Abstract

Background

In many countries of the industrialised world second generation (atypical) antipsychotics have become first line drug treatments for people with schizophrenia. The question as to whether, and if so how much, the effects of the various second generation antipsychotics differ is a matter of debate. In this review we examine how the efficacy and tolerability of amisulpride differs from that of other second generation antipsychotics.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of amisulpride compared with other atypical antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (April 2007) which is based on regular searches of BIOSIS, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO.

We updated this search in July 2012 and added 47 new trials to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, at least single‐blind, trials comparing oral amisulpride with oral forms of aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone or zotepine in people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For continuous data we calculated weighted mean differences (MD), for dichotomous data we calculated relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis based on a random effects model. We calculated numbers needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) where appropriate.

Main results

The review currently includes ten short to medium term trials with 1549 participants on three comparisons: amisulpride versus olanzapine, risperidone and ziprasidone. The overall attrition rate was considerable (34.7%) with no significant difference between groups. Amisulpride was similarly effective as olanzapine and risperidone and more effective than ziprasidone (leaving the study early due to inefficacy: n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.21 CI 0.05 to 0.94, NNT 8 CI 5 to 50). Amisulpride induced less weight gain than risperidone (n=585, 3 RCTs, MD ‐0.99 CI ‐1.61 to ‐0.37) or olanzapine (n=671, 3 RCTs, MD ‐2.11 CI ‐2.94 to ‐1.29). Olanzapine was also associated with a higher increase of glucose (n=406, 2 RCTs, MD ‐7.30 CI ‐7.62 to ‐6.99). There was no difference in terms of cardiac effects and extra pyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared with olanzapine (akathisia: n= 587, 2 RCTs, RR 0.66 CI 0.36 to 1.21), compared with risperidone (akathisia: n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.80 CI 0.58 to 1.11) and compared with ziprasidone (akathisia: n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.63, CI 0.11 to 3.67).

Authors' conclusions

There is little randomised evidence comparing amisulpride with other second generation antipsychotic drugs. We could only find trials comparing amisulpride with olanzapine, risperidone and ziprasidone. We found amisulpride may be somewhat more effective than ziprasidone, and more tolerable in terms of weight gain and other associated problems than olanzapine and risperidone. These data, however, are based on only ten short to medium term studies and therefore too limited to allow for firm conclusions.

Note: the 47 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Keywords: Humans, Amisulpride, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepines/adverse effects, Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use, Olanzapine, Piperazines, Piperazines/adverse effects, Piperazines/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risperidone, Risperidone/adverse effects, Risperidone/therapeutic use, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/drug therapy, Sulpiride, Sulpiride/adverse effects, Sulpiride/analogs & derivatives, Sulpiride/therapeutic use, Thiazoles, Thiazoles/adverse effects, Thiazoles/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Amisulpride versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia

This review compared the effects of amisulpride with those of other so called second generation (atypical) antipsychotic drugs. For half of the possible comparisons not a single relevant study could be identified. Based on very limited data there was no difference in efficacy comparing amisulpride with olanzapine and risperidone, but a certain advantage compared with ziprasidone. Amisulpride was associated with less weight gain than risperidone and olanzapine.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is usually a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder which afflicts approximately one per cent of the population world‐wide, with little gender differences. The annual incidence of schizophrenia averages 15 per 100,000, the point prevalence averages approximately 4.5 per population of 1000, and the risk of developing the illness over one's lifetime averages 0.7% (Tandon 2008). Its typical manifestations are positive symptoms such as fixed, false beliefs (delusions) and perceptions without cause (hallucinations), negative symptoms such as apathy and lack of drive, disorganisation of behaviour and thought, and catatonic symptoms such as mannerisms and bizarre posturing (Carpenter 1994). The degree of suffering and disability is considerable with 80% ‐ 90% not working (Marvaha 2004) and up to 10% dying (Tsuang 1978). In the age group of 15‐44 years, schizophrenia is among the top ten leading causes of disease‐related disability in the world (WHO 2001).

Description of the intervention

Conventional antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol have traditionally been used as first line antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia (Kane 1993). In the 1990's the introduction of clozapine, a new antipsychotic that was found to be more effective and associated with fewer movement disorders than chlorpromazine (Kane 1988), boosted the development of a new/second generation of antipsychotics (NGA) also known as atypical antipsychotics. There is no absolute definition of what an "atypical" or "second generation" antipsychotic is. They were initially said to differ from typical antipsychotics in that they did not cause movement disorders (catalepsy) in rats at clinically effective doses (Arnt 1998). The terms "new" or "second generation" antipsychotics are not much better, because clozapine itself is now a very old drug. According to treatment guidelines (APA 2004, Gaebel 2006) second generation antipsychotics include drugs such as amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone sertindole, ziprasidone and zotepine, although it is unclear whether some old and cheap compounds such as sulpiride or perazine have similar properties (Möller 2000). The second generation antipsychotics raised major hopes of superior effects in a number of areas such as compliance, cognitive functioning, negative symptoms, movement disorders, quality of life, and treatment of people whose illness had been resistant to treatment.

How the intervention might work

Amisulpride, a substituted benzamide, has a selective and high affinity for dopamine (D3/D2) receptors and presents an interesting pharmacological profile. The profile is said to enable a dose‐dependent modulation of dopamine activity. Amisulpride increases dopaminergic transmission at low doses via presynaptic receptor blockade, preferentially in limbic structures, as opposed to the striatum (Freeman 1997, Rein 1997). It has no affinity for other receptor or transporter systems. This unusual property could theoretically make amisulpride different from other atypical antipsychotic drugs in its ability to treat positive and negative symptoms, and its side‐effect profile (Mota Neto 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

The debate as to how far NGA improve these outcomes compared with conventional antipsychotics continues (Duggan 2005, El‐Sayeh 2006) and the results from recent studies were sobering (Liebermann 2005, Jones 2006 a). Nevertheless, in some parts of the world, especially in the highly industrialised countries, second generation antipsychotics have become the mainstay of treatment. The second generation antipsychotics also differ in terms of their costs; while amisulpride and risperidone are already generic, aripiprazole and olanzapine for example are still not. Therefore the question as to whether they differ from each other in their clinical effects becomes increasingly important. In this review we aim to summarise evidence from randomised controlled trials comparing amisulpride with other second generation antipsychotics.

Objectives

To review the effects of amisulpride compared with other second generation antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials which were at least single‐blind (i.e. at least blind raters). Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind', but it was only implied that the study was randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we only used clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Randomised cross‐over studies will be eligible but only data up to the point of first cross‐over because of the instability of the problem behaviours and the likely carry‐over effects of all treatments.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and other types of schizophrenia‐like psychoses (e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994).

Types of interventions

1. Amisulpride: any oral form of application, any dose 2. Other "atypical" antipsychotic drugs: aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone, zotepine: any oral form of application, any dose.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into the short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13‐26 weeks) and long term (over 26 weeks).

Primary outcomes

1. No clinically important response as defined by the individual studies (e.g. global impression 'less than much improved' or 'less than 50% reduction on a rating scale')

Secondary outcomes

1. Leaving the studies early (any reason, adverse events, inefficacy of treatment)

2. Global state 2.1 No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies) 2.2 Relapse (as defined by the individual studies)

3. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 3.1 No clinically important change in general mental state score 3.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 3.3 Average change in general mental state score 3.4 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 3.5 Average endpoint specific symptom score 3.6 Average change in specific symptom score

4. General functioning 4.1 No clinically important change in general functioning 4.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 4.3 Average change in general functioning score

5. Quality of life/satisfaction with treatment 5.1 No clinically important change in general quality of life 5.2 Average endpoint general quality of life score 5.3 Average change in general quality of life score

6. Cognitive functioning 6.1 No clinically important change in overall cognitive functioning 6.2 Average endpoint of overall cognitive functioning score 6.3 Average change of overall cognitive functioning score

7. Service use 7.1 Number of participants hospitalised

8. Adverse effects 8.1 Number of participants with at least one adverse effect 8.2 Clinically important specific adverse effects (cardiac effects, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, seizures, sedation, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count) 8.3 Average endpoint in specific adverse effects 8.4 Average change in specific adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register was searched (April 2007) using the phrase: [((amisulprid* AND (aripiprazol* OR clozapin* OR olanzapin* OR quetiapin* OR risperidon* OR sertindol* OR ziprasidon* OR zotepin*)) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE) or ((amisulprid* AND (aripiprazol* OR clozapin* OR olanzapin* OR quetiapin* OR risperidon* OR sertindol* OR ziprasidon* OR zotepin*)) in interventions of STUDY)] This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module). The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register is maintained on Meerkat 1.5.1. This version of Meerkat stores references as studies. When an individual reference is selected through a search, all references which have been identified as the same study are also selected.

2. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (July 2012) using the phrase:

[((*amisulprid* AND (*aripiprazol* OR *clozapin* OR *olanzapin* OR *quetiapin* OR *risperidon* OR *sertindol* OR *ziprasidon* OR *zotepin*)) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE) or ((*amisulprid* AND (*aripiprazol* OR *clozapin* OR *olanzapin* OR *quetiapin* OR *risperidon* OR *sertindol* OR *ziprasidon* OR *zotepin*)) in interventions of STUDY)]

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to existing or new review titles.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching We inspected the references of all identified studies for more trials.

2. Personal contact We contacted the first author of each included study for missing information.

3. Drug companies We contacted the manufacturers of all atypical antipsychotics included for additional data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

KK and SL independently inspected all reports. We resolved any disagreement by discussion, and where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, we independently decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and these trials were added to the list of those awaiting assessment.

Data extraction and management

1. Data extraction KK and CRK independently extracted data from selected trials. When disputes arose we attempted to resolve these by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management KK and CRK extracted the data onto standard simple forms. Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for ziprasidone.

3. Rating scales A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental health studies. These instruments vary in quality and many are not validated, or are even ad hoc. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure) (Rust 1989). Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore continuous data from rating scales were included only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, authors KK and SL assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases.

The risk of bias in each domain and overall were assessed and categorised into:

A. Low risk of bias: plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results (categorised as 'Yes' in Risk of Bias table) B. High risk of bias: plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results (categorised as 'No' in Risk of Bias table) C. Unclear risk of bias: plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results (categorised as 'Unclear' in Risk of Bias table)

Trials with high risk of bias (defined as at least four out of seven domains were categorised as 'No') or where allocation was clearly not concealed, were not included in the review. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials are provided, authors of the studies were contacted in order to obtain further information. Non‐concurrence in quality assessment was reported.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Data types We assessed outcomes using continuous (for example changes on a behaviour scale), categorical (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as "little change", "moderate change" or "much change") or dichotomous (for example, either "no important changes or "important change" in a person's behaviour) measures. Currently RevMan does not support categorical data so we were unable to analyse this.

2. Dichotomous‐ yes/no‐ data We carried out an intention to treat analysis. Everyone allocated to the intervention were counted, whether they completed the follow up or not. It was assumed that those who left the study early had no change in their outcome. This rule is conservative concerning response to treatment, because it assumes that those discontinuing the studies would not have responded. It is not conservative concerning adverse effects, but we felt that assuming that all those leaving early would have developed side‐effects would overestimate risk. Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into "clinically improved" or "not clinically improved". It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a, Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

We calculated the relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the random effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number needed to harm (NNH) as the inverse of the risk difference.

3. Continuous data 3.1 Normal distribution of the data The meta‐analytic formulas applied by RevMan Analyses (the statistical programme included in Rev Man) require a normal distribution of data. The software is robust towards some skew, but to which degree of skewness meta‐analytic calculations can still be reliably carried out is unclear. On the other hand, excluding all studies on the basis of estimates of the normal distribution of the data also leads to a bias, because a considerable amount of data may be lost leading to a selection bias. Therefore, we included all studies in the primary analysis. In a sensitivity analysis we excluded potentially skewed data applying the following rules: a) When a scale started from the finite number zero the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was more than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, Altman 1996). b) If a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score c) In large studies (as a cut‐off we used 200 participants) skewed data pose less of a problem. In these cases we entered the data in a synthesis. d) The rules explained in a) and b) do not apply to change data. The reasons is that when continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values, it is difficult to tell whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. This is also the case for change data (endpoint minus baseline). In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if data are skewed, though this is likely. After consulting the ALLSTAT electronic statistics mailing list, we presented change data in RevMan Analyses in order to summarise available information. In doing this, it was assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analysis could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Without individual patient data it is impossible to test this assumption. Change data were therefore included and a sensitivity analysis was not applied. For continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (MD) between groups. We combined both endpoint data and change data in the analysis, because there is no principal statistical reason why endpoint and change data should measure different effects (Higgins 2008). When standard errors instead of standard deviations (SD) were presented, we converted the former to standard deviations. If both were missing we estimated SDs from p‐values or used the average SD of the other studies (Furukawa 2006).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ "cluster randomisation" (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a "unit of analysis" error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes Type 1 errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a "design effect". This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect=1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, we synthesised these with other studies using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups Where a study involved more than two treatment groups, if relevant, the additional treatment groups were presented in additional relevant comparisons. Data were not double counted. Where the additional treatment groups were not relevant, these data were not reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

At some degree of loss of follow‐up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). Although high rates of premature discontinuation are a major problem in this field, we felt that it is unclear which degree of attrition leads to a high degree of bias. We, therefore, did not exclude trials on the basis of the percentage of participants completing them. However we addressed the problem of participants leaving the study early in all parts of the review, including the abstract. For this purpose we calculated, presented and commented on frequency statistics (overall rates of leaving the studies early in all studies and comparators pooled).

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity We considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge for clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical 2.1 Visual inspection We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I2 statistic Visual inspection was supplemented using, primarily, the I2statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50% we interpreted this as indicating the presence of considerable levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We entered data from all identified and selected trials into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias. A formal test for funnel‐plot asymmetry was not undertaken.

Data synthesis

Where possible, for both dichotomous and continuous data we used the random‐effects model for data synthesis as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random‐effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies ‐ those trials that are most vulnerable to bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data are clearly heterogeneous we checked that data were correctly extracted and entered and that we had made no unit of analysis errors. If inconsistency was high and clear reasons explaining the heterogeneity were found, we presented the data separately. If not, we commented on the heterogeneity of the data.

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analyses we excluded studies with potentially skewed data. A recent report showed that some of the comparisons of atypical antipsychotics may have been biased by using inappropriate comparator doses (Heres 2006). We, therefore, also analysed whether the exclusion of studies with inappropriate comparator doses changed the results of the primary outcome and the general mental state.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

The search strategy yielded 3620 reports of which 23 were closely inspected. After excluding ten studies,16 publications on ten trials and three comparisons met the inclusion criteria: amisulpride versus olanzapine (N=5), amisulpride versus risperidone (N=4) and amisulpride versus ziprasidone (N=1).

Included studies

For details of the included studies please see Characteristics of included studies. The ten included studies randomised 1549 people, all ten studies were double blind. Six studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies producing amisulpride. Three studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies marketing the comparator antipsychotic drug. The sponsoring of the remaining trial was unclear.

1. Length of studies Six of the included studies fell in the short term category with a duration of 6‐12 weeks. The remaining four studies fell in the medium term categories and had a duration of 24‐26 weeks. There were no long term studies.

2. Setting Wagner 2005 was conducted only in hospitals and Olie 2006 only in outpatient departments. Five studies reported the setting as in‐ and outpatient, while the setting of three remaining studies setting was not reported.

3. Participants All participants were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Version III‐R or Version IV). One study group additionally used the International Classification of Disease Version 10 (Wagner 2005). Two studies explicitly included only people with chronic schizophrenia (Olie 2006, Sechter 2002), but the participants of the other studies were also relatively chronic, with a mean illness duration of over eight years. Möller 2005 restricted its inclusion criteria to elderly people over the age of 65 years. Vanelle 2006 examined those with schizophrenia and comorbid depression, Lecrubier 2006 included only participants with predominant negative symptoms. There were no studies randomising acutely ill people or people with a first episode of schizophrenia.

4. Study size The largest study was Mortimer 2004 and included 377 participants, the smallest study was Möller 2005 which included 36 participants. Five studies included more and five studies included less than 100 people.

5. Interventions 5.1 Amisulpride In seven studies amisulpride was given in flexible doses with varying dose ranges between 100‐1000 mg per day. Two studies used fixed doses of 150 mg per day (Lecrubier 2006) and 800 mg per day (Peuskens 1999). 5.2 Comparator Comparators were olanzapine (dose range: 5‐20mg/day), risperidone (1 to 10mg/day) and ziprasidone (80 ‐160mg/day).

