Abstract

Background

Although clozapine has been shown to be the treatment of choice in people with schizophrenia that are resistant to treatment, one third to two thirds of people still have persistent positive symptoms despite clozapine monotherapy of adequate dosage and duration. The need to provide effective therapeutic interventions to patients who do not have an optimal response to clozapine is the most common reason for simultaneously prescribing a second antipsychotic drug in combination with clozapine.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and tolerability of various clozapine combination strategies with antipsychotics in people with treatment resistant schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2008) and MEDLINE (up to November 2008). We checked reference lists of all identified randomised controlled trials and requested pharmaceutical companies marketing investigational products to provide relevant published and unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included only randomised controlled trials recruiting people of both sexes, aged 18 years or more, with a diagnosis of treatment-resistant schizophrenia (or related disorders) and comparing clozapine plus another antipsychotic drug with clozapine plus a different antipsychotic drug.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and resolved disagreement by discussion with third member of the team. When insufficient data were provided, we contacted the study authors.

Main results

Three small (range of number of participants 28 to 60) randomised controlled trials were included in the review. Even though results from individual studies did not find that one combination strategy is better than the others, the methodological quality of included studies was too low to allow authors to use the collected data to answer the research question correctly.

Authors’ conclusions

In this review we considered the risk of bias too high because of the poor quality of the retrieved information (small sample size, heterogeneity of comparisons, flaws in the design, conduct and analysis). Although clinical guidelines recommend a second antipsychotic in addition to clozapine in partially responsive patients with schizophrenia, the present systematic review was not able to show if any particular combination strategy was superior to the others. New, properly conducted, randomised controlled trials independent from the pharmaceutical industry need to recruit many more patients to give a reliable estimate of effect or of no effect of antipsychotics as combination treatment with clozapine in patients who do not have an optimal response to clozapine monotherapy.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Antipsychotic Agents [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]; Clozapine [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]; Dibenzothiazepines [therapeutic use]; Drug Resistance; Drug Therapy, Combination; Piperazines [therapeutic use]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Risperidone [therapeutic use]; Schizophrenia [*drug therapy]; Sulpiride [analogs & derivatives; therapeutic use]; Thiazoles [therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Male

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

One fifth to one third of people with schizophrenia are considered to to be resistant to treatment. This usually means these people have persistent psychotic symptoms and poor functioning despite adequate treatment with conventional or novel antipsychotic drugs (Conley 2001). For these people clozapine has been shown to be the treatment of choice (Kane 1988; Rosenheck 1997; Wahlbeck 1999), with few adverse effects that result in movement problems and a beneficial effect in terms of mental state and suicide mortality (Hennen 2005).

Description of the intervention

Clozapine is, however, only effective in producing clinically significant symptom improvement in 30-50% of people receiving treatment. One third to two thirds of people still have persistent ’positive’ symptoms despite clozapine monotherapy of adequate dosage and duration (Chakos 2001). Under real-world circumstances, the need to provide effective therapeutic interventions to patients who do not have an optimal response to clozapine has been cited as the most common reason for simultaneously prescribing two or more antipsychotic drugs in combination treatment strategies (Sernyak 2004).

How the intervention might work

Antipsychotic drugs block central dopamine receptors and most of the second generation antipsychotics also have an action on serotonin receptors and many other neuroreceptors (Arnt 1998). However, how these drugs may exactly work as combination treatment on clozapine-resistant patients with schizophrenia is still unknown.

Why it is important to do this review

The literature is dominated by case reports and open studies while the evidence from randomised controlled trials is limited and contradictory in terms of findings (Mouaffak 2006). Methodological shortcomings of randomised evidence have additionally been shown to decrease the impact of study results on treatment recommendations (Kontaxakis 2005; Remington 2005). A protocol for a Cochrane systematic review has already been published to assess the efficacy and safety of antipsychotic combinations for schizophrenia, including studies comparing treatment with more than one antipsychotic with treatment with only one antipsychotic medication (Correll 2003). However, the efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological combination strategies, specifically relating to clozapine plus one other antipsychotic, in people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, needs to be assessed.

OBJECTIVES

To determine the clinical effects of various clozapine combination strategies with antipsychotics in people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia both in terms of efficacy and tolerability.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. We included trials described as ’double-blind’ if it was implied that the study was randomised. For example, if the demographic details of the participants in each group were similar. We excluded quasi-randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people of both sexes, aged 18 years or more, with a diagnosis of treatment-resistant schizophrenia or related disorders (e.g. schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder), however diagnosed. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia-like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994).

Types of interventions

Clozapine plus another antipsychotic drug

Clozapine plus a different other antipsychotic drug

Any dose and means of administration was acceptable.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We divided outcomes into short term (less than three months) medium term (3-12 months) and long term (over one year). The primary measure of efficacy was clinical improvement on psychotic symptoms, measured either as a dichotomous outcome (proportions of patients with treatment response as defined by each of the studies), or as a continuous outcome (reported either as endpoint score or change from baseline to endpoint).

-

1

Clinical response

-

1.1

No clinically significant response in global state (dichotomous outcome) - as defined by each of the studies

-

1.2

Average score/change in global state (continuous outcome)

-

1.3

No clinically significant response on positive symptoms (dichotomous outcome) - as defined by each of the studies

-

1.4

Average score/change in positive symptoms (continuous outcome)

-

1.5

No clinically significant response on negative symptoms (dichotomous outcome) - as defined by each of the studies

-

1.6

Average score/change in negative symptoms (continuous outcome)

-

1.7

Use of additional medication (other than anticholinergics) for psychiatric symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

-

1

Death: suicide or any causes

-

2

Leaving the study early (acceptability of treatment), as measured by completion of trial

-

3

Extrapyramidal adverse effects

-

3.1

Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs (i.e. anticholinergics)

-

3.2

Clinically significant extrapyramidal adverse effects - as defined by each of the studies

-

3.3

Average score/change in extrapyramidal adverse effects

-

4

Blood adverse affects

-

4.1

Blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis

-

5

Other adverse effects, general and specific

-

5.1

Hypersalivation

-

5.2

Weight gain

-

5.3

Other adverse effects

-

6

Service utilization outcomes

-

6.1

Hospital admission

-

6.2

Days in hospital

-

7

Economic outcomes.

-

8

Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers

-

8.1

Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction - as defined by each of the studies

-

8.2

Average score/change in quality of life/satisfaction

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2008) using the phrase:

[((clozapin* or clozaril* or leponex* or denzapin* or zaponex*) in title, abstract and index fields in REFERENCE) OR ((clozapin* or clozaril* or leponex* or denzapin* or zaponex*) in interventions field in STUDY]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Cochrane Schizophrenia Group module).

We used MEDLINE to carry out an update search for the present review (date of last search: November 2008). See Appendix 1 for search strategy used.

Searching other resources

1. Reference checking

We checked reference lists of all identified randomised controlled trials.

2. Hand searching

If we found any appropriate journals and conference proceedings relating to clozapine combination strategies for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, we manually searched these periodicals.

