Abstract

Background

Anti‐leukotrienes (5‐lipoxygenase inhibitors and leukotriene receptors antagonists) serve as alternative monotherapy to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in the management of recurrent and/or chronic asthma in adults and children.

Objectives

To determine the safety and efficacy of anti‐leukotrienes compared to inhaled corticosteroids as monotherapy in adults and children with asthma and to provide better insight into the influence of patient and treatment characteristics on the magnitude of effects.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (1966 to Dec 2010), EMBASE (1980 to Dec 2010), CINAHL (1982 to Dec 2010), the Cochrane Airways Group trials register, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Dec 2010), abstract books, and reference lists of review articles and trials. We contacted colleagues and the international headquarters of anti‐leukotrienes producers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials that compared anti‐leukotrienes with inhaled corticosteroids as monotherapy for a minimum period of four weeks in patients with asthma aged two years and older.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of trials and extracted data. The primary outcome was the number of patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids. Secondary outcomes included patients with at least one exacerbation requiring hospital admission, lung function tests, indices of chronic asthma control, adverse effects, withdrawal rates and biological inflammatory markers.

Main results

Sixty‐five trials met the inclusion criteria for this review. Fifty‐six trials (19 paediatric trials) contributed data (representing total of 10,005 adults and 3,333 children); 21 trials were of high methodological quality; 44 were published in full‐text. All trials pertained to patients with mild or moderate persistent asthma. Trial durations varied from four to 52 weeks. The median dose of inhaled corticosteroids was quite homogeneous at 200 µg/day of microfine hydrofluoroalkane‐propelled beclomethasone or equivalent (HFA‐BDP eq). Patients treated with anti‐leukotrienes were more likely to suffer an exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids (N = 6077 participants; risk ratio (RR) 1.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17, 1.96). For every 28 (95% CI 15 to 82) patients treated with anti‐leukotrienes instead of inhaled corticosteroids, there was one additional patient with an exacerbation requiring rescue systemic corticosteroids. The magnitude of effect was significantly greater in patients with moderate compared with those with mild airway obstruction (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.41, 2.91 versus RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.97, 1.61), but was not significantly influenced by age group (children representing 23% of the weight versus adults), anti‐leukotriene used, duration of intervention, methodological quality, and funding source. Significant group differences favouring inhaled corticosteroids were noted in most secondary outcomes including patients with at least one exacerbation requiring hospital admission (N = 2715 participants; RR 3.33; 95% CI 1.02 to 10.94), the change from baseline FEV1 (N = 7128 participants; mean group difference (MD) 110 mL, 95% CI 140 to 80) as well as other lung function parameters, asthma symptoms, nocturnal awakenings, rescue medication use, symptom‐free days, the quality of life, parents' and physicians' satisfaction. Anti‐leukotriene therapy was associated with increased risk of withdrawals due to poor asthma control (N = 7669 participants; RR 2.56; 95% CI 2.01 to 3.27). For every thirty one (95% CI 22 to 47) patients treated with anti‐leukotrienes instead of inhaled corticosteroids, there was one additional withdrawal due to poor control. Risk of side effects was not significantly different between both groups.

Authors' conclusions

As monotherapy, inhaled corticosteroids display superior efficacy to anti‐leukotrienes in adults and children with persistent asthma; the superiority is particularly marked in patients with moderate airway obstruction. On the basis of efficacy, the results support the current guidelines' recommendation that inhaled corticosteroids remain the preferred monotherapy.

Plain language summary

Anti‐leukotriene agents compared to inhaled corticosteroids for people with asthma

In an asthma attack, the airways (passages to the lungs) narrow because of muscle spasms (bronchospasm), inflammation (swelling) and mucus secretion phlegm. The airway passage narrowing results in breathing problems, wheezing and coughing. Inhaled corticosteroids are considered the gold standard to reduce the airway inflammation in adults and children with asthma. Anti‐leukotrienes (5‐lipoxygenase inhibitors and leukotriene receptors antagonists) are anti‐inflammatory drugs that may have fewer adverse effects than inhaled corticosteroids. The review suggests that anti‐leukotrienes are safe, but less effective than a low dose of inhaled corticosteroids.

Background

Asthma is a condition that affects the airways, it is characterised by bronchoconstriction and underlying inflammation. Infiltration of bronchial airways with eosinophils and neutrophils with release of inflammatory mediators is characteristic of asthma (Murphy 1993). The cysteinyl leukotrienes are considered as the most potent inflammatory mediators in asthma. They are produced by the 5‐lipoxygenase pathway of the arachidonic acid metabolism. These mediators stimulate the production of airway secretions, cause micro vascular leakage and enhance eosinophilic migration in the airways; thus, leukotrienes are believed to play a pivotal role in mediating bronchoconstriction and inflammatory changes in the pathophysiology of asthma (Peters‐Golden 2007).

All recent consensus statements on asthma advocate aggressive treatment of airway inflammation (Australia 2006; NAEPP 2007; Lougheed 2010; GINA 2010; BTS 2011). Although several drugs such as ketotifen, sodium cromoglycate and sodium nedocromil have anti‐inflammatory properties, inhaled glucocorticoids remain the cornerstone of asthma management because of their efficacy, tolerability and rapid onset of action (Spahn 1996). Prolonged low dose administration of inhaled corticosteroids is generally considered safe, although there is considerable concern about the long‐term effects of steroids among some consumers (Elwyn 2010). However, when moderate or high doses are required to control symptoms, adverse effects such as growth stunting in children (Sharek 2000; Richard 2006), suppression of the adrenal axis (Bisgaard 1988; Phillip 1992; Padfield 1993; Zöllner 2007), and osteopenia (Todd 1996; Heuck 1997) may be observed.

Anti‐leukotrienes form a class of anti‐inflammatory drugs that interfere with leukotriene production (5‐lipoxygenase inhibitors) or with leukotriene receptors (leukotriene receptors antagonists, LTRAs). Anti‐leukotrienes have the advantage of being administered orally in a single or twice daily dose and importantly, seem to lack the adverse effects on growth, bone mineralization and adrenal axis, associated with long‐term or high‐dose systemic glucocorticoid therapy.

Why it is important to do this review

The previous version of this review (Ducharme 2004) summarised the accumulating evidence derived from 25 randomised controlled trials (three paediatric and 22 adult) and concluded that low doses of inhaled corticosteroids were superior in efficacy than anti‐leukotrienes. With the publications of several new randomised controlled trials especially in children, an update of the systematic review was deemed useful to review the safety and efficacy of anti‐leukotrienes as monotherapy as compared to inhaled corticosteroids and to provide better insight into the influence of patient and treatment characteristics on the magnitude of effects.

In addition, several national guidelines currently advocate their use as second choice monotherapy after inhaled corticosteroids in patients with mild asthma and as adjunct therapy with inhaled corticosteroids as an alternative of combination of long acting β2‐agonist and inhaled corticosteroids in patients with moderate asthma (Australia 2006; NAEPP 2007; Lougheed 2010; GINA 2010; BTS 2011).

Objectives

The aims of this systematic review were:

to compare the safety and efficacy of daily oral anti‐leukotrienes with that of inhaled corticosteroids;

to determine the dose of inhaled corticosteroids equivalent to the effect of anti‐leukotrienes in the management of asthma in adults and children; and

to explore different factors such as patients' age group, disease severity, anti‐leukotriene used, intervention duration, hydrofluoroalkane‐propelled beclomethasone or equivalent (HFA‐BDP eq) dose of inhaled corticosteroids, methodological quality, publication status and funding that could influence the magnitude of effect.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in adults and children, or both, in which anti‐leukotrienes were compared with inhaled corticosteroids.

