Abstract

The mechanical behavior of the annulus fibrosus (AF) of the intervertebral disc can be modeled as a mixture of fibers, extra-fibrillar matrix (EFM), ions, and fluid. However, the properties of the EFM have not been measured directly. We measured mechanical properties of the human EFM at several locations, determined the effect of age and degeneration, and evaluated whether changes in EFM properties correspond to AF compositional changes. EFM mechanical properties were measured using a method that combines osmotic loading and confined compression. AF samples were dissected from several locations, and mechanical properties were correlated with age, degeneration, and composition. EFM modulus was found to range between 10 and 50 kPa, increasing nonlinearly with compression magnitude and being highest in the AF outer-anterior region. EFM properties were not correlated with composition or degeneration. However, the EFM modulus, its relative contribution to tissue modulus, and model parameters were correlated with age. These measurements will result in more accurate predictions of deformations in the intervertebral disc. Additionally, parameters such as permeability and diffusivity used for biotransport analysis of glucose and other solutes depend on EFM deformation. Consequently, the accuracy of biotransport simulations will be greatly improved.

INTRODUCTION

The annulus fibrous (AF) is composed of collagen fiber bundles embedded in a matrix of proteoglycans and other proteins (1–6) to form a charged, porous, deformable solid material, which is embedded in a solution of water and ions (7). The mechanics of the AF can be modeled using mixture theory (8–12). Mixture models of the AF typically require a solid phase composed of fibers and extra-fibrillar matrix (EFM), ions, and fluid. The AF fiber network has oblique angles alternating within each consecutive lamella and is well modeled using exponential functions (8,10,13–17). The ions and fluid provide osmotic and viscoelastic effects. The fluid-flow contribution to viscoelasticity is well-described by the biphasic theory (10,12,18–20). The excess of ions in the interstitial fluid required to equilibrate the fixed charge of the proteoglycans create an imbalance in the chemical potential, which is balanced by the osmotic pressure; this phenomenon is described by the triphasic theory (8,10,11,19,21). In contrast to these relatively well-established components, the EFM, which represents all non-fibrillar solid components, has not been directly measured. Since aligned fibers do not contribute to the mechanical response in the direction perpendicular to the AF lamella, the EFM describes the AF mechanics in the radial direction (13–15,17). The EFM mechanical properties were estimated for use in finite element modeling studies, with assumed modulus values that spanned a large range from 4 kPa to 2.5 MPa (8–12). An accurate quantification of EFM mechanical behavior is essential since permeability and diffusion coefficients change as a function of EFM porosity (12,18–20). Experimental quantification of EFM mechanics will result in accurate models and predictions of biotransport and mechanobiology. Therefore, EFM stress-strain relationships must be measured.

Human AF mechanical properties change during aging and degeneration in response to changes in the AF tissue composition and structure (3,17,22–27). Age-related biochemical changes include decreased proteoglycan content and increased cross-linking (28–32). Proteoglycan loss includes loss of fixed charges and a corresponding reduction in osmotic pressure (21), which leads to a decrease in AF compression stiffness. In contrast, protein crosslinking, such as glycation, increases AF stiffness (33). During aging and degeneration, these changes occur simultaneously, with likely opposing effects on AF mechanical properties (14,15,17,23,27,34). Therefore, it is important to analyze the contribution of ionic (osmotic pressure) and non-ionic (crosslinking) effects independently. Moreover, AF composition is inhomogeneous. For example, the proteoglycan concentration increases and the collagen content decreases from the outer AF towards the inner AF (28,31,35). Consequently, EFM mechanical properties are likely to be location dependent due to the inhomogeneity in the AF composition.

We measured the mechanical properties of human EFM at several locations, determined the effect of age and degeneration on EFM mechanical behavior, and evaluated whether these changes correspond to AF compositional changes. A combined experimental and analytical method to determine mechanical properties of EFM in tension and compression was used (36).

