Abstract

Background

The overall incidence of fractures has been addressed in several studies, but there are few data on different types of fractures that require inpatient care, even though they account for considerable healthcare costs. We determined the incidence of limb and spine fractures that required hospitalization in people aged ≥ 16 years.

Patients and methods

We collected data on the diagnosis (ICD10 code), procedure code (NOMESCO), and 9 additional characteristics of patients admitted to the trauma ward of Central Finland Hospital between 2002 and 2008. Incidence rates were calculated for all fractures using data on the population at risk.

Results and interpretation

During the study period, 3,277 women and 2,708 men sustained 3,750 and 3,030 fractures, respectively. The incidence of all fractures was 4.9 per 103 person years (95% CI: 4.8–5.0). The corresponding numbers for women and men were 5.3 (5.1–5.4) and 4.5 (4.3–4.6). Fractures of the hip, ankle, wrist, spine, and proximal humerus comprised two-thirds of all fractures requiring hospitalization. The proportion of ankle fractures (17%) and wrist fractures (9%) was equal to that of hip fractures (27%). Four-fifths of the hospitalized fracture patients were operated. In individuals aged < 60 years, fractures requiring hospitalization were twice as common in men as in women. In individuals ≥ 60 years of age, the opposite was true.

Inpatient hospital treatment of fractures is significantly more expensive than outpatient fracture treatment (Cummings and Melton 2002). In most cases, the costs are increased if surgery is needed (Bouee et al. 2006). Thus, preventing fractures that commonly require surgical treatment is cost effective. However, except for hip fractures, there has been little research on the incidence of fractures requiring inpatient care, and the current profile of fractures sustained by adults admitted to trauma units is unknown. This profile is likely to differ from the overall fracture profile in a population. We determined the incidence of limb and spine fractures that require hospitalization in individuals aged ≥ 16 years.

Patients and methods

All patients at least 15 years of age attending the trauma ward of Central Finland Hospital (CFH), Jyväskylä, Finland, between 2002 and 2008 were included in the study. CFH is a public hospital providing traumatological treatment to a population of 250,000, which is approximately 5% of the Finnish population. Fracture patients living in the catchment area of the hospital district who are in need of surgical treatment are referred to CFH. Fracture patients were hospitalized according to the severity of the fracture or the characteristics of the patient (e.g. general condition, age, or comorbidities). The social security number, municipality, diagnosis (ICD 10 code, Table), procedure code (NOMESCO), code of external cause (ICD 10), side of injury, time of arrival at the emergency department, and ward were recorded in a registry including every patient attending the trauma ward. Weber’s classification of ankle fractures and the Gustilo classification of open fractures were used (Gustilo et al. 1984, Malek et al. 2006). Complications during treatment were recorded.

Incidence of fractures in the study population

| Fracture | Diagnosis code (ICD10) | n | Mean patient age (SD) | Annual rate/1,000 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip | S72.0, S72.1, S72.2 | 1,829 | 79 (12) | 1.31 (1.25–1.37) |

| Ankle | S82.5, S82.6, S82.8 | 1,154 | 51 (17) | 0.83 (0.78–0.88) |

| Radius/ulna, distal | S52.5, S52.6, S52.8 | 617 | 60 (18) | 0.44 (0.41–0.48) |

| Spine | S12, S22.0, S22.1, S32.0 | 381 | 49 (20) | 0.27 (0.25–0.30) |

| Humerus, proximal | S42.2 | 358 | 64 (16) | 0.26 (0.23–0.28) |

| Tibia, distal | S82.3 | 204 | 51 (18) | 0.15 (0.13–0.17) |

| Forearm, proximal | S52.0, S52.1 | 200 | 55 (20) | 0.14 (0.12–0.16) |

| Femur, diaphysis | S72.3 | 190 | 64 (25) | 0.14 (0.12–0.16) |

| Tibia, diaphysis | S82.2 | 186 | 45 (17) | 0.13 (0.11–0.15) |

| Clavicle | S42.0 | 177 | 44 (18) | 0.13 (0.11–0.15) |

| Tibia, proximal | S82.1 | 173 | 55 (18) | 0.12 (0.11–0.14) |

| Finger phalanx | S62.5, S62.6, S62.7 | 135 | 44 (16) | 0.10 (0.08–0.11) |

| Femur, distal | S74.2 | 121 | 69 (20) | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) |

