Abstract

Background

Although pharmacological and psychological interventions are both effective for major depression, antidepressant drugs remain the mainstay of treatment in primary and secondary care settings. During the last 20 years, antidepressant prescribing has risen dramatically in western countries, mainly because of the increasing consumption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and newer antidepressants, which have progressively become the most commonly prescribed antidepressants. Escitalopram is the pure S-enantiomer of the racemic citalopram.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of escitalopram in comparison with tricyclics, other SSRIs, heterocyclics and newer agents in the acute-phase treatment of major depression.

Search methods

Electronic databases were searched up to July 2008. Trial databases of drug-approving agencies were hand-searched for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials comparing escitalopram against any other antidepressant (including non-conventional agents such as hypericum) for patients with major depressive disorder (regardless of the diagnostic criteria used).

Data collection and analysis

Data were entered by two review authors (double data entry). Responders and remitters to treatment were calculated on an intention-to-treat basis. For dichotomous data, odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous data were analysed using standardised mean differences (with 95% CI) using the random effects model.

Main results

Fourteen trials compared escitalopram with another SSRI and eight compared escitalopram with a newer antidepressive agent (venlafaxine, bupropion and duloxetine). Escitalopram was shown to be significantly more effective than citalopram in achieving acute response (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.87). Escitalopram was also more effective than citalopram in terms of remission (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.93). Significantly fewer patients allocated to escitalopram withdrew from trials compared with patients allocated to duloxetine, for discontinuation due to any cause (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.99).

Authors’ conclusions

Some statistically significant differences favouring escitalopram over other antidepressive agents for the acute phase treatment of major depression were found, in terms of efficacy (citalopram and fluoxetine) and acceptability (duloxetine). There is insufficient evidence to detect a difference between escitalopram and other antidepressants in early response to treatment (after two weeks of treatment). Cost-effectiveness information is also needed in the field of antidepressant trials. Furthermore, as with most standard systematic reviews, the findings rely on evidence from direct comparisons. The potential for overestimation of treatment effect due to sponsorship bias should also be borne in mind.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Antidepressive Agents [*therapeutic use], Citalopram [*therapeutic use], Depression [*drug therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors [*therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Major depression is generally diagnosed when a persistent and unreactive low mood and loss of all interest and pleasure are accompanied by a range of symptoms including appetite loss, insomnia, fatigue, loss of energy, poor concentration, psychomotor symptoms, inappropriate guilt and morbid thoughts of death (APA 1994). It was the third leading cause of burden among all diseases in the year 2002 and it is expected to show a rising trend during the coming 20 years (Murray 1997). This condition is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, loss of functioning and productivity, and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload (NICE 2007).

Description of the intervention

Although pharmacological and psychological interventions are both effective for major depression, in primary and secondary care settings antidepressant drugs remain the mainstay of treatment (APA 2000; Ellis 2004; NICE 2007) (see below for other references to the relevant evidence). Amongst antidepressants many different agents are available, including tricyclics (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, such as venlafaxine, duloxetine and milnacipran), and other newer agents (mirtazapine, reboxetine, bupropion). During the last 20 years, consumption of antidepressant has risen dramatically in western countries, mainly because of the increasing consumption of SSRIs and newer antidepressants, which have progressively become the most commonly prescribed antidepressants (Ciuna 2004; Guaiana 2005). SSRIs are generally better tolerated than TCAs (Barbui 2000), and there is evidence of similar efficacy (Anderson 2000; Geddes 2000; Williams 2000). However, head-to-head comparison have provided contrasting findings. Amitriptyline, for example, may have the edge over SSRIs in terms of efficacy (Guaiana 2003), and individual SSRIs and SNRIs may differ in terms of efficacy and tolerability (Puech 1997; Smith 2002; Hansen 2005; Cipriani 2006).

Escitalopram is the pure S-enantiomer of the racemic citalopram. As for all other antidepressants belonging to the SSRIs class, the mechanism of antidepressant action of escitalopram is presumed to be linked to potentiation of serotonergic activity in the central nervous system resulting from its inhibition of neuronal re-uptake of serotonin. Escitalopram is at least 100 fold more potent than the R-enantiomer with respect to inhibition of 5-HT reuptake and inhibition of 5-HT neuronal firing rate. Escitalopram has no or very low affinity for other receptors (alpha- and beta-adrenergic, dopamine (D1-5), histamine (H1-3), muscarinic (M1-5), and benzodiazepine receptors). The single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of escitalopram are linear and dose-proportional in a dose range of 10 to 30 mg/day. In vitro studies indicated that CYP3A4 and −2C19 are the primary enzymes involved in the metabolism of escitalopram, however these studies did not reveal an inhibitory effect of escitalopram on CYP2D6.

How the intervention might work

The efficacy of escitalopram as a treatment for major depressive disorder was established in three, 8-week, placebo-controlled studies conducted in outpatients between 18 and 65 years of age who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (www.fda.gov). The primary outcome in all three studies was change from baseline to endpoint in the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979). The 10 mg/day and 20 mg/day escitalopram treatment groups showed significantly greater mean improvement compared to placebo on the MADRS. Analyses of the relationship between treatment outcome and age, gender, and race did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of these patient characteristics. Among the 715 depressed patients who received escitalopram in placebo-controlled trials, 6% discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, compared to 2% of 592 patients receiving placebo. The rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients assigned to a fixed dose of 20 mg/day escitalopram was 10%, which was significantly different from the rate of discontinuation for adverse events in patients receiving 10 mg/day escitalopram (4%) and placebo (3%). The most commonly observed adverse events in escitalopram patients (incidence of approximately 5% or greater and approximately twice the incidence as in placebo patients) were insomnia, ejaculation disorder (primarily ejaculatory delay), nausea, increased sweating, fatigue, and somnolence.

Why it is important to do this review

To shed light on the field of antidepressant trials and treatment of major depressive disorder, a group of researchers agreed to join forces under the rubric of the Meta-Analyses of New Generation Antidepressants Study Group (MANGA Study Group) to systematically review all available evidence for each specific newer antidepressant. As of October 2008, we have completed an individual review for fluoxetine (Cipriani 2005), and published the protocols for venlafaxine (Cipriani 2007a), sertraline (Malvini 2006), fluvoxamine (Omori 2006), citalopram (Imperadore 2007), duloxetine (Nose 2007), milnacipran (Nakagawa 2007), paroxetine (Cipriani 2007b) and mirtazapine (Watanabe 2006). Thus, the aim of the present review is to assess the evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in comparison with TCAs, heterocyclics, other SSRIs and newer antidepressants, including non-conventional agents such as herbal products like hypericum (Linde 2008), in the acute-phase treatment of major depression.

OBJECTIVES

To determine the efficacy of escitalopram in comparison with other antidepressive agents for depression in alleviating the acute symptoms of major depressive disorder.

To investigate the acceptability of escitalopram in comparison with other antidepressive agents for depression.

To investigate the adverse effects of escitalopram in comparison with other antidepressive agents for depression.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials were included. Quasi-randomised trials, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded.

Types of participants

Patients aged 18 or older, of both sexes, with a primary diagnosis of major depression. Studies adopting any standardised criteria to define patients suffering from unipolar major depression were included. Studies from the 1990s onwards were likely to have used DSM-IV (APA 1994) or ICD-10 (WHO 1992) criteria. Earlier studies may had used ICD-9 (WHO 1978), DSM-III (APA 1980) / DSM-III-R (APA 1987) or other diagnostic systems. ICD-9 is not operationalised criteria, because it has only disease names and no diagnostic criteria, so studies using ICD-9 were excluded. However, studies using Feighner criteria or Research Diagnostic Criteria were included. Studies in which less than 20% of the participants might be suffering from bipolar depression were included, but the validity of this decision was examined in a sensitivity analysis. A concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder was not considered as an exclusion criterion. A concurrent primary diagnosis of Axis I or II disorders was an exclusion criterion. Antidepressant trials in depressive patients with a serious concomitant medical illness were also excluded.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Escitalopram (as monotherapy). No restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity and duration were applied.

