Abstract

Background

Parenting programmes are a potentially important means of supporting teenage parents and improving outcomes for their children, and parenting support is a priority across most Western countries. This review updates the previous version published in 2001.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of parenting programmes in improving psychosocial outcomes for teenage parents and developmental outcomes in their children.

Search methods

We searched to find new studies for this updated review in January 2008 and May 2010 in CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, ASSIA, CINAHL, DARE, ERIC, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts and Social Science Citation Index. The National Research Register (NRR) was last searched in May 2005 and UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database in May 2010.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials assessing short‐term parenting interventions aimed specifically at teenage parents and a control group (no‐treatment, waiting list or treatment‐as‐usual).

Data collection and analysis

We assessed the risk of bias in each study. We standardised the treatment effect for each outcome in each study by dividing the mean difference in post‐intervention scores between the intervention and control groups by the pooled standard deviation.

Main results

We included eight studies with 513 participants, providing a total of 47 comparisons of outcome between intervention and control conditions. Nineteen comparisons were statistically significant, all favouring the intervention group. We conducted nine meta‐analyses using data from four studies in total (each meta‐analysis included data from two studies). Four meta‐analyses showed statistically significant findings favouring the intervention group for the following outcomes: parent responsiveness to the child post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.91, 95% CI ‐1.52 to ‐0.30, P = 0.04); infant responsiveness to mother at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.65, 95% CI ‐1.25 to ‐0.06, P = 0.03); and an overall measure of parent‐child interactions post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.31 to ‐0.11, P = 0.02), and at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐1.51 to ‐0.30, P = 0.004). The results of the remaining five meta‐analyses were inconclusive.

Authors' conclusions

Variation in the measures used, the included populations and interventions, and the risk of bias within the included studies limit the conclusions that can be reached. The findings provide some evidence to suggest that parenting programmes may be effective in improving a number of aspects of parent‐child interaction both in the short‐ and long‐term, but further research is now needed.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Female, Humans, Child Development, Age Factors, Mother‐Child Relations, Parenting, Parenting/psychology, Program Evaluation, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Parenting programmes for teenage parents and their children

Adolescent parents face a range of problems. They are often from very deprived backgrounds; they can experience a range of mental health problems and a lack of social support; they often lack knowledge about child development and effective parenting skills, and they have developmental needs of their own. Possibly for these reasons, the children of teenage parents often have poor outcomes.

A range of interventions are being used to promote the well‐being of teenage parents and their children. Parenting programmes have been found to be effective in improving psychosocial health in parents more generally (including reducing anxiety and depression, and improving self‐esteem), alongside a range of developmental outcomes for children. This review therefore investigated the impact of parenting programmes aimed specifically at teenage parents on outcomes for both them and their children.

The findings are based on eight studies measuring a variety of outcomes, using a range of standardised measures. It was possible to combine results (meta‐analysis) for nine comparisons. Results from four of these meta‐analyses suggest that parenting programmes may be effective in improving parent responsiveness to the child, and parent‐child interaction, both post‐intervention and at follow‐up. Infant responsiveness to the mother also showed improvement at follow‐up. The results of the other five meta‐analyses we carried out were inconclusive.

Further rigorous research is needed that provides both short‐ and long‐term follow‐up of the children of teenage parents, and that assesses the benefits of parenting programmes for young fathers as well as young mothers.

Background

Description of the condition

The rate of births to teenage parents

Research examining the rate of births to women aged 15 to 19 in the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) countries showed that the lowest birth rates (2.9 to 6.5 per 1,000) were to be found in Korea, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Sweden, and that the highest birth rates (52.1 per 1,000) were to be found in the USA, which has about four times the European Union average, and the UK, which has the highest teenage birth rate in Europe (30.8 per 1,000) (UNICEF 2001). Although these figures show a fall across many countries (DCSF 2008), teenage pregnancy continues to be regarded as a health problem in the Western world (As‐Sanie 2004). While there are cultural contexts worldwide in which it may not be unusual for children to be born to teenage mothers, there is some evidence that teenage pregnancy is also a concern in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Parekh 1997; Pyper 2000; Save the Children 2004).

Outcomes of teenage pregnancy

Although there is some recognition that teenage pregnancy can be a positive experience, particularly in the later teenage years (Harden 2006), there is also evidence of adverse health and social outcomes from a number of cohort studies that have controlled for selection effects (for example, Emisch 2003; Pevalin 2003 cited in Harden 2009). For example, an overview of the evidence about the impact of teenage pregnancy on a range of aspects of well‐being (HDA 2004) found that teenage mothers experienced more socio‐economic deprivation, mental health problems (particularly during the first three years following the birth), and drug problems. They had lower levels of educational attainment, were more likely to be living in deprived neighbourhoods, and their partners were more antisocial and abusive. It also showed lower rates of breast feeding in teenage mothers. Younger parents also often lack knowledge of child development and effective parenting skills (Bucholz 1993), due in part to their inexperience of life more generally (Utting 1993).

Young parenthood is often viewed as reinforcing social disadvantage because of the perceived consequences in terms of the teenage mother's life chances (Social Exclusion Unit 1999 cited in Duncan 2007), and also because of the estimated cost to society. For example, in the UK, the annual cost to the National Health Service of pregnancy in women under 18 years of age is over £63 million (HDA 2004).

Research also suggests that the children of teenage parents may have poorer outcomes in terms of educational attainment, emotional and behavioural problems, and higher rates of illness, accidents and injuries (Moffitt 2002 cited in HDA 2004). Some studies point to a higher risk of child maltreatment among younger parents (Bucholz 1993; Wakschlag 2000), although it is recognised that this risk is confounded by the environmental factors experienced by many younger parents, including socio‐economic deprivation, lack of social support, depression, low self‐esteem and emotional stress (Utting 1993). Other research has also suggested that poverty and lack of access to services are responsible for the poor outcomes experienced by teenage parents and their children, rather than the age of the mother per se (Cunnington 2001; Allen 2007).

Description of the intervention

Parenting programmes for teenage parents

Services targeting teenage parents remain a policy priority in many Western countries including the UK (DCSF 2007) and Australia (Karin 2002). A range of interventions have been developed to meet their needs including home visiting and parenting programmes (HDA 2004), and the focus of the current review is the effectiveness of parenting programmes designed explicitly to address the needs of teenage parents.

Standard parenting programmes are focused short‐term interventions aimed at helping parents improve their functioning as a parent, and their relationship with their child, and preventing or treating a range of child emotional and behavioural problems by increasing the knowledge, skills and understanding of parents. They typically involve the use of a manualised and standardised programme or curriculum, and are underpinned by a number of theoretical approaches (including Behavioural, Family Systems, Adlerian, and Psychodynamic). They can involve the use of a range of techniques in their delivery including discussion, role play, watching video vignettes, and homework. They are typically offered to parents over the course of eight to 12 weeks, for about one to two hours each week, in a range of settings including hospital/social work clinics and community‐based settings such as GP surgeries, schools and churches.