METHODS

Sample Preparation

Cadaveric human lumbar spines were obtained from an approved tissue source (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA). Seven L3–L4 intervertebral discs from donors with an age range between 50 and 76 yrs old and with a Pfirrmann degenerative grade between 2 and 4 were used. MRI was performed to evaluate degeneration using T1ρ relaxation time (37). For confined compression tests, cylindrical specimens of 5 mm diam and 2 mm thickness were prepared from 3 AF locations along the mid-sagittal plane: inner-anterior (IAF), outer-anterior (OAF), and posterior (PAF) (Fig. 1). Confined compression samples were first equilibrated for 3 hrs in a sterile 0.15 M NaCl solution with protease inhibitors. This equilibration process induces tensile deformations (free-swelling) in all directions (36). The samples were then microtomed in a freezing-stage microtome to a thickness of 1.5 mm and a 4 mm diam plug was excised using a biopsy punch. The axis of the plug was perpendicular to the lamellae (radial direction) to minimize fiber contribution during the compression test. Uniaxial tension samples (n = 7/region) were also prepared from tissue adjacent to the confined compression samples. The sample lengths (10 mm) were aligned along a fiber direction and had a constant cross-section area of 2 × 1.5 mm2.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing harvest sites for AF samples. OAF: outer anterior. IAF: inner anterior. PAF: posterior. NP: nucleus pulposus. (Samples were dissected as full cylinders)

Mechanical Testing

Confined compression was applied in the radial direction (perpendicular to the lamellae) in multiple steps to measure the EFM mechanics from tension to compression. Samples were placed in a custom chamber with a porous filter at the bottom and compressed using an impermeable platen. Both the filter and the platen were made of stainless steel. The sample thickness was measured using the testing device (Instron 5542, Canton, MA) after applying a 1 kPa preload to equilibrium. 5 compression ramps of 10% were then applied at 0.005%/sec, followed by a 2 to 6 hr relaxation period. Since stress relaxation is slower with increased applied compression, the relaxation time after each ramp was adjusted from 2 hrs for the 1st compression ramp to 6 hrs for the 5th ramp to ensure that equilibrium was reached (36). Tension samples were place in the testing apparatus and a preload of 0.1 N was applied. 5 preconditioning cycles of 5% strain were applied 0.04%/s followed by a ramp to failure at the same strain rate (36,38).

Biochemical Analysis

After mechanical testing, the tested samples were lyophilized and digested overnight in Papain, and GAG content was measured using a 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay with chondroitin-6-sulfate as the standard (39–41). Collagen content was measured as hydroxyproline (OHP) using the Papain-digested aliquots subjected to following acid hydrolysis, assuming a mass ratio of collagen to OHP of 7.25 (42–44). Pyridinium concentration of the hydrolysates were measured using a MicroVue ELISA kit (Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA).

Constitutive modeling and Parameter calculation

To analyze the confined compression data, the annulus fibrosus was modeled as a combination of fibers, EFM, and osmotic pressure. The models have been widely used for the analysis of fiber-reinforced soft tissues (45–50). Since swelling stretched the tissue in all directions, the contribution of fibers was included in the calculation of the swelling stretch in the lamellar plane (i.e., the plane in which the fibers were contained). The expression for the osmotic pressure assuming ideal solutions is presented in Eq. (1), and constitutive equations of the EFM and fibers in terms of the strain energy functions are presented in Eqs (2) and (3):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, cfc is the fixed charge density, cb is the ion concentration in the testing bath, ci (i = 1…5) are material properties, I1‥I6 are strain invariants, and β = c2 + 2c3. The Holmes-Mow model used for the EFM is defined by 3 parameters: c1, c2 and c3, where c1 represents the stiffness of the tissue in the reference configuration, and c2 and c3 control the non-linearity (51). Similarly, the fiber model has 2 parameters: c4 and c5, where c4 is related to the stiffness of the fibers in the reference configuration (no deformations), and c5 controls the non-linearity of the fibers (52). To simplify the analysis, c4 and c5 were calculated from the uniaxial tests neglecting effects of the initial swelling.

The osmotic pressure and the external applied forces result in deformation of the EFM, which in turn alters the fixed charge density (cfc). That change can be quantified by:

| (4) |

where cfc0 and are the fixed charge density and the water content, respectively, at the reference configuration; J is the ratio between the volume at the deformed and reference configuration. The fixed charge density in the reference configuration was calculated from the GAG content as (50):

| (5) |

where cGAG is mg of GAG/ml of water, and MCS and ZCS are the molecular weight and number of charges per CS disaccharide, respectively (ZCS = 2 charges/repeating unit; MCS=513 g/repeating unit).

