Abstract

Background

The German Federal Joint Committee (the highest decision-making body of physicians and health insurance funds in Germany) has established minimum caseload requirements with the goal of improving patient care. Such requirements have been in place for five types of surgical procedure since 2004 and were introduced for total knee endoprosthesis surgery in 2006 and for the care of low-birth-weight neonates (weighing less than 1250 g) in 2010.

Method

We analyzed data from German nationwide DRG statistics (DRG = diagnosis-related groups) for the years 2005–2011. The procedures that were performed were identified on the basis of their operation and procedure codes, and the low-birth-weight neonates on the basis of their birth weight and age. The treating facilities were distinguished from one another by their institutional identifying numbers, which were contained in the DRG database.

Results

In 2011, there were 172 838 hospitalizations to which minimum caseload requirements were applicable. 4.5% of these took place in institutions that did not meet the minimum requirement for the procedure in question. The percentage of institutions that did not meet the minimum caseload requirement for complex pancreatic surgery fell significantly from 64.6% in 2006 to 48.7% in 2011, and the percentage of pancreatic surgery cases treated in such institutions fell over the same period from 19.0% to 11.4%. A significant reduction in the number of institutions treating low-birth-weight neonates was already evident before minimum caseload requirements were introduced. For all other types of procedure subject to minimum caseload requirements, there has been no significant change either in the percentage of institutions meeting the requirements or in the percentage of cases treated in such institutions.

Conclusion

After taking account of the potential bias due to the identification of institutions by their institutional identifying numbers, we found no discernible effect of minimum caseload requirements on care structures over the seven-year period of observation, with the possible exception of a mild effect on pancreatic procedures.

Many observational studies have shown that the outcomes of some surgical procedures are correlated with caseload (1– 10). For this reason, the German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) has established minimum caseload requirements for certain types of elective procedure for which this has been demonstrated. Minimum caseload requirements for hepatic and renal transplantation, complex esophageal and pancreatic surgery, and stem cell transplantation went into effect in 2004. Total knee replacement surgery has been subject to minimum caseload requirements since 2006, and the care of neonates weighing less than 1250 g at birth (whether born prematurely or at term) since 2010 (11, 12). Thus, such requirements have been established for seven different types of procedure.

The minimum caseload requirements for total knee replacement surgery were suspended in 2011 after legal battles (13). The minimum caseload requirement for the care of low-birth-weight neonates was to be increased in 2011 from 14 to 30 cases per year, but this planned increase was also suspended, and the old requirement of 14 cases per year is still in effect (14). The minimum caseload requirements are formally binding on all hospitals that are permitted to charge the German statutory health-insurance carriers for their services. The relevant regulation states: “If an institution is not expected to meet the minimum caseload requirement for an elective procedure, then the procedure may not be performed in that institution, starting in the year that the requirement goes into effect” (§5 Mm-R). The regulation also provides for certain general exceptions to the rule. When a particular type of procedure is established in an institution and the staff performing the procedure in that institution changes, the new team is allowed up to two years to meet the caseload requirement; three years are allowed when the procedure is new to the institution. Moreover, comprehensive coverage of the population must be provided (15).

Research on this topic to date has centered on changes in the care situation from 2004 to 2006. Over this period, there was no major change in the number of hospitals providing care, and 1% to 31% of patients (depending on the procedure) were operated on in hospitals that did not meet the minimum caseload requirement for the procedure in question (16).

Further changes in the care situation from 2006 onward have not been assessed until now. We therefore studied developments with respect to the affected procedures over the years 2005–2011. This study is based on hospital billing data; the billing units were identified on the basis of the institutional identifying numbers that the hospitals used for billing.

Materials and methods

In this study, we performed a monitored remote data analysis on the complete federal DRG statistics (DRG = diagnosis-related groups) for individual cases that was obtained from the research data centers of the German federal and state statistical offices (17). The DRG statistics covered all hospitalizations billed according to the DRG system. Each of the ca. 17 million inpatient treatments carried out in Germany per year can be evaluated in this way. The main exceptions are psychiatric and psychosomatic cases, which are not covered by DRG statistics but are, in any case, irrelevant to the issue of minimum caseload requirements (for more on this, see eMethods). The documentation of every case included a main diagnosis, additional diagnoses, the procedures performed (coded according to the Operations and Procedures Classification—Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel, OPS), the reason for discharge, and the anonymized institutional identifying number of the hospital (18– 21) (further details in eMethods).

Cases of treatment that were subject to minimum caseload requirements were identified in these data on a case-by-case basis by means of the OPS codes for each type of procedure that were established by the G-BA for the procedure and year in question. For hepatic transplantation and pancreatic surgery, the G-BA definition also includes the OPS codes for post-mortem organ removal (5–503.0 hepatectomy, post mortem; 5–525.4 pancreatectomy, post mortem [for transplantation]). These codes were included in the analysis to determine whether the minimum caseload requirements, as set by the G-BA, were actually reached if the institutions also performed transplantations. Treating institutions that performed only post mortem hepatectomy and pancreatectomy were not considered in the analysis, however, because a reduction in the number of organ donations cannot be a goal of regulations that establish minimum caseload requirements. In the OPS, the category of liver transplantation contains both post-mortem and living-donor transplantation, and these were both tallied to determine the caseload, as is stipulated in the minimum caseload regulation. Institutions that performed only living-organ donations without any coded transplantations were counted as independent institutions.

Neonates weighing less than 1250 g at birth were identified in the database by their birth weight and an age of 28 days or less (22).

Treating (or, more precisely, billing) institutions were distinguished from one another by their institutional identifying numbers (Institutionskennzeichen, IK numbers). This was the basis for the tallying of case numbers for each institution. The German Federal Statistical Office considers a billing institution for the purpose of DRG statistics to be a “hospital providing inpatient services that are reimbursable in the DRG system (hospitals that are spread over multiple sites but have a single institutional identifying number are counted only once)” (23). The number of such billing institutions differs slightly from the number of hospitals contained in the register of basic data for German hospitals (Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser, [24]), which is usually cited as the number of hospitals in Germany.

In 2011, the register of basic data for German hospitals counted a total of 2045 hospitals, of which 1736 were general hospitals and the remaining 309 were either hospitals with exclusively psychiatric and psychotherapeutic (and also neurological) beds or else day clinics and night clinics, which are not subject to minimum caseload requirements and generally do not bill in the DRG system.

