Abstract

Background

It is more common for women in the developed world, and those in low-income countries giving birth in health facilities, to labour in bed. There is no evidence that this is associated with any advantage for women or babies, although it may be more convenient for staff. Observational studies have suggested that if women lie on their backs during labour this may have adverse effects on uterine contractions and impede progress in labour.

Objectives

The purpose of the review is to assess the effects of encouraging women to assume different upright positions (including walking, sitting, standing and kneeling) versus recumbent positions (supine, semi-recumbent and lateral) for women in the first stage of labour on length of labour, type of delivery and other important outcomes for mothers and babies.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (November 2008).

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi-randomised trials comparing women randomised to upright versus recumbent positions in the first stage of labour.

Data collection and analysis

We used methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for carrying out data collection, assessing study quality and analysing results. A minimum of two review authors independently assessed each study.

Main results

The review includes 21 studies with a total of 3706 women. Overall, the first stage of labour was approximately one hour shorter for women randomised to upright as opposed to recumbent positions (MD −0.99, 95% CI −1.60 to −0.39). Women randomised to upright positions were less likely to have epidural analgesia (RR 0.83 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96).There were no differences between groups for other outcomes including length of the second stage of labour, mode of delivery, or other outcomes related to the wellbeing of mothers and babies. For women who had epidural analgesia there were no differences between those randomised to upright versus recumbent positions for any of the outcomes examined in the review. Little information on maternal satisfaction was collected, and none of the studies compared different upright or recumbent positions.

Authors’ conclusions

There is evidence that walking and upright positions in the first stage of labour reduce the length of labour and do not seem to be associated with increased intervention or negative effects on mothers’ and babies’ wellbeing. Women should be encouraged to take up whatever position they find most comfortable in the first stage of labour.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Labor Stage, First [*physiology]; Posture [*physiology]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Supine Position [physiology]; Time Factors; Walking [*physiology]

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

In cultures not influenced by Western society, women progress through the first stage of labour in upright positions and change position as they wish with no evidence of harmful effects to either the mother or the baby (Andrews 1990; Gupta 2004; Roberts 1989). It is more common for women in the developed world to labour in bed (Boyle 2000; Roberts 1989; Simkin 1989). However, when these women are encouraged, they will choose a number of different positions as the first stage progresses (Carlson 1986; Fenwick 1987; Roberts 1989; Rooks 1999). Some studies have suggested that as a woman reaches five to six centimetres dilatation, there is a preference to lie down (Roberts 1980; Roberts 1984; Williams 1980). This may explain why women in randomised trials frequently have difficulty maintaining the position to which they have been assigned (Goer 1999), and suggests that there may not be a perfect universal position for women in the first stage of labour.

Recumbent (lying down) positions in the first stage of labour can have several practical advantages for the care provider; potentially making it easier to palpate the mother’s abdomen to monitor contractions, perform vaginal examinations, check the baby’s position, and listen to the baby’s heart. Some developments in technology such as fetal monitoring, epidurals for pain relief and the use of intravenous infusions have all made it difficult and potentially unsafe for women to move about during labour.

Numerous studies have shown that a supine position in labour may have adverse physiological effects on the condition of the woman and her baby and on the progression of labour. The weight of the pregnant uterus can compress the abdominal blood vessels, compromising the mother’s circulatory function including uterine blood flow (Abitbol 1985; Huovinen 1979; Marx 1982; Ueland 1969), and this may negatively affect the blood flow to the placenta (Cyna 2006; Roberts 1989; Rooks 1999; Walsh 2000). The effects of a woman’s position on the frequency and intensity of contractions have also been examined (Caldeyro-Barcia 1960; Lupe 1986; Mendez-Bauer 1980; Roberts 1983; Roberts 1984; Ueland 1969). The findings indicated that contractions increased in strength in the upright or lateral position compared to the supine position and were often negatively affected when a labouring woman lay down after being upright or mobile. This effect can often be reversed if the woman returns to an upright position. Effective contractions are vital to aid cervical dilatation and fetal descent (Roberts 1989; Rooks 1999; Walsh 2000) and therefore have an important role in helping to reduce dystocia (slow progress in labour).

Moving about can increase a woman’s sense of control in labour by providing a self-regulated distraction from the challenge of labour (Albers 1997). Support from another person also appears to facilitate normal labour (Hodnett 2007). Increasing a woman’s sense of control may have the effect of decreasing her need for analgesia (Albers 1997; Hodnett 2007; Lupe 1986; Rooks 1999) and it has also been suggested that upright positions in the first stage of labour may increase women’s comfort (Simkin 2002).

Because different groups advocate various positions in the first stage of labour, it seems particularly important to assess the available evidence so that positions which are shown to be safe and effective can be encouraged.

A related Cochrane review focuses on maternal position for fetal malpresentation in labour (Hunter 2007).

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this review is to assess the effects of different upright and recumbent positions and mobilisation for women in the first stage of labour on length of labour, type of delivery and other important outcomes for mothers and babies.

The primary objective is:

to compare the effects of upright (defined as walking and upright non-walking, e.g. sitting, standing, kneeling, squatting and all fours) positions with recumbent positions (supine, semi-recumbent and lateral) assumed by women in the first stage of labour on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes.

The secondary objectives are:

to compare the effects of semi-recumbent and supine positions with lateral positions assumed by women in the first stage of labour on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes;

to compare the effects of walking with upright non-walking positions (sitting, standing, kneeling, squatting, all fours) assumed by women in the first stage of labour on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes;

to compare the effects of walking with recumbent positions (supine, semi-recumbent and lateral) assumed by women in the first stage of labour on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes;

to compare allowing women to assume the position/s they choose with recumbent positions (supine, semi-recumbent and lateral) assumed by women in the first stage of labour on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi-randomised trials. We planned to include cluster randomised trials which were otherwise eligible. Cross-over trials might be useful for short-term outcomes such as fetal heart rate patterns, but would not be appropriate for the main outcomes of this review and were not included.

Types of participants

Women in the first stage of labour.

Types of interventions

The type of intervention was the position or positions assumed by women in the first stage of labour. The positions assumed by a women in the first stage of labour can be broadly categorised as being either upright or recumbent.

The positions considered recumbent were:

semi recumbent;

lateral;

supine.

The positions considered upright included:

sitting;

standing;

walking;

kneeling;

squatting;

all fours (hands and knees).

Types of outcome measures

Primary maternal outcomes:

length of first stage of labour;

type of delivery (spontaneous vaginal delivery, operative vaginal or caesarean);

maternal satisfaction with positioning and with the childbirth experience.

Primary fetal and neonatal outcomes:

fetal distress requiring immediate delivery;

use of neonatal mechanical ventilation.

Secondary maternal outcomes:

pain as experienced by the woman;

use of analgesics (amount and type, e.g. epidural/opioid);

length of second stage of labour;

augmentation of labour using oxytocin;

artificial rupture of membranes;

spontaneous rupture of membranes;

hypotension requiring intervention;

estimated blood loss > 500 ml;

perineal trauma (including episiotomy and third and fourth degree tears).

Secondary neonatal outcomes:

Apgar of less than seven at five minutes following delivery;

admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (31 December 2008).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We performed a manual search of the references of all retrieved articles and contacted expert informants.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

We used methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for data collection, assessing study quality and analysing results (Higgins 2008).

Selection of studies

A minimum of two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion, or when required we consulted an additional person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. At least two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion, or if required we consulted a third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008), and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor. Please see the ‘Risk of bias’ tables following the Characteristics of included studies tables for the assessment of bias for each study.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence to assess whether methods were truly random.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether group allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed afterwards.

