Abstract

Constitutive NF-κB activity has emerged as an important cell survival component of physiological and pathological processes, including B-cell development. In B cells, constitutive NF-κB activity includes p50/c-Rel and p52/RelB heterodimers, both of which are critical for proper B-cell development. We previously reported that WEHI-231 B cells maintain constitutive p50/c-Rel activity via selective degradation of IκBα that is mediated by a proteasome inhibitor-resistant, now termed PIR, pathway. Here, we examined the mechanisms of PIR degradation by comparing it to the canonical pathway that involves IκB kinase-dependent phosphorylation and β-TrCP-dependent ubiquitylation of the N-terminal signal response domain of IκBα. We found a distinct consensus sequence within this domain of IκBα for PIR degradation. Chimeric analyses of IκBα and IκBβ further revealed that the ankyrin repeats of IκBα, but not IκBβ, contained information necessary for PIR degradation, thereby explaining IκBα selectivity for the PIR pathway. Moreover, we found that PIR degradation of IκBα and constitutive p50/c-Rel activity in primary murine B cells were maintained in a manner different from B-cell-activating-factor-dependent p52/RelB regulation. Thus, our findings suggest that nonconventional PIR degradation of IκBα may play a physiological role in the development of B cells in vivo.

NF-κB is a family of transcription factors that regulate diverse cellular functions in response to a wide range of stimuli (19). NF-κB is typically found as a homo- or heterodimer of p50 (NFκB1), p52 (NFκB2), RelA (p65), RelB, or c-Rel. Regulation of NF-κB is mediated by a family of inhibitor molecules called IκB proteins, including IκBα, IκBβ, IκBɛ, IκBγ/p105, IκBδ/p100, and Bcl-3. Most IκB proteins associate with NF-κB dimers to cause their localization in the cytoplasm. Upon activation by a wide variety of structurally and functionally distinct signals, NF-κB dimers regulate the expression of a multitude of genes important for cell survival, inflammatory responses, and immune cell development (31). Thus, the NF-κB system serves as an important paradigm for understanding how distinct signals activate gene expression via activation of signal transduction pathways.

Inducible NF-κB activation through IκBα degradation has been studied extensively and is identified by several hallmark traits (reviewed in reference 19). Most cell types contain inactive NF-κB/IκBα complexes in their cytoplasm. Upon stimulation with a variety of inducers, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), IκBα is phosphorylated by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex on the N-terminal residues Ser32 and Ser36 (14, 38). Dually phosphorylated IκBα is directly recognized by the E3 ligase β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP) (60, 70, 71). Polyubiquitin chain formation on Lys21 and/or Lys22 of IκBα is then catalyzed by β-TrCP and leads to 26S proteasome-dependent degradation of IκBα and the release of free NF-κB heterodimers to direct transcription in the nucleus (7). This “canonical” degradation of IκBα does not require its ankyrin repeats or association with NF-κB because unrelated proteins (i.e., glutathione S-transferase [GST] and p53) could be efficiently targeted to this degradation pathway when the N and C termini of IκBα were fused to the corresponding termini of these unrelated proteins (4, 65, 68). This canonical pathway is believed to contribute to many NF-κB activation pathways (19, 31).

The specificity of β-TrCP-dependent ubiquitylation of IκBα involves the consensus β-TrCP recognition motif DpSGψXpS (where pS is phosphor-Ser, ψ is a hydrophobic amino acid, and X is any amino acid) (67). This motif is shared by a number of β-TrCP substrates, including the IκB family members, IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBɛ, and the tumor suppressor β-catenin. A recent study of the crystal structure of β-TrCP complexed to a β-catenin peptide revealed that phosphorylated Ser residues corresponding to Ser32 and Ser36 of IκBα and the Asp residue corresponding to Asp31 of IκBα are absolutely necessary for proper contacts. Additionally, at the corresponding Gly33 of IκBα, the binding pocket of β-TrCP appears to accommodate only Gly (67). Thus, preclusion of IκBα recognition by β-TrCP by mutagenesis of IκBα (60) or competition peptides (70) can efficiently inhibit canonical NF-κB activation pathways. Accordingly, pharmacological suppression of proteasome activity (42, 63) also prevents these pathways.

Recent studies have described, in addition to the canonical NF-κB activation pathway, the presence of several different alternative NF-κB activation mechanisms. For example, noncanonical IKKα-dependent processing of NF-κB2 (p100) to p52 generates active p52/RelB heterodimers by the human T-cell leukemia virus Tax protein and in developing murine B cells (53, 58, 69). Silica or pervanadate treatment of cells can also permit phosphorylation of IκBα on Tyr42, followed by dissociation from NF-κB, thereby leading to activation of NF-κB (26, 30). Additionally, calpain-dependent, but proteasome-independent, IκBα degradation has been reported during TNF signaling and calcium-regulated developmental processes (21, 45, 46). Moreover, the C terminus of IκBα contains casein kinase 2 (CK2) phosphorylation sites that regulate degradation of free IκBα via a proteasome degradation pathway (37, 51, 64). Thus, NF-κB activation mechanisms are not limited to the canonical pathway, and distinct mechanisms may play key roles in specific physiological and pathological processes.

While knowledge regarding inducible NF-κB activation pathways has been expanding extensively, as described above, less is known about the regulatory repertoires employed by constitutive NF-κB activation pathways. Although NF-κB activity was originally discovered in B cells as a constitutively nuclear factor that bound to the enhancer element of the κ light-chain gene, most of the details of this pathway remain elusive (52). Recent literature suggests that there are two major NF-κB heterodimers necessary for B-cell development and survival: p50/c-Rel and p52/RelB (9, 20, 35). It has recently been shown that B-cell-activating-factor (BAFF)-dependent signaling, via the BAFF receptor, leads to the processing of NF-κB2 via a “noncanonical” pathway to generate active p52/RelB heterodimers, a critical step in B-cell development (9). While it has been shown that p50/c-Rel complexes comprise the majority of the constitutively nuclear NF-κB DNA binding complexes in murine splenic B cells (20, 40), the biochemical mechanism underlying activation of these complexes is not well understood.

In addition to that associated with B-cell development, constitutive NF-κB activity is maintained by various cancer cell types, including Reed-Sternberg cells, diffuse large-B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, breast cancers, and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (2, 13, 16, 59). One prominent target gene for NF-κB in different cell types is the IκBα gene (8, 62). Therefore, it is puzzling that the augmented synthesis of IκBα found in cells with constitutive NF-κB activity fails to inactivate these constitutively nuclear heterodimers. One way for cells to maintain constitutive NF-κB activity is through continuous degradation of IκBα via genetic or epigenetic modifications of the canonical NF-κB activation pathway. Consistently, unrelenting IKK activity is found in several cancer cell types to maintain rapid IκBα turnover and constitutive NF-κB activity (13, 16, 18). In contrast, we have previously identified a pathway in the WEHI-231 murine B-lymphoma cell line and to some extent in normal murine splenic B cells that utilizes rapid and continuous degradation of IκBα in a proteasome-independent manner to maintain constitutive p50/c-Rel activity (17, 41, 56). Interestingly, even though the IKK phosphorylation sites and β-TrCP recognition motifs are conserved among major IκB family members, this pathway is selective for IκBα in these B cells. Moreover, calcium chelators and calmodulin inhibitors blocked this pathway without affecting LPS-inducible IκBα degradation. While it has been suggested that CK2-dependent phosphorylation of the C-terminal sequences can lead to calpain-mediated IκBα degradation in WEHI-231 B cells (54), other studies have shown that removal of the C terminus of IκBα does not affect this degradation (56a). Here we term this constitutive IκBα degradation PIR, for proteasome inhibitor-resistant IκBα degradation, to distinguish it from other known IκBα degradation pathways.

In this study, we examined the molecular requirements necessary for PIR degradation of IκBα through mutagenesis of the N-terminal IKK phosphorylation and ubiquitylation residues and β-TrCP interaction sites of IκBα in the WEHI-231 cell background. We now provide several lines of evidence that the canonical and PIR IκBα degradation pathways diverge downstream of IKK activity. Additionally, we find that the ankyrin repeats of IκBα, but not IκBβ, contain additional information necessary to selectively target IκBα for PIR degradation. Moreover, we find that PIR IκBα degradation and constitutive activation of p50/c-Rel heterodimers in normal murine B cells do not require the same BAFF-dependent signaling pathway, via the BAFF receptor, necessary for p100 processing to p52. Therefore, our findings support the notion that the maintenance of constitutive p50/c-Rel activity occurs in a manner distinct from that for the recently elucidated BAFF-dependent NF-κB activation pathway in developing B cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and chemicals.

WEHI-231 and W231.Bcl-XL cells and all derivatives of these cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratory, Inc.), 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 1,250 U of penicillin G (Sigma) and 0.5 mg of streptomycin sulfate (Sigma) per ml in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator (Forma). Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells and all derivatives were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics as described above in a humidified incubator containing 10% CO2. Tissue culture plates were coated with 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin for HEK 293 cells. W231.Bcl-XL cells were maintained in 300 μg of G418 (Mediatech)/ml. Puromycin-resistant cell lines were maintained in 2 μg of puromycin (Sigma)/ml. Hygromycin-resistant cell lines were maintained in 500 μg of hygromycin (Roche)/ml.

Mice.

