Abstract

Introducton:

The COU-AA-301 trial showed that abiraterone acetate (abiraterone), an oral cytochrome p450 CYP17 inhibitor, improved survival for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) progressing after docetaxel. To better understand the non-clinical trial experience with abiraterone, we undertook a multicentre retrospective analysis of Canadian mCRPC patients treated with abiraterone.

Methods:

Consecutive patients with mCRPC who received abiraterone post-docetaxel were identified using centralized pharmacy records. These patients came from 5 Canadian tertiary cancer centres. Patients who received abiraterone for approved indications were included. Demographics, prognostic factors, treatment outcomes and adverse events were abstracted.

Results:

We included 187 patients who initiated abiraterone between January 2011 and June 2012. The median age at diagnosis and abiraterone start was 65 and 73 years, respectively. Seventy-three (39%) patients had metastatic disease at diagnosis. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, 1, 2 and 3 was noted in 17, 96, 39 and 8 patients, respectively. The median prostate-specific antigen (PSA) at abiraterone start was 132, with a median PSA doubling time of 2.8 months. The median follow-up of patients still on active follow-up was 13 months. The proportion of patients achieving a ≥50% PSA reduction was 64/177 (36%). PSA progression-free survival was 3.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0, 4.0). Median overall survival from start of abiraterone was 11 months (95% CI, 8.0, 13) and 38 months (95% CI, 31, 41) from date of mCRPC. Anemia and fatigue were the most commonly reported adverse events.

Conclusions:

This study carries the inherent limitations of a retrospective chart review. The outcomes in this series of men treated with abiraterone in a non-trial setting were expected, considering previous clinical trials. Our results, therefore, support the generalizability of the COU-AA-301 study results.

Introduction

Prostate cancer growth is fuelled by androgens; physiological levels of androgens stimulate prostate cancer proliferation and inhibit apoptotic death.1 Androgen deprivation therapy is first-line treatment for men with metastatic prostate cancer, but eventually the disease relapses due to growth of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). The development of CRPC is multifactorial and results from the growth of prostate cancer cells that adapt to a hormone-deprived environment.2 This can be a consequence of a hypersensitive phenotype of the androgen receptor, which is often compounded by an increase in extragonadal or de novo intratumoralandrogen production.3 Targeting pathways that deplete the source of additional androgens can alter the biology and clinical course of CRPC.2

Abiraterone acetate (abiraterone) is a novel oral agent that specifically inhibits the activity of CYP17 (17-[alpha]-hydroxylase/17, 20-lyase), a key enzyme required for bio-synthesis of androgens in the adrenal glands and in tumour tissues.4–7 Abiraterone has undergone extensive clinical studies, which have established the drug as a safe and efficacious therapy for men with CRPC.8–13 A recent placebo-controlled phase III trial (COU-AA-301) demonstrated the efficacy of this agent in improving survival for patients with progressing metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) after docetaxel therapy.14 In this study, the median overall survival for patients receiving abiraterone plus prednisone was 14.8 months, compared with 10.9 months in the placebo plus prednisone arm. Following the results of this trial, abiraterone was made available to clinicians on a special access program. It received FDA approval in April 2011, and Health Canada approval in February 2012.

In this retrospective study, we evaluate the effects and tolerability of abiraterone outside the controlled setting of a clinical trial. We examined the use of abiraterone among non-clinical trial patients from 5 cancer centres across 3 Canadian provinces.

Methods

Patients

Research ethics board approval was obtained at each participating centre. Using centralized pharmacy records for each centre, we identified consecutive patients with mCRPC who had received abiraterone post-docetaxel from 5 tertiary cancer centres within 3 Canadian provinces. Patients who received abiraterone for approved indications or within expanded access programs were included, but those who participated in the COU-AA-301 trial were excluded. Patients were not excluded on the basis of any other factors. Men with mCRPC who initiated abiraterone between January 2011 and June 2012 were included in this analysis.

