Abstract

According to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, the lepidic predominant pattern consists of 3 subtypes: adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma. We reviewed tumor slides from 1038 patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma, recording the percentage of each histologic pattern and measuring invasive tumor size. Tumors were classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification: 2 were AIS, 34 MIA, and 103 lepidic predominant invasive. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) was used to estimate the probability of recurrence. Patients with AIS and MIA experienced no recurrences. Patients with lepidic predominant invasive tumors had a lower risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 8%) than non-lepidic predominant tumors (n=899; 19%; P=0.003). Patients with >50% lepidic pattern tumors experienced no recurrences (n=84), those with >10%–50% lepidic pattern tumors had an intermediate risk of recurrence (n=344; 5-year CIR, 12%), and those with ≤10% lepidic pattern tumors had the highest risk (n=610; 22%; P<0.001). CIR was lower for patients with ≤2 cm tumors than for those with >2–3 cm tumors (for both total and invasive tumor size), with the difference more pronounced for invasive tumor size (5-year CIR, 13% vs. 21% [total size; P=0.022] and 12% vs. 27% [invasive size; P<0.001]). Most patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma who experienced a recurrence had potential risk factors, including sublobar resection with close margins (≤0.5 cm; n=2), 20%–30% micropapillary component (n=2), and lymphatic or vascular invasion (n=2). It therefore may be possible to identify lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas that carry a low or high risk of recurrence.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Lepidic, Adenocarcinoma in situ, Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

The 2004 World Health Organization classification of lung cancer defines bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) as a noninvasive tumor that spreads along alveolar structures.1 The newly proposed International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), American Thoracic Society (ATS), and European Respiratory Society (ERS) international multidisciplinary lung adenocarcinoma classification recommends discontinuing the use of the term BAC, as tumors formerly referred to as BAC can now be classified as five different entities. The noninvasive growth pattern previously called BAC is now called lepidic pattern.2 The origin of the term lepidic was recently reviewed and its origins traced to Dr. John George Adami in 1902.3 Multiple studies have shown that patients with pure lepidic (noninvasive) tumors have 100% 5-year disease-free survival.4–7 A smaller group of studies has shown that patients with lepidic predominant minimally invasive (≤5 mm) tumors have nearly 100% survival.8–10 In addition, lepidic predominant invasive tumors have been correlated with favorable prognosis in patients with resected lung adenocarcinoma.11–13 On the basis of these results, the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification includes 3 proposed adenocarcinoma subtypes with lepidic predominant components: (1) adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), (2) minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and (3) nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma.14

Several reports on computed tomography (CT) screening for lung adenocarcinoma have suggested that there is a correlation between ground-glass opacity (an air density–containing area on CT) and lepidic growth pattern.15–17 With the recent randomized trials assessing low-dose CT screening for lung cancer,18–20 it is anticipated that an increasing number of patients will be diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic growth at an early stage, which may contribute to reduced disease-specific mortality from lung cancer in the future. These tumors are likely to be cured if completely resected, so they are of particular interest to thoracic surgeons who may be considering limited resection over standard lobectomy to treat them. Although most cases of AIS and MIA will be cured if completely resected, a small percentage of lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas will recur, and it would be of great value to surgeons to be able to identify risk factors for recurrence in these tumors. Therefore, it is important to improve the clinical characterization of early-stage lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic predominant pattern. However, no large studies have investigated the clinical significance of the 3 lepidic predominant subtypes as defined by the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification.

We herein report clinicopathologic and prognostic findings from tumors with lepidic growth pattern. The aim of this study was to clarify the clinical significance of lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic growth and to identify factors of poor prognosis related to lepidic predominant invasive tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board (WA0269-08). We reviewed all patients with pathologic stage I solitary lung adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical resection at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center between 1995 and 2009. Tumor slides from 1038 patients were available for histologic evaluation. Clinical data were collected from the prospectively maintained Thoracic Service lung adenocarcinoma database. Disease stage was based on the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging Manual.21 Subsets of the cases in this study have been previously published in manuscripts focused on architectural grading,22 histologic classification,23 nuclear grading,24 and the immune microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma.25

Histologic Evaluation

All available hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides were reviewed by 2 pathologists (K.K. and W.D.T.) who were blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes, using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a standard 22-mm diameter eyepiece. Each tumor was reviewed using comprehensive histologic subtyping, and the percentage of each histologic pattern was recorded in 5% increments. The predominant pattern was defined as the morphologic subtype present in the greatest proportion.2

Total tumor size and invasive tumor size were measured. Total tumor size was recorded on gross finding by use of a ruler. Invasive tumor size was measured 2 ways: (1) in cases where the tumor was small and the invasive area could be measured on a single slide, the invasive size was measured at ×20 or ×40 magnification on the microscope using a ruler; and (2) in cases where the tumor was large and the invasive area could not be measured on a single slide, the invasive size was calculated by multiplying the total tumor size by the percentage of invasive component.23

The following histologic factors were also investigated: (1) visceral pleural invasion, which was classified as absent (PL0) or present (PL1 and PL2)21; (2) lymphatic and vascular invasion; and (3) tumor necrosis.

Tumors were classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification as (1) AIS, (2) MIA, or invasive adenocarcinoma, which was further subclassified as (3) nonmucinous lepidic predominant, (4) acinar predominant, (5) papillary predominant, (6) micropapillary predominant, or (7) solid predominant. Variants included (8) invasive mucinous and (9) colloid predominant adenocarcinoma.2

The IASLC/ATS/ERS classification includes 3 subtypes with lepidic predominant features: (1) AIS, (2) MIA, and (3) nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma. The definitions of these histologic subtypes are summarized in Table 1. Tumor invasion was defined as the following: (1) histologic pattern other than lepidic (acinar, papillary, micropapillary, or solid), (2) active myofibroblastic stroma correlated with invasive tumor cells, and (3) presence of lymphatic, vascular, or pleural invasion. AIS is defined as a ≤3 cm tumor with a pure lepidic pattern (Figure 1) but without lymphatic, vascular, or pleural invasion or tumor necrosis. MIA is defined as a ≤3 cm tumor with a lepidic predominant pattern and ≤5 mm stromal invasion (Figure 2) but without lymphatic, vascular, or pleural invasion or tumor necrosis. Lepidic growth was classified into 2 patterns according to the absence or presence of an intracellular mucinous feature: nonmucinous and mucinous. AIS and MIA were further subgrouped as nonmucinous, mucinous (Figure 3), or mixed mucinous/nonmucinous.2 Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma was excluded from lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma even if the mucinous tumor cells showed predominantly lepidic pattern. Mucinous AIS and MIA were included since there is very little data published on these tumors and it is important to document that so far they also show no recurrence. Lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma is defined as a tumor that is >3 cm in total size and/or >5 mm in invasive size with a nonmucinous lepidic predominant pattern (Figure 4). Any lepidic predominant tumors with lymphatic, vascular, or pleural invasion or tumor necrosis were classified as lepidic predominant invasive tumors, rather than AIS or MIA. Tumors were classified into 3 groups according to percentage of lepidic pattern: ≤10% lepidic pattern, >10%–50% lepidic pattern, and >50% lepidic pattern.

Table 1.

