In this issue of Cytometry part A, Montiel-Eulefi et al. describe a neurogenic cell population residing in the vascular wall of rat aortas. Although the authors did not characterize them in situ, these aorta-derived cells were shown to express well-known pericytic markers such as CD90, α-smooth muscle actin, and the platelet derived growth factor receptors α and β (1,2) after a short period in culture. The authors also report the native expression of the neural stem cell marker nestin (3), which in combination with the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan NG2 marks both pericytes and neurogenic progenitors (1,3). They validated the neurogenic potential of cultured aorta-derived pericytes by showing the acquisition of mature neural marker expression and functional neural-like stimulus-response. In this study, the pluripotency associated marker stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA-1) was detected on aorta-derived cultured pericytes only after induction of neuronal differentiation, in contrast to SSEA-1 expression by human microvascular pericytes, which has been reported to be constitutive (4).

A variety of multilineage stem/progenitor cells have been described in the recent literature, most of them being identified retrospectively following primary culture. These include multipotent adult progenitor cells (5), mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) (6) and adipose-derived stem cells (ASC; Ref. 7). Most of these multipotent cell populations have been localized in vivo to a niche in the microvasculature wall, including MSC (8) and ASC (4,7), although MSC have been also isolated from larger vessels, both arteries (9) and veins (10). At the clonal level, the multilineage potential of MSC (and other comparable stem cell populations) has been demonstrated in vitro for mesenchymal lineages (adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, and either skeletal or smooth muscle potential; reviewed in Ref. 11). Further, trans-differentiation across germ layers has been reported by various groups, including differentiation toward neuronal lineages (reviewed in Ref. 11). During embryogenesis, MSC originate in two distinct waves, the first from the neural crest. A second wave appears to derive from the mesoderm (12). The relationship between MSC and pericytes in the adult is not immediately clear. In a variety of tissues, pericytes have been proposed to be the immediate progenitors of MSC (8). Brain microvascular pericytes have been previously shown to differentiate into multiple neuronal lineages (3), consistent with the observation that pericytes residing in the face and forebrain originate, like neurons, from the neural crest (13). In this work, the authors successfully differentiated aorta-derived pericytes toward the neurogenic lineage, suggesting that pericytes originating outside the neural crest can also be induced to differentiate down the neuronal lineage pathway. The constitutive coexpression of nestin and NG2 in tissue pericytes is consistent with neuronal-lineage priming, similar to that observed in mesenchymal lineages (6), and potentially explaining the cross-germ layer plasticity reported in the literature (11).

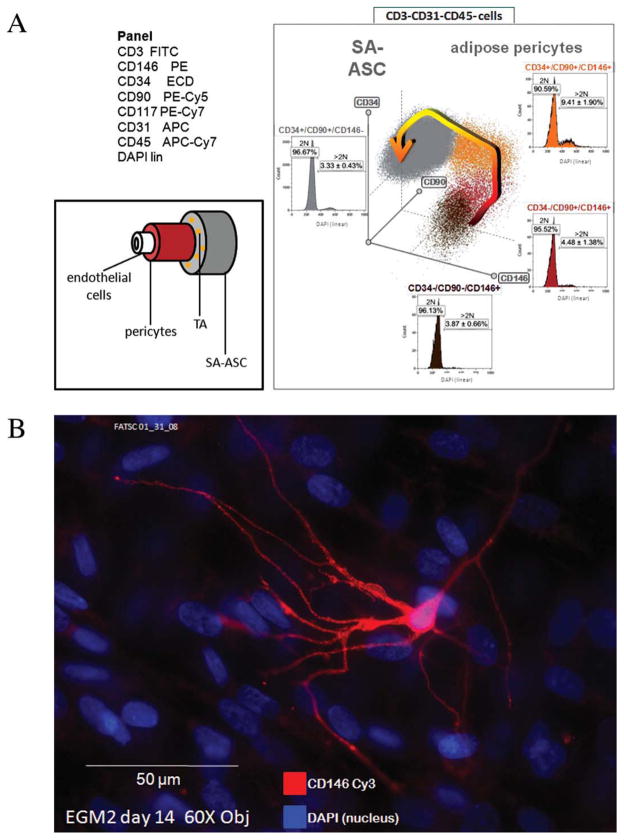

Our own data, relating adipose pericytes, which associate with the microvasculature (7), to the mesenchymal-like supra-adventitial adipose stromal cells (SA-ASC), which surround small vessels in an annular fashion, support the interpretation that pericytes are the progenitors of MSC in the adult. Figure 1A shows a hypothetical differentiation scheme based on multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of the stromal vascular fraction of disaggregated adipose tissue. According to this scheme, CD146+, CD90±, CD34− pericytes differentiate from the inside out, giving rise to MSC-like CD146−, CD90+, CD34+ SA-ASC through a rare CD146+, CD90+, CD34+ transit amplifying cell of high proliferative capacity. The SA-ASC undergo spontaneous adipogenesis after reaching confluence in culture and presumably give rise to mature adi-pocytes in vivo. In keeping with the findings of Montiel-Eulefi et al. human adipose stromal vascular cells also occasionally give rise to CD146+ cells with neuronal morphology after two weeks in culture in the presence of EGM2 (Fig. 1B). CD 146 is not just a pericyte marker. In the neurobiology literature it is known as gicerin, a ligand for nerve outgrowth factor with an important role in neurite extension and synaptogenesis (14).

