Abstract

Background

Flurbiprofen is a non‐selective non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID), related to ibuprofen and naproxen, used to treat acute and chronic painful conditions. There is no systematic review of its use in acute postoperative pain.

Objectives

To assess efficacy, duration of action, and associated adverse events of single dose oral flurbiprofen in acute postoperative pain in adults.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Oxford Pain Relief Database for studies to January 2009.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled trials of single dose orally administered flurbiprofen in adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Pain relief or pain intensity data were extracted and converted into the dichotomous outcome of number of participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, from which relative risk (RR) and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) were calculated. Numbers of participants using rescue medication over specified time periods, and time to use of rescue medication, were sought as additional measures of efficacy. Information on adverse events and withdrawals were collected.

Main results

Eleven studies compared flurbiprofen (699 participants) with placebo (362 participants) in studies lasting 6 to 12 hours. Studies were of adequate reporting quality, and most participants had pain following dental extractions.

The dose of flurbiprofen used was 25 mg to 100 mg, with most information for 50 mg and 100 mg. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours for flurbiprofen 50 mg compared with placebo (692 participants) was 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3) and for 100 mg (416 participants) it was 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1). With flurbiprofen 50 mg and 100 mg 65% to 70% of participants experienced at least 50% pain relief, compared with 25% to 30% with placebo. Rescue medication was used by 25% and 16% of participants with flurbiprofen 50 mg and 100 mg over 6 hours, compared with almost 70% with placebo.

Adverse events were uncommon, and not significantly different from placebo.

Authors' conclusions

Flurbiprofen at doses of 50 mg and 100 mg is an effective analgesic in moderate to severe acute postoperative pain. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief is similar to that of commonly used NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen at usual doses. Use of rescue medication indicates a duration of action exceeding 6 hours.

Plain language summary

Single dose oral flurbiprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults

A single dose of flurbiprofen 50 mg or 100 mg provides a high level of pain relief to 65% to 70% of those with moderate or severe postoperative pain. It has similar efficacy to other commonly used analgesics at standard doses, including ibuprofen and naproxen, with a duration of action exceeding 6 hours. Adverse events were no more common with flurbiprofen than with placebo in these single dose studies.

Background

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care. This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level. Recently published reviews include paracetamol (Toms 2008), celecoxib (Derry 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), diclofenac (Derry P 2009) and etoricoxib (Clarke 2009).

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants is small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following 4 to 6 hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over 4 to 6 hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first 6 hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Clinicians prescribe non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on a routine basis for a range of mild‐to‐moderate pain. NSAIDs are the most commonly prescribed analgesic medications worldwide, and their efficacy for treating acute pain has been well demonstrated (Moore 2003). They reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase), the enzyme mediating production of prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 (FitzGerald 2001). Prostaglandins mediate a variety of physiological functions such as maintenance of the gastric mucosal barrier, regulation of renal blood flow, and regulation of endothelial tone. They also play an important role in inflammatory and nociceptive processes. However, relatively little is known about the mechanism of action of this class of compounds aside from their ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase‐dependent prostanoid formation (Hawkey 1999). Since NSAIDs do not depress respiration and do not impair gastro‐intestinal motility as do opioids (BNF 2002) they are clinically useful for treating pain after minor surgery and day surgery, and have an opiate‐sparing effect after more major surgery (Grahame‐Smith 2002).

Flurbiprofen, 2(3‐fluro‐4‐phenyl‐phenyl)‐propionic acid, is a potent, peripherally acting, nonsteroidal agent, structurally similar to ibuprofen, naproxen, fenoprofen and ketoprofen. Like other members of this group, it possesses analgesic, anti‐inflammatory, and antipyretic properties. The drug is well absorbed after oral administration with peak plasma levels occurring at 1 hour, and apparent half life of 3 to 4 hours (Kaiser 1986). Flurbiprofen undergoes rapid oxidative metabolism and is excreted primarily in the urine as both glucuronide and sulphate conjugates (Kaiser 1986). There are no known active metabolites in humans and there is no evidence of dose dependent alterations of pharmacokinetics or of drug accumulation in plasma after multiple dose administration (Brogden 1979; Kaiser 1986). Flurbiprofen inhibits cyclooxygenase‐1 and ‐2, with gastrointestinal tolerance considered better than aspirin and indomethacin, and comparable to ibuprofen and naproxen (Richy 2007). The drug has shown no untoward or irreversible carcinogenic, teratogenic, or hepatotoxic effects. Renal and hypertensive effects are likely to be similar to other NSAIDs.

Flurbiprofen is available typically as 50, 100, or 200 mg tablets or capsules, and is effective for arthritic disorders (Marcolongo 1983; Richy 2007) ankylosing spondylitis (Burry 1980; Lomen 1986a; Lomen 1986b), dysmenorrhoea (Pogmore 1980; Maclean 1983; Shapiro 1986) and postoperative pain relief (Dionne 1986). Licensed indications vary between countries. Although flurbiprofen has not been one of the more commonly used NSAIDs, perceived problems with COX‐2 inhibitors have caused clinicians to reconsider its place amongst a choice of other analgesics (Richy 2007). In 2007 there were 30,000 flurbiprofen prescriptions in England (PACT 2007).

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of oral flurbiprofen in the treatment of acute postoperative pain, using criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005), and methods that allow comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were full publications of double blind trials of a single dose oral flurbiprofen against placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least 10 participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were included provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

Studies were excluded if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of trials concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

studies using healthy volunteers;

studies where pain relief was assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e. not patient‐reported);

studies of less than 4 hours' duration or which failed to present data over 4 to 6 hours post‐dose.

Types of participants

Studies of adult participants (15 years old or above) with established moderate to severe postoperative pain were included. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was assumed when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). Studies of participants with postpartum pain were included provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). Studies investigating participants with pain due to uterine cramps alone were excluded.

Types of interventions

Flurbiprofen or matched placebo administered as a single oral dose for postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data collected included following:

characteristics of participants;

pain model;

patient‐reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain will not be included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief and/or pain intensity expressed hourly over 4 to 6 hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of visual analogue scales (VAS) or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at 4 to 6 hours;

patient‐reported global assessment of treatment (PGE), using a standard five‐point scale;

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched.

Cochrane CENTRAL (issue 4, 2008).

MEDLINE via Ovid (January 2009).

EMBASE via Ovid (January 2009).

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

Please see Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy.