Definition of Adenocarcinoma in situ, Minimally Invasive Adenocarcinoma, and Nonmucinous Lepidic Predominant Invasive Adenocarcinoma

| Subtype | Size and Invasion | Lepidic Pattern Distribution |

Lymphatic Invasion |

Vascular Invasion |

Pleural Invasion |

Tumor Necrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma in situ | ≤3 cm and no invasion | 100% | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma | ≤3 cm and ≤5 mm invasion | Predominant | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma | >3 cm and/or >5 mm invasion | Predominant | Absent or present | Absent or present | Absent or present | Absent or present |

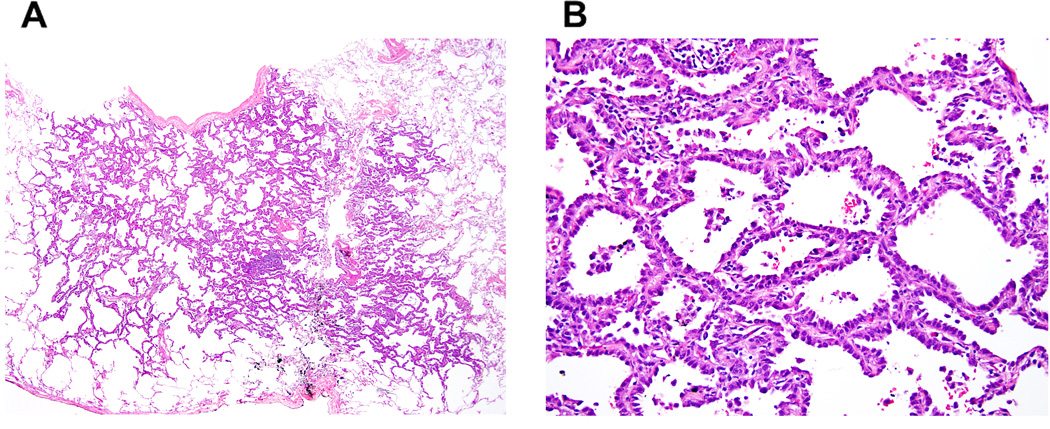

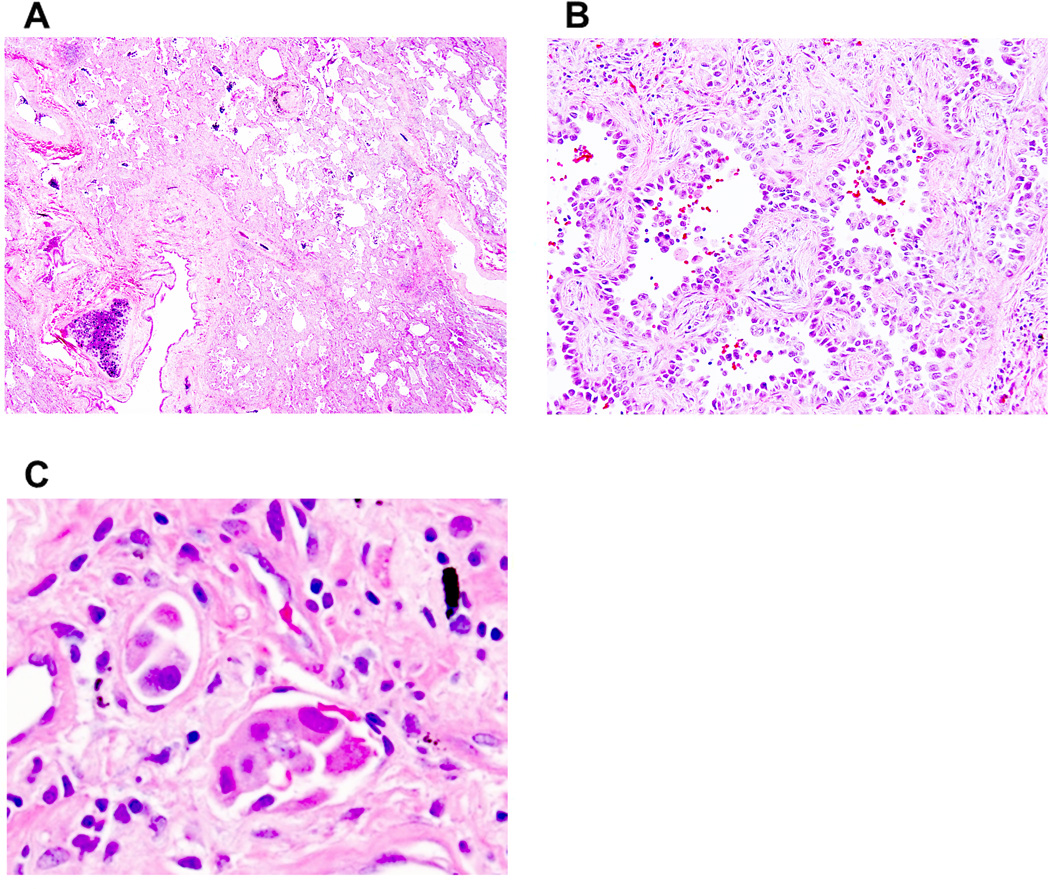

Figure 1. Adenocarcinoma in situ, nonmucinous type.

(A) A small tumor shows a pure lepidic pattern. (B) Nonmucinous tumor cells spread along alveolar walls (lepidic pattern) without invasion.

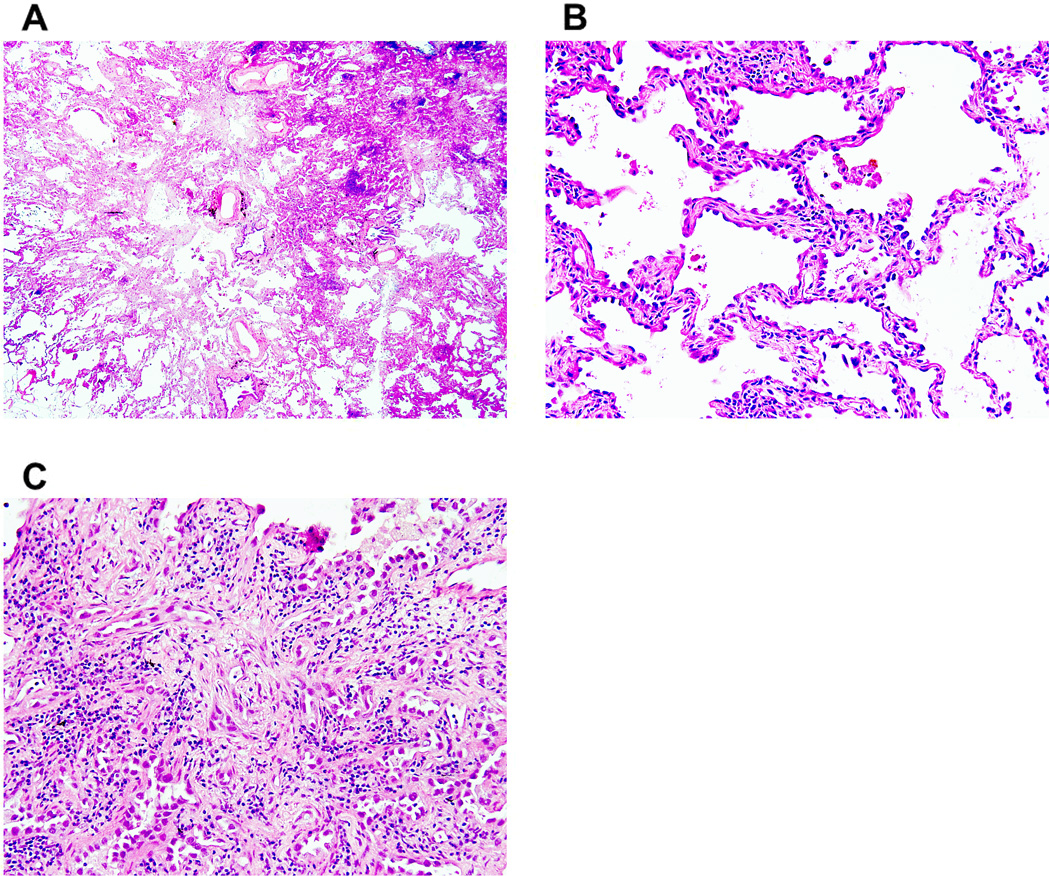

Figure 2. Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, nonmucinous type.

(A) A small tumor shows a predominant (>90%) lepidic pattern with <5 mm stromal invasion. (B) Nonmucinous tumor cells spread along alveolar walls (lepidic pattern) without invasion. (C) Small glandular tumor cells (acinar pattern) show stromal invasion with active myofibroblastic proliferation.

