Transfusion Center (Red Cross, Leuven, Belgium). PBMCs were cultured in cell culture medium (RPMI 1640) containing 10% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine or were activated with 2 μg/mL phytohaemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma–Aldrich, Diegem, Belgium) for 3 days and cultured in cell culture medium in the presence of 2 ng/mL IL-2 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, IN, USA).

HIV-1 NL4.3 (X4), IIIB (X4) and BaL (R5) were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, USA). HIV-1 HE (R5/X4) was isolated from a Belgian AIDS patient in 1987.26 The HIV-2 strain ROD was originally obtained from the Medical Research Council (London, UK). Primary clinical isolates representing different HIV-1 subtypes were all kindly provided by Dr J. Lathey (BBI Biotech Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and their coreceptor use (R5 or X4) was determined in our laboratory in the astroglioma U87.CD4 cell line transfected with either CCR5 (U87.CD4.CCR5) or CXCR4 (U87.CD4.CXCR4). The HIV-1 NL4.3 strain was made resistant to 2G12 mAb or MVN as described previously.15,27

Antiviral replication assay in the MT-4 T cell line

MT-4 cells were infected as follows: 5-fold dilutions of the compounds were added to 96-well flat-bottomed plates (International Medical, Brussels, Belgium). Then, to each well, 7.5 × 104 MT-4 cells were added and the cells were infected with ∼100 TCID50 (tissue culture infectious dose 50%) of the viruses HIV-1 NL4.3, IIIB, NL4.32G12res, NL4.3MVNres or IIIBGRFTres. The cytopathic effect (CPE) induced by the virus was checked microscopically at regular times. When strong CPE was observed in untreated HIV-infected cells (mostly after 5 days of culture), the cell viability was assessed spectrophotometrically via the in situ reduction of the tetrazolium dye MTS using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The absorbance was then recorded at 490 nm with the 96-well plate VersaMax reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and compared with cell control wells (cells without virus and drugs) and virus control wells (cells with virus but without drugs). The median inhibitory concentration (IC50), or the concentration that inhibited HIV-1-induced cell death by 50%, was calculated from each dose–response curve.

The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of compounds was determined from the reduction of viability of uninfected MT-4 cells or PBMCs exposed to the compounds, as measured by the MTS/phenazine ethosulfate (PES) method described above.

Antiviral testing of OAA and OPA against HIV-1 isolates in PBMCs

PHA-stimulated blasts were seeded at 0.5 × 106 cells per well into a 48-well plate (Costar; Elscolab, Kruibeke, Belgium) containing varying concentrations of compound in medium containing IL-2. The virus stocks were added at a final dose of ∼100 TCID50 of HIV-1 or HIV-2. Cell supernatant was collected at days 9–12 and HIV-1 core antigen (Ag) in the culture supernatant was analysed by using a p24 Ag ELISA kit according to manufacturer's guidelines (Perkin Elmer, Zaventem, Belgium). For HIV-2 p27 Ag detection, the INNOTEST from Innogenetics (Temse, Belgium) was used.

Giant cell formation in cocultures of CD4+ SupT1 cells with persistently HIV-1-infected HUT-78 cells

Persistently HIV-1 IIIB-infected HUT-78 cells (HUT-78/IIIB) were generated by infection of HUT-78 cells with HIV-1 IIIB. The cells were subcultured every 3–4 days and persistent virus infection was monitored in the culture supernatants using HIV-1 p24 Ag ELISA.

For the cocultivation assay, different concentrations of the test compounds along with 1 × 105 SupT1 cells/50 μL were added to 96-well plates. Then, a similar amount of HUT-78/IIIB cells (50 μL) was added. After 24 h, IC50s were determined light microscopically (pictures taken by Moticam 1000 1.3M Pixel) based on the appearance of giant cells or syncytia in the cocultures. The total number of syncytia was counted.

Effect of OAA and OPA on virus capture by Raji/DC-SIGN cells

High amounts of HIV-1 HE (100 μL; ∼3.2 × 106 pg p24/mL) were exposed to serial dilutions of the test compounds (200 μL) for 30 min. Then, exposed virus suspensions were mixed with Raji/DC-SIGN cell suspensions (200 μL; 5 × 105 cells) for 1 h at 37°C, after which the cells were thoroughly washed with culture medium. The Raji/DC-SIGN cell cultures were then analysed for HIV-1 p24 Ag content by a p24 Ag ELISA kit.

Exposure of Raji/DC-SIGN cells to HIV-1 and subsequent cocultivation with CD4+ C8166 cells in the presence of OAA and OPA

Raji/DC-SIGN cells were exposed to HIV-1 HE for 2 h at 37°C and thoroughly washed. Various concentrations of the test compound (100 μL) were added in a 96-well plate along with 1 × 105 CD4+ C8166 T cells (50 μL). Then, a similar amount of HIV-1-exposed Raji/DC-SIGN cells were added and giant cell formation was evaluated microscopically 20–24 h post-cocultivation. The total number of syncytia was counted.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies

SPR is a useful method to study the interaction between CBAs and the viral envelope protein gp120.28 Biotinylated rgp120 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Woburn, MA, USA) was reversibly captured on a sensor chip CAP (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) at a density of ±85 resonance units according to the manufacturer's instructions. A reference flow cell was used as a control for non-specific binding and refractive index changes. All interaction studies were performed at 25°C on a BIAcore T200 instrument at a flow rate of 30 µL/min. The CBAs were diluted in HBS-P (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4) supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2. Kinetic characterization was performed using single-cycle kinetics and data were fitted to the 1 : 1 binding model (BIAcore T200 Evaluation software, version 2.0). In an SPR-based competition assay, the rgp120 surface was saturated by a 2 min injection of the first CBA immediately followed by a 2 min injection of the second CBA while keeping the concentration of the first CBA constant. Dissociation was followed for another 2 min. The surface was regenerated with an injection of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride in 0.25 M NaOH.