Male and female A/J (wild-type BAFF receptor) and AW.Bcmd-2c (mutant BAFF receptor) mice were from a pathogen-free mouse colony in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin (10). The mice were maintained at 23°C with 40 to 60% humidity and 12-h light-dark cycles and were used at age 7 to 10 weeks for B-cell subset analysis. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol A00847-4-08-99).

Chemicals.

Cycloheximide, Bay 11-7082, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ATP, TPA, and LPS (L2880) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Benzyloxycarbonyl-aspartyl-glutamyl-valyl-aspartate (z-DEVD-fmk), benzyloxycarbonyl-tyrosyl-valanyl-alanyl-aspartate (z-YVAD-fmk), and benzyloxycarbonyl-valanyl-alanyl-aspartate (z-VAD-fmk) were purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. Benzyloxycarbonyl-leucyl-leucyl-leucinal (MG132) was purchased from Peptide Institute, Inc. Benzyloxycarbonyl-leucyl-norleucinal (calpeptin), clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone, and human recombinant TNF-α were purchased from Calbiochem.

Antibodies.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against IKKα (M-280), IκBα (C-21), IκBβ (C-20), actin (C-11), c-myc (9E10), HA (Y-11), p65 (C-20), p50 (NLS), RelB (C-19), p52 (I-18), and ICAD (FL-331) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. A polyclonal antibody generated against p52 (06-413) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. A monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody was purchased from Covance. A monoclonal antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody (3F10) directly conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. A monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody was purchased from Oncogene Research. Affinipure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-mouse IgM μ-chain-specific antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories. The 5432 antibody, generated against the N terminus of IκBα, was used as previously described (39). The c-Rel antibody (5071) was previously described (27). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

B-cell collection and flow staining analysis.

Splenocytes were dissociated by mechanical shearing, and red blood cells (RBC) were depleted by lysing them in an RBC lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.2 to 7.4]). When B-cell purification was performed, B cells were purified by negative selection with the magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS) B-cell purification kit (Miltenyi Biotech). For comparison of NF-κB regulation in transitional B cells between the wild-type and BAFF receptor mutant backgrounds, autoreconstitution studies were initiated by subjecting A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c mice to 500 rads of sublethal irradiation in order to deplete mature splenic B cells (5). Irradiated mice were then allowed to recover for 13 days, at which point the majority of splenic B cells represented the transitional B cells, as revealed by positive surface staining of C1qRp (previously termed 493 and AA4) (1) and analyzed on a FACScan or FACScalibur using CELLQuest software (data not shown).

Mutagenesis, infections, and transfections.

Substitution mutagenesis was performed by two-step PCR using murine IκBα cDNA, and all mutant IκBα cDNAs were directly sequenced by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center to verify integrity. cDNAs for murine K3R- and K5R-IκBα were kindly provided by Kei Tashiro (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). The cDNAs encoding various forms of IκBα were ligated into the pLHL-CA retroviral vector (64) or pLPL-CA retroviral vector. PLPL-CA was derived from pLHL-CA and the pRetro-On vector (Clontech). PLHL-CA was digested with EcoRI and XhoI to isolate the region containing the CA promoter and the multiple cloning sites. This fragment was ligated into the pRetro-On vector (Clontech) between the long terminal repeat regions and downstream of the puromycin resistance gene. The c-myc-ΔF-β-TrCP cDNA was kindly provided by Zhijian Chen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). This cDNA was ligated into the pLPL-CA vector for use in the coimmunoprecipitation assays.

Transfection of HEK293 cells was performed by calcium phosphate precipitation as described previously (24). For experiments involving transient transfection of HEK293 cells, cells were treated with the appropriate inducers 40 to 45 h after transfection. To generate stable HEK 293 cells, cells were transfected with vectors and selected with 2 μg of puromycin (Sigma)/ml 24 to 48 h after transfection until drug-resistant pools grew up. Infections of WEHI-231 and W231.Bcl-XL cells were performed as previously described (41).

Analysis of IκBα degradation.

To measure IκBα degradation, cells were counted and 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells were placed in 1-ml wells in an incubator containing 5% CO2 for 2 to 4 h to reduce low-level, proteasome-dependent NF-κB activation associated with medium change (our unpublished observations). Cells were then treated with the appropriate chemicals for various times. Cells were pelleted at 13,000 × g for 10 s in an Eppendorf centrifuge, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pelleted again at 13,000 × g for 10 s, and stored at −70°C. Pellets were thawed, resuspended in 20 μl of PBS and 20 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer, and boiled directly for 10 to 15 min. Samples were then electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-10 or 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, electroblotted (Bio-Rad) onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore), and then incubated with the appropriate antibodies as described previously (41). Western blots were analyzed by enhanced chemiluminescence as described by the manufacturer (Amersham).

To measure IκBα degradation in B cells from A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c mice, cells were counted and 0.5 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells were placed in 1-ml wells and treated similarly to WEHI-231 cells. Cells were then pelleted at 5,000 × g for 5 min in a refrigerated swinging-bucket centrifuge, washed once with PBS, pelleted again at 5,000 × g for 5 min as described above, and stored at −70°C. Pellets were thawed and subjected to Western blot analysis as described above.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

For β-TrCP/IκBα coimmunoprecipitation experiments using HEK293 cells, cell pellets were resuspended in small amounts of PBS (10% of the final lysis buffer volume), lysed in a lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 0.5% NP-40, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) containing protease inhibitors (0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of leupeptin/ml, 16 μg of aprotinin/ml) and phosphatase inhibitors 20 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride), and spun at 13,000 × g in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4°C. Equal protein amounts were separated for immunoprecipitation. Twenty percent of each immunoprecipitation volume was allocated separately, 2× Laemmli buffer was added, and the samples were boiled to examine input levels by Western blot analysis. The anti-c-myc antibody was added to the lysates for 1 h at 4°C, and then protein G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were added and the samples were rotated for an additional 3 to 4 h at 4°C for immunoprecipitation reactions. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times in excess immunoprecipitation buffer. Laemmli buffer (2×) was added to the beads and boiled, and the entire sample was analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (41).

To examine IκBα/NF-κB interactions in W231.Bcl-XL cells, cell pellets were lysed as described above, equal amounts of extracts were separated for each immunoprecipitation, and 20% of the input was set aside and analyzed as described above. The appropriate antibodies and protein G-Sepharose beads were added to immunoprecipitate the NF-κB/IκB complexes. Immunoprecipitates were rotated overnight at 4°C, washed three times with excess lysis buffer, boiled in 2× Laemmli buffer, and analyzed by Western blotting.

EMSA and in vitro kinase assays.

W231.Bcl-XL cells and primary B cells were counted, and 2 × 106 cells were placed in 1-ml wells and allowed to rest for 2 to 4 h in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells were then treated with the appropriate chemicals and spun down as described above. For electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with whole-cell extracts, cell pellets were lysed in Totex buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 350 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitors, spun down at 13,000 × g in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 10 min at 4°C, and subjected to an EMSA as described previously (40). For EMSA with nuclear extracts, cell pellets were first lysed in buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitors and spun at room temperature for 10 s in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 13,000 × g. The remaining nuclear pellet was lysed in buffer C (20 mM HEPES, 25% glycerol, 0.45 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitors for 30 min on ice and then spun at 13,000 × g for 10 min in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4°C and the supernatant was removed and used as the nuclear extract. The Igκ-κB oligonucleotide probe was as described previously (40). In vitro kinase assays were performed as described previously (23).

RESULTS

PIR IκBα degradation requires the IKK phosphorylation sites, but not the N-terminal ubiquitylation sites, of IκBα.

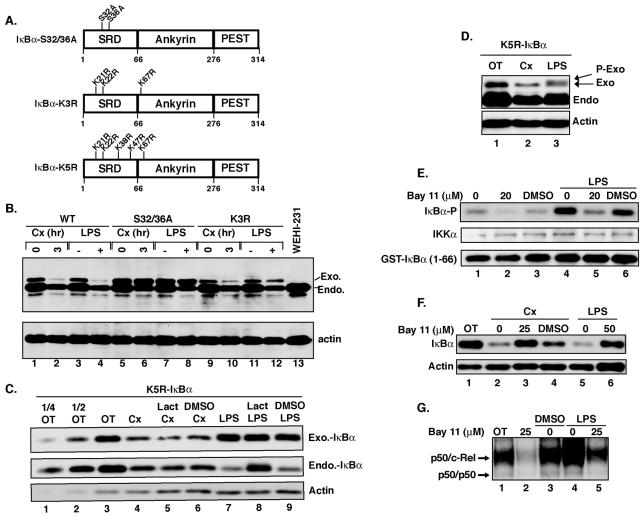

Although the PIR pathway and canonical NF-κB activation possess differential proteasome requirements for IκBα degradation, we wanted to determine whether both degradation pathways required the upstream IKK phosphorylation sites in IκBα. We have previously reported that a mutant IκBα with Ser-to-Ala substitutions (S32/36A-IκBα) at both the 32 and 36 positions underwent constitutive proteolysis in the WEHI-231 cells (41). We have found that this degradation was associated with an inadvertent apoptotic process introduced by the assay condition (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To eliminate this apoptosis-associated IκBα degradation, we generated the W231.Bcl-XL cell line, stably expressing the antiapoptotic Bcl-XL gene, and found that S32/36A-IκBα was resistant to PIR degradation, similar to what was found for the LPS-inducible pathway (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 to 8). Additionally, PIR IκBα degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells was also prevented by the inhibition of IKK activity (Fig. 1E to G). Degradation of similarly introduced wild-type IκBα and the endogenous version served as positive controls in these experiments. These results suggested that both IKK activity and the IKK phosphorylation sites were important for PIR IκBα degradation in these cells.