Types of participants

We included children (aged two to 17 years) and adults (aged over 18 years) with chronic persistent asthma. We included participants who were either corticosteroid‐naive or had been taking maintenance inhaled corticosteroid therapy prior to randomisation.

Types of interventions

We included trials with interventions consisting of daily oral anti‐leukotrienes at usual licensed doses (see under 'Unit of analysis issues') compared to any type of daily inhaled corticosteroids. Interventions had to be administered for at least four weeks. We excluded trials that administered concomitant anti‐inflammatory or anti‐asthmatic drug such as sodium cromoglycate or theophylline. Only rescue medications, such as inhaled short‐acting β2‐agonists and short courses of oral corticosteroids were permitted and recorded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids.

Secondary outcomes

Other clinical outcomes reflecting the severity of asthma exacerbations (e.g. hospital admissions, acute care visits)

Clinical or physiologic outcomes reflecting chronic asthma control (e.g. pulmonary function tests, symptom score, β2‐agonist use, measures of functional status, quality of life, patient's and physician's satisfaction, etc.)

Biological markers of inflammation (e.g. eosinophil count in blood and sputum, leukotriene C4 in biological samples, expired nitric oxide, etc);

Clinical and biochemical adverse effects (e.g., elevation of liver enzymes, growth)

Withdrawal rates (overall withdrawals, withdrawals due to poor asthma control and withdrawals due to adverse effects)

In studies designed to identify the minimum effective dose of inhaled corticosteroids needed to achieve asthma control, and in which the control obtained with inhaled corticosteroids was similar to that obtained with anti‐leukotrienes, we aimed to report the median effective dose of inhaled corticosteroids; this dose may be taken to be equivalent in effect to that of the anti‐leukotrienes. We excluded trials that only documented compliance.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 1 for further details). All records in the CAGR coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

(leukotriene* OR anti‐leukotriene* OR leukotriene* antagonist* OR lukast*) AND [inhaled corticosteroids* OR steroid* OR corticosteroid* OR cortico‐steroid* OR beclomethasone* OR fluticasone* OR budesonide* OR triamcinolone* OR flunisolide* OR bronalide* OR becotide* OR azmacort* OR aerobid* OR flixotide* OR aerobec* OR flovent* OR becloforte* OR pulmicort* OR aerobid* OR beclovent* OR azmacort* OR vanceril* OR ciclesonide OR alvesco).

Searching other resources

Reference lists of all identified RCTs were checked to identify potentially relevant citations. In addition, between 1998 and 2003, we searched abstract books of the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society Meetings; we contacted the international headquarters of pharmaceutical companies producing anti‐leukotrienes; and enquiries regarding other published or unpublished studies known and/or supported by these companies or their subsidiaries were made so that these results could be included in our 2003 review. In 2010, we searched the websites of pharmaceutical companies that are producers or distributors of inhaled corticosteroids or anti‐leukotrienes for any posted report of potential relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (BFC) reviewed and annotated each title and abstract returned from the search as either 1) RCT; 2) clearly not an RCT; or 3) unclear. The full text publications of references annotated as clearly, or potentially, relevant RCTs were obtained and reviewed by BFC.

Data extraction and management

Both review authors extracted data independently (BFC and FMD) and we dealt with disagreement by consensus. We consulted authors and the funding pharmaceutical companies for confirmation of data extraction for all included trials where necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the methodological quality of the eligible studies using the Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2008). This instrument evaluates the reported quality of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias.

We previously used the five‐point scoring instrument proposed by with the Cochrane Classification 'Risk of bias' tool to assess study quality. Based on revised recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we assessed the risk of bias for each eligible study according to six pre‐specified domains (Higgins 2008). Both review authors performed this quality assessment independently. We resolved disagreement by consensus. We sought confirmation of methodology for included trials directly from the authors or the funding pharmaceutical companies. We assessed risk of bias against the following domains.

Allocation generation. The method used to allocate participants to treatment group (e.g. computer‐generated random number sequences).

Allocation concealment. The method used to conceal the sequence of treatment group assignment from study investigators and participants (e.g. assignment by date of birth, opaque sealed envelopes).

Blinding. The method by which knowledge of treatment group assignment was concealed from study investigators and participants after the study began (double‐blind, single‐blind).

Completeness of outcome data. The method for handling data from participants who withdrew from the study (e.g. intention‐to‐treat analysis, available case).

Selective reporting. Whether there was evidence that outcomes measured in the study were unreported (e.g. unreported harms, relevant efficacy data that were not available due for reporting and not statistical reasons).

Other sources of bias. Any other aspect of the study design which may be a source of bias.

We collected and reported information for each domain of bias and provided a judgment based on this information as high, low or unclear risk of bias. We considered reported data with low risk in bias for the three main parameters (randomisation, blinding and low withdrawal rate in both groups) as high quality data for sensitivity analysis (see below).

Measures of treatment effect

We summarised differences between groups in event rates, such as number of exacerbations in a specific period, using either a ratio of rates or relative risk when pertaining to "one or more" events per patient. In continuous outcomes, such as pulmonary function tests or symptom scores, we used the mean difference (MD) or standard mean difference (SMD) method as indicated to estimate the individual and pooled effect sizes. We reported all estimates with their 95% confidence interval and performed meta‐analysis using Reference Manager 5.1 (RevMan).

Studies designed to test equivalence in treatment efficacy require a different analytical approach to that used for trials in which the hypothesis under test is that one treatment has greater efficacy than its comparator. This is because small trials may favour the conclusion that there was no difference between treatments, since the confidence intervals for the two treatments will be wide and therefore more likely to include the line of no difference between the two treatments. We set limits of treatment efficacy at +/‐ 0.10 on either side of the no‐difference line for the number of patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids. The null hypothesis tested whether the confidence interval for the difference between the two treatments included one of these limits.

Unit of analysis issues

We referred to usual licensed doses of leukotriene receptor antagonists as: montelukast 4, 5, or 10 mg daily (patients aged two to five, six to 14 and > 15 years respectively); pranlukast 450 mg daily (children aged ≥ 12 years and adults), and zafirlukast 20 mg twice daily (children aged ≥ 12 years and adults). Doses of inhaled corticosteroids were converted to microfine HFA‐BDP eq based on 1 μg of fluticasone = 1 μg of microfine HFA‐propelled beclomethasone = 1 μg of ciclesonide = 1 μg of mometasone = 2 μg of budesonide = 2 μg of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)‐propelled beclomethasone = 4 μg triamcinolone = 4 μg of flunisolide (NAEPP 2007). All doses of inhaled medications are reported based on ex‐valve, rather than ex‐inhaler, value.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested homogeneity of effect sizes between pooled studies using the DerSimonian and Laird method or the I2, which estimates the amount of statistical variation between the studies above what would be expected with the play of chance (Cochrane Handbook). We set values of P greater than 0.05 or I2 greater than 25% as providing an indication of significant heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was suggested by one or both statistical methods, we applied the DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model to the summary estimates (available in RevMan). Unless specified otherwise we employed the fixed‐effect model.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to test for the presence of possible publication bias (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

Meta‐analyses were performed using Reference Manager 5.1 (RevMan). We derived the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) or number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) from the pooled Odds Ratio using Visual Rx (www.nntonline.net). We used this method because the resulting NNTB or NNTH is independent of the way that the data are entered, which is not the case for relative risk (Cates 2002).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analysis to explore possible reasons for heterogeneity of the primary outcome. All outcomes were stratified in children versus adults for the specific purpose of providing estimates particularly for these age groups and to explore a possible modifying effect of age. Additional a priori defined subgroups included:

anti‐leukotriene used (montelukast versus zafirlukast);

doses of inhaled corticosteroids in HFA‐BDP eq (100 to ‐150 µgversus 200 to ‐250 µg versus 400 to 500 µg HFA‐BDP eq);

intervention duration (four to eight weeks versus 12 to 16 weeks versus 24 to 26 weeks versus 36 to 52 weeks);

baseline severity of airway obstruction (moderate = FEV1 60 to 79% versus mild = FEV1 ≥80%);

publication status;

funding source.