Flow cytometry staining and analysis

MT-4 cells were infected with NL4.3 and analysed when CPE started to occur (3–4 days after infection). Briefly, after washing with PBS containing 2% FBS (PBS/FBS2%), cells were pre-incubated with or without OAA or OPA at different concentrations for 30 min, washed and then incubated with 2G12 mAb for the same time. Then, the cells were washed and further incubated with RaH-IgG-FITC (30 min). As a control for non-specific background staining, cells were stained in parallel with RaH-IgG-FITC only. Then, the cells were washed, fixed with 1% aqueous formaldehyde solution and data were acquired with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

The expression of cellular activation markers was measured after 3 days of incubation of freshly isolated PBMCs with varying concentrations of OAA and OPA or PHA at 37°C. Briefly, after washing with PBS/FBS2%, cells were incubated with PerCP-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb (BD Biosciences) in combination with PE-conjugated anti-CD25, anti-CD69 or anti-HLA-DR mAbs (all from BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. For non-specific background staining, cells were stained in parallel with Simultest Control IgG γ1/γ2a (BD Biosciences). Finally, the cells were washed, fixed with 1% formaldehyde solution and analysed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer; the data were acquired with CellQuest software and analysed with FLOWJO software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA, USA). For calculation of the mAb binding, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each sample was expressed as the percentage of the MFI of control cells (after subtracting the MFI of the background staining) and IC50s of the compounds were calculated.

Two-drug combination studies

EC50s and EC95s before and after combination, the dose reduction index (DRI) and the combination index (CI) were calculated using Windows®-based CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) according to the median effect principle of Chou and Talalay,29,30 whereby CIs <0.9 are counted as synergistic, 0.9 < CIs < 1.1 is additive and CIs >1.1 are antagonistic.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis performed on the results included the calculation of the mean, standard error of the mean (SEM) and P values by use of Student's t-test. The significance level was set as P = 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Antiviral activity profile of OAA and OPA in PBMCs

OAA and OPA were originally tested against the X4 HIV-1 laboratory strains IIIB and NL4.3 (proviral clone R9). IC50s of ∼30 and 7.5 nM for OAA and OPA were obtained, respectively.20,23 In our studies, OAA and OPA had comparable activity against HIV-1 NL4.3 in MT-4 cells with IC50s of 24 ± 5 and 18 ± 2 nM, respectively (Figure 1a). To consider these lectins as potential microbicide or PrEP candidates, they not only have to be active against X4 viruses but also against R5 viruses, because viruses using the CCR5 receptor are considered to be responsible for the sexual transmission of HIV-1.31 Therefore, the antiviral activity of OAA and OPA was evaluated in PBMCs against HIV-1 X4, R5 and X4/R5 and HIV-2 laboratory strains, as well as against a wide variety of primary HIV-1 isolates. In addition, the anti-HIV activities of these lectins were compared with those of the Manα(1-2)Man-specific CBAs MVN, CV-N and 2G12 mAb (Table 1). OAA and OPA were active against the HIV-1 laboratory strains irrespective of their coreceptor use, with IC50s in the range of 19–60 and 8–31 nM for OAA and OPA, respectively. Also, both CBAs showed potent activity against the HIV-2 strain ROD, which is in sharp contrast to MVN and 2G12 mAb, which possess no activity against HIV-2 (Table 1). In addition, OAA and OPA exhibited potent and consistent activity against various subtype HIV-1 isolates (groups M and O), with IC50s ranging between 6 and 57 nM (Table 1). CV-N was also active against all of the tested isolates; however, more variability in potency was observed against the different subtypes. In contrast, MVN was not active against the HIV-1 isolate of group O and lost considerable antiviral activity against the HIV-1 subtype C isolate while the 2G12 mAb was only active against the HIV-1 isolates of subtypes A and B (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the antiviral activities of OAA and OPA in four different cellular assays. The CBAs efficiently inhibit infection of CD4+ T cells by HIV virions (a), syncytium formation between HIV-infected cells and uninfected target CD4+ T cells (b), capture of HIV particles by DC-SIGN-expressing cells such as Raji/DC-SIGN or dendritic cells (DCs) (c) and the transmission of DC-SIGN-captured HIV to CD4+ target T cells (d). Mean values ± SEM of two to five independent experiments are shown. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Table 1.

Anti-HIV activity profile (IC50 in nM) of OAA and OPA in PBMCs

| Agent | HIV-1 |

HIV-2 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| laboratory strain |

group M |

group O |

||||||||

| NL4.3 (X4) | BaL (R5) | HE (X4/R5) | UG273 (R5) clade A | US2 (R5) clade B | DJ259 (R5) clade C | ETH2220 (R5) clade C | UG270 (X4) clade D | BCF06 (X4) | ROD (X4/R5) | |

| OAAa | 19 | 21 | 60 | 25 | 27 | 44 | 23 | 32 | 29 | 19 |

| OPAa | 8 | 31 | 14 | 9 | 57 | 57 | 18 | 13 | 6 | 25 |

| CV-Na | 38 | 22 | ND | 127 | 16 | 21 | ND | 29 | 14 | ND |

| MVNa | 8 | 22 | ND | 9 | 2 | 167 | ND | 48 | >350 | >262 |

| 2G12 mAbb | 140 | 3710 | ND | 18 | 40 | >50 000 | ND | >20 000 | >20 000 | >50 000 |

ND, not determined.

aIC50 or compound concentration in nM required to inhibit viral p24 Ag (for HIV-1) or p27 Ag (for HIV-2) production by 50% in PBMCs. Mean IC50 values from two to seven independent donor experiments are shown.

bIC50 or compound concentration in ng/mL required to inhibit viral p24 Ag (for HIV-1) or p27 Ag (for HIV-2) production by 50% in PBMCs.

In addition, OAA and OPA were evaluated for cellular cytotoxicity in MT-4 cells and PBMCs using the MTS/PES cellular viability method. OPA was more toxic than OAA, displaying CC50s of 0.17 μM and 0.51 μM in MT-4 cells, respectively and 1 μM for OPA and >7 μM for OAA in PBMCs (data not shown).

Effect of OAA and OPA on HIV-1-induced syncytium formation

Sexual transmission of HIV not only involves infection by cell-free viruses but cell-to-cell transmission by donor HIV-infected T cells also seems to be important.32 HIV-infected cells frequently express high amounts of viral glycoproteins on their cell surfaces and CBAs are able to avidly bind to these viral glycoproteins and inhibit syncytium (or giant cell) formation between infected cells and uninfected CD4+ T cells. Here, HIV-1-infected HUT-78 T cells were cultured with uninfected CD4+ SupT1 T cells and the inhibitory activity of OAA and OPA in giant cell formation assays was determined (Figure S1). OAA and OPA inhibited this process in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50s of 19 ± 2 and 13 ± 3 nM for OAA and OPA, respectively (Figure 1b). These values are comparable to those observed in replication assays employed for detecting anti-HIV activity, as described above.