Additional studies were sought from the reference lists of retrieved articles and reviews.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Abstracts, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched. The manufacturing pharmaceutical company were not contacted for unpublished trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or referral to a third review author.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b) that considers randomisation, blinding, and study withdrawals and dropouts.

The scale used is as follows.

Is the study randomised? If yes give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point.

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

Data management

Data were extracted by two review authors and recorded on a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling was entered into RevMan 5.0.

Data analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants who received study medication in each treatment group. Analyses were planned for different doses. Sensitivity analyses were planned for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (two versus three or more). A minimum of two studies and 200 participants were required for any analysis (Moore 1998).

Primary outcome:

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, the mean TOTPAR, SPID, VAS TOTPAR or VAS SPID values for active and placebo were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was then used to calculate relative benefit (RB) and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT).

Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, numbers of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" were taken as those achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

Further details of the scales and derived outcomes are in the glossary (Appendix 4).

Secondary outcomes:

Use of rescue medication. Numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication was used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

-

Adverse events. Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate RR and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study)

withdrawal due to an adverse event

Withdrawals. Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted, as were exclusions from analysis where data were presented.

RB or RR estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT, NNTp and NNH with 95% CIs were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the RB did not include the number one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbe 1987).

Results

Description of studies

Searches identified 20 potentially relevant studies of which 11 satisfied criteria for inclusion in this review (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986). One duplicate of Cooper 1986 was identified (Mardirossian 1985) and eight studies were excluded after reading the full paper (Dionne 1986; Dionne 2004; Dupuis 1988; Gallardo 1990; Ottinger 1990; Roszkowski 1997; Sisk 1985; Troullos 1990). Details for all studies considered are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables respectively.

In the 11 included studies the total number of participants was 1646, of whom 699 were treated with flurbiprofen (dose range 25 mg to 150 mg) and 362 with placebo.

Dose

Flurbiprofen 25 mg was given to 102 participants in three treatment arms (Cooper 1986; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983), flurbiprofen 50 mg to 353 participants in ten treatment arms (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989b; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986), flurbiprofen 100 mg to 215 participants in seven treatment arms (Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986), and flurbiprofen 150 mg to 29 participants in one treatment arm (Cooper 1988).

Study duration

Study duration was 6 hours in eight studies (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Dionne 1994; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986), 8 hours in two studies (Cooper 1988; Forbes 1989b) and 12 hours in one study (Forbes 1989a).

Type of surgery

Eight studies (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1991; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1986; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1986) enrolled participants with dental pain following extraction of at least one impacted third molar, one (Sunshine 1983) enrolled participants with pain following episiotomy, and two (De Lia 1986; Morrison 1986) with pain following obstetric or gynaecological surgery.

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies were both randomised and double blind.

Four studies were given a quality score of five (Cooper 1988; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986) four studies a score of four (Cooper 1986; De Lia 1986; Forbes 1989a; Morrison 1986) three studies a score of three (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994).

Full details are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Effects of interventions

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

All 11 studies provided data for quantitative analysis: 699 participants were treated with flurbiprofen and 362 participants received placebo.

Flurbiprofen 25 mg versus placebo

Three studies with 208 participants provided data (Cooper 1986; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983) (Table 1; Analysis 1.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with flurbiprofen 25 mg was 35% (36/102; range 26% to 41%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 5% (5/106; range 2% to 7%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 7.0 (2.9 to 16), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 3.3 (2.5 to 4.9).

Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo

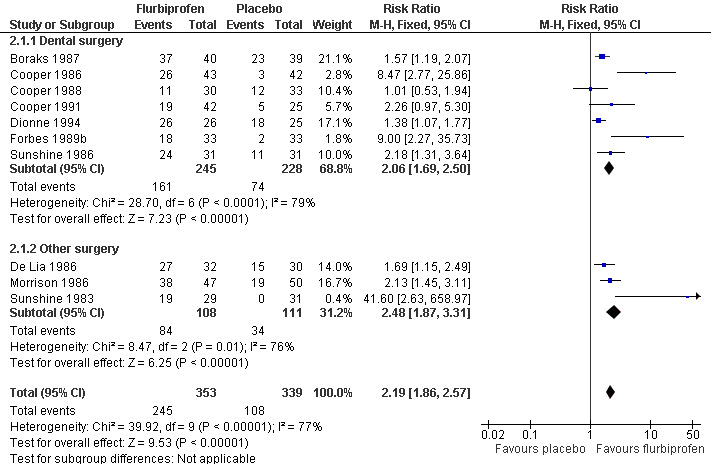

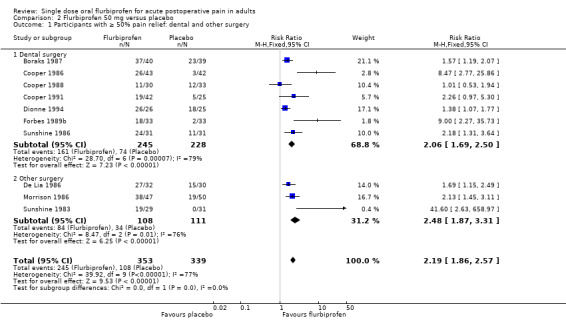

Ten studies with 692 participants provided data (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989b; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986) (Figure 1; Table 1).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief: dental and other surgery.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with flurbiprofen 50 mg was 69% (245/353; range 37% to 100%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 32% (108/339; range 0% to 72%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 2.2 (1.9 to 2.6), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3).

Flurbiprofen 100 mg versus placebo

Seven studies with 416 participants provided data (Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986) (Table 1; Analysis 3.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with flurbiprofen 100 mg was 65% (139/215; range 50% to 100%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 24% (48/201; range 0% to 72%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 2.8 (2.2 to 3.6), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1).

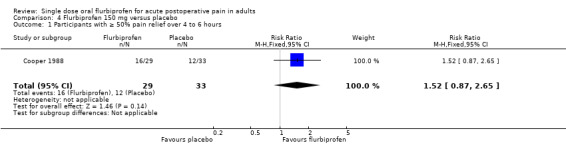

Flurbiprofen 150 mg was given to 29 participants in one study (Cooper 1988). Since there were only 62 participants in any comparison with placebo, no analysis was undertaken for this dose.