| Humerus, distal | S42.3 | 119 | 61 (22) | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) |

| Patella | S82.0 | 115 | 57 (19) | 0.08 (0.07–0.10) |

| Shaft of forearm | S52.2, S52.3, S52.4 | 109 | 48 (20) | 0.08 (0.06–0.09) |

| Metacarpal | 62.2, S62.3, S62.4 | 106 | 41 (18) | 0.08 (0.06–0.09) |

| Fibula (malleolus excluded) | S82.4 | 95 | 44 (15) | 0.07 (0.06–0.08) |

| Humerus, diaphysis | S42.3 | 94 | 59 (21) | 0.07 (0.05–0.08) |

| Calcaneus | S92.0 | 82 | 45 (14) | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) |

| Metatarsal | S92.3 | 80 | 45 (17) | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) |

| Acetabulum | S32.4 | 66 | 60 (23) | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) |

| Pelvis | S32.1, S32.3, S32.5 | 63 | 60 (24) | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) |

| Scapula | S42.1 | 49 | 54 (16) | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) |

| Toe phalanx | S92.4, S92.5 | 27 | 45 (15) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Carpus | S62.0, S62.1 | 25 | 42 (19) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Talus | S92.1 | 21 | 35 (13) | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) |

| Midfoot a | S92.2 | 12 | 38 (13) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

Some patients had records of repeated visits to the ward because of a similar fracture. All visits occurring within 2 months of the primary visit were regarded as being associated with additional treatment of the primary fracture. Repeat visits occurring later after the primary fracture were frequently recognized as being associated with the primary fracture by reviewing the records for secondary diagnoses, procedure codes, and complications. For the remaining cases, new fractures were distinguished from further treatment of a primary fracture by scrutinizing medical records, radiologist reports, and radiographs.

Statistics

Data on the population living in the CFH catchment area during 2002–2008 were obtained from Statistics Finland. The fracture patients and the population at risk were stratified by age and sex. In the Results section, the age of patients is presented as mean (SD) if not otherwise stated. The annual mean population sizes were used to assess the number of person years. Fracture incidence rates (per 103 person years) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Crude and standardized (age and sex) estimates of fracture incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated using Poisson regression models, or negative binomial regression models when appropriate. Assumption of overdispersion in the Poisson model was tested using the Lagrange multiplier test.