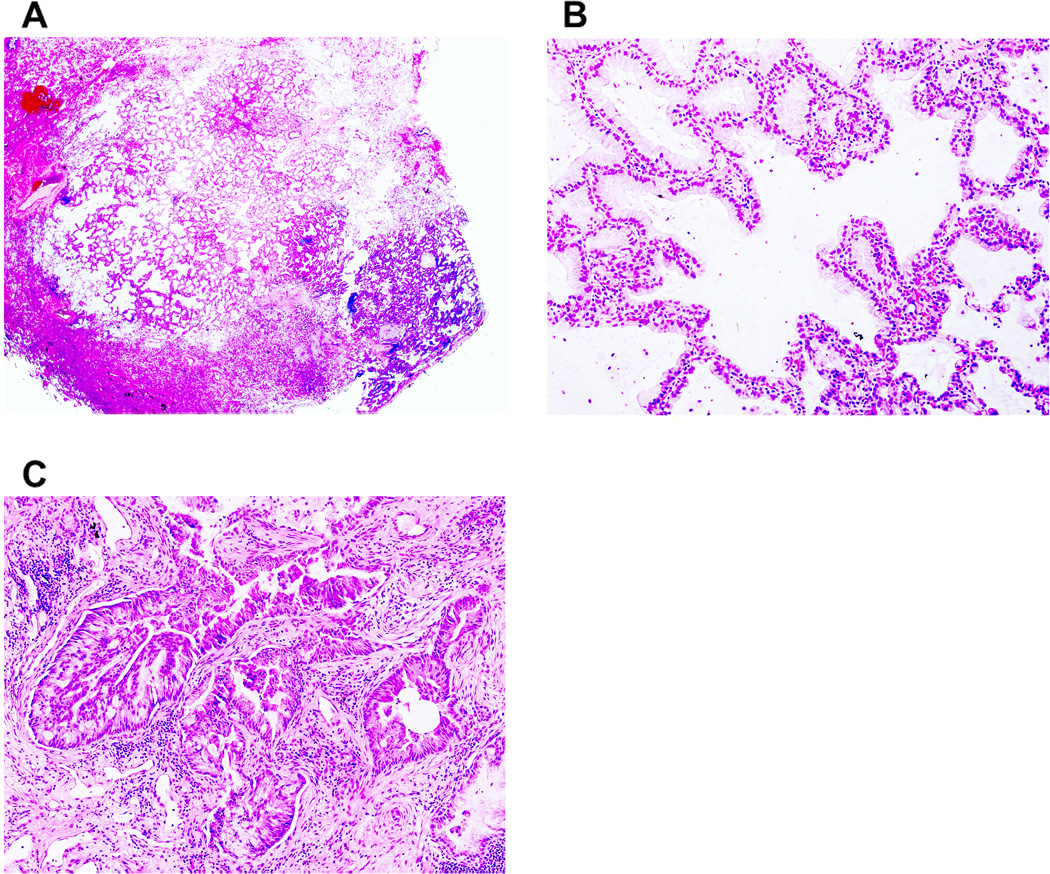

Figure 3. Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, mucinous type.

(A) A small tumor shows a predominant (>90%) lepidic pattern with <5 mm stromal invasion. (B) Mucinous tumor cells spread along alveolar walls (lepidic pattern) without invasion. (C) Fused glandular tumor cells (acinar pattern) show stromal invasion with active myofibroblastic proliferation.

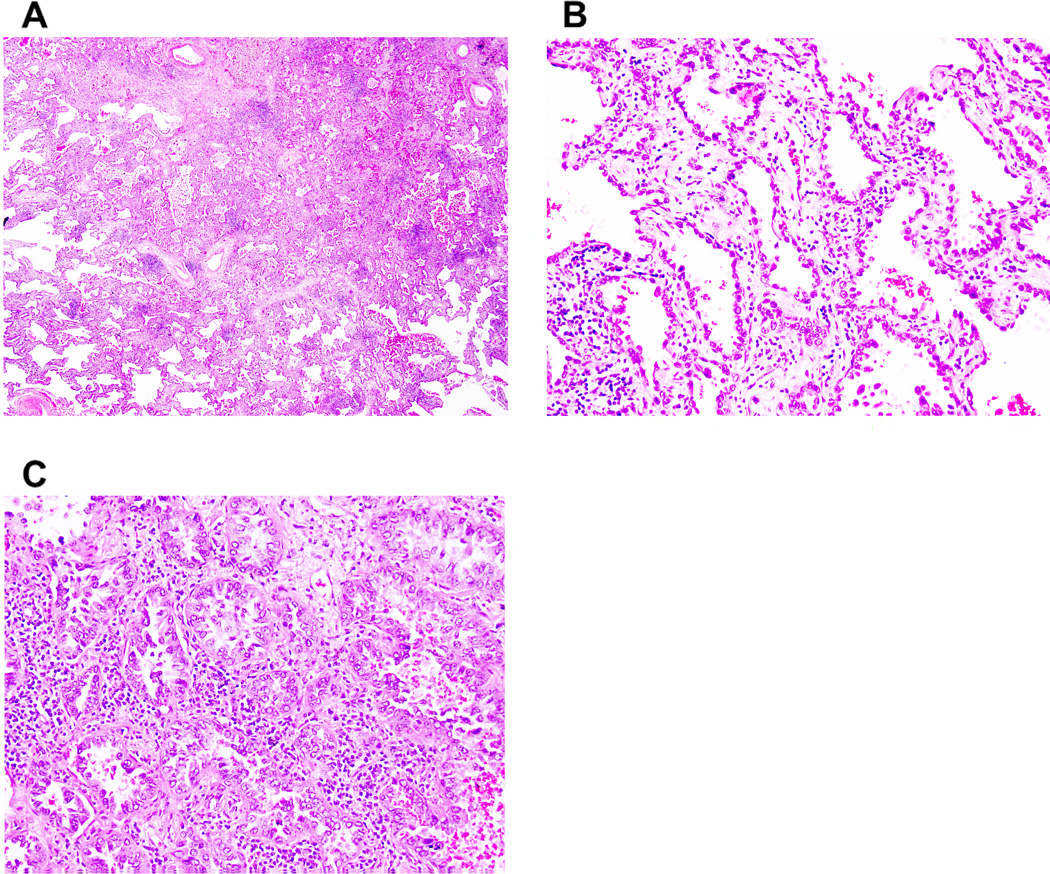

Figure 4. Nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma.

(A) A tumor shows a predominant (about 70%) lepidic pattern with >5 mm stromal invasion. (B) Nonmucinous tumor cells spread along alveolar walls (lepidic pattern) without invasion. (C) Tumor cells show small glandular morphology (acinar pattern).

Nuclear features were examined with a high-power field (HPF) of ×400 magnification (0.237 mm2). Nuclear atypia was identified in the area with the highest degree of atypia and was graded as follows: (1) mild: nuclei were uniform in size and shape; (2) moderate: nuclei were of intermediate size and had slight irregularities; and (3) severe: nuclei were enlarged to varying degrees, with some nuclei at least twice as large as others.26–28 Mitoses were evaluated at 50 HPFs in areas with the highest mitotic activity and were counted as the average number of mitotic figures per 10 HPFs.26, 29, 30 Tumors were classified according to mitotic count as follows: (1) low: 0–1 mitoses per 10 HPFs; (2) intermediate: 2–4 mitoses per 10 HPFs; and (3) high: ≥5 mitoses per 10 HPFs.24, 31

Statistical Analysis

Associations between histologic subtypes and clinicopathologic variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables) and the Wilcoxon test (for continuous variables). Because traditional Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival probabilities can be biased when a large number of patients die without recurrence and are subsequently censored, especially if the rate of death is differential across groups, in this analysis, we considered death from causes other than recurrence as a competing event. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) was used to estimate the probability of recurrence.32, 33 Follow-up was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of the first recurrence, death from any cause, or last follow-up, whichever came first. Differences in CIR between groups were examined using Gray’s methods.34 Competing risks regression analysis was used to examine associations between each variable and recurrence, after adjustment for important potential confounders. All P values were based on 2-tailed statistical analysis and P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Development Core Team, 2010), including the “survival” and “cmprsk” packages.