The parameters for the fiber model were calculated by curve-fitting the stress-strain curve from the uniaxial tension tests, along the fiber direction, applied to separate site-matched samples. The model parameters of the EFM were calculated by minimizing an objective (error) function obtained from the equilibrium between osmotic pressure, applied stresses, and the radial component of the EFM stresses (36):

| (6) |

where σ is the Cauchy stress, and the sub-index n represents the nth applied compression ramp. n = 0 corresponds to the free swelling case (no applied loads). The stress of the fibers was not considered for Eq. (6) since the model assumes that the fibers are contained in the lamellar plane and do not contribute to the tissue stress in the radial direction. To evaluate the error function, for a given set EFM parameters, the swelling stretches in the 3 physiological directions of the AF (radial, axial, and circumferential) are calculated from the equilibrium condition between the osmotic pressure, EFM, and fiber stresses at the free swelling state:

| (7) |

Then, the EFM stress in the radial direction and the osmotic pressure were calculated for each compression ramp. The applied stress was calculated as the ratio between applied force and sample area. The material parameters of the EFM were iteratively optimized until the objective function was minimized. Different values of the initial “guess” parameters c1 − c3 were used for each sample to verify that the method converged to same set of values for c1 − c3.

Mechanical properties of the EFM

Several mechanical parameters were used to quantify the mechanics of the EFM. The aggregate modulus was calculated as the slope of stress-stretch curve for the EFM. In a similar way, the aggregate modulus of the AF was calculated as the slope of the applied compression stress and the stretch curve. The difference between the EFM and AF aggregate modulus is that the latter includes the contribution of osmotic pressure. Thus, the EFM contribution is defined as the ratio between the aggregate modulus of the EFM and AF.

Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the dependence of swelling stretches on location (OAF: outer-anterior, IAF: inner-anterior, and PAF: posterior) and direction (circumferential, axial, and radial). Since location did not affect the swelling stretches, data from the 3 locations were pooled, and one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) with Dunn’s post-test was applied to determine differences among directions. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine the effect of applied stretch and location on mechanical parameters (aggregate modulus of AF and EFM, and the EFM contribution). One-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post-test was used to determine differences of biochemical parameters with location. Finally, samples from all locations were pooled (n = 21) to determine the dependence of mechanical parameters of the EFM with biochemical parameters, age, and degeneration quantified using the MR parameter T1ρ (37,53). Significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

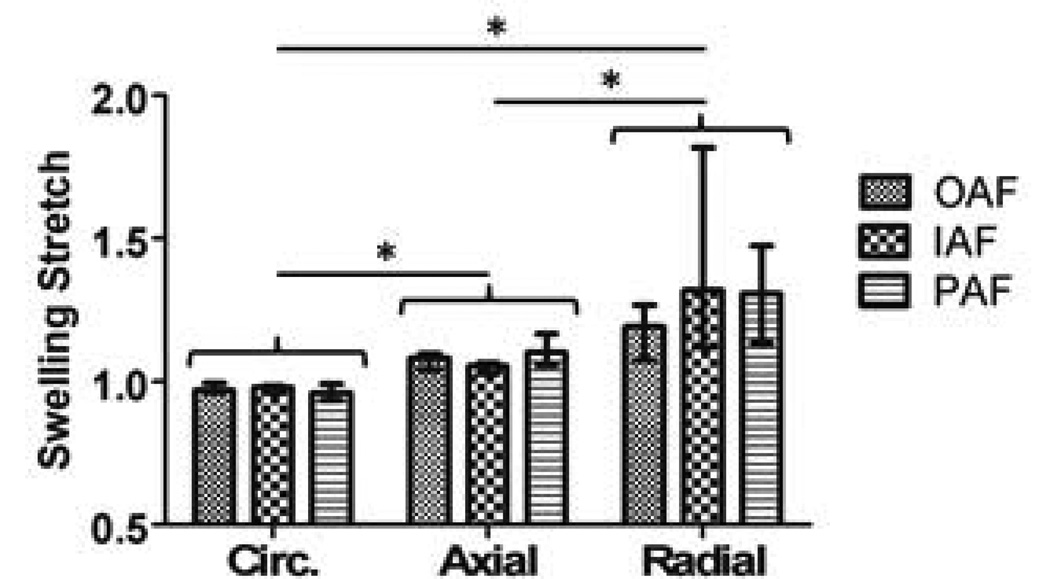

The swelling stretch was significantly different with direction, where radial (λ3) was highest followed by axial (λ2), and circumferential (λ1) (Fig. 2). Within each direction, there was no effect of location (Fig. 2). The EFM model parameters (c1, c2, and c3) were not different with location (Table 1). The fiber material parameters (c4 and c5) from the uniaxial tension data were also not different with location (Table 1). Since the model parameters did not change with location, the values for the 3 regions were pooled to evaluate effects of degeneration and age.

