Abstract

Background

Reducing high blood cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in people with and without a past history of coronary heart disease (CHD) is an important goal of pharmacotherapy. Statins are the first-choice agents. Previous reviews of the effects of statins have highlighted their benefits in people with coronary artery disease. The case for primary prevention, however, is less clear.

Objectives

To assess the effects, both harms and benefits, of statins in people with no history of CVD.

Search methods

To avoid duplication of effort, we checked reference lists of previous systematic reviews. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 1, 2007), MEDLINE (2001 to March 2007) and EMBASE (2003 to March 2007). There were no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of statins with minimum duration of one year and follow-up of six months, in adults with no restrictions on their total low density lipoprotein (LDL) or high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and where 10% or less had a history of CVD, were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies for inclusion and extracted data. Outcomes included all cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal CHD, CVD and stroke events, combined endpoints (fatal and non-fatal CHD, CVD and stroke events), change in blood total cholesterol concentration, revascularisation, adverse events, quality of life and costs. Relative risk (RR) was calculated for dichotomous data, and for continuous data pooled weighted mean differences (with 95% confidence intervals) were calculated.

Main results

Fourteen randomised control trials (16 trial arms; 34,272 participants) were included. Eleven trials recruited patients with specific conditions (raised lipids, diabetes, hypertension, microalbuminuria). All-cause mortality was reduced by statins (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.96) as was combined fatal and non-fatal CVD endpoints (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.79). Benefits were also seen in the reduction of revascularisation rates (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.83). Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were reduced in all trials but there was evidence of heterogeneity of effects. There was no clear evidence of any significant harm caused by statin prescription or of effects on patient quality of life.

Authors’ conclusions

Reductions in all-cause mortality, major vascular events and revascularisations were found with no excess of cancers or muscle pain among people without evidence of cardiovascular disease treated with statins. Other potential adverse events were not reported and some trials included people with cardiovascular disease. Only limited evidence showed that primary prevention with statins may be cost effective and improve patient quality of life. Caution should be taken in prescribing statins for primary prevention among people at low cardiovascular risk.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Cardiovascular Diseases [blood; *prevention & control]; Cause of Death; Cholesterol, HDL [blood]; Cholesterol, LDL [blood]; Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]; Primary Prevention; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Burden of cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a wide range of disease including ischaemic heart disease, coronary heart disease (e.g. heart attack), cerebrovascular disease (e.g. stroke), raised blood pressure, hypertension, rheumatic heart disease and heart failure. The major causes of CVD are unhealthy diets, tobacco use and physical inactivity (WHO 2008).

CVD is ranked as the number one cause of mortality and is a major cause of morbidity world wide accounting for 17 million deaths, 30% of total deaths. Of these, 7.6 million are due to heart attacks and 5.7 million due to stroke (WHO 2008). Over 80% of CVD deaths occur in low and middle income countries (WHO 2008). In developing countries, it causes twice a many deaths as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis combined (Gaziano 2007). It has been estimated that between 1990 and 2020, the increase in ischaemic heart disease alone will increase by 29% in men and 48% in women in developed countries and by 120% in women and 127% in men in developing countries (Yusuf 2001). CVD imposes high social costs, including impaired quality of life and reduced economic activity, and accounts for a large share of health service resources (Gaziano 2007).

CVD is multi-factorial in its causation and lifestyle changes are the basis of any treatment strategy, with patients often requiring behavioural counselling. Those unable to achieve or maintain adequate risk reduction on lifestyle changes alone or those at high risk patients require pharmacotherapy. Reducing high blood cholesterol (hypercholesterolaemia), a risk factor for both fatal and non-fatal CVD events in people with and without a past CVD, is an important goal of pharmacotherapy (Prospective Studies Collaboration 2007). Statins are the first-choice agents for Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction. The level at which blood cholesterol is treated is more dependent on the absolute reduction in risk that can be expected, given the patient’s other risk factors, and taking into account the resources available for prevention (Ramsay 1996). Since the relation between blood cholesterol and cardiovascular risk is a continuous one (Chen 1991) (although J-shaped in some studies for total mortality), there is no definite threshold above which patients must be treated a priori. If a threshold for ‘high’ cholesterol is set at over 3.8 mmol/L, (146.9 mg/dL) this would contribute 4.4 million deaths world-wide and 40.4 million DALYs (disability adjusted life years) (Ezzati 2002). Furthermore, the average level of blood cholesterol within a population is an important determinant of the CVD risk of the population. Differences in average levels of blood cholesterol between populations are largely determined by differences in diet, and countries with high dietary saturated fat intake and a low ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids have higher than average cholesterol levels (Davey Smith 1992).

Trial evidence

Since the early statin trials were reported, several reviews of the effects of statins have been published highlighting the benefits of their use (Bartlett 2003; Blauw 1997; Briel 2004; Cheung 2004; Ebrahim 1999; Katerndahl 1999; LaRosa 1994; LaRosa 1999; Law 2003; Pignone 2000; Silva 2006; Thavendiranathan2006; Ward 2007; Wilt 2004). In particular, an individual patient data review and meta-analysis of 90,056 participants in 14 large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including the large Heart Protection Study (HPSCG 2003), followed up for 5 years, concluded that statins were beneficial in reducing the risk of CVD events in people at risk, and showed consistency of treatment benefits across a wide range of patient subgroups (Baigent 2005). The evidence on the beneficial effects of statins has led expert committees to promote their use on a global scale particularly in the developed world. (Manuel 2006; NICE 2006). Statin prescribing and expenditure have risen rapidly as a result. For example, the European average (weighted by population of each country) increased from 11.12 defined daily doses/1000 in 1997 to 41.80/1000 in 2002, an average 31% increase a year (Walley 2004). The expenditure on statin drugs in England was over £20 million in 1993, over £113 million in 1997 (Ebrahim 1998) and has risen to more than £500 million in 2006 (NICE 2006).

Adverse effects of lowering cholesterol with statins

There has been some concern that low levels of blood cholesterol increase the risk of mortality from causes other than coronary heart disease, including cancer, respiratory disease, liver disease and accidental/violent death. Several studies have now demonstrated that this is mostly, or entirely, due to the fact that people with low cholesterol levels include a disproportionate number whose cholesterol has been reduced by illness - early cancer, respiratory disease, gastrointestinal disease and alcoholism, among others (Iribarren 1997; Jacobs 1997). Thus it appears to be the pre-existing disease which causes both the low cholesterol and raised mortality (Davey Smith 1992).

