Abstract

The neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and subtypes of GABA receptors were recently identified in adult testes. Since adult Leydig cells possess both the GABA biosynthetic enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), as well as GABAA and GABAB receptors, it is possible that GABA may act as auto-/paracrine molecule to regulate Leydig cell function. The present study was aimed to examine effects of GABA, which may include trophic action. This assumption is based on reports pinpointing GABA as regulator of proliferation and differentiation of developing neurons via GABAA receptors. Assuming such a role for the developing testis, we studied whether GABA synthesis and GABA receptors are already present in the postnatal testis, where fetal Leydig cells and, to a much greater extend, cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage proliferate. Immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR, Western blotting and a radioactive enzymatic GAD assay evidenced that fetal Leydig cells of five-six days old rats possess active GAD protein, and that both fetal Leydig cells and cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage possess GABAA receptor subunits. TM3 cells, a proliferating mouse Leydig cell line, which we showed to possess GABAA receptor subunits by RT-PCR, served to study effects of GABA on proliferation. Using a colorimetric proliferation assay and Western Blotting for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) we demonstrated that GABA or the GABAA agonist isoguvacine significantly increased TM3 cell number and PCNA content in TM3 cells. These effects were blocked by the GABAA antagonist bicuculline, implying a role for GABAA receptors. In conclusion, GABA increases proliferation of TM3 Leydig cells via GABAA receptor activation and proliferating Leydig cells in the postnatal rodent testis bear a GABAergic system. Thus testicular GABA may play an as yet unrecognized role in the development of Leydig cells during the differentiation of the testicular interstitial compartment.

Background

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate central nervous system. In addition to its well established function as neurotransmitter, locally synthesized GABA and GABA receptors are also present in endocrine organs, for example, in somatotrophs (GH-producing cells) of the anterior pituitary lobe [1-3] and in pancreatic islet cells [4-6]. In both endocrine tissues GABA is regulating the synthesis and the release of hormones. The release of glucagon and growth hormone was shown to be controlled by GABA in an auto-/paracrine manner.

In our previous work we recently identified another GABAergic system located in adult Leydig cells in rodent and human testis [7]. Since Leydig cells possess both isoforms of the GABA synthesizing enzyme glutamate decarboxylase, GAD65 and GAD67, vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT), as well as several GABAA and GABAB receptor subunits, GABA may act as an auto-/paracrine molecule regulating Leydig cell function. Some evidence for a role in release of testosterone came from pharmacological studies in rat Leydig cells, which respond to GABAergic stimulation with increased testosterone production [8,9]. What other roles GABA may have in endocrine Leydig cells and which GABA receptors are mediating these actions are not known.

In the central nervous system evidence for a non-synaptic, trophic role of GABA in neurogenesis during embryonic development is mounting [10-15]. Thus GABA stimulates progenitor cells to proliferate in different regions of the developing brain [16-20]. Since these neuronal progenitor cells are also capable of synthesizing GABA and possess GABA receptors, GABA executes this trophic function in an auto-/paracrine fashion [21]. Further non-synaptic actions of GABA in the developing brain that are evolving include regulation of migration and motility of embryonic neurons [22-24]. While in general, cellular responses to GABA are mediated through GABAA, GABAB and GABAC receptors and the intracellular signaling pathways associated with them [25], in respect to both cell proliferation and migration in the developing brain, contribution of GABAA receptors was reported [18,19,21,26,27]. Thus, although its precise regulation may depend on the region and cell type affected, GABA emerges as an important signal for cell proliferation and migration.

In view of this role of GABA in the brain, the question arises, whether GABA may influence cell proliferation processes in the testis, for example in Leydig cells, which bear GABA receptors [7]. In the testis of adult mammals, however, Leydig cells have only a marginal turnover rate and show low mitotic activity [28-30]. Due to the fact that Leydig cells in postnatal testis proliferate to a much greater extend than in adult testis [31-35], we sought to study postnatal testes of mice and rats at age of five-six days after birth. At this point of development two distinct types of Leydig cells are found, namely steroidogenic fetal Leydig cells with a typical rounded morphology clustered together in groups and spindle-shaped mesenchymal precursor cells of adult Leydig cells, which are located primarily in peritubular regions. The latter are not able to synthesize steroids, but are strongly proliferating and differentiate to Leydig progenitor cells during the second postnatal week in rodents [36-38]. Fetal Leydig cells may also increase in number during postnatal development, albeit to a smaller degree [31,39]. Thus, the endocrine compartment of postnatal testis bears developing and highly proliferating cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage. Therefore, in this study we addressed the questions whether a local GABAergic system is present in postnatal testis and may be involved in proliferation of Leydig cells.

Methods

Animals

Testes and other tissues were obtained from adult, 3–6 months old (n = 12; Sprague-Dawley, Wistar) and five-six days old male rats (n = 14; Sprague-Dawley), as well as from adult (n = 4; BALB/c) male mice, which were bred at the Technische Universität München, Germany. Testes were also obtained from five-six days old male mice (n = 9; BALB/c), which were bred at the Instituto de Biología y Medicina Experimental, Buenos Aires, Argentina. According to the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, they were painlessly killed under ether anesthesia by exsanguinations and organs were rapidly removed. Testes were either frozen until isolation of mRNA and preparation for GAD activity measurements, or fixed in Bouin's solution overnight at 4°C and then embedded in paraffin.

Antibodies and antisera

For immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry and Western blot analyses we employed rabbit polyclonal antiserum against GAD, which recognizes both isoforms GAD65 and GAD67 (DPC Biermann, Bad Nauheim, Germany); rabbit polyclonal antiserum against VGAT (SySy Synaptic Systems GmbH, Göttingen, Germany); rabbit polyclonal antiserum against GABAA-α1 (Alomone Labs Inc., Jerusalem, Israel), sheep polyclonal antiserum against GABAB-R1 and GABAB-R2 (gift from Graham Disney and Fiona Marshall, GlaxoWellcome R&D Inc., Stevenage, UK), mouse monoclonal antiserum against PCNA (Merck Biosciences, Schwalbach, Germany) and mouse monoclonal antiserum against β-Actin (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany).

