Abstract

Background

Impaired placentation can cause some of the most important obstetrical complications such as pre‐eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction and has been linked to increased fetal morbidity and mortality. The failure to undergo physiological trophoblastic vascular changes is reflected by the high impedance to the blood flow at the level of the uterine arteries. Doppler ultrasound study of utero‐placental blood vessels, using waveform indices or notching, may help to identify the 'at‐risk' women in the first and second trimester of pregnancy, such that interventions might be used to reduce maternal and fetal morbidity and/or mortality.

Objectives

To assess the effects on pregnancy outcome, and obstetric practice, of routine utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound in first and second trimester of pregnancy in pregnant women at high and low risk of hypertensive complications.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (June 2010) and the reference lists of identified studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of Doppler ultrasound for the investigation of utero‐placental vessel waveforms in first and second trimester compared with no Doppler ultrasound. We have excluded studies where uterine vessels have been assessed together with fetal and umbilical vessels.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and carried out data extraction. We checked data entry.

Main results

We found two studies involving 4993 participants. The methodological quality of the trials was good. Both studies included women at low risk for hypertensive disorders, with Doppler ultrasound of the uterine arteries performed in the second trimester of pregnancy. In both studies, pathological finding of uterine arteries was followed by low‐dose aspirin administration.

We identified no difference in short‐term maternal and fetal clinical outcomes.

We identified no randomised studies assessing the utero‐placental vessels in the first trimester or in women at high risk for hypertensive disorders.

Authors' conclusions

Present evidence failed to show any benefit to either the baby or the mother when utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound was used in the second trimester of pregnancy in women at low risk for hypertensive disorders. Nevertheless, this evidence cannot be considered conclusive with only two studies included. There were no randomised studies in the first trimester, or in women at high risk. More research is needed to investigate whether the use of utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound may improve pregnancy outcome.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Pregnancy Outcome; Aspirin; Aspirin/administration & dosage; Fibrinolytic Agents; Fibrinolytic Agents/administration & dosage; Placenta; Placenta/diagnostic imaging; Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors; Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors/administration & dosage; Pregnancy Trimester, Second; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Regional Blood Flow; Ultrasonography, Prenatal; Uterine Artery; Uterine Artery/diagnostic imaging

Doppler ultrasound of blood vessels in the placenta and uterus of pregnant women as a way of improving outcome for babies and their mothers

One of the main aims of routine antenatal care is to identify mothers or babies at risk of adverse outcomes. Doppler ultrasound uses sound waves to detect the movement of blood in blood vessels. It is used in pregnancy to study blood circulation in the baby, the mother's uterus and the placenta. If abnormal blood circulation is identified, then it is possible that medical interventions might improve outcomes. We set out to assess the value of using Doppler ultrasound of the mother's uterus or placenta (utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound) as a screening tool. Other reviews have looked at the use of Doppler ultrasound on the babies' vessels (fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound). We also choose to look at women with low‐risk and high‐risk pregnancies, and in their first or second trimesters. This screening offers a potential for benefit, but also a possibility of unnecessary interventions and adverse effects. The review of randomised controlled trials of routine Doppler ultrasound of the uterus or placenta identified two studies involving 4993 women. All the women were in the second trimester of pregnancy and at low risk for hypertensive disorders. The studies were of good quality but small in size. We identified no improvements for the baby or the mother. However, more data would be needed to show whether maternal Doppler is effective, or not, for improving outcomes. We did not find any studies in the first trimester of pregnancy or in women at risk of high blood pressure disorders. More research is needed on this important aspect of care.

Background

Description of the condition

The blood supply to the uterus is provided mainly by the uterine arteries and also by the ovarian arteries. Once the arterial vessels reach myometrium, they divide into arcuate arteries, then into the radial arteries which ultimately branch into the spiral arteries. During the first and second trimester of pregnancy, trophoblast invades the spiral arteries ‐ a process that is fundamental for normal placentation. The most important change, but not the only one, is replacement of the muscular and elastic arterial layer by collagen (Espinoza 2006). As the trophoblastic invasion continues during the first half of pregnancy, the resistance to the blood flow in the uterine arteries progressively decreases.

The failure to undergo these physiologic vascular changes has been associated not just with pre‐eclampsia (Brosens 1972; Khong 1991; Sibai 2005; Von Dadelszen 2002) and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (Bernstein 2000; Fisk 2001; Khong 1991), but also with other maternal diseases such as diabetes mellitus (Khong 1991), lupus erythematosus (Nayar 1996), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (Levy 1998) and others (Barker 2004).

Description of the intervention

Doppler ultrasound velocimetry uses the Doppler principle to analyse the properties of the blood flow in a vessel of interest. This physical principle explains the observed change in wave frequency relative to the speed of a moving object. In case of Doppler ultrasound, the emitted ultrasound frequency will change when ultrasound beam encounters moving blood. The principle can be applied using different ultrasound modalities such as continuous‐wave Doppler, pulsed‐wave Doppler, colour and power Doppler wave (Burns 1993; Chen 1996; Owen 2001). While colour and power Doppler provide visualisation of the blood flow and its direction, pulsed Doppler allows reproducible measurements of the blood velocities. The measurements obtained will reflect, in any vessel studied, the cardiac contraction force, density of the blood, vessel wall elasticity, but more importantly peripheral and downstream resistance (Owen 2001).