Comparator interventions

All other antidepressive agents in the treatment of acute depression, including:

conventional tricyclic ADs (TCAs)

heterocyclic antidepressants (e.g. maprotiline)

SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline)

newer antidepressants (SNRIs such as venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran; MAOIs or newer agents such as mirtazapine, bupropion, reboxetine; and non-conventional ADs, such as herbal products - e.g. hypericum).

No restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity and duration were applied.

Other types of psychopharmacological agent such as anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics or mood-stabilizers were excluded. Trials in which escitalopram was used as an augmentation strategy were also excluded

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Number of patients who responded to treatment, showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) (Hamilton 1960) or MADRS (Montgomery 1979), or any other depression scale, or “much or very much improved” (score 1 or 2) on CGI-Improvement (Guy 1970). All response rates were calculated out of the total number of randomised patients. Where more than one criterion was provided, we preferred the HAM-D for judging response. We used the HAM-D whenever possible, even when we needed to impute SDs or response rates according to the procedures described in the Methods section below.

When studies reported response rates at various time points of the trial, we decided a priori to subdivide the treatment indices as follows:

Early response: between 1 and 4 weeks, the time point closest to 2 weeks was given preference.

Acute phase treatment response: between 6 and 12 weeks, the time point given in the original study as the study endpoint was given preference.

Follow-up response: between 4 and 6 months, the time point closest to 24 weeks was given preference.

The acute phase treatment response, i.e. between 6 and 12 weeks, was our primary outcome of interest.

Secondary outcomes

Number of patients who achieved remission. The cut-off point for remission was set a priori (i) at 7 or less on the 17-item HAM-D and at 8 or less for all the other longer versions of HAM-D, or (ii) at 12 or less on the MADRS (Zimmerman 2004), or (iii) “not ill or borderline mentally ill” (score 1 or 2) on CGI-Severity (Guy 1970). All remission rates was calculated out of the total number of randomised patients. Where two or more were provided, we preferred the HAM-D for judging remission.

Change scores from baseline to the time point in question (early response, acute phase response, or follow-up response as defined above) on HAM-D, or MADRS, or any other depression scale. We applied a looser form of ITT analysis, whereby all the patients with at least one post-baseline measurement were represented by their last observations carried forward.

Social adjustment, social functioning, including the Global Assessment of Function (Luborsky 1962) scores

Health-related quality of life: we limited ourselves to SF-12/SF-36 (Ware 1993), HoNOS (Wing 1994) and WHOQOL (WHOQOL Group 1998).

Costs to health care services

-

Acceptability

Acceptability was evaluated using the following outcome measures:- Number of patients who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients - Total drop out rate

- Number of patients who dropped out due to inefficacy during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients

-

-Drop out rates due to inefficacy

-

-

- Number of patients who dropped out due to side effects during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients

-

-Drop out rates due to side effects.

-

-

Tolerability

Tolerability was evaluated using the following outcome measures:

Total number of patients experiencing at least some side effects.

- Total number of patients experiencing the following specific side effects were sought for:

- Agitation/anxiety

- Constipation

- Diarrhoea

- Dry mouth

- Hypotension

- Insomnia

- Nausea

- Sleepiness/drowsiness

- Urination problems

- Vomiting

- Deaths, suicide and suicidality

In order not to miss any relatively rare or unexpected yet important side effects, in the data extraction phase, we collected all side effects data reported in the literature and discussed ways to summarise them post hoc.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) methods used in reviews.

Electronic Databases

CCDANCTR-Studies were searched using the following search strategy:

Diagnosis = Depress* or Dysthymi* or “Adjustment Disorder*” or “Mood Disorder*” or “Affective Disorder” or “Affective Symptoms” and Intervention = Escitalopram

CCDANCTR-References were searched using the following search strategy:

Keyword = Depress* or Dysthymi* or “Adjustment Disorder*” or “Mood Disorder*” or “Affective Disorder” or “Affective Symptoms” and Free-Text = Escitalopram

An additional Medline search was carried out (update: July 2008). Trial databases of the following drug-approving agencies - the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK, the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) in the EU, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia) and ongoing trial registers (clinicaltrials.gov in the USA, ISRCTN and National Research Register in the UK, Nederlands Trial Register in the Netherlands, EUDRACT in the EU, UMIN-CTR in Japan and the Australian Clinical Trials Registry in Australia) were searched for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials (update: July 2008).

Searching other resources

1) Handsearches

Appropriate journals and conference proceedings relating to escitalopram treatment for depression were hand-searched and incorporated into the CCDANCTR databases.

2) Personal communication

Pharmaceutical companies and experts in this field were asked if they knew of any study which met the inclusion criteria of this review.

3) Reference checking

Reference lists of the included studies, previous systematic reviews and major textbooks of affective disorder written in English were checked for published reports and citations of unpublished research. The references of all included studies were checked via Science Citation Index for articles which had cited the included study.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Studies relating to escitalopram generated by the electronic search of CCDANCTR-Studies were scanned by one review author (HMG). Those studies that met the following criteria constituted the preliminary list and their full texts were retrieved:.

The rough inclusion criteria were:

Randomised trial

Comparing escitalopram against any other antidepressant

Patients with major depression, regardless of the diagnostic criteria used.

Studies relating to escitalopram generated by the search strategies of CCDANCTR-References and the other complementary searches were checked independently by the CCDAN Trials Search Coordinator (HMG), who is an author of this review, and another review author (AC, AS or CS) to see if they met the rough inclusion criteria, firstly based on the title and abstracts. All the studies rated as possible candidates by either of the two reviewers were added to the preliminary list and the full texts were retrieved. All the full text articles in this preliminary list was then assessed by two review authors (AC, AS or CS) independently to see if they met the strict inclusion criteria. If the raters disagreed, the final rating were made by consensus with the involvement (if necessary) of another member of the review group. Non-congruence in selection of trials was reported as percentage disagreement. Considerable care was taken to exclude duplicate publications.

Data extraction and management

One review author (CS) first extracted data concerning participant characteristics (age, sex, depression diagnosis, comorbidity, depression severity, antidepressant treatment history for the index episode, study setting), intervention details (intended dosage range, mean daily dosage actually prescribed, co-intervention if any, escitalopram as investigational drug or as comparator drug, sponsorship) and outcome measures of interest from the included studies. The results were compared with those in the completed reviews of individual antidepressants in the Cochrane Library. If there were any discrepancies, a second review author (AC) intervened and the agreed-upon results were used in the review as well as fed back to the authors of the completed reviews.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool as recommended in RevMan 5.0.0. This instrument consists of six items. Two of the items assess the strength of the randomisation process in preventing selection bias in the assignment of participants to interventions: adequacy of sequence generation and allocation concealment. The third item (blinding) assesses the influence of performance bias on the study results. The fourth item assesses the likelihood of incomplete outcome data, which raise the possibility of bias in effect estimates. The fifth item assesses selective reporting, the tendency to preferentially report statistically significant outcomes. It requires a comparison of published data with trial protocols, when such are available. The final item refers to other sources of bias that are relevant in certain circumstances, for example, in relation to trial design (methodologic issues such as those related to crossover designs and early trial termination) or setting.

Two review authors (AC, CB) assessed risk of bias in each trial independently, in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). Where inadequate details of allocation concealment and other characteristics of trials were provided, the trial authors were contacted in order to obtain further information. If the raters disagreed the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement (if necessary) of another member of the review group. The ratings were also compared with those in the completed reviews of individual antidepressants in the Cochrane Library. If here were any discrepancies, they were fed back to the authors of the completed reviews.