Effect of OAA and OPA on the capture of HIV-1 by Raji/DC-SIGN cells and on subsequent virus transmission to uninfected CD4+ T cells

Another important potential HIV transmission pathway is the capture of HIV by the DC-SIGN receptor of dendritic cells followed by a very efficient transmission of the virus to CD4+ T cells.33 As a model for this transmission pathway we used the Raji cell line, transfected with the DC-SIGN receptor (Raji/DC-SIGN). OAA and OPA were able to inhibit the capture of R5/X4 HIV-1 strain HE by DC-SIGN with IC50s of 56 ± 18 and 22 ± 10 nM, respectively (Figure 1c). In addition, we investigated whether these CBAs can block the transmission of virus to CD4+ T cells when captured by DC-SIGN: Raji/DC-SIGN cells were pre-incubated with HIV-1 first and then cocultivated with OAA or OPA pre-incubated target T cells. Both CBAs inhibited this viral transmission pathway with IC50s of 27 ± 12 nM for OAA and 6 ± 0.4 nM for OPA (Figure 1d).

Antiviral activity of OAA and OPA against CBA-resistant viruses

To gain insight into whether HIV infection was prevented by OAA and OPA in a similar manner as found for other CBAs, we tested whether they were active against several CBA-resistant viruses. In cell culture, HIV-1 NL4.3MVNres virus and HIV-1 NL4.32G12res virus were selected under the pressure of MVN and 2G12 mAb in our laboratory.15,27 The NL4.3MVNres virus was selected after 41 cell culture passages and up to four mutations in gp120 were observed in N-glycosylation motifs for high-mannose-type glycans: Asn295, Asn339, Asn386 and Asn392, in which the glycosylation motif of 295NCT297 was mutated to 295NCI297. Sequencing revealed the glycosylation motif at 339NNT341 to be a mixture of 339NNT341/339NNI341 and the Asn386 position to be a mixture of Asn386 and Lys386; Asn332 was found to be changed to Asp332.15 The NL4.32G12res virus was already obtained after six passages and exhibited a single loss of glycan via the mutation at Asn295 (Asn295Lys).27 The susceptibility of NL4.3MVNres virus and NL4.32G12res virus to OAA and OPA was evaluated and compared with the susceptibility of the wild-type NL4.3 virus. As presented in Table 2, OAA and OPA retained their antiviral activity towards both the HIV-1 NL4.3MVNres and NL4.32G12res strains. MVN was also equally active against the NL4.32G12res virus. In contrast, the 2G12 mAb completely lost activity against the NL4.32G12res virus as well as the NL4.3MVNres virus as reported previously.15 GRFT inhibited wild-type HIV-1 IIIB replication with an IC50 of 11 ± 5 pM and the selected GRFT-resistant strains (IIIBGRFTres) were able to grow in the presence of >148.1 nM lectin (>11 000-fold resistance). This strain lost N-linked glycans at five positions: Asn230, Asn234, Asn295, Asn386 and Asn448. Of these, Asn234, Asn295 and Asn448 mutations were reported previously to be involved in GRFT resistance.7,34 Here again, OAA and OPA retained their antiviral potency against this HIV-1 IIIBGRFTres virus, highlighting the unique gp120 interaction by OAA and OPA, since no cross-resistance was observed against these three selected CBA-resistant HIV-1 strains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Susceptibility profile of wild-type (WT), MVN-resistant, 2G12-resistant and GRFT-resistant HIV-1 strains to OAA, OPA, MVN and 2G12 mAb

| Agent | IC50 (nM)a |

Fold resistance/susceptibilityb | IC50 (nM)a | Fold resistance/susceptibilityb | IC50 (nM)a |

Fold resistance/ susceptibilityb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL4.3 WT | NL4.3MVNres | NL4.32G12res | IIIB WT | IIIBGRFTres | ||||

| OAA | 24 ± 5 | 36 ± 4 | 2 | 9 ± 2 | 3* | 12 ± 4 | 21 ± 11 | 2 |

| OPA | 18 ± 2 | 39 ± 22 | 2 | 10 ± 3 | 2* | 17 ± 3 | 16 ± 8 | 1 |

| MVN | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 548 ± 270 | 228 | 6 ± 2 | 2.5 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 12 ± 6 | 4 |

| 2G12 mAbc | 377 ± 67 | >25 000 | >66 | >25 000 | >66 | 657 ± 122 | >25 000 | >35 |

aIC50 or drug concentration in nM required to inhibit virus replication in MT-4 cells by 50%. IC50s shown are the mean ± SEM from 3–10 separate experiments.

bValues represent the degree (fold) of resistance or susceptibility (indicated by an asterisk) of the test agents compared with wild-type virus.

cIC50 or drug concentration in ng/mL required to inhibit virus replication in MT-4 cells by 50%.

Effect of OAA and OPA on the binding of the 2G12 mAb to gp120 on HIV-1-infected MT-4 cells

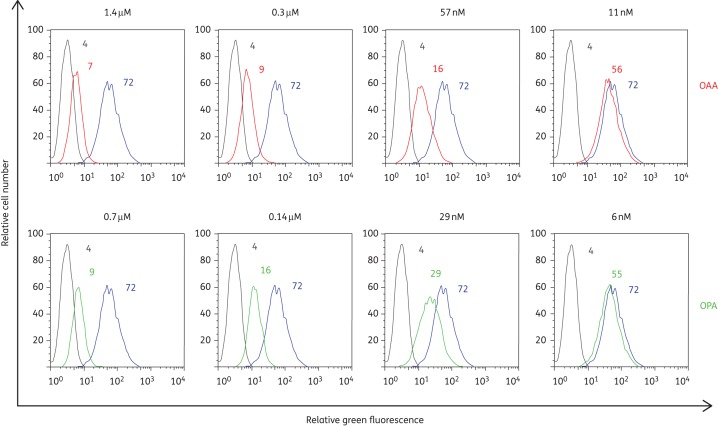

It has been reported that the epitope recognized by OAA and OPA on Man-8/9 is the central α3,α6-mannopentaose (Manα(1-3)[Manα(1-3)[Manα(1-6]Manα(1-6)]Man) core of Man-8/9.21 Here, we investigated whether these CBAs are able to inhibit the binding of the neutralizing Manα(1-2)Man-specific 2G12 mAb. In these experiments, we used HIV-1-infected MT-4 cells that were pre-incubated with several concentrations of OAA and OPA, followed by 2G12 mAb binding experiments using FITC-conjugated RaH (Figure 2). Both CBAs inhibited 2G12 mAb binding to MT-4 cells infected with HIV-1 NL4.3 equally well, with mean IC50s (±SEM) of 21 ± 3 and 19 ± 4 nM for OAA and OPA, respectively.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of 2G12 mAb binding to HIV-1 NL4.3-infected MT-4 cells by OAA and OPA. MT-4 cells infected with HIV-1 strain NL4.3 were incubated with 2G12 mAb in the absence (blue curves) or presence of various concentrations of OAA (red curves) or OPA (green curves). The light grey curves represent the background fluorescence. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for the different incubation conditions are indicated in each histogram. One representative experiment out of three is shown.

