Abstract

Background

There is a decreased interest in nephrology such that the number of trainees likely will not meet the upcoming workforce demands posed by the projected number of patients with kidney disease. We conducted a survey of US internal medicine subspecialty fellows in fields other than nephrology to determine why they did not choose nephrology.

Methods

A web-based survey with multiple choice, yes/no, and open-ended questions was sent in summer 2011 to trainees reached through internal medicine subspecialty program directors.

Results

714 fellows responded to the survey (11% response rate). All non-nephrology internal medicine subspecialties were represented, and 90% of respondents were from university-based programs. Of the respondents, 31% indicated that nephrology was the most difficult physiology course taught in medical school, and 26% had considered nephrology as a career choice. Nearly one-fourth of the respondents said they would have considered nephrology if the field had higher income or the subject were taught well during medical school and residency training. The top reasons for not choosing nephrology were the belief that patients with end-stage renal disease were too complicated, the lack of a mentor, and that there were insufficient procedures in nephrology.

Conclusions

Most non-nephrology internal medicine subspecialty fellows never considered nephrology as a career choice. A significant proportion were dissuaded by factors such as the challenges of the patient population, lack of role models, lack of procedures, and perceived difficulty of the subject matter. Addressing these factors will require the concerted effort of nephrologists throughout the training community.

INDEX WORDS: Non-renal fellows survey, nephrology education, mentors, perception of nephrology, internal medicine fellows, nephrology workforce

Interest in obtaining fellowship training in nephrology has declined among US medical graduates during the past decade.1 In contrast, the number of available nephrology fellowship positions during the past several years has increased in response to the perceived need for more nephrologists to meet growing clinical demands.1,2 Thus, there is a disconnect between supply and demand for nephrologists, particularly with regard to US medical graduates pursuing nephrology training.

What are the factors driving this fading interest in nephrology careers? There is no evidence that declining numbers of US medical graduates entering internal medicine residency programs are to blame. According to data obtained from the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP), the percentage of US medical graduates matching into categorical internal medicine residency positions has remained constant over the last 5 years despite a steady increase in the number of internal medicine positions offered in the match from 2008 to 2012.3 Another possibility is that internal medicine residents may either pursue other specialties or decide not to subspecialize at all, instead choosing careers in general internal medicine or hospital medicine. According to data obtained from the NRMP, there appears to be a small but consistent decrease in the number of applicants applying to internal medicine specialties since 2008.3 Cardiology, infectious diseases, and gastroenterology have all had a small decrease in their ratio of fellowship applicants per position since 2008. Endocrinology has not experienced similar changes during the last 5 years, whereas hematology/oncology has seen a slight increase in the ratio of fellowship applicants per position. Pulmonary/critical care medicine, which originally had seen a decrease in fellowship applicants per position from 2008 to 2011, reversed this trend in 2012.3 However, nephrology has experienced the steepest decrease in the ratio of number of fellowship applicants per position, from 1.6 to 1.1 from 2008 to 2012.3 It is unclear why interest in nephrology as a career is declining, but a variety of factors could be contributing to the trend. Putative factors include medical school renal pathophysiology courses that are not stimulating or are difficult to understand, a lack of representative nephrology elective experience during medical school or residency training, inadequate mentorship, the perceived heavy workload and poor remuneration in nephrology, and interaction with nephrology fellows or attending physicians who are less satisfied or dissatisfied with their career choice.1,4,5

To address this critical issue, the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) created a task force in 2010 to reverse the declining interest in nephrology. It became evident that input from internal medicine subspecialty fellows who did not choose nephrology as a career would be important. In order to understand why nephrology is less attractive than other internal medicine subspecialties, we surveyed non-nephrology internal medicine subspecialty fellows.

METHODS

We identified e-mail addresses of all internal medicine subspecialty program directors using the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education database (www.acgme.org/adspublic/). In May 2011, we asked these program directors to forward our survey to their respective fellows and sent reminders in June and July 2011. The survey (Box 1) had 11 questions about respondents’ perceptions of nephrology as a career, including their comfort with clinical topics in nephrology and their reasons for choosing their field of interest. The web-based survey branched so that those who had considered nephrology at some point were asked different questions than those who had not. This anonymous survey was web-based and implemented using SurveyMonkey software. The survey was voluntary and allowed respondents to skip questions that they preferred not to answer. There was no incentive to take the survey. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review boards at both the North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System and Duke University Medical Center.

