Abstract

Background

The number of visits for antenatal (prenatal) care developed without evidence of how many visits are necessary. The content of each visit also needs evaluation.

Objectives

To compare the effects of antenatal care programmes with reduced visits for low-risk women with standard care.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (April 2010), reference lists of articles and contacted researchers in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing a reduced number of antenatal visits, with or without goal-oriented care, with standard care.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors assessed trial quality and extracted data independently.

Main results

We included seven trials (more than 60,000 women): four in high-income countries with individual randomisation; three in low- and middle-income countries with cluster randomisation (clinics as the unit of randomisation). The number of visits for standard care varied, with fewer visits in low- and middle- income country trials. In studies in high-income countries, women in the reduced visits groups, on average, attended between 8.2 and 12 times. In low- and middle- income country trials, many women in the reduced visits group attended on fewer than five occasions, although in these trials the content as well as the number of visits was changed, so as to be more ‘goal oriented’.

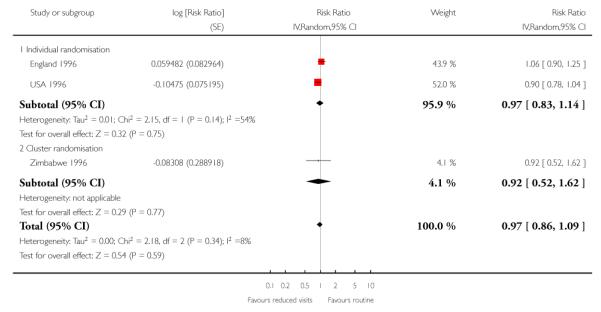

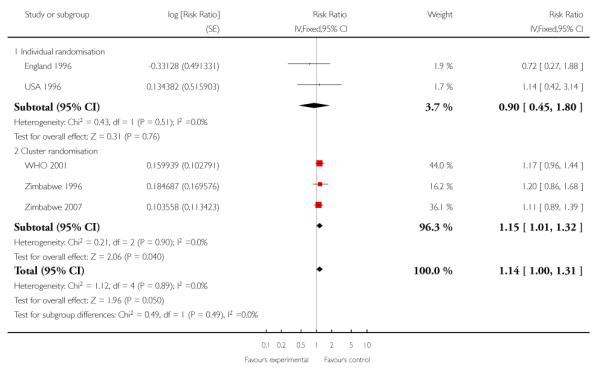

Perinatal mortality was increased for those randomised to reduced visits rather than standard care, and this difference was borderline for statistical significance (five trials; risk ratio (RR) 1.14; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 1.31). In the subgroup analysis, for high-income countries the number of deaths was small (32/5108), and there was no clear difference between the groups (2 trials; RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.80); for low- and middle-income countries perinatal mortality was significantly higher in the reduced visits group (3 trials RR 1.15; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.32). Reduced visits were associated with a reduction in admission to neonatal intensive care that was borderline for significance (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.02). There were no clear differences between the groups for the other reported clinical outcomes.

Women in all settings were less satisfied with the reduced visits schedule and perceived the gap between visits as too long. Reduced visits may be associated with lower costs.

Authors’ conclusions

In settings with limited resources where the number of visits is already low, reduced visits programmes of antenatal care are associated with an increase in perinatal mortality compared to standard care, although admission to neonatal intensive care may be reduced. Women prefer the standard visits schedule. Where the standard number of visits is low, visits should not be reduced without close monitoring of fetal and neonatal outcome.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Office Visits [utilization], Developed Countries, Developing Countries, Family Practice, Midwifery, Patient Satisfaction, Perinatal Mortality, Pregnancy Outcome, Prenatal Care [*standards; utilization], Program Evaluation, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Antenatal (also known as prenatal) care programmes, as currently practised, originate from models developed in Europe in the early decades of the past century (Oakley 1982). The concept arose from the (at that time) newly emerging belief in the possibility of avoidance of maternal death and also of fetal and infant death. In 1929, Dr Janet Campbell, a civil servant in the UK stated, “the first requirement of a maternity service is effective supervision of the health of the woman during pregnancy….” (Oakley 1982). Around this time, the UK Ministry of Health specified that antenatal examination should begin at around 16 weeks, and be followed by visits at 24 and 28 weeks, then fortnightly to 36 weeks and weekly thereafter (Oakley 1982). This guidance also laid out the content of the examination for each visit (such as measuring uterine height, checking the fetal heart and testing urine) and recommended those at 32 and 36 weeks be done by a medical officer. To our knowledge, these recommendations have formed the basis for antenatal care programmes throughout the world. As medical knowledge and technology have evolved, new components have been added to the routinely offered package of ante-natal care. These have primarily been screening interventions to improve identification of high-risk women. There have also been shifting patterns, and power struggles between obstetricians, primary care physicians and midwives, in who delivers or manages antenatal care for low-risk women (Loudon 1992). Since the inception of modern antenatal care, few of its common components have been formally evaluated, and there is little reliable evidence of the relative merits, hazards and costs of alternative packages of care. In the past, alternative schedules for the frequency of ante-natal care visits, the interval between visits, and the content of each visit have not been rigorously compared. Antenatal care has perhaps been rather more ritualistic than rational.

Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that antenatal care does confer some health benefits, although how it does so may be complex and multifactorial. One example which supports antenatal and intrapartum care having a major impact on outcome comes from the US; where women in the state of Indiana who belong to a religious group who do not seek antenatal care, and who give birth at home without trained attendants, have perinatal mortality three times higher, and maternal mortality 100 times higher, than other women in the state (Kaunitz 1984). However, few of the procedures commonly undertaken within antenatal care have been shown to have a major impact on maternal and perinatal morbidity or mortality, and some may have no effect. For others, there can be no impact unless other elements are also in place and functional. To further complicate the evaluation of antenatal care, there is a varying effect across populations and there may be different models and standards for care during childbirth which will also impact on outcome.

Observational studies tend to show that women who receive ante-natal care have lower maternal and perinatal mortality and better pregnancy outcomes. These studies also tend to demonstrate an association between the number of antenatal visits, and/or gestational age at the initiation of care, and pregnancy outcomes, after controlling for confounding factors such as length of gestation. Because of this suggested dose-response effect, antenatal care programmes often seek to increase the quantity of care provided without taking into account that, by and large, low-risk women attend for antenatal care earlier in pregnancy than high-risk women. In recent years, apart from frequency of visits and the intervals between the visits, attention has also been directed to the essential elements of the antenatal care package, to ensure that quality is not overlooked in favour of quantity. It has also been suggested that, perhaps, more effective care could be provided with fewer but ‘goal oriented’ visits, particularly focused on the components of antenatal care that have been proven to be effective and have an impact on substantive outcomes.

Rigorous evaluation of the comparative clinical and cost effectiveness of alternative strategies for provision of antenatal care are required, along with information about the perception of such care by women, their preferences, and those of the care providers. The economic implications of alternative antenatal care programmes are of particular importance in low and middle-income countries where resources are most scarce, but are also relevant in higher income/industrialised settings.

The key issue is not whether there is more or less antenatal care; rather it is that antenatal care should include only those activities supported by reasonable evidence of effectiveness and safety. The frequency of visits and the content of visits can then be planned accordingly. For overviews of systematic reviews on the effectiveness of different components of antenatal care, see Bergsjo 1997;Carroli 2001a; De Onis 1998; Gülmezoglu 1997; Villar 1997;Villar 1998.

This review aims to assess whether similar clinical outcomes can be achieved with reduced rather than standard antenatal care packages.

OBJECTIVES

The objectives are to compare the effects of antenatal care programmes providing a reduced number of antenatal care visits for low-risk women with programmes providing the standard schedule of visits, and to assess the views of the care providers and the women receiving antenatal care.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All acceptable randomised controlled trials comparing programmes of antenatal care with varied number of visits. We included quasi-random studies, such as those based on alternate allocation or allocation by days of the week. We included both cluster and individually randomised trials.

Types of participants

Pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics and considered (using criteria defined by the trialists) to be at low risk of developing complications during pregnancy and labour. We excluded studies that included primarily high-risk women. If any studies included both high- and low-risk women, where separate data were available, we planned to include only data for the low-risk women in the review.

Types of interventions

Provision of a schedule of reduced number of visits, with or without goal-oriented antenatal care, compared with a standard schedule of visits.

Types of outcome measures

We considered outcome measures this review mainly focusing on clinical outcomes including maternal, fetal and newborn outcomes. We also considered cost effectiveness and measures of perception of care by the women as well as care providers participating in the trials as important outcomes for the review. The list of outcomes includes the following:

Compliance with the allocated intervention

Number of antenatal visits

For the women

Primary outcomes

Pre-eclampsia

Maternal death

Secondary outcomes

Eclampsia

Gestational hypertension

Anaemia (haemoglobin less than 100 g/l)

Urinary tract infection (requiring treatment with antibiotics)

Caesarean section

Induction of labour

Antepartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (less than 500 ml, less than 1000 ml)

Stroke

Postnatal depression

Antenatal depression

Women’s views of antenatal care

Care providers’ views of antenatal care

Long-term emotional and physical wellbeing

For the babies

Primary outcomes

Baby death (stillbirth, perinatal death, neonatal death, infant death)

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks, less than 34 weeks)

Small-for-gestational age

Secondary outcomes

Low birthweight (less than 2500 g, less than 1500 g, less than 1000 g)

Admission to neonatal intensive care

Breastfeeding

Measure of long-term growth and development

Costs to the health services

Number of antenatal visits

Admission to hospital, length of stay in hospital

Admission to intensive care or neonatal intensive care, and length of stay

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (April 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of retrieved papers and personal communications and contacted principal investigators of included trials to obtain data on the relevant outcomes which were not reported in the original publication.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently assessed each citation for inclusion in the review. We resolved any differences in opinion by discussion. If we could not reach agreement, we consulted a third author.

Data extraction and management

For this update, two review authors independently extracted data from study reports using a standard form. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked all tables for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). We resolved disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence.