Interaction and binding kinetics of OAA and OPA with HIV-1 gp120

The interaction and binding kinetics of OAA and OPA with HIV-1 gp120 were thoroughly investigated using SPR and compared with three other well-described CBAs (2G12 mAb, HHA and GRFT). Figure 3(a) illustrates the interaction of each CBA with immobilized gp120 at the indicated concentrations. Single-cycle kinetics was performed using serial 2-fold dilutions of each CBA. As summarized in Table 3, OPA exhibits the highest affinity for gp120, with an apparent KD value of 0.08 ± 0.01 nM. OAA, GRFT and HHA exhibited comparable apparent KD values ranging between 0.58 and 0.75 nM. The weakest gp120-binding molecule in this assay appeared to be 2G12 mAb (KD of 13.1 ± 3.2 nM).

Figure 3.

Interactions of CBAs with gp120 measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The test CBAs (OAA, OPA, 2G12 mAb, GRFT and HHA) were injected over the surface-bound gp120 at the indicated concentrations (a). Competition between 2G12 mAb (magenta); HHA (red), GRFT (green) with OAA (b) or OPA (c) for the binding to HIV-1 gp120. OAA was injected (first arrow) followed after ∼120 s by injection of OAA in the presence of another CBA (second arrow). Competition between OAA (magenta), OPA (green) with 2G12 mAb (d), HHA (e), GRFT (f). 2G12 mAb, HHA and GRFT were injected (first arrow) followed after ∼120 s by injection of 2G12 mAb, HHA or GRFT in the presence of OAA or OPA (second arrow). The blue (OAA) and red (OPA) curves indicate the injection of each CBA individually. One representative experiment out of two to three experiments is shown.

Table 3.

SPR binding kinetics for the interaction of OAA, OPA, GRFT, HHA and 2G12 mAb with gp120

| Agents | rgp120 IIIBa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| KD (nM)b | kon (1/Ms)b | koff (1/s)b | |

| OAA | 0.58 ± 0.16 | (5.72 ± 1.04)E + 05 | (3.14 ± 0.87)E − 04 |

| OPA | 0.08 ± 0.01 | (1.28 ± 0.12)E + 06 | (1.07 ± 0.04)E − 04 |

| GRFT | 0.69 ± 0.01 | (2.62 ± 0.02)E + 06 | (1.80 ± 0.01)E − 03 |

| HHA | 0.75 ± 0.04 | (8.03 ± 0.27)E + 05 | (6.04 ± 0.09)E − 04 |

| 2G12 mAb | 13.1 ± 3.2 | (5.49 ± 0.51)E + 04 | (7.02 ± 1.11)E − 04 |

aRecombinant gp120 produced in the Baculovirus expression system.

bKD, apparent dissociation constant; kon, association (on) rate constant; koff, dissociation (off) rate constant. Mean values ± SEM from two to four independent experiments are shown.

Competition of HHA, 2G12 mAb and GRFT with OAA and OPA for gp120 binding

In the next set of experiments, we investigated whether HHA, 2G12 mAb and GRFT are still able to interact with gp120 when gp120 is already bound to OPA or OAA. These data are presented in Figure 3. OAA (500 nM; >800-fold its KD; blue curves) was administered to immobilized gp120 (first arrow) and immediately at the end of the association phase at ∼120 s, OAA was injected in the presence of HHA (250 nM; >300-fold its apparent KD; red curves), GRFT (250 nM; >300-fold its apparent KD; green curves) or 2G12 mAb (250 nM; 20-fold its apparent KD; magenta curves) (second arrow). The α(1,2)-mannose-specific CBA GRFT as well as the α(1,3)/α(1,6)-mannose-specific CBA HHA was still able to bind to OAA-saturated gp120; however, binding was not as pronounced as observed with unsaturated gp120 (Figure 3a). In contrast, 2G12 mAb exhibited only very weak binding, resulting in a low and flattened curve (Figure 3b). These mAb 2G12 data are in agreement with our flow cytometry data described above. Comparable results were observed for OPA alone (250 nM; >1000-fold its apparent KD; blue curve; first arrow) and each dual injection (second arrow; Figure 3c), where HHA and GRFT interact with OPA-saturated gp120 (however under less optimal conditions) as observed with unsaturated gp120 (Figure 3a). The mAb 2G12, in the presence of OPA, was completely devoid of gp120 binding, as evidenced by superposition of the magenta and blue curves (Figure 3c).

We also tested whether OAA and OPA were still able to interact with gp120 in the presence of 2G12 mAb, HHA and GRFT. As shown in Figure 3(d), saturating concentrations of 2G12 mAb (250 nM) did not affect the binding with saturating concentrations of OAA (500 nM) and OPA (250 nM), since the height of the response is identical with or without 2G12 mAb (blue versus magenta curves and red versus green curves). When gp120 was saturated with HHA (Figure 3e) or GRFT (Figure 3f) (both at 250 nM), we observed that OPA was still able to interact with gp120 (green curves), but weakly compared with unsaturated gp120 (blue curves), while OAA exhibited no significant additional interaction (magenta curves).