Cell culture

TM3 cells are an established Leydig cell line. They derived from mouse Leydig cells [40,41] and were cultured in F12-DME medium (pH 7.2; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) supplemented with 5 × 104 IU/l penicilline, 5 × 104 μg/l streptomycine, 5% horse serum (all from Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) and 2.5% fetal calf serum FCS Gold (PAA GmbH, Cölbe, Germany). AtT20 cells, a mouse adenohypophysial corticotroph tumor cell line [42,43], were cultured in F12-DME medium (pH 7.2; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), 15% horse serum (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) and 2.5% fetal calf serum FCS Gold (PAA GmbH, Cölbe, Germany). Both cell lines were kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing air and carbon dioxide (95%/5% vol/vol). In order to study proliferation and cellular PCNA content, TM3 cells were cultured for 24 h in serum-reduced medium (1% fetal calf serum, 2.5% horse serum). This treatment yields a synchronization of the cell cycle [40,44]. TM3 cells were incubated subsequently in the same serum-reduced medium with 10-5 M GABA, 10-5 M GABAA agonist isoguvacine, 10-5 M GABAB agonist baclofen, as well as combinations with 10-5 M GABAA antagonist bicuculline and 10-5 M GABAB antagonist phaclofen (BIOTREND GmbH, Köln, Germany) for 5, 10, 15, 30 min and for 24 h.

Cell proliferation studies

TM3 cells (5 × 103 cells per well) were plated on 96-well plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) and incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of GABA, isoguvacine, baclofen, bicuculline and phaclofen. One experiment included 32 replicate wells per treatment. As previously described [45,46], cell proliferation was determined by using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). The specificity and sensitivity of this method was previously evaluated in our lab by comparison with a [3H]thymidine incorporation assay [45].

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

Isolation of RNA from rodent testes, as well as RT and PCR for GAD65/67, VGAT and GABA receptor subunits were performed as described previously [47]. Conditions of PCR amplification consisted of 30 or 35 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 60 s, followed by final extension for 5 min at 72°C). Oligonucleotide primers, as specified in Table 1, were synthesized according to published sequences. Verification of cDNAs was achieved by direct sequencing [47].

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification

| Target | GenBank accession no. | Length (bp) | Primer sequence |

| GAD67 | NM_008077 | 393 | 5'-CTTCTTCCGGATGGTCATCTC-3' |

| 5'-ACGAGCAACATGCTATGGTCT-3' | |||

| GAD65 | NM_008078 | 372 | 5'-GATATGGTTGGATTAGCAGC-3' |

| 5'-CATTTTCCCTCTCTCATCAC-3' | |||

| VGAT | NM_009508 | 300 | 5'-CCTGTACGAGGAGAACGAAG-3' |

| 5'-AGCAGACTGAACTTGGACAC-3' | |||

| GABAA α1 | NM_010250 | 231 | 5'-CTACAGCAACCAGCTATACCC-3' |

| 5'-GCTCTCTGTTTAAATACGTGG-3 | |||

| GABAA α2 | NM_008066 | 282 | 5'-AAGGCTCCGTCATGATACAG-3' |

| 5'-ACTAACCCCTAATACAGGC-3' | |||

| GABAA α3 | NM_008067 | 418 | 5'-GACTTGCTTGGTCATGTTGTTGGG-3' |

| 5'-CAGAGGCCCTGGAGATGAAGAAGA-3' | |||

| GABAA β1 | NM_008069 | 540 | 5'-ATGATGCATCTGCAGCCA-3' |

| 5'-TGGAGTTCACGTCAGTCA-3' | |||

| GABAA β2 | NM_008070 | 402 | 5'-GCATGTATGTCTGCAGGA-3' |

| 5'-CTGACACCTACTTCCTGA-3' | |||

| GABAA β3 | NM_008071 | 224 | 5'-AGCCAAGGCCAAGAATGATCG-3' |

| 5'-TGCTTCTGTCTCCCATGTACC-3' | |||

| GABAA γ1 | X55272 | 191 | 5'-TTTCTTACGTGACAGCAATGG-3' |

| 5'-CATGGGAATGAGAGTGGATCC-3' | |||

| GABAA γ2 | NM_008073 | 351 | 5'-GCAATGGATCTCTTTGTA-3' |

| 5'-GTCCATTTTGGCAATGCG-3' | |||

| GABAA γ3 | NM_008074 | 251 | 5'-TGTCGAAAGCCAACCATCAGG-3' |

| 5'-GACTTGCACTCCTCATAGCAG-3' | |||

| GABAB R1 | NM_019439 | 350 | 5'-ATGTGGTAACCATCCAGC-3' |

| 5'-AGAAGATCGGCTACTACG-3' | |||

| GABAB R2 | XM_194138 | 354 | 5'-CATCATCTTCTGTAGCAC-3' |

| 5'-TCTGTGAAGTTGCCCAAG-3' |

Immunohistochemistry

Testicular distribution of GAD, VGAT, PCNA and GABAA/B receptor subunits were examined in deparaffinized sections (5 μm) of Bouin's fixed testes of rats and mice using an Avidin-Biotin-Peroxidase (ABC) immunohistochemical method as described previously [48]. Specific antisera against GAD65/67 (dilution 1:500), VGAT (dilution 1:750), GABAA-α1 (dilution 1:750), GABAB-R1 (dilution 1:1.000–1:500), GABAB-R2 (dilution 1:1000–1:500) and PCNA (dilution 1:1000–1:500) were employed. A biotin coupled polyclonal goat anti-rabbit antiserum (diluted 1:500; Jackson Inc., West Grove, USA), a biotin coupled goat anti-sheep antiserum (diluted 1:200; Dianova, Hamburg, Deutschland) or a biotin coupled goat anti-mouse antiserum (diluted 1:500; Jackson Inc., West Grove, USA) served as secondary antiserum. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as a chromogen. Sections incubated with buffer alone, buffer containing mouse, sheep or rabbit non-immune serum, respectively, served as controls for all samples. The sections were examined with a Axiovert photomicroscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