We assessed methods as:

adequate (where sequence generation was truly random, e.g. random number table, computer random number generator);

inadequate (odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment or changed after recruitment:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation, unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation, date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

Given the nature of the interventions evaluated, blinding of either the care providers or the women receiving care was not generally feasible. We have not formally assessed blinding, but we have noted where there was partial blinding, e.g. of outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We have indicated for each included study the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have stated the number lost to follow up (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusion where reported, and any re-inclusions in analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

adequate (e.g. where there were no missing data or where reasons for missing data were balanced across groups);

inadequate (e.g. where missing data may have related to outcomes or were not balanced across groups);

unclear (e.g. where there was insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(5) Selective reporting bias and other sources of bias

In the notes section of the included studies tables we have recorded any other concerns we may have had about bias. For example, where outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used, where a study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported, or where there was baseline imbalance between groups.

(6) Overall risk of bias

We have made explicit judgements about risk of bias for important outcomes both within and across studies. With reference to (1) to (5) above we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses, temporarily removing those studies at high risk of bias from the meta-analysis to see what impact this would have on the treatment effect.

Measures of treatment effect

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We have used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data in the absence of heterogeneity. For those outcomes where there were moderate or high levels of heterogeneity, where clinically meaningful, we used random-effects analysis and these results have been presented as average treatment effects.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but using different methods. If there was evidence in the trials of abnormally distributed data, we have reported this.

Unit of analysis issues

We have included three trials in the review where the unit of randomisation was the ‘clinic’ rather than the ‘individual’. For those outcomes where both types of trials contributed data, we conducted pooled analyses using the generic inverse variance method with subtotals by unit of randomisation. For the cluster-randomised trials, we adjusted standard errors to take account of the design effect using the methods described in Gates 2005 andHiggins 2009. We used an estimate of the intracluster correlation co-efficient (ICC) derived from the trial or from another source. For most of the outcomes considered in the review we used the ICCs from one of the included trials (WHO 2001) which have been published (Piaggio 2001). In the additional tables we have described the source of the ICC for each outcome, and we carried out sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of varying the ICC. We considered it reasonable to combine the results from both individually and cluster-randomised trials if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely. (In the results text we have set out findings separately for cluster and individually randomised trials.)

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we have noted levels of attrition in the risk of bias tables. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

Available case analysis

Where possible we have analysed all cases according to randomisation group irrespective of whether or not study participants received the intended intervention.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity between the trials by visually examining the forest plots to judge whether there were any apparent differences in the direction or size of the treatment effect between studies. We also considered the I2 and T2 statistics and the P value of the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. If we identified heterogeneity among the trials (if the value of I2 was greater than 30%, and the value of T2 was greater than zero or the P value of the Chi2 test for heterogeneity was greater than 0.1), we explored it by pre-specified subgroup analysis and by performing sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not formally assess reporting bias; without access to study protocols it is difficult to know whether or not there has been outcome reporting bias. However, we have noted in the Characteristics of included studies tables where we had any concerns about reporting bias (e.g. where key outcomes did not seem to be reported). We were unable to assess publication bias using funnel plots, as too few studies contributed data to the analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For this update, we have modified the protocol to include the following subgroup analyses:

based on geographic location: recruitment in high-income countries, recruitment in low- and middle-income countries, recruitment in both types of settings;

based on the number of visits in the reduced visits package: five visits or less, more than five visits;

based on parity: primiparous only, multiparous only, mixed primiparous and multiparous, parity unclear;

based on whether reduced visits were particularly focused on key components of antenatal care that have been proven to be effective, or whether the number of visits was simply reduced.

For fixed-effect meta-analysis we have carried out an interaction test to examine subgroup differences. For both fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis we examined the confidence intervals for subgroups; with overlapping confidence intervals potentially suggesting no important differences between subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

For this update, we have modified the protocol to include a sensitivity analysis based on temporarily excluding trials that used a quasi-random design or with high levels of attrition (more than 20%). If this exclusion led to a substantive difference in the overall results, we would exclude quasi-random studies or those with serious attrition.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Seven trials evaluated the number of visits; four of which were conducted in high-income countries (individual randomisation trials) (England 1996; USA 1995; USA 1996; USA 1997) and three in low- and middle-income countries (cluster-randomisation trials, with clinics as the unit of randomisation) (WHO 2001; Zimbabwe 1996; Zimbabwe 2007). All trials recruited both primiparous and multiparous women.

In the Zimbabwe 1996 study, there was simple randomisation of clusters, while the clusters in the Zimbabwe 2007 study were stratified according to whether or not radio communication was available, and then there was simple randomisation within strata. In theWHO 2001 trial, randomisation was stratified both by country and by clinic size. We have not been able to take this stratification into account in our analyses in this review. We have used the results from trials set out in published papers and have adjusted for the cluster design effect using the methods described in Higgins 2009 (so that all studies where clinics rather than individual women were randomised are analysed in the same way).

In all studies women were assessed at the antenatal booking visit for risk factors. In the studies where there was individual randomisation, women identified as having risk factors were excluded. In these trials gestation at recruitment was: before 13 weeks (USA 1996), before 18 weeks (USA 1995), before 22 weeks (England 1996), and before 26 weeks (USA 1997). Of the cluster-randomisation trials, two recruited all women attending antenatal clinics (WHO 2001; Zimbabwe 2007) whilst the third recruited all low-risk women (Zimbabwe 1996). In the WHO 2001 and Zimbabwe 2007 trials, women with risk factors were not excluded but may have received additional visits, or referral to a higher level of care, depending on their individual needs. In these studies analyses were according to randomisation group (intention to treat), so women with risk factors were included in the results (although women with risk factors may have received more visits than specified in trial protocols).

For the individual randomisation trials, standard care was specified as 13 visits for three trials. The fourth stated 14 visits (USA 1996). For the cluster-randomisation trials, one large international study stated standard as it was normally offered in that clinic (WHO 2001) and another stated standard care for rural areas (a survey indicated that the median number of visits before the intervention was seven) (Zimbabwe 2007). The third study specified 14 visits, but with the proviso that before the trial standard care was actually seven visits (Zimbabwe 1996). Reduced care was goal-orientated for the three cluster-randomised trials, with one trial using four visits (WHO 2001), one five visits (Zimbabwe 2007) and the third six visits (Zimbabwe 1996); assessment of risk factors at booking was an important part of these interventions. For the individual randomised trials, one used seven visits for nulliparous women and six for multiparous (England 1996); two used eight visits for all women (USA 1995; USA 1997); and one nine visits for all women (USA 1996). In one study, women in the reduced visits group had a single care provider, whilst women in the standard care group had a mix of care providers (USA 1995).

Risk of bias in included studies

Blinding of women and the providers of care was not feasible in any of these trials and this may be a source of bias.

Of the seven included trials: one used quasi-randomisation (USA 1995), in two concealment of allocation was not described (USA 1997; Zimbabwe 2007), and four were good quality studies having used a random sequence with adequate concealment of allocation (England 1996; USA 1996; WHO 2001; Zimbabwe 1996).

The study which used quasi-randomisation (USA 1995) also had large losses to follow up (27%), and care providers in the intervention arm also participated in the pool of providers conducting antenatal care in the control arm of the trial. Attrition was high in another trial, with 30% of women lost to follow up (USA 1997). Levels of attrition for other trials were less than 20%: 16% of women in one trial (USA 1996), 3% in two (England 1996;Zimbabwe 1996) and 2% in one (WHO 2001). For one study, full records were available for 78% of the women, but some outcome data were available for a further 20% of the sample (Zimbabwe 2007).

Full assessments of risk of bias are set out in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Effects of interventions

Comparison of reduced visits with standard care: seven trials with 60,724 women

Where we have pooled results from individual and cluster-randomised trials we have used the generic inverse variance method, and log risk ratios and standard errors/adjusted standard errors have been entered into the data and analyses tables. For these analyses, we have included additional tables where we have set out the original data from trials. We have also included in these tables the ICCs and details of the source of ICCs, used for calculating the design effect for the cluster-randomised trials. Where there were any differences in the way outcomes were defined in trials, we have provided details of the various definitions used. (See Table 1 to Table 2.)

Table 1 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Maternal death

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard visits | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomised trials | |||

| England 1996 | 1/1416 | 0/1378 | |

| USA 1996 | 0/1175 | 0/1176 | |

| Cluster randomised trials | |||

| WHO 2001 | 7/11672 | 6/11121 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0003 (WHO 2008). |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 6/9394 | 5/6138 | 7 clinics. ICC 0.0003 (WHO 2008) |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 4/6696 | 2/6483 | 23 clinics, ICC 0.0003 (WHO 2008) |

Table 2 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard antenatal care: Postnatal anaemia

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard visits | Number of clusters and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster randomised trial | |||

| WHO 2001 | 822/10720 | 876/10050 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0052 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

To provide context, before describing results for primary and secondary outcomes, we have described the impact of planned interventions in the included trials in terms of the number of antenatal visits made by women.

Compliance with the allocated interventions: number of antenatal visits

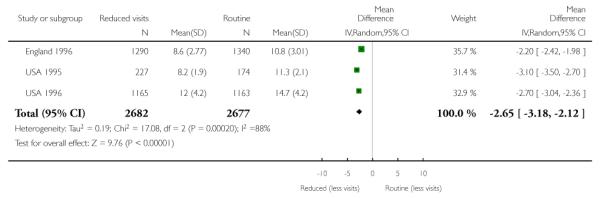

Six trials provided information on the number of antenatal visits women made, to assess compliance with the allocated intervention. Results are not simple to interpret, as the data were presented in different ways, and there was considerable variation within and between trials in the number of visits women received. In trials carried out in high-income countries, the reduced visits schedule generally involved considerably more visits than in trials in lower-resource settings. In three trials in high-income countries, the number of antenatal visits was reduced on average by 2.65 (95% confidence interval (CI) −3.18 to −2.12 (random effects analysis)), and in the “reduced visits” groups women, on average, attended between 8.2 and 12 (USA 1996) times (Analysis 1.1). There was considerable heterogeneity between these studies, and results should be interpreted with caution (I2 = 88%, T2 = 0.19 and Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.0002).

