Abstract

Background and purpose

The concept of fast-track surgery has led to a decline in length of stay after total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) to about 2–4 days. However, it has been questioned whether this is only achievable in selected patients—or in all patients. We therefore investigated the role of preoperative pain and functional characteristics in discharge readiness and actual LOS in fast-track THA and TKA.

Methods

Before surgery, hip pain (THA) or knee pain (TKA), lower-extremity muscle power, functional performance, and physical activity were assessed in a sample of 150 patients and used as independent variables to predict the outcome (dependent variable)—readiness for hospital discharge —for each type of surgery. Discharge readiness was assessed twice daily by blinded assessors.

Results

Median discharge readiness and actual length of stay until discharge were both 2 days. Univariate linear regression followed by multiple linear regression revealed that age was the only independent predictor of discharge readiness in THA and TKA, but the standardized coefficients were small (≤ 0.03).

Interpretation

These results support the idea that fast-track THA and TKA with a length of stay of about 2–4 days can be achieved for most patients independently of preoperative functional characteristics.

Over the last decade, length of stay (LOS) with discharge to home after primary THA and TKA has declined from about 5–10 days to about 2–4 days in selected series and larger nationwide series (Malviya et al. 2011, Raphael et al. 2011, Husted et al. 2012, Kehlet 2013, Hartog et al. 2013, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013). However, there is a continuing debate about whether selected patients only or all patients should be scheduled for “fast-track” THA and TKA in relation to psychosocial factors and preoperative pain and functional status (Schneider et al. 2009, Hollowell et al. 2010, Macdonald et al. 2010, Antrobus and Bryson 2011, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013), or whether organizational or pathophysiological factors in relation to the surgical trauma may determine the length of stay (Husted et al. 2011, Husted 2012).

We studied the role of THA and TKA patients’ preoperative pain and functional characteristics in discharge from 2 orthopedic departments with well-established fast-track recovery regimens (Husted et al. 2010).

Methods

Patients and study design

The trial was approved by the regional ethics committee (H-4-2010-FSP2) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2010-41-5561), and was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01248039). Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. The patients were included from 2 comparable Danish fast-track orthopedic departments (Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, and Holstebro University Hospital) (Husted et al. 2010) in the period December 6, 2010 to November 16, 2011. The inclusion criteria were: elective, unilateral primary THA or TKA, age > 18 years, and familiarity with the Danish language. The exclusion criteria were: inability to perform the test procedures preoperatively due to diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, polyneuropathy, or extremity paresis. No other selection of patients took place, except that for logistic reasons it was only possible to include a maximum of 3–6 patients per day. Furthermore, to reduce the risk of selection bias, the person responsible for assigning the patients’ surgical times was kept unaware of the current study.

The total number of patients examined for eligibility was 183 (97 THA and 86 TKA). Of these patients, 28 were excluded (16 of whom were awaiting THA and 12 of whom awaiting TKA): 22 declined to participate and 6 did not speak or understand Danish. The number of patients confirmed to be eligible was 155, and these were included. One patient dropped out after inclusion due to transfer to another hospital department. The case report form was never filled out or was lost in 4 patients, which is why the final sample comprised 150 patients (75 THA and 75 TKA) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics before surgery. Values are mean (SD)

| Variable | THA (n = 75) |

TKA (n = 75) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67 (9.1) | 65 (9.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 (5.0) | 31 (5.2) |

| Gender, (F/M) | 44/31 | 51/24 |

| Leg-press power, W/kg | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.7) |

| Timed up and go, s | 7.9 (0.9) | 9.3 (2.3) |

| HOOS-pain, points | 46 (18) | – |

| HOOS-symptoms, points | 43 (19) | – |

| HOOS-ADL, points | 48(18) | – |

| HOOS-sport/rec, points | 29 (21) | – |

| HOOS-QOL, points | 32 (17) | – |

| KOOS-pain | – | 46 (16) |

| KOOS-symptoms, points | – | 56 (20) |

| KOOS-ADL, points | – | 52 (17) |

| KOOS-sport/rec, points | – | 17 (20) |

| KOOS-QOL, points | – | 30 (17) |

| METtotal, METs | 45 (12) | 43 (12) |

THA: total hip arthroplasty;

TKA: total knee arthroplasty;

BMI: body mass index;

HOOS: hip dysfunction and osteoarthritis outcome score;

KOOS: knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score; MET: metabolic equivalent of task.