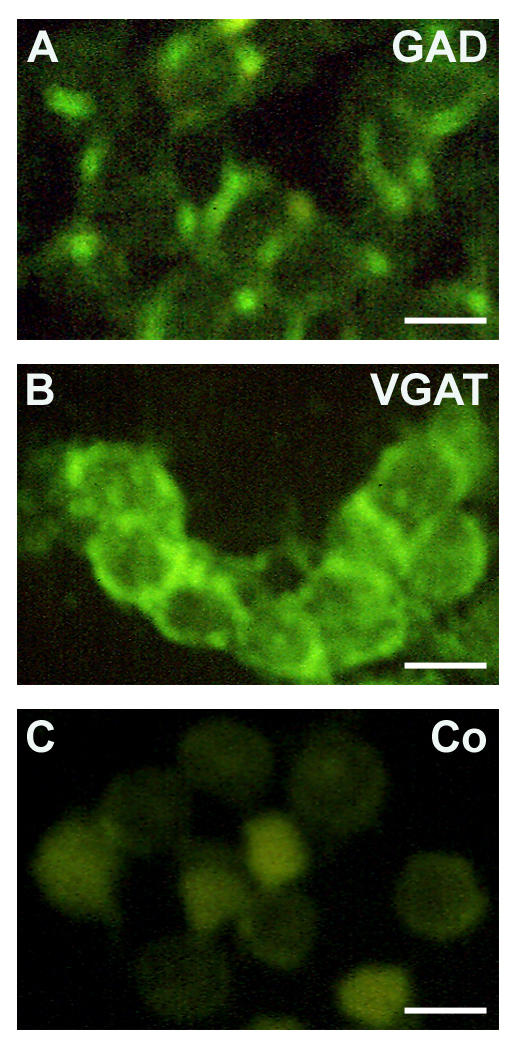

Immunocytochemistry

TM3 cells were cultivated on glass cover slips (2 × 104 cells per cover slip) for 1 day. They were then fixed and handled as previously described [49]. For immunolocalization an antiserum recognizing GAD65/67 and an antiserum recognizing VGAT was carried out overnight at 4°C (diluted 1:1000 in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffered saline containing 2% goat non-immune serum, pH 7.4). Immunoreactivity was visualized using a secondary polyclonal goat anti-rabbit antiserum (diluted 1:200; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). For control purposes either the specific antiserum was omitted or incubations with rabbit non-immune serum (dilution 1:10.000) were carried out instead. Sections were examined with a Axiovert microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), equipped with a FITC filter set.

Western blotting

Western blot analyses were performed with minor modifications as described previously [50]. In brief, TM3 cells and for control purposes tissue of mouse brain were lysated and homogenized in 62.5 mM Tris-HCL buffer (pH 6.8) containing 10% sucrose and 2% SDS by sonication, mercaptoethanol was added (10%), and the samples were heated (95°C for 5 min). Protein content was recorded [51] using a folin phenol quantitation method (DC protein assay, Bio-Rad GmbH, München, Germany). Then, 15 μg protein per lane was loaded on Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gels (12.5%), electrophoretically separated, and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Samples were probed with antiserum directed specifically against GAD65/67, PCNA and β-Actin (incubation overnight at 4°C, dilution 1:500). Immunoreactivity was detected using peroxidase labeled goat anti-rabbit antiserum (diluted: 1:5000; Jackson Inc., West Grove, USA) or peroxidase coupled goat anti-mouse antiserum (diluted: 1:5000; Jackson Inc., West Grove, USA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Buchler, Braunschweig, Germany). Integrated optical density of Western blot reaction with antiserum directed against PCNA and β-Actin in TM3 cells was measured using Scion Image 4.0.2 (Scion Corporation, Frederick, USA) as previously described in detail [52].

GAD activity measurements

Determination of GAD activity by measuring the production of radiolabeled carbon dioxide (CO2) from 14C-glutamate was performed as described previously [7,53]. In brief, TM3 cells, AtT20 cells and rat tissue samples were homogenized in 60 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.1), containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM 2-aminoethyl-isothiouronium bromide and 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), centrifuged, and the supernatants were used in the assay. The assay was performed in a total reaction volume of 60 μl, containing 20 μl of sample and 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM DTT, 0.05 mM pyridoxal phosphate, 9 mM L-glutamate, 3.3 μCi/ml 14C-glutamate (Biotrend, Köln, Germany, specific activity: 50–60 mCi/mmol) and 60 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The reaction mix was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then stopped by adding 100 μl of 10% trichloracetic acid per vial. The released CO2 was absorbed on benzethonium hydroxide-drenched filter disks, and bound radioactivity was determined using a Tri-Carb 2100 liquid scintillation counter (Packard, Meriden, USA). The values obtained were normalized to protein content measured by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad GmbH, München, Germany) described above. Rat tissue samples that were heated to 95°C for 5 min served as negative controls.

Statistical analyses

Statistic analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 3.02 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). The results obtained in cell proliferation and GAD assay experiments were compared using one-way-analysis of variance ANOVA followed by Newmann-Keuls test. The results received in Western blot experiments were compared using one-way-analysis of variance ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. Data shown are expressed as means+SEMs (standard error of the mean).

Results

A GABAergic system is present in postnatal rat testis: Active GAD, VGAT and GABAA-α1 in postnatal rat Leydig cells

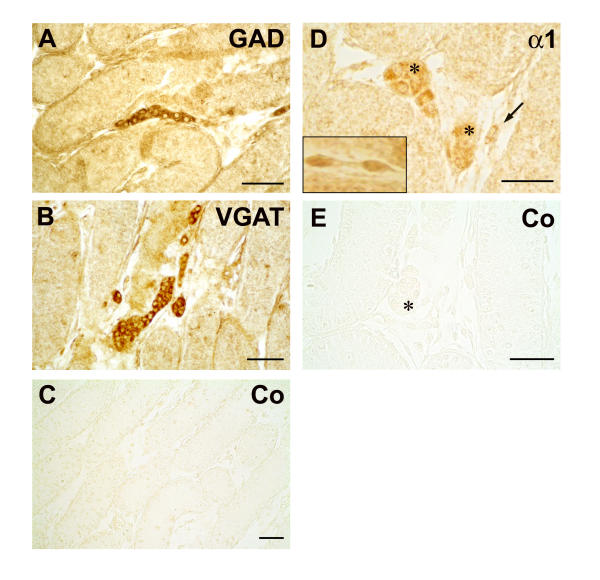

In postnatal rat testis immunohistochemical studies revealed that components of a local GABAergic system are present in interstitial cells (Figure 1). GAD65/67 and VGAT proteins were localized to the cytoplasm of interstitial cells. Because of their rounded morphology and clustered appearance these interstitial cells represent fetal Leydig cells. Protein of GABAA-α1 was immunolocalized not only to clustered fetal Leydig cells, but also to spindle-shaped interstitial cells. When antisera against GABAB-R1 and GABAB-R2 were employed, specific immunoreactive signals were absent. All control panels probed with buffer alone or non-immune rabbit serum were negative.

Figure 1.

Leydig cells in postnatal rat testis possess GAD, VGAT and GABAA-α1. Immunohistochemical localization of GAD, VGAT and GABAA-α1 in the testis of five days old rats. Fetal Leydig cells with typical rounded morphology are located in clusters between the seminiferous tubules and are immunopositive for GAD (A) and VGAT (B). No reaction was observed in sections incubated with buffer (data not shown) or non-immune rabbit serum (C) instead of the primary antibody. The GABAA receptor subunit α1 (D) is also immunolocalized to clustered fetal Leydig cells (*). However other interstitial cells with a spindle-shaped appearance also exhibit specific immunoreactivity against GABAA-α1 (D, →). The insert panel (D) also depicts magnified spindle-shaped interstitial cells of another section, which are immunopositive for GABAA-α1. No reaction was observed in sections incubated with buffer (data not shown) or non-immune rabbit serum (E) instead of the primary antibody. Bars: 50 μm.