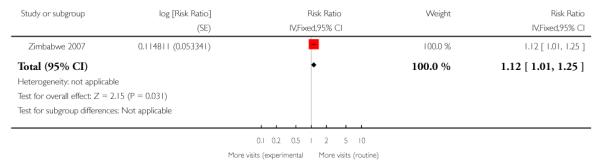

The reduction in the number of visits was of similar, or greater, magnitude in the trials carried out in low-resource settings where the standard number of visits was already relatively low, and where any reduction represented a considerably higher proportion of visits. Two trials show a relatively large reduction in the median number of visits: from six in the standard care group to four visits in the intervention group in the Zimbabwe 1996 trial, and from eight in the standard care group to four visits in the intervention group in the WHO 2001 trial. In the WHO 2001 trial it was reported that for women randomised to the reduced visits schedule and assessed as being at low risk at the booking visit, 51% had fewer than five antenatal visits; of those women with at least one risk factor, 37% had fewer than five visits. In the Zimbabwe 2007 trial, women in the reduced visits groups were more likely to attend on fewer than six occasions, but the difference between groups was not large, with 77% in the reduced visits group and 69% in the standard care group having five or fewer antenatal visits (risk ratio (RR) 1.12; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.25) (Analysis 1.2) (Table 3).

Table 3 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Fewer than five antenatal visits

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard visits | Source of ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 4106/5327 | 3561/5182 | ICC 0.041 taken from the Zimbabwe 2007 trial. |

Primary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

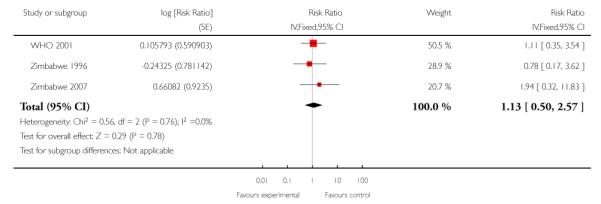

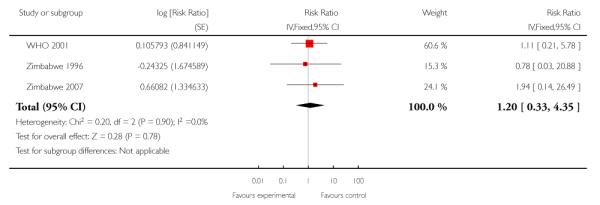

For maternal mortality, two individual randomisation trials (England 1996; USA 1996) reported this outcome, with one maternal death in 2405 deliveries in the reduced visits model and no maternal deaths in 2449 deliveries in the standard visits model. Three cluster-randomisation trials (WHO 2001; Zimbabwe 1996;Zimbabwe 2007) reported maternal mortality, with 17 maternal deaths in 27,762 deliveries in the reduced visits model with goal-oriented components, and 13 maternal deaths in 23,742 deliveries in the standard visits model; there was no statistically significant difference between groups (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.50 to 2.57) (Analysis 1.3) (Table 1).

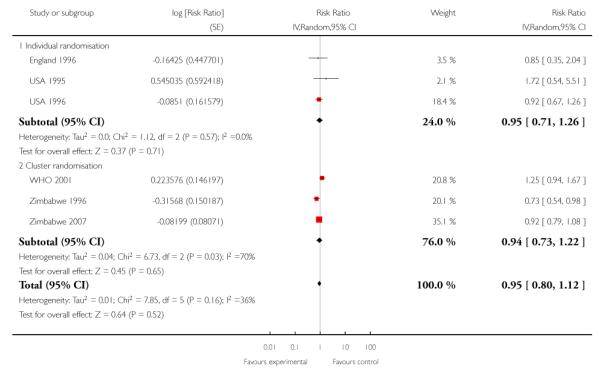

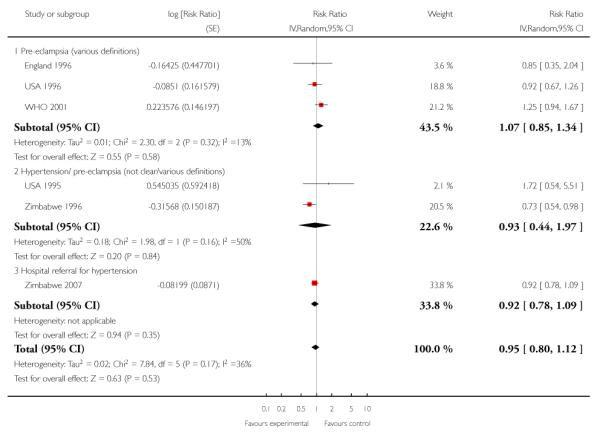

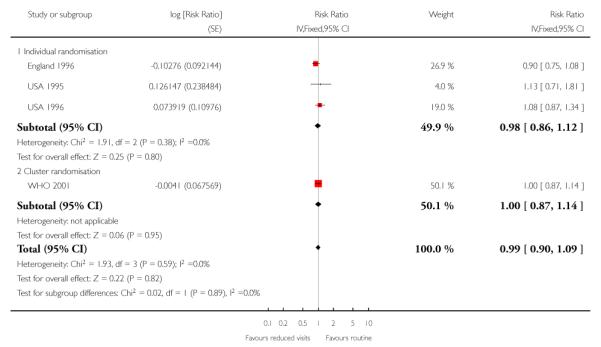

Intervention and control groups had similar levels of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including pre-eclampsia) (average RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.12 (random effects analysis)). However, these results should be interpreted with caution as definitions of pre-eclampsia varied between trials, and sometimes it was not clear whether the data were for gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia; this clinical heterogeneity may possibly explain the high levels of statistical heterogeneity between the cluster-randomised studies for this outcome (I2 = 70%, T2 = 0.04 and Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.03). In additional Table 4, we have set out the definitions of pre-eclampsia used in the various trials. (In Analysis 1.5 we have separated those trials reporting pre-eclampsia from those where the definition was not clear, or where data were reported for hypertensive disorders (possibly without proteinuria and other markers of pre-eclampsia).)

Table 4 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard care: pre-eclampsia

| STUDY ID | Definition of preeclampsia | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | ||||

| USA 1995 | PI hypertension | 9/227 | 4/174 | |

| USA 1996 | Mild and severe preeclampsia (BP > 140/90 (160/110) with proteinuria or edema) | 69/1165 | 75/1163 | |

| England 1996 | Pre-eclampsia (ISSHP definition) | 9/1240 | 11/1286 | |

| Cluster randomisation | ||||

| Zimbabwe 1996 | Referred to hospital for PI hypertension/ hypertension/eclampsia | 442/9394 | 396/6138 | 7 clinics .0098 ( hypertension WHO 2001; Piaggio 2001) |

| WHO 2001 | Preeclampsia (hypertension with proteinuria) PI hypertension | 189/11672 (402/11672) | 144/11121 (554/11121) | 53 clinics (pre-eclampsia 0.0018) (.0098 hypertension) WHO 2001; Piaggio 2001) |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | Hypertensive disorders - referred to hospital | 492/5324 | 522/5204 | 23 clinics .0098 (hypertension WHO 2001; Piaggio 2001) |