Results

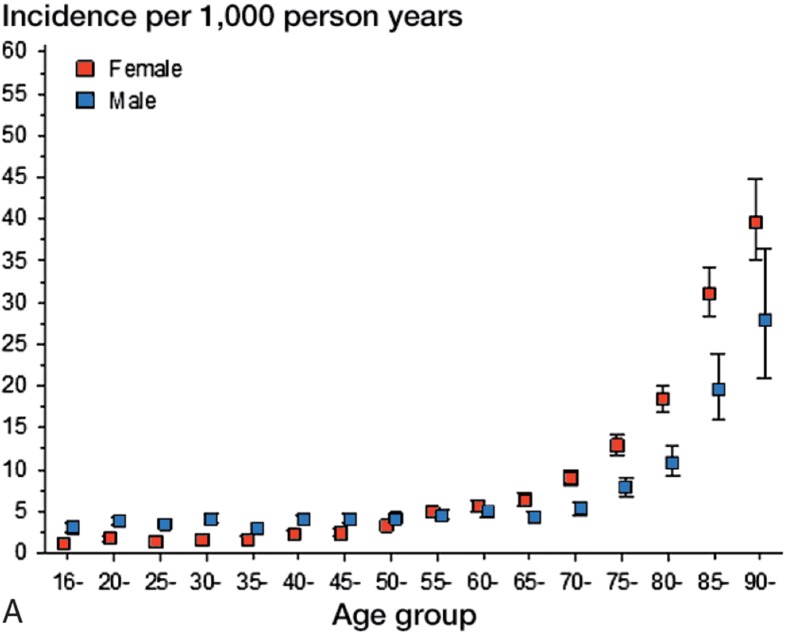

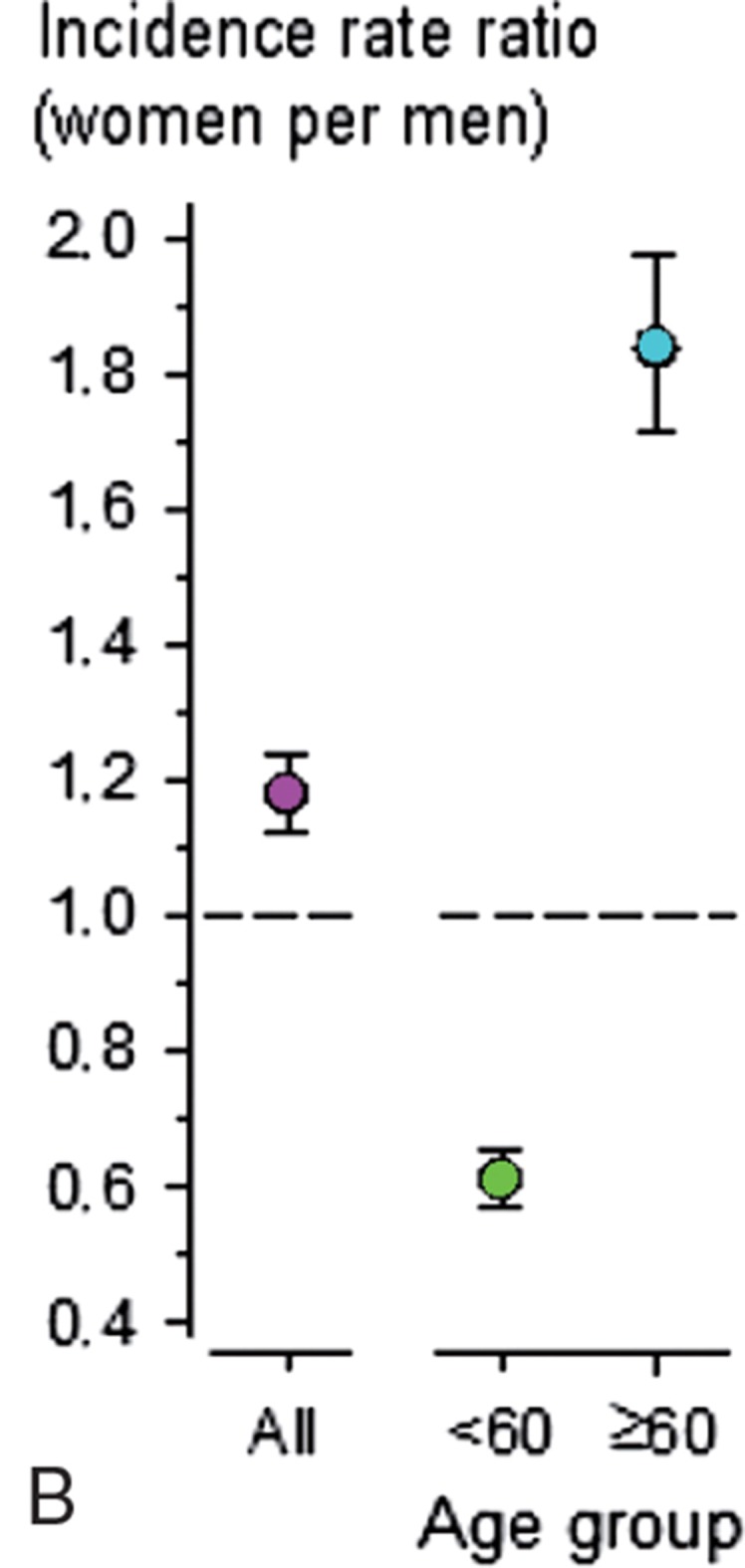

Between 2002 and 2008, 3,277 women sustained 3,758 fractures and 2,708 men sustained 3,030 fractures. At the time of the fracture, the mean age of the patients was 60 (SD 21) years. Female fracture patients were generally older than male patients (mean 67 (SD 19) vs. 51 (SD 20) years; p < 0.001). 69% of women and 35% of men were over 60 years of age. In 82% of the admissions, the patients were operated. The total incidence of all fractures was 4.9 per 103 person years (CI: 4.8–5.0). The corresponding numbers for women and men were 5.3 (CI: 5.1–5.4) and 4.5 (CI: 4.3–4.6), respectively. In women, the incidence of fractures increased steadily until the age of 60 years, and exponentially thereafter. In men, the pattern of fracture incidence was similar to that for women, but the phase of exponential growth started 10 years later (Figure 1A). The incidence of all fractures in women and men younger than 60 years of age was 2.3 (CI: 2.2–2.5) and 12.0 (CI: 11.5–12.5). The corresponding numbers for women and men aged 60 years and older were 3.8 (CI: 3.7–4.0) and 6.5 (CI: 6.1–6.9). Hip, ankle, wrist, and spine