Figure 2.

Circumferential (Circ.), axial, and radial free-swelling stretch at different locations in the AF. Free swelling stretch was higher in the radial direction, followed by axial and circumferential directions. Within each, no effect of location in the disc was found. OAF: outer anterior. IAF: inner anterior. PAF: posterior. (* p < 0.05)

Table 1.

EFM model parameters (c1, c2, c3) and fiber parameters (c4, c5) from curve fitting of confined compression and uniaxial tension data. The fixed charge density (cfc0) is calculated from the GAG and water content in the stress-free (reference) configuration. Parameters do not change with region: OAF (outer anterior), IAF (inner anterior), and PAF (posterior) annulus fibrosus (c1 p = 0.20; c2 p = 0.14;c3 p = 0.83;c4 p = 0.94;c5 p = 0.82; cfc0 p = 0.79).

| OAF | IAF | PAF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| c1 (kPA) | 23.10 (27.65) | 7.02 (5.23) | 9.38 (8.83) |

| c2 | 0.40 (0.43) | 0.10 (0.07) | 0.24 (0.15) |

| c3 | 0.19 (0.17) | 0.18 (0.12) | 0.14 (0.12) |

| c4 (MPa) | 0.46 (0.29) | 0.52 (0.30) | 0.48 (0.34) |

| c5 | 7.44 (7.5) | 8.78 (12.30) | 5.64 (6.05) |

| cfc0 (M) | 0.043 (0.019) | 0.052 (0.015) | 0.049 (0.024) |

Tissue and EFM moduli and the relative contribution of the EFM to tissue modulus were calculated as a function of EFM stretch (Fig. 3A). Tissue modulus was lowest in tension and increased with compression (Fig. 3A). Tissue modulus was not different between AF locations (OAF, IAF, and PAF). EFM modulus was lowest and constant in the tension, and increased with applied compression (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the tissue modulus, the EFM modulus varied significantly with disc location, with OAF having a higher modulus than both the IAF and PAF at the maximum applied compression (p<0.05). The EFM contribution (ratio of EFM modulus to tissue modulus) was higher in tension than in compression for all locations, with OAF having the highest contribution (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

The aggregate modulus of the AF and EFM, and EFM contribution (A, B, and C, respectively) for different locations in the disc as function of applied EFM stretch. The EFM contribution is defined as the ratio between EFM and AF moduli. EFM stretch lower than 1.0 represents compression, and higher than 1.0 represents tension. EFM modulus of the OAF region was higher than the other two regions when EFM stretch was lower than 0.7. The EFM contribution was higher for the OAF region in tension (OAF: outer anterior, IAF: inner anterior, PAF: posterior) (* p < 0.05).

Collagen, crosslink, and GAG content were not different with location (Table 2). EFM modulus was not correlated with any composition parameter, suggesting that no significant dependence of the EFM elastic properties exists on GAG content or collagen content. The EFM modulus in compression and tension, and EFM contribution in compression increased with age at the OAF region (Fig. 4). The EFM material parameters c1 and c2 also increased with age, while there was a trend for c3 to decrease with age (Fig. 5). From the average model parameters, only c3 was correlated with degeneration as measured by T1ρ relaxation time (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Collagen, crosslink (pyridinium, PYD) and GAG content, expressed as percentage of dry weight (mean and standard deviation) from OAF (outer anterior), IAF (inner anterior), and PAF (posterior) annulus fibrosus. There was no different with location for any of the parameters (collagen: p = 0.20; GAG: p = 0.06; Crosslink: p = 0.38).

| OAF | IAF | PAF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen (OHP) | 62.67 (18.31) | 47.04 (17.84) | 52.20 (14.75) |

| Crosslink (PYD) | 0.046 (0.026) | 0.029 (0.013) | 0.033 (0.015) |

| Glycosaminoglycan | 4.59 (1.49) | 7.41 (2.49) | 5.81 (2.66) |

Figure 4.