Data collection and outcomes of interest

In total, 4 data abstractors were responsible for populating the database from the 5 tertiary cancer centres. Electronic medical records and paper charts were retrospectively reviewed. Baseline factors of interest were province of treatment, metastatic disease at initial presentation of prostate cancer diagnosis (M0 vs. M1 at diagnosis), and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) doubling time immediately prior to initiating abiraterone. The primary outcome of interest was overall survival from date of abiraterone start and from date of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer diagnosis (mCRPC). The date of mCRPC was defined as the date when both of the following factors were met: (1) metastatic disease as documented by positive bone or computed tomography (CT) scan; and (2) first date of 3 sequential increases in the PSA level at a minimum of 1-week intervals, development of nodal or visceral lesions, or growth of measurable disease with serum testosterone <1.7 nmol/L. Secondary outcomes of interest were PSA response, disease progression and adverse events. PSA response was defined as a decrease in PSA value of ≤50% from pre-abiraterone PSA.15 PSA progression was defined as per COU-AA-301 study.14 PSA progression-free survival (PSA-PFS) was defined as the time from first dose of abiraterone to the first event of PSA progression or death. Radiological progression was defined according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).16 Clinical progression was determined by a physician based on clinical chart documentation of pain or symptom progression. Adverse events were collected from the patient chart and scored based on the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria Version 3.0.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized descriptively by frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, and measures of central tendencies for numeric variables, according to treatment province. PSA doubling time (PSAdt) was calculated by determining the regression slope of the log (natural log) PSA against time based on 3 PSA measurements prior to abiraterone initiation. As the distribution of doubling times were highly skewed, with a median positive PSAdt of 2.7 months, patients were further classified into 3 groups according to their PSAdt: (1) “long” (PSAdt ≥3 months); (2) “short” (PSAdt 0–3 months); and (3) “negative” (non-rising PSA). PSA progression-free survival (measured from the date of abiraterone start) and overall survival (death by any cause, measured from the date of mCRPC diagnosis or from the date of abiraterone start) were examined by the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients lost to follow-up were censored with the assumption of non-informative censoring. Point and interval estimates were calculated by province and by presenting stage (metastatic [M1] vs. non-metastatic [M0]). We speculated better survival for patients with longer PSAdt, and performed a statistical test (log-ranked) of survival difference across the 3 PSAdt groups. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, 187 patients were included in this study (Table 1). Notably, the median patient age at the time of abiraterone initiation was 73 years and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) was 2 to 3 in 30% of patients. Therefore, our non-clinical trial patient population was older and of poorer performance status than patients enrolled in the COU-AA-301 study (median age of 69, 10% had ECOG PS 2 and no ECOG PS 3 patients were enrolled). Median follow-up was 21 months from the date of abiraterone start, with 35% (66/187) alive at the time of last review and 5% (9/187) were lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at time of cancer diagnosis and treatment with abiraterone

| Overall | Alberta | BC | Ontario | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 187 | 77 | 51 | 59 |

| Age | ||||

| Median age at diagnosis | 65 | 62 | 66 | 67 |

| Median age at metastases | 70 | 68 | 69 | 72 |

| Median age at abiraterone start | 73 | 70 | 72 | 75 |

| Initial presentation | ||||

| M1 at cancer diagnosis (% within centre) | 73 (40%) | 30 (41%) | 25 (49%) | 18 (31%) |

| Gleason score | ||||

| ≤6 | 15 (8.0%)* | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 62 (33%) | 30 | 14 | 18 |

| 8 | 17 (9.0%) | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| 9–10 | 65 (34%) | 18 | 20 | 27 |

| Missing | 28 (15%) | 19 | 6 | 3 |

| Risk category | ||||

| Low | 10 (5.3%) | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Intermediate | 39 (21%) | 18 | 10 | 11 |