We examined the difference in the magnitude of effect attributable to these subgroups with the residual Chi2 test from the Peto odds ratios (Deeks 2001).

Sensitivity analysis

For the primary outcome, we performed sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the effect of methodological quality based on the reported quality of randomisation, concealment of allocation, blind assessment of outcomes, and description of withdrawals and dropouts. The fail‐safe N test will be used to assess the robustness of the results (Gleser 1996).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy updated up to December 2010 yielded a total of 401 additional citations which combined to 658 previously identified citations lead to a total of 1053 citations. The data hereafter are presented as total exclusions (exclusions from latest search + exclusions from previous search). Of these 652 (319 + 333) citations were excluded for the following non‐mutually exclusive reasons: (1) duplicate references (31 + 162 = 193), (2) not a randomised controlled trial (31 + 253 = 284) or ongoing trials (23 + 1 = 24), (3) subjects were not asthmatics (3 + 17 = 20), (4) the tested intervention was not anti‐leukotrienes (82 + 17 = 99), (5) the control intervention was not inhaled corticosteroids (65 + 124 = 189), (6) use of higher than licensed doses of anti‐leukotrienes (from previous review = 1) (Korenblat 1998), (7) use of non permitted drugs (106 + 28 = 134), (8) the tested intervention was administered for less than 4 weeks (14 + 19 = 33), (9) acute care setting (3 + 1 = 4). Due to the large number of citations considered, the references and reasons for exclusion were provided only for full‐text randomised controlled trials in the last review up to October 2003, while reasons for exclusion for all references were included for 2003 to 2010. Some trials were excluded with more than one reason.

Included studies

Sixty‐five trials met the inclusion criteria for this review. There were nine (237 children and 241 adults) eligible clinical trials that did not contribute data to the review due to different format of presenting data than specified in the protocol or incomplete reports (Riccioni 2003; Basyigit 2004; Abadoglu 2005; Zeiger 2006; Lazarus 2007; Kanazawa 2007; Stelmach 2008; Khan 2008; Zedan 2009). The data presented hereafter pertains to only the 56 eligible trials representing total of 10,005 adults and 3,333 children with mild or moderate asthma that contributed data to meta‐analyses. Of these, most (N = 44) trials were published in full text; three were published as abstracts with additional unpublished report provided by the authors (Laitinen 1997; Hughes 1999 (FP); Hughes 1999 (BDP)) and the remaining nine citations were available only in abstract form (FLTA4031; FLTA4030; FMS40012; Dempsey 2002a; Sheth 2001; FPD40013; Jayaram 2002; NCT00442559; MK0479‐332). We described below the characteristics of the 56 trials that contributed to data analysis for this review.

Design: Sixteen paediatric and 33 adult trials had a parallel‐group design while three paediatric (Szefler 2005; Caffey 2005; Ng 2007) and four adult trials (Dempsey 2002a; Kanniess 2002; Jenkins 2005; Lu 2009) had a cross‐over design.

Participants: Thirteen trials involved children (Maspero 2001; FPD40013; Garcia Garcia 2005; Ostrom 2005; Peroni 2005; Caffey 2005; Ng 2007; Szefler 2007; Kumar 2007; Sorkness 2007; NCT00442559; Kooi 2008; Zielen 2010); five trials involved children and adolescents (Stelmach 2004; Stelmach 2005; Szefler 2005; Zeiger 2005; Stelmach 2007); one trial did not report the age of children (Peroni 2005); 19 trials involved adolescents and adults (FLTA4031; FLTA4030; Malmstrom 1999; Laviolette 1999; Bleecker 2000; Kim 2000; Nathan 2001; Busse 2001a; Busse 2001b; Meltzer 2002; Israel 2002; Brabson 2002; Baumgartner 2003; Jenkins 2005; Bousquet 2005; Koenig 2008; Lu 2009; Sheth 2001; Sheth 2001b); 10 trials involved adults (FMS40012; Riccioni 2001; Dempsey 2002a; Riccioni 2002b; Kanniess 2002; Yurdakul 2003; Overbeek 2004; Boushey 2005; Tamaoki 2008; MK0479‐332); and one trial involved adults and children (Peters 2007). Most trials described a gender ratio of 45% to 50% (range 18% to 81%) males. Almost half of the trials (N = 27) focused on asthmatics with mild airway obstruction, as defined as a baseline FEV1 ≥ 80% of predicted, 25 trials (Laitinen 1997; FLTA4031; FLTA4030; Malmstrom 1999; Laviolette 1999; Bleecker 2000; Nathan 2001; Busse 2001a; Busse 2001b; Meltzer 2002; FPD40013; Stelmach 2002a; Stelmach 2002b; Israel 2002; Kanniess 2002; Baumgartner 2003; Stelmach 2004; Stelmach 2005; Ostrom 2005; Jenkins 2005; Jayaram 2005; Kumar 2007; Koenig 2008; Lu 2009) focused on asthmatics with moderate airway obstruction, as defined as a baseline FEV1 60 to 79% of predicted; one trial reported mild to moderate airway obstruction (NCT00442559), while three trials (Jayaram 2002; Kooi 2008; MK0479‐332) did not reported the severity of airway obstruction at baseline. Asthma triggers were seldom reported, when atopy was reported. Intervention duration: Most paediatric and adult trials varied in the duration of intervention from four to eight weeks. Five paediatric trials (FPD40013; Ostrom 2005; Kumar 2007; NCT00442559; Kooi 2008) and 13 adult trials (FLTA4031; FLTA4030; Malmstrom 1999; Laviolette 1999; Bleecker 2000; Busse 2001a; Sheth 2001; Riccioni 2002a; Riccioni 2002b; Yurdakul 2003; Zeiger 2005; Peters 2007; Koenig 2008) were of 12 to 16 weeks; two paediatric trials (Maspero 2001; Stelmach 2005) and three adult trials (Busse 2001b; Meltzer 2002; MK0479‐332) were of 24 to 26 weeks; while three paediatric trials (Garcia Garcia 2005; Szefler 2007; Sorkness 2007) and two adult trials (Boushey 2005; Bousquet 2005) were of 36 to 52 weeks duration.

Intervention drugs were: montelukast 4, 5 or 10 mg per day, depending on age, for the 19 paediatric trials, montelukast 10 mg per day in 23 adult studies; pranlukast 450 mg per day in two trials (Yamauchi 2001; Tamaoki 2008), and zafirlukast 20 mg twice a day in 12 adult trials (Laitinen 1997; FLTA4031; FLTA4030; Bleecker 2000; Kim 2000; FMS40012; Nathan 2001; Riccioni 2001; Busse 2001b; Sheth 2001; Brabson 2002; Boushey 2005). One study tested two doses of anti‐leukotrienes, including a higher than licensed doses of zafirlukast (i.e. 80 mg per day) (Laitinen 1997).