No significant difference in efficacy was demonstrated for different doses since the 95% CIs of the NNT estimates overlap.

| Summary of results A: Number of participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

| Dose | Studies | Participants | Flurbiprofen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| 25 mg | 3 | 208 | 36 | 5 | 3.3 (2.5 to 4.9) |

| 50 mg | 10 | 692 | 69 | 32 | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3) |

| 100 mg | 7 | 416 | 65 | 24 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1) |

Sensitivity analysis of primary outcome

Trial size

Only two studies (Cooper 1986; Morrison 1986) enrolled 40 or more participants in both treatment arms, so no subgroup analysis was carried out for this criterion. Treatment arms were generally small, with between 22 and 50 participants.

Quality score

All studies scored three or more so no analysis was carried out.

Pain model

There were sufficient data from non‐dental studies to permit this sensitivity analysis for flurbiprofen 50 mg only (Figure 1).

Seven studies (473 participants) used flurbiprofen 50 mg in dental pain (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Dionne 1994; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1986). The RB for treatment compared with placebo was 2.1 (1.7 to 2.5), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0).

Three studies (219 participants) used flurbiprofen 50 mg in obstetric and gynaecological pain (De Lia 1986; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983). The RB for treatment compared with placebo was 2.5 (1.9 to 3.3), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.1 (1.7 to 2.8).

The 95% CIs overlap indicating no significant difference between pain models.

Use of rescue medication

Proportion of participants using rescue medication

All studies reporting this outcome did so at 6 hours.

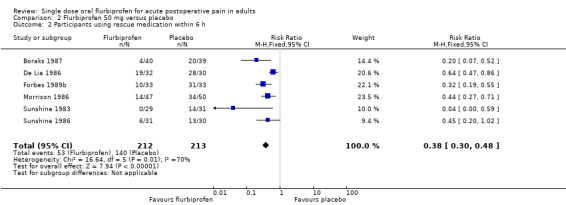

In six studies using flurbiprofen 50 mg (Boraks 1987; De Lia 1986; Forbes 1989b; Morrison 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986) the weighted mean proportion using rescue medication with flurbiprofen was 25% (53/212) and with placebo was 66% (140/213). The NNTp for remedication by 6 hours was 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1) (Analysis 2.2).

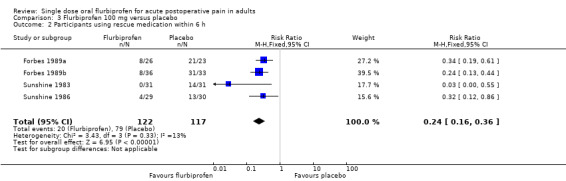

In four studies using flurbiprofen 100 mg (Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986) the weighted mean proportion using rescue medication with flurbiprofen was 16% (20/122) and with placebo was 68% (79/117). The NNTp for remedication by 6 hours was 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) (Analysis 3.2).

There were insufficient data to give a robust estimate for this outcome for flurbiprofen 25 mg, but it is included in the Summary of results B for comparison. The results are compatible with a dose response, but the differences are not significantly different.

| Summary of results B: Participants using rescue medication within 6 hours | |||||

| Dose | Studies | Participants | Flurbiprofen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNTp (95%CI) |

| 25 mg | 2 | 127 | 35 | 70 | 2.8 (1.5 to 9.2) |

| 50 mg | 6 | 425 | 25 | 66 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1) |

| 100 mg | 4 | 239 | 16 | 68 | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) |

Time to use rescue medication

Two studies reported median time (Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b) and two the mean time (Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988) to use of rescue medication. There were insufficient data for analysis by dose.

Adverse events

Any adverse event

Nine studies reported the numbers of participants experiencing at least one adverse event. Six studies reported adverse events occurring over 6 hours (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986), two studies over 8 hours (Cooper 1988; Forbes 1989b), and one over 12 hours (Forbes 1989a).

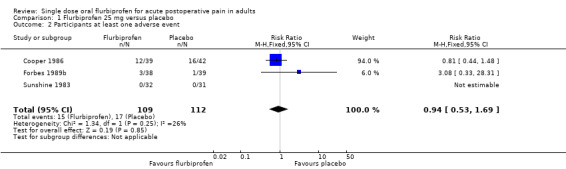

Three studies using flurbiprofen 25 mg reported on the number of participants with at least one adverse event (Cooper 1986; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983): 14% (15/109) with flurbiprofen and 16% (17/112) with placebo (Analysis 1.2).

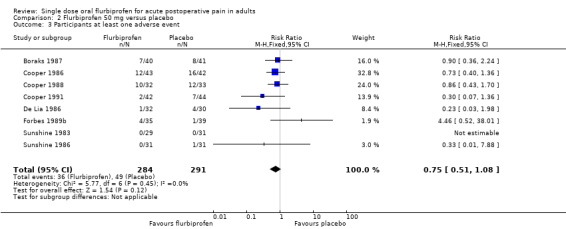

Eight studies using flurbiprofen 50 mg reported on the number of participants with at least one adverse event (Boraks 1987; Cooper 1986; Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; De Lia 1986; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986): 13% (37/284) with flurbiprofen and 17% (50/290) with placebo (Analysis 2.3).

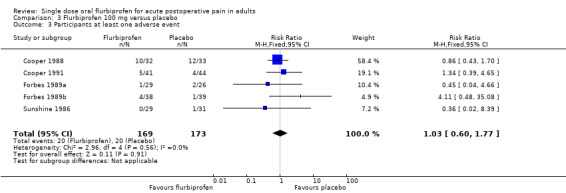

Six studies using flurbiprofen 100 mg reported on the number of participants with at least one adverse event (Cooper 1988; Cooper 1991; Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b; Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1986): 10% (20/200) with flurbiprofen and 12% (24/203) with placebo (Analysis 3.3). (Summary of results C).

| Summary of results C: Participants with at least one adverse event | |||||

| Dose | Studies | Participants | Flurbiprofen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNH (95%CI) |

| 25 mg | 3 | 221 | 14 | 16 | not calculated |

| 50 mg | 8 | 574 | 13 | 17 | not calculated |

| 100 mg | 6 | 403 | 10 | 12 | not calculated |

There was no significant difference between flurbiprofen at any dose and placebo for the number of participants reporting at least one adverse event.

Serious adverse events

No studies reported any serious adverse events.

Withdrawals

Participants who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, and details are reported under "Use of rescue medication" above.

Most studies reported some exclusions from efficacy analyses, and sometimes safety analyses. Exclusions may not be of any particular consequence in single dose acute pain studies, where most result from patients not having moderate or severe pain (McQuay 1982).