were the most common fracture locations (Figure 2). The age-adjusted IRR for all fractures was 1.0 (CI: 0.9–1.0; p = 0.2). In the younger age group, fractures were twice as common in men as in women (Figure 1B). In the older age group, the opposite was true.

Figure 1A.

The crude incidence of fractures per 1,000 person years by age. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

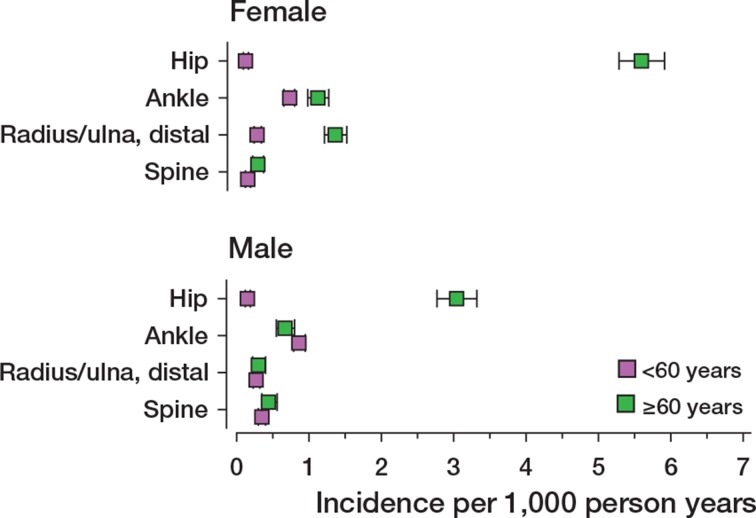

Figure 2.

Incidence of the 4 most commonly treated fractures in men and women who were younger and older than 60 years of age.

Figure 1B.

The incidence rate ratios in women relative to men for all fractures. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Fractures of the hip, ankle, wrist, spine, and proximal humerus were the 5 most common ones and comprised 64% of all fractures requiring hospitalization (Table). Hip fractures were generally sustained by older individuals (78 (SD 11) years) than wrist fractures (59 (SD17) years) and proximal humeral fractures (64 (SD 16) years). Of the 5 most commonly treated fractures, ankle fractures and vertebral fractures generally occurred in people who were younger (50 (SD 16) years and 49 (SD 20) years, respectively).