6. Outcomes 6.1 General remarks Most reports described the number of participants leaving the studies early due to any reason, adverse events and lack of efficacy. We prespecified 50% PANSS/BPRS reduction from baseline as a clinically relevant measure of response, but not all studies reported data on this cutoff. Mortimer 2004 indicated the criterion at least 50% BPRS reduction from baseline, Wagner 2005 used at least 50 % PANSS total score reduction from baseline, Lecrubier 2006 combined at least 20% SANS total score reduction and 10% PANSS total score reduction and Vanelle 2006 used the criterion CGI "at least very much" or "much improved". Data on relapse were only provided by Sechter 2002 and Lecrubier 2006.

6.2 Outcome scales Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusion of data from other instruments are given under 'Outcomes' in the Characteristics of included studies.

6.2.1 Global state 6.2.1.1 Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI Scale (Guy 1976) This scale is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement.

6.2.2 Mental state 6.2.2.1 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1986) This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from 1 ‐ absent to 7 ‐ extreme. It can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity.

6.2.2.2 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) This scale is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from 0‐6 or 1‐7. Scores can range from 0‐126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Some studies extracted the BPRS scores from the PANSS.

6.2.2.3 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1984) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of the following negative symptoms; alogia, affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

6.2.2.4 Global cognitive index ‐ GCI (Wagner 2005) For cognitive assessment Wagner 2005 used a global cognitive index that was constructed by summing and averaging the z‐scored variables of various cognitive tests.

6.2.3 Adverse effects 6.2.3.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale ‐ AIMS (Guy 1976) This scale has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long‐term, drug‐induced movement disorder and short‐term movement disorders such as tremor.

6.2.3.2 Simpson Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) This ten‐item scale, with a scoring system of 0‐4 for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

6.2.4 Social functioning 6.2.4.1 Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment scale‐ SOFAS (Goldman 1992) The SOFAS focuses on the different levels of social and occupational functioning. Higher scores indicate a higher level of functioning.

6.2.4.2 Quality of Life Scale ‐ QLS (Carpenter 1984) This semi‐structured interview is administered and rated by trained clinicians. It contains 21 items rated on a seven‐point scale based on the interviewers judgement of patient functioning. A total QLS and four sub‐scale scores are calculated, with higher scores indicating better quality.

6.3 Missing outcomes We identified no useable data on service use.

Excluded studies

For details of the excluded studies please see Characteristics of excluded studies The search strategy yielded 3620 reports. From these we requested 23 studies for closer inspection. Twelve of these studies had to be excluded for the following reasons: six were not randomised, three were open label, two studies pooled analysis and the intervention of one study did not fit our protocol criteria.

2. Awaiting assessment Forty seven studies are awaiting assessment.

3. Ongoing studies No studies are ongoing.

Risk of bias in included studies

Judgements of risk are summarised in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials, but details about the randomisation procedure were provided by only two studies. Mortimer 2004 used a computer generated randomisation sequence and provided additional information on allocation concealment. Wagner 2005 used medication containers according to a pseudo‐random computer, but information on allocation concealment was not provided. Therefore whether randomisation procedure was adequate remained unclear for nine of the ten included studies.

Blinding

All but one study were described as double‐blind but only two provided further information, Mortimer 2004 and Peuskens 1999 described using identical capsules for blinding. Whether blinding was effective is unclear, because none of the studies examined this. The side‐effect profiles of the compounds may differ which may have made blinding difficult. Therefore, the risk of bias for objective outcomes (e.g. death or laboratory values) may have been low, but there was a risk of bias for subjective outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

The overall rate of leaving the study early was considerable (34.7%). In five studies (Lecrubier 2006, Mortimer 2004, Peuskens 1999, Sechter 2002, Wagner 2005) the rate of leaving the study early was above 30%, and one study did not provide data on overall attrition rates (Möller 2005). We considered the risk of bias in these six studies to be high. Olie 2006 reported an intermediate degree of attrition 25%. In Bai 2005 and Hwang 2003 the risk of bias was low, because the rates of leaving the study early was below 10% and reasons were reported. In Vanelle 2006 the overall attrition was probably acceptable (14.7%), but there was a high number of major protocol deviations. Most studies applied the last‐observation‐carried‐forward method to account for participants leaving the study early which is an imperfect method. It assumes that a participant who left the study prematurely would not have had a change of his condition if they had stayed in the study. This assumption can often be wrong. This may be less of a problem in the studies with low attrition, but clearly problematic in studies with high attrition.

Selective reporting

In all included studies this risk of bias was high, either because they did not report on certain outcomes (Bai 2005, Hwang 2003, Lecrubier 2006, Mortimer 2004, Möller 2005, Olie 2006, Peuskens 1999, Vanelle 2006, Wagner 2005) or because they only reported those side effects with an incidence of at least 5% or 10% (Hwang 2003, Lecrubier 2006, Mortimer 2004, Olie 2006, Peuskens 1999, Sechter 2002). This procedure is problematic because rare but potentially serious side‐effects may be missed.

Other potential sources of bias

Nine of the included studies were industry sponsored, for one study (Bai 2005) sponsoring remained unclear. There is evidence that pharmaceutical companies sometimes highlight the benefits of their compounds and tend to suppress their disadvantages (Heres 2006). The study sponsored by ziprasidone's manufacturer (Olie 2006) used an amisulpride dose (maximum 200mg/day) that may have been too low, because ziprasidone was used in the full dose (maximum 160mg/day).

Effects of interventions

COMPARISON 1. AMISULPRIDE versus OLANZAPINE Five studies provided data for the comparison amisulpride versus olanzapine.

1.1 Global state 1.1.1 No clinically significant response (as defined by original studies) There was no significant difference in terms of response to treatment as defined by various criteria (n=724, 4 RCTs, RR 1.03 CI 0.87 to 1.22).

1.1.2 No clinically important change (as defined by original studies) There was no significant difference (n=314, 3 RCTs, RR 0.91 CI 0.70 to 1.19).

1.1.3 Relapse ‐ medium term (as defined by original studies) Only Lecrubier 2006 reported on relapse but did not find a significant difference (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 0.93 CI 0.40 to 2.18).

1.2 Leaving the study early There was no significant difference in terms of leaving the study early due to any reason (n=804, 5 RCTs, RR 1.07 CI 0.9 to 1.26), due to adverse events (n=724, 4 RCTs, RR 1.19 CI 0.74 to 1.92), or due to inefficacy of treatment (n= 724, 4 RCTs, RR 1.19 CI 0.71 to 1.99).

1.3 Mental state 1.3.1 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term ‐ less than 50% PANSS total reduction A single study revealed no significant difference (n=52, 1 RCT, RR 0.69 CI 0.40 to 1.18).

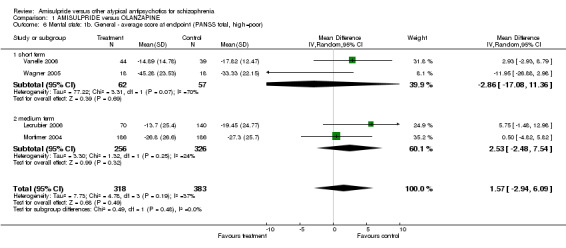

1.3.2 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS total score Four studies did not show a significant difference overall (n=701, 4 RCTs, MD 1.57 CI ‐2.94 to 6.09), short term (n=119, 2 RCTs, MD ‐2.86 CI ‐17.08 to 11.36), medium term (n=582, 2 RCTs, MD 2.53 CI ‐2.48 to 7.54).

1.3.3 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ medium term ‐ less than 50% BPRS total reduction Only one study provided data for this outcome and found no significant difference (n=377, 1 RCT, RR 1.09 CI 0.88 to 1.36).

1.3.4 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ BPRS total score There was no significant difference in the overall analysis (n=665, 3 RCTs, MD 1.26 CI ‐0.82 to 3.34), short term (n=83, 1 RCT, MD 1.40 CI ‐2.18 to 4.98) and medium term (n=582, 2 RCTs, MD 1.39 CI ‐2.04 to 4.83).