Perioperative care

All patients followed a standardized fast-track program for THA and TKA including multidisciplinary education preoperatively, standardized anesthesia and analgesia, standardized surgical technique, and standardized postoperative rehabilitation initiatives (ambulation < 4 h postoperatively) (Husted et al. 2011). Preoperatively, oral gabapentin (600 mg), slow-release paracetamol (2g), and celecoxib (200 mg) (Hvidovre) or todolac (200 mg) (Holstebro) were administered and continued twice daily for 6 days—except for gabapentin, where daily doses were 300 mg plus 600 mg. Surgery was performed under lumbar spinal anesthesia: 12.5 mg isobaric bupivacaine (0.5%) for THA and 7.5 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine (0.5%) for TKA. Additional sedation with propofol (1–5 mg kg-1 h-1) was administered on request. Cefuroxime (1.5 g) and tranexamic acid (1 g) were administered intravenously 15 min before incision. Drains were not used. In THA, a posterior approach was used and in TKA, a medial parapatellar approach was used. Intraoperative local infiltration analgesia (LIA) was used in TKA but not in THA (Kehlet and Andersen 2011). Postoperative rescue analgesia consisted of oral morphine (10 mg); it was administered if VAS > 50 mm at rest.

A standardized postoperative rehabilitation protocol included mobilization—with full weight bearing allowed—using a high-wheeled walker or crutches on the day of surgery. Further standardized physical therapy was given twice a day, including instruction and training of transfer and ambulation techniques. Every session with the physiotherapist was supplemented with information about general fitness training and advice on activities of daily living.

Outcome measures and assessment

The outcome variable was time to meet well-defined functional discharge criteria (discharge readiness): independent ability to get dressed, to get in and out of bed, to sit and rise from a chair/toilet; independence in personal care; mobilization with crutches; and sufficient oral pain treatment (VAS < 50 mm during activity). Discharge criteria were assessed by the ward personnel twice daily, at 0900 h and 1400 h, until discharge; they had no knowledge of the preoperative functional data. Time to meet discharge criteria and time to actual discharge were counted as the number of postoperative days and nights in hospital until fulfillment of the criteria and until discharge, respectively. Thus, the afternoon after surgery was taken as day 0.5, 0900 h on the morning of the first postoperative day was day 1.0, and 1400 h on the same day was day 1.5, and so on.

Experienced assessors who had had extensive procedural training before the study recorded the predictor variables (but not the outcome variable) preoperatively. The predictor variables covered the 3 levels of the WHO International Classification of Functioning (ICF), Disability and Health (Pisoni et al. 2008) (body structure and function, activity, and participation levels). The predictor variables were: leg-press power of the operated leg (Villadsen et al. 2012); performance-based function (“timed up and go” (TUG) (Yeung et al. 2008) and 10-meter fast-speed walking tests (Watson 2002)); pain intensity both at rest and during the measurements of muscle power and performance-based function using a standard 0- to 100-mm mechanical VAS; self-reported level of physical activity expressed as metabolic equivalents (METs) using the physical activity scale (PAS) (Aadahl and Jorgensen 2003, Ainsworth et al. 2011); and self-reported disability related to the hip (the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS) (Nilsdotter et al. 2003) and to the knee (the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) (Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003)).

Statistics

As this was an explorative hypothesis-generating study, no power analysis was done, but we considered 75 THA patients and 75 TKA patients to be sufficient to indicate the impact of preoperative functional characteristics on discharge readiness. All predictor variables were continuous data, except sex, which was categorical.