Although parenting programmes that are explicitly designed for teenage parents have much in common with standard parenting programmes, there may be important variations. For example, parenting programmes for teenagers may devote more time to factors that affect this 'hard‐to‐reach' group in terms of influencing their uptake and continuation with the programme, and in specifically addressing their communication needs. Such programmes may also focus more explicitly on aspects of parenting that research suggests may be difficult for teenage parents, such as understanding the developmental needs of their child.

How the intervention might work

The evidence suggests that adolescent parents have unmet developmental needs of their own; that they are often from very deprived backgrounds; that they may be experiencing a range of mental health problems and lack of social support, and that they often lack knowledge about child development and effective parenting skills. The evidence suggests that parenting programmes have learning components that appear to address many of the issues confronting teenage parents. For example, a meta‐ethnography of qualitative studies suggests that the acquisition of knowledge, skills and understanding, together with feelings of acceptance and support from other parents in the parenting group, are important in enabling parents to regain control, and in the development of feelings of being able to cope, which then leads to a reduction in feelings of guilt and social isolation, increased empathy with their children, and greater confidence in dealing with their behaviour (Kane 2007). Parenting programmes that improve the mental health of the parents (Barlow 2001a), and their capacity to regulate their emotions (Day 2010), may also help in terms of their functioning as parents. These findings were supported by recent research examining the effectiveness of parenting programmes delivered in disadvantaged areas, which suggested that the key factors in bringing about change were the provision of emotional support, and the development of parenting skills that improve the relationship with the child in ways that support positive behaviour and offer strategies to deal with negative or challenging behaviours (Scott 2006). The evidence also suggests that parenting programmes are effective in improving a range of outcomes in young children up to three years of age (Barlow 2010), and emotional and behavioural outcomes in children aged three to 14 years (NICE 2006). Programmes that explicitly target teenagers and the problems that they experience may be even more effective for teenage parents and their children.

Why it is important to do this review

While recent reductions in the rates of births to teenagers may be testament to the success of some of the many prevention initiatives now targeting teenage parents, the prevalence of teenage pregnancy continues to be high. Interventions such as parenting programmes that potentially address some of the aetiological factors involved in the transmission of poor outcomes from teenage parents to their children (for example, by improving parental mental health and maximizing parenting skills) may be crucial in optimising well‐being for both teenage parents and their children (Mental Health Europe 1999; Social Exclusion Unit 1999). There is a need to establish the impact of brief, structured parenting programmes, specifically targeting teenage parents, in terms of their benefits both for teenage parents and for their children.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of individual and group‐based parenting programmes in improving the psychosocial health of teenage parents and the developmental health of their children.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised trials in which participants were allocated to an experimental or a control group, the latter being a waiting‐list or no‐treatment group (including treatment‐as‐usual or normal service provision).

Types of participants

Parents aged 20 or under, from either clinical or population samples, and their infants/children. The upper age limit of 20 was used because this is consistent with the WHO definition of adolescent parents, thereby enabling the inclusion of international studies.

Types of interventions

Studies evaluating parenting programmes that met all of the following criteria were included in the review:

Individual or group‐based format;

Offered ante‐ and post‐natally or just post‐natally to teenage mothers and/or teenage fathers;

Based on the use of a structured format;

Focusing on the improvement of parenting attitudes, practices, skills/knowledge, or well‐being.

Parenting programmes which met any of the following criteria were excluded from the review:

Standard antenatal programmes specifically addressing the pregnancy care needs of teenagers, and programmes provided during the ante‐natal period only;

Programmes not specifically aimed at adolescent parents;

Evaluations of programmes that were aimed at parents of disabled children, children with long‐term health problems or pre‐term infants;

Programmes involving direct work with the children of teenage parents;

Programmes that were aimed exclusively at the prevention or reduction of teenage pregnancy;

Programmes in which the parenting programme was combined with a home visiting intervention.

While home visiting programmes, and parenting programmes combined with home visiting programmes, have been excluded from this review, manualised, short‐term (i.e. less than 20 week) parenting programmes that are delivered on a one‐to‐one basis in the home have been included. This reflects the fact that home‐visiting programmes are qualitatively different interventions (for example, broad based support which is provided on a frequent basis over an extended period of time) to parenting programmes that are delivered in the home (for example, brief, structured programmes with a specific focus on parenting).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

A. Parental psychosocial outcomes including:

1. psychosocial heath;

2. parenting knowledge;

3. parenting behaviours and skills;

4. sense of competence in the parenting role;

5. parent interaction with child.

B. Child health and development outcomes including:

1. child cognitive development;

2. child interaction with parent.

C. Combined parent‐child relationship

1. any combined parent‐child interaction.

Within each generic category of outcome there are sub‐outcomes, which will also be included; for example, parental psychosocial health includes depression, anxiety and stress, and self‐esteem. Child health and development similarly covers a wide range of outcomes such as cognitive and language development, both of which may have further sub‐outcomes. Outcomes were measured using a range of standardised and validated parent‐report and objective assessment instruments (see 'Outcomes' below).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the following electronic databases:

MEDLINE (1950 to May 2010) searched 6 May 2010

MEDLINE (1966 to January 2008) searched 24 January 2008

EMBASE (1980 to current) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

CENTRAL (2010, Issue 2) searched 6 May 2010; (2008, Issue 10) searched 24 January 2008

DARE (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 4) searched 6 May 2010; DARE (The Cochrane Library 2008 Issue 1) searched 24 January 2008

CINAHL (1982 to May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

PsycINFO (1872 to May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

Social Science Citation Index (1956 to 6 May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

ASSIA (1980 to 6 May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

Sociological Abstracts (1963 to May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

ERIC (1966 to 6 May 2010) searched 6 May 2010 and 24 January 2008

UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database searched 6 May 2010

National Research Register 2005 (Issue 1)

The search strategies used at this update, for each database, can be found in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7: Appendix 8; Appendix 9. An RCT filter was not used to ensure that the search was as inclusive as possible, and no language or date restrictions were applied. The original searches were run in 2000. We repeated the searches in 2008 and 2010 with the exception of the National Research Register which had ceased to exist by the time of this update.

Search terms and the databases used in the previous published version of the review can be found in Appendix 10.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of articles identified through database searches were examined to identify further relevant studies. Bibliographies of systematic and non‐systematic review articles were also examined to identify relevant studies. We contacted trial investigators for further information where details of trial conditions or outcome data were needed. No additional handsearching was conducted but the results of handsearches carried out by all Cochrane review groups are added to CENTRAL.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the first published versions of the review, we reviewed titles and abstracts of studies identified through searches of electronic databases, to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Esther Coren (EC) identified titles and abstracts and EC and Jane Barlow (JB) read and reviewed these. Two independent review authors (EC and JB) assessed full copies of those papers which appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We resolved uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review by consultation with a third person (Sarah Stewart‐Brown). For the updated review produced in 2010, Nadja Smailagic (NS) and Nick Huband (NH) carried out the eligibility assessments in consultation with EC, JB and Cathy Bennett (CB). JB had overall responsibility for the inclusion or exclusion of studies in this review.