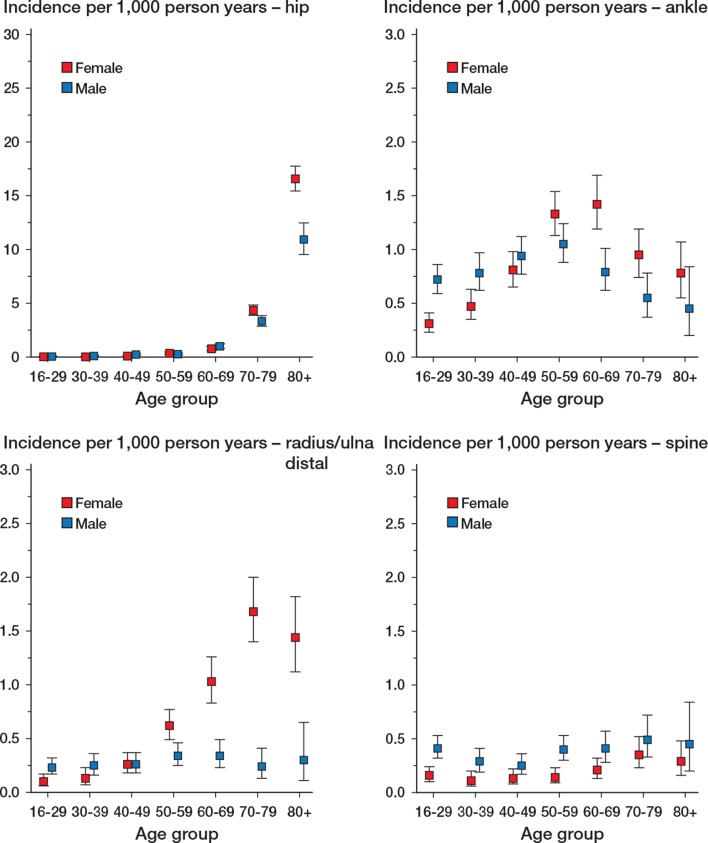

Hip fractures were rare in individuals less than 60 years of age. After this age, the incidence rate of hip fractures rose exponentially in both women and men, but they were more prominent in women. In individuals over 50 years of age, hip fractures accounted for 40% of all fractures in women and 33% of all fractures in men. The distribution of ankle fractures was similar in both sexes. The incidence peaked in women aged 60–69 years and in men aged 50–59 years. The incidence rate of wrist fractures was higher in postmenopausal women, whereas the incidence rate did not show an age-related increase in men. The incidence of spine fractures was approximately twice as high for men than for women in all age groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age- and sex-specific incidence of the 4 most commonly treated fractures requiring hospitalization. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

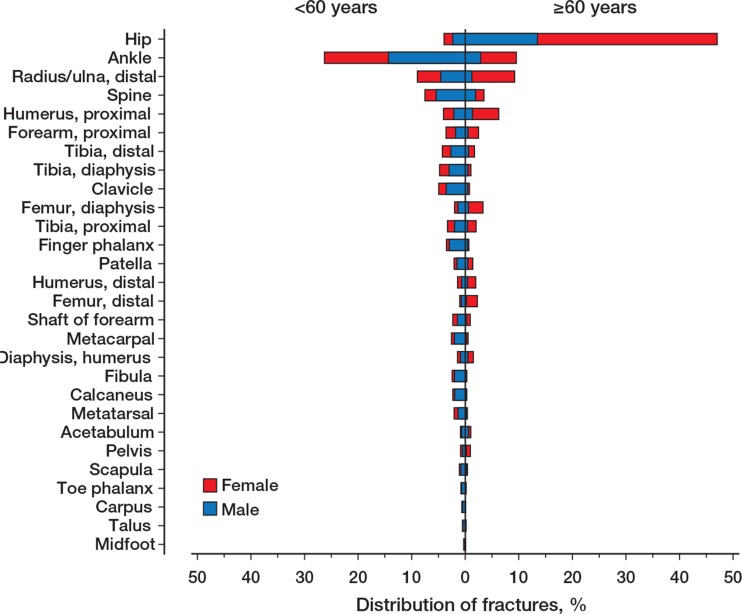

Hip fractures constituted almost half of all fractures in individuals aged 60 years of age or older. Two-thirds of these elderly hip fracture patients were women. Ankle and wrist fractures were the second and third most common fractures in this age group, each constituting approximately 10% of fractures (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of fractures between women and men who were younger and older than 60 years of age.