The daily dose of inhaled corticosteroids (control intervention) in μg HFA‐BDP eq was relatively uniform across the 56 trial: eight trials tested a daily dose of 100 μg HFA‐BDP eq (FPD40013; Stelmach 2002a; Stelmach 2002b; Stelmach 2004; Ostrom 2005; Caffey 2005; Stelmach 2007; Tamaoki 2008); two trials tested a daily dose of 150 μg HFA‐BDP eq (Maspero 2001; Dempsey 2002a); 37 trials tested a daily dose of 200 μg HFA‐BDP eq.; two trials tested a daily dose of 250 μg HFA‐BDP eq (Jenkins 2005; Szefler 2007); three trials tested a daily dose of 400 μg HFA‐BDP eq (Riccioni 2001; Riccioni 2002a; Riccioni 2002b); two trials tested a daily dose of 500 μg HFA‐BDP eq (Jenkins 2005; MK0479‐332); and two trials did not mentioned the dose of inhaled corticosteroids (Jayaram 2002; NCT00442559). In all trials, the dose of inhaled corticosteroids was maintained throughout the intervention period; no trial tapered the dose of inhaled corticosteroids to the minimum effective dose.

Co‐intervention. No trials reported the use of additional anti‐asthmatic drugs other than rescue β2‐agonists and systemic corticosteroids.

Outcomes

Whenever possible, we considered outcomes measured at four to eight weeks, 12 to 16 weeks, 24 to 26 weeks and 36 to 52 weeks. The primary outcome, patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids, was documented in six (32%) paediatric and 15 (41%) adult trials; children contributed 23% of the weight of the main outcome. Other reported outcomes included patients with at least one exacerbation requiring admission, change from baseline FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) (L), change from baseline FEV1 (%), change in FEV1 % of predicted, change in morning PEFR (peak expiratory flow rate) (L/min), change from baseline in daytime symptom scores, change from baseline in night‐time awakenings, change from baseline in mean daily use of β2‐agonists (puffs/day), change in proportion of symptom‐free days, change in rescue‐free days, change from baseline in quality of life, days with use of β2‐agonists, change from baseline in blood eosinophils, change in sputum eosinophils, leukotriene C4 concentration in nasal wash, % asthma control days during intervention period, change in PC20, % rescue‐free days, days off work or school, days with symptoms, days with β2‐agonist use (%), change in growth (cm), patient's satisfaction, physician's satisfaction, overall withdrawals, withdrawal due to poor asthma control/exacerbations, withdrawal due to adverse effects, overall adverse effects, elevated liver enzymes, upper respiratory tract infections, headache, nausea, oral candidiasis, hoarseness and death.

Risk of bias in included studies

Full details of the risk of bias for all 65 eligible trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables with a graphical summary of in Figure 1.The following information pertains only to the 56 trials contributing data to the meta‐analysis.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Although all trials were described as randomised, only 32 trials (10 paediatric and 22 adult trials) reported the method of randomisation. Therefore, we judged 32 trials to be at low risk of bias and 24 rest were unclear. Fifty‐two trials did not describe the method of concealment of treatment and were therefore judged at unclear risk of bias, while four trials reported the way the concealment was performed and were judged to be of low risk of bias.

Blinding

Forty‐one trials (13 paediatric and 28 adult trials) reported double‐blinding with convincing details, while nine trials used open label and six trials did not report sufficient information to ascertain blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Forty‐two trials (14 paediatric and 28 adult trials) reported all data with balanced numbers in both groups, while seven trials failed to do so and seven trials were unclear.

Selective reporting

This bias refers to an outcome measured as part of the protocol but not reported in the publication. Judging from the reported methodology in the publication, most (N = 52) trials reported data without any apparent biasness, two trials were assessed as being at high risk of bias while the remaining two trials failed to report sufficient details for this assessment. With the similar proportion of paediatric (N = 6, 32%) and adult (N = 15, 41%) trials reporting the main outcome, there is no suspicion of a differential under reporting of this outcome in paediatric versus adult studies.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not encounter any other significant sources of bias in the included trials.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome: people with at least one exacerbation requiring a course of oral corticosteroids

Twenty‐one (33%) trials on 6077 participants contributed to the primary end point; people with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids. Compared with inhaled corticosteroids, patients treated with anti‐leukotrienes had a 51% increased risk of experiencing one or more exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids (Risk ratio (RR) = 1.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17, 1.96; random‐effects model), that is, from 7% to 11% (Figure 2).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), outcome: 1.1 Patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic steroids.

The number need to treat to prevent one more exacerbation requiring corticosteroid (NNT) is 28 (95% CI 15 to 82; Figure 3). There was no evidence of systematic bias identified by the test for funnel plot asymmetry (intercept 0.33, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.75; Figure 4). The fail‐safe N (the number of unpublished studies with null results needed to negate the current finding) was 180 trials. Selecting only one inhaled corticosteroid group (BDP or FP) as comparator in the three‐group Hughes trial fail to affect the overall estimate due to the absence of events in this study. There was heterogeneity between and within anti‐leukotrienes, the following subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed on the main outcome to explore possible effect modifiers.

3.

In the control group (on ICS) 7 people out of 100 had at least one exacerbation requiring systemic steroids over 4 to 52 weeks, compared to 10 (95% CI 8 to 13) out of 100 for the active treatment group given LRTA.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) versus. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), outcome: Patients with at least 1 exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids.

Subgroup analysis: Age group of subjects

Six (32%) paediatric trials on 1662 children and 15 (41%) adult trials on 4415 adults reported the primary outcome, number of patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids; children contributed 23% of the weight of the summary estimate. There was no significant group difference between paediatric (N = 6 trials, 1662 participants; RR 1.35; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.86) compared with adult, (N = 15 trials, 4415 participants; RR 1.61;95% CI 1.12 to 2.31) trials (Chi2 = 1.95 (1 df), P = 0.16; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 1 Patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic steroids.

Subgroup analysis: Anti‐leukotrienes

There was no significant difference in the risk of patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids according to the anti‐leukotriene used (montelukast versus zafirlukast) (Chi2 = 0.12 (1 df), P = 0.73); montelukast [N = 15 trials, 4352 participants: RR = 1.55 (95% CI: 1.14 to 2.12; Analysis 1.67)versus zafirlukast (N = 6 trials, 1725 participants; RR 1.92;95% CI 0.88 to 4.20).

1.67. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 67 Primary outcome ‐ stratified by anti‐leukotrienes.

Subgroup analysis: Duration of intervention

The duration of intervention was not a determinant of the magnitude of effect (Chi2 = 5.42 (3 df), P = 0.14): four to eight weeks (N = 9 trials, 2346 participants; RR 1.74; 95% CI 0.78 to 3.87; Analysis 1.68), 12 to 16 weeks (N = 7 trials, 1541 participants; RR 2.06; 95% CI 1.43 to 2.96), 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 trials, 657 participants; RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.55 to 2.45), and 36 to 52 weeks (N = 3 trials, 1533 participants; RR = 1.29; 95% CI 0.87 to 1.91).

1.68. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 68 Primary outcome ‐ stratified by duration of intervention.

Subgroup analysis: Severity of airway obstruction

Baseline severity of airway obstruction played a significant role in the magnitude of the risk of exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroid (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 4.59, (df = 1), P = 0.03, I² = 78.2%); baseline FEV1 between 60 to 79% of predicted (N = 11 trials, 3922 participants; RR = 2.03; 95% CI 1.41 to 2.91; Analysis 1.69) versus baseline FEV1 ≥ 80% of predicted (N = 10 trials, 2155; RR = 1.25; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.61).

1.69. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 69 Main outcome ‐stratified by severity of airway obstruction.

Subgroup analysis: Methodological quality

There was no significant group difference among the trials with high reported methodological quality (N = 11 trials, 4366 participants; RR = 1.62; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.03; Analysis 1.70) compared with hose with poor quality (N = 10 trials, 1695 participants; RR = 1.34; 95% CI 0.74 to 2.43) (Chi2 = 0.22 (1 df), P = 0.64).