Data extraction and management

For the updated review, data were extracted independently by two reviewers (NS and NH) using a data extraction form and entered into Review Manager 5. Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted trial investigators to ask them to supply missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, two authors (NS and NH) independently completed the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2008, section 8.5.1) and disagreements were referred to a third review author (CB). We assessed the degree to which:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated (‘sequence generation’);

the allocation was adequately concealed (‘allocation concealment’);

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study (‘blinding’);

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting; and

the study was free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias.

Each domain was allocated one of three possible categories for each of the included studies: ‘Yes’ for low risk of bias, ‘No’ for high risk of bias, and ‘Unclear’ where the risk of bias was uncertain or unknown.

Measures of treatment effect

We present the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for individual outcomes in individual studies. The SMD was calculated by dividing the mean difference in post‐intervention scores between the intervention and control groups by the pooled standard deviation.

Unit of analysis issues

The randomisation of clusters can result in an overestimate of the precision of the results (with a higher risk of a Type I error) where their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. To address the effects of including cluster randomised trials in the meta‐analyses, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of clustering, using plausible values of ICC. None of the included studies involved cross‐over randomisation.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and drop‐outs for each included study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

An assessment was made of the extent to which there were between‐study differences including the extent to which there were variations in the population, intervention or outcomes. While thresholds for the interpretation of I2 can be misleading since the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors, I2 > 50% was treated as evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the importance of the observed value of I2 being dependent on the magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (for example, the P value from the chi‐squared test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2008). We assessed the extent to which there were between‐study differences including the extent to which there were variations in the population group and/or clinical intervention. We combined studies only if the between‐study differences were minor; in this update of the review we were able to combine studies that reported similar outcomes because the between‐study differences were few.

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we used meta‐analyses to combine comparable outcome measures across studies, using a fixed‐effects model. The weight given to each study in each meta‐analysis represents the inverse of the variance, such that the more precise estimates (i.e. from larger studies with more events), have been given more weight. Where there was evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity, we tested the robustness of the results using a random effects model.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The updated electronic searches in January 2008 produced 2,666 records. Two reviewers (NS and NH) independently examined the titles and abstracts. The majority of articles reviewed were written in English. We obtained a translation of one German study (Ziegenhain 2003) into English. All remaining studies in languages other than English had abstracts in English, and we excluded all these studies on the basis of information contained in the abstracts. We identified four new studies for inclusion. We updated the searches in May 2010 and this produced 1553 records. Two authors EC and NS, with CB, reviewed these search results. We consulted JB about any studies where there was uncertainty about whether the study met the inclusion criteria. No further studies were included following this search.

Included studies

Included studies

Four new studies (Wiemann 1990; Letourneau 2001; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) identified by the 2008 search were added to the four previously included studies (Truss 1977; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Lagges 1999). The eight included studies produced a total of 47 comparisons of outcomes from group‐based or individual parent training programmes versus a treatment as usual (TAU) condition or a no‐treatment control condition. These were derived from 63 individual study results (40 post‐intervention and 23 follow‐up). There were some important differences between the studies, and these have been summarised alongside the main study characteristics below (see Characteristics of included studies table and Table 1).

1. Outcomes and outcome measures in the included studies.

| Main outcome | Specific outcome | Aspect | Measurement instrument | Study | Timing of outcome assessment | Used in meta‐analysis |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes | Psychosocial health | Depressive symptoms | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden & Sagovsky 1987) Scale direction: lower score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: from mothers (self‐reported) Time of measurement: post‐intervention at 7 to 9 weeks of age, and at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Not used: Mean and SD not provided |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes | Psychosocial health | Depressive symptoms | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); cut‐off scores ranging from 12 to 16 have been found to discriminate adolescent as depressed or non‐depressed based on diagnostic criteria (Beck, Carlson, Russell & Brownfield, 1987) Scale direction: lower score better |

Stirtzinger 2002 | Obtained: from mothers by a trained research assistant (self‐administered questionnaire) Time of measurement: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at 6‐month follow‐up |

Post intervention Parent report measurement used: Analysis 1.1 Follow up data only reported for the intervention group Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes | Psychosocial health | Stress | The questionnaire generated four variables: INTP (Interpersonal stress) TANG (Tangible stress) INST (Institutional stress) STRES (Overall stress) Scale direction: n/a scale not validated |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data not used: the scale not validated Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

|

Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parenting knowledge | Knowledge of parenting skills | Parenting knowledge test (PFT) (Segal, 1995) Scale direction: higher score better |

Lagges 1999 | Obtained: from mothers (the questions were read aloud by the teachers) Time of measurement at baseline and at 8 weeks follow‐up |

Post intervention Post‐intervention assessment not performed Follow up Parent outcome measurement used: Analysis 2.1 Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parenting knowledge | General knowledge of child development | Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory (KIDI) (MacPhee 1981) 3 outcome measurements: SUMRT, SUMWRG, and SUMNS Direction of the scale: high scores are better |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview. Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention. |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data used: Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4 Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis: not used |

|

Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parenting behaviours | Play and discipline behaviours | The interview recalled scenarios (such as toys owned, discipline technique, physical punishment, and other) Not a validated scale Outcome measurements: TOYS, POS, PSNG, TECHN, NEG, PHYS |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers (self‐report) after interview/recalled scenario Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12 week follow up |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data not used: the scale not validated Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parenting behaviours | Feeding behaviours |

The questionnaire generating five variables: positive change in amount of junk food (J); appropriateness of solid food (Food); appropriateness of milk used (FM); % of appropriate child done eating cues used (GDCUE); % of inappropriate child done eating cues used (BDCUE) Not a validated scale |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data not used: the scale not validated Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parenting behaviours | Behaviour towards coping with stress | The questionnaire generating six variables: PPOS1, PNEGI, PPOS2, PNEG2, PPOS3, PNEG3 Not a validated scale |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data not used: the scale not validated Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

|

Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Maternal attitude towards mealtime communication | "About Your Child’s Eating" (AYCEQ) questionnaire (Davies et al,1993) Scale direction: higher score better |

Black 1997 | Obtained: from mothers Time of measurement: at baseline, and at post intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data: Analysis 3.1 Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Maternal attitude towards identity in parental role, SD‐Self | Neonatal Perception Inventory Scale (NPSIS) (Walker, 1982): Semantic differentials‐Myself as Mother (SD‐Self) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: from mothers Time of measurement: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Parent report measurement used: Analysis 3.3 Follow up Follow up outcome measurement used: Analysis 3.3 Meta analysis: not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Maternal attitude towards identity in parental role, SD‐Baby | Neonatal Perception Inventory Scale (NPIS) (Walker, 1982): Semantic differentials‐My Baby (SD‐Baby). Scale direction: higher score better. |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: from mothers Time of measurement: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Parent report measurement used: Analysis 3.4 Follow up Follow up outcome measurement used: Analysis 3.4 Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Self‐confidence in infant care | Pharis Self‐Confidence in Infant care (PS‐CS) Scale (Pharis, 1978) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 | Obtained: from mothers Time of measurement: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Parent report measurement used: Analysis 3.5 Follow up Follow up outcome measurement used: Analysis 3.5 Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Parenting attitudes towards belief in the value of adaptive parenting rather than coercive practice | Parental Attitude Questionnaire (PAQ) (No reference given) Scale direction: higher score better |