1.3.5 Positive symptoms ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term ‐ less than 50% PANSS positive symptom reduction The results are based on only one study that revealed no significant difference (n=52, 1 RCT, RR 0.69 CI 0.36 to 1.33).

1.3.6 Positive symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS positive subscore Four studies reported on the PANSS positive subscore. There was no significant difference between groups in the overall analysis (n=701, 4 RCTs, MD 0.66 CI ‐0.56 to 1.88), short term (n=119, 2 RCTs, MD 0.15 CI ‐2.27 to 2.57) and medium term (n=582, 2 RCTs, MD 0.98 CI ‐1.16 to 3.12).

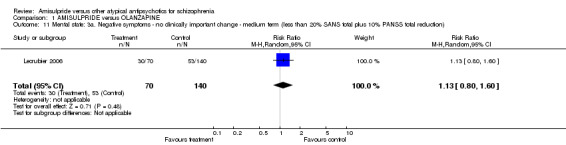

1.3.7 Negative symptoms: no clinically important change ‐medium term ‐ less than 20% SANS total plus 10% PANSS total reduction One study found was no significant difference (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 1.13 CI 0.80 to 1.60).

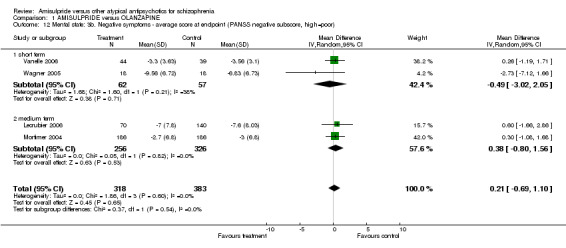

1.3.8 Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS negative subscore Four studies reported on the PANSS negative subscore. Again, there was no significant difference between groups in the overall analysis (n= 701, 4 RCTs, MD 0.21 CI ‐0.69 to 1.10), short term (n=119, 2 RCTs, MD ‐0.49 CI ‐3.02 to 2.05) and medium term (n=582, 2 RCTs, MD 0.38 CI ‐0.80 to 1.56).

1.3.9 Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ SANS total score There was no significant difference (n=243, 2 RCT, MD 0.00 CI ‐1.43 to1.43) in the overall analysis, short term (n=33, 1 RCT, MD ‐8.62 CI ‐27.69 to 10.45) and medium term (n=210, 1 RCT, MD 0.05 CI ‐1.39 to 1.49).

1.4 General functioning ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ SOFAS total score ‐ percent change There was no significant difference (n=359, 1 RCT, MD 0.20 CI ‐10.54 to10.94).

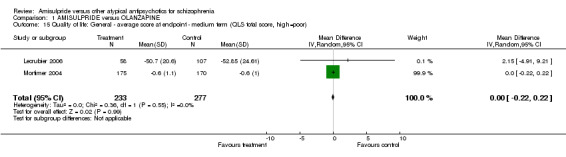

1.5 Quality of life ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ medium term ‐ QLS total score Data on quality of life did not show a significant difference (n=510, 2 RCTs, MD 0.00 CI ‐0.22 to 0.22).

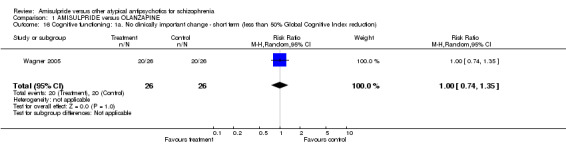

1.6 Cognitive functioning 1.6.1 Cognitive functioning: no clinically important change ‐ short term ‐ less than 50 % Global cognitive index reduction. There was no significant difference (n=52 ,1 RCT, RR 1.00 CI 0.74 to 1.35).

1.6.2 Cognitive functioning ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ short term ‐ Global Cognitive Index There was no significant difference (n=36, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.13, CI ‐0.35 to 0.09).

1.7 Adverse effects 1.7.1 General ‐ at least one adverse effect There was no significant difference (n=462, 2 RCTs, RR 1.03, CI 0.87 to 1.21).

1.7.2 Death Two studies reported on death with no significant difference between treatment and control groups, neither for natural causes (n=377, 1 RCT, RR 2.98 CI 0.12 to 72.79) nor for suicide (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 0.33, CI 0.01 to 8.09). Suicide attempts did also not occur in significantly different frequency (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 0.67 CI 0.07 to 6.29).

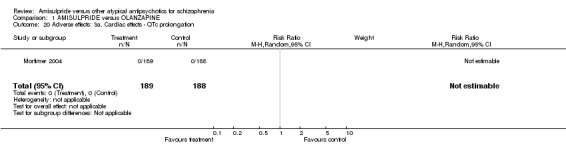

1.7.3 Cardiac effects ‐ number of participants with QTc prolongation In Mortimer 2004 there was no occurrence of QTc prolongation in either group, the other studies did not provide any data on this outcome.

1.7.4 Cardiac effects ‐ change of QTc interval from baseline in ms There was no significant difference in the mean prolongation of the QTc interval (n=303, 2 RCTs, MD 5.25 CI ‐0.57 to 11.07).

1.7.5 Central nervous system ‐ sedation There was no significant difference (n=587, 2 RCTs, RR 1.22 CI 0.64 to 2.34).

1.7.6 Central nervous system ‐ seizures There was no significant difference (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 0.66 CI 0.03 to 16.04).

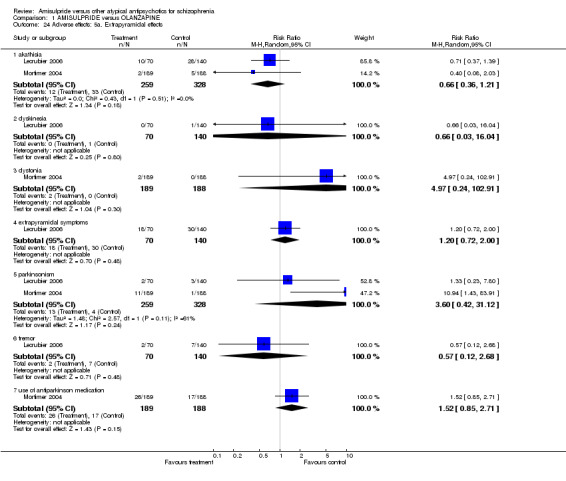

1.7.7 Extrapyramidal effects Extrapyramidal side effects were reported as akathisia (n= 587, 2 RCTs, RR 0.66 CI 0.36 to 1.21), dyskinesia (n= 210, 1 RCT, RR 0.66 CI 0.03 to 16.04), dystonia (n=377, 1 RCT, RR 4.97 CI 0.24 to 102.91), extrapyramidal symptoms (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 1.2 CI 0.72 to 2.00), parkinsonism (n=587, 2 RCTs, RR 3.60 CI 0.42 to 31.12), tremor (n= 210, 1 RCT, RR 0.57 CI 0.12 to 2.68) and use of antiparkinson medication (n=377, 1 RCT, RR 1.52 CI 0.85 to 2.71). There was no statistically significant difference in these side effects between amisulpride and olanzapine.

1.7.8 Extrapyramidal effects ‐ scale measured Scale derived data on extrapyramidal side‐effects using the Aquired Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS, n=356, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.40 CI‐1.13 to 0.33) or the Simpson Angus Scale (SAS, n=206, 2 RCTs, MD 0.00 CI ‐0.08 to 0.08) indicated no significant difference between amisulpride and olanzapine.

1.7.9 Haematological ‐ white blood cell count ‐ leukopenia There was no significant difference (n=210, 1 RCT, RR 0.40 CI 0.02 to 8.16).

1.7.10 Prolactin associated side effects There was no significant difference in prolactin associated side effects reported as sexual dysfunction (n=521, 2 RCTs, RR 1.36 CI 0.14 to12.94), amenorrhea (n=66, 1 RCT, RR 1.53 CI 0.28 to 8.48) and galactorrhea (n=66, 1 RCT, RR 6.71 CI 0.29 to 158.10).

1.7.11 Metabolic ‐ cholesterol ‐ change from baseline in mg/dl There was no significant difference in the mean change of total cholesterol from baseline (n=85, 1 RCT, MD ‐3.42 CI ‐12.32 to 5.48).

1.7.12 Metabolic ‐ glucose ‐ number of participants with diabetes mellitus There was no significant difference in the number of participants with elevated glucose levels (n=377, 1 RCT, RR 0.33 CI 0.01 to 8.09).