RESULTS

Association between Clinicopathologic Factors and Recurrence

The clinicopathologic factors for all 1038 patients are shown in Table 2. The median age was 69 years (range, 23–96 years). The majority of patients were women (62%), and most had stage IA disease (70%). In total, 77% underwent lobectomy, and 23% underwent sublobar resection (segmentectomy [n=76] and wedge resection [n=166]). Visceral pleural invasion was observed in 17% of patients, lymphatic invasion in 32%, vascular invasion in 25%, and tumor necrosis in 16%.

Table 2.

Association between Clinicopathologic Factors and Lepidic Predominant Subtype

| Variables | All | AIS/MIA, no. (%) |

Lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma, no. (%) |

Non-lepidic predominant, no. (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 1038 | 36 (3) | 103 (10) | 899 (87) | |

| Age, years | 0.63* | ||||

| Median (range) | 69 (23–96) | 69 (23–86) | 70 (41–89) | 69 (33–96) | |

| Sex | 0.92* | ||||

| Female | 646 | 26 (4) | 60 (9) | 560 (87) | |

| Male | 392 | 10 (3) | 43 (11) | 339 (86) | |

| Race | <0.001* | ||||

| Asian | 40 | 5 (13) | 10 (25) | 25 (63) | |

| Non-Asian | 998 | 31 (3) | 93 (9) | 874 (88) | |

| Smoking | 0.011* | ||||

| Never | 176 | 7 (4) | 27 (15) | 142 (81) | |

| Ever | 862 | 29 (3) | 76 (9) | 757 (88) | |

| Laterality | 0.56* | ||||

| Right | 611 | 24 (4) | 61 (10) | 526 (86) | |

| Left | 427 | 12 (3) | 42 (10) | 373 (87) | |

| Surgical resection | 0.10* | ||||

| Lobar | 796 | 18 (2) | 81 (10) | 697 (88) | |

| Sublobar | 242 | 18 (7) | 22 (9) | 202 (83) | |

| Tumor size, cm | 0.027** | ||||

| Median (range) | 2.0 (0.3–5) | 1.2 (0.4–2.9) | 1.8 (0.7–5.0) | 2.0 (0.3–5.0) | |

| T stage | <0.001** | ||||

| T1a | 494 | 31 (6) | 66 (13) | 397 (80) | |

| T1b | 237 | 5 (2) | 23 (10) | 209 (88) | |

| T2 | 307 | 0 (0) | 14 (5) | 293 (95) | |

| Pleural invasion | <0.001** | ||||

| Absent | 866 | 36 (4) | 100 (12) | 730 (84) | |

| Present | 172 | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 169 (98) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001** | ||||

| Absent | 707 | 36 (5) | 95 (13) | 576 (81) | |

| Present | 331 | 0 (0) | 8 (2) | 323 (98) | |

| Vascular invasion | <0.001** | ||||

| Absent | 778 | 36 (5) | 98 (13) | 644 (83) | |

| Present | 260 | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 255 (98) | |

| Necrosis | <0.001** | ||||

| Absent | 869 | 36 (4) | 101 (12) | 732 (84) | |

| Present | 169 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 167 (99) | |

| Nuclear atypia | <0.001* | ||||

| Mild | 451 | 32 (7) | 72 (16) | 347 (77) | |

| Moderate | 360 | 4 (1) | 28 (8) | 328 (91) | |

| Severe | 227 | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 224 (99) | |

| Mitotic count, mitoses, median (range) | 1 (0–76) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–6) | 2 (0–76) | <0.001* |

Significant P values are shown in bold.

AIS/MIA and lepidic predominant invasive vs. nonlepidic predominant.

Lepidic predominant invasive vs. nonlepidic predominant.

AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

Of all the patients, 144 (14%) experienced a recurrence, and 151 (15%) died from any cause without a recurrence. The median follow-up for patients who did not experience a recurrence was 37.4 months (range, 0.3–160.0 months). On univariate analysis, male sex (P=0.002), sublobar resection (P<0.001), pleural invasion (P<0.001), lymphatic invasion (P<0.001), vascular invasion (P<0.001), tumor necrosis (P<0.001), greater nuclear atypia (P<0.001), and higher mitotic count (P<0.001) were associated with a higher risk of recurrence.

Histologic Findings

On histologic analysis of the tumor specimens, 2 were identified as nonmucinous AIS (0.2%), 34 as MIA (3%) (nonmucinous [n=32], mucinous [n=1], and mixed mucinous/nonmucinous [n=1]), and 103 as nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma (10%). The remaining tumors were identified as follows: 411 acinar predominant (40%), 239 papillary predominant (23%), 60 micropapillary predominant (6%), 136 solid predominant (13%), 44 invasive mucinous (4%), and 9 colloid predominant (1%).

Of the tumors with lepidic predominant pattern with either no invasion or ≤5 mm invasion, none had pleural, lymphatic, or vascular invasion or tumor necrosis. Therefore, AIS and MIA were differentiated from lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma only on the basis of total tumor size and invasive size. All 34 MIA tumors had ≤5 mm invasion when measured using a ruler as well as by multiplying the total tumor size by the percentage of invasive component. Acinar was the most common predominant invasive pattern in MIA tumors (n=31; 91%), followed by papillary (n=3; 9%).

Among the 103 lepidic predominant invasive tumors, the average percentage of lepidic pattern was 50% (range, 40%-85%), and the most common predominant invasive pattern was acinar (n=83; 81%), followed by papillary (n=18; 17%) and micropapillary (n=2; 2%).

All of the ≤3 cm lepidic predominant invasive tumors (n=90) had >5 mm invasion when measured by a ruler; however, 21 of these had ≤5 mm invasion when measured using the multiplication method (none of these had pleural, lymphatic, or vascular invasion or necrosis). Of the >3 cm lepidic predominant invasive tumors (n=13), 1 had ≤5 mm invasion when measured by a ruler as well as by the multiplication method.

Correlation between Lepidic Predominant Subtypes and Clinicopathologic Factors

Table 2 presents the association between lepidic predominant subtypes and clinicopathologic factors. Lepidic predominant tumors (AIS, MIA, and lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma) were observed more frequently among Asian patients (P<0.001) and never smokers (P=0.011), compared with non-lepidic predominant tumors. Lepidic predominant invasive tumors correlated with smaller tumor size (P=0.027) and lower T stage (P<0.001), compared with non-lepidic predominant tumors.. Tumors ≤2 cm had the highest percentage of lepidic pattern (mean ± SD, 21% ± 24%), followed by >2–3 cm tumors (16% ± 20%) and >3 cm tumors (12% ± 18%) (P<0.001). Lepidic predominant invasive tumors had pleural invasion (P<0.001), lymphatic invasion (P<0.001), vascular invasion (P<0.001), and necrosis (P<0.001) less frequently, compared with non-lepidic predominant invasive tumors. In addition, lepidic predominant tumors correlated with mild nuclear atypia (P<0.001) and lower mitotic count (P<0.001), compared with non-lepidic predominant invasive tumors.