Ankle fractures were the most frequently treated fractures in individuals less than 60 years of age, and they constituted more than one quarter of all fractures in this age group. Most of these ankle fracture patients were men. The second and third most common fractures in this younger age group were wrist fractures and fractures of the spine. Each of these fracture types constituted less than 10% of all fractures requiring hospitalization in this age group (Figure 4).

Discussion

We assessed the incidence of spine and limb fractures requiring hospitalization in a representative sample consisting of almost 7,000 treatment periods. Different fractures showed a remarkably different age- and sex-specific distribution. Hip fractures represented 27% of all treatment periods. Ankle fractures represented a substantially larger proportion (17%) of all hospitalized fractures than previous research had shown (5%) (Garraway et al. 1979). In addition, the combined incidence of ankle and wrist fractures was as high as that of hip fractures. Hip, ankle, wrist, spine, and proximal humeral fractures comprised two thirds of all fractures. There have been few studies on the incidence of all kinds of hospitalized limb and spine fractures sustained by adults. 2 studies concentrated on fractures sustained by individuals in a specific age group (Knowelden et al. 1964, Johnell et al. 2005). 2 studies described the hospitalized patients briefly (Singer et al. 1998, Melton et al. 1999) and another study addressed certain types of fractures (Tarantino et al. 2010). We know of only one previous paper addressing all hospitalized limb fractures in adults of all ages, but it was written in the 1970s (Garraway et al. 1979). The indications and methods of fracture treatment have changed markedly since that time.

Many epidemiological studies have focused on the overall incidence of fractures (Donaldson et al. 1990, Singer et al. 1998, Cooley and Jones 2001, Court-Brown and Caesar 2006). According to the literature, fractures of the distal radius, metacarpals, hip, finger phalanx, and ankle are the most common types (Court-Brown and Caesar 2006). This fracture profile is remarkably different from that for hospitalized fracture patients. In our sample we found that hip, ankle, spine, wrist, and proximal humerus fractures were the fractures that most frequently required hospital admission. This is in agreement with results from a Swedish study on individuals who were over 50 years of age (Johnell et al. 2005).

Most hip fracture patients are hospitalized, whereas most other fractures are treated at outpatient clinics or day surgery units (Tarantino et al. 2010). Thus, in a hospital registry of inpatients, only the incidence of hip fractures closely resembles the incidence of fracture type at the population level. The incidence of hip fractures in the present study was similar to the national incidence and the European incidence (Kannus et al. 2006, Cheng et al. 2011). However, we found that hip fractures accounted for 40% of all fractures in women and 33% of all fractures in men over 50 years of age. This proportion is lower than in the Swedish population (where 72% of women and 63% of men are over 50 years of age) (Johnell et al. 2005). In all patients, hip fractures accounted for one quarter of all fractures, which is in concordance with a previous study from the USA (Garraway et al. 1979).

The overall incidence of spine fractures is higher in postmenopausal women than in men of the same age (Cummings and Melton 2002, Johnell and Kanis 2005). In the patients in our study who required hospitalization, the incidence of spine fractures in men was nearly twice as high as that in women, in all age groups. A Swedish study found similar results for surgically treated thoracolumbar fractures (Jansson et al. 2010). An Iranian epidemiological study on traumatic spine fractures found a smaller difference in the incidence of fractures in older men and women (Moradi-Lakeh et al. 2011).

Inpatient hospital treatment of fractures is much more expensive than outpatient fracture treatment (Cummings and Melton 2002). In most cases, the costs are higher if surgery is needed (Bouee et al. 2006). Thus, prevention of fractures that commonly require surgical treatment is cost effective. With the exception of ankle fractures, all of the top 5 fractures requiring hospitalization are regarded as osteoporotic fractures, the incidence of which rises in older age groups (Kanis et al. 2001). A proportion of these fractures could be prevented by effectively preventing falls and treating osteoporosis.