The DRG statistics for 2011 are derived from a total of 1601 billing institutions with different IK numbers. This number is a bit lower than the number of hospitals in the basic data register, although it should be remembered that not all general hospitals bill according to the DRG system. For reasons of data protection, we cannot determine what institutions account for the difference, as it is not permitted for individual hospitals to be identifiable.

Both collections of statistics revealed a drop in the number of hospitals over the course of the study. The basic hospital data showed that, in 2005 and 2011, there were 1846 and 1736 general hospitals, respectively; the DRG statistics for the same years contained 1,725 and 1,601 IK numbers, respectively). The current study is based on 'billing institutions' in the sense used in the DRG statistics. It should be borne in mind that one hospital can have multiple IK numbers, while, conversely, a single IK number can refer to treatment at multiple, geographically separated sites.

We used generalized linear regression models weighted by the annual total number of billing institutions and cases to search for linear trends in the number of treating institutions in each year, the percentage of such institutions that did not meet the minimum caseload requirements, and the number of cases treated in them. For the determination of trends, only the statistics from 2006 onward were considered, because different caseload requirements and definitions were in effect in 2005.

In eMethods, we describe additional subgroups of the types of procedures that were subject to minimum caseload requirements (eTable).

eTable. Treating institutions broken down by their annual case numbers in relation to minimum caseload requirements (MCR).

| Type of procedure | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic transplantation (including living-donor partial hepatectomy) | Mimimum caseload requirement | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Number of treating institutions | 519 | 35 | 31 | 37 | 28 | 33 | 31 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 29% | 35% | 32% | 39% | 42% | 42% | ||

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 17% | 19% | 11% | 21% | 15% | 13% | ||

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 11% | 13% | 5% | 4% | 6% | 16% | ||

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 43% | 32% | 51% | 36% | 36% | 29% | ||

| Renal transplantation | Mimimum caseload requirement | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Number of treating institutions | 50 | 51 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 42 | 49 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 52% | 41% | 47% | 47% | 49% | 57% | 49% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 26% | 33% | 34% | 28% | 26% | 31% | 24% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | Xxx*5 | 0% | Xxx*5 | 9% | 6% | Xxx*5 | Xxx*5 | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | Xxx*5 | 25% | Xxx*5 | 17% | 19% | Xxx*5 | Xxx*5 | |

| Complex esophageal surgery | Mimimum caseload requirement | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of treating institutions | 445 | 399 | 426 | 426 | 411 | 427 | 411 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 21% | 8% | 9% | 9% | 10% | 10% | 10% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 21% | 22% | 19% | 19% | 21% | 20% | 21% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 16% | 24% | 21% | 22% | 20% | 22% | 24% | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 42% | 47% | 52% | 49% | 48% | 48% | 44% | |

| Complex pancreatic surgery | Mimimum caseload requirement | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of treating institutions | 760 | 697 | 673 | 667 | 699 | 680 | 678 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 34% | 16% | 18% | 19% | 18% | 20% | 22% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 21% | 19% | 27% | 26% | 28% | 27% | 30% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 15% | 21% | 18% | 19% | 17% | 19% | 17% | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 30% | 44% | 38% | 36% | 33% | 34% | 31% | |

| Stem cell transplantation | Mimimum caseload requirement | 12±2 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Number of treating institutions | 97 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 91 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 53% | 36% | 37% | 36% | 37% | 38% | 42% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 16% | 28% | 28% | 27% | 21% | 27% | 23% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 14% | 14% | 14% | 17% | 18% | 15% | 15% | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 16% | 22% | 21% | 20% | 25% | 21% | 20% | |

| Total knee replacement | Mimimum caseload requirement | none*6 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Number of treating institutions | 1,041 | 999 | 985 | 996 | 1,004 | 1,015 | 1,024 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 41% | 45% | 50% | 52% | 54% | 53% | 51% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 26% | 35% | 35% | 34% | 33% | 34% | 33% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 14% | 8% | 6% | 6% | 7% | 7% | 9% | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 18% | 12% | 9% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 7% | |

| Treatment of low-birth-weight neonates | Mimimum caseload requirement | none*7 | none*7 | none*7 | none*7 | none*7 | 14 | 14 |

| Number of treating institutions | 465 | 433 | 403 | 370 | 369 | 371 | 347 | |

| *1 caseload > 2 x MCR | 17% | 18% | 18% | 19% | 19% | 25% | 25% | |

| *2 MCR ≤ caseload ≤ 2 x MCR | 14% | 15% | 18% | 18% | 21% | 16% | 19% | |

| *3 MCR/2 ≤ caseload < mcr | 12% | 11% | 11% | 10% | 9% | 8% | 8% | |

| *4 caseload < mcr/2 | 57% | 56% | 53% | 52% | 51% | 51% | 48% |

*1Institutions with more than twice the required caseload

*2Institutions meeting the caseload requirement with at most twice the required caseload

*3Institutions that failed to meet the caseload requirement, but performed at least half of the required number of cases

*4Institutions that performed fewer than half of the required number of cases

*5The Federal Statistical Office does not release case numbers lower than 3 for publication, for reasons of legally mandated data protection\

*6Minimum caseload requirement introduced in 2006; a minimum of 50 cases was used to analyze the data from 2005

*7Minimum caseload requirement introduced in 2010; a minimum of 14 cases was used to analyze the data from 2005–2009

Results

In 2011, 172 838 cases, or 1.0% of all inpatient cases in the DRG statistics, were subject to minimum caseload requirements. Depending on the type of procedure group, 16.1% to 68.4% of the performing institutions did not meet the minimum caseload requirements for the procedure in question; 4.5% of the 172 838 cases were performed in such institutions.

The number of cases per year rose for all types of procedure studied except the care of low-birth-weight neonates (Table 1). There was a continuous, significant decline in the number of institutions treating low-birth-weight neonates (from 465 to 347); this was the only such decline noted for any of the types of procedure subject to minimum caseload requirements. Accordingly, the percentage of institutions that met the minimum requirement of 14 low-birth-weight infants treated per year rose significantly from 31.6% in 2005 to 43.8% in 2011 (p<0.0001).