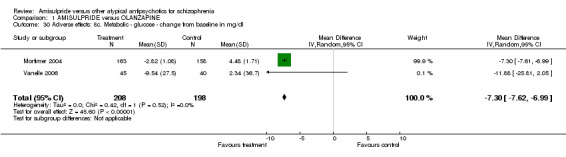

1.7.13 Metabolic ‐ glucose ‐ change from baseline in mg/dl Amisulpride was associated with significantly less increase of glucose levels from baseline than olanzapine (n=406, 2 RCTs, MD ‐7.30 CI ‐7.62 to ‐6.99).

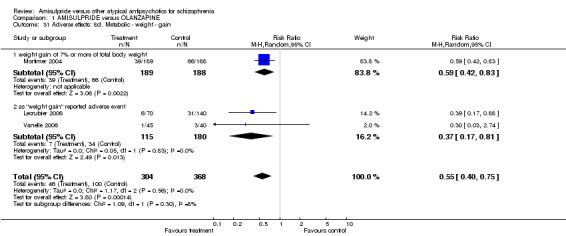

1.7.14 Metabolic ‐ weight ‐ number of participants with weight gain Weight gain was reported by three studies, either as weight gain reported adverse event or as weight gain of 7% or more of total body weight. Overall there was a significant difference favouring amisulpride (n=672, 3 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.40 to 0.75, NNT 9, CI 6 to 20).

1.7.15 Metabolic ‐ weight ‐ change from baseline in kg When weight gain was analysed as a mean change from baseline in kg the results also showed a significant superiority of amisulpride (n=671, 3 RCTs, MD ‐2.11 CI ‐2.94 to ‐1.29).

1.8 Publication bias Due to small number of included studies a funnel plot analysis was not performed.

1.9 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis The reasons for the preplanned sensitivity analysis did not apply and were therefore not performed. COMPARISON 2. AMISULPRIDE versus RISPERIDONE Four studies provided data for the comparison amisulpride versus risperidone. 2.1Global state 2.1.1 No clinically significant response ‐ as defined by original studies The results of three studies were slightly heterogeneous (I2 54%). The combined analysis did not indicate a difference (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.89 CI 0.67 to 1.20), but when (Hwang 2003) was excluded there was a significant superiority of amisulpride (n=541, 2 RCTs, RR 0.80 CI 0.67 to 0.95, NNT 9 CI 5 to 50).

2.1.2 No clinically important change ‐ as defined by original studies Overall there was no significant difference (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.89 CI 0.67 to 1.20), but some degree of heterogeneity (I2 54%). The short term study Peuskens 1999 (n=86, RR 0.78 CI =0.56 to 1.09) and the medium term study Sechter 2002 (n=310, 1 RCT, RR 0.79 CI 0.61 to 1.01) indicated a slight but not significant benefit for the treatment group, which was not seen in the other short term study Hwang 2003 (n=24, RR 1.52, CI 0.85 to 2.72).

2.1.3 Relapse ‐ medium term ‐ as defined by original studies There was no significant difference (n=173, 1 RCT, RR 0.67 CI 0.42 to 1.07).

2.2 Leaving the study early There was no significant difference in terms of leaving the study early due to any reason (n= 586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.98 CI 0.65 to 1.47), due to adverse events (n=622, 4 RCTs, RR 1.08 CI 0.70‐ 1.65) or due to inefficacy of treatment (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.69 CI 0.39 to 1.21).

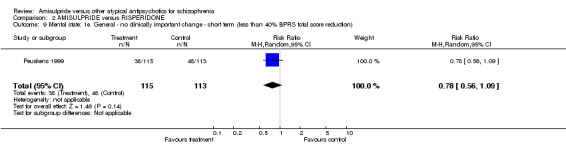

2.3 Mental state 2.3.1 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ less than 50% PANSS reduction There was a trend in favour of amisulpride which did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (n=310, 1 RCT, RR 0.81 CI 0.65 to 1.00). 2.3.2 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term ‐ less than 20% PANSS reduction When this cutoff was applied there was no significant difference (n=48, 1 RCT, RR 1.45 CI 0.59 to 3.54).

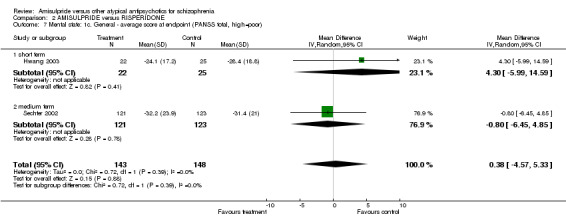

2.3.3 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS total There was no significant difference (n=291, 2 RCTs, MD 0.38 CI ‐4.57 to 5.33).

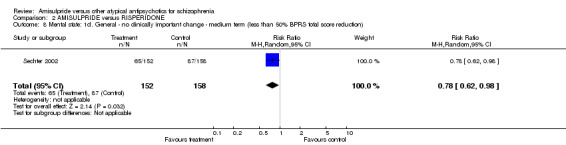

2.3.4 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ less than 50% BPRS reduction There was a significant difference favouring amisulpride (n=310, 1 RCT, RR 0.78 CI 0.62 to 0.98, NNT 8 CI 4 to 100).

2.3.5 General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term ‐ less than 40% BPRS reduction There was no significant difference (n=228, 1 RCT, RR 0.78, CI 0.56 to 1.09). 2.3.6 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ BPRS total There was no significant difference (n=519, 3 RCTs, MD ‐0.68 CI ‐3.14 to 1.79) in the overall analysis, short term (n=275, 2 RCTs, MD ‐0.50 CI ‐5.53 to 4.54) and medium term (n=244, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.20 CI ‐3.68 to 3.28).

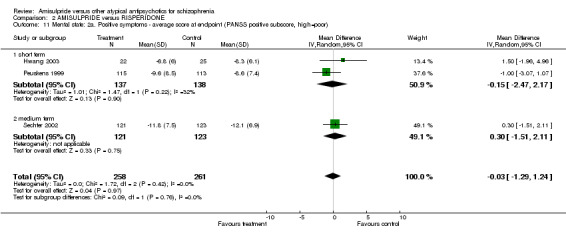

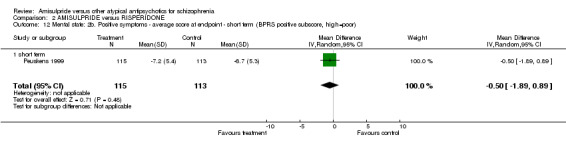

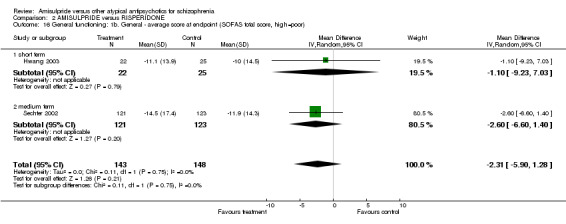

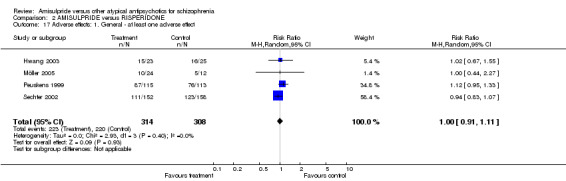

2.3.7 Positive symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS positive subscore There was no significant difference (n=519, 3 RCTs, MD ‐0.03 CI ‐1.29 to 1.24) in the overall analysis, short term (n=275, 2 RCTs, MD ‐0.15 CI ‐2.47 to 2.17) and medium term (n=244, 1 RCT, MD 0.30 CI ‐1.51 to 2.11). 2.3.8 Positive symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ short term‐ BPRS positive subscore There was no significant difference (n=228, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.50 CI ‐1.89 to 0.89). 2.3.9 Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS negative subscore There was no significant difference (n= 519, 3 RCTs, MD ‐1.00 CI ‐2.11 to 0.11) in the overall analysis, short term (n=275, 2 RCTs, MD ‐0.60 CI ‐2.92 to 1.72) and medium term (n=244, 1 RCT, MD ‐1.20 CI ‐2.61 to 0.21). 2.3.10 Negative Symptoms: SANS total score There was no significant difference (n=244, 1 RCT, MD ‐2.70 CI ‐7.73 to 2.33). 2.4 General functioning 2.4.1 No clinically important change ‐ less than 50% SOFAS total score reduction There was a trend in favour of amisulpride which did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (n=310, 1 RCT, RR 0.90 CI 0.80 to 1.01). 2.4.2 Average score at endpoint ‐ SOFAS total score There was no significant difference in the overall analysis (n=291, 2 RCTs, MD ‐2.31 CI ‐5.90 to 1.28), short term (n=47, 1 RCT, MD ‐1.10 CI ‐9.23 to 7.03) and medium term (n=244, 1 RCT, MD ‐2.60 CI ‐6.60 to 1.40). 2.5 Adverse effects 2.5.1 General ‐ at least one adverse effect There was no significant difference (n=622, 4 RCTs, RR 1.00 CI 0.91 to 1.11).