Lagges 1999 | Obtained: from mothers (the questions were read aloud by the teachers) Time of measurement: at baseline and at 8 weeks follow‐up |

Post intervention Post‐intervention assessment not performed Follow up Parent outcome measurement used: Analysis 3.2 Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Parenting attitudes towards childrearing in parental role | Adult‐Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI): four sub‐scale for passive learning (audio‐visual) and active learning Total score Appropriate developmental expectation of children Empathy toward children’s needs Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment Lack of reversal of parent‐child roles Scale direction: higher score better |

Ricks‐Saulsby 2001 | Obtained: from report by parents (questionnaire) Times of measurement: at baseline, and at post‐intervention |

Post intervention Parent report measurement for passive learning used: Analysis 3.10 (Total score); Analysis 3.11 (Appropriate developmental expectation of children); Analysis 3.12 (Empathy toward children’s needs); Analysis 3.13 (Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment); Analysis 3.14 (Lack of reversal of parent‐child roles). Parent report measurement for active learning used: Analysis 3.15 (Total score); Analysis 3.16 (Appropriate developmental expectation of children); Analysis 3.17 (Empathy toward children’s needs); Analysis 3.18 (Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment); Analysis 3.19 (Lack of parent child role reversal); Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Parenting attitudes towards childrearing in parental role | Adult‐Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI) with four sub‐scales (as described above) Scale direction: higher score better |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data used: Analysis 3.6 (Lack of reversal of parent‐child roles);

Analysis 3.7 (Appropriate developmental expectation of children); Analysis 3.8 (Empathy toward children’s needs); Analysis 3.9 (Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment).

Analysis 3.20 (Appropriate developmental expectation of children); Analysis 3.21 (Empathic awareness of child's needs) Analysis 3.22 (Lack of reversal of parent‐child roles); Analysis 3.23 (Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment). Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis Post‐intervention data used ('audiovisual only): Analysis 8.1(Appropriate developmental expectation of children) Analysis 8.2 (Empathy toward children’s needs); Analysis 8.3 (Non‐belief in the use of corporal punishment); Analysis 8.4 (Lack of parent child role reversal). |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Parenting attitudes towards the self, self‐esteem in parental role | Rosenberg Self‐Efficacy Scale (RSES) (Rosenberg, 1965): ROS1: self‐esteem ROS2: lack of self‐denigration Scale direction: higher score better |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data used: Analysis 3.24; Analysis 3.25 Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Sense of competence in parenting role | Parenting attitudes towards the self, self‐confidence in parental role | Parenting Self‐Confidence Scale (Myers‐Walls, 1979): TOTMW: parenting self‐confidence Not a validated scale |

Wiemann 1990 | Obtained: from adolescent mothers during the interview Time of measurement: at baseline, and at 12‐week post‐intervention |

Post intervention Post‐intervention data not used: the scale not validated Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes | Sense of competence in parenting role | Parental efficacy and control over potential causes of failure toward successful interaction with children: Adult Control over Failure and Child Control over Failure | Parent Attribution Test (PAT) (Bugental et al, 1989) Scale direction: higher 'Perceived Control over Failure' (PCF) score better |

Stirtzinger 2002 | Obtained: from mothers by a trained research assistant (self‐administered questionnaire) Time of measurement: at baseline, and at post‐intervention |

Not used: scores given were percentiles; Mean and SD for the baseline endpoint changes not reported |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes | Sense of competence in parenting role | Parental attribution for misdeeds | Parent’s attributions for misdeeds (Dix et al, 1986) Scale direction: higher scores indicate more negative emotions |

Stirtzinger 2002 | Obtained: from mothers by a trained research assistant (self‐administered questionnaire) Time of measurement: at baseline, and at post‐intervention |

Not used: scores given were percentiles; Mean and SD for the baseline endpoint changes not reported |

|

Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parent interaction with child | Maternal behaviour ‐ maternal mealtime communication | A modified version (unpublished document) of the Parent Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA) (Clark et al 1990) Scale direction: higher score better |

Black 1997 | Obtained: by assessors who videotaped mother‐infant feeding. Assessed: at baseline, and at post intervention |

Post intervention Parent report measurement used: Analysis 4.1 Follow up Follow up assessment not performed Meta analysis: not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parent interaction with child | Maternal behavior ‐ Mother’s sub‐scale (sensitivity to cues, response to distress, social‐emotional growth fostering activity, and cognitive growth fostering activity) | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Mother's sub‐scale (Bernard, 1978) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: observed and videotaped by specifically trained professional nurse Assessed: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up. |

Post intervention

Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 4.2 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 4.2 Meta analysis Both time points Analysis 9.1; Analysis 9.2 (fixed‐ and random‐effects models) |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parent interaction with child | Maternal behavior ‐ Cognitive growth fostering sub‐scale | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Mother's Fostering Growth Cognitive Subscale (Bernard, 1978) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: observed and videotaped by specifically trained professional nurse Assessed: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 4.3 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 4.3 Meta analysis: not used |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parent interaction with child | Parent outcome ‐ parent responsiveness to the interaction | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Parent sub‐scale) (Sumner & Spietz, 1994b) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: at 7 to 9, and 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome used: Analysis Analysis 4.5 Follow up Observer outcome used: Analysis 4.5 Meta analysis Both time points used: Analysis 9.1; Analysis 9.2 (fixed and random effects) |

| Parental psychosocial outcomes |

Parent interaction with child | Parent outcome ‐ parent responsiveness to the interaction | Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) (Parent sub‐scale) (Sumner & Spietz, 1994a) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: post‐intervention at 7 to 9 weeks of age, and at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis Analysis 4.4 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 4.4 Meta analysis not used |

|

Child health and development outcomes |

Cognitive development | Infant cognitive and language development | Bzoch‐League Receptive‐Expressive Emergent Language (REEL) scale: Receptive Language Score (Bzoch & League, 1971) Scale direction: higher score better |

Truss 1977 | How obtained: not reported (independent observer) Time of measurement: when children were 1 year old, and 2 years old |

Post intervention Post intervention assessment not performed Follow up outcomes used: Analysis 5.1 Meta analysis not used |

| Child health and development outcomes |

Cognitive development | Infant cognitive and language development | Bzoch‐League Receptive‐Expressive Emergent Language (REEL) scale: Expressive language score (Bzoch & League, 1971) Scale direction: higher score better |

Truss 1977 | How obtained: not reported (independent observer) Time of measurement: when children were 1 year old, and 2 years old |