3. Personal communication

We attempted to contact the corresponding author of each included study for information regarding supplemental data and unpublished trials. We contacted a defined list of experts in the field and asked of their knowledge of other studies, published or unpublished, relevant to the review article.

4. Industry

We requested pharmaceutical companies marketing investigational products to provide relevant published and unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

[For definitions of terms used in this, and other sections, please refer to the Glossary]

Selection of studies

Material downloaded from electronic sources included details of author, institution or journal of publication. Two review authors, MB and AC, independently inspected all reports of identified studies. We resolved any disagreement by consensus; however, where doubt remained, we acquired the full article. MB and AC independently decided whether these then met the review criteria. No blinding to the names of authors, institutions and journal of publication took place. We resolved any further disagreements by consensus with a third member of the review team (CB) and if disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment.

Data extraction and management

1. Data extraction

MB and AC independently extracted data and resolved disagreement by discussion with CB. When this was not possible, MB, AC and CB sought further information from trial authors.

To facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables (such as days in hospital) that could be reported in different metrics (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

When insufficient data were provided to identify the original group size (prior to dropouts), we contacted the authors. Where possible, we converted continuous scores into dichotomous data.

2. Management

We extracted the data onto standard, simple forms. Where possible, data were entered into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the ’line of no effect’ indicates a ’favourable’ outcome for clozapine.

3. Scale-derived data

Many rating scales are available to measure outcomes in mental health trials (Marshall 2000). These scales vary in quality and many are poorly validated. It is generally accepted that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure) (Rust 1989). Before publication of an instrument, most scientific journals insist that its reliability and validity be demonstrated to the satisfaction of referees. As a minimum standard, data were excluded from unpublished rating scales. In addition, the rating scale should be either: (i) a self report; or (ii) completed by an independent rater or relative. Rating scale data that were provided by the treating physician were presented but marked with an ’*’ to indicate potential bias. More stringent standards for instruments may be set in future editions of this review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The latest version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. This instrument consists of six items. Two of the items assess the strength of the randomisation process in preventing selection bias in the assignment of participants to interventions: adequacy of sequence generation and allocation concealment. The third item (blinding) assesses the influence of performance bias on the study results. The fourth item assesses the likelihood of incomplete outcome data, which raises the possibility of bias in effect estimates. The fifth item assesses selective reporting, the tendency to preferentially report statistically significant outcomes. It requires a comparison of published data with trial protocols, when such are available. The final item refers to other sources of bias that are relevant in certain circumstances, for example, in relation to trial design (methodological issues such as those related to cross-over designs and early trial termination) or setting. Two review authors assessed independently trial quality in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). Where inadequate details of allocation concealment and other characteristics of trials were provided, the trial authors were contacted in order to obtain further information. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement, if necessary, of another member of the review group.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

When summation was appropriate with binary outcomes such as improved/not improved, we calculated the relative risk (RR) statistic with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random-effects model. In addition, as a measure of efficiency, we estimated the number needed to treat (NNT) or the number needed to harm (NNH) from the pooled totals. We calculated the NNT/NNH as the inverse of the risk difference.

2. Continuous data

2.1 Summary statistic

For continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% CI. Again, this analysis is based on the random-effects model as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. If standard deviations were not recorded, we asked authors to supply the data. In the absence of data from the authors we used the mean standard deviation from other studies (Furukawa 2006). Continuous data may be presented from different scales, rating the same outcome. In this event, we presented all data without summation and inspected the general direction of effect.

2.2 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non-parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew was presented if 2SD>(S-Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data is presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), it is difficult to tell whether data are non-normally distributed (skewed) or not. Skewed data were presented in the ’Other data’ tables rather than included in the analysis.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

For change data (endpoint minus baseline), the situation is even more problematic. In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if data are skewed, though this is likely. According to a previous published review of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group (Duggan 2005), we presented change data in order to summarise available information. In doing this, it was assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analyses could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Again, without individual patient data it is impossible to test this assumption. Where both change and endpoint data were available for the same outcome category, we presented only endpoint data. We acknowledge that by doing this, much of the published change data could have been excluded, but argue that endpoint data is more clinically relevant and that if change data were to be presented along with endpoint data, it would be given undeserved equal prominence. We contacted authors of studies that only reported change for endpoint figures.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ ’cluster randomisation’ (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a ’unit of analysis’ error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). When clustering was incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non-cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

2. Cross-over trials

A major concern of cross-over trials is the carry-over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash-out phase. For the same reason cross-over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data of the first phase of cross-over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms were presented in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, these data were not reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss to follow up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). Since there is no evidence as to the degree of attrition which makes a reasonable analysis of the data possible, we included all trials in the main analysis. If, for a given outcome, more than 50% of the total numbers randomised were not accounted for we did not present results as such data will be impossible to interpret with authority. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost but the total loss was less than 50%, data was marked with ’*’ to indicate the result may be prone to bias.

2. Missing data

When data were missing and the method of ’last observation carried forward’ (LOCF) had been used to do an ITT analysis, then we used the LOCF data with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced. For studies that did not specify the reasons for people leaving the study early (dropouts), we assumed that these people had no change in clinical outcome variables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

We then visually inspected the graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I-squared statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by the I-squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I-squared estimate was greater than or equal to 50%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of significant heterogeneity (Higgins 2005). If inconsistency was high, data were not summated, but presented separately.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. We entered data from all identified and selected trials into a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We employed a random-effects model for analyses throughout. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random-effects models. The random-effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us and as a result significant between trial heterogeneity is implemented in the pooled estimate the random-effects model is usually more conservative in terms of statistical significance. The disadvantage of the random-effects model is that it puts added weight onto the smaller of the studies - those trials that are most vulnerable to bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analysis

No subgroup analysis was planned.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If data are clearly heterogeneous we checked that data are correctly extracted and entered and that we had made no unit of analysis errors. If the high levels of heterogeneity remained we did not undertake a meta-analysis at this point for if there is considerable variation in results, and particularly if there is inconsistency in the direction of effect, it may be misleading to quote an average value for the intervention effect. We would have wanted to explore heterogeneity. We pre-specify no characteristics of studies that may be associated with heterogeneity except quality of trial method. If no clear association could be shown by sorting studies by quality of methods a random-effects meta-analysis was performed. Should another characteristic of the studies be highlighted by the investigation of heterogeneity, perhaps some clinical heterogeneity not hitherto predicted but plausible causes of heterogeneity, these post-hoc reasons will be discussed and the data analysed and presented. However, should the heterogeneity be substantially unaffected by use of random-effects meta-analysis and no other reasons for the heterogeneity be clear, the final data were presented without a meta-analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analysis was planned.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

For substantive descriptions of studies please see the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

The search (original: August 2006; update: March 2008) yielded 1331 references of potentially eligible studies. The MEDLINE update of search (November 2008) found 462 additional references. After checking titles and abstracts, 24 full text papers were obtained for a second assessment. After exclusion of papers not meeting inclusion criteria (because of mainly non-randomised design, wrong investigational compounds or wrong population), three randomised controlled trials were included in the present review (Genc 2007; Kong 2001; Zink 2008). We identified another potentially eligible study (NCT 00395915). This was an ongoing randomised controlled trial comparing clozapine plus aripiprazole versus clozapine plus haloperidol. Our requests to pharmaceutical companies marketing investigational products to provide relevant published and unpublished data yielded no further studies.