We have assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We have described for each included study the methods used to blind study personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We have described where there was any attempt at partial blinding (e.g. of outcome assessors). It is important to note that with the types of interventions described in this review, blinding participants to group assignment is generally not feasible. Similarly, blinding staff providing care is very difficult, and this may have the effect of increasing co-interventions, which in turn may affect outcomes. The lack of blinding in these studies may be a source of bias, and this should be kept in mind in the interpretation of results.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We have described for each included study the completeness of outcome data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusion where reported, and any re-inclusions in analyses which we have undertaken.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. where there was no missing data or low levels (less than 10%) and where reasons for missing data were balanced across groups);

inadequate (e.g. where there were high levels of missing data (more than 10%));

unclear (e.g. where there was insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(5) Other sources of bias and overall risk of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We have made explicit judgements about risk of bias for important outcomes both within and across studies. With reference to 1-4 above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We have explored the impact of risk of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses; see Sensitivity analysis below.

Measures of treatment effect

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data in the absence of significant heterogeneity if trials were sufficiently similar. When significant heterogeneity was present, we used a random-effects meta-analysis.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data (e.g. maternal pain and satisfaction when measured as scores or on visual analogue scales) we have used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster-randomised trials

We intended to include cluster-randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials, and to adjust sample sizes using the methods described in Gates 2005 and Higgins 2008. We identified no cluster randomised trials in this version of the review, but if we identify such trials in future searches we will include them in updates.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. Where data were not reported for some outcomes or groups we attempted to contact the study authors for further information.

Intention to treat analysis (ITT)

We had intended to analyse data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If in the original reports participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the trial report, we have attempted to restore them to the correct group (e.g. we did this for the data from the Calvert 1982 study).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. Where we have identified high levels of heterogeneity among the trials (greater than 50%), we explored it by pre-specified subgroup analysis and by performing sensitivity analysis. A random-effects meta-analysis was used as an overall summary for these comparisons.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we had planned subgroup analyses by: - nulliparous versus multiparous women.

However, several trials recruited only nulliparous women, and in other trials results were presented separately for nulli- and multiparous women and no overall findings (for all women irrespective of parity) were reported. For example, for the primary review outcome (duration of the first stage of labour) of the nine trials providing data, four provided mean figures for nulli- and multi-parous women, but no overall mean. Thus, for pragmatic reasons (in order to use all available data from trials) we have reported overall results for all women, but in the analysis data have been grouped according to parity if this is how data were presented in the trial reports.

We had also planned subgroup analysis by:

- women with a low-risk pregnancy (no complications, greater than or equal to 37 weeks’ gestation, singleton with a cephalic presentation) versus high-risk pregnancy.

Data were not available to carry out this analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there was risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality (e.g. inadequate allocation concealment or high levels of attrition), we explored this by sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

We identified a total of 53 reports representing 47 studies by the search strategy.

Included studies

We included 21 studies with a total of 3706 women in the review. Studies were carried out in a number of countries; seven in the UK (Broadhurst 1979; Calvert 1982; Collis 1999; Fernando 1994; Flynn 1978; McManus 1978; Williams 1980); five in the USA (Andrews 1990; Bloom 1998; Mitre 1974; Nageotte 1997; Vallejo 2001); two in France (Frenea 2004; Karraz 2003); and one each in Finland (Haukkama 1982;), Sweden (Bundsen 1982), Hong Kong (Chan 1963), Japan (Chen 1987), Australia (MacLennan 1994), Brazil (Miquelutti 2007) and Thailand (Phumdoung 2007). Several of the studies included only nulliparous women (Andrews 1990; Chan 1963; Collis 1999; Fernando 1994; Miquelutti 2007; Mitre 1974; Nageotte 1997; Phumdoung 2007; Vallejo 2001). We have set out details of inclusion and exclusion criteria for individual studies and descriptions of the interventions in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

We excluded 25 studies from the review. Several of the studies were not randomised trials or it was not clear that there had been random allocation to groups (Allahbadia 1992; Asselineau 1996; Caldeyro-Barcia 1960; Solano 1982); two of the studies used crossover designs (Melzack 1991; Molina 1997). One study was excluded because the rate of attrition meant that it was difficult to interpret results: in the Diaz 1980 study, more than 30% of the intervention group were excluded post-randomisation because they did not comply with the protocol. In the Hemminki 1983 study, women in the two study groups received different packages of care, so it was not possible to separate out the possible treatment effect of maternal position on outcomes. The McCormick 2007 study had not taken place.

In some studies, the intervention was not comparing mobility or upright positions with recumbent positions; for example, Cobo 1968 and Wu 2001 examined lying in bed on one side rather than the other, or lying supine. In some studies position/mobility was compared with a different type of intervention, for example the Hemminki 1985 study included women experiencing delay in labour and compared immediate oxytocin with ambulation and delayed oxytocin. Similarly, Read 1981 examined oxytocin in labour. The COMET 2001 study compared women receiving different types of epidural, while in the Hodnett 1982 study the main focus was on electronic fetal monitoring, and ambulation was an outcome rather than part of the intervention. Three studies focused on interventions in the second, rather than in the first stage of labour (Hillan 1984; Liu 1989; Radkey 1991).

Several studies, which may otherwise have been eligible, focused on outcomes which had not been pre-specified in this review. For example, Danilenko-Dixon 1996 focused on cardiac output, while the study by Schmidt 2001 and those by Ahmed 1985, Cohen 2002 and Schneider-Affeld 1982 (reported in brief abstracts) did not provide sufficient information on outcomes or present outcome data in a form that we were able to use in the review.

Risk of bias in included studies

The overall quality of the included studies was difficult to assess as many of the studies gave very little information about the methods used.

Allocation

The method of sequence generation was often not mentioned in the included studies. In the studies by Miquelutti 2007 and Vallejo 2001, a computer generated list of random numbers was used; five of the included studies utilised a quasi-randomised design, where the allocation to groups was according to hospital or case-note number or by alternate allocation (Calvert 1982; Chan 1963; Chen 1987; Haukkama 1982; Williams 1980); for the rest, the method of sequence generation was not stated.

The methods used to conceal group allocation from those recruiting women to the trials were also frequently not described. Six studies referred to group allocation details being contained in envelopes; in the studies by Collis 1999, MacLennan 1994 and Miquelutti 2007 the envelopes were described as sealed and opaque, and in the other studies envelopes were variously described as plain, numbered or sealed (Frenea 2004; McManus 1978). In sensitivity analysis where studies of better and poorer quality have been separated, we regarded the six studies which give details of allocation concealment as the better quality studies, while we regarded those studies where allocation concealment was inadequate (e.g. in the quasi-randomised studies) or where methods were unclear as of poorer quality.

Blinding

In interventions of this type, blinding women and clinical staff to group allocation is not generally feasible. It is possible to have partial blinding of outcome assessors for some types of outcomes, but it was not clear that this was achieved in any of the included studies. The lack of blinding may introduce bias, and this should be kept in mind in the interpretation of the results.

Incomplete outcome data

Details regarding loss to follow up are set out in the risk of bias tables. In general, loss to follow up was not a serious problem in these studies, as many of the outcomes were recorded during labour.

In one study (Chen 1987), there was a high level of post-randomisation exclusion in both study groups (37%). This study was also at high risk of bias because of poor allocation concealment. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to examine the effects on results of excluding this study, along with those others at high risk of bias for poor or unclear allocation concealment.

In one study we did not use the whole sample in the analyses. In the study by Phumdoung 2007, women were randomised into five separate groups (see Characteristics of included studies for a description of the groups); we selected the two groups which we thought best represented upright and recumbent positions to include in the analyses.

Other potential sources of bias

There was wide variation in the types of interventions tested in these studies. Some authors gave very little information on the intervention, for example at what stage in labour it was started, what exactly women were asked to do and what instructions were given to women in the control groups. This lack of detail means that the interpretation of results is not simple. Further, co-interventions in included studies also varied. Readers should bear this variability in mind when reading the results of the review.