FIG. 1.

IKK phosphorylation sites, but not N-terminal ubiquitylation sites, are necessary for PIR IκBα degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells. (A) Diagram of serine and lysine mutant IκBαs examined. SRD, signal response domain region of IκBα containing the inducible IKK phosphorylation and β-TrCP ubiquitylation sites. (B) C-terminally HA-tagged wild-type (WT) IκBα and S32/36A- and K3R-IκBα mutant IκBαs were stably expressed in W231.Bcl-XL cells and left untreated or treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml for 3 h or 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. (C) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing C-terminally HA-tagged K5R-IκBα were treated with either 25 μg of cycloheximide/ml for 3 h in the absence or presence of clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (10 μM; Lact) or DMSO or with 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min in the absence of or after pretreatment with clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (10 μM) or DMSO. Whole-cell pellets were analyzed by Western blotting. One-fourth and one-half of the untreated samples (OT) were loaded to approximate the amount of degraded protein. (D) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing a C-terminally HA-tagged K5R-IκBα were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide/ml for 3 h or 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min. Whole-cell pellets were analyzed by Western blotting. P-Exo, slower-migrating phospho-K5R-IκBα band. (E) W231.Bcl-XL cells were treated with either 20 μM Bay 11-7082 or DMSO (0.1%) for 3 h. For the LPS-treated samples, W231.Bcl-XL cells were left untreated or pretreated with Bay 11-7082 or DMSO for 30 min followed by 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to immune complex kinase assays using an anti-IKKα antibody to immunoprecipitate the IKK complex. The immunoprecipitated IKK complex was subjected to a kinase assay using GST-IκBα(1-66) as a substrate. Phosphorylation of GST-IκBα (IκBα-P) was measured by autoradiography, while the levels of IKKα and GST-IκBα were measured by Western blot analysis. (F) W231.Bcl-XL cells were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide/ml in the absence or presence of Bay 11-7082 or DMSO (0.1%) for 3 h. For the LPS-treated samples, W231.Bcl-XL cells were left untreated or pretreated with Bay 11-7082 for 30 min, followed by 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min. Cell extracts were measured for IκBα levels by Western blot analysis. (G) W231.Bcl-XL cells were treated as in panel E, except that 25 μM Bay 11-7082 was used. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and equal protein amounts were subjected to EMSA.

Since constitutive IκBα degradation is mediated in a PIR manner in both WEHI-231 and W231.Bcl-XL cells, there must be a divergence point between the canonical and PIR degradation pathways upstream of the proteasome degradation step. Thus, we next investigated the requirement for N-terminal lysine residues in IκBα whose β-TrCP-dependent ubiquitylation leads to proteasome-dependent degradation in canonical pathways (19). Since we found a mutant IκBα with Arg substituted at both Lys21 and Lys22 to be efficiently degraded by the control canonical LPS pathway (24), we next utilized a mutant IκBα K3R-IκBα (Fig. 1A), containing Lys21, -22, and -67 mutated to Arg. Surprisingly, K3R-IκBα was still susceptible to both types of degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells (Fig. 1B, lanes 9 to 12), suggesting that alternative Lys residues compensated for the lack of these three lysines. Therefore, we used K5R-IκBα, containing Lys21, -22, -38, -47, and -67 mutated to Arg and stably expressed it in W231.Bcl-XL cells. K5R-IκBα was completely resistant to LPS-inducible degradation (Fig. 1C, lane 7). However, it was still sensitive to PIR degradation (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 and 5). Moreover, on a high-percentage gel that was run for a prolonged period to separate the IκBα phosphorylated isoforms, the stable K5R-IκBα underwent signal-dependent phosphorylation, as evidenced by the characteristic migration shift found in cells treated with LPS (Fig. 1D, lane 3). This demonstrated that the lack of LPS-dependent degradation was due to the lack of ubiquitylation, not IKK-dependent phosphorylation. In contrast, K5R-IκBα underwent PIR degradation without the appearance of a slower-migrating phosphorylated form (Fig. 1D, lane 2). Thus, the N-terminal Lys residues required for canonical degradation were not absolutely required for PIR degradation, suggesting that these degradation pathways diverge at the ubiquitylation step.

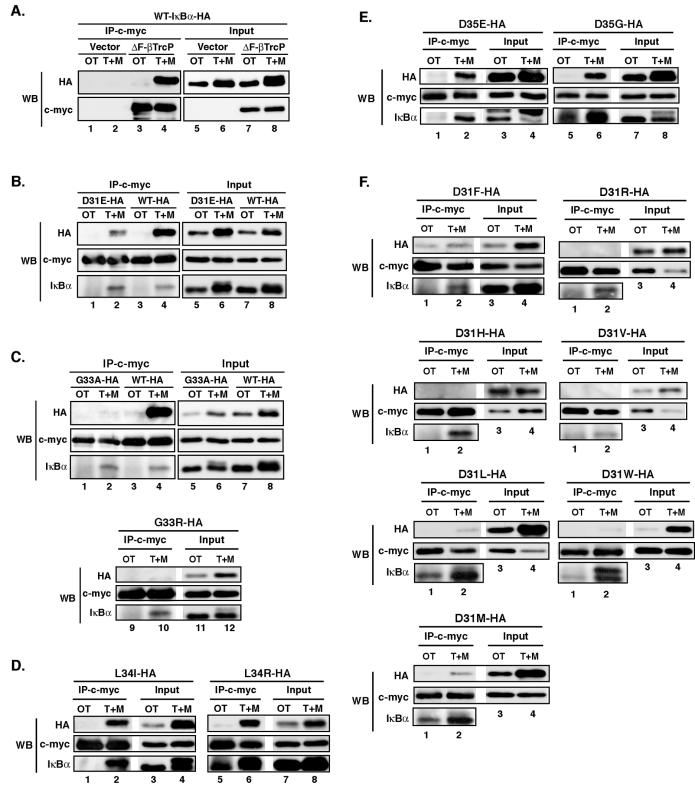

Mutations at Asp31 of IκBα further reveal differences between PIR and LPS-inducible IκBα degradation pathways in W231.Bcl-XL cells.

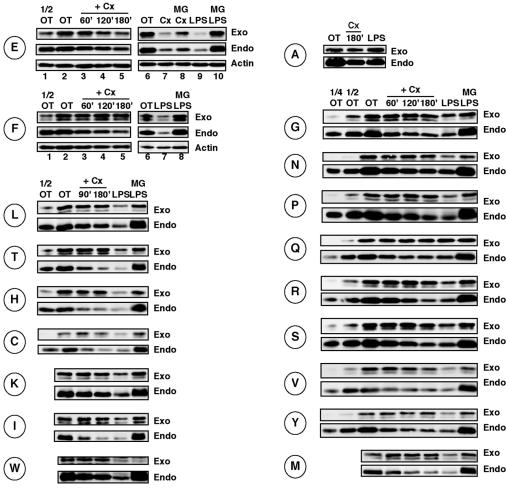

Because canonical and PIR forms of IκBα degradation appeared to diverge primarily at the level of ubiquitylation, we wanted to determine whether or not recognition by the E3 ligase β-TrCP was involved in the PIR degradation pathway. The recent crystal structure of β-TrCP (67) revealed that an Asp residue corresponding to Asp31 of IκBα is critical for recognition by β-TrCP. To examine the requirement for this site in PIR and LPS-inducible IκBα degradation, we generated the conservative mutant IκBα D31E-IκBα and stably expressed it in W231.Bcl-XL cells. This mutant IκBα was still susceptible to PIR (albeit less efficiently than wild-type IκBα) and LPS-inducible (at a level similar to that for wild-type IκBα) degradation (Fig. 2E), suggesting that either acidic amino acid could be tolerated at this position for both pathways. Subsequently, we mutated Asp31 to a drastically different amino acid, Phe. Surprisingly, we found that D31F-IκBα was completely resistant to PIR degradation but was still susceptible to LPS-inducible degradation in these cells (Fig. 2F). This result suggested that it might be possible to isolate other mutant IκBαs that reveal differences between PIR and LPS-inducible IκBα degradation pathways by amino acid replacement of the Asp31 residue. Therefore, we mutated residue 31 in IκBα to all of the remaining amino acids individually. We found that substitution of any other amino acid at this position rendered IκBα resistant to PIR degradation with the exception of partial degradation exhibited by D31V-IκBα (Fig. 2V). Very surprisingly, all of the mutant IκBαs except D31A- and D31Q-IκBα were still tolerated by the LPS-inducible and proteasome-dependent degradation pathways (Fig. 2). In all of these analyses, degradation of the endogenous IκBα protein served as a positive control for comparison.

FIG. 2.

Mutations at Asp31 reveal differences between PIR and LPS-inducible IκBα degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells. W231.Bcl-XL cells expressing the indicated D31 mutant IκBαs (each mutant IκBα is indicated with the amino acid abbreviation located to the left of each set of blots) were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml in the absence or presence of MG132 (10 μM; MG) for the indicated times. These cells were also treated with 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min in the absence of or after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132. Whole-cell pellets were examined for IκBα degradation by Western blot analysis. Actin was also examined as a loading control in all cases (some data not shown). OT, untreated sample.

