Abstract

Introduction

The British Orthopaedic Association/British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons guidelines for the management of open tibial fractures recommend early senior combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical input with appropriate facilities to manage a high caseload. The aim of this study was to assess whether becoming a major trauma centre has affected the management of patients with open tibial fractures.

Methods

Data were obtained prospectively on consecutive open tibial fractures during two eight-month periods: before and after becoming a trauma centre.

Results

Overall, 29 open tibial fractures were admitted after designation as a major trauma centre compared with 15 previously. Of the 29 patients, 21 came directly or as transfers from another accident and emergency deparment (previously 8 of 15). The time to transfer patients admitted initially to local orthopaedic departments has fallen from 205.7 hours to 37.4 hours (p=0.084). Tertiary transferred patients had a longer hospital stay (16.3 vs 14.9 days) and had more operations (3.7 vs 2.6, p=0.08) than direct admissions. As a trauma centre, there were improvements in time to definitive skeletal stabilisation (4.7 vs 2.2 days, p=0.06), skin coverage (8.3 vs 3.7 days, p=0.06), average number of operations (4.2 vs 2.3, p=0.002) and average length of hospital admission (26.6 vs 15.3 days, p=0.05).

Conclusions

The volume and management of open tibial fractures, independent of fracture grade, has been directly affected by the introduction of a trauma centre enabling early combined senior orthopaedic and plastic surgical input. Our data strongly support the benefits of trauma centres and the continuing development of trauma networks in the management of open tibial fractures.

Keywords: Open fracture, Trauma network, Major trauma centre, Gustilo, Tibial fracture

Open lower limb fractures are frequently complex high energy injuries that are often associated with soft tissue loss, contamination and periosteal stripping. The 2009 British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) and British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) guidelines recommend that these injuries should be managed in units that have a high caseload and a service led by consultant orthopaedic and plastic surgeons with a sub-specialty interest in treating these difficult problems. 1 Using the guidelines for optimal care, namely senior combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical first debridement within 24 hours, definitive soft tissue cover within 7 days can be achieved. Outcome data have shown that open tibial fractures are generally managed suboptimally, with significant delays in transferring patients to specialist units and inappropriate early treatment. 2–4

In 2007 the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death found that over half of trauma patients receive substandard care. 5 London, specifically, was highlighted as lagging behind other major UK cities owing to a lack of centralisation and organisation of trauma in its hospital network. 6 Outcomes should be measured by time from injury to definitive surgery and not time to arrival in the nearest hospital. 7

The fundamental principles of the trauma centre model relevant to patients with open lower limb fractures are enhancing prehospital care, rapid transfer to the best local facility, and integrating trauma services with and between hospitals. Improving rehabilitation, audit and research in a trauma network has been highlighted to improve postoperative outcomes and future systems of care. 8

Prior to the trauma network, patients were admitted routinely to the hospital geographically closer to where the injury was sustained. There were variable and sometimes informal arrangements in ambulance networks for bypassing local hospitals and heading to specialist units. Implementation of the trauma network has not only resulted in major trauma centres but also clear protocols for paramedics and ambulance teams on assessing injury characteristics warranting specialist trauma centre care. If patients with severe open limb injuries were admitted to non-specialist units, the decision to transfer patients was equally variable and was often only made once the patient had been admitted, when skin coverage was required or when complications arose. 5

The London trauma network was introduced in April 2010 and St George’s Hospital became one of four London trauma centres. The aims of this study were to assess whether becoming a trauma centre and applying the BOA/BAPRAS guidelines 1 has affected referral patterns of patients with open tibial fractures and, compared with delayed ‘tertiary referrals’, whether it has affected the number of operations and length of stay, and, ultimately, led to better care.

Methods

Data were collated prospectively on consecutive open tibial fractures treated at St George’s Hospital during two eight-month periods: 1 May – 31 December 2009 and 1 April – 31 November 2010. Our institution became a designated trauma centre in April 2010 and these cohorts were therefore before and after the implementation of the London trauma network. Data were collected on admission pathway, mechanism of injury, fracture classification and grade, timing of first debridement, skeletal stabilisation and definitive skin coverage.

Patients were included if they were admitted directly to St George’s Hospital, transferred as ‘hot’ transfers or transferred for specialist input from other hospitals (tertiary referrals). We have defined a hot transfer as a referral directly from another accident and emergency (A&E) department without admission to the primary hospital. The decision to transfer can be made by the local A&E department independent of orthopaedic input or formal specialty referral. The hot transfer is an improved system of transferring patients integral to the trauma network. This did occur occasionally prior to the trauma centre being established but it was usually in extreme cases such as vascular compromise or for paediatric cases in units lacking paediatric anaesthetists.