Effects of interventions

Upright positions (including sitting, standing, walking and kneeling) versus recumbent positions - 16 trials, 2530 women

Duration of labour

Duration of the first stage of labour

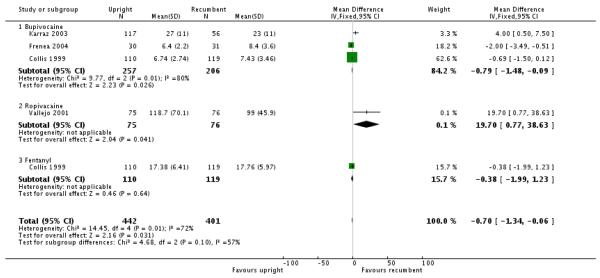

The duration of the first stage of labour varied considerably within and between trials. There were high levels of heterogeneity when studies were pooled (I2 = 79%). Hence, results need to be interpreted with caution, and in view of high levels of heterogeneity, we have used a random effects model for these analyses.

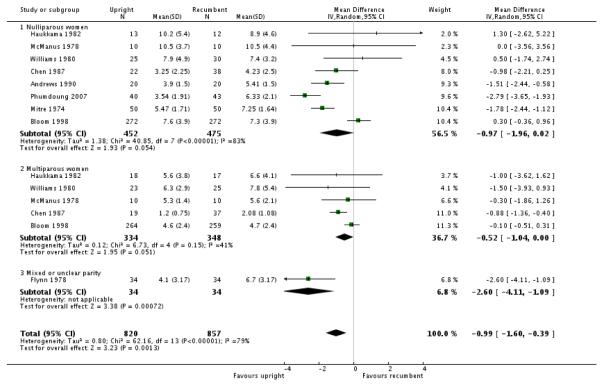

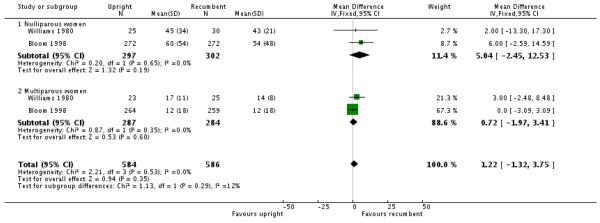

Overall, for all women, the first stage of labour was approximately one hour shorter for those randomised to upright compared with supine and recumbent positions; this analysis included pooled results from nine trials (including 1677 women) and the difference between groups was statistically significant (MD −0.99, 95% CI −1.60 to −0.39) (Analysis 1.1).

For nulliparous women, the length of the first stage of labour was not significantly different between groups; for multiparous women, the duration of first stage was approximately half an hour shorter for those randomised to upright positions, but the evidence of a difference between groups did not reach statistical significance.

Duration of the second stage of labour

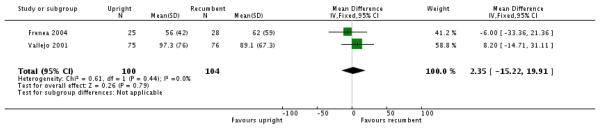

There was no difference between groups in the length of the second stage of labour in the two trials that reported this outcome (Analysis 1.11).

Mode of birth

Spontaneous vaginal birth

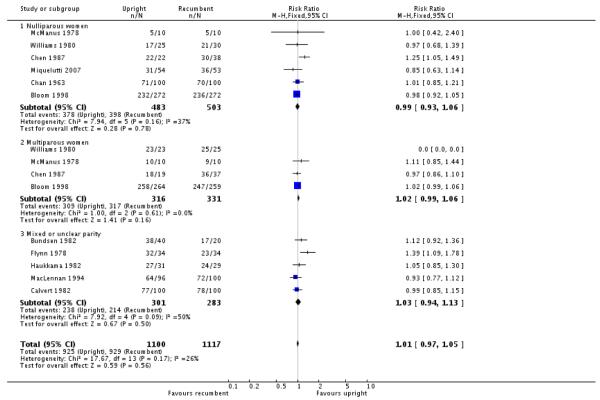

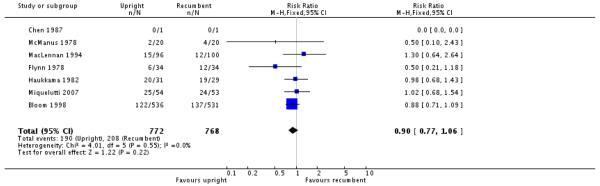

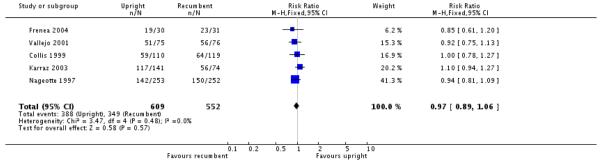

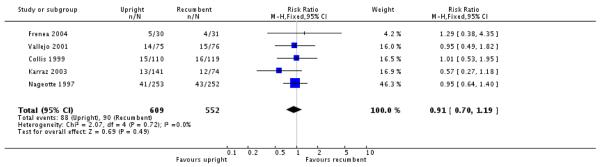

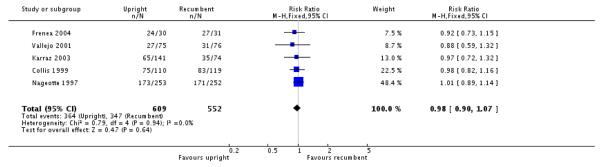

Results were similar for women randomised to upright versus recumbent positions, and this finding applied to both nulli- and multiparous women. There were no significant differences between groups in the numbers of women achieving spontaneous vaginal deliveries (Risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97 to 1.05) (Analysis 1.2).

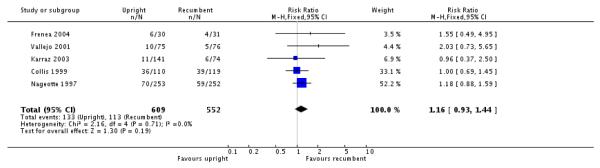

Operative spontaneous or assisted delivery

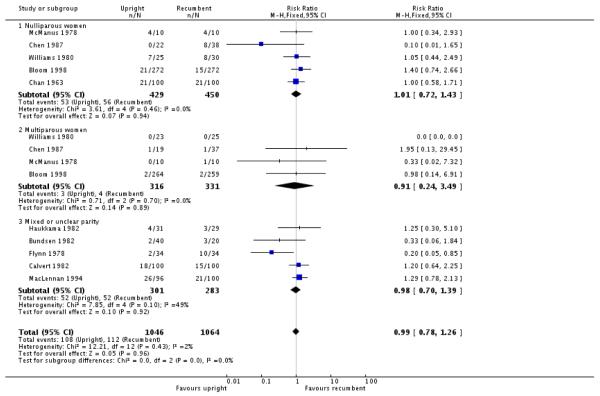

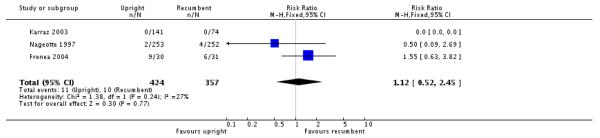

Women randomised to upright positions had similar rates of assisted deliveries compared with those randomised to recumbent positions (Analysis 1.3). Again, these results applied irrespective of parity.