Two studies reported withdrawals due to adverse events. In one (Cooper 1988) one participant treated with flurbiprofen 100 mg had postoperative bleeding, and in the other (De Lia 1986) two participants withdrew because of unspecified adverse events.

See Table 1 for details of results for measures of pain relief and use of rescue medication and Table 2 for details of results for adverse events and withdrawals. See also Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 3.1 for additional information on pain relief, Analysis 2.2 and Analysis 3.2 for additional information on use of rescue medication, and Analysis 1.2, Analysis 2.3 and Analysis 3.2 for additional information on adverse events.

1. Summary of outcomes: analgesia and use of rescue medication.

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGE: v good or excellent | Median time to use (hr) | % using |

| Boraks 1987 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 (2) Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 (3) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 41 (4) Placebo, n = 39 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 18.8 (4) 12.9 |

(1) 37/40 (4) 23/39 |

6 hours 1) 25/40 4) 11/39 |

No data | (1) 4/40 (4) 20/39 |

| Cooper 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 39 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 43 (3) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 42 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.64 (2) 12.98 (4) 3.29 |

(1) 16/39 (2) 26/43 (4) 3/42 |

no usable data | Mean: (1) 4.1 (2) 4.8 (4) 2.9 |

no data |

| Cooper 1988 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 30 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 30 (3) Flurbiprofen 150 mg, n = 29 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 29 (5) Placebo, n = 33 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.48 (2)11.03 (3) 12.09 (5) 8.48 |

(1) 11/30 (2) 15/30 (3) 16/29 (5) 12/33 |

no usable data | Mean: (1) 4.9 (2) 5.5 (3) 5.6 (5) 2.4 |

no data |

| Cooper 1991 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 42 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 37 (4) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 39 (5) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 23 (6) Placebo, n = 25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.3 (2) 13.4 (6) 5.7 |

(1) 19/42 (2) 26/41 (6) 9/44 |

(1) 17/42 (2) 22/41 (6) 1/25 |

no data | no usable data |

| De Lia 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 32 (2) Placebo capsule + morphine 10 mg IM, n = 30 (3) Placebo capsule + placebo injection, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 17.3 (3) 10.8 |

(1) 27/32 (3) 14/30 |

No usable data | No data | (1) 59 (3) 93 |

| Dionne 1994 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 26 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 22 (3) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 27 (4) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 24 (5) Placebo, n = 25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 20.8 (2) 22.1 (5)14.9 |

(1) 26/26 (2) 22/22 (5) 18/25 |

no usable data | no data | no data |

| Forbes 1989a | (1) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 26 (2) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 22 (3) Paracetamol/codeine 600/60 mg, n = 17 (4) Placebo, n = 23 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.5 (4) 2.0 |

(1) 15/26 (4) 0/23 |

no data | (1) 1.7 (4) 10.9 |

at 6h: (1) 31 (4) 92 at 12 h: (1) 65 (4) 91 |

| Forbes 1989b | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 31 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 33 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 36 (4) Aspirin 600 mg, n = 31 (5) Placebo, n = 33 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.5 (2) 11.8 (3) 12.2 (5) 3.4 |

(1) 8/31 (2) 18/33 (3) 20/36 (5) 2/33 |

no data | (1) 3.5 (2) > 8 (3) > 8 (5) 2.3 |

At 6 h: (1) 66 (2) 31 (3) 23 (5) 95 At 8 h: (1) 68 (2) 42 (3) 23 (5) 94 |

| Morrison 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 47 (2) Morphine 10 mg IM + placebo capsule, n = 47 (3) placebo capsule +injection, n = 50 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 16.6 (3) 9.0 |

(1) 38/47 (3) 19/50 |

no usable data | no data | At 6 h: (1) 14/47 (3) 34/50 |

| Sunshine 1983 | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 32 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 29 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 31 (4) Aspirin 600 mg, n = 29 (5) Placebo, n = 31 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.0 (2) 13.8 (3) 13.8 (5) 2.3 |

(1) 12/32 (2) 19/29 (3) 20/31 (5) 0/31 |

no data | no data | At 6 h:

(1) 1/32 (2) 0/29 (3) 0/31 (5) 14/31 |

| Sunshine 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 31 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 29 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 31 (4) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 (5) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 31 (6) Placebo, n = 31 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 16.2 (2) 15.5 (6) 8.3 |

(1) 24/31 (2) 21/29 (6)11/31 |

no usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 6/31 (2) 4/29 (6) 13/30 |

2. Summary of outcomes: adverse events and withdrawals.

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Boraks 1987 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 (2) Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 (3) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 41 (4) Placebo, n = 39 |

At 6 h: (1) 7/40 (4) 8/41 |

None | None reported | none reported |

| Cooper 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 39 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 43 (3) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 42 |

(1) 12/39 (2) 12/43 (4) 16/42 |

None reported | none reported | Exclusions due to protocol violations: (1) 3 (2) 0 (4) 1 |

| Cooper 1988 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 30 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 30 (3) Flurbiprofen 150 mg, n = 29 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 29 (5) Placebo, n = 33 |

At 8 h: (1) 10/32 (2) 9/32 (3) 6/31 (5) 12/33 |

None reported | (2) 1 (postop bleed) | Exclusions due to protocol violations: (1) 2 (2) 1 (3) 3 (5) 0 |

| Cooper 1991 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 42 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 37 (4) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 39 (5) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 23 (6) Placebo, n = 44 |

At 6 h: (1) 2/42 (2) 5/41 (6) 7/44 |

None reported | none reported | 21 received medication but not evaluated: 3 lost to follow up, 18 protocol violations No details of groups |

| De Lia 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 32 (2) Placebo capsule + morphine 10 mg IM, n = 30 (3) Placebo capsule + placebo injection, n = 30 |

(1) 1/32 (3) 4/30 |

None | 2 ‐ group and details not specified | none reported |

| Dionne 1994 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 26 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 22 (3) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 27 (4) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 24 (5) Placebo, n = 25 |

Data not reported for single dose | None reported | none reported | 11 received medication but not evaluated: 2 lost to follow up 9 protocol violations. No details of groups |

| Forbes 1989a | (1) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 26 (2) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 22 (3) Paracetamol/codeine 600/60 mg, n = 17 (4) Placebo, n = 23 |