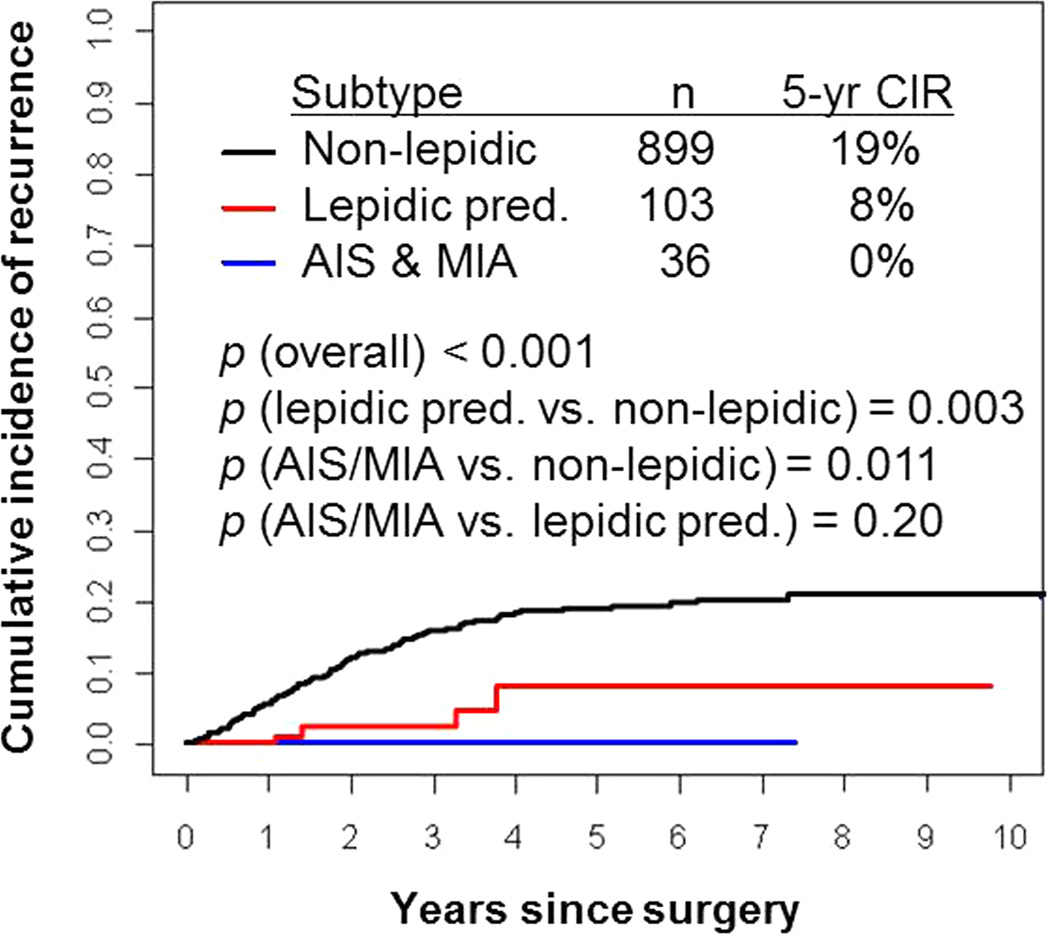

Correlation between Lepidic Predominant Subtypes and Recurrence

Figure 5 presents CIR by lepidic predominant subtype. None of the patients with AIS or MIA (n=36) experienced a recurrence (5-year CIR, 0%). Of all the patients with lepidic predominant invasive tumors (n=103), 4 experienced a recurrence. Patients with lepidic predominant invasive tumors had a lower risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 8%) than patients with non-lepidic predominant tumors (n=899; 5-year CIR, 19%; P=0.003). Interestingly, none of the patients with ≤3 cm lepidic predominant invasive tumors with >5 mm invasion when measured by a ruler but ≤5 mm when measured using the multiplication technique (n=21) experienced a recurrence.

Figure 5. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) by lepidic predominant subtypes.

Patients with AIS and MIA (n=36) experienced no recurrences (5-year CIR, 0%). Patients with lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma had a lower risk of recurrence (n=103, 5-year CIR, 8%) than patients with non-lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma (n=899; 5-year CIR, 19%).

In the cases of non-lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma with recurrence (n=140), 91 had distant metastasis, 42 had local recurrence, and 7 had both distant and local recurrence. When the 4 cases of lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma with recurrence were examined closely (Table 3), 2 had distant metastasis (bone and chest wall), and the other 2 had local recurrence (lung). Two of these cases underwent sublobar (wedge) resection with close staple margins from the tumor (0.2 cm and 0.5 cm). For comparison, in patients who underwent limited resection without a recurrence (n=20), the median distance between the staple margin and the tumor was 1.3 cm (range, 0.3–7.5 cm). In 2 of the 4 cases with recurrence, the tumors had a substantial micropapillary component (30% and 20%), with lymphatic invasion (Figure 6),—1 of these also had vascular invasion. In contrast, among the 99 cases of lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma without recurrence, 6 tumors (6%) had lymphatic invasion, and 4 tumors (4%) had vascular invasion; the median percentage of micropapillary pattern was 0% (range, 0%–35%).

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Recurrent or Nonrecurrent Lepidic Predominant Invasive Adenocarcinoma

| Variable | Nonrecurrent (n=99) |

Recurrent (n=4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | ||

| Surgical resection | Lobar | Sublobar | Sublobar | Lobar | |

| Lobar | 79 | ||||

| Sublobar | 20 | ||||

| Distance to staple margin, cm | |||||

| Median (range) | 1.3 (0.3–7.5) | NA | 0.2 | 0.5 | NA |

| Location of recurrence | NA | Bone | Lung | Chest wall | Lung |

| Time till recurrence, years | NA | 1.4 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| Total tumor size, cm | |||||

| Median (range) | 1.7 (0.7–5.0) | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Invasive tumor size, cm | |||||

| Median (range) | 0.8 (0.6–2.8) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| T stage | T1b | T1a | T1a | T1b | |

| T1a | 64 | ||||

| T1b | 21 | ||||

| T2 | 14 | ||||

| Pleural invasion | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| Present | 3 | ||||

| Absent | 96 | ||||

| Lymphatic invasion | Present | Present | Absent | Absent | |

| Present | 6 | ||||

| Absent | 93 | ||||

| Vascular invasion | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| Present | 4 | ||||

| Absent | 95 | ||||

| Necrosis | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| Present | 2 | ||||

| Absent | 97 | ||||

| Histologic pattern, % | |||||

| Median (range) | |||||

| Lepidic | 50 (40–85) | 40 | 40 | 50 | 50 |

| Acinar | 30 (0–45) | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| Papillary | 10 (0–40) | 10 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Micropapillary | 0 (0–35) | 30 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Solid | 0 (0–20) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nuclear atypia | Mild | Moderate | Mild | Mild | |

| Mild | 69 | ||||

| Moderate | 27 | ||||

| Severe | 3 | ||||

| Mitotic count, mitoses, median (range) | 1 (0–6) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

NA, not applicable.

Figure 6. Nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma with micropapillary pattern and lymphatic invasion.

(A) A tumor shows a predominant (about 70%) lepidic pattern with >5 mm stromal invasion. (B) Micropapillary component is identified in part of the tumor. (C) Tumor cell shows lymphatic invasion.