Table 1. Types of procedure, minimum caseload requirements, and developments 2005–2011.

| Type of procedure | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic transplantation (incl. living-donor partial donation)*1 | Minimum caseload | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Number of cases | 5799*2 | 1020 | 1131 | 1091 | 1079 | 1231 | 1172 | |

| Treating institutions | 519 *2 | 35 | 31 | 37 | 28 | 33 | 31*3 | |

| Mean caseload | 11.2 | 29.1 | 36.5 | 29.5 | 38.5 | 37.3 | 37.8 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 22% | 46% | 55% | 43% | 61% | 58% | 55% | |

| Renal transplantation | Minimum caseload | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Number of cases | 2639 | 2747 | 2909 | 2740 | 2769 | 2892 | 2877 | |

| Treating institutions | 50 | 51 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 42 | 49 | |

| Mean caseload | 52.78 | 53.86 | 61.89 | 58.30 | 58.91 | 68.86 | 58.71 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 78% | 75% | 81% | 74% | 74% | 88% | 73% | |

| Complex esophageal surgery | Minimum caseload | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of cases | 3186 | 3248 | 3358 | 3524 | 3588 | 3618 | 3673 | |

| Treating institutions | 445 | 399 | 426 | 426 | 411 | 427 | 411 | |

| Mean caseload | 7.2 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.9 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 42% | 30% | 27% | 28% | 32% | 30% | 32% | |

| Complex pancreatic surgery*1 | Minimum caseload | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of cases | 8904 | 8327 | 9149 | 9299 | 9714 | 10005 | 10577 | |

| Treating institutions | 760 | 697 | 673 | 667 | 699 | 680 | 678 | |

| Mean caseload | 11.7 | 11.9 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 14.7 | 15.6 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 55% | 35% | 44% | 45% | 46% | 47% | 51% | |

| Stem cell transplantation | Minimum caseload | 12±2 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Number of cases | 5537 | 6178 | 5733 | 5954 | 6064 | 6367 | 6725 | |

| Treating institutions | 97 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 91 | |

| Mean caseload | 57.1 | 64.4 | 59.1 | 62.0 | 62.5 | 66.3 | 73.9 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 69% | 65% | 65% | 64% | 58% | 65% | 65% | |

| Total knee replacement | Minimum caseload | none*4 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50*5 |

| Number of cases | 118243 | 124682 | 134767 | 141876 | 145116 | 143495 | 141928 | |

| Treating institutions | 1041 | 999 | 985 | 996 | 1004 | 1015 | 1024 | |

| Mean caseload | 113.6 | 124.8 | 136.8 | 142.5 | 144.5 | 141.4 | 138.6 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 68% | 79% | 85% | 86% | 87% | 87% | 84% | |

| Care of low-birth-weight neonates | Minimum caseload | none*6 | none*6 | none*6 | none*6 | none*6 | 14 | 14 |

| Number of cases | 6035 | 5801 | 5981 | 5646 | 5732 | 6378 | 5886 | |

| Treating institutions | 465 | 433 | 403 | 370 | 369 | 371 | 347 | |

| Mean caseload | 13.0 | 13.4 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 17.0 | |

| Percentage of institutions meeting caseload requirement | 32% | 33% | 36% | 38% | 40% | 41% | 44% |

*1Not including institutions that only performed post-mortem organ removal. Post-mortem organ removals performed in the institutions included here were counted in the tallies.

*2There was a change in included codes (OPS definition) for this procedures between 2005 and 2006 that affected the case numbers.

*3Of the 31 treating institutions, 24 carried out transplants; the remainder only performed living-donor partial resections or resections of liver transplants as independent procedures. These procedures are counted in the minimum caseload requirement.

*4Minimum caseload requirement introduced in 2006; 50 cases used as basis for comparative calculations for the year 2005.

*5Minimum caseload requirement suspended in 2011.

*6Minimum caseload requirement introduced in 2010; 14 cases per year used as basis for comparative calculations for the years 2005–2009

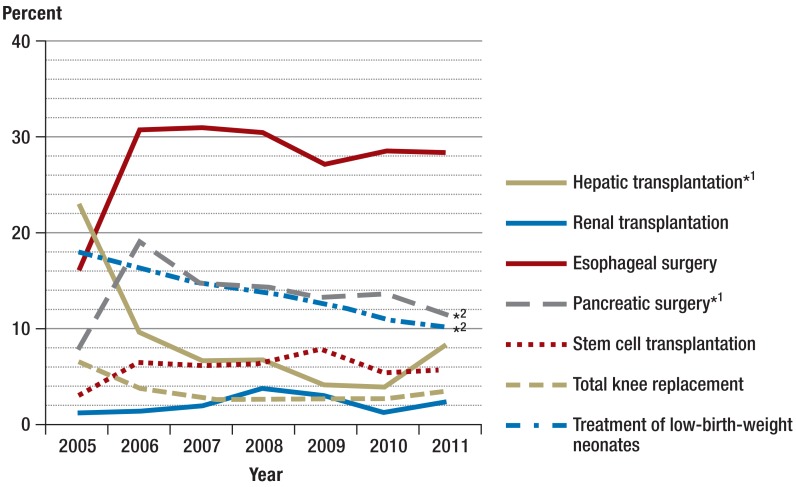

For all other types of procedure, the number of treating institutions varied only slightly over time, without significant trends (Table 1). No concentration of care in a smaller number of institutions was seen. The observed increases in the mean case numbers per institution and per year were accounted for in large part by increases in the total number of cases treated, with a relatively stable number of treating institutions. Only in the case of pancreatic surgery the increase in total delivered care resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirement (p = 0.012) (Figure 1). The number of pancreatic operations performed in such institutions decreased significantly, as did the number of low-birth-weight treatments in institutions that did not meet the minimum caseload requirement for such treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The percentage of treating institutions that did not meet minimum caseload requirements, over time;

*1Institutions that only performed post-mortem organ removal have been excluded;

*2two-tailed p-value for linear trend (2006–2011), <0.05

Figure 2.

The percentage of cases treated in institutions that did not meet minimum caseload requirements, over time;

*1Institutions that only performed post-mortem organ removal have been excluded;

*2two-tailed p-value for linear trend (2006–2011), <0.05

The percentage of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements rose significantly from 2006 to 2011 both for pancreatic surgery (35.4% to 51.3%) and for the treatment of low-birth-weight neonates (33% to 44%). There was no significant rise for any of the other five types of procedure. The figures for 2006 and 2011, respectively, were: for hepatic transplantation, 45.7% and 54.8%; for renal transplantation, 74.5% and 73.5%; for esophageal surgery, 29.6% and 31.6%; for stem cell transplantation, 64.6% and 64.8%; for knee replacement surgery, 79.5% and 83.9% (Table 1).