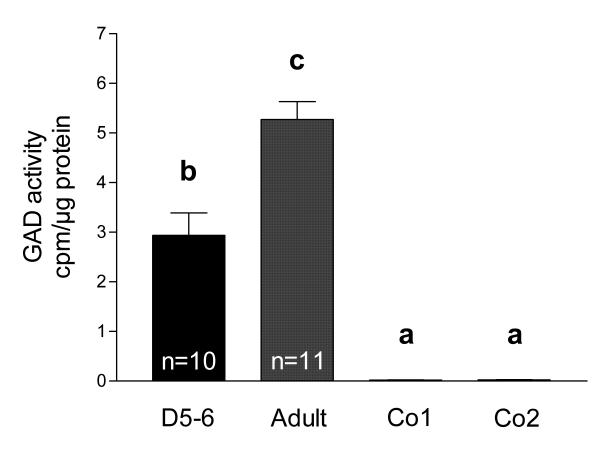

Evidence for enzymatically active GAD65/67 protein in postnatal rat testes was provided by measurements of 14C1-glutamic acid decarboxylation (Figure 2). Tissue of adult rat testes, which is known to possess GAD activity [7], served as positive control. GAD activity in postnatal (n = 10) rat testes was clearly detected (2.94 ± 0.45 cpm/μg protein), but was significantly lower than in adult (n = 11) rat testes (5.27 ± 0.36 cpm/μg protein; ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.001). Both values are significantly higher (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.001) from background and tissues, in which GAD was heat-inactivated (adult rat testes (n = 6) and adult rat cerebella (n = 6) heated to 95°C for 5 min).

Figure 2.

GAD is active in postnatal rat testis. GAD activity [cpm/μg protein] was measured in testicular tissue samples of 5–6 days old rats (D5-6, n = 10) and adult rats (Adult, n = 11). Tissue samples of adult rat testes (Co1, n = 6) and adult rat cerebella (Co2, n = 6) heated to 95°C for 5 min served as negative controls. GAD activity in adult testes is higher than GAD activity in postnatal testes. Columns with different superscripts are significantly (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.001) different from each other and represent means+SEMs.

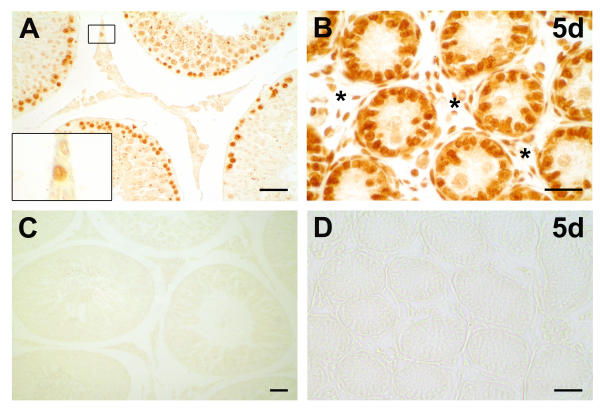

Proliferation marker PCNA is localized in interstitial cells of postnatal rodent testis

To identify proliferating cells in adult and postnatal rat testes we probed testicular tissue sections of rats (Figure 3) and mice (data not shown) with an antiserum against the proliferation marker PCNA. Specific immunoreactions were observed inside the seminiferous tubules on germ cells and in Sertoli cells, as well as in the cells of the interstitial compartment of all samples examined. In contrast, in adult rat testes we only occasionally found interstitial cells to be immunopositive for PCNA. In controls performed with buffer alone or buffer containing non-immune mouse serum, respectively, specific immunoreactivity was absent.

Figure 3.

PCNA in postnatal and adult rat testis. Immunohistochemical testicular localization of the proliferation marker PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) revealed that germ cells and Sertoli cells are immunopositive for PCNA, as seen in adult rat testis (A) and five days old (5d) rat testis (B). In interstitial spaces of adult testis (A) we sporadically found immunopositive cells (insert panel, A). In postnatal testis (B) abundant immunoreactive cells (*) were identified in the interstitium. No reaction was observed in sections incubated with buffer or non-immune serum (C, D) instead of the primary antibody. Bars: 25 μm.

The GABAergic system is also present in postnatal mouse testis: GAD67, VGAT and several GABAA receptor subunits in postnatal mouse testis

RT-PCR studies identified mRNAs of VGAT and GAD67, but not of GAD65 (data not shown). Furthermore, mRNAs of the GABAA receptor subunits α2, β1, β2, β3 and γ3 were readily detected (Table 2). The mRNAs of the GABAA receptor subunits α1, α3, γ1, γ2 and of the GABAB receptor subunits R1 and R2 were not found in postnatal mouse testis in several RT-PCR experiments. Immunohistochemical experiments (using GAD and VGAT antisera) yielded results similar to the ones obtained in rat (data not shown).

Table 2.

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in postnatal mouse testis (D5) and in TM3 cells revealed by RT-PCR

| GABAA receptor subunits | |||||||||

| α1 | α2 | α3 | β1 | β2 | β3 | γ1 | γ2 | γ3 | |

| D5 | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| TM3 | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - |

The RT-PCR results (+) in postnatal mouse testis (D5) and in TM3 cells were confirmed by sequencing; (-) indicates that the expected mRNA was not detected in several RT-PCR experiments.

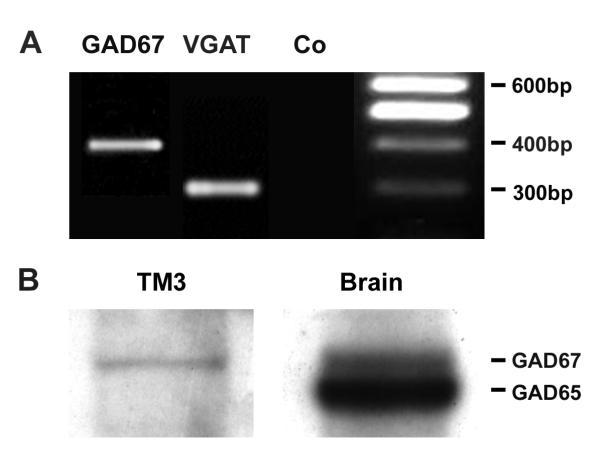

TM3 Leydig cells possess active GAD67, VGAT and GABAA receptor subunits α1, α2 β1, β3 and γ1