At 12h: (1) 1/29 (4) 2/26 |

None reported | none reported | 10 received medication but not evaluated for efficacy due to protocol violations. No details of groups |

| Forbes 1989b | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 31 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 33 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 36 (4) Aspirin 600 mg, n = 31 (5) Placebo, n = 33 |

At 8 h: (1) 3/38 (2) 4/35 (3) 4/38 (5) 1/39 |

None reported | none reported | 24 received medication but not evaluated for efficacy due to protocol violations. 3 lost to follow up. No details of groups |

| Morrison 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 47 (2) Morphine 10 mg IM + placebo capsule, n = 47 (3) Placebo capsule + injection, n = 50 |

Not reported | Not reported | none reported | 20 either did not receive medication (not enough pain), or had protocol violations (1) 0/47 (3) 0/50 |

| Sunshine 1983 | (1) Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 32 (2) Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 29 (3) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 31 (5) Placebo, n = 31 |

None | None | none reported | 16 received medication but excl form analysis due to protocol violation

(1) 3 (2) 5 (3) 3 (5) 1 |

| Sunshine 1986 | (1) Flurbiprofen 50 mg n = 31 (2) Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 29 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 31 (4) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 (5) Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 31 (6) Placebo, n = 31 |

At 6 hrs: (1) 0/31 (2) 0/29 (6) 1/31 |

None | None reported | none reported |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Flurbiprofen 25 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Flurbiprofen 100 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 h.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Flurbiprofen 100 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 h.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Flurbiprofen 25 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants at least one adverse event.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants at least one adverse event.

Discussion

This review included 11 studies using flurbiprofen to treat acute pain following dental and gynaecological surgery in comparisons with placebo over 6 to 8 hours. In total, 699 participants were treated with flurbiprofen and 362 with placebo. Most of the information was for the 50 mg and 100 mg doses. Methodological quality was good, with all studies scoring at least the minimum required to minimise bias.

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 6 hours with flurbiprofen 50 mg was 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3), and no clear dose response was demonstrated. Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that flurbiprofen 50 mg has equivalent efficacy to naproxen 500/550 mg (2.7 (2.3 to 3.2)) (Derry C 2009a), ibuprofen 200 mg (2.7 (2.5 to 3.0)) (Derry C 2009b), and lumiracoxib 400 mg (2.7 (2.2 to 3.5)) (Roy 2007). Flurbiprofen 100 mg (2.5 (2.0 to 3.1)) shows equivalent efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg (2.5 (2.4 to 2.6)) (Derry C 2009b), although with wider CIs as a result of less data. Both doses are better than paracetamol 1000 mg (3.6 (3.2 to 4.1)) (Toms 2008), but worse than etoricoxib 120 mg (1.9 (1.7 to 2.1)) (Clarke 2009).

Sensitivity analysis did not show a difference between dental and other types of surgery for flurbiprofen 50 mg, but data from non dental studies was limited. The wide range of response rates in these non dental studies may be due to different responses in different types of surgery (Barden 2004).

It has been suggested that data on use of rescue medication, whether as a proportion of participants requiring it, or the median time to use of it, might be helpful in assessing the usefulness of an analgesic, and possibly distinguishing between different doses (Moore 2005). Significantly fewer participants needed rescue medication within 6 hours with both 50 mg and 100 mg flurbiprofen than with placebo, with NNTps of 2.5 and 2.0 respectively. A significant dose response was not demonstrated, but there was a trend for less remedication at higher doses. There were insufficient data to provide an estimate of median or mean time to use of rescue medication. Thirty five percent of participants taking flurbiprofen 100 mg used rescue medication over the first 6 hours which points to the median time being greater than 6 hours, and for the two studies that did report this outcome (Forbes 1989a; Forbes 1989b, 118 participants) it was around 9 hours, compared with 2 hours for placebo. This is similar to the median time to remedication with naproxen (Derry C 2009a, 8.9 hours) and celecoxib 400 mg (Derry 2008, 8.4 hours), and longer than for diclofenac (Derry P 2009, 4.3 hours) and ibuprofen 400 mg (Derry C 2009b, 5.4 hours), but shorter than etoricoxib 120 mg (Clarke 2009, 20 hours).

Flurbiprofen was well tolerated in these single dose studies with rates of adverse events that did not differ from placebo. Most were mild to moderate in intensity, and where details were provided they were compatible with the effects of anaesthetic and surgical procedures. There were three withdrawals due to adverse events. One was due to a postoperative bleed (Cooper 1988), and there were no further details provided for the other two (De Lia 1986). The usefulness of single dose studies for assessing adverse events is questionable, but it is non‐the‐less reassuring that there was no difference between flurbiprofen (at any dose) and placebo for occurrence of any adverse event, and that serious adverse events and adverse event withdrawals were rare, and not necessarily related to the test drug. Long‐term, multiple dose studies should be used for meaningful analysis of adverse events since, even in acute pain settings, analgesics are likely to be used in multiple doses.

In single dose studies most exclusions occur for protocol violations such as failing to meet baseline pain requirements (McQuay 1982), or failing to return for post treatment visits after the acute pain results are concluded. Where patients are treated with a single dose of medication and observed, often "on site" for the duration of the trial, it might be considered unnecessary to report on "withdrawals" if there were none. For missing data it has been shown that over the 4 to 6 hour period, there is no difference between baseline observation carried forward, which gives the more conservative estimate, and last observation carried forward (Moore 2005).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Flurbiprofen at doses of 50 mg and 100 mg is an effective analgesic in acute postoperative pain, providing clinically useful levels of pain relief to 65% to 70% of those treated, compared with 25% to 30% with placebo. The NNT of 2.5 for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours for the 100 mg dose compares favourably with that of other commonly used analgesics such as ibuprofen 400 mg. The NNTp for use of rescue medication within 6 hours, at 2.0, is lower (better) than ibuprofen, implying a longer duration of action. Flurbiprofen was well tolerated with adverse events similar to placebo.

Implications for research.

Further studies at higher and lower dose would help to establish whether there is a significant dose response, and so whether using a higher dose provides additional benefit. Future studies should report median time to use of rescue medication to confirm a relatively long duration of action.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 10 November 2010 | Review declared as stable | The authors declare that there is unlikely to be any further studies to be included in this review and so it should be published as a 'stable review'. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2008 Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Notes

The authors declare that there is unlikely to be any further studies to be included in this review and so it should be published as a 'stable review'.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy (via OVID)

1. Flurbiprofen.sh

2. (flurbiprofen OR Ansaid OR Froben).ti,ab,kw.