Post intervention Post intervention assessment not performed Follow upAnalysis 5.2 Meta analysis not used |

| Child health and development outcomes |

Cognitive development | Infant cognitive and language development | Utah Test of Language (UTL) Development: Expressive scale (Mecham, Jey & Jones, 1967) Scale direction: higher score better |

Truss 1977 | How obtained: not reported (independent observer). Time of measurement: follow‐up data reported only when children 2 years old |

Post intervention Post intervention assessment not performed Follow upAnalysis 5.3 Meta analysis not used |

| Child health and development outcomes | Cognitive development | Infant expectations | Visual Expectation Paradigm Test (VEXP)‐modified for this trial (Haith Hazan & Goodman 1998) Note: The modified VEXP scale had not been independently validated |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: at 11 to 13 weeks follow up |

Not used: the scale was not validated |

| Child health and development outcomes | Cognitive development | Infant cognitive and developmental functioning | Bayley scales of infant development II: mental development index (MDI) provided cognitive development quotient scores (DQ) (Bayley 1993) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: at 11 to 13 weeks follow up |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement not performed Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 5.4 Meta analysis not used |

|

Child health and development outcomes |

Child interaction with parent |

Infant responsiveness to mother‐baby interaction: Baby’s sub‐scale (clarity and responsiveness to cues) | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Baby's sub‐scale (Bernard 1978) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: observed and videotaped by specifically trained professional nurse Assessed: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 6.1 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 6.1 Meta‐analysis Follow up data used: Analysis 10.1 |

| Child health and development outcomes |

Child interaction with parent |

Infant responsiveness to parent sub‐scale | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Infant ‐ Responsiveness to parent sub‐scale (Bernard 1978) Scale direction: higher score better |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: observed and videotaped by specifically trained professional nurse Assessed: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 6.2 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 6.2 Meta‐analysis not used |

| Child health and development outcomes |

Child interaction with parent | Child outcome ‐ child responsiveness to the interaction | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Child sub‐scale (Sumner & Spietz 1994b) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: at 7 to 9 weeks of age, at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement not reported Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 6.3 Meta‐analysis used: Analysis 10.1 |

|

Combined parent/child relationship |

Combined parent‐child interaction | Combined parent and child interactions | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS)Total score |

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 |

Obtained: observed and videotaped by specifically trained professional nurse Assessed: at baseline, at post‐intervention, and at two months postpartum follow‐up |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.1 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.1 Meta‐analysis Both time points used: Analysis 11.1 |

| Combined parent/child relationship |

Combined parent‐child interaction | Combined parent and child interactions | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS)Total score | Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: post‐intervention at 7‐9 weeks of age, and at 11‐13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.2 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.2 Meta analysis Both time points used: Analysis 11.1 |

| Parent/child relationship |

Combined parent‐child interaction | Combined parent and child/parent interactions | Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) Total score (Sumner & Spietz, 1994a) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: post‐intervention at 7 to 9 weeks of age, and at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.3 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.3 Meta analysis not used |

| Combined parent/child relationship |

Combined parent‐child interaction | Contingency score ‐ the degree of contingent responsiveness in the interaction | Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) Contingency sub‐scale (Sumner & Spietz, 1994b) Scale direction: higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Times of measurement: post‐intervention at 7 to 9 weeks of age, and at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.4 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.4 Meta analysis not used |

| Combined parent/child relationship |

Combined parent‐child interaction | Contingency score ‐ the degree of prompt, sensitive maternal response to signals from the child | Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) Contingency sub‐scale) (Sumner & Spietz, 1994a) Scale direction: Higher score better |

Letourneau 2001 | Obtained: by the study assessors (observational measure) Time of measurement: post‐intervention at 7 to 9 weeks of age, and at 11 to 13 weeks of age (but not at baseline) |

Post intervention Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.5 Follow up Observer outcome measurement used: Analysis 7.5 Meta analysis not used |

The full references to each scale given in this table appear in the bibliographies of the included studies and are not supplied in this review.

Design

All eight included studies were randomised controlled trials.

Cluster randomised studies

Two studies comprised cluster randomised controlled trials (Wiemann 1990; Lagges 1999). Lagges 1999 used classes of GRADS students as the unit of allocation, but Wiemann 1990 did not provide any information about the what unit (i.e. cluster) was used for the purpose of randomisation. The randomisation of clusters can result in an overestimate of the precision of the results (with a higher risk of a Type I error) where their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. Neither of the above studies provided information to indicate whether the 'design effect' was adjusted for in the analysis, and their results have therefore been treated with caution (Wiemann 1990).

Number of study centres

Five studies were single‐centre trials (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Letourneau 2001; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002). One study did not provide sufficient information to be classified (Truss 1977). The remaining two studies were multicentre (Wiemann 1990; Lagges 1999).

Treatment and control groups

The majority of studies were two‐condition comparisons of individual or group‐based teenage parenting programmes compared with a control group (Truss 1977; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Lagges 1999; Letourneau 2001; Stirtzinger 2002), although two studies utilised more than one intervention group (Wiemann 1990; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001). Five studies used a no‐treatment control group (Truss 1977; Wiemann 1990; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001). Three studies (Lagges 1999; Letourneau 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) used a treatment‐as‐usual control group.

Sample sizes

None of the included studies provided details regarding the sample size calculations or information about the size of the changes that the study was powered to detect. One large multi‐centre trial (Truss 1977) randomised 164 participants. The remaining seven studies involved fewer than 90 participants with sample sizes ranging from 20 to 88. Overall, the number of participants (primary carer‐index child pair) initially randomised was 513, and ranged from 20 to 164.

In total, the eight studies included 351 participants in their analyses, with a range from 16 to 95 participants.

Location

Two studies were conducted in Canada (Letourneau 2001; Stirtzinger 2002); the remaining six studies were conducted in the USA.

Setting

Two studies recruited participants from outpatient settings on the basis of age (Truss 1977; Letourneau 2001). Four studies (Black 1997; Lagges 1999; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) recruited participants from community settings. Wiemann 1990 recruited from a range of settings (community and outpatients), while Koniak‐Griffin 1992 recruited participants from a residential maternity home.

Delivery of Intervention

Four studies (Black 1997; Lagges 1999; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) delivered the intervention in community settings, while Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001 delivered the programme in the participants' homes. Wiemann 1990 delivered the intervention in both community and outpatient settings. One study (Truss 1977) failed to specify the intervention site.

Participants

Participants comprised primary carer‐index child pairs. All the studies targeted primary carers below the age of 20, who were adolescent mothers or were pregnant. The age range was 13 to 20 years. The mean age was 17 years in seven studies. One study (Truss 1977) did not report the mean age of mothers. Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of interventions with teenage parents of infants (Truss 1977; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Letourneau 2001), and the remaining four studies included teenage parents of young children (ages unspecified) (Wiemann 1990; Lagges 1999; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002). One study recruited only first‐time African‐American women less than 20 years of age (Black 1997).

The studies included in this review were largely directed at teenage mothers alone. While one study included two adolescent fathers, their results were excluded from the analysis (Lagges 1999).