There were no systematic differences in patient sex ratios between institutions that did and did not meet the minimum caseload requirements. There were, however, systematic differences with respect to age: in institutions that did not meet the minimum caseload requirements for hepatic transplantation, esophageal surgery, and stem cell transplantation, the average age was slightly higher (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of patients and treating institutions, broken down by fulfillment or non-fulfillment of minimum caseload requirements.

| Minimum caseload achieved | Minimum caseload not achieved | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Hepatic transplantation (including partial liver donation from a living donor)* | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 116 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 403 | 19 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 14 | 14 |

| Cases | 4462 | 922 | 1058 | 1019 | 1036 | 1186 | 1078 | 1337 | 98 | 73 | 72 | 43 | 45 | 94 |

| Mean number of cases | 38 | 58 | 62 | 64 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Mean age | 57 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 63 | 51 | 52 | 54 | 55 | 53 | 55 |

| Percent female | 44% | 36% | 36% | 39% | 35% | 36% | 33% | 47% | 49% | 33% | 35% | 45% | 48% | 28% |

| Renal transplantation | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 39 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 35 | 37 | 36 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 13 |

| Cases | 2611 | 2717 | 2861 | 2645 | 2693 | 2862 | 2817 | 28 | 30 | 48 | 95 | 76 | 30 | 60 |

| Mean number of cases | 67 | 72 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Mean age | 49 | 50 | 50 | 49 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 44 | 42 | 55 | 49 | 53 | 50 | 54 |

| Percent female | 39% | 38% | 38% | 37% | 36% | 37% | 37% | 18% | 47% | 35% | 35% | 28% | 40% | 27% |

| Complex esophageal surgery | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 186 | 118 | 116 | 121 | 131 | 127 | 130 | 259 | 281 | 310 | 305 | 280 | 300 | 281 |

| Cases | 2677 | 2251 | 2323 | 2455 | 2615 | 2589 | 2634 | 509 | 997 | 1035 | 1069 | 973 | 1029 | 1039 |

| Mean number of cases | 14 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Mean age | 62 | 62 | 62 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 65 |

| Percent female | 20% | 24% | 23% | 23% | 22% | 22% | 22% | 25% | 27% | 27% | 28% | 25% | 27% | 22% |

| Complex pancreatic surgery* | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 420 | 247 | 297 | 302 | 322 | 320 | 348 | 340 | 450 | 376 | 365 | 347 | 360 | 330 |

| Cases | 8208 | 6748 | 7816 | 7979 | 8444 | 8658 | 9369 | 696 | 1579 | 1333 | 1320 | 1270 | 1347 | 1208 |

| Mean number of cases | 20 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean age | 61 | 61 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 63 | 63 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Percent female | 42% | 42% | 43% | 44% | 43% | 45% | 44% | 40% | 44% | 43% | 43% | 46% | 43% | 43% |

| Stem cell transplantation | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 67 | 62 | 63 | 61 | 56 | 62 | 59 | 30 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 41 | 34 | 32 |

| Cases | 5380 | 5796 | 5405 | 5587 | 5609 | 6036 | 6359 | 157 | 382 | 328 | 367 | 455 | 331 | 366 |

| Mean number of cases | 80 | 93 | 86 | 92 | 100 | 97 | 108 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Mean age | 47 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 50 | 53 | 55 | 50 | 52 | 52 | 53 | 56 |

| Percent female | 38% | 38% | 38% | 38% | 37% | 38% | 38% | 29% | 38% | 39% | 36% | 40% | 38% | 34% |

| Total knee replacement | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 703 | 794 | 837 | 861 | 874 | 879 | 859 | 338 | 205 | 148 | 135 | 130 | 136 | 165 |

| Cases | 110535 | 120321 | 131576 | 138774 | 141739 | 140018 | 137502 | 7708 | 4361 | 3191 | 3102 | 3377 | 3477 | 4426 |

| Mean number of cases | 157 | 152 | 157 | 161 | 162 | 159 | 160 | 23 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 27 |

| Mean age | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 69 | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Percent female | 69% | 69% | 68% | 67% | 67% | 66% | 65% | 70% | 67% | 68% | 68% | 67% | 65% | 67% |

| Treatment of low-birth-weight neonates | ||||||||||||||

| Treating institutions | 147 | 145 | 145 | 140 | 147 | 151 | 152 | 318 | 288 | 258 | 230 | 222 | 220 | 195 |

| Cases | 4958 | 4864 | 5113 | 4878 | 5014 | 5692 | 5301 | 1077 | 937 | 868 | 768 | 718 | 686 | 585 |

| Mean number of cases | 34 | 34 | 35 | 35 | 34 | 37 | 35 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean age | 882 | 884 | 883 | 878 | 884 | 891 | 885 | 897 | 921 | 901 | 920 | 925 | 936 | 930 |

| Percent female | 49% | 49% | 49% | 49% | 49% | 48% | 49% | 50% | 49% | 49% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 49% |

*Institutions performing only post-mortem organ removal are not included

Discussion

The major strength of this study is the completeness of the database. The analyses presented here are based on complete billing data for each of the procedures in question, and, therefore, the parent population of all relevant inpatient cases was evaluated, rather than only a sample. The evaluation was thus hospital-independent and unaffected by the hospitals' own determinations or self reporting as to whether they met the minimum caseload requirements (as found, for example, in the hospitals' legally mandated quality-assurance reports).

On the other hand, the use of this extensive set of data also results in a major limitation of the study. In the DRG statistics of the German Federal Statistical Office, the distinction of one institution from another is made on the basis of IK numbers, i.e., the institutions considered in this study are single units with respect to billing. This definition does not correspond exactly to that of the approved German hospitals that can be found in other statistical databases.

A billing institution, as indicated in the DRG statistics, may correspond to only a part of a hospital. This can lead to underestimation of the number of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements. The opposite, however, may also be the case: multiple hospital sites can share a billing (IK) number, and this can lead to overestimation of the number of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements.

The overall number of billing institutions in the DRG statistics turns out to be slightly lower than the number of hospitals in the basic hospital data. Moreover, the number of institutions has declined over time in both statistics, perhaps because of mergers or a preferential loss of smaller institutions. Either mechanism would tend to result in an overestimation of the number of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements.