Measures of treatment effect

Data were checked and entered into Review Manager 5 software by two review authors (AC, CS) (double data entry). For dichotomous, or event-like data, odds ratios (OR) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Continuous data were analysed using weighted mean differences (with 95% confidence intervals) or standardised mean differences (where different measurement scales are used) using the random effects model.

Unit of analysis issues

For trials which had a crossover design only results from the first randomisation period were considered. If the trial was a three (or more)-armed trial involving a placebo arm, the data were extracted from the placebo arm as well.

Dealing with missing data

Responders and remitters to treatment were calculated on the intention-to-treat (ITT) basis: drop-outs were always included in this analysis. Where participants had withdraw from the trial before the endpoint, it was assumed they would have experienced the negative outcome by the end of the trial (e.g. failure to respond to treatment). When there were missing data and the method of “last observation carried forward” (LOCF) had been used to do an ITT analysis, then the LOCF data were used, with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced. When dichotomous or continuous outcomes were not reported, trial authors were asked to supply the data.

When only the SE or t-statistics or p values were reported, SDs were calculated according to Altman (Altman 1996). In the absence of supplemental data from the authors, the SDs of the HAM-D (or any other depression scale) and response/remission rates were calculated according to validated imputation methods (Furukawa 2005; Furukawa 2006). We examined the validity of these imputations in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Skewed data and non-quantitative data were presented descriptively. An outcome whose minimum score is zero could be considered skewed when the mean was smaller than twice the SD. Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by the I-squared statistic (Higgins 2003) (I-squared equal to or more than 50% was considered indicative of heterogeneity) and by visual inspection of forest plots.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plot analysis was performed to check for existence of small study effects, including publication bias.

Data synthesis

The primary analysis used a random effects model OR, which had the highest generalisability in our empirical examination of summary effect measures for meta-analyses (Furukawa 2002a). The robustness of this summary measure was routinely examined by checking the fixed effect model OR and the random effects model risk ratio (RR). Material differences between the models were reported. Fixed effect analyses were done routinely for the continuous outcomes as well, to investigate the effect of the choice of method on the estimates. Material differences between the models were reported.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were performed and interpreted with caution because multiple analyses can lead to false positive conclusions (Oxman 1992). However, we performed the following subgroup analyses, where possible, for the following a priori reasons:

Escitalopram dosing (fixed low dosage, fixed standard dosage, fixed high dosage; flexible low dosage, flexible standard dosage, flexible high dosage), because there was evidence to suspect that low dosage antidepressant might be associated with better outcomes both in terms of effectiveness and side effects than standard or high dosage antidepressants (Bollini 1999; Furukawa 2002b) and also because fixed versus flexible dosing schedule might affect estimates of treatment effectiveness (Khan 2003). In the case of escitalopram, based on the Defined Daily Dosage by World Health Organisation (WHO), low dosage referred to <10, standard dosage to >10 but <20, and high dosage to >20 mg/day.

Comparator dosing (low effective range, medium to high effective range), as it was easy to imagine that there were greater chances of completing the study on the experimental drug than on the comparator drug that was increased to the maximum dosage.

Depression severity (severe major depression, moderate/mild major depression).

Treatment settings (psychiatric inpatients, psychiatric outpatients, primary care).

Elderly patients (>65 years of age), separately from other adult patients.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses were planned a priori. By limiting included studies to those with higher quality, we examined if the results changed, and checked for the robustness of the observed findings.

Excluding trials with unclear concealment of random allocation and/or unclear double blinding.

Excluding trials whose drop out rate was greater than 20%.

Performing the worst case scenario ITT (all the patients in the experimental group experience the negative outcome and all those allocated to the comparison group experience the positive outcome) and the best case scenario ITT (all the patients in the experimental group experience the positive outcome and all those allocated to the comparison group experience the negative outcome).

Excluding trials for which the response rates had to be calculated based on the imputation method (Furukawa 2005) and those for which the SD had to be borrowed from other trials (Furukawa 2006).

Examination of “wish bias” (also called “optimism bias”) by comparing escitalopram as investigational drug vs escitalopram as comparator, as there was evidence to suspect that a new antidepressant might perform worse when used as a comparator than when used as an experimental agent (Barbui 2004).

Excluding studies funded by the pharmaceutical company marketing escitalopram. This sensitivity analysis was particularly important in view of the recent repeated findings that funding strongly affects outcomes of research studies (Als-Nielsen 2003; Bhandari 2004; Lexchin 2003; Montgomery 2004; Perlis 2005; Procyshyn 2004) and because industry sponsorship and authorship of clinical trials were increasing over 20 years (Buchkowsky 2004).

If subgroups within any of the subgroup or sensitivity analyses turned out to be significantly different from one another, we ran meta-regression for exploratory analyses of additive or multiplicative influences of the variables in question. Our routine application of random effects and fixed effect models as well as our secondary outcomes of remission rates and continuous severity measures may be considered additional forms of sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

The search yielded 52 references of potentially eligible studies. After exclusion of papers that were not relevant (because they mainly were non-randomised studies or reviews), 19 randomised controlled trials were included in the present review. Three further randomised controlled trials were found in the web-based clinical trial register of the pharmaceutical industry manufacturing escitalopram and were included in the pool of included studies. Therefore, a total of 22 trials were included in the review.

In the presentation of the following analyses, a post-hoc decision was made to present all SSRIs (with sub-totals) together in one group, and SNRIs and newer antidepressant agents (without subtotals) together in a second group (see graphs). Fourteen trials (64%) compared escitalopram with another SSRI and eight (36%) compared escitalopram with a newer antidepressant (venlafaxine, bupropion and duloxetine). Neither trials comparing escitalopram with TCAs or MAOIs nor cross-over design studies were retrieved by the comprehensive search. In this review all studies were multicentre, randomised, double-blind trials (nine were three-arm, placebo-controlled trials).

Included studies

Design

Length of the studies

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

In 11 studies the follow-up was 8 weeks (Alexopoulos 2004; Baldwin 2006; Burke 2002; Kasper 2005; Kennedy 2005; Lepola 2003; Mao 2008; Moore 2005; SCT-MD-02; SCT-MD-09; Ventura 2007). One study was a 6-week trial (Yevtushenko 2007) and in two studies the follow-up lasted up to 24 weeks (Boulenger 2006; Colonna 2005).

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

Seven studies were 8-week trials (Bielski 2004; Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Khan 2007; Montgomery 2004; Nierenberg 2007; SCT-MD-35) and one study was a 24-week trial (Wade 2007).

Sample size

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

The mean of participants per study was 280.8 (SD 103.9), with a minimum sample size of 30 (SCT-MD-09) and a maximum of 459 (Boulenger 2006).

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

The mean of participants was 307.1 (SD 101.3), ranging between 202 (Bielski 2004) and 547 (Nierenberg 2007).

Setting

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

In 11 studies the participants were outpatients (Alexopoulos 2004; Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006; Burke 2002; Colonna 2005; Kennedy 2005; Moore 2005; SCT-MD-02; SCT-MD-09; Ventura 2007; Yevtushenko 2007). In one study (Lepola 2003) participants were recruited in primary care. In two studies (Kasper 2005; Mao 2008) both outpatients and inpatients were eligible. In Kasper 2005, patients were recruited both in general practice and specialist settings.

Escitalopram versus other antidepressants

In 7 studies the participants were outpatients (Bielski 2004; Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Khan 2007; Nierenberg 2007; SCT-MD-35; Wade 2007). In Montgomery 2004 patients were recruited in primary care.