Physiological process of the trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries takes place between six and 24 weeks of gestation in normal pregnancies. The blood flow from the uterine arteries to the placenta will progressively increase during that time. By studying the uterine arteries with pulse Doppler ultrasound, it is possible to assess the progressive decrease in resistance to blood flow. The rationale of using the Doppler velocimetry of uterine arteries to assess the failure of the placentation is related to fact that the lack of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries will cause high resistance to blood flow within uterus and subsequently in uterine arteries.

At least 15 different uterine artery Doppler indices have been used to quantify the uterine arteries perfusion and predict pre‐eclampsia and IUGR (Cnossen 2008). The most commonly used indices are the pulsatility and resistant index (PI and RI) which showed the highest predictive value (Cnossen 2008). The qualitative description focuses on the presence or absence of early diastolic notch that could be either unilateral or bilateral.

The abnormal findings in uterine arteries are usually defined as PI or RI above the 95 percentile at a given gestational age (Albaiges 2000; Bower 1993) and the presence of notching (a qualitative assessment of flow velocity waveform ‐ Harrington 1996). Numerous studies have linked the high impedance and bilateral notching in uterine arteries to early onset pre‐eclampsia, IUGR and higher perinatal mortality (Aardema 2001; Albaiges 2000; Bower 1993; Harrington 1996; Olofsson 1993).

Reported sensitivity and detection rate of the uterine artery Doppler to predict pre‐eclampsia in unselected population range from 50% to 60%, meaning that only half of the women that subsequently develop the disease will be correctly identified by the increased resistance in uterine arteries. On the other hand the reported specificity is around 95%, which means that most women with normal uterine artery Doppler will not develop pre‐eclampsia. The performance of uterine artery Doppler as a screening test is higher when pre‐eclampsia is divided in severe or early onset and mild or late onset pre‐eclampsia. In that case, the sensitivity rises from 80% to 85% for severe pre‐eclampsia, requiring delivery before 34 weeks (Papageorghiou 2001; Yu 2005) and 90% for severe pre‐eclampsia indicating delivery before 32 weeks (Papageorghiou 2001).

More recently, the interest for uterine artery measurements has moved from the second to the first trimester of pregnancy (13+6 to 11+0 weeks of gestation). The rationale of measuring the uterine artery Doppler in the first trimester is the possibility to intervene with some prophylactic therapy such as antithrombotic drugs while the trophoblastic invasion is still ongoing. The uterine artery Doppler has been found to be less predictive when compared with the second trimester examination. Reported detection rate for uterine artery Doppler alone in the first trimester ranged from 40% to 67% for early onset pre‐eclampsia and 15% to 20% for late onset pre‐eclampsia (Martin 2001; Parra 2005). In the attempt to improve the performance of the uterine artery as a screening test, new algorithms that take into account the maternal characteristics, history and/or biochemical markers have been proposed. In fact, uterine artery Doppler in the first and second trimester, in combination with several biochemical markers, has been extensively tested as a predictive test for pre‐eclampsia and IUGR, and the first results are encouraging (Nicolaides 2006; Parra 2005; Plasencia 2007; Spencer 2007; Zhong 2010). Nevertheless, at present the literature comprises several large uncontrolled cohort studies and as yet there are no randomised studies in this field, and the cost‐effectiveness remains to be proven.

How the intervention might work

It is hoped that early detection of abnormal placental vasculature, before maternal and fetal complications develop, would allow preventative interventions and more targeted maternal and fetal surveillance. Low‐dose aspirin is an example of a preventative intervention that could be targeted to those with abnormal utero‐placental Doppler (Askie 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

Doppler ultrasound has become an integral part of obstetric care (Alfirevic 2010a) and more clinicians are being trained to use it. Using a non‐invasive and relatively easy screening tool such as Doppler ultrasound of the uterine arteries to predict pre‐eclampsia and IUGR is undoubtedly appealing. Early recognition of pre‐eclampsia and IUGR could improve maternal and perinatal outcome by administration antiplatelet therapy, appropriate antihypertensive therapy, medication for fetal lung maturation and early delivery. Nevertheless, labelling woman as 'at risk' could cause significant anxiety and increase the number of unnecessary examinations and interventions (blood tests, hospital admission and possibly early delivery).

This review will complement two other Cochrane reviews that focus on the fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high‐risk populations (Alfirevic 2010a), and in low‐risk populations (Alfirevic 2010b).

Objectives

To assess whether the use of utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound (uterine arteries and placental vessels) improves the outcome of low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised trials and quasi‐randomised studies comparing utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound (uterine, arcuate, radial and spiral arteries) in low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies. We planned to perform sensitivity analysis by trial quality. We included study abstracts. We have considered cluster trials, though we found none, but we did not think cross‐over trials would be suitable for this topic.

Types of participants

Pregnant women, considered to be either low‐ or high‐risk, who had utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound performed at first or second trimester of pregnancy. We planned to include twin pregnancies and to perform subgroup analysis for that population but there were insufficient data.

Types of interventions

Doppler ultrasound of the utero‐placental circulation (uterine, arcuate, radial and spiral arteries) in pregnancies at low and high risk. We did not include studies that considered the combination of utero‐placental Doppler and fetal or umbilical Doppler in this review, but did include them in fetal and umbilical Doppler reviews (Alfirevic 2010a; Alfirevic 2010b).

Comparisons

Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels versus no Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels (including comparisons of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels revealed versus Doppler of utero‐placental vessels concealed) in first trimester of pregnancy.

Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels versus no Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels (including comparisons of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels revealed versus Doppler of utero‐placental vessels concealed) in second trimester of pregnancy.

Comparison of different forms of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels versus other types of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels in first trimester of pregnancy.