As “hospitals” are defined differently in each database, studies based on different databases can yield divergent results not only regarding the overall number of hospitals, but also regarding the percentage of hospitals that met minimum caseload requirements for any particular type of procedure (see, for example, the article by von de Cruppé et al. in this issue [25]).

When interpreting the findings of this study and similar studies, one must bear in mind that the definitions of individual procedures covered by minimum caseload requirements may have changed over the period of observation in such a way as to affect the number of procedures subject to the requirement (e.g., hepatic transplantation, from 2005 to 2006); that some of the minimum caseload thresholds were increased by the G-BA between 2005 and 2006; and that hospitals performing pancreatic and esophageal surgery exclusively on children are exempt from such requirements. All of these things were considered in the present study.

With the use of these methods, this study of the seven types of procedure that were subject to minimum caseload requirements from 2005 to 2011 revealed that the percentage of patients treated in institutions that did not meet such requirements dropped significantly in response to the requirements for only one of the seven types of procedure, namely, complex pancreatic surgery. A comparable, steady drop over the years 2005 to 2011 was observed for the care of low-birth-weight neonates but cannot be considered an effect of the minimum caseload requirement, which, in this case, was not introduced until 2010.

As for the number of institutions performing each of the procedures in question, slightly more institutions performed total knee replacement surgery in 2011 than in 2006 (a rise from 999 to 1024 institutions), but, in 2011, 16.1% of them failed to meet the minimum caseload requirement. On the other hand, the number of institutions caring for low-birth-weight neonates fell over the same period from 433 to 347, even though a minimum caseload requirement was only introduced in 2010. No statistically significant increases or decreases in the number of performing institutions were seen for any of the other five types of procedure.

Previously published findings on the implementation of minimum caseload requirements in the years 2004–2006 are consistent with those reported here. Geraedts et al. concluded at that time that their observation period had been too short to permit any robust conclusion about the efficacy of minimum caseload requirements (16). The present findings clearly show that minimum caseload requirements have had no discernible effect on care structures over a seven-year period, except for a possible, mild effect on pancreatic surgery, as revealed by an analysis of the treating and billing institutions. The observed changes in preterm neonatal care cannot be due to the minimum caseload requirements, as they mostly took place before the requirements went into effect in 2010. For none of the other types of procedure was there any decline in the number of institutions performing it, although this was intended when the minimum caseload requirements were introduced and might have been expected to occur. One can only speculate about why the minimum caseload requirements appear to have had so little effect.

A possible weakness of this study is that the evaluation was based on billing institutions (IK numbers). As recent years have seen more hospital mergers than hospital split-ups, one might have expected to see an artefactual decrease in the number of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements. It is also conceivable that the institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements were actually exempt from them under the stated exceptions to the minimum caseloads regulation. This would then have to have been true for the entire period of observation (because of the lack of observed change after the minimum caseload requirements were introduced). This, in turn, would indirectly imply that there was no need for the minimum caseload requirements in this case.

It is, however, also conceivable that the monitoring and implementation mechanisms for minimum caseload requirements are currently inadequate because too little attention is paid to this matter in the annual budget negotiations of hospitals and health insurance carriers, and on the state governmental level.

If minimum caseload requirements are wanted, they should also be implemented. The current state of regulation seems not to have achieved this aim. The causes of failure to meet the minimum caseload requirements should be examined in each of the affected institutions, or in a sampling of them, so that appropriate conclusions can be drawn about monitoring mechanisms, the legal formulation of minimum caseload requirements, and, possibly, a more accurate definition of the procedures that are to be covered by them.

Supplementary Material

Detailed description of materials and methods

In this study, we analyzed the DRG statistics of the research data centers of the German federal and state offices of statistics using monitored remote data processing (17). The DRG statistics contain individual case data on all inpatient cases billed according to the DRG system. These data are reported by the hospitals once a year to the Institute for the Hospital Reimbursement System (Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus). A selected list of features is reported to the Federal Statistical Office. Data in this database from the year 2005 onward have been made available by the federal and state offices of statistics for scientific evaluation (17). Such evaluations are carried out by means of SAS programs created by the scientific users themselves that can access the data stored at the Federal Statistical Office.

Each of the approximately 17 million cases of treatments billed under the DRG system each year is accessible to evaluation via this database. The main types of cases not contained in the database are those of specialized psychiatric and psychosomatic units that do not bill under the DRG system. Such cases are irrelevant to the topic of the present study, as the existing minimum caseload requirements do not apply to them.

Further types of cases not included in the database are, for example, those of German military hospitals (insofar as they are not billed under the DRG system) and prison hospitals. These exceptions are likewise irrelevant to the topic of the present study, as the minimum caseload requirements to not apply to these cases either.

For all cases covered, the DRG statistics contain information on the main and additional diagnoses, the procedures performed (coded according to the German Operations and Procedures classification—Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel, OPS), the reason for discharge, and the billing institution, identified by its institutional identifying number (see Methods in the main text) (18– 21). This information suffices to enable the determination whether each billing institution met its minimum caseload requirements. Thus, the present study was performed by applying a uniform algorithm to a single database that covered all inpatient treatments in all German hospitals (i.e., the statistical parent population of inpatient cases). There was no need to amalgamate data from multiple databases, so issues of compatibility of different databases did not arise. All analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.3 statistics software.

Cases to which the minimum caseload requirements applied, according to the pertinent legal regulation (§ 137 SGB V), were identified by the OPS codes that the German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) determined to be applicable to the procedure in question for the year in question; these are published in Appendix 1 of the regulation. Because the OPS undergoes continuous revision, with frequent changes of content, there have been small changes over the period 2005–2011 in the OPS codes that needed to be considered for all types of procedure subject to minimum caseload requirements, with the sole exception of renal transplantation. The only change of this type that had a major quantitative effect was seen in the area of hepatic transplantation: the G-BA decided to exclude OPS code 5–502 (anatomical [typical] hepatic resection) from 2006 onward, with the result that, in 2006, 4779 fewer hepatic cases were subject to minimum caseload requirements than in the preceding year (an 82.4% drop from 2005 to 2006) (11).

Neonates weighing less than 1250 g at birth, whether born prematurely or at term, were identified in the database from their birth weight and from an age of 28 days or less, corresponding to the WHO definition of a “neonate” (22). Quantitative trends in the treatment of low-birth-weight neonates from the year 2005 onward were analyzed in relation to the minimum caseload requirement of 14 cases per year, even though this requirement did not go into effect until 2010. Similarly, quantitative trends in total knee replacement surgery were analyzed from 2005 onward, even though the corresponding minimum caseload requirement did not go into effect until 2006 (11).