Neonatal outcomes

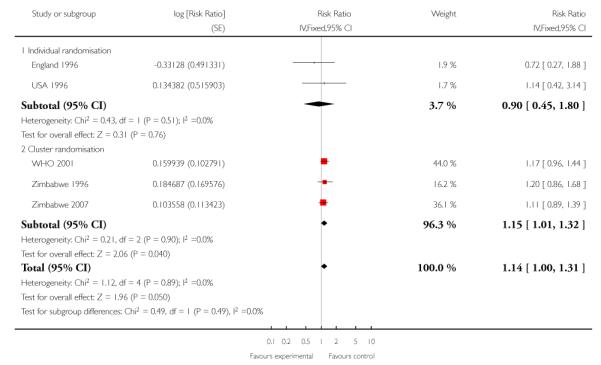

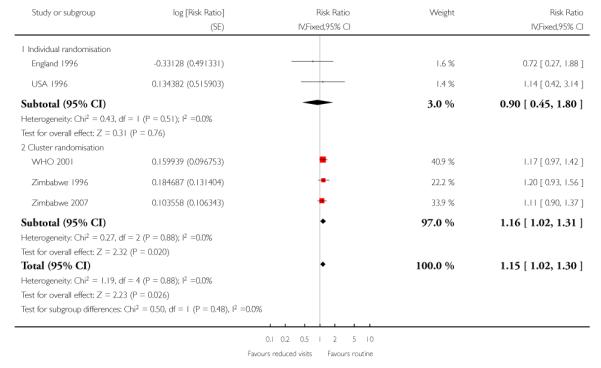

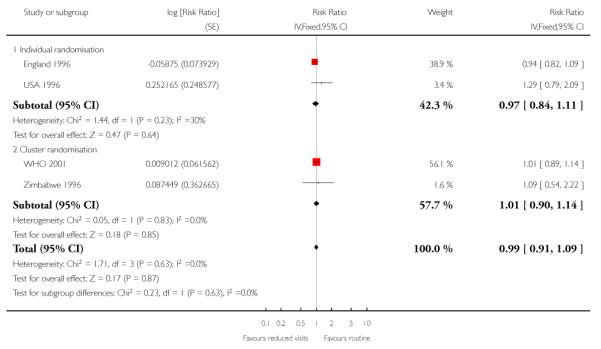

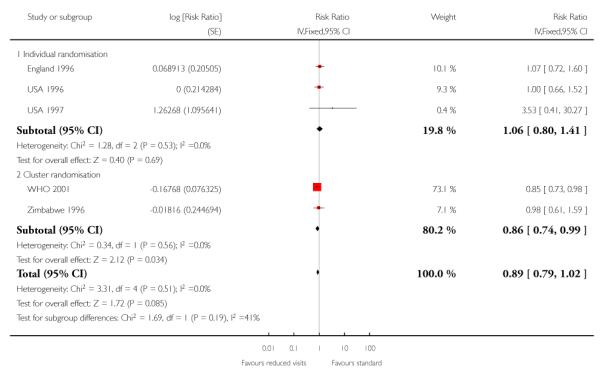

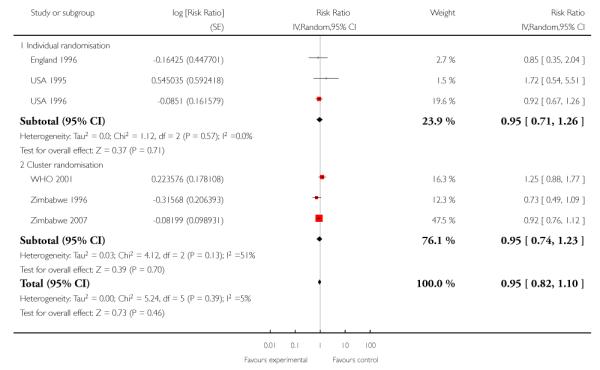

Perinatal mortality was increased for those randomised to the reduced visits group, and overall, this difference was borderline for statistical significance (five trials; RR 1.14; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.31). There was no evidence of a difference in treatment effects between trials conducted in high-income and low-/middle-income countries (test for subgroup differences P = 0.49, I2 = 0%). In the two individual randomisation trials conducted in high-income countries the number of deaths was relatively low (15/2536 versus 17/ 2572). In the three cluster-randomised trials conducted in low- and middle-income countries, perinatal mortality was higher in the reduced visits group, and this difference was statistically significant (581/27,680 in the reduced visits group versus 439/23,643 in the standard care group: RR 1.15; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.32).

The ICC used in this analysis for the cluster-randomised trials was derived from the WHO 2001 trial. We used the ICC representing the upper confidence limit for the average ICC for this outcome (Piaggio 2001). We also carried out a sensitivity analysis where the cluster design effect was not taken into account (the ICC was truncated to zero, as the average ICC had a negative value) and the difference between groups remained statistically significant for the cluster-randomised trials (RR 1.16; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.31) and the summary statistic (RR 1.15; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.30)) (Analysis 1.6 ICC 0.0003, Analysis 1.7 ICC truncated to zero, see Table 5).

Table 5 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Perinatal death

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| England 1996 | 7/1361 | 10/1396 | |

| USA 1996 | 8/1175 | 7/1176 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 234/11672 | 190/11121 | 53 clinics (ICC from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study −0.0006, truncated to zero to calculate design effect) Primary analysis uses upper confidence interval 0.0003 from the same source |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 162/9394 | 88/6138 | 7 clinics (ICC from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study −0.0006, truncated to zero to calculate design effect). Primary analysis uses upper confidence interval 0.0003 from the same source |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 185/6614 | 161/6384 | 23 clinics (ICC from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study −0.0006, truncated to zero to calculate design effect). Primary analysis uses upper confidence interval 0.0003 from the same source |

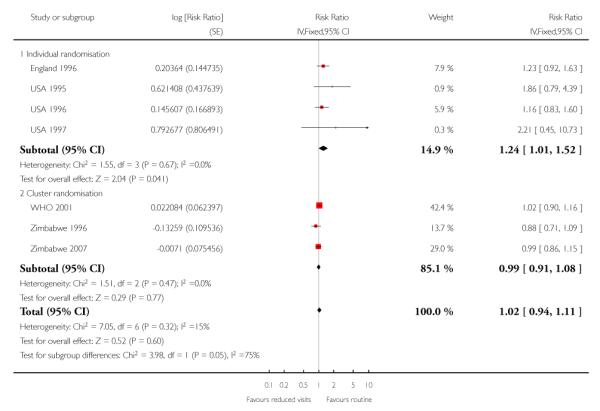

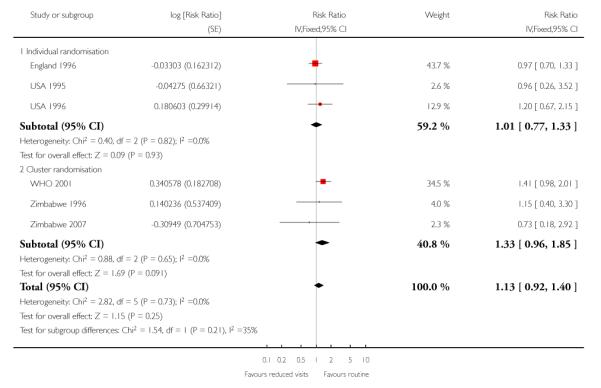

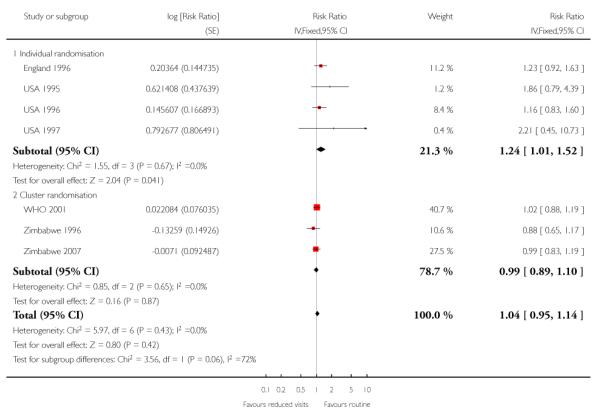

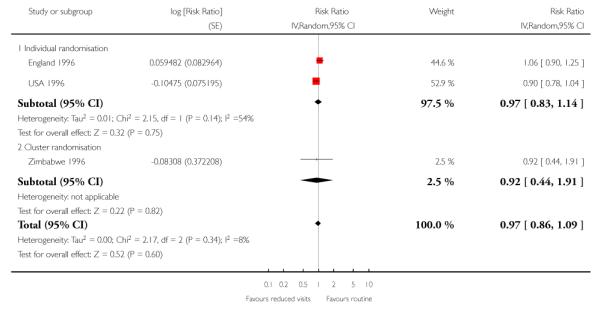

There was no clear difference in the number of preterm births in the two treatment groups (overall pooled RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.11). Although in the individual randomised trials there appeared to be more preterm births in the reduced visits group (RR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.52), no difference between groups was apparent in the cluster-randomised trials (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.08) (Table 6). The test of subgroup differences was of borderline statistical significance (P = 0.05) and the value of I2 for between subgroup heterogeneity was 74.9%.

Table 6 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Preterm birth

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| England 1996 | 98/1361 | 82/1396 | |

| USA 1995 | 17/227 | 7/174 | |

| USA 1996 | 73/1165 | 63/1163 | |

| USA 1997 | 5/43 | 2/38 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 910/11534 | 852/11040 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.002 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 945/9394 | 705/6138 | 7 clinics. ICC 0.002 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 599/5058 | 588/4930 | 23 clinics. ICC 0.002 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

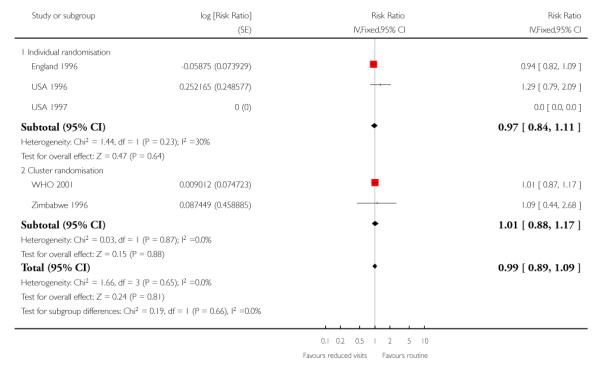

There was no clear difference between treatment groups for the numbers of babies that were small for gestational age (Analysis 1.9) (Table 7).

Table 7 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Small for gestational age

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| England 1996 | 277/1355 | 302/1393 | |

| USA 1996 | 36/1175 | 28/1176 | |

| USA 1997 | 0/43 | 1/38 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 1743/11440 | 1657/10974 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0065 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 304/9394 | 182/6138 | 7 clinics. ICC 0.0065 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