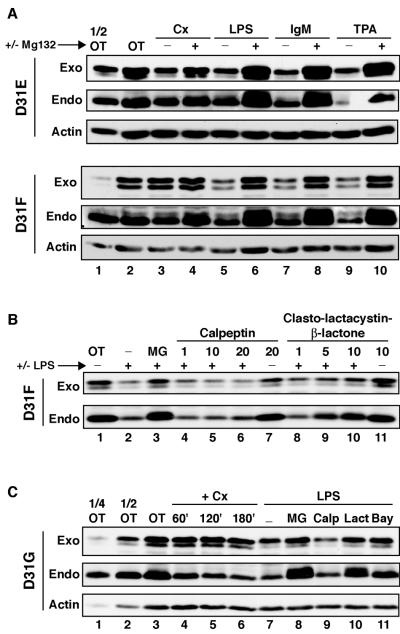

Because the Asp31 requirement for LPS-inducible degradation discussed above appeared to conflict with the requirement for Asp at this position in the recently described β-TrCP crystal structure (67), we next evaluated whether inducible degradation of these mutant IκBαs was potentially due to some unusual LPS-specific event in W231.Bcl-XL cells. In Fig. 3A, we observed that IgM cross-linking and treatment with TPA also led to inducible degradation of both D31E- and D31F-IκBα. Moreover, inhibition of degradation by treatment with the proteasome inhibitors MG132 and clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, but not with the calpain inhibitor calpeptin (Fig. 3B), indicated that degradation occurred through the proteasome pathway. Furthermore, inhibition of LPS-inducible D31G-IκBα degradation by Bay 11-7082 (Fig. 3C, lanes 7 and 11) suggested that this pathway was also IKK dependent. Therefore, IκBα could be inducibly degraded in a manner dependent on both IKK activity and the proteasome with a different sequence specificity of β-TrCP recognition in W231.Bcl-XL cells than what was suggested by the recently described crystal structure (67).

FIG. 3.

Inducible degradation of Asp31 mutant IκBαs occurs by multiple inducers and is inhibited by proteasome and IKK inhibitors in W231.Bcl-XL cells. (A) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing D31E- and D31F-IκBα were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml in the absence or presence of MG132 (10 μM) for 3 h. To measure inducible degradation, cells were treated with 20 μg of LPS/ml, 10 μg of Affinipure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-mouse IgM μ chain specific/ml, or 50 nM TPA for 30 min in the absence of MG132 or after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132. Whole-cell pellets were examined by Western blot analysis. OT, untreated sample. (B) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing D31F-IκBα were left untreated or treated with 20 μg of LPS/ml in the absence of MG132 or after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132 (MG), 1 to 20 μg of calpeptin/ml, or 1 to 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone. Whole-cell pellets were examined by Western blot analysis. (C) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing D31G-IκBα were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide/ml for 0 to 3 h. To measure inducible degradation, cells were treated with 20 μg of LPS/ml in the absence of MG132 or after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132, 20 μg of calpeptin (Calp)/ml, 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (Lact), or 25 μM Bay 11-7082 (Bay).

PIR and canonical IκBα degradation pathways diverge at the point of β-TrCP recognition.

Because PIR and LPS-inducible IκBα degradation possessed differential sensitivities to mutagenesis of the N-terminal Lys and Asp31 residues in W231.Bcl-XL cells, we next examined whether these two pathways also displayed differential requirements for other residues within the β-TrCP consensus sequence. We introduced a series of mutations in the β-TrCP recognition motif of IκBα (DpSGψXpS) that could be used to determine whether PIR and canonical IκBα degradation pathways diverge at the point of β-TrCP recognition (Fig. 4A). We chose conservative and nonconservative substitutions at each amino acid position and analyzed them as described above. We found a number of mutant IκBαs with mutations in this motif that could still undergo PIR degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells, including G33A-, L34I-, L34R- D35E-, and D35G-IκBα (Fig. 4B to D). Interestingly, G33R-IκBα could not support PIR degradation (Fig. 4B, bottom). Furthermore, the same mutant IκBαs that underwent PIR degradation were also susceptible to LPS-inducible degradation in the W231.Bcl-XL cells. In addition to the surprising data obtained from the Asp31 mutant IκBαs, degradation of the nonconservative mutant IκBα L34R-IκBα was still permitted by both pathways. We thus questioned whether our observations of LPS-inducible degradation in W231.Bcl-XL were representative of the canonical, β-TrCP-dependent IκBα degradation.

FIG. 4.

Some alterations in the β-TrCP recognition sequences of IκBα are still permitted by the PIR IκBα degradation pathway. (A) Diagram displaying the positions of mutations in the mutant IκBαs analyzed (amino acids 31 to 36 of IκBα and amino acids 18 to 23 of IκBβ). (B to D) C-terminally HA-tagged mutant IκBαs with the indicated β-TrCP recognition site mutations were stably expressed in W231.Bcl-XL cells. These cells were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml for 0 to 3 h in the absence or presence of MG132 (10 μM; MG) or with 20 μg of LPS/ml in the absence of MG132 or after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132. Whole-cell pellets were analyzed by Western blotting.

To confirm whether these β-TrCP recognition mutant IκBαs were indeed recognized by β-TrCP in a manner dependent on phosphorylation at Ser32 and Ser36 residues, we employed a coimmunoprecipitation method that allowed us to trap phosphorylated IκBα associated with β-TrCP (23). Since transient cotransfection of β-TrCP and IκBα resulted in phosphorylation-independent association (data not shown), we needed to generate HEK293 cell lines stably expressing the mutant IκBαs; then either c-myc-ΔF-β-TrCP or an empty vector was transiently transfected for coimmunoprecipitation studies. Cells were then either left untreated or treated with TNF-α in the presence of MG132. Under these conditions, β-TrCP failed to interact with wild-type IκBα in the absence of a signal but efficiently interacted after TNF-α/MG132 treatment (Fig. 5A). We next evaluated whether mutant IκBαs that exhibited differential degradation patterns under PIR and LPS-inducible degradation conditions in W231.Bcl-XL cells could also display differential recognition by β-TrCP. Interestingly, we found that association of D31E-IκBα with β-TrCP was markedly less than that of wild-type IκBα (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 2 and 4), a result that is consistent with the critical requirement of the Asp at position 31 predicted by the crystal structure (67). We next examined the association of β-TrCP with several Asp31 mutant IκBαs and the other β-TrCP consensus sequence mutant IκBαs described above. Consistent with the prediction from the crystal structure (67), none of the Asp31 substitutions that we tested were tolerated for inducible association with β-TrCP (Fig. 5F). Strikingly, G33A-IκBα completely failed to interact with β-TrCP (Fig. 5C, compare lanes 2 and 4), even though this substitution introduced a very modest change in the amino acid side chain. The crystal structure indicated that there is very little room in the β-TrCP recognition pocket for any substitution at this position (67). Accordingly, G33R-IκBα did not interact at all (Fig. 5C). In contrast, a replacement of Leu34 with Ile or a change of the hydrophobicity by replacement with Arg did not impair association with β-TrCP (Fig. 5D, lane 6). Both D35E- and D35G-IκBα also efficiently interacted (Fig. 5E). The data from these studies are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, we found that S36T permitted PIR degradation and β-TrCP recognition but that S32T did not (data not shown). These observations together demonstrated that (i) PIR degradation of mutant IκBαs did not strictly correlate with their β-TrCP interaction properties, as exemplified by the differential effects of D31E- and G33A-IκBα; (ii) the N-terminal consensus motif for PIR degradation is (D/E)-(p)S-(G/A)-X-X-(p)(S/T), where (p) indicates that direct observation of phosphorylation at these sites has not yet been established during this degradation process; and (iii) signal-inducible degradation of mutant IκBαs could occur via an alternative pathway that did not absolutely require an intact β-TrCP recognition sequence in W231.Bcl-XL cells. These findings indicated that PIR degradation did not utilize direct interaction of the β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase with IκBα. This conclusion was also supported by the lack of the requirement for the N-terminal ubiquitylation Lys residues and resistance to various proteasome inhibitors of PIR degradation. Nevertheless, because of the similarities of the consensus motifs for PIR degradation, (D/E)-(p)S-(G/A)-X-X-(p)(S/T), and β-TrCP interaction, DpSGψXpS (67), these studies suggest that a protein with a distinct but somewhat related specificity of interaction may be involved in diverting IκBα to PIR degradation and away from the canonical pathway.

FIG. 5.

Many alterations in the β-TrCP recognition motif of IκBα are not tolerated for its association with β-TrCP. (A) C-terminally HA-tagged wild-type (WT) IκBα was stably expressed in HEK 293 cells. c-myc-ΔF-β-TrCP or vector alone was then transiently transfected. Approximately 40 to 45 h after transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with 10 ng of TNF-α/ml for 30 min after pretreatment with 10 μM MG132 for 30 min (T+M). Whole-cell lysates were prepared. Equal protein amounts were used for the immunoprecipitations and 20% of that amount was used for the input analysis. β-TrCP-associated complexes were precipitated with anti-c-myc antibodies and protein G beads. Coimmunoprecipitation was examined by Western blot (WB) analysis. Immunoprecipitates were first examined with an anti-HA antibody for coimmunoprecipitation of HA-tagged proteins and subsequently examined for coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous IκBα with an anti-IκBα antibody. OT, untreated sample. (B to F) The indicated C-terminally HA-tagged mutant IκBαs were stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Coimmunoprecipitation of the mutant IκBαs with β-TrCP was analyzed by the same method used for panel A.