Comparison of different forms of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels versus other types of Doppler ultrasound of utero‐placental vessels in second trimester of pregnancy.

Comparison of different methods of Doppler ultrasound measurements of utero‐placental vessels in first trimester of pregnancy.

Comparison of different methods of Doppler ultrasound measurements of utero‐placental vessels in second trimester of pregnancy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Any perinatal death after randomisation.

Hypertensive disorders (pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelets, chronic hypertension).

Secondary outcomes

Stillbirth (as defined by trialists).

Neonatal death (as defined by trialists).

Any potentially preventable perinatal death.*

Serious neonatal morbidity ‐ composite outcome including hypoxic Ischaemic encephalopathy, intraventricular haemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis.

IUGR (as defined by the trialists).

Fetal distress (as defined by the study authors).

Neonatal resuscitation required (as defined by trialists).

Infant requiring intubation/ventilation.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome.

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Neonatal admission to special care or intensive care unit, or both.

-

Preterm birth (birth before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy):

spontaneous preterm birth;

iatrogenic preterm birth.

Caesarean section (elective and emergency).

Caesarean section ‐ elective.

Caesarean section ‐ emergency.

Serious maternal morbidity and mortality (composite outcome with death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy).

Mother's admission to special care or intensive care unit, or both.

Gestational age at birth.

Infant birthweight.

Length of infant hospital stay.

Length of maternal hospital stay.

* Perinatal death excluding chromosomal abnormalities, termination of pregnancies, birth before fetal viability (as defined by trialists) and fetal death before use of the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (June 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists at the end of papers for further studies.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

The methodology for data collection and analysis was based on the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (TS, GG) independently assessed for inclusion all potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third author (ZA).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors (TS, GG) extracted the data using the agreed form, with additional help at times (Stephania Livio). We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third author (ZA). We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) (TS) and checked for accuracy (GG).

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (TS, GG) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving the third author (ZA).

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random‐number generator);

inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we have re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

adequate;

inadequate:

unclear.

We were to discuss whether missing data greater than 20% might impact on outcomes, acknowledging that with long‐term follow up, complete data are difficult to attain. However, none of the included studies had greater than 20% missing data.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We would have included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials, had we identified any. We would have make adjustments using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources had been used, we would have reported this and conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we would have planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would have considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit were considered to be unlikely.

We would also have acknowledged any heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a separate meta‐analysis.

Cross‐over trials

We considered cross‐over designs inappropriate for this research question.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We would have explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial is the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing. We would have excluded data on outcomes where there was greater than 20% missing data on short term outcomes had we encountered such data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T² (tau‐squared), I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T² was greater than zero and either I² was greater than 30% or there was a low P‐value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Where we found heterogeneity and random‐effects was used, we have reported the average risk ratio, or average mean difference or average standard mean difference.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there had been 10 or more studies in a meta‐analysis we would have investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We would have assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually, and use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes, we would have used the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we would have used the tests proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry had been detected by any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we would have performed exploratory analyses to investigate it. We would seek statistical help if necessary.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we would have used random‐effects analysis to produce an overall summary, if this was considered clinically meaningful. If an average treatment effect across trials was not clinically meaningful, we would not have combined heterogeneous trials. If we used random‐effects analyses, the results have been presented as the average treatment effect and its 95% confidence interval, the 95% prediction interval for the underlying treatment effect, and the estimates of T² and I² (Higgins 2009).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses on all outcomes:

measurements in high‐risk population, low‐risk population and unselected population;

in singleton and twin pregnancies.

However, there were insufficient data to perform any subgroup analyses. We had also planned to pull together the three subgroups for the overall estimation.

For fixed‐effect meta‐analyses, we had planned to conduct the planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001. For random‐effects meta‐analyses, we would have assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We would have performed sensitivity analysis on the primary outcomes based on trial quality, separating high‐quality trials from trials of lower quality. 'High quality' would, for the purposes of this sensitivity analysis, have been defined as a trial having adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search was designed to identify all randomised controlled trials on assessing the effectiveness of Doppler ultrasound, whether using fetal‐umbilical or utero‐placental (maternal) vessels. We identified 58 publications from 34 studies, of which we have included two in this review, involving data on 4993 women and 5009 neonates (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003).

We have excluded 30 studies, mainly because they assessed both fetal and umbilical vessels. For further details of trial characteristics, please refer to the tables of Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies. Two studies are awaiting classification as we are trying to locate the authors but they both appear to remain unpublished (Ellwood 1997; Snaith 2006). The large number of excluded studies reflects the fact that the search was designed for all Doppler ultrasound studies, including both utero‐placental vessels and fetal‐umbilical vessels. Most of the studies identified focused on fetal‐umbilical vessels and are included by two other Doppler ultrasound reviews (Alfirevic 2010a; Alfirevic 2010b).

Included studies

Included studies compared uterine artery Doppler assessments in the experimental group with no uterine artery Doppler performed in the control groups (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003). In both studies, low‐dose aspirin was administrated in cases of abnormal uterine artery Doppler findings (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003).

Both studies were of assessments of women in the second trimester, around time for fetal anomaly scan, and both included women at low risk for hypertensive disorders (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003).

One of the studies involved a mixture of singleton and twin pregnancies (Subtil 2003), while the other did not state specifically if it included multiple pregnancies, although reported numbers suggest only singleton pregnancies were included (Goffinet 2001).