All tibial plateau, diaphyseal, ankle and pilon fractures were included. No patients were excluded based on mechanism of injury, age, co-morbidities or associated injuries.

In terms of referral pattern, the number of hot transfers is relevant to how the trauma network is working. However, in terms of orthoplastic management, the hot transfers and direct admissions were analysed as one group. They were both admitted straight from the A&E department at which they presented originally to the trauma centre and then the team approach was the same regardless of which A&E department they presented to initially. The time from injury to first debridement was not significantly greater for hot transfers than for direct admissions (p=0.36). It was therefore felt reasonable to analyse time to senior joint debridement, length of stay, time to skeletal fixation and skin coverage together for these groups. Data were analysed using Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test.

Results

There were 15 open tibial fracture patients (12 male, 3 female) between May and December 2009 compared with 29 (16 male, 13 female) in the 8 months following establishment of the trauma centre (April – November 2010). The average age was not significantly different between the groups, being 37 years (range: 12–73 years) in the first cohort and 44 years (range: 8–93 years) in the second cohort (p=0.38).

The fracture classification is summarised in Table 1. Severity of injury was not significantly different before and after estalishment of the trauma centre (p=0.75).

Table 1.

Number of patients treated in the two cohorts according to the gustilo fracture classification

| Fracture type | Before establishment of trauma centre | After establishment of trauma centre |

|---|---|---|

| I | 0 | 0 |

| II | 3 | 4 |

| IIIA | 3 | 10 |

| IIIB | 9 | 13 |

| IIIC | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 15 | 29 |

Source of referral

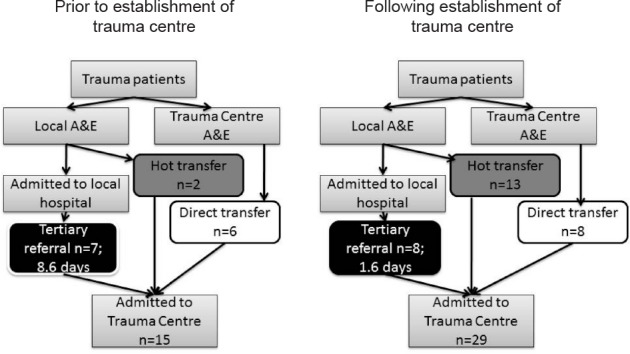

Figure 1 illustrates the differences in patient flow before and after estalishment of the trauma centre. The time taken to transfer the tertiary referred patients to the specialist centre fell in the second cohort. The average time from injury to arrival in the specialist centre was 205.7 hours (8.6 days) in the first cohort and 37.4 hours (1.6 days) in the second cohort (p=0.084). Of all those referred from other centres, there was a trend towards more hot referrals rather than tertiary referrals (p=0.1).

Figure 1.

Admission pathway of patients admitted to our institution in the two cohorts

The tertiary referrals had variable management at their local hospital before transfer. Of the seven tertiary referrals in the first cohort, five were referred having had debridement and a spanning external fixator locally but still requiring definitive skeletal stabilisation and soft tissue cover. The remaining two were referred for soft tissue coverage of an intramedullary nail in one (against ‘fix and flap’ principles) and an Ilizarov frame in the other.

Similarly, of the eight tertiary referrals from the second cohort, one had definitive fixation but needed soft tissue coverage. The remaining seven had local wound debridement but required both definitive stabilisation and soft tissue coverage.

Joint orthopaedics and plastics

The time to first debridement in all cases for both groups and regardless of referral pathway was less than 24 hours and therefore complied with BOA/BAPRAS guidelines. 1 The mean time to theatre in the forst cohort was 9.2 hours (range: 1.5–17 hours) and not significantly different to the 10.5 hours (range: 2–22 hours) for the second cohort (p=0.6). Hot and direct transfers were not taken to theatre significantly more quickly for their first debridement compared with tertiary referrals (p=0.16).

Before the establishment of the trauma centre, only 1 of the 15 patients had combined first debridement whereas 21 of 29 were managed jointly from first debridement in the second cohort (p<0.0001). The eight patients in the second cohort who were managed only by orthopaedics had small, uncomplicated wounds that were all closed primarily.