TABLE 1.

Summary of stably expressed mutant IκBαs analyzed for PIR-mediated degradation, LPS-inducible degradation, and β-TrCP interactiona

| IκBα | PIR degradation | LPS-inducible degradation (WEHI) | Signal-inducible β-TrCP interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| S32/36A | − | − | − |

| K21/22R | +++ | +++ | ND |

| K21/22/67R | +++ | ++ | ND |

| K21/22/38/47/67R | ++ | − | ND |

| D31A | − | ++ | ND |

| D31C | − | ++ | ND |

| D31E | +++ | ++ | +/− |

| D31F | − | ++ | − |

| D31G | − | ++ | ND |

| D31H | − | ++ | − |

| D31I | − | ++ | ND |

| D31K | − | ++ | ND |

| D31L | − | ++ | − |

| D31M | − | ++ | − |

| D31N | − | ++ | ND |

| D31P | − | ++ | ND |

| D31Q | − | − | ND |

| D31R | − | ++ | − |

| D31S | − | ++ | ND |

| D31T | − | ++ | ND |

| D31V | +/− | ++ | − |

| D31W | − | ++ | − |

| D31Y | − | ++ | ND |

| G33A | +++ | ++ | +/− |

| G33R | − | − | − |

| L34I | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| L34R | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| D35E | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| D35G | +++ | ++ | ++ |

++++, wild-type level; +++, ∼75% of wild-type level; ++, ∼50% of wild-type level; +, ∼25% of wild-type level; +/−, less than 25% of wild-type level. −, undetectable; ND, not done.

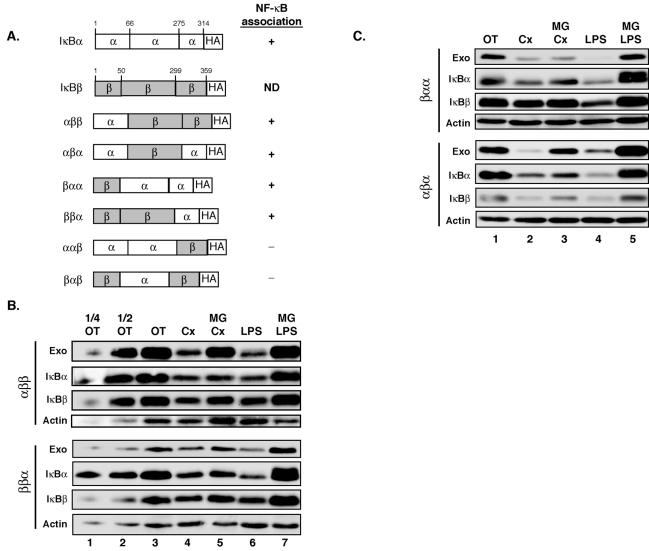

Chimeric IκBα/IκBβ proteins reveal that the ankyrin region of IκBα contains information necessary for PIR degradation.

While our data thus far supported the notion that the N terminus of IκBα contains a consensus motif for PIR degradation, IκBβ also contains this primary structure. Yet, only IκBα is targeted to PIR degradation, whereas IκBβ is spared (41). Thus, it was possible that the above consensus sequence was incomplete and that the subtle differences in the N-terminal sequences between these two proteins dictated their susceptibility to PIR degradation. To determine whether the N-terminal domain of IκBα contained the full information necessary for PIR degradation, we generated a chimeric protein by replacing the N terminus of IκBβ with the corresponding IκBα sequence (Fig. 6A, αββ) based on the NF-κB/IκBα and NF-κB/IκBβ cocrystal structures (25, 28, 36). As a control, we also generated the reciprocal mutant IκBα (βαα). Since free IκBα is known to undergo proteasome-dependent degradation via a pathway distinct from PIR degradation (33, 43, 51), we initially used the ability of these C-terminally HA-tagged chimeras to stably interact with NF-κB in W231.Bcl-XL cells as a measure of their ability to fold correctly. We found that both αββ and βαα efficiently associated with c-Rel and p65 (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). The degradation assay indicated that αββ underwent rapid turnover when stably expressed in W231.Bcl-XL cells (Fig. 6B, top). However, this degradation was highly sensitive to the proteasome inhibitor MG132. In the same extracts, PIR degradation of endogenous IκBα remained highly resistant to MG132 treatment while degradation of endogenous IκBβ was sensitive. In contrast, βαα degradation was slower than that of the endogenous IκBα but remained MG132 resistant (Fig. 6C, top). These results showed (i) that the N-terminal sequence of IκBα could enhance degradation in the context of the IκBβ ankyrin repeats and the C terminus but that this targeting was incomplete for PIR degradation and (ii) that the N-terminal IκBβ sequence could support PIR degradation in the context of the IκBα ankyrin repeats and C terminus, even though it was not as efficient as the N-terminal IκBα sequence. These findings indicated that the principal mechanism behind IκBα selectivity of PIR degradation resided outside of the relatively conserved N-terminal sequence.

FIG. 6.

The ankyrin repeats of IκBα are essential for PIR degradation. (A) Schematic representation of the IκBα/IκBβ chimeric proteins used. α, sequences derived from IκBα; β, sequences derived from IκBβ; HA, HA tag. Association of the different chimeras with NF-κB is listed. (B and C) W231.Bcl-XL cells stably expressing the mutant IκBα/IκBβ proteins were treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml in the absence or presence of MG132 (10 μM; MG) for 3 h. To examine canonically inducible degradation, cells were left untreated or pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 30 min, followed by treatment with 20 μg of LPS/ml for 30 min. One-fourth and one-half of the untreated (OT) samples were loaded (Fig. 6B) to evaluate the amount of protein degraded. Whole-cell pellets were analyzed by Western blotting.

To localize the second cis element required for PIR degradation of IκBα, further chimeric proteins from IκBα and IκBβ were generated as outlined in Fig. 6A. Once again, efficient association between c-Rel and p65 was used to assess proper folding. While αβα and ββα associated with NF-κB proteins efficiently, ααβ and βαβ did not (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The analysis of constitutive degradation of the former two mutant IκBαs (Fig. 6B and C, bottom), along with the N-terminal swap mutant IκBαs described above, suggested that the presence of the ankyrin repeats of IκBα was essential for targeting to the PIR pathway (summarized in Table 2). Moreover, the presence of the C-terminal PEST domain of IκBα or IκBβ had no impact on PIR degradation. All of the chimeric proteins were susceptible to LPS-inducible degradation, indicating that the differential effects of these mutant IκBαs were selective for PIR degradation. Thus, in contrast to the dispensability of the ankyrin repeats for canonical degradation (4, 65, 68), this domain of IκBα was found to be essential for targeting it to PIR degradation.

TABLE 2.

Summary of stably expressed IκBα/IκBβ chimeras analyzed for PIR-mediated and classical degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells

| Chimera | Interaction with c-Rel/p65a | PIR degradation | LPS inducible |

|---|---|---|---|

| αββ | ++ | No | Yes |

| ααβ | +/− | NDb | ND |

| αβα | ++ | No | Yes |

| βαα | ++ | Yes | Yes |

| ββα | ++ | No | Yes |

| βαβ | +/− | ND | ND |

++, wild-type level; +/−, <20% of the wild-type level.

ND, not done.

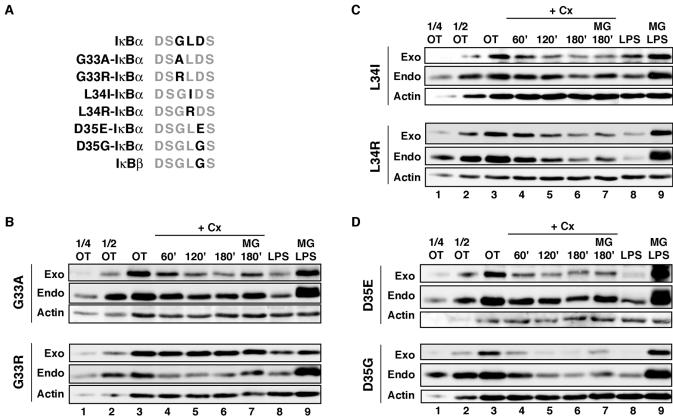

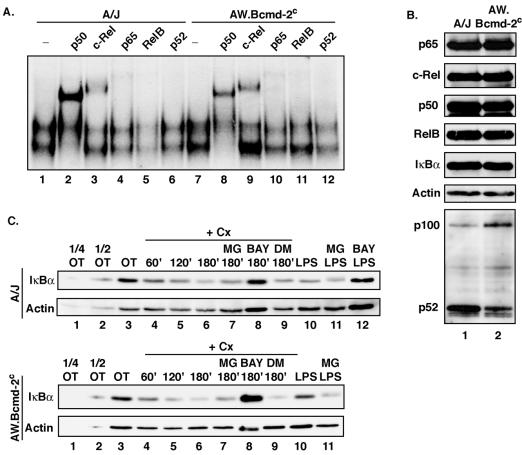

PIR IκBα degradation does not require the same BAFF receptor-dependent signals required for p100 processing.