The potential adverse effects of statins among people at low risk of CVD are poorly reported and unclear (Jackson 2001) but, among those with pre-existing CVD, the evidence suggests that any possible hazards are far outweighed by the benefits of treatment. Two reviews of 18 and 35 trials respectively found that there were similar rates of serious adverse events with statins as compared to placebo (Kashani 2006; Silva 2006) and a further review of 26 RCTs concluded that there was no effect on risk of cancer with statins (Dale 2006). Other adverse events have been investigated and may be causal, for example rhabdomyolysis - break down of muscles - which can be serious if not detected and treated early (Beers 2003). However, in a systematic review of statins with about 35,000 people and 158,000 person years of observation in both treated and placebo groups, rhabdomyolysis was diagnosed in eight treated and five placebo patients, none with serious illness or death (Law 2003). One RCT of 621 adults found that statins did not adversely affect self reported quality of life, mood, hostility psychological well being or anger expression (Wardle 1996). Small decrements in scores on tests of psychomotor speed and attention were found by Muldoon et al in an RCT of 209 adults, but Muldoon concluded that more research is needed to fully evaluate this (Muldoon 2000). In addition, a systematic review of five statin trials (N = 30,817) found no evidence that statins increased risk of death from non-illness mortality (accidents, violence or suicide) (Muldoon 2001).

Limitations of the reviews of the effects of statins

A major limitation of the evidence summaries to date is the emphasis of the use of statins in secondary prevention of CVD without distinguishing between findings in primary prevention trials. More recently, however, a number of systematic reviews have focused their attention of the use of statins in primary prevention but they differ in their interpretation of the evidence to date (Brugts 2009; Ebrahim 1999; Mills 2008; NICE 2006; Thavendiranathan2006; Vrecer, 2003; Ward 2007). This is largely due to the differing inclusion criteria of the reviews and differences in reporting of outcomes. Where the most recent systematic review (Baigent 2005, Brugts 2009; Mills 2008) promote the use of statins in the primary prevention of CVD (the latter team of authors received industry sponsorship), the evidence remains less clear leading other authors to conclude that the assumed benefits of statin therapy in secondary prevention trials should not be extrapolated to primary prevention populations and that current cholesterol treatment guidelines based on this assumption need to be revised (Abramson 2007).

The aim of this systematic review is to assess the effects of statins for primary prevention of CVD. We planned to look for adverse events associated with statins and examine effects in populations such as elderly people and women.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effects, both harms and benefits, of statins in people with no history of CVD events.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing treatment with statins for at least 12 months with placebo or usual care. Length of follow-up of outcomes had to be at least six months.

Types of participants

Men and women (aged 18 or more) with no restrictions on total, low or high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. We limited our inclusion of study population to have less or equal to 10% of a previous history of CVD.

Types of interventions

Statins (HMG CoA reductase inhibitors) versus placebo or usual care.

Concommitant interventions

Drug treatments and other interventions were accepted provided they are given to both arms of the intervention groups. Adjuvant treatments with one additional drug where a patient developed excessively high lipids during the trial were accepted.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were collected:

death from all causes;

fatal and non-fatal CHD, CVD and stroke events;

combined endpoint (fatal and non-fatal CHD, CHD and stroke events);

change in blood total cholesterol concentration;

revascularisation;

adverse events;

quality of life;

costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

As previous comprehensive reviews (Bartlett 2005; Ebrahim 1999; Ward 2007) have been undertaken we built on this work. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on The Cochrane Library (Issue1, 2007), MEDLINE (2001 to March 2007) and EMBASE (2003 to March 2007). A standard RCT filter was used for MEDLINE (Dickersin 1994) and EMBASE (Lefebvre 1996). No language restrictions were applied to either searching or trial inclusion. See Appendix 1 for search strategies. Reference lists of identified review articles and of all included RCTs were searched to find other potentially eligible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection

Two reviewers independently read the results from searches on electronic databases to identify those articles relevant to this systematic review based on title or title and abstract. Full articles were retrieved for further assessment. The articles were read independently by two reviewers and a form was designed to describe the characteristics of studies to be included or excluded as set out in the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook 5.0.2 (Higgins 2009).

Assessment of risk of bias

We used criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews 5.0.2 (Higgins 2009) to describe the quality of trials we found. Two authors independently assessed methodological quality of selected studies (FT, KW). Any differences of opinion were resolved by discussion and consensus and finally by discussion with a third author (SE). To assess any risk of bias we focused on the following dimensions as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook:

Adequate sequence generation (such as computer generated random numbers and random number tables, whilst inadequate approaches included the use of alternation, case record numbers, birth dates or days of the week).

Adequate measures to conceal allocation. Concealment was deemed adequate where randomisation is centralised or pharmacy-controlled, or where the following are used: serially numbered containers, on-site computer-based systems where assignment is un-readable until after allocation, other methods with robust methods to prevent foreknowledge of the allocation sequence to clinicians and patients.

Blinding was deemed adequate if blinding was applied (whether the participant, care provider or outcome assessors)

Completeness of outcome data was deemed adequate if intention to treat analysis was performed for each outcome and not what patient numbers the analysis was confined to.

Free of selective reporting: was deemed adequate if all stated outcomes were reported on and presented. We will highlight any selective outcome reporting.

A risk of bias graph for each trial was made available to assess quality.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was designed and included:

study ID;

quality;

participant baseline characteristics;

intervention dosage and duration.

To assess baseline risk of CVD the following median/mean values were also extracted:

age;

gender ratio;

proportion of current smokers;

total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol.

Outcome measures extracted included:

Primary outcome measures

death from all causes;

fatal and non-fatal CHD events,

fatal and non-fatal CVD events

fatal and non-fatal stroke events;

combined endpoint (fatal and non-fatal CHD, CHD and stroke events);

Secondary outcome measures

change in blood total cholesterol concentration;

revascularisation;

adverse events;

quality of life.

costs.

Data was extracted by two reviewers independently (FT, KW). Any differences of opinion were resolved by discussion and consensus and finally by discussion with a third reviewer (SE).

Contacting trialists

For unpublished studies or where data was incomplete in published papers, attempts were made to contact the authors to obtain further details.

Data analysis

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for dichotomous data. Quantitative analyses of outcomes was based on ‘intention to treat’ (ITT). For continuous data (such as change in blood total cholesterol), pooled weighted mean differences (with 95% CI) were calculated.

We did not add the number of fatal and non-fatal clinical events together from any of the studies that we included in this review as it was not possible to ascertain whether an individual who had a non-fatal clinical event followed by a fatal clinical event was counted as a clinical event under both categories. As a result we have only included the composite of fatal and non-fatal clinical events if this was reported in the papers. For example, number of stroke events: seven trials reported this as a composite outcome, one reported on fatal and one on non-fatal stroke events. We did not add the fatal and non-fatal strokes together to ascertain a composite number.

Heterogeneity

Because trials found may not have been carried out according to a common protocol there will usually be variations in patient groups, clinical settings, concomitant care etc. We, therefore, assessed heterogeneity between trial results. Trial data was considered to be heterogeneous where the I2 statistic was > 50%. For analysis we used the conservative, fixed effects method unless where data was heterogenous in which case we used the random effects model. Where significant heterogeneity was present, we attempted to explain the differences based on the patient clinical characteristics and interventions of the included studies.

Publication or other bias

A funnel plot was used to test for the presence of publication bias based on the data for the primary outcome of all cause mortality. Publication bias is usually detected by asymmetry of the funnel plot (Sterne 2001).