3. OR/1‐2

4. Pain, postoperative.sh

5. ((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")).ti,ab,kw.

6. ((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)).ti,ab,kw.

7. (("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")).ti,ab,kw.

8. (("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti,ab,kw.

9. ((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

10. ((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

11. OR/4‐10

12. randomized controlled trial.pt.

13. controlled clinical trial.pt.

14. randomized.ab.

15. placebo.ab.

16. drug therapy.fs.

17. randomly.ab.

18. trial.ab.

19. groups.ab.

20. OR/12‐19

21. humans.sh.

22. 20 AND 21

23. 3 AND 11 AND 22

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy (via OVID)

1. Flurbiprofen.sh

2. (flurbiprofen OR Ansaid OR Froben).ti,ab,kw.

3. OR/1‐2

4. Postoperative pain.sh

5. ((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")).ti,ab,kw.

6. ((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)).ti,ab,kw.

7. (("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")).ti,ab,kw.

8. (("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti,ab,kw.

9. ((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

10. ((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).ti,ab,kw.

11. OR/4‐10

12. clinical trials.sh

13. controlled clinical trials.sh

14. randomized controlled trial.sh

15. double‐blind procedure.sh

16. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ab

17. ((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ab

18. placebo$.ab

19. random$.ab

20. OR/12‐19

21. 3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy (via OVID)

1. MESH descriptor Flurbiprofen

2. (flurbiprofen OR Ansaid OR Froben).ti,ab,kw.

3. OR/1‐2

4. MESH descriptor Pain, Postoperative

5. ((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")):ti,ab,kw.

6. ((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)):ti,ab,kw.

7. (("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")):ti,ab,kw.

8. (("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)):ti,ab,kw.

9. ((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")):ti,ab,kw.

10. ((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")):ti,ab,kw.

11. OR/4‐10

12. Clinical trials:pt.

13. Controlled Clinical Trial:pt.

14. Randomized Controlled Trial.pt.

15. MESH descriptor Double‐Blind Method

16. (clin$ adj25 trial$):ti,ab,kw.

17. ((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)):ti,ab,kw.

18. placebo$:ti,ab,kw.

19. random$:ti,ab,kw.

20. OR/12‐19

21. 3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale:

The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3 and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross‐modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily.

VAS:

Visual analogue scale: For pain intensity, lines with left end labelled "no pain" and right end labelled "worst pain imaginable", and for pain relief lines with left end labelled "no relief of pain" and right end labelled "complete relief of pain", seem to overcome the limitation of forcing patient descriptors into particular categories. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain or pain relief. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient's mark, usually in millimetres. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and coordination are needed, which can be difficult post‐operatively or with neurological disorders.

TOTPAR:

Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a 6 hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the composite trapezoidal rule. This is a simple method that approximately calculates the definite integral of the area under the pain relief curve by calculating the sum of the areas of several trapezoids that together closely approximate to the area under the curve.

SPID:

Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule. VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID. See “Measuring pain” in Bandolier’s Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7‐13 (Moore 2003).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Flurbiprofen 25 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 3 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.96 [2.95, 16.47] |

| 2 Participants at least one adverse event | 3 | 221 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.53, 1.69] |

Comparison 2. Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief: dental and other surgery | 10 | 692 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.19 [1.86, 2.57] |

| 1.1 Dental surgery | 7 | 473 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.06 [1.69, 2.50] |

| 1.2 Other surgery | 3 | 219 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.48 [1.87, 3.31] |

| 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 h | 6 | 425 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.30, 0.48] |

| 3 Participants at least one adverse event | 8 | 575 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.51, 1.08] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Flurbiprofen 50 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief: dental and other surgery.

Comparison 3. Flurbiprofen 100 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 7 | 416 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.77 [2.14, 3.59] |

| 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 h | 4 | 239 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.16, 0.36] |

| 3 Participants at least one adverse event | 5 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.60, 1.77] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Flurbiprofen 100 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants at least one adverse event.

Comparison 4. Flurbiprofen 150 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.87, 2.65] |

| 2 Participants at least one adverse event | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.23, 1.24] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Flurbiprofen 150 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Flurbiprofen 150 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants at least one adverse event.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Boraks 1987.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 hours. |

|

| Participants | Dental extraction N = 159 M = 84, F = 75 Mean age 27 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 40 Dipyrone 500 mg, n = 39 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 41 Placebo, n = 39 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Numbers with adverse events: any, serious |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 No potentially confounding medication within 6 hours |

|

Cooper 1986.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain evaluated at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 164 M = 97, F = 67 Mean age 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 39 Flurbiprofen 50 mg n = 43 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 No analgesics, hypnotics, psychotropic agents or caffeine within 6 hours |

|

Cooper 1988.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain evaluated at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 151 M = 81, F = 70 Mean age 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 30 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 30 Flurbiprofen 150 mg, n = 29 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 29 Placebo, n = 33 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 No analgesics, hypnotics, psychotropic agents, within 8 hours |

|

Cooper 1991.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 226 (207 analysed) M = 80, F = 146 Mean age 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 42 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 41 Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 37 Paracetamol/Codeine 650/60 mg, n = 39 Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 23 Placebo n = 25 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 | |

De Lia 1986.

| Methods | RCT, DB, DD, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Major gynaecological surgery N = 92 All F Mean age 30 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 32 Placebo capsule + morphine 10 mg IM, n = 30 Placebo capsule + placebo injection, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Free of analgesics for 4 hours before test medication |

|

Dionne 1994.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 124 M = 57, F = 67 Mean age 29 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 26 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 22 Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 27 Paracetamol/Codeine 650/60 mg, n = 24 Placebo, n = 25 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Number with adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 No drug with analgesic properties other than local anaesthetics within 4 hours of study medication |

|

Forbes 1989a.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 88 M = 39, F = 49 Age ≥ 15 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 26 Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 22 Paracetamol/codeine 600/60 mg, n = 17 Placebo, n = 23 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 No analgesics, hypnotics, psychotropic agents, caffeine within 12 hours |

|

Forbes 1989b.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 hours |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 164 M = 64, F = 100 Mean age 22 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 31 Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 33 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 36 Aspirin 600 mg, n = 31 Placebo, n = 33 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Number with adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Long‐term users of analgesics or tranquillizers excluded |

|

Morrison 1986.