Recent studies have suggested that BAFF receptor signaling is critical for mature B-cell development via processing of p100 to p52 to form active p52/RelB heterodimers (9). In these studies A/WySnJ mice that harbor a mutation in the BAFF receptor were utilized to demonstrate the requirement for BAFF receptor signaling in p100 processing and the generation of mature B cells, similar to what is found for NFκB1/NFκB2-deficient mice (9, 50). In addition to a mutation in the Bcmd-1/BAFF receptor locus, A/WySnJ mice carry an additional mutation in the Bcmd-2 locus that is responsible for the enhanced mastocytosis observed in A/WySnJ mice (10). We thus employed AW.Bcmd-2c congenic mice that are defective only at the Bcmd-1/BAFF receptor locus but wild type at the Bcmd-2 locus. These mice allowed us to examine whether constitutive p50/c-Rel activity and PIR IκBα degradation occurred in the absence of BAFF receptor-dependent signals required to mediate p100 processing.

First, splenocytes were isolated from both A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c mice which have been autoreconstituted by sublethal radiation to capture mostly the transitional B cells in the spleen for direct comparison (1). When constitutive NF-κB activity was analyzed by EMSAs, it was found that cells from the AW.Bcmd-2c mice had constitutive p50/c-Rel activity (Fig. 7A), which was surprisingly similar to that of the A/J counterpart, especially for the c-Rel component. As a control, we verified that p100 processing to p52 was indeed markedly reduced in B cells isolated from the AW.Bcmd-2c mice relative to that in B cells from A/J mice, while the expression levels of all other known NF-κB family members were similar (Fig. 7B). Moreover, constitutive IκBα degradation occurred in B cells of both lines of mice at similar levels and was resistant to inhibition by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 7C). Finally, similar to the results for the W231.Bcl-XL cell line, we found that PIR IκBα degradation in B cells from both wild-type and mutant mice was sensitive to the IKK inhibitor Bay 11-7082. Our findings are consistent with the model in which neither PIR IκBα degradation nor constitutive p50/c-Rel activity requires the same BAFF receptor-dependent signaling events that are required for p100 processing.

FIG. 7.

Constitutive p50/c-Rel activity and PIR IκBα degradation do not require intact BAFF receptor signaling. (A) Splenocytes from A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c radiation-induced autoreconstituted mice were isolated, and nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA. The indicated antibodies were added for supershift analysis. (B) B cells were isolated from A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c radiation-induced autoreconstituted mice by MACS purification, and whole-cell pellets were subjected to Western blot analysis for expression of the indicated NF-κB and IκB family members. (C) B cells were isolated from A/J and AW.Bcmd-2c mice by MACS purification from splenocytes and treated with 25 μg of cycloheximide (Cx)/ml for the indicated times in the absence or presence of MG132 (10 μM; MG), Bay 11-7082 (25 μM; BAY), or DMSO (0.1% DM). For the LPS samples, cells were left untreated (OT) or pretreated with either 10 μM MG132 (MG) or 25 μM Bay 11-7082 for 1 h, followed by treatment with 20 μg of LPS/ml for 2 h. Whole-cell pellets were analyzed by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

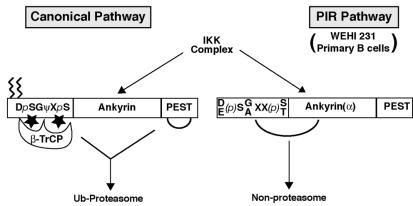

We have previously identified a constitutive IκBα degradation pathway in WEHI-231 B cells that is proteasome inhibitor resistant (41). In this study we provide evidence that PIR IκBα degradation is mediated by an IKK-dependent, but β-TrCP-independent, mechanism thereby explaining the lack of requirement for the N-terminal ubiquitylation sites and proteasome activity for IκBα degradation in these cells. Our analysis indicated that the PIR degradation pathway differs from the well-established canonical pathway (Fig. 8) in a significant way. While canonical IKK-dependent phosphorylation of IκBα and IκBβ leads to their recognition and ubiquitylation by β-TrCP and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome (31, 55, 66), PIR degradation requires IKK activity but did not appear to require direct association with this E3 ubiquitin ligase. Consistently, a different consensus sequence for PIR degradation from that required for β-TrCP recognition emerged through these mutagenesis studies. This suggests that a molecule other than β-TrCP may potentially guide IκBα to PIR degradation. It is also important that this difference of E3 involvement may be due to the potential lack of direct phosphorylation of IκBα by IKK in the PIR pathway, even though the IKK activity is apparently critical. Despite the ease of its detection in the canonical pathway, we were unable to observe it in the PIR pathway.

FIG. 8.

PIR IκBα degradation. The model depicts the cis elements required for canonical versus PIR IκBα degradation.

A number of nonconventional IκBα degradation pathways that are distinct from PIR IκBα degradation have been identified. Studies have suggested that basal degradation of IκBα requires the C-terminal CK2-dependent phosphorylation sites and the ankyrin repeats, but this basal degradation is proteasome dependent and N terminus independent (33, 37, 51, 64). Calpain-mediated degradation has been associated with a number of NF-κB activation processes, including TNF-α in HepG2 cells, neoplastic cell development, and Her-2/neu regulation in breast cancer cells (21, 45, 46). It has also been observed that TNF-α-induced mitochondrial IκBα degradation is, at least partially, dependent on calpain (11). Serum deprivation can also promote phosphorylation- and ubqiuitylation-independent lysosomal degradation of IκBα (12). Moreover, caspase-dependent N-terminal cleavage of IκBα has also been observed to occur at Asp31 (3, 48). In contrast, PIR IκBα degradation requires both the N terminus and ankyrin repeats of IκBα. Furthermore, a mutant IκBα lacking the C-terminal PEST domain was still susceptible to PIR degradation, and the calpain inhibitor PD150606 (which targets the calcium binding domain of calpain) failed to block PIR degradation, indicating that calpain is unlikely to be directly involved in PIR degradation (56a). Moreover, D31E-IκBα still undergoes PIR degradation, suggesting that caspase-dependent cleavage of IκBα C-terminal to Asp31 is not involved in this pathway. Finally, from this study and our previous observations, PIR IκBα degradation is not sufficiently inhibited by proteasome, calpain, lysosomal, or caspase inhibitors, suggesting that PIR degradation of IκBα may occur through an alternative degradation pathway (41, 56, 56a).

While certain N-terminal residues of IκBα were critical for PIR degradation, these residues are conserved in IκBβ, a non-PIR degradation substrate in WEHI-231 and W231.Bcl-XL cells. Our chimeric studies using IκBα and IκBβ indicated that this N-terminal consensus sequence was insufficient for complete targeting to the PIR pathway. It has been reported that the canonical pathway requires the N terminus or both the N and C termini of IκBα but not the ankyrin repeats (4, 65, 68, 72). In contrast, PIR IκBα degradation was strictly dependent on its ankyrin repeats, even though it was supported by the N terminus of either IκBα or IκBβ. This dependence was so specific to the IκBα ankyrin repeats that even those of IκBβ could not substitute. Although the mechanism by which this specificity is carried out is unclear, previous studies have reported that differences in the ankyrin repeats of IκBα and IκBβ lead to their different patterns of nuclear localization and NF-κB inhibition (6, 57). These studies suggested that the ankyrin repeats of IκBα and IκBβ have the capacity to perform different tasks. The major difference in ankyrin repeat structure between IκBα and IκBβ is the presence of a loop between ankyrin repeats 3 and 4 of IκBβ (25, 28, 36). When we analyzed the PIR degradation susceptibility of mutant IκBαs with the IκBβ loop introduced between ankyrin repeats 3 and 4 or mutant IκBα/IκBβ chimeras with the loop deleted, we were unable to observe a strict correlation between the absence of the loop domain and susceptibility to PIR degradation (S. O'Connor, unpublished observations). These results indicate that finer mapping of the ankyrin repeat domain is required to uncover the sequences required to target IκBα to PIR degradation. Moreover, our findings suggest that a molecular component(s) that recognizes IκBα likely detects both the N-terminal consensus sequence and an IκBα ankyrin repeat-specific motif to mediate PIR degradation (Fig. 8). Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that different molecular components recognize the N terminus and the ankyrin repeats of IκBα for PIR degradation.

Interestingly, during these studies, we uncovered an alternative inducible IκBα degradation pathway in W231.Bcl-XL cells. We found that mutant IκBαs that could not associate with β-TrCP were still capable of undergoing inducible IKK-dependent and proteasome-mediated degradation by multiple distinct inducers in W231.Bcl-XL cells. Although this observation forced us to analyze β-TrCP association of mutant IκBαs in the stable HEK293 cell system, it revealed that β-TrCP association is not absolutely required for proteasome-dependent inducible IκBα degradation in W231.Bcl-XL cells. These findings raise the possibility that certain cells may adopt an alternative proteasome-dependent IκBα degradation pathway when β-TrCP function is disrupted. These findings may have a bearing on a resistance mechanism against future drugs that target β-TrCP for therapeutic intervention of NF-κB pathways.