Analyses for potential effect modifiers was initially considered but abandoned due to lack of adequate reporting. These were to included:

gender;

extent of hyperlipidaemia;

age under 65, 65 and over.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was used to explore the influence of the following on effect size:

repeating analysis taking account of study quality;

repeating analysis excluding any very long/large studies to see how they influence the results.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

After removal of duplicates, 4227 references were identified. From reading titles and abstracts 4128 were eliminated as being not relevant to the review. Full papers were obtained for 99 references. From these 99 papers, 72 papers reporting on 48 studies were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies). A total of 27 papers reporting on 14 trials were included (see Characteristics of included studies). Checking the references of the recent systematic reviews found 1 further trial (JUPITER 2008) which was published outside the dates of our search, details of which are listed in the Table: Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. Of the 14, trials, two tested two different interventions; for the purpose for meta analysis, each trial was counted as two trials (in total 16 trial arms) (CELL A 1996; CELL B 1996; PHYLLIS A 2004; PHYLLIS B 2004). The trials dated from 1994 to 2006 and were conducted world-wide, mainly in industrially developed countries (Japan, USA and Europe). Twelve trials recruited patients with specific conditions: eight recruited participants with raised lipids, three with diabetes, two with hypertension and one with microalbuminuria

All tested the effectiveness of a statin compared with placebo; nine tested pravastatin 10-40mg per day; one atorvastatin 10mg per day; two fluvastatin 40-80mg per day; two lovastatin 20-40mg per day and the remaining simvastatin 40mg per day. Five trials also included advice, counselling or information on health behaviour modification such as diet, smoking cessation, exercise.

In total, the 14 trials (with 16 trial arms) recruited 34,272 participants and observed outcomes ranging from 1-5.3 years, amounting to approximately 113,000 patient years. The size of the population recruited ranged from 47- 8,009. The mean age of the participants was 57 years (range 28-80 years), 65.9% were male and of the five trials which reported on ethnicity; 91.4 % were Caucasian.

Two trials (AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1998 and CARDS 2004) were stopped prematurely because significant reductions in primary composite outcomes between the intervention and placebo had been observed. These trials had recruited 27.1% of the total study population and were stopped 1.4-2.0 years before the official end date. We were unable to estimate the number of potential patients years of observation lost due to incomplete provision of data.

Data on all cause mortality was provided in eight trials. Excluding the two trials whose primary outcome was change in size of carotid artery, eight of the remaining trials chose a composite outcome as their primary outcome. Despite this, seven provided data on fatal and six on non-fatal CHD events and two on fatal and one on non-fatal CVD events. Whilst eight trials reported on combined stroke events, one provided data on non-fatal and one on fatal stroke events. Nine trials provided data on cholesterol and seven on adverse events. One provided economic costings, one provided data on patient perceived quality of life Five trials provided data on compliance: of those on statins, compliance ranged from 67%-92% whilst for those on placebo 53%-93%.

Excluding the 3 trials which solely recruited participants with diabetes; 1-20% accounted for diabetics the other trials. Excluding the two trials which recruited participants with hypertension; the remaining studies had recruited 15-67% with hypertension. The proportion of participants smoking ranged from 10-44% in the 13 trials which provided this data. We were unable to ascertain baseline lipid levels for three trials. Baseline total cholesterol levels ranged from 5.00-6.97 mmol/l (median 6.05 mmol/l), HDL cholesterol from 1.07-1.46 mm/l (median 1.24 mm/l) and LDL cholesterol from 2.92-4.95 mm/l (median 3.95mm/l).

Risk of bias in included studies

Four of the 16 trial arms did not provide adequate information on the methods used for randomisation, three of which had recruited more than 2000 participants. Fourteen trials used blinding to reduce bias, 10 of which used double blinding methods. Ten used intention to treat analysis and the drop out rates for those that did apply was ranged from 2-17% (only two trials provided such data). We judged 13 of the trials to be free from selective bias. (Figure 1; Figure 2). The MRC/BHF only provided data on total CVD events for patients with diabetes in the primary prevention group, whilst HYRIM did not present baseline and four-year follow-up data on cholesterol.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

The funnel plot for all cause mortality showed no sign of publication bias (Figure 3). Only one trial was funded from taxation (Ministery of Health) whilst the authors of nine trials reported having been sponsored either fully or partially by pharmaceutical companies (five by Bristol Myers and Squibb; two by Pfizer).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Mortality and Morbidity, outcome: 2.1 Total Mortality.

Effects of interventions

All cause mortality (Analysis 2.1)

Eight trials with 28,161 participants recruited reported on total mortality. During observation, 794 (2.8%) died with a death rate of 1.0 per 100 person years of observation in the control groups. None of the individual trials showed strong evidence of a reduction in total mortality but when the data were pooled using a fixed effects model, a relative risk reduction which favoured statin treatment by 16% was observed: (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.96). No heterogeneity was observed.

Fatal and non-fatal CHD events (Analysis 2.2, Analysis 2.3 and Analysis 2.4)

Nine trials with 10 arms and 27,969 participants reported on combined fatal and non-fatal CHD events: Four trials showed evidence of a reduction in this combined outcome which was maintained in the pooled analysis using a fixed effects model: 1,577 (5.63%) events; RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.65-0.79).

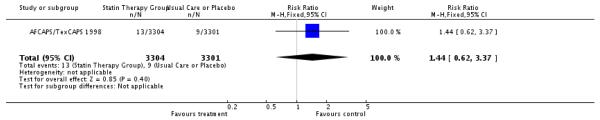

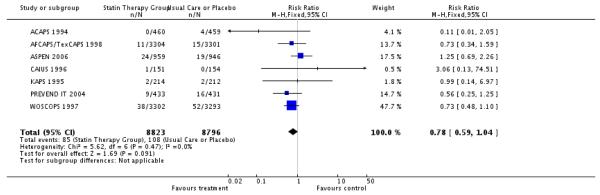

Observations on fatal or non-fatal CHD events are based on less than 55% of the participants recruited. Of the two trials which had been stopped prematurely, only AFCAPS/TexCAPS presented data on fatal CHD events. No significant risks reduction were observed in fatal CHD events; 85/8823 (0.9%); RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.59-1.04) nor non-fatal CHD events 94/4927 (1.9%) non-fatal CHD events; RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.50-1.10). No heterogeneity was observed. .

Fatal and non-fatal CVD events (Analysis 2.5, Analysis 2.6 and Analysis 2.7)

Six trials with 12,286 participants reported on combined fatal and non-fatal CVD events. Two of the larger trials with 11,343 participants were able to demonstrate a significant reduction in this combined outcome and this was maintained in the pooled analysis using fixed effects model: 845 (6.8%) events; RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.66-0.85). There was no significant heterogeneity.

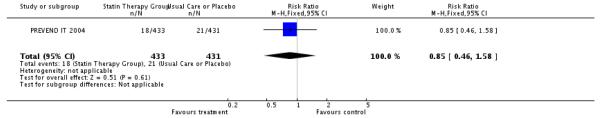

Two trials reported on fatal and one on non-fatal CHD events. Reductions in risk were observed in these endpoints; fatal CVD events;131/7,459 (1.7%); RR 0.70 (95% CI 0.50-0.99); nonfatal CVD events - 39/864 (4.5%); RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.46-1.58).