Participants

Age

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

In eight studies patients over 65 years were excluded (Alexopoulos 2004; Baldwin 2006; Burke 2002; Colonna 2005; Lepola 2003; Mao 2008; SCT-MD-09; Yevtushenko 2007). Five studies included patients over 65 years (Boulenger 2006; Kennedy 2005; Moore 2005; SCT-MD-02; Ventura 2007). One study (Kasper 2005) included only elderly patients (over 65 years).

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

In two studies patients over 65 years were excluded (Bielski 2004; Wade 2007). Four studies included patients over 65 years (Khan 2007; Montgomery 2004; Nierenberg 2007; SCT-MD-35). In two studies age range was not specified (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927)).

Diagnosis

All the studies enrolled patients suffering from DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder.

Interventions

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

In six studies escitalopram was compared with citalopram (Burke 2002; Colonna 2005; Lepola 2003; Moore 2005; SCT-MD-02; Yevtushenko 2007), in four with fluoxetine (Kasper 2005; Kennedy 2005; Mao 2008; SCT-MD-09), in two with paroxetine (Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006) and in the remaining two with sertraline (Alexopoulos 2004; Ventura 2007). Five studies included a placebo arm (Alexopoulos 2004; Burke 2002; Kasper 2005; Lepola 2003; SCT-MD-02). One study (Burke 2002) presented a comparison between four arms: escitalopram 10mg/day, escitalopram 20mg/day, citalopram and placebo.

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

Three studies compared escitalopram with bupropion XR (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); SCT-MD-35), three with duloxetine (Khan 2007; Nierenberg 2007; Wade 2007) and two with venlafaxine XR (Bielski 2004; Montgomery 2004). Four studies included a placebo arm (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Nierenberg 2007; SCT-MD-35). One study (SCT-MD-35) presented a comparison between four arms: escitalopram 4mg/day, bupropion XR 150mg/day, placebo and a combination of escitalopram 4mg/day and bupropion XR 150mg/day.

Dosage of study drugs

In 21 out of 22 studies the dosage of escitalopram was within the therapeutic dosage (10 to 20 mg/day). In one study (SCT-MD-35) the escitalopram dosage was set at 4 mg/day (fixed dose). Eleven trials used a fixed- and the remaining eleven a flexible-dosage regimen. The use of a fixed- or a flexible-dose regimen was consistent among comparisons within the same study in the great majority of included trials. However, in three out of 22 studies one of the two compounds used a fixed-dose while the other used a flexible-dose design (Burke 2002; Khan 2007; Ventura 2007).

Primary Outcomes

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

The primary outcome used in the great majority of studies was change from baseline on MADRS. One study (Mao 2008) used the change on the HAM-D-17 total score and another trial (SCT-MD-09) evaluated the effects of escitalopram and fluoxetine on sleep in depressed patients using the number of awakenings (polysomnogram) as the primary outcome. The latter study lasted only five weeks, did not evaluate efficacy and has been included in the present review only for early discontinuation and tolerability outcomes (side-effect profile).

Escitalopram versus other antidepressants

Five studies used the change from baseline on MADRS (Bielski 2004; Khan 2007; Montgomery 2004; SCT-MD-35; Wade 2007) as the primary outcome and one used change on HAMD-17 (Nierenberg 2007). In studies by Clayton (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927)) sexual functioning was considered the primary outcome and depression was rated as mean change on HAMD-17.

Response Rate

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

In nine studies a decrease from baseline to endpoint of at least 50% in rating scale total score (either on MADRS or on HAM-D) was used to define “response” (Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006; Burke 2002; Colonna 2005; Kasper 2005; Lepola 2003; Mao 2008; Moore 2005; Ventura 2007). The four remaining studies (Alexopoulos 2004; Kennedy 2005; SCT-MD-02; SCT-MD-09) provided only continuous data and therefore response rates were imputed (see Methods).

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

In four studies, a decrease from baseline to endpoint of at least 50% in MADRS total score was used to define “response” (Bielski 2004; Khan 2007; Montgomery 2004; Wade 2007). In three studies a decrease from baseline to endpoint of at least 50% in HAMD-17 total score was used for defining “response” (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Nierenberg 2007). In one study (SCT-MD-35) only continuous data were available and therefore response rate was imputed (see Methods).

Remission Rate

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

Six studies used MADRS to assess remission rate (Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006; Colonna 2005; Kasper 2005; Lepola 2003; Moore 2005). One study used HAMD-17 (Ventura 2007). Five studies did not report remission rate (Alexopoulos 2004; Burke 2002; Kennedy 2005; SCT-MD-02; SCT-MD-09). However, considering that continuous outcomes were available, remission rates were imputed (see Methods)

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

Six studies used HAMD-17 (Bielski 2004; Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Khan 2007; Nierenberg 2007; Wade 2007) and one used MADRS (Montgomery 2004) to assess remission rate. One study (SCT-MD-35) did not report dichotomous data remission rate, so remission rate was imputed using continuous outcomes (see Methods)

Sponsorship

Escitalopram versus other SSRIs

All the studies were sponsored by the drug company marketing escitalopram.

Escitalopram versus newer antidepressants

Five studies were sponsored by the drug company marketing escitalopram (Bielski 2004; Khan 2007; Montgomery 2004; SCT-MD-35; Wade 2007). Two studies were sponsored by the drug company marketing bupropion XR (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927)). One study was sponsored by the drug company marketing duloxetine (Nierenberg 2007).

Excluded studies

Thirty-three references of potentially eligible studies were excluded after checking titles and abstracts. Of those, 21 were reviews, nine were non-randomised studies and three were duplicates.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a graphical summary of methodological quality for the 22 included studies, based on the six risk of bias domains.

Figure 1. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Only four studies reported sufficient details on allocation concealment (Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006; Colonna 2005; Wade 2007).

Blinding

All studies were reported to be double-blind trials, however only five studies reported sufficient details on blinding (Baldwin 2006; Boulenger 2006; Colonna 2005; Wade 2007; Yevtushenko 2007)

Incomplete outcome data

Only three studies reported incomplete outcome data (Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); SCT-MD-09).

Selective reporting

Only eight studies were indicated to be free from selective reporting (Alexopoulos 2004; Bielski 2004; Boulenger 2006; Clayton (AK130926); Clayton (AK130927); Khan 2007; Ventura 2007; Yevtushenko 2007).

Other potential sources of bias

The large majority of included studies were sponsored by the manufacturer of escitalopram.

Effects of interventions

Some statistically significant differences in efficacy, acceptability and tolerability were found and details are listed below. The results are reported comparison by comparison (dividing SSRIs from newer antidepressants) and the forest plots are organised according to the relevance of outcomes, as reported in the review protocol. For adverse events, all the information about adverse events specified in the review protocol are reported (either statistically or non-statistically significant). However, remaining adverse events are only reported when statistically significant (non-statistically significant results about adverse events are presented in Table 1).