Included studies

Details of the characteristics of the three studies (Genc 2007; Kong 2001; Zink 2008) are given in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1. Length of studies

All studies were short-term studies. Genc 2007 and Kong 2001 conducted an eight week randomised controlled study and Zink 2008 conducted a similar six week study on clozapine augmentation with a second antipsychotic in patients partially responsive to clozapine.

2. Participants

The study participants in both groups had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Genc 2007 and Zink 2008 used DSM-IV to provide diagnostic criteria. Kong 2001 used Chinese criteria (CCMD-2-R). None of the studies presented data on co-morbidities. Genc 2007 and Zink 2008 included both inpatients and outpatients; Kong 2001, only inpatients. None of the studies mentioned other medications being prescribed to the participants prior to randomisation. The inclusion criteria were clearly reported in Genc 2007 and Zink 2008; by contrast, inclusion criteria were not detailed in Kong 2001.

In Zink 2008 treatment-resistant symptoms were reflected in a PANSS total score of ≥65. In Genc 2007 partial response was defined as persistent psychotic symptoms as evidenced by a total score >45 on the BPRS or a rating of moderately ill (>four) on at least two of the four BPRS positive symptoms items (hallucinatory behaviour, conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness). In Kong 2001 no definition of partial response was given.

Exclusion criteria were listed in two out of three papers (Genc 2007; Zink 2008) and included substance abuse (except for nicotine), organic mental disorders, epilepsy, mental retardation, haematological disorders, hypersensitivity reactions or intolerability to intervention agents and pregnancy. Kong 2001 did not report exclusion criteria.

In Zink 2008 the mean number of hospital admissions prior to randomisation was 5.5 (SD 3.6) in the clozapine plus risperidone group and 7 (SD 4.5) in the clozapine plus ziprasidone group.

3. Study size

The number of participants were 56 (Genc 2007), 60 (Kong 2001) and 24 (Zink 2008).

4. Interventions

Genc 2007 randomised 56 treatment-resistant patients who were partially responsive to clozapine to combination with either amisulpride (28 patients were randomised, but baseline characteristics were reported only for 27 participants randomised to clozapine plus amisulpride: 12 males and 15 females; mean age 37.29 (standard deviation [SD] 8.17)) or quetiapine (28 patients were randomised, but baseline characteristics were reported for only 23 participants randomised to clozapine plus quetiapine: 9 males and 14 females; mean age 37.30 (SD 8.18)). Kong 2001 randomised 60 participants with chronic schizophrenia who were partially responsive to clozapine in combination with either risperidone (n=30, all participants aged less than 42 years) or sulpiride (n=30, all participants aged less than 42 years). In Zink 2008 patients with partial response to clozapine were randomly attributed to combination with ziprasidone (n=12, 7 males and 5 females; mean age 37.25 (SD 9.9)) or risperidone (n=12, 7 males and 5 females; mean age 31.83 (SD 13.5)).

5. Dosing

In Genc 2007, to be included in the eight week follow-up study, patients had to have remained on a stable dose of clozapine for at least four weeks. Partial response was defined as persistent psychotic symptoms after at least a twelve week trial of 400 to 600 mg/day of clozapine. No figures were reported about clozapine dosages, however baseline doses of clozapine remained stable throughout the study. The final maximum doses were 900 mg/day for quetiapine and 600 mg/day for amisulpride at the end of the second week. Patients judged to be unable to tolerate the dose escalation schedule because of adverse effects were maintained at their maximum tolerated dose for the remainder of the study. Kong 2001 reported scant details about clozapine dosages, however the maximum clozapine dose was 400 mg/day in the risperidone group and 500 mg/day in the sulpiride one. Risperidone was started at 4 mg/day and the final dose was 6 mg/day; sulpiride was started at 800 mg/day and the final dose was 1200 mg/day. In Zink 2008, incomplete efficacy of clozapine monotherapy was assumed after a compliant treatment with ≥300 mg of clozapine per day over a period of ≥three months with serum levels of ≥200 μg/L or severe dose-limiting side effects of clozapine after shorter application or in lower doses (the serum concentration of 200 μg/L was considered as necessary for effective relapse prevention). During the trial, reductions of clozapine by 50 mg per week were allowed. Risperidone and ziprasidone were applied in an open manner; they were titrated starting with doses of 1 mg (risperidone) and 20 mg (ziprasidone). The final doses followed clinical requirements. Mean dose of clozapine at endpoint was 370.8 ± 150 mg/day (mean serum levels of 348 ± 222 μg/L) in the ziprasidone group and 437.5 ± 140 mg/day (mean serum levels of 302 ± 213 μg/L) in the risperidone group.

6. Dropout rate

In Zink 2008 two patients dropped out during the trial: one male patient experienced a significant akathisia after two weeks of augmentation under 2 mg risperidone and 275 mg clozapine; one female patient withdrew consent because of the subjective feelings of agitation after exposure to the first 20 mg of ziprasidone. These patients were excluded from further assessments. Sometimes trial authors may exclude some randomised individuals, causing imbalance in participant characteristics in the different intervention groups. In Kong 2001 no patients withdrew from the study (there were no dropouts) and the baseline characteristics of patients in the two groups (duration of illness, mean score on PANSS) were very similar. Considering that this study recruited only 30 patients per arm, it is difficult to explain this scenario by means of a proper randomisation (or by chance alone). In Genc 2007 six patients (five from the clozapine+ quetiapine group and one from the clozapine+amisulpride group) discontinued the study within the first two weeks and were excluded both from analysis and from reporting of baseline characteristics. Starting from 56 people randomised, a total of 50 patients (23 from the clozapine+quetiapine group and 27 from the clozapine+amisulpride group) who were able to complete the eight week follow up were assessed for statistical analysis. Unfortunately, baseline characteristics were reported only on fifty patients instead of fifty-six (see table in the published report of the paper).

7. Outcome scales

Details of scales that authors looked at are shown below.

7.1 Global state scales

7.1.1 Clinical Global Impression Scale - CGI Scale (Guy 1976)

This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven-point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement.

7.2 Mental state scales

7.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale - BPRS (Overall 1962)

This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18-item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven-point scale varying from ’not present’ to ’extremely severe’, scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from 0-126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

7.2.2 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale - PANSS (Kay 1986)

This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven-point scoring system varying from one - absent to seven - extreme. It can be divided into three sub-scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS-P), and negative symptoms (PANSS-N). A low score indicates lesser severity.