Box 1. Survey Questions.

-

What fellowship program are you in? (99.7%)

Cardiology

Endocrinology

Rheumatology

Pulmonary/Critical Care

Heme/Oncology

Gastroenterology

Geriatrics

Sleep

Palliative Care

Infectious Disease

Other [free response]

-

What type of training program are you in? (Check all that apply) (99.7%)

University-based hospital

Community-based hospital

Private institution

Public institution

I am doing research for a large part of my fellowship

I am primarily doing clinical duties for most of my fellowship

Other [free response]

Was nephrology the most difficult physiology course in your medical school training? (99.1%) [yes/no]

-

What is the most difficult topic in nephrology to grasp? (check all that apply) (96.4%)

Acid-base

Hypertension

Electrolyte disorders

Glomerular diseases

Transplant immunology

Dialysis modalities and their complexities

Acute kidney injury

Other [free response]

Did you ever consider doing a nephrology fellowship? (99.4%) [yes/no; if no, skip to question 7]

-

If you had considered nephrology, what changed your mind? (check all that apply) (100%)

Concerned about work hours being too much

Tried to do nephrology, but didn’t match

Monetary benefit is not good

Fell in love with another field more than nephrology

-

What didn’t you like about nephrology?(click all that apply) (71.4%)

Too difficult of a subject matter to grasp

Not taught well

No role model or mentor to guide me toward nephrology

Monetary benefit is not good

Lifestyle is not good

Dialysis and transplant patients are too complicated to take care of

Not enough procedures

Other [free response]

If nephrology was taught well, would you have considered it? (96.2%) [yes/no]

If nephrologists had higher incomes than currently, would you have considered it? (98.1%) [yes/no]

If you hadn’t matched into your current fellowship, was nephrology ever your second choice? (99.2%) [yes/no]

Did you know that by 2020, there is estimated to be a shortage of nephrologists? (99.5%) [yes/no]

Note: Response rate is indicated in parentheses.

RESULTS

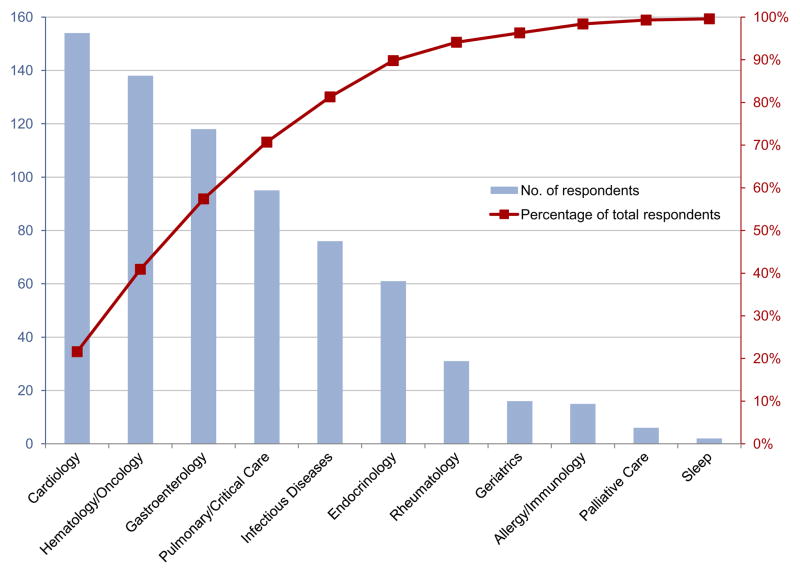

A total of 714 US internal medicine subspecialty fellows completed at least some portion of the survey, which represented ~11% of the total number of non-nephrology fellows enrolled in US internal medicine subspecialty fellowships in 2011. As seen in Fig 1, respondents represented a wide range of specialties in internal medicine, with the largest subset pursuing cardiology. The majority of respondents (91%) were from university-based programs. Response rates for each question ranged from 71%–100%.

Figure 1.