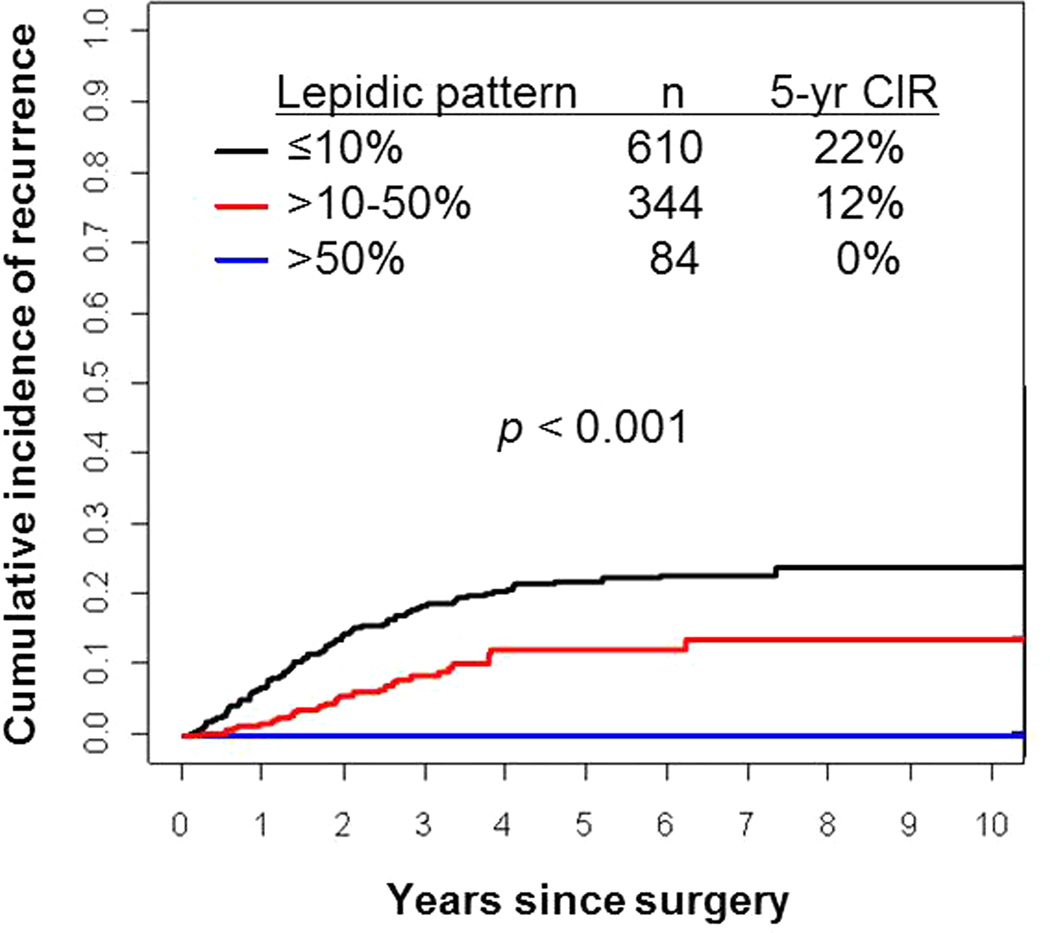

Correlation between Percentage of Lepidic Pattern and Recurrence

Figure 7 presents CIR by percentage of lepidic pattern. Patients with >50% lepidic pattern tumors (n=84) experienced no recurrences (5-year CIR, 0%). Patients with >10%–50% lepidic pattern tumors (n=344) had a lower risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 12%) than patients with ≤10% lepidic pattern tumors (n=610; 5-year CIR, 22%; P<0.001). Overall, higher percentage of lepidic pattern had a statistically significant correlation with lower risk of recurrence (P<0.001).

Figure 7. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) by percentage of lepidic pattern.

Patients with >50% lepidic pattern tumors (n=84) experienced no recurrences (5-year CIR, 0%). Patients with >10%–50% lepidic pattern tumors (n=344) had a lower risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 12%) than patients with ≤10% lepidic pattern tumors (n=610; 5-year CIR, 22%).

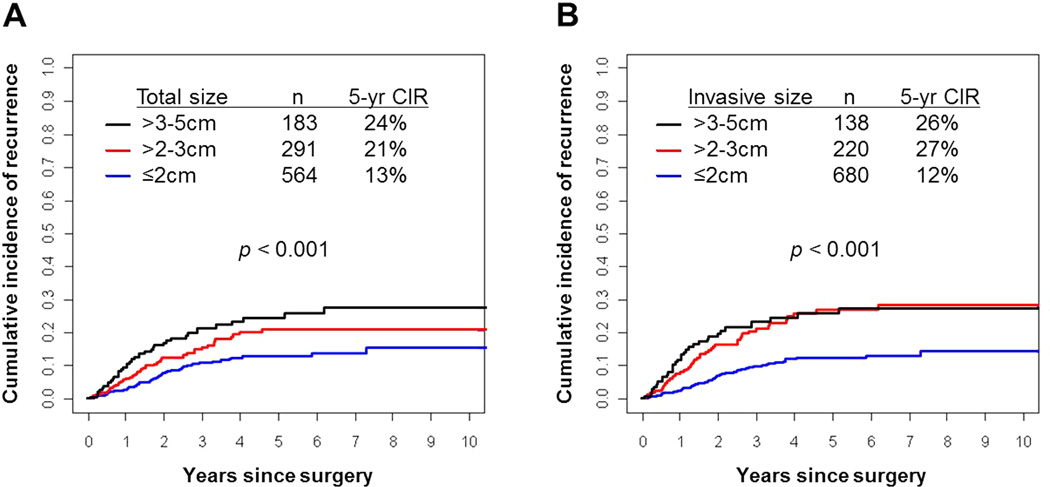

Correlation between Invasive Tumor Size and Recurrence

Figure 8 presents CIR in terms of total tumor size and invasive tumor size (according to T stage criteria: ≤2 cm, >2–3 cm, and >3–5 cm). Total tumor size ≤2 cm (n=564) had the lowest risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 13%), followed by >2–3 cm (n=291; 21%) and >3–5 cm (n=183; 24%; P<0.001) (Figure 8A). Similarly, invasive tumor size ≤2 cm (n=680) had the lowest risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 12%), followed by >2–3 cm (n=220; 5-year CIR, 27%) and >3–5 cm (n=138; 5-year CIR, 26%; P<0.001) (Figure 8B). CIR was lower for patients with ≤2 cm tumors than for those with >2–3 cm tumors (for both total and invasive tumor size), with the difference more pronounced for invasive tumor size (5-year CIR, 13% vs. 21% [total size; P=0.022] and 12% vs. 27% [invasive size; P<0.001]). When tumors were categorized according to invasive size, instead of total size, there were fewer tumors in the >2–3 cm group (n=291 [total size] vs 220 [invasive size]). By adjusting total tumor size to invasive size 116 (40%) of T1b (>2–3 cm) tumors were reclassified as T1a (≤2 cm) and 45 (25%) of T2a (>3–5 cm) tumors were reclassified as T1b (>2–3 cm) tumors.

Figure 8. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) by total and invasive tumor size.

(A) Patients with ≤2 cm total tumor size (n=564) had the lowest risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 13%), followed by >2–3 cm (n=291; 21%) and >3–5 cm (n=183; 24%). (B) Patients with ≤2 cm invasive tumor size (n=680) had a lower risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 12%) than those with >2–3 cm (n=220; 5-year CIR, 27%) or >3–5 cm (n=138; 5-year CIR, 26%). There were fewer tumors measuring >2–3 cm according to invasive size than to total size (220 vs 291); the CIR was worse for tumors measured according to invasive size than total size (27% vs 21%).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that (1) patients with AIS or MIA experienced no recurrences and that patients with lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma had a low risk of recurrence, (2) higher percentage of lepidic pattern correlated with lower risk of recurrence, (3) the prognostic difference between ≤2 cm tumors and >2–3 cm tumors was more pronounced for invasive tumor size than for total tumor size, and (4) the lepidic predominant pattern correlated with several clinicopathologic characteristics, including predominantly Asian race/ethnicity, history of never smoking, smaller tumor size, lower incidence of invasion (lymphatic, vascular, and plural), less nuclear atypia, and lower mitotic count.

Previous studies have suggested that patients with pure lepidic (noninvasive) tumors have 100% 5-year disease-free survival (DFS)4–7 and that patients with MIA have nearly 100% DFS if completely resected.8–10, 35–39 Perhaps in the future, AIS and MIA may be combined into a single category on the basis of the very similar patient outcome between them. The addition of the entity MIA has been one of the most welcome additions in this new classification because the lack of recurrence of these tumors has removed the clinical importance for pathologists to distinguish AIS from MIA based on whether a small focus represents invasion or not. However, at the present time, more data are needed on MIA to be certain there will be no recurrences, particularly if the invasive component of such tumors consists of solid, micropapillary or small amounts of sarcomatoid components. Furthermore, our current data suggest that less than 5 percent of lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma recur, so in the vast majority of cases, there may be few clinical implications for pathologists in the distinction between MIA and lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma. In addition, invasive tumors with nonmucinous lepidic predominant growth correlated with favorable prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma.11–13, 35–41 These results are compatible with our findings: patients with AIS or MIA experienced no recurrences, and patients with nonmucinous lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma had a low risk of recurrence (5-year CIR, 8%). The data regarding MIA as a very favorable prognostic category has largely been based on nonmucinous tumors, as mucinous and mixed mucinous/nonmucinous MIA are extremely rare. We identified 2 patients with MIA with a mucinous lepidic pattern (1 pure mucinous and 1 mixed mucinous/nonmucinous), both of whom did not experience a recurrence. Noguchi et al. previously reported two cases that would probably qualify as mucinous AIS that had 100% 5-year DFS.4 However, further investigations are needed to confirm the prognostic significance of mucinous and mixed mucinous/nonmucinous MIA.