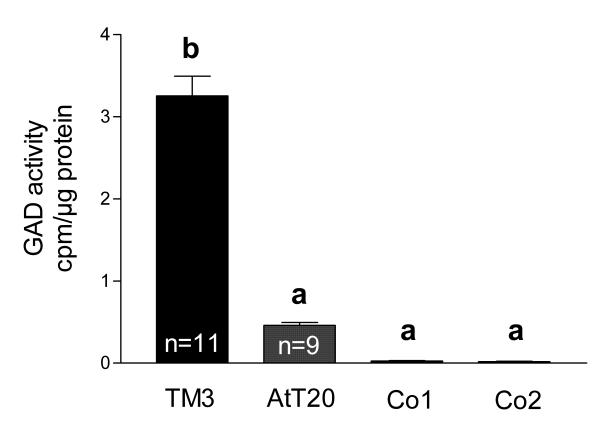

To examine whether mouse-derived TM3 cells may serve as model for proliferating Leydig cells, we first determined whether TM3 cells are able to produce GABA and possess GABA receptors. Specific immunocytochemical staining against GAD65/67 and VGAT protein was observed in TM3 cells (Figure 4). Specific immunoreactivity was absent in controls performed with buffer alone or buffer containing non-immune rabbit serum, respectively. RT-PCR and Western blot experiments confirmed these results and revealed GAD67, but not GAD65, in TM3 cells (Figure 5). GAD67 protein in TM3 cells was found to be enzymatically active (Figure 6) with an assayed GAD activity of 3.25 ± 0.24 cpm/μg protein (n = 11). TM3 cells (n = 6) and rat testicular tissue (n = 6), both heated to 95°C for 5 min, served as negative controls. GAD activity of TM3 cells was significantly (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.001) higher than GAD activity (0.46 ± 0.05 cpm/μg protein) of AtT20 cells (n = 9), another mouse cell line. GAD activities of AtT20 cells and of negative controls (inactivated by boiling) were not significantly different from each other (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Immmunocytochemical evidence for the presence of GAD and VGAT in TM3 cells. A cytoplasmatic staining pattern for GAD (glutamate decarboxylase) and VGAT (vesicular GABA transporter) was observed in TM3 cells (A, B). Controls included using non-immune serum (C) and omission of primary antiserum. Bars: 15 μm.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR and Western blot results: TM3 cells express GAD67 and VGAT. RT-PCR experiments (A) revealed that TM3 cells possess mRNA for GAD67, but lack GAD65 (data not shown), as well as VGAT. Expected product sizes were 399 bp for GAD67 and 302 bp for VGAT. Western blot analysis (B) revealed the presence of GAD67 in TM3 cells. Protein probes from mouse brain served as positive control and depict immunoreactivity for both GAD isoforms.

Figure 6.

GAD is active in TM3 cells. GAD activity [cpm/μg protein] was measured in TM3 cells (n = 11 batches of cells) and in AtT20 cells (n = 9 batches of cells), another endocrine mouse cell line used for control purposes. TM3 cells (Co1, n = 6 batches of cells) and testicular samples of adult rats (Co2, n = 6), both heated to 95°C for 5 min, served as additional negative controls. Testicular GAD activity in TM3 cells is higher than GAD activity in AtT20 cells or in controls. Columns with different superscripts are significantly (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.001) different from each other and represent means+SEMs.

Furthermore, mRNAs of the GABAA receptor subunits α1, α2, β1, β3 and γ1 were readily detected in TM3 cells (Table 2). In contrast the mRNAs of the GABAA receptor subunits α3, β2, γ2 and γ3, as well as the mRNAs of the GABAB receptor subunits R1 and R2 were not found in TM3 cells in several RT-PCR experiments.

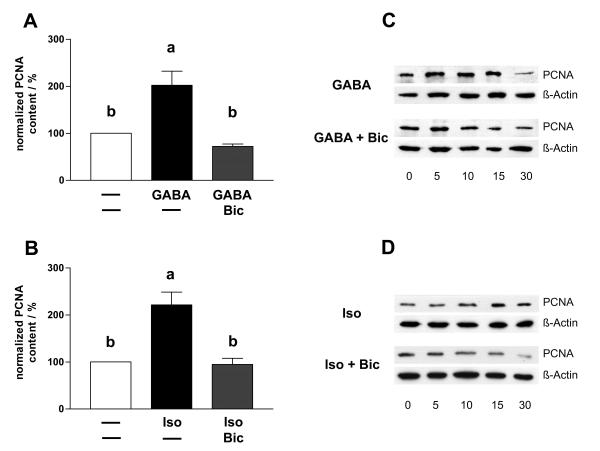

GABA and GABAA agonist isoguvacine increase cellular content of PCNA in TM3 cells

Levels of the proliferation marker PCNA was determined using Western blotting after stimulation with GABA or GABA receptor agonists/antagonists in TM3 cells (Figure 7). TM3 cells were incubated 0, 5, 10, 15, 30 min with GABA, GABA+bicuculline, isoguvacine, isoguvacine+bicuculline, baclofen and baclofen+phaclofen, respectively, and PCNA content was semiquantitatively determined by Western blotting. Signals were normalized and thus corrected for minor loading differences with the help of the results obtained for β-Actin (n = 5 experiments per treatment). Stimulation with GABA or GABAa agonist isoguvacine lasting for 15 min significantly (ANOVA/Dunnett's, p < 0.001) increased PCNA content in TM3 cells compared to untreated samples (0 min stimulation). This effect was blocked by co-incubation with GABAa antagonist bicuculline. Stimulation with GABAB agonists or antagonists (baclofen, and baclofen+phaclofen) did not alter PCNA content in TM3 cells (data not shown).

Figure 7.

PCNA content in TM3 cells is increased by GABA and GABAA agonist isoguvacine. Using Western blot analyses we examined PCNA content of TM3 cells after 0, 5, 10, 15, 30 min stimulation with GABA, GABA+bicuculline, isoguvacine and isoguvacine+bicuculline, respectively. The PCNA content of TM3 cells after 15 min stimulation with GABA (A) is significantly higher compared to untreated TM3 cells or compared to TM3 cells stimulated for 15 min with GABA+bicuculline. After 15 min stimulation with isoguvacine (B) the PCNA content of TM3 cells is also significantly higher compared to untreated TM3 cells or compared to TM3 cells stimulated for 15 min with isoguvacine+bicuculline. Data represent means+SEMs of n = 5 independent experiments and were normalized to β-Actin levels. Columns with different superscripts are significantly (p < 0.001, ANOVA/Dunnett's test) different from each other. Figure 7C and 7D depict representative Western blot experiments, respectively.