EFM aggregate modulus in compression (A) and tension (B), and EFM contribution in compression (C) for the OAF region as a function of age (A: r2 = 0.611, p < 0.05; B: r2 = 0.745, p < 0.05; C: r2 = 0.823, p < 0.05). Changes were not significant for other AF regions.

Figure 5.

Location-averaged values of the Holmes-Mow model parameters for the EFM as function of age. c1 and c2 increased with age (A and B) while there was a trend for a decrease in c3 (C). c1 represents the stiffness of the tissue in the reference configuration, while c2 and c3 control the non-linearity of the tissue.

Figure 6.

Location-averaged values of the Holmes-Mow model parameters for the EFM as function of degeneration measured using T1ρ relaxation time. No correlation was found between parameters c1 and c2 and degeneration (A and B). However, c3 was correlated with degeneration (r = 0.785, p < 0.05) (C).

DISCUSSION

The EFM mechanical properties of AF have not previously been measured directly, and a large range of values for these properties were assumed in prior modeling studies (8–11,19,20). In this study, the elastic properties of EFM were directly measured using an experimental method designed to minimize the contribution of the fibers and osmotic pressure. For small deformations, the EFM modulus ranged between 10 and 50 kPa and contributed between 40 and 75% of the tissue modulus. These results are at the lower end of the range of mechanical properties assumed in previous modeling studies (4 kPa – 2.5 MPa) (8–11,19,20). A direct comparison of the EFM properties with the values reported in those previous studies is not pertinent since those model parameters were arbitrarily chosen, or the values were adjusted to match results from whole disc tests. However, other studies measured the mechanical behavior of the AF (EFM combined with osmotic pressure) in the radial direction in tension and compression (14,15,18,21,54). The tensile modulus of the AF measured in this study (~50 kPa) was lower than those measured using uniaxial tension (0.14 – 0.24 MPa) (15,54). A possible explanation for the difference is that the larger strains applied in uniaxial tension (>50%) may induce fiber realignment towards the loading direction. Compression studies also reported higher AF modulus (18,21,34). These differences could be attributed to differences in the loading protocol such as higher preloads. The EFM modulus increased with compression, and its relative contribution to tissue modulus decreased with compression (Fig. 3). The decrease of the contribution of the EFM with compression suggests that the osmotic pressure and its associated stiffness increase more than the EFM stiffness. The increase of the osmotic pressure is due to increased fixed charge density with compression.

No significant correlation was found between EFM properties and degeneration. However, the EFM modulus and model parameters were significantly correlated with age. The strong age-degeneration correlation is well known. However, the effect of degeneration on the measured EFM properties may be smaller than our capacity to detect these correlations with the current experimental variance and sample size. Additionally, degeneration was quantified using the magnetic relaxation time, T1ρ, which is typically measured in the nucleus pulposus and is used to represent the degenerative condition of the whole disc (37,53,55). Consequently, T1ρ may not be directly related to changes in the AF.

The aggregate modulus of the EFM did not correlate with the measured composition parameters of GAG, pyridinium, and collagen content. The lack of correlation with GAG content implies that GAG has a negligible non-ionic contribution to the EFM. In contrast, a similar study in articular cartilage showed a decrease of compression stiffness when a sample was tested at 2M NaCl solution and after GAG digestion, demonstrating a non-ionic contribution of the GAGs to cartilage mechanics (56). The difference in the non-ionic contribution between articular cartilage and AF may be due to the fact that the GAG content is 20% of the dry weight in cartilage, while it is only 7% in the inner AF. The lack of correlation between EFM modulus and both pyridinium cross-link and collagen contents suggests that the transverse stiffness of collagen fibers may not contribute to the modulus. This observation is important since a considerable compressive deformation is applied perpendicular to the fibers, and the measured EFM modulus could have been influenced by the transverse stiffness of collagen fibers or their crosslinks. AF fibers and crosslinks contribute to mechanical behavior in other loading configurations (such as tension in the fiber direction); however, they may not contribute in the transverse loading direction used in this study. Elastin is a protein that may contribute to the tensile stiffness of the EFM. The elastin content of human AF is ~2% of the dry weight (57). Elastin fibers are located at the interface between adjacent lamellae, and their density increases toward the AF outer region (1,6,57). This could explain the higher tensile modulus of the EFM at the OAF region.