One of the most interesting findings in our study was that most patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma who experienced a recurrence (n=4) had 1 or more potential risk factors, including (1) limited resection with a close margin (≤0.5 cm), (2) lymphatic or vascular invasion, and (3) a substantial component of a high-grade pattern, such as micropapillary. The 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification proposed a research question to determine whether patients with MIA with a high-grade invasive component—such as solid, micropapillary or sarcomatoid—would have 100% disease-free survival.2 This question could be adapted to lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas, as tumors with these poorly differentiated invasive components may carry a greater risk of recurrence. We have recently shown that the presence of a micropapillary component and a close surgical margin (≤0.5 cm) are independent predictors of recurrence in patients with lung adenocarcinoma treated with limited resection.42 In the future, the presence of these risk factors may help surgeons to choose lobectomy over limited resection for appropriate patients, and our data suggest that this principle may apply to lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas as well.

In this study, invasion (pleural, lymphatic, or vascular) and tumor necrosis were very rare in lepidic predominant tumors. In addition, none of the lepidic predominant tumors with ≤5 mm invasion (AIS or MIA) had these histologic factors. We have demonstrated that all of the tumors classified as MIA had ≤5 mm invasion when measured by a ruler as well as by multiplying the total tumor size by the percentage of invasive component, and none led to recurrence. Interestingly, 21 patients had ≤3 cm lepidic predominant invasive tumors with >5 mm invasion when measured by a ruler but they were reclassified as ≤5 mm, and would have met criteria for MIA when measured using the multiplication method, and none of these patients experienced a recurrence. With our results, it is possible the size criteria for minimal invasion and the method used to measure invasion size could be modified. It appears that measuring invasive size by multiplying the total tumor size by the percentage of the invasive component may be a practical and reliable approach. Further investigation and validation would be helpful to address this question.

We have demonstrated that patients with >50% lepidic pattern tumors had no recurrences, patients with >10%–50% lepidic pattern tumors had an intermediate risk of recurrence, and patients with ≤10% lepidic pattern tumors had the highest risk of recurrence. However, in a small percentage of cases, the lepidic component may be the predominant pattern and be less than 50%. Lee et al. reported similar results, showing that patients with lung adenocarcinoma with >50% lepidic pattern had better disease-free survival than patients with <50% lepidic pattern.11 Yokose et al. reported that patients with lung adenocarcinoma with >75% lepidic pattern had 100% survival.12 In addition, Lin et al. demonstrated a clear stratification of survival on the basis of percentage of lepidic pattern (<50%, 50%–79%, 80%–99%, and 100%).13 The percentage of lepidic pattern is inversely proportional to the extent of the invasive component; therefore, higher percentage of lepidic pattern correlates with better prognosis, as the extent of invasion is driving recurrence.

We have previously demonstrated that the prognostic difference between ≤2 cm tumors and >2–3 cm tumors is more pronounced when tumors are categorized by invasive size.23 The current study validated this finding using a larger cohort of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. With regard to total tumor size, CIR was stratified into 3 groups on the basis of T stage classification (5-year CIR, 13% for ≤2 cm, 21% for >2–3 cm, and 24% for >3–5 cm). However, the CIR for invasive tumors >2–3 cm (5-year CIR, 27%) was closer to that for invasive tumors >3–5 cm (26%) than for those ≤2 cm (12%). It is interesting that the greatest change in recurrence, when tumors were categorized according to invasive size, was observed in the >2–3 cm group, rather than in the ≤2 cm or >3–5 cm group. This may reflect the greater heterogeneity of lepidic component in >2–3 cm tumors, with less change in invasive size among the smaller or larger tumors. Therefore, if T stage is categorized by invasive tumor size, up to 40% of T1b (>2–3 cm) tumors may be reclassified as T1a (≤2 cm) tumors and 25% of T2a (>3–5 cm) tumors may be reclassified as T1b (>2–3 cm) tumors. At any rate, our data should be validated in anticipation of a possible revision of the TNM classification. A growing number of papers in the radiology literature where ground glass vs solid opacity corresponds to lepidic vs invasive histology as well as the pathology literature support this concept.43–45

The 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification defines the lepidic pattern, formerly BAC pattern, as a tumor that spreads along alveolar walls without invasion.2 To better identify the lepidic growth pattern, criteria for invasion should also be clearly established. Noguchi et al. suggested that active fibroblastic proliferation in tumors correlated with invasive tumor cell growth, indicating a prognostic correlation with the presence of active fibroblastic stroma in BAC.4 It has also been suggested that the structural deformity of the stromal elastic fiber framework, as observed on elastin stain, should be considered a finding of invasion.5 In the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, the following 3 factors are considered to indicate invasion: (1) histologic pattern other than lepidic, (2) active myofibroblastic stroma, and (3) lymphovascular or pleural invasion. In the present study, we have used the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification criteria to identify tumor invasion.

We found that tumors with a lepidic predominant pattern correlated with Asian race/ethnicity and a history of never smoking. These associations have also correlated with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, which are more frequently observed in Asian patients and never smokers.46–48 These tumors generally correspond to tumors historically classified as adenocarcinoma with BAC features49–51; however, it is now recommended that the use of this term be discontinued, as tumors formerly referred to as BAC can now be classified as five different types of lung adenocarcinoma.2

Several important factors need to be considered in the diagnosis of AIS, MIA, and lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma. AIS and MIA should not be diagnosed unless the tumor has been completely resected. Furthermore, to correctly identify the extent of lepidic versus invasive patterns in lung adenocarcinoma, pathologists may need to correlate pathologic findings with CT findings as the lepidic component is often under-appreciated on gross evaluation of the tumor. This can lead to undersampling of the tumor and during microscopic assessment, misleading impressions about tumor size including total size and the size of the invasive components.15–17 However, the final decision on lepidic pattern versus invasive pattern should be made by microscopic examinations even if the pathologists may refer to the CT findings. In addition, overall survival should not be used for evaluating outcomes of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma, in particular those with lepidic predominant tumors, as most of these patients die of causes other than recurrence. CIR analysis is a more reliable representation of prognosis according to recurrence since death without recurrence should be considered as a competing event.52 Although our method of prognostic analysis (using CIR) is different from the traditional approach (using overall or disease-free survival), we have previously shown that CIR more accurately represents tumor behavior.53, 54 Recent studies that have failed to demonstrate significance of adenocarcinoma histologic subtyping used overall survival rather than survival linked to recurrence such as DFS or CIR.55, 56 Furthermore, a recurrence must be distinguished from a metachronous primary, as may have occurred in the single case of development of an additional lung nodule in a different lobe of the same lung in one of the MIA cases reported by Xu et al.57 As raised in our study, it may also be important to take into consideration if lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma underwent limited resection with a close margin as it can be very difficult to assess lepidic growth at a staple line margin.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the clinical and prognostic importance of the lepidic pattern using a large cohort of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. According to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, performing comprehensive histopathologic subtyping for lung adenocarcinoma helps to characterize the extent of lepidic versus invasive components. As we have shown, this can also be used to estimate the size of tumor invasion, particularly in tumors in which the invasive component cannot be measured as a single focus on 1 slide. In addition, we have shown that it may be possible to stratify lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas according to risk factors for recurrence. In the future, this may guide surgeons to choose lobectomy over limited resection for the treatment of these patients if we can provide the evidence in the future study that the histologic subtyping on frozen section predicts the final diagnosis on the basis of the examinations for entire tumors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Dycoco, for his help with the lung adenocarcinoma database in the Division of Thoracic Service, Department of Surgery; and David Sewell, for his editorial assistance.