| Methods | RCT, DB, DD, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Moderate to severe pain following major obstetric or gynaecological surgery N = 144 All F Mean age 26 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg + placebo injection, n = 47 Morphine 10 mg Im + placebo capsule, n = 47 Placebo capsule + injection, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Free of analgesics for 4 hours before test medication |

|

Sunshine 1983.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours. |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy N = 152 All F Mean age 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 25 mg, n = 32 Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 29 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 31 Aspirin 600 mg, n = 29 Placebo, n = 31 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, severe Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 No medication that could confound efficacy or adverse event analysis within 4 hours of study medication |

|

Sunshine 1986.

| Methods | RCT, DB, Parallel group, single dose Medication administered when baseline pain was of moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours. |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar surgery N = 183 M = 67, F = 115 Mean age 22 years |

|

| Interventions | Flurbiprofen 50 mg, n = 31 Flurbiprofen 100 mg, n = 29 Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 31 Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 Paracetamol/codeine 650/60 mg, n = 31 Placebo, n = 31 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: non standard scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, severe Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 | |

DB ‐ double blind; DD ‐ double dummy; IM ‐ intramuscular; M ‐ male; N ‐ total number of participants; n ‐ number of participants in treatment arm; F ‐ female; PGE ‐ patient global evaluation of efficacy; PI ‐ pain intensity; PR ‐ pain relief; R ‐ randomised; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial; std ‐ standard; W ‐ withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Dionne 1986 | No placebo controls. |

| Dionne 2004 | Treatment given preoperatively, before pain was established. |

| Dupuis 1988 | Treatment given preoperatively, before pain was established. |

| Gallardo 1990 | Duration of study 3 hours. |

| Ottinger 1990 | Treatment given preoperatively, before pain was established. |

| Roszkowski 1997 | Data for pain intensity given for time after surgery, not time after drug administration, with mean time of administration for both treatment groups: data for < 4 hours post dose. |

| Sisk 1985 | Treatment given preoperatively, before pain was established. |

| Troullos 1990 | Treatment given preoperatively, before pain was established. |

Contributions of authors

AS and SD carried out the searches, selected studies for inclusion, and carried out the data extraction. RAM, AS and SD carried out the analysis. HJM helped with analysis and acted as arbitrator. All review authors contributed to the writing of the protocol and full review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

Declarations of interest

SD, RAM and HJM have received research support from charities, government and industry sources at various times, but no such support was received for this work. RAM and HJM have consulted for various pharmaceutical companies. RAM, and HJM have received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Boraks 1987 {published data only}

- Boraks S. Flurbiprofen in low dose compared to dipirona, acido acetilsalicilico and placebo in the treatment of pain post teeth extraction [Flurbiprofen em dose baixa comparado a dipirona, acido acetilsalicilico e placebo no tratamento da dor pos‐extracao dentaria]. Arquivos Brasileiros Medicina 1987;61(4):24‐30. [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1986 {published data only}

- Cooper SA, Mardirossian G. Comparison of flurbiprofen and aspirin in the relief of postsurgical pain using the dental pain model. The American Journal of Medicine 1986;24;80(3A):36‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardirossian G, Cooper SA. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy of flurbiprofen and aspirin for postsurgical dental pain. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 1985;43(2):106‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1988 {published data only}

- Cooper SA, Mardirossian G, Milles M. Analgesic relative potency assay comparing flurbiprofen 50, 100, and 150 mg, aspirin 600 mg, and placebo in postsurgical dental pain. Clinical Journal of Pain 1988;4 (1):75‐81. [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1991 {published data only}

- Cooper SA, Kupperman A. The analgesic efficacy of flurbiprofen compared to acetaminophen with codeine. Journal of Clinical Dentistry 1991;2(3):70‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Lia 1986 {published data only}

- Lia JE, Rodman KC, Jolles CJ. Comparative efficacy of oral flurbiprofen, intramuscular morphine sulfate, and placebo in the treatment of gynecologic postoperative pain. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):60‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dionne 1994 {published data only}

- Dionne RA, Snyder J, Hargreaves KM. Analgesic efficacy of flurbiprofen in comparison with acetaminophen, acetaminophen plus codeine, and placebo after impacted third molar removal. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 1994;52(9):919‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forbes 1989a {published data only}

- Forbes JA, Butterworth GA, Burchfield WH, Yorio CC, Selinger LR, Rosenmertz SK, et al. Evaluation of flurbiprofen, acetaminophen, an acetaminophen‐codeine combination, and placebo in postoperative oral surgery pain. Pharmacotherapy 1989;9(5):322‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forbes 1989b {published data only}

- Forbes JA, Yorio CC, Selinger LR, Rosenmertz SK, Beaver WT. An evaluation of flurbiprofen, aspirin, and placebo in postoperative oral surgery pain. Pharmacotherapy 1989;9(2):66‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morrison 1986 {published data only}

- Morrison JC, Harris J, Sherrill J, Heilman CJ, Bucovaz ET, Wiser WL. Comparative study of flurbiprofen and morphine for postsurgical gynecologic pain. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):55‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sunshine 1983 {published data only}

- Sunshine A, Olson NZ, Laska EM, Zighelboim I, Castro A, Sarrazin C. Analgesic effect of graded doses of flurbiprofen in post‐episiotomy pain. Pharmacotherapy 1983;3(3):177‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sunshine 1986 {published data only}

- Sunshine A, Marrero I, Olson N, McCormick N, Laska EM. Comparative study of flurbiprofen, zomepirac sodium, acetaminophen plus codeine, and acetaminophen for the relief of postsurgical dental pain. American Journal of Medicine 1986;24;80(3A):50‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Dionne 1986 {published data only}

- Dionne RA. Suppression of dental pain by the preoperative administration of flurbiprofen. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):41‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dionne 2004 {published data only}

- Dionne RA, Haynes D, Brahim JS, Rowan JS, Guivarc'h PH. Analgesic effect of sustained‐release flurbiprofen administered at the site of tissue injury in the oral surgery model. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2004;44(12):1418‐24. [DOI: 10.1177/0091270004265703] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dupuis 1988 {published data only}

- Dupuis R, Lemay H, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Preoperative flurbiprofen in oral surgery: a method of choice in controlling postoperative pain. Pharmacotherapy 1988;8(3):193‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallardo 1990 {published data only}

- Gallardo F, Rossi E. Analgesic efficacy of flurbiprofen as compared to acetaminophen and placebo after periodontal surgery. Journal of Periodontology 1990;61(4):224‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ottinger 1990 {published data only}