Fatal and non-fatal stroke events (Analysis 2.8, Analysis 2.9 and Analysis 2.10)

Seven trials with 21,556 participants reported on combined fatal and non-fatal stroke events. Only one trial was stopped prematurely was able to demonstrate a significant reduction in this combined outcome with the use of statins. The significant reduction was maintained in the pooled analysis using a fixed effects model: 450 (2.1%) events; RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.65-0.94) Only one trial with 6,595 participants reported on fatal stroke events and another one with 255 participants on non-fatal stroke events. No significant risk reduction was seen for these endpoints; fatal stroke events - 10/6595 (0.2%); RR 1.50 (95% CI 0.42-5.30) and non-fatal stroke events, 1/255 (0.4); RR 2.98 (95%CI 0.12-72.39).

Combined fatal and non-fatal CHD, CVD and stroke events (Analysis 2.11)

Only three trials with 17,452 participants reported a composite of fatal and non-fatal events for CHD, CVD and stroke. All three of the trials showed a significant reduction in this composite outcome with the treatment of statins which was maintained in the pooled analysis and using a fixed model: 938 (5.4%) events; RR 0.70 (95% CI 0.61-0.79)

Revascularisation (Analysis 1.4)

Five trials with 18,173 participants reported on the need for revascularisation procedures during follow-up: 313 (1.7%) underwent either PTCA or CABG. Two of the larger trials were able to demonstrate fewer revascularisation events in the intervention groups compared with the control groups with the use of statins and this was maintained in the pooled analysis using a fixed effects model were the a significant RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.53-0.83) was observed.

Cholesterol (Analysis 3.1 and Analysis 3.2)

Nine trials with 11 arms provided data on total and 11 with 13 trial arms on LDL cholesterol. Observations are based on 15,357and 22,413 participants respectively. For both endpoints all trials were able to demonstrate significant reductions; total cholesterol a net difference −0.89 mmol/L (95% CI −1.20 to −0.57 mmol/L) and LDL cholesterol a net difference of −0.92 (95% CI −1.10 to −0.74 mmol/L). There was marked heterogeneity of effects in both analysis (I2= 99%). It is likely that the heterogeneity is due to differences in the statin and dosage used- for example the dose of pravastatin ranged from10mg to 40mg in different trials. It is also possible that cholesterol outcomes were subject to reporting biases in some trials which might exaggerate the findings.

Adverse events figures (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10; Analysis 1.11; Analysis 1.12; Analysis 1.13; Analysis 1.14; Analysis 1.15; Analysis 1.16; Analysis 1.17 and Analysis 1.18)

Seven trials (eight trial arms) provided data on the following adverse events: myalgia (muscle pain), rhabdomyolysis, cancer, lymphoma and melanoma. We also looked for data on changes in muscle and liver enzyme, aspartate and alanine aminotransferase. In total 3,385/19,555 (17.3%) participants experienced an adverse event. Pooling the events rates indicated no difference between the intervention and control groups with the use of statin using a fixed effects model: RR 0.99 (95% 0.94-1.05) (Analysis 1.1). No difference was also observed with the number of participants stopping statin treatment due to adverse events, however there was significant heterogeneity observed and a random effect model had to be applied (Analysis 1.2).

Cancer: 793/17,277 (4.5%) participants in six trials developed cancer (Analysis 1.5). No statistical differences were observed between the overall rates for cancer in the intervention and control groups nor in the subgroup analysis for individual cancers: prostrate, colon, lung, bladder, breast, gastro-intestinal, genitor-urinary tract, respiratory tract. No significant heterogeneity was observed in any of these comparisons. It is important to note that the subgroups analysis are confined to only two trials (AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1998 and WOSCOPS 1997) which provided these data.

The event rates for other adverse effects including lymphoma, melanoma, myalgia, or rhabdomyolysis was low and ranged from 0.03% (rhabdomyolysis) to 7.4% (myalgia). No differences between groups were observed. No significant heterogeneity was observed in any of these comparisons of the five trials which reported on these events.

None of the trials reported on changes in muscle enzymes, aspartate nor alanine aminotransferase. Two large trials reported that 4.4% (31/7031) of participants experienced changes in liver enzymes but the differences between the intervention and control groups were of no statistical significance. There was no significant heterogeneity.

Costs

One trial reported on costs. WOSCOPS which recruited men with hypercholesterolaemia found that the use of statin yielded substantial health benefits at a cost which was not prohibitive: an undiscounted gain of 2,460 years of life at a cost of £8,121 per life year gained.

Patient quality of life

There were no reliable data on patient quality of life. Cell A+B provided limited data suggesting that the intervention of lifestyle advise plus pravastatin reduced stress and sleeping problems.

Subgroups analysis

We intended do undertake subgroups analysis for gender, age, and extent of hyperlipidaemia. However, none reported these breakdowns. No statistical differences in outcomes were observed in age and sex.

Sensitivity analysis

We were unable to locate any unpublished studies. We, therefore, confined our sensitivity analysis to study quality and to study size. Study quality; since most of the trials used double blinding techniques and intention to treat analysis and were free from selection bias, we focused our attention on methods of randomisation. We were unable to determine the method of randomisation for four trials: Japanese MEGA, AFCAPS/TexCAPS; Aspen and HYRIM. Sensitivity analysis indicated no change in the overall results due method of randomisation used (Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4; Analysis 5.5; Analysis 5.6; Analysis 5.7).

Study size: we confined our analysis to comparing large (>1000 participants) with small (<1000 participants) trials. Similarly, sensitivity analysis did not alter the overall results (Analysis 5.8; Analysis 5.9; Analysis 5.10; Analysis 5.11; Analysis 5.12; Analysis 5.13; Analysis 5.14).

DISCUSSION

The trials included in this systematic review showed reductions in all-cause mortality, composite endpoints and revascularisations. These findings were associated with falls in blood cholesterol and LDL cholesterol in all trials reporting these outcomes but no excess of combined adverse events, cancers or specific biochemical markers were found. Trials tended not to report single end points of CHD or stroke events reflecting the small numbers of events and that they were powered for composite endpoints. There was limited evidence to suggest that the use of statins for primary prevention may be cost effective and improve patient perceived quality of life. Sensitivity analysis suggested that age of participants or size of trial did not alter the overall results.