While the above structure-function analyses suggested that PIR degradation is regulated by an unprecedented mechanism, the physiological relevance of this pathway was elusive. Importantly, our studies revealed that PIR IκBα degradation and constitutive p50/c-Rel activity in primary B cells do not rely on the same BAFF receptor signaling mechanism that is required for IKKα-dependent p100 processing and generation of p52/RelB heterodimers. Genetic studies indicated that this BAFF receptor signaling pathway is critical for the survival of transitional B cells (9, 29, 53). However, additional genetic studies revealed that IKKβ and NEMO, components not required for the p100 processing pathway, are also critical for proper development of B cells at the same transitional stages (44). Moreover, nfkb1−/− c-rel−/− double-knockout mice also displayed a deficiency of some of the same transitional B cells (e.g., a lack of marginal-zone B cells) (47), indicating that the development of these transitional B cells depends on nonredundant activities of p52/RelB and p50/c-Rel NF-κB complexes. Additionally, the development of CD5+ B1 B cells that primarily reside in the peritoneum was severely compromised in mice deficient for NF-κB1/c-Rel (47) (and also reported to be reduced in conditional IKKβ- and NEMO-deficient mice [44]). However, these cells were not reduced in mice lacking BAFF or containing the mutant BAFF receptor (A/WySnJ) (34, 50), indicating that p50/c-Rel complexes have an additional function distinct from that of p52/RelB in the generation of the B1 B-cell repertoire. Consistent with this notion, B1 B-cell lines, such as CH31 and CH33, are known to exhibit continuous, rapid IκBα degradation and nuclear c-Rel complexes, similar to the WEHI-231 cell line (15, 40). Thus, our analysis of the PIR degradation pathway may lead to understanding the biochemical mechanism and ultimately the physiological signal(s) that controls p50/c-Rel activation during development of both transitional B cells and the B1 B-cell subset.

Elucidation of PIR IκBα degradation may also have implications for understanding constitutive NF-κB activity in a number of cancer cells. Several cancer cell types rely on constitutive NF-κB activity, via rapid IκBα degradation, for cell survival (13, 32, 61). The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 (Velcade, bortezomib) is approved for treatment of multiple myelomas and is undergoing further clinical tests (49). While treatment with PS-341 is thought to inhibit constitutive NF-κB activity maintained via canonical proteasome-mediated degradation of IκBα, many patients are resistant or develop resistance to this treatment (22, 49). It is also possible that certain fractions of human malignancies may switch from the canonical, proteasome-dependent pathway to the PIR IκBα degradation pathway to maintain a constitutive NF-κB survival pathway in the face of continuous proteasome inhibitor treatment. We have seen this type of switch to maintain constitutive NF-κB activation during pre-B-cell differentiation in vitro (17). Thus, it will be of great interest to determine whether or not PIR IκBα degradation is employed in Velcade-resistant multiple myelomas and other human malignancies.