7.2.3 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression - HAM (Hamilton 1960)

This instrument is designed to be used only on people already diagnosed as suffering from an affective disorder of depressive type. It is used for quantifying the results of an interview, and its value depends entirely on the skill of the interviewer in eliciting the necessary information. The scale contains 17 variables measured on either a five or a three-point rating scale, the latter being used where quantification of the variable is either difficult or impossible. Among the variables are: depressed mood, suicide, work and loss of interest, retardation, agitation, gastro-intestinal symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, loss of insight, and loss of weight. It is useful to have two raters independently scoring the person at the same interview. The scores of the person are obtained by summing the scores of the two physicians. High scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms.

7.2.4 Global Assessment of Functioning - GAF (APA 2004)

A rating scale for a patients overall capacity of psychosocial functioning scoring from 1-100. Higher scores indicate a higher level of functioning.

7.3 Adverse effects scales

7.3.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale - AIMS (Guy 1976)

This has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long-term, drug-induced movement disorder and short-term movement disorders such as tremor.

7.3.2 Barnes Akathisia Scale - BAS (Barnes 1989)

The scale comprises items rating the observable, restless movements that characterise akathisia, a subjective awareness of restlessness, and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from zero - normal to three - severe. In addition, there is an item for rating global severity (from zero - absent to five - severe). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia.

7.3.3 Simpson Angus Scale - SAS (Simpson 1970)

This ten-item scale, with a scoring system of zero to four for each item, measures drug-induced parkinsonism, a short-term drug-induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

7.3.4 Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale - ESRS (Chouinard 1980)

This consists of a questionnaire relating to parkinsonian symptoms (nine items), a physician’s examination for parkinsonism and dyskinetic movements (eight items), and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. High scores indicate severe levels of movement disorder.

Excluded studies

After checking titles and abstracts of 1331 retrieved references, 24 full text papers were obtained for a second assessment. Twenty-one studies were then excluded because they did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details).

Risk of bias in included studies

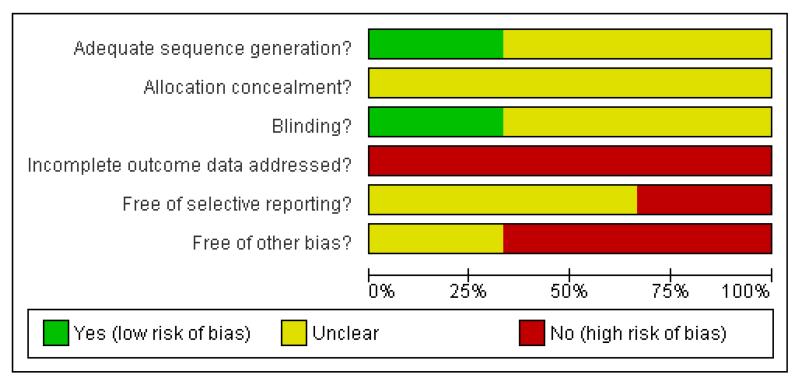

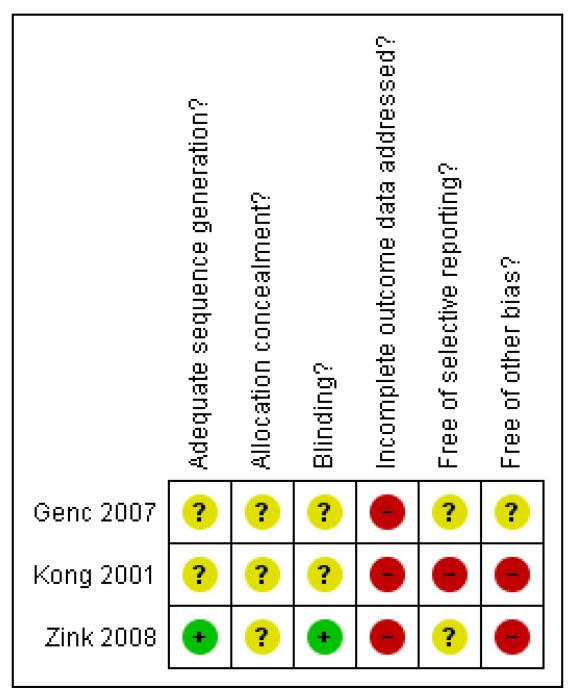

Considering the scant information reported in the studies included in the present review, a potentially high risk of bias should be taken into account when interpreting results (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

In Kong 2001 and in Genc 2007 it was reported that the studies were randomised trials, but no other information was given on how the randomisation and the allocation concealment were done. In Zink 2008 authors reported that the randomisation was performed by a biometrician who was not involved in any treatment decision, using a random number generator. However, this study did not report any information about concealment of allocation.

Blinding

No details were reported on blinding in Kong 2001. Zink 2008 was a non-blind study: risperidone and ziprasidone were applied in an open manner. Even though not clearly reported in the paper, it seems that Genc 2007 was an open study, where only the rater remained blinded to the medication throughout the study (patients and providers were probably aware of the allocated treatment).

Incomplete outcome data

In Zink 2008 and in Genc 2007 outcome data were reported only in graphs without standard deviations. This made it impossible to extract reliable information to assess any estimate of effect and the statistics between the two comparison groups.

Selective reporting

Only the study protocol for Zink 2008 is available. Not all of the pre-specified outcomes have been reported in the pre-specified way.

Effects of interventions

Studies included in the present review reported data about effects of interventions both in terms of efficacy and tolerability. The methodological quality of included studies was overall very low. In this systematic review we reported results from each study, however we opted for not pooling studies because of the high risk of substantial bias.

1. COMPARISON 1. CLOZAPINE PLUS RISPERIDONE versus CLOZAPINE PLUS SULPIRIDE (Kong 2001)

1.1 Death, by suicide or any causes

No deaths were reported.

1.2 Leaving the study early (acceptability of treatment), as measured by completion of trial

No information provided about drop-out rate.

1.3 Clinical response

1.3.1 Clinical response in global state (dichotomous outcome)

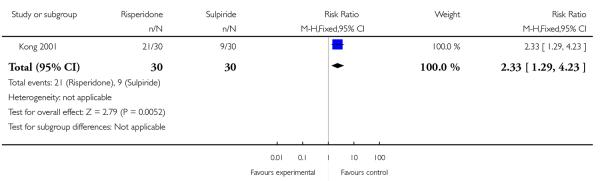

The response rate (defined as ’important results’) was higher in the risperidone group than in the sulpiride group (n=60, 1 RCT, RR 2.33 CI 1.29 to 4.23, p=0.005) (Analysis 1.1).

1.3.2 Average score/change in global state (continuous outcome)

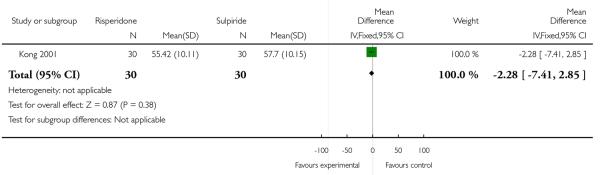

At the endpoint, the mean Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) total score was 55.42 (SD 10.11) in the risperidone group and 57.70 (SD 10.15) in the sulpiride one (n=60, 1 RCT, MD −2.28 CI −7.41 to 2.85, p=0.38) (Analysis 1.2).

1.3.3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data available.