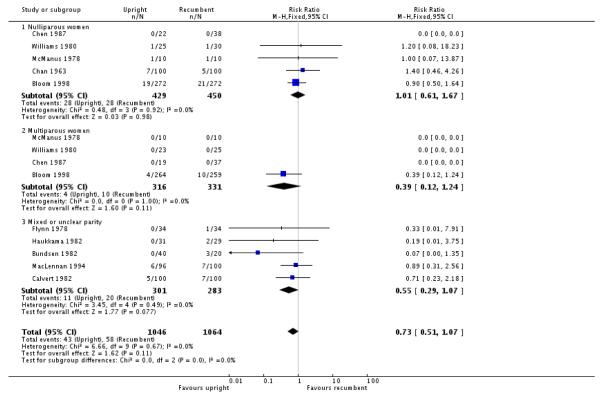

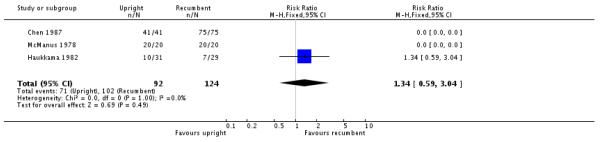

Caesarean delivery

Women encouraged to maintain upright positions had slightly lower rates of caesarean section compared with those in comparison groups. However, the strength of evidence was weak, and results did not reach statistical significance (overall RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.07) (Analysis 1.4).

Maternal satisfaction

While some studies collected information on satisfaction with specific aspects of care (e.g. satisfaction with pain relief), we were not able to pool results, as none of these studies collected information on women’s satisfaction with their general experience of childbirth.

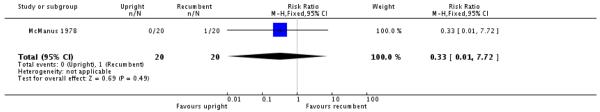

Maternal pain and analgesia

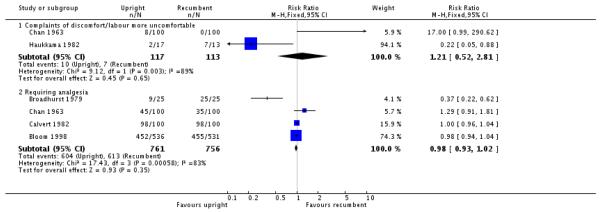

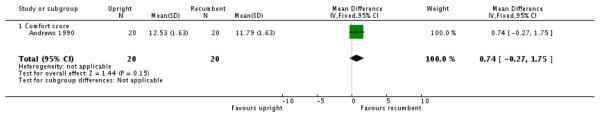

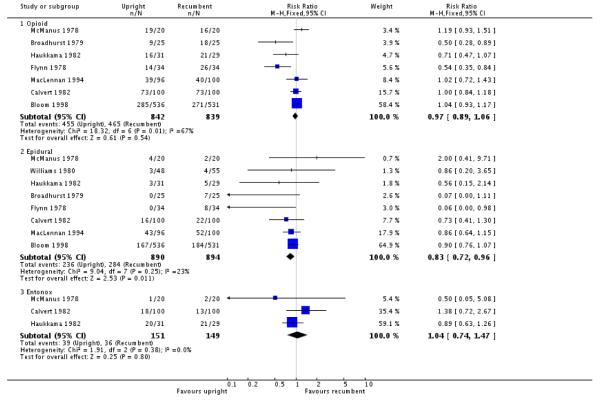

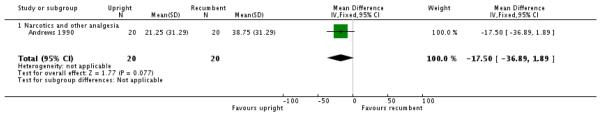

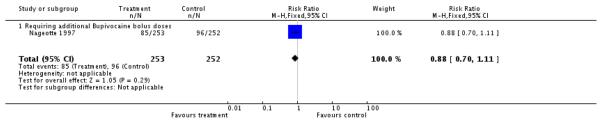

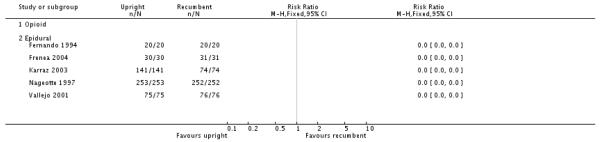

There were no differences identified between groups in terms of reported discomfort or requests for analgesia, although relatively few trials examined these outcomes, and findings were inconsistent. Most studies collected information on the types of analgesia women received. There were no differences between groups in terms of use of opioid analgesia, although women randomised to upright positions were less likely to have epidural analgesia, and this difference reached statistical significance (RR 0.83 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96, P = 0.01). The amount of analgesia received by women in the two groups was measured in one trial, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant (Analysis 1.10).

Interventions in labour

Augmentation of labour using oxytocin

Women randomised to upright versus recumbent positions had similar rates of augmentation of labour (Analysis 1.12). In two studies, amniotomy was carried out routinely on all women included (Chen 1987; MacLennan 1994); one study examined differences in amniotomy rates in women allocated to upright compared with recumbent positions. There were no differences between groups (Haukkama 1982).

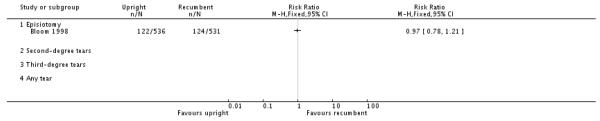

Maternal outcomes

Few studies reported maternal outcomes, so there was very little information on rates of post-partum haemorrhage and perineal trauma. Results from single trials suggest no significant differences between groups.

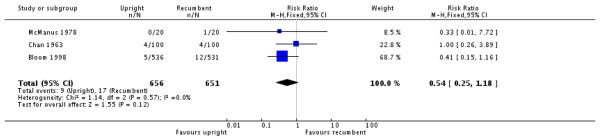

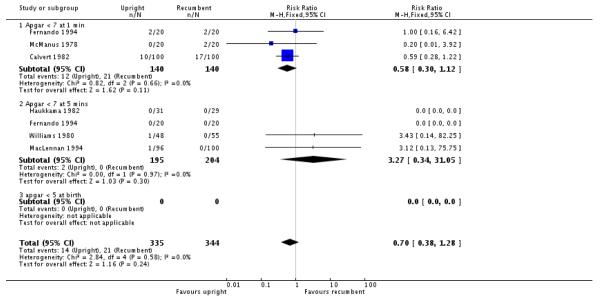

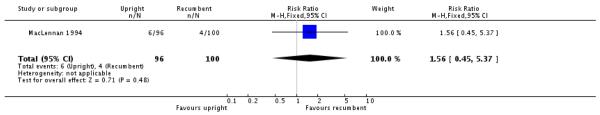

Fetal and neonatal outcomes

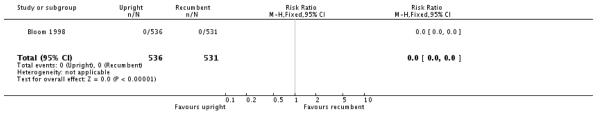

Again, there was little information from included studies on outcomes for babies. There were no significant differences between groups in terms of fetal distress and neonatal Apgar scores. Admission to special care units was only reported in one study and was slightly more likely for babies born to mothers randomised to upright positions, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (Analysis 1.20. One study examined perinatal deaths; no deaths in either group were recorded (Bloom 1998)

Upright (including walking) versus recumbent positions - with epidural (five trials, 1176 women)

Analysis for this comparison is for all women, irrespective of parity. We had planned subgroup analysis by parity; however, of the five trials contributing data, three recruited nulliparous women only (Collis 1999; Nageotte 1997; Vallejo 2001) and the remaining two studies did not report results separately for nulliparous and multiparous women (Frenea 2004; Karraz 2003).

Duration of labour

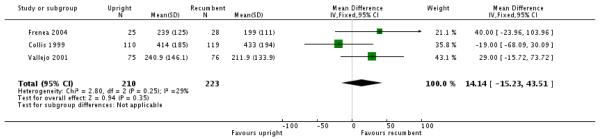

Duration of the first stage of labour

There were no differences between groups in terms of the length of the first stage of labour (i.e. time from epidural insertion to complete cervical dilatation) (Analysis 2.1).

Mode of delivery

Rates of spontaneous vaginal, assisted and caesarean delivery were similar for women randomised to upright versus recumbent positions (Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4).