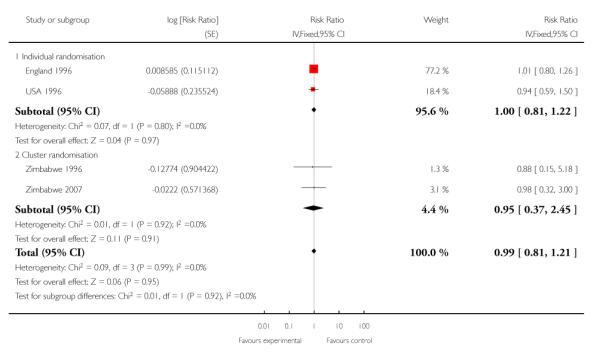

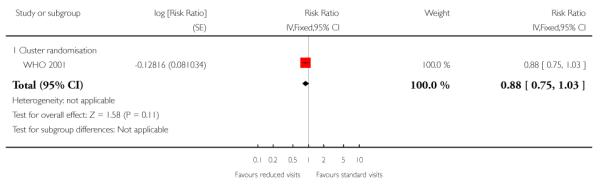

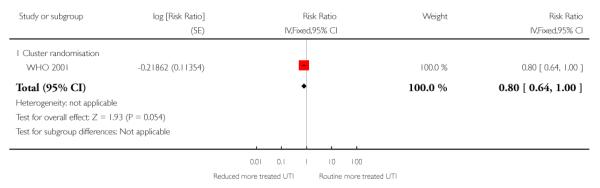

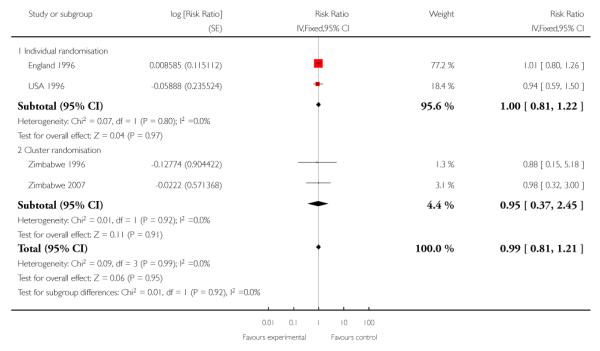

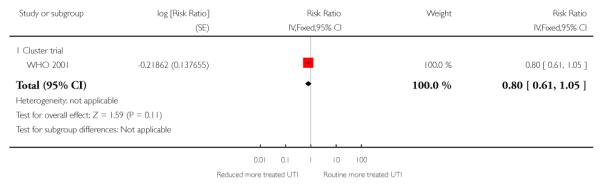

There was no clear difference between the groups in vaginal bleeding during pregnancy overall (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.40) or in either the individual randomisation trials (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.33) or the cluster-randomisation trials (RR 1.33; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.85). This finding should be interpreted with caution as (like pre-eclampsia) there was no single, clear definition of what antepartum haemorrhage was in these studies. In additional Table 8 we have set out the definitions used in each of the trials. There was no clear difference between groups for postpartum haemorrhage (pooled RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.21) (Analysis 1.11) (Table 9). With respect to severe postpartum anaemia and treated urinary tract infections, only one trial contributed data (WHO 2001). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups for either outcome (Analysis 1.14; Analysis 1.15) (Table 10; Table 2). The authors of the trial report recommend that results for postpartum anaemia should be viewed cautiously because there was heterogeneity between countries included in the trial for this outcome.

Table 8 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard care: Antepartum haemorrhage

| STUDY ID | Definition | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | ||||

| USA 1995 | Third trimester bleeding | 5/227 | 4/174 | |

| USA 1996 | Placental abruption plus placenta previa | 24/1165 | 20/1163 | |

| England 1996 | Antepartum haemorrhage | 70/1360 | 74/1391 | |

| Cluster trials | ||||

| Zimbabwe 1996 | Referral to hospital for antepartum haemorrhage | 81/9394 | 46/6138 | 7 Clinics 0.0034 ( WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001)). |

| WHO 2001 | Second and third trimester bleeding | 180/11672 | 122/11121 | 53 clinics 0.0034 ( WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001)). |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | Antepartum bleeding | 9/5239 | 12/5126 | 23 clinics 0.0034 ( WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001)) |

Table 9 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Postpartum haemorrhage

| Study ID | Definition | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | ||||

| England 1996 | Primary post-partum haemorrhage | 135/1358 | 137/1390 | |

| USA 1996 | 34/1165 | 36/1163 | ||

| Cluster randomisation | ||||

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 66/9394 | 49/6138 | 7 clinics. There was no published ICC for this outcome and so we used an estimated value of 0.01 and carried out sensitivity analysis using other values | |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 34/5238 | 34/5123 | 23 clinics |

Table 10 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard antenatal care: Treated urinary tract infection

| Study ID | Reduced Visits | Standard visits | Number of clusters and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 695/11672 | 824/11121 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0098 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

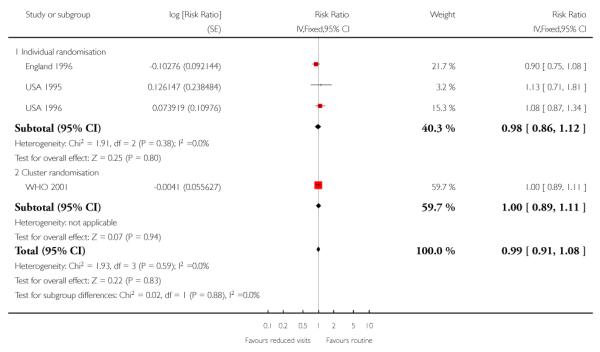

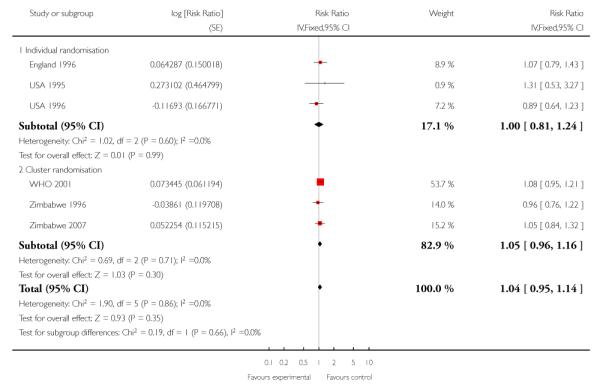

Similar numbers of women in the reduced visits and routine care groups underwent caesarean section (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.08) and the number of women undergoing induction of labour were similar in the two groups (average RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09) (Table 11; Table 12).

Table 11 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Caesarean section

| STUDY ID | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| USA 1995 | 37/227 | 25/174 | |

| USA 1996 | 151/1165 | 140/1163 | |

| England 1996 | 189/1360 | 215/1396 | |

| USA 1997 | 0/43 | 3/38 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 1640/11672 | 1569/11121 | 53 clinics ICC from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) 0.0044. |

Table 12 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard antenatal care: Induction of labour

| Study ID | Reduced Visits | Standard Care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| USA 1996 | 258/1165 | 268/1163 | |

| England 1996 | 244/1359 | 236/1395 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 300/9394 | 213/6138 | 7 clinics ICC from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001). There was no published ICC for induction of labour and so we used the ICC for elective CS (0.0044) |

Neonatal outcomes

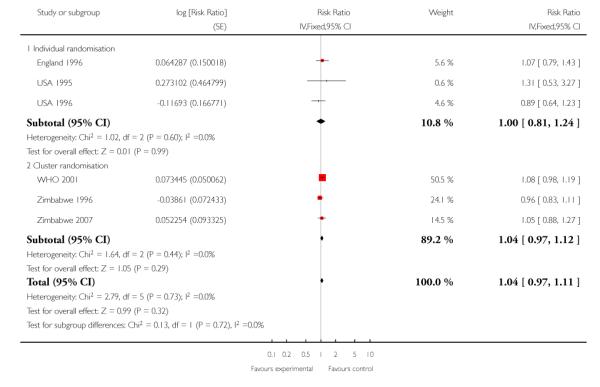

There was no clear difference between groups when the results were pooled with respect to low birthweight (less than 2500 g) (overall RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.11). The same pattern was observed for individual randomisation trials (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.24) and cluster-randomisation trials (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.12) (Table 13).

Table 13 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Low birthweight

| Study ID | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | |||

| England 1996 | 85/1356 | 82/1395 | |

| USA 1995 | 64/1175 | 72/1176 | |

| USA 1996 | 12/227 | 7/174 | |

| Thailand 1993a | 31/380 | 28/391 | |

| Cluster randomisation | |||

| WHO 2001 | 886/11534 | 788/11040 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0003 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | 723/9394 | 491/6138 | 7 clinics. ICC 0.0003 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

| Zimbabwe 2007 | 267/4280 | 227/3834 | 23 clinics. ICC 0.0003 from WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) study |

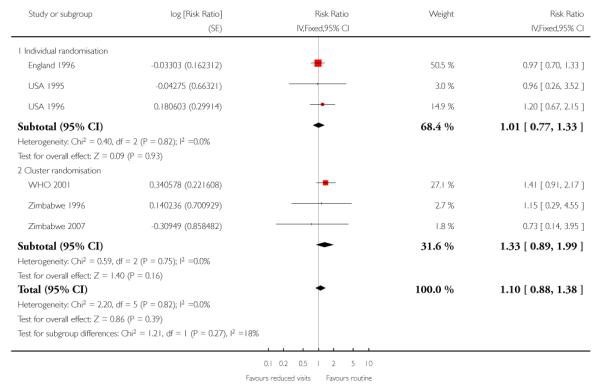

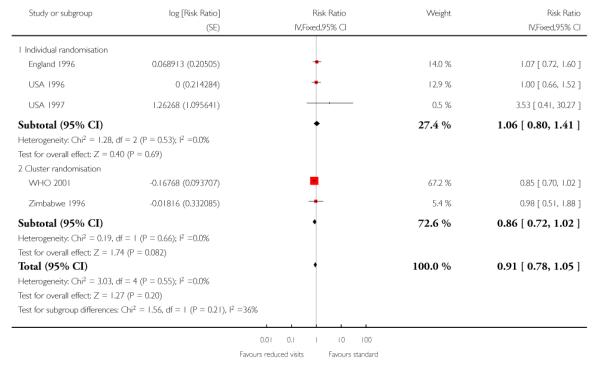

The number of babies admitted to neonatal intensive care units was similar in the two treatment groups in the trials carried out in high-resource settings (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.41); for trials in low-resource settings results appeared to favour the group having reduced visits (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99). Again, these results should be interpreted with caution as definitions of neonatal special care varied amongst the trials, and there were variations in how data on this outcome were reported (for example, the WHO 2001 trial provided data for those babies who received care in special units for more than two days) (Table 14).

Table 14 .

Reduced visits / goal oriented visits vs standard ANC: Admission to NICU

| Study ID | Definition | Reduced visits | Standard care | Cluster number and ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual randomisation | ||||

| USA 1996 | NICU admission | 42/1175 | 42/1176 | |

| England 1996 | Admission to special care unit/ NICU | 47/1359 | 45/1394 | |

| USA 1997 | NICU admission | 4/43 | 1/38 | |

| Cluster randomisation | ||||

| WHO 2001 | Admission to NICU for more than two days | 617/11397 | 700/10934 | 53 clinics. ICC 0.0024 ( WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) value for ICU stay of more than 2 days) |

| Zimbabwe 1996 | Not clear | 257/9394 | 171/6138 | 7 clinics. ICC 0.0024 (WHO 2001 (Piaggio 2001) value for ICU stay of more than 2 days) |

None of the studies included in the review provided information on breastfeeding at hospital discharge or in the postpartum period.