1.3.4 Average score/change in positive symptoms (continuous outcome)

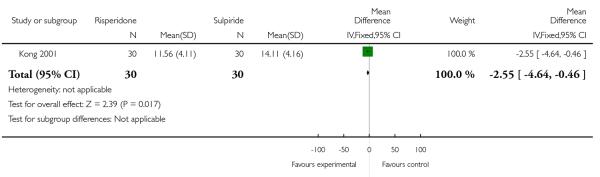

At the endpoint, the mean PANSS positive score was 11.56 (SD 4.11) in the risperidone group and 14.11 (SD 4.16) in the sulpiride one (n=60, 1 RCT, MD −2.55 CI −4.64 to −0.46, p=0.02) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3.5 Clinical response on negative symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data available.

1.3.6 Average score/change in negative symptoms (continuous outcome)

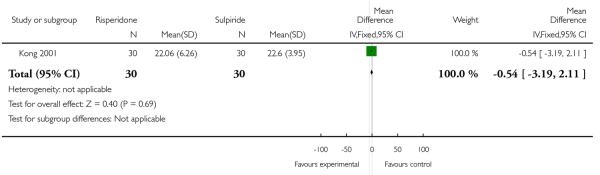

At the endpoint, the mean PANSS negative score was 22.06 (SD 6.26) in the risperidone group and 22.60 (SD 3.95) in the sulpiride one (n=60, 1 RCT, MD −0.54, CI −3.19 to 2.11, p=0.69) (Analysis 1.4).

1.3.7 Use of additional medication (other than anticholinergics) for psychiatric symptoms

No data reported.

1.4 Extrapyramidal adverse effects

1.4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs (i.e. anticholinergics)

No reliable information provided.

1.4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal adverse effects

No information provided.

1.4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal adverse effects

No information provided.

1.5 Blood adverse affects

1.5.1 Blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis

Three patients reported granulocytopenia in the sulpiride group, but the number in the risperidone group is unclear.

1.6 Other adverse effects, general and specific

1.6.1 Hypersalivation

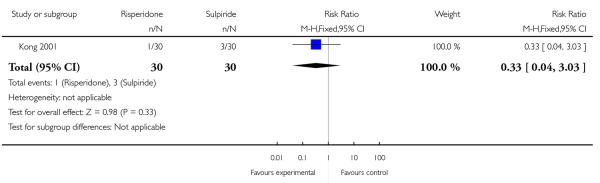

Hypersalivation was reported by one patient in the risperidone group and three patients in the sulpiride group (n=60, 1 RCT, RR 0.33 CI 0.04 to 3.03, p=0.33) (Analysis 1.5).

1.6.2 Weight gain

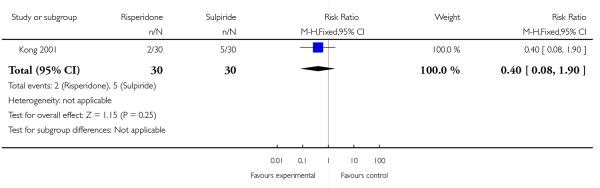

Weight gain was reported by two patients in the risperidone group and five patients in the sulpiride group (n=60, 1 RCT, RR 0.40, CI 0.08 to 1.90, p=0.25) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6.3 Other adverse effects

In risperidone group, four patients reported agitation, four patients akathisia and two rigidity; in the sulpiride group, five patients reported tachycardia and six blood pressure variations. The respective numbers in the other group are not clear.

1.7 Service utilization outcomes

No data available.

1.8 Economic outcomes

No data available.

1.9 Quality of life/satisfaction

No data available.

2. COMPARISON 2. CLOZAPINE PLUS RISPERIDONE versus CLOZAPINE PLUS ZIPRASIDONE (Zink 2008)

2.1 Death, by suicide or any causes

No deaths were reported.

2.2 Leaving the study early (acceptability of treatment), as measured by completion of trial

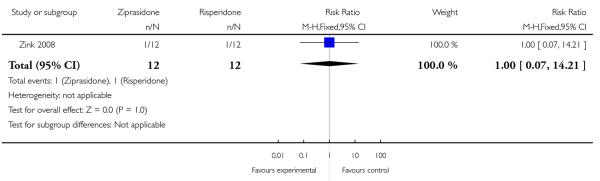

Two patients dropped out during the trial. One patient (male) in the risperidone group experienced a significant akathisia after two weeks of augmentation under 2 mg risperidone and 275 mg clozapine; one patient (female) withdrew consent because of the subjective feelings of agitation after exposure to the first 20 mg of ziprasidone (n=24, 1 RCT, RR 1.00 CI 0.07 to 14.21, p=1.00) (Analysis 2.1). These patients were excluded from further assessments.

2.3 Clinical response

2.3.1 Clinical response in global state (dichotomous outcome)

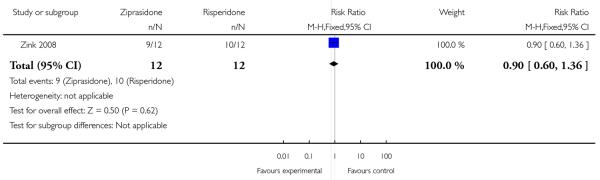

By the end of the trial (six weeks), a treatment response (20% reduction on the PANSS) was achieved by nine out of twelve patients randomised in the ziprasidone group compared with ten out of twelve patients allocated to risperidone (n=24, 1 RCT, RR 0.90 CI 0.60 to 1.36, p=0.62) (Analysis 2.2).

2.3.2 Average score/change in global state (continuous outcome) No reliable information reported (only p values).

2.3.3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data reported.

2.3.4 Average score/change in positive symptoms (continuous outcome)

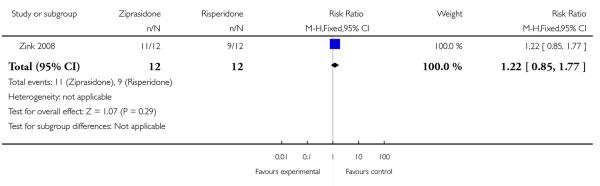

The PANSS positive subscore decreased by 20% in eleven patients randomised to ziprasidone and in nine patients randomised to risperidone (n=24, 1 RCT, RR 1.22 CI 0.85 to 1.77, p=0.29) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3.5 Clinical response on negative symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data reported.

2.3.6 Average score/change in negative symptoms (continuous outcome)

No reliable information reported (only p values).

2.3.7 Use of additional medication (other than anticholinergics) for psychiatric symptoms

At baseline additional medication was prescribed to several patients, such as valproic acid to two patients in the ziprasidone group and one patient in the risperidone group. Similarly, antidepressants such as doxepine (one patient in the risperidone group), reboxetine (two patients in the risperidone group) and benzodiazepine (clonazepam - two in each group) were recorded.

2.4 Extrapyramidal adverse effects

2.4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs (i.e. anticholinergics)

No data reported.

2.4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal adverse effects

No clear data reported.