2.5.2 Death Only one study provided data on death. There was no significant difference in terms of natural causes (n=310, RR 3.12 CI 0.13 to 75.94) or suicide (n=310, RR 2.08 CI 0.19 to 22.69).

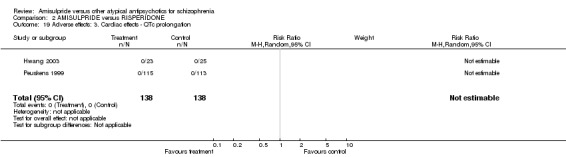

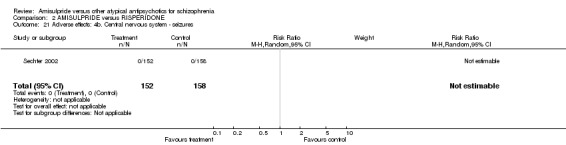

2.5.3 Cardiac effects ‐ QTc prolongation Two studies (Hwang 2003, Peuskens 1999) described no incidence of QTc prolongation. 2.5.4 Central nervous system ‐ sedation There was no significant difference between amisulpride and risperidone (n=310, 1 RCT, RR 0.69 CI 0.29 to 1.65). 2.5.5 Central nervous system ‐ seizures There were no seizures neither in the treatment nor in the control group.

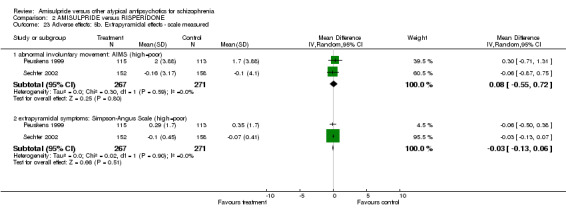

2.5.6 Extrapyramidal effects Extrapyramidal symptoms were reported as akathisia (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.80 CI 0.58 to 1.11), extrapyramidal symptoms (n=228, 1 RCT, RR 1.13 CI 0.77 to 1.67), hyperkinesia (n=538, 2 RCTs, RR 1.33 CI 0.88 to 2.03), parkinsonism (n=538, 2 RCTs, RR 0.88 CI 0.51 to 1.51), rigor (n=276, 2 RCTs, RR 0.93 CI 0.23 to 3.77), tremor (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.69 CI 0.31 to 1.51) and use of antiparkinson medication (n=586, 3 RCTs, RR 0.94 CI 0.64 to 1.38). There was no significant difference between amisulpride and risperidone.

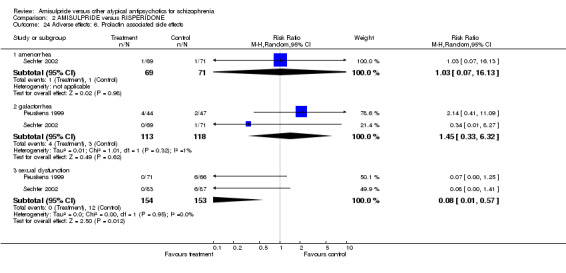

2.5.7 Extrapyramidal side effects ‐ scale measured Continuous data on extrapyramidal side effects were examined with the AIMS (n=538, 2 RCTs, MD 0.08 CI ‐0.55 to 0.72) and the SAS scale ( n=538, 2 RCTs, MD ‐0.03 CI ‐0.13 to 0.06).There was no significant difference between amisulpride and risperidone. 2.5.8 Prolactin associated side effects Prolactin associated side effects were reported as amenorrhoea (n=140, 1 RCT, RR 1.03 CI 0.07 to 16.13) and galactorrhoea (n=231, 2 RCTs, RR 1.45 CI 0.33 to 6.32). There was no significant difference. Fewer participants in the amisulpride group than in the risperidone group suffered from sexual dysfunction (n=307, 1 RCT, RR 0.08 CI 0.01 to 0.57, NNT 13 CI 8 to 33).

2.5.9 Metabolic ‐ weight ‐ number of participants with significant weight gain Fewer participants in the amisulpride groups than in the risperidone groups gained weight (n=538, 2 RCTs, RR 0.57 CI 0.35 to 0.95, NNT 20 CI 9 to 50).

2.5.10 Metabolic ‐ weight ‐ change from baseline in kg The mean weight gain in the amisulpride groups was smaller than in the risperidone groups (n=585, 3 RCTs, MD ‐0.99 CI ‐1.61 to ‐0.37).

2.6 Publication bias: Due to small number of included studies a funnel plot analysis was not performed.

2.7 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis: The reasons for the preplanned sensitivity analysis did not apply and were therefore not performed.

COMPARISON 3. AMISULPRIDE versus ZIPRASIDONE ‐ all data short term Only one study (Olie 2006) provided data for the comparison amisulpride versus ziprasidone.

3.1 Global state 3.1.1 No clinically significant response ‐ as defined by the original studies There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.95 CI 0.84 to 1.08).

3.1.2. No clinically important change ‐ as defined by the original studies There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.90 CI 0.66 to 1.22).

3.2 Leaving the study early There was no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the study early due to any reason (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.69 CI 0.37 to 1.28) or adverse effects (n= 123, 1 RCT, RR 1.27 CI 0.30 to 5.44). However, significantly more participants in the ziprasidone group left the study early due to inefficacy of treatment (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.21 CI 0.05 to 0.94, NNT 8 CI 5 to 50). 3.3 Mental State: 3.3.1 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS total There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, MD ‐ 2.70 CI ‐9.04 to 3.64). 3.3.2 General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ BPRS total There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, MD ‐ 2.10 CI ‐5.72 to 1.52). 3.3.3 Negative symptoms ‐ no clinically important change ‐ less than 50% PANSS negative reduction There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.95 CI 0.84 to 1.08). 3.3.4 Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ PANSS negative subscore There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.80 CI ‐3.00 to 1.40). 3.4 Adverse effects 3.4.1 General ‐ at least one adverse effect There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.90 CI 0.66 to 1.22).

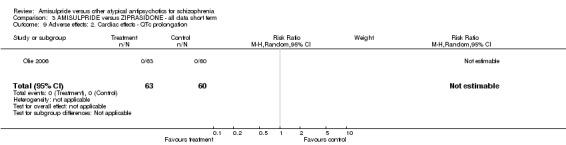

3.4.2 Cardiac effects ‐ QTc prolongation There was no occurrence of QTC prolongation in either group.

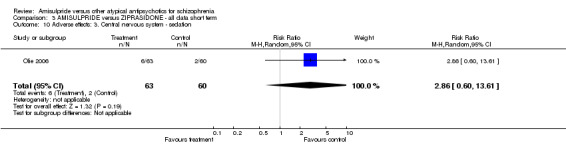

3.4.3 Central nervous system ‐ sedation There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 2.86 CI 0.60 to 13.61).

3.4.4 Extrapyramidal effects Extrapyramidal side effects were described as akathisia (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.63, CI 0.11 to 3.67), parkinsonism (n=123, RR 0.16 CI 0.02 to 1.28) and use of antiparkinson medication (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 0.59, CI 0.33 to 1.07). There was no significant difference between amisulpride and ziprasidone.