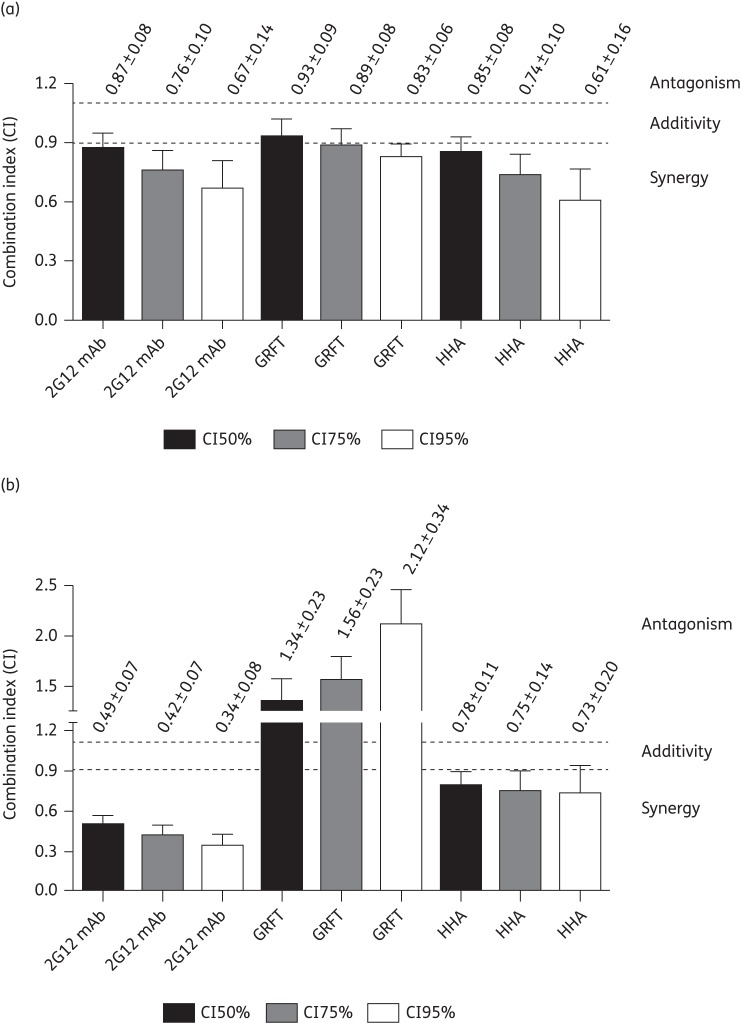

Evaluation of two-drug combination studies using OAA and OPA

Given the unique carbohydrate-binding properties of OAA and OPA, it was of considerable interest to test for potential synergistic/antagonistic effects between these CBAs and other members CBAs of the same class. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the EC50 and EC95 values for treatment with OAA, OPA, 2G12 mAb, GRFT and HHA for HIV-1 NL4.3 replication in MT-4 cells. After establishing the initial concentrations at which each individual inhibitor exhibited activity, we tested the effects of OAA and OPA when added to 2G12 mAb, GRFT and HHA, with each combination diluted at a constant ratio. All combinations resulted in a significant dose reduction index (DRI) at the EC50 level (P < 0.05), except for the combination OPA/GRFT. When GRFT was combined with OAA and OPA, non-significant DRIs were noted at EC95, requiring an increase in GRFT concentrations (DRI < 1) in combination with OPA (Table 5). Figure 4 provides a summary of the combined effects of OAA (a) and OPA (b), gauged by the CI. For the OAA/2G12 mAb and OAA/HHA combinations, increased synergy levels with increasing doses were observed (CIs ranging from 0.87 to 0.61), while the effect of OAA with GRFT was additive at the EC50 (CI of 0.93) and became slightly/moderately synergistic at EC75 and EC95 (Figure 4a). The highest levels of synergy with OPA were observed for the combination with 2G12 mAb (CIs ranging from 0.49 to 0.34). Moderate synergy was observed with HHA (CIs ranging from 0.78 to 0.73) and increasing levels of antagonism were seen with increasing doses of OPA/GRFT (Figure 4b).

Table 4.

EC50 and dose reduction index (DRI) for CBAs in combination with OAA and OPA evaluated by HIV-1 NL4.3 replication in MT-4 cells

| CBA1 | CBA2 | CBA1 concentration |

DRIa | P value | CBA2 concentration |

DRIa | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | alone | combined | ||||||

| OAA | 2G12 mAbb | 15.4 ± 2.4 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 3.3 | 0.0025 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 1.9 | 0.0001 |

| OAA | GRFTc | 13.4 ± 2.8 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.0388 | 10.0 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.0143 |

| OAA | HHAd | 11.8 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.0014 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.0003 |

| OPA | 2G12 mAbb | 10.8 ± 1.8 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 5.6 | 0.0083 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 3.1 | 0.0202 |

| OPA | GRFTc | 9.7 ± 2.8 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 2.6 | 0.0764 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.7621 |

| OPA | HHAd | 9.5 ± 2.4 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.0500 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.98 ± 0.07 | 3.0 | <0.0001 |

The EC50s ± SEM of three to six independent experiments are shown.

aDose reduction index (DRI): reduction in CBA concentration after combination with the other CBA compared with single CBA treatment.

b2G12 mAb values are expressed as μg/mL.

cGRFT values are expressed as pM.

dHHA values are expressed as nM.

Table 5.

EC95 and dose reduction index (DRI) for CBAs in combination with OAA and OPA evaluated by HIV-1 NL4.3 replication in MT-4 cells

| CBA1 | CBA2 | CBA1 concentration |

DRIa | P value | CBA2 concentration |

DRIa | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | alone | combined | ||||||

| OAA | 2G12 mAbb | 50.5 ± 13.8 | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 3.7 | 0.0288 | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 | 0.003 |

| OAA | GRFTc | 52.9 ± 16.9 | 18.1 ± 4.3 | 2.9 | 0.0921 | 33.1 ± 6.6 | 14.9 ± 3.6 | 2.2 | 0.0512 |

| OAA | HHAd | 43.8 ± 7.8 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.0038 | 12.2 ± 2.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.0009 |

| OPA | 2G12 mAbb | 41.5 ± 11.3 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | 6.4 | 0.0377 | 8.4 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.0111 |

| OPA | GRFTc | 67.9 ± 25.2 | 21.5 ± 5.4 | 3.2 | 0.1096 | 24.6 ± 5.4 | 35.4 ± 8.9 | 0.7 | 0.3303 |

| OPA | HHAd | 22.7 ± 3.8 | 9.6 ± 1.5 | 2.4 | 0.0179 | 12.0 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 4.5 | <0.0001 |

The EC95s ± SEM of three to six independent experiments are shown.

aDose reduction index (DRI): reduction in CBA concentration after combination with the other CBA compared with single CBA treatment.

b2G12 mAb values are expressed as μg/mL.

cGRFT values are expressed as pM.

dHHA values are expressed as nM.