Interventions

Three of the included studies evaluated the effectiveness of standard group‐based parenting programmes delivered over the course of between six to 10 weeks (Truss 1977; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002). Three of the included studies evaluated the effectiveness of much briefer interventions that mostly comprised observation of videotape interactions over a brief period (i.e. one to two sessions) (Black 1997; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Lagges 1999) or more extended period (i.e. six to seven weeks) (Wiemann 1990), and that focused primarily on improving parent‐infant interaction.

Outcomes

The included studies used a range of instruments to measure outcomes, using a wide range of scales, and sub‐scales. Many of these could not be combined because they were not measuring sufficiently similar underlying conditions. For example, although depression and self‐esteem are both aspects of psychosocial well‐being, we did not consider that it was appropriate to combine them (see Table 1).

Primary outcomes

We provide an overview of the outcomes and the instruments used to measure them in Table 1.

A) Parental psychosocial

All eight included studies reported parental psychosocial outcomes. Two studies (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001) measured the impact of a parenting programme on parent interaction with the child (parent sub‐scales) (see Table 1).

B) Child health and development

Three studies (Truss 1977; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001) measured child health and development (Table 1) and two studies (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001) measured the child's interaction with the parent (child sub‐scales).

C) Combined parent‐child relationship

Two studies (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001) measured overall parent‐child interaction (total scores measuring combined parent and child interactions) (see Table 1).

Time points

Five studies provided an assessment of outcome immediately post‐intervention (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Letourneau 2001; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002), and one of these studies also provided follow‐up data (Black 1997). Three studies provided assessment at follow‐up only (i.e. no assessment of outcome was made immediately post‐intervention) (Truss 1977; Wiemann 1990; Lagges 1999).

Excluded studies

In the previous published version of the review, we excluded 19 studies. Following the updated searches in 2008 (2666 records), we obtained 40 full text copies, and we excluded 36. We discarded eleven of these 36 of these as irrelevant; 22 of these 36 appear in the excluded studies table (Badger 1974; Robertson 1978; Brady 1987; Greenberg 1988; Evangelisti 1989; Donovan 1994; Bamba 2001; Black 2001; Ford 2001; Letourneau 2001a; Stevens‐Simon 2001; Barnet 2002; Mazza 2002; Nguyen 2003; Quinlivan 2003; Ziegenhain 2003; Thomas 2004; Logsdon 2005; Barlow 2006; Deutscher 2006; Malone 2006; McDonell 2007). In the updated searches, we identified three studies (Field 1980; Westney 1988; Butler 1993) of 36 that also appeared in the excluded studies list of the previously published version of this review. We re‐examined them and again excluded these three studies.

From the searches in May 2010, we excluded seven studies (Fagan 2008; Gurdin 2008; Aracena 2009; Barnet 2009; Oswalt 2009; Walkup 2009; Meglio 2010). Forty‐eight studies that did not fit one or more of the inclusion criteria are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We did not exclude any study solely on the basis of the outcomes reported or the absence of standardised measures. The Characteristics of excluded studies table summarises all the reasons given for exclusion. However, five studies, in addition to other reasons for exclusion, did not assess relevant outcomes or used non‐standardised outcome measures (Robertson 1978; Westney 1988; Letourneau 2001a; Mazza 2002; Meglio 2010).

Of the 48 excluded studies, 20 were not randomised or the allocation method was unclear (with no further details available from the trial investigator) (Badger 1974; Robertson 1978; Roosa 1983; Roosa 1984; Brady 1987; Greenberg 1988; Evangelisti 1989; Fulton 1991; Dickenson 1992; Kissman 1992; Weinman 1992; Butler 1993; Donovan 1994; Emmons 1994; Cook 1995; Treichel 1995; Britner 1997; Thomas 2004; Deutscher 2006; Malone 2006). A further eleven were excluded because the control group did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e. it was not a waiting‐list, no‐treatment or treatment‐as‐usual/normal service provision group) (Badger 1981; Field 1982; Brophy 1997; Black 2001; Letourneau 2001a; Stevens‐Simon 2001; Mazza 2002; Nguyen 2003; Logsdon 2005; Fagan 2008; Walkup 2009). We excluded six studies because they had a home visiting component (Aracena 2009; Barnet 2009; Field 1980; Donovan 1994; Koniak‐Griffin 1999; Wagner 1999). One (Ford 2001) focused on ante‐natal care only and another (Westney 1988) was delivered to adolescent fathers in the ante‐natal period only. Two studies (Bamba 2001; Ziegenhain 2003) were not aimed specifically at adolescent parents. Meglio 2010 focused on breastfeeding duration. The remaining six studies were not brief, structured parenting programmes, or addressed other outcomes such as healthcare and social support (Porter 1984; Quinlivan 2003; Barlow 2006; McDonell 2007; Gurdin 2008; Oswalt 2009).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias for the eight included studies (see Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1). Each risk of bias table provides a decision about the adequacy of the study in relation to the entry criterion, such that a judgement of ‘Yes’ indicates low risk of bias, ‘No’ indicates high risk of bias, and ‘Unclear’ indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias (Higgins 2008).

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Only one study described the method of sequence generation (Ricks‐Saulsby 2001). The principal investigator for Lagges 1999 confirmed that a random number table was used to assign the school classes to the study conditions. Only one study (Letourneau 2001) described the method of concealing allocation to study groups.

Blinding

No study adequately blinded participants and personnel because it is not possible to fully blind either participants or personnel in this type of study. This constitutes a source of potential bias. Only two studies blinded assessors for all outcomes (Wiemann 1990; Black 1997). Two studies blinded assessors to some outcomes only (Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Letourneau 2001). The four remaining studies did not report on blinding of assessors (Truss 1977; Lagges 1999; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

One study provided information concerning the reason for incomplete data (Black 1997). Koniak‐Griffin 1992 collected study data on all participants at each time point and none of the participating families dropped out. Wiemann 1990 did not provide sufficient information to make a judgement. Outcome data was incompletely reported in the five remaining studies (Truss 1977; Lagges 1999; Letourneau 2001; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) raising the possibility of a risk of bias. None of the included studies reported intention‐to‐treat analyses.

Selective reporting

We did not identify any indications of bias due to selective reporting in the eight included studies.

Other potential sources of bias

While the use of randomisation should in theory ensure that any possible confounders are equally distributed between the arms of the trial, the randomisation of small numbers may result in an unequal distribution of confounding factors. It is therefore important that the distribution of known potential confounders is either (i) compared between the different study groups at the outset, or (ii) adjusted for at the analysis stage.