The EFM modulus and its contribution to the tissue modulus increased with age at the OAF region (Fig. 4). The increase of EFM stiffness with age may be caused by accumulation of non-enzymatic crosslinking (glycation) of proteins in the EFM; however, these were not measured in this study. Crosslinking causes a significant increase in the stiffness of disc tissues (33). There was no difference among model parameters (c1, c2 and c3) with location (Table 1), indicating that only a single set of parameters is needed to model the EFM of human AF. The model parameters c1 and c2 were correlated with age, which is related to the increase in EFM modulus.

There are some limitations in this study. The osmotic pressure was calculated assuming an ideal Donnan law. If proteoglycan content in the AF does not accurately follow this law, the osmotic pressure may be inaccurate. However, the difference in the osmotic pressure would be transferred to the EFM. This means that the mechanics of the AF can be reproduced, in the range of deformation considered in this study, if the same combination of models for the EFM and osmotic pressure are used. Another limitation is that the parameters of the fibers were calculated prior to calculation of the free swelling stretch. This may affect slightly the reference configuration used to analyze the uniaxial data. However, this should have a negligible influence in the calculation of the swelling stretch in the radial direction used in the calculation of EFM properties. Finally, the small sample size used to analyze correlations with degeneration imposes a limitation in the magnitude of the degeneration effect we could detect.