Figure 1.

(A) Differentiation scheme for pericytes, transit amplifying cells and supra-adventitial stem cells in adipose tissue. Flow cytometry was performed on 10 freshly isolated human adipose stromal vascular preparations according to previously published methods. The antibody specificities and fluorochromes used are shown in the top left panel. A three-dimensional histogram (radar plot) was generated with Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter) and was gated on the CD3-/CD31-/CD45-population. The arrow indicates the hypothesized progression from CD34-/CD90±/CD146+ pericytes to CD34+/CD90+/CD146-SA-ASC through a CD146+/CD34+ intermediate (bottom left panel). The proportion of proliferating cells in each subset (mean ± SEM) was determined by DAPI nuclear staining. The asterisk indicates P < 0.05 in the proportion of cells with >2N DNA (compared to all other populations, Student’s two-tailed t-test). (B) Growth of a cell with neuronal morphology in a primary culture of human adipose stromal vascular cells. Cells were cultured in the EGM2 medium (Lonza) in a Labtek chamber slide coated with gelatin (0.1%, Sigma). The photomicrograph was taken with a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-U microscope (×60 objective) equipped with a Spot camera.

Taken together, these data may help answer the conundrum posed by adult tissue stem cells: Does each tissue have its own oligopotent stem cell which arises during embryogenesis after lineage specification, or is there a universal pluripotent adult tissue stem cell which has escaped lineage restriction (15)? If the findings of Montiel-Eulefi et al., which even large vessels harbor pericytes capable of cross germ-layer differentiation, prove to be generalizable, then pericytes may represent something approaching the universal adult tissue stem cell, and the adventitia of large and small vessels may be their niche.

Literature Cited

- 1.Tarnok A, Ulrich H, Bocsi J. Phenotypes of stem cells from diverse origin. Cytometry A. 2010;77A:6–10. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dore-Duffy P, Cleary K. Morphology and properties of pericytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;686:49–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-938-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dore-Duffy P, Katychev A, Wang X, Van Buren E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:613–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin G, Garcia M, Ning H, Banie L, Guo YL, Lue TF, Lin CS. Defining stem and progenitor cells within adipose tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:1053–1063. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyes M, Verfaillie CM. Characterization of multipotent adult progenitor cells, a sub-population of mesenchymal stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;938:231–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03593.x. discussion 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delorme B, Ringe J, Pontikoglou C, Gaillard J, Langonne A, Sensebe L, Noel D, Jorgensen C, Haupl T, Charbord P. Specific lineage-priming of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells provides the molecular framework for their plasticity. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/stem.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerlin L, Donnenberg VS, Pfeifer ME, Meyer EM, Peault B, Rubin JP, Donnenberg AD. Stromal vascular progenitors in adult human adipose tissue. Cytometry A. 2010;77A:22–30. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, Norotte C, Teng PN, Traas J, Schugar R, Deasy BM, Badylak S, Buhring HJ, Giacobino JP, Lazzari L, Huard J, Peault B. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Mesenchymal stem cells and the artery wall. Circ Res. 2004;95:671–676. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000143421.27684.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covas DT, Piccinato CE, Orellana MD, Siufi JL, Silva WA, Jr, Proto-Siqueira R, Rizzatti EG, Neder L, Silva AR, Rocha V, Zago MA. Mesenchymal stem cells can be obtained from the human saphena vein. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnenberg VS, Zimmerlin L, Rubin JP, Donnenberg AD. Regenerative therapy after cancer: what are the risks? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:567–575. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morikawa S, Mabuchi Y, Niibe K, Suzuki S, Nagoshi N, Sunabori T, Shimmura S, Nagai Y, Nakagawa T, Okano H, Matsuzaki Y. Development of mesenchymal stem cells partially originate from the neural crest. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, Couly GF. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development. 2001;128:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukamoto Y, Taira E, Miki N, Sasaki F. The role of gicerin, a novel cell adhesion molecule, in development, regeneration and neoplasia. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:563–571. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melton DA, Cowen C. Stemness: Definitions, criteria, and standards. In: Lanza RP, editor. Essentials of Stem Cell Biology. Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2006. pp. xxv–xxxi. [Google Scholar]