Because of the relatively large number of potential predictors, univariate linear regression was initially used to examine the influence of each potential predictor variable on the outcome variable (time to meet discharge criteria) for each type of surgery. Variables with p-values of < 0.20 were subsequently included in multiple linear regression models, using hospital discharge readiness as random effect. The outcomes were first investigated for normality, and if required, a (logarithmic or square root) transformation was applied to improve fit. Then the predictors included were tested for significance using stepwise selection. All data analyses were performed with SPSS version 17.0. The level of significance was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

Pain

Mean resting pain before surgery was 20 mm (SD 20) in THA and 22 mm (SD 21) in TKA. Mean pain during the measurement of leg-press power was 30 mm (SD 24) in THA and 33 mm (SD28) in TKA. Mean pain during performance-based function was 29.5 mm (SD 20) in THA and 28 mm (SD 23) in TKA (TUG), and 34 mm (SD 24) in THA and 34 mm (SD 26) in TKA (10-meter fast-speed walking).

Preoperative characteristics and postoperative discharge readiness

All patients reached their endpoint (both discharge readiness and actual discharge). For the THA patients, mean time to discharge (discharge readiness and actual discharge) was 2.0 days (SD 0.8) (range 0.5–6.5) and 1.9 days (SD 1.0) (range 1– 6), respectively. Similarly, for the TKA patients, mean time to discharge (discharge readiness and actual discharge) was 2.3 days (SD 1.0) (range 0.5–7.5) and 3.0 days (SD 1.6) (range 1–12), respectively. For THA, median readiness for discharge was 2 days and actual length of stay was 2 days. The corresponding values for TKA were 2 days and 2 days, respectively.

As mentioned in the Methods section, for some patients discharge readiness could be half a day longer than the actual length of stay, since discharge readiness was assessed at 0900 h and 1400 h whereas length of stay was assessed as number of nights in hospital. Thus, a patient discharge at 1700 h would add another half day to discharge readiness while the actual length of stay was shorter.