3.4.6 Metabolic ‐ weight ‐ gain of 7% or more of total body weight There was no significant difference (n=123, 1 RCT, RR 2.10 CI 0.77 to 5.67)

3.5 Publication bias Due to small number of included studies a funnel plot analysis was not performed.

3.6 Investigation of heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis Whether the amisulpride dose (maximum 200mg/day) in the single study available (Olie 2006) was appropriate can be questioned. The study was conducted in participants with predominant negative symptoms in which amisulpride doses between 50 and 300mg/day have been shown to be effective (Leucht 2002). Nevertheless, ziprasidone was given in full dose (maximum 160mg/day) and the degree of positive symptoms of the participants is unclear because it has not been reported. If this sensitivity analysis were performed, not a single study would be available.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We only identified 10 studies on three out of eight possible comparisons of amisulpride with other second generation antipsychotic drugs. The interpretation of the comparison of amisulpride with ziprasidone is especially difficult, because it is based on a single study. A considerable overall premature discontinuation rate of 35% calls the validity of the results into question. Furthermore, the longest studies lasted only six months. Long term data are not available which is far from ideal for judging the relative tolerability and efficacy of these compounds in a chronic disease like schizophrenia. Another aspect is the high proportion of industry sponsored trials. Nine out of ten studies were industry sponsored, and in the remaining one the sponsor is unclear. It has been shown in a blinded analysis of abstracts, that pharmaceutical companies emphasise the positive aspects of their compounds (Heres 2006). Systematic reviews can in part account for this effect by objectively summarising the data, but they can not cope with intentional omission of outcomes. Indeed, reporting was incomplete. For example, usable data on increase in prolactin levels, a frequent problem of amisulpride, were not available.

1. COMPARISON 1: AMISULPRIDE versus OLANZAPINE Most of the studies identified were included in this comparison (N=5, n=804). The number of participants leaving the studies early was considerable (37.2%), questioning the validity of the findings. One study provided hardly any data (Bai 2005). In our opinion five studies with 800 participants is not sufficient considering the high numbers of people with schizophrenia using either medication world‐wide.

1.1 Global state, general and specific mental state There were no statistically significant differences in any efficacy related outcome. The use of complex and difficult to understand rating scales such as the PANSS or the BPRS in addition to the small number of trials and participants limit the interpretation. Nevertheless, the available data do not support an obvious preference for either substance. 1.2 Leaving the study early All studies reported on 'leaving the study early due to any reason' which can be considered as a composite measure of acceptability of treatment. The acceptability of both compounds seems to be similar, at least in the context of clinical trials. 1.3 Quality of life, general functioning Only two studies provided data on this important outcome using the SOFAS and QLS scales. There was no apparent difference between amisulpride and olanzapine.

1.4 Cognition Only one study reported on cognitive functioning and found no significant difference (Wagner 2005). The lack of more data is unfortunate because cognitive functioning may be very important for a person's general overall functioning including the ability to work.

1.5 Adverse effects Reporting on adverse effects was incomplete. Only two studies Lecrubier 2006 and Mortimer 2004 reported on extrapyramidal symptoms, cardiac effects, effects on cholesterol, glucose levels and prolactin associated side effects, weight gain, white blood cell count, sedation or seizures and death. Among the analysed side effects only the difference of glucose change from baseline and weight change (2.1 kg more in the olanzapine groups) reached statistical significance favouring amisulpride. These metabolic effects are very serious issues. They may make amisulpride more recommendable than olanzapine for those at risk of developing a metabolic syndrome.

2. COMPARISON 2: AMISULPRIDE versus RISPERIDONE Four studies with 622 people randomised and a leaving the study rate of 33.2% could be included in this comparison. Again, more data are needed for firm conclusions. 2.1 Global state, general and specific mental state: Overall there was no clear efficacy difference between amisulpride and risperidone. There was a significant superiority of amisulpride in terms of 50% BPRS reduction. However, this result was based on only one trial and may have well occurred by chance alone given the high number of statistical tests applied (Sechter 2002).

2.2 Leaving the study early There was no significant difference in premature study discontinuations. The acceptability of both compounds seems to be similar, at least in the context of clinical trials.

2.3 General functioning A single study using the SOFAS scale reported on social functioning and found no difference between amisulpride and risperidone. Pragmatic studies that are conducted in situations that are more similar to routine care are needed to address this important outcome.

2.4 Adverse effects There were some data on extrapyramidal side effects, cardiac effects, prolactin associated side effects, sedation, seizures and death. Besides the reporting on sexual dysfunction which indicated a benefit for amisulpride, the only adverse event showing a significant difference was weight gain which was 1kg more in the risperidone group. This difference was found in short to medium term studies. It may well be that the difference would be more pronounced in the long term, but longer studies are needed to verify this assumption. Nevertheless, if metabolic issues are a concern, amisulpride may be a better choice than risperidone.

3. COMAPRISON 3: AMISULPRIDE versus ZIPRASIDONE Only one study (Olie 2006) with 123 randomised people and a drop out rate of 25% fell in this category. This number of randomised participants is even lower than in the other two comparisons. The study was conducted in participants with predominant negative symptoms, which may explain that only low doses of amisulpride (100‐200mg/day) were used. Indeed, it has been shown that low amisulpride doses are effective in such people (Leucht 2002). Nevertheless, it can be questioned whether the use of the full dose range of ziprasidone (80‐160 mg/day) is a fair comparison. We highlight that the degree of positive symptoms at baseline has not been indicated making it impossible to judge whether the low amisulpride doses were really appropriate.

3.1 Global state, general and specific mental state There was no difference in global state, general mental state and negative symptoms. However, results on positive symptoms have not been reported which is surprising because the participants were rated with PANSS scale which contains a subscale for positive symptoms. This may be a typical example of reporting bias in industry sponsored antipsychotic drug trials (Heres 2006).

3.2 Leaving the study early There was no difference in premature study discontinuations due to any reason. Therefore, in the short term both agents may be similarly acceptable for people with schizophrenia, at least in the context of a clinical trial. On the other hand significantly more participants in the ziprasidone group left the study early due to inefficacy of treatment. Amisulpride may thus be more effective than ziprasidone for people with chronic schizophrenia and predominant negative symptoms. As there was no difference in the number of participants leaving the studies early due to adverse events, the overall tolerability of amisulpride and ziprasidone may be similar.

3.3 Adverse effects Adverse effects reporting on at least one adverse effect, extrapyramidal side effects, QTc prolongation, sedation and weight gain revealed no statistically significant differences between groups suggesting that the tolerability of both compounds may be similar. Nevertheless, these results are based on a small, short term study which was underpowered to detect rare but serious effects such as seizures, agranulocytosis or sudden death.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There is only randomised evidence for only three out of eight possible comparisons of amisulpride with other second generation antipsychotic drugs. For most comparisons eg. amisulpride versus aripiprazole, clozapine, quetiapine, sertindole and zotepine not a single study was identified and overall evidence of amisulpiride's effectiveness compared with other newer antipsychotics is very incomplete. In the available studies the side effect reporting was especially incomplete. In particular, prolactin increase, a typical side effect of amisulpride, has not been reported. In terms of applicability of the evidence we highlight that all of the included studies were "efficacy" studies. Large and simple, pragmatic, effectiveness studies are not available, limiting external validity.

Quality of the evidence

Except for one (Bai 2005), all studies were randomised and double‐blind, but details rarely presented. Therefore in most of the studies it is unclear whether randomisation and blinding were really appropriately done. Furthermore often high rates of participants leaving the studies prematurely (five studies reported rates of more than 30%) and the lack of long term studies limit the overall quality. Additionally nine of the ten included trials were industry sponsored and in one a potential dose related bias could not be excluded. These factors limit the overall quality of the evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

We are not aware of obvious flaws in our review process. Due to small number of included studies we did not perform a funnel plot analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A previous Cochrane review compared the effects of amisulpride with those of any other antipsychotic drug in schizophrenia (Mota Neto 2002). The authors found no difference between amisulpride and risperidone, but at the time when the review was conducted only one study was available.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with schizophrenia and clinicians For people with schizophrenia it is important to know that amisulpride may be similarly effective as olanzapine or risperidone, and possibly somewhat more effective than ziprasidone. In terms of tolerability it seems to cause less weight gain than olanzapine and risperidone, and less glucose increase than olanzapine. Nevertheless, people with schizophrenia should also be aware that the available evidence is limited, and that the studies have not reported on other important side effects of amisulpride such as prolactin increase.

2. For clinicians Clinicians should know that randomised evidence of the effects of amisulpride compared with other second generation antipsychotic drugs is only available for olanzapine, risperidone and ziprasidone. Even this evidence is limited and more studies are needed to clarify the role of amisulpride compared with other second generation antipsychotic drugs.