Six studies provide information about the distribution of potential confounders (Wiemann 1990; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Black 1997; Lagges 1999; Letourneau 2001; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) by reporting differences between the intervention and control groups at the start of the study. Only Koniak‐Griffin 1992 reported that there were significant differences between the groups (in terms of racial/ethnic variations) and trial investigators explored the implications for this in the study report. We were not able to make a judgment as to whether four studies were free of other sources of potential bias (Truss 1977; Wiemann 1990; Lagges 1999Letourneau 2001), but judged that three studies (Black 1997; Ricks‐Saulsby 2001; Stirtzinger 2002) were free of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

The included studies reported data that had been collected using a range of outcome instruments. We were unable to combine much of the reported data using meta‐analysis because of the following: i) a wide range of divergent outcomes were measured; ii) the outcomes were not measured at comparable time points; iii) assessments were reported for the same group of participants using a number of subscales (i.e. which would have led to double counting of the participants).

The results presented in the Data and analyses tables comprise individual study results and the nine meta‐analyses that were possible.

Table 1 provides full details of the individual outcomes reported in each of the included studies, and the results of the meta‐analyses. This table also lists the outcome measures that we combined using meta‐analysis and directs the reader to the relevant analysis. Table 1 also provides additional information about the time‐point at which measurement was undertaken, and the direction of the scales used (i.e. whether a high score represents improvement or deterioration).

A narrative summary is provided below of the individual study results for each primary outcome and the results of the meta‐analyses.

Individual study results ‐ parent training versus control

The eight included studies provided data on a total of 47 comparisons of outcome between intervention and control conditions. Nineteen of these comparisons were statistically significant, either at post‐intervention or follow‐up, each favouring the intervention. These are organised by outcome and by time point in Analyses 1 to 7.

Meta‐analyses ‐ parent training versus control

We were able to carry out meta‐analyses of parent‐training versus control for four outcomes:

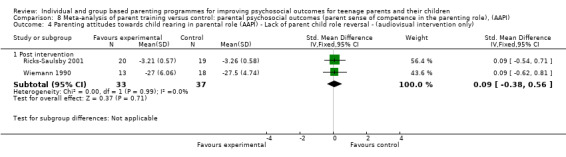

1. Parent psychosocial outcomes ‐ sense of competence in parental role;

2. Parent psychosocial outcomes ‐ parent interaction with child;

3. Child health and development outcomes ‐ child interaction with parent;

4. Combined parent‐child relationship ‐ any combined parent‐child interaction.

The results presented below are organised by outcome and measurement time‐point (Analyses 8 to 11). The results are presented as effect‐sizes with 95% confidence intervals. A minus sign indicates that the result favours the intervention group. We used post‐intervention scores and follow‐up scores to calculate effect sizes rather than change scores (i.e. pre‐ to post‐scores for each group). This reflects the fact that a change standard deviation is required to calculate change scores, and these data were not available for any of the included studies.

We combined data for three outcomes assessing different aspects of parent‐infant interaction (for example, parent responsiveness; infant responsiveness; combined interaction) derived from two studies, producing a total of five meta‐analyses. We also combined data from two further studies assessing parenting competence in four meta‐analyses, producing nine meta‐analyses in total. Four of five meta‐analyses using data from the two studies Koniak‐Griffin 1992 and Letourneau 2001 produced statistically significant findings favouring the intervention for the following: parent responsiveness to the child post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.91; 95% CI ‐1.52 to ‐0.30; P=0.04; Analysis 9.1); infant responsiveness to mother at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.65; 95% CI ‐1.25 to ‐0.06; P=0.03; Analysis 10.1); and overall parent‐child interaction both post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.71; 95% CI ‐1.31 to ‐0.11; P=0.02; Analysis 11.1) and at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.90; 95% CI ‐1.51 to ‐0.30; P = 0.004; Analysis 11.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Meta‐analysis of parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child) (NCATS), Outcome 1 Maternal interactions, parent child teaching interaction (NCATS) ‐ Parent subscale.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Meta‐analysis of parent training versus control: child health and development outcomes, (child interaction with parent) (NCATS ‐ Baby's subscale), Outcome 1 Child/Parent Interaction ‐ Infant responsiveness to mother ‐ NCATS (Baby's subscale).

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Meta‐analysis Parent training versus control: combined parent‐child relationship (combined parent‐child interaction) (NCATS), Outcome 1 Parent ‐ child relationship (parent‐child teaching interaction, (NCATS) ‐ Total score).

The fifth meta‐analysis using data from Koniak‐Griffin 1992 and Letourneau 2001 produced statistically significant findings favouring the intervention for parent responsiveness to the child at follow‐up when a fixed effect model was used; however, there was significant hetereogeneity and the confidence interval we found when using a random‐effects model (SMD ‐6.11; 95% CI ‐16.99 to 4.77; P=0.27; Analysis 9.2) did not allow us to conclude whether or not the intervention has an effect on parent responsiveness to the child at follow‐up.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Meta‐analysis of parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child) (NCATS), Outcome 2 Follow up (random effects model).

The four meta‐analyses of parenting competence using data from two further studies Wiemann 1990 and Ricks‐Saulsby 2001 were also inconclusive.

Individual study results

Parental psychosocial outcomes

Analysis 1: Parental psychosocial health ‐ depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory)

One study (Stirtzinger 2002) found non‐significant results for depressive symptoms post‐intervention, measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI‐Depressive symptoms scale) Analysis 1.1. No follow‐up data for this outcome was available.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (psychosocial health), Outcome 1 Depressive symptoms (BDI).

Analysis 2: Parenting knowledge (various scales)

Lagges 1999 did not report post‐intervention results, but reported one statistically significant result for the Parenting Knowledge Test (PKT parent‐report) (SMD ‐0.95; 95% CI ‐1.54 to ‐0.36; Analysis 2.1) at follow‐up. To assess the impact of clustering in this study, we estimated that an Intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) of 0.355 would be required to eliminate the significant finding obtained, and we therefore concluded that the above result is robust to clustering effects.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parenting skills, various scales), Outcome 1 Knowledge of parenting skills (PKT).

Wiemann 1990 reported no statistically significant results for any of the subscales of the KIDI post‐intervention (Analysis 2.2;Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). We were unable to conduct any meta‐analyses because the outcome measurements were made at different time points in the two studies.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parenting skills, various scales), Outcome 2 General knowledge of general child development (KIDI) ‐ total number correctly answered items (combined intervention).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parenting skills, various scales), Outcome 3 General knowledge of general child development (KIDI) ‐ total number of incorrectly answered items (combined intervention).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parenting skills, various scales), Outcome 4 General knowledge of general child development (KIDI) ‐ total number of 'not sure' answered items (combined intervention).

Parenting behaviours and skills

No studies used validated outcome scales to measure parenting behaviour or skills (see Table 1).

Analysis 3: Sense of competence in the parenting role (various scales)

Black 1997 reported a statistically significant result post‐intervention favouring the intervention group for maternal attitude towards mealtime communication (parent report from the "About your child's eating questionnaire", AYCEQ) (SMD ‐1.28; 95% CI ‐1.84 to ‐0.71; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 1 Maternal attitude toward mealtime communication ‐ (AYCEQ).

Lagges 1999 found no statistically significant results at follow‐up for parenting attitudes towards adaptive parenting as opposed to coercive parenting practices (Analysis 3.2) using the Parental Attitude Questionnaire (PAQ).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 2 Parenting attitude towards belief in the value of adaptive rather than coercive practice (PAQ).