1.70. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 70 Primary outcome ‐ stratified by methodological quality.

Subgroup analysis: Funding source

The source of funding did not significantly influence results (Chi2 = 3.61 (2 df), P = 0.16): funding from producers of inhaled corticosteroids (N = 9 trials, 2638 participants; RR = 1.71; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.80; Analysis 1.71), funding from producers of anti‐leukotrienes (N = 5 trials, 2797 participants; RR = 1.52; 95% CI 0.99 to 2.35) and no industry funding or not reported funding (N =7 trials, 642 participants; RR =1.22; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.66).

1.71. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 71 Primary outcome‐ stratified by funding source.

Subgroup analysis: HFC‐BDP equivalent

The comparative dose of inhaled corticosteroids did not significantly influence the magnitude of the risk of exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids (Chi2 = 1.97 (1 df), P = 0.16): 100 to 150 μg HFC‐BDP equivalent (N = 3 trials, 216 participants; RR = 0.74; 95% CI 0.26 to 2.08; Analysis 1.72), 200 to 250 μg HFC‐BDP equivalent (N = 15 trials, 5767 participants; RR = 1.75; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.38), and 400 to 500 μg HFC‐BDP equivalent (N = 3 trials, 94 participants; RR = 0.54; 95% CI 0.11 to 2.78).

1.72. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 72 Primary outcome ‐ stratified by HFC‐BDP equivalent.

Secondary outcomes reflecting the severity of asthma exacerbations

There was a three‐fold increase in the number of patients experiencing an exacerbation requiring hospital admission in the group treated with anti‐leukotrienes (N = 12 trials, 2715 participants; RR = 3.33; 95% CI: 1.02 to 10.94; Analysis 1.2) with no significant difference across the paediatric trials (N = 4 trials, 558 participants; RR = 3.04; 95% CI 0.12 to 73.93) and adult (N = 8 trials, 2157 participants; RR = 3.38; 95% CI 0.94 to 12.17) trials (Chi2 = 0.00 (1 df), P = 0.95).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 2 Patients with at least one exacerbation requiring hospital admission.

Secondary outcomes reflecting asthma control

Lung function

Compared with inhaled corticosteroids, a significant group difference in the improvement from baseline in FEV1 (L) was observed at all points in time in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes: at four to eight weeks (N = 12 trials, 3020 participants; mean difference (MD) ‐0.12 L; 95% CI ‐0.15 to ‐0.08, random‐effects model; Analysis 1.3), at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 9 trials, 1890 participants; MD ‐0.12 L; 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.04, random‐effects model; Analysis 1.4), and at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 3 trials, 1178 participants; MD ‐0.13 L; 95% CI ‐0.22 to ‐0.04; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.5), at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 2 paediatric trials, 1040 participants; MD ‐0.03 L; 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.00; model; Analysis 1.6). Similarly, a significant group difference in the per cent change from baseline FEV1 was observed in time in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes: at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 2 adults trials, 603 participants; MD ‐5.70, 95% CI ‐9.81 to ‐1.59; Analysis 1.10) and at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 adult trials, 838 participants; MD ‐8.20%; 95% CI ‐10.85 to ‐5.55; Analysis 1.11), and only one trial reporting data at four to eight weeks and at 36 to 52 weeks each, precluding aggregation.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 3 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 4 Change from baseline FEV1( L) 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 5 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 6 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 10 Change from baseline FEV1 (%) 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 11 Change from baseline FEV1 (%) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

No significant group difference was observed with regards to the change from baseline FEV1 % predicted at four to eight weeks (N = 2 trials, 219 participants; MD ‐2.58%; 95% CI ‐6.56 to 1.40; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.12), but a significant group difference was observed in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 3 trials, 948 participants; MD ‐3.76%; 95% CI ‐5.01 to ‐2.50; Analysis 1.13) and at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 3 paediatric trials, 1229 participants; MD ‐3.51%; 95% CI ‐7.14 to 0.12; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.14).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 12 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicted at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 13 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicated at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 14 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicated at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

A significant group difference in the change from baseline morning PEFR in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes was observed at four to eight weeks (N = 8 trials, 1926 participants; MD ‐15.12 L; 95% CI ‐20.80 to ‐9.44; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.15), at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 10 trials, 2713 participants; MD ‐19.07 L; 95% CI ‐25.86 to ‐12.27; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.16), 24 to 26 weeks (N = 3 trials, 1718 participants; MD ‐21.62 L; 95% CI ‐40.19 to ‐3.05; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.17) and at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 4 trials, 1652 participants; MD ‐5.34 L; 95% CI ‐9.35 to ‐1.34; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.18).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 15 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 16 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 17 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 18 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

Symptom scores

A significant group difference in the improvement from baseline daytime symptom scores in favour of inhaled corticosteroids were observed at four to eight weeks (N = 6 trials, 1925 participants; standard mean difference (SMD) 0.20; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.32; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.19), at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 3 adult trials, 1719 participants; (SMD 0.22; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.42)SMD 0.25; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.33; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.21), but not at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 9 trials, 2650 participants; (SMD 0.25; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.33); random‐effects model; Analysis 1.20) or 36 to 52 weeks (N = 2 paediatric trials, 582 participants; SMD 0.16 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.34; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.22).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 19 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 21 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 20 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 22 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

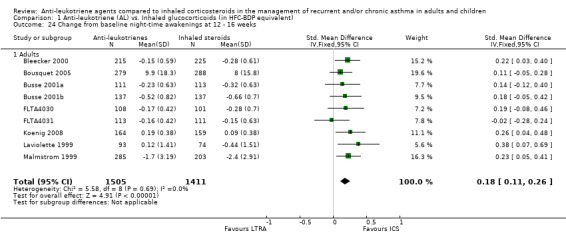

Nightime awakening

A significant group difference in favour of inhaled corticosteroids was observed for change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 9 adult trials, 2916 participants; SMD 0.18, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.26; Analysis 1.24), at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 trials, 1055 participants; SMD 0.23; 95% CI 0.11 to 0.35; Analysis 1.25), but not at four to eight weeks (N = 3 adult trials, 798 participants; SMD = 0.22; 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.46; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.23); only one trial reported at 36 to 52 weeks, precluding aggregation.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 24 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 25 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 23 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 4 ‐ 8 week.

Rescue medication use

A significant group difference in the reduction from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists in favour of inhaled corticosteroids as observed at four to eight weeks (N = 10 trials, 3264 participants; SMD 0.20; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.34; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.26), at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 12 trials, 3479 participants; SMD 0.23; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.30; Analysis 1.27), at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 adult trials, 1055 participants; SMD 0.31; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.43; Analysis 1.28), only one paediatric trial reporting data at 36 to 52 weeks, precluding aggregation.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 26 Change from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 27 Change from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 28 Change from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

No significant difference was observed in change from baseline rescue‐free days (%) at four to eight weeks (N = 5 trials, 1315 participants; MD ‐6.83 %; 95% CI ‐17.73 to 4.07; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.30), but a significant group difference was observed in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes: at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 7 trials, 2304 participants; MD ‐9.64 %; 95% CI ‐13.71 to ‐5.56; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.31) and at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 3 trials, 1949 participants; MD ‐3.38 %; 95% CI ‐5.49 to ‐1.27; Analysis 1.33). Only one trial reported data at 24 to 26 weeks, precluding aggregation.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 30 Change in rescue‐free days (%) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 31 Change in rescue‐free days (%) at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 33 Change in rescue‐free days (%) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

Symptom‐free days

A significant group difference was observed in change in proportion of symptom‐free days (%) at all points in time in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes at four to eight weeks (N = 3 adult trials, 1154 participants; MD ‐10.46%; 95% CI ‐14.56 to ‐6.36; Analysis 1.34), at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 9 trials, 2535 participants; MD ‐8.89%; 95% CI ‐11.92 to ‐5.87; Analysis 1.35), and at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 4 trials, 1805 participants; MD ‐5.71%; 95% CI ‐8.68 to ‐2.74; Analysis 1.36). Only one trial reported data at 24 to 26 weeks, precluding aggregation.