Figure 4.

Effects of OAA (a) and OPA (b) in two-drug combinations at three different HIV-1 inhibition levels. Combination indices (CIs) <0.9 indicate synergy, 0.9 < CI < 1.1 indicates additivity and CIs >1.1 indicate antagonism. The degree of synergy is further divided into strong synergy (CIs <0.3), synergy (0.3 < CI < 0.7), moderate synergy (0.7 < CI < 0.85) and slight synergy (0.85 < CI < 0.9). The degree of antagonism is further divided into slight antagonism (1.1 < CI < 1.20), moderate antagonism (1.20 < CI < 1.45) and antagonism (1.45 < CI < 3.3). The CIs represent the mean ± SEM from three to six independent experiments.

Evaluation of the stimulatory effects of OAA and OPA on PBMCs

One of the major concerns about antiviral lectins relates to their potential mitogenic properties. Recently, we reported that the potent anti-HIV lectin CV-N markedly stimulated PBMCs.35 We therefore carried out a thorough investigation of the potential cell-activating properties of OAA and OPA. In all of our experiments, the mitogenic lectin PHA was included as a positive control. Freshly isolated PBMCs were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of OAA and OPA for 72 h and the expression of the activation markers CD25, CD69 and HLA-DR of the CD4+ T cells was measured using flow cytometry. In unstimulated PBMCs, the mean SEM percentage value of CD4+/CD25+ cells was 6.32% ± 0.52%. Treatment of PBMCs with 2 μg/mL OAA (144 nM), OPA (72 nM) or PHA significantly increased the amount of CD4+/CD25+ cells to 47% ± 5% (P < 0.05), 21% ± 2% (P < 0.05) and 37% ± 5% (P < 0.05), respectively. At 29 nM (0.4 μg/mL), OAA still exhibited a significant effect (P < 0.05) on CD25 expression levels, while at lower concentrations OPA had no effect (Figure 5a). Both OAA and OPA at high concentrations affected the expression of the early and late activation markers CD69 (Figure 5b) and HLA-DR (Figure 5c), respectively. This effect was more pronounced for OAA than for OPA and the percentages of CD4+/CD69+ cells and CD4+/HLA-DR+ cells were similar to those measured after stimulation with PHA, for concentrations of 2 μg/mL of each CBA.

Figure 5.

Induction of cellular activation marker expression by OAA and OPA. PBMCs were cultured and incubated in the presence of various concentrations of OAA, OPA and PHA at 37°C for 3 days. The PBMCs were analysed using flow cytometry for their expression of cellular activation markers with PE-conjugated anti-CD25 (a), anti-CD69 (b) or anti-HLA-DR (c) mAbs in combination with PerCP-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb. Data represent mean % ± SEM for four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (**P < 0.005) for comparison with untreated PBMCs (Student's t-test). NC, negative control.

Discussion

Recently, Koharudin et al.23 reported structural and carbohydrate-binding studies for the OAAH lectin family. In addition, it was noted that the antiviral activity of a designer OAA/PFA hybrid protein, designated OPA, in which the two parental proteins are connected between the C-terminus of OAA and the N-terminus of PFA, was higher than that of OAA or PFA alone. Since only minor conformational changes from the original OAA and PFA structures were expected in the hybrid OPA protein, this was a surprising result. As OAA and OPA were tested only in a single-cycle HIV-1 infectivity assay using a luciferase reporter cell line to quantify the antiviral activity of the CBAs against an X4 virus in the previous study,23 we tested these CBAs in various replication assays using different cell lines and a wide variety of HIV-1 and HIV-2 virus strains, as well as HIV-1 clinical isolates, representing diverse subtypes with different coreceptor tropisms. With the antiviral assays we confirmed that OPA exhibited higher antiviral activity than OAA, using our X4 laboratory strain with the X4/R5 HIV and clinical isolates of subtype A, D and the subtype of group O. However, for other viruses, such as BaL and HIV-2, as well as clinical isolates of subtypes B and C, OPA was not superior in inhibiting viral replication compared with OAA. Interestingly, in contrast to MVN and 2G12 mAb, OAA and OPA were active against an HIV-1 group O isolate and against HIV-2.

At present, CBAs are considered to represent potential topical microbicides (e.g. vaginal/rectal gel or intravaginal system) as recombinant forms can be produced in high amounts and also be combined with various classes of clinically approved and experimental anti-HIV agents.14,36,37 They block HIV entry, thereby preventing the infection of susceptible target cells. OAA and OPA were found to inhibit infection by a broad range of HIV-1 clinical isolates and their antiviral activity was comparable to that of CV-N, one of the best-studied antiviral CBAs to date for microbicidal applications.8,35,38–41 So far, many of the HIV isolates tested exhibit preference for the coreceptor CCR5 and HIV transmission occurs mainly through CCR5-using (R5) viruses. As shown here for several CBAs, OAA and OPA display a broader anti-HIV spectrum than MVN and 2G12 mAb.

Another benefit of CBAs as microbicides or PrEP agents derives from the fact that they prevent cell-to-cell transmission of virus via HIV-infected donor T cells. These HIV-infected cells express viral glycoproteins on their cell surface. Here, we show that OAA and OPA were able to bind to these cells and significantly inhibit syncytium formation between infected cells and uninfected CD4+ T cells. Several studies indicate the importance of viral cell-to-cell transmission in HIV pathogenesis.42–44 However, the obtained results of antiretroviral agents on the inhibitory effects on HIV cell-to-cell transmission are still an arguable point.42,44 The CBAs will likely not be absorbed because of their high molecular weight and can intercept the virus already in the vaginal/rectal lumen before it interacts with the target cells in the case of a topical microbicidal agent. At present, there are no exogenous gp120-targeted antiretrovirals available. Furthermore, in addition to infection of CD4+ T cells and macrophages via virions and donor-infected cells, DC-SIGN-directed capture of HIV-1 and transmission to CD4+ T lymphocytes is considered an important avenue of primary infection in women exposed to HIV-1 through sexual intercourse.45 Like CBAs, DC-SIGN binds to mannose-rich glycans on the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. Importantly, CBAs are capable of inhibiting the capture of HIV-1 by DC-SIGN compared with other entry inhibitors (e.g. the CCR5 inhibitor maraviroc or gp41 fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide). Indeed, after HIV-1 was already captured on Raji/DC-SIGN cells, OAA and OPA were still active and significantly inhibited the transmission of HIV-1 to CD4+ T cells.