Table 1. Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Study | Escitalopram | Comparator | Odds Ratio, Random [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Total | Events | Total | |||

| Escitalopram versus citalopram | ||||||

| Accidental overdose | Burke 2002 | 0 | 244 | 1 | 125 | 0.17 [0.01, 4.20] |

| Aggressive behaviour | Moore 2005 | 1 | 142 | 0 | 152 | 3.23 [0.13, 80.02] |

| Anaphylaxis | Burke 2002 | 1 | 244 | 0 | 125 | 1.55 [0.06, 38.23] |

| Anorexia | Yevtushenko 2007 | 0 | 108 | 1 | 108 | 0.33 [0.01, 8.20] |

| Asthenia | Moore 2005 | 2 | 142 | 2 | 152 | 1.07 [0.15, 7.71] |

| Bronchitis | Colonna 2005, Lepola 2003 | 13 | 330 | 11 | 342 | 1.24 [0.54, 2.83] |

| Coma | Burke 2002 | 0 | 244 | 1 | 125 | 0.17 [0.01, 4.20] |

| Concentration decrease | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Death fetal | Lepola 2003 | 0 | 116 | 1 | 111 | 0.32 [0.01, 7.84] |

| Dehydration | SCT-MD-02 | 0 | 125 | 1 | 123 | 0.33 [0.01, 8.06] |

| Depression | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Dermatological problems | Moore 2005, Yevtushenko 2007 | 1 | 250 | 3 | 260 | 0.44 [0.06, 3.02] |

| Disease Of Liver And Hepatic Duct | SCT-MD-02 | 0 | 125 | 1 | 123 | 0.33 [0.01, 8.06] |

| Dizziness | Burke 2002, Moore 2005, SCT-MD-02 | 31 | 511 | 15 | 400 | 1.43 [0.58, 3.49] |

| Dyspepsia | Yevtushenko 2007 | 0 | 108 | 1 | 108 | 0.33 [0.01, 8.20] |

| Enuresis | Moore 2005 | 1 | 142 | 0 | 152 | 3.23 [0.13, 80.02] |

| Forgetfulness | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 2 | 152 | 0.21 [0.01, 4.44] |

| Hot flashes | Moore 2005 | 1 | 142 | 0 | 152 | 3.23 [0.13, 80.02] |

| Inflicted injury | Burke 2002 | 8 | 244 | 3 | 125 | 1.38 [0.36, 5.29] |

| Non-accidental overdose | SCT-MD-02 | 1 | 125 | 0 | 123 | 2.98 [0.12, 73.76] |

| Ophtalmological problems | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 2 | 152 | 0.21 [0.01, 4.44] |

| Oppression | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Palpitation | Moore 2005 | 1 | 142 | 0 | 152 | 3.23 [0.13, 80.02] |

| Panic attack | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Pelvic inflammation | Lepola 2003 | 1 | 116 | 0 | 111 | 2.90 [0.12, 71.85] |

| Pharyngitis | Burke 2002, Lepola 2003, Moore 2005 | 18 | 541 | 12 | 437 | 0.92 [0.41, 2.06] |

| Pregnancy unintended | Lepola 2003 | 1 | 116 | 0 | 111 | 2.90 [0.12, 71.85] |

| Rhinitis | Burke 2002, Colonna 2005, Lepola 2003, SCT-MD-02 | 46 | 699 | 33 | 590 | 1.19 [0.73, 1.91] |

| Sexual problems | Burke 2002, Lepola 2003, SCT-MD-02, Yevtushenko 2007 | 19 | 283 | 15 | 267 | 1.14 [0.53, 2.44] |

| Sinusitis | Lepola 2003 | 6 | 155 | 4 | 160 | 1.57 [0.43, 5.68] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Burke 2002, Lepola 2003, SCT-MD-02 | 6 | 524 | 4 | 408 | 1.12 [0.31, 4.08] |

| Tachycardia | SCT-MD-02 | 1 | 125 | 0 | 123 | 2.98 [0.12, 73.76] |

| Tinnitus | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Tremor | Moore 2005 | 3 | 142 | 0 | 152 | 7.65 [0.39, 149.47] |

| Trismus | Moore 2005 | 0 | 142 | 1 | 152 | 0.35 [0.01, 8.77] |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Burke 2002, Lepola 2003, SCT-MD-02 | 31 | 524 | 16 | 408 | 1.59 [0.85, 2.98] |

| Weight gain | Colonna 2005, Moore 2005 | 4 | 317 | 14 | 334 | 0.38 [0.06, 2.37] |

| Escitalopram versus bupropion XR | ||||||

| Accidental overdose | Clayton (AK130926) | 0 | 143 | 1 | 135 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.74] |

| Decreased appetite | Clayton (AK130927) | 13 | 138 | 9 | 141 | 1.53 [0.63, 3.69] |

| Disease Of Liver And Hepatic Duct | Clayton (AK130927) , SCT-MD-35 | 2 | 269 | 0 | 275 | 3.09 [0.32, 29.89] |

| DIzziness | Clayton (AK130926) , Clayton (AK130927) | 15 | 281 | 18 | 276 | 0.84 [0.33, 2.12] |

| Dyspepsia | Clayton (AK130926) | 5 | 143 | 5 | 135 | 0.94 [0.27, 3.33] |

| Flatulence | Clayton (AK130926) | 8 | 143 | 4 | 135 | 1.94 [0.57, 6.60] |

| Irritability | Clayton (AK130926) , Clayton (AK130927) | 3 | 281 | 14 | 276 | 0.26 [0.06, 1.04] |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | SCT-MD-35 | 10 | 131 | 9 | 134 | 1.15 [0.45, 2.92] |

| Nasal congestion | Clayton (AK130926), Clayton (AK130927) | 11 | 281 | 6 | 276 | 1.86 [0.68, 5.11] |

| Non-accidental overdose | Clayton (AK130927) | 1 | 138 | 0 | 141 | 3.09 [0.12, 76.44] |

| Palpitation | Clayton (AK130926) | 3 | 143 | 4 | 135 | 0.70 [0.15, 3.20] |

| Pharyngitis | Clayton (AK130927) | 7 | 138 | 9 | 141 | 0.78 [0.28, 2.17] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Clayton (AK130926) , Clayton (AK130927) , SCT-MD-35 | 5 | 410 | 5 | 412 | 0.95 [0.24, 3.72] |

| Tooth ache | Clayton (AK130926) | 3 | 143 | 2 | 135 | 1.43 [0.23, 8.66] |

| Tremor | Clayton (AK130926) | 3 | 143 | 6 | 135 | 0.46 [0.11, 1.88] |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Clayton (AK130926) , SCT-MD-35 | 20 | 274 | 14 | 269 | 1.45 [0.68, 3.08] |

| Escitalopram versus duloxetine | ||||||

| Accidental overdose | Khan 2007 | 0 | 137 | 1 | 133 | 0.32 [0.01, 7.96] |

| Chest pressure | Khan 2007 | 0 | 137 | 1 | 133 | 0.32 [0.01, 7.96] |

| Decreased appetite | Nierenberg 2007 | 13 | 274 | 22 | 273 | 0.57 [0.28, 1.15] |

| Depression | Khan 2007 | 0 | 137 | 2 | 133 | 0.19 [0.01, 4.02] |

| Dizziness | Khan 2007, Nierenberg 2007, Wade 2007 | 39 | 554 | 64 | 557 | 0.59 [0.39, 0.90] |

| Dyspepsia | Wade 2007 | 9 | 143 | 4 | 151 | 2.47 [0.74, 8.20] |

| Hypertension | Khan 2007 | 0 | 137 | 1 | 133 | 0.32 [0.01, 7.96] |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | Khan 2007 | 18 | 137 | 12 | 133 | 1.53 [0.70, 3.30] |

| Pharyngitis | Wade 2007 | 15 | 143 | 11 | 151 | 1.49 [0.66, 3.37] |

| Sexual problems | Khan 2007 | 5 | 56 | 7 | 48 | 0.57 [0.17, 1.94] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Khan 2007, Nierenberg 2007 | 4 | 411 | 9 | 406 | 0.45 [0.07, 2.80] |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Khan 2007, Nierenberg 2007 | 57 | 411 | 48 | 406 | 1.21 [0.79, 1.85] |

| Escitalopram versus fluoxetine | ||||||

| Anorexia | Kasper 2005 | 2 | 173 | 4 | 164 | 0.47 [0.08, 2.59] |

| Depression | Kasper 2005 | 2 | 173 | 4 | 164 | 0.47 [0.08, 2.59] |

| Dermatological problems | SCT-MD-09 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 14 | 1.38 [0.20, 9.77] |