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 34 Change in proportion of symptom‐free days (%) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 35 Change in proportion of symptom‐free days (%) at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 36 Change in proportion of symptom‐free days (%) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

Quality of life

A significant group difference was observed in the change in quality of life at all points in time in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes: at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 2 adult trials, 1065 participants; MD ‐0.21; 95% CI ‐0.34 to ‐0.09; Analysis 1.39), at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 adult trials, 1028 participants; MD ‐0.38; 95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.21; Analysis 1.40), at 36 to 52 weeks (N = 2 trials, 1034; MD ‐0.19; 95% CI ‐0.31 to ‐0.07; Analysis 1.41). Only one trial reported data at four to eight weeks, precluding aggregation. Only one trial reported data on days with use of β2‐agonists at 36 to 52 weeks; Analysis 1.56, precluding aggregation.

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 39 Change from baseline quality of life (QOL) at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.40. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 40 Change from baseline quality of life (QOL) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

1.41. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 41 Change from baseline quality of life (QOL) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks.

Airway inflammation

Although few trials examined indices of airway inflammation, there was a significant group difference in the reduction in blood eosinophils in favour of inhaled corticosteroids at four to eight weeks (N = 4 trials, 1294 participants; MD 0.06 x 109, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.10; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.43) but not at 12 to 16 weeks (N = 2 trials, 1013 participants; MD ‐0.0 x 109, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.02; Analysis 1.44) and only one trial reported at 36 to 52 weeks. However, no significant group difference was observed in sputum eosinophils at four to eight weeks (N = 2 trials, 117 participants; MD 0.71 x 109; 95% CI ‐2.06 to 3.47; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.45) and only one trial reported at 36 to 52 weeks. One paediatric trial examined the change in LTC4 concentration in nasal washes with no group difference observed at 12 to 24 weeks; Analysis 1.47.

1.43. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 43 Change from baseline blood eosinophils at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.44. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 44 Change from baseline blood eosinophils at 12 ‐ 16 weeks.

1.45. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 45 % Change in sputum eosinophils at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.47. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 47 LTC4 concentration (ng/mL) in nasal wash at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

Asthma control days

Few trials evaluated the percentage of asthma control days during the intervention period; it was in disfavour of anti‐leukotrienes at four to eight weeks (N = 2 trials, 1293 participants; MD ‐5.72%; 95% CI ‐10.86 to ‐0.59; Analysis 1.48) and at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 trials, 1185 participants; MD ‐8.19%; 95% CI ‐19.46 to 3.07; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.49).

1.48. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 48 % Asthma control days during intervention period at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

1.49. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 49 % Asthma control days during intervention period at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

Bronchial challenge (PC20)

Only one trial reported PC20 at four to eight weeks, Analysis 1.50, precluding aggregation.

1.50. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 50 Change in PC20 at 4 ‐ 8 weeks.

There was no significant group difference in days off work or school at 24 to 26 weeks (N = 2 trials, 606 participants; MD 0.12; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.26; Analysis 1.52). Only one trial reported patient and physician's level of satisfaction, precluding aggregation.

1.52. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 52 Days off work or school at 24 ‐ 26 weeks.

Only one study (Sorkness 2007) reported change in height in paediatric patients at 48 weeks (Analysis 1.53).

1.53. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 53 Change in height (cm).

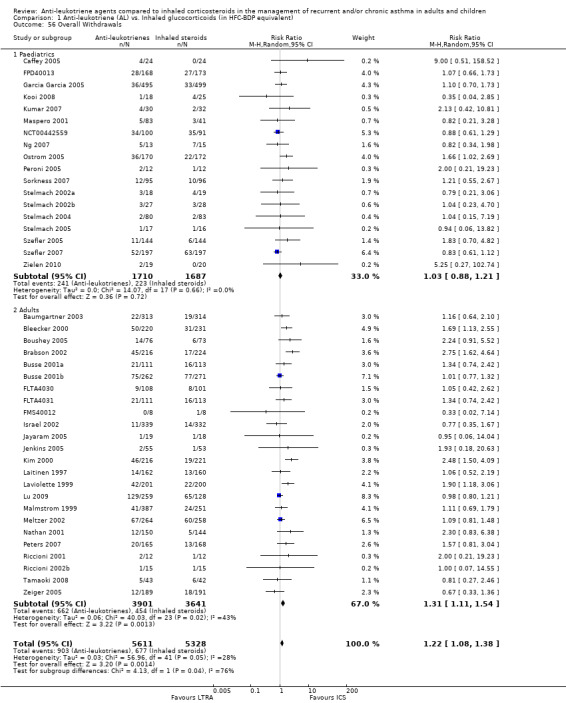

Withdrawals

Anti‐leukotriene therapy was associated with a 24% increased risk of overall withdrawals (N = 43 trials, 11,317 participants; RR 1.22; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.37; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.56) (Chi2 = 3.07 (1 df), P = 0.08).The withdrawals appeared to be attributable to an increased risk of withdrawals due to poor asthma control (N = 26 trials, 7669 participants; RR 2.56; 95% CI 2.01 to 3.27; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.57) and with no statistically significant group difference due to adverse effects (N = 25 trials, 8518 participants, RR 1.24; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.63; P = 0.12; Analysis 1.58). Of note, there was no significant effect of age group on these withdrawal rates. The number needed to treat to harm (NNTH), that is, to observe one withdrawal due to poor asthma control is 31 (95% CI 22 to 47); in other words, 31 patients need to be treated with anti‐leukotrienes rather than inhaled corticosteroids to observe one more withdrawal due to poor asthma control (Figure 5).

1.56. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 56 Overall Withdrawals.

1.57. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 57 Withdrawal due to poor asthma control/exacerbations.

1.58. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 58 Withdrawals due to adverse effects.

5.

In the control group (on ICS) 2 people out of 100 had withdrawal due to poor control over 4 to 52 weeks, compared to 6 (95% CI 4 to 7) out of 100 for the active treatment group (given LRTA).

Adverse effects

There was no significant group difference in the number of patients who experienced "any adverse effects", (N = 22 trials, 7818 participants; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.05; P = 0.90; Analysis 1.59), which met our definition of equivalence. There was also no significant group difference in elevation of liver enzymes (N = 7 trials, 1716 participants; RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.58 to 2.19; Analysis 1.60), upper respiratory infections (N = 8 trial, 2729 participants; RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.29; Analysis 1.61), headache (N = 24 trials, 8872 participants; RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.11; Analysis 1.62), nausea (N= 17 trials, 5563 participants; RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.64 to 1.08; Analysis 1.63), oral candidiasis (N = 3 trials, 865 participants; RR 0.25; 95% CI 0.05 to 1.19; Analysis 1.64), or death (N= 13 trials, 5489 participants; RR 3.05; 95% CI 0.32 to 29.26; Analysis 1.66) which was reported in only two trials both in anti‐leukotriene group. Only one trial reported growth in paediatric patients and the change in height between two groups could not achieve a statistical significant level Analysis 1.53; Sorkness 2007).

1.59. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 59 Overall Adverse effects.

1.60. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 60 Elevated liver enzymes.

1.61. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 61 Upper respiratory tract infections.

1.62. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 62 Headache.

1.63. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 63 Nausea.

1.64. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 64 Oral candidiasis.

