Measurement of intraperitoneal pressure (IPP) is not recommended in peritoneal dialysis (PD) guidelines. However, it can be a useful tool to individualize PD prescription, especially because IPP determination is simple, rapid, and precise (1).

Intraperitoneal pressure has been shown to be inversely correlated with ultrafiltration (UF), through either the induction of a higher lymphatic absorption rate (2) or modification of transcapillary UF (3-5). Alterations in peritoneal solute transport have also been associated with IPP—not only because of reduced effective surface area, but also because of a decrease in intrinsic peritoneal permeability (5).

The relationship between IPP and some known complications associated with PD is still a matter of debate. Hydrothorax, abdominal wall hernias, and gastroesophageal reflux are presumably related to the raised IPP seen with the infusion of peritoneal dialysate (6-8), but any potential relationship has not been thoroughly studied in PD patients.

The main objectives of the present study were to determine the relationship between IPP and baseline clinical characteristics, to evaluate the influence of IPP on known complications associated with PD, and to assess the effect of IPP on the composite outcome of death or switch to hemodialysis (HD).

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of data for all patients in our unit with at least 1 IPP measurement. None of the patients had experienced an episode of peritonitis within the month preceding the IPP determination, and all were using automated PD. The 54 study patients (69% men; mean age: 58 ± 15 years) were instilled with 2000 mL 3.86% glucose dialysate for a 4-hour exchange period. The patients were allowed to ambulate during that time. The IPP was determined with the patient in the supine position, before drainage of the peritoneal cavity; a graduated column (centimeters) was connected to the PD catheter and the zero level was placed on the mid-axillary line. Determinations were made during inspiration and expiration, and the average between the two determinations was considered the final value (expressed in centimeters of H2O). The UF volume was calculated as the difference between the drained and instilled volumes.

We assessed the relationship between IPP and baseline clinical characteristics [age, sex, time on PD until IPP determination, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), body surface area (BSA), presence of diabetes, and UF volume] and also the possible influence of IPP on PD complications—namely, abdominal wall hernias, hydrothorax, and gastroesophageal reflux. The definition of gastroesophageal reflux included typical symptoms, with either endoscopic evidence of esophagitis or improvement after administration of a proton pump inhibitor. The composite outcome of all-cause mortality or switch to HD because of technique failure was also evaluated.

Correlations between IPP and clinical variables were assessed using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for continuous variables and the independent-samples t-test for binary variables. The independent-samples t-test was used to assess the associations between IPP and complications. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to set an IPP cut-off point discriminating normal from high values. The predictors of the composite outcome were found by multivariate analysis with a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results