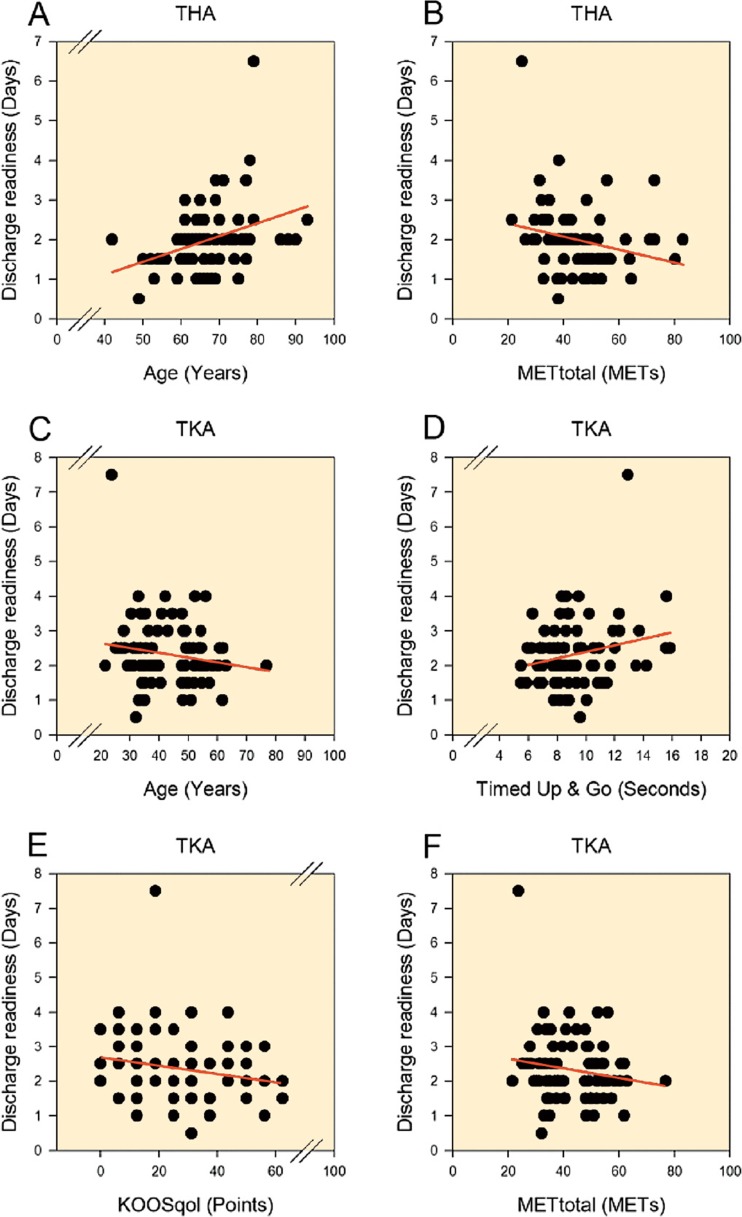

Age and self-reported physical activity were included in the multiple regression model for THA, and age, TUG, KOOS (quality of life subscale, QoL), and self-reported physical activity were included in the model for TKA, as these variables predicted discharge readiness in the univariate analyses (p < 0.2) (Figure). For THA, only age was found to be an independent predictor of discharge readiness (Table 2). Likewise, for TKA age was the only independent predictor of discharge readiness (Table 2). Analyses performed for log-transformed outcomes confirmed the findings above. However, the standardized coefficients for age were small and had limited clinical relevance (Figure). The only 2 outliers with length of stay > 4 days were due to organizational issues (TKA) and observed but unproven pulmonary embolism (THA).

Plots of the initial univariate linear regressions for predictor variables with p-values less than 0.2 for THA (A and B) and TKA (C–F). These predictor variables were subsequently used in the multiple linear regression models.

Table 2.

Multiple regression analyses of discharge readiness, with age, HOOS-pain, and METtotal as predictor variables (THA), and age, Timed up and go, KOOSqol, and METtotal as predictor variables (TKA)

| Variable | β | T-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| THA: Age | 0.03 | 3.2 | 0.002 |

| TKA: Age | 0.02 | 2.3 | 0.03 |

For abbreviations, see Table 1

Discussion

Fast-track surgery has been introduced as a multimodal evidence-based intervention to enhance postoperative recovery and to reduce length of stay and morbidity (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008). Thus, in THA and TKA, length of stay has decreased to 2–4 days with discharge to home in several centers (Malviya et al. 2011, Raphael et al. 2011, Husted et al. 2012, Hartog et al. 2013, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013, Kehlet 2013). Despite these multinational observations, questions still arise as to whether it is possible in all patients or whether it should only be introduced in selected patients. Thus, common arguments for not including patients or not being able to participate in fast-track programs after THA and TKA have included high age, comorbidity, preoperative use of walking aids, psychosocial status, and so on (Raphael et al. 2011). In this context, it should be emphasized that the aim of fast-track surgery is to enhance early postoperative functional recovery by avoiding the usual functional decline (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008) (thereby being independent of preoperative functional status) and to allow early discharge home. Thus, interpretation of studies with selective inclusion criteria but with short length of stay (Raphael et al. 2011, Kirksey et al. 2012) is difficult, especially in studies that have used discharge to a rehabilitation institution (in 30–70% of patients) (Gulotta et al. 2011, den Hertog et al. 2012). Also, interpretation of the role of preoperative factors for length of stay is often hindered by the lack of a well-defined fast-track setup with traditionally longer length of stay (Dall et al. 2009, Schneider et al. 2009, Hollowell et al. 2010, Dauty et al. 2012, den Hertog et al. 2012, Raut et al. 2012, Jonas et al. 2013), or by the fact that length of stay, as opposed to discharge readiness, is influenced by logistical factors (e.g. waiting for an X-ray).

We therefore conducted this study within well-established fast-track orthopedic departments from which patients are discharged to their own homes (Husted et al. 2011, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013), in order to investigate the role of preoperative functional data for patients who are able to achieve early discharge criteria and discharge to home. The preoperative characterization of functional criteria included the usual patient characteristics (age, sex, etc.; Table 1) as well as outcomes covering all 3 levels of the WHO ICF model.