3. For managers/policy makers Hardly any data are available that are relevant for policy makers such as service utilisation or functioning in society. We are thus unable to make any recommendations for managers or policy makers. Nevertheless, it may be important to know for them that amisulpride has lost its patent and is therefore available as a generic in many countries which may be cheaper than other second generation antipsychotic drugs.

Implications for research.

1. General Outcome reporting remains insufficient in antipsychotic drug trials. Strict adherence to the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001) would make such studies much more informative.

2. Specific There is a lot of room for further randomised controlled trials comparing amisulpride with other second generation antipsychotics. Comparisons with ariprazole, clozapine, quetiapine, sertindole and zotepine are currently missing. Table 1 we make a suggestion as to how such a study may look like.

1. Suggested design of future study.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised ‐ clearly described generation of sequence and concealment of allocation. Blindness: double ‐ described and tested. Duration: 6 months minimum. |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (operational criteria). N=2700.* Age: any. Sex: both. History: any. |

| Interventions | 1. Amisulpride: dose ˜ 400‐800 mg/day. N=300. 2. Aripiprazole: dose ˜ 10‐30 mg/day. N=300. 3. Clozapine: dose ˜ 300‐800 mg/day. N=300. 4. Olanzapine: dose ˜ 10‐20 mg/day. N=300. 5. Quetiapine: dose ˜300‐800 mg/day. N=300. 6. Risperidone: dose ˜ 4‐8 mg/day. N=300. 7. Sertindole: dose ˜ 12‐24 mg/day. N=300. 8. Ziprasidone: dose ˜ 120‐160 mg/day. N=300. 9. Zotepine: dose ˜ 100‐300 mg/day. N=300. |

| Outcomes | Leaving study early (any reason, adverse events, inefficacy). Service outcomes: hospitalised, time in hospital, attending out patient clinics. Global impression: CGI**, relapse. Mental state: PANSS. Adverse events: UKU. Employment, family satisfaction, patient satisfaction. |

* power calculation suggested 300/group would allow good chance of showing a 10% difference between groups for primary outcome. ** Primary outcome

3. Note: the 47 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 July 2012 | Amended | Update search of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trial Register (see Search methods for identification of studies), 47 studies added to awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 1, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

Acknowledgements

We thank the editorial base of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for its assistance. We also thank the following authors for providing additional information on their studies: T.Hwang, A.Mortimer, J.Peuskens, B.Quednow, D.Sechter and M.Wagner.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. AMISULPRIDE versus OLANZAPINE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global state: 1a. No clinically significant response (as defined by original studies) | 4 | 724 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.87, 1.22] |

| 2 Global State: 1b. No clinically important change (as defined by original studies) | 3 | 514 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.70, 1.19] |

| 2.1 short term | 2 | 137 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.55, 1.06] |

| 2.2 medium term | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.83, 1.35] |

| 3 Global State: 1c. Relapse ‐ medium term (as defined by the original studies) | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.40, 2.18] |

| 4 Leaving the study early | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 due to any reason | 5 | 804 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.90, 1.26] |

| 4.2 due to adverse events | 4 | 724 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.74, 1.92] |

| 4.3 due to inefficacy | 4 | 724 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.71, 1.99] |

| 5 Mental state: 1a. General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term (less than 50% PANSS total score reduction) | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.40, 1.18] |

| 6 Mental state: 1b. General ‐ average score at endpoint (PANSS total, high=poor) | 4 | 701 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.57 [‐2.94, 6.09] |

| 6.1 short term | 2 | 119 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.86 [‐17.08, 11.36] |

| 6.2 medium term | 2 | 582 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.53 [‐2.48, 7.54] |

| 7 Mental state: 1c. General ‐ no clinically important change ‐ medium term (less than 50% BPRS total score reduction) | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.88, 1.36] |

| 8 Mental state: 1d. General ‐ average score at endpoint (BPRS total, high=poor) | 3 | 665 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [‐0.82, 3.34] |

| 8.1 short term | 1 | 83 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.40 [‐2.18, 4.98] |

| 8.2 medium term | 2 | 582 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [‐2.04, 4.83] |

| 9 Mental state: 2a. Positive symptoms ‐ no clinically important change ‐ short term (less than 50% PANSS positive subscore reduction) | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.36, 1.33] |

| 10 Mental state: 2b. Positive symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint (PANSS positive subscore, high=poor) | 4 | 701 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [‐0.56, 1.88] |

| 10.1 short term | 2 | 119 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [‐2.27, 2.57] |

| 10.2 medium term | 2 | 582 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [‐1.16, 3.12] |

| 11 Mental state: 3a. Negative symptoms ‐ no clinically important change ‐ medium term (less than 20% SANS total plus 10% PANSS total reduction) | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.80, 1.60] |

| 12 Mental state: 3b. Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint (PANSS negative subscore, high=poor) | 4 | 701 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [‐0.69, 1.10] |

| 12.1 short term | 2 | 119 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐3.02, 2.05] |

| 12.2 medium term | 2 | 582 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.80, 1.56] |

| 13 Mental state: 3c. Negative symptoms ‐ average score at endpoint (SANS total score, high=poor) | 2 | 243 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐1.43, 1.43] |

| 13.1 short term | 1 | 33 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.62 [‐27.69, 10.45] |

| 13.2 medium term | 1 | 210 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐1.39, 1.49] |

| 14 General functioning: General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ medium term (SOFAS total ‐ percent change,high=poor) | 1 | 359 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [‐10.54, 10.94] |

| 15 Quality of life: General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ medium term (QLS total score, high=poor) | 2 | 510 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.22, 0.22] |

| 16 Cognitive functioning: 1a. No clinically important change ‐ short term (less than 50% Global Cognitive Index reduction) | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.74, 1.35] |

| 17 Cognitive functioning: 1b. General ‐ average score at endpoint ‐ short term (Global Cognitive Index, high=poor) | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.35, 0.09] |

| 18 Adverse effects: 1. General ‐ at least one adverse effect | 2 | 462 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.87, 1.21] |

| 19 Adverse effects: 2. Death | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 19.1 natural causes | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.98 [0.12, 72.79] |

| 19.2 suicide attempt | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.07, 6.29] |

| 19.3 suicide | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.09] |

| 20 Adverse effects: 3a. Cardiac effects ‐ QTc prolongation | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21 Adverse effects: 3b. Cardiac effects ‐ QTc abnormalities ‐ change from baseline in ms | 2 | 303 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 5.25 [‐0.57, 11.07] |

| 22 Adverse effects: 4a. Central nervous system ‐ sedation | 2 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.64, 2.34] |

| 23 Adverse effects: 4b. Central nervous system ‐ seizures | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.03, 16.04] |

| 24 Adverse effects: 5a. Extrapyramidal effects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 24.1 akathisia | 2 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.36, 1.21] |

| 24.2 dyskinesia | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.03, 16.04] |

| 24.3 dystonia | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.97 [0.24, 102.91] |

| 24.4 extrapyramidal symptoms | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.72, 2.00] |

| 24.5 parkinsonism | 2 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.60 [0.42, 31.12] |

| 24.6 tremor | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.12, 2.68] |

| 24.7 use of antiparkinson medication | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.85, 2.71] |

| 25 Adverse effects: 5b. Extrapyramidal effects ‐ scale measured | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 25.1 abnormal involuntary movement: AIMS (high=poor) | 1 | 356 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.4 [‐1.13, 0.33] |

| 25.2 extrapyramidal symptoms: Simpson‐Angus Scale (high=poor) | 2 | 406 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.08, 0.08] |

| 26 Adverse effects: 6. Haematological ‐ white blood cell count ‐ leukopenia | 1 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.02, 8.16] |

| 27 Adverse effects: 7. Prolactin associated side effects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 27.1 amenorrhea | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.53 [0.28, 8.48] |

| 27.2 galactorrhea | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.71 [0.29, 158.10] |

| 27.3 sexual dysfunction | 2 | 521 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.14, 12.94] |

| 28 Adverse effects: 8a. Metabolic ‐ cholesterol ‐ change from baseline in mg/dl | 1 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.42 [‐12.32, 5.48] |

| 29 Adverse effects: 8b. Metabolic ‐ glucose ‐ diabetes mellitus | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.09] |

| 30 Adverse effects: 8c. Metabolic ‐ glucose ‐ change from baseline in mg/dl | 2 | 406 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.30 [‐7.62, ‐6.99] |