Unlike previous reviews, we attempted to examine the effects of statins in patients without evidence of existing cardiovascular diseases and we attempted to examine specific outcomes rather than composite outcomes. Although the trials intended to recruit only people without evidence of CVD some trials did enter some with participants with CVD . Rather than exclude such trials we set an arbitrary threshold of 10% to avoid any major influence of effects of treatment on those with existing CVD. Whilst our results concur with some of the published data, our findings differ from others. Specifically we concur with the results on all cause mortality and adverse events in previous systematic reviews (Brugts 2009; Ebrahim 1999; Mills 2008; NICE 2006). However, most of the previous systematic reviews included trials where more than 10% had a previous history of CVD. In two recently published reviews the baseline all-cause mortality event rates were 1.4 per 100 person years at risk (Mills 2008) and 1.7 per 100 person years (Brugts 2009) compared with 1.0 per 100 person years in this review. These findings suggest that these recent reviews have tended to select trials including sicker people than those included in our review which aimed to target only trials of primary prevention. Consequently, it is not surprising that findings for specific outcomes - rather than composite outcomes - differ between reviews. For example our review and one previous review (Thavendiranathan2006) did not find strong evidence of any reduction in CHD mortality whereas in a review where up to 50% of participants had suffered prior CVD, a 54% reduction in CHD mortality was reported (Mills 2008) - reflecting the strong evidence that statins are beneficial in secondary prevention. A major individual patient data meta-analysis - the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration - of 14 trials including over 90,000 participants reported sub-group findings in people without prior evidence of myocardial infarction or other coronary heart disease and found large reductions in major vascular endpoints (treated rate 8.5% vs. control rate10.6%; RR 0.78, 99% CIs 0.72 to 0.84) and major coronary events ( treated rate 4.5% vs. control rate 6.1%; RR 0.72, 99% CIs 0.66, 0.80) that were near identical to findings in people with prior CVD (Baigent 2005). These findings have been criticized on the grounds that the CTT collaborators did not disaggregate the primary and secondary prevention findings but report on a group with “no MI or other CHD” at baseline which includes a substantial number of people with pre-existing stroke, peripheral vascular disease and diabetes which would have inflated the finding for absolute risk reduction (Abramson 2007). Recently, the CTT collaboration have published new analyses focusing on the comparison between high and low doses of statins, including some relevant data on the effects of statins in primary prevention (CTT Collaboration 2011). They report strong evidence of a reduction in major vascular events in people without previous cardiovascular disease on statins (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.69, 0.82 per 1mmol/reduction in LDL cholesterol) and a 0.4% lower risk difference per year in those taking statins. Our estimate of the relative risk of major vascular events is of similar magnitude and precision. Strong evidence of the absence of any adverse effects on cancer risk is also confirmed by the CTT Collaboration report.

It is important to remain cautious in interpreting our results for combined end-points. In the majority of trials, power calculations were based on composite outcomes and not on single outcomes. Despite efforts to minimize bias in terms of blinding and use of intention to treat analysis, over one third of trials reported outcomes selectively. Eight trials did not report on adverse events at all. Moreover, the majority of trials focused their attention on different combinations of outcomes to ascertain a composite outcome. It was not always possible to ascertain or decipher these i.e. whether an individual who had a non-fatal clinical event followed by a fatal clinical event was counted as a clinical event under both categories. As a result, much useful data for this systematic review was lost. For example, the Japanese MEGA trials (whose study populations account of 24% of the total) provided data on combined fatal and non-fatal CHD events but not on fatal CHD events and non-fatal CHD events separately.

Furthermore, two of the larger trials were prematurely stopped because significant reductions in primary composite outcomes had been observed. This was also the case with the recently published JUPITER trial of rosuvastatin in people with raised C-reactive protein (JUPITER 2008) where the benefits of the reductions seen in a composite outcome of major cardiovascular events and specific endpoints at two years into the trial were considered sufficient to stop the trial. Nearly half the participants in the JUPITER trial suffered with metabolic syndrome and the baseline all-cause mortality rate in the control group was 1.25 per 100 patient years, 25% higher than in our systematic review. Early stopping of trials is of particular concern because in this and other situations early stopping may lead to an over-estimation of treatment effects particularly when the number of events is small. (Bassler 2007; Hlatky 2008; Montori 2005)

Caution also needs to be taken regarding the fact that all but one of the trials had some form of pharmaceutical industry sponsorship. It is now established that published pharmaceutical industry-sponsored trials are more likely than non-industry-sponsored trials to report results and conclusions that favour drug over placebo due to biased reporting and/or interpretation of trial results (Als-Nielsen 2003). In primary prevention where world-wide the numbers of patients eligible for treatment are massive, there might be motivations to use composite outcomes and early stopping to get results that clearly support intervention.

Overall the populations sampled within this review were white, male and middle aged. Therefore, caution needs to be taken regarding generalisability to older people who may be at greater risk of side effects and to women who are at lower risk of CVD events. Potential hazards of statins have been highlighted is small studies and some, such as increased risk of cancers, can be discounted by the evidence from the trials. However, even the more recent trials have not assessed potentially important side effects (e.g. possible cognitive impairments suggested by a small trial: Muldoon 2000) or have played down real increases in risk of diabetes with intensive cholesterol lowering (JUPITER 2008).

Two major trials were excluded from this review because of our criterion of only including trials with fewer than 10% of participants having a prior CVD diagnosis. ALLHAT-LLT (ALLHAT-LLT 2002) randomised 14% participants with a history of CHD (other CVD diagnoses were not reported) and ASCOT-LLA (ASCOT-LLA 2003) randomised 18% participants with a history of stroke or TIA, peripheral vascular disease or other cardiovascular diseases. As these trials were predominantly of primary prevention, their findings are of some relevance to the question of primary prevention despite not fulfilling our criteria. ALLHAT-LLT did not find any strong evidence of a reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.11) or in CHD deaths (RR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.84 to 1.16) in those randomised to pravastatin compared to usual care. ASCOT-LLA, which randomised participants to atorvastatin or placebo, also found no strong evidence of a reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.06) or in CVD mortality (RR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.66 to 1.23) despite achieving much greater cholesterol lowering effects than observed in ALLHAT-LLA. Combining evidence from these two trials with the estimates made in this review, the effects for all-cause mortality attenuate to RR 0.91; 95% CI: 0.84 to 0.99 and for CVD mortality to RR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.81 to 1.05.

In an update to a previous review claiming that statins gave no overall benefit in primary prevention (Therapeutics Letter 2003), the effects on all-cause mortality in trials of statins for primary prevention were RR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.86 to 1.00 and this attenuated to RR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.90 to 1.08 when four trials with serious risks of bias were excluded in a sensitivity analysis (Therapeutics Letter 2010). On the basis of these findings and a recent meta-analysis that managed to obtain data solely on patients without prior CVD diagnoses from four large trials (ALLHAT-LLT 2002; ASCOT-LLA 2003; PROSPER 2002; WOSCOPS 1997) and reported a total mortality of RR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.86 to 1.00) (Ray 2010), it was concluded that any apparent mortality or net health benefit of statins for primary prevention is more likely from trials where various biases may have arisen rather than a real effect (Therapeutics Letter 2010).

On the basis of our systematic review and these recent meta-analyses, it is clear that any decision to use statins for primary prevention should be made cautiously and in the light of an assessment of the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk profile. Widespread use of statins in people at low risk of cardiovascular events - below a 1% annual all-cause mortality risk or an annual CVD event rate of below 2% observed in the control groups in the trials considered here - is not supported by the existing evidence. Furthermore, the tendency of trial protocols to remove patients suffering with comorbidities limits their generalisability to typical patient populations in whom decisions to prescribe statins have to made.