| Disease Of Liver And Hepatic Duct | Mao 2008 | 2 | 123 | 6 | 117 | 0.31 [0.06, 1.55] |

| DIzziness | Kasper 2005, Kennedy 2005, Mao 2008 | 20 | 394 | 22 | 380 | 0.88 [0.46, 1.67] |

| Dyspepsia | Kasper 2005 | 4 | 173 | 7 | 164 | 0.53 [0.15, 1.85] |

| Hypertension | Kasper 2005 | 4 | 173 | 4 | 164 | 0.95 [0.23, 3.85] |

| Indigestion | Kennedy 2005 | 2 | 98 | 6 | 99 | 0.32 [0.06, 1.64] |

| Orthostatic symptoms | Kasper 2005 | 2 | 173 | 1 | 164 | 1.91 [0.17, 21.23] |

| Rhinitis | SCT-MD-09 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 14 | 0.24 [0.02, 2.68] |

| Sexual problems | Kennedy 2005 | 4 | 37 | 1 | 32 | 3.76 [0.40, 35.49] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe ad-verse events | Kasper 2005, Kennedy 2005, Mao 2008 | 8 | 394 | 16 | 380 | 0.48 [0.20, 1.14] |

| Tooth ache | SCT-MD-09 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 14 | 0.40 [0.03, 4.96] |

| Vertigo | Kasper 2005 | 3 | 173 | 7 | 164 | 0.40 [0.10, 1.56] |

| Escitalopram versus paroxetine | ||||||

| DIzziness | Boulenger 2006 | 21 | 229 | 20 | 225 | 1.03 [0.54, 1.97] |

| Erectile dysfunction | Boulenger 2006 | 4 | 75 | 4 | 68 | 0.90 [0.22, 3.75] |

| Sexual problems | Boulenger 2006 | 2 | 75 | 6 | 68 | 0.28 [0.06, 1.45] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Boulenger 2006 | 7 | 229 | 3 | 225 | 2.33 [0.60, 9.14] |

| Escitalopram versus sertraline | ||||||

| Decreased appetite | Ventura 2007 | 8 | 104 | 6 | 108 | 1.42 [0.47, 4.23] |

| Depression | Alexopoulos 2004 | 1 | 134 | 0 | 137 | 3.09 [0.12, 76.52] |

| Flatulence | Alexopoulos 2004 | 6 | 134 | 6 | 137 | 1.02 [0.32, 3.26] |

| Indigestion | Alexopoulos 2004 | 3 | 134 | 7 | 137 | 0.43 [0.11, 1.68] |

| Rhinitis | Alexopoulos 2004 | 6 | 134 | 7 | 137 | 0.87 [0.28, 2.66] |

| Sexual problems | Alexopoulos 2004, Ventura 2007 | 23 | 162 | 23 | 172 | 0.91 [0.48, 1.72] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Alexopoulos 2004 | 3 | 134 | 1 | 137 | 3.11 [0.32, 30.32] |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Alexopoulos 2004, Ventura 2007 | 21 | 238 | 26 | 245 | 0.82 [0.44, 1.50] |

| Escitalopram versus venlafaxine | ||||||

| Cardiac failure | Montgomery 2004 | 0 | 146 | 1 | 143 | 0.32 [0.01, 8.03] |

| Colon Obstruction | Bielski 2004 | 1 | 98 | 0 | 100 | 3.09 [0.12, 76.83] |

| Decreased weight | Montgomery 2004 | 5 | 146 | 10 | 143 | 0.47 [0.16, 1.42] |

| Dermatological problems | Montgomery 2004 | 0 | 146 | 1 | 143 | 0.32 [0.01, 8.03] |

| Dizziness | Montgomery 2004 | 7 | 146 | 8 | 143 | 0.85 [0.30, 2.41] |

| Gastritis | Montgomery 2004 | 0 | 146 | 3 | 143 | 0.14 [0.01, 2.68] |

| Inflicted injury | Bielski 2004 | 0 | 98 | 1 | 100 | 0.34 [0.01, 8.37] |

| Non-accidental overdose | Bielski 2004 | 0 | 98 | 1 | 100 | 0.34 [0.01, 8.37] |

| Sexual problems | Bielski 2004 | 2 | 30 | 12 | 53 | 0.24 [0.05, 1.18] |

| Subjects with non-fatal severe adverse events | Bielski 2004, Montgomery 2004 | 4 | 244 | 8 | 243 | 0.51 [0.14, 1.77] |

| Transitory Ischaemic Attack | Montgomery 2004 | 0 | 146 | 1 | 143 | 0.32 [0.01, 8.03] |

| Vertigo | Montgomery 2004 | 7 | 146 | 6 | 143 | 1.15 [0.38, 3.51] |

1. ESCITALOPRAM versus OTHER SSRIs

A. ESCITALOPRAM versus CITALOPRAM

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was a statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than citalopram (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.89, p = 0.006; 6 studies, 1823 participants) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 1.1 Escitalopram versus other SSRIs.

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram and citalopram (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.56, p = 0.88; 1 study, 357 participants) (Analysis 3.1).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was a statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than citalopram (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.90, p = 0.02; 6 studies, 1823 participants) (see Figure 4). Test for heterogeneity was statistically significant: Tau2 = 0.25; Chi2 = 25.12, df = 5 (P<0.00001); I2=80%. The heterogeneity arose because of the extreme result in the Yevtushenko 2007 trial.

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparison: 4 Failure to remission at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 4.1 Escitalopram versus other SSRIs.

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

Escitalopram was found to be more efficacious than citalopram in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.04, p = 0.009; 5 studies, 1392 participants) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot of comparison: 6 Standardised mean difference at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 6.1 Escitalopram versus other SSRIs.

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

No data available.

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.10, p = 0.16; 6 studies, 1823 participants) (see Figure 6).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.03, p = 0.56; 5 studies, 1604 participants) (see Figure 7).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.31, p = 0.36; 5 studies, 1604 participants) (see Figure 8).

Figure 6. Forest plot of comparison: 7 Failure to complete (any cause), outcome: 7.1 Escitalopram vs. other SSRIs.

Figure 7. Forest plot of comparison: 8 Failure to complete (due to inefficacy), outcome: 8.1 Escitalopram versus other SSRIs.

Figure 8. Forest plot of comparison: 9 Failure to complete (due to side effects), outcome: 9.1 Escitalopram vs. other SSRIs.

7) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a smaller or higher rate of adverse events than citalopram (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.07, p = 0.12; 6 studies, 1802 participants) (Analysis 10.1).

Total number of patients experiencing a specific side effect (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or less rate of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety than citalopram (Analysis 11.1).

b) Constipation

No difference was found between escitalopram and citalopram in terms of number of participants experiencing constipation (Analysis 12.1)

c) Diarrhoea

No difference was found between escitalopram and citalopram in terms of number of participants experiencing diarrhoea (Analysis 13.1).

d) Dry mouth

No difference was found between escitalopram and citalopram in terms of number of participants experiencing dry mouth (Analysis 14.1).

e) Hypotension

A single case of hypotension was reported in one study (Moore 2005) and so there was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram and citalopram (Analysis 15.1).

f) Insomnia

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or less rate of participants experiencing insomnia than citalopram (Analysis 16.1).

g) Nausea

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or less rate of participants experiencing nausea than citalopram (Analysis 17.1).

h) Urination problems

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or less rate of participants experiencing sleepiness than citalopram (Analysis 18.1).

j) Vomiting

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing vomiting than citalopram (Analysis 19.1).

k) Deaths, suicide and suicidality

One patient developed suicidal ideation/tendency (in the escitalopram group) (Analysis 31.1), a total of nine patients attempted suicide (six with escitalopram and three with citalopram) (Analysis 31.2) and one patient died (in the citalopram group) (Analysis 31.4), which was by suicide (Analysis 31.3). However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

l) Other adverse events

Escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing jitteriness than citalopram (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.82, p = 0.03; 1 trial, 369 participants (Analysis 25.1). No statistically significant differences were found for dizziness (Analysis 20.1), fatigue (Analysis 21.1), flu syndrome (Analysis 22.1), headache (Analysis 23.1), impotence (Analysis 24.1), lethargy/sedation (Analysis 26.1), decreased libido (Analysis 27.1), pain (Analysis 28.1, Analysis 28.2, Analysis 28.3), increased sweating (Analysis 29.1) or yawning (Analysis 30.1).