2.4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal adverse effects

Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured using the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS). Authors reported in the paper that both treatment groups had mean initial EPS scores below three, indicating low severity of extrapyramidal movement disorders at baseline. By the end of the study, the ziprasidone group experienced an improvement from 2.4 to 1.1 (P = 0.013), whereas EPS scores in the risperidone group did not significantly change (P = 0.184). However, no standard deviations and no clear figure for the risperidone group were reported in the paper, so it was not possible for reviewers to assess statistical significance.

2.5 Blood adverse affects

2.5.1 Blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis

No data reported.

2.6 Other adverse effects, general and specific

2.6.1 Hypersalivation

No data reported.

2.6.2 Weight gain

No reliable data reported. The only information available is that patients in both groups gained body weight (+1.50 kg in the ziprasidone group and +1.55 kg in the risperidone group).

2.6.3 Other adverse effects

Patients randomised to ziprasidone experienced a significant increase of QTc interval (from 387.7 to 403.2 ms, P = 0.043); on the contrary, patients allocated to risperidone showed an non-significant decrease of QTc interval (from 390.5 to 381.4 ms). The maximal value assessed in the ziprasidone group and in the risperidone group was 423.5 and 417.7 ms, respectively.

2.7 Service utilization outcomes

No data reported.

2.8 Economic outcomes

No data reported.

2.9 Quality of life/satisfaction

No data reported.

3. COMPARISON 3. CLOZAPINE PLUS AMISULPRIDE versus CLOZAPINE PLUS QUETIAPINE (Genc 2007)

3.1 Death, by suicide or any causes

No deaths were reported.

3.2 Leaving the study early (acceptability of treatment), as measured by completion of trial

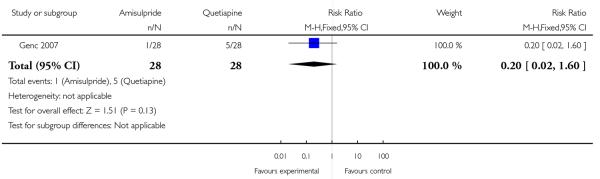

Six patients (five from the quetiapine group and one from the amisulpride group) discontinued the study within the first two weeks after randomisation (n=56, 1 RCT, RR 0.20 CI 0.02 to 1.60, p=0.13) (Analysis 3.1). Reasons for discontinuation in the quetiapine group were exacerbation of psychotic symptoms (four patients) or lack of efficacy (one patient). One patient in the amisulpride group left the study early after two weeks.

3.3 Clinical response

3.3.1 Clinical response in global state (dichotomous outcome)

No information provided.

3.3.2 Average score/change in global state (continuous outcome)

No reliable information reported (only p values).

3.3.3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data available.

3.3.4 Average score/change in positive symptoms (continuous outcome)

No reliable information reported (only p values).

3.3.5 Clinical response on negative symptoms (dichotomous outcome)

No data available.

3.3.6 Average score/change in negative symptoms (continuous outcome)

No reliable information reported (only p values).

3.3.7 Use of additional medication (other than anticholinergics) for psychiatric symptoms

No data reported.

3.4 Extrapyramidal adverse effects

3.4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs (i.e. anticholinergics)

No data reported.

3.4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal adverse effects

No data reported.

3.4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal adverse effects

No reliable information reported (only p values).

3.5 Blood adverse affects

3.5.1 Blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis

No data reported.

3.6 Other adverse effects, general and specific

3.6.1 Hypersalivation

No data reported.

3.6.2 Weight gain

No data reported.

3.6.3 Other adverse effects

Four patients in the quetiapine group reported an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and left the study early.

3.7 Service utilization outcomes

No data reported.

3.8 Economic outcomes

No data reported.

3.9 Quality of life/satisfaction

No data reported.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

The extent to which a Cochrane review can draw conclusions about the effects of an intervention depends on whether the data and results from the included studies are valid. In particular, invalid studies may produce a misleading result (Higgins 2008). We found only three randomised controlled studies, comparing different compounds as treatment combination strategies to clozapine. This systematic review did not find any data from randomised controlled trials of sufficient methodological rigour or reported with sufficient quality to assess the clinical effects of various clozapine combination strategies with antipsychotics in people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All studies had small sample size (30 patients per arm at most). The lower the sample, the higher the risk of imbalance between treatment comparison groups. A baseline imbalance in factors that were strongly related to outcome measures might have caused bias in the intervention effect estimate. This can happen through chance alone when only few patients are randomised, but imbalance may also arise through incorrect (unconcealed) allocation of interventions (Schulz 1995). Furthermore, the study method and data were reported with insufficient clarity to allow extraction of reliable information. Thus, it was not possible to carry out a formal meta-analysis to increase the statistical power and to give readers a summary statistics of the available evidence.

Quality of the evidence

The trials were small, included participants with no unique definition of partial responsiveness and provided no information about core issues to assess study quality (such as randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding and completeness of outcome data).

Potential biases in the review process

In this review we considered the risk of bias of the included studies too high. Bias due to a particular design flaw (e.g. lack of allocation concealment) may lead to underestimation of an effect in one study but overestimation in another study. It is usually impossible to know to what extent biases have affected the results of a particular study, although there is good empirical evidence that particular flaws in the design, conduct and analysis of randomised clinical trials lead to bias (Schulz 1995). We are aware of the risk of not reporting information that might be of interest for clinicians. However, being consistent with our study protocol, we preferred to focus on the limitations in the trials that have been done so far, to highlight the needs for new randomised controlled trials that will be carried out in the field of combination strategies in patients who are partially or not responsive to clozapine.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review are consistent with those of Correll 2008, who pointed out the methodological shortcomings of existing trials. Barbui 2009 carried out a systematic review to determine the efficacy of various clozapine combination strategies with antipsychotics, including only studies randomly allocating patients to clozapine plus another antipsychotic versus clozapine monotherapy. From a clinical viewpoint, the main message was that a second antipsychotic in addition to clozapine had modest to absent benefit. The small number of patients included in each trial and the employment of an open design in many studies made conclusions very difficult, and comparisons between individual drugs were hardly feasible.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

1. For people with schizophrenia

Although clinical guidelines recommend a second antipsychotic in addition to clozapine in partially responsive patients with schizophrenia (NICE 2002), people with clozapine-resistant schizophrenia should consider that no particular combination strategy has been shown to be superior to the others.

2. For clinicians

Due to the poor quality of the retrieved information (small sample size, heterogeneity of comparisons, flaws in the design, conduct and analysis), the present systematic review was not able to show if any particular combination strategy was more effective than the others in treating patients with clozapine-resistant schizophrenia.

3. For policy makers/managers

The available data are too limited to allow any recommendations for policy makers.

Implications for research

Considering that comparative evidence has been published suggesting potential advantages of combination treatment with clozapine plus one antipsychotic in terms of efficacy and tolerability (Mule 2008), new randomised controlled trials independent from pharmaceutical industry need to recruit many more patients to give a reliable estimate of effect or of no effect of antipsychotics as combination treatment with clozapine in patients who do not have an optimal response to clozapine monotherapy.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness affecting one per cent of the population throughout the world. The symptoms of schizophrenia are perceptions without cause (hallucinations), fixed false beliefs (delusions) and/or apathy, slowing and less movement or thought. In most Western countries people who do not respond to the majority of common antipsychotics (called treatment resistant people) are tried on the atypical antipsychotic clozapine. If they do not respond to clozapine alone, then another antipsychotic is usually added. This review looks at clinical trials which compare the response to a second antipsychotic in people who are treatment resistant, and on clozapine.