Satisfaction outcomes

There was considerable variation in the way satisfaction with care was measured between trials and in view of this variability, for most outcomes, results were not pooled.

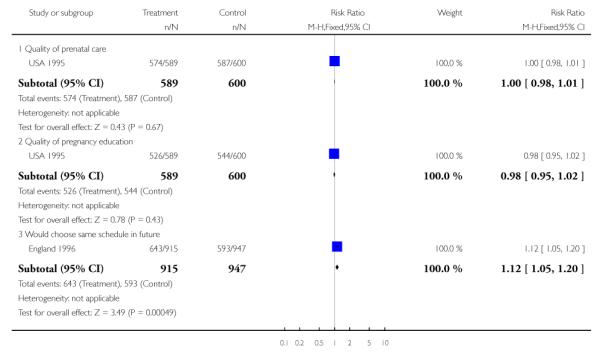

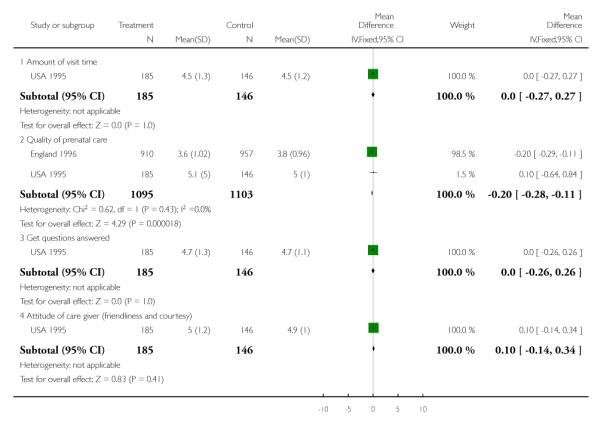

In individual randomisation trials, conducted in high-income countries, overall women tended to be less satisfied with the reduced number of antenatal visits model compared with standard care, although in the USA 1996 trial, where routine care involved 14 visits, some women perceived that the routine schedule involved too many visits.

In the England 1996 study women were asked about their overall satisfaction with the number of antenatal visits; those in reduced visits group were more likely to express dissatisfaction (32.5% were not satisfied compared with 16.2% in the routine care group). Women in the reduced visits group were also more likely to think that the gap between visits was too long (52.5%), although a third of those attending for the standard number of visits also perceived the gap was too long (33.4%). There was no difference between groups in terms of mean satisfaction with the general quality of antenatal care (Analysis 1.19).

In the USA 1995 trial, overall, more women in the routine care group expressed satisfaction with the number of antenatal visits (84% were satisfied in the routine care group compared with 71% in the reduced visit group). In the routine care group 6% thought that there had been too few and 10% too many visits, while in the reduced visits group only 2% thought there had been too many visits, whereas 27% thought there had been too few. In terms of other aspects of antenatal care (the quality of care, the amount of visit time, the quality of education, and the attitude of staff), the two groups had similar levels of satisfaction (Analysis 1.18; Analysis 1.19).

The USA 1996 trial also collected data on satisfaction with care, although data were not collected until six weeks postpartum. There was considerable loss to follow up with data on satisfaction outcomes available for only 43% of women randomised. Most women in both groups thought that the overall number of visits had been about right (89.2% in the reduced visit group and 82.8% in the routine care group agreeing). In the reduced visit group 8.8% thought they had had too few, and 2% thought they had had too many visits; conversely, in the standard visits group 1.5% thought they had had too few and 16.1% thought they had had too many visits. Women were also asked about the quality of other aspects of antenatal care, and most women in both groups expressed satisfaction (data not shown).

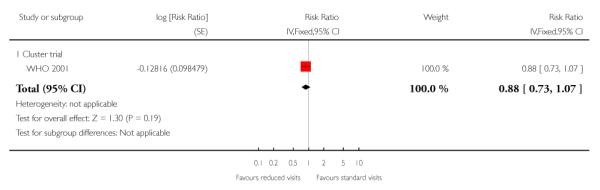

Two cluster-randomised trial reported findings on maternal satisfaction with antenatal care. In the Zimbabwe 1996 trial satisfaction was measured in a subset of women (100 from each arm of the trial) and there were no clear differences between groups (data not shown). In the WHO 2001 study 77.4% of women in the reduced visit group were satisfied with the number of visits compared with 85.2% of those in the standard visits group. Women in the reduced visits groups were less likely to be satisfied with the spacing between visits (72.7% satisfied compared with 81.0% in the standard visits group). Conversely, more women were satisfied with the amount of time spent during the visit in the reduced visits model (85.7% versus 79.1% in the standard visits group).

Only the WHO 2001 study reported providers’ perception of antenatal care and the results show that they were equally satisfied with the new model in respect to the number of visits (intervention group: 68.5%, control group: 64.5%) and information provided, but more satisfied with time spent with women (intervention group: 85.9%, control group: 69.5%).

Cost outcomes

Two trials (England 1996; WHO 2001) reported evaluation of the economic implications of the two models of antenatal care. The WHO 2001 trial included detailed economic analyses in two (Cuba and Thailand) of the four participating countries. The results obtained overall show that costs per pregnancy to women and providers were lower in the reduced visits model than in the standard visits model. The providers’ cost differences in Cuba and Thailand were respectively (mean difference (MD) −71.4 US$; 95% CI −148.8 to 2.5) and (MD −38.9 US$; 95% CI −46.3 to 30.9) favouring the reduced visits model. The women’s out of pocket costs were also less in the new model in both countries: Cuba (MD −68US$; 95% CI −144.0 to 7.7) and Thailand (MD −6.5US$; 95% CI −10.8 to −2.19). The average amount of time women spent attending visits was shorter in the reduced visits model in Cuba (MD −9.1 hours; 95% CI −13.5 to −4.7) and in Thailand (MD −14.9 hours; 95% CI −18 to 11.8).

An economic analysis using data from the England 1996 trial considered costs to the National Health Service only. Costs for the reduced number of visits model were £225 compared with £251 for the standard visits model, but there was an increase in the costs related to newborns’ length of stay in the intensive care unit from £126 in the standard antenatal visits model to £181 in the reduced visits model. This increase was due to an observed higher rate of neonatal admissions to special care in the reduced visits model compared to the standard visits model (3.5% versus 3.2%), as well as longer mean days of stay.

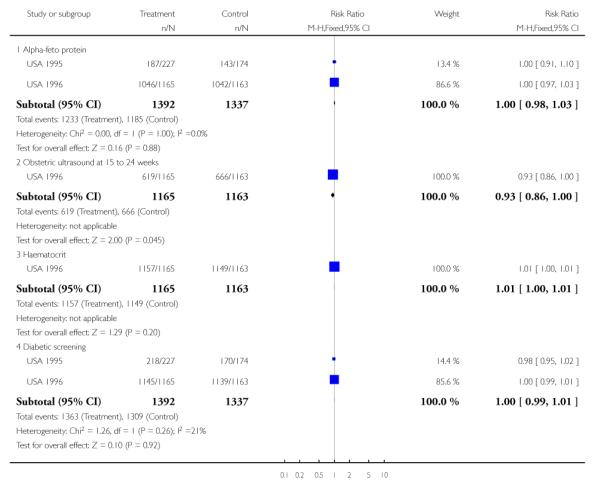

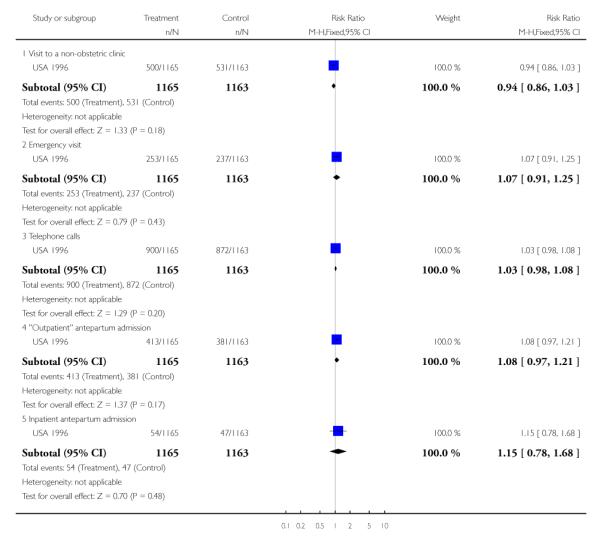

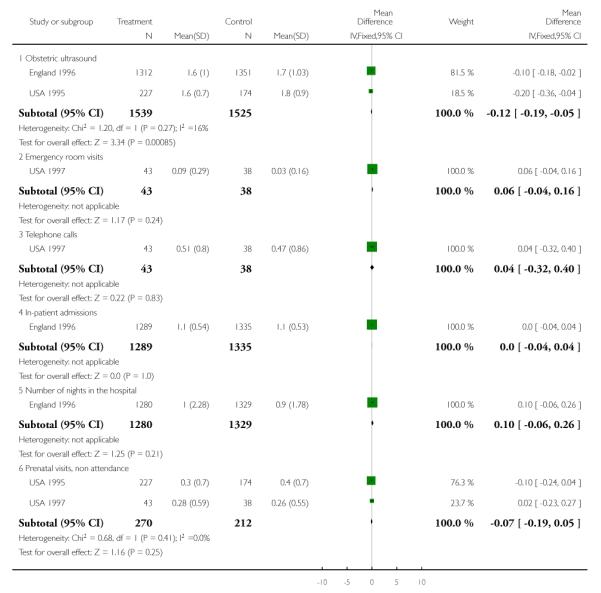

Process outcomes

There were few trials with data on indicators of service use. There was no evidence of differences between intervention and control groups in terms of use of prenatal diagnostic testing or use of other medical services. The mean number of ultrasound examinations was similar in the two trials providing such information (Analysis 1.20; Analysis 1.22).

Long-term outcomes

Follow up of 1117 women (60%) enrolled in the England 1996 trial at 2.7 years after delivery found no clear differences between the two groups in the mother-child relationship, maternal psychological well being, health service use for the mother and her child, health-related behaviour and health beliefs about herself and her child (data not shown).