B. ESCITALOPRAM versus FLUOXETINE

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than fluoxetine in the acute phase of treatment (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.10, p = 0.17; 3 studies, 783 participants) (see Figure 3).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

Only one trial reported data on the early phase of treatment and the difference was not statistically significant (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.56, p = 0.73; 1 study, 240 participants) (Analysis 2.1).

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than fluoxetine in terms of remission of symptoms (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.15, p = 0.32; 3 studies, 783 participants) (see Figure 4).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

Escitalopram was found to be more efficacious than fluoxetine in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.03, p = 0.02; 3 studies, 759 participants) (see Figure 5).

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

No data available.

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.55, p = 0.68; 4 studies, 813 participants) (see Figure 6).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.15, p = 0.41; 4 studies, 813 participants) (see Figure 7).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.28, p = 0.29; 4 studies, 813 participants) (see Figure 8).

7) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a less or higher rate of adverse events than fluoxetine (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.07, p = 0.13; 4 studies, 804 participants) (Analysis 10.1).

Total number of patients experiencing specific side effects (only figures for statistically significant differences are reported in the text - for full details see graphs)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety than fluoxetine (Analysis 11.1).

b) Constipation

No difference was found between escitalopram and fluoxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing constipation (Analysis 12.1).

c) Diarrhoea

No difference was found between escitalopram and fluoxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing diarrhoea (Analysis 13.1).

d) Dry mouth

No difference was found between escitalopram and fluoxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing dry mouth (Analysis 14.1).

e) Hypotension

No data available

f) Insomnia

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing insomnia than fluoxetine (Analysis 16.1).

g) Nausea

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing nausea than fluoxetine (Analysis 17.1).

h) Urination problems

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing sleepiness than fluoxetine (Analysis 18.1).

j) Vomiting

No data reported.

k) Deaths, suicide and suicidality

Two patients attempted suicide (one with escitalopram and one with fluoxetine) (Analysis 31.2). Neither of these differences were statistically significant. Overall three patients died, two in the fluoxetine group and one in the escitalopram group (Analysis 31.4) (this patient committed suicide) (Analysis 31.3). No data about suicidal tendency/ideation were reported.

l) Other adverse events

No statistically significant differences were found for dizziness (Analysis 20.1), fatigue (Analysis 21.1), headache (Analysis 23.1), impotence (Analysis 24.1), libido decreased (Analysis 27.1) or pain (Analysis 28.1, Analysis 28.2).

C. ESCITALOPRAM versus PAROXETINE

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than paroxetine in terms of response to treatment (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.32, p = 0.57; 2 studies, 784 participants) (see Figure 3).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram and paroxetine (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.15, p = 0.17; 1 study, 459 participants) (Analysis 3.1).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than paroxetine in terms of remission of symptoms (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.68, p = 0.67; 2 studies, 784 participants) (see Figure 4).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

(a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than paroxetine in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD −0.05, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.26, p = 0.76; 2 studies, 776 participants) (see Figure 5).

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

No data available.

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.29, p = 0.24; 2 studies, 784 participants) (see Figure 6).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 11.44, p = 0.76; 2 studies, 784 participants) (see Figure 7).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.96, p = 0.50; 2 studies, 784 participants) (see Figure 8).

7) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a smaller or larger rate of adverse events than paroxetine (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.17, p = 0.23; 1 study, 454 participants) (Analysis 10.1).

Total number of patients experiencing a specific side effect (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

No data reported.

b) Constipation

No difference was found between escitalopram and paroxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing constipation (Analysis 12.1).

c) Diarrhoea

No difference was found between escitalopram and paroxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing diarrhoea (Analysis 13.1).

d) Dry mouth

No difference was found between escitalopram and paroxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing dry mouth (Analysis 14.1).

e) Hypotension

No data reported.

f) Insomnia

No difference was found between escitalopram and paroxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing insomnia (Analysis 16.1).

g) Nausea

There was no evidence that paroxetine was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing nausea than escitalopram (Analysis 17.1).

h) Urination problems

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness

No data reported.

j) Vomiting

No data reported.

k) Deaths, suicide and suicidality

Neither deaths, nor completed or attempted suicides were reported.

l) Other adverse events

No statistically significant differences were found for dizziness (Analysis 20.1), headache (Analysis 23.1) or increased sweating (Analysis 24.1).

D. ESCITALOPRAM versus SERTRALINE

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was less or more efficacious than sertraline in terms of response to treatment in the acute phase (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.53, p = 0.76; 2 studies, 489 participants) (see Figure 3).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was less or more efficacious than sertraline in terms of remission of symptoms (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.67, p = 0.42; 2 studies, 489 participants (see Figure 4).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

There was no evidence that escitalopram was less or more efficacious than sertraline in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD 0.02, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.20, p = 0.85; 2 studies, 477 participants) (see Figure 5).

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

No data available.

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.97, p = 0.37; 2 studies, 489 participants) (see Figure 6).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 3.09, 95% CI 0.32 to 30.08, p = 0.33; 1 study, 274 participants) (see Figure 7).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.35 to 3.37, p = 0.89; 2 studies, 489 participants) (see Figure 8).

6) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effects

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a smaller or larger rate of adverse events than sertraline (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.19, p = 0.15; 2 studies, 483 participants) (Analysis 10.1).

Total number of patients experiencing a specific side effect (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

No data reported.

b) Constipation

No data reported.

c) Diarrhoea

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea than sertraline (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.84, p = 0.009; 2 trials, 483 participants) (Analysis 13.1).

d) Dry mouth

No difference was found between escitalopram and sertraline in terms of number of participants experiencing dry mouth (Analysis 14.1).

e) Hypotension

No data reported.

f) Insomnia

No difference was found between escitalopram and sertraline in terms of number of participants experiencing insomnia (Analysis 16.1).

g) Nausea

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing nausea than sertraline (Analysis 17.1).

h) Urination problem

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing sleepiness/drowsiness than sertraline (Analysis 18.1).

j) Vomiting

No data reported.

k) Deaths, suicide and suicidality

Neither deaths, nor completed or attempted suicides were reported.

l) Other adverse events

Although not statistically significant, there was some evidence in one study (Ventura 2007) that escitalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing lethargy/sedation than sertraline (OR 3,72, 95% CI 0.99 to 13.94, p = 0.05; 1 trial, 212 participants). No statistically significant differences were found for fatigue (Analysis 21.1), headache (Analysis 22.1), impotence (Analysis 23.1), lethargy/sedation (Analysis 26.1), decreased libido (Analysis 27.1) or increased sweating (Analysis 29.1).