Our review is not able to comment on cost-effectiveness as, surprisingly, few of the trials have published cost-effectiveness data to support their contentions that these drugs are worth using for primary prevention. Cost effectiveness analysis are price sensitive and need to be reviewed in the light of changes in cost and changes in prescribing (Ward 2007). Due to the assumed benefits of statin therapy in secondary prevention trials, and the recent systematic reviews (Baigent 2005; Brugts 2009; Mills 2008) concluding that statin prescribing may improve survival and be of benefit in the prevention CVD in people without cardiovascular disease, the need for cost effectiveness analyses may be viewed as unnecessary. However, commentary on the JUPITER trial makes it clear that decisions to treat ever more people with statins depends on a careful appraisal of the balance of benefits to safety and costs (Hlatky 2008). As noted by commentators, JUPITER demonstrated that treating 120 people for 1.9 years with rosuvastatin (at a cost of about US$287,000) would prevent one cardiovascular event (http://blogs.nature.com/mfenner/2008/11/23/what-are-the-right-numbers-for-jupiter; accessed 10 October 2010).

National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence UK (NICE) has provided some estimates based on data to 2005 and conclude that an annual risk of a CHD event ranging from 3% to 0.5%, the ranges of cost per quality adjusted life year gained (QALY) gained were £10,000 to £31,000 at age 45 years, £13,000 to £40,000 at age 55 years using older generic statins (NICE 2006). Their guidance is to use statins “… as part of the management strategy for the primary prevention of CVD for adults who have a 20% or greater 10-year risk of developing CVD.” Evidence supporting the use of statins as part of an overall strategy of identification of people at high risk of CVD events and lowering blood pressure and blood cholesterol has been produced for low and middle income countries (Lim 2007) and is now part of World Health Organisation policy for CVD prevention (WHO 2008b).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

This current systematic review highlights the shortcomings in the published trials of statins for primary prevention. Selective reporting and inclusion of people with cardiovascular disease in many of the trials included in previous reviews of their role in primary prevention make the evidence impossible to disentangle without individual patient data. In people at high risk of cardiovascular events due to their risk factor profile (i.e. 20+% 10-year risk), it is likely that the benefits of statins are greater than potential short term harms although long-term effects (over decades) remain unknown. Caution should be taken in prescribing statins for primary prevention among people at low cardiovascular risk.

Implications for research

As newer statins are developed it is likely that further trials will be conducted in lower risk populations to extend the evidence base particularly among younger people with adverse risk factor profiles which are associated with higher life time CVD risk (Berry 2009). It is important that these trials examine potential adverse effects of statins and report on them in an unbiased way. Use of composite outcomes is reasonable given the small number of events arising among low risk populations but disaggregation of events by cause is helpful for better understanding of the effects of statins and for future systematic reviews of trials. More attention should be given to studying possible cognitive impairment associated with use of statins. Individual patient data meta-analyses have provided an initial appraisal of the evidence available to 2011. Further updates focusing on effects of statins among people without pre-existing disease, examining a wider range of potential adverse effects and for a range of predicted CVD risk would help clarify the role of statins in primary prevention.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is ranked as the number one cause of mortality and is a major cause of morbidity world wide. Reducing high blood cholesterol which is a risk factor for CVD events is an important goal of medical treatment. Statins are the first-choice agents. Since the early statin trials were reported, several reviews of the effects of statins have been published highlighting their benefits particularly in people with a past history of CVD. However for people without a past history of CVD (primary prevention), the evidence is less clear. The aim of this systematic review is to assess the effects, both in terms of benefits and harms of statins for the primary prevention of CVD. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and EMBASE until 2007. We found 14 randomised control trials with 16 trial arms (34,272 patients) dating from 1994 to 2006. All were randomised control trials comparing statins with usual care or placebo. Duration of treatment was minimum one year and with follow up of a minimum of six months. All cause mortality. coronary heart disease and stroke events were reduced with the use of statins as was the need for revascularisations. Statin treatment reduced blood cholesterol. Taking statins did not increase the risk of adverse effects such as cancer. and few trials reported on costs or quality of life. This current systematic review highlights the shortcomings in the published trials and we recommend that caution should be taken in prescribing statins for primary prevention among people at low cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, UK.

External sources

Department of Health Funding for the Cochrane Heart Group, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised trial 4×4 factorial | |

| Participants | 919 participants based in the USA aged 40 - 79 (mean age of 62); 52% male | |

| Interventions | 20mg lovastatin + 1mg warfarin versus placebo followed up for 34 months | |

| Outcomes | Carotid atherosclerosis, cholesterol, fatal + non-fatal CHD events, stroke | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Blocked randomisation stratified by centre |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Carers and patients were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 8009 participants with hypercholesterolaemia based in Japan aged 40-70 (mean age 59); 32% male | |

| Interventions | 10-20mg pravastatin versus placebo; all participants got advice on diet; follow-up 5 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite of major CVD events, sudden cardiac death, angina and revascularisation. Single outcomes included: all cause mortality, total CVD events, fatal and nonfatal MI, stroke and TIA events, sudden cardiac death, angina and revascularisation, cholesterol, adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | open label for patients since placebo-controlled trials in Japan are regarded with suspicion |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | other than adverse events in detail |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 6606 participants in Texas, USA; mean age 58; 57.5% male; 89% Caucasian | |

| Interventions | 20-40 mg lovastatin compared with placebo; follow-up for 5.2 years; all participants received advice on diet | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite of fatal and nonfatal MI and fatal CHD events. Single outcomes included: all cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal CVD + stroke events, heart failure and adverse events | |

| Notes | Trial was stopped prematurely. To be terminated when 320 participants had experienced primary outcome event. Stopped when 267 had done so | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double blind-participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | other than results for cholesterol |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 2,410 participants with type 2 diabetes based in 16 developed countries with mean age 60; 62.5% male; 84% Caucasian | |

| Interventions | 10mg atorvastatin versus placebo; follow-up of 2.4 years (for primary prevention participants) | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite of fatal MI, stroke, sudden cardiac death, heart failure, CVD death. Single outcomes included: non-fatal or silent MI + stroke, revascularisation, resuscitated cardiac arrest, TIA, unstable angina, peripheral arterial disease, Ischaemic heart failure and adverse events | |

| Notes | Primary prevention participants recruited 2-3 years into the study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | other than not providing results on adverse events for primary prevention group |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 305 participants with hypercholesterolaemia based in Italy with mean age 55; 53% male | |

| Interventions | 40mg pravastatin versus placebo; follow-up of three years | |

| Outcomes | Slope of carotid artery, fatal and nonfatal MI, angina, revascularisations, cholesterol and adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Independent co-ordinating centre controlled allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Independent co-ordinating centre controlled allocation |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised control trial | |

| Participants | 2838 participants with diabetes based in UK and Ireland aged 40-75 years (mean 61.7); 68% male; 94.5% Caucasian | |