| High | 64 (35%) | 23 | 15 | 26 |

| Metastatic | 71 (38%) | 30 | 22 | 19 |

| Unknown | 3 (1.4%) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Extent of metastatic disease pre-abiraterone | ||||

| Bone only | 109 (58%) | 50 | 37 | 22 |

| Lymph nodes only | 33 (18%) | 12 | 5 | 16 |

| Bone and lymph nodes | 19 (10%) | 9 | 6 | 4 |

| Bone ± lymph nodes + at least one of liver or viscera | 3 (1.6%) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Viscera, lung ± lymph nodes | 4 (2.1%) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Missing | 19 (10%) | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| ECOG pre-abiraterone | ||||

| 0–1 | 113 (71%) | 60 | 20 | 33 |

| 2 | 39 (24%) | 13 | 11 | 15 |

| 3 | 8 (5%) | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| missing | 27 | 2 | 17 | 9 |

| Chemotherapy pre-abiraterone | ||||

| Received first line | 187 (100%) | 77 | 51 | 59 |

| Received second line | 47 (25%) | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Received third line | 7 (4%) | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| PSA pre-abiraterone | ||||

| Median PSA | 132 | 103 | 125 | 160 |

| Median positive PSA doubling time (n = 159) | 2.8 months | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| PSA doubling time not available | n = 6 | n = 4 | n = 1 | n = 1 |

| Proportion of cases with shorter doubling time 0–3 months | 75/181 (41%) | 31/73 (42%) | 26/50 (52%) | 27/58 (47%) |

| Proportion of cases with longer doubling time ≥3 months | 84/181 (46%) | 30/73 (41%) | 20/50 (40%) | 25/58 (43%) |

| Proportion of cases with negative doubling time (non-rising PSA) | 22/181 (12%) | 12/73 (16%) | 4/50 (8%) | 6/58 (10%) |

BC: British Columbia; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Variation in baseline characteristics across regions

This series included 77 patients from Alberta, 51 from BC and 59 from Ontario. Patients initiating abiraterone were younger in Alberta than those in BC or Ontario. Only 31% of the patients from Ontario had metastatic disease at diagnosis; whereas in BC this number was 49%. BC patients appeared to have a worse performance status, with 41% with a ECOG ≥2. In contrast, 21% of the Alberta population had an ECOG ≥2. The number of patients that received pre-abiraterone as second- or third-line chemotherapy was lowest in Alberta (21%), followed by Ontario (34%) and BC (35%).