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies, mostly because they assessed umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. SeeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

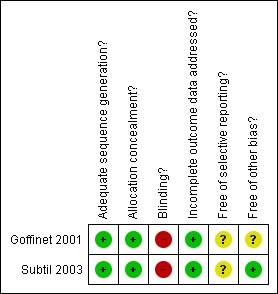

The quality of the three included studies was reasonable, although blinding was not possible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Both studies had adequate sequence generation and concealment allocation (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003).

Blinding

Blinding women and/or staff in these trials was not generally feasible. Some outcomes like induction of labour and caesarean section may be influenced by the knowledge of Doppler results, but it may be possible to avoid bias in neonatal assessment. Unfortunately, the information on the attempts to protect against biased assessment was not available.

Incomplete outcome data

The two studies had adequate outcome data (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003). One of the studies awaiting classification (Ellwood 1997) aimed to recruit 524 women, but undertook the analysis after 364 women had entered the trial, though data were available on only 164. As this was not a block randomisation, we cannot be sure these are randomised groups being compared so we are awaiting the full study to be reported before including any data.

Selective reporting

We assessed both included studies as unclear because we did not assess the trial protocols.

Other potential sources of bias

One study appeared free of other biases (Subtil 2003), whilst for the other this was unclear (Goffinet 2001).

Sensitivity analyses

For sensitivity analyses by quality of studies, we have used both adequate labelled sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment as essential criteria for high quality. Two of three studies met these criteria (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003), seeFigure 1. However, we feel there are insufficient data to perform a sensitivity analysis by quality.

Effects of interventions

1. Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 1st trimester (no studies)

We found no studies assessing uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in the first trimester.

2. Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester (two studies, 4993 women)

We identified two studies assessing uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in the second trimester in women at low risk for hypertensive disorders (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003). Both were full publications (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003). Overall the quality of the included studies was good for the main criteria of randomisation, allocation concealment and low percentage of missing data (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003), seeFigure 1.

Primary outcomes

It is important to emphasise that this review remains underpowered to detect clinically important differences in serious maternal and neonatal morbidity.

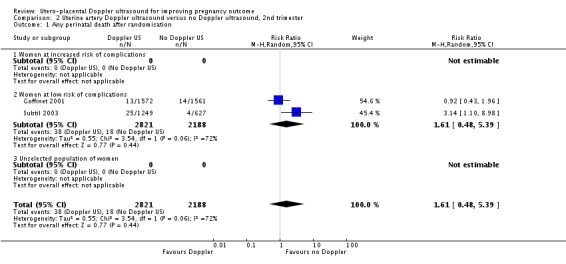

Any perinatal death after randomisation

The difference in perinatal mortality between two groups was not statistically significant (average risk ratio (RR) 1.61, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.48 to 5.39, two studies, 5009 babies, Analysis 2.1). The heterogeneity was high (T² = 0.55, Chi² P = 0.06, I² = 72%) and therefore, we used the random‐effects model for the analysis. We were unable to calculate the prediction interval as there were only two studies.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 1 Any perinatal death after randomisation.

Subtil 2003 reported significantly fewer deaths in the control group (RR 3.14, 95% CI 1.10 to 8.98). This difference was contributed to by 17 abortions or medically indicated terminations of pregnancy in the 1253 women in the Doppler group (1.4%) compared with three out of 617 in the control group (0.5%). In addition, 78 of the 1253 women randomised to Doppler group (6.2%) did not receive their allocated treatment. The reason was termination of pregnancies for medical or social reasons in 15 women and perinatal deaths in two babies, but the reasons for the remainder of the women not receiving the Doppler ultrasound were not documented. The analysis for 'Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation' which excluded all terminations and perinatal deaths for chromosomal abnormalities is more clinically relevant and showed no detectable difference (see below).

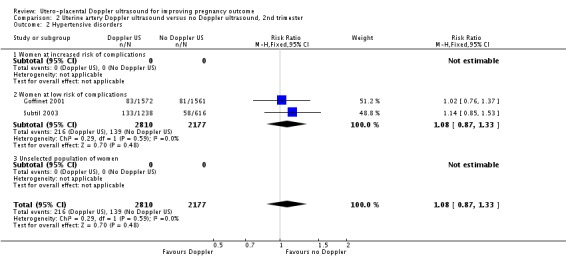

Hypertensive disorders

There was no difference identified in maternal hypertensive disorders between two groups (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.33, two studies, 4987 women, Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 2 Hypertensive disorders.

Secondary outcomes

We found no significant difference in the pooled estimate of the intervention effect for the range of secondary outcomes with low heterogeneity where a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis was used. Most pre‐specified secondary outcomes had high heterogeneity and therefore an intervention effect estimate across studies was calculated using random‐effects.