Subgroup analysis

We planned subgroup analysis by high- versus low-resource settings, by more than five versus five or fewer visits and by whether or not the reduced programme included specific “goal-oriented” components. We have set out results for all outcomes according to method of randomisation (individual versus cluster-randomisation) in the data and analyses tables and in the text in the main results section. The trials carried out in high-resource settings were all studies where there was individual randomisation, whereas the cluster trials recruited women from low- or medium-resource settings. The number of antenatal visits also broadly corresponded to type of randomisation, with women in trials with individual randomisation in the reduced visits groups attending on more than five occasions compared with women in trials with cluster-randomisation who had an average of five or fewer visits and with visits focused on particular key components of care. In view of the correspondence between method of randomisation, resource setting, and the number and focus of visits, we did not therefore carry out further subgroup analysis using these variables. Separating the studies by method of randomisation revealed few important differences in findings between individual and cluster-randomised trials; for one outcome (preterm birth Analysis 1.8) there appeared to be limited overlapping of confidence intervals and the test for subgroup differences was of borderline statistical significance, but in view of the large number of outcomes examined, this finding may have occurred by chance.

We also planned subgroup analysis by parity but data were not available to allow us to perform this analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Study quality

Two of the studies that we included were at high risk of bias. The USA 1995 was quasi-randomised and had more than 20% loss to follow up and the USA 1997 trial also had high attrition. Temporarily removing these two studies from the analysis for all clinical outcomes to which they contributed data had very little impact on overall results, or on the magnitude of the P values for the overall treatment effect (data not shown).

Varying the ICCs for cluster-randomised trials

In comparison two we have set out sensitivity analysis using conservative estimates of the ICC for clinical outcomes; we selected the upper 95% confidence limit for the ICCs used in the main analysis. Although selecting more conservative ICC values (assuming more clustering and thereby reducing the weight of cluster-randomised trials) broadened the confidence intervals slightly for some outcomes, overall, this did not have any serious impact on findings (Analysis 2.1 to Analysis 2.13).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

For most of the outcomes examined in this review, there were no significant differences between groups receiving a reduced schedule of antenatal visits with goal-oriented care compared with standard antenatal care. The key outcome for which there seems to be a difference is perinatal mortality, which was increased by 14% (95% CI 0% to 31%) in the reduced visits group compared to standard antenatal care. In the subgroup analysis, the was no clear evidence of a difference in treatment effects between trials conducted in high and low resource settings (test for subgroup differences P = 0.49, I2 = 0%), although the number of perinatal deaths in the high-resource setting studies was small and hence power was limited. Other clinical outcomes for mothers and babies, and interventions in labour, were similar for women in the two study groups.

Women in both low- and high-resource settings were less satisfied with the reduced schedule of visits; for some women the gap between visits was perceived as too long. Economic analyses in two trials suggest that reduced visits may be associated with lower costs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Antenatal care is a complex intervention, and understanding how the evidence presented in this review should be applied in practice is not simple. First, there were considerable differences between studies in what constituted standard care, as well as what constituted reduced visits care. These differences were particularly marked between trials carried out in high- rather than low-resource settings. In low-resource settings the standard number of antenatal visits was considerably lower than for standard care in studies carried out in high-income countries. For the reduced visits intervention, trials in low-resource settings combined reducing the number of visits (to between four and six) with a review of what activities should be conducted within those visits. The aim was to only include activities for which there was evidence of improved outcome.

For trials in higher-income countries, the focus was on simply reducing the number of visits: from 13 to 14 visits with standard care to between six and nine with reduced visits. The planned number of visits in the reduced arm was therefore relatively high compared to the trials in low-resource settings.

In the trials in high-income countries the recommended schedule of visits was not strictly followed in either group, so women in the intervention arm tended to have more visits than planned, and women in the control arm tended to have fewer visits than planned. In these trials, women in the reduced visits group may have attended for more visits than women in the standard care group in trials carried out in low- and middle-income countries. Eligibility criteria varied between the different studies. Although the reduced visits schedule was intended for low-risk women, in two of the cluster trials women with risk factors identified at the booking visit were not excluded; although these women may have received individualised care (with referral or additional visits) they are included in the analyses. Separate results were not available for those women identified with risk factors.

Perinatal mortality in these trials was relatively low for the settings in which they were conducted. In the control groups, for the high-resource setting trials perinatal mortality was in the range of five to seven deaths per 1000 births, and for the low-resource setting trials it ranged from 14 to 25 deaths per 1000 births. The increase in perinatal mortality associated with reduced visits is concerning. The increase is borderline for statistical significance (point estimate 14% increase, 95% CI 0% to 31%), but is consistent in the sensitivity analyses using study quality and ICC. In the subgroup analysis by unit of randomisation, the increase in perinatal mortality is statistically significant in the cluster-randomised studies (15% increase, 95% CI 1% to 32%), but not in the individual randomised studies where the confidence intervals are wide and cross the no effect line (10% reduction, 95% CI 55% reduction to 80% increase). The individual randomised studies contribute just 4% of the weight in this analysis. As unit of randomisation also divides the trials based on low- and high-resource settings, it is impossible to disentangle these two characteristics.

For the WHO 2001 study, data were available for fetal and neonatal deaths separately (for the other cluster-randomised trials data were either not available, or incomplete). Results from the WHO 2001 trial indicate that the difference in perinatal deaths was due to increased stillbirths amongst the reduced visits group compared with the standard care group. The number of neonatal deaths was very similar in both arms of this trial (see Table 15).

Table 15 .

Reduced visits/ goal oriented visits vs standard care: fetal and neonatal deaths in the WHO 2001 trial

| Reduced visits N = 11672 |

Standard visits N = 11121 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fetal death ≤ 36 weeks | 122 | 77 |

| Fetal death > 36 weeks | 37 | 42 |

| Neonatal death before hospital discharge | 73 | 71 |

| Perinatal mortality | 234 | 190 |

There are a number of possible explanations for the observed increase in fetal deaths in the WHO 2001 study and in perinatal deaths in the two other trials carried out in low-income settings (Zimbabwe 1996; Zimbabwe 2007). It is possible that with only two or three visits scheduled in the third trimester, staff caring for women receiving reduced visits may not have been able to pick up serious problems at a point where early detection and prompt treatment may have had an impact on outcome, and with so few visits subtle changes indicating changes over time may not have been easy to detect.

There were no clear differences in the reported measures of perinatal morbidity. There was no clear difference in preterm birth (risk ratio (RR) 1.02; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.11) or being small-for-gestational age (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.09). For admission to neonatal intensive care, there was a reduction in admission that was borderline for statistical significance (point estimate 11% reduction; 95% CI 21% reduction to 2% increase). This difference was statistically significant in the cluster-randomised trials (14% reduction; 95% CI 26% reduction to 1% reduction) but not in the individual randomised trials (6% increase; 95% CI 20% reduction to 41% increase). Perinatal death and admission to neonatal intensive care are related outcomes. For example, if more sick babies die before they can be admitted to a neonatal unit, perinatal mortality will go up and admission to neonatal intensive care will go down. Also, it is not clear in some trial reports whether babies who subsequently died were excluded from the data on admission to neonatal intensive care. Reduced admission, or shorter length of stay is not an advantage if this is due to an increase in mortality. No trials have reported long-term follow up of babies, so there are no data on whether these alternative packages of antenatal care are associated with any changes in long-term outcome.

Although for most other outcomes the differences between groups were not statistically significant, results for some are difficult to interpret as the outcomes were not well defined, e.g. pre-eclampsia and antepartum bleeding. Furthermore, understanding the impact of antenatal visits on these outcomes may not be straightforward; it may be that a larger number of minor problems are detected with more visits, but higher levels of detection do not necessarily mean greater morbidity.

It is not clear from the results of this review whether maternal dissatisfaction with the reduced visits related to women’s expectations or to experience in a previous pregnancy; in the high-income countries in particular, it may be that dissatisfaction would not persist if a reduced schedule of visits was the norm. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that women seem to like attending for antenatal care. In the trials where they were asked, women tended to prefer standard care, and in the reduced visits group many perceived that the gap between visits was too long. Antenatal care may offer women reassurance and a source of support during what may be a time of major social upheaval. There is also an opportunity for women to discuss their psychological wellbeing with healthcare providers and other pregnant women, and this may help them to prepare for the transition to motherhood. These less tangible aspects of antenatal care may be important as far as women are concerned.

There was some evidence that a reduced schedule of visits may be associated with reduced costs to health services, although this was not generally measured in trials, and the data that are available are not consistent and not easy to interpret; apparent reductions in service utilisation (reduced visits) may not result in any cost savings to service providers unless resources and staff are redeployed.

Quality of the evidence

In general, the trials were of acceptable quality with low or moderate risk of bias, except for the USA 1995 trial where the possibility of bias was high. We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding this trial, and this did not substantially alter the results. In several trials levels of attrition were high, and this was particularly true for data collected in the postpartum period; data on maternal satisfaction may be at higher risk of bias because of loss to follow up. It was not possible to blind women or care providers, and due to the unblinded and pragmatic nature of these trials, some degree of protocol deviation, contamination and co-intervention should be expected in all of them.

Our meta-analysis included trials that used the individual as the unit of randomisation (individual randomisation trials) and those that used clinics (cluster-randomisation trials). We presented both pooled and stratified meta-analyses by the two types of trials. The ICCs used in the primary analyses were predominantly from theWHO 2001 trial and have been published (Piaggio 2001). We stratified the meta-analyses in individual and cluster-randomisation trials because in addition to the unit of randomisation being different, the reduced number of antenatal visits model in the cluster-randomisation trials contained goal-orientated components, while in individual randomisation trials the aim was only to reduce the number of visits. Furthermore, the method of implementing the intervention (clinic policy versus individual schedule), the site of the trials (low-resource versus high-resource settings), the proportional reduction in the number of visits (large versus small) and the sample size (large versus small) are clearly different in the two types of trials. Although for some outcomes we have provided pooled estimates, in view of the differences between studies, these should be interpreted with caution.