Survival

Overall survival

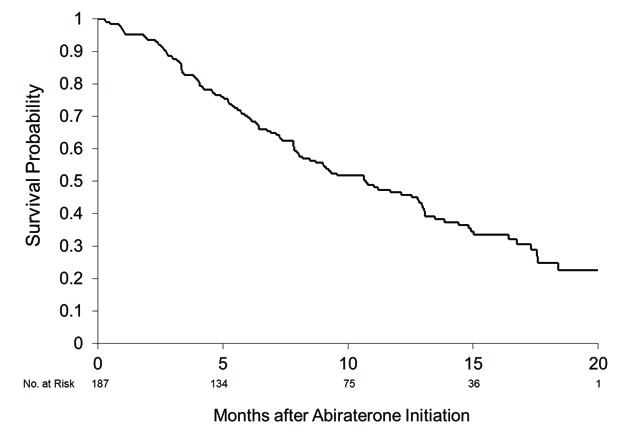

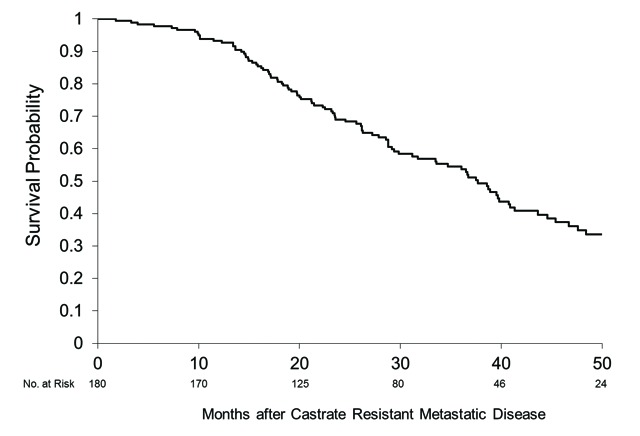

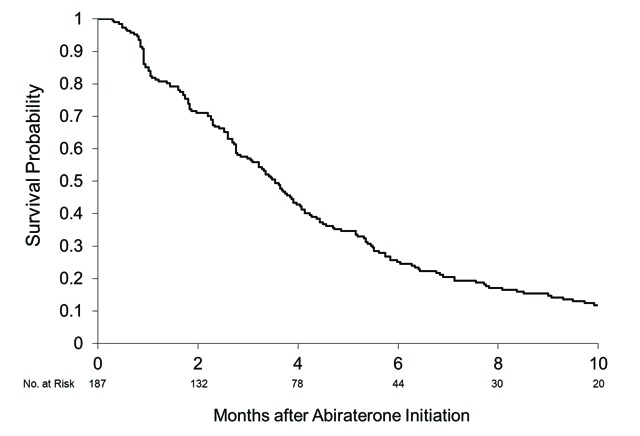

Median survival from the start of abiraterone was 11 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.0, 13) for this cohort (Fig. 1a). From the date of mCRPC diagnosis, the median survival was 38 months (95% CI 31, 41) with no significant variability among regions (Fig. 1b). For the whole group of study patients with mCRPC, the presenting stage of disease (M0 vs. M1) did not have a strong association with survival (M0 median 34 months, 95% CI 26, 41; M1 median 38 months, 95% CI 33, 58).

Fig 1a.

Overall survival. Median 11 months (95% confidence interval 8.0, 13) from abiraterone initiation.

Fig 1b.

Overall survival. Median 38 months (95% confidence interval 31, 41) from date of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

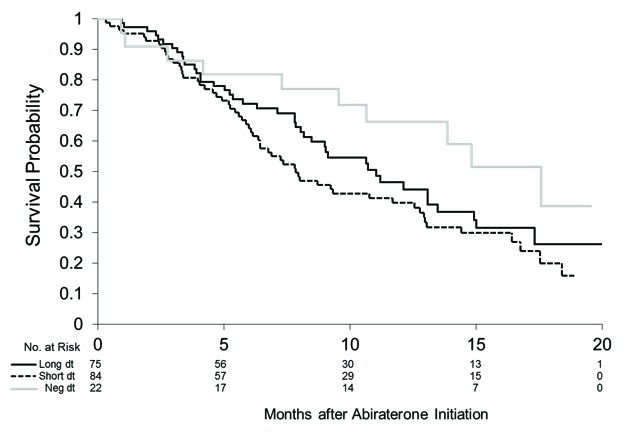

Overall survival by pre-abiraterone PSA doubling time

Patients with a negative PSAdt (non-rising PSA before abiraterone) had the longest median survival of 18 months (95% CI 9.6, upper limit not reached). In patients with longer versus shorter PSAdt (great or less than 3 months), we did not see substantial differences, with median survival of 11 months (95% CI 8.2, 13) and 7.9 months (95% CI 6.1, 12), respectively (Fig. 2). The test of equality across strata was not significant (log-rank p = 0.081).

Fig 2.

Overall survival stratified by pre-abiraterone prostate-specific antigen doubling time (PSAdt). PSAdt >3 months (long dt) median survival 11 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 8.2, 13); PSAdt <3 months (short dt) median survival 7.8 months (95% CI 6.1, 13); negative PSAdt (negdt) median survival 18 months (95% CI 9.6, upper limit not reached).