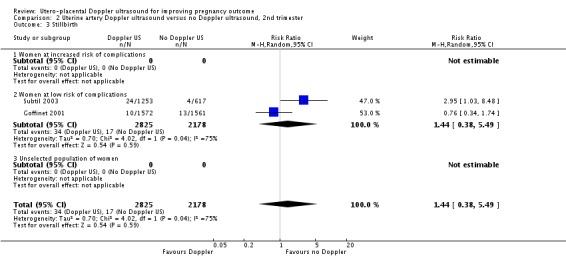

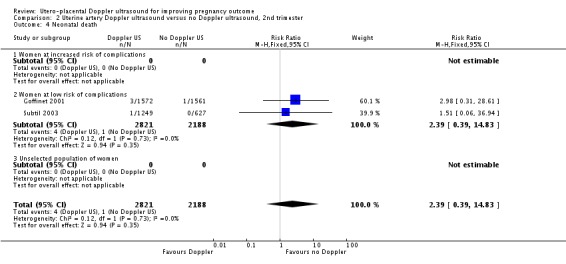

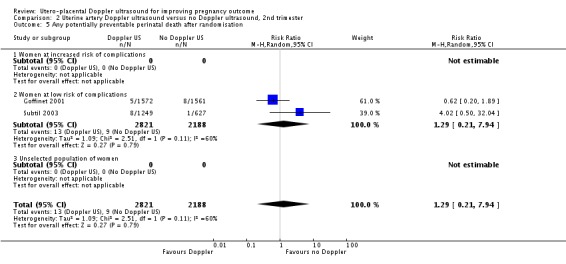

There was no significant difference in stillbirths (average RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.38 to 5.49, two studies, 5003 babies, random‐effects T² = 0.70, Chi² P = 0.04, I² = 75%, Analysis 2.3), or for neonatal deaths (RR 2.39, 95% CI 0.39 to 14.83, two studies, 5009 babies, Analysis 2.4). Similarly for 'Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation' (average RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.21 to 7.94, two studies, 5009 babies, random‐effects T² 1.09, Chi² P = 0.11, I² = 60%, Analysis 2.5). These data should be interpreted cautiously because the numbers are small and heterogeneity is high.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 3 Stillbirth.

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 4 Neonatal death.

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 5 Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation.

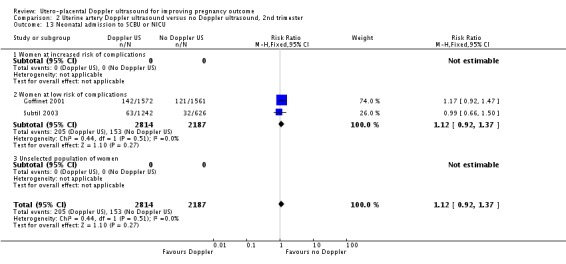

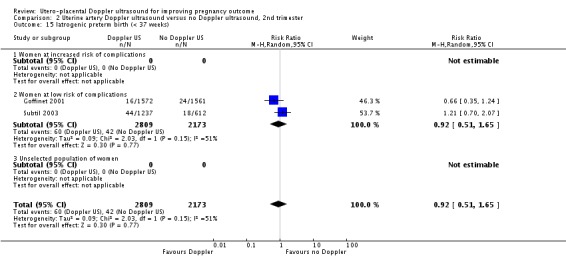

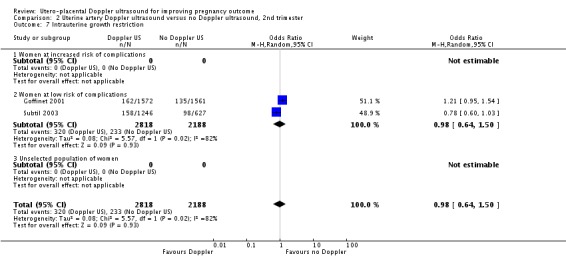

The data for neonatal admission to special care baby unit (SCBU) or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.37, two studies, 5001 babies, Analysis 2.13) and iatrogenic preterm birth (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.65, two studies, 4982 women, random‐effects T² = 0.09, Chi² P = 0.15, I² = 51%, Analysis 2.15) are consistent with the overall picture showing no significant difference in two groups. The meta‐analysis also failed to identify any difference in IUGR (average RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.50, two studies, 5006 babies, random‐effects T² = 0.08, Chi² P = 0.02, I² = 82%, Analysis 2.7), although there was high heterogeneity, so it is also possible that there are different effects in the different studies, for unknown reasons.

Analysis 2.13.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 13 Neonatal admission to SCBU or NICU.

Analysis 2.15.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 15 Iatrogenic preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 7 Intrauterine growth restriction.

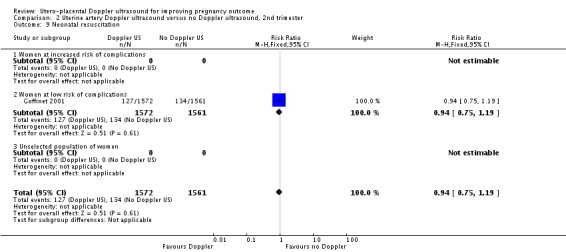

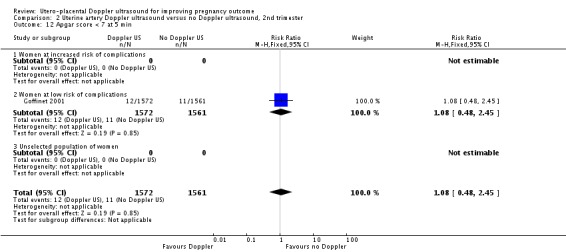

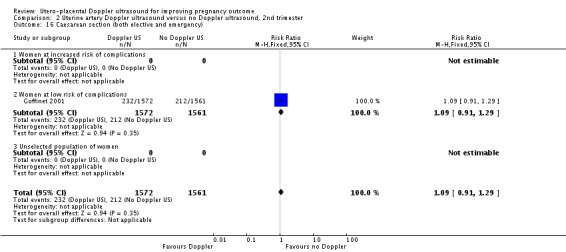

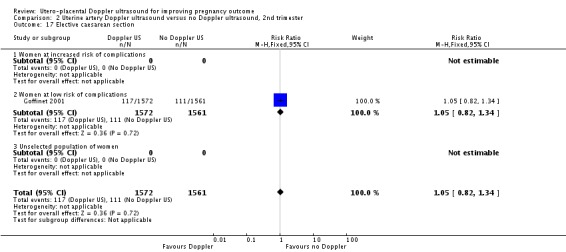

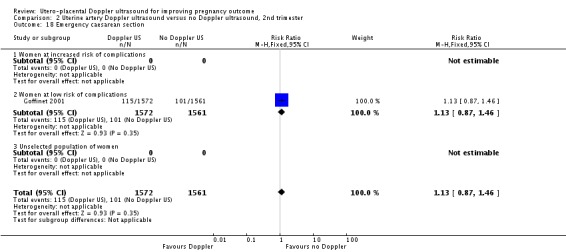

Only one study assessed neonatal resuscitation (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.19, 3133 babies, Analysis 2.9), Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.45, 3133 babies) (Analysis 2.12) and caesarean sections (emergency plus elective) (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.29, 3133 women) (Analysis 2.16). We found no significant difference for any of these outcomes.