| Interventions | 10mg atorvastatin, all patients were given counselling on cessation of smoking; follow up of 3.9-4 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite of fatal and nonfatal MI, acute CHD death, resuscitated cardiac arrest. Single outcomes included: all cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal or silent MI + stroke, revascularisation, resuscitated cardiac arrest, total CVD events, adverse events and cholesterol | |

| Notes | Trial stopped prematurely due to large beneficial treatment effect | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | computer generated randomisation code |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Staff and patients unaware of computer generated randomisation code |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | triple-blind: participants, personnel and outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial; 2×3 factorial design | |

| Participants | 228 participants with hyperlipidaemia based in Sweden with a mean age of 49; 85% male | |

| Interventions | 10-40mg pravastatin plus intensive dietary advice versus placebo; follow-up for 18 months | |

| Outcomes | Fatal MI, cholesterol, quality of life. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation performed separately for each centre with numbers allocated to intervention and control groups |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | adverse events rates not provided for each group |

| Methods | Randomised trial; 2×3 factorial design | |

| Participants | 227 participants with hyperlipidaemia based in Sweden with a mean age of 49; 85% male | |

| Interventions | 10-40mg pravastatin plus dietary advice versus placebo; follow-up for 18 months | |

| Outcomes | Fatal MI, cholesterol, quality of life. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation performed separately for each centre with numbers allocated to intervention and control groups |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | CVD and adverse events rates not provided for each group |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 47 participants with hypercholesterolaemia based in Italy with a mean age of 51; 46% male | |

| Interventions | 80mg fluvastatin versus placebo; all participants were given advice on diet and exercise; follow-up for one year | |

| Outcomes | Adverse events, cholesterol. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Envelopes containing randomisation codes prepared by statistician |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation code could only be identified by statistician and person responsible for statistical analysis |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | single blind: participants |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial 2×2 factorial design | |

| Participants | 287 men with hypertension based in Norway aged 40-75 years (mean age 57) | |

| Interventions | 40mg fluvastatin; follow up four years | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite of fatal and nonfatal MI, + stroke, angina, sudden CHD death, TIA and heart failure. MACE: composite of cardiac death, fatal and nonfatal MI and revascularisation. Single outcomes included: adverse events, cholesterol | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | mostly but not for adverse events and cholesterol level at baseline and at 4 year follow-up not provided |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 447 men based in Finland aged 44-65 years (mean 57) | |

| Interventions | 40mg pravastatin versus placebo; follow-up of 3 years | |

| Outcomes | Carotid atherosclerotic progression, total mortality, fatal and non-fatal MI events, stroke, adverse events, cholesterol, other cardiac death, revascularisations, non cardiac death and heart failure | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Biostatistician prepared randomisation scheme- |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Tablets were masked by pharmaceutical company |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 17% patients dropped out and were excluded from the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | randomised trial (2×2 factorial design) | |

| Participants | 3982 patients with no prior CHD with diabetes mellitus as a subset of 20,536 UK adults aged 40-80 years | |

| Interventions | 40mg simvastatin compared with placebo, follow up 5.3 years for all participants | |

| Outcomes | Composite of coronary and vascular events, stroke, revascularisations | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central telephone system used |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double blind: participants and outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | only CVD event results provided for this subgroup |

| Methods | Randomised trial 4×4 factorial | |

| Participants | 253 men and women aged 45-70 (mean age 58) with hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis based in Italy | |

| Interventions | 25 mg hydrochlorothiazide + 40 mg pravastatin followed up for 2.6 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: carotid atherosclerosis. Secondary outcomes: non-fatal MI, CVD death, stroke, cholesterol and cancer | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was computer generate in blocks of 4 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial 4×4 factorial | |

| Participants | 255 men and women aged 45-70 (mean age 58) with hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis based in Italy | |

| Interventions | 20 mg fosinopril + 40 mg pravastatin followed up for 2.6 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: carotid atherosclerosis. Secondary outcomes: non-fatal MI, CVD death, stroke, cholesterol and cancer | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was computer generate in blocks of four. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial 2×2 factorial design | |

| Participants | 864 participants with microalbuminuria based in Holland aged 28-75 years (mean age 51); 64.5% male; 96% Caucasian | |

| Interventions | 40mg pravastatin versus placebo; follow-up 3.8 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: composite of fatal and non-fatal CVD events. Single outcomes included fatal CVD events, stroke, heart failure, nonfatal MI and cholesterol | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was computer generated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Subjects randomised were allocated to a treatment number. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Intention to treat analysis confined to CVD events, 6% dropped out |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Methods | Randomised trial | |

| Participants | 6595 men with hypercholesterolaemia based in Scotland aged 45-64 (mean age 55) | |

| Interventions | 40mg pravastatin versus placebo; follow-up 4.9 years | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: composite of non-fatal MI and CHD death. Single outcomes included total mortality, fatal CVD events, cholesterol, revascularisations, non-fatal MI and CHD death and adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | All trial personnel remained unaware of the subject’s treatment assignment throughout the study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | double-blind: participants and personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Intention to treat analysis used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| ALLHAT-LLT 2002 | 15% patients had history of CVD |

| Anderson 1993 | No Placebo - Statin + antioxidant versus Statin + antioxidant |

| ASCOT-LLA 2003 | 18% patients had history of CVD |

| Bak 1998 | Treatment length was only 6 months |

| BCAPS 2001 | 11% had history of CVD |

| Boccuzzi 1991 | Not an RCT - all participants were given Simvastatin |

| Branchi | Control Group was not randomised |

| Cassader 1993 | Treatment length was only 24 weeks |

| Chan 1996 | Treatment length is only nine months |

| CLIP 2002 | Not an RCT - All participants were given Pravastatin |

| CRISP 1994 | Treatment length is only 48 weeks |

| CURVES 1998 | No Placebo - Statin Versus Statin |

| Dangas 1999 | Treatment length is only six months |

| Davidson 1997 | No Placebo - Statin Versus Statin |

| Duffy 2001 | Treatment length is only six months |

| Egashira 1994 | Not an RCT - All participants were given Pravastatin |

| Eriksson 1998 | No control group - Pravastatin vs. Cholestyramine |

| EXCEL 1990 | Treatment length was only 48 weeks |

| FAST 2002 | Over 40% had CVD and over 14% had CHD |

| Ferrari 1993 | Treatment length is only 26 weeks |

| Gentile 2000 | Treatment length was only 24 weeks |

| Glasser 1996 | Length of treatment is only 12 weeks |

| Hokuriku NK-104 Study | Not an RCT - All participants were given intravasating |

| Hufnagel 2000 | Treatment length is only four months |

| Italian Family Physician | Not an RCT - open labelled |

| Jardine 2006 | Outcomes provided were aggregated. Unable to ascertain actual numbers for cardiac death and myocardial infarction |

| Jones 1991 | Length of treatment is only eight weeks |

| KLIS 2000 | Not randomised |

| Lemaitre 2002 | Cohort study |

| McGrae McDremott 2003 | Subjects were not randomised to statins or no statins |