Subspecialties of survey respondents. Columns (left axis) show the total number of survey respondents within each subspecialty; the line graph (right axis) plots the cumulative percentages of total respondents with each subspecialty.

Thirty-one percent of respondents answered affirmatively when asked if nephrology was the most difficult physiology course in their medical school training. When asked to select the most difficult topics to grasp in nephrology, respondents chose acid-base disorders (42%), glomerular diseases (39%), dialysis modalities (32%), and electrolyte disorders (30%) most frequently. Acute kidney injury (1%) and hypertension (0.4%) were selected least frequently as the most difficult topics (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Respondents’ views of the most difficult topics in nephrology (question 4). Raw numbers of responses are plotted according to subspecialty. The right side of the graph gives an overall view of the frequency with which each response was selected. Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; HTN, hypertension; Tx, transplantation.

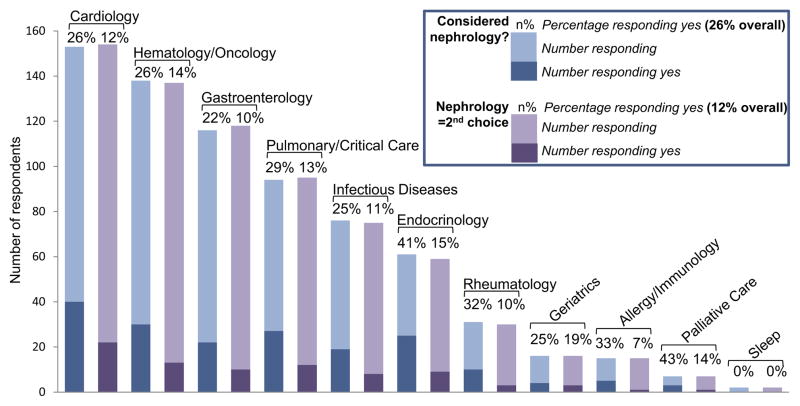

Although 26% (185 of 710) of responding fellows had considered nephrology as a career choice, only 12% indicated that nephrology was their second choice of internal medicine subspecialties. Endocrinology fellows were most likely to have considered nephrology as a career choice, and gastroenterology fellows were the least likely (Fig 3). The overwhelming majority (86%) of respondents who had considered a nephrology fellowship at one point selected enthusiasm for another field as the reason they changed their minds. Twenty-two percent of respondents selected long work hours as a basis for their concern, and 14% cited poor monetary benefit. A very small percentage of respondents (2%) chose another fellowship after not matching into a nephrology fellowship program.

Figure 3.

Responses to the questions “Did you ever consider doing a nephrology fellowship?” and “If you hadn’t matched into your current fellowship, was nephrology ever your second choice?” For each subspecialty, numbers of respondents and respondents answering yes are indicated. Proportions of affirmative responses are listed on the top of each column.

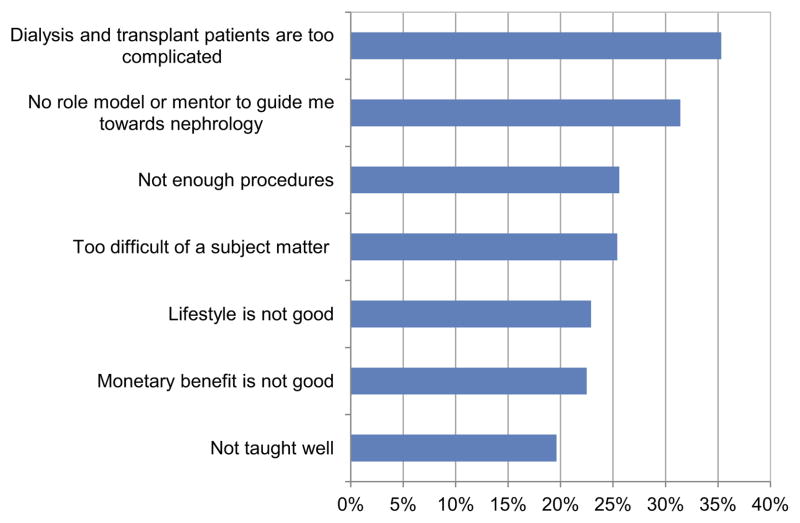

When asked what they did not like about their experience in nephrology (Fig 4), the most frequently selected answer, for nearly one-third of respondents, was that the care of dialysis and transplantation patients was too complicated. The next most popular selection was having no role model or mentor to guide the respondent toward nephrology. In addition to the multiple choice options provided, 237 participants provided free responses, which raised concerns such as the satisfaction to be derived from caring for a chronic disease population, the perceived lack of variety in treating dialysis patients, and the lack of research opportunities in nephrology.