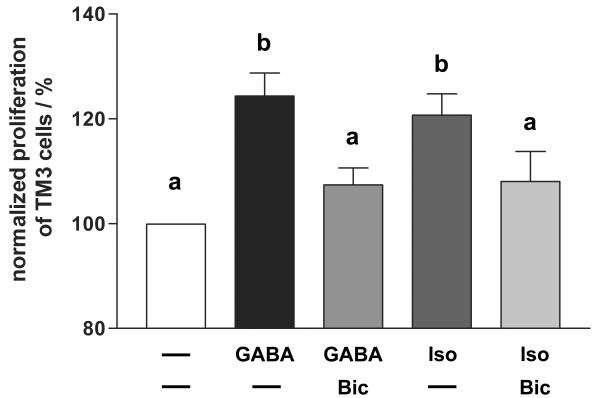

GABA induced TM3 cell proliferation is mediated by GABAA receptor

In order to investigate whether GABAA receptor activation is not only able to increase PCNA content in TM3 cells, but indeed can stimulate TM3 cell proliferation, we performed proliferation assays (Figure 8). TM3 cells were incubated for 24 h with GABA (n = 22), isoguvacine (n = 21), baclofen (n = 25), GABA+bicuculline (n = 19) and isoguvacine+bicuculline (n = 13). GABA significantly (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.05) increased TM3 cell proliferation up to 124.3 ± 4.4% compared to untreated controls (n = 36; 100%). Stimulation with isoguvacine also significantly (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.05) increased cell proliferation up to 120.7 ± 4.1%, but baclofen treatment did not result in significant alteration in cell proliferation. Further evidence for involvement of GABAA receptors was provided by blocking of the proliferative effects of GABA and isoguvacine by GABAA antagonist bicuculline (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

GABA and GABAA agonist isoguvacine stimulate TM3 cell proliferation. Summary graph of 13–36 independent experiments (means+SEMs). TM3 cells were incubated for 24 h with GABA (n = 22), GABA+bicuculline (n = 19), isoguvacine (n = 21) and isoguvacine+bicuculline (n = 13). Both GABA and isoguvacine stimulated TM3 cell proliferation, whereas addition of bicuculline blocked these effects. All results were normalized to proliferation of unstimulated TM3 cells (n = 36), serving as control panel. Columns with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (ANOVA/Newmann-Keuls, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study shows that crucial components of a GABAergic system are present in the endocrine compartment of postnatal rodent testis and that GABA stimulates proliferation of TM3 Leydig cells via GABAA receptors. These results suggest that GABA may regulate cell proliferation of fetal Leydig cells and/or mesenchymal precursors of the adult Leydig cell lineage in an auto-/paracrine manner. We therefore suggest that GABA may contribute to the morphogenesis of the testis.

Previously we and others demonstrated first details of a local GABAergic system in the endocrine compartment of adult rodent and human testis [7,54]. Adult Leydig cells possess enzymatically active GAD, VGAT and several GABAA and GABAB receptor subunits. Both isoforms GAD65 and GAD67 were present in rats and mice [7]. The functional significance of a testicular GABAergic system is not well known, but auto-/paracrine modulation of testosterone production in Leydig cells is a possibility suggested by studies describing stimulating effects of GABA on testosterone production in rats [8,9]. Since hormonal influences clearly govern steroid production of the adult testis, the modulatory effect of GABA on testosterone may however not be the main effect of GABA.

We rather speculated that GABA may exert trophic effects in the testis. This assumption was based on the trophic action of GABA via GABAA receptors in the developing brain. We focused in this study therefore on the postnatal testis, which bears proliferating cells including fetal Leydig cells and cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage.

It is widely accepted that two distinct Leydig cell populations are present during the first postnatal week in mouse and rat testis [33,34,36-39], namely steroidogenic fetal Leydig cells and mesenchymal precursors of adult Leydig cells. The first mentioned form conspicuous clusters in the interstitium [31,34,55]. Although fetal Leydig cells represent a differentiated cell population, there is evidence for a moderate increase in the number of these cells during the first two weeks of postnatal development [31,39]. In contrast, non-steroidogenic mesenchymal precursor cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage are located primarily in peritubular regions and proliferate strongly. They differentiate during the second postnatal week into progenitor cells and from the end of the third week on into newly formed, immature and then into fully functional mature adult Leydig cells [33,34,36-38].

Our immunohistochemical findings indeed evidenced dramatic proliferative events in the postnatal testis. Interstitial and peritubular cells in the testis of five days old rats expressed the proliferation marker PCNA, which was used in testicular tissues before [56-58]. Among these cells are likely connective tissue cells and endothelial cells [59-61], but also fetal Leydig cells and mesenchymal precursors of adult Leydig cells, as judged by their typical location and morphology. Since the latter are undifferentiated in nature [34,36-38], we could not use specific markers to distinguish them from other cell types.

Our study links Leydig cells proliferation and local testicular GABA synthesis. This is based first on the fact that we identified GABA synthesis and GABAA receptors in the postnatal testis of rodents, and second on the proliferative action of GABA and GABAA agonists in TM3 Leydig cells.

We identified only fetal Leydig cells, characterized by their rounded morphology and clustered appearance in the testicular interstitium, to possess GAD67 and VGAT. In contrast to adult testis, GAD65 was not detected. GAD67 was, however, found to be enzymatically active in rat testicular tissue of the same developmental stage. These two results together allow the conclusion that only fetal Leydig cells possess the pivotal molecules to synthesize and store GABA.

The present investigation provides insights into the possible targets of testicular GABA. As evidenced by RT-PCR studies, several GABAA receptor subunits are expressed in the postnatal testis. GABAB receptors were not found in postnatal testis, a result in contrast to our previous study in the adult rodent testis [7]. Immunolocalization of GABAA receptor subunits was hampered, due to availability of suitable antisera, but localization of GABAA-α1 revealed presence on rat fetal Leydig cells, but also on spindle-shaped interstitial cells. At least some of the last mentioned cells are very likely to represent mesenchymal precursor cells of the adult Leydig cell lineage. Thus according to the immunolocalization of GABAA-α1, both fetal Leydig cells and precursors of adult Leydig cells, are possible targets for GABA in the postnatal testis.

The number of fetal Leydig cells increases moderately in rodents during the first two weeks of postnatal development [31,39] and it is possible that GABA may mediate this effect. Another possibility is that GABA may modulate cell proliferation of mesenchymal precursor cells of adult Leydig cells or other GABAA receptor bearing testicular cell types. Based on our results in the present study, it is possible that GABA might even be a start signal leading to proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal precursors of adult Leydig cells. Interestingly, this signal is as yet unknown [34,37,38]. Thyroid hormone may be involved, but participation of LH and androgens in the initiation of adult Leydig cell development was ruled out [37,39,62-66].

Clearly, in-vivo evidence for such a crucial role of testicular GABA is as yet missing, but unequivocal evidence for a proliferative action of GABA via GABAA receptors was provided by cell culture experiments using TM3 Leydig cells, which possess GABAA receptor subunits. Involvement of GABAA receptors was suggested by the use of the pharmacologically well defined GABAA agonist isoguvacine and by the use of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline. Interestingly, this signaling pathway is in analogy to studies in the developing brain, where GABA also induces cell proliferation of neuronal progenitors and other neuronal cell types via activation of GABAA receptors [10-13].