- Ottinger ML, Kinney KW, Black JR, Wittenberg M. Comparison of flurbiprofen and acetaminophen with codeine in postoperative foot pain. Journal of American Podiatric Medical Association 1990;80(5):266‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roszkowski 1997 {published data only}

- Roszkowski MT, Swift JQ, Hargreaves KM. Effect of NSAID administration on tissue levels of immunoreactive prostaglandin E2, leukotriene B4, and (S)‐flurbiprofen following extraction of impacted third molars. Pain 1997;73(3):339‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sisk 1985 {published data only}

- Sisk AL, Bonnington GJ. Evaluation of methylprednisolone and flurbiprofen for inhibition of the postoperative inflammatory response. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology 1985;60(2):137‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Troullos 1990 {published data only}

- Troullos ES, Hargreaves KM, Butler DP, Dionne RA. Comparison of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, ibuprofen and flurbiprofen,with methylprednisolone and placebo for acute pain, swelling, and trismus. Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 1990;48(9):945‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Barden 2004

- Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Pain and analgesic response after third molar extraction and other postsurgical pain. Pain 2004;107(1‐2):86‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BNF 2002

- Anonymous. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. In: Mehta DK editor(s). British National Formulary. 43. Vol. March, London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 2002:482. [Google Scholar]

Brogden 1979

- Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Flurbiprofen: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in rheumatic diseases Drugs. Drugs 1979;18(6):417‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burry 1980

- Burry HC, Siebers R. A comparison of flurbiprofen with naproxen in ankylosing spondylitis. New Zealand Medical Journal 1980;92(670):309‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2009

- Clarke R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral etoricoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004309.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 1997

- Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres?. Pain 1997;72:95‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2001

- Collins SL, Edwards J, Moore RA, Smith LA, McQuay HJ. Seeking a simple measure of analgesia for mega‐trials: is a single global assessment good enough?. Pain 2001;91:189‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1995

- Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;310:452‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1991

- Cooper SA. Single‐dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside of assay sensitivity. In: Max MB, Portenoy RK, Laska EM editor(s). The Design of Analgesic Clinical Trials (Advances in Pain Research and Therapy). Vol. 18, New York: Raven Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Derry 2008

- Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004233.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry C 2009a

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004234.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry C 2009b

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001548.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry P 2009

- Derry P, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral diclofenac for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004768.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dionne 1986

- Dionne RA. Suppression of dental pain by the preoperative administration of flurbiprofen. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):41‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FitzGerald 2001

- FitzGerald GA, Patrono C. The coxibs, selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase‐2. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;345(6):433‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grahame‐Smith 2002

- Grahame‐Smith DG, Aronson JK . Oxford Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. [ISBN: 13: 978‐0‐19‐263234‐0] [Google Scholar]

Hawkey 1999

- Hawkey CJ. COX‐2 inhibitors. The Lancet 1999;353(9149):307‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996a

- Jadad AR, Carroll D, Moore RA, McQuay H. Developing a database of published reports of randomised clinical trials in pain research. Pain 1996;66(2‐3):239‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996b

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaiser 1986

- Kaiser DG, Brooks CD, Lomen PL. Pharmacokinetics of flurbiprofen. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):10‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

L'Abbe 1987

- L'Abbé KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta‐analysis in clinical research. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987;107:224‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lomen 1986a

- Lomen PL, Turner LF, Lamborn KR, Brinn EL. Flurbiprofen in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. a comparison with indomethacin. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):127‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lomen 1986b

- Lomen PL, Turner LF, Lamborn KR, Brinn EL, Sattler LP. Flurbiprofen in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. a comparison with phenylbutazone. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):120‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maclean 1983

- Maclean D. A comparison of flurbiprofen and paracetamol in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. Journal of International Medical Research 1983;11(Suppl 2):1‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marcolongo 1983

- Marcolongo R, Giordano N, Fioravanti A. Flurbiprofen in rheumatoid arthritis: a long‐term experience. Current Therapeutic Research ‐ Clinical and Experimental 1983;33(31):423‐7. [Google Scholar]

McQuay 1982

- McQuay HJ, Bullingham RE, Moore RA, Evans PJ, Lloyd JW. Some patients don't need analgesics after surgery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1982;75(9):705‐8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McQuay 2005

- McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Placebo. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2005;81:155‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 1999

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet 1999;354:1896‐900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1996

- Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics. Pain 1996;66(2‐3):229‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997a

- Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: Verification from independent data. Pain 1997;69(1‐2):127‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997b

- Moore A, Moore O, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: Use of pain intensity and visual analogue scales. Pain 1997;69(3):311‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1998

- Moore RA, Gavaghan D, Tramèr MR, Collins SL, McQuay HJ. Size is everything‐large amounts of information are needed to overcome random effects in estimating direction and magnitude of treatment effects. Pain 1998;78(3):209‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2003

- Moore RA, Edwards J, Barden J, McQuay HJ. Bandolier's Little Book of Pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [ISBN: 0‐19‐263247‐7] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2005

- Moore RA, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ. Acute pain: individual patient meta‐analysis shows the impact of different ways of analysing and presenting results. Pain 2005;116(3):322‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2006

- Moore A, McQuay H. Bandolier's Little Book of Making Sense of the Medical Evidence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [ISBN: 0‐19‐856604‐2] [Google Scholar]

Morris 1995

- Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for relative risk, odds ratio and standardised ratios and rates. In: Gardner MJ, Altman DG editor(s). Statistics with Confidence ‐ Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines. London: BMJ, 1995:50‐63. [Google Scholar]

PACT 2007

- Anonymous. Prescription Cost Analysis, England 2007. NHS Information Centre, 2007. [ISBN:978‐1‐84636‐210‐1] [Google Scholar]

Pogmore 1980

- Pogmore JR, Filshie GM. Flurbiprofen in the management of dysmenorrhoea. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1980;87(4):326‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Richy 2007

- Richy F, Rabenda V, Mawet A, Reginster JY. Flurbiprofen in the symptomatic management of rheumatoid arthritis: a valuable alternative. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2007;61(8):1396‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roy 2007

- Roy YM, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral lumiracoxib for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006865] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shapiro 1986

- Shapiro SS. Flurbiprofen for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. American Journal of Medicine 1986;80(3A):71‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Toms 2008

- Toms L, McQuay HJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004602.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]