Figure 4.

Responses to the question “What didn’t you like about nephrology?” Total number of respondents was 516.

Nearly one-fourth of non-nephrology fellow respondents would have considered nephrology if this specialty had a higher income potential (23%) or was taught well (24%). Moreover, a majority of respondents (79%) were not aware of the estimated shortage of nephrologists in the United States by 2020.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first survey to evaluate non-nephrology internal medicine fellows’ perceptions about nephrology. A similar survey was performed in pediatric non-nephrology fellows during the same period.6 Results of the present survey of non-nephrology internal medicine fellows revealed several key issues that could enhance interest in nephrology careers among trainees if addressed correctly.

Recent surveys have shown that most US nephrology fellows make decisions to pursue nephrology during medical school and residency.4,5 Presenting nephrology topics in a clear and attractive manner could improve interest in nephrology. When asked if they would have considered nephrology if it had been taught well, nearly one-fourth of the respondents responded affirmatively. Acid-base disorders, glomerular diseases, dialysis modalities, and electrolyte disorders were chosen as the most difficult topics to grasp. We must consider using alternate and innovative methods to enhance teaching of these topics.7,8 Using current e-learning modalities that are well adapted to today’s learner also could be helpful.9–13 In addition, efforts to enhance the teaching and mentoring skills of faculty will require significant investment in faculty development workshops. The use of teaching tracks for academic advancement and rewarding excellence in teaching and mentoring can accomplish this.

In our survey, for respondents who had considered nephrology but ended up choosing another subspeciality, the most commonly selected reason was “fell in love with another field more than nephrology.” However, only 12% of respondents said that nephrology was their second choice. It is plausible that one of the factors that may decrease interest in nephrology careers might be inadequate exposure to all aspects of nephrology during medical school or residency. A well-structured nephrology elective combining both inpatient and representative outpatient experiences could broaden trainees’ exposure to the field.14 At our institutions (North Shore University Hospital and Long Island Jewish Medical Center), we have restructured the nephrology elective for all medical students and residents.14 We believe that this redesigned elective could enhance interest in nephrology careers.

Procedures within an internal medicine subspecialty also may influence career choice. Our results indicate that fellows in subspecialties such as gastroenterology and cardiology were less likely to have expressed interest in nephrology (Fig 3). To attract individuals who may seek more procedural-based careers, trainee exposure to interventional nephrology can be broadened as well.

A greater percentage of international medical graduates are applying to nephrology training programs compared to other internal medicine specialities.1 Furthermore, the top internal medicine specialty in terms of percentage of positions filled by international medical graduates is nephrology (52%).3 These data suggest that the workforce is becoming dependent on this source of graduates in both the academic and private nephrology settings. Efforts need to be undertaken to understand why international medical graduates are more interested in nephrology.

Does mentorship have an important role in developing interest in nephrology? A recent survey of US adult nephrology fellows found that one of the top reasons that fellows chose nephrology was as the result of mentoring or role models in nephrology during medical school and medical residency.4 Mentorship also was reported as one of the important reasons for pursuing a career in nephrology in a 2009 ASN fellow membership survey. 5 Similarly, mentorship was found to be an important factor in a study by West et al,15 who surveyed postgraduate year 3 residents and asked them to rate the importance of several factors in choosing their careers, consistent with the existing literature showing that mentorship is critical for stimulating interest in a particular field.16–18 Another study of internal medicine residents also indicated a desire for increased mentorship from nephrologists.14 Although mentorship clearly has an important role in career choices made by medical students and residents, unfortunately, 31% of our respondents say they did not have a role model or mentor to guide them into nephrology. Concerted efforts by the training community to provide both clinical and research mentorship to medical students and residents are required to change this in the future. The National Institutes of Health, National Kidney Foundation, and ASN are potential organizations that can develop these efforts.