Structurally, an important difference between these two CBAs and other lectins that are considered as potential microbicide candidates is their unique recognition motif on gp120 glycans. Most HIV-inactivating lectins recognize the reducing- or non-reducing-end mannoses of Man-8/9. For example, CV-N, MVN and 2G12 mAb bind tightly and specifically to Manα(1-2)Man-linked mannose substructures.46–50 Plant lectins derived from Hippeastrum hybrid (HHA) and Galanthus nivalis (GNA) of the Amaryllidaceae family exhibit specificity for Manα(1-3)Man or Manα(1-6)Man and Manα(1-3)Man linked di-mannose units for HHA and GNA, respectively.51,52 To date, the lectin from the rhizomes of the stinging nettle Urtica dioica (UDA) is the only plant lectin, recognizing N-acetylglucosamine, that displays pronounced and consistent anti-HIV activity.53 In contrast, OAA and OPA recognize the branched central core unit of Man-8/9 and specific binding to α3,α6-mannopentaose (Manα(1-3)[Manα(1-3)[Manα(1-6]Manα(1-6)]Man) was observed.23 This unique feature of OAA and OPA explains why these lectins are effective against both NL4.32G12res and NL4.3MVNres (and even IIIBGRFTres) viruses. On the other hand, surprisingly, these two CBAs were able to inhibit the binding of the α(1-2)Man-specific 2G12 mAb, most likely due to steric effects (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained using SPR analysis (Figure 3b and c). Given the differences in carbohydrate specificity, we performed combination studies in which OAA and OPA were combined with HHA, 2G12 mAb and GRFT in order to evaluate whether any synergy or antagonism could be observed. Previously, we had found that two members within a CBA class, when combined, had synergistic effects.54 As mentioned above, the main transmitted viruses are R5 viruses, although X4 viruses can also be transmitted.55–57 We therefore also evaluated whether CBA combinations were effective against X4 HIV-1 virus NL4.3. Previous studies had revealed that 2G12 mAb binds to the sugar on Asn295, the same unit recognized by GRFT or MVN, explaining why the binding of 2G12 mAb was inhibited by these two lectins (15 and D. Huskens and D. Schols, unpublished observations). Surprisingly, however, in two-drug combination studies, GRFT and MVN clearly exhibited a synergistic effect with 2G12 mAb on replication.50,54 Here, we observed that OAA or OPA together with 2G12 mAb also act synergistically. We believe that this synergy may be explained based on the binding kinetics of the CBAs, since 2G12 mAb binding did not affect the interaction of OAA and OPA with gp120 (Figure 3d). HHA and GRFT are still able to bind to gp120 in the presence of OAA and OPA (Figure 3b and c); however, binding is tighter to OAA if the differences in the molecular masses of OAA (∼14 kDa) and OPA (∼28 kDa) are taken into account. The observed antagonism between OPA and GRFT was quite unexpected. The simplest explanation may be that OPA binding affects the structure of gp120, lowering the affinity for GRFT and thereby reducing its antiviral activity. In particular, when HHA and GRFT are bound to gp120, OPA could still interact with gp120, as seen in the SPR traces (Figure 3e and f), although maximum binding levels were not reached. This is in contrast to OAA binding to lectin-free, native gp120, which is almost undetectable. These findings suggest that kinetic effects for CBA binding play a role in combination studies and that the PFA unit of the dimeric OPA molecule may play the predominant role in the antiviral/binding activity of OPA. This may also explain the ∼7-fold increase in the KD value between OPA and OAA (Table 3).

Unfortunately, the observed mitogenic properties of OAA and OPA represent a major obstacle when considering their use as potential microbicides (Figure 5). However, their unique binding determinants and binding kinetics towards gp120-bound glycans, compared with the other antiviral lectins described so far, render these interesting molecules for further optimization with respect to cytotoxicity and mitogenicity.