Although 24 studies were looked at, only three fulfilled the criteria to be included, the total number of people randomised was 140. The studies were all less than 8 weeks long, and all compared different second antipsychotics (amisulpiride versus quetiapine, risperidone versus sulpiride and risperidone versus ziprasidone).

When people on clozapine plus risperidone were compared to those on clozapine plus sulpiride, more people taking risperidone showed an improvement generally. However, when specific symptoms of schizophrenia were studied, there was change for the better in all groups but no second antipsychotic was significantly better than the one it was compared to. When looking at adverse effects, people taking sulpiride were slightly more likely to suffer from hypersalivation and weight gain than those taking risperidone.

These three trials contained small numbers of people and the data were not well recorded. Although there is a suggestion that adding a second antipsychotic may improve general functioning and decrease the symptoms of schizophrenia, it is still not possible to say which antipsychotic would help the most. A large, longer and independent trial should be done on people who have not responded completely to clozapine to find the most effective treatment.

(Plain language summary prepared for this review by Janey Antoniou of RETHINK, UK www.rethink.org)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the editorial base of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for their help. We thank Lucia Muzio and Alessandra Signoretti for translating and extracting data from the Chinese literature and the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for providing editorial assistance. We are grateful to the Fondazione Cariverona for providing a three-year Grant to the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health and Service Organization at the University of Verona, directed by Professor Michele Tansella.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Department of Medicine and Public Health, Section of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, University of Verona, Italy.

Department of Applied Health and Behavioral Sciences, Section of Psychiatry, University of Pavia, Italy.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Allocation: insufficient information (possibly randomised). Blindness: single blind Duration: eight weeks Design: multicentre (wash out period not specified). |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM-IV). History: informed consent obtained. N=56 Age: not reported. Sex: not clearly reported. Setting: Inpatients and outpatients. Inclusion criteria: partial response after least 12 weeks of 400-600 mg of clozapine. Exclusion criteria: substance abuse, organic mental disorder, epilepsy, mental retardation and severe physical illness |

|

| Interventions | 1. Clozapine plus amisulpride: clozapine mean dose 536.95 mg/day (SD 127.09 mg) and amisulpride mean dose 437.03 mg/day (SD 104.32 mg). N=28. 2. Clozapine plus quetiapine: clozapine mean dose 550 mg/day (SD 125.42 mg) and quetiapine mean dose 595.65 mg/day (SD 125.21 mg). N=28 |

|

| Outcomes | Primary and secondary outcomes are not clearly specified in the text | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Quote: “patients were randomly assigned…”. Insufficient information about the sequence generation process |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Quote: “Patients were studied by the second author for random assignment”, “patients were randomly assigned by the second author…”. “Drug follow-up was performed by the second author” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | “The first author, who was the rater remained blind to the medication throughout the study”. No information on blindness of participants is given. The second author was not blind |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | Within the first two weeks, five patients (out of 28) discontinued from quetiapine combination treatment (four due to “exacerbation of psychotic symptoms”, one due to “lack of efficacy”), and one patient (out of 28) from amisulpride combination treatment Baseline characteristics and analyses performed on 23 and 27 patients, respectively |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | No information available |

| Methods | Allocation: insufficient information. Blindness: insufficient information. Duration: eight weeks Design: multicentre (wash out period not specified). |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (Chinese criteria: CCMD-2-R). History: informed consent obtained. N=60 Age: < 42 years. Sex: not clearly reported. Setting: Inpatients. Inclusion criteria: clozapine-resistant patients (dose and length of treatment were not clearly specified in the text). Exclusion criteria: severe organic disease and substance abuse |

|

| Interventions | 1. Clozapine plus risperidone: N=30. 2. Clozapine plus sulpiride: N=30. |

|

| Outcomes | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores (both as dichotomous and continuous outcome) | |

| Notes | It is unclear whether patients with schizoaffective disorder were enrolled. No dropouts at all were reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | No data. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | No data. |

| Free of other bias? | No | Potential for selection bias, because baseline characteristics of the two groups are too similar |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: open label. Duration: six weeks (before baseline evaluation including assessment of clozapine serum level, the patients had to be on a completely stable antipsychotic monotherapy of clozapine for at least one week). Design: multicentre (large urban population in Germany). |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV). History: informed consent obtained. N=28.* Age: between 18 and 70 years. Sex: about 60% of patients were males in both groups (7 out of 12). Setting: inpatients and outpatients. Inclusion criteria: Treatment-resistant symptoms of psychosis under clozapine monotherapy with clinical significance. Incomplete efficacy of clozapine monotherapy was assumed after a compliant treatment with ≥300 mg of clozapine per day over a period of ≥three months with serum levels of ≥200 μg/L or severe dose-limiting side effects of clozapine after shorter application or in lower doses. Treatment resistant symptoms were reflected in a PANSS total score of ≥65. Exclusion criteria: intolerability to risperidone or ziprasidone and substance abuse except for nicotine |

|

| Interventions | 1. Clozapine plus risperidone: clozapine mean dose 406.8 mg/day (SD not provided) and risperidone mean dose 3.82 mg/day (SD 1.8 mg). N=12. 2. Clozapine plus ziprasidone: clozapine mean dose 361.4 mg/day (SD not provided) and ziprasidone mean dose 134 mg/day (SD 34.4 mg). N=12 During the trial, risperidone and ziprasidone were applied in an open manner; they were titrated starting with doses of 1 mg (risperidone) and 20 mg (ziprasidone). The final doses followed clinical requirements. Reductions of clozapine by 50 mg per week were allowed |

|

| Outcomes | Primary and secondary outcome are not clearly specified. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (ESRS) Hillside Akathisia Scale Body weight, heart rate and blood pressure, electrocardiograms (ECG) at inclusion and after two, four and six weeks of augmentation treatment. Clozapine side effects such as sialorrhoea, sedation and weight gain were evaluated on a visual analogous scale between one (no side-effects) and ten (severe burden of the patient). A full-test panel for clinical chemistry and haematological studies were obtained before randomisation, after three and six weeks of treatment. In addition, serum levels of clozapine and prolactin were determined at inclusion and after six weeks Authors were unable to use the following outcomes (with reason): SANS (no mean endpoint scores); HAMD (no mean endpoint scores); CGI (no standard deviations); GAF (no standard deviations); ESRS (no mean endpoint scores); Hillside Akathisia Scale (no mean endpoint scores); all remaining safety parameters (neither endpoint values nor standard deviations) |