The most important reasons for admission are likely to be the type and severity of the fracture and the need for operative treatment. In our study, operative treatment was required in 82% of the fracture cases admitted to the trauma ward. Other causes for trauma ward admissions may include concomitant injuries requiring surgical inpatient care, demanding analgesic treatment, advancing age, and severe comorbidity (Johansen et al. 1998). However, at the population level most fractures are treated nonoperatively (Court-Brown et al. 2010).

In most cases, only a few types of fractures—such as femoral fractures and fractures of the tibial shaft—are treated operatively. In our material, unstable ankle fractures (bi- or trimalleolar fractures or those that are unstable on clinical or radiographic examination) were operated. Distal radius fractures were treated operatively when, after attempted closed reposition, the dorsal or volar radial tilt was more than 10 or 20 degrees, respectively. Surgery was also undertaken if the diastasis of fracture fragments on the joint surface was over 2 mm, or if the radius was shortened by over 5 mm. These guidelines remained unchanged during the study period. Generally, vertebral fractures were treated surgically if the angle of kyphosis progressed to exceed 30 degrees, or if the fracture was defined as unstable. The interpretation of instability changed during the study period towards more conservative management. At the beginning, vertebral fractures were usually defined as unstable if both the anterior and middle columns were affected. During the latter half of the study period, the fracture was considered stable if the posterior structures were intact.

There may be some variation between our data and the national fracture-specific estimates. Our numbers on the incidence of hospitalized proximal humeral fractures among patients ≥ 60 years of age were less than in the whole of Finland (106 vs. 129 in women and 29 vs. 48 in men per 105 individuals) (Palvanen et al. 2006). The same variation was true for the incidence of ankle fractures (143 vs. 173 in women and 84 vs. 100 in men) (Kannus et al. 2008). A Finnish study on surgically treated distal radius fractures found slightly lower incidence rates per 105 individuals (69 in women and 24 in men, as opposed to our findings of 78 in women and 37 in men) (Mattila et al. 2011). However, the age groups in that study differed from those in the present study.

An advantage of our study is that we differentiated between re-fractures and visits related to additional treatment of a previous fracture. We regarded multiple ward visits for a similar fracture within 2 months of the first visit as being part of the treatment of the primary fracture. Our cutoff period of 2 months was short. In addition, we manually evaluated every case of re-admission for the same diagnosis more than 2 months after the primary fracture. Thus, we probably identified re-fractures reliably.

Another advantage of our study was that most fracture patients in need of specialized traumatological treatment in the Central Finland Healthcare District are referred to CFH. Thus, our records would have included almost all the patients who lived in the catchment area of CFH and who presented with a serious fracture. We cannot exclude the possibility of some missing diagnoses or inaccurate entries in the registry. However, a study on hip fractures between 2002 and 2003 at CFH, based on different records, found a similar incidence of hip fractures to that in the present study (Lönnroos et al. 2006). Thus, our data are most probably reliable.

In conclusion, hip and ankle were the two most common fracture sites constituting nearly half of all fractures requiring hospitalization. Notably, the ankle fractures play a more important role in a trauma unit than previously believed. In younger people, fractures are twice as common in men as in women. In older people, the opposite is true.

Acknowledgments

AS: design of study, interpretation of data, and writing of manuscript. JP: design of study, interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript. HK: design of study, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript. EL and MH: interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript. IK: acquisition of data, design of study, interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript.