Maternal pain, satisfaction and other outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of maternal satisfaction, women receiving oxytocin augmentation, women experiencing hypotension, women requiring additional analgesia, or the amount of analgesia women received (Analysis 2.5 to Analysis 2.14). However, few trials measured these outcomes and results are based on results from only one or two studies.

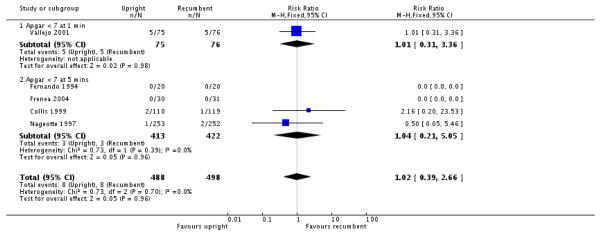

Neonatal outcomes

There was no information on perinatal mortality or admission to special care units (Analysis 1.20; Analysis 2.18 ). There were no differences between groups in the incidence of Apgar scores of less than seven at one and five minutes (Analysis 2.17).

Trials where ambulation was encouraged and trials where women were confined to bed or sitting

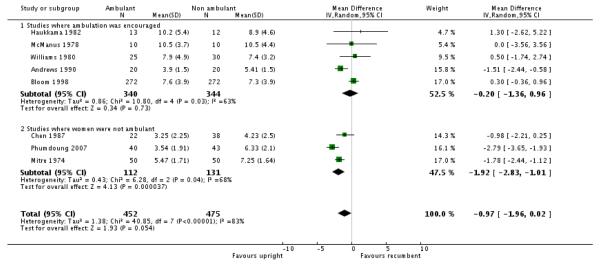

In order to address the question of whether standing and walking, rather than sitting or upright bed positions were associated with shorter length of labour, we carried out further analysis. In this analysis (Analysis 3.1) the majority of trials where women were encouraged to get out of bed and ambulate were analysed separately from the three trials (Chen 1987; Mitre 1974; Phumdoung 2007) where women were encouraged to sit or maintain non-ambulant positions. In this analysis we have only included nulliparous women as two of the three trials examining non-ambulant positions (Mitre 1974; Phumdoung 2007) only recruited such women, and the third provided separate data for these women. Results suggest that non-ambulant upright positions (sitting in bed or on a sofa, or semi-kneeling in bed) were associated with shorter labours compared with comparison groups (MD −1.92 95% CI −2.83 to −1.01) whereas, for studies examining ambulation, the difference between intervention and comparison groups was not significant (MD −0.20 95% CI −1.36 to 0.96). For each of these comparisons, the level of heterogeneity was high and we have used a random effects meta-analysis. Overall, I2 was 83% and there were differences in the direction of findings, and in the size of the treatment effect, so these results should be viewed with caution. As well as statistical heterogeneity, we suspected clinical heterogeneity, as there was wide variation in the mean length of labour in different studies. Further, the three studies where women maintained non-ambulant positions examined different types of intervention in different settings. All the women in the study by Mitre 1974 had amniotomies and were confined to bed. Women in the study byChen 1987 were provided with a settee and encouraged to sit on it, but could walk around if they wished to. In the Phumdoung 2007 study, women alternated between a semi-kneeling position and a semi-recumbent position. All of this variation means that it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the most favourable positions for women to adopt.

Subgroup analysis

Low- and high-risk groups

Data were not available to carry out this analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

For the primary review outcomes, we carried out a sensitivity analysis whereby those trials with poor allocation concealment (e.g. alternate group allocation) or where no information on allocation concealment had been provided, were taken out of the meta-analysis to see if this would change the direction of results or the size of the effect. For duration of length of first stage, only one trial was left when trials with a high risk of bias were removed. In this trial there were no significant differences in duration of the first stage of labour between the ambulant and comparison groups, irrespective of parity (MD −0.25, 95% CI −1.68 to 1.18) (McManus 1978). When all trials were included results had suggested a shorter duration of first stage for those women in the intervention groups. For mode of delivery, three trials were included ( MacLennan 1994; McManus 1978; Miquelutti 2007). Here, there were no significant differences between groups in terms of spontaneous vaginal, assisted vaginal or caesarean births. This finding was similar to that resulting from the inclusion of all trials.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this review were to assess the effects of positions and mobility during the first stage of labour on length of labour, type of delivery and other important outcomes for mothers and babies.

Women who were upright or mobile had a shorter first stage of labour compared with women who were supine (MD −0.99, 95% CI −1.60 to −0.39). Shorter length of labour is an important outcome, as every contraction is potentially painful. Women randomised to upright positions were also less likely to have epidural analgesia. However, there was little evidence that position or mobility had any effect on the rate of other interventions or on the wellbeing of mothers and babies.

When considering the results from the review, it is worth noting that designing trials to examine interventions in this area is challenging, and it is difficult to avoid bias. It is not possible to blind women and caregivers to group allocation. In addition, it is difficult to standardise interventions. For the trials included in the review, there was considerable variation in the interventions women received. Even where interventions appeared similar in different studies, it is likely that women’s experience varied; this sort of intervention cannot be easily controlled. Women may have had difficulty maintaining the intervention position or preferred alternative positions. There was also variation in caregiver behaviour in relation to study protocols; in some studies women were strongly encouraged by staff to mobilise (e.g. in the study by Miquelutti 2007, any woman in the intervention group that remained in bed for more than 30 minutes was asked to get out again); in other studies, women had more choice and more gentle encouragement. In one study the intervention was only encouraged during the day as it was not felt that women would like to walk around at night (Karraz 2003), and in this same study, women in the comparison group were not allowed out of bed even to walk to the toilet. Further, there was huge variability in the amount of time women actually followed the protocol in terms of ambulation or staying in bed. For example, in the Calvert 1982 study, less than half of the women in the intervention group chose to get out of bed at all, and those that did get out, only tended to do so for short periods of time. .

Heterogeneity in study findings also created problems in interpreting results. For the main outcome - length of the first stage of labour - there was considerable variation within and between studies in terms of group means. Various studies defined and measured the length of the first stage of labour in different ways. Measurement may have commenced on admission or at various points of cervical dilatation according to different hospital policies or study designs.

We were not able to answer several of the questions set out in the protocol. There were no studies comparing different types of upright position, e.g. sitting up in bed or on a chair versus walking or kneeling, or other upright positions. Results suggest that non-ambulant upright positions may reduce the length of labour, but only three studies (all with a high risk of bias) examined non-walking positions and results were difficult to interpret because of the variability of interventions.

Few of the studies collected outcome data on many of the review outcomes such as pain, maternal satisfaction, and neonatal outcomes. Most of the included studies collected information on mode of birth, but few had the statistical power to detect differences between groups.

Studies were carried out over a long period: from the early 1960s (Chan 1963) through to 2007 (Miquelutti 2007; Phumdoung 2007); and in a number of different healthcare settings. The cultural and healthcare context is likely to have been different at different times and in different settings, and there have also been changes in healthcare technologies. Within these changing contexts, the attitudes and expectations of healthcare staff, women and their partners towards pain, pain relief and appropriate behaviour during labour and childbirth have shifted. All of these factors are important in the interpretation of results.

This review needs to be looked at alongside other related Cochrane reviews focusing on care during labour (e.g. Cluett 2002; Gupta 2004; Hodnett 2007; Hunter 2007). While position in the first stage of labour may have an independent effect, the position in second stage and other variables (e.g. the presence of a birth companion) are also important.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Upright positions and walking are associated with a reduction in the length of the first stage of labour, and women randomised to upright positions may be less likely to have epidural analgesia, but there was little evidence of differences for other maternal and infant outcomes. Despite the limited evidence from trials included in the review, observational studies suggest that maintaining a supine position in labour may have adverse physiological effects on the woman and her baby (Abitbol 1985; Huovinen 1979; Marx 1982; Roberts 1989; Rooks 1999; Walsh 2000). Therefore, women should be encouraged to take up whatever position they find most comfortable while avoiding spending long periods supine. Women’s preferences may change during labour. Many women may choose an upright or ambulant position in early first stage labour and choose to lie down as their labour progresses.