The minimum caseload requirements for complex esophageal surgery and for stem cell transplantation do not apply to institutions that exclusively treat children (15). The G-BA does not state the precise age limit of “childhood” for the purpose of this regulation; in the present study, we excluded institutions from consideration if all the patients they treated with these two types of procedure were under 20 years old.

A treating institution, for the purpose of the present analysis, was held to be equivalent to a single institutional identifying number (IK number); in other words, all cases with the same IK number were considered to have been treated in the same institution. This method of data analysis may have caused bias of either of two different types, or both:

Hospitals that are geographically distributed over multiple sites, but have only a single IK number, were only counted once (as in the official DRG statistics). This would tend to cause an overestimation of the number of cases per institution, and therefore an underestimation of the number of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements.

On the other hand, single-site hospitals that bill via multiple IK numbers were counted as multiple institutions. This would tend to cause an underestimation of the number of cases per institution, and therefore an overestimation of the number of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements (26).

Both of these constellations are rather rare, as shown by a comparison of a hospital count based on the IK numbers in the DRG statistics of the Federal Statistical Office with the the number of hospitals provided in the “basic hospital data” that are also maintained by this office (23, 24). The former of the two constellations is by far the more common in the real world. This implies that the present study probably overestimates the percentage of institutions that actually met the minimum caseload requirements—in other words, any bias, if present, is likely to be in the direction opposite to the central findings of the study. The validity of these findings is thus unaffected.

Table 1 contains a year-by-year listing of the percentages of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements. The supplementary eTable shows how many institutions met the requirements only halfway and how many performed more than twice the required number of cases for each of the types of procedure specified.

Results: further details

The minimum caseload requirements set by the G-BA for hepatic transplantation and complex pancreatic surgery also included post-mortem organ removal in the tallies for each of these types of procedure. The number of institutions whose procedures in the category of hepatic transplantation were confined to post-mortem hepatectomy varied from 27 to 63, depending on the year; the comparable figure for post-mortem pancreatectomy was 2 to 3 institutions, depending on the year. The annual number of post-mortem organ removal procedures in each of these two categories was always either one or two per institution. The analysis in the present study took no account of institutions exclusively performing post-mortem organ removal, because minimum caseload requirements are clearly not intended to apply to “donor clinics” of this type. Moreover, post-mortem organ removal procedures are billed differently from other types of procedure and may not have been fully coded in the available DRG database.

In the institutions studied that performed both hepatic and pancreatic transplantation procedures on organ recipients and explantations on brain-dead organ donors, the post-mortem organ removals accounted for a mean of 2.11% of all hepatic transplant procedures and 0.17% of all complex pancreatic operations.

The minimum caseload requirement for hepatic transplantation includes living-donor partial hepatectomy for transplantation (OPS code 5–503.*) in the tally of procedures; thus, institutions performing procedures with this OPS code were included in the analysis of the present study. In 2011, 31 institutions performed hepatic transplantations and/or living-donor partial hepatectomy: 24 performed hepatic transplantation (OPS key 5–504.*), while the remaining 7 performed only living-donor partial hepatectomy for transplantation or liver-transplant resection as an independent procedure (OPS codes 5–503.1 through 5–503.y).

The 24 institutions performing hepatic transplantation that were identified from the DRG data correspond in number to the transplant centers listed in the 2011 annual report of the German Foundation for Organ Transplantation (Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation, DSO) (27) and to those listed in the quality report of the AQUA Institute for 2011 (28).

49 institutions billing for renal transplantation were identified from the DRG data; the AQUA institute reported 43 hospitals performing renal transplantation in 2011, the DSO 41. This discrepancy cannot be accounted for by hospitals that exclusively performed donor nephrectomies, because such procedures are not included in the tally of cases for the minimum caseload requirement (here the rule for renal transplantation differs from that for hepatic transplantation). The discrepancy cannot be definitively explained without de-anonymization of the IK numbers, which is not permissible. Conceivably, some cases of renal transplantation performed in the context of a close cooperation between different institutions may have been billed under multiple IK numbers.

For a deeper analysis of the caseload problem, we also determined the number of institutions meeting each caseload requirement not even halfway, or fulfilling it with more than twice the number of cases required. The percentage of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirement even halfway was lower in 2011 than in 2005 for every type of procedure studied, but the change was significant only for pancreatic surgery (p = 0.012) and low-birth-weight neonatal care (p = 0.0057). On the other hand, the number of institutions meeting their requirements with more than twice the required number of cases rose significantly for hepatic transplantation (p = 0.011), esophageal surgery (p = 0.015), pancreatic surgery (p = 0.0072), and low-birth-weight neonatal care (p = 0.021). The highest percentages of institutions of this type in the year 2011 were found for total knee replacement (50.8%) and renal transplantation (49.0%) (eTable).

Key Messages.

Minimum caseload requirements for hepatic and renal transplantation, complex pancreatic surgery (such as pancreatectomy), complex esophageal surgery (such as esophagectomy), and stem cell transplantation went into effect in 2004. Total knee replacement surgery has been subject to minimum caseload requirements since 2006, and the care of neonates weighing less than 1250 g at birth since 2010. In 2011, 172 838 of the 17 708 910 inpatient treatments in the DRG statistics were subject to minimum caseload requirements.

This study, based on the billing institutions that are identifiable from DRG statistics, showed no reduction in the percentage of institutions that failed to meet minimum caseload requirements over a six-year period, with the exception of a small, significant reduction for pancreatic surgery. The observed reduction in the percentage of institutions that did not meet minimum outcome requirements for the care of low-birth-weight neonates occurred mainly before these requirements were introduced.

The percentage of cases treated in institutions that did not meet minimum caseload requirements was relatively low in 2011. It was 8% for liver transplantation (out of 1172 patients total), 2% for renal transplantation (of 2877), 28% for esophageal surgery (of 3673), 11% for pancreatic surgery (of 10 577), 5% for stem cell transplantation (of 6725), 3% for total knee replacement (of 141 928), and 10% for the care of low-birth-weight neonates (of 5886).

These findings show that minimum caseload requirements in Germany—as far as can be determined from a statistical analysis of DRG statistics—have not had any major influence on the care situation. This may be because the institutions that do not meet the requirements are actually exempt from them, but it also seems likely that the requirements are inadequately implemented.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The academic department of structural advancement and quality management in health care in which the authors work is funded by Helios Kliniken GmbH.