Funding

This work was supported by the KU Leuven (GOA 10/014, PF/10/018), the Foundation of Scientific Research (FWO no. G-0485-08, G-0528-12), the Foundation Dormeur, Vaduz and the CHAARM project of the European Commission and by an NIH grant to A. M. G. (GM080642).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sandra Claes, Evelyne Van Kerckhove and Eric Fonteyn for excellent technical assistance and Stephanie Gordts for final corrections to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilton JC, Doms RW. Entry inhibitors in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, et al. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–59. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, et al. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, et al. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–11. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huskens D, Schols D. Algal lectins as potential HIV microbicide candidates. Mar Drugs. 2012;10:1476–97. doi: 10.3390/md10071476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Lambson BE, et al. Mannose-rich glycosylation patterns on HIV-1 subtype C gp120 and sensitivity to the lectins griffithsin, cyanovirin-N and scytovirin. Virology. 2010;402:187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Peumans WJ, et al. Mutational pathways, resistance profile, and side effects of cyanovirin relative to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains with N-glycan deletions in their gp120 envelopes. J Virol. 2006;80:8411–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bewley CA, Cai M, Ray S, et al. New carbohydrate specificity and HIV-1 fusion blocking activity of the cyanobacterial protein MVL: NMR, ITC and sedimentation equilibrium studies. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:901–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bokesch HR, O'Keefe BR, McKee TC, et al. A potent novel anti-HIV protein from the cultured cyanobacterium Scytonema varium. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2578–84. doi: 10.1021/bi0205698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd MR, Gustafson KR, McMahon JB, et al. Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1521–30. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emau P, Tian B, O'Keefe BR, et al. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J Med Primatol. 2007;36:244–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Férir G, Palmer KE, Schols D. Synergistic activity profile of griffithsin in combination with tenofovir, maraviroc and enfuvirtide against HIV-1 clade C. Virology. 2011;417:253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Férir G, Palmer KE, Schols D. Griffithsin, alone and combined with all classes of antiretroviral drugs, potently inhibits HIV cell–cell transmission and destruction of CD4+ T cells. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 2012;4:103–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huskens D, Férir G, Vermeire K, et al. Microvirin, a novel α(1,2)-mannose-specific lectin isolated from Microcystis aeruginosa, has comparable anti-HIV-1 activity as cyanovirin-N, but a much higher safety profile. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24845–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kouokam JC, Huskens D, Schols D, et al. Investigation of griffithsin's interactions with human cells confirms its outstanding safety and efficacy profile as a microbicide candidate. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong S, Fan J, Kitazato K. The antiviral protein cyanovirin-N: the current state of its production and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:805–12. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori T, O'Keefe BR, Sowder RC, II, et al. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9345–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato Y, Murakami M, Miyazawa K, et al. Purification and characterization of a novel lectin from a freshwater cyanobacterium, Oscillatoria agardhii. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;125:169–77. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(99)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y, Okuyama S, Hori K. Primary structure and carbohydrate binding specificity of a potent anti-HIV lectin isolated from the filamentous cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11021–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koharudin LM, Gronenborn AM. Structural basis of the anti-HIV activity of the cyanobacterial Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin. Structure. 2011;19:1170–81. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T, Hori K. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel anti-HIV lectin from cultured cyanobacterium, Oscillatoria agardhii. Fisher Sci. 2009;75:743–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koharudin LM, Kollipara S, Aiken C, et al. Structural insights into the anti-HIV activity of the Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin homolog lectin family. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33796–811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koharudin LM, Furey W, Gronenborn AM. Novel fold and carbohydrate specificity of the potent anti-HIV cyanobacterial lectin from Oscillatoria agardhii. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1588–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kehr JC, Zilliges Y, Springer A, et al. A mannan binding lectin is involved in cell–cell attachment in a toxic strain of Microcystis aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:893–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauwels R, Andries K, Desmyter J, et al. Potent and selective inhibition of HIV-1 replication in vitro by a novel series of TIBO derivatives. Nature. 1990;343:470–4. doi: 10.1038/343470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huskens D, Van Laethem K, Vermeire K, et al. Resistance of HIV-1 to the broadly HIV-1-neutralizing, anti-carbohydrate antibody 2G12. Virology. 2007;360:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoorelbeke B, Huskens D, Férir G, et al. Actinohivin, a broadly neutralizing prokaryotic lectin, inhibits HIV-1 infection by specifically targeting high-mannose-type glycans on the gp120 envelope. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3287–301. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00254-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose–effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drug or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–81. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hladik F, McElrath MJ. Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:447–57. doi: 10.1038/nri2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattentau Q. Avoiding the void: cell-to-cell spread of human viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:815–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang X, Jin W, Griffin GE, et al. Removal of two high-mannose N-linked glycans on gp120 renders human immunodeficiency virus 1 largely resistant to the carbohydrate-binding agent griffithsin. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2367–73. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huskens D, Vermeire K, Vandemeulebroucke E, et al. Safety concerns for the potential use of cyanovirin-N as a microbicidal anti-HIV agent. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2802–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Keefe BR, Vojdani F, Buffa V, et al. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Férir G, Vermeire K, Huskens D, et al. Synergistic in vitro anti-HIV type 1 activity of tenofovir with carbohydrate-binding agents (CBAs) Antiviral Res. 2011;90:200–4. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.03.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bewley CA, Gustafson KR, Boyd MR, et al. Solution structure of cyanovirin-N, a potent HIV-inactivating protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:571–8. doi: 10.1038/828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagenaur LA, Sanders-Beer BE, Brichacek B, et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in macaques by a live recombinant Lactobacillus. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:648–57. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai CC, Emau P, Jiang Y, et al. Cyanovirin-N gel as a topical microbicide prevents rectal transmission of SHIV89.6P in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:535–41. doi: 10.1089/088922203322230897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai CC, Emau P, Jiang Y, et al. Cyanovirin-N inhibits AIDS virus infections in vaginal transmission models. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:11–8. doi: 10.1089/088922204322749459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sigal A, Kim JT, Balazs AB, et al. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV permits ongoing replication despite antiretroviral therapy. Nature. 2011;477:95–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Portillo A, Tripodi J, Najfeld V, et al. Multiploid inheritance of HIV-1 during cell-to-cell infection. J Virol. 2011;85:7169–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00231-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agosto LM, Zhong P, Munro J, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapies are effective against HIV-1 cell-to-cell transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hladik F, Doncel GF. Preventing mucosal HIV transmission with topical microbicides: challenges and opportunities. Antiviral Res. 2010;88(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrientos LG, Matei E, Lasala F, et al. Dissecting carbohydrate-cyanovirin-N binding by structure-guided mutagenesis: functional implications for viral entry inhibition. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2006;19:525–35. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bewley CA. Solution structure of a cyanovirin-N:Manα1-2Manα complex: structural basis for high-affinity carbohydrate-mediated binding to gp120. Structure. 2001;9:931–40. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Botos I, O'Keefe BR, Shenoy SR, et al. Structures of the complexes of a potent anti-HIV protein cyanovirin-N and high mannose oligosaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34336–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, et al. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science. 2003;300:2065–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shahzad-ul-Hussan S, Gustchina E, Ghirlando R, et al. Solution structure of the monovalent lectin microvirin in complex with Man(α)(1-2)Man provides a basis for anti-HIV activity with low toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20788–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.232678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Damme EJ, Goldstein IJ, Peumans WJ. A comparative study of mannose-binding lectins from the Amaryllidaceae. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:509–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Damme EJ, Peumans WJ, Pusztai A, et al. Handbook of Plant Lectins: Properties and Biomedical Applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Hatse S, et al. Carbohydrate-binding agents cause deletions of highly conserved glycosylation sites in HIV GP120: a new therapeutic concept to hit the Achilles heel of HIV. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41005–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Férir G, Huskens D, Palmer KE, et al. Combinations of griffithsin with other carbohydrate-binding agents demonstrate superior activity against HIV type 1, HIV type 2, and selected carbohydrate-binding agent-resistant HIV type 1 strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1513–23. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arrighi JF, Pion M, Garcia E, et al. DC-SIGN-mediated infectious synapse formation enhances X4 HIV-1 transmission from dendritic cells to T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1279–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chalmet K, Dauwe K, Foquet L, et al. Presence of CXCR4-using HIV-1 in patients with recently diagnosed infection: correlates and evidence for transmission. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:174–84. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gianella S, Mehta SR, Young JA, et al. Sexual transmission of predicted CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 likely originating from the source partner's seminal cells. Virology. 2012;434:2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.