In summary, the present study has revealed a novel mechanism of IKK-dependent IκBα degradation that does not rely on β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitylation or proteasomal degradation. We found that unique features of IκBα present in the N-terminal domain and the ankyrin repeats make it susceptible to PIR degradation (Fig. 8). Furthermore, this continuous PIR degradation occurs in B cells in the absence of functional BAFF receptor-dependent signaling. Further dissection of the PIR degradation pathway may prove fruitful for improving our understanding of both the regulatory mechanisms involved in different NF-κB complexes in normal B cell development and events associated with the development of proteasome inhibitor resistance in cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kei Tashiro for providing K3R- and K5R-IκBα clones, Zhijian Chen for providing c-myc-ΔF-β-TrCP, Bradley Seufzer for technical support, Cindy Chan for the construction of some mutant IκBαs, and the Miyamoto lab members for helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by funding from an American Heart Association Predoctoral fellowship to S.O.; NIH training grant (T32GM07215) for S.O., S.D.S., and I.J.A.; and NIH R01-CA77474, NIH R01-CA81065, and the Shaw Scientist Award from the Milwaukee Foundation to S.M.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allman, D., R. C. Lindsley, W. DeMuth, K. Rudd, S. A. Shinton, and R. R. Hardy. 2001. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J. Immunol. 167:6834-6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bargou, R. C., F. Emmerich, D. Krappmann, K. Bommert, M. Y. Mapara, W. Arnold, H. D. Royer, E. Grinstein, A. Greiner, C. Scheidereit, and B. Dorken. 1997. Constitutive nuclear factor-κB-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin's disease tumor cells. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2961-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkett, M., D. Xue, H. R. Horvitz, and T. D. Gilmore. 1997. Phosphorylation of IκB-α inhibits its cleavage by caspase CPP32 in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 272:29419-29422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, K., G. Franzoso, L. Baldi, L. Carlson, L. Mills, Y. C. Lin, S. Gerstberger, and U. Siebenlist. 1997. The signal response of IκBα is regulated by transferable N- and C-terminal domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3021-3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancro, M. P., D. M. Allman, C. E. Hayes, V. M. Lentz, R. G. Fields, A. P. Sah, and M. Tomayko. 1998. B cell maturation and selection at the marrow-periphery interface. Immunol. Res. 17:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y., J. Wu, and G. Ghosh. 2003. κB-Ras binds to the unique insert within the ankyrin repeat domain of IκBβ and regulates cytoplasmic retention of IκBβ × NF-κB complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:23101-23106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Z., J. Hagler, V. J. Palombella, F. Melandri, D. Scherer, D. Ballard, and T. Maniatis. 1995. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 9:1586-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiao, P. J., S. Miyamoto, and I. M. Verma. 1994. Autoregulation of IκBα activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:28-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claudio, E., K. Brown, S. Park, H. Wang, and U. Siebenlist. 2002. BAFF-induced NEMO-independent processing of NF-κB2 in maturing B cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clise-Dwyer, K., I. J. Amanna, J. L. Duzeski, F. E. Nashold, and C. E. Hayes. 2001. Genetic studies of B-lymphocyte deficiency and mastocytosis in strain A/WySnJ mice. Immunogenetics 53:729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogswell, P. C., D. F. Kashatus, J. A. Keifer, D. C. Guttridge, J. Y. Reuther, C. Bristow, S. Roy, D. W. Nicholson, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 2003. NF-κB and IκBα are found in the mitochondria. Evidence for regulation of mitochondrial gene expression by NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 278:2963-2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuervo, A. M., W. Hu, B. Lim, and J. F. Dice. 1998. IκB is a substrate for a selective pathway of lysosomal proteolysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:1995-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, R. E., K. D. Brown, U. Siebenlist, and L. M. Staudt. 2001. Constitutive nuclear factor κB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J. Exp. Med. 194:1861-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiDonato, J. A., M. Hayakawa, D. M. Rothwarf, E. Zandi, and M. Karin. 1997. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 388:548-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doerre, S., and R. B. Corley. 1999. Constitutive nuclear translocation of NF-κB in B cells in the absence of IκB degradation. J. Immunol. 163:269-277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffey, D. C., Z. Chen, G. Dong, F. G. Ondrey, J. S. Wolf, K. Brown, U. Siebenlist, and C. Van Waes. 1999. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor-κBα of nuclear factor-κB in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 59:3468-3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields, E. R., B. J. Seufzer, E. M. Oltz, and S. Miyamoto. 2000. A switch in distinct IκBα degradation mechanisms mediates constitutive NF-κB activation in mature B cells. J. Immunol. 164:4762-4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geleziunas, R., S. Ferrell, X. Lin, Y. Mu, E. T. Cunningham, Jr., M. Grant, M. A. Connelly, J. E. Hambor, K. B. Marcu, and W. C. Greene. 1998. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax induction of NF-κB involves activation of the IκB kinase α (IKKα) and IKKβ cellular kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5157-5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl.):S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grumont, R. J., and S. Gerondakis. 1994. The subunit composition of NF-κB complexes changes during B-cell development. Cell Growth Differ. 5:1321-1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han, Y., S. Weinman, I. Boldogh, R. K. Walker, and A. R. Brasier. 1999. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-inducible IκBα proteolysis mediated by cytosolic m-calpain. A mechanism parallel to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway for nuclear factor-κb activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:787-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hideshima, T., D. Chauhan, P. Richardson, C. Mitsiades, N. Mitsiades, T. Hayashi, N. Munshi, L. Dang, A. Castro, V. Palombella, J. Adams, and K. C. Anderson. 2002. NF-κB as a therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16639-16647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, T. T., S. L. Feinberg, S. Suryanarayanan, and S. Miyamoto. 2002. The zinc finger domain of NEMO is selectively required for NF-κB activation by UV radiation and topoisomerase inhibitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5813-5825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, T. T., S. M. Wuerzberger-Davis, B. J. Seufzer, S. D. Shumway, T. Kurama, D. A. Boothman, and S. Miyamoto. 2000. NF-κB activation by camptothecin. A linkage between nuclear DNA damage and cytoplasmic signaling events. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9501-9509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huxford, T., S. Malek, and G. Ghosh. 2000. Preparation and crystallization of dynamic NF-κB.IκB complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32800-32806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imbert, V., R. A. Rupec, A. Livolsi, H. L. Pahl, E. B. Traenckner, C. Mueller-Dieckmann, D. Farahifar, B. Rossi, P. Auberger, P. A. Baeuerle, and J. F. Peyron. 1996. Tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB-α activates NF-κB without proteolytic degradation of IκB-α. Cell 86:787-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue, J., L. D. Kerr, L. J. Ransone, E. Bengal, T. Hunter, and I. M. Verma. 1991. c-rel activates but v-rel suppresses transcription from κB sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:3715-3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs, M. D., and S. C. Harrison. 1998. Structure of an IκBα/NF-κB complex. Cell 95:749-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaisho, T., K. Takeda, T. Tsujimura, T. Kawai, F. Nomura, N. Terada, and S. Akira. 2001. IκB kinase alpha is essential for mature B cell development and function. J. Exp. Med. 193:417-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang, J. L., I. S. Pack, S. M. Hong, H. S. Lee, and V. Castranova. 2000. Silica induces nuclear factor-κB activation through tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB-α in RAW264.7 macrophages. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 169:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karin, M., and Y. Ben-Neriah. 2000. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[κ]B activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:621-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karin, M., Y. Cao, F. R. Greten, and Z. W. Li. 2002. NF-κB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:301-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krappmann, D., F. G. Wulczyn, and C. Scheidereit. 1996. Different mechanisms control signal-induced degradation and basal turnover of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB α in vivo. EMBO J. 15:6716-6726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lentz, V. M., C. E. Hayes, and M. P. Cancro. 1998. Bcmd decreases the life span of B-2 but not B-1 cells in A/WySnJ mice. J. Immunol. 160:3743-3747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liou, H. C., W. C. Sha, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1994. Sequential induction of NF-κB/Rel family proteins during B-cell terminal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:5349-5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malek, S., D. B. Huang, T. Huxford, S. Ghosh, and G. Ghosh. 2003. X-ray crystal structure of an IκBβ × NF-κB p65 homodimer complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278:23094-23100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McElhinny, J. A., S. A. Trushin, G. D. Bren, N. Chester, and C. V. Paya. 1996. Casein kinase II phosphorylates IκBα at S-283, S-289, S-293, and T-291 and is required for its degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:899-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercurio, F., H. Zhu, B. W. Murray, A. Shevchenko, B. L. Bennett, J. Li, D. B. Young, M. Barbosa, M. Mann, A. Manning, and A. Rao. 1997. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science 278:860-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyamoto, S., P. J. Chiao, and I. M. Verma. 1994. Enhanced IκBα degradation is responsible for constitutive NF-κB activity in mature murine B-cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3276-3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamoto, S., M. J. Schmitt, and I. M. Verma. 1994. Qualitative changes in the subunit composition of κB-binding complexes during murine B-cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5056-5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyamoto, S., B. J. Seufzer, and S. D. Shumway. 1998. Novel IκBα proteolytic pathway in WEHI231 immature B cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:19-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palombella, V. J., O. J. Rando, A. L. Goldberg, and T. Maniatis. 1994. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-κB1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-κB. Cell 78:773-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pando, M. P., and I. M. Verma. 2000. Signal-dependent and -independent degradation of free and NF-κB-bound IκBα. J. Biol. Chem. 275:21278-21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasparakis, M., M. Schmidt-Supprian, and K. Rajewsky. 2002. IκB kinase signaling is essential for maintenance of mature B cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petranka, J., G. Wright, R. A. Forbes, and E. Murphy. 2001. Elevated calcium in preneoplastic cells activates NF-κB and confers resistance to apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:37102-37108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pianetti, S., M. Arsura, R. Romieu-Mourez, R. J. Coffey, and G. E. Sonenshein. 2001. Her-2/neu overexpression induces NF-κB via a PI3-kinase/Akt pathway involving calpain-mediated degradation of IκB-α that can be inhibited by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Oncogene 20:1287-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pohl, T., R. Gugasyan, R. J. Grumont, A. Strasser, D. Metcalf, D. Tarlinton, W. Sha, D. Baltimore, and S. Gerondakis. 2002. The combined absence of NF-κB1 and c-Rel reveals that overlapping roles for these transcription factors in the B cell lineage are restricted to the activation and function of mature cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4514-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuther, J. Y., and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1999. Apoptosis promotes a caspase-induced amino-terminal truncation of IκBα that functions as a stable inhibitor of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20664-20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson, P. G., B. Barlogie, J. Berenson, S. Singhal, S. Jagannath, D. Irwin, S. V. Rajkumar, G. Srkalovic, M. Alsina, R. Alexanian, D. Siegel, R. Z. Orlowski, D. Kuter, S. A. Limentani, S. Lee, T. Hideshima, D. L. Esseltine, M. Kauffman, J. Adams, D. P. Schenkein, and K. C. Anderson. 2003. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:2609-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiemann, B., J. L. Gommerman, K. Vora, T. G. Cachero, S. Shulga-Morskaya, M. Dobles, E. Frew, and M. L. Scott. 2001. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science 293:2111-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwarz, E. M., D. Van Antwerp, and I. M. Verma. 1996. Constitutive phosphorylation of IκBα by casein kinase II occurs preferentially at serine 293: requirement for degradation of free IκBα. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3554-3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sen, R., and D. Baltimore. 1986. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell 46:705-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senftleben, U., Y. Cao, G. Xiao, F. R. Greten, G. Krahn, G. Bonizzi, Y. Chen, Y. Hu, A. Fong, S. C. Sun, and M. Karin. 2001. Activation by IKKα of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-κB signaling pathway. Science 293:1495-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen, J., P. Channavajhala, D. C. Seldin, and G. E. Sonenshein. 2001. Phosphorylation by the protein kinase CK2 promotes calpain-mediated degradation of IκBα. J. Immunol. 167:4919-4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirane, M., S. Hatakeyama, K. Hattori, and K. Nakayama. 1999. Common pathway for the ubiquitination of IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBɛ mediated by the F-box protein FWD1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28169-28174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shumway, S. D., C. M. Berchtold, M. N. Gould, and S. Miyamoto. 2002. Evidence for unique calmodulin-dependent nuclear factor-κB regulation in WEHI-231 B cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 61:177-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56a.Shumway, S. D., and S. Miyamoto. A mechanistic insight into a proteasome-independent constitutive IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation pathway in WEHI-231 B cells. Biochem. J., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Simeonidis, S., D. Stauber, G. Chen, W. A. Hendrickson, and D. Thanos. 1999. Mechanisms by which IκB proteins control NF-κB activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:49-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solan, N. J., H. Miyoshi, E. M. Carmona, G. D. Bren, and C. V. Paya. 2002. RelB cellular regulation and transcriptional activity are regulated by p100. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1405-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sovak, M. A., R. E. Bellas, D. W. Kim, G. J. Zanieski, A. E. Rogers, A. M. Traish, and G. E. Sonenshein. 1997. Aberrant nuclear factor-κB/Rel expression and the pathogenesis of breast cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2952-2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spencer, E., J. Jiang, and Z. J. Chen. 1999. Signal-induced ubiquitination of IκBα by the F-box protein Slimb/β-TrCP. Genes Dev. 13:284-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun, S. C., J. Elwood, C. Beraud, and W. C. Greene. 1994. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax activation of NF-κB/Rel involves phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and RelA (p65)-mediated induction of the c-rel gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:7377-7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun, S. C., P. A. Ganchi, D. W. Ballard, and W. C. Greene. 1993. NF-κB controls expression of inhibitor IκBα: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science 259:1912-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Traenckner, E. B., S. Wilk, and P. A. Baeuerle. 1994. A proteasome inhibitor prevents activation of NF-κB and stabilizes a newly phosphorylated form of IκB-α that is still bound to NF-κB. EMBO J. 13:5433-5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Antwerp, D. J., and I. M. Verma. 1996. Signal-induced degradation of IκBα: association with NF-κB and the PEST sequence in IκBα are not required. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6037-6045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whiteside, S. T., M. K. Ernst, O. LeBail, C. Laurent-Winter, N. Rice, and A. Israel. 1995. N- and C-terminal sequences control degradation of MAD3/IκBα in response to inducers of NF-κB activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5339-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu, C., and S. Ghosh. 1999. β-TrCP mediates the signal-induced ubiquitination of IκBβ. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29591-29594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu, G., G. Xu, B. A. Schulman, P. D. Jeffrey, J. W. Harper, and N. P. Pavletich. 2003. Structure of a β-TrCP1-Skp1-β-catenin complex: destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF(β-TrCP1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 11:1445-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wulczyn, F. G., D. Krappmann, and C. Scheidereit. 1998. Signal-dependent degradation of IκBα is mediated by an inducible destruction box that can be transferred to NF-κB, bcl-3 or p53. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1724-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiao, G., E. W. Harhaj, and S. C. Sun. 2001. NF-κB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100. Mol. Cell 7:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yaron, A., H. Gonen, I. Alkalay, A. Hatzubai, S. Jung, S. Beyth, F. Mercurio, A. M. Manning, A. Ciechanover, and Y. Ben-Neriah. 1997. Inhibition of NF-κ-B cellular function via specific targeting of the I-κ-B-ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 16:6486-6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yaron, A., A. Hatzubai, M. Davis, I. Lavon, S. Amit, A. M. Manning, J. S. Andersen, M. Mann, F. Mercurio, and Y. Ben-Neriah. 1998. Identification of the receptor component of the IκBα-ubiquitin ligase. Nature 396:590-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zandi, E., Y. Chen, and M. Karin. 1998. Direct phosphorylation of IκB by IKKα and IKKβ: discrimination between free and NF-κB-bound substrate. Science 281:1360-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.