The time to definitive skeletal stabilisation improved, almost reaching significance (p=0.06), from 4.7 days (range: 0.5–19 days) to 2.2 days (range: 0.5–9 days). The time to definitive soft tissue cover also improved, from 8.3 days (range: 3–34 days) to 3.7 days (range: 0.5–28 days) (p=0.06). Four patients in the first cohort were not covered within one week while only one patient was not covered in the second cohort (p=0.02). This patient was a delayed tertiary referral who had been temporised with a vacuum-assisted closure dressing at another hospital.

Time to soft tissue cover was also determined by the means of referral, with hot and direct referrals achieving the one week target in all cases but one, compared with tertiary referrals (already a smaller group) not reaching this target in nearly half the cases (p=0.03). Significantly more patients were closed directly in the second cohort than in the first cohort (p=0.007) and the proportion requiring free flaps fell, although this was not significant (p=0.32).

Number of operations

The average number of operations per patient prior to the trauma network was significantly higher at 4.2 (range: 2–11) compared with 2.3 (range: 1–6) afterwards (p=0.002). Patients admitted initially to a regional hospital had an average of 3.7 operations (range: 2–6) compared with 2.6 (range: 1–11) in those admitted directly to our institution or as hot transfers (p=0.08).

Length of stay

The overall length of hospital stay was reduced for all patients following the establishment of the trauma centre (p=0.05). Overall, those admitted to a regional hospital first had an average stay of 21.1 days (range: 5–45 days) compared with 16.4 days (range: 4–63 days) (p=0.26). Patients in the first cohort admitted via a regional hospital were in hospital for 26.6 days (range: 14–45 days) and those in the second cohort for 16.3 days (range: 5–43 days) (p=0.11). In the first group, those patients admitted directly or via a hot transfer were in hospital for an average of 22.1 days (range: 6–63 days), while in the second group the average length of stay was 14.9 days (range: 4–43 days) (p=0.34).

Classification by Gustilo fracture

When data were broken down by Gustilo classification, trends to significance in improvements for the second cohort included length of stay for type IIIB fractures and time to skeletal stabilisation, especially for type II fractures. Significant improvements included fewer operations for types II and IIIB fractures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes by gustilo fracture classification before and after establishment of the trauma centre

| Fracture type | Length of stay (days) | Number of operations | Skin coverage (hours) | Skeletal stabilisation (hours) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | p-value | Before | After | p-value | Before | After | p-value | Before | After | p-value | |

| II | 10.7 | 8.8 | >0.1 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 0.005 | 121 | 31 | >0.1 | 114 | 13 | 0.09 |

| IIIA | 17.0 | 12.7 | >0.1 | 2.3 | 1.7 | >0.1 | 63 | 46 | >0.1 | 15 | 36 | >0.1 |

| IIIB | 29.4 | 18.2 | 0.08 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 0.02 | 253 | 141 | >0.1 | 128 | 72 | >0.1 |

| IIIC | 0** | 22.5 | – | 0** | 4.0 | – | 0** | 168 | – | 0** | 144 | – |

There were no Gustilo type IIIC patients in the first cohort.

Discussion

There are about 1,200 trauma cases with an injury severity score of >15 each year in London, which has a population of 7.7 million. 6 London has been highlighted as performing poorly and behind other major UK cities. 5 Specifically, the timely and effective management of open lower limb fractures has been problematic. Allison et al have highlighted that despite the distribution of previous guidelines and the availability of combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical teams, outcomes were limited by poor communication and delay in transfer. 2

Outcome studies from the Victorian State Trauma System have emphasised the importance of ‘delivering the right patient to the right hospital in the shortest time’. 9 As a consequence, the London trauma network was introduced in April 2010 and St George’s Hospital became one of four London trauma centres. This paper is the first to analyse the impact of the South West London trauma network on the management of these complex injuries.

The volume of open tibial fractures managed at our institution almost doubled between the two time periods (factor of 1.93). The guidelines recommend that units should have a throughput of at least 30 cases per year to maintain appropriate skill and experience levels. 1 The restructuring of the London trauma network has resulted in our institution achieving this target.

The trauma network has had a positive effect on the way trauma patients are referred and transferred. In the first cohort, 7 of the 15 patients (47%) were admitted initially under local orthopaedic departments and transferred subsequently as a tertiary referral whereas in the second cohort, 8 of the 29 referrals (28%) were tertiary. Only two of these eight tertiary referrals were from the South West London trauma network. Importantly, the prioritisation of trauma cases has reduced the time to transfer tertiary patients to our institution (p=0.086). There has also been a trend towards more hot transfers, from 2 to 13 (p=0.06).