Implications for research

Overall, the quality of the studies included in the review was mixed and most studies provided little information on methods. Minimising risk of bias in trials on this topic is challenging, as blinding is not feasible and it is difficult to standardise interventions. At the same time, some aspects of study design can be controlled.

Some considerations for future research are as follows.

There is a need for high-quality trials in this area, with particular attention given to allocation concealment.

Trialists should clearly explain how they have defined the first stage of labour.

There is a need to improve and standardise measurement of pain.

There is an urgent need to collect information on outcomes for mothers, such as satisfaction with the experience of childbirth, and more information is needed on pain and the effect of position on complications such as haemorrhage.

Few trials assessed outcomes for babies and future studies need to focus on this.

Studies are needed which compare different upright positions (e.g. sitting upright versus walking) and different lying positions (e.g. lying on side versus back).

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Mothers’ position during the first stage of labour

Women in the developed world and in health facilities in low-income countries usually lie in bed during the first stage of labour. Elsewhere, women progress through this first stage while upright, either standing, sitting, kneeling or walking around, although they may choose to lie down as their labour progresses. The attitudes and expectations of healthcare staff, women and their partners have shifted with regard to pain, pain relief and appropriate behaviour during labour and childbirth. A woman semi-reclining or lying down on the side or back during the first stage of labour may be more convenient for staff and can make it easier to monitor progression and check the baby. Fetal monitoring, epidurals for pain relief, and use of intravenous infusions also limit movement. Lying on the back (supine) puts the weight of the pregnant uterus on abdominal blood vessels and contractions may be less strong than when upright. Effective contractions help cervical dilatation and the descent of the baby.

The results of the review suggest that the first stage of labour may be approximately an hour shorter for women who are upright or walk around during the first stage of labour. The women’s body position did not affect the rate of interventions. The review authors identified 21 controlled studies from a number of countries that randomly assigned a total of 3706 women to upright or recumbent positions in the first stage of labour. Nine of the studies included only women who were giving birth to their first baby. The length of the second stage of labour and the numbers of women who achieved spontaneous vaginal deliveries or required assisted deliveries and augmentation were similar between groups, where reported. Use of opioid analgesia was no different, although women randomised to upright positions were less likely to have epidural analgesia. In those studies specifically examining position and mobility for women receiving epidural analgesia (five trials, 1176 women), an upright or recumbent position did not change the length of the first stage of labour (time from epidural insertion to complete cervical dilatation) or rates of spontaneous vaginal, assisted and caesarean delivery. Little information was given on maternal satisfaction or outcomes for babies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Philippa Middleton, Caroline Crowther, Lea Budden and Joan Webster for their advice on early versions of this review.

As part of the pre-publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s international panel of consumers and the Group’s Statistical Adviser.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Griffith University, School of Nursing, Nathan Campus, Queensland, Australia.

Centre for Clinical Studies - Women’s and Children’s Health, Mater Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

The University of Liverpool, UK.

University of Adelaide, Australian Research Centre for Health of Women and Babies, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

James Cook University, School of Midwifery and Nutrition, Townsville, Queensland, Australia.

University of Queensland, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

External sources

Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth Government, Canberra ACT, Australia.

National institute for Health Research, UK.

NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme award for NHS-prioritised centrally-managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS02

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 40 women randomised. Inclusion criteria - nulliparous women with a medically uncomplicated pregnancy with a single vertex fetus in an anterior position, spontaneous onset of labour at 38 to 42 weeks’ gestation, adequate pelvic measurements and intact amniotic membranes at the beginning of the maximum slope in their labour (4 to 9 cm dilatation) |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: 20 - upright: standing, ambulating, sitting, squatting, or kneeling. Comparison group: 20 - recumbent: supine, lateral, or prone - hands and knees. All women - position assumed when cervical dilatation was from 4 to 9 cm; women were free to choose several variations within each position group. Women in both groups were free to assume positions from the other group for routines of care or rest; these activities were documented |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage of labour. Pain. Analgesia amount. |

|

| Notes | Upright group - 15 women chose to lie down after receiving medication for rest; 5 of these women immediately returned to the upright position, stating that the contractions were more painful when they were lying down. The remaining 10 chose the lateral position to rest for up to 1 hour during the study period. Women in the recumbent position were monitored externally more often (n = 13) than women in the upright position (n = 1), which may have been an additional source of discomfort for women in the recumbent group |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomly assigned’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 1067 women randomised. Inclusion criteria - women (nulliparous and multiparous) with uncomplicated pregnancies between 36 and 41 weeks’ gestation and in active labour, having regular uterine contractions with cervical dilatation of 3 to 5 cm, and fetuses in cephalic presentation. Fetal membranes could be intact or ruptured. Exclusion criteria - women with any known complication of pregnancy, including breech presentations |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: 536 assigned to walking (walking as desired). Women were encouraged to walk but were instructed to return to their beds when they needed intravenous or epidural analgesia or when the second stage of labour began Comparison group: 531 to labour in bed (usual care - confined to a labour bed). Women were permitted to assume their choice of supine, lateral or sitting positions during labour All women - electronic fetal heart rate monitoring was not used routinely. Women whose fetuses had heart-rate abnormalities during routine surveillance conducted every 30 minutes with handheld Doppler devices, women who had meconium in the amniotic fluid, and women in whom labour was augmented by the administration of oxytocin underwent continuous electronic fetal monitoring, which prohibited further walking. Pelvic examinations were performed approximately every 3 hours - ineffective labour was suspected if the cervix did not dilate progressively during the first two hours after admission. If the fetal membranes were intact, amniotomy was performed. If a woman had hypotonic uterine contractions, and no further cervical dilatation after an additional 2-3 hours, labour was augmented by intravenous oxytocin (initial dose 6 mU per minute, increased every 40 mins by 6 mU per minute to a maximum of 42 mU per minute. Dystocia was diagnosed if labour had not progressed in 2-4 hours. In both study groups, the positions permitted during birth included the lateral (Sims’) position and the dorsal-lithotomy position, with or without obstetrical stirrups. Women in both groups wore pedometers (for the walking group only, nurses recorded the number of minutes spent walking) |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage labour. Length of second stage labour. Type of birth. Fetal distress. Analgesia. Augmentation. Perineal trauma. Fetal distress. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomly assigned’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow-up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 50 (8 primiparous and 17 multiparous in each group). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: 25 Comparison group: 25 - ambulation. - bed care. |

|

| Outcomes | Pain. Analgesia. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Describled as ‘randomly allocated’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 60 women undergoing induction of labour. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: 40 ambulation (telemetry). Comparison group: 20 bed care. All women: induced - primary amniotomy and immediate internal monitoring |

|

| Outcomes | Type of delivery. Pain. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomization to three groups’. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

No | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up apparent. |

| Methods | Quasi-randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 200 women randomised. Inclusion criteria - women with a single fetus of at least 37 weeks’ gestation; vertex presentation and no contraindication to vaginal birth; in spontaneous labour with uterine contractions occurring at least every 10 mins and a cervix at least 2.5 cm dilated. Exclusion criteria - women who had previously suffered a stillbirth or neonatal death or who had undergone a caesarean section |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: Ambulation with telemetry monitoring (women advised that they could get of bed to walk, sit in an easy chair or use the day room). Intervention group - ambulant women monitored with telemetry (n = 100). Comparison group - conventional cardiotocography (women nursed in bed) (n = 100). All women - all patients in bed were nursed in the lateral position or with a lateral tilt |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage. Type of delivery. Woman’s pain. Analgesia. Length of second stage. Apgar < 7 at 5 mins. |

|

| Notes | Telemetry group: 45% elected to get out of bed (and then only for short periods); average time out of bed = 1 hour 44 mins (range - 3 mins to 4 hours 20 mins) which was 30% of the monitored first stage of labour; 34 (75%) of those who left their beds initially elected to stay in bed by the time they reached a cervical dilatation of 7 cm | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | No | Described as ‘Final digit of hospital number (odd or even)’. |

| Allocation concealment? | No | Described as ‘Final digit of hospital number (odd or even)’. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Quasi-randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 200 women randomised. Inclusion criteria - primiparous. Exclusion criteria - planned elective caesarean section | |

| Interventions | Intervention group:100 women were kept in the erect postion (sit or walk). Comparison group: 100 women were kept in a supine or lateral position |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage. Type of delivery. Pain. Analgesia. Length of second stage. Fetal distress. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | No | Alternate group allocation. |

| Allocation concealment? | No | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | No loss to follow up. |

| Methods | Quasi-randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 116 women (185 women randomised, 116 included in the analyses). Inclusion criteria - women with uneventful pregnancies, full term, spontaneous labours, with a single fetus in cephalic presentation. Exclusion criteria - women received oxytocin augmentation; caesarean section due to cephalo-pelvic disproportion or fetal distress; women requested and received epidural anaesthesia; child with congenital anomalies; tococardiogram records were unsuitable for reading (n = 67 exclusions after group allocation) |

|

| Interventions | Amniotomy performed when cervical dilatation reached 3 to 4 cm. Intervention group (sitting): Women free to assume any comfortable position in homelike part of obstetric unit (furnished with desk, chair, sofa but no bed). Most sat on a sofa (back of sofa at 65 degree angle from horizontal) with their knees flexed. When each woman’s cervix became fully dilated, she was transferred to a birthing chair Comparison group (supine): Women to maintain dorsal or lateral recumbent position. No analgesia or anaesthesia used except for pudendal nerve block or perineal infiltration of xylocaine Experimental group (1): sitting position during the entire course of labour (n = 41). Comparison groups (2): supine position in the first stage and birthing chair in the second stage (n = 32); (3): supine position throughout labour (n = 43) |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage. Type of delivery. Length of second stage. ARM. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | No | Described as ‘Allocated following the order of their admission into the study’ |

| Allocation concealment? | No | Described as ‘Allocated following the order of their admission into the study’ |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | 67 participants were excluded after group allocation (37%). Some of the reasons for exclusion are unlikely to have related to the intervention (e.g. children born with congenital abnomalities) but other reasons may have related to group allocation (e.g. oxytocin augmentation, caesarean for fetal distress) |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 229 women (153 were in spontaneous labour and 76 had labour induced). Inclusion criteria - nulliparous women in spontaneous or induced labour who requested regional analgesia (given CSE); cephalic singleton pregnancy from 36 to 42 weeks’ gestation, with no other pregnancy complications, e.g. pregnancy-induced hypertension |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: encouraged to spend at least 20 mins of each hour out of bed (n = 110) - walking, standing, sitting in a rocking chair. Comparison group: encouraged to stay in bed (n = 119) - sitting up in bed or lying on either side. All women - continuous fetal monitoring. 500-1000 ml Hartmann’s solution infused as a preload; CSE - 27-G Becton-Dickinson Whitacre 119 mm spinal needle and 16-G Tuohy needle; long spinal needle inserted through Tuohy needle into cerebrospinal fluid (needle-through-needle CSE). Subarachnoid injection of 25 g fentanyl and 2.5 mg bupivacaine Labours were managed according to the department’s standard practice (cervical dilatation was assessed every 3 hours and if dilatation had not increased by 2 cm, amniotomy was performed; if the membranes were intact, this was followed 2 hours later (if progress of labour was still inadequate) by augmentation of labour with oxytocin. If the membranes were ruptured and inadequate progress of labour was noted, then oxytocin was started without waiting for another 2 hours. The mothers were allowed up to 2 hours in the second stage of labour. If at the end of the second hour, birth was not imminent, instrumental delivery was performed |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage. Type of delivery. Analgesia. Apgar. |

|

| Notes | 51/110 women in the intervention group achieved at least 30% of time out of bed, 15 women spent no time out of bed, 44 spent 1 to 29%, 32 spent 30-59% and 19 women spent > 60% of time out of bed. Reasons for not ambulating: 16 women developed motor block, fatigue in 25 mothers, midwife instruction in 10 cases. Comparison group: 16/119 women got of bed (15 between 1-29% of the time and 1 between 30-59% of the time. Reasons for ambulating: passing urine. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Described as ‘sealed opaque numbered envelopes’. |

| Blinding? Women | No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

Unclear | Described as ‘Obstetrician was not aware which group the mother was in’ |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Described as ‘Obstetrician was not aware which group the mother was in’ |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 40 nulliparous women receiving a CSE. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: out of bed (sitting in rocking chair, stand by bed, walk about) (n = 20). Comparison group: staying in bed (n = 20). All women - spinal injection of bupivacaine 2.5 mg and fentanyl 25 g using a 27 gauge, 1119 mm Becton-Dickinson Whitacre spinal needle through a 16 gauge Braun Tuohy needle, followed by epidural top ups of 10 mg bupivacaine in 10 ml with 2 g/ml of fentanyl |

|

| Outcomes | Apgar. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomly allocated’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 68 (17 primigravidae and 17 multigravidae in each group, 33 cephalic and 1 breech presentation in each group). Inclusion criteria - women in spontaneous labour. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: allowed to walk around while being continuously monitored by telemetry. When intravenous treatment was necessary (e.g. because of ketonuria or delay in labour) the women returned to bed. Comparison group: recumbent (nursed in the lateral position with conventional bedside monitoring of fetal heart and intrauterine pressure). All patients were nursed in bed during the second and third stages of labour. Dilatation of the cervix and station of the presenting part were assessed at the start of monitoring and every two to three hours during labour. Analgesia was administered when the midwife thought the woman was becoming distressed with pain. Augmentation in labour with oxytocin or prostaglandin was given when indicated by delay in labour |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage of labour. Type of delivery. Analgesia. Augmentation. Blood loss. Apgar. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomised prospective’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 61 women. Inclusion criteria - women with uncomplicated term singleton pregnancies from 37 to 42 weeks’ gestation in a fixed cephalic uncomplicated presentation, and 3 to 5 cm cervical dilatation at the time of epidural insertion. Women could be in spontaneous labour or admitted for elective induction. A normal fetal heart rate pattern was also required. Exclusion criteria - unfixed cephalic presentation, cervical dilatation more than 5 cm, a contraindication to epidural analgesia, or a systolic arterial blood pressure < 100 mmHg before epidural insertion, twin pregnancy, history of caesarean birth, and any known complications of pregnancy including breech presentation |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: ambulation (n = 30). Women were asked to walk at least 15 mins of each hour or for 25% of the duration of the first stage of labour. Ambulation was permitted 15-20 mins after the initial injection, provided there was no postural hypotension, no motor block in lower limbs, no proprioception impairment and no fetal heart rate decelerations. The women were asked to return to bed when they requested an epidural top-up or if they experienced weakness or sensory changes. Walking ended when examination by a midwife revealed full cervical dilatation. Comparison group: recumbent (n = 31). Confined to bed in dorsal or lateral recumbent position. Monitoring of labour was as for the ambulatory group, but without telemetry. Epidural analgesia of intermittent administrations of 0.08% bupivacaine-epinephrine plus 1 g/ml of sufentanil |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage of labour. Type of delivery. Analgesia. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Described as ‘sealed numbered envelopes’. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Quasi-randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 60 women. Inclusion criteria: healthy women with an uneventful pregnancy, giving birth between 38 and 42 weeks |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: cardiotocography by telemetry (n = 31). Telemetry women were encouraged to sit or walk during the opening phase of labour. Comparison group: conventional cardiotocography (n = 29). All women - nitrous oxide-oxygen, pethidine (usual dose 75 mg given once or twice) or epidural block were used for analgesia when needed |