References

- 1.van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Scholten RJ, et al. Hospital volume and mortality after pancreatic resection: a systematic review and an evaluation of intervention in the Netherlands. Ann Surg. 2005;242:781–788. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000188462.00249.36. discussion 8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Wouters MW, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:485–494. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wouters MW, Gooiker GA, van Sandick JW, Tollenaar RA. The volume-outcome relation in the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 2012;118:1754–1763. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Thrumurthy S, Low DE. Volume-outcome relationship in surgery for esophageal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis 2000-2011. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1055–1063. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Matsuda S, et al. Relationship between hospital volume and operative mortality for liver resection: Data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination database. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:1073–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soohoo NF, Zingmond DS, Lieberman JR, Ko CY. Primary total knee arthroplasty in California 1991 to 2001: does hospital volume affect outcomes? J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1909–1916. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehby GL, Ullrich F, Xie Y. Very low birth weight hospital volume and mortality: an instrumental variables approach. Med Care. 2012;50:714–721. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e32cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller G, Gunster C, Misselwitz B, Feller A, Schmidt S. Jährliche Fallzahl pro Klinik und Überlebensrate sehr untergewichtiger Frühgeborener (VLBW) in Deutschland – Eine bundesweite Analyse mit Routinedaten [Annual patient volume and survival of very low birth weight infants (VLBWs) in Germany-a nationwide analysis based on administrative data] Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2007;211:123–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-960747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemeinsamer Budesausschuss. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlag; 2006. Anpassung der Anlage 1 der Mindestmengenvereinbarung nach § 137 Abs. 1 Satz 3 Nr. 3 SGB V. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlag; 2009. Bekanntmachung eines Beschlusses des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses zur Versorgung von Früh- und Neugeborenen. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlag; 2011. Bekanntmachung eines Beschlusses des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über eine befristete Außervollzugsetzung einer Regelung der Mindestmengenvereinbarung: Mindestmenge für Kniegelenk-Totalendoprothesen. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlag; 2012. Bekanntmachung eines Beschlusses des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über eine befristete Außervollzugsetzung einer Änderung der Mindestmengenregelungen: Mindestmenge für Früh- und Neugeborene Perinatalzentren Level 1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlag; 2013. Mindestmengenregelungen. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geraedts M, de Cruppe W, Blum K, Ohmann C. Implementation and effects of Germany's minimum volume regulations: results of the accompanying research. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:890–896. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forschungsdatenzentren der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. Datenangebot | Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) www.forschungsdatenzentrum.de/bestand/drg/index.asp. (last accessd 19. March.2014)

- 18.Statistisches Bundesamt. Qualitätsbereicht. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2011. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansky T, Nimptsch U. Notwendigkeit eines ungehinderten Zugangs zu sozial- und krankheitsbezogenen Versichertendaten für die Bundesärztekammer und andere ärztliche Körperschaften sowie wissenschaftliche Fachgesellschaften zur Optimierung der ärztlichen Versorgung. Expertise im Rahmen der Förderinitiative zur Versorgungsforschung der Bundesärztekammer. Technische Universität Berlin; 2010 www.bundesaerztekammer.de/downloads/Datenzugang-2.pdf (last accessed on 12 April 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus. Datenlieferung gemäß § 21 KHEntgG. Dokumente zur Datenlieferung. www.g-drg.de/cms/Datenlieferung_gem._21_KHEntgG/Dokumente_zur_Datenlieferung. (last accessed on 12 April 2014)

- 21.Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus. Vereinbarung über die Übermittlung von DRG-Daten nach § 21 Abs. 4 und Abs. 5 KHEntgG. www.g-drg.de/cms/Datenlieferung_gem._21_KHEntgG/Dokumente_zur_Datenlieferung/21-Vereinbarung. (last accessed 12 April 2014)

- 22.World Health Organization. Infant, Newborn. www.who.int/topics/infant_newborn. (last accessed on 12 April 2014)

- 23.Statistisches Bundesamt. Fachserie 12, Reihe 6.4. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2012. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistisches Bundesamt. Fachserie 12, Reihe 6.1.1. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2012. Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Cruppé W, Malik M, Geraedts M. Achieving minimum caseload requirements: an analysis of hospital quality control reports from 2004–2010. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014. 111:549–555. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nimptsch U. Leistungserbringerbezogene Merkmale. Routinedaten im Gesundheitswesen. In: Swart E, Ihle P, Gothe H, Matusiewicz D, editors. Handbuch Sekundärdatenanalyse Grundlagen, Methoden und Perspektiven. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber; 2014. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation (DSO) Annual Report 2011. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation; 2012. Organ Donation and Transplantation in Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 28.AQUA –. Qualitätsreport. Göttingen: AQUA-Institut GmbH; 2012. Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen GmbH 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed description of materials and methods

In this study, we analyzed the DRG statistics of the research data centers of the German federal and state offices of statistics using monitored remote data processing (17). The DRG statistics contain individual case data on all inpatient cases billed according to the DRG system. These data are reported by the hospitals once a year to the Institute for the Hospital Reimbursement System (Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus). A selected list of features is reported to the Federal Statistical Office. Data in this database from the year 2005 onward have been made available by the federal and state offices of statistics for scientific evaluation (17). Such evaluations are carried out by means of SAS programs created by the scientific users themselves that can access the data stored at the Federal Statistical Office.

Each of the approximately 17 million cases of treatments billed under the DRG system each year is accessible to evaluation via this database. The main types of cases not contained in the database are those of specialized psychiatric and psychosomatic units that do not bill under the DRG system. Such cases are irrelevant to the topic of the present study, as the existing minimum caseload requirements do not apply to them.

Further types of cases not included in the database are, for example, those of German military hospitals (insofar as they are not billed under the DRG system) and prison hospitals. These exceptions are likewise irrelevant to the topic of the present study, as the minimum caseload requirements to not apply to these cases either.

For all cases covered, the DRG statistics contain information on the main and additional diagnoses, the procedures performed (coded according to the German Operations and Procedures classification—Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel, OPS), the reason for discharge, and the billing institution, identified by its institutional identifying number (see Methods in the main text) (18– 21). This information suffices to enable the determination whether each billing institution met its minimum caseload requirements. Thus, the present study was performed by applying a uniform algorithm to a single database that covered all inpatient treatments in all German hospitals (i.e., the statistical parent population of inpatient cases). There was no need to amalgamate data from multiple databases, so issues of compatibility of different databases did not arise. All analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.3 statistics software.