|

| Notes | The study sample had significantly different periods of treatment (the patients suffered from severe psychotic symptoms for on average 13.8 years in the ziprasidone group and 9.3 years in the risperidone group) and higher serum concentrations of clozapine at baseline (370.8 ± 150 mg/die in the ziprasidone group and 437.5 ± 140 mg/die in the risperidone group) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Randomisation was performed using a random number generator. Random number generator (SAS) used by an external biometrician not involved in any treatment decision |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Providers and assessors were not blind to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | Two patients dropped out from allocated treatment: one patient (male) experienced akathisia after two weeks of risperidone and another patient (female) experienced agitation after exposure to the first administration of ziprasidone. They were excluded from further assessment |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | The study protocol is available but not all of the study’s pre-specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre-specified way |

| Free of other bias? | No | A baseline imbalance in patients’ characteristics (for instance, dosages and blood levels of clozapine and investigational drugs) might have caused bias in the intervention effect estimate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bao 1988 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Cao 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no combination treatment |

| Cooper 2005 | Allocation: non-randomised (population-based study) |

| Gerlach 1978 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no combination treatment |

| Glick 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no combination treatment |

| Goff 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Honer 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: placebo-controlled trial - no active comparison with combination treatment |

| Josiassen 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: placebo-controlled trial - no active comparison with combination treatment |

| Pickar 1994 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Potkin 1999 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no active comparison with combination treatment |

| Qui 1990 | Allocation: non-randomised (review) |

| Shen 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Sihloh 1997 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: placebo-controlled trial - no active comparison with combination treatment |

| Small 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Stryjer 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Wang 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no combination treatment |

| Welbel 1980 | Allocation: non-randomised (review) |

| Yagcioglu 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: placebo-controlled trial - no active comparison with combination treatment |

| Yang 1994 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Zhu 1999 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people without treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Zhu 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Intervention: no active comparison with combination treatment |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Clozapine and Aripiprazole Versus Clozapine and Haloperidol in the Treatment of Schizophrenia |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Treatment-resistant schizophrenia (clinical diagnosis, guided by DSM-IV criteria) after at least six months at a stable dose of 400 mg or more per day, unless the size of the dose was limited by side-effects |

| Interventions | Clozapine plus aripiprazole versus clozapine plus haloperidol |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures: Withdrawal from allocated treatment within three months. Secondary Outcome Measures: Withdrawal from allocated treatment within 12 months of follow up. Time to withdrawal from allocated treatment. Severity of illness, measured at month 3 and 12. Withdrawal from study treatment, due to adverse reactions, within 3 and 12 months. Concurrent use of adjunctive medication within 3 and 12 months. Concurrent use of antiparkinson medication within 3 and 12 months. Adverse events within 3 and 12 months. Biological parameters, measured at month 3 and 12. Metabolic syndrome within 3 and 12 months. Subjective tolerability of antipsychotic drugs, measured at month 3 and 12. Deliberate self-harm within 3 and 12 months. |

| Starting date | September 2006 |

| Contact information | studio.chat@medicina.univr.it |

| Notes |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical response in global state (defined as “important results”) | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [1.29, 4.23] |

| 2 Average score/change in global state (PANSS total score) | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −2.28 [−7.41, 2.85] |

| 3 Average score/change in positive symptoms (PANSS positive score) | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −2.55 [−4.64, −0.46] |

| 4 Average score/change in negative symptoms (PANSS negative score) | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −0.54 [−3.19, 2.11] |

| 5 Adverse effects - Hypersalivation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.04, 3.03] |

| 6 Adverse effects - Weight gain | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.08, 1.90] |

Comparison 2. Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.21] |

| 2 Clinical response in global state (20% reduction on the PANSS) | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.60, 1.36] |

| 3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (PANSS positive subscore decreased by 20%) | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.85, 1.77] |

Comparison 3. Clozapine plus amisulpride vs clozapine plus quetiapine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.02, 1.60] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 1 Clinical response in global state (defined as “important results”).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 1 Clinical response in global state (defined as ”important results”)

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 2 Average score/change in global state (PANSS total score).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 2 Average score/change in global state (PANSS total score)

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 3 Average score/change in positive symptoms (PANSS positive score).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 3 Average score/change in positive symptoms (PANSS positive score)

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 4 Average score/change in negative symptoms (PANSS negative score).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 4 Average score/change in negative symptoms (PANSS negative score)

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 5 Adverse effects - Hypersalivation.

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 5 Adverse effects - Hypersalivation

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride, Outcome 6 Adverse effects - Weight gain.

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 1 Clozapine plus risperidone vs clozapine plus sulpiride

Outcome: 6 Adverse effects - Weight gain

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone

Outcome: 1 Leaving the study early

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone, Outcome 2 Clinical response in global state (20% reduction on the PANSS).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone

Outcome: 2 Clinical response in global state (20% reduction on the PANSS)

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone, Outcome 3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (PANSS positive subscore decreased by 20%).

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 2 Clozapine plus ziprasidone vs clozapine plus risperidone

Outcome: 3 Clinical response on positive symptoms (PANSS positive subscore decreased by 20%)

|

Analysis 3.1. Comparison 3 Clozapine plus amisulpride vs clozapine plus quetiapine, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

Review: Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia

Comparison: 3 Clozapine plus amisulpride vs clozapine plus quetiapine

Outcome: 1 Leaving the study early

|

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

| # | Searches | Results | Search Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | clozapine.mp. and Clozapine/ | 5550 | Advanced |

| 2 | Schizophrenia/ and schizophrenia.mp | 65799 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 2388 | Advanced |

| 4 | limit 3 to clinical trial, all | 462 | Advanced |

MEDLINE search carried out independently by review authors in November 2008.

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 11 March 2008.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 February 2010 | Amended | Plain Language Summary by consumer added |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007

Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 November 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

Andrea Cipriani: none known.

Marianna Bosso: none known.

Corrado Barbui: none known.

References to studies included in this review

- Genc 2007 {published data only} .Genç Y, Taner E, Candansayar S. Comparison of clozapine-amisulpride and clozapine-quetiapine combinations for patients with schizophrenia who are partially responsive to clozapine: a single-blind randomized study. Advances in Therapy. 2007;24(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02849987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong 2001 {published data only} .Kong QR. Sulpiride clozapine combined high and low doses observed in the treatment of schizophrenia. Shandong Archives of Psychiatry. 2001;14:138–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zink 2008 {published data only} .Zink M, Kuwilsky A, Krumm B, Dressing H. Efficacy and tolerability of ziprasidone versus risperidone as augmentation in patients partially responsive to clozapine: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2009;23:305–14. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Bao 1988 {published data only} .Bao XQ. A double-blind study on the effect of clozapine penfluridol and chlorpromazine in the treatment of schizophrenia. Chung Hua Shen Ching Ching Shen Ko Tsa Chih [Chinese Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry] 1988;21(5):274–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao 2003 {published data only} .Cao HJ, You HF, Fan FL, Zhang J. The control study of risperidone and clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Chinese Journal of Medicine Research. 2003;3(4):316–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper 2005 {published data only} .Cooper D, Moisan J, Gaudet M, Abdous B, Gregoire JP. Ambulatory use of olanzapine and risperidone: a population-based study on persistence and the use of concomitant therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50(14):901–8. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]