Analysis 2.9.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 9 Neonatal resuscitation.

Analysis 2.12.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 12 Apgar score < 7 at 5 min.

Analysis 2.16.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 16 Caesarean section (both elective and emergency).

None of the studies assessed the following outcomes: 'Serious neonatal morbidity', 'Fetal distress', 'Infant requiring intubation/ventilation', 'Infant respiratory distress syndrome', 'Spontaneous preterm birth', 'Serious maternal morbidity' and 'Maternal admission to special care'.

Non‐prespecified outcomes

We did not include any non‐prespecified outcomes.

Sensitivity analysis

Since we assessed both studies as adequate for sequence generation and allocation concealment (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003), we did not undertake sensitivity analysis by quality.

Discussion

Increasing interest in maternal Doppler in first and second trimester led us to undertake this review which completes a trio of reviews on Doppler ultrasound in pregnancy. The other two reviews focused on the use of fetal‐umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high risk (Alfirevic 2010a) and normal pregnancies (Alfirevic 2010a).

Despite wide use of uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in clinical practice, we identified just two randomised studies assessing this intervention in the second trimester of pregnancy involving 4993 women at low risk of hypertensive disorders (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003) and found no difference in any perinatal or maternal outcomes. Considering that both included studies involved women at low risk for hypertensive disorders, this could possibly explain the lack of benefit identified for uterine artery Doppler application as incidence of adverse outcomes was low (any potentially preventable perinatal death 0.4%, hypertensive disorders 7%, IUGR 11%).

In both studies (Goffinet 2001; Subtil 2003), the finding of pathological uterine artery Doppler was followed by low‐dose aspirin administration. When interpreting these data, it is important to highlight the presence of heterogeneity and small number of participants that makes our review underpowered rare events such as perinatal mortality and severe maternal outcomes.

Suprisingly, lower perinatal mortality was observed in the control group in one study (Subtil 2003: risk ratio 3.14, 95% confidence interval 1.10 to 8.98, Analysis 2.1). This could be possibly explained by a higher percentage of women with termination of pregnancy or perinatal death that occurred in the Doppler group by chance before the Doppler ultrasound was carried out.

Summary of main results

We found no differences in any of the perinatal and maternal outcomes when comparing uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in the second trimester in women at low risk for hypertensive disorders versus controls. There were no studies of women in the first trimester.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There were only two studies involving 4993 women, and clearly the meta‐analysis remains underpowered to show clinically important differences in primary outcomes. The identification of an abnormal results also needs an effective intervention before the screening test can be said to be helpful.

Quality of the evidence

The studies were of reasonable quality, but involved insufficient numbers of women overall to assess the rare outcomes of perinatal death and morbidity.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to minimise bias in a number of ways; two review authors assessed eligibility for inclusion, carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. Each worked independently. Nevertheless, the process of assessing risk of bias, for example, is not an exact science and includes many personal judgements.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Findings from this meta‐analysis are not in disagreement with other non‐randomised studies that examined the role of uterine arteries in low‐risk population in second trimester of pregnancy.

Authors' conclusions

Data in this meta‐analysis failed to show that the use of uterine artery Doppler in second trimester in low‐risk population for hypertensive disorders provides benefit for the baby or mother.

Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound is widely used in high‐risk pregnancy and progressively its use is spreading into the first trimester, although there are no randomised studies to show clear benefit in this population of women. Futher research is needed to prove the appropriateness of this clinical practice application.

As previously highlighted, larger studies are needed with enough power to show clearly the presence or absence of benefit when using uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in second trimester in low‐risk women for hypertensive disorders. Moreover, randomised controlled trials of uterine artery Doppler in the first and second trimester, in combination with woman's history and/or biochemical serum markers, are needed to evaluate the benefit of combined models.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank Stefania Livio, who helped with some of the data extractions, and Eugenie Ong, who translated the de Rochambeau 1992 study.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 1st trimester

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Any perinatal death after randomisation | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Hypertensive disorders | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Stillbirth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Serious neonatal morbidity ‐ composite | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Intrauterine growth restriction | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Fetal distress | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Neonatal resuscitation | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Infant requiring intubation/ventilation | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Infant respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Apgar score < 7 at 5 min | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Neonatal admission to SCBU or NICU | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Spontaneous preterm birth (< 37 weeks) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Iatrogenic preterm birth (< 37 weeks) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Caesarean section (both elective and emergency) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Elective caesarean section | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18 Emergency caesarean section | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19 Serious maternal morbidity and mortality | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20 Mothers admission to special care or intensive care unit | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21 Gestational age at birth | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 22 Infant birthweight | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 22.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 22.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 22.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23 Length of infant hospital stay | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24 Length of maternal hospital stay | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2.

Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Any perinatal death after randomisation | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.48, 5.39] |

| 1.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.48, 5.39] |

| 1.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Hypertensive disorders | 2 | 4987 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.87, 1.33] |

| 2.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 4987 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.87, 1.33] |

| 2.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Stillbirth | 2 | 5003 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.44 [0.38, 5.49] |

| 3.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5003 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.44 [0.38, 5.49] |

| 3.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Neonatal death | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.39 [0.39, 14.83] |

| 4.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.39 [0.39, 14.83] |

| 4.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.21, 7.94] |

| 5.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5009 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.21, 7.94] |

| 5.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Serious neonatal morbidity ‐ composite | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Intrauterine growth restriction | 2 | 5006 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.64, 1.50] |

| 7.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5006 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.64, 1.50] |

| 7.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Fetal distress | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Neonatal resuscitation | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.75, 1.19] |

| 9.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.75, 1.19] |

| 9.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Infant requiring intubation/ventilation | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Infant respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Apgar score < 7 at 5 min | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.48, 2.45] |

| 12.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.48, 2.45] |

| 12.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Neonatal admission to SCBU or NICU | 2 | 5001 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.92, 1.37] |

| 13.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 5001 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.92, 1.37] |

| 13.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Spontaneous preterm birth (< 37 weeks) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Iatrogenic preterm birth (< 37 weeks) | 2 | 4982 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.65] |

| 15.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.2 Women at low risk of complications | 2 | 4982 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.65] |

| 15.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Caesarean section (both elective and emergency) | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.91, 1.29] |

| 16.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.91, 1.29] |

| 16.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Elective caesarean section | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.82, 1.34] |

| 17.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.82, 1.34] |

| 17.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18 Emergency caesarean section | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.87, 1.46] |

| 18.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.87, 1.46] |

| 18.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19 Serious maternal morbidity and mortality | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20 Mothers admission to special care or intensive care unit | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

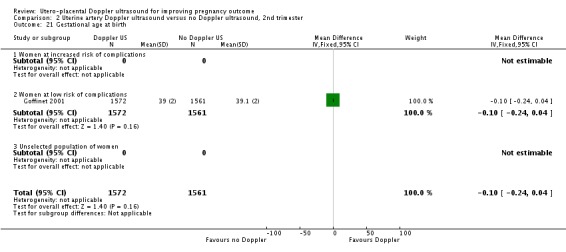

| 21 Gestational age at birth | 1 | 3133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.24, 0.04] |

| 21.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 21.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.24, 0.04] |

| 21.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

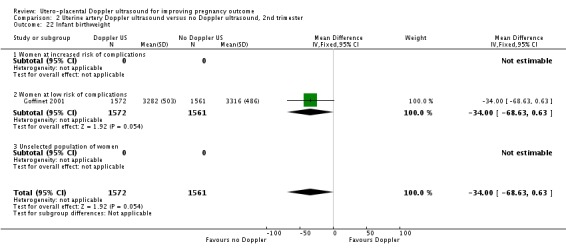

| 22 Infant birthweight | 1 | 3133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐34.0 [‐68.63, 0.63] |

| 22.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 22.2 Women at low risk of complications | 1 | 3133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐34.0 [‐68.63, 0.63] |

| 22.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23 Length of infant hospital stay | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24 Length of maternal hospital stay | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.1 Women at increased risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.2 Women at low risk of complications | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 24.3 Unselected population of women | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 2.17.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 17 Elective caesarean section.

Analysis 2.18.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 18 Emergency caesarean section.

Analysis 2.21.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 21 Gestational age at birth.

Analysis 2.22.

Comparison 2 Uterine artery Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, 2nd trimester, Outcome 22 Infant birthweight.

Differences between protocol and review

There were no differences between the protocol and review.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Goffinet 2001

| Methods | Multicentre randomised trial. Stratified by centre and parity (nulliparous or multiparous). Blocks of 4. Randomisatioin numbers were established using tables of order 4 permutations. Individual woman. |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: uterine artery Doppler US

Control/comparison intervention: no Doppler US

|

|

| Outcomes | Principal outcome: IUGR (birthweight < 10% and < 3% according to gestational age).

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk |

|

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk |

|

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not possible to blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Loss of participants to follow up at each data collection point:

Exclusion of participants after randomisation:

|

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | 2 centres stopped inclusions a few month after the beginning of the study and did not send the records of 11 women they had included. Describe any baseline in balance: none identified. |

Subtil 2003

| Methods | Multicentre randomised controlled trial (12 centres). Block randomisation ‐ blocks of 8 or 16, stratified by centre. Unit of randomisation: individual woman, 2:1 ratio for randomisation of Doppler vs placebo. Part of a larger study (Essai Regional Aspirine Mere Enfant, ERASME trial) which evaluated the routine prescription of low‐dose aspirin (100mg) in nulliparous women. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: uterine artery Doppler US

Control/comparison intervention: no Doppler US

|

|

| Outcomes | Pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy related hypertension, very low or low birthweight for gestational age (birthweight ≤ 3rd and ≤ 10th centile of the standard curves used in France), HELLP syndrome, placental abruption or a caesarean section because of fetal indication (uncompensated maternal hypertension, suspected IUGR, meconium stained amniotic fluid or placental abruption). | |

| Notes | Doppler group included 22 twin pregnancies and the control group included 14 twin pregnancies. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | “...a randomisation list was computer generated by the manufacturer of the treatment boxes before the study began. Treatment randomisation was balanced in blocks of 8 and stratified by centre. Each block of eight box numbers was then randomly mixed, according to a random number table, with eight boxes labelled “Doppler”. The randomisation was thus balanced by blocks of 16 in these centres, and the box numbers were not consecutive.” |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | “...each patient was randomly allocated to a group immediately after inclusion by connection to an always available server.... After verifying the inclusion criteria and the patient’s consent, the server provided either a treatment box number or the word “Doppler” to the physician investigator. At the end of prenatal consultation the physician gave the patient a numbered treatment box (neither the physician nor the patient knew whether this was aspirin or placebo) or an appointment (between 22 and 24 weeks) for a utero‐placental artery Doppler.” |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | It was not possible to blind participants and clinicians with regard to the use of Doppler US or not (and the outcome assessor would often be the clinician), although participants and clinicians were blind to the use of aspirin or placebo in women with abnormal Doppler US results. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Loss of participants to follow up at each data collection point:

Exclusion of participants after randomisation:

Intention‐to‐treat analysis. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | The study was not stopped early. No baseline in balance:

|

AFI: amniotic fluid index BMI: basal metabolic rate BP: blood pressure CTG: cardiotocography HELLP: haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction NS: not significant ToP: termination of pregnancy UAD: uterine artery Doppler US: ultrasound

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Almstrom 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Ben‐Ami 1995 | This study is not randomised. |

| Biljan 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Burke 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Davies 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound, seeAlfirevic 2010b. |

| de Rochambeau 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Doppler 1997 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Giles 2003 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound with biometry. |

| Gonsoulin 1991 | Conference abstract ‐ not clear whether high‐risk/low‐risk/unselected pregnancies, and no data suitable for inclusion. Further details were sought from the authors by the authors of the previous Doppler for unselected population review, without success. |

| Haley 1997 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Hofmeyr 1991 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Johnstone 1993 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Mason 1993 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| McCowan 1996 | Conference abstract only but outcomes were comparing women with normal and abnormal Doppler ultrasound readings, so not a randomised comparison. |

| McParland 1988 | This study has never been reported in full although it has been partly reported in a review article (McParland 1988) and a full manuscript has been given to the review authors by Dr Pearce, who has been accused of publishing reports of trials whose veracity cannot be confirmed (BJOG 1995). Consequently, the Doppler trial data are not now thought by the review authors to be sufficiently reliable to be retained within this review. |

| Neales 1994 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Newnham 1991 | Study assessing umbilical artery and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound, see Alfirevic 2010a. |

| Newnham 1993 | Study assessing umbilical artery and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound (seeAlfirevic 2010b). |

| Nienhuis 1997 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Nimrod 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Norman 1992 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Omtzigt 1994 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Pattinson 1994 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Pearce 1992 | Dr Pearce has been accused of publishing reports of trials whose veracity cannot be confirmed (BJOG 1995). Consequently, the Doppler trial data are not now thought by the review authors to be sufficiently reliable to be retained within this review. |

| Schneider 1992 | Conference abstract in English language identified ‐ unexplained difference in numbers (250 vs 329) in Doppler vs control groups suggesting allocation bias. The definitive publication after translation from German did not explain this difference and failed to outline the trial methodology. |

| Scholler 1993 | This study was translated from German for us. It was a quasi‐RCT of 211 women undergoing Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound. It was excluded for a combination of the following reasons: the only outcome relevant to our review was induction of labour; the study had high risk of bias being a quasi‐RCT; further information was needed from the authors before this data could be included. Data reported for induction of labour: Doppler group 37/108 and no Doppler group 41/103. |

| Trudinger 1987 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Tyrrell 1990 | Study assessing umbilical artery and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound, seeAlfirevic 2010a. |

| Whittle 1994 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

| Williams 2003 | Study assessing umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound. |

RCT: randomised controlled trial vs: versus

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Ellwood 1997

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Individual woman. |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: uterine artery Doppler

Control/comparison intervention: no uterine artery Doppler

|

| Outcomes | Pre‐specified outcomes: gestational age at delivery, rate of preterm birth, unplanned admissions for pre‐eclampsia and fetal growth restriction and bed days, neonates with Apgar scores < 7 at 5 min, neonatal admissions and special care nursery bed days. |

| Notes | The study was still ongoing when this report was written. The plan was to recruit 524 women, 262 in each group (power calculation done on admission to neonatal nursery). At time of report 364 women had been randomised and 145 had given birth and been followed up. We are trying to contact the authors for further information. |

Snaith 2006

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. |

| Participants | Low‐risk primiparous women. |

| Interventions | Structured telephone support intervention provided by midwife +/‐ uterine artery Doppler screening. |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: number of antenatal contacts with health professionals. Secondary outcomes: number of antenatal admissions to hospital, anxiety, level of perceived social support, satisfaction with care, economic evaluation, major clinical outcomes. |

| Notes | Registered protocol: Current Controlled Trials (http://controlled‐trials.com/mrct). We are contacting the author for further information as this trial should have completed but we can find no publication. |

AFI: amniotic fluid index

Contributions of authors

T Stampalija drafted the background section and Z Alfirevic added further suggestions. G Gyte drafted the methodology section. T Stampalija and G Gyte decided on the studies to include and extracted the data. T Stampalija entered the data into RevMan (RevMan 2008) and G Gyte checked this. T Stampalija drafted the text of the findings and all authors agreed with the final version of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK.

NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme award for NHS‐prioritised centrally‐managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS02

Declarations of interest

No known conflicts of interest.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

- Goffinet F, Aboulker D, Paris‐Llado J, Bucourt M, Uzan M, Papiernik E, et al. Screening with a uterine doppler in low risk pregnant women followed by low dose aspirin in women with abnormal results: a multicenter randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2001;108:510‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]