In addition to the trauma network, at the time of becoming a trauma centre, South West London Deanery orthopaedic specialist registrar teaching and regional trauma audits increased the awareness of the BOA/BAPRAS guidelines. 1 This highlighted that all open tibial fractures should be transferred and not initially managed locally by orthopaedics, as had occurred historically. It is not obvious why the six referred from outside the South West London trauma network were not managed in their own network.

Currently, the London ambulance service (LAS) is fully integrated in the London trauma network. However, many of the satellite hospitals for which our institution is the tertiary orthopaedics and plastics unit are not covered by the LAS but by other ambulance networks. The ambulance transfer protocols also relate to major trauma and not to open fractures. We are working on getting this changed. At the moment, some do and some do not adopt this policy of direct transfer of open fractures to a trauma centre. This trend in increased hot transfers resulted from education and feedback to satellite regional hospitals in line with the guidelines. 1 The gold standard is for direct admission to a trauma centre irrespective of ambulance network.

Following audit of the data from prior to establishment of the trauma centre, both plastic and orthopaedic departments made internal improvements to increase compliance with the BOA/BAPRAS guidelines. 1 This involved hospital management increasing theatre capacity, including a dedicated major trauma theatre, prioritisation for joint cases and provision for consultant led care. Multidisciplinary outpatient clinics have also been set up to follow up these challenging patients jointly to improve communication and integration between the specialties. A weekly multidisciplinary orthopaedic and plastic surgical meeting discusses cases and feedback is provided to hospitals in the network where patients were not managed optimally.

The Trauma Audit and Research Network quality indicators use elements of BOA and BAPRAS guidelines to bench-mark and remunerate hospitals on how they manage open limb injuries. Debridement should be performed by senior surgeons within 24 hours of injury. 10

Since the introduction of the trauma centre, there has been a highly significant increase in joint senior orthopaedic and plastic surgical care (p<0.0001). This is perhaps reflected in the decreased lengths of stay (p=0.05) and trends to decreased time to definitive skeletal stabilisation and soft tissue cover (p=0.06). The decreased number of operations per patient (p=0.002) has been shown to significantly alter outcome in other published series. 11,12 There was a trend highlighting that those treated in regional centres initially underwent more operations in total (p=0.08). Interestingly, although there was no significant difference in severity of injury between groups, a significant proportion underwent primary closure in the trauma centre (p=0.0071). The proportion requiring free flaps decreased although this did not reach significance (p=0.32).

The subgroup analysis by fracture type demonstrates trends towards improved outcomes following the estanlishment of the trauma centre across all fracture severities. Although not all of these reached significance, this could perhaps be explained by the small numbers in these groups. Those reaching significance included fewer operations for Gustilo type II and IIIB fractures. This suggests that even the low grade open fractures benefit from transfer to a specialist unit where there is a high volume workload and appropriate experience.

Conclusions

The volume and management of open tibial fractures has been directly affected by the introduction of a trauma centre in the London trauma network. Implementation of BOA and BAPRAS guidelines 1 has resulted in improved management of open lower limb fractures independent of fracture grade compared with delayed referrals and our pre-trauma centre outcomes. Our data strongly support the benefits of trauma centres and the continuing development of trauma networks in the management of open tibial fractures. Continued prospective audit is encouraged to allow robust data analysis.

References

- 1.Nanchahal J, Nayagam S, Khan Uet al Standards for the Management of Open Fractures of the Lower Limb. London: BAPRAS; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison K, Wong M, Bolland Bet al The management of compound leg injuries in the West Midlands (UK): are we meeting current guidelines? Br J Plast Surg 2005; 58: 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naique SB, Pearse M, Nanchahal J. Management of severe open tibial fractures: the need for combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical treatment in specialist centres. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006; 88: 351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townley WA, Nguyen DQ, Rooker JCet al Management of open tibial fractures – a regional experience. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010; 92: 693–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Trauma: Who Cares? London: NCEPOD; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.London Trauma Office. Mid-year Report for the Period April – September 2010. London: London Trauma Office; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago: ACS; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Report of the Working Party on the Management of Patients with Major Injuries. London: RCS; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron PA, Gabbe BJ, Cooper DJet al A statewide system of trauma care in Victoria: effect on patient survival. Med J Aust 2008; 189: 546–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trauma Audit and Research Network. Quality Indicators for Trauma Outcome and Performance. Manchester: TARN; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollak AN, Jones AL, Castillo RCet al The relationship between time to surgical debridement and incidence of infection after open high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 7–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JFet al An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1,924–1,931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]