Funding/Support

This work was supported, in part, by William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin, the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research and the Experimental Therapeutics Center; the National Cancer Institute (grants R21CA164568 and R21CA164585); and the U.S. Department of Defense (grant LC110202).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures

All authors affirm no actual or potential conflicts of interest, including any financial, personal, or other relationships with other people or organizations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Travis W, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink H, Harris C World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. Pathology and Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(2):244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones KD. Whence Lepidic? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013 Aug 12; doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0144-HP. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noguchi M, Morikawa A, Kawasaki M, et al. Small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Histologic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer. 1995;75(12):2844–2852. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2844::aid-cncr2820751209>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai H, Maeshima A, Watanabe S, et al. Grade of stromal invasion in small adenocarcinoma of the lung: histopathological minimal invasion and prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(2):198–206. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez M, Carter D, Brambilla E, et al. Solitary and multiple resected adenocarcinomas after CT screening for lung cancer: histopathologic features and their prognostic implications. Lung Cancer. 2009;64(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koike T, Togashi K, Shirato T, et al. Limited resection for noninvasive bronchioloalveolar carcinoma diagnosed by intraoperative pathologic examination. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(4):1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borczuk AC, Qian F, Kazeros A, et al. Invasive size is an independent predictor of survival in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(3):462–469. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318190157c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yim J, Zhu LC, Chiriboga L, et al. Histologic features are important prognostic indicators in early stages lung adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(2):233–241. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeshima AM, Tochigi N, Yoshida A, et al. Histological scoring for small lung adenocarcinomas 2 cm or less in diameter: a reliable prognostic indicator. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(3):333–339. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c8cb95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HY, Han J, Lee KS, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma as a solitary pulmonary nodule: prognostic determinants of CT, PET, and histopathologic findings. Lung Cancer. 2009;66(3):379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokose T, Suzuki K, Nagai K, et al. Favorable and unfavorable morphological prognostic factors in peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung 3 cm or less in diameter. Lung Cancer. 2000;29(3):179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin DM, Ma Y, Zheng S, et al. Prognostic value of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma component in lung adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21(6):627–632. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. Diagnosis of Lung Adenocarcinoma in Resected Specimens: Implications of the 2011 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Classification. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(5):685–705. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0264-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakata M, Sawada S, Saeki H, et al. Prospective study of thoracoscopic limited resection for ground-glass opacity selected by computed tomography. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(5):1601–1605. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04815-4. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki K, Asamura H, Kusumoto M, Kondo H, Tsuchiya R. "Early" peripheral lung cancer: prognostic significance of ground glass opacity on thin-section computed tomographic scan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(5):1635–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takashima S, Li F, Maruyama Y, et al. Discrimination of subtypes of small adenocarcinoma in the lung with thin-section CT. Lung Cancer. 2002;36(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Iersel CA, de Koning HJ, Draisma G, et al. Risk-based selection from the general population in a screening trial: Selection criteria, recruitment and power for the Dutch-Belgian randomised lung cancer multi-slice CT screening trial (NELSON) Int J Cancer. 2007;120(4):868–874. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sica G, Yoshizawa A, Sima CS, et al. A grading system of lung adenocarcinomas based on histologic pattern is predictive of disease recurrence in stage I tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(8):1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4ee32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshizawa A, Motoi N, Riely GJ, et al. Impact of proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic subgroups and implications for further revision of staging based on analysis of 514 stage I cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(5):653–664. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadota K, Suzuki K, Kachala SS, et al. A grading system combining architectural features and mitotic count predicts recurrence in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(8):1117–1127. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Kadota K, Sima CS, et al. Clinical impact of immune microenvironment in stage I lung adenocarcinoma: tumor interleukin-12 receptor beta2 (IL-12Rbeta2), IL-7R, and stromal FoxP3/CD3 ratio are independent predictors of recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):490–498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barletta JA, Yeap BY, Chirieac LR. Prognostic significance of grading in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116(3):659–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asamura H, Ando M, Matsuno Y, Shimosato Y. Histopathologic prognostic factors in resected adenocarcinomas: is nuclear DNA content prognostic? Chest. 1999;115(4):1018–1024. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurokawa T, Matsuno Y, Noguchi M, Mizuno S, Shimosato Y. Surgically curable "early" adenocarcinoma in the periphery of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(5):431–438. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travis WD, Rush W, Flieder DB, et al. Survival analysis of 200 pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors with clarification of criteria for atypical carcinoid and its separation from typical carcinoid. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(8):934–944. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baak JP. Mitosis counting in tumors. Hum Pathol. 1990;21(7):683–685. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kadota K, Suzuki K, Colovos C, et al. A nuclear grading system is a strong predictor of survival in epitheloid diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(2):260–271. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chappell R. Competing Risk Analyses: How Are They Different and Why Should You Care? Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2127–2129. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dignam JJ, Zhang Q, Kocherginsky M. The Use and Interpretation of Competing Risks Regression Models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2301–2308. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray RJ. A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Annals of Statistics. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell PA, Wainer Z, Wright GM, et al. Does lung adenocarcinoma subtype predict patient survival?: A clinicopathologic study based on the new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary lung adenocarcinoma classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(9):1496–1504. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318221f701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuta K, Kawago M, Inoue E, et al. The utility of the proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma subtypes for disease prognosis and correlation of driver gene alterations. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(3):371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu J, Lu C, Guo J, et al. Prognostic significance of the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification in Chinese patients-A single institution retrospective study of 292 lung adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(5):474–480. doi: 10.1002/jso.23259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo T, Okudela K, Mitsui H, et al. Prognostic value of the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma in stage I disease of Japanese cases. Pathol Int. 2012;62(12):785–791. doi: 10.1111/pin.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Wu J, Tan Q, Zhu L, Gao W. Why Do Pathological Stage IA Lung Adenocarcinomas Vary from Prognosis?: A Clinicopathologic Study of 176 Patients with Pathological Stage IA Lung Adenocarcinoma Based on the IASLC/ATS/ERS Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(9):1196–1202. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31829f09a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warth A, Muley T, Meister M, et al. The novel histologic International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification system of lung adenocarcinoma is a stage-independent predictor of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1438–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von der Thusen JH, Tham YS, Pattenden H, et al. Prognostic significance of predominant histologic pattern and nuclear grade in resected adenocarcinoma of the lung: potential parameters for a grading system. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(1):37–44. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318276274e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nitadori JBA, Kadota K, Sima CS, Rizk NP, Morales EA, Rusch VW, Travis WD, Adusumulli PS. Impact of micropapillary histologic subtype in selecting limited resection vs. lobectomy for lung adenocarcinoma ≤ 2 cm. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(16):1212–1220. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honda T, Kondo T, Murakami S, et al. Radiographic and pathological analysis of small lung adenocarcinoma using the new IASLC classification. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(1):e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Prognostic significance of using solid versus whole tumor size on high-resolution computed tomography for predicting pathologic malignant grade of tumors in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(3):607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanagawa N, Shiono S, Abiko M, et al. New IASLC/ATS/ERS classification and invasive tumor size are predictive of disease recurrence in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(5):612–618. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318287c3eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from "never smokers" and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(36):13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tam IY, Chung LP, Suen WS, et al. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(5):1647–1653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):857–865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh RK, Lim KH, Kuo HT, Tzen CY, Huang MJ. Female sex and bronchioloalveolar pathologic subtype predict EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128(1):317–321. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kadota K, Nitadori J, Sarkaria IS, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression is an independent predictor of recurrence and correlates with the IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119(5):931–938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kadota K, Colovos C, Suzuki K, et al. FDG-PET SUVmax combined with IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification improves the prognostic stratification of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(11):3598–3605. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urer HN, Kocaturk CI, Gunluoglu MZ, et al. Relationship between Lung Adenocarcinoma Histological Subtype and Patient Prognosis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013 doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.12.02073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weissferdt A, Kalhor N, Marom EM, et al. Early-stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma (T1N0M0): a clinical, radiological, surgical, and pathological correlation of 104 cases. The MD Anderson Cancer Center Experience. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(8):1065–1075. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu L, Tavora F, Battafarano R, Burke A. Adenocarcinomas with prominent lepidic spread: retrospective review applying new classification of the American Thoracic Society. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(2):273–282. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823b3eeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]