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 reported statistically significant results favouring the intervention group for the Neonatal Perception Inventory Scale (NPIS), semantic differential sub‐scale (SDM‐Myself as Mother ‐ parent report), at follow‐up only (SMD ‐0.81; 95% CI ‐1.55 to ‐0.08; Analysis 3.3). There were also significant results for the NPIS SDM‐My Baby (parent report) post‐intervention for the subscale SDM‐My Baby (mother‐report) (SMD ‐0.80 95% CI ‐1.53 to ‐0.06; Analysis 3.4.1), and at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.78; 95% CI ‐1.51 to ‐0.04; Analysis 3.4.2).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 3 Maternal attitude toward identity in parental role (NPIS) ‐ Semantic Differential Measure ‐ Myself as Mother (SD‐Self).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 4 Maternal attitude toward identity in parental role (NPIS) ‐ Semantic Differential Measure ‐ My Baby (SD‐Baby).

Non‐significant results at both time points were reported for self‐confidence in infant care, measured by the 'Pharis Self‐Confidence Scale' (PS‐CS) ‐ mother report (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 5 Self‐confidence in infant care (PS‐CS).

Wiemann 1990 found a significant result favouring the intervention group for empathic awareness towards children's needs (video only) measured using the Adult‐Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI) post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.74; 95% CI ‐1.48 to ‐0.00; Analysis 3.8). We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the influence of clustering using plausible values of ICC (i.e. an ICC from a similar study was not available). Based on possible cluster size at randomisation and the drop‐out pattern, the ICC would have had to be between 0.015 and 0.025 (Design Effect 1.06) to overturn the statistical significance. The effect of clustering on the width of the confidence interval would be small because the size of the clusters is small, and we have therefore concluded that this result is reliable.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 8 Parenting attitudes towards child rearing in parental role (AAPI) ‐ Empathic awareness towards children's needs ‐ (audiovisual only).

Ricks‐Saulsby 2001 reported ten outcome measurements from the AAPI scale (parent report), five from active learning (demonstration and practice of parenting skills) versus control, and five from passive learning (audiovisual only) versus control. Only one outcome measurement from the active learning versus control comparison showed significant results favouring the intervention group post‐intervention: AAPI‐Lack of parent child role reversal (SMD ‐1.03; 95% CI ‐1.71 to ‐0.34; Analysis 3.19).

3.19. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 19 Parenting attitudes towards child rearing in parental role (AAPI) ‐ Lack of parent child role reversal ‐ active learning.

Two outcome measurements from passive learning versus control comparisons indicated significant results favouring the control group: AAPI‐Appropriate developmental expectations of children (at post‐intervention: SMD 0.73; 95% CI 0.08 to 1.38; Analysis 3.11); and AAPI‐Empathic awareness towards children’s needs (at post‐intervention: SMD 0.77; 95% CI 0.11 to 1.43; Analysis 3.12).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 11 Parenting attitudes towards child rearing in parental role (AAPI) ‐ Appropriate developmental expectation of children ‐ passive learning (audiovisual only).

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent sense of competence in the parenting role, various scales), Outcome 12 Parenting attitudes towards child rearing in parental role (AAPI) ‐ Empathic awareness towards children's needs ‐ passive learning (audiovisual only).

The remaining outcomes from Ricks‐Saulsby 2001 showed non‐significant results.

Analysis 4: Parent interaction with child (various scales)

Black 1997 reported a significant result post‐intervention favouring the intervention group for maternal mealtime communication using the modified 'Parent Child Early Relational Assessment' (PCERA) (independent report) (SMD ‐0.54; 95% CI ‐1.07 to ‐0.02; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child, various scales), Outcome 1 Maternal interactions, mealtime communication (independent data) ‐ (PCERA) (modified).

Koniak‐Griffin 1992 reported three significant results favouring the intervention group, for the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS), two of these being for the NCATS‐Mother’s sub‐scale (independent report) at post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.98; 95% CI ‐1.73, ‐0.23; Analysis 4.2.1) and follow‐up (SMD ‐0.82; 95% CI ‐1.56 to ‐0.08; Analysis 4.2.2); and the NCATS‐Cognitive Growth Fostering Subscale (independent report) at post intervention (SMD ‐0.93; 95% CI ‐1.67 to ‐0.18; Analysis 4.3).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child, various scales), Outcome 2 Maternal interactions, parent child teaching interaction (NCATS) ‐ Mother's subscale (independent data).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child, various scales), Outcome 3 Maternal interactions, parent child teaching interaction (NCATS) Mother's Cognitive Growth Fostering subscale (independent data).

Letourneau 2001 reported significant results favouring the intervention group for the NCAFS‐Parent sub‐scale (independent report), both post‐intervention (SMD ‐1.13; 95% CI ‐2.24, to ‐0.01; Analysis 4.4.1), and at follow‐up (SMD ‐1.82; 95% CI ‐3.04 to ‐0.60; Analysis 4.4.2).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child, various scales), Outcome 4 Maternal interactions, parent child feeding interaction (NCAFS) ‐ Parent subscale (independent data).

No other results were significant for the parent‐child interaction outcomes reported by Letourneau 2001 using the NCATS‐Parent sub‐scale (Analysis 4.5), but we conducted a meta‐analysis for this outcome (parent responsiveness to child) because data were available for the NCATS‐Parent sub‐scale from Koniak‐Griffin 1992 and Letourneau 2001 (see Meta‐analyses below).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Parent training versus control: parental psychosocial outcomes (parent interaction with child, various scales), Outcome 5 Maternal interactions, parent child teaching interaction (NCATS) ‐ Parent subscale (independent data).

Child health and development outcomes

Analysis 5: Cognitive development (various scales)

Truss 1977 found a significant result post‐intervention favouring the intervention group for language development measured using the Bzoch‐League Receptive‐Expressive Emergent Language scale (REEL) (SMD ‐0.73; 95% CI ‐1.31 to ‐0.06; Analysis 5.2.2), but there was no significant difference using the Utah test of Language development (*SMD ‐0.2; 95% CI ‐0.91 to 0.5; Analysis 5.3.1). The results for the REEL Receptive Language score were non‐significant at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.24; 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.37; Analysis 5.1.2). Letourneau 2001 reported non‐significant results for infant mental development at follow‐up using the Bayley Mental Development Index (MDI) (SMD ‐0.95; 95% CI ‐2.04 to 0.14; Analysis 5.4).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Parent training versus control: child health and development outcomes (cognitive development, various scales), Outcome 2 Infant cognitive and language development Bzoch‐League REEL (Expressive Language Score).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Parent training versus control: child health and development outcomes (cognitive development, various scales), Outcome 3 Infant cognitive and language development UTLD.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Parent training versus control: child health and development outcomes (cognitive development, various scales), Outcome 4 Infant cognitive and developmental functioning (Bayley MDI).

Analysis 6: Child interaction with parent (various scales)