| Mohler 2003 | Patients recruited had peripheral arterial disease |

| Muldoon 1997 | Treatment length is only six months |

| Nephrotic Syndrome Study | Treatment length was only nine months |

| Ohta 2000 | Treatment length is only six months |

| Oi 1997 | No placebo or control group |

| Ormiston 2003 | Not an RCT - all participants were given statins |

| Pitt 1999 | No Placebo - Statins versus Angioplasty |

| POSCH 1990 | Statins were not used |

| Pravastatin Multi 1993 | Treatment length was only 26 weeks |

| PROSPER 2002 | More than 10% of the participants had CVD |

| Sprecher 1994 | Treatment length is only 24 weeks |

| Stein 1997 | Treatment length is only four weeks |

| Su 2000 | Treatment length is only six months |

| Tanaka 2001 | Treatment length is only 12 weeks |

| Thomas 1993 | Treatment length is only 24 weeks |

| Thrombosis Prevention | Statins were not used |

| Wallace 2003 | Treatment length was only 8 weeks |

| Yu-An 1998 | Treatment length was less than one year |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised trial |

| Participants | 17,802 participants >50 years without history of CVD |

| Interventions | Rosuvastatin 20 mg daily |

| Outcomes | All cause mortality, fatal and non fatal CVD events, revascularisation |

| Notes | Stopped prematurely |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Adverse Events

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of study participants that had Adverse Events | 8 | 19555 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.94, 1.05] |

| 2 Number of Study Participants that Stopped Treatment Due to Adverse Events | 5 | 17328 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.85, 1.10] |

| 3 Number of Study Participants that were admitted to Hospital | 1 | 1905 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.74, 1.45] |

| 4 Number of Study Participants underwent revascularisation | 5 | 18173 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.53, 0.83] |

| 5 Number of Study Participants who developed cancer | 7 | 17277 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.85, 1.12] |

| 6 Number of Study Participants who develop Myalgia or muscle pain | 4 | 16464 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.81, 1.14] |

| 7 Number of Study Participants who develop Rhabdomyolysis | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.03, 3.20] |

| 8 Number of Study Participants who had elevated Liver Enzymes | 2 | 7031 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.77, 3.25] |

| 9 Number of Study Participants that developed Prostate Cancer | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.78, 1.31] |

| 10 Number of Study Participants who developed Melanoma | 2 | 13200 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.39, 1.48] |

| 11 Number of Study Participants who developed Colon Cancer | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.70, 2.24] |

| 12 Number of Study Participants who developed Lung Cancer | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.69, 2.43] |

| 13 Number of Study Participants who develop Lymphoma | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.48, 2.47] |

| 14 Number of Study Participants who develop Bladder Cancer | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.48, 2.47] |

| 15 Number of Study Participants who develop Breast Cancer | 1 | 6605 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.44 [0.62, 3.37] |

| 16 Number who developed Gastro-intestinal Cancers | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.73, 2.05] |

| 17 Number of Study Participants who developed Genito-urinary tract Cancers | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.57, 1.63] |

| 18 Number who developed Respiratory Tract Cancers | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.67, 2.08] |

Comparison 2.

Mortality and Morbidity

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total Mortality | 8 | 28161 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.73, 0.96] |

| 2 Number of Fatal CHD Events | 7 | 17619 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.59, 1.04] |

| 3 Number of Non-fatal CHD Events | 7 | 4927 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.50, 1.10] |

| 4 Total Number of CHD Events | 10 | 27969 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.65, 0.79] |

| 5 Number of Fatal CVD Events | 2 | 7459 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.50, 0.99] |

| 6 Number of Non-fatal CVD Events | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 7 Total Number of CVD Events | 6 | 12286 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.66, 0.85] |

| 8 Number of Fatal Stroke Events | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.42, 5.30] |

| 9 Number of Non-fatal Stroke Events | 1 | 255 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.98 [0.12, 72.39] |

| 10 Total Number of Stroke Events | 7 | 21556 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.65, 0.94] |

| 11 Total Number of Fatal and Non-fatal CHD, CVD and Stroke Events | 3 | 17452 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.61, 0.79] |

Comparison 3.

Lipids

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total Cholesterol | 11 | 15357 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.89 [−1.20, −0.57] |

| 2 LDL Cholesterol | 13 | 22413 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.92 [−1.10, −0.74] |

Comparison 4.

Treatment Compliance

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment Compliance | 4 | 14490 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.99, 1.14] |

Comparison 5.

Sensitivity Analysis

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Randomisation for Total Mortality | 7 | 27242 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.74, 0.97] |

| 1.1 Randomisation method known | 4 | 10723 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.65, 0.95] |

| 1.2 Randomisation method not known | 3 | 16519 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.75, 1.12] |

| 2 Randomisation for Fatal CHD Events | 6 | 16700 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.61, 1.08] |

| 2.1 Randomisation method known | 4 | 8190 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.50, 1.02] |

| 2.2 Randomisation method not known | 2 | 8510 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.64, 1.63] |

| 3 Randomisation for Non-fatal CHD Events | 4 | 3500 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.47, 1.14] |

| 3.1 Randomisation method known | 3 | 1595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.30, 1.12] |

| 3.2 Randomisation method not known | 1 | 1905 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.49, 1.63] |

| 4 Randomisation for Fatal CVD Events | 2 | 7459 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.50, 0.99] |

| 4.1 Randomisation method known | 2 | 7459 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.50, 0.99] |

| 5 Randomisation for Non-fatal CVD Events | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 5.1 Randomisation method known | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 6 Randomisation for Fatal Stroke Events | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.42, 5.30] |

| 6.1 Randomisation method known | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.42, 5.30] |

| 7 Randomisation for total number of fatal and non-fatal CHD, CVD and Stroke Events | 3 | 17359 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.61, 0.78] |

| 7.1 Randomisation method known | 1 | 2838 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.57, 0.86] |

| 7.2 Randomisation method not known | 2 | 14521 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.58, 0.80] |

| 8 Study Size for Total Mortality | 7 | 27242 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.74, 0.97] |

| 8.1 Over 1000 participants | 5 | 25952 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.73, 0.96] |

| 8.2 Under 1000 participants | 2 | 1290 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.51, 2.26] |

| 9 Study Size for Fatal CHD Events | 6 | 16700 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.61, 1.08] |

| 9.1 Over 1000 participants | 3 | 15105 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.62, 1.15] |

| 9.2 Under 1000 participants | 3 | 1595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.33, 1.37] |

| 10 Study Size for Non-fatal CHD Events | 4 | 3500 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.47, 1.14] |

| 10.1 Over 1000 participants | 1 | 1905 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.49, 1.63] |

| 10.2 Under 1000 participants | 3 | 1595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.30, 1.12] |

| 11 Study Size for Fatal CVD Events | 2 | 7459 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.50, 0.99] |

| 11.1 Over 1000 participants | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.48, 0.98] |

| 11.2 Under 1000 participants | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.25, 3.95] |

| 12 Study Size for Non-fatal CVD Events | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 12.1 Under 1000 participants | 1 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 13 Study Size for Fatal Stroke Events | 1 | 6595 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.42, 5.30] |