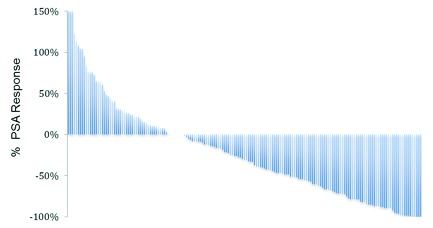

PSA response and disease progression

We found that 177 patients had at least 1 post-abiraterone PSA recorded. The median duration of abiraterone use was 4.5 months (range: 0.3–36 months). Figure 3 illustrates the best PSA response seen after the initiation of abiraterone. We found that 36% (64/177) of patients achieved a PSA response (>50% decline in PSA, Prostate Cancer Working Group 2). As for PSA progression, 74% (131/177) fit the criteria. The median PSA progression-free survival in this cohort was 3.5 months (95% CI 3.0, 4.0) (Fig. 4). A clinical follow-up was documented post-abiraterone in 148 patients, in whom 65% (96/148) had recognized clinical disease progression. Radiological investigations (a bone scan or CT scan) were done in 137 patients following the start of abiraterone; 40% (55/137) of them had documented radiological progression.

Fig 3.

Best prostate-specific antigen (PSA) response seen after initiation of abiraterone acetate. The first 3 patients have a PSA response rate outside the shown scale of, +2216%, +1233% and +1002%.

Fig. 4.

Prostate-specific antigen progression-free survival. Median 3.5 months (95% confidence interval 3.0, 4.0) from abiraterone initiation.

Adverse events

The most common adverse event overall was anemia, which occurred in 21% of patients (Table 2). Other common adverse reactions included peripheral edema (20%), fatigue (19%) and nausea (16%). Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were rarely observed in this group of patients.

Table 2.

Reported adverse events

| All grades, no. (%) | Grade 3 or 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 39 (21) | 1 (<1) |

| Peripheral edema | 37 (20) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 36 (19) | 1 (<1) |

| Nausea | 30 (16) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 23 (12) | 1 (<1) |

| Neutropenia | 22 (12) | 2 (1) |

| Hypertension | 21 (11) | 2 (1) |

| Hypokalemia | 19 (10) | 3 (2) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 13 (7) | 0 |

| ALT elevation | 12 (6) | 1 (<1) |

| AST elevation | 11 (6) | 0 |

| Constipation | 10 (5) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 9 (5) | 0 |

| Emesis | 9 (5) | 0 |

| Thrombocyopenia | 2 (1) | 0 |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

Discussion

To our knowledge this represents the largest documented series of men treated with abiraterone in a non-investigational setting. The PSA response rate of 36% compares favour-ably to the 29% rate seen in COU-AA-301 and underlines the biochemical effectiveness of this therapy. Other endpoints, including overall survival, PSA progression-free survival and time on abiraterone were somewhat inferior to clinical trials results, but still within reasonable expectations given the likely performance status inequity between our population and the COU-301 cohort. Our observed median overall survival of 11 months reflects the use of an active agent outside of a clinical trial setting, where patient characteristics differ and the timing of commencing abiraterone would have been more varied. In addition, supplementary therapies may have been instituted which could have led to a delay in abiraterone start. PSAdt prior to abiraterone did not strongly affect survival, though patients with non-rising PSA tended to live longer. However, this observation is from an exploratory analysis of our limited retrospective data. The rate and severity of documented adverse events were congruent with those seen in studies, although the certainty with which this can be ascertained in a retrospective study is low.

As new systemic agents are demonstrating efficacies in improving survival outcomes in mCRPC,17–21 a renewed understanding of the natural (treated) history of this condition is needed to help evaluate expected disease behaviour and treatment outcomes. Using the diagnosis of mCRPC as a starting point seems clinically reasonable, but estimates of survival from diagnosis of mCRPC in contemporary prostate cancer treatment cohorts are difficult to ascertain in the literature. Although the TAX-327 study with docetaxel reported a median survival of 19 months for mCRPC,22 that figure is likely to be an underestimation of survival from the date of mCRPC. We observed a 38-month median overall survival after diagnosis of mCRPC among abiraterone-treated patients. This is similar to the 32.6-month median overall survival observed in patients on the COU-AA-301 study when calculated from the time of first-line chemotherapy initiation. While our data represent the best survival estimate based on current prostate cancer management in Canada, it is subject to variability and clinical judgment as the point of diagnosis of mCRPC is highly dependent upon the frequency and timing of investigations.