|

| Outcomes | Length of first stage. Type of delivery. Analgesia. Augmentation. ARM. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as matched pairs ‘allocated at random’ to one of two groups |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 221 (144 nulliparas - 97 (69.3%) in the ambulatory group and 47 (63.5%) in the non-ambulatory group. Inclusion criteria: women with uncomplicated singleton pregnancies who presented in spontaneous labour between 36 and 42 weeks’ gestation or who were scheduled for induced labour. Study conducted in daytime only (as women in labour at night are less inclined to walk) Exclusion criteria - women with pre-eclampsia or previous caesarean |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: ambulatory (walked, sat in a chair or reclined in a semi-supine position (n = 141) - as long as they demonstrated: acceptable analgesia; acceptable systolic blood pressure and ability to stand on one leg. Comparison group: non-ambulatory (not allowed to sit, walk or go to the toilet); they had to remain in the supine position or to lie in a semi-supine or lateral position (n = 74). All - intermittent epidural injection of 0.1% ropivacaine with 0.6 μg/ml sufentanil. Repeat injections were given when the women requested additional pain relief |

|

| Outcomes | Length of labour. Type of delivery. Analgesia. Augmentation. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | ‘Randomly divided’in a 2:1 ratio. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | 6 women were excluded after randomisation. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 196 women. Inclusion criteria: women in spontaneous established labour (presence of regular contractions less than 10 mins apart and cervical dilatation of 3 cm or more) with a singleton fetus in a cephalic presentation between 37 and 42 weeks’ gestation who had the ability to ambulate in labour. Exclusion criteria: women undergoing intravenous therapy, with hypertension (> 90 mmHg diastolic blood pressure), epidural or narcotic analgesia at or before entry to trial, evidence of possible fetal distress, previous prostaglandin treatment, induced labour and a physical inability to ambulate |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: ambulate as desired (n = 96). Women were encouraged to ambulate but were also given the option of sitting or lying down when they wished. Comparison group: recumbent. Most women chose a semi-recumbent posture with the head end of the bed at 45 degrees but they could also be on their side with lower elevation of the head. After entry to the trial, all women had an artificial rupture of the membranes if they had not already spontaneously ruptured |

|

| Outcomes | Type of delivery. Analgesia. Augmentation. Apgar. Admission to NICU. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Described as ‘Balanced variable blocks with stratification by parity’ |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 40 women (20 primigravidas and 20 having their second or third confinement). Inclusion criteria - gestational age 38 weeks or more, and cervical score 6 or greater. Exclusion criteria - multiple pregnancies or breech presentations |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: upright - encouraged to “be up and about”. If woman wished to go to bed, she was nursed in a sitting position with the aid of pillows. Comparsion group: recumbent - nursed in the lateral position Labour was induced by forewater amniotomy and 0.5 mg PGE2 immediately after amniotomy and hourly thereafter until labour was considered to be established. If labour was not established an hour after the 6th PGE2 tablet (i.e. 6 hours after amniotomy), intravenous oxytocin was given |

|

| Outcomes | Type of delivery. Analgesia. Augmentation. ARM. Blood loss. Fetal distress. Apgar. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomised prospective study’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomly allocated according to the contents of a plain envelope’ |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 107 women attending a hospital in Brazil (2005-6). Inclusion criteria - low-risk nulliparous women, at term, in labour, aged 16-40 years. Cervical dilation between 3cm and 5cm. Singleton fetus in cephalic presentation Exclusion criteria - contraindications to upright position or booked for elective caesarean section |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group - (n = 54) women received written information/education involving the use of models on the benefits of maintaining an upright position and encouraged to stand, walk, sit, crouch or kneel. If women remained supine for more than 30 minutes they were encouraged to return to an upright position Comparison group - (n = 53) routine care, women were not encouraged to adopt any position and were allowed to move around and adopt any position they chose |

|

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, duration of labour, augmentation, episiotomy, Apgar score, maternal preferences | |

| Notes | Women in the intervention group remained upright for 57% of the time compared to 28% for women in the comparison group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer generated. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Sealed, opaque envelopes opened sequentially. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

No | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Few women lost to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 100 women. Inclusion criteria - women who had been admitted to the labour room and had term pregnancies; were in the latent phase of labour or the active phase with the cervix between 1 and 3 cm; no medical stimulation of labour was required; no evidence of cephalopelvic disproportion; no history of surgery or trauma to the cervix; normal prenatal course; cephalic presentation |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: sitting (n = 50). All women were allowed to sit up after the amniotomy had been performed and the presenting part was engaged. The women were allowed to lie down from time to time, if they desired. Comparison group: supine (n = 50). All women were placed in the supine position and allowed to turn on their sides. Direct fetal and maternal monitoring was performed randomly on several women in both groups, using a choriometric unit |

|

| Outcomes | Length first stage labour. Apgar. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘divided randomly into two groups’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 761 (total of 3 arms; only 2 arms (n = 505) used here. Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women in spontaneous labour or with spontaneous rupture of membranes at 36 weeks or more with a fetus in the vertex position, who requested epidural analgesia |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: ambulation encouraged (n = 253). Ambulation was defined as a minimum of five mins of walking per hour. Comparison group: ambulation discouraged (n = 252). All women had CSE. All women received a minimum of 1000 ml of lactated Ringer’s solution intravenously during the 30 mins preceding the placement of the epidural needle. CSE - intrathecal narcotic with a continuous low-dose epidural infusion. After the location of the epidural space with an 18-gauge Tuohy needle, a 11.9 cm 27-gauge Whitacre spinal needle was passed through the epidural needle into the subarachnoid space. Then 10 g of sufentanil in 2 ml of normal saline was infused and the spinal needle removed. An epidural catheter was advanced 3 cm into the epidural space and a continuous infusion of 0.0625 % bupivacaine with 2 g of fentanyl per millilitre was given at a rate of 12 ml per hour. Subsequent bolus doses of epidural solution were given as requested (12 ml of 0.0625% bupivacaine) |

|

| Outcomes | Type of delivery. Pain. Hypotension. Apgar. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Described as ‘randomly assigned’. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not stated. |

| Blinding? Women |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Clinical staff |

No | Not feasible. |

| Blinding? Outcome assessor |

Unclear | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | No losses to follow up. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. Randomised in blocks. | |

| Participants | Women recruited from a hospital in Southern Thailand. (2 groups used in this analysis (n = 83)) Inclusion criteria - married, primiparous women aged 18 - 35 years and in latent phase for > 10 hours. Singleton fetus, cephalic presentation, gestation 38 - 42 weeks, fetal weight 2500 - 4000 g Exclusion criteria - had analgesia before recruitment, induced labour, membrane rupture > 20 hours previously, psychiatric problem, infection, asthma or objection to intervention |

|

| Interventions | 5 separate intervention groups (described below). In this review we have included data from two groups: Intervention group - CAT position alternating half hourly with head high position (CAT position = facing towards bed head at 45 degrees with knees bent, taking weight on knees and elbows; head high position = lying at a 45-degree angle) (n = 40) Comparison group - supine in bed (n = 43). |

|

| Outcomes | Duration of first stage. Pain. |

|

| Notes | Complicated study design with five study groups: 1. CAT position alternating with head-high position with music (n = 40). 2. CAT position alternating with head-high position (n = 40). 3. CAT position alternating with supine position (n = 40). 4. Head-high position (lying in bed on back at 45 degrees) (n = 41). 5. Supine in bed (n = 43). In this review we have used data for groups 2 and 5 in the analyses (It was not clear what ‘CAT’ signified) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Described as ‘random assignments’. |

| Blinding? Women |