Our preoperative patient characteristics in fast-track THA and TKA corresponded to previous trials (Kehlet 2013, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013, Hartog et al. 2013). However, within the well-established methodology (Husted et al. 2011), the preoperative patient characteristics including functional characteristics had a limited influence on discharge readiness—although age had a small statistically significant effect, but with limited clinical consequences. Thus, in a large prospective study median length of stay was 3 days, increasing to 4 days in patients ≥ 86 years of age. Consequently, old age per se should not prevent these patients from being treated in a fast-track program (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013). These results support the idea that a fast-track setup with short length of stay can be achieved with minimal influence on the patient’s preoperative activity level by using an optimized multimodal opioid-sparing pain treatment, early mobilization, and intensive preoperative information (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008, Kehlet 2013).

Our results may have important clinical implications, since they suggest that unselected patients undergoing elective primary THA or TKA can be included in the well-defined fast-track programs allowing early restoration of function and discharge. This is further supported by the demonstration in larger series that this approach is safe with no increase (or in fact a slight decrease) in morbidity and no increase in re-admissions (Hunt et al. 2009, Malviya et al. 2011, Hartog et al. 2013, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013, Kehlet 2013). Nevertheless, despite the lack of significance between achieving early discharge and preoperative functional characteristics, some patients may need to stay a little longer for other reasons such as pain, orthostatic intolerance/dizziness, general (muscle) weakness, or organizational factors (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008, Kehlet 2013) calling for further large prospective studies to define the pathogenic mechanisms of these factors and potential for future interventions. In this context, the possible beneficial role of prehabilitation in THA and TKA in length of stay requirements needs to be reassessed with the fast-track methodology (Gill and McBurney 2013, Villadsen et al. 2014). The same applies to different analgesic interventions (Bernucci and Carli 2012, Lunn and Kehlet 2013) or type of in-hospital physiotherapy and possibilities for early postoperative strength training (Bandholm and Kehlet 2012). Also, organizational factors such as the weekday of operation or waiting for a transfusion need to be considered (Husted et al. 2008, Husted 2012).

In conclusion, our findings support the idea that fast-track THA and TKA with early discharge to home can be achieved in almost all patients. Thus, early discharge (length of stay of about 2 days) was achieved independently of preoperative functional characteristics, although age had a small but clinically limited effect in prolonging length of stay. These results may have important implications for improvement of recovery in all THA and TKA patients independently of preoperative “high-risk” characteristics (Kehlet and Mythen 2011, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013).

Acknowledgments

All the authors contributed to design of the study, analysis, and writing and approval of the manuscript. BH and PKA performed or supervised the functional assessments.