1.66. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent), Outcome 66 Death.

Discussion

In adults and children with mild to moderate airway obstruction due to persistent asthma, four to 52 weeks of treatment with daily oral anti‐leukotrienes carries a 51% increased risk (from 7% to 11%) of an asthma exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids than treatment with inhaled corticosteroids at a median dose of 200 HFA‐BDP eq. Twenty‐eight people need to be treated with inhaled corticosteroids rather than anti‐leukotriene to prevent one person from experiencing an exacerbation requiring corticosteroid i.e. the NNT is 28. These data appear robust as 180 new trials with no group difference would be needed to reverse these findings.

The baseline severity of asthma obstruction significantly influenced the magnitude of response; indeed, the risk of exacerbation requiring rescue systemic steroids was increased by 'two‐fold' in patients with moderate airway obstruction treated with anti‐leukotrienes rather than inhaled corticosteroids, while the risk was increased by 25% in patients with mild asthma obstruction. The magnitude of the risk was not significantly influenced by age, choice of anti‐leukotrienes, duration of intervention, publication status, methodological quality, funding source and dose of inhaled corticosteroids in HFA‐BDP eq.

Secondary outcomes clearly favoured the use of inhaled corticosteroids over anti‐leukotriene agents in adults and children. There was a three‐fold increase in the risk of patients experiencing an exacerbation requiring hospital admission when treated with anti‐leukotriene agents compared with inhaled corticosteroids. With regards to other indicators of asthma control, inhaled corticosteroids were more effective than anti‐leukotrienes in improving lung function (FEV1 and PEFR), the percentage of symptom‐free and rescue‐free days, as well as in reducing symptoms, night‐time awakenings and rescue β2‐agonist use. These group differences were generally present at all points in time over four to 52 weeks of treatment.

The risk of overall adverse effects was similar in both treatment groups, meeting our a priori definition of equivalence. There was also no group difference in the following specific adverse effects, namely liver enzyme elevation, headaches, upper respiratory infections, oral candidiasis, nausea, and death. Anti‐leukotriene use was not associated with an increased risk of withdrawals due to adverse effects. However, adverse effects typically associated with inhaled corticosteroids such as growth suppression (in children), osteopenia and adrenal suppression were seldom measured except in one trial (Sorkness 2007, in which growth was measured), thus preventing a fair comparison of the safety of long‐term use of inhaled corticosteroids versus anti‐leukotrienes.

The increased risk of all‐cause withdrawals was significantly higher among patients treated with anti‐leukotriene agents as compared to inhaled corticosteroids. Most of the increased risk seems attributable to increased withdrawals due to poor asthma control with the use of anti‐leukotrienes which indirectly supports the superiority of inhaled corticosteroids over anti‐leukotrienes.

The results of this review pertain to asthmatic adults and children with a mild or moderate persistent asthma. The results can apply to school‐aged children; 19 trials with paediatric and adolescents contributed data to the review of which six trials (23% of the weight of the summary estimate) contributed to the primary outcome. The relatively modest number of trials could fall in the priori defined category of high methodological quality indicates either poor designing of trials or inadequate reporting of methodology. More long‐term trials are needed to compare the safety of anti‐leukotrienes versus inhaled corticosteroids as monotherapy in the treatment of paediatric asthma, as only one trial reported growth or effect of long‐term administration of inhaled corticosteroids in paediatrics.

This review summarises the best evidence available until December 2010. With a total of 56 trials (37 adult and 19 paediatric), it represents a significant update from the previous update in August 2003 which was based on 25 trials (22 adult and three paediatric). With 16 more paediatric trials than in the prior review, the current data more adequately represents children; paediatric trials represent now 23% of weight of the primary outcome compared with 6.7% in the prior review. While the results remain admittedly notably influenced by adults, the absence of a significant group difference between adults and children would support that the conclusion apply to both age groups. Twenty‐one (38%) of 56 trials contributing data to the meta‐analysis were of high reported methodological quality as per our predefined criteria using the Cochrane Classification 'Risk of bias' tool (29% of paediatric and 71% of adult trials); the impact of the large proportion of lower reported methodological quality on study results is unclear but could have led to an overestimation of the true effect. On the other hand, the robustness of the study results is supported by the fail‐safe N of 180 trials indicating the number of unpublished/future studies with no group difference in rescue oral corticosteroids needed to change the direction of the current findings. Consequently, in line with the previous version, the present review confirms the greater efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids administered at a median dose of 200 HFA‐BDP eq over anti‐leukotrienes in children and adult with mild and moderate persistent asthma.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In symptomatic adults and children with mild or moderate asthma, anti‐leukotrienes are less effective than inhaled corticosteroids at a median dose of 200 HFA‐BDP eq for preventing exacerbations and achieving asthma control; the superiority of ICS is particularly marked in patients with moderateversus mild airway obstruction but does not appear influenced by age, duration of intervention, or anti‐leukotriene used. The use of anti‐leukotrienes is associated with a 51% increased risk of experiencing an exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids, a three‐fold increased hospital admission rate and more than a two‐fold increased risk of withdrawals due to poor asthma control compared to inhaled corticosteroids. The superiority of inhaled corticosteroids was also observed in lung function, symptoms, use of rescue β2‐agonists, quality of life, inflammatory markers and withdrawals including withdrawals due to poor asthma control. Although anti‐leukotrienes have a similar safety profile to that of inhaled corticosteroids, one must note that adverse effects typically associated with inhaled corticosteroids such as growth suppression (in children), osteopenia and adrenal suppression have not been measured in these trials. On the basis of efficacy, the results support the current guidelines' recommendation that inhaled corticosteroids remain the preferred monotherapy in adults and children with persistent asthma.

Implications for research.

There is little need for additional efficacy studies in this area, other perhaps than to determine the exact dose‐equivalence of anti‐leukotrienes, which is clearly less than 200 μg/day of HFA‐BDP eq or to compare the safety profile (on growth) in children. Acknowledging the low and potential differential adherence rate to daily controller therapies, one area of interest is certainly examining the real‐life effectiveness of low‐dose daily inhaled corticosteroids compared to anti‐leukotrienes,

Long‐term high methodological quality trials with adequate documentation of adverse effects associated with inhaled corticosteroids are needed to provide a fair comparison of the safety of both treatment options. Future trials should aim for the following design characteristics:

pragmatic effectiveness trials;

double blinding, adequate randomisation and complete reporting of withdrawals and drop outs with intention‐to‐treat analysis;

parallel‐group;

have a minimal intervention period of 24 to 52 weeks to assess the long‐term side effects of both interventions (anti‐leukotrienes and inhaled corticosteroids);

complete reporting of continuous (denominators, mean change and mean standard deviation of change) and dichotomous (denominators and rate) data;

specific reporting of exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids;

systematic documentation of reasons for withdrawals and adverse effects, including those associated with inhaled corticosteroids such as oral candidiasis, osteopenia, adrenal suppression, growth suppression, etc; and

compare different anti‐leukotriene agents (synthesis inhibitor and receptor antagonists).

Feedback

Data entry error

Summary

I believe there may be an error in Table 1.13. The numbers for Ostrom 2005 are exactly the same as in Table 1.10.

Reply

Response from Cochrane Airways editorial base: Thank you for bringing this error to our attention. The duplicate data has been removed from analysis 1.10.1 and the text updated in the results section to reflect this change. The impact on the results of this analysis is negligible.