In summary, a GABAergic system exists already in postnatal rodent testis and differs from the one in adult testis, since one of the two GAD isoforms as well as GABAB receptor subunits are missing. Nevertheless, it appears functional and our results suggest that GABA has similar roles in the developing brain and in the developing testis, namely to act as a trophic factor affecting the morphogenesis of crucial cells in these two organs.

Authors' contributions

CG carried out most of the experiments, participated in the study design, performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. RFGD carried out part of RT-PCR, Western blotting and immunocytochemistry. AT and AK provided technical assistance. AM conceived of the study, and participated in its design, coordination and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Marlies Rauchfuss and Andreas Mauermayer for their expert technical assistance and Lars Kunz and Martin Albrecht for helpful discussions. We thank Prof. Ricardo S. Calandra and Dr. Silvia Gonzalez-Calvar for providing some of the mouse samples. This study was supported by DFG-Graduiertenkolleg 333 "Biology of human diseases".

Contributor Information

Christof Geigerseder, Email: geigerseder@web.de.

Richard FG Doepner, Email: richard.doepner@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

Andrea Thalhammer, Email: andreathalhammer@t-online.de.

Annette Krieger, Email: annette.krieger@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

Artur Mayerhofer, Email: Mayerhofer@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

References

- Mayerhofer A, Hohne-Zell B, Gamel-Didelon K, Jung H, Redecker P, Grube D, Urbanski HF, Gasnier B, Fritschy JM, Gratzl M. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA): a para- and/or autocrine hormone in the pituitary. FASEB J. 2001;15:1089–1091. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0546fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamel-Didelon K, Corsi C, Pepeu G, Jung H, Gratzl M, Mayerhofer A. An autocrine role for pituitary GABA: activation of GABA-B receptors and regulation of growth hormone levels. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;76:170–177. doi: 10.1159/000064523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamel-Didelon K, Kunz L, Fohr KJ, Gratzl M, Mayerhofer A. Molecular and physiological evidence for functional gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-C receptors in growth hormone-secreting cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20192–20195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P, Berggren PO, Bokvist K, Ericson H, Mohler H, Ostenson CG, Smith PA. Glucose-inhibition of glucagon secretion involves activation of GABAA-receptor chloride channels. Nature. 1989;341:233–236. doi: 10.1038/341233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilon P, Bertrand G, Loubatieres-Mariani MM, Remacle C, Henquin JC. The influence of gamma-aminobutyric acid on hormone release by the mouse and rat endocrine pancreas. Endocrinology. 1991;129:2521–2529. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin LS, Kinard TA. Neurotransmitters and their receptors in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas: what messages do acetylcholine, glutamate, and GABA transmit? Endocrine. 1998;8:213–223. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:8:3:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigerseder C, Doepner R, Thalhammer A, Frungieri MB, Gamel-Didelon K, Calandra RS, Kohn FM, Mayerhofer A. Evidence for a GABAergic system in rodent and human testis: local GABA production and GABA receptors. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;77:314–323. doi: 10.1159/000070897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritta MN, Calandra RS. Occurrence of GABA in rat testis and its effect on androgen production. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1986;42:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritta MN, Campos MB, Calandra RS. Effect of GABA and benzodiazepines on testicular androgen production. Life Sci. 1987;40:791–798. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ari Y, Tseeb V, Raggozzino D, Khazipov R, Gaiarsa JL. gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA): a fast excitatory transmitter which may regulate the development of hippocampal neurones in early postnatal life. Prog Brain Res. 1994;102:261–273. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder JM, Liu J, Devaud L, Morrow AL. GABA as a trophic factor for developing monoamine neurons. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:247–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein AR, Owens DF. GABA may act as a self-limiting trophic factor at developing synapses. Sci STKE. 2001;95:E1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.95.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nrn919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Yaakov G, Golan H. Cell proliferation in response to GABA in postnatal hippocampal slice culture. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2003;21:153–157. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5748(03)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Rigo JM, Rocher V, Belachew S, Malgrange B, Rogister B, Leprince P, Moonen G. Neurotransmitters as early signals for central nervous system development. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305:187–202. doi: 10.1007/s004410000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszman ML, Borodinsky LN, Neale JH. GABA induces proliferation of immature cerebellar granule cells grown in vitro. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;115:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar TF, Wang F, Schwartz ML, Rakic P. Differential modulation of proliferation in the neocortical ventricular and subventricular zones. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5764–5774. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05764.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RR, Hoge GJ, Zigova T, Luskin MB. Neural progenitor cells of the neonatal rat anterior subventricular zone express functional GABA(A) receptors. J Neurobiol. 2002;50:305–322. doi: 10.1002/neu.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodinsky LN, O'Leary D, Neale JH, Vicini S, Coso OA, Fiszman ML. GABA-induced neurite outgrowth of cerebellar granule cells is mediated by GABA(A) receptor activation, calcium influx and CaMKII and erk1/2 pathways. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1411–1420. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MO, Li S, Park MS, Hornung JP. Early fetal expression of GABA(B1) and GABA(B2) receptor mRNAs on the development of the rat central nervous system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;143:47–55. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(03)00099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Krueger DD, Bordey A. GABA depolarizes neuronal progenitors of the postnatal subventricular zone via GABAA receptor activation. J Physiol. 2003;550:785–800. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fueshko SM, Key S, Wray S. GABA inhibits migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in embryonic olfactory explants. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2560–2569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02560.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar TN, Schaffner AE, Scott CA, O'Connell C, Barker JL. Differential response of cortical plate and ventricular zone cells to GABA as a migration stimulus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6378–6387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar TN, Schaffner AE, Scott CA, Greene CL, Barker JL. GABA receptor antagonists modulate postmitotic cell migration in slice cultures of embryonic rat cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:899–909. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.9.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J. The 'ABC' of GABA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:16–19. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Morrow AL, Devaud L, Grayson DR, Lauder JM. GABAA receptors mediate trophic effects of GABA on embryonic brainstem monoamine neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2420–2428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02420.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D, Liu QY, Maric I, Chaudry S, Chang YH, Smith SV, Sieghart W, Fritschy JM, Barker JL. GABA expression dominates neuronal lineage progression in the embryonic rat neocortex and facilitates neurite outgrowth via GABA(A) autoreceptor/Cl-channels. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2343–2360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02343.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat P, Paniagua R, Nistal M, Martin A. Mitosis in adult human Leydig cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1986;243:219–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00221871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis-Handagama SM. Mitosis in normal adult guinea pig Leydig cells. J Androl. 1991;12:240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, de Franca LR, Hess R, Cooke P. Characteristics of mitotic cells in developing and adult testes with observations on cell lineages. Tissue Cell. 1995;27:105–128. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuopio T, Tapanainen J, Pelliniemi LJ, Huhtaniemi I. Developmental stages of fetal-type Leydig cells in prepubertal rats. Development. 