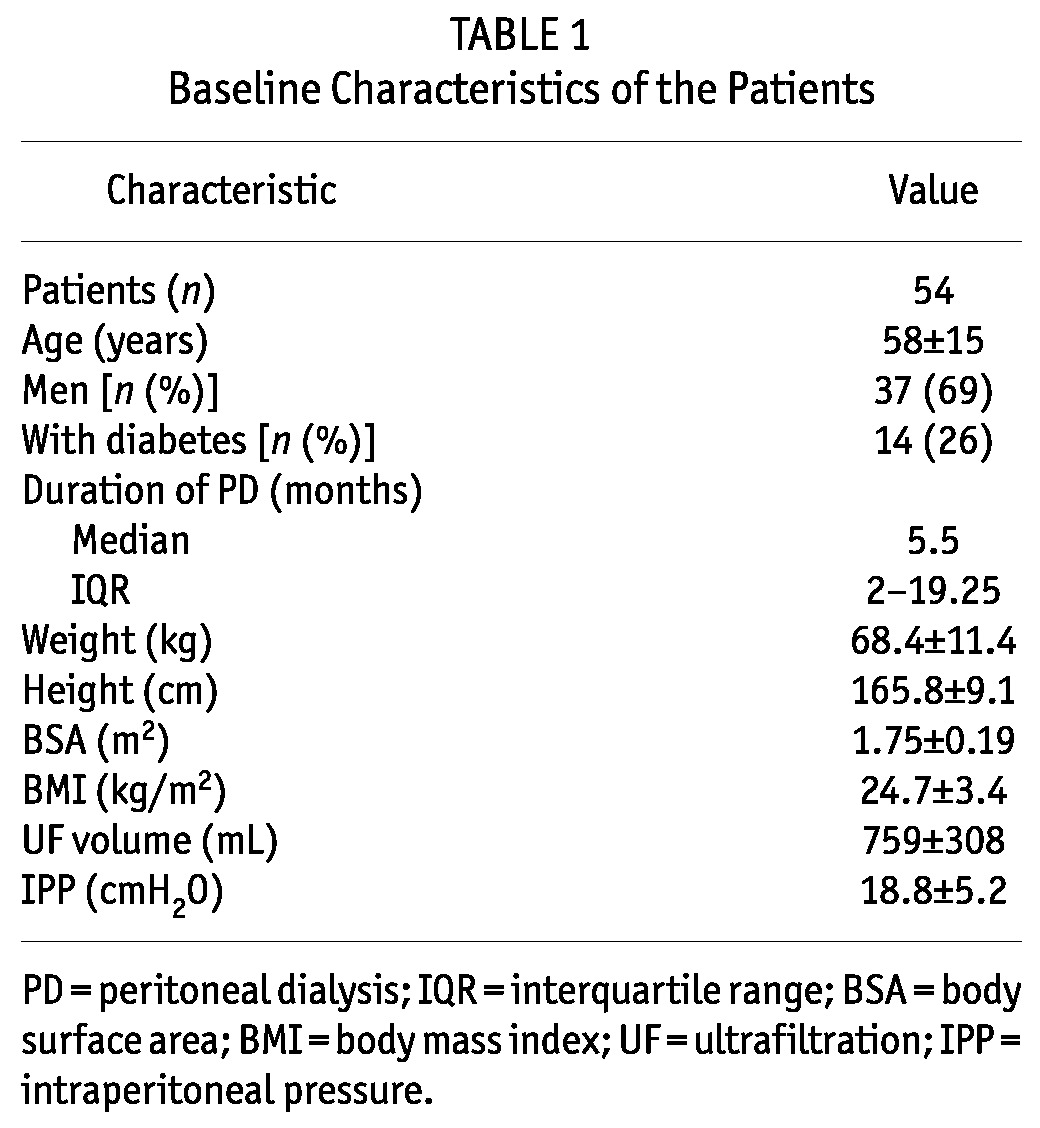

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 54 identified patients. The causes of end-stage renal disease in the patients were diabetic nephropathy (n = 11), interstitial nephritis (n = 9), hypertensive nephrosclerosis (n = 7), autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (n = 6), chronic glomerulonephritis (n = 6), systemic lupus erythematous (n = 1), Alport syndrome (n = 1), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (n = 2), type II cardiorenal syndrome (n = 1), and unknown (n = 10).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