For many graduating medical students and residents, lifestyle and work-life balance are important factors in career decisions. Medical students surveyed in 1996–2002 regarding their career decisions expressed that perceived lifestyle was an important consideration.18 Nephrologists are viewed by many to be some of the busiest physicians in the hospital, often working extended hours; this perception leads many students and residents to seek careers in other fields.19 A study looking at career satisfaction of more than 6,000 US physicians ranked nephrology 40th of 42 specialties, and the inability to control work-life balance was a major reason for dissatisfaction.20 In a career choice survey of US nephrology fellows, long work hours was cited as one of the top 3 reasons for less satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their career choice.4 In the present survey of non-nephrology fellows, concerns about long work hours were reported by only 22% of fellows who had at one point considered pursuing a nephrology fellowship. These results suggest that internal medicine residents either do not perceive that there are extended work hours in nephrology or that this factor does not weigh heavily in their ultimate career decision. Finally, economic factors can have an important role in career decisions, especially given the increased debt burden that many medical students experience. Poor income potential and limited job opportunities after graduation were 2 of the 3 top reasons for dissatisfaction among US adult nephrology fellows in a 2011 survey,4 but earnings and employment data suggest that in reality, nephrology does not rank poorly in these 2 areas.21,22 Of respondents who had considered pursuing nephrology in our survey, only 14% of non-nephrology fellows claimed to be influenced by monetary issues. This suggests that most respondents either did not perceive nephrology to be low paying or did not weight this factor heavily.

As suggested earlier, the percentage of medical students entering internal medicine residency programs has remained stable, but there is a decrease in fellowship applications in many subspecialties such as cardiology, gastroenterology, and most notably, nephrology.3 This suggests that more applicants are considering careers in either general internal medicine or hospital medicine. A decrease in subspecialization was documented as early as 1999.23 For many, hospitalist jobs are more appealing and a better fit for their lifestyle, and strong efforts are being made to attract medical students and residents into hospitalist careers.24 In addition, studies have shown that hospitalists rate their job satisfaction very highly.25 A 2008 study of career plans among internal medicine residents that factored in educational debt showed that US medical graduates with debt of $100,000–$150,000 were less likely than those with no debt to choose a subspecialty career.26 Factors such as lifestyle and monetary reimbursement are more difficult to control or change, but will need to be considered if we plan to continue attracting trainees into the field of nephrology.

Our study limitations include the inability to contact non-nephrology fellows directly because there is no available public database with these trainees’ contact information. We depended on fellowship program directors to forward our survey to their trainees. Also, the timing for contact (from June and July) may have led to a lower than expected response rate because graduating fellows might not have had time or desire to complete the survey. Because we did not ask about the locations of medical school training, we could not determine what percentage of respondents were US versus international medical graduates. Most respondents were undergoing fellowship training in university-based programs. The small sample size of 11% of total practicing non-nephrology fellows limits the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, we did not poll individuals who pursued general internal medicine or hospital medicine. The questions used in this survey were not validated or used in a prior survey. Furthermore, the negative format in which certain questions were asked (ie, what are the most difficult topics in nephrology to grasp?) could have introduced bias. Another limitation of this study is that we did not assess views on chronic kidney disease. Research or scholarly opportunities as a reason to choose a field of medicine also was not addressed in this survey. This might be an important factor because basic research opportunities in nephrology might be decreasing.27 In addition, a set of control groups was not considered. For example cardiology fellows could have been asked why they did not consider infectious disease or gastroenterology in addition to nephrology, and these answers could have been compared. Despite these limitations, we believe that the study of the reasons why nephrology is not chosen as a career is important if we are to improve interest in the field.

In summary, a majority of the internal medicine non-nephrology fellows in the United States in 2011 who took this survey never considered nephrology as a career choice. A significant proportion were dissuaded by several factors, including a complicated nephrology patient population, a perceived lack of role models or mentors, a sense that nephrology does not offer enough procedures, and difficult-to-understand subject matter. Each of these factors can be addressed, but will require the concerted efforts by nephrologists throughout our training community.