Contributors

Stephanie Weinreich

Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 December 2014 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback incorporated and typos corrected |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1999 Review first published: Issue 3, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 December 2010 | New search has been performed | New literature search run. |

| 31 December 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | 29 new studies included. Risk of bias has been updated across all studies. |

| 30 June 2008 | New search has been performed | Converted to new review format with added information. |

| 17 October 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Franco Di Salvio and Giselle Hicks for their participation in the assessment of methodology and data extraction, and diligent data entry in 2003 update. We are indebted to the following individuals who replied to our request for confirmation of methodology and data extraction, and graciously provided additional data whenever possible: Christopher Miller and Susan Shaffer from Astra‐Zeneca, USA in 2003; Ian Naya and Roger Metcalf for Astra‐Zeneca, Sweden; Theodore F Reiss and GP Noonan from Merck Frosst, USA; Frank Kanniess from the Pulmonary Research Institute, Germany; and Graziano Riccioni, Italy, Sept‐Oct 2003 . We are indebted to the Cochrane Airways Review Group, namely Toby Lasserson, Karen Blackhall, Dr Emma Welsh and Elizabeth Stovold for the literature search and ongoing support, and Paul Jones and Christopher Cates for their constructive comments. A special thanks to Mrs Anne James from the Consumer group for writing the original synopsis.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library) | Quarterly |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | Monthly |

Hand‐searches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

Asthma search

1. exp Asthma/

2. asthma$.mp.

3. (antiasthma$ or anti‐asthma$).mp.

4. Respiratory Sounds/

5. wheez$.mp.

6. Bronchial Spasm/

7. bronchospas$.mp.

8. (bronch$ adj3 spasm$).mp.

9. bronchoconstrict$.mp.

10. exp Bronchoconstriction/

11. (bronch$ adj3 constrict$).mp.

12. Bronchial Hyperreactivity/

13. Respiratory Hypersensitivity/

14. ((bronchial$ or respiratory or airway$ or lung$) adj3 (hypersensitiv$ or hyperreactiv$ or allerg$ or insufficiency)).mp.

15. ((dust or mite$) adj3 (allerg$ or hypersensitiv$)).mp.

16. or/1‐15

Filter to identify RCTs

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anti‐leukotriene (AL) vs. Inhaled glucocorticoids (in HFC‐BDP equivalent).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with at least one exacerbation requiring systemic steroids | 21 | 6077 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.17, 1.96] |

| 1.1 Paediatrics | 6 | 1662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.99, 1.86] |

| 1.2 Adults | 15 | 4415 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [1.12, 2.31] |

| 2 Patients with at least one exacerbation requiring hospital admission | 12 | 2715 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.33 [1.02, 10.94] |

| 2.1 Paediatrics | 4 | 558 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 73.98] |

| 2.2 Adults | 8 | 2157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.38 [0.94, 12.17] |

| 3 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 12 | 3020 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.15, ‐0.08] |

| 3.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 56 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.28 [‐0.69, 0.13] |

| 3.2 Adults | 11 | 2964 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.15, ‐0.08] |

| 4 Change from baseline FEV1( L) 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 8 | 1778 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.20, ‐0.04] |

| 4.1 Paediatrics | 2 | 179 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.13, 0.09] |

| 4.2 Adults | 6 | 1599 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.14 [‐0.24, ‐0.05] |

| 5 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks | 3 | 1178 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.22, ‐0.04] |

| 5.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 123 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.01 [‐0.14, 0.12] |

| 5.2 Adults | 2 | 1055 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.23, ‐0.11] |

| 6 Change from baseline FEV1 (L) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks | 2 | 1040 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 6.1 Paediatrics | 2 | 1040 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 7 FEV1 irrespective of time of treatment | 23 | 7016 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.14, ‐0.08] |

| 7.1 Paediatrics | 4 | 1398 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 7.2 Adults | 19 | 5618 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.16, ‐0.09] |

| 8 Responders (defined as change from baseline in FEV1 >= 7.5% | 1 | Odds Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Change from baseline FEV1 (%) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9.1 Adults | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 10 Change from baseline FEV1 (%) 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 2 | 603 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.70 [‐9.81, ‐1.59] |

| 10.1 Adults | 2 | 603 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.70 [‐9.81, ‐1.59] |

| 11 Change from baseline FEV1 (%) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks | 2 | 838 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐8.20 [‐10.85, ‐5.55] |

| 11.1 Adults | 2 | 838 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐8.20 [‐10.85, ‐5.55] |

| 12 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicted at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 2 | 219 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.58 [‐6.56, 1.40] |

| 12.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 183 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.54 [‐4.82, 3.74] |

| 12.2 Adults | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.6 [‐8.86, ‐0.34] |

| 13 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicated at 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 3 | 948 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.76 [‐5.01, ‐2.50] |

| 13.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 335 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.02 [‐9.45, ‐2.59] |

| 13.2 Adults | 2 | 613 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.41 [‐4.76, ‐2.06] |

| 14 Change from baseline FEV1 % of predicated at 36 ‐ 52 weeks | 3 | 1229 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.51 [‐7.14, 0.12] |

| 14.1 Paediatrics | 3 | 1229 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.51 [‐7.14, 0.12] |

| 15 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 8 | 1926 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐15.12 [‐20.80, ‐9.44] |

| 15.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 332 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.76 [‐13.43, ‐2.09] |

| 15.2 Adults | 7 | 1594 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐17.63 [‐22.56, ‐12.69] |

| 16 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 9 | 2601 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐19.07 [‐25.86, ‐12.27] |

| 16.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 335 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐16.9 [‐28.54, ‐5.26] |

| 16.2 Adults | 8 | 2266 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐19.57 [‐27.27, ‐11.87] |

| 17 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 24 ‐ 26 weeks | 3 | 1718 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐21.62 [‐40.19, ‐3.05] |

| 17.1 Adults | 3 | 1718 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐21.62 [‐40.19, ‐3.05] |

| 18 Change from baseline AM PEFR (L/min) at 36 ‐ 52 weeks | 3 | 1028 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.06 [‐10.58, 0.45] |

| 18.1 Adults | 3 | 1028 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.06 [‐10.58, 0.45] |

| 19 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 6 | 1925 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.08, 0.32] |

| 19.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 393 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.14, 0.26] |

| 19.2 Adults | 5 | 1532 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.11, 0.36] |

| 20 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 9 | 2650 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.18, 0.33] |

| 20.1 Paediatrics | 2 | 388 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.08, 0.48] |

| 20.2 Adults | 7 | 2262 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.16, 0.33] |

| 21 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 24 ‐ 26 weeks | 3 | 1719 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.02, 0.42] |

| 21.1 Adults | 3 | 1719 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.02, 0.42] |

| 22 Change from baseline daytime symptom scores at 36 ‐ 52 weeks | 2 | 582 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [‐0.02, 0.34] |

| 22.1 Paediatrics | 2 | 582 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [‐0.02, 0.34] |

| 23 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 4 ‐ 8 week | 3 | 798 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [‐0.02, 0.46] |

| 23.1 Adults | 3 | 798 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [‐0.02, 0.46] |

| 24 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 9 | 2916 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.11, 0.26] |

| 24.1 Adults | 9 | 2916 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.11, 0.26] |

| 25 Change from baseline night‐time awakenings at 24 ‐ 26 weeks | 2 | 1055 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.11, 0.35] |

| 25.1 Adults | 2 | 1055 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.11, 0.35] |

| 26 Change from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists at 4 ‐ 8 weeks | 10 | 3264 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.07, 0.34] |

| 26.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 393 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.22, 0.17] |

| 26.2 Adults | 9 | 2871 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.10, 0.38] |

| 27 Change from baseline mean daily use of β2‐agonists at 12 ‐ 16 weeks | 11 | 3367 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.17, 0.30] |

| 27.1 Paediatrics | 1 | 335 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.20, 0.23] |

| 27.2 Adults | 10 | 3032 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.19, 0.33] |