In summary, we experimentally measured the mechanical properties of the human EFM. The aggregate modulus was location and age dependent, while no correlation was observed with GAG, collagen, or crosslink content. The lack of correlation between GAG and EFM modulus shows negligible non-ionic contribution of GAG. In a similar way, the lack of correlation with collagen and crosslinks suggests that the measured modulus represents the stiffness of the EFM, and the contribution of the fibers is negligible. These measurements will result in a more accurate prediction of deformation in numerical models of the intervertebral discs. Additionally, important parameters such as permeability and diffusivity used for the analysis of transport of glucose and other solutes depended on the deformation of the EFM. Consequently, the accuracy of the simulation of these biotransport processes will be greatly improved. These properties can also be used as a reference for the design of artificial and tissue-engineered disc replacements, and to isolate functional components when studying disc pathology or treatment.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded by NIH (R01AR050052). We are grateful to Syrena Huynh for her assistance with mechanical testing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghosh P, Bushell GR, Taylor TF, Akeson WH. Collagens, elastin and noncollagenous protein of the intervertebral disk. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1977:124–132. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inerot S, Axelsson I. Structure and composition of proteoglycans from human annulus fibrosus. Connect. Tissue Res. 1991;26:47–63. doi: 10.3109/03008209109152163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce RH, Grimmer BJ, Adams ME. Degeneration and the chemical composition of the human lumbar intervertebral disc. J. Orthop. Res. 1987;5:198–205. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson CH, Happey F, Naylor A, Turner RL, Palframan J, Shentall RD. Collagens and associated glycoproteins in the human intervertebral disc. Variations in sugar and amino acid composition in relation to location and age. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1972;31:45–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.31.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eyre DR. Biochemistry of the intervertebral disc. Int Rev Connect Tissue Res. 1979;8:227–291. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-363708-6.50012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Tirlapur U, Fairbank J, Handford P, Roberts S, Winlove CP, Cui Z, Urban J. Microfibrils, elastin fibres and collagen fibres in the human intervertebral disc and bovine tail disc. J. Anat. 2007;210:460–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban JP, Maroudas A. Swelling of the intervertebral disc in vitro. Connect. Tissue Res. 1981;9:1–10. doi: 10.3109/03008208109160234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun DDN, Leong KW. A nonlinear hyperelastic mixture theory model for anisotropy, transport, and swelling of annulus fibrosus. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:92–102. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000007794.87408.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder Y, Elliott DM, Wilson W, Baaijens FPT, Huyghe JM. Experimental and model determination of human intervertebral disc osmoviscoelasticity. J. Orthop. Res. 2008;26:1141–1146. doi: 10.1002/jor.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehlers W, Karajan N, Markert B. An extended biphasic model for charged hydrated tissues with application to the intervertebral disc. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2009;8:233–251. doi: 10.1007/s10237-008-0129-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao H, Gu WY. Three-dimensional inhomogeneous triphasic finite-element analysis of physical signals and solute transport in human intervertebral disc under axial compression. J Biomech. 2007;40:2071–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao H, Justiz M-A, Flagler D, Gu WY. Effects of swelling pressure and hydraulic permeability on dynamic compressive behavior of lumbar annulus fibrosus. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:1234–1241. doi: 10.1114/1.1523920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerin HL, Elliott DM. Quantifying the contributions of structure to annulus fibrosus mechanical function using a nonlinear, anisotropic, hyperelastic model. J. Orthop. Res. 2007;25:508–516. doi: 10.1002/jor.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell GD, Sen S, Elliott DM. Human annulus fibrosus material properties from biaxial testing and constitutive modeling are altered with degeneration. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2012;11:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10237-011-0328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell GD, Guerin HL, Elliott DM. Theoretical and uniaxial experimental evaluation of human annulus fibrosus degeneration. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:111007. doi: 10.1115/1.3212104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Z, Shi X, Peng X, Caner F. Fibre-matrix interaction in the human annulus fibrosus. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;5:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerin HAL, Elliott DM. Degeneration affects the fiber reorientation of human annulus fibrosus under tensile load. J Biomech. 2006;39:1410–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Périé D, Korda D, Iatridis JC. Confined compression experiments on bovine nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus: sensitivity of the experiment in the determination of compressive modulus and hydraulic permeability. J Biomech. 2005;38:2164–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu WY, Yao H, Vega AL, Flagler D. Diffusivity of ions in agarose gels and intervertebral disc: effect of porosity. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:1710–1717. doi: 10.1007/s10439-004-7823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson AR, Yuan T-Y, Huang C-YC, Travascio F, Yong Gu W. Effect of compression and anisotropy on the diffusion of glucose in annulus fibrosus. Spine. 2008;33:1–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perie D, MacLean J, Owen J, Iatridis J. Correlating material properties with tissue composition in enzymatically digested bovine annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus tissue. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006;34:769–777. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoniou J, Steffen T, Nelson F, Winterbottom N, Hollander AP, Poole RA, Aebi M, Alini M. The human lumbar intervertebral disc: evidence for changes in the biosynthesis and denaturation of the extracellular matrix with growth, maturation, ageing, and degeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:996–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI118884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acaroglu ER, Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Mow VC, Weidenbaum M. Degeneration and aging affect the tensile behavior of human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Spine. 1995;20:2690–2701. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pokharna HK, Phillips FM. Collagen crosslinks in human lumbar intervertebral disc aging. Spine. 1998;23:1645–1648. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199808010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roughley PJ. Biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration - Involvement of the extracellular matrix. SPINE. 2004;29:2691–2699. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146101.53784.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons G, Eisenstein SM, Sweet MB. Biochemical changes in intervertebral disc degeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;673:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue N, Espinoza Orías AA. Biomechanics of intervertebral disk degeneration. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2011;42:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.07.001. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole TC, Ghosh P, Taylor TK. Variations of the proteoglycans of the canine intervertebral disc with ageing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;880:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon DJ, Davison PF. Aging, and crosslinking in mammlian collagen. Exp Aging Res. 1977;3:87–105. doi: 10.1080/03610737708257091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krajícková J, Poláková R, Smetana K, Vytásek R. Age-dependent changes in proteoglycan biosynthesis in human intervertebral discs. Folia Biol. (Praha) 1995;41:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olczyk K. Age-related changes in proteoglycans of human intervertebral disc. Z Rheumatol. 1994;53:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh K, Masuda K, Thonar EJ-MA, An HS, Cs-Szabo G. Age-related changes in the extracellular matrix of nucleus pulposus and anulus fibrosus of human intervertebral disc. Spine. 2009;34:10–16. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818e5ddd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner DR, Reiser KM, Lotz JC. Glycation increases human annulus fibrosus stiffness in both experimental measurements and theoretical predictions. J Biomech. 2006;39:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Rawlins BA, Weidenbaum M, Mow VC. Degeneration affects the anisotropic and nonlinear behaviors of human anulus fibrosus in compression. J Biomech. 1998;31:535–544. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iatridis JC, MacLean JJ, O’Brien M, Stokes IAF. Measurements of proteoglycan and water content distribution in human lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine. 2007;32:1493–1497. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dd3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortes DH, Elliott DM. Extra-fibrillar matrix mechanics of annulus fibrosus in tension and compression. Biomech Model Mechanobiol [Internet] 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10237-011-0351-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johannessen W, Auerbach JD, Wheaton AJ, Kurji A, Borthakur A, Reddy R, Elliott DM. Assessment of human disc degeneration and proteoglycan content using T1rho-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:1253–1257. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217708.54880.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szczesny SE, Peloquin JM, Cortes DH, Kadlowec JA, Soslowsky LJ, Elliott DM. Biaxial tensile testing and constitutive modeling of human supraspinatus tendon. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134:021004. doi: 10.1115/1.4005852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han WM, Nerurkar NL, Smith LJ, Jacobs NT, Mauck RL, Elliott DM. Multi-scale Structural and Tensile Mechanical Response of Annulus Fibrosus to Osmotic Loading. Annals of Biomedical Engineering [Internet] 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nerurkar NL, Han W, Mauck RL, Elliott DM. Homologous structure-function relationships between native fibrocartilage and tissue engineered from MSC-seeded nanofibrous scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2011;32:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs NT, Smith LJ, Han WM, Morelli J, Yoder JH, Elliott DM. Effect of orientation and targeted extracellular matrix degradation on the shear mechanical properties of the annulus fibrosus. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:1611–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caligaris M, Canal CE, Ahmad CS, Gardner TR, Ateshian GA. Investigation of the frictional response of osteoarthritic human tibiofemoral joints and the potential beneficial tribological effect of healthy synovial fluid. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009;17:1327–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williamson AK, Chen AC, Sah RL. Compressive properties and function—composition relationships of developing bovine articular cartilage. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2001;19:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herbage D, Bouillet J, Bernengo JC. Biochemical and physiochemical characterization of pepsin-solubilized type-II collagen from bovine articular cartilage. Biochem. J. 1977;161:303–312. doi: 10.1042/bj1610303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC. A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:245–258. doi: 10.1115/1.2894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hou JS, Mow VC, Lai WM, Holmes MH. An analysis of the squeeze-film lubrication mechanism for articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1992;25:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90024-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.García JJ, Cortés DH. A nonlinear biphasic viscohyperelastic model for articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2006;39:2991–2998. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ateshian GA, Warden WH, Kim JJ, Grelsamer RP, Mow VC. Finite deformation biphasic material properties of bovine articular cartilage from confined compression experiments. J Biomech. 1997;30:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)85606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Azeloglu EU, Albro MB, Thimmappa VA, Ateshian GA, Costa KD. Heterogeneous transmural proteoglycan distribution provides a mechanism for regulating residual stresses in the aorta. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H1197–H1205. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chahine NO, Wang CC-B, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Anisotropic strain-dependent material properties of bovine articular cartilage in the transitional range from tension to compression. J Biomech. 2004;37:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes MH, Mow VC. The nonlinear characteristics of soft gels and hydrated connective tissues in ultrafiltration. J Biomech. 1990;23:1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holzapfel G, Gasser T, Ogden R. A new constitutive framework for arterial wall mechanics and a comparative study of material models RID B-3906-2008. J. Elast. 2000;61:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borthakur A, Maurer PM, Fenty M, Wang C, Berger R, Yoder J, Balderston RA, Elliott DM. T1ρ magnetic resonance imaging and discography pressure as novel biomarkers for disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine. 2011;36:2190–2196. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820287bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujita Y, Duncan NA, Lotz JC. Radial tensile properties of the lumbar annulus fibrosus are site and degeneration dependent. J. Orthop. Res. 1997;15:814–819. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zobel BB, Vadalà G, Del Vescovo R, Battisti S, Martina FM, Stellato L, Leoncini E, Borthakur A, Denaro V. T1ρ magnetic resonance imaging quantification of early lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration in healthy young adults. Spine. 2012;37:1224–1230. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31824b2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Canal Guterl C, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions of proteoglycans to the compressive equilibrium modulus of bovine articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2010;43:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith LJ, Fazzalari NL. The elastic fibre network of the human lumbar anulus fibrosus: architecture, mechanical function and potential role in the progression of intervertebral disc degeneration. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0918-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]