For a small number of outcomes (e.g. pre-eclampsia) there were high levels of statistical heterogeneity. The differences between trials may be partly explained by different outcome definitions in different trials. In the presence of heterogeneity we decided either not to combine trials (and have provided subtotals only), or to use a random-effects model to produce an average treatment effect. We are aware that where there are high levels of unexplained heterogeneity, pooled results must be interpreted with caution.

Potential biases in the review process

We are aware of potential biases in the reviewing process; and we took some steps to minimise bias (e.g. two authors independently carried out data extraction).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are some differences between this updated review and the previous version. In this review we have used new methods for the assessment of risk of bias and in the analyses (Higgins 2009), and this may have had an impact on results. For example, we have used a new method of analysis for the cluster trials so that all cluster trials have been analysed in the same way, and data from individual and cluster-randomised trials have been pooled in the analysis inRevMan 2008. We have also used risk ratio rather than odds ratio, as risk ratio is easier to understand. The choice of statistical method may alter the way results are presented and the way results are interpreted.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Reducing the number of antenatal care visits is an attractive option for providers of maternity care. The results of this updated review suggest that reduction in the number of visits, even when the content of visits is modified to be more ‘goal-orientated’, compared to standard care is associated with an increase in perinatal mortality in low- and middle-income settings. It would therefore seem prudent not to reduce the number of visits in settings where the standard number of visits is already low without very close monitoring of fetal and neonatal outcomes.

Results of this review underline the importance of rigorous evaluation of substantive changes in antenatal care programmes, before they are introduced into practice and policy.

Implications for research

Antenatal care is a complex intervention delivered in a wide variety of ways in different countries and different settings. Results from individual trials may not be generalisable to other types of population and settings.

Findings from this review suggest that future research comparing alternative programmes of antenatal care should include close monitoring of the fetus, and pay particular attention to fetal and newborn outcome. If studies include high-risk and low-risk women, outcome data for these groups should be presented separately. The interventions in both standard care and the new intervention should be clearly described, with information about the content of care as well as the number of visits. Outcomes should be clearly defined, using widely agreed definitions. Outcomes should include measures of mortality and morbidity for the woman and child, as well as costs to health services and families, and women’s satisfaction with care. This would make results of such trials easier to interpret and apply in clinical practice and health policy.

Future trials should also plan long-term follow up, to assess whether any differences in short-term outcome are reflected in the longer term health and wellbeing of the woman or her child. Ideally such follow up should be when the children are at least 18 months of age, as this is the earliest that neurodevelopment can be assessed reliably.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Alternative packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnant women

A routine number of visits for pregnant women has developed as part of antenatal or prenatal care without evidence of how much care is necessary to optimise the health of mothers and babies, and is helpful for the women. These visits can include tests, education and other health checks. The review set out to compare studies where women receiving standard care were compared with women attending on a reduced number of occasions. We included seven randomised controlled trials involving more than 60,000 women. The trials were carried out in both high-income (four trials) and low- and middle-income countries (three trials). In high-income countries the number of visits was reduced to around eight. In lower-income countries many women in the reduced visits group attended for care on fewer than five occasions, although the content of visits was altered so as to focus on specific goals. In this review there was no strong evidence of differences between groups receiving a reduced number of antenatal visits compared with standard care on the number of preterm births or low birthweight babies. However, there was some evidence from these trials that in low- and middle-income countries perinatal mortality may be increased with reduced visits. The number of inductions of labour and births by caesarean section were similar in women receiving reduced visits compared with standard care. There was evidence that women in all settings were less satisfied with the reduced schedule of visits; for some women the gap between visits was perceived as too long. Reduced visits may be associated with lower costs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the investigators of all the trials who provided additional unpublished information, particularly Dr Jim Sikorski, Dr Stephen Munjanja, Dr Gunilla Lindmark, and Dr Franz Majoko. We are also grateful to Prof Miranda Mugford, Dr Pisake Lumbiganon, Dr Ubaldo Farnot, and Dr Per Bersgjo for their comments and suggestions on the earlier drafts of the review. We thank José Villar for his contribution to the previous version of this review.

As part of the pre-publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s international panel of consumers and the Group’s Statistical Adviser.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

HRP-UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/WORLD BANK, Switzerland.

University of Leeds, UK.

The University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

TD is supported by the NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme grant scheme award for NHS-prioritised centrally-managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS02

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 3252 low-risk women booked for ANC before 22 weeks’ gestation in any of the sites participating in the study (clinics, hospitals etc) Exclusions: women with a history of complications in a previous pregnancy, with a previous low birthweight baby, medical complication (including hypertension, diabetes, psychiatric, renal or cardiac disease), < 16 or > 39 years of age, known substance abuser, weighing < 41 kg or > 100 kg, or multiple pregnancy |

|

| Interventions | Reduced visits: for nulliparous women - 7 visits (at 24, 28, 32, 36, 38, 40 weeks + booking visit). Multiparous women: 6 visits (at 26, 32, 36, 38, 40 weeks + booking visit). Standard ANC: 13 visits (at 16, 20, 24, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 weeks + booking visit) |

|

| Outcomes | Women: pre-eclampsia (defined according to the criteria of the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP)), hypertension, caesarean section, undiagnosed malpresentation, IOL, length of labour, APH, PPH. Babies: perinatal death, small-for-gestational age (< 3rd centile and < 10th centile), Apgar at 1 and 5 minutes, admission to SCBU. Health service use: antenatal or day admission, number of ultrasound scans, continuity of care. Psychosocial: social support during or after pregnancy, worry about pregnancy and the well being of the fetus, attitudes to fetus and baby. Maternal and professional acceptability of the new style of care |

|

| Notes | In the reduced visits group the mean number of visits was 8.6 (7 planned). In the control group the mean number of visits was 10.8 (13 planned) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Random permuted blocks of 8 and 16, stratifying by the 6 offices at which the recruiting midwives were based |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Concealment of allocation: sequentially numbered, non-resealable opaque envelopes |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | Loss to follow up: 68/1446 (4.7%) in reduced visits group and 30/1446 (2.1%) in the standard ANC group |

| Methods | ‘Quasi-random’ trial. Randomisation was not 1-to-1, as the aim was to include more women in the intervention arm | |

| Participants | 549 low-risk women < 18 weeks’ gestation. 1566 women were informed about the study, of whom 159 were ineligible because of risk factors, 809 declined to participate and 49 were beyond 18 weeks’ gestation |

|

| Interventions | Reduced visits: 8 expected antenatal visits. Each woman assigned 1 care provider for the entirety of her antenatal care. Control: 13 expected visits. Each visit was potentially with a different care provider. |

|

| Outcomes | Women: caesarean section, woman’s satisfaction (scale 1-6). Babies: preterm birth (< 37 weeks), low birthweight (< 2500 g), Apgar at 5 minutes < 7 |

|

| Notes | Number of visits achieved: reduced visits group 8.2 (SD 1.9) and standard ANC group 11.3 (SD 2.1) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | No | Quasi-random by birth date. |

| Allocation concealment? | No | Based on date of birth. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | Loss to follow up: 93/320 (29%) in the reduced visits group and 55/229 (24%) in the standard ANC group |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 2764 low-risk women aged 18-39 years booking at any of the participating sites before 13 completed weeks’ gestation. Excluded if past or current high-risk obstetric condition, current medical condition, non-English speaking or planning to change insurance carriers during pregnancy |

|

| Interventions | Reduced visits: 9 visits (at 8, 12, 16, 24, 28, 32, 36, 38 and 40 weeks). For parous women a telephone call was scheduled at 12 weeks instead of a visit. Standard ANC: 14 visits (visits every 4 weeks from 8 to 28 weeks, every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, and weekly thereafter) |

|

| Outcomes | Women: mild and severe pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, preterm labour, preterm premature rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis (clinical), abruptio placentae, placenta previa, and PPH (> 750 ml for vaginal delivery and > 1500 ml for caesarean delivery). Babies: stillbirth (> 20 weeks), preterm birth (< 37 weeks), and low birthweight (< 2500 g), gestation at birth, birthweight, small-for-gestational age (< 10th percentile), very low birthweight (< 1500 g), Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes, and stillbirth. Women’s satisfaction: with prenatal care, education during prenatal visits and educational material |

|

| Notes | Mean number of visits in the reduced visits group was 12.0 (SD 4.2) and in standard ANC group 14.7 (SD 4.2) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Random number tables. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Concealment of allocation: sealed, opaque envelopes contained details of group allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | Loss to follow up: 217/1382 (15.7%) in the reduced visits group and 219/1382 (15.8%) in the standard ANC group |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | 122 women with a low-risk pregnancy (met criteria for birthing centre), booking before 26 weeks of gestation, older than 18 years of age, and who could read Spanish or English | |

| Interventions | Reduced visits: 8 visits (booking + 15-19 weeks, 24-28 weeks, 32 weeks, 36 weeks, 38 weeks, then weekly until delivery) for all women regardless of parity. Standard ANC: standard visits (booking, then every 4 weeks to 28 weeks, every 2 weeks to 36 weeks, then weekly to delivery) |

|

| Outcomes | Women: number of visits attended, maternal complications, preterm labour, anaemia, recurrent UTI, pregnancy-induced hypertension, fetal malposition, substance abuse, post dates and others Babies: gestational age at birth, birthweight, average weekly weight gain, type of birth, Ballard score, intrauterine growth restriction, days in the newborn nursery, days in the neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal complications |

|

| Notes | Number of visits achieved: reduced visits group 7.6 (SD 1.6), standard ANC group 10.8 (SD 2.3) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer-generated sequence stratified by 11 personal, clinical and demographic characteristics |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Concealment of allocation: not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | Loss to follow up: 37 (30%) withdrew, 18/61 (30%) in reduced visits group and 19/61 (31%) in standard ANC group |