2) ESCITALOPRAM versus NEWER ANTIDEPRESSANTS

A. ESCITALOPRAM versus BUPROPION

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

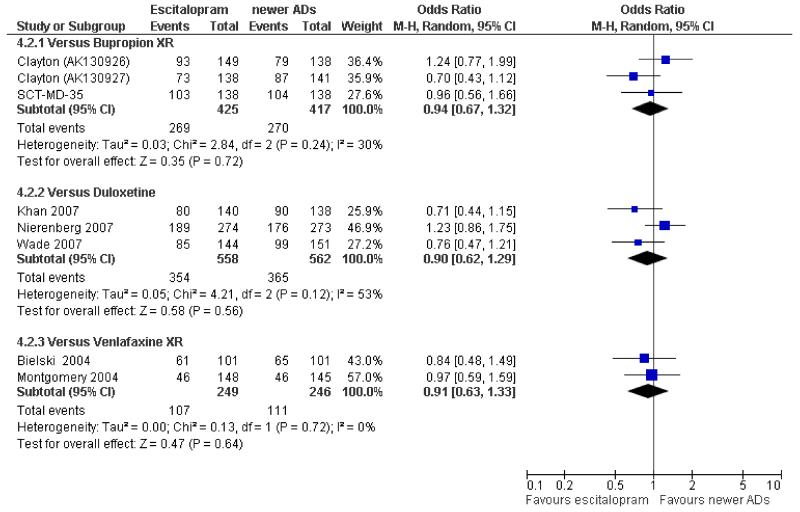

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more efficacious than bupropion in terms of response to treatment in the acute phase (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.20, p = 0.50; 3 studies, 842 participants) (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 1.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

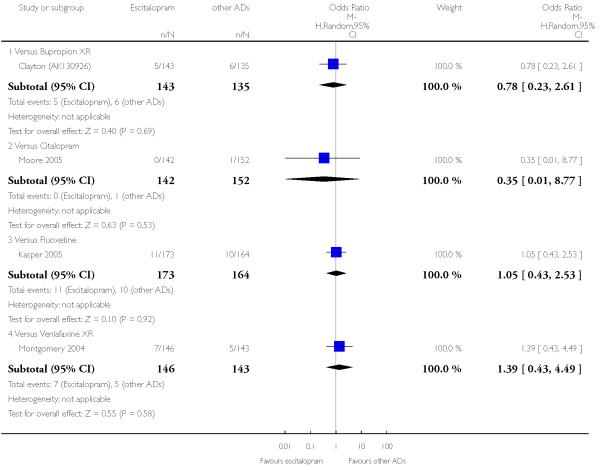

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more efficacious than bupropion in terms of remission of depressive symptoms (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.32, p = 0.72; 3 studies, 842 participants) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Forest plot of comparison: 4 Failure to remission at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 4.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more efficacious than bupropion in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.05, p = 0.23; 3 studies, 793 participants) (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Forest plot of comparison: 6 Standardised mean difference at endpoint (6-12 weeks), outcome: 6.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

No data available.

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.39, p = 0.90; 3 studies, 842 participants) (see Figure 12)

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.02, p = 0.14; 1 study, 276 participants) (see Figure 13)

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.65, p = 0.36; 3 studies, 842 participants) (see Figure 14)

Figure 12. Forest plot of comparison: 7 Failure to complete (any cause), outcome: 7.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

Figure 13. Forest plot of comparison: 8 Failure to complete (due to inefficacy), outcome: 8.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

Figure 14. Forest plot of comparison: 9 Failure to complete (due to side effects), outcome: 9.2 Escitalopram versus newer ADs.

7) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a smaller rate of adverse events than bupropion (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.07, p = 0.12; 3 studies, 822 participants) (Analysis 10.2).

Total number of patients experiencing a specific side effect (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

No difference was found between escitalopram and bupropion in terms of number of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety (Analysis 11.2).

b) Constipation

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing constipation than bupropion (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.69, p = 0.004; 2 studies, 557 participants (Analysis 12.2).

c) Diarrhoea

No difference was found between escitalopram and bupropion in terms of number of participants experiencing diarrhoea (Analysis 13.2).

d) Dry mouth

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing dry mouth than bupropion (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.87, p = 0.007; 3 studies, 822 participants) (Analysis 14.2).

e) Hypotension

No data reported.

f) Insomnia

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing insomnia than bupropion (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.92, p = 0.02; 3 studies, 822 participants) (Analysis 16.2).

g) Nausea

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing nausea than bupropion (Analysis 17.2).

h) Urination problem

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing sleepiness than bupropion (Analysis 18.2).

j) Vomiting

No data reported.

k) Deaths, suicide and suicidality

Two patients developed suicidal ideation/tendency (both in the escitalopram group), however this difference was not statistically significant (Analysis 31.1). Neither deaths, nor completed or attempted suicides were reported.

l) Other adverse events

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing fatigue (OR 3.48, 95%CI 1.77 to 6.84, p = 0.0003; 2 studies, 557 participants) (Analysis 21.2) and yawning (OR 7.71, 95%CI 1.75 to 34.05, p = 0.007; 2 studies, 557 participants) (Analysis 30.2) than bupropion. Although not statistically significant, there was some evidence that irritability was less frequent in patients randomised to escitalopram than in patients allocated to bupropion (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.04, p = 0.06; 2 trials, 557 participants). No statistically significant differences were found for dizziness (Analysis 20.2), headache (Analysis 23.2), or pain (Analysis 28.1, Analysis 28.2, Analysis 28.3, Analysis 28.4).

B. ESCITALOPRAM versus DULOXETINE

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY - Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than duloxetine in terms of response to treatment in the acute phase (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.20, p = 0.21; 3 studies, 1120 participants) (see Figure 9).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than duloxetine in terms of response to treatment at 24 weeks (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.25, p = 0.25; 1 study, 295 participants) (Analysis 3.2).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY - Number of patients who achieved remission

a) Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than duloxetine in terms of remission of depressive symptoms during the acute phase treatment (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.29, p = 0.56; 3 studies, 1120 participants) (see Figure 10).

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than duloxetine in terms of remission of depressive symptoms at 24 weeks (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.16, p = 0.18; 1 study, 295 participants) (Analysis 5.1).

2) EFFICACY - Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

There was no evidence that escitalopram was more or less efficacious than duloxetine in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD −0.10, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.09, p = 0.28; 3 studies, 1096 participants) (see Figure 11).

3) to 5) EFFICACY- Social adjustment, social functioning, health-related quality of life, costs to health care services

One study (Wade 2007) used the SF-36 as a measure of general health status. Ratings from eight subscales were reported and no statistically significant differences between escitalopram and duloxetine were found (data not shown here but available from authors).

6) ACCEPTABILITY - Drop out rate

There was a statistically significant difference with fewer patients allocated to escitalopram withdrawing from study than duloxetine for discontinuation due to any cause (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.99, p = 0.05; 3 studies, 1120 participants) (see Figure 12).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.25, p = 0.95; 3 studies, 1120 participants) (see Figure 13)

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.29, p = 0.15; 3 studies, 1120 participants) (see Figure 14)

7) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect.

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of rate of adverse events (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.38, p = 0.82; 3 studies, 1111 participants) (Analysis 10.2).

Total number of patients experiencing a specific side effect (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Agitation/Anxiety

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety than duloxetine (Analysis 11.2).

b) Constipation

There was no evidence that escitalopram was associated with a higher or lower rate of participants experiencing constipation than duloxetine (Analysis 12.2).

c) Diarrhoea

No difference was found between escitalopram and duloxetine in terms of number of participants experiencing diarrhoea (Analysis 13.2).

d) Dry mouth

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing dry mouth than duloxetine (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.79, p = 0.001; 3 trials, 1111 participants) (Analysis 14.2).

e) Hypotension

No data reported.

f) Insomnia

Even though not statistically significant, there was some evidence that insomnia was less frequent in patients treated with escitalopram than in patients randomised to duloxetine (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.02, p = 0.06; 3 trials, 1111 participants) (Analysis 16.2).

g) Nausea

There was evidence that escitalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing nausea than duloxetine (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.75, p = 0.0001; 3 trials, 1111 participants) (Analysis 17.2).

h) Urination problem

No data reported.

i) Sleepiness/drowsiness