We thank Dr Jukka Nyrhinen, Ms Riitta Minkkinen, Ms Mari Järvinen, and the staff of the traumatology ward of Central Finland Hospital for their persistent and invaluable help in recording the data for the trauma registry. This work was supported by a TEVO grant from Central Finland Hospital.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Bouee S, Lafuma A, Fagnani F, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY. Estimation of direct unit costs associated with non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures in five european countries . Rheumatol Int. 2006;26(12):1063–72. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SY, Levy AR, Lefaivre KA, Guy P, Kuramoto L, Sobolev B. Geographic trends in incidence of hip fractures: A comprehensive literature review . Osteoporosis Int. 2011;22(10):2575–86. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1596-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley H, Jones G. A population-based study of fracture incidence in southern tasmania: Lifetime fracture risk and evidence for geographic variations within the same country . Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(2):124–30. doi: 10.1007/s001980170144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review . Injury. 2006;37(8):691–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court-Brown CM, Aitken S, Hamilton TW, Rennie L, Caesar B. Nonoperative fracture treatment in the modern era . J Trauma. 2010;69(3):699–707. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b57ace. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures . Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1761–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson LJ, Cook A, Thomson RG. Incidence of fractures in a geographically defined population . J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990;44(3):241–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.44.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway WM, Stauffer RN, Kurland LT, O’Fallon WM. Limb fractures in a defined population. II. orthopedic treatment and utilization of health care . Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54(11):708–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: A new classification of type III open fractures . J Trauma. 1984;24(8):742–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson KA, Blomqvist P, Svedmark P, Granath F, Buskens E, Larsson M, Adami J. Thoracolumbar vertebral fractures in sweden: An analysis of 13,496 patients admitted to hospital . Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(6):431–7. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9461-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen A, Evans R, Bartlett C, Stone M. Trauma admissions in the elderly: How does a patient’s age affect the likelihood of their being admitted to hospital after a fracture? . Injury. 1998;29(10):779–84. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures . Osteoporos Int (Suppl 2) 2005;16:S3–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnell O, Kanis JA, Jonsson B, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C. The burden of hospitalised fractures in sweden . Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(2):222–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A. The burden of osteoporotic fractures: A method for setting intervention thresholds . Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(5):417–27. doi: 10.1007/s001980170112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Vuori I, Jarvinen M. Nationwide decline in incidence of hip fracture . J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(12):1836–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannus P, Palvanen M, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Jarvinen M. Stabilizing incidence of low-trauma ankle fractures in elderly people finnish statistics in 1970-2006 and prediction for the future . Bone. 2008;43(2):340–2. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowelden J, Buhr AJ, Dunbar O. Incidence of fractures in persons over 35 years of age.a report to the m.r.c. working party on fractures in the elderly . Br J PrevSoc Med. 1964;18:130–41. doi: 10.1136/jech.18.3.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroos E, Kautiainen H, Karppi P, Huusko T, Hartikainen S, Kiviranta I, Sulkava R. Increased incidence of hip fractures. A population based-study in finland . Bone. 2006;39(3):623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek IA, Machani B, Mevcha AM, Hyder NH. Inter-observer reliability and intra-observer reproducibility of the weber classification of ankle fractures . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88(9):1204–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B9.17954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila VM, Huttunen TT, Sillanpaa P, Niemi S, Pihlajamaki H, Kannus P. Significant change in the surgical treatment of distal radius fractures: A nationwide study between 1998 and 2008 in finland . J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care. 2011;71(4):939–42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182231af9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton LJ, 3rd, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Fracture incidence in olmsted county, minnesota: Comparison of urban with rural rates and changes in urban rates over time . Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(1):29–37. doi: 10.1007/s001980050113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi-Lakeh M, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR, Saadat S, Zarei MR, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Burden of traumatic spine fractures in tehran, iran . BMC Public Health. 2011;11:789. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Update in the epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures . Clin Orthop. 2006;442:87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194672.79634.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: The influence of age and gender . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998;80(2):243–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b2.7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino U, Capone A, Planta M, D’Arienzo M, Letizia Mauro G, Impagliazzo A, Formica A, Pallotta F, Patella V, Spinarelli A, et al. The incidence of hip, forearm, humeral, ankle, and vertebral fragility fractures in italy: Results from a 3-year multicenter study . Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(6):R226. doi: 10.1186/ar3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]