1989;107:213–220. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune H, Habert R, Saez JM. Origin, proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 1998;20:1–25. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ. Role of gonadotrophins in regulating numbers of Leydig and Sertoli cells during fetal and postnatal development in mice. Reproduction. 2001;122:227–234. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habert R, Lejeune H, Saez JM. Origin, differentiation and regulation of fetal and adult Leydig cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;179:47–74. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller-Fabre V, Levacher C, Pairault C, Racine C, Moreau E, Olaso R, Livera G, Migrenne S, Delbes G, Habert R. Development of the foetal and neonatal testis. Andrologia. 2003;35:79–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2003.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton L, Shan LX, Hardy MP. Differentiation of adult Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;53:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00022-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyaratne HB, Mendis-Handagama SM, Buchanan HD, Ian MJ. Studies on the onset of Leydig precursor cell differentiation in the prepubertal rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:165–171. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis-Handagama SM, Ariyaratne HB. Differentiation of the adult Leydig cell population in the postnatal testis. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:660–671. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyaratne HB, Mendis-Handagama SM. Changes in the testis interstitium of Sprague Dawley rats from birth to sexual maturity. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:680–690. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather JP. Establishment and characterization of two distinct mouse testicular epithelial cell lines. Biol Reprod. 1980;23:243–252. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod23.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Mason AJ, Schwall R, Szonyi E, Mather JP. Secretion of activin by interstitial cells in the testis. Science. 1989;243:396–398. doi: 10.1126/science.2492117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth DN, Nicholson WE, Mitchell WM, Island DP, Shapiro M, Byyny RL. ACTH and MSH production by a single cloned mouse pituitary tumor cell line. Endocrinology. 1973;92:385–393. doi: 10.1210/endo-92-2-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, Mains RE. High molecular weight forms of adrenocorticotropic hormone in the mouse pituitary and in a mouse pituitary tumor cell line. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3836–3844. doi: 10.1021/bi00688a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather JP, Zhuang LZ, Perez-Infante V, Phillips DM. Culture of testicular cells in hormone-supplemented serum-free medium. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;383:44–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb23161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommersberg B, Bulling A, Salzer U, Frohlich U, Garfield RE, Amsterdam A, Mayerhofer A. Gap junction communication and connexin 43 gene expression in a rat granulosa cell line: regulation by follicle-stimulating hormone. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1661–1668. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frungieri MB, Weidinger S, Meineke V, Kohn FM, Mayerhofer A. Proliferative action of mast-cell tryptase is mediated by PAR2, COX2, prostaglandins, and PPARgamma : Possible relevance to human fibrotic disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15072–15077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232422999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz S, Fohr KJ, Boddien S, Berg U, Brucker C, Mayerhofer A. Functional and molecular characterization of a muscarinic receptor type and evidence for expression of choline-acetyltransferase and vesicular acetylcholine transporter in human granulosa-luteal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1744–1750. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.5.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer A, Frungieri MB, Fritz S, Bulling A, Jessberger B, Vogt HJ. Evidence for catecholaminergic, neuronlike cells in the adult human testis: changes associated with testicular pathologies. J Androl. 1999;20:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer A, Danilchik M, Pau KY, Lara HE, Russell LD, Ojeda SR. Testis of prepubertal rhesus monkeys receives a dual catecholaminergic input provided by the extrinsic innervation and an intragonadal source of catecholamines. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:509–518. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohne-Zell B, Gratzl M. Adrenal chromaffin cells contain functionally different SNAP-25 monomers and SNAP-25/syntaxin heterodimers. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00931-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GL. Review of the Folin phenol protein quantitation method of Lowry, Rosebrough, Farr and Randall. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:201–220. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse J, Bulling A, Brucker C, Berg U, Amsterdam A, Mayerhofer A, Gratzl M. Synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kilodaltons in oocytes and steroid-producing cells of rat and human ovary: molecular analysis and regulation by gonadotropins. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:643–650. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger NR, Heller JS. Localization of glutamic acid decarboxylase within laminae of the rat olfactory tubercle. J Neurochem. 1979;33:299–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb11732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frungieri MB, Gonzalez-Calvar SI, Chandrashekar V, Rao JN, Bartke A, Calandra RS. Testicular gamma-aminobutyric acid and circulating androgens in Syrian and Djungarian hamsters during sexual development. Int J Androl. 1996;19:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1996.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtaniemi I, Pelliniemi LJ. Fetal Leydig cells: cellular origin, morphology, life span, and special functional features. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1992;201:125–140. doi: 10.3181/00379727-201-43493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman V, Rao VS, Sairam MR, Rao AJ. Effect of deprival of LH on Leydig cell proliferation: involvement of PCNA, cyclin D3 and IGF-1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;162:113–120. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi P, Franco R, Fulgione D, Staibano S. PCNA in the testis of the frog, Rana esculenta: a molecular marker of the mitotic testicular epithelium proliferation. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2000;119:11–16. doi: 10.1006/gcen.2000.7500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang JH, Sankai T, Yoshida T, Yoshikawa Y. Immunolocalization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) testes during postnatal development. J Med Primatol. 2001;30:107–111. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2001.300206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer A, Bartke A. Developing testicular microvasculature in the golden hamster, Mesocricetus auratus: a model for angiogenesis under physiological conditions. Acta Anat (Basel) 1990;139:78–85. doi: 10.1159/000146982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck L, I, Lissbrant E, Persson A, Damber JE, Bergh A. Endothelial cell proliferation in male reproductive organs of adult rat is high and regulated by testicular factors. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1107–1111. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.008284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggstrom RS, Wikstrom P, Jonsson A, Collin O, Bergh A. Hormonal Regulation and Functional Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A in the Rat Testis. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1231–1237. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Baker P, Sohnius U, Haavisto AM, Charlton HM, Huhtaniemi I. Fetal development of Leydig cell activity in the mouse is independent of pituitary gonadotroph function. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1141–1146. doi: 10.1210/en.139.3.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Johnston H, Abel M, Charlton H, O'Shaughnessy P. Differentiation of adult-type Leydig cells occurs in gonadotrophin-deficient mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Johnston H, Willerton L, Baker PJ. Failure of normal adult Leydig cell development in androgen-receptor-deficient mice. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3491–3496. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teerds KJ, de Rooij DG, de Jong FH, van Haaster LH. Development of the adult-type Leydig cell population in the rat is affected by neonatal thyroid hormone levels. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:344–350. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis-Handagama SM, Ariyaratne HB, Teunissen van Manen KR, Haupt RL. Differentiation of adult Leydig cells in the neonatal rat testis is arrested by hypothyroidism. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:351–357. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]