We thank physiotherapists Lis Møller Kristensen and Maria Ipsen and nurses Britta Pape and Pernille Staal Thiesen of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at Holstebro Hospital and the nurses of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at Hvidovre Hospital for their assistance related to performing this investigation.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aadahl M, Jorgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity . Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(7):1196–202. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074446.02192.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR, Jr., Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt-Glover MC, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values . Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–81. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antrobus JD, Bryson GL. Enhanced recovery for arthroplasty: good for the patient or good for the hospital? . Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(10):891–6. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandholm T, Kehlet H. Physiotherapy exercise after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty: time for reconsideration? . Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(7):1292–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernucci F, Carli F. Functional outcome after major orthopedic surgery: the role of regional anesthesia redefined . Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25(5):621–8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328357a3d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall GF, Ohly NE, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. The influence of pre-operative factors on the length of in-patient stay following primary total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a multivariate analysis of 2302 patients . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(4):434–40. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B4.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauty M, Schmitt X, Menu P, Rousseau B, Dubois C. Using the Risk Assessment and Predictor Tool (RAPT) for patients after total knee replacement surgery . Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;55(1):4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog A, Gliesche K, Timm J, Muhlbauer B, Zebrowski S. Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SD, McBurney H. Does exercise reduce pain and improve physical function before hip or knee replacement surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1):164–76. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.08.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulotta LV, Padgett DE, Sculco TP, Urban M, Lyman S, Nestor BJ, Fast track THR. One hospital’s experience with a 2-day length of stay protocol for total hip replacement . HSS J. 2011;7(3):223–8. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartog YM, Mathijssen NM, Vehmeijer SB. Reduced length of hospital stay after the introduction of a rapid recovery protocol for primary THA procedures . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(5):444–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.838657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollowell J, Grocott MP, Hardy R, Haddad FS, Mythen MG, Raine R. Major elective joint replacement surgery: socioeconomic variations in surgical risk, postoperative morbidity and length of stay . J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(3):529–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GR, Crealey G, Murthy BV, Hall GM, Constantine P, O’Brien S, Dennison J, Keane P, Beverland D, Lynch MC, Salmon P. The consequences of early discharge after hip arthroplasty for patient outcomes and health care costs: comparison of three centres with differing durations of stay . Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(12):1067–77. doi: 10.1177/0269215509339000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects . Acta Orthopaedica (Suppl 346) 2012;83:2–38. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.700593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):168–73. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Solgaard S, Hansen TB, Soballe K, Kehlet H. Care principles at four fast-track arthroplasty departments in Denmark . Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(7):A4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Lunn TH, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(6):679–84. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jensen CM, Solgaard S, Kehlet H. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009: from research to implementation . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):101–4. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas SC, Smith HK, Blair PS, Dacombe P, Weale AE. Factors influencing length of stay following primary total knee replacement in a UK specialist orthopaedic centre . Knee. 2013;20(5):310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen CC, Kehlet H. Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(6):972–80. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1600–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Andersen LO. Local infiltration analgesia in joint replacement: the evidence and recommendations for clinical practice . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(7):778–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Mythen M. Why is the surgical high-risk patient still at risk? . Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(3):289–91. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery . Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):189–98. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817f2c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirksey M, Chiu YL, Ma Y, Della Valle AG, Poultsides L, Gerner P, Memtsoudis SG. Trends in in-hospital major morbidity and mortality after total joint arthroplasty: United States 1998-2008 . Anesth Analg. 2012;115(2):321–7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825b6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn TH, Kehlet H. Perioperative glucocorticoids in hip and knee surgery - benefit vs. harm? A review of randomized clinical trials . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(7):823–34. doi: 10.1111/aas.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald V, Ottem P, Wasdell M, Spiwak P. Predictors of prolonged hospital stays following hip and knee arthroplasty. Intl J Ortho Trauma Nursing. 2010;14(4):198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, Muller SD, Emmerson KP, Partington PF, Reed MR. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(5):577–81. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.618911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M, Roos EM. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)—validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement . BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni C, Giardini A, Majani G, Maini M. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets for osteoarthritis. A useful tool in the follow-up of patients after joint arthroplasty . Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(4):377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael M, Jaeger M, van Vlymen J. Easily adoptable total joint arthroplasty program allows discharge home in two days . Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(10):902–10. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raut S, Mertes SC, Muniz-Terrera G, Khanduja V. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay following a total knee replacement in patients aged over 75 . Int Orthop. 2012;36(8):1601–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos EM, Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement . Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Kawahara I, Ballantyne G, McAuley C, Macgregor K, Garvie R, McKenzie A, MacDonald D, Breusch SJ. Predictive factors influencing fast track rehabilitation following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(12):1585–91. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0825-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen A, Roos EM, Overgaard S, Holsgaard-Larsen A. Agreement and reliability of functional performance and muscle power in patients with advanced osteoarthritis of the hip or knee . Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(5):401–10. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182465ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen A, Overgaard S, Holsgaard-Larsen A, Christensen R, Roos EM. Postoperative effects of neuromuscular exercise prior to hip or knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial . Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1130–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson MJ. Refining the ten-metre walking test for use with neurologically impaired people. Physiotherapy. 2002;88(7):386–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung TS, Wessel J, Stratford PW, MacDermid JC. The timed up and go test for use on an inpatient orthopaedic rehabilitation ward . J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(7):410–7. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]