Acknowledgments

Dr Jhaveri serves on the ASN workforce committee and as the editor of eAJKD, the official blog of AJKD. Drs Sparks and Desai serve as members of the advisory board for eAJKD. Dr Shah is the director of the nephrology fellowship program at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine. Dr Parker serves as the chair of the ASN workforce committee.

We thank Dr Emily Petersen for help in the initial phases of the project and all the US internal medicine subspecialty program directors and fellows who distributed and took the survey, respectively.

Support: None.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented as an oral presentation at the ASN Kidney Week, November 8–13, 2011 in Philadelphia, PA.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Parker MG, Ibrahim T, Shaffer R, Rosner MH, Molitoris BA. The future nephrology work force: will there be one? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(6):1501–1506. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01290211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai T, Ferris M, Christiano C, Fang X. Predicting the number of US medical graduates entering adult nephrology fellowships using search term analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(3):467–469. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Resident Matching Program. Match Results Statistics: Specialties Matching Service 2012 Appointment Year. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah HH, Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Mattana J. Career choice selection and satisfaction among United States adult nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(9):1513–1520. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01620212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker MG, Owens S, Rosner MH. Nephrology as a career choice [abstract SA-PO2868] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:767A. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris M, Trachtman H, Jhaveri KD, et al. Pediatric nephrology as a specialty: survey of USA non-renal pediatric fellows [abstract FROR268] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:64A. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderon K, Vij R, Mattana J, Jhaveri KD. Innovative teaching tools in nephrology. Kidney Int. 2011;79(8):797–799. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jhaveri KD, Chawla A, Shah HH. Case based debates: an innovative teaching tool in nephrology education. Ren Fail. 2012;34(8):1043–1045. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.697443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparks MA, O’Seaghdha C, Sethi SK, Jhaveri KD. Embracing the internet as a means of enhancing medical education in nephrology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(4):512–518. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethi SK. Invited manuscript poster on renal-related education American Society of Nephrology, Nov. 16–21, 2010. E-pediatric nephrology in India. Ren Fail. 2011;33(7):751–752. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.589953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethi SK, Desai TP, Jhaveri KD. Online blogging during conferences: an innovative way of e-learning. Kidney Int. 2010;78(12):1199–1201. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai T, Talento R, II, Christiano C, Ferris M, Hewan-Lowe K. Web-based nephropathology teaching modules and user satisfaction: the nephrology on demand experience. Ren Fail. 2011;33(10):1046–1048. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.618968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai T, Stankeyeva D, Chapman A, Bailey J. Nephrology fellows show consistent use of, and improved from, a nephrologist-programmed teaching instrument. J Nephrol. 2011;24(3):345–350. doi: 10.5301/JN.2010.5820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhaveri KD, Shah HH, Mattana J. Enhancing interest in nephrology careers during medical residency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):350–353. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West CP, Drefahl MM, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Internal medicine resident self report of factors associated with career decisions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:946–949. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1039-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaminetzky CP, Keitz SA, Kashner TM, et al. Training satisfaction for subspecialty fellows in internal medicine: findings from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Learners’ Perceptions Survey. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girard DE, Choi D, Dickey J, Dickerson D, Bloom JD. A comparison study of career satisfaction and emotional states between primary care and speciality residents. Med Educ. 2006;40:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. Influence of controllable life style on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA. 2003;290:1173–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane CA, Healy C, Ho MT, Pearson SA, Brown MA. How to attract a nephrology trainee: quantitative questionnaire results. Nephrology. 2008;13:116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leigh JP, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL. Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:166. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, Kravitz RL. Physician wages across specialties: informing the physician reimbursement debate. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1728–1734. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, Kravitz RL. Annual work hours across physician specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1211–1213. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langdon LO. Subspecialty internal medicine in the United States: in and outside the hospital. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1999;129(4):1970–1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasheen J. The fast, furious future. [Accessed August 29, 2012];The Hospitalist 2009. www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/185988/The_Fast_Furious_Future.html.

- 25.Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalist: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28–36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:416–420. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Awqati Q. Basic research in nephrology: are we in decline? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1611–1616. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]