Our study carries the inherent limitations of retrospective chart reviews, as the rigor of diagnoses and outcome documentation were not protocol-prescribed, and the reliability of our estimates are challenged by missing data, ascertainment bias and attribution bias. Only patients placed on abiraterone were included, who were well enough to have received at least first-line docetaxel, and the resultant survival estimates might not be representative of all men diagnosed with mCRPC. As this study was conducted shortly after the completion of the registration trial and during a period of special access, there could be factors that affected the case-mix of patients included in this study, with resultant baseline characteristics and outcomes that could be different from patients entered on clinical trials. The use of therapies in addition to systemic chemotherapy was not collected among the patient characteristics and may have altered the survival estimates. We obtained clinical data primarily from cancer centres through which abiraterone was studied in clinical trials, which may limit the generalizability of our estimates to other clinical practices. We also censored patients who were lost to follow-up (where vital status was unknown when patients failed to return to cancer centre for follow-up), and the non-informative censoring assumption for survival estimates might not be valid given patients generally had advanced disease.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate the initial non-clinical trial experience with abiraterone in men with mCRPC who have previously received docetaxel. Abiraterone has recently also demonstrated its utility in the chemo-naïve mCRPC population,23 and several other agents have recently demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with mCRPC.17–21 The future challenge will be determining the optimal patient selection, treatment timing and sequencing of these agents that are now in our therapeutic armamentarium.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Clayton, Dr. Wu, Dr. Heng, Dr. North, Dr. Emmenegger, Dr. Hotte, Dr. Chi, Dr. Zielinski, Dr. Al-Shamsi, Dr. Chen and Dr. Eigl all declare no competing financial or personal interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Isaacs JT. Role of androgens in prostatic cancer. Vitamins & Hormones. 1994;49:433–502. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(08)61152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: Directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8253–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutt SS, Gao AC. Molecular mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer progression. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1403–13. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter GA, Barrie SE, Jarman M, et al. Novel steroidal inhibitors of human cytochrome P45017 alpha (17 alpha-hydroxylase-C17,20-lyase): Potential agents for the treatment of prostatic cancer. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2463–71. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attard G, Belldegrun AS, de Bono JS. Selective blockade of androgenic steroid synthesis by novel lyase inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy for treating metastatic prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005;96:1241–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrie SE, Haynes BP, Potter GA, et al. Biochemistry and pharmacokinetics of potent non-steroidal cytochrome P450(17alpha) inhibitors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;60:347–51. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(96)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang JE, Olmos D, de Bono JS. CYP17 blockade by abiraterone: Further evidence for frequent continued hormone-dependence in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:671–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attard G, Reid AH, A’Hern R, et al. Selective inhibition of CYP17 with abiraterone acetate is highly active in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3742–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attard G, Reid AH, de Bono JS. Abiraterone acetate is well tolerated without concomitant use of corticosteroids. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e560–1. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4563–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danila DC, Morris MJ, de Bono JS, et al. Phase II multicenter study of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy in patients with docetaxel-treated castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1496–501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid AH, Attard G, Danila DC, et al. Significant and sustained antitumor activity in post-docetaxel, castration-resistant prostate cancer with the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetate. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1489–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fong L, et al. Phase I clinical trial of the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetate demonstrating clinical activity in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer who received prior ketoconazole therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1481–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Basch E, et al. End points and outcomes in castration-resistant prostate cancer: From clinical trials to clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3695–704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernandez Toriz N, et al. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:745–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:138–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]