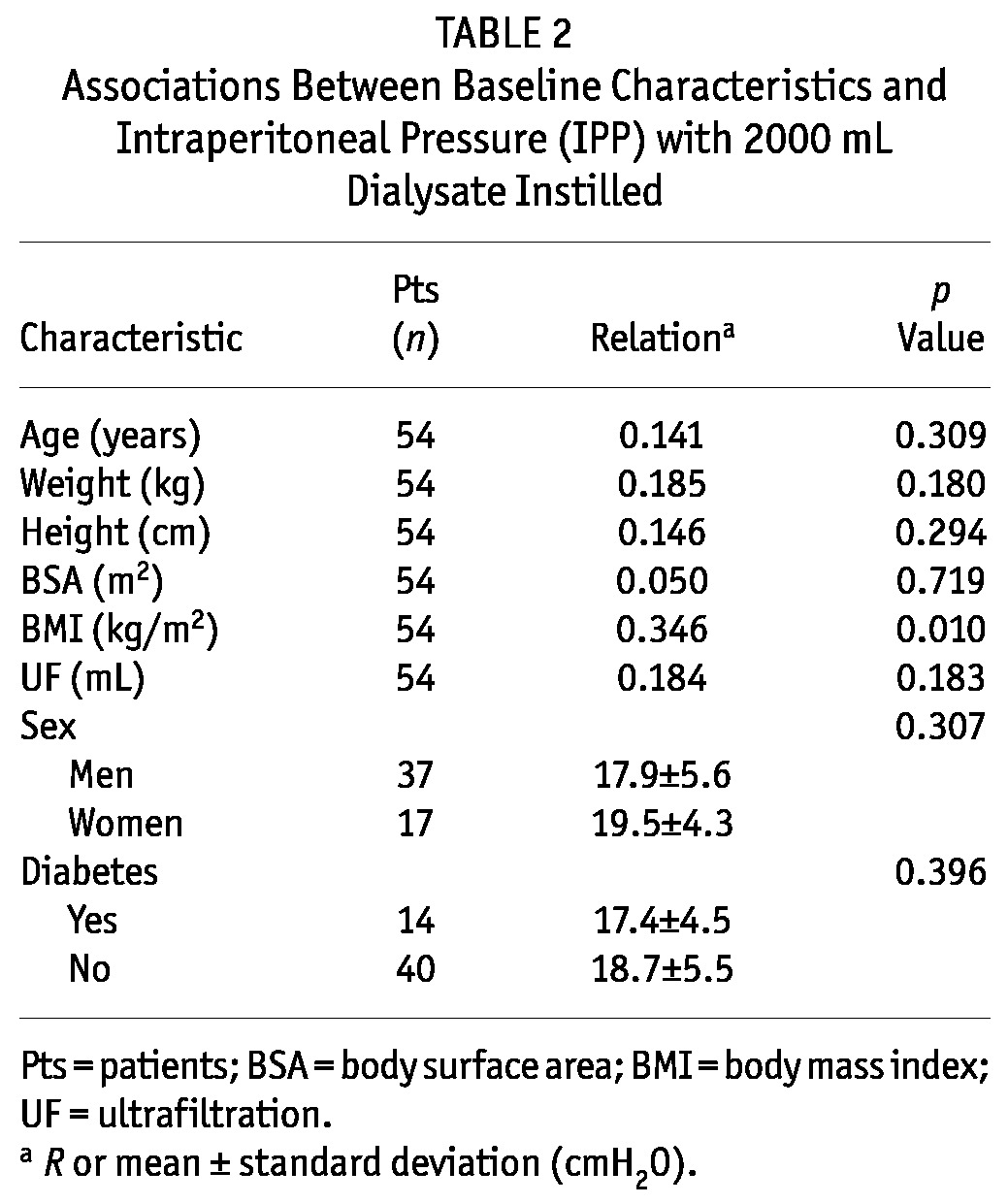

The mean IPP was 18.8 ± 5.2 cmH2O, and the patients had been treated with PD for a median of 5.5 months (interquartile range: 2 - 19.25 months). Table 2 presents the relationships between IPP and baseline characteristics. The only biometric parameter that correlated with IPP was BMI (R = 0.346, p = 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Associations Between Baseline Characteristics and Intraperitoneal Pressure (IPP) with 2000 mL Dialysate Instilled

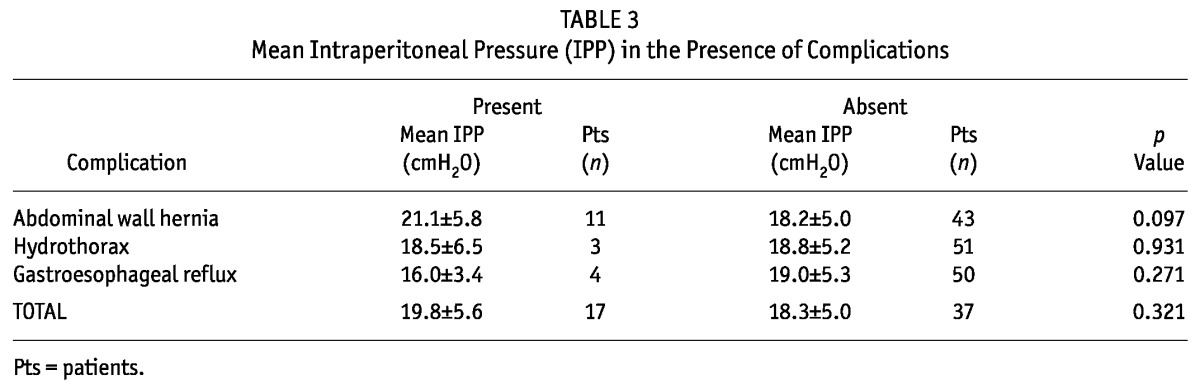

We observed 18 complications in 17 patients: 3 cases of hydrothorax, 11 abdominal wall hernias, and 4 cases of gastroesophageal reflux. Statistically significant relationships were not found between higher IPP values and the incidences of complications; however, we observed a trend toward a higher incidence of abdominal wall hernias in patients with an elevated IPP (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Mean Intraperitoneal Pressure (IPP) in the Presence of Complications

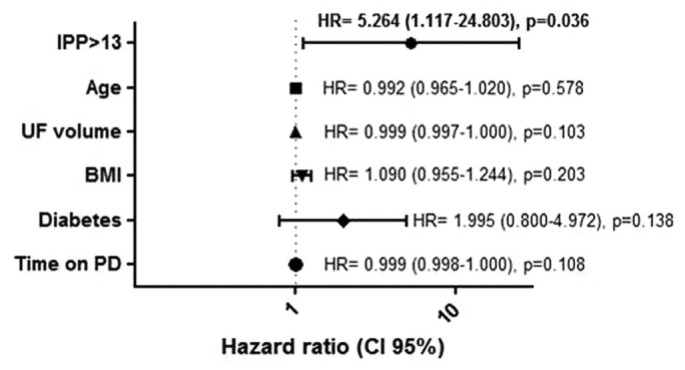

The composite outcome of death and switch to HD because of technique failure occurred in 50% of the patients (12 died, 15 started HD) during a mean follow-up of 744 ± 404 days. The optimal cut-off IPP value to discriminate patients with a higher risk of the composite outcome was 13 cmH2O. After adjustment for potential confounders such as age, UF volume, BMI, diabetes, and time on PD, an IPP exceeding 13 cmH2O was the only independent predictor of death or switch to HD by multivariate analysis (hazard ratio: 5.26; 95% confidence interval: 1.12 to 24.80; p = 0.036; Figure 1).

Figure 1 —

Multivariate analysis of predictors of death or switch to hemodialysis. IPP = intraperitoneal pressure; UF = ultrafiltration; BMI = body mass index; PD = peritoneal dialysis; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

We observed higher IPP values in our patients than in those described in the literature (1-3,8). Considering that IPP rises when the patient is in the upright position, our finding can be explained by the fact that, in earlier studies, patients were not allowed to ambulate as they were in our study. As previously reported, IPP is an individual characteristic that depends on the corpulence of the patient, as represented by the BMI (8).

Complications such as hydrothorax (6), abdominal wall hernias (7,8), and gastroesophageal reflux (8) have been associated with higher IPP. Theoretically, the physiologic principle seems obvious, but a statistical correlation has been difficult to establish. We did not find such a relation in our study, although we observed a trend toward higher IPP in patients with abdominal wall hernias than in other patients. Based on that trend, it is reasonable to individualize PD prescription by lowering the IPP, provided that solute clearance is not dangerously affected. The small number of patients with complications to whom this suggestion applies might justify the lack of statistical significance in our results.

The present work also suggests that IPP might be a marker of clinical outcome, as demonstrated by the significant association between higher IPP and death or switch to HD because of technique failure. Patients with an IPP exceeding 13 cmH2O were more likely to experience the composite outcome. Alterations in the peritoneal microcirculation induced by higher IPP might lead to a reduced effective surface area and activation of as-yet unclear mechanisms leading to increased mortality. The compression exerted on the peritoneal vasculature may have important effects on the diffusive capacity of the peritoneum (5). Paniagua et al. (9) found that increases in the dialysate volume might elicit proinflammatory effects, as evidenced by increments in peritoneal interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor α. Because an increase in IPP is an expected result of an increase in fill volume, we speculate that the latter effects might be partly attributed to the raised IPP. Although our study has some limitations such as its retrospective nature and small number of patients, our results are interesting and merit evaluation in future prospective studies.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Durand PY, Chanliau J, Gamberoni J, Hestin D, Kessler M. Routine measurement of hydrostatic intraperitoneal pressure. Adv Perit Dial 1992; 8:108–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abensur H, Romão JE, Prado EB, Kakehashi E, Sabbaga E, Marcondes M. Influence of the hydrostatic intraperitoneal pressure and cardiac function on the lymphatic absorption rate of the peritoneal cavity in CAPD. Adv Perit Dial 1993; 9:41–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durand PY, Chanliau J, Gamberoni J, Hestin D, Kessler M. Intraperitoneal hydrostatic pressure and ultrafiltration volume in CAPD. Adv Perit Dial 1993; 9:46–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durand FY, Chanliau J, Gamberoni J, Hestin D, Kessler M. Intraperitoneal pressure, peritoneal permeability and volume of ultrafiltration in CAPD. Adv Perit Dial 1992; 8:22–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Imholz A, Koomen G, Struijk D, Arisz L, Krediet R. Effect of an increased intraperitoneal pressure on fluid and solute transport during CAPD. Kidney Int 1993; 44:1078–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lew SQ. Hydrothorax: pleural effusion associated with peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bargman JM. Hernias in peritoneal dialysis patients: limiting occurrence and recurrence. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:349–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dejardin A, Robert A, Goffin E. Intraperitoneal pressure in PD patients: relationship to intraperitoneal volume, body size and PD-related complications. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22:1437–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paniagua R, Ventura Mde J, Rodriguez E, Sil J, Galindo T, Hurtado ME, et al. Impact of fill volume on peritoneal clearances and cytokine appearance in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2004; 24:156–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]