Cases to which the minimum caseload requirements applied, according to the pertinent legal regulation (§ 137 SGB V), were identified by the OPS codes that the German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) determined to be applicable to the procedure in question for the year in question; these are published in Appendix 1 of the regulation. Because the OPS undergoes continuous revision, with frequent changes of content, there have been small changes over the period 2005–2011 in the OPS codes that needed to be considered for all types of procedure subject to minimum caseload requirements, with the sole exception of renal transplantation. The only change of this type that had a major quantitative effect was seen in the area of hepatic transplantation: the G-BA decided to exclude OPS code 5–502 (anatomical [typical] hepatic resection) from 2006 onward, with the result that, in 2006, 4779 fewer hepatic cases were subject to minimum caseload requirements than in the preceding year (an 82.4% drop from 2005 to 2006) (11).

Neonates weighing less than 1250 g at birth, whether born prematurely or at term, were identified in the database from their birth weight and from an age of 28 days or less, corresponding to the WHO definition of a “neonate” (22). Quantitative trends in the treatment of low-birth-weight neonates from the year 2005 onward were analyzed in relation to the minimum caseload requirement of 14 cases per year, even though this requirement did not go into effect until 2010. Similarly, quantitative trends in total knee replacement surgery were analyzed from 2005 onward, even though the corresponding minimum caseload requirement did not go into effect until 2006 (11).

The minimum caseload requirements for complex esophageal surgery and for stem cell transplantation do not apply to institutions that exclusively treat children (15). The G-BA does not state the precise age limit of “childhood” for the purpose of this regulation; in the present study, we excluded institutions from consideration if all the patients they treated with these two types of procedure were under 20 years old.

A treating institution, for the purpose of the present analysis, was held to be equivalent to a single institutional identifying number (IK number); in other words, all cases with the same IK number were considered to have been treated in the same institution. This method of data analysis may have caused bias of either of two different types, or both:

Hospitals that are geographically distributed over multiple sites, but have only a single IK number, were only counted once (as in the official DRG statistics). This would tend to cause an overestimation of the number of cases per institution, and therefore an underestimation of the number of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements.

On the other hand, single-site hospitals that bill via multiple IK numbers were counted as multiple institutions. This would tend to cause an underestimation of the number of cases per institution, and therefore an overestimation of the number of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirements (26).

Both of these constellations are rather rare, as shown by a comparison of a hospital count based on the IK numbers in the DRG statistics of the Federal Statistical Office with the the number of hospitals provided in the “basic hospital data” that are also maintained by this office (23, 24). The former of the two constellations is by far the more common in the real world. This implies that the present study probably overestimates the percentage of institutions that actually met the minimum caseload requirements—in other words, any bias, if present, is likely to be in the direction opposite to the central findings of the study. The validity of these findings is thus unaffected.

Table 1 contains a year-by-year listing of the percentages of institutions that met the minimum caseload requirements. The supplementary eTable shows how many institutions met the requirements only halfway and how many performed more than twice the required number of cases for each of the types of procedure specified.

Results: further details

The minimum caseload requirements set by the G-BA for hepatic transplantation and complex pancreatic surgery also included post-mortem organ removal in the tallies for each of these types of procedure. The number of institutions whose procedures in the category of hepatic transplantation were confined to post-mortem hepatectomy varied from 27 to 63, depending on the year; the comparable figure for post-mortem pancreatectomy was 2 to 3 institutions, depending on the year. The annual number of post-mortem organ removal procedures in each of these two categories was always either one or two per institution. The analysis in the present study took no account of institutions exclusively performing post-mortem organ removal, because minimum caseload requirements are clearly not intended to apply to “donor clinics” of this type. Moreover, post-mortem organ removal procedures are billed differently from other types of procedure and may not have been fully coded in the available DRG database.

In the institutions studied that performed both hepatic and pancreatic transplantation procedures on organ recipients and explantations on brain-dead organ donors, the post-mortem organ removals accounted for a mean of 2.11% of all hepatic transplant procedures and 0.17% of all complex pancreatic operations.

The minimum caseload requirement for hepatic transplantation includes living-donor partial hepatectomy for transplantation (OPS code 5–503.*) in the tally of procedures; thus, institutions performing procedures with this OPS code were included in the analysis of the present study. In 2011, 31 institutions performed hepatic transplantations and/or living-donor partial hepatectomy: 24 performed hepatic transplantation (OPS key 5–504.*), while the remaining 7 performed only living-donor partial hepatectomy for transplantation or liver-transplant resection as an independent procedure (OPS codes 5–503.1 through 5–503.y).

The 24 institutions performing hepatic transplantation that were identified from the DRG data correspond in number to the transplant centers listed in the 2011 annual report of the German Foundation for Organ Transplantation (Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation, DSO) (27) and to those listed in the quality report of the AQUA Institute for 2011 (28).

49 institutions billing for renal transplantation were identified from the DRG data; the AQUA institute reported 43 hospitals performing renal transplantation in 2011, the DSO 41. This discrepancy cannot be accounted for by hospitals that exclusively performed donor nephrectomies, because such procedures are not included in the tally of cases for the minimum caseload requirement (here the rule for renal transplantation differs from that for hepatic transplantation). The discrepancy cannot be definitively explained without de-anonymization of the IK numbers, which is not permissible. Conceivably, some cases of renal transplantation performed in the context of a close cooperation between different institutions may have been billed under multiple IK numbers.

For a deeper analysis of the caseload problem, we also determined the number of institutions meeting each caseload requirement not even halfway, or fulfilling it with more than twice the number of cases required. The percentage of institutions that failed to meet the minimum caseload requirement even halfway was lower in 2011 than in 2005 for every type of procedure studied, but the change was significant only for pancreatic surgery (p = 0.012) and low-birth-weight neonatal care (p = 0.0057). On the other hand, the number of institutions meeting their requirements with more than twice the required number of cases rose significantly for hepatic transplantation (p = 0.011), esophageal surgery (p = 0.015), pancreatic surgery (p = 0.0072), and low-birth-weight neonatal care (p = 0.021). The highest percentages of institutions of this type in the year 2011 were found for total knee replacement